Abstract

This article investigates the internal dynamics of the Anthropocene Working Group (AWG), an expert body tasked with evaluating the stratigraphic case of the Anthropocene. The investigation focuses on the role of interdisciplinarity and disciplinarity in the AWG. The article draws on surveys and interviews with AWG members to characterize interdisciplinary collaboration in the AWG and discusses the relationship of the AWG to the stratigraphic community. The results reveal that the exchanges between disciplines in the AWG are ‘multidisciplinary’ and of limited scope. While social scientists in the group take a non-scientific role, the involvement of natural scientists in research activities is guided by the objectives of stratigraphy. Moreover, a lack of communication and trust had shaped the relationship between the AWG and the stratigraphic community until they devised pragmatic working arrangements that led the AWG to adapt its research practice and rationale. Despite calls to reform stratigraphic practice, the disciplinarity of the AWG prevails over innovative research practices inspired by interdisciplinary exchanges. In terms of theory, the study confirms that disciplines continue to provide the context in which interdisciplinary endeavors need to position themselves. Notwithstanding the pull of interdisciplinarity, the AWG’s main point of reference remains the stratigraphic community.

Introduction

As applications of the term multiply, the Anthropocene is becoming a keyword in debates about contemporary environmental change. Ever since the idea was raised in the Earth system sciences to describe the extension of resource exploitation by humans (Crutzen and Stoermer Citation2000), many other fields of studying socio-ecological systems have embraced the term. They include biology (Kidwell Citation2015), anthropology (Gibson and Venkateswar Citation2015), literary studies (Clark Citation2015), and social theory (Delanty and Mota Citation2017). While Earth system and other natural scientists have studied the effects of human activities on the Earth system as a whole (e.g. Steffen et al. Citation2015), social scientists have accentuated the interactions between specific social relations and their environments (e.g. Malm and Hornborg Citation2014), and humanities scholars have highlighted the inherent connections between the animate and the inanimate world (e.g. Yusoff Citation2013). The discussions in different communities have diversified the meaning of the Anthropocene, creating a heterogeneous discursive space.

The prevalence of the Anthropocene has been reviewed critically (Lorimer Citation2017; Swanson, Bubandt, and Tsing Citation2015). This engagement has included research practices that render the Anthropocene a knowable phenomenon and thus enable wide debates about it (Lövbrand, Stripple, and Wiman Citation2009; Cook and Balayannis Citation2015; Wissenburg Citation2016). Stratigraphy is particularly important in this regard because its research on the Anthropocene is replicated in many academic and public discourses. Accordingly, observers of the Anthropocene discourse have reflected on stratigraphic research related to the Anthropocene (Szerszynski Citation2012; Braje Citation2015; Monastersky Citation2015; Rickards Citation2015; Swanson Citation2016; Clark Citation2017; Warde, Robin, and Sörlin Citation2017). But the group that drives Anthropocene research in stratigraphy, the so-called Anthropocene Working Group (AWG), has not yet been studied in depth. This article fills this gap by analyzing the research practice of the AWG.

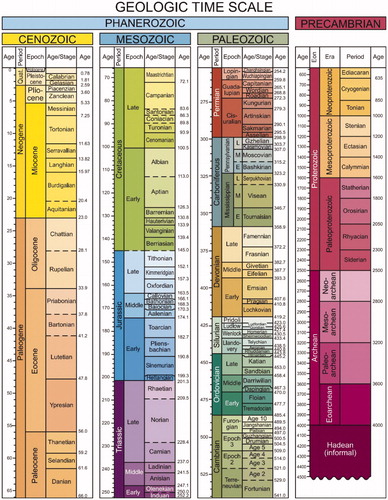

The AWG was established in 2009 as a working group within the International Commission on Stratigraphy (ICS), which regulates the way in which the time, name, rank, and stratigraphic markers of new geological periods are approved (Ogg Citation2004). Many such working groups exist, tasked with selecting and defining the boundaries between geological units (International Geological Union Citation2002), but they have no final decision-making power. They are temporary bodies (normally eight years) whose members report their work to the subcommissions under which they reside. Which boundaries are officially adopted for the Geological Timescale (see ) is eventually decided by the executive committee of the International Union of Geological Sciences (Finney and Edwards Citation2016b). Accordingly, the AWG is the first among several expert bodies that will examine and debate the geological case of the Anthropocene. The AWG has been preparing a formal proposal to its parenting Subcommission on Quaternary Stratigraphy (SQS) and the stratigraphic community at large. Although a preliminary recommendation was widely noticed when presented in 2016 at the International Geological Congress (Zalasiewicz and Waters Citation2016), the process of formalization is ongoing (Zalasiewicz et al. Citation2017).

Figure 1. The Geological Time Scale (Gradstein et al. Citation2012).

Institutions such as the AWG serve to accredit emerging bodies of knowledge and they are thus important research areas of science and technology studies (STS). In the words of Sheila Jasanoff (Jasanoff Citation2014, p. 40): ‘[w]hen environmental knowledge changes,…new institutions emerge to provide the web of social and normative understandings within which new characterizations of nature…can be recognized and given political effect’. The research of the AWG affects how people conceive the Anthropocene discourse because it is currently the only body that officially examines whether or not the Anthropocene Epoch exists. Although it is a temporary body and has limited decision-making power even in the field of stratigraphy, the AWG makes for the most visible representative of stratigraphic expertise, which ‘is widely acknowledged to hold “legitimate power to define, describe and explain” (Gieryn Citation1999, p. 1) what the Anthropocene is’ (Lundershausen Citation2018, p. 9). In this vein, the AWG is an important vehicle for developing knowledge (and action) regarding the Anthropocene.

Research question

While the AWG can be examined from several angles, this article focuses on the disciplinarity and interdisciplinarity of the AWG. It asks to what extent the AWG is interdisciplinary and what its relationship with its parent discipline stratigraphy is. Published debates about the Anthropocene and global change research suggest that interdisciplinarity characterizes the research practice of the AWG and that its relationship with the stratigraphic community is difficult.

It stands to reason that the AWG experiences a pull toward interdisciplinarity amid a wide discourse advocating interdisciplinary research (Nida-Rümelin Citation2005; Krohn Citation2012; Costanza Citation2013) particularly in studies of the Earth system (Cornell et al. Citation2012; Brasseur and van der Pluijm Citation2013; Pahl-Wostl et al. Citation2013). In the vein of this discourse, commentators often view the Anthropocene as a ‘bridge’ between disciplines (Nature Citation2011; Jahn, Hummel, and Schramm Citation2015; Brondizio et al. Citation2016, p. 318). For many, the term promises deeper (Berkhout Citation2014; Johnson et al. Citation2014; Castree Citation2017) and wider collaborations between different disciplines (Kotchen and Young Citation2007; Palsson et al. Citation2013; Johnson et al. Citation2014). Mirroring this hope, all three journals holding Anthropocene in their titles advocate and claim an interdisciplinary approach.1

The membership of the AWG suggests that this pull has affected the AWG. It unconventionally comprises a large group of 35 members with a great variety of disciplinary backgrounds (Zalasiewicz, Waters, and Head Citation2017). Although the members of other ICS working groups are diverse to the extent that they represent the methodological diversity in stratigraphy, the AWG is different in that only half of its members have official training in geology (Nature Citation2015). Some of them are trained in the social sciences such as law or communication studies. This diversity could be justified with the unusual character of the Anthropocene, the stratigraphic study of which ostensibly benefits from insights of other disciplines about environmental change on the Earth surface (Zalasiewicz et al. Citation2010; Steffen et al. Citation2016).

But while some geoscientists deem it necessary to include social scientists and humanities scholars in the stratigraphic ratification process of the Anthropocene (Ellis et al. Citation2016), others have defended the separation between a stratigraphic definition of the Anthropocene as a geological epoch and definitions of the Anthropocene advanced by other disciplines (Maslin and Lewis Citation2015; Finney and Edwards Citation2016a). Within the stratigraphic community, the value of stratigraphic research on the Anthropocene, generally, and the way it has been conducted by the AWG, specifically, is controversial due to concerns that it does not follow established stratigraphic practice (Autin and Holbrook Citation2012; Finney and Edwards Citation2016b). These published debates suggest that the standing of the AWG in the stratigraphic community is imperfect.

