Abstract

This article explores the picture of sustainable mobility drawn by the world’s biggest toy company, Lego, and how this picture is potentially received and consolidated by Lego players. The company has already attracted the attention of scholars and activists alike regarding their influence on attitudes toward gender and race. The question of their influence on sustainable development, however, has not yet been tackled, amidst the overdue socio-cultural transformation of sectors such as mobility. We combine research on discursive business power from the field of international political economy with insights into the rituals of play from social psychology as well as science and technology studies. The heuristic device of the re-signification process of discursive power aligns these perspectives and generates sub-questions for the empirical investigation. As outlined in our methodology section, we deliver a qualitative-hermeneutic analysis of Lego building sets and commercials. In the results section we show, that playing with Lego products encourages children to re-signify the norms of unsustainable mobility, especially the dominance of the car. In the discussion and conclusion of our contribution we argue that the normalization of car-centered built environments and associated lifestyles, as well as omnipresent fossil-fuel dependency, hinder Lego’s potential to deliver transformative stimuli that promote a more sustainable mobility sector.

Introduction

“Everything is NOT Awesome,” is the title of a Greenpeace video that went viral on YouTube in 2014 and ultimately led to the dissolution of the controversial cooperation between the companies Lego A/S and Royal Dutch Shell (see Greenpeace Citation2014). The campaign questioned Lego’s promise that their main product, building bricks, makes it possible to create “everything” and, thus, Lego “awesomely” supports the education of “the builders of tomorrow” (Robertson Citation2013, 17; Lego Citation2016a). Greenpeace suggests that Lego narrows the “idea of tomorrow” when they brand their toy products with the logos of other companies like Shell. The latter, according to Greenpeace, is “polluting our kids’ imagination” (Greenpeace Citation2014). The Greenpeace activists assert that when Lego incorporates the Shell insignia onto its products, Lego is ignoring, or even normalizing, Shell’s role in climate degradation (for instance through their drilling activities in the Arctic as was mentioned in the 2014 video). In other words, by associating with Shell, Lego also becomes a symbol for unsustainable mobility habits such as the reliance on fossil fuels. “Branding” products in this way is a standard marketing practice in the toy and entertainment industry (Mumby Citation2016). What makes specifically the Lego instance worth looking at as a single case study is the company’s range. Lego is the world’s largest toy producer and a company that has succeeded in developing a notable level of corporate socio-cultural status.

One of the crucial challenges of the Anthropocene is sustainably transforming the mobility sector. It is generally acknowledged that the habits and structures of mobility are highly relevant when considering sustainable lifestyles and imaginaries of sustainable futures (Manderscheid Citation2018; Hajer and Versteeg Citation2019; Graf and Sonnberger Citation2020). Furthermore, needs related to the mobility sector have shown a high degree of inelasticity and immutability (Cohen Citation2010; Mullen and Marsden Citation2016; Sheller Citation2018). Why is that? Our aim is not to suggest that this toy company, Lego, completely controls our attitudes toward mobility. However, we think it is essential to uncover the discursive power that manifests at the junction of business and everyday practices (like playing) in what is otherwise, usually, a technology-centered debate on mobility (Cohen Citation2012; Graf and Sonnberger Citation2020). In this regard, Greenpeace’s objections to the Lego-Shell partnership raise interesting research questions: What conceptions of mobility does Lego communicate? How do toy companies potentially influence children’s perceptions and ideas about (un)sustainable mobility? What implications for sustainable developments in mobility can we draw from the interplay between the company’s performance and children’s perceptions?

John Urry (Citation2007) has shown that we cannot think about mobility without also considering daily and (socio-)cultural interactions. In line with this view, recent approaches to “mobility culture” have highlighted the multidimensional complexity of mobility practices (for example, Deffner and Hefter Citation2012). Playing has been addressed as an everyday practice in this regard by the cultural sciences, educational sciences, and social psychology. These disciplines discuss how education and play interact and thereby influence the reproduction of norms and values (for instance, Hayward Citation2012; Kasser Citation2016; Lauwaert Citation2009). Meanwhile, research in science and technology studies (STS) has also shown that the specific material or object being played with is by no means irrelevant either (Latour Citation1991; Barad Citation2003).

To adequately assess the Lego company as a business actor, we choose a power-sensitive approach and draw on the concepts of playing and materiality as derived from social psychology and STS. Research into business power, in particular, highlights the impact of socio-cultural routines and everyday practices on global political dynamics (Hobson and Seabrooke Citation2007; Newell Citation2013; Chatterjee and Finger Citation2014). While social scientists have already raised the question of how toy companies enact discursive power (Johnson Citation2014; Black et al. Citation2016), they have not investigated this issue in relation to sustainability or sustainable practices. Hence, the connection with sustainability norms in an analytical framework is overdue, although thinking about playing and discursive power is not a novel development. With the heuristic of the re-signification process, Antonia Graf (Citation2016) has proposed a methodological tool to analyze the productive dimension of such discursive powers. She identifies three stages of the re-signification process – adaption, reception, and consolidation of norms and discourses – that connect the actor-specific demonstration of power with societal norms. Adopting this framework, we aim to show that in the act of playing with Lego, children are enacting and re-signifying established norms of (un)sustainable mobility. In this way, we argue, discursive power is not confined to the business actors’ corporate communications through, for example, reports and self-descriptions. We propose that the discursive power also unfolds through “everyday practices,” such as playing, that occur when consumers interact with the company’s products. We illustrate this argument through a qualitative-hermeneutic content analysis of Lego advertisements, corporate documentation, and depictions of building sets.

In the next section, we lay out our framework for examining the power of business actors in the field of sustainability and outline the relevance of Lego as a powerful actor within the global political economy. In particular, we describe our understanding of discursive power and its relation to children’s play and education. Afterwards, we briefly elaborate on the methodological application of this framework. We then empirically analyze the different stages of the re-signification process and discuss our results concerning the discourse on (un)sustainable mobility. Finally, we conclude by describing the overall relevance of this study for engaging with socio-cultural dynamics of mobility transitions. Herewith, we are reflecting on the specific role of companies as well as the limitations of this contribution.

Playing with Lego as a quest for power: a heuristic device

Lego – a powerful actor in global governance?

Political science, and international political economy (IPE) specifically, has a long tradition of discussing which actors are “powerful” in global governance and the reasons why this is the case. As a result, a wide range of ideas about how to differentiate between forms and mechanisms of power has emerged, based on manifold social theoretical backgrounds (for overviews see, for instance, Berenskoetter and Williams Citation2007; Guzzini Citation2005). IPE scholars have been and continue to be interested in uncovering which actors (other than states) obtain power in global governance (van Apeldoorn et al. Citation2011). In particular, critical IPE as a heterogeneous field (for a comprehensive overview see Shields et al. Citation2011) is open to new perspectives acknowledging, for instance, the matter of the “cultural” (Best and Paterson 2010) or the “everyday” (Hobson and Seabrooke Citation2007).Footnote1 Consequently, several studies have addressed and conceptualized power for different actor-specific contexts.

In 2007, Doris Fuchs presented a theoretical framework of power to better account for and distinguish the dynamics of business power wielded by economic actors such as transnational companies (TNCs). Within this framework, she differentiates between instrumental, structural, and discursive power. Instrumental power is the direct influence of one actor on another and refers to the meaning of operational resources, such as monetary capital and investments. Structural power is connected to the material structures that underpin behavioral options and thereby determines who has indirect and direct decision-making power. Discursive power of business actors shapes both policies and the policy-making process by altering norms and attitudes of the actors (Fuchs Citation2007; also see Fuchs et al. Citation2016; Fuchs and Lederer Citation2007).

Fuchs’ framework complements the work of Lukes (Citation1974, Citation2005), Nye (Citation2004) and others, underlining the influence of ideational power resources. Using this approach, Graf’s (Citation2016) elaboration on the discursive power dimension shows how business actors contribute to the shaping and temporary stabilizing of the discourse. Highlighting the interplay of material and non-material power resources, Graf has argued that it is not the division of power dimensions but their enabling capacities for each other that are key to better grasping “business power.” Discursive power is supposed to be comprehensively received and consolidated by actors interacting with the company, including investors, competitors, and employees, but also by consumers (Hobson and Seabrooke Citation2007; Stanley Citation2014). These perspectives on power prove to be helpful to gain a wider perspective in the light of the constructivist question of “what does power do” (Guzzini Citation2005). They move beyond the question if actors are powerful, and also ask how and with which effects their power unfolds in daily routines.

