Abstract

The discourse on sustainability transformations moves beyond accommodationist, reformist framings of sustainability to imply a radical, systemic shift toward new sustainable trajectories. While democracy has been accorded a central role in sustainability governance of most kinds, this emphasis on systemic transformation, and the new context of existential ecological threat, prompt a reconsideration of the kind of democracy that would provide a political foundation for sustainability. Arguing that the politics of sustainability transformation inherently demand democratization – for both disruption (of established power structures) and normativity (in relation to the negotiated meaning of sustainability) – this article explores the potential of deliberation in particular to create these foundations. I contend that while the recent policy-oriented practice of deliberation has itself become overly accommodationist, the concept can equally encompass a more disruptive, yet still normatively driven form, the time for which might be just right.

Introduction

Issues such as pollution, resource scarcities, biodiversity loss, and even climate change are often framed as environmental “problems.” Recognition of unsustainability, on the other hand, goes beyond isolated, solvable problems. The need for environmental sustainability is not just a fashionable new way to describe environmental problems; it goes beyond these characterizations by implying that something more existential has come to be at stake. As such, unsustainability innately implies a need for transformation at a deeper level than that required to address environmental issues framed as discrete “problems.” Whereas problems can be met with solutions within the given system they afflict, an unsustainable system is itself in need of change—as it is, it can no longer be sustained.

What, then, is the source of unsustainability at the level of the current “system” of society? This article builds on the long pedigree of critical thought in environmental politics that has most prominently been articulated as “limits to growth”: the view that unsustainability is systematically produced by the growth-dependent socioeconomic model of liberal-capitalist societies (Meadows et al. Citation1974). The developmental patterns this ideology imposes on societies do not just produce some environmental externalities, but fundamentally come up against the limits set by a finite ecosystem and resource base (Jackson Citation2017). Thus a process of moving from unsustainability to sustainability is a transformation in the sense of a comprehensive, systemic shift in the society’s values, beliefs, and developmental patterns—away from the growth economy—as opposed to only smaller-scale policy change (Olsson et al. Citation2014).

Indeed, the environmental problems of the past century have become so acute as to constitute an urgent crisis of unsustainability. Climate change has become climate emergency, feared to threaten civilization itself (Oreskes and Conway Citation2014). The public discussion has shifted from a marginal environmentalist discourse toward concrete fears widely felt in the mainstream. As a result, a scholarly discourse has evolved to examine the prospect and urgency of a sustainability transformation in this sense (Weinstein et al. Citation2013; Olsson et al. Citation2014; Brand and Wissen Citation2016). How can societies engender such a systemic shift? What are its political preconditions—and in particular, as this special issue asks, the role of democracy?

This contribution engages with the latest discourses on sustainability transformations to sketch a new perspective on the role of deliberation in the governance of sustainability that fits this new context. Despite its many different and hence often unclear meanings, sustainability is an important discourse for two reasons. On one hand, as already stated, it emphasizes the systemic and existential nature of the crisis. On the other, sustainability is not the same as survival: By going beyond the latter, it incorporates normative concern for justice and well-being (Hammond Citation2020). Sustainability transformations beyond the growth economy must thus tackle the social as well as the ecological crises stemming from the liberal-capitalist model; they respond to concrete ecological threats as much as they articulate and are oriented toward new visions of prosperity (Jackson Citation2017).

The normativity and scale of this transformation make it a highly political, as opposed to a technical, challenge. Societies need to craft altogether new visions for the future, but therein come up against powerful interests in the status quo. The beneficiaries of liberal capitalism, such as corporations, are fashioning themselves as the crucial change agents for sustainability, promulgating the myth of a technology- and market innovation-driven form of sustainability that retains and celebrates, not abdicates, the neoliberal growth economy (Wright and Nyberg Citation2014). From sustainable development to ecological modernization and green growth, this discourse has been so successful as to largely replace the earlier Limits to Growth paradigm in the political arena (Mert Citation2009). The upshot, however, have been “environmental states” with a good track record of responding to environmental problems that threaten human well-being within the context of modern capitalist welfare states, but hitting a powerful glass ceiling when it comes to the fundamental systemic transformation required for actual biophysical sustainability (Hausknost Citation2020). In other words, the unsustainability of the neoliberal system has come to permeate both its political and its economic structures, which have (co-)evolved to benefit the same elites in society, and to continue to perpetuate this status quo (Holcombe Citation2018). In terms of democracy, for instance, neoliberal principles are reflected in how liberal democracy sees vote choice as a matter of the competing material interests of individual citizens. The neoliberal rationality and scheme of valuation have become the framework that contains—and constrains—even our political culture and democratic imagination (Brown Citation2015). The very context in which decision making about sustainability takes place is thus structurally opposed to transformation.

To be sure, transformation is hard to actualize in general, in that is requires an entire society to reorient its culture and life stories toward a new set of norms. But insofar as transformation-hindering political structures are (consciously or unconsciously) cultivated by political and economic elites who benefit from the status quo, this is also an issue of power: an exertion of the “modern” power of ideological discourse, over what is taken for granted in society as “normal” or how things really are (White Citation1986, 420‒1). Cultivating ideology—a false consciousness which nevertheless comes to be seen as normal, and thus stabilizes the social conditions of the status quo—is a particularly potent form of power in that its impact on people’s thoughts and behaviors is not directly visible and thus contestable. Its force rather lies precisely in removing certain conditions from the political space of contestation by making them appear natural or without alternative (Flood Citation2002; Rosen Citation1996). Insofar as ideological power, entrenched in the basic politico-economic structures (such as the current form of liberal democracy), hinders systemic transformations necessary for sustainability, a politics of sustainability transformation cannot be produced by this political system as it is. Rather, the transformative impulse must then emanate from the outside (Machin Citation2020), and encompass the dimension of extant power structures and social relationships (Kuenkel Citation2019, 6).

