ABSTRACT

This paper is a quantitative synthesis of research on home literacy environment (HLE) and children’s English as a second language (ESL) learning outcomes through a meta-analysis of 18 articles in kindergarten, primary, and secondary school students (N = 4401) carried out between 2000 and 2018. It examines the associations between HLE factors and children’s ESL performance. Results showed the effect sizes between HLE factors and children’s ESL performance was small to moderate. Family members shared a similar effect size on children’s ESL performance. Parental literacy teaching behaviors have stronger effects on children’s ESL ability than parental beliefs on their children’s English learning and the availability of learning resources at home. These results highlight the importance of HLE and indicate the relative contributions of specific HLE factors on children’s ESL acquisition.

Home literacy environment (HLE) plays an important role in children’s language development. While more is known about the contribution of HLE to children’s first language development, relatively little is understood about its contribution to children’s second language acquisition. To the best of our knowledge, no previous attempts have examined how different HLE factors influence ESL (English as second language) learning by synthesizing the research evidence from past studies. Children acquire ESL knowledge through interacting with their family members, engaging in literacy activities (e.g., parental teaching), and utilizing literacy learning resources (e.g., books) at home. However, the relative contributions of the different home literacy environment factors on children’s ESL performance remain unclear. Therefore, the current study aims to provide a quantitative synthesis of current research on HLE and learning outcomes of children’s ESL performance using a meta-analytic approach. This study focused on English receptive vocabulary, as it is the foundation for reading and linguistic comprehension, and is an important ESL language outcome, particularly in beginning learners (Author, Citation2020a; Kim, Citation2020; Tunmer & Chapman, Citation2012).

HLE

HLE refers to a multifaceted construct that includes language- or literacy-related activities between parents and children, using resources at home (Niklas et al., Citation2016; Sénéchal & LeFevre, Citation2002). It includes different aspects, such as the environment (literacy-related opportunities provided by parents); literacy interface (parents’ participation and approaches to literacy activities); passive HLE (parents’ literacy modeling in leisure activities); active HLE (parents’ engagement in language learning activities); and shared reading (Burgess et al., Citation2002). Studies have found that HLE factors such as library visits, functional uses of and verbal reference to literacy, parental encouragement and attitudes toward reading, parental teaching of literacy skills, parental modeling of literacy behaviors, parent–child shared reading, and number of books at home are positively linked to children’s language ability (e.g., Yeung & King, Citation2016). In early childhood language learning, children acquire alphabetical knowledge, phonological and orthographic processing skills, as well as other relevant language elements (e.g., vocabulary), from home literacy activities (Author, Citation2017). A rich HLE includes having access to visiting libraries, engaging with literature activities (e.g., conversation with family member) and experiencing literacy developmental success (Weigel et al., Citation2010). Different home literacy activities can be categorized into direct (e.g., parental shared book reading) or indirect (e.g., literacy video tape watching) activities (Sénéchal et al., Citation1998). A widely held assumption (e.g., Social-ecological framework: Davidson et al., Citation2018) states that the literacy environment at home plays a key role in second language (L2) acquisition and helps promote success in life.

Today, an adequate English competency and proficiency is considered an important component of successful academic and career development (Meng, Citation2015; Snow, Citation2006). Therefore, factors that boost ESL ability have drawn great attention from researchers. HLE has a significant role in ESL learning, yet no meta-analysis provides scientific evidence on the extent to which HLE contributes to ESL acquisition. Therefore, this study extends past research by conducting a meta-analysis examining the contribution of HLE and its aspects (e.g., parental involvement) on the acquisition of ESL. This study focused on HLE factors which were proximal to and closely associated with children’s ESL ability, including HLE resources, parental involvement, shared reading, parental beliefs, maternal effect, paternal effect, and siblings effect (Author, Citation2020b; Niklas et al., Citation2020).

HLE and children’s ESL acquisition

Sénéchal and LeFevre (Citation2002) reported a complex relationship between children’s home literacy activities and language acquisition through a longitudinal study design. Specifically, they found that children’s ESL book reading ability was related to parental vocabulary teaching and children’s listening comprehension skills. Literacy activities foster the interaction between family members and children, which enhances children’s development of ESL acquisition (Bracken & Fischel, Citation2008; Frijters et al., Citation2000; Sénéchal & LeFevre, Citation2014). There are two potential pathways in which HLE may impact children’s language learning. First, family members can support children’s language development through language interaction and literacy activities. Second, family members can foster a rich literacy environment, such as providing ESL learning materials to children (Burgess et al., Citation2002).

Parental literacy teaching behaviors

Parental literacy teaching behaviors include parent-child shared reading and parental involvement in literacy activities with their children (Sénéchal et al., Citation1998; Weigel et al., Citation2006). In early childhood, shared book reading is an important component of parent–child interaction. Book reading is regarded as the most important activity for developing the knowledge required for eventual success in basic language and metaphor acquisition (Caesar & Nelson, Citation2014; Debaryshe, Citation1993; Weigel et al., Citation2006). It allows children to be immersed in another language environment, stimulating children’s learning interest and intrinsic learning motivation (DesJardin et al., Citation2017; Elley & Mangubhai, Citation1983). Parental involvement in children’s language learning activities is important to children’s language development (Caesar & Nelson, Citation2014; Niehaus & Adelson, Citation2014). Parental involvement contributes to children’s second language development in different ways, including literacy environment construction (He et al., Citation2015; Hosseinpour et al., Citation2015), language exchange and communication (Varghese & Wachen, Citation2016; Wang, Citation2015), and grammatical knowledge instruction (Bruin, Citation2018; Forey et al., Citation2016).

Learning resources and parental beliefs

Parental beliefs on their children’s English learning and the availability of learning resources at home, such as books and electronic learning materials, have been found to be linked to children’s language development (Wang, Citation2015). The number of books at home is strongly correlated to children’s literacy knowledge base (Dixon & Wu, Citation2014). For example, the availability of foreign language books is positively linked to children’s phonological processing (Trainin et al., Citation2017). Oller (Citation2014) showed that book storage at home enhances literacy knowledge in African-American immigrant children and their mothers. It is also linked to an increased engagement of literacy activities at home.