Lego’s instrumental power stems largely from its position as the world’s biggest toy producer (Statista Citation2017).Footnote2 Lego has a long and successful corporate history, centered around a core product, the iconic brick. After severe losses in the 1990s, several new (digital) platforms and building sets have allowed users to be not only consumers but also “co-producers” (Lauwaert Citation2008, 231). This identification with the product marked an important step toward the company’s success as a socio-cultural phenomenon (Carrington and Dowall Citation2013). Lego’s business structure, being entirely family-owned and having comparatively little involvement in external investment schemes (Lego Citation2019b), makes the company somewhat more resilient to the economic “power of the market” in the first place.Footnote3 Nonetheless, its operational business relies on other industrial sectors. In particular, the main component of the Lego brick is still petroleum, meaning that the company is dependent on a global industry that is both highly economically vulnerable and ecologically contested.Footnote4

Lego has actively sought to cooperate with other companies and, thereby, has also built up significant structural power. Cooperative projects have included the Legoland theme parks as well as movies and video games. Furthermore, by licensing and “branding” (Mumby Citation2016) building sets to entertainment and industrial companies (including Shell, Warner Brothers, and Disney) Lego has been able to showcase the unique character of the Lego brick to a huge audience while sticking close to its original concept of performative play (Robertson Citation2013; Johnson Citation2014). As noted above, the company maintains corporate structures that protect the positive image of the company regarding business responsibility and consumers’ trust in the quality and value of the product. Additionally, Lego’s structural power is attained by its ability to communicate these values successfully. The company willingly assumes the responsibility to serve “the builders of tomorrow” (Lego Citation2016a), to help them develop ideas, and to learn how to shape future society and spaces.

Discursive power addresses opaque spaces where norms and discourses influence actors. Rather than just in economic or political arenas, discursive power emerges in response to stimuli, communications that are, willingly or unwillingly, sent out by companies. In her contribution of 2016, Graf theorized the examination of discursive power with the help of the re-signification process, which links the communication via norms of power with its reception. Obviously, in the case of Lego, playing with building bricks is central to the intermediation of societal norms with individual reception.

Everyday learning – discursive power in children’s play

As Stanley (Citation2014, 898) emphasizes, the role of “everyday” IPE is to “highlight how non-elite actors can drive change in the global political economy” (also see van Apeldoorn et al. Citation2011). In turn, they themselves might be influenced in their individual practice by the same norms and values that were stimulated by other IPE actors such as TNCs (also see Hardy and Thomas Citation2015; Orlikowski and Scott Citation2015). When approaching the act of playing with Lego bricks from this viewpoint, we can comprehend how it is a process through which toy companies send out stimuli. In the following, we consider Lego toys, as well as the descriptions and commercial visualizations of them, as stimuli. These are all received by audiences and have the potential to lead to a consolidation of certain norms that have been adapted and reiterated through the stimuli.

Many scholars accept the notion that the act of playing influences how children perceive the world and accordingly learn how they should behave in it. While “playing” remains a broad and ambiguous concept (Sutton-Smith Citation1997), it has been described as “informal education” (Greenfield Citation2009; Halverson and Sheridan Citation2014), which is different from the publicly monitored education in schools or kindergartens. Playing, in this sense, is understood as a ritualized practice of learning that is twofold. On one hand, it facilitates learning practical skills, and on the other hand, it refers to learning social values and customs (see Ozanne and Ozanne Citation2011; Mertala et al. Citation2016). Hence, playing is nowadays seen to have intrinsic value, and it (and the practices it involves) has a central position in debates on children’s education and development (Ozanne and Ozanne Citation2011). We, therefore, understand playing as a practice that constitutes a context for the reception of stimuli because actors influence how, when, and with what objects children play.

As objects of play, toys are designed not only to live up to economic rationalities but also to entrepreneurial self-conceptions of the company producing them (Sutton-Smith Citation1997). Applying these considerations to Lego, one can conclude that the dynamics of learning also become productive when playing with Lego bricks. As Joyce Goggin (Citation2017, 147) argues, Lego playsets generally come with information about “typical, predictable, affect-producing scenarios” that are templated in building instructions, advertisements, and preformed bricks (see also Lachney Citation2014; Pirrie Citation2017). In this regard, scholars from both psychology and the educational sciences have shown that what children ought to learn through play are the social norms, values, and concepts that are predefined by parents, peers, and others (see, for instance, Lauwaert Citation2009; Ozanne and Ozanne Citation2011; Hayward Citation2012; Mertala et al. Citation2016).Footnote5 The influential concept of “scaffolding” (van de Pol et al. Citation2010; Hayward Citation2012) emphasizes that it is impossible not to send out stimuli rooted in perceptions and knowledge toward learning persons. Put in the words of IPE, discursive power is enacted in these dynamics, through the design and description of the product as well as its usage, which is the ritualized practice of playing, two acts which we see as inseparably interwoven (Hardy and Thomas Citation2015). According to Michael Lachney (Citation2014, 166) Lego bricks, “as technological artefacts, embody certain forms of order and power” and “have become common currency for certain understandings and explanations of how the socio-technical world is built.”

Related to the everyday meaning of Lego toys in daily practices is their role as technology, that is, materially stabilized objects with a certain function. From an STS perspective, “language has been granted too much power” (Barad Citation2003, 801) while figurative representations of power remain out of sight. From this perspective, Lego bricks, and toys in general, can be understood as a materialized transmitter for discursive power and therefore provide an additional avenue (alongside corporate reports and other communications) through which power can be analyzed. Underscoring this point, Bruno Latour explains that discursive speech acts are often manifested through material interactions that are “adding reality” to spoken words (Latour Citation1991, 104). The performativity, the effective and repeated exercising of discursive power, hereby relies on a responsive, materialized relationship of an actor with an object that becomes a vehicle for translating meaning. The object, in this reading, becomes an agent (“actant”) on its own, as it reiterates reality, though this might work through different logics than intended (see also Winner Citation1980; Latour Citation2009). For example, in the case of Lego, producing preformed building bricks might be more suited “in order to be able to predict the path” (Latour Citation1991: 105) of children’s play. However, this comes at the cost of the players’ creativity. The same goes for the interaction of discourse and material sparked by commercials and building instructions. These sources visually assign certain usefulness to the material (bricks) and reproduce the perceived value and meaning of the material in question (see also Yarrow and Kranke Citation2016).Footnote6 As a consequence, we argue, playing with Lego building sets is a potent source for generating discursive power which is relevant for the re-significations of norms and ideas.

The re-signification process as a heuristic device

To analyze the relationship between playing and its potential reception, we use the re-signification process, as suggested by Graf (Citation2016), as a heuristic device. Graf shows, using the example of corporate reports of transnational retail companies, how TNCs adapt certain norms of sustainability in their corporate communications, how other actors then receive the stimuli of the communications, and how this finally leads to a consolidation – a temporary stabilization – of discourses on sustainability among the broader public. The Greenpeace campaign outlined in the introduction motivates us to consider the act of playing with Lego as an expression of discursive power which can be analyzed with the help of the re-signification process. Empirically, we study Lego building bricks and the stimuli they send out for reception in the “everyday practice” of playing.

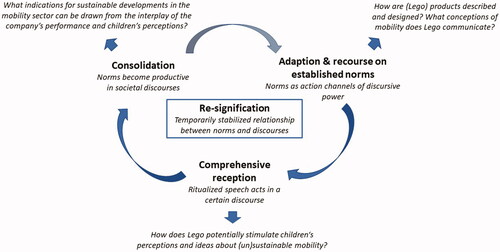

The three stages of the re-signification process – adaption, reception, and consolidation – allow us to refer to the abstract and complex processes of meaning-making. Applying this process to the Lego case, we can easily identify all three steps of re-signification (). Adaption and recourse on established norms refer to the way actors are “filling out” the meaning of a concept by referencing established norms in their communications. Theoretically, this occurs when actors express the “rules of formation,” among others, in the form of “norms” (Foucault Citation1972) which can be seen as more stabilized discourses with an “action-guiding dimension” (see, for example, Björkdahl Citation2002).