This is what makes democracy central to sustainability transformations. The conventional managerial and economic perspectives that have dominated the discourse so far—those “assuming that change can be managed and planned and that the change needed is a linear process” (Kuenkel Citation2019, 9; see also Etzion et al. Citation2017, 168)—fail to integrate the dimension of power into the issue of societal transformation. In light of the roles of ideological power and vested interests in foreclosing or driving the direction of social change, democratization must be seen as an inherent dimension of sustainability. Implying a shift in the balance of power away from established elites and toward those at the margins of the extant system, democratization in itself begins a process of structural transformation. Deliberative democracy has been a prominent approach to democratization in this sense. In order to approach the ideal of “deliberation” as a (hypothetical) domination-free form of discourse, it must fundamentally extend voice to those who are at present structurally marginalized from decision making by more powerful others. It also promises to uncover and challenge the otherwise hidden power of ideological distortion (Dryzek Citation2000).Footnote1

Indeed, deliberative approaches have long been seen as key to sound environmental policy making and thus sustainability (e.g., Smith Citation2003; Baber and Bartlett Citation2005; Bäckstrand et al. Citation2010). Yet little attention has thus far been paid to how this translates to the context of sustainability transformations. So far, where attention has been paid to deliberation, this has itself largely remained within the boundaries of the prevailing liberal system. For example, democratization in sustainability governance is often portrayed as the inclusion of stakeholders beyond traditional centralized governance (e.g., Bäckstrand Citation2006a). Yet who is regarded as an important stakeholder—typically prominently featuring pertinent business interests—is itself influenced by perceived social standing (i.e., power) within the status quo. While deliberative democracy has spawned vibrant experimentation with new forums for involving lay citizens (that is, citizens with no specialist expertise, formal role, or prior engagement with the issues at hand) in environmental governance (e.g., Niemeyer Citation2007; Smith Citation2003), these advancements have been accused of having similarly submitted to the liberal status quo and its associated “ways of doing things.”

In this article, I develop a new perspective on the role of democratic deliberation in the specific context of fundamental, systemic sustainability transformations. I ask how deliberation can support a sustainability transformation if the latter is understood as requiring a fundamental shift in the entire developmental paradigm that modern societies are oriented toward, and thus also in entrenched power structures that uphold the prevailing one. Rather than as an instrumental advisory mechanism to help bring about a particular set of outcomes, I argue this requires deliberation as a critical and disruptive discourse in society at large. Disruption is often seen as the métier of radical or agonistic democracy; yet I show a critical form of deliberation is not only equally plausible, but in the end more clearly aligned with the open reflexivity—a society’s ability to open-mindedly rethink its course of development and undergo deliberate transformation—that is needed for sustainability (Hammond Citation2020).

The argument proceeds as follows. The following section develops a perspective of sustainability transformation as necessarily requiring both democracy and the disruption of extant structures and processes of liberal-capitalist politics. The subsequent section evaluates the role specifically of critical deliberation in sustainability governance from that angle. Having found the current practice wanting in critical potential, the next section contrasts the conventional policy-oriented practice with a new type of disruptive deliberation. The final section provides a concluding discussion.

The scope of sustainability transformations

The meaning of “sustainability” is contested and has varied significantly over time. A key dividing line has been the question of the relationship between sustainability and economic growth. Where sustainability is taken to necessitate “radical” or “systemic” change, this implies the need to move beyond a mode of society based on growth. This sustainability discourse goes back to the recognition of “limits to growth” (Meadows et al. Citation1974) and the finiteness of the Earth system and thus a need to orientate economic production to a “steady state” instead (Daly Citation1991). Yet, it is less radical interpretations that dominate the political agenda to the present day. Specifically, the Brundtland conception of “sustainable development” (WCED Citation1987) and the United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals (United Nations Citation2015)—despite the latter mentioning “transformation” in its title—are committed to improving, not replacing, the functioning of the extant growth-based developmental model. The aim is greater justice as well as the “ecological modernization” of the growth-based economy and society (Spaargaren and Mol Citation1992). This section explores where the more recent concept of sustainability transformation sits in relation to this existing field of discourse.

On one hand, the struggle for ideological sovereignty over the sustainability discourse can be expected to continue in relation to sustainability transformations: what needs to be transformed depends on the vision of sustainability. On the other hand, however, the discourse on sustainability transformation starts from a new premise altogether. Emerging in the context of climate emergency and generally worsening, not improving, environmental conditions, sustainability transformation replaces the accommodationist sustainable development discourse with an implied insistence on far-reaching, systemic social change of modern societies. Sustainability is no longer a “merely” normative desideratum, but an existential question concerning the survival of the human species and civilization. This has created a new momentum for radical change beyond traditionally radical environmentalist circles. The concepts of sustainability transformation and transition imply radical, systemic change by alluding to a shift or movement—transformation/transition—from one state to another, as opposed to applying sustainability thinking to a given system on its own. Such a transformation requires larger thinking across all subfields and subsystems of society, and ultimately consists in an “ideological transition” more so than mere innovation driven by extant patterns of thought, which implicitly seek to optimize, but thus also reproduce, the unsustainable status quo (Olsson et al. Citation2014; Weinstein et al. Citation2013).

This holistic view of the sustainability challenge highlights the complicity of the political and economic systems in current unsustainability. Concrete environmental problems certainly must be addressed in the here and now; and addressing them requires the expert input, efficient policy making, and innovative technologies the neoliberal system is good at producing. Insofar as this system structurally reproduces unsustainable patterns, however, these are not sufficient for societies to become sustainable. Structurally unsustainable patterns include the way in which the society’s orientation toward economic profit, not holistic prosperity, manifests even in political and policy structures, such as the form of democracy or the use of economistic cost-benefit analysis in decision-making. In addition to the current urgent agendas in environmental policy making, there is a need also for “radical, systemic shifts in [these] values and beliefs [and] patterns of social behavior” (Olsson et al. Citation2014, 1).