Parental perceptions on children’s ESL learning play a key role in supporting children’s ESL development. Parents with positive beliefs on ESL teaching are likely to foster a rich HLE and actively engage children in ESL-related literacy activities. Positive parental beliefs help create more literacy experiences in which children and parents work together (Sigel et al., Citation2002). Parental beliefs influence parents’ literacy behaviors and interaction with children’s learning motivation and learning habit development (Harkness & Super, Citation1992). Evans et al. (Citation2004) reported that parental beliefs enhanced children’s ESL phonics, sounding out words, and word spelling patterns. Sonnenschein’s team (Sonnenschein et al., Citation1997) reported that parental beliefs enhanced the cultivation of children’s ESL storybook reading interest. Baker and Scher (Citation2002) revealed that parents who viewed reading as a source of entertainment were likely to have children who enjoyed reading. In addition, Burgess et al. (Citation2002) pointed out that parents’ beliefs determined the quality of literacy activities. The current study aims to compare the effects of different HLE factors on children’s ESL performance through the meta-analytic approach.

Language impact of family members

Past studies have shown evidence of a strong maternal effect on children’s language acquisition. For example, Deckner et al. (Citation2006) reported that the frequency of mother–child interaction activities enhances children’s language performance. Additionally, research has also demonstrated the unique impact of fathers on children’s language acquisition (Flouri & Buchanan, Citation2004; Pungello et al., Citation2009). For instance, Burgess (Citation1998) and Farver et al. (Citation2013) showed that fathers have an important impact on children’s mind set on language learning. Tamis-LeMonda et al. (Citation2004) have also reported that father’s language proficiency contributes to children’s learning. Moreover, siblings’ effect has also drawn attention from researchers due to the high interaction frequency between children and their sibling(s). Studies have shown that sibling’s language proficiency affects children’s language performance in receptive vocabulary acquisition (Grépin & Bharadwaj, Citation2015; Qureshi, Citation2018). However, the relative importance and differential effects of family members on children’s ESL learning remains unclear. This study aims to fill in this research gap through a meta-analysis.

The present study

The current study is the first review to use a meta-analytic approach analyzing the effects of HLE on ESL performance in school-age children. Three research questions are investigated in this study. First, to what extent is HLE linked to ESL performance? It is hypothesized that the correlation effect size between HLE factors and ESL will be large. Second, what is the relative importance of various aspects of HLE on children’s ESL performance? It is expected that parental direct involvement in activities will have a larger effect size than indirect parental beliefs on children’s ESL ability. Lastly, do immediate family members have differential influence on children’s ESL ability? It is expected that immediate family members have similar correlation effect size on children’s ESL ability.

Method

Literature base and inclusion criteria

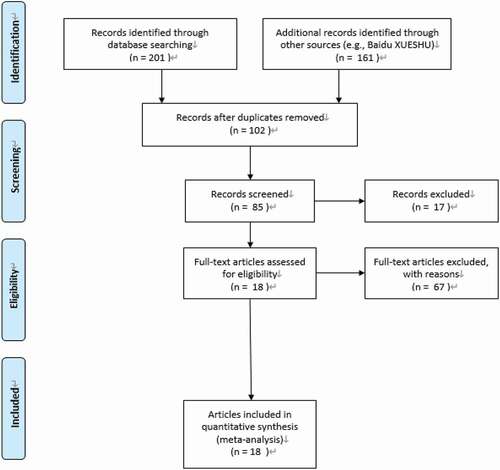

This study searched potential journal articles, book chapters, and dissertations from popular databases including PsycINFO, LLBA, EBSCO, Pro-Quest, China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), and Education Resources Information Center (ERIC). To investigate the correlation between each category of HLE factors and ESL performance, this study set up two groups of key terms for the search of potential materials. The first group of terms was associated with HLE, which includes home literacy environment*, home literacy*, family literacy*, home language*, family language*, HLE*, home literacy resources*, parental language*, parental activity*, parental involvement*, parental participation*, shared reading experiences*, maternal activities*, and paternal activities*. The second group of terms focused on second language status: L2*, ESL*, English learning*, English development*, language development*, language performance*, word*, word reading*, word cognition*, word identification*, word semantic*, inference*, semantic inference*, vocabulary*, receptive vocabulary*, and immigrant*. For the same articles identified across databases, the duplicated ones were removed. After the removal of these duplicated articles, a total of 102 articles were identified. This study set up the following criteria for the selection of empirical studies (See ): (1) the studies were published in year from 2000 to 2018; (2) the studies were peer-reviewed; (3) the journal articles were written in English; (4) the studies provided the correlation indices between HLE and ESL performance; (5) participants were between the ages of 6 to 16; (6) the independent variables included language or literacy practices in English; (7) participants’ second language was English and their English performance was measured by receptive vocabulary; and (8) HLE measures included receptive vocabulary measures (e.g., Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test [PPVT], Woodcock Language Proficiency Battery [WLPB]). To further ensure the quality of the selected empirical studies, there were inclusion criteria on measurement reliabilities and sample size. The reliabilities of measurements for both English performance and English HLE practice or activities were over .70, and the minimum sample of participants was 30 to minimize random error (García & Cain, Citation2014; Mol & Bus, Citation2011). After applying these criteria, 85 articles remained.

It should be noted that this study investigated the effects of HLE on those aged under 16 years old because previous studies demonstrated rapid growth in linguistic abilities in this period (Author, Citation2020c; García & Cain, Citation2014). This study also included ESL learners who are immigrants, or children of immigrant parents. Further, we also included studies with oral and written language as the outcome variable (Dickinson & Tabors, Citation2001).

The following studies were excluded: single case studies, opinion or non-empirical articles, and variables did not include HLE or HLE relevant factors. If the abstract did not provide the required information, the major body of the paper was reviewed. The selected papers were required to report correlation (r) or percentage of variance R2, which can be transformed to the corresponding correlation effect size (Fishers’ z) between any measurements of HLE and children’s ESL performance. If the same sample data were collected from different articles, the data were only coded once. Hence, Butler (Citation2014), Sénéchal et al. (Citation2013), and Howard et al. (Citation2014) were excluded. In total, 18 articles met all the inclusion criteria and were thus included in this study.

