Abstract

A deprioritization of economic growth in policy making in the rich countries will need to be part of a global effort to re-embed economy and society into planetary boundaries. However, societal support for a degrowth transition remains for the time being moderate, and it is not well understood as yet why this is the case. This article argues that Pierre Bourdieu’s sociology can help theorize societal stability and transformational change as well as the preconditions for a degrowth transition. The point of departure is the structure/action debate in sociology highlighting Bourdieu’s middle-ground position. Using his theory of practice, it moves on to analyze the predominating correspondence between structure, habitus, and action as well as the preconditions under which this correspondence may break and result in transformational change. Subsequently, his distinction of “doxa,” “orthodoxy,” and “heterodoxy” is applied to understand possible solutions to the multidimensional crisis of contemporary European societies. The last section addresses Bourdieu’s take on the role that researchers and activists may play during such a transition. The article concludes that in order to facilitate degrowth, formulations of eco-social policy strategies should avoid overburdening people’s experiences and immediate expectations of the future. Deliberative citizen forums can help co-develop and upscale such initiatives as well as broaden their social basis.

Introduction

Several decades of capitalist growth coincided with significant and rising levels of welfare and well-being in Western societies. However, given planetary limits, this level of material welfare was at no point in time generalizable to the rest of the world. Attempts to decouple gross domestic product (GDP) growth from resource use and greenhouse gas emissions in absolute terms have largely failed (Fritz and Koch Citation2016; Hickel and Kallis Citation2019). The price for the Western “way of life” was the approaching or crossing of thresholds for biophysical processes such as climate, biodiversity, or the nitrogen cycle (Steffen et al. Citation2018). Meeting global targets such as those of the 2015 Paris Agreement will therefore need to include a deprioritization of economic growth in policy making in the rich countries as a precondition for re-embedding their economies and societies into planetary boundaries. This is especially emphasized in the quickly growing “degrowth” literature (Weiss and Cattaneo Citation2017; Parrique Citation2019). The overall degrowth vision requires societies in the rich countries to follow trajectories leading to socioeconomic systems that are much smaller in terms of their material and energy throughput. Degrowthers argue that this economic and ecological downscaling process can proceed in democratic and socially equitable ways while allowing for the maintenance of critical levels of well-being (Research and Degrowth Citation2010). It is the emphasis on the democratic character of the planned transition and the simultaneous rejection of any eco-authoritarian “solution” to the crisis that makes “degrowth” a prime example for the kinds of “democratic sustainability transformations” with which this Special Issue is concerned.

However, despite the fact that the degrowth community has been growing in terms of the number of conferences, publications and initiatives,Footnote1 the degrowth idea remains marginalized within wider public debates. This marginalization has only started to be reflected in degrowth circles. Buch-Hansen (Citation2018), for example, makes use of critical political economy to explain the lack of support for degrowth. He identifies four preconditions for transformational change toward degrowth. Of these, however, only the first two are currently, to some extent, met: a far-reaching crisis of the existing system, an alternative political project, a comprehensive coalition of social forces waging political struggles to make the project hegemonic, and at least passive consent in the population. Koch (Citation2018) revisits the analysis of economic categories, social relations, and modes of consciousness in Marx’s Capital and Bourdieu’s sociology of consumption in Distinction. This analysis suggests that the growth orientation appears to be the normal and quasi-natural way to run and steer “the” economy - a reversal of historically and socially specific relations into features of nature and things that make resistance unlikely and complicate social transformation. Welzer (Citation2011) and Göpel (Citation2016) refer to social and psychological mechanisms that likewise contribute to the growth paradigm’s deep embeddedness in people’s minds and bodies. Büchs and Koch (Citation2019) argue that the discussion of stability and change of existing as well as the character of radically transformed economic, social, and cultural institutions required for an encompassing and relatively quick ecological and social transformation in the existing degrowth literature is not sufficiently anchored in social science expertise.

To strengthen the social science basis within explanatory approaches toward understanding democratic sustainability transformations such as degrowth, this article discusses Pierre Bourdieu’s sociology. Its theoretical capacity to theorize and explain societal stability and transformational change has hitherto been underutilized in the degrowth literature, ecological economics, and sustainability science. The point of departure is the structure/action debate in sociology. Using Bourdieu’s theory of practice, it moves on to analyze the predominating correspondence between structure, habitus, and action, as well as the preconditions under which this correspondence may break and result in transformational social change. His distinction of “doxa,” “orthodoxy,” and “heterodoxy” is subsequently applied to understand possible solutions to the multidimensional crisis of contemporary European societies. The last section addresses Bourdieu’s take on the role that intellectuals, researchers, and activists may play in such a transition. The conclusion summarizes the argument and delineates future research paths.