The co-constitution of disciplines and interdisciplinarity

The abovementioned debates in Anthropocene geoscience reflect concerns in the theoretical literature about the apparent tension between interdisciplinary research and disciplines. This tension is illustrated by the common usage of the abstract noun for ‘interdisciplinarity’ and the concrete noun for ‘discipline’, which indicates that interdisciplinary research is often seen as theoretically and methodologically open, whereas disciplinary research is regularly portrayed as stable and homogenous in these regards. This epistemic dichotomy has allowed advocates of disciplinary research and its interdisciplinary critics to argue, respectively, that disciplines enable or restrict the production of scientific knowledge (Schaffner Citation2014). Characterizing the disciplinarity and interdisciplinarity of the AWG can contribute to two central concerns of this literature.

First, studying the AWG reveals if the epistemic dichotomy is justified or if disciplinarity and interdisciplinarity are actually co-constituted as increasingly popular terms like ‘inter-discipline’ and ‘disciplinarity’ suggest. These terms are the result of work which demonstrates that disciplines are often internally divided (Potthast Citation2010) and that their external boundaries are porous (Osborn Citation2014). Julie Thompson Klein (Citation1996) has prominently argued that the crossing of disciplinary boundaries is an intrinsic part of the formation of disciplines and epistemic innovation within them. Klein contends that the very criteria used to demarcate boundaries between disciplines (such as material fields and problems, analytical tools and methods, or theories, laws, and concepts) also connect different disciplinary practices. Consequently, disciplines and interdisciplinarity are increasingly recognized as co-constituted. Huutoniemi et al. (Citation2010, p. 80) argue that the ‘fundamental challenge of creating a valid measure of interdisciplinarity originates from the complexity of identifying a discipline in a conceptually and empirically acceptable way’.

Second, the study of the AWG can contribute to understanding the degree of social and organizational competition between established disciplines and emerging fields of interdisciplinary research. The STS literature, even when it has questioned the epistemic dichotomy, has highlighted this competition by examining both the established influence of disciplines in the social order of knowledge production and the challenges that interdisciplinary research poses to it. Barry, Born, and Weszkalnys (Citation2008, p. 20–21) comprehensibly describe the ensuing tension in the following way:

Disciplines discipline disciples. [They] ensur[e] that certain disciplinary methods and concepts are used rigorously and that undisciplined and undisciplinary objects, methods and concepts are ruled out. By contrast, ideas of interdisciplinarity…imply…that the disciplinary and disciplining rules, trainings and subjectivities given by existing knowledge corpuses are put aside or superseded.

Disciplines, though diverse in size and structure, are institutions with a historically developed, officially recognized and institutionalized capacity to influence scientific knowledge production (Stehr and Weingart Citation2000). Disciplines are powerful particularly because they are able to police and effectively stabilize scientific communication, for example, through disciplinary journals for peer review and scientific associations that control the nomenclature of and accreditation to a field of study (Weingart, Carrier, and Krohn Citation2015). As a result, the main point of reference and accountability for scientists is often their disciplinary community.

Gibbons et al. (Citation1994) have prominently argued that interdisciplinary research challenges this social order established by disciplines. They state that the pluralization of scientific knowledge production has weakened the monopoly of disciplines. Recent commentators add that science, especially climate science (Beck Citation2012), is increasingly expected to be accountable not just to the disciplinary communities but also to public and political communities that hold stakes in the validity of scientific claims (Jasanoff Citation2012). This ‘logic of accountability’ is such a prominent rationale for interdisciplinary practice that it has found its way into a seminal typology of the latter (Barry, Born, and Weszkalnys Citation2008).

In reality, the crossing of disciplinary boundaries is as much epistemically potent as it is socially challenging for disciplines. Particularly the literature on the specialization of disciplines shows that boundary-crossings hold a dual potential for strengthening existing disciplinary communities through internal innovation and for fragmenting them through the formation of new disciplines. Firstly, a discipline can evolve internally by developing a specialized research community that communicates in reference to its members as well as to the disciplinary community at large (Weingart, Carrier, and Krohn Citation2015). This internal specialization does not diminish the integrity of the discipline and can even support it by allowing for innovation in knowledge production, which creates a wider knowledge base on which the discipline rests (Klein Citation1996). A second form of discipline specialization occurs when groups of researchers start to disassociate themselves from their original disciplinary community. Specialized communities of researchers then build internal communicative connections that subvert those with the parent discipline or existing disciplines generally (Weingart, Carrier, and Krohn Citation2015, p. 44). As a result, a hybrid discipline (Klein Citation1996, p. 44) or inter-discipline can emerge that seeks to formally establish itself.

Methods: case study of the AWG

The investigation presented in this article builds on a qualitative case study of the AWG that set out to better understand stratigraphic practices in face of a wider Anthropocene discourse. The internal workings of the AWG, as well as their relation to outside communities and discourses, were major interests in the online survey and semi-structured interviews conducted with AWG members for this study. The resulting analysis is a qualitative case study of the Anthropocene Working Group. The insights provided are valuable not by way of being generalizable across research on the Anthropocene, stratigraphic or otherwise, but by being specific to a particular way of researching the Anthropocene (Clifford, French, and Valentine Citation2010). Although these insights are based on a small sample, their contextual nature can usefully complement theoretical accounts of interdisciplinary and disciplinarity. This study was initially prepared together with Jacob Barber (University of Edinburgh) and George Holmes (University of Leeds) to maximize access to AWG members and to increase the variety and quality of questions posed to them. The result of this collaboration was a pool of data that was subsequently used for separate research projects of the different researchers.2

The pool of data was generated in the following way. The secretary of the AWG, Colin Waters, kindly assisted in sampling participants by sharing the invitation to complete the survey with all AWG members. Although not all AWG members participated in this study (see ), the survey provided an overview of the diverse opinions within the group. To accommodate for the various areas of expertise in the group, the survey comprised 21 open-ended question, which inquired into the internal dynamics of the AWG, its influence on society, and the stratigraphy of the Anthropocene including its formalization as an official geological epoch. The semi-structured interviews complemented the rigid structure of the surveys that produce reliable results but raise questions about validity (Conrad and Schober Citation2010, p. 173). They add adequacy by providing a possibility for clarification both on behalf of the researcher and the respondents. The interview questions follow up on answers given in the survey. While these questions were prepared collaboratively, the interviews, which lasted between 38 and 126 minutes, were conducted individually by different researchers of the team.

Table 1. Number of participants.

The open-ended interviews enabled participants to provide their personal accounts of the AWG’s work. This approach is problematic to the extent that AWG members are part of a scientific elite capable of providing ‘the public relations side of events rather than their own opinion’ (Mikecz Citation2012, p. 484). However, the agency of participants in ‘actively construct[ing] the information provided in the interview’ is not exclusive to elite interviews and needs to be addressed generally (Faircloth Citation2012, p. 270). Applying critical judgment while taking participants’ accounts seriously is the right approach to this issue. This study reconstructed the statements of participants in comparison to each other and within the context of the Anthropocene debate. Contradictory statements could thus be revealed and greater meaning attributed to the individual perspectives of participants.

Qualitative content analysis (Schreier Citation2012) was chosen as an appropriate method to evaluate the pool of data. It systematically explores the content of a text by detecting themes in the material and specifying what is said about these themes by creating subcategories. I initially followed themes from a previous review of the published stratigraphic literature (Lundershausen Citation2018). In addition, I used an inductive approach to coding, following the concepts that emerged rather than applying pre-existing theoretical concepts to the material. As a result, new themes become apparent, including ‘the constitution of disciplinary communities’, ‘the meaning of interdisciplinary exchanges’ as well as ‘the engagement of science with the public and the media’. I ultimately focused on these themes, and reorganized the material that they comprised into two issues, i.e. ‘interdisciplinarity and disciplinarity’ and ‘the role of stratigraphy in Anthropocene discourse’. The choice to attend to interdisciplinary and disciplinarity in this article is informed by the abovementioned prevalence of proposals for interdisciplinary research as well as the controversy surrounding such proposals in the stratigraphic literature on the Anthropocene.