Figure 1. Re-signification of discourses through playing (with Lego). Derived from Graf (Citation2016, 82).

We interpret the act of playing with Lego building sets as an interaction that involves the adaption of and recourse on established norms. In line with this view, it follows that children are invited to build a world through the act of playing with Lego, using parameters Lego is setting. Lego toy designers are likely to orientate themselves toward how they perceive the “real” world, reiterating established norms of “how things are normally” (also see Huelss Citation2017). Ideas and values are hereby materialized and visualized in commercials, building instructions, and the toys themselves to stimulate (potential) consumers (e.g., players by forcing them to play in a certain and typically expected way) (Latour Citation2009, Citation1991). Addressing in that way might normally follow the foremost economic rationalities: Lego will continue to produce what it expects to sell.Footnote7 But arguably, they also depict the world how they want it to be – economically speaking, as well as concerning their values. By considering toys as material transmitters of certain norms, discourse is here understood in a way that encompasses lingual and material objects (Barad Citation2003). The Lego toys in that sense are pre-structured by lingual, but more importantly visual discourses, that “constitute it by bringing phenomena into being through the way in which they categorize and make sense of them” (Hardy and Thomas Citation2015, 681). We conclude that in their “everyday practice” of playing, children materially construct and perform other humans’, mostly adults’, “everyday practices” on a small scale, encouraged by Lego, parents, and peers. Hence, our sub-questions for the first stage of re-signification are: How are (Lego) products described and designed? What conceptions of mobility does Lego communicate?

Comprehending the reception of norms focuses on how communications affect the process of identity formation when they are received by the intended audience and thereby become stimuli for identity formation. Judith Butler (Citation1990, Citation1997) states that a subject integrates a stimulus in the process of identity formation if it fits with the subject’s existing knowledge and identity system. Later, she then interlinks the process of becoming intelligible as a subject with the performativity of the ritual (Butler Citation2015, Citation2008). We consider playing as a ritualized everyday practice (Sutton-Smith Citation1997) which is essential for the process of identity formation. Nevertheless, we argue alongside Butler (Citation1997) that convincing and creditable “signifiers” help to value personal preferences. The signifiers bear what the subject believes, likes, or prefers. With repetition, children and other players learn routines and playing gains a performative status. Relatedly, Lego bricks as material artifacts ‒ actants ‒ help to constitute this understanding of what children perceive as being (un)normal and (non)pleasant. In other words: children learn what seems to be aspirational. Thus, for the step of comprehending reception of norms, we ask how Lego potentially stimulates children’s perceptions and ideas about (un)sustainable mobility? Of course, we cannot reconstruct the cognitive procedure of identity formation as our colleagues from psychology might do. Nonetheless, it seems implausible to us that the societal and corporate values materialized in toys are irrelevant when children are playing with them, continually and repeatedly for years and across generations. This is, however, not to say that the norms, values, and practices that are performed in playing with Lego will necessarily materialize in the “real” world once the (former) players are themselves reenacting the social practices once learned, an aspect that is central to the last step of the re-signification process.

Consolidating the adaption and reception of norms involves analyzing the interplay of articulation and potential reception of the norms. Consolidations may be seen as intersections in the omnipresent net of power, providing information about how similar ideas might be spread in a specific setting (Foucault Citation1982). An important part of re-signification is when an individual “cites” knowledge with which they are familiar (recourse on established norms in the articulation). The reception of these contents is up to the subject but is also affected by stimuli for identity formation (comprehending reception). The consolidation elaborates on the interaction of the first two steps and allows for conclusions on the course and character of discursive power. Hence, we ask at the last stage of the re-signification process what indications for sustainable developments in the mobility sector can be drawn from the interplay of the company’s performance and children’s perceptions? It is important to note that we are not studying the consequences of re-signification for individuals – this would mean to explore the “black box” of cognitive processing, which is beyond our scope and would require long-term studies including children, their practice of playing, and then their behavior at a much later stage in adult life. This, to be sure, also requires a capacity to do so, dependent on many other social and material prerequisites (see also Butler Citation2010). Instead, we limit our analysis at this point to relating the adaption of norms (via playing sets) to consolidated identity categories in the context of (un)sustainable mobility.

Methodology

To strengthen the dynamics of playing and discursive power as outlined, we undertook an explorative, hermeneutic analysis of different content produced by Lego. As we are interested in how Lego is re-signifying discourses of (un)sustainable mobility, we analyzed material in which Lego depicts certain forms of mobility. In particular, we examined the different building sets that were available for retail sale in Germany and the United States in July 2019, as well as the commercials and short movies that Lego distributed. With a “snowball system” approach, we widened the scope of analysis beyond textual sources and also included audiovisual material (Schwartz-Shea and Yanow Citation2012; Aradau and Huysmans Citation2014; Weldes Citation2014).

We collected material in which different structures and habits of mobility are depicted, excluding those regarding fictional “worlds,” such as the Star Wars branded playsets. With regard to the building sets, as well as their descriptions, instructions, and depictions, we selected all building sets from the Lego Online Shop that included some form of “everyday” mobility.Footnote8 We excluded sets that showed vehicles but depicted those for solely industrial purposes (for instance sets portraying “mining”). The audiovisual commercials were elicited from Lego’s own YouTube channel. We included videos that referred to mobility in their title or description (using keywords such as traffic, transport, road, bicycle, bus, train, car, and so forth) or that were real-world situated short movies or product presentations (mainly referring to the Lego City and Lego Friends product series).

In total, 25 building sets and 11 promotional videos were inductively coded using the software MAXQDA, which helped to integrate hermeneutic content analyses (Schreier Citation2012) of different textual and visual sources (e.g., videos, pictures, texts) into a coherent category system (Kuckartz and Rädiker Citation2019). We coded still images, video segments, and pictures, as well as textual descriptions concerning their depiction of mobility structures and practices. In addition, we randomly included building sets that are no longer on sale to account for significant change within the design of Lego playsets.Footnote9 By obtaining and processing the material in this way, we were able to identify and discuss the contents concerning (un)sustainable mobility that Lego (re-) signifies as well as identifying ways in which Lego likely contributes to the creation of “new” imaginaries of sustainable, future-orientated mobility.

Results: Re-signifying (un)sustainable mobility

We use the tripartite structure of the re-signification process as a heuristic tool to facilitate the empirical analysis of Lego building sets and commercials, thereby widening the scope of this study beyond the textual dimension of discourse. This extension seems necessary given the role of material and visual “actants” as powerful objects we have derived from STS scholarship.Footnote10 The following provides a comprehensive overview of our results.

Table 1. Results of the empirical analysis.

Overall, the analysis suggests a supportive role of Lego for the system of automobility and its consequences for fossil-fuel dependency, everyday practices of mobility as well as societal models and values. In what follows, we present our findings in more detail.

Adaption of and recourse on established norms: dominance of the car

Mobility structures and mobility habits are a common theme in Lego playsets, commercials, and other marketing communications of the Lego company. Notably, many building sets are dedicated to service mobility units, including social services vehicles like police vehicles and ambulances. Many other sets include forms of mobility that relate to leisure or entertainment. They include, for instance, vehicles linked to motorsports and adventure themes. In the following section, we illustrate how established norms of mobility are reproduced by Lego building sets and how stimuli for reception address children in the act of playing.

The car as dominant transport mode

During the first half of 2019, a total of 191 new Lego products were released on the German market of which 83 could be considered “real world” themed.Footnote11 Only two sets included a bicycle, busses, and/or trains as forms of public transport. Yet, mobility, in general, was often referred to in building sets. The same 83 sets included 19 cars, 13 trucks or other heavy vehicles, four airplanes, five helicopters, six motorcycles, nine boats, and ten “special vehicles.”

While bicycles and public transport vehicles were included more frequently in other, older building sets, the dominance of cars and other motorized vehicles is striking. This dominance occurs primarily because many of the sets are linked to rescue or security services, whose vehicles continue to be necessary. However, some sets, such as the 2019 Heartlake City Super Market (Product #41362), include a car but for no apparent reason. Here, the Lego set is suggesting that the “everyday practice” of going to the supermarket is necessarily linked to using a car. This is also visible in other consumption-related building sets, which – in addition to depicting the consumption facility – include cars.