Social structures and individual action

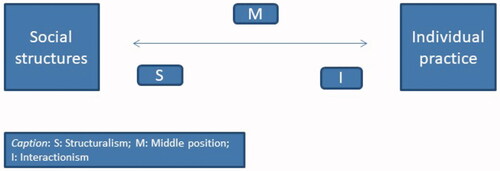

When debating the relationship between social structures and individual action different sociologists have emphasized either “objective” structure over “subjective” action or vice versa. And they have positioned themselves at different points in a corresponding structure-action continuum (). At one extreme of this continuum are positions, which, almost as if observing the Earth from the moon, examine the whole of society and its institutions as interrelated systems. Corresponding studies highlight, for example, the functions that particular institutions such as the labor market or the education system have for the reproduction of the overall social system. Subsequently, one would make his or her way down to end up at individuals and small-scale interactions. Social theories, which otherwise differ in many ways, that share this “top-down” approach, include Louis Althusser’s Marxist and Lévy-Strauss’s anthropological structuralisms,Footnote2 Émile Durkheim and Talcott Parsons’ functionalisms and Niklas Luhmann’s system theory (‘S’ in ). At the opposite end of the spectrum are interactionist approaches that work their way up from the analysis of individual intentions and small-scale relationships to institutions and entire societies. For this “bottom-up” approach stand sociologists as different as Erving Goffman, George Herbert Mead, and Herbert Blumer as well as Sartre’s existential philosophy (‘I’ in ). Max Weber became famous for his “methodological individualism,” even if he did not apply this perspective consequently in his empirical and historical work.Footnote3

Finally, there are theories, which occupy a middle position (‘M’ in ) in the social structures/individual action continuum. Corresponding theorists include Marx, Giddens (Citation1984), who offers a range of examples of what he calls the structure/agency problem in sociology, Bourdieu and, in their footsteps, more recent “social practices” approaches (Shove, Pantzar, and Watson Citation2012; Røpke Citation2009; Joutsenvirta Citation2016; Büchs and Koch Citation2017). These authors agree with the other mentioned sociologists that social structures are the result of individual action, yet insist on the fact that most of these structures are actually best understood as unintended consequences of individual practices. Karl Marx (Citation1990), in his Critique of Political Economy, always focused on economic categories, social relations, and modes of consciousness at the same time. People purchase a range of things every day in coffee shops, supermarkets, and so forth. However, while individuals acquire particular use values to satisfy their needs and wants, they unconsciously reproduce the social use of commodities and money as powerful social structures within capitalist societies. Many people also go to work, be it to make ends meet and/or because they genuinely like what they do, mostly in the form of employment at some private or public company. The unintended consequence of offering their labor power as a commodity, however, is the reproduction of the basic class structure of capitalist society (understood in terms of a transfer of surplus labor from one class to another). Hence, even though nobody intends to reproduce the class structure by going to work, this is exactly what occurs every day. Pierre Bourdieu, for his part, focuses on consumption relations. Through cultural practices such as hobbies or by expressing preferences for particular kinds of music, dance, film, or theater, the social actors unknowingly reproduce a social hierarchy of lifestyles that, in turn, plays a major part in maintaining the class structure; a social process to which Bourdieu (Citation1984) referred to as “distinction.”

According to Bourdieu (Citation1990a, 62), adequate theorizing of society and social change must include what he calls the “paradoxes of objective meaning without subjective intention.” With his theory of practice (understood as repeated, regular, and routinized forms of individual action), Bourdieu amplifies his middle-ground position in the structure/action continuum as he simultaneously distances himself from structuralist (or “objectivist”) and interactionist (or “subjectivist”) positions. To overcome this division, he postulates “to step down from the sovereign viewpoint from which objectivist idealism orders the world, as Marx demands in the Theses on Feuerbach, but without having to abandon to it the “active aspect” of apprehension of the world” (Bourdieu Citation1990a, 52). To mediate between structure and practice, Bourdieu introduces the “habitus” as a system of structured and, at the same time, structuring dispositions in terms of thoughts, perceptions, expressions, and actions. He claims that the conditioned and conditional freedom it provides is equally “remote from creation of unpredictable novelty as it is from simple mechanical reproduction of the original conditioning” (Bourdieu Citation1990a, 55). Hence, with the habitus Bourdieu attempts to systematically consider both the “social conditionings,” which produce a preparedness to act in particular ways or to “play the game,” and the “subjective practice orientations,” which may stretch as far as giving up the game. While Bourdieu characterizes the habitus in terms of a “transforming machine,” which “leads us to “reproduce” the social conditions of our own production,” he emphasizes at the same time that it does so in a “relatively unpredictable way,” so that “one cannot move simply and mechanically from knowledge of the conditions of production to knowledge of the products” (Bourdieu Citation1993, 87).

Stability and change in the theory of practice

Bourdieu’s intermediation of the structure-action relationship via the habitus may be read as an update of Marx’s dictum in the Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte: “Men make their own history, but they do not make it as they please; they do not make it under self-selected circumstances, but under circumstances existing already, given and transmitted from the past” (Marx Citation1978, 11). Far from suggesting a “social structure that can never change” (Burawoy Citation2012, 190), Bourdieu builds on Marx and presents people as acting and being capable of making a difference but always within certain social limits set by the historical period in which they live. Accordingly, the habitus, “a product of history, produces individual and collective practice – more history – in accordance with the schemes generated by history” (Bourdieu Citation1990a, 54). Referring back to Durkheim (Citation1977, 11), who already stressed that in “each of us, in differing degrees, is contained the person we were yesterday,” Bourdieu highlights the “active presence” of past experiences in the actors’ schemes of perception, thought, and action, which tend to “guarantee the ‘correctness’ of practices and their constancy over time, more reliably than all formal rules and explicit norms” (Bourdieu Citation1990a, 54).