In the following section, I describe the accounts given by participants in this study. They reflect both on the benefits and limits of including researchers from disciplines other than stratigraphy in the AWG, and on the relationship between the AWG and the wider stratigraphic community. To be sure, the opinions of all participating AWG members have been carefully analyzed without seeking to ‘discover’ an unmediated group experience (Silverman Citation2011). The accounts of participants presented in the following, therefore, highlight possible ways in which the research practice of the AWG is understood by some of its members without claiming that these instances are necessarily commensurable. AWG researchers conduct most of their research outside of the AWG; their positions are therefore shaped as much by the context of their individual scientific work as by their common experience as members of the AWG. In this vein, I follow a phenomenographical approach (Larsson and Holmström Citation2007) that studies variations in peoples conceptions of AWG’s internal dynamics, especially its interdisciplinary and disciplinarity; this study, therefore, does not aim to discover the essence of this phenomenon.

Results

The benefits and limits of interdisciplinarity in the AWG

Participants gave various reasons why the involvement of non-stratigraphers in the AWG is beneficial but they were also concerned that this involvement may distract from stratigraphic matters. Notably, the stated reasons differ for the involvement of natural scientists and social scientists.

On the one hand, participants stated that natural scientists from disciplines other than stratigraphy were invited to join the AWG to provide additional information that could alleviate a possible bias of geology and gain greater confidence in stratigraphic knowledge. The most significant partner discipline in this regard is seen to be Earth system science, whose real-time observations of the Earth can scrutinize stratigraphers’ interpretations of the rock record (and vice versa). Data from Earth system science, so the participants, have been necessary particularly to develop a geochronological narrative of the Anthropocene. As such, the data have supported the AWG’s decision to move toward a mid-20th-century boundary of the Anthropocene. As stated, an advantage of including other natural scientists more broadly is that they can raise awareness within the AWG about the needs of researchers who ultimately use the Geological Time Scale. Accordingly, participants also consider other disciplines on whose ‘toes we are treading’.

On the other hand, participants regarded the inclusion of social scientists as advantageous because the latter has improved the exchange between the AWG and non-academic audiences. Firstly, social scientists have apparently helped to ‘translate’ AWG results for the public and disseminate information ‘to the wider world’. Particularly the journalist Andrew Revkin is used as an example because he has drafted AWG press releases in a strategic way so that information is communicated efficaciously. Secondly, social scientists have helped to raise awareness in the group about the wider Anthropocene discourse and about the social implications of their stratigraphic work. Here, the legal scholar Davor Vidas is explicitly mentioned because he has explained the legal implications of ratifying the Anthropocene.

Notwithstanding these beneficial contributions of other disciplines to discussions within the AWG, participants were concerned that the presence of non-stratigraphers (both natural and social scientists) distracts from stratigraphic matters. Interdisciplinarity may particularly impede the preparation of a formal proposal to the ICS, which is restricted to stratigraphic insights and requires the identification of concrete Global Stratotype Section and Points (GSSPs). One participant stated clearly that ‘the contribution of the non-geoscientists has resulted in distractions from the goal of the working group since they have not understood the factors that are required by the International Stratigraphic Code’. Accordingly, participants highlighted the limits of interdisciplinarity especially as the AWG moves toward submitting a formal proposal. The forthcoming attempt to position a geochronological narrative of the Anthropocene in sedimentary successions will require a greater focus on the stratigraphic expertise in the group. Consequently, participants contemplate whether the membership status of non-stratigraphers needs to be changed and their voting rights limited.

Notably, these concerns of participants exist parallel to abstract favorable statements that interdisciplinarity makes the AWG ‘a wonderful place to fly and debate new ideas’. For some participants, the AWG even exemplifies and provides a legacy for a constructive interdisciplinary exchange, in which researchers learn from each other’s different perspectives on the same phenomena. Regardless of the prospects of including non-stratigraphic insights into a formal proposal to the ICS, for these participants, the AWG offers ‘a safe space for people to amicably discuss, even very strong differences of opinion, and also not to be afraid to say that they do not know or do not understand something’.

The relationship of the AWG to the stratigraphic community

Regarding the relationship of the AWG with the wider stratigraphic community, participants argue that it has, until recently, been difficult. Simultaneously, they emphasize the value of a constructive relationship with other stratigraphers.

Participants point to difficulties in the relationship by reflecting on the criticism that the AWG has received for not adhering to established procedures in the stratigraphic community. Firstly, the AWG has been criticized by other geologists for not following the conventional dual hierarchy of stratigraphy. Although the latter requires geological units to be defined both in geochronological (GSSA) and chronostratigraphic (GSSP) terms, the AWG ‘tentatively’ suggested in 2015 to only use a GSSA for the Anthropocene. Secondly, some parts of the stratigraphic community think that the AWG should work ‘in a more closed environment’ and only report its final results. They are critical of the public approach that the AWG has taken by engaging the media and feeding preliminary results back into the scientific community.

The origins of this criticism are seen to lie in a lack of communication and a related lack of trust. Participants highlighted that the AWG and the geological community have often not engaged with each other directly. The work of the AWG has been conducted ‘almost independently’ even of its parent institutions, the ICS and SQS, with which it has communicated merely through short annual reports and the media. Consequently, the AWG has been unable both to engage some of its strongest critics, many of which have held prominent positions within these institutions and to learn about the formal requirements of the ICS and the SQS. By making this point, participants highlighted the lack of communication as a root cause of the abovementioned criticism. The lack of communication has also contributed to a lack of trust that manifests not directly in the abovementioned criticisms but in the associated allegation that the AWG is aiming to push for formalization by circumnavigating official procedures. Within the AWG, in turn, this allegation has strengthened the sentiment that it ‘can never win’ because its work is deliberately misinterpreted and unfairly criticized.

At the same time, participants emphasize that a constructive relationship with the stratigraphic community is crucial. Firstly, a constructive relationship with the wider community of stratigraphers would enable the AWG to collaborate with researchers who can provide needed stratigraphic analysis of sediment samples. Secondly, a better relationship with the ICS institutions would increase the likelihood of formalization. The ICS is also important for the AWG because the two are institutionally linked. As members of an ICS Working Group, participants accept that their primary task is to make a proposal for formal recognition of the Anthropocene to the ICS. Generally, participants recognize the ICS as the ‘police’ of stratigraphy, which ensures that stratigraphic terms are clearly defined and appropriately used. As a result of this regulative role, ignoring ICS positions would destine the Anthropocene to end up like ‘many examples in the past in stratigraphy where opposing camps get set up and iron gets into the soul, people set up the machine guns in the trenches and that’s it’.

In order to avoid this destiny and enable a constructive relationship, participants emphasize, the AWG has started to incorporate feedback from the stratigraphic community. For example, the preference voiced by the stratigraphic community for a GSSP has led the AWG to move away from a GSSA. Similarly, the AWG has committed to a hierarchical level of the Anthropocene that complies with the preferences of other ICS Working Groups. Specifically, they have confined the Anthropocene to the Epoch level, which allows the Holocene Working Group to continue working relatively independently of any conclusions reached within the AWG. Furthermore, the AWG has sought closer collaboration with the ICS. In particular, the recent AWG membership of Martin Head, the Chair of the SQS, has facilitated direct communication to the extent that a joint meeting is planned, in which the AWG will have the opportunity to present its proposal informally and demonstrate that its approach is in line with established stratigraphic practice.

In the following, I discuss these accounts given by participants with reference to the question what role do interdisciplinarity and disciplinarity play in the AWG? To this end, I will first characterize the interdisciplinary collaboration taking place in the AWG by drawing upon the language provided by different typologies of interdisciplinarity. Secondly, I will discuss the reflections that participants provided on the relationship of the AWG to the stratigraphic community. I will do so by assessing the dual potential of boundary-crossings in the AWG to bring about innovation or fragmentation in stratigraphy.