The observable dominance of cars in building sets continues into Lego’s marketing. For example, a 2015 commercial presented a selection of Lego City products. Although the whole video is set in a city, it only includes one bicycle – which is ironically fished out of the harbor. As in the building sets, the city depicted in the commercial contains several references to car-based transport in several ways: the cars themselves, a car dealership, car tires, and something that resembles a podium for a car or motorcycle race (Lego Citation2015).

The car and car driver as “heroes”

Because Lego building sets and commercials tend to have an “adventure orientation,” Lego also depicts the heroes of these undertakings. However, in nearly every video that we observed, this heroism is linked to car use. In these videos, the cars are pictured as strong and, thus, a necessary part of succeeding in a particular venture, be it a heist or a fire emergency. Additionally, and not at all limited to children’s entertainment, the abilities of cars and other vehicles are depicted in a thoroughly unrealistic way (see for instance Lego Citation2018a, where different vehicles perform hazardous maneuvers). It is especially in those heroized sets and commercials that certain features of cars – speed, strength, and so forth – are highlighted. While certain Lego building sets do refer to mobility alternatives, such as electric mobility, these alternatives are entirely invisible in advertisements and adventure-themed videos. Instead, these sources often depict black exhaust fumes, which electric cars do not emit, to illustrate strength, and the vehicles frequently drive off-road and, in doing so, have a destructive impact on the natural environment. In general, the hazardous behavior depicted in the commercials has no adverse consequences.

In sum, in Lego commercials, the Lego series and movies, cars and/or their drivers are pictured as heroes. The logic and necessity for this experience, as well as the connected social “good,” are not questioned.

“Branding” of Lego building sets

Though Lego has ended its infamous cooperation with Shell, it continues to “brand” products, especially those related to mobility patterns. Several car manufacturers maintain cooperative partnerships with Lego in different product series, ranging from the Lego Technic series to the Lego Vintage series. None of the cars listed in the catalogue represents “new” environmentally friendly technology. While the vintage-themed models are by definition linked to combustion engines, most of the more recent cars depicted are designed exclusively for “fun.” Newer models tend to embody a racing design that serves few functions beyond moving passengers (and only two passengers for the most part) from one place to the other in the shortest amount of time possible. In many of these sets, the car engines are neatly designed and even have movable pistons. Lego often focuses on these features in the advertisements.

Lego continues to celebrate its cooperation with other companies in high-profile ways, for instance, by producing life-size, fully functional models of cars – for example, a Bugatti Chiron (Lego Citation2018b). Other brands depicted on Lego products include the fuel company Esso (a subsidiary of Exxon/Mobil), the motor-oil company, Castrol, and the tire producer Michelin (for example set with product #75885). Thus, even though the protest against Lego’s cooperation with Shell seems to have been a wakeup call, the company continues the practice of branding in its building sets and, thus, is continuing to send out stimuli about unsustainable industries.

Niches in Lego: Breaking up of the combustion frame?

Although Lego products overwhelmingly display unsustainable mobility habits and structures, they do depict sustainable forms of mobility in single building sets. Three sets incorporate e-mobility: one contains a private charging station for an electric car (Product #31068), one has a charging facility at a gas station (Product #60132), and the signature set, Capital City (Product #60200), has an electric car.Footnote12 Of note though, the Capital City set does not, aside from the electric car, include any other form of “sustainable” transport, only four other motorized vehicles. Although public transportation vehicles have been featured in multiple building sets in the past, and some of Lego’s commercial videos depict them alongside other forms of mobility, they seem to be included only as a perfunctory necessity. For instance, in the short movies that we analyzed, the “acting” parts are reserved for cars and other private or commercial vehicles. While Lego has developed a way to depict “new” mobility and has included it in some building sets, these types of mobility do not feature in their most recent offerings, such as those in the 2019 catalogue. Consequently, depictions of e-mobility remain marginalized, framed as the “other,” especially when compared to the number of depictions of conventional cars.

Comprehending reception of norms: playing and mobility as parts of children’s everyday life

Regarding comprehending reception of norms, we asked how do toy companies potentially stimulate children’s perceptions and ideas about (un)sustainable mobility with the help of artifacts (here Lego toys) and to what extent do the stimuli the Lego company is sending out influence children’s processes of identity formation.

Intergenerational linkage

As the Lego brick system itself has remained largely unchanged since the 1950s, children’s parents and other caregivers likely related to Lego in the same way as their children do today (Lauwaert Citation2008). As such, adults are likely to promote Lego as a valuable toy, since it contains memories of their own childhood and development. Therefore, Lego sets provide yet another avenue for performance, upon which parents transmit their values to their children as a form of generational learning and “informal education” (Francis Citation2010, 327; Robertson Citation2013, 26). In this way, Lego, as a creative toy, becomes a medium for “scaffolding” as explained above. This link is stabilized further as Lego recites cultural aspects of mobility. Most Lego car models have a cultural status themselves (for instance the VW Beetle, Product #10252) that makes them aspirational and gives them a distinct social status as consumers may find their parent’s car or the cars of other role models (similarly, for energy-consumption practices, see Hansen and Jacobsen Citation2020).

Shaping creativity

As outlined above, licensed building sets in cooperation with entertainment companies and branding strengthens Lego’s visibility.Footnote13 Lego’s partnerships have included various movie studios as well as industrial companies (for example Shell, Ferrari). The omnipresence of brands hereby extends the problem of unsustainable mobility, as the persistence of an entire capitalist economic system is normalized (also compare to the analysis of Goggin Citation2017), of which mobility is one integral part. Automobility has been considered a pillar of individual economic welfare, connected to the ideal of business success and freedom (Stockmann and Graf Citation2019). This logic is reiterated through the depiction of car brands that have been drivers of this dynamic, such as Volkswagen in Germany or Ford in the United States.

When it comes to reception, licensing and branding often determine a definite aim for playing sets, as referred to in the recourse on established norms. Lego, in particular, is subject to these practices, even though at first sight, the design of the bricks might seem to offer unlimited opportunities for the user’s creativity (see Robertson Citation2013; Mertala et al. Citation2016). This orientation is also mirrored in the company’s testimony of “serving the builder of tomorrow” (Robertson Citation2013, 17). But, on second glance, the building sets limit this kind of creativity to specific trajectories. With our perspective on the discursive power exerted by Lego, we can state that the company differentiates between public spaces for all people and car-owned spaces. With the dominance of the automobile presented in the building sets (see also adaption of norms), children are informed, from a very early age, that cars need most of the space designated for mobility. Bicycles and public transportation appear less frequently in the sets and adventures are mostly carried out with motorized means of mobility. Thus, children receive stimuli while playing with Lego that bicycles, public transportation, and especially pedestrians are rare and subordinate forms of mobility.

Bricks that materialize “fossil-fuel dependency,” engines that question it

More than just the shape of Lego building bricks, it is also worthwhile looking at the material they are made of: fossil-fuel resources are the main component of Lego bricks. Consequently, petroleum is a necessity for playing with Lego regardless of anyone’s intention what to build with the bricks. As a contrast to the current reliance of Lego products on fossil fuels, functional engines – mainly in the Lego Technics series – are always electricity-based. In this series, while building vehicles in a taxing way that provides an accurate technical understanding of, for example, mechanics, players do engage with electricity as material. We derive from these observations the notion that the materialization of certain norms within Lego bricks is also to be understood as a potential reception mechanism for stimuli referring to norms of (un)sustainability.

Consolidation: Stabilizing the norms of car-centered mobility

The third stage of the re-signification process, the consolidation of discourses of (un)sustainable mobility, was much more challenging to uncover with the means of our analysis. In the case of playing, many stabilizing effects of the previous steps of re-signification might only be accessible over a long period and through complex psychological experimental studies. Instead, we analyzed the interaction of a leading toy company with societal norms and discourses stabilized in the act of playing with the help of building bricks. Our study has shown that it is highly likely that Lego stimulates a reception of car and fossil-fuel dependency as social norms of mobility practices and structures. Other mobility scholars have highlighted this persistence of such unsustainable mobility habits and structures in socio-cultural realms (Paterson Citation2007; Davidson Citation2012; Cass and Manderscheid Citation2018; Hanna et al. Citation2018; Manderscheid Citation2018; Lindqvist et al. Citation2019).