While the leeway to act and initiate social change is generally limited by the socio-historical conditions of the formation of the habitus, it also varies with position in social space and its class-, race-, and gender-specific divisions: people with greater volumes of capital in its various sorts have greater impacts than others. The dispositions of the habitus are acquired during socialization in the family and education system. During this process, its different layers become “crystallized,” whereby some of them “may waste away or weaken through lack of use” (Bourdieu Citation2000, 161). Within this integration and layering process of earlier and more recent experiences, the former have “particular weight” because the habitus tends to “ensure its own constancy and its defense against change through the selection it makes,” for example, by “rejecting information capable of calling into question its accumulated information” (Bourdieu Citation1990a, 60–61).Footnote4 As a corollary, the dispositions that form a person’s habitus are durable, yet can become disjointed, especially during periods of transitions of their social environment. This can lead to “all sorts of effects of hysteresis (of time-lag, of which the example par excellence is Don Quixote)” (Bourdieu Citation1993, 87), and contribute to real and perceived exclusion as well as a deterioration of people’s well-being as they feel “out of place” with the changed social environment. Largely unaware of the historical, economic, and social background of their exclusion, which may make itself felt through sanctions such as criticism, distrust, and other practices of dissociation, people tend to blame themselves for it, and this may plunge them even “deeper into failure” (Bourdieu Citation2000, 161). At the same time, this feeling of not belonging and desperation, previously theorized in terms of “anomie” by Durkheim (Citation2013) and Merton (Citation1938), complicates the actors’ capabilities of making use of the opportunities that a new social situation may have to offer.

If people act and make changes within the historical limits of their own upbringing, this constitutes an objective limitation to their capabilities and possibilities of creating societal alternatives including the degrowth transition. In fact, Bourdieu points out that his approach is “very far” from Cornelius Castoriadis’ “language of the ‘imaginary,’” the use of which Bourdieu characterizes as “somewhat recklessly” (Bourdieu Citation2000, 171). The presence of the past comes, paradoxically, to the surface, when the “sense of the probable future is belied” and when “dispositions ill-adjusted to the actors’ objective chances” are “negatively sanctioned because the environment they actually encounter is too different from the one to which they are objectively adjusted” (Bourdieu Citation1990a, 62). In relation to the feasibility of degrowth, it may be followed that suggesting alternative policies with a view of making them hegemonic must be sufficiently linked to people’s expectations of the future, which are themselves a corollary of their past experiences. Only then can strategies of political mobilization count on the habitus’ capability of reacting to changing and unforeseen social situations through “constant adjustments” that may result in “durable transformations” (Bourdieu Citation1993, 87). Though the capacity of people to act and initiate social change is more or less limited due to different positions in social space and corresponding dispositions, the habitus always involves an element of spontaneity. It is thus not so much the simple reproduction by carriers of social relationships as highlighted in structuralism and functionalism that the construct of habitus attempts to address but precisely the site of fracture between structure and practice.

Hegemony, crisis, and transformational change

Just as the reversal into natural and eternal features of historically-specific economic categories and social relations of the capitalist production and reproduction process generates general and immediate consent (Marx Citation1990; Citation2006; Koch Citation2018), the habitus produces “harmony between practical sense and objectified meaning” or a “common-sense world” (Bourdieu Citation1990a: 58), which is constantly reinforced in day-to-day practices such as expressions, commonplaces, or sayings. We can understand the cultural hegemony of the growth imperative in analogy with Bourdieu’s analysis of the role of symbolic power in the maintenance of the social order. In fact, it comes close to that of the Catholic doxa of the Middle Ages, serving as a kind of pensée unique, since it appears to provide quasi-natural solutions for all kinds of social and ecological issues. And like all manifestations of power, the social genesis of which is forgotten, invisible, and appears to be natural, the growth imperative includes a certain readiness for collaboration, or a degree of practical consent, on the part of those who are at the receiving end, an “acceptance of domination” (Bourdieu Citation1984, 386).Footnote5 Yet far from being a “voluntary servitude,” a “conscious, deliberate act,” such a submission goes further than what the Marxian tradition discussed in terms of “consciousness” and “ideology.” It is in fact a “tacit and practical belief made possible by the habituation which arises from the training of the body” (Bourdieu Citation2000, 171–172). The incorporation of objective structures in dispositions of the habitus is of a pre-reflexive kind, which helps to explain the somewhat astonishing “ease with which, throughout history and apart from a few crisis situations, the dominant impose their domination” (Bourdieu Citation2000, 178).

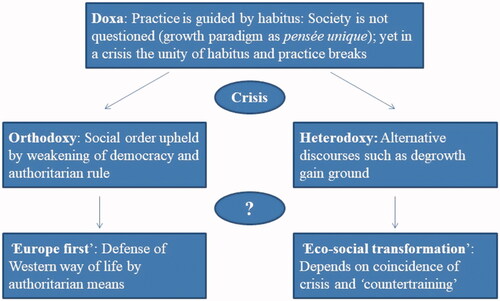

According to Bourdieu, the chance that the customary correspondence between structure, habitus, and practice breaks and that alternative ways of thinking and acting become hegemonic depends upon the existence of a crisis. In this event, the economic, political, cultural, and symbolic structures of society undergo a process of transition leading to a “collapse, weakening, or obsolescence of traditions or of symbolic systems” that provided the principles of people’s “worldview and way of life” (Bourdieu Citation1991, 34). Crises can first take the form of a crisis within the ancien régime: the institutional structure of the old social order turns out to be flexible enough for the actors to enter new kinds of alliances (on welfare and social inclusion, for example), that is, without questioning its fundamental principles. Hence, the social order, including its corresponding values, habitus forms, and so forth is maintained based on some gradual or incremental change (Mahoney and Thelen Citation2010); second, crises can take the form of a crisis of the existing social order. Its institutional structure turns out to no longer be capable of giving a realistic future perspective to satisfying the needs, wishes, and desires of a majority of citizens. We may conclude with Bourdieu that in this event, the traditional correspondence of habitus, practice, and structure breaks, making the economic, social and symbolic institutions of society crumble. At once, the social specificity of relations, which is normally taken for the natural order of things and goes largely unquestioned, becomes transparent, and the simple formula of societal reproduction according to “doxa” – structure-habitus-practice-structure – ceases to apply. To the extent that what is normally unconscious becomes conscious, the habitus stops generating social practice and is gradually replaced by other organization principles such as rational calculus and conscious action. Bourdieu (Citation1977; Citation1990a; Citation2000) refers to this possibility as “heterodoxy” or “heresy.”