Coding process

Participants’ demographic information was coded: sample size (N), first language (L1) – non-alphabetical or alphabetical, first author, publication year, country/region, and children’s grade level. We then coded HLE variables and children’s ESL performance. Almost no study could provide all the required information with all target HLE variables and relevant factors. The articles’ correspondence authors were contacted to provide the missing information.

To investigate HLE and HLE factors’ effects on children’s ESL performance, the current study coded the correlation between children’s ESL performance and HLE and HLE factors independently. Family members’ effect was divided into paternal effect, maternal effect, and siblings’ effect. If the correlation category was unclear, for example, if a study provided only a composite score of shared reading and parents’ beliefs but not separate scores for each variable, it was not included in the present study because the present study investigated the correlation between each HLE category factor and children’s ESL performance. In each category correlation, if the study provided more than one available correlation score, the Robust Variance Estimates (Tanner-Smith et al., Citation2016) was applied, ensuring each study only provided one effect size for meta-analysis at each category correlation. All detailed information was provided in .

Table 1. Demographical information and effect sizes of HLE factors on children’s ESL performance.

Meta-analytic procedures

This study used Mol and Bus (Citation2011) analytical procedures. Firstly, all correlation indicators between HLE and any ESL outcome variables were transformed into Fisher’ z effect size, which followed an asymmetrical distribution (Borenstein et al., Citation2009), through the comprehensive Meta-analysis (CMA) 3.0 program (Fisher, Citation2019). Based on Cohen’s (Citation1988) and other scholars’ views (e.g., Lipsey & Wilson, Citation2001), a correlation of r < .10 is considered a small effect size (Fisher’s z), a correlation of r = .30 is considered a moderate effect size (Fisher’s z), and a correlation of r > .50 is considered a large effect size (Fisher’s z). If the study did not provide the bivariate correlation indicator, this study calculated the Fisher’s z through CMA.

This study adopted the random-effects model perspective from a conservative view which followed Borenstein et al.’s (Citation2009). The random-effects model provides a larger range of correlation estimations than the fixed-effects model. The correlation estimation was regarded as significant if the 95% confidence interval did not include zero. Moderator analysis was applied if the Q value reached significance or the I2 reached higher than 25 (Hedges & Olkin, Citation1985; Tanner-Smith & Tipton, Citation2014), which showed the heterogeneity level of selected studies. If the minimum number of the selected study was over four, moderator analysis was conducted by moderator regression. For each correlation category effect size comparison, this study followed the following steps between each two correlations category: Teta = Fisher’s z1- Fisher’s z2, Beta = sqrt (Variance z1+ Variance z2), Diff = Teta/Beta, if |Diff|≥1.96, we can interpret the difference between two effect sizes as significant (Borenstein et al., Citation2009). Regarding publication bias examination, the current study examines the Rosenthal’s fail-safe-number, funnel plots through the trim-and-fill method, and Egger’s regression test (Hemilä, Citation2017; McShane et al., Citation2016).

Results

Descriptive statistics

A total of 18 articles (22 studies as 2 articles had more than one target correlations provided) met this study’s inclusion criteria (N = 4401). Specifically, 11 (n = 2250), 8 (n = 1848), and 3 studies (n = 303) reported correlations between HLE and ESL performance in kindergartners, primary school children, and secondary school children, respectively. The effect size index used for all outcome measures was Fisher’s z. This study transformed correlation r to Fishers’ z. After the meta-analysis was conducted, Fishers’ z was transformed back to the correlation r for an easy interpretation. The number of synthesized studies on the correlations between children’s ESL ability with parental involvement, shared reading, parental beliefs, HLE resources were 10, 6, 4, 15 respectively, and those with maternal, paternal and sibling’s effects were 7, 4, and 5 respectively.

Correlations between home literacy variables and children’s ESL performance

shows all correlation effect sizes between HLE factors and children’s ESL performance.

Table 2. Correlations of HLE factors and children’s ESL performance.

Effects of parental literacy teaching behaviors

The effect size of parental involvement- children’s ESL performance was moderate (z parental involvement = .32, p parental involvement <.001, Q = 2.10, p > .10, I2 < .001). The heterogeneity was not statistically significant (p > .10), indicating that further moderator analysis is not required. The Rosenthal’s fail-safe-number was 432, funnel plot showed the correlation effect size distributed symmetry, and the Egger’s regression showed the intercept was .56 (p > .10), suggesting the selected studies for the correlation between parental involvement and children’s ESL performance did not have significant publication bias.

The effect size of shared reading – children’s ESL performance was moderate (z shared reading = .31, p shared reading<.001, Q = 1.93, p > .10, I2 < .001). The heterogeneity was not statistically significant (p > .10), indicating that further moderator analysis is not required. The Rosenthal’s fail-safe-number was 88, funnel plot showed the correlation effect size distributed symmetry, and the Egger’s regression showed the intercept was 1.54 (p > .10), suggesting the selected studies for the correlation between shared reading and children’s ESL performance did not have significant publication bias.

Effects of parental beliefs and learning resources

The effect size of parental beliefs – children’s ESL performance was small (z parental beliefs =.17, p paternal effect<.001, Q = .76, p > .10, I2 < .001). The heterogeneity was not statistically significant (p > .10), indicating that further moderator analysis is not required. The Rosenthal’s fail-safe-number was 5, funnel plot showed the correlation effect size distributed symmetry, and the Egger’s regression showed the intercept was .87 (> .10), suggesting the selected studies for the correlation between parental beliefs and children’s ESL performance did not have significant publication bias.

The effect size of HLE resources – children’s ESL performance was moderate (z HLE resources = .20, p HLE resources<.001, Q = 12.37, p > .10, I2 < .001). The heterogeneity was not statistically significant (p > .10), indicating that further moderator analysis is not required. The Rosenthal’s fail-safe-number was 456, funnel plot showed the correlation effect size distributed symmetry, and the Egger’s regression showed the intercept was .72 (p > .10), suggesting the selected studies for the correlation between HLE resources and children’s ESL performance did not have significant publication bias.