Discussion

The scope, type, and goals of interdisciplinarity in the AWG

Based on participants’ accounts, interdisciplinarity in the AWG can be characterized by following Huutoniemi et al. (Citation2010) who distinguish between scope, type, and goals as important characteristics of interdisciplinarity. Firstly, it is narrow in scope because mainly natural science knowledge is integrated into the research of the AWG, despite also having social science members in the commission. Secondly, it is multidisciplinary in type since even the integration of natural scientists comprises a bridge building between disciplines rather than a unification of existing bodies of knowledge and a change of disciplinary practices. Finally, the goals that the AWG pursues through this partial interdisciplinary engagement are, on the one hand, to widen accountability of the Group and, on the other hand, to respond to the Anthropocene as a new object that stratigraphy cannot deal with in isolation from other disciplines. In addition, interdisciplinarity is valued as an end in itself.

Regarding the scope, the research of the AWG builds on natural science knowledge while inviting social scientists to provide post-research services such as knowledge dissemination and awareness raising. The interdisciplinary research within the AWG remains ‘narrow’ (Newell Citation1998) in terms of the concepts, methods, paradigms, and epistemologies incorporated in it. Participants in this study and recent publications by members of the AWG (Steffen et al. Citation2016) emphasize that the Earth system sciences are the focus of interdisciplinary collaboration because they complement the scientific approach of stratigraphy. The AWG is not unusual in this respect. Making environmental knowledge from the social and the natural sciences compatible is more demanding than doing so between disciplines that hold similar epistemological and ontological assumptions (Donaldson, Ward, and Bradley Citation2010). In interdisciplinary research projects on Earth system change, social scientists often receive ‘an auxiliary, advisory and essentially non-scientific’ role (Holm et al. Citation2013, p. 1). Although insights of social scientists are central to understanding Earth system change (e.g., Pahl-Wostl et al. Citation2013), the AWG confirms the tendency to involve social scientists as contributors not to the scientific analysis but to the policy dimensions of research projects. Social scientists in the AWG first and foremost assume the task of translating insights of the Group for other, especially public communities and vice versa. They provide a service of translation to the dominant natural science disciplines and, as such, operate in a ‘subordination-service mode’ (Barry, Born, and Weszkalnys Citation2008).

The engagement with other natural sciences diverges from this mode but it remains ‘multidisciplinary’ in type (Potthast Citation2010). An actual transfer between hitherto different practices, theories, and methods, which for example stratigraphy and Earth system science bring to the analysis of the Anthropocene, does not take place. Instead, different types of knowledge are coordinated so they add to one another. Far from operating in an ‘integration-synthesis mode’ (Barry, Born, and Weszkalnys Citation2008, p. 28), in which different forms of natural science knowledge are integrated in a relatively symmetrical fashion and thereby surpass previous ways of thinking, the research practices of stratigraphy and those of other natural sciences in the AWG run parallel to each other. Given the disciplinary setting of the AWG as a working group within the ICS, it is not surprising that the rules and needs of stratigraphy, rather than shared standards of different natural sciences, determine ‘how integration is done’. Research activities of the AWG either are carried out in the disciplinary fashion of stratigraphy from the start, or they are coordinated so that non-stratigraphic research becomes relevant to the main field of stratigraphy. Accordingly, the contribution of other natural science disciplines is to contextualize stratigraphic research, for example, by helping to define an integrated narrative of the Anthropocene upon which chronostratigraphic analysis can be based. This ‘contextualizing interdisciplinarity’ (Boden Citation1999) means that knowledge from other natural science disciplines is applied to provide integrated background information for a stratigraphic research project that remains largely unchanged in theory and methodology.

Correspondingly, the goals that the AWG pursues with this narrow multidisciplinarity can be differentiated according to ‘who is involved’. On the one hand, the foremost benefit that participants ascribe to an AWG membership of different natural science disciplines is a broader understanding of the Anthropocene as a phenomenon. This widening of the stratigraphic perspective is caused by the challenges that the Anthropocene poses for stratigraphic analysis. Participants outline, for example, that the novelty and diachroneity of Anthropocene deposits, as well as the much higher time resolution and continuing development of the Anthropocene strata, diminish the functionality of established stratigraphic methods in this case. Accordingly, the inclusion of natural scientists in the AWG is ‘object-oriented’, seeking to solve methodological problems in response to a new object that cannot be tackled by the existing discipline of stratigraphy alone (Barry, Born, and Weszkalnys Citation2008, p. 29–30). On the other hand, participants argue that the AWG can benefit from a membership that includes social scientists who translate research insights for other stakeholders. Here, the AWG follows the aforementioned ‘logic of accountability’. The rationale is that involving social scientists will enhance the communication of scientific insights and thus increase the accountability of stratigraphy to society.

Beyond these differences in how and why social and other natural scientists are involved in the AWG, interdisciplinarity itself emerges as a goal of the group. Rather than assessing the benefits of boundary-crossings exclusively in terms of its contributions to a formal proposal to the ICS, participants also value them because they stimulate creative debate about the Anthropocene. Participants’ approach to interdisciplinarity can then also be described as ‘practice-oriented’ because they appreciate the social collaboration between experts of diverse domains as an end in itself (Barry, Born, and Weszkalnys Citation2008, p. 30). To be sure, this does not entail a widening of the scope and type of interdisciplinarity, which requires not just appreciation of and trust in the co-workers trained in other disciplines, but also an equality of the different scientific perspectives, methodologies, and practices. This equality is generally rare because it means to reject the idea of a dominant discipline (‘Leitwissenschaft’) that determines methods, aims, and theories (Potthast Citation2010, p. 182). In cases like the AWG ‘where a disciplinary division of labor persists, cross-disciplinary collaboration is [instead,] idealized as a value in itself, and one that outweighs any particular project’ (Barry, Born, and Weszkalnys Citation2008, p. 30).

Disciplinarity of the AWG

Amid this multidisciplinarity of limited scope, the disciplinarity of the AWG is well established. The AWG has conducted itself in relation to the rules and procedures of stratigraphy particularly as it has sought to improve its difficult relationship with the stratigraphic community. The accounts of participants showed that the AWG has done so especially by changing its research practice in accordance with ICS feedback about how to apply the dual hierarchy, about the appropriate hierarchical level for the Anthropocene, and by collaborating more closely. In addition to these details of disciplinarity highlighted by participants, it can be shown that the AWG has adapted the rationale of its work according to ICS recommendations. Not only has the preparation of a formal proposal become more important to its activities but the AWG has also developed a new way of rationalizing its past work that has not directly contributed to such a proposal.3 Participants outline that the nature of the Anthropocene required the creation of a geochronological narrative before the search for an appropriate GSSP and the preparation of a formal proposal could be pursued. The fact that this research rationale was originally proposed by Martin Head, the Chair of the ICS Sub-commission on Quaternary Stratigraphy, demonstrates the influence of the ICS on the AWG.

Paradoxically, participants recognize the regulative role of the ICS on stratigraphic research practice and simultaneously proclaim the need to reform stratigraphic practice. One participant contends that ‘the unique aspects of anthropocene strata are already challenging geologists to modify their assumptions, frameworks and stratigraphic codes’. Participants argue that methodological and theoretical innovations in stratigraphy are necessary because the discipline was originally established to study evidence from the deep past that represents broad changes in strata. The Anthropocene unusually depicts evidence of recent events that have left detailed but minuscule traces in the rock record. In addition, publications authored by AWG members have already suggested concrete innovations in stratigraphic practice. They include interdisciplinary classification schemes for the study of anthropogenic deposits and human artifacts (Ford et al. Citation2014; Zalasiewicz, Kryza, and Williams Citation2014) or a biostratigraphic practice that includes ‘technofossils’ as a distinct type of anthropogenic trace fossil (Waters et al. Citation2014). These suggestions could form the epistemic basis of an internal specialization or even of an evolving inter-discipline of ‘technostratigraphy’ (Zalasiewicz et al. Citation2014). They indicate ‘epistemological strength’ which is one factor in the evolution of a specialized research community (Klein Citation2012, p. 22).