Such radical change presents a much greater political challenge than approaches such as ecological modernization or sustainable development, which stay within the growth-oriented paradigm. On this basis, democratization, too, plays a different role in this new sustainability discourse than it did in extant approaches (as the next section elaborates in more detail). On one hand, the reinterpretation of the original sustainability discourse, from one centered around limits toward the still-dominant notion of sustainable development, can be assumed to be no accident, but a manifestation of the way in which discursive power intertwines with the ecological (un)sustainability of the society. The way in which the liberal economic ideology constrains the democracy and inclusivity of its politics as well (Brown Citation2015; Holcombe Citation2018), is thus in itself a limitation of these societies’ sustainability (Hammond Citation2020). Against this, democratization is needed as a shift in power rather than merely new instances of participation within the given balance of power. By giving new voice to those not currently in positions of discursive influence (say, through an otherwise marginalized perspective emerging into the societal discourse through new democratic channels), democratization is needed to shift the overall discourse toward a fundamentally different framing. A transformation—beyond mere innovation—must mean a loss for those who benefit from the status quo (say, toward a new social hierarchy less divided based on differences in material wealth), and thus cannot emerge out of the liberal-democratic system structurally biased toward maximizing (these elites’) material interests. On the other hand, the need for an ideological transition opens up a new discursive field that must be filled with concrete meaning. Sustainability can only be a trajectory toward prosperity for all those to whom it applies—that is, all—if its meaning is negotiated democratically. Inasmuch as extant forms of democracy are themselves part of the structures that reinforce the capitalist status quo, democracy itself must be freed from these constraints and democratized (Hammond and Smith Citation2017). Focusing on deliberation, as one prominent candidate for democratization in this context, the remainder of this article discusses how its original critical potential can be more effectively harnessed so as to meet the radical implications not just of any sustainability-oriented governance, but sustainability transformation.

Deliberation for transformation?

Deliberative democracy has a long pedigree of being interwoven with the sustainability discourse. Deliberation goes beyond other forms of citizen participation, such as consultations, by aspiring to a norm of fully inclusive, reasoned, fair, and open public communication that is aimed at a common good and eschews the domination inherent in interest-based negotiation and bargaining (Dryzek Citation2000). Though previously criticized as an exclusionary communicative standard, it is now long accepted that its normative goal of curtailing elite domination means deliberation invites contestation by whoever is affected by an act of authority, in whatever form of communication that is effective, and has no requirement of ending in consensus (Curato et al. Citation2017, 30‒31). This ideal certainly promises to channel the critical voices of those demanding a deeper transformation into the otherwise narrow, interest-based sustainability discourse. But like sustainability, the concept of deliberation, too, has evolved into a range of interpretations. This section unpacks these interpretations to explore the form of deliberation that is required for sustainability transformations in particular.

The rise of the sustainable development paradigm brought with it a concern for democratic participation in sustainability governance that was seen as integral to its very essence. The United Nation’s Agenda 21 on sustainable development states “One of the most fundamental prerequisites for the achievement of sustainable development is broad public participation in decision-making,” suggesting specifically that “the need for new forms of participation has emerged” (United Nations Citation1992, 23.2). As normative democratic theory took a “deliberative turn” around the same time, deliberation soon rose to importance in this context (Bäckstrand et al. Citation2010, 3). In light of the limitations of liberal democracy—constrained by short-term electoral cycles and the primacy of economic concern, and threatened by growing voices in support of technocratic management of the climate crisis—deliberation is seen as a promising new instrument that can enhance the legitimacy of governance in difficult, complex areas such as environmental sustainability, but that also “gets things done” more effectively than conventional command-and-control governance (Bäckstrand et al. Citation2010).

Deliberative citizen engagement can play such a supportive role in environmental governance by mediating between different stakeholders’ interests, enhancing knowledge and awareness of environmental issues, and increasing public acceptance for new policies (Bäckstrand et al. Citation2010; Baber and Bartlett Citation2005). This role of deliberation fits with the view in deliberative democratic theory that it is orchestrated, institutional governance innovations—known collectively as “mini-publics”—that achieve meaningful democratic renewal at the same time as being very useful to policy makers (Goodin and Dryzek Citation2006; Grönlund et al. Citation2014). The function of deliberation of bringing together a range of perspectives fits neatly onto the proven usefulness of stakeholder governance in sustainability; and its focus on mediating rather than bargaining between positions lends itself to as value-laden a discourse as that on human-nature relationships (Bäckstrand Citation2006b; Bäckstrand et al. Citation2010; Smith Citation2003). Although deliberative discourse must always be open—it cannot guarantee environmentally conscious outcomes—the presumption in this literature has been that such fair, reflective communication is conducive to, and needed for, sustainability (Niemeyer Citation2014; Dryzek Citation2016).

In the context of systemic sustainability transformations, however, the picture becomes more complex. In this merely instrumental capacity, deliberation can itself be used as a system-reinforcing tool. As a policy tool at the disposal of authorities, it becomes assimilated to the political system in which it is applied (Setälä and Smith Citation2018), and accordingly becomes useful to the status quo as to ultimately reinforce it (Böker Citation2017). As such democratic initiatives were increasingly picked up and driven by authorities (Warren Citation2009), the purported democratization, far from facilitating transformation, may in fact already have become complicit in cementing a governance of unsustainability that merely simulates participation and democratization, and ultimately instrumentalizes these practices to sustain the unsustainable, neoliberal status quo (Blühdorn Citation2013; Mert Citation2019). In this sense, the much-celebrated role of democratization, including deliberation, in sustainability governance may well have supported some version of sustainability governance, but undermines the kind of engagement needed for sustainability transformations.