Effects of family members

The effect size of maternal effect – children’s ESL performance was moderate (z maternal effect = .27, p maternal effect<.001, Q = 8.91, p > .10, I2 = 32.64). Because I2 was over 25, further moderator analysis was conducted. The moderator analysis showed that the L1 was a significant moderator to the correlation of maternal effect-ESL performance. The Rosenthal’s fail-safe-number was 197, funnel plot showed the correlation effect size distributed symmetry, and the Egger’s regression showed the intercept was 1.45 (p > .10), suggesting the selected studies for the correlation between maternal effect and children’s ESL performance did not have significant publication bias. A moderator analysis with L1 (alphabetic and non-alphabetic) as a moderator in the correlation between maternal effect and children’s ESL performance was conducted. The results of the effect of alphabetic scripts showed that the effect size was moderate (z maternal effect = .25, p maternal effect<.001, Q = 1.24, p > .10, I2 < .001). The heterogeneity was not statistically significant (p > .10), indicating that further moderator analysis is not required. The results of the effect of non-alphabetical scripts showed that the effect size was moderate (z maternal effect = .20, p maternal effect<.001, Q = .06, p > .10, I2 < .001). The heterogeneity was not statistically significant (p > .10), indicating further moderator analysis is not required.

The effect size of paternal effect – children’s ESL performance was moderate (z paternal effect = .36, p paternal effect<.001, Q = 3.95, p > .10, I2 = .10.86). The heterogeneity was not statistically significant (p > .10), indicating that further moderator analysis is not required. The Rosenthal’s fail-safe-number was 53, funnel plot showed the correlation effect size distributed symmetry, and the Egger’s regression showed the intercept was 3.55 (p > .10), suggesting the selected studies for the correlation between paternal effect and children’s ESL performance did not have significant publication bias.

The effect size of siblings’ effect – children’s ESL performance was moderate (z siblings = .24, p siblings <.001, Q = 1.10, p > .10, I2 < .001). The heterogeneity was not statistically significant (p > .10), indicating that further moderator analysis is not required. The Rosenthal’s fail-safe-number was 64, funnel plot showed the correlation effect size distributed symmetry, and the Egger’s regression showed the intercept was .70 (p > .10), suggesting the selected study for the correlation between siblings’ effect and children’s ESL performance did not have significant publication bias.

Effect size comparisons

Borenstein et al.’s (Citation2009) analysis was conducted to compare the effect sizes across HLE-ESL performance pairs (e.g., parental involvement – children’s ESL performance vs parental beliefs – children’s ESL performance). The differences of effect sizes between parental involvement – children’s ESL performance and parental beliefs – children’s ESL performance (Diff = 2.12, p < .05), parental involvement – children’s ESL performance and HLE resources – children’s ESL performance (Diff = 3.46, p < .001), shared reading – children’s ESL performance and parental beliefs – children’s ESL performance (Diff = 2.12, p < .05), and shared reading – children’s ESL performance and HLE resources – children’s ESL performance (Diff = 3.46, p < .001) were significant. However, the differences of effect sizes between maternal effect – children’s ESL performance and paternal effect – children’s ESL performance (Diff = 1.42, p > .10), maternal effect – children’s ESL performance and siblings – children’s ESL performance (Diff = 1.42, p > .10), and paternal effect – children’s ESL performance and siblings – children’s ESL performance (Diff = 1.58, p > .05) were not statistically significant. Regarding the maternal effect-children’s ESL performance links, non-alphabetical script as L1 has similar effect size with alphabetic script as LI (Diff = 1.11, p > .05).

Discussion

This study performed a series of meta-analyses on 18 articles (N = 4401) on the association between HLE factors and children’s ESL performance. Regarding performance in English receptive vocabulary, three main results were found. Firstly, moderate effect sizes on ESL performance were found across HLE factors, except parental beliefs, which showed a small effect size. Secondly, parental literacy teaching behaviors exert a greater effect on children’s ESL performance than learning resources and parental beliefs. Lastly, paternal, maternal, and sibling’s effect sizes were similar.

Effects of HLE factors on children’s ESL performance

The correlation effect sizes between HLE factors and children’s ESL performance were largely moderate, except for the association between parental beliefs and children’s ESL performance which had a small effect size. This finding was different from that of studies that reported that HLE has a strong link with children’s language acquisition (Rodriguez & Tamis-lemonda, Citation2011). Two potential reasons can explain this finding. First, this study focused on receptive vocabulary, whereas the past studies that reported a high correlation between home literacy support and children’s language acquisition focused on children’s reading or speaking ability. Second, past studies focus on L1 learning, whereas the present study revealed the correlation on ESL performance. ESL learning tends to depend on a wide range of factors, such as school support, which may reduce the effect size of HLE factors. Previous studies (e.g., Zhu et al., Citation2014) reported that the language cognitive load pattern was different between L1 and L2. The findings highlight the importance of understanding how factors outside the family influence children’s language learning especially in learning a second language.

Comparisons across HLE factors

The present findings demonstrated that the effect size of parental literacy teaching behaviors (i.e., parental involvement and shared reading) was significantly stronger than HLE resources and parental beliefs on children’s ESL performance. This result is consistent with that of previous studies, which showed that parents play a vital role in children’s literacy development and language acquisition than literacy learning resources (Hagen et al., Citation2011; Martini & Sénéchal, Citation2012). The results demonstrate that relevant literacy learning materials and interaction between children and their family members on literacy activities are important for children’s ESL performance, but parental literacy teaching behaviors effect is the strongest and parents play a unique role in enhancing children’s ESL performance among all variables. The findings indicated that merely having home literacy resources at home does not enhance children’s ESL acquisition in the most effective way. Parents who use these resources with their children (e.g., shared reading) can maximize the learning effects for children. Through these interactions, children can acquire more knowledge from parents’ behaviors, when they imitate parents’ word pronunciations or attitudes on ESL learning (e.g., St Pierre et al., Citation2005).

Parental literacy teaching behaviors (e.g., parent–children’s ESL storybook reading) have a larger effect size than parental beliefs on children’s ESL performance. This result is consistent with those of past studies (Rogers et al., Citation2012; Weisleder & Fernald, Citation2013). The present study provides evidence that parental literacy teaching behaviors benefit children more than parental beliefs on ESL performance. The interaction between children and parents in ESL activities creates more literacy opportunities for children to enhance their ESL literacy development.