However, while alternative discourses and heterodox social forces gain ground during a crisis of the social order so do those that opt for its authoritarian defense, which may include the marginalization or abolition of democratic institutions and civil rights (). Bourdieu calls this alternative exit strategy of crisis “orthodoxy.” In contrast to heterodoxy, which tends to “open up the future,” orthodoxy refers to periods of restoration, in a sense to “stop time, or history, by closing down the range of possibles so as to try to induce the belief that ‘the chips are down’ for ever” (Bourdieu Citation2000, 235).Footnote6

Much evidence indicates that we are in the midst of a multidimensional crisis which is unlikely to be resolved under the institutional arrangements of the current growth strategy of finance-driven capitalism (Koch Citation2012; Buch-Hansen Citation2018; Overbeek and Apeldoorn Citation2012). According to the late Max-Neef (Citation2014, 17), “never before in human history [have] … so many crises converged simultaneously to reach their maximum level of tension.” There are at least four dimensions of this crisis. First, while the negative economic and social consequences of the 2008 financial crisis are not yet overcome, a new financial crisis is already looming (IMF Citation2016, 1). Political economists such as Gordon (Citation2012) take the associated massive levels of public and private debt as a strong “headwind” for the promotion of future material prosperity. In fact, even scholars and policy makers outside the degrowth camp would be well advised to consider the possibility that economic growth rates are likely to be small for the foreseeable future and plan accordingly. Second, massive and growing inequality has resulted in a social crisis that leaves growing shares of the population in the rich countries unable to satisfy their basic needs (OECD Citation2015), while the wealth of the richest household groups continues to surge. Third, the environmental crisis described in the introduction above undermines current and future living conditions for human beings and other species and threatens to end human civilization as we know it (IPBES Citation2019). Finally, there is a crisis of political representation (Crouch Citation2004), culminating in events such as Brexit and the election of Donald Trump. More generally, this crisis dimension is expressed through the weakening in support and power resources of once-strong political parties such as Social and Christian Democrats in several European countries as well as the simultaneous inroads that rightwing populist parties have made in a range of democracies in the global North.

This multidimensional crisis suggests that the Western European postwar class compromise, including its promise of permanent and increasing material prosperity based on the provision of economic growth (Lutz Citation1989), has come to an end. Yet whether this crisis of the economic and social order will eventually result in an overcoming of the capitalist growth economy via an ecological and social transformation and degrowth is far from certain. This is because the crumbling of doxa has, historically, only rarely led to its replacement by heterodox thought and practice. More often than not, the crisis of an established order has resulted in a new kind of orthodoxy where dominant interests are defended by replacing democratic rule by authoritarian rule and the use of force. New types of rightwing populist movements combine a conservative critique of finance-driven capitalism with chauvinistic and xenophobic slogans, and provide the popular basis for an authoritarian “solution” to the crisis that we may call “Europe first”Footnote7 one in which the rich countries’ “way of life” is defended virtually to the last minute. This is achieved by using military power, closing borders, and leaving the victims of climate change to their fate. Whether the current crisis will result in “Europe first” or an “ecological social transformation” will not least depend on the availability of “hands-on” eco-social policy strategies. In other words, it will be necessary to forge ideas for both single policies and their synergy in the short and long-term, to which critical researchers and activists can contribute, and involving both “bottom-up” civil society mobilization and “top- down” policies of an active state (Hirvilammi Citation2020; Koch Citation2020).

The role of intellectuals, researchers, and activists: “countertraining” and deliberative forums

There is little doubt that Bourdieu assessed the social structures of the society he experienced toward the end of his life as being in crisis (he passed away in 2002). In fact, he went as far as excluding the possibility of a “return to those social universes in which the quasi-perfect coincidence between objective tendencies and subjective expectations made the experience of the world a continuous interlocking of confirmed expectations” (Bourdieu Citation2000, 234). He observed, instead, that the “lack of a future, previously reserved for the ‘wretched of the earth,’ is an increasingly widespread, even modal experience” within Western societies. But he also reminds us of the relative autonomy of the symbolic order, which especially in periods of crisis, when expectations and chances become unlinked can “leave a margin of freedom for political action aimed at reopening the space of possibles” (Bourdieu Citation2000, 234). In this situation, symbolic power of all kinds is able to “manipulate hopes and expectations,” especially through a “more or less inspired and uplifting performative evocation of the future” (Bourdieu Citation2000, 234). It becomes, then, possible to introduce a “degree of play” into the otherwise predominating correspondence between expectations and chances and to open up a “space of freedom,” which is expressed in the “more or less voluntarist” positing of utopias, projects, and policies, “which the pure logic of probabilities would lead one to regard as practically excluded” (Bourdieu Citation2000, 234).