Car-dependency and car superiority

When playing with Lego sets, children gain the understanding that “the everyday” is normally managed with the help of a car in an environment that is built for vehicles. Lego players are accustomed to car-bound infrastructures and the apparent convenience and safety the usage of a personal automobile promises. Above that, children are encouraged to learn to “handle” the luxury of owning (more than actually using) not only a car but a certain car. Here, the norm of the car as an indicator for wealth and as a status symbol for a distinct class or gender is manifested over generations and among a peer-group of players (also see Hanna et al. Citation2018; Cohen Citation2012).Footnote14 Big, “sporty” models are established as a benchmark, and individual car manufacturers are granted a cultural status themselves, up to becoming a norm for specific subjects. Whether these vehicles also have practical value over other forms of transport for everyday activities remains unanswered.

This normalization of knowledge about the car’s primacy on our roads and in our cities in our understanding limits the “endless creativity” that is central to Lego’s corporate identity. We did not find stimuli questioning the modal split in urban areas in our sample. Nor did we identify stimuli for reception of comfortable, pleasant, fascinating, and grown-up ways of travel in forms of transport other than the car. In light of the important role mobility plays in the building sets and the high moral values outlined in Lego’s corporate governance, the educational content falls short of the TNC’s own requirements. Where sustainable forms of mobility are included in Lego, they seem to be marginalized add-ons, theoretically speaking the “other” to the dominance of conventional cars. Possibly, if Lego were to depict more sustainable forms of mobility, this might, in turn, contribute to normalizing them and even assist in stabilizing alternative discourses on mobility. If children were to see and learn that these forms of mobility fulfill the same aims (concerning the act of moving), they might eventually also start to question the conventional modes of transport. In this way, playing with Lego could fuel discourses around the idea of sufficiency as a new, emerging norm in the light of ecological challenges and highlight that we could decide to consume less and thereby contribute to sustainable change (Princen Citation2005; Cohen Citation2017).

Fossil-fuel dependency

Regardless of what shape a collection of Lego bricks eventually takes, building and playing with them reinforce “fossil-fuel dependency,” as petroleum remains the core component of the product itself. While it is not possible to trace the infamous collaboration of Lego and Shell back to its “original sin,” Lego cannot avoid the criticism that a company so dependent on fossil fuels will likely not problematize their usage in other sectors. In this case, structural power lock-ins become a hypothecary for Lego on a discursive level. Lego’s perceived ability to use or not to use discursive power might, to some extent, be linked to what it sees as possible and responsible as both a value-orientated and economic actor (Goggin Citation2017: 147). Lego has pledged to make the production of its bricks less reliant on petroleum by 2030, and the company recently introduced the first plant-based bricks (Lego Citation2019a). This indicates that the company is aware of the problem.Footnote15

Ironically, as discussed above, Lego demonstrates sustainable mobility options in every motorized Lego vehicle, as these are all technically e-vehicles (even though they might not be designed as such). To further strengthen this point, the fully functional Lego Bugatti model is, according to Lego, also powered by over two thousand single electric Lego Technic motors enabling it to move at a decent speed (Lego Citation2018b). Hence, playing with Lego bricks, in turn, also materializes the fact that vehicles can move without having to burn fossil resources, using the (playing) material that is likewise used to reproduce the norms of unsustainable mobility.Footnote16

Discussion and conclusion

In the video outlined in the introduction, the biotic as well as the abiotic environments – built with Lego bricks carrying the Shell, or other, company insignia – are swallowed by a thick, black substance which is literally overtaking everything. What the Greenpeace campaign suggests when depicting people and infrastructures drowning in an ocean of – presumably – oil is: If we do not renounce fossil fuels, all businesses will have to end. Given the background behind Lego’s branding strategy, the company’s cooperation with Shell is all the more surprising and does not fit with its corporate self-description and “promises” which depict the company as the responsible enabler of creative play and the educator of the “builders of tomorrow” (Lego Citation2016b). Since achieving transformations in the mobility sector has proven to be quite difficult, even deepening dependency on fossil fuels, we wanted to take a closer look at this inconsistency. Why is the mobility sector so resistant to change? Coming from a mobility cultures perspective, we asked what discourses on mobility are stabilized temporarily with the help of the company producing one of the most important and widespread toys in the world: Lego.

To assess Lego as a transnational actor, we adopted a business-power perspective which highlighted the meaning of norms and ideas in the re-signification process. The re-signification process theorizes the examination of discursive power. Its three stages – adaption, reception, and consolidation of norms and discourses – set out the complex constitutional process of actors representing and, at the same time, reproducing societal norms. To adequately integrate children and the act of playing, we have added insights from social psychology on learning. Toys as materialized norms, or in more stylized jargon from the field of STS, actants, which are producing social meaning, have completed the theoretical layout. As illustrated above, Lego’s reach is framed by the already established and still expanding presence of its product. Whatever normative stimuli the company might want to send, it can rely on the fact that the bricks as the materialized surface for this impulse, are globally accessible and visible, both in public as well as in ostensibly private spaces (see Johnson Citation2014). Given the “everyday” presence of the product, we demonstrate that Lego’s discursive power is closely tied to conceptions of playing and learning, which help reproduce the socio-cultural status of the company as well as the societal and cultural norms that reach far beyond it (Huizinga Citation2017; Hirst Citation2019).

During the first step of the re-significations process, the adaption of norms, we found that cars dominate the types of mobility depicted in Lego building sets while bicycles, pedestrians, and sustainable forms of mobility are underrepresented. Furthermore, the usage of cars is linked to adventure, heroism, and fun. An opposite conclusion constitutes new, emerging discourses of declining travel, transport efficiency, or fuel reduction as “the boring and unnormal other” to the dominance of the car. Since sustainable forms of mobility remain marginalized in the material analyzed, we conclude that the products and advertisements of Lego are re-signifying norms that consolidate a fossil fuel-based concept of mobility and, thus, promote discourses on unsustainable mobility.

In the second and third steps of the re-signification process, the comprehensive reception and the consolidation, we identified visual and material stimuli that referred to mobility habits encouraging users to become accustomed to a car-centered building environment. These stimuli include an intergenerational linkage that reinforces the idea that certain forms of mobility (and the ability to “play” them) are valuable. The aspirational longing is not exclusive to children; in the field of mobility, in particular, Lego products are also targeting parents and other reference persons. Through “vintage” cars or ambitious technical features, “adult players” are subject to Lego’s products.

Furthermore, practices of branding stimulate the notion of luxurious and desirable lifestyles. In turn, we did not find stimuli that questioned the modal split in urban areas or car driving, which is related to comfortable, pleasant, fascinating, and grown-up ways of travel. Consequently, we conclude that children’s creativity is restricted while playing with Lego. We did not find evidence for stimuli creating a positive idea of sustainable mobility. Instead, the knowledge cited in our sample is inevitably bound to established norms of (car-centered) mobility with regard to audiovisual manifestations of speed, noise, and superiority, both economically as well as culturally. Finally, playing with Lego products themselves materializes a “fossil-fuel dependency,” as the main component of the building blocks is still oil.

Lego products only rarely offer niches to strengthen counter-discourses of future sustainable mobility. From this perspective, our analytical connection of individual micro-politics with societal development on a macro-level shows the enormous relevance of Lego as that of children's entertainment more generally spoken to both mobility research and IPE, since the interlinkages of learning and playing with questions of sustainable development are just as striking as the critical assessment of global economic and social norms.

The empirical results of this contribution address Lego, but they carry implications for other companies in the toy or entertainment sectors. Further research might, therefore, widen the scope and include other companies and other mechanisms beyond those discussed here. Deconstructing rituals and everyday practices such as “playing” has the potential to generate knowledge about how to politically and socially address the needs and claims embedded in them and thus facilitate the emergence of future-orientated niches that challenge the current ideas of a “good life.”