However, this is but one form of deliberation among possible others. The recent practice notwithstanding, the concept of deliberation is in significant part rooted in critical theory, challenging nothing less than liberalism itself (Dryzek Citation1990, Citation2000). It was devised with the ambition that the new “communicative rationality” it realizes would be what could resist the hegemonic liberal-instrumental rationality entrenched within dominant political and economic institutions, and enable the “discursive and critical reconstruction” of a different kind of “lifeworld” (Dryzek Citation1990, 12). As part of its own oscillation between instrumental (system-supporting) and critical (system-rupturing) orientations in the literature, then, deliberation has also been advocated as fulfilling more distinctly open and critical functions (see, e.g., Ward et al. Citation2003; Böker and Elstub Citation2015; Böker Citation2017). In the environmental context, for example, deliberative democracy has been argued to revolutionize the political discourse to the extent of including the views of animals, trees, and the Earth system as a whole in the discussion (Dryzek Citation2000, Citation2017; Dryzek and Pickering Citation2019). Deliberation in the broad public sphere can create a space in which people’s fears, hopes, cultural norms, and new visions for alternative societal futures can be articulated (Hammond Citation2020). System-critical movements such as Extinction Rebellion call for deliberation as a forum for moving the debate on sustainability into a more radical direction, as a space unconstrained by the limitations of the narrow policy discourse (Extinction Rebellion Citation2019).Footnote2

Conceptually, then, deliberation in fact aligns with both approaches to sustainability. Deliberative techniques can be put to use in the context of stakeholder governance toward managerial, reformist, “win-win”-oriented sustainable development, as much as they can also provide concrete spaces precisely for the articulation of an alternative, radical sustainability discourse. Deliberation can be seen as, and made into, either an accommodating or a transformative practice. Thus, the question is in what form deliberation serves, rather than hinders, sustainability transformations. Based on its theoretical promise, deliberation is needed as a form of public discourse that is critical enough to emancipate citizens from ideological domination that perpetuates the status quo, but that also channels a constructive, inclusive public discussion from which to build normative alternatives. However, this promise comes up against the danger that the extant practice of deliberation is proving insufficiently critical to the point of inadvertently reinforcing the unsustainable status quo in itself. Thus, the urgent need for a sustainability transformation is a prompt to rethink this practice and explore how deliberation might take a new shape.

A new type of deliberation in the context of sustainability transformations

What would a system-critical form of deliberation look like in practice? The following discussion sketches a possible new type of deliberation—disruptive deliberation—inspired by the uptake of deliberation by radical environmental movements. The point is not to claim that this type of deliberation does or even can exist and be effective, or that any other deliberation is necessarily problematic. Rather, it is to engage in conceptual imagination so as to keep the discourse on deliberation itself dynamic and open, resisting its own accommodation into the neoliberal status quo.

In light of the above discussion, bottom-up critique is crucial in the context of sustainability transformations, for the role of democracy here relates to the element of a necessary, but always averted disruption of unsustainable power relations. Against deliberation’s already well-documented constructive functions (e.g., Goodin and Dryzek Citation2006; Grönlund et al. Citation2014), what must now gain precedence is its critical function to channel vibrant contestation of dominant societal discourses and practices within democratic spaces. This occurs in a context, however, of deliberation itself being made into an instrument precisely to avert the disruptive critique it has the potential to create. Thus it is important that functions of deliberation that are often touted in the same breath in environmental governance, such as its capacity to enhance knowledge and compliance as well as its ability to challenge the powerful interests vested in the unsustainable status quo, are more carefully distinguished. Although concrete instances of deliberation will always fall somewhere along a spectrum between constructiveness and critique, juxtaposing the two respective “ideal types”—constructive versus disruptive deliberation—can help with this, thus allowing for more cognizant and critical evaluation of what actually unfolds in practice.

It might come as a surprise that deliberation should be the focus for this in the first place. The disruptive element of democracy is generally associated with the protest and activism hailed by agonist or radical democrats. For example, Amanda Machin (Citation2020) is critical of deliberative approaches to sustainability governance that prioritize dispassionate judgment and counteract rather than spark political mobilization at a large scale. In contrast, she writes that agonistic confrontation “allow[s] the radical disruption of unsustainable institutions and conventions and the divergence onto a different path” (Machin Citation2020, 17). Based on the objective of agonist theories of democracy “to struggle against domination, dependence and arbitrary forms of power” (Wenman Citation2013, 5), agonistic democrats call for those forms of democratic discourse and interventions that reconfigure prevailing structures and relations of power—including those that prevent radical sustainability transformations (Machin Citation2020, 17).

Based on its critical theoretical origins, however, deliberation too comprises a disruptive component wherever this is needed to counteract domination—and more. Although it has become associated with the specific institutional innovations known as mini-publics (such as citizens’ assemblies) deliberation also encompasses wider discursive practices in the public sphere, through which the otherwise oppressed or marginalized empower themselves against unjustified power relations (Curato et al. Citation2018). In the critical theory tradition outlined above, the essence of deliberation is communication that induces reflection in a non-coercive fashion, which “rules out domination via the exercise of power, manipulation, indoctrination, propaganda, deception, expressions of mere self-interest, threats (of the sort that characterize bargaining), and attempts to impose ideological conformity” (Dryzek Citation2000, 2). Based on this definition, deliberation as a practice must be characterized not as the tightly defined, rational, and dispassionate ideal it has become portrayed as (and which mini-publics typically aspire to), but rather as whatever communicative engagement that maximizes inclusive, non-coercive reflexivity, for this in turn best curbs domination. It further implies the maximum degree of critical contestation still compatible with not tipping the balance toward exercising its own illegitimate, coercive power (Curato et al. Citation2018). Where agonists place their emphasis on the disruption of hegemony, deliberation in this original, critical conception likewise seeks to disrupt domination, but with the overarching aim not of winning an ideological fight, but of thereby inducing reflection as a good in itself. Disruptive deliberation thus incorporates those elements of agonistic democracy—specifically, the disruption of hegemonic domination—that actually overlap with deliberative democracy (see Knops Citation2007), but only insofar as this does not jeopardize reflexivity (for example, through the establishment of a counter-hegemony, as opposed to a sociopolitical sphere that is as hegemony-free as possible). Whereas agonism could be directed to a range of causes, this orientation toward reflexivity makes deliberative democracy more innately aligned with the continuous processes of rethinking and crafting the future that sustainability demands.