Yet even during crises, activists must “reckon with dispositions,” and with the “limitations these impose on innovative imagination and action” (Bourdieu Citation2000, 234). Appeals to heterodox practice can therefore succeed only to the extent that these manage to “reactivate dispositions which previous processes of inculcation have deposited in people’s bodies” (Bourdieu Citation2000, 235). We may follow from this that political demands of whatever kind have the best chance of gaining critical amounts of support if they tie in with layers within people’s habitus that have become blocked in the course of socialization and daily life. Younger children, especially, tend to have a relatively “uncolonized imaginary” and a significant capability to play freely, which is subsequently reduced when taking on societal roles such as workers, husbands and wives, parents, and so forth. But if subversive discourses and actions manage to build on and appeal to these submerged dispositions, they can produce the belief that “this or that future,” either desired or feared, is possible, “mobilize a group around it and so help to favor or prevent the coming of that future” (Bourdieu Citation2000, 235). Discourses or actions of subversion such as “provocations” and “all forms of iconoclasm” can then help to “transgress the limits imposed,” and, by symbolically overcoming otherwise iron social frontiers, take on a “liberatory effect in its own right” as they enact “the unthinkable” (Bourdieu Citation2000, 236).

When the social and economic structures of society are in crisis, there is a certain chance that an intellectual or academic critique of the social order will enjoy critical societal feedback. Even though Bourdieu clarifies that the symbolic work needed to “liberate the potential capacity for refusal” involves more than holding up a mirror to doxa through critical intellectual practice, he still sees an important role for intellectuals to play in bringing about change.Footnote8 Based on a rational critique of the dominant discourse, which may arise from heterodox centers within the academic field from where it is transferred through the media toward the field of power intellectuals can take the role of “professional practitioners” or “spokespersons of the dominated,” since there are “partial solidarities and de facto alliances springing from the homology between a dominated position in this or that field of cultural production and the position of the dominated in the social space” (Bourdieu Citation2000, 188). Such solidarity or “transfer of cultural capital,” however, is not without the risk of “hijacking” as the “correspondence between the interests of the dominated and those of the dominated-dominant” (the intellectuals) always remains “imperfect.” While Bourdieu regards intellectuals, as holders of cultural capital, as part of the “dominant class,” that is, they are in a superior class position vis-à-vis the middle and lower classes, he nevertheless places them in a “dominated” position vis-à-vis the dominant fraction of the dominant class: the holders of economic capital. Hence, intellectuals (“dominated-dominant”), middle and lower classes occupy different positions in the social structure and, as a consequence, personify “different experiences of domination” (Bourdieu Citation2000, 188). Though his insistence on this difference in social position (and, as a corollary, in interests) constitutes a critique, qualification and further development of the Gramscian notion of “organic intellectuals,” Bourdieu’s concept of intellectuals and his corresponding attempt to unify “the scientific and the ethical or political vocation” (Bourdieu Citation1990a: 2) nevertheless formulates a similar ambition.

Finally, Bourdieu (Citation2000, 172) gives a more concrete hint how critical researchers and activists could facilitate a durable transformation of people’s habitus. Beyond “making things explicit,” only a “thoroughgoing process of countertraining, involving repeated exercises…like an athlete’s training” can help bring those suppressed and forgotten layers of the habitus to the fore that are required to overcome the neoliberal doxa and the growth imperative. The first and foremost precondition for this to happen is the creation and expansion of spaces where the growth imperative ceases to occupy (or “colonize”) people’s bodies and minds. The international degrowth conferences, as well as associated local events and larger-scale initiatives such as transition towns, are only a few examples of spaces of resistance, where other forms of social interaction than those guided by competition, status, and growth are already tried and tested. An additional attempt of collaboration between researchers and other citizens, which could provide the kind of “countertraining” that Bourdieu has in mind, are applications of what Gough (Citation2017) calls, in relation to need satisfaction, the “dual strategy” of policy formation. This undertaking combines the codified knowledge of researchers with the experiential knowledge of citizens and local stakeholders to identify the goods and services necessary for needs satisfaction within a particular social and cultural context and environmental limits. While such deliberative forums are by definition locally and temporally specific, their outcomes have in different societal contexts helped to critically review policy goals, behaviors, satisfiers, and infrastructures, and led to adaptations in long-term policy planning, which were, in some cases, upscaled to the national level. Guillén-Royo (Citation2015) provides examples for this from Spain, Peru, and Norway. Given the extremely short time period the IPCC (Citation2018) identifies as remaining to keep global warming within 1.5 °C such practices of democratic deliberation for need satisfaction within environmental limits would need to be initiated as soon as possible.

To awaken the capacities of individuals to free play and alternative thinking beyond the growth imperative and to promote opportunities for mutual learning between the different actors involved, these forums would need to be organized in an atmosphere as welcoming, open, and participatory as possible, and may need to be repeated several times. This implies mixed-methods approaches beyond mere panel-style “exchanges of arguments” including workshops, story- and role telling, as well as performative methods including filming and theater playing (Heras and Tàbara Citation2014). The suggestion to introduce such forums to (co-)develop more sustainable ways of needs satisfaction echoes calls for citizen assemblies in reaction to the climate emergency by, for example, Extinction Rebellion. However, rather than holding direct regulatory power as Extinction Rebellion demands, such forums could have advisory character and, in principle, be organized by local or national government representatives, civil society organizations, and researchers. Similarly, recent political science expertise indicates that a meaningful and adequate response to the ecological crisis would require the complementation of the contemporary institutions of representative democracy through more direct and deliberate democracy elements (Hammond and Smith Citation2017).