The present study shows a moderate effect size level of parental involvement, whereas other studies show large effect sizes of parental involvement. For example, Castro’s team (Castro et al., Citation2015) synthesized 37 studies and reported that parental involvement has a large effect size on children’s academic learning. The difference between the current study and that of Castro et al. (Citation2015) may be due to the focus on different learning outcome measurements. Castro et al. (Citation2015) measured general learning outcomes, including literature, math, and science and technology, and more than 90% of the outcome measurements were science subjects. By contrast, the present study focused on ESL performance.

Family members’ effects

The current study showed similar effect sizes on children’s ESL performance in paternal, maternal, and sibling effects. This finding is consistent with that of previous studies on L1 acquisition. Past studies showed that family members had moderate contribution to home literacy environment and other family member’s language acquisition (Duursma et al., Citation2007; Malmberg et al., Citation2016). However, our finding echoed a previous meta-analysis on the different paternal and maternal effects on children’s language learning (Leaper et al., Citation1998). Most of the time, children engaged in more verbal interaction with their mothers than their fathers (Pancsofar & Vernon-Feagans, Citation2006; Topping et al., Citation2013). However, a father’s input is still important. Fathers influence children’s behavior, cognition, and development (Fagan & Iglesias, Citation1999). Parents influence children’s language development in different ways, in which paternal contributions are mainly expressed through communication (such as humorous speaking style), interactive communication with children on specific topics, and support on children’s creative behaviors (e.g., Lovas, Citation2011). In addition, paternal factors can influence children’s language development through the effects of other family members. For instance, paternal education consistently predicts the frequency of mother–children’s engagement (Tamis-lemonda et al., Citation2004). Last but not least, siblings’ interactions are important to children’s language learning. Siblings interact with each other, and help correct each other’s language mistakes. For example, Kheirkhah and Cekaite (Citation2018) indicated that siblings corrected family members’ errors in language use and grammar choices. Further studies could investigate the mechanisms of these effects of family members.

Moreover, the current study further compared the correlation of maternal effect – children’s ESL performance between non-alphabetical script as L1 (e.g., Chinese) and alphabetic script as L1 (e.g., Spanish). The results showed that the correlation was smaller for non-alphabetical script than alphabetic script but this difference was not statistically significant. Previous studies showed that the higher the similarity in grammar and words’ structure (morphology, phonology, orthographical rule) in L1 and L2, the greater the contribution of L1 to L2 knowledge acquisition (Pasquarella et al., Citation2011; Y. S. G. Kim & Piper, Citation2019). Taken together, these results of alphabetic and non-alphabetic scripts suggest that maternal factors play an important role in children’s ESL learning regardless of the different degree of similarity between the characteristics in their L1 and English.

Limitations and future directions

The current meta-analysis has five main limitations. First, the different measures employed in the reviewed studies may have different levels of reliability, which may place constraints on correlations with criterion measures. Large measurement errors may result in low correlations (Hunter et al., Citation1990). Second, the present study only selected articles written in English. Academic articles written in other languages were not reported. Thirdly, the current study did not separate the HLE effects on different language aspects. Future studies can test more specific effects between HLE and aspects of children’s ESL performance, such as speaking, listening, reading, and writing. Next, as the number of existing studies on HLE and ESL is small, the number of variables to be tested in this meta-analysis is limited. Future studies can examine the possible moderating role of different factors, such as English learning experience at school and English proficiency of family members, in order to provide a more comprehensive picture of the factors influencing the links between HLE and ESL.

Conclusion

This meta-analysis has shown that correlation effect sizes between HLE factors and children’s ESL performance are from small to moderate. The findings emphasize the important role of family members in children’s ESL development, and indicate that parental involvement can be the key to maximizing the usefulness of HLE resources in fostering children’s ESL development. The current meta-analysis highlights the contribution of HLE to children’s ESL acquisition and the prominence of taking the relative contributions of different HLE factors into account in ESL research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- *Author. (2017). Differential influences of parental home literacy practices and anxiety in English as a foreign language on Chinese children’s English development. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 20(6), 625–637. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2015.1062468

- *Baker, C. E. (2014). Mexican mothers’ English proficiency and children’s school readiness: Mediation through home literacy involvement. Early Education and Development, 25(3), 338–355. https://doi.org/10.1080/10409289.2013.807721

- Baker, L., & Scher, D. (2002). Beginning readers’ motivation for reading in relation to parental beliefs and home reading experiences. Reading Psychology, 23(4), 239–269. https://doi.org/10.1080/713775283

- *Bitetti, D., & Hammer, C. S. (2016). The home literacy environment and the English narrative development of Spanish–English Bilingual children. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 59(5), 1159–1171. https://doi.org/10.1044/2016_JSLHR-L-15-0064

- Borenstein, M., Hedges, L. V., Higgins, J. P., & Rothstein, H. R. (2009). Converting among effect sizes. Introduction to meta-analysis (pp. 45-49). https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470743386

- Bracken, S. S., & Fischel, J. E. (2008). Family reading behavior and early literacy skills in preschool children from low-income backgrounds. Early Education and Development, 19(1), 45–67. https://doi.org/10.1080/10409280701838835

- *Branum-Martin, L., Mehta, P. D., Carlson, C. D., Francis, D. J., & Goldenberg, C. (2014). The nature of Spanish versus English language use at home. Journal of Educational Psychology, 106(1), 181–199. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033931

- Bruin, M. (2018). Parental involvement in children’s learning: The case of cochlear implantation—parents as educators?. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 62(4), 601–616. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2016.1258728

- Burgess, A. (1998). Fatherhood reclaimed: The making of the modern father. Random House (UK). Vermilion.