Inasmuch as sustainability transformation requires both radical disruption of the power balance in the (unsustainable) status quo and inclusive normative visions (of new sustainable trajectories), this conception of deliberation provides a theoretical norm that matches this governance challenge. Yet in practice, conceptions of deliberation have become successful, even mainstream, precisely when the literature shifted away from its original critical ambition. As the context of sustainability transformation reveals an overly accommodating practice as insufficient, it poses a new challenge to deliberative governance innovation. Amidst the large-scale transformation of society that lies ahead, deliberation is needed in both its critical and its constructive functions.

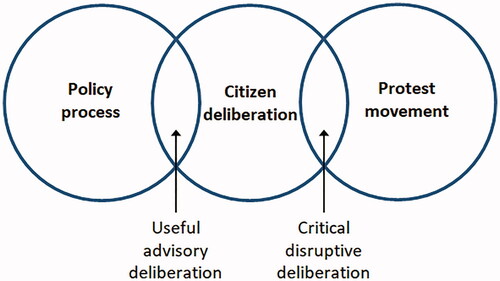

In this light, it is perhaps no coincidence that a new type of deliberative practice appears to be emerging in the realm of environmentalism (Extinction Rebellion Citation2019). It is yet to materialize as a concrete practice, but even the idea already suggests new ways of looking at deliberation and its place in the political landscape.Footnote3 Thus far, although deliberative democracy is widely recognized as incorporating both constructive and critical dimensions, the practice of deliberative mini-publics has tended toward the system-supporting, constructive side by marrying citizen engagement with the representativeness, professionalism, and efficiency of the conventional policy process. The need for systemic transformation has prompted renewed attention to the other end of the spectrum: its disruptive, critical side. This suggests that there might be a second type: Rather than as a marriage of the lay-citizen perspective with the policy process, deliberation might equally be thought of as marrying the lay-citizen perspective with disruptive protest movements in the public sphere. Even though Extinction Rebellion’s approach to citizen assemblies appears to want to replicate extant practice rather than innovating something different (Extinction Rebellion Citation2019), the very fact that a movement is initiating a deliberative process prompts reflection on how this might differ from deliberation under the auspices of formal political authorities, and whether it would constitute a different type of deliberation altogether. I will argue that a new deliberative practice is indeed promising for sustainability transformations—yet to achieve broad and transformative societal impact, it must go beyond the discrete mini-publics seen so far ().

The field of deliberative democratic governance innovation has become a leading area of political theory research because of the real-world impact its new theorizations have produced (Pateman Citation2012, 7; Curato et al. Citation2017). Mini-publics have been successfully used to supplement policy processes in a number of areas and around the world, with the highest-profile examples being, for instance, the British Columbia Citizens’ Assembly on Electoral Reform in 2004 (Warren and Pearse Citation2008) and the global World Wide Views citizen consultation on climate change in 2009 (Bedsted and Klüver Citation2009). However, much of this impact was achieved because theorists partnered with the authorities that sponsored and retained control over these deliberative processes. The ability of these initiatives to feed into real-world politics has given the research area of deliberative democracy great purchase and impact, but there are reasons to believe this has also shaped the meaning of deliberation in turn. Conventional deliberation in mini-publics has become policy-oriented in that forums are mostly initiated and sponsored by authorities, and run by a “large industry of consultants and democratic process entrepreneurs” (Warren Citation2009, 7). They are used as discrete additions to the policy process, in a supportive function; and with authorities in control of the extent to which their findings are actually taken up. Accordingly, the capacity of these initiatives to challenge rather than support is limited (Setälä and Smith Citation2018; Böker Citation2017).

What has moved into the background is the degree to which this policy orientation is a departure from the original critical deliberative theory, which might have led to a different form of practical instantiation (Böker Citation2017). Its recent uptake as a practice precisely by a system-critical, disruptive movement now overcomes the “critical in theory—constructive in practice” divide, prompting the question how a critical, intently disruptive deliberative practice would differ from extant innovations. Although no concrete practice will ever fall into some neat conceptual category, I want to respond to this prompt and conceptually contrast policy-oriented deliberation with an opposing type of disruptive deliberation, as a way of producing new insight into the role that deliberation can play in the radical transformations required for sustainability.

In contrast with the policy-oriented type, disruptive deliberation would be initiated and owned not by authorities, but by protesting citizens. As a result, its agenda would arise not out of a given hierarchy, but precisely out of a realm with no formal authority. Of course, not all movements are necessarily horizontally and democratically organized. Yet one to which the second dimension of deliberation already applies—a commitment to normativity, fairness, inclusiveness, and democracy as opposed to mere power play, illiberalism, or even violence—has no other prior ordering of authority or voice, and must thus (as an ideal type) be presumed to be horizontally ordered. Deliberation would therefore not be used as a tool for answering an authority’s wish for input on a specific question or issue, but rather as itself an agenda-setting process that works from the bottom up. Rather than as a discrete tool to support a specific policy-making process, deliberative events could be used with the goal to spark as broad and as continuous a societal discussion as possible (see Ward et al. Citation2003).