That said, toy (and related) companies and the performative act of playing have the potential to not only hinder and re-signify unsustainable forms of mobility, they also can contribute to the production of future-orientated imaginaries of sustainable mobility and other sectors as well (see Shove and Walker Citation2010; Hajer and Versteeg Citation2019), through a “fusion of the discursive and the material that generates the power effects of discourse and allows for change to occur (or, alternatively, prevents it from happening)” (Hardy and Thomas Citation2015, 690).17

Again, we find exposure to STS scholarship helpful in strengthening this notion. John Law and John Urry in their reflection on the enacting quality of social science research, for instance, claim that “if social investigation makes worlds, then it can, in some measure think about the worlds it wants to help to make” (Law and Urry Citation2004, 391). The non-possibility of neutrality of science (Law and Urry even speak of innocence), we argue, is readily applicable to the act of playing. Thus, it reinforces the notion that the design and art-of-play of Lego products partially shape “the world.” An anecdotal reference underscores this impression: Lego has never launched building sets on war, upholding the conviction that “war should never be part of children’s play” (Johnson Citation2014, 320; Robertson Citation2013, 40). Despite the compromises within particular licensed, “fantasy” sets, the company has maintained the idea of not showing violent conflicts. Also, the police forces within Lego are not equipped with weapons, and neither are bandits, grave robbers, or other “villains.” In this case, the Lego company has arguably made a foremost normative decision not to depict violence. Conversely, in our analysis, we did not find convincing evidence for a likewise normative conviction regarding sustainability, or, bluntly expressed “violence against the planet.” Nevertheless, actors, here the TNC Lego, should possibly be attributed the agency to decide to “engage in an ontological politics, and to help shape new realities” (Law and Urry Citation2004, 404) even though this might be “uncomfortable.”

Such endeavors, we argue, are crucial for enriching both the scientific and public debate that is still dominated by economic and technical reasoning instead of social and cultural considerations on how to bring forward sustainable transformation, in our example that of mobility. Hence, critical and “everyday” IPE scholarship and conceptualizations of discursive power could gain enormously by integrating these STS perspectives, something we have already emphasized. Here, we argue, for a more focused theoretical discussion that will point to interesting similarities between both disciplines and identify fruitful perspectives for further research.

Acknowledgements

The authors are thankful for the valuable comments of the journal’s editor and the anonymous reviewers, which helped to improve this article. Earlier versions were presented at a workshop of the German Political Science Association’s (Deutsche Vereinigung für Politikwissenschaft) working group “International Political Economy” in June 2019 and the European International Studies Association’s 13th Pan-European Conference in September 2019. We highly appreciate the open and constructive feedback of all colleagues who were present. The authors also acknowledge the editing work of Julie Davies and the research assistance of Christoph Köster and Julia Hansel.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 “In contrast to the mainstream,” as Georgina Waylen (Citation2006, 146) puts it, “critical IPE is based on ontologies that give primacy to the construction of social relations and its epistemologies are sceptical of empiricism and positivism. “While the discussion about the boundaries of critical IPE is far from being exhaustive (Kranke Citation2014; Bruff and Tepe Citation2011), we consider this still broad focus as a good situation of our own approach.

2 In 2018, Lego had revenue of approximately US$2.5 billion (Lego Citation2019b, 12). The five biggest companies in the sector - Lego, Mattel, Namco Badami, Hasbro, and JAKKS Pacific - earned revenues up; to approximately US $21.8 billion in 2016, roughly a quarter of the global toy market (Statista Citation2017, 8). According to the latest annual report released by the company, Lego employed 17,385 people worldwide in 2016 (Lego Citation2019b, 13). Production sites for the Lego bricks are currently located in Hungary, Mexico, China, Czech Republic, and at the headquarters in Billund, Denmark (Lego Citation2020).

3 The Christiansen family operates and fully holds the KIRKBI company, which in turn owns 75 percent of the shares of the Lego Group. The remaining 25 percent of the company’s shares were allocated to the Lego Foundation in 1999 (Lego Citation2013), which was set up in 1986. According to its website, the Lego Foundation is dedicated to “[p]artnering with others who already work within the field of promoting play and quality early childhood education ... to achieve a strong, sustained impact” (The Lego Foundation Citation2018). Through different educational projects, often including Lego products as a medium, the foundation aims to support children from different contexts, such as marginalized children or children in orphanages, as well as promote talent in technological subjects.

4 A comparable example would be Lego’s dependence on the energy sector in terms of production. Regarding this aspect, Lego strives to become more independent (and thus credible) by making large investments in renewable energy projects that fuel its own production sites (Lego Citation2017, Citation2016b). In the same manner, the company has started trials for Lego bricks made from plant material (Lego Citation2019a).

5 Those approaches, which cannot be discussed here at length, are rooted in social theory (for instance Durkheim Citation1982; Derrida Citation2001; Huizinga Citation2017; for a timely discussion see Reckwitz Citation2002). Durkheim (Citation1982, 9), for instance, claims that “it is very easy to make a child acquire habits” and that, consequently, the influence of educators on children must be carefully reflected upon. While “habit” as in Durkheim’s conclusion refers to a practical skill a child might learn, we must acknowledge that the influence of playing extends to children’s mindsets, or in other words, the values and norms a child might acquire.

6 At this point, we use the STS perspective mainly to strengthen our approach to playing as an everyday and materialized practice through which discursive power becomes productive. We are well aware that the relationship between IPE power frameworks and STS approaches, regardless of the obvious alignments, is far from fully developed here and that further work would be needed to establish a sound theoretical framework integrating both perspectives.

7 The question how Lego, through its corporate business and the design of its toys, is reproducing established inequalities and dependencies of the global economic system is likewise interesting (see for instance Goggin (Citation2017) on the reproduction of financial security; also Baltodano (Citation2017)). Though we are aware of this aspect (and thank the reviewers for strengthening this aspect) we are unable to include it in our analysis at this point.

8 See https://www.lego.com/en-de.

9 Information on these “historic” building sets were collected from a database of building instructions provided by Lego dating back to 1989.

10 Originally, we intended to illustrate our empirical findings by including some of the images that were part of our dataset. Due to an unanswered request for permission to use the pictures that are property of the Lego company, we are not able to include them.

11 This and the following information on Lego products were, if not otherwise cited, elicited from the Lego “Product Database” accessible via the following link: https://www.lego.com/en-de. In the following sections, distinctive building sets are referred to by their product number within that database.

12 There is, of course, a whole discussion around the question of whether individual e-mobility as depicted in the Lego building sets is “sustainable” at all or rather whether it contributes to the hegemonic position of “the car” as the focal point of mobility habits (see for example Brunnengräber and Haas Citation2018).

13 Here understood as “an industrial practice by which intellectual property owners (licensors) assign rights of use to paying third parties (licensees) granted limited markets or territories by the agreement” (Johnson Citation2014, 310).

14 Contrary to what the studies on the “gendered” nature of Lego toys we have already cited might suggest, we did not find that “heroism” as related to the use of cars or other “strong” vehicles was reserved for male characters or figures. While the dichotomy of play sets, as identified for instance by Black et al. (Citation2016) prevails, both series show adventure, leisure, and heroism linked to motorized mobility. Yet, the play themes largely differ. While Lego City sets tend to show more technical scenes and focusses on the motif of “emergency” – enacted by both male and by female characters – the Lego Friends series centers around practices of leisure, such as vacation trips or shopping activities. Interestingly though, several sets in the latter series are dedicated to the theme of car racing (for example sets #41351, #41352). As interesting as this aspect is, we are unable to discuss it in greater length. While the dichotomy might reproduce the norm of men/boys “saving or fixing the world” while women/girls are satisfied with their adventure being in their private “leisure time”, this aspect encompasses our focus on mobility practices, though, these are without doubt a part of this issue.

15 Furthermore, one should note that Lego rightfully refers to the Lego bricks’ longevity (Lego Citation2019a). The high durability and the originally simplicity and flexibility of the product, establish a reasonable impression of sustainability with regard to re-usage of the same bricks over a long time (and possibly of different “players”; Pirrie Citation2017). It is noteworthy that this potential is bound to the simple product design, that is somewhat contrary to the trend of producing branded and preformed building sets and bricks.

16 These dynamics come close to what Goggin (Citation2017) describes with regard to the “irony” of playing with or watching Lego media. While someone might want to build something “transformative” they rely on systemic logics and lock-ins to do so (and vice versa). This irony was described by Butler (Citation1990) as one of the only possibilities to performatively address discursive power and its re-signification. However, to achieve this, the irony needs to be uncovered as such in a subversive way (Lukács et al. Citation2011), something that, to our knowledge, has not been addressed in the Lego case from neither a scholarly or an activist point of view.