- Burgess, S. R., Hecht, S. A., & Lonigan, C. J. (2002). Relations of the home literacy environment (HLE) to the development of reading-related abilities: A one-year longitudinal study. Reading Research Quarterly, 37(4), 408–426. https://doi.org/10.1598/RRQ.37.4.4

- *Butler, Y. G. (2014). Parental factors and early English education as a foreign language: A case study in Mainland China. Research Papers in Education, 29(4), 410–437. https://doi.org/10.1080/02671522.2013.776625

- Butler, Y. G., & Le, V.-N. (2018). A longitudinal investigation of parental social-economic status (SES) and young students’ learning of English as a foreign language. System, 73, 4–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2017.07.005

- Caesar, L. G., & Nelson, N. W. (2014). Parental involvement in language and literacy acquisition: A bilingual journaling approach. Child Language Teaching and Therapy, 30(3), 317–336. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265659013513028

- Castro, M., Expósito-Casas, E., López-Martín, E., Lizasoain, L., Navarro-Asencio, E., & Gaviria, J. L. (2015). Parental involvement on student academic achievement: A meta-analysis. Educational Research Review, 14, 33–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2015.01.002

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioural sciences (2nd ed.). L. Erlbaum Associates.

- Davidson, P., Rushton, C. H., Kurtz, M., Wise, B., Jackson, D., Beaman, A., & Broome, M. (2018). A social–ecological framework: A model for addressing ethical practice in nursing. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 27(56), e1233–e1241. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.14158

- Debaryshe, B. D. (1993). Joint picture-book reading correlates of early oral language skill. Journal of Child Language, 20(2), 455–461. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305000900008370

- Deckner, D. F., Adamson, L. B., & Bakeman, R. (2006). Child and maternal contributions to shared reading: Effects on language and literacy development. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 27(1), 31–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2005.12.001

- DesJardin, J. L., Stika, C. J., Eisenberg, L. S., Johnson, K. C., Ganguly, D. M. H., Henning, S. C., & Colson, B. G. (2017). A longitudinal investigation of the home literacy environment and shared book reading in young children with hearing loss. Ear and Hearing, 38(4), 441–454. https://doi.org/10.1097/AUD.0000000000000414

- Dickinson, D. K., & Tabors, P. O. (2001). Beginning literacy with language: Young children learning at home and school. Paul H Brookes Publishing.

- Dixon, L. Q., & Wu, S. (2014). Home language and literacy practices among immigrant second-language learners. Language Teaching, 47(4), 414–449. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444814000160

- Dong, Y., Chow, B. W.-Y., Wu, S. X.-ying, Zhou, J.-D., & Zhao, Y. M. (2020a). Enhancing poor readers’ reading comprehension ability through word semantic knowledge training. Reading & Writing Quarterly, 37(4), 348–364. https://doi.org/10.1080/10573569.2020

- Dong, Y., Wu, S. X.-Y., Dong, W.-Y., & Tang, Y. (2020b). The effects of home literacy environment on children’s reading comprehension development: A meta-analysis. Educational Sciences: Theory & Practice, 20(2), 63–82. https://doi.org/10.12738/jestp.2020.2.005

- Dong, Y., Tang, Y., Chow, B. W.-Y., Wang, W., & Dong, W.-Y. (2020c). Contribution of vocabulary knowledge to reading comprehension among Chinese students: A meta-analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.525369

- *Duursma, E., Romero-Contreras, S., Szuber, A., Proctor, P., Snow, C., August, D., & Calderón, M. (2007). The role of home literacy and language environment on bilinguals’ English and Spanish vocabulary development. Applied Psycholinguistics, 28(1), 171–190. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0142716406070093

- Elley, W. B., & Mangubhai, F. (1983). The impact of reading on second language learning. Reading Research Quarterly, 19(1), 53–67. https://doi.org/10.2307/747337

- Evans, M. A., Fox, M., Cremaso, L., & McKinnon, L. (2004). Beginning reading: The views of parents and teachers of young children. Journal of Educational Psychology, 96(1), 130–141. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.96.1.130

- Fagan, J., & Iglesias, A. (1999). Father involvement program effects on fathers, father figures, and their Head Start children: A quasi-experimental study. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 14(2), 243–269. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0885-2006(99)00008-3

- *Farver, J. A. M., Xu, Y., Eppe, S., & Lonigan, C. J. (2006). Home environments and young Latino children’s school readiness. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 21(2), 196–212. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2006.04.008

- *Farver, J. A. M., Xu, Y., Lonigan, C. J., & Eppe, S. (2013). The home literacy environment and Latino head start children’s emergent literacy skills. Developmental Psychology, 49(4), 775–791. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028766

- Fisher, D. (2019). ADMETAN: Stata module to provide comprehensive meta-analysis. Boston College Department of Economics.

- Flouri, E., & Buchanan, A. (2004). Early father’s and mother’s involvement and child’s later educational outcomes. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 74(2), 141–153. https://doi.org/10.1348/000709904773839806

- Forey, G., Besser, S., & Sampson, N. (2016). Parental involvement in foreign language learning: The case of Hong Kong. Journal of Early Childhood Literacy, 16(3), 383–413. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468798415597469

- Frijters, J. C., Barron, R. W., & Brunello, M. (2000). Direct and mediated influences of home literacy and literacy interest on prereaders’ oral vocabulary and early written language skill. Journal of Educational Psychology, 92(3), 466–477. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.92.3.466

- García, J. R., & Cain, K. (2014). Decoding and reading comprehension: A meta-analysis to identify which reader and assessment characteristics influence the strength of the relationship in English. Review of Educational Research, 84(1), 74–111. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654313499616

- *Gonzalez, J. E., & Uhing, B. M. (2008). Home literacy environments and young Hispanic children’s English and Spanish oral language: A communality analysis. Journal of Early Intervention, 30(2), 116–139. https://doi.org/10.1177/1053815107313858

- Grépin, K. A., & Bharadwaj, P. (2015). Maternal education and child mortality in Zimbabwe. Journal of Health Economics, 44, 97–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2015.08.003

- Hagen, K. A., Ogden, T., & Bjørnebekk, G. (2011). Treatment outcomes and mediators of parent management training: A one-year follow-up of children with conduct problems. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 40(2), 165–178. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2011.546050

- Harkness, S., & Super, C. M. (1992). Parental belief systems: The psychological consequences for children. Journal of Marriage and Family, 54(4), 373–392. https://doi.org/10.2307/353190

- He, T.-hsien, Gou, W. J., & Chang, S.-mao. (2015). Parental involvement and elementary school students' goals, maladaptive behaviors, and achievement in learning English as a foreign language. Learning and Individual Differences, 39, 205–210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2015.03.011

- Hedges, L. V., & Olkin, I. (1985). Statistical methods for meta-analysis. Academic Pres.