In the case of Extinction Rebellion, elements of this type are discernible in that the planned citizens’ assembly is on the topic of climate and ecological justice—a clear normative, as well as open-ended, concern (Extinction Rebellion Citation2019, 5); and it is specifically envisaged to allow for more “transformative” and “bold” action than the formal political process is able to generate (16). However, the citizens’ assembly that is outlined follows the same design as standard policy-oriented mini-publics, including a set “expert” panels, a coordinating group (albeit in this case made up of citizens as opposed to authorities), a specifically set question to be addressed, and an orientation toward “feasible alternative policies” (8‒11).

develops a number of further juxtapositions that suggest a different way forward. Of course, movements do seek concrete policy change, and fight for very specific issues (such as the exact year the government commits to achieving net zero carbon emissions). But with this comes the risk of becoming just another player in the established policy process, with an associated need to play by the very rules rigged in favor of perpetuating the status quo the movement is fighting to change. It is possible to envision a novel form of deliberation that harnesses the unique features of a broad protest movement—to be informally organized, fluid, radical, and foremost oriented toward altering the terms of politics itself, or the way a certain issue is perceived in society—more than those of a policy actor. This perspective suggests deliberation might ultimately play a more disruptive role if it remains oriented toward sparking discussion rather than policy decisions; is open-ended rather than goal-oriented; takes the form of a continuous societal debate that directs the broad discourse rather than that of a specific tool used to supplement the policy process that otherwise retains the upper hand; and thus evolve in a much messier (in the sense of not tightly controlled and facilitated), but more organic and bottom-up manner within a plethora of social spaces and forms.Footnote4 There might not be the perfect representativeness of stratified random sampling, but instead a greater proportion of the population might be inspired to engage with radical political debate and join discussion groups or activist movements. A concrete policy at hand may not be formally shaped by the movement, but instead an entire new framing of society and its politics may slowly gain hold, and thus shape all policy making within it. This way to look at deliberation takes inspiration from approaches to democratization as an ethos or culture more than an institutional innovation (e.g., White Citation2017; Böker Citation2017), re-situating deliberation within the informal public sphere in which it can take a number of forms in practice, including informal talk in different settings, a range of participatory activities, new approaches to engaging with representatives and the formal political process, and activism of different kinds.

Table 1. Constructive versus disruptive deliberation.

In short, this form of deliberation would forfeit policy effectiveness for the sake of retaining the critical contestation and status-quo disruption of a protest movement, rather than vice versa. The point I want to make here is not about one ideal type being better or truer than the other. Rather, I want to stress that inasmuch as deliberation as a theoretical concept combines both dimensions, the messier, disruptive type I have outlined is not a lesser form of deliberation, but, rather, a different form. In the context of the fundamental societal transformation that is unfolding, disruption is as socially needed as accommodation and mediation are in stable times; and its marriage with the deliberative norms of fairness, inclusiveness, openness, and democracy means, ideally, that a balance is still struck between chaos and purpose; between disrupting the present and building something new. It is an orientation toward these norms that also defines even this wider range of practical manifestations as “deliberation” as opposed to other political practices and forms of communication.

It remains to be seen how the practice of deliberation will evolve further as movements such as Extinction Rebellion indeed call for instruments such as citizens’ assemblies in the context of sustainability transformations. One way of making deliberation relevant to the context of radical transformation is to think of it as an altogether different practice than that associated with mini-publics so far. Given its aims and identity, deliberation in the service of transformation cannot be contained within the system-sanctioned and system-supporting function of conventional mini-publics. In the service of system transformation through an inclusive democratic movement, deliberation necessarily becomes a messier practice at a larger scale. As a result, it may look less “ideal” in the sense of representativeness, fairness, and strict equality of participants; yet as long as it remains self-reflexively oriented toward these norms as the ideal to aspire to in the name of legitimacy (and thus being clearly distinguished from other forms of disruption, such as political violence), this is not a loss of deliberation, but a mere prioritization of its critical dimension over its representative one. Disruptive deliberation in this sense may still involve the organization of concrete mini-publics, but the deliberation these generate must ultimately be thought of as transcending the one specific forum, and employing other markers of success than professionalism and formal policy impact. In serving societal transformation, its function is to spark new debates rather than to resolve them, and to gain followers not of a particular standpoint, but of a broad commitment to the normativity and inclusiveness of a sustainability vision. Such a form of deliberation would stand a better chance than professionally run, authority-sanctioned mini-publics (such as the Climate Assembly in the UK) to spark the genuinely bottom-up, critical, open, and diverse discursive engagement that is needed for “communicative rationality” to challenge the otherwise taken-for-granted framings of the elite-led, transformation-hindering discourse, and thus shift discursive power away from this elite and toward alternative framings of sustainability instead.

Conclusion

The crisis of unsustainability has far-reaching implications for social life, including democracy. The need for a profound and holistic transformation of all dimensions of industrial societies presents a never-before-seen political challenge: how can these societies overcome their most entrenched structures, as well as building something radically new? I have argued in this article that rather than a cause for abandoning the virtues of justice and normativity associated with extant sustainability discourses, the context of sustainability transformation is a prompt to bring these values more firmly into the picture and to re-think the way in which key concepts have evolved. Democratic deliberation is one of these concepts. Like sustainability, deliberation has been thought of in more or less radical ways; like transformation, it can ultimately be used to reinforce or to overturn a given status quo. The fact that deliberation is indeed being taken up by those working toward radical transformation, such as environmental protest movements, shows there is scope for re-thinking it as a practice and giving it the shape in which it best supports a normatively driven sustainability transformation.

This is a transformation that radically disrupts the unsustainable status quo while remaining oriented toward visions of justice and prosperity. Whereas conventional deliberation, associated with most types of mini-publics, has tended too far toward supporting as opposed to disrupting existing structures, I have shown that its practice can be reconceptualized so as to fruitfully combine these two dimensions. Disruptive deliberation transforms society by being critical and bottom-up, broad and open-ended; but it therein remains committed to inclusiveness, fairness, and democratic reflexivity. Deliberative practice may well be due another wave of vibrant experimentation very soon.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Ariane Götz, Boris Gotchev, and Ina Richter for the invitation to contribute to this special issue and for helpful comments on earlier versions of this article. Many thanks also to Amanda Machin for helpful comments on an earlier draft.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes

1 I am using the term deliberation as a normative concept; an ideal of democratic communication aspiring to which in political actors’ (citizens as much as politicians, organizations, and authorities) general behavior can bring about deliberative democracy at the level of the society and the political system as a whole.