There are both minimum and maximum satisfaction levels for human needs which could be addressed in such forums (Koch, Buch-Hansen, and Fritz Citation2017). While minimum levels can be established, for example, via the so-called “reference budgets,” which have been developed for some European countries to define the minimum resources required for full participation in society (Goedemé et al. Citation2015; Davis et al. Citation2018), similar terms of reference could, in principle, also be developed for maximum levels of needs satisfaction.Footnote9 Social and ecological limits for maximum consumption could be defined, contextualized for local levels, and translated into monetary amounts for individuals or households (Buch-Hansen and Koch Citation2019). Researchers could contribute to such citizen forums with, for example, information on the size of ecological footprints that are within sustainable levels, while the whole forum could deliberate on what kind of lifestyles and production patterns this may allow.

Conclusion

Contemporary Western societies are caught up in multiple crises. In relation to the ecological crisis dimension, there is no indication that the traditional growth path can be “greened” sufficiently as to re-embed Western production and consumption norms into planetary limits. Yet despite the fact that there are, in principle, not many rational arguments against deprioritizing economic growth in policy making, the degrowth movement continues to lack the critical support which would be necessary to initiate a social, ecological, and democratic transformation from the bottom up. In this article, I have focused on Bourdieu’s sociology with respect to theorizing societal stability and change and applied it to a social science concept of some of the challenges and preconditions for a degrowth transition.

From this point of view, it is unlikely that transformational social change such as a degrowth transition is going to occur under “normal,” that is crisis-free, societal circumstances. This is because the habitus tends to accommodate “objective” social positions with “subjective” aspirations and expectations in relation to the future. Both the entire social order and one’s own position in it are mostly taken for granted, perceived as natural, and reproduced as non-intended results of subjective intentions in a myriad of day-to-day social practices. However, though the habitus represents to a huge extent the presence of the past, it does not resemble an iron cage that would altogether deny change to happen. In the course of a crisis, especially, the correspondence of structures, habitus, and action breaks, and the habitus is complemented or replaced by other structuring principles of practice. Yet it is far from certain that doxa is substituted by heterodox solutions to the current crisis such as an ecological and social transformation. The alternative is always orthodox exit strategies, currently indicated by the strengthening of rightwing populism across Europe (“Europe first”) and beyond.

Given that individual expectations and future hopes are linked to the historical and social conditions of one’s upbringing, it follows for the degrowth transition that demands for radical societal change should consider people’s lived experience as much as possible. Though there is a margin of freedom that can be appealed to and gradually widened through strategies of symbolic mobilization, there is always the danger of overloading people in their capacity to engage in free play, resistance, and formulation of and living societal alternatives. Rather abstract appeals to people who tend to be caught up in a range of daily struggles to make ends meet to quickly start thinking and feeling in fundamentally different ways are likely to be perceived as foolhardy or “not for us.” Yet if demands are formulated and presented in ways that are sufficiently close to peoples’ past experiences and present day-to-day issues and struggles, there is a better chance of being understood and receiving positive feedback. A good example for this is the volume Housing for Degrowth (Nelson and Schneider Citation2018), which outlines alternatives to conceiving housing as a commodity and monetary investment, thereby directly addressing the satisfaction of a basic human need that is currently in jeopardy.

Bourdieu’s sociology suggests that researchers and activists can play a crucial part in developing alternative and sustainable future scenarios to which others can draw (Svenfelt et al. Citation2019). If aware of the rather narrow limits that the habitus tends to set the “imaginaries” of the dominated and of the differences of the social position of intellectuals and activists vis-à-vis the dominated they can become facilitators (or “spokespersons”) for the dominated to push the boundaries of what is perceived as “possible.” Measures of continuous “countertraining” can waken and activate those layers and dispositions of the habitus that are furthest from the reproduction of the growth imperative’s colonization of bodies and minds. While degrowth conferences, camps, courses, and so forth are a very good start in this regard, it is also necessary to further develop an eco-social policy strategy capable of initiating the required ecological and social transformation in the long-term without overburdening people’s experiences and immediate expectations of the future in the short-term. For the identification of alternative “imaginaries” in the form of concrete future degrowth scenarios that are close enough to citizens’ experiences and hopes it is crucial to include and engage with them as early as possible in the process of scenario building. Much points to the temporary conclusion that deliberative citizen forums should play a greater role in future research into the structural preconditions for a degrowth transition.

Acknowledgments

I thank the editors and three anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments on earlier drafts.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Some of these initiatives found a remarkable societal response: The open letter “Europe, It’s Time to End the Growth Dependency" was published in 16 countries and signed by about 90,000 Europeans. It is available online at https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2018/sep/16/the-eu-needs-a-stability-and-wellbeing-pact-not-more-growth.

2 Both authors reduced the significance of human agency to that of “carriers” of social structures. Althusser used the German word Träger to emphasize his position.

3 His writings on the role of the Protestant Ethic (Weber Citation1958) during the emergence of capitalism can hardly be regarded as based on individual intentions and motivations. To analyze these factors, Weber would have had to use original sources from rank-and-file Calvinists such as letters, newspapers, and so forth. Instead, he took the preaching and theological writings from historical figures such as Richard Baxter as “real-type” examples of Calvinism.