- Hemilä, H. (2017). Publication bias in meta-analysis of ascorbic acid for postoperative atrial fibrillation. American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy, 74(6), 372–373. https://doi.org/10.2146/ajhp160999

- Hosseinpour, V., Sherkatolabbasi, M., & Yarahmadi, M. (2015). The impact of parents’ involvement in and attitude toward their children’s foreign language programs for learning English. International Journal of Applied Linguistics and English Literature, 4(4), 175–185. https://doi.org/10.7575/aiac.ijalel.v.4n.4p.175

- *Howard, E. R., Páez, M. M., August, D. L., Barr, C. D., Kenyon, D., & Malabonga, V. (2014). The importance of SES, home and school language and literacy practices, and oral vocabulary in bilingual children’s English reading development. Bilingual Research Journal, 37(2), 120–141. https://doi.org/10.1080/15235882.2014.934485

- Hunter, J. E., Schmidt, F. L., & Judiesch, M. K. (1990). Individual differences in output variability as a function of job complexity. Journal of Applied Psychology, 75(1), 28–42. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.75.1.28

- *Kalia, V., & Reese, E. (2009). Relations between Indian children’s home literacy environment and their English oral language and literacy skills. Scientific Studies of Reading, 13(2), 122–145. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888430902769517

- Kheirkhah, M., & Cekaite, A. (2018). Siblings as language socialization agents in bilingual families. International Multilingual Research Journal, 12(4), 255–272. https://doi.org/10.1080/19313152.2016.1273738

- *Kim, J. S., & Guryan, J. (2010). The efficacy of a voluntary summer book reading intervention for low-income Latino children from language minority families. Journal of Educational Psychology, 102(1), 20–31. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017270

- Kim, Y.-S. G. (2020). Hierarchical and dynamic relations of language and cognitive skills to reading comprehension: Testing the direct and indirect effects model of reading (DIER). Journal of Educational Psychology, 112(4), 667–684. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000407

- Kim, Y. S. G., & Piper, B. (2019). Cross-language transfer of reading skills: An empirical investigation of bidirectionality and the influence of instructional environments. Reading and Writing, 32(4), 839–871. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-018-9889-7

- Leaper, C., Anderson, K. J., & Sanders, P. (1998). Moderators of gender effects on parents’ talk to their children: A meta-analysis. Developmental Psychology, 34(1), 3–27. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.34.1.3

- *Lewis, K., Sandilos, L. E., Hammer, C. S., Sawyer, B. E., & Méndez, L. I. (2016). Relations among the home language and literacy environment and children’s language abilities: A study of head start dual language learners and their mothers. Early Education and Development, 27(4), 478–494. https://doi.org/10.1080/10409289.2016.1082820

- Lipsey, M. W., & Wilson, D. (2001). Practical meta-analysis.Applied Social ResearchMethods Series, Vol. 49, Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc

- Lovas, G. S. (2011). Gender and patterns of language development in mother-toddler and father-toddler dyads. First Language, 31(1), 83–108. https://doi.org/10.1177/0142723709359241

- Malmberg, L. E., Lewis, S., West, A., Murray, E., Sylva, K., & Stein, A. (2016). The influence of mothers’ and fathers’ sensitivity in the first year of life on children’s cognitive outcomes at 18 and 36 months. Child: Care, Health and Development, 42(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/cch.12294

- Martini, F., & Sénéchal, M. (2012). Learning literacy skills at home: Parent teaching, expectations, and child interest. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science, 44(3), 210–221. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0026758

- McShane, B. B., Böckenholt, U., & Hansen, K. T. (2016). Adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis: An evaluation of selection methods and some cautionary notes. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 11(5), 730–749. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691616662243

- Meng, C. (2015). Home literacy environment and head start children’s language development: The role of approaches to learning. Early Education and Development, 26(1), 106–124. https://doi.org/10.1080/10409289.2015.957614

- Mol, S. E., & Bus, A. G. (2011). To read or not to read: A meta-analysis of print exposure from infancy to early adulthood. Psychological Bulletin, 137(2), 267–296. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021890

- *Mori, Y., & Calder, T. M. (2017). The role of parental support and family variables in L1 and L2 vocabulary development of Japanese heritage language students in the United States. Foreign Language Annals, 50(4), 754–775. https://doi.org/10.1111/flan.12304

- Niehaus, K., & Adelson, J. L. (2014). School support, parental involvement, and academic and social-emotional outcomes for English language learners. American Educational Research Journal, 51(4), 810–844. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831214531323

- Niklas, F., Cohrssen, C., & Tayler, C. (2016). The sooner, the better: Early reading to children. Sage Open, 6(4), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244016672715

- Niklas, F., Wirth, A., Guffler, S., Drescher, N., & Ehmig, S. C. (2020). The home literacy environment as a mediator between parental attitudes toward shared reading and children’s linguistic competencies. Frontiers in Psychology, 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01628

- Oller, J. (2014). Empowering immigrant women through bilingual fairy tales: Linking family and school literacy practices. Culturay Educación, 26(1), 203–210. https://doi.org/10.1080/11356405.2014.908669

- Pancsofar, N., & Vernon-Feagans, L. (2006). Mother and father language input to young children: Contributions to later language development. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 27(6), 571–587. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2006.08.003

- Pasquarella, A., Chen, X., Lam, K., Luo, Y. C., & Ramirez, G. (2011). Cross‐language transfer of morphological awareness in Chinese–English bilinguals. Journal of Research in Reading, 34(1), 23–42. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9817.2010.01484.x

- Pungello, E. P., Iruka, I. U., Dotterer, A. M., Mills-Koonce, R., & Reznick, J. S. (2009). The effects of socioeconomic status, race, and parenting on language development in early childhood. Developmental Psychology, 45(2), 544–557. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013917