References

- Aradau, C., and J. Huysmans. 2014. “Critical Methods in International Relations: The Politics of Techniques, Devices and Acts.” European Journal of International Relations 20 (3): 596–619. doi:10.1177/1354066112474479.

- Baltodano, M. 2017. “The Power Brokers of Neoliberalism: Philanthrocapitalists and Public Education.” Policy Futures in Education 15 (2): 141–156. doi:10.1177/1478210316652008.

- Barad, K. 2003. “Posthumanist Performativity: Toward an Understanding of How Matter Comes to Matter.” Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 28 (3): 801–831. doi:10.1086/345321.

- Berenskoetter, F., and M. Williams. 2007. Power in World Politics. London: Routledge.

- Best, J. and M. Paterson, eds. Cultural Political Economy. London: Routledge.

- Björkdahl, A. 2002. “Norms in International Relations: Some Conceptual and Methodological Reflections.” Cambridge Review of International Affairs 15 (1): 9–23. doi:10.1080/09557570220126216.

- Black, R., B. Tomlinson, and K. Korobkova. 2016. “Play and Identity in Gendered LEGO Franchises.” International Journal of Play 5 (1): 64–76. doi:10.1080/21594937.2016.1147284.

- Bruff, I., and D. Tepe. 2011. “What is Critical IPE?” Journal of International Relations and Development 14 (3): 354–358. doi:10.1057/jird.2011.7.

- Brunnengräber, A., and T. Haas. 2018. “Vom Regen in Die Traufe: Die Sozial-Ökologischen Schattenseiten Der E-Mobilität [Going from Bad to Worse: The Socio-Ecological Downsides of E-Mobility].” GAIA 27 (3): 273–276. doi:10.14512/gaia.27.3.4.

- Butler, J. 1997. The Psychic Life of Power. Theories in Subjection. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Butler, J. 2008. “Sexual Politics, Torture, and Secular Time.” The British Journal of Sociology 59 (1): 1–23. doi:10.1111/j.1468-4446.2007.00176.x.

- Butler, J. 2010. “Performative Agency.” Journal of Cultural Economy 3 (2): 147–161. doi:10.1080/17530350.2010.494117.

- Butler, J. 2015. Notes toward a Performative Theory of Assembly. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Butler, J. P. 1990. Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity. New York: Routledge.

- Carrington, V., and C. Dowall. 2013. “‘This is a Job for Hazmat Guy’: Global Media Cultures and Children’s Everyday Lives.” In International Handbook of Research on Children’s Literacy, Learning, and Culture, edited by K. Hall, T. Cremin, B. Comber and L. Moll, 96–107. London: Routledge.

- Cass, N., and K. Manderscheid. 2018. “The Autonomobility System. Mobility Justice and Freedom Under Sustainability.” In Mobilities, Mobility Justice and Social Justice, edited by N. Cook and D. Butz, 101–115. Abingdon, Oxon, New York, NY: Routledge.

- Chatterjee, P., and M. Finger. 2014. The Earth Brokers: Power, Politics and World Development. Abingdon, Oxon, London: Routledge.

- Cohen, M. 2010. “Destination Unknown: Pursuing Sustainable Mobility in the Face of Rival Societal Aspirations.” Research Policy 39 (4): 459–470. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2010.01.018.

- Cohen, M. 2012. “The Future of Automobile Society: A Socio-Technical Transitions Perspective.” Technology Analysis & Strategic Management 24 (4): 377–390. doi:10.1080/09537325.2012.663962.

- Cohen, M. 2017. The Future of Consumer Society. Prospects for Sustainability in the New Economy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Davidson, I. 2012. “Automobility, Materiality and Don DeLillo’s Cosmopolis.” Cultural Geographies 19 (4): 469–482. doi:10.1177/1474474012438819.

- Deffner, J., and T. Hefter. 2012. Handbook on Cycling Inclusive Planning and Promotion: Capacity Development Material for the Multiplier Training Within the Mobile2020 Project. Frankfurt: Institute for Social-Ecologial Research.

- Derrida, J. 2001. Writing and Difference. London: Routledge.

- Durkheim, E. 1982. “Childhood.” Thinking: The Journal of Philosophy for Children 3 (3): 6–9. doi:10.5840/thinking1982332.

- Foucault, M. 1972. The Archaeology of Knowledge: And, the Discourse on Language. New York: Pantheon Books.

- Foucault, M. 1982. “The Subject and Power.” Critical Inquiry 8 (4): 777–795. doi:10.1086/448181.

- Francis, B. 2010. “Gender, Toys and Learning.” Oxford Review of Education 36 (3): 325–344. doi:10.1080/03054981003732278.

- Fuchs, D. 2007. Business Power in Global Governance. Boulder, CO: Rienner.

- Fuchs, D., A. Di Giulio, K. Glaab, S. Lorek, M. Maniates, T. Princen, and I. Røpke. 2016. “Power: The Missing Element in Sustainable Consumption and Absolute Reductions Research and Action.” Journal of Cleaner Production 132: 298–307. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.02.006.

- Fuchs, D., and M. Lederer. 2007. “The Power of Business.” Business and Politics 9 (3): 1–17. doi:10.2202/1469-3569.1214.

- Goggin, J. 2017. ‘ “Everything is Awesome’: The LEGO Movie and the Affective Politics of Security.” Finance and Society 3 (2): 143–158. doi:10.2218/finsoc.v3i2.2574.

- Graf, A. 2016. Diskursive Macht. Transnationale Unternehmen im Nachhaltigkeitsdiskurs (Discursive Power. Transnational Companies in the Discourse of Sustainability). Baden-Baden: Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft.

- Graf, A., and M. Sonnberger. 2020. “Responsibility, Rationality, and Acceptance: How Future Users of Autonomous Driving Are Constructed in Stakeholders' Sociotechnical Imaginaries.” Public Understanding of Science 29 (1): 61–75. doi:10.1177/0963662519885550.

- Greenfield, P. 2009. “Technology and Informal Education: What is Taught, What is Learned.” Science (New York, N.Y.) 323 (5910): 69–71. doi:10.1126/science.1167190.

- Greenpeace 2014. “LEGO: Everything is NOT Awesome.” Accessed 7 July 2020. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qhbliUq0_r4

- Guzzini, S. 2005. “The Concept of Power: A Constructivist Analysis.” Millennium: Journal of International Studies 33 (3): 495–521. doi:10.1177/03058298050330031301.

- Hajer, M., and W. Versteeg. 2019. “Imagining the Post-Fossil City: Why Is It so Difficult to Think of New Possible Worlds?” Territory, Politics, Governance 7 (2): 122–134. doi:10.1080/21622671.2018.1510339.

- Halverson, E., and K. Sheridan. 2014. “The Maker Movement in Education.” Harvard Educational Review 84 (4): 495–504. doi:10.17763/haer.84.4.34j1g68140382063.

- Hanna, P., J. Kantenbacher, S. Cohen, and S. Gössling. 2018. “Role Model Advocacy for Sustainable Transport.” Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment 61: 373–382. doi:10.1016/j.trd.2017.07.028.

- Hansen, A., and M. Jacobsen. 2020. “Like Parent, Like Child: Intergenerational Transmission of Energy Consumption Practices in Denmark.” Energy Research & Social Science 61: 101341. doi:10.1016/j.erss.2019.101341.

- Hardy, C., and R. Thomas. 2015. “Discourse in a Material World.” Journal of Management Studies 52 (5): 680–696. doi:10.1111/joms.12113.

- Hayward, B. 2012. Children, Citizenship and Environment. Nurturing a Democratic Imagination in a Changing World. London: Routledge.

- Hirst, A. 2019. “Play in(g) International Theory.” Review of International Studies 45 (5): 891–914. doi:10.1017/S0260210519000160.

- Hobson, J., and L. Seabrooke. 2007. “Everyday IPE: Revealing Everyday Forms of Change in the World Economy.” In Everyday Politics of the World Economy, edited by J. M. Hobson and L. Seabrooke, 1–23. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Huelss, H. 2017. “After Decision-Making: The Operationalization of Norms in International Relations.” International Theory 9 (3): 381–409. doi:10.1017/S1752971917000069.

- Huizinga, J. 2017. Homo Ludens: Vom Ursprung Der Kultur im Spiel [Homo Ludens. The Origin of Culture in Playing]. Hamburg: Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag.