4 This observation resonates with recent psychological and economic reasoning according to which the human mind primarily deals with phenomena it has already observed. People do normally not take into account the entire complexity of the social world so that their understanding of it consists of a small and unrepresentative set of observations (Kahneman Citation2011).

5 Following the meritocratic idea, economic growth is perceived as the ideal environment for individual upward mobility, including by the poorest social strata who may, “objectively” speaking, be regarded as not benefiting from the dominant economic model.

6 Bourdieu does not develop a genuine crisis “theory” of the kind of Marx’s Critique of Political Economy. As a corollary, he does not discuss why and how capitalist development proceeds in periodical minor and major crises. Neither does he refer to the most recent crises of the Fordist and finance-driven periods of capitalist development in theoretical terms. It therefore seems promising to go beyond his original work and link it to heterodox political economy. Boyer (Citation2008) and Koch (Citation2012, Citation2018, Citation2019) have demonstrated that the Regulation approach (Boyer and Saillard Citation2002) is in many ways compatible with Bourdieusian sociology. Bourdieu himself might have embraced such a (re-)unification given his critique of the status quo of an “artificially divided social science” (Bourdieu Citation2005, 210).

7 Alternatively, this can take an anti-EU and nationalist form and may hence be called “Sweden,” “Germany,” or “France first.”

8 Bourdieu refuses to provide a substantial or definite definition of who and what kind of practice actually counts as “intellectual.” Instead, he assumes the historical development of a relatively autonomous “intellectual field” with its own specific laws and principles of capital distribution, especially that of a symbolic kind. Though the “currency” of this capital is somewhat difficult to measure, Bourdieu (Citation1990b) makes it clear that it cannot be expressed in commercial terms in the first place. More important is the recognition indicated through publications, citations, awards, appointments to academies, and so forth. An “intellectual” is then an actor who is included and operates in the intellectual field.

9 Research into “sustainable consumption corridors” has a similar ambition (Di Giulio and Fuchs Citation2014).

References

- Bourdieu, P. 1977. Outline of a Theory of Practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Bourdieu, P. 1984. Distinction: A Social Critique of Judgement and Taste. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Bourdieu, P. 1984. Homo Academicus. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Bourdieu, P. 1990a. The Logic of Practice. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Bourdieu, P. 1990b. “The Intellectual Field: A World Apart.” In In Other Words. Essays towards a Reflexive Sociology, edited by P. Bourdieu, 140–149. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Bourdieu, P. 1991. “Genesis and Structure of the Religious Field.” Comparative Social Research 13: 1–44.

- Bourdieu, P. 1993. Sociology in Question. London: Sage.

- Bourdieu, P. 2000. Pascalian Meditations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Bourdieu, P. 2005. The Social Structures of the Economy. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Boyer, R. 2008. “Pierre Bourdieu, a Theoretician of Change? the View from Regulation Theory.” In The Institutions of the Market: Organizations, Social Systems, and Governance, edited by A. Ebner and N. Beck, 348–398. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Boyer, R., and Y. Saillard, eds. 2002. Regulation Theory: The State of the Art. London: Routledge.

- Buch-Hansen, H. 2018. “The Prerequisites for a Degrowth Paradigm Shift: Insights from Critical Political Economy.” Ecological Economics 146: 157–163. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2017.10.021.

- Buch-Hansen, H., and M. Koch. 2019. “Degrowth through Income and Wealth Caps?” Ecological Economics 160: 264–271. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2019.03.001.

- Büchs, M., and M. Koch. 2017. Postgrowth and Wellbeing: Challenges to Sustainable Welfare. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Büchs, M., and M. Koch. 2019. “Challenges to the Degrowth Transition: The Debate about Wellbeing.” Futures 105: 155–165. doi:10.1016/j.futures.2018.09.002.

- Burawoy, M. 2012. “The Roots of Domination: Beyond Bourdieu and Gramsci.” Sociology 46 (2): 187–206. doi:10.1177/0038038511422725.

- Crouch, C. 2004. Post-Democracy. Cambridge: Polity.

- Davis, A., D. Hirsch, M. Padley, and C. Shepherd. 2018. A Minimum Income Standard for the UK, 2008–2018: Continuity and Change. London: Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

- Di Giulio, A., and D. Fuchs. 2014. “Sustainable Consumption Corridors: Concept, Objections, and Responses.” GAIA 23 (3): 184–192. doi:10.14512/gaia.23.S1.6.

- Durkheim, E. 1977. The Evolution of Educational Thought. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

- Durkheim, E. 2013. The Division of Labour in Society. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Fritz, M., and M. Koch. 2016. “Economic Development and Prosperity Patterns around the World: Structural Challenges for a Global Steady-State Economy.” Global Environmental Change 38: 41–48. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2016.02.007.

- Giddens, A. 1984. The Constitution of Society: Outline of the Theory of Stucturation. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Goedemé, T., B. Storms, S. Stockman, T. Penne, and K. van den Bosch. 2015. “Towards Cross-Country Comparable Reference Budgets in Europe: First Results of a Concerted Effort.” European Journal of Social Security 17 (1): 3–31. doi:10.1177/138826271501700101.

- Göpel, M. 2016. The Great Mindshift: How a New Economic Paradigm and Sustainability Transformations Go Hand in Hand. London: Springer Open.

- Gordon, R. 2012. “Is US Economic Growth Over? Faltering Innovation Confronts the Six Headwinds.” Working Paper 18315. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Gough, I. 2017. Heat, Greed and Human Need: Climate Change, Capitalism and Sustainable Wellbeing. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Guillén-Royo, M. 2015. Sustainability and Wellbeing: Human-Scale Development in Practice. London: Routledge.