These requests for reform shed a different light on the disciplinarity of the AWG. They suggest that the abovementioned ways in which the AWG has been adapting to disciplinary rules and procedures of stratigraphy are not ideal exchanges between colleagues but ‘pragmatic working arrangements’ (Barry, Born, and Weszkalnys Citation2008, p. 27). For the AWG, these arrangements prevent the stratigraphic community from discarding the Anthropocene as a candidate for official recognition within the geological timescale. They also provide opportunities for the AWG to convince adversaries in the stratigraphic community of the need to integrate different approaches that exist within the discipline. For the ICS, these arrangements serve to ensure cohesion in stratigraphic practice and compliance to the codified rules of stratigraphy. As such, they help to ‘discipline disciples’ (Barry, Born, and Weszkalnys Citation2008, p. 20) and defend the definitional power that characterizes scientific unions like the ICS (Weingart, Carrier, and Krohn Citation2015).4 Juxtaposing these different ambitions of the ICS and the AWG suggests that pragmatic working arrangements within disciplines can translate across internal boundaries as well as work to deny and prolong internal divisions (Barry, Born, and Weszkalnys Citation2008). In both cases, they indicate (temporary) appeasement in a disciplinary controversy. Similarly, the pragmatic working arrangements between ICS and AWG prevent calls for innovation in stratigraphic practice from challenging the disciplinarity of the AWG.

Despite indications of epistemological strength, however, structural reasons obstruct the evolution of the AWG into a self-contained specialized research community. One of the reasons endogenous to the stratigraphic community is that the latter takes a conservative approach and is unlikely to accept innovative methods and theories developed in the AWG. While such resistance from the core of the disciplinary community often results in a disassociation of the pioneers from the parent discipline (Weingart, Carrier, and Krohn Citation2015), additional, exogenous factors obstruct the formation of Anthropocene stratigraphy as a specialization. Both the conservative approach of the stratigraphic community and three exogenous factors are discussed in detail below.

Firstly, specialization depends not just on the epistemological strength of the interdisciplinary practice but also on the ability of a parent discipline to integrate innovative methods and theories (Weingart, Carrier, and Krohn Citation2015). Although participants agree that the stratigraphic community is generally conservative, changes in stratigraphic practice are more acceptable to some of them than to others. Some participants stress that stratigraphy is a flexible discipline that has historically evolved to solve practical problems and accommodate for novel phenomena. They argue the changes necessary to study the Anthropocene are not ‘revolutionary’ compared to changes of the past that are widely accepted today, including the use of fossils for stratigraphic analysis, precise GSSPs for formalization, or indeed the acceptance of the Holocene. But other participants fear that unnecessary changes of the stratigraphic nomenclature and guiding concepts would complicate communication within the discipline and risk politicization of research.

Whether or not participants agree with this conservative perspective, they all believe that it dominates the stratigraphic community. ‘The tribe of stratigraphers…[is generally] cautious, conservative, trying to downplay stuff’ and resistant to changing the GTS. Many stratigraphers tend to embrace established concepts and interpret innovations as attempts ‘to rock the boat’. In regard to the Anthropocene, many stratigraphers find it difficult to accept the idea that geological processes dwarf human influence on the environment, that an epoch should have started within their own lifetime or that anthropogenic deposits should be used as stratigraphic evidence. Participants outline, moreover, that many stratigraphers are particularly concerned with the status of the Holocene, which ‘clues people’ together and may be altered by the Anthropocene. The Anthropocene is ‘very disconcerting and different from what…[many stratigraphers] normally do’. It could be seen as ‘the antithesis of useful with the [geological] community because it’s disrupting the literature, disrupting everything’. This limited ability to redefine ‘what is considered intrinsic and extrinsic to a discipline’ (Klein Citation1996, p. 38) suggests that considerable innovation in stratigraphic practice is unlikely.

Secondly, exogenous factors play a role in the specialization of disciplines (Klein Citation1996, p. 36). In combination with the publicly available information on the AWG, participants’ accounts indicate that social, cultural, and economic capital of the AWG are differently developed. The following shows that although the AWG holds considerable cultural capital, its funding and its social networks continue to lack institutionalization.

Social capital relates to networks of an evolving specialized community and the ways in which it is institutionalized through positions. Although the social capital of the AWG has recently improved, it generally remains weakly developed. One reason for the weak social capital is that the recruitment process of the group, which participants describe as informal and improvised, means that the AWG relies on personal networks for enlisting expertise. Another reason is that these networks are weakly institutionalized. This manifests in the global distribution of AWG members, which has limited communication among the members to an exchange of emails (Nature Citation2015) and joint publications to smaller groups of members that converge around different aspects of the Anthropocene. Having said this, the University of Leicester has recently increased its institutional support of the AWG. Apart from issuing press releases of the AWG (Zalasiewicz and Waters Citation2016), the secretary of the AWG has been appointed honorary chair at the University, which has provided an ‘opportunity to develop a more formal relationship’ between some AWG members. One participant anticipates that this institutionalization of social capital may provide a chance for an increase in economic capital, too.

Economic capital relates to the resources that are available to an evolving specialized community to conduct research or organize exchange among its followers. Like other working groups, the AWG lacks economic capital since it receives no independent funding from the ICS. One effect of this is that the meetings of the AWG have to be co-sponsored and remain rare. During its nine-year tenure, the AWG has only met four times: in October 2014 in Berlin, in November 2015 in Cambridge, in April 2016 in Oslo, and in September 2018 in Mainz. Moreover, participants suggest, greater economic capital would enable a more professional recruitment of a greater diversity of researchers, thus improving social capital. In this sense, the lack of economic capital also affects the research of the AWG. One participant highlights that especially the analysis of sediment cores would require the involvement of more researchers.

Cultural capital encompasses the embeddedness of a research community in popular culture such as in books and the arts but also in the educational system. That the cultural capital of the AWG is relatively well developed is indicated by the fact that almost all participants report to have given public talks, collaborated with artists, or contributed to online fora and media reports. Furthermore, popular science books authored by AWG members (Zalasiewicz and Williams Citation2013), public meetings of AWG members5, and their participation in school events6 suggest a relatively strong embeddedness in popular culture. The AWG assumes public prominence compared to other research groups in the geosciences but its public visibility, overall, remains limited given the transdisciplinary appeal of the Anthropocene.

Conclusion

Amidst a diversifying discourse on the Anthropocene, this article starts from the assumption that research finds wider conceptions of the Anthropocene. This justifies an in-depth investigation of stratigraphic research on the Anthropocene and of the AWG, which drives this work. The analysis presented in this article has focused specifically on the question how interdisciplinarity and disciplinarity affect the AWG. This question is salient because the stratigraphic community, during a period of widespread advocacy for more interdisciplinary research on the Anthropocene, has disagreed about the value of stratigraphic research on the Anthropocene generally and specifically the research conducted by the interdisciplinary group of researchers that comprises the AWG.

To be sure, (inter-)disciplinarity is one of many aspects under which the AWG could be investigated. Other themes that appeared in the data are the contributions of stratigraphy to the Anthropocene discourse and the way in which AWG members engage the public. Moreover, alternative methods of studying the AWG exist such as an ethnographic approach or a different sample of AWG members that involves more social scientists. These alternative methods are likely to generate additional insights but attempts to pursue them were deferred due to considerations about the workload acceptable to AWG members. Generally, this study attends to the internal dynamics of the AWG in conjunction with those of stratigraphy. This focus is strengthened by the method employed, which largely relies on accounts given by a limited sample of AWG members. Internal dynamics are important aspects in the constitution of (inter-)disciplines (Abbott Citation2007) but they are not autonomous from the economic and political context of academia (Shapin Citation1992). A deeper investigation of the exogenous dynamics that influence stratigraphic research on the Anthropocene could therefore usefully complement the study presented in this article. Methodologically, accounts by more AWG members, by representatives of other ICS bodies, by the Earth system science community, or by organizations that have given institutional and economic support to the AWG would be valuable.

The study presented in this article yields two insights about the internal dynamics of the AWG. They are interesting because they diverge from the hypotheses about interdisciplinarity and disciplinarity of the AWG that could be deduced from the published debates. Instead of following a pull of interdisciplinarity, the AWG remains shaped by the established practices of stratigraphy. Moreover, rather than being onerous, the relationship of the AWG with the stratigraphic community has recently been managed pragmatically.