- Johnson, D. 2014. “Figuring Identity. Media Licensing and the Racialization of LEGO Bodies.” International Journal of Cultural Studies 17 (4): 307–325. doi:10.1177/1367877913496211.

- Kasser, T. 2016. “Materialistic Values and Goals.” Annual Review of Psychology 67: 489–514. doi:10.1146/annurev-psych-122414-033344.

- Kranke, M. 2014. “Which ‘C’ Are You Talking About? Critical Meets Cultural IPE.” Millennium: Journal of International Studies 42 (3): 897–907. doi:10.1177/0305829814529472.

- Kuckartz, U., and S. Rädiker. 2019. Analyzing Qualitative Data with MAXQDA: Text, Audio, and Video. Basel: Springer International Publishing.

- Lachney, M. 2014. “Building the Classroom.” In LEGO Studies: Examining the Building Blocks of a Transmedial Phenomenon, edited by M. Wolf, 166–188. New York: Routledge.

- Latour, B. 1991. “Technology Is Society Made Durable.” In A Sociology of Monsters: Essays on Power, Technology and Domination, edited by J. Law, 103–131. London: Routledge.

- Latour, B. 2009. “Where Are the Missing Masses? The Sociology of a Few Mundane Artifacts.” In Technology and Society: Building Our Sociotechnical Future, edited by D. G. Johnson, and J. Wetmore, 151–180. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Lauwaert, M. 2008. “Playing Outside the Box – On LEGO Toys and the Changing World of Construction Play.” History and Technology 24 (3): 221–237. doi:10.1080/07341510801900300.

- Lauwaert, M. 2009. The Place of Play. Toys and Digital Cultures. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

- Law, J., and J. Urry. 2004. “Enacting the Social.” Economy and Society 33 (3): 390–410. doi:10.1080/0308514042000225716.

- Lego. 2013. Ownership. Billund. Accessed 7 July 2020. https://www.lego.com/en-us/aboutus/lego-group/ownership

- Lego. 2015. “Awesome Sets from Shop.LEGO.com – LEGO City.” Accessed 7 July 2020. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5LMsbXXZ6UM

- Lego. 2016a. The Lego Brand. Billund. Accessed 7 July 2020. https://www.lego.com/en-us/aboutus/lego-group/the_lego_brand?ignorereferer=true

- Lego. 2016b. Planet Promise. Billund. Accessed 7 July 2020. https://www.lego.com/de-de/aboutus/lego-group/the_lego_brand/planet-promise

- Lego. 2017. Annual Report 2016. Billund. Accessed 7 July 2020. https://www.lego.com/cdn/cs/aboutus/assets/blt0b5f75205fb17080/Annual_Report_2016_ENG.pdf

- Lego. 2018a. “LEGO City Mini Movies Full Episodes Compilation. LEGO Animation Cartoons.” Accessed 7 July 2020. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_cWklSGyYyk

- Lego. 2018b. “See How It Was Made – The Amazing Life-Size LEGO Technic Version of the Bugatti Chiron.” Accessed 7 July 2020. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=n-RtJOfFlZU

- Lego. 2019a. The LEGO Group Responsibility Report 2018. Imagine a More Sustainable World. Billund. Accessed 7 July 2020. https://www.lego.com/campaign/responsibilityreport2018/-/media/Project/Campaigns-Grownups/Responsibility-Report-2018/Responsibility-Report-2018.pdf

- Lego. 2019b. The Lego Group: Annual Report 2018. Billund. Accessed 7 July 2020. https://www.lego.com/cdn/cs/aboutus/assets/blt02144956ae00afa1/Annual_Report_2018_ENG.pdf.

- Lego. 2020. The Lego Group – A Short Presentation. Billund. Accessed 7 July 2020. https://www.lego.com/cdn/cs/aboutus/assets/blt2278c7a21e58e900/LEGOCompanyProfile_2020.pdf

- Lindqvist, A.-K., M. Löf, A. Ek, and S. Rutberg. 2019. “Active School Transportation in Winter Conditions: Biking Together Is Warmer.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16 (2): 234. doi:10.3390/ijerph16020234.

- Lukács, G., J. Butler, and F. Benseler. 2011. Die Seele Und Die Formen. Essays [The Soul and Forms. Essays]. Bielefeld: Aisthesis-Verlag.

- Lukes, S. 1974. Power: A Radical View. Houndmiles: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Lukes, S. 2005. “Power and the Battle for Hearts and Minds.” Millennium: Journal of International Studies 33 (3): 477–493. doi:10.1177/03058298050330031201.

- Manderscheid, K. 2018. “From the Auto-Mobile to the Driven Subject?” Transfers 8 (1): 24–43. doi:10.3167/TRANS.2018.080104.

- Mertala, P., H. Karikoski, L. Tähtinen, and V.-M. Sarenius. 2016. “The Value of Toys: 6–8-Year-Old Children's Toy Preferences and the Functional Analysis of Popular Toys.” International Journal of Play 5 (1): 11–27. doi:10.1080/21594937.2016.1147291.

- Mullen, C., and G. Marsden. 2016. “Mobility Justice in Low Carbon Energy Transitions.” Energy Research & Social Science 18: 109–117. doi:10.1016/j.erss.2016.03.026.

- Mumby, D. 2016. “Organizing Beyond Organization. Branding, Discourse, and Communicative Capitalism.” Organization 23 (6): 884–907. doi:10.1177/1350508416631164.

- Newell, P. 2013. Globalization and the Environment: Capitalism, Ecology and Power. Cambridge: Polity.

- Nye, J. 2004. Soft Power: The Means to Success in World Politics. New York: Public Affairs.

- Orlikowski, W. J., and S. V. Scott. 2015. “Exploring Material-Discursive Practices.” Journal of Management Studies 52 (5): 697–705. doi:10.1111/joms.12114.

- Ozanne, L., and J. Ozanne. 2011. “A Child's Right to Play: The Social Construction of Civic Virtues in Toy Libraries.” Journal of Public Policy & Marketing 30 (2): 264–278. doi:10.1509/jppm.30.2.264.

- Paterson, M. 2007. Automobile Politics: Ecology and Cultural Political Economy. Cambridge, New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Pirrie, A. 2017. “The Lego Story: Remolding Education Policy and Practice.” Educational Review 69 (3): 271–284. doi:10.1080/00131911.2016.1207614.

- Princen, T. 2005. The Logic of Sufficiency. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Reckwitz, A. 2002. “Toward a Theory of Social Practices.” European Journal of Social Theory 5 (2): 243–263. doi:10.1177/13684310222225432.

- Robertson, D. 2013. Brick by Brick: How LEGO Rewrote the Rules of Innovation and Conquered the Global Toy Industry. New York: Crown Business.

- Schreier, M. 2012. Qualitative Content Analysis in Practice. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Schwartz-Shea, P., and D. Yanow. 2012. Interpretive Research Design: Concepts and Processes. New York: Routledge.

- Sheller, M. 2018. Mobility Justice: The Politics of Movement in the Age of Extremes. London, NY: Verso.

- Shields, S., Bruff, I. and H. Macartney, eds. 2011. Critical International Political Economy. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Shove, E., and G. Walker. 2010. “Governing Transitions in the Sustainability of Everyday Life.” Research Policy 39 (4): 471–476. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2010.01.019.

- Stanley, L. 2014. ‘ “We're Reaping What We Sowed’: Everyday Crisis Narratives and Acquiescence to the Age of Austerity.” New Political Economy 19 (6): 895–917. doi:10.1080/13563467.2013.861412.

- Statista. 2017. Dossier Toy Industry. Accessed 7 July 2020. https://www.statista.com/study/10808/toy-industry-statista-dossier/.

- Stockmann, N., and A. Graf. 2019. “Nachhaltige Urbane Mobilität Von Morgen Zwischen Reproduktion Und Dekonstruktion Von Normen [Sustainable Urban Mobility between Reproduction and Deconstruction of Norms].” Amosinternational 13 (3): 10–16.

- Sutton-Smith, B. 1997. The Ambiguity of Play. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- The Lego Foundation. 2018. How We Work. Billund. Accessed 7 July 2020 https://www.legofoundation.com/en/about-us/how-we-work/