- Hammond, M., and G. Smith. 2017. “Sustainable Prosperity and Democracy: A Research Agenda.” CUSP Working Paper No. 8. Guildford: University of Surrey. https://www.cusp.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/WP08-Sustainable-Prosperity-and-Democracy.pdf.

- Heras, M., and D. Tàbara. 2014. “Let’s Play Transformations! Performative Methods for Sustainability.” Sustainability Science 9 (3): 379–398. doi:10.1007/s11625-014-0245-9.

- Hickel, J., and G. Kallis. 2019. “Is Green Growth Possible?” New Political Economy: 1–18. doi:10.1080/13563467.2019.1598964.

- Hirvilammi, T. 2020. “The Virtuous Circle of Sustainable Welfare as a Transformative Policy Idea.” Sustainability 12 (1): 391. doi:10.3390/su12010391.

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). 2018. Global Warming of 1.5 °C: Summary for Policymakers. Geneva: IPCC.

- Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES). 2019. “Summary for Policymakers of the Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services.” Bonn: IPBES. https://www.ipbes.net/news/ipbes-global-assessment-summary-policymakers-pdf.

- International Monetary Fund (IMF). 2016. Fiscal Monitor. Washington, DC: IMF.

- Joutsenvirta, M. 2016. “A Practice Approach to the Institutionalization of Economic Growth.” Ecological Economics 128: 23–32. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2016.04.006.

- Kahneman, D. 2011. Thinking Fast and Slow. New York, NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

- Koch, M. 2012. Capitalism and Climate Change: Theoretical Discussion, Historical Development and Policy Responses. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Koch, M. 2018. “The Naturalisation of Growth: Marx, the Regulation Approach and Bourdieu.” Environmental Values 27(1): 9–27. doi:10.3197/096327118X15144698637504.

- Koch, M. 2019. “Elements of a Political Economy of the Postgrowth Era.” Real-World Economics Review 87: 90–105.

- Koch, M. 2020. “The State in the Transformation to a Sustainable Postgrowth Economy.” Environmental Politics 29 (1): 115–133. doi:10.1080/09644016.2019.1684738.

- Koch, M., H. Buch-Hansen, and M. Fritz. 2017. “Shifting Priorities in Degrowth Research: An Argument for the Centrality of Human Needs.” Ecological Economics 138: 74–81.

- Lutz, B. 1989. Der Kurze Traum Immerwährender Prosperität [The Short Dream of Everlasting Prosperity]. Frankfurt/Main: Campus.

- Mahoney, J., and K. Thelen. 2010. Explaining Institutional Change: Ambiguity, Agency and Power. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Marx, K. 1978. The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte. Beijing: Foreign Languages Press.

- Marx, K. 1990. Capital: A Critique of Political Economy, Vol. 1. London: Penguin Classics.

- Marx, K. 2006. Capital: A Critique of Political Economy, Vol. 3. London: Penguin Classics.

- Max-Neef, M. 2014. “The World on a Collision Course and the Need for a New Economy.” In Co-Operatives in a Post-Growth Era, edited by S. Novkovic and T. Webb, 83–100. London: Zed Books.

- Merton, R. 1938. “Social Structure and Anomie.” American Sociological Review 3 (5): 672–682. doi:10.2307/2084686.

- Nelson, A. and F. Schneider, eds. 2018. Housing for Degrowth: Principles, Models, Challenges and Opportunities. London: Routledge.

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). 2015. In It Together: Why Less Inequality Benefits All. Paris: OECD.

- Overbeek, H. and B. Apeldoorn, eds. 2012. Neoliberalism in Crisis. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Research and Degrowth. 2010. “Degrowth Declaration of the Paris 2008 Conference.” Journal of Cleaner Production 18: 523–524.

- Røpke, I. 2009. “Theories of Practice: New Inspiration for Ecological Economic Studies on Consumption.” Ecological Economics 68 (10): 2490–2497. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2009.05.015.

- Shove, W., M. Pantzar, and M. Watson. 2012. The Dynamics of Social Practice. Everyday Live and How It Changes. London: Sage.

- Steffen, W., J. Rockström, K. Richardson, T. M. Lenton, C. Folke, D. Liverman, C. P. Summerhayes, et al. 2018. “Trajectories of the Earth System in the Anthropocene.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 115 (33): 8252–8259. doi:10.1073/pnas.1810141115.

- Svenfelt, Å, E. C. Alfredsson, K. Bradley, E. Fauré, G. Finnveden, P. Fuehrer, U. Gunnarsson-Östling, et al. 2019. “Scenarios for Sustainable Futures beyond GDP Growth 2050.” Futures 111: 1–14.

- Parrique, T. 2019. “The Political Economy of Degrowth.” PhD Thesis in Economics and Finance at University Clermont Auvergne and Stockholm University. Available online at https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-02499463/document

- Weber, M. 1958. The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism. London: Routledge.

- Welzer, H. 2011. Mentale Infrastrukturen: Wie Das Wachstum in Die Welt Und in Die Seelen Kam [Mental Infrastuctures: How Growth Came into the World and into Souls]. Berlin: Heinrich-Böll Stiftung.

- Weiss, M. and C. Cattaneo. 2017. “Degrowth – Taking Stock and Reviewing an Emerging Academic Paradigm.” Ecological Economics 137: 220–230.