- Qureshi, J. A. (2018). Siblings, teachers, and spillovers on academic achievement. Journal of Human Resources, 53(1), 272–297. https://doi.org/10.3368/jhr.52.1.0815-7347R1

- *Roberts, T. A. (2008). Home storybook reading in primary or second language with preschool children: Evidence of equal effectiveness for second-language vocabulary acquisition. Reading Research Quarterly, 43(2), 103–130. https://doi.org/10.1598/RRQ.43.2.1

- Rodriguez, E. T., & Tamis-lemonda, C. S. (2011). Trajectories of the home learning environment across the first 5 years: Associations with children’s vocabulary and literacy skills at prekindergarten. Child Development, 82(4), 1058–1075. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01614.x

- Rogers, S. J., Estes, A., Lord, C., Vismara, L., Winter, J., Fitzpatrick, A., Guo, M., & Dawson, G. (2012). Effects of a brief early start denver model (ESDM)–based parent intervention on toddlers at risk for autism spectrum disorders: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 51(10), 1052–1065. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2012.08.003

- Sénéchal, M., & LeFevre, J. A. (2002). Parental involvement in the development of children’s reading skill: A five year longitudinal study. Child Development, 73(2), 445–460. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00417

- Sénéchal, M., & LeFevre, J. A. (2014). Continuity and change in the home literacy environment as predictors of growth in vocabulary and reading. Child Development, 85(4), 1552–1568. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12222

- Sénéchal, M., Lefevre, J. A., Thomas, E. M., & Daley, K. E. (1998). Differential effects of home literacy experiences on the development of oral and written language. Reading Research Quarterly, 33(1), 96–116. https://doi.org/10.1598/RRQ.33.1.5

- Sénéchal, N., Sottolichio, A., Bertrand, F., Goeldner-Gianella, L., & Garlan, T. (2013). Observations of waves’ impact on currents in a mixed-energy tidal inlet: Arcachon on the southern French Atlantic coast. Journal of Coastal Research, 65(sp2), 2053–2058. https://doi.org/10.2112/SI65-347.1

- Sigel, I. E., Lisi, M. D., & Ann, V. (2002). Parent beliefs are cognitions: The dynamic belief systems model. In M. H. Bornstein Ed., Handbook of parenting (2nd ed., Vol. 3) pp.485–508. Erlbaum.

- Snow, K. L. (2006). Measuring school readiness: Conceptual and practical considerations. Early Education and Development, 17(1), 7–41. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15566935eed1701_2

- Sonnenschein, S., Baker, L., Serpell, R., Scher, D., Truitt, V. G., & Munsterman, K. (1997). Parental beliefs about ways to help children learn to read: The impact of an entertainment or a skills perspective. Early Child Development and Care, 127(1), 111–118. https://doi.org/10.1080/0300443971270109

- St Pierre, R. G., Ricciuti, A. E., & Rimdzius, T. A. (2005). Effects of a family literacy program on low-literate children and their parents: Findings from an evaluation of the even start family literacy program. Developmental Psychology, 41(6), 953–970. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.41.6.953

- Tamis-lemonda, C. S., Shannon, J. D., Cabrera, N. J., & Lamb, M. E. (2004). Fathers and mothers at play with their 2-and 3-year-olds: Contributions to language and cognitive development. Child Development, 75(6), 1806–1820. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00818.x

- Tanner-Smith, E. E., & Tipton, E. (2014). Robust variance estimation with dependent effect sizes: Practical considerations including a software tutorial in Stata and SPSS. Research Synthesis Methods, 5(1), 13–30. https://doi.org/10.1002/jrsm.1091

- Tanner-Smith, E. E., Tipton, E., & Polanin, J. R. (2016). Handling complex meta-analytic data structures using robust variance estimates: A tutorial in R. Journal of Developmental and Life-Course Criminology, 2(1), 85–112. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40865-016-0026-5

- Topping, K., Dekhinet, R., & Zeedyk, S. (2013). Parent–infant interaction and children’s language development. Educational Psychology, 33(4), 391–426. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2012.744159

- *Trainin, G., Wessels, S., Nelson, R., & Vadasy, P. (2017). A study of home emergent literacy experiences of young latino english learners. Early Childhood Education Journal, 45(5), 651–658. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-016-0809-7

- Tunmer, W. E., & Chapman, J. W. (2012). The simple view of reading redux: Vocabulary knowledge and the independent components hypothesis. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 45(5), 453–466. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022219411432685

- Varghese, C., & Wachen, J. (2016). The determinants of father involvement and connections to children’s literacy and language outcomes: Review of the literature. Marriage & Family Review, 52(4), 331–359. https://doi.org/10.1080/01494929.2015.1099587

- Wang, Y. (2015). A trend study of the influences of parental expectation, parental involvement, and self-efficacy on the English academic achievement of Chinese eighth graders. International Education, 44(2), 45–68. https://lbapp01.lib.cityu.edu.hk/ezlogin/index.aspx?url=https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/trend-study-influences-parental-expectation/docview/1674721773/se-2?accountid=10134

- Weigel, D. J., Martin, S. S., & Bennett, K. K. (2006). Contributions of the home literacy environment to preschool-aged children’s emerging literacy and language skills. Early Child Development and Care, 176(34), 357–378. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430500063747

- Weigel, D. J., Martin, S. S., & Bennett, K. K. (2010). Pathways to literacy: Connections between family assets and preschool children’s emergent literacy skills. Journal of Early Childhood Research, 8(1), 5–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/1476718X09345518

- Weisleder, A., & Fernald, A. (2013). Talking to children matters: Early language experience strengthens processing and builds vocabulary. Psychological Science, 24(11), 2143–2152. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797613488145

- *Yeung, S. S., & King, R. B. (2016). Home literacy environment and English language and literacy skills among Chinese young children who learn English as a second language. Reading Psychology, 37(1), 92–120. https://doi.org/10.1080/02702711.2015.1009591

- Zhu, L., Nie, Y., Chang, C., Gao, J. H., & Niu, Z. (2014). Different patterns and development characteristics of processing written logographic characters and alphabetic words: An ALE meta‐analysis. Human Brain Mapping, 35(6), 2607–2618. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbm.22354