Firstly, the exchange in the AWG between stratigraphy and other disciplines is multidisciplinary and of limited scope. This means that other disciplines represented in the AWG do not infuse the disciplinary research practices of stratigraphers in the AWG. While AWG members associate multiple goals with interdisciplinary boundary-crossings, these goals are advocated separately from a change in stratigraphic research practice. The goals of solving methodological problems (‘object-orientation’), of increasing accountability to society (‘logic of accountability’), and of stimulating creative debate between researchers (‘practice-orientation’) are not reflected in the actual participation of other disciplines in research activities. Although other disciplines are invited to translate and contextualize the work of the AWG, they are not granted an extended involvement in data collection and analysis.

Secondly, although the AWG occasionally crosses the boundaries to other disciplines, its main point of reference remains the stratigraphic community. Accordingly, the disciplinarity of the AWG prevails over potentially innovative research practices that are inspired by interdisciplinary exchanges about novel phenomena and ways to study them. This does not mean that the AWG has wholly renounced suggestions to reform stratigraphic practice in light of the Anthropocene to the disciplinary rules and procedures of stratigraphy. Rather, it has entered into pragmatic working arrangements with the institutionalized quarters of the stratigraphic community, namely the ICS. While this has come at the expense of igniting innovation of stratigraphic practice, it shows that the disciplinarity of the AWG is conditional on social spaces in which it can be negotiated with other members of the stratigraphic community.

The insights provided on the internal functioning of the AWG can be used to complement existing understandings of interdisciplinarity and disciplinarity. Although the AWG is only one example of Anthropocene research, its internal dynamics suggest that disciplines will continue to provide the context for interdisciplinary research (Weszkalnys and Barry Citation2014; Jasanoff Citation2014). The case of the AWG particularly highlights the institutional context (here provided by ICS) of interdisciplinary endeavors (Strathern and Rockhill Citation2014). Even though interdisciplinarity is regarded as beneficial in the AWG, participants accept that any associated innovation in research practices must observe existing disciplinary rules. To be sure, this insight is not generalizable across interdisciplinary fields of study; cybernetics, for example, has managed to avoid most constraints of disciplinary policing (Pickering Citation2014). At the same time, the case of the AWG suggests that even ‘research…which cannot escape the shadow of disciplines,…can move towards ways of working in which the disciplines are not the most important things’ at all stages (Donaldson, Ward, and Bradley Citation2010, p. 1534). Parallel to forms of disciplinary peer review, ideas prominent in interdisciplinary practice like the ‘logic of accountability’ or ‘practice-orientation’ are also evident in the AWG.

Overall, this study shows that both disciplinarity and interdisciplinarity affect the way in which the AWG conducts its research – albeit with different outcomes. The activities of the AWG indicate dynamic engagement between the benefits of crossing disciplinary boundaries and those of orienting academic work toward a specific disciplinary community. This dynamic is not reflected in standard accounts of interdisciplinarity and disciplinarity, which assume that research is either confined to disciplinary quality criteria or open to interdisciplinary insights. The case of the AWG raises questions about this epistemic dichotomy, which future research could answer by providing and comparing more case studies of this type. At the same time, future research could further explore how epistemic openness can be positioned within an existing landscape of disciplines that wish to secure the boundaries of their territories. The AWG makes for an interesting example of opening up to interdisciplinary insights while maintaining legitimacy within a disciplinary research community. More so than other research groups in stratigraphy, the AWG performs on multiple ‘stages’ (Hilgartner Citation2000) some of which lie outside the disciplinary theatre of stratigraphy. As it manages these stages simultaneously, disciplinary and interdisciplinary activities converge into a research practice of narrow multidisciplinarity.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Acknowledgments

This study was initially prepared with Jacob Barber (University of Edinburgh) and George Holmes (University of Leeds) to maximize access to members of the Anthropocene Working Group and to increase the variety and quality of questions posed to them. The result of this collaboration was a pool of data that was subsequently used for separate projects of the different researchers.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 These journals are the Anthropocene Review, Anthropocene, and Elementa – Science of the Anthropocene.

2 In addition, this collaboration resulted in a comment about the role of social scientists in defining a start of the Anthropocene. See Holmes, Barber, and Lundershausen (Citation2017).

3 While early publications of AWG members considered the definition of the Anthropocene linked but not identical to formalization by way of a GSSP (Zalasiewicz et al. (Citation2015); Zalasiewicz et al. (Citation2016), participants in this study regard a formal proposal as their primary task. They thereby follow criticism from the ICS that any geological definition needs to follow the formal procedures set out by the ICS (Finney and Edwards Citation2016b).

4 Although the ICS itself is, to be precise, not a scientific union, it forms one of seven scientific commissions in the International Union of Geological Sciences and thus is integral to the latter.

References

- Abbott, A. D. 2007. Chaos of Disciplines. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Autin, W. J., and J. M. Holbrook. 2012. “Is the Anthropocene an Issue of Stratigraphy or Pop Culture?” GSA Today 7: 60–61. doi: 10.1130/G153GW.1.

- Barry, A., G. Born, and G. Weszkalnys. 2008. “Logics of Interdisciplinarity.” Economy and Society 37 (1): 20–49.

- Beck, S. 2012. “Between Tribalism and Trust: The IPCC under the ‘Public Microscope.’ Nature and Culture 7 (2): 151–173. doi: 10.3167/nc.2012.070203.

- Berkhout, F. 2014. “Anthropocene Futures.” The Anthropocene Review 1 (2): 154–159. doi: 10.1177/2053019614531217.

- Boden, M. A. 1999. What is Interdisciplinarity? In Interdisciplinarity and the Organisation of Knowledge in Europe: A Conference Organised by the Academia Europaea; Cambridge, 24–26 September 1997, edited by Richard Cunningham, 13–24. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities.

- Braje, T. J. 2015. “Earth Systems, Human Agency, and the Anthropocene: Planet Earth in the Human Age.” Journal of Archaeological Research 23 (4): 369–396. doi: 10.1007/s10814-015-9087-y.

- Brasseur, G. P., and B. van der Pluijm. 2013. “Earth's Future: Navigating the Science of the Anthropocene.” Earth's Future 1 (1): 1–2. doi: 10.1002/2013EF000221.

- Brondizio, E. S., O’Brien, K., Bai, X., Biermann, F., Steffen, W., Berkhout, F., Cudennec, C., Leomos, M. C., Wolfe, A., Palma-Oliveira, J., Chen, C.-T. 2016. “Re-Conceptualizing the Anthropocene: A Call for Collaboration.” Global Environmental Change 39: 318–327. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2016.02.006.

- Castree, N. 2017. “Global Change Research and the ‘People Disciplines’: Toward a New Dispensation.” South Atlantic Quarterly 116 (1): 55–67. doi: 10.1215/00382876-3749315.

- Clark, N. 2017. “Politics of Strata.” Theory, Culture and Society 34 (2–3): 211–231. doi: 10.1177/0263276416667538.

- Clark, T. 2015. Ecocriticism on the Edge: The Anthropocene as a Threshold Concept. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Clifford, N. J., S. French, and G. Valentine. 2010. “Getting Started in Geographical Research: How this Book Can Help”. In Key Methods in Geography, 2nd ed, edited by N. J. Clifford, S. French and G. Valentine, 3–15. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Conrad, F. G., and M. F. Schober. 2010. “New Frontiers in Standardized Survey Interviewing.” In Handbook of Emergent Methods, edited by S. Nagy Hesse-Biber and P. Leavy, 173–189. New York: Guilford Press.

- Constanza, R. 2013. “Beyond the argument culture.” In Beyond Reductionism: A Passion for Interdisciplinarity, edited by K. Farell, T. Luzzati, S. van den Hove, xvi–xix. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Cook, B. R., and A. Balayannis. 2015. “Co-producing (a Fearful) Anthropocene.” Geographical Research 53 (3): 270–279. doi: 10.1111/1745-5871.12126.