2 Extinction Rebellion is an interesting case because it is the first to link environmental activism to the demand of a deliberative citizens’ assembly. This democratic commitment notwithstanding, however, co-founder Roger Hallam has used language similar to that of far-right activists and the camp traditionally associated with renouncing democracy in the face of as apocalyptic an emergency as the environmental crisis. In an interview with the German newspaper Die Zeit, Hallam relativized the Holocaust as “just another fuckery in human history” (Knuth Citation2019). In response, the respective heads of the movement in both Germany and the UK have explicitly distanced themselves and their branches of the movement from Hallam. In the end, the movement’s credibility and relationship with democracy will depend on its developing independently and in bottom-up fashion away from its original founders, as opposed to remaining associated with them as its central figureheads.

3 While the UK government has indeed orchestrated a citizens’ assembly, this is not taking place under the auspices of Extinction Rebellion, and is on the topic of how to achieve the UK’s target of net-zero carbon emissions by 2050 as opposed to Extinction Rebellion’s demand for an assembly on ecological and climate justice.

4 In that sense, this type of deliberation partly aligns with the more recent systemic perspective on deliberative democracy (Parkinson and Mansbridge Citation2012); but the focus is not on a functional division of the deliberative labor between different institutions or social spaces, but rather on an organic and bottom-up evolution of deliberation within the public sphere.

References

- Baber, W., and R. Bartlett. 2005. Deliberative Environmental Politics. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Bäckstrand, K. 2006a. “Democratizing Global Environmental Governance? Stakeholder Democracy after the World Summit on Sustainable Development.” European Journal of International Relations 12 (4): 467–498. doi:10.1177/1354066106069321.

- Bäckstrand, K. 2006b. “Multi-Stakeholder Partnerships for Sustainable Development: Rethinking Legitimacy, Accountability and Effectiveness.” European Environment 16 (5): 290–306. doi:10.1002/eet.425.

- Bäckstrand, K., J. Khan, A. Kronsell, and E. Lövbrand. 2010. “The Promise of New Modes of Environmental Governance.” In Environmental Politics and Deliberative Democracy: Examining the Promise of New Modes of Governance, edited by K. Bäckstrand, J. Khan, A. Kronsell, and E. Lövbrand, 3–27. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Bedsted, B., and L. Klüver. 2009. WWViews on Global Warming: From the World’s Citizens to the Climate Policy-Makers Policy Report. Copenhagen: Danish Board of Technology.

- Blühdorn, I. 2013. “The Governance of Unsustainability: Ecology and Democracy after the Post-Democratic Turn.” Environmental Politics 22 (1): 16–36. doi:10.1080/09644016.2013.755005.

- Böker, M. 2017. “Justification, Critique and Deliberative Legitimacy: The Limits of Mini-Publics.” Contemporary Political Theory 16 (1): 19–40. doi:10.1057/cpt.2016.11.

- Böker, M., and S. Elstub. 2015. “The Possibility of Critical Mini-Publics: Realpolitik and Normative Cycles in Democratic Theory.” Representation 51 (1): 125–144. doi:10.1080/00344893.2015.1026205.

- Brand, U., M. Wissen, et al. 2016. “Social-Ecological Transformation.” In International Encyclopedia of Geography, edited by N. Castree, Hoboken: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Brown, W. 2015. Undoing the Demos: Neoliberalism’s Stealth Revolution. New York: Zone Books.

- Curato, N., J. Dryzek, S. Ercan, C. Hendriks, and S. Niemeyer. 2017. “Twelve Key Findings in Deliberative Democracy Research.” Daedalus 146 (3): 28–38. doi:10.1162/DAED_a_00444.

- Curato, N., M. Hammond, and J. Min. 2018. Power in Deliberative Democracy: Norms, Forums, Systems. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Daly, H. 1991. Steady-State Economics. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: Island Press.

- Dryzek, J. 1990. Discursive Democracy: Politics, Policy, and Political Science. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Dryzek, J. 2000. Deliberative Democracy and Beyond: Liberals, Critics, Contestations. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Dryzek, J. 2016. “Institutions for the Anthropocene: Governance in a Changing Earth System.” British Journal of Political Science 46 (4): 937–956. doi:10.1017/S0007123414000453.

- Dryzek, J. 2017. “Democracy Needs More Trees and Less Trump.” The Conversation, September 3. http://theconversation.com/democracy-needs-more-trees-and-less-trump-74059.

- Dryzek, J., and J. Pickering. 2019. The Politics of the Anthropocene. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Etzion, D., J. Gehman, F. Ferraro, and M. Avidan. 2017. “Unleashing Sustainability Transformations through Robust Action.” Journal of Cleaner Production 140: 167–178. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.06.064.

- Extinction Rebellion 2019. The Extinction Rebellion Guide to Citizens’ Assemblies, available online at https://rebellion.earth/wp/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/The-Extinction-Rebellion-Guide-to-Citizens-Assemblies-Version-1.1-25-June-2019.pdf.

- Flood, C. 2002. Political Myth: A Theoretical Introduction. London: Routledge.

- Goodin, R., and J. Dryzek. 2006. “Deliberative Impacts: The Macro-Political Uptake of Mini-Publics.” Politics and Society 34 (2): 219–244. doi:10.1177/0032329206288152.

- Grönlund, K., A. Bächtiger, and M. Setälä. 2014. Deliberative Mini-Publics: Involving Citizens in the Democratic Process. Colchester: ECPR Press.