- Cornell, S. E., C. J. Downy, E. D. G. Fraser, and E. Boyd. 2012. “Earth System Science and Society: A Focus on the Anthropocene.” In Understanding the Earth System: Global Change Science for Application, edited by S. E. Cornell, I. C. Prentice, J. I. House, and C. J. Downy, 1–10. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Crutzen, P. J., and E. Stoermer. 2000. “The Anthropocene.” IGBP Newsletter 41 (17): 17–18.

- Delanty, G., and A. Mota. 2017. “Governing the Anthropocene.” European Journal of Social Theory 20 (1): 9–38. doi: 10.1177/1368431016668535.

- Donaldson, A., N. Ward, and S. Bradley. 2010. “Mess Among Disciplines: Interdisciplinarity in Environmental Research.” Environment and Planning A 42 (7): 1521–1536. doi: 10.1068/a42483.

- Ellis, E., M. Maslin, N. Boivin, and A. Bauer. 2016. “Involve Social Scientists in Defining the Anthropocene.” Nature 540 (7632): 192–193. doi: 10.1038/540192a.

- Faircloth, C. A. 2012. “After the interview: What is left at the End.” In The Sage Handbook of Interview Research: The Complexity of the Craft, 2nd ed, edited by J. F. Gubrium, 269–277. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Finney, S. C., and L. E. Edwards. 2016a. “Reply to Zalasiewicz et al. Comment.” GSA Today 27 (2): e38. doi: 10.1130/GSATG326Y.1.

- Finney, S. C., and L. E. Edwards. 2016b. “The “Anthropocene” Epoch: Scientific Decision or Political Statement?” GSA Today 26 (3): 4–10. doi: 10.1130/GSATG270A.1.

- Ford, J. R., S. J. Price, A. H. Cooper, and C. N. Waters. 2014. “An Assessment of Lithostratigraphy for Anthropogenic Deposits.” In A Stratigraphical Basis for the Anthropocene, edited by C. N. Waters, J. Zalasiewicz, M. Williams, M. A. Ellis and A. M. Snelling, 55–89. London: The Geological Society of London.

- Gibbons, M., C. Limoges, H. Nowotny, S. Schwartzman, P. Scott, and M. Trow. 1994. The New Production of Knowledge: The Dynamics of Science and Research in Contemporary Societies. London: Sage.

- Gibson, H., and S. Venkateswar. 2015. “Anthropological Engagement with the Anthropocene: A Critical Review.” Environment and Society: Advances in Research 6 (1): 5–27. doi: 10.3167/ares.2015.060102.

- Gieryn, T. F. 1999. Cultural Boundaries of Science: Credibility on the Line. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Gradstein, F. M., J. G. Ogg, M. Schmitz, and G. Ogg. 2012. The Geologic Time Scale. Burlington: Elsevier Science.

- Hilgartner, S. 2000. Science on Stage: Expert Advice as Public Drama. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Holm, P., Goodsite, M. E. S. Cloetingh, M. Agnoletti, B. Moldan, D. J. Lang, R. Leemans, J. O., Moeller, M. P., Buendia, W., Pohl, R., Scholz, A., Sors, B., Vanheusden, K., and Yusoff, Zondervan, R. 2013. “Collaboration between the Natural, Social and Human Sciences in Global Change Research.” Environmental Science and Policy 28: 25–35. doi: 10.1016/j.envsci.2012.11.010.

- Holmes, G., J. Barber, and J. Lundershausen. 2017. “Anthropocene: Be Wary of Social Impact.” Nature 540: 464.

- Huutoniemi, K., J. T. Klein, H. Bruun, and J. Hukkinen. 2010. “Analyzing Interdisciplinarity: Typology and Indicators.” Research Policy 39 (1): 79–88. doi: 10.1016/j.respol.2009.09.011.

- International Geological Union 2002. Statutes of the International Commission on Stratigraphy. http://www.stratigraphy.org/index.php/ics-statutesofics.

- Jahn, T., D. Hummel, and E. Schramm. 2015. “Nachhaltige Wissenschaft im Anthropozän (Sustainability Science in the Anthropocene).” GAIA 2: 92–95.

- Jasanoff, S. 2012. Science and Public Reason. London: Routledge.

- Jasanoff, S. 2014. “Fields and Fallows: A Political History of STS.” In Interdisciplinarity: Reconfigurations of the Social and Natural Sciences, edited by A. Barry and G. Born, 99–118. London: Routledge.

- Johnson, E., H. Morehouse, S. Dalby, J. Lehman, S. Nelson, R. Rowan, S. Wakefield, and K. Yusoff. 2014. “After the Anthropocene.” Progress in Human Geography 38 (3): 439–456. doi: 10.1177/0309132513517065.

- Kidwell, S. M. 2015. “Biology in the Anthropocene: Challenges and Insights from Young Fossil Records: Fig. 1.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 112 (16): 4922–4929. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1403660112.

- Klein, J. T. 1996. Crossing Boundaries: Knowledge, Disciplinarities, and Interdisciplinarities. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia.

- Klein, J. T. 2012. “A Taxonomy of Interdisciplinarity.” In The Oxford Handbook of Interdisciplinarity, edited by R. Frodeman, J. Thompson Klein and C. Mitcham, 15–30. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Kotchen, M. J., and O. R. Young. 2007. “Meeting the Challenges of the Anthropocene: Towards a Science of Coupled Human–Biophysical Systems.” Global Environmental Change 17 (2): 149–151. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2007.01.001.

- Krohn, W. 2012. “Interdisciplinary Cases and Disciplinary Knowledge.” In The Oxford Handbook of Interdisciplinarity, edited by R. Frodeman, J. T. Klein and C. Mitcham. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Larsson, J., and I. Holmström. 2007. “Phenomenographic or Phenomenological Analysis: Does It Matter? Examples from a Study on Anaesthesiologists’ Work.” International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being 2 (1): 55–64. doi: 10.1080/17482620601068105.

- Lorimer, J. 2017. “The Anthropo-Scene: A Guide for the Perplexed.” Social Studies of Science 47 (1): 117–142. doi: 10.1177/0306312716671039.

- Lövbrand, E., J. Stripple, and B. Wiman. 2009. “Earth System Governmentality.” Global Environmental Change 19 (1): 7–13. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2008.10.002.

- Lundershausen, J. 2018. “Marking the Boundaries of Stratigraphy: Is Stratigraphy Able and Willing to Define, Describe and Explain the Anthropocene?.” Geo: Geography and Environment 5 (1): e00055. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/geo2.55.

- Malm, A., and A. Hornborg. 2014. “The Geology of Mankind? A Critique of the Anthropocene Narrative.” The Anthropocene Review 1 (1): 62–69. doi: 10.1177/2053019613516291.

- Maslin, M. A., and S. L. Lewis. 2015. “Anthropocene: Earth System, Geological, Philosophical and Political Paradigm Shifts.” The Anthropocene Review 2 (2): 108–116. doi: 10.1177/2053019615588791.

- Mikecz, R. 2012. “Interviewing Elites: Addressing Methodological Issues.” Qualitative Inquiry 18 (6): 482–493. doi: 10.1177/1077800412442818.

- Monastersky, R. 2015. “Anthropocene: The Human Age.” Nature 519 (7542): 144–147.

- Nature. 2011. “The Human Epoch: Official Recognition for the Anthropocene Would Focus Minds on Challenges to Come.” Nature 473: 254.

- Nature. 2015. “All in Good Time: Stratigraphers Have yet to Decide Whether the Anthropocene Is a New Unit of Geological Time.” Nature 519: 129–130.

- Newell, W. H. 1998. “Professionalizing Interdisciplinarity: Literature Review and Research Agenda.” In Interdisciplinarity: Essays from the Literature, edited by W. H. Newell, 529–563. New York: College Board.

- Nida-Rümelin, J. 2005. “Wissenschaftethik (Ethics of Science).” In Angewandte ethik: Die bereichsethiken und ihre theoretische fundierung: ein handbuch (Applied Ethics: Ethics and Their Theoretical Foundation: A Manual, 2nd ed, edited by Julian Nida-Rümelin, 836–858. Stuttgart: Kröner.

- Ogg, J. 2004. “Status of Divisions of the International Geologic Time Scale.” Lethaia 37 (2): 183–199. doi: 10.1080/00241160410006492.

- Osborn, T. 2014. “Inter that Discipline!” In Interdisciplinarity: Reconfigurations of the Social and Natural Sciences, edited by A. Barry and G. Born, 82–98. London: Routledge.

- Pahl-Wostl, C., C. Giupponi, K. Richards, C. Binder, A. de Sherbinin, D. Sprinz, T. Toonen, and C. van Bers. 2013. “Transition towards a New Global Change Science: Requirements for Methodologies, Methods, Data and Knowledge.” Environmental Science and Policy 28: 36–47. doi: 10.1016/j.envsci.2012.11.009.

- Palsson, G., Szerszynski, B. S. Sörlin, J. Marks, B. Avril, C. Crumley, H. Hackmann, P., Holm, P., Ingram, J., Kirman, A., Buendia, P., and Weehuizen, R. 2013. “Reconceptualizing the ‘Anthropos’ in the Anthropocene: Integrating the Social Sciences and Humanities in Global Environmental Change Research.” Environmental Science and Policy 28: 1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.envsci.2012.11.004.

- Pickering, A. 2014. “Ontology and Antidisciplinarity.” In Interdisciplinarity: Reconfigurations of the Social and Natural Sciences, edited by A. Barry and G. Born, 209–225. London: Routledge.

- Potthast, T. 2010. “Epistemisch-moralische Hybride und das Problem interdisziplinärer Urteilsbildung.” In Interdisziplinarität: Theorie, Praxis, Probleme, edited by M. Jungert, E. Romfeld, T. Sukopp and U. Voigt, 174–191. Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft.

- Rickards, L. A. 2015. “Metaphor and the Anthropocene: Presenting Humans as a Geological Force.” Geographical Research 53 (3): 280–287. doi: 10.1111/1745-5871.12128.

- Schaffner, S. 2014. “How Disciplines Look.” In Interdisciplinarity: Reconfigurations of the Social and Natural Sciences, edited by A. Barry and G. Born, 57–81. London: Routledge.

- Schreier, M. 2012. Qualitative Content Analysis in Practice. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Shapin, S. 1992. “Discipline and Bounding: The History and Sociology of Science as Seen through the Externalism-Internalism Debate.” History of Science 30 (4): 333–369.

- Silverman, D. 2011. Interpreting Qualitative Data: A Guide to the Principles of Qualitative Research, 4th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Steffen, W., W. Broadgate, L. Deutsch, O. Gaffney, and C. Ludwig. 2015. “The Trajectory of the Anthropocene: The Great Acceleration.” The Anthropocene Review 2 (1): 81–98. doi: 10.1177/2053019614564785.

- Steffen, W., Leinfelder, R. J. Zalasiewicz, C. N. Waters, M. Williams, C. Summerhayes, A. D. Barnosky, A., et al. 2016. “Stratigraphic and Earth System Approaches to Defining the Anthropocene.” Earth's Future 4 (8): 324–345. doi: 10.1002/2016EF000379.

- Stehr, N., and P. Weingart. 2000. “Introduction.” In Practising Interdisciplinarity, edited by N. Stehr and P. Weingart, xi–xvi. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- Strathern, M., and E. K. Rockhill. 2014. “Unexpected Consequences and Unanticipated Outcome.” In Interdisciplinarity: Reconfigurations of the Social and Natural Sciences, edited by A. Barry and G. Born, 199–140. London: Routledge.

- Swanson, H. A. 2016. “Anthropocene as Political Geology: Current Debates Over How to Tell Time.” Science as Culture 25 (1): 157–163. doi: 10.1080/09505431.2015.1074465.

- Swanson, H. A., N. Bubandt, and A. Tsing. 2015. “Less than One but More than Many: Anthropocene as Science Fiction and Scholarship-in-the-Making.” Environment and Society: Advances in Research 6 (1): 149–166. doi: 10.3167/ares.2015.060109.

- Szerszynski, B. 2012. “The End of the End of Nature: The Anthropocene and the Fate of the Human.” Oxford Literary Review 34 (2): 165–184. doi: 10.3366/olr.2012.0040.

- Warde, P., L. Robin, and S. Sörlin. 2017. “Stratigraphy of the Rennaissance: Questions of Expertise for ‘the Environment’ and ‘the Anthropocene.’” The Anthropocene Review 4 (3): 246–258. doi: 10.1177/2053019617738803.

- Waters, C. N., J. A. Zalasiewicz, M. Williams, M. A. Ellis, and A. M. Snelling. 2014. “A Stratigraphical Basis for the Anthropocene?” In A Stratigraphical Basis for the Anthropocene, edited by C. N. Waters, J. Zalasiewicz, M. Williams, M. A. Ellis and A. M. Snelling, 1–21. London: The Geological Society of London.

- Weingart, P., M. Carrier, and W. Krohn. 2015. Nachrichten aus der Wissensgesellschaft: Analysen zur Veränderung von Wissenschaft., 2nd ed. Weilerswist: Velbrück Wissenschaft.

- Weszkalnys, G., and A. Barry. 2014. “Multiple Environments: Accountability, Integration and Ontology.” In Interdisciplinarity: Reconfigurations of the Social and Natural Sciences, edited by A. Barry and G. Born, 178–208. London: Routledge.

- Wissenburg, M. 2016. “The Anthropocene and the Body Ecologic.” In Environmental Politics and Governance in the Anthropocene: Institutions and Legitimacy in a Complex World, edited by P. Pattberg and Z. Fariborz, 15–30. London: Routledge.

- Yusoff, K. 2013. “Geologic Life: Prehistory, Climate, Futures in the Anthropocene.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 31 (5): 779–795. doi: 10.1068/d11512.

- Zalasiewicz, J., R. Kryza, and M. Williams. 2014. “The Mineral Signature of the Anthropocene in its Deep-time Context.” In A Stratigraphical Basis for the Anthropocene, edited by C. N. Waters, J. Zalasiewicz, M. Williams, M. A. Ellis and A. M. Snelling, 109–117. London: The Geological Society of London.

- Zalasiewicz, J., and C. Waters. 2016. Media Note: Anthropocene Working Group (AWG). Leicester: University of Leicester.

- Zalasiewicz, J., C. Waters, and M. J. Head. 2017. “Anthropocene: Its Stratigraphic Basis.” Nature 541 (7637): 289. doi: 10.1038/541289b.

- Zalasiewicz, J., Waters, C. N., Ivar do Sul, C. N. J., Corcoran, J. A. P. L., Barnosky, A. D., Cearreta, M., and Edgeworth, A., et al. 2016. “The Geological Cycle of Plastics and Their Use as a Stratigraphic Indicator of the Anthropocene.” Anthropocene 13: 4–17. doi: 10.1016/j.ancene.2016.01.002.

- Zalasiewicz, J., Waters, C. N., Summerhayes, C. N. C. P., Wolfe, A. P., Barnosky, A. D., Cearreta, P., Crutzen, E., et al. 2017. “The Working Group on the Anthropocene: Summary of Evidence and Interim Recommendations.” Anthropocene 19: 55–60. doi: 10.1016/j.ancene.2017.09.001.

- Zalasiewicz, J., Waters, C. N., Williams, C. N. M., Barnosky, A. D., Cearreta, A., Crutzen, P., and Ellis, M. A., et al. 2015. “When Did the Anthropocene Begin? A Mid-Twentieth Century Boundary Level is Stratigraphically Optimal.” Quaternary International 383: 196–203. doi: 10.1016/j.quaint.2014.11.045.

- Zalasiewicz, J. A., and M. Williams. 2013. The Goldilocks Planet: The Four Billion Year Story of Earth's Climate. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Zalasiewicz, J., M. Williams, W. Steffen, and P. J. Crutzen. 2010. “The New World of the Anthropocene.” Environmental Science and Technology 44 (7): 2228–2231. doi: 10.1021/es903118j.

- Zalasiewicz, J., M. Williams, C. N. Waters, A. D. Barnosky, and P. Haff. 2014. “The Technofossil Record of Humans.” The Anthropocene Review 1 (1): 34–43. doi: 10.1177/2053019613514953.