- Hammond, M. 2020. “Sustainability as a Cultural Transformation: The Role of Deliberative Democracy.” Environmental Politics 29 (1): 173–192. doi:10.1080/09644016.2019.1684731.

- Hammond, M., and G. Smith. 2017. “Sustainable Prosperity and Democracy: A Research Agenda.” CUSP Working Paper No. 8. Guildford: University of Surrey.

- Hausknost, D. 2020. “The Environmental State and the Glass Ceiling of Transformation.” Environmental Politics 29 (1): 17–37. doi:10.1080/09644016.2019.1680062.

- Holcombe, R. 2018. Political Capitalism: How Economic and Political Power is Made and Maintained. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Jackson, T. 2017. Prosperity without Growth: Foundations for the Economy of Tomorrow. 2nd ed. London: Routledge.

- Knops, A. 2007. “Agonism as Deliberation – on Mouffe’s Theory of Democracy.” Journal of Political Philosophy 15 (1): 115–126. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9760.2007.00267.x.

- Knuth, H. 2019. “‘Fast ein normales Ereignis’: Roger Hallam, britischer Mitgründer der Klimabewegung Extinction Rebellion, spricht über Völkermord – und relativiert den Holocaust. Es tue den Deutschen nicht gut, dass sie ihn fälschlicherweise für einzigartig hielten (Almost a Normal Event: Roger Hallam, British Co-founder of the Extinction Rebellion Climate Movement, Talks About Genocide – and Puts the Holocaust into Perspective. It Doesn’t Do the Germans Good that They Mistakenly Think He’s Unique)” Die Zeit, November 20. https://www.zeit.de/2019/48/extinction-rebellion-roger-hallam-klimaaktivist/komplettansicht (in German).

- Kuenkel, P. 2019. Stewarding Sustainability Transformations: An Emerging Theory and Practice of SDG Implementation. New York: Springer.

- Machin, A. 2020. “Democracy, Disagreement, Disruption: Agonism and the Environmental State.” Environmental Politics 29 (1): 155–172. doi:10.1080/09644016.2019.1684739.

- Meadows, D., D. Meadows, J. Randers, and W. Behrens. 1974. The Limits to Growth. New York: Universe.

- Mert, A. 2009. “Partnerships for Sustainable Development as Discursive Practice: Shifts in Discourses of Environment and Democracy.” Forest Policy and Economics 11 (5--6): 326–339. doi:10.1016/j.forpol.2008.10.003.

- Mert, A. 2019. “Participation(s) in Transnational Environmental Governance: Green Values versus Instrumental Use.” Environmental Values 28 (1): 101–121. doi:10.3197/096327119X15445433913596.

- Niemeyer, S. 2007. “Deliberation in the Wilderness: Displacing Symbolic Politics.” Environmental Politics 13 (2): 347–372.

- Niemeyer, S. 2014. “A Defence of (Deliberative) Democracy in the Anthropocene.” Ethical Perspectives 21 (1): 15–45.

- Olsson, P., V. Galaz, and W. Boonstra. 2014. “Sustainability Transformations: A Resilience Perspective.” Ecology and Society 19 (4): 1–13. doi:10.5751/ES-06799-190401.

- Oreskes, N., and E. Conway. 2014. The Collapse of Western Civilization: A View from the Future. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Parkinson, J., and J. Mansbridge. 2012. Deliberative Systems: Deliberative Democracy at the Large Scale. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Pateman, C. 2012. “Participatory Democracy Revisited.” Perspectives on Politics 10 (1): 7–19. doi:10.1017/S1537592711004877.

- Rosen, M. 1996. On Voluntary Servitude: False Consciousness and the Theory of Ideology. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Setälä, M., and G. Smith. 2018. “Mini-Publics and Deliberative Democracy.” In Oxford Handbook of Deliberative Democracy, edited by A. Bächtiger, J. Dryzek, J. Mansbridge, and M. Warren. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Smith, G. 2003. Deliberative Democracy and the Environment. London: Routledge.

- Spaargaren, G., and A. Mol. 1992. “Sociology, Environment, and Modernity: Ecological Modernization as a Theory of Social Change.” Society and Natural Resources 5 (4): 323–344. doi:10.1080/08941929209380797.

- United Nations. 1992. Agenda 21. https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/Agenda21.pdf

- United Nations 2015. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/21252030%20Agenda%20for%20Sustainable%20Development%20web.pdf

- Ward, H., A. Norval, T. Landman, and J. Pretty. 2003. “Open Citizens’ Juries and the Politics of Sustainability.” Political Studies 51 (2): 282–299. doi:10.1111/1467-9248.00424.

- Warren, M. 2009. “Governance-Driven Democratization.” Critical Policy Studies 3 (1): 3–13. doi:10.1080/19460170903158040.

- Warren, M., and H. Pearse. 2008. Designing Deliberative Democracy: The British Columbia Citizens’ Assembly. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Weinstein, M., R. Turner, and C. Ibáñez. 2013. “The Global Sustainability Transition: It is More than Changing Lightbulbs.” Sustainability: Science, Practice and Policy 9 (1): 4–15. doi:10.1080/15487733.2013.11908103.

- Wenman, M. 2013. Agonistic Democracy: Constituent Power in the Era of Globalisation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- White, S. 1986. “Foucault’s Challenge to Critical Theory.” American Political Science Review 80 (2): 419–432. doi:10.2307/1958266.

- White, S. 2017. A Democratic Bearing: Admirable Citizens, Uneven Injustice, and Critical Theory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED). 1987. Our Common Future. UN Documents. http://www.un-documents.net/our-common-future.pdf

- Wright, C., and D. Nyberg. 2014. “Creative Self-Destruction: Corporate Responses to Climate Change as Political Myths.” Environmental Politics 23 (2): 205–223. doi:10.1080/09644016.2013.867175.