Abstract

Global consumption levels are significant contributors to detrimental environmental change and the current climate crisis. Across Ireland, domestic consumption levels have increased dramatically during the past three decades. Public discourse has focused primarily on minimum levels of consumption, with media outlets frequently reporting on minimum wages and acceptable minimum levels of food, shelter, and healthcare. A dearth of dialogue exists on the concept of maximum levels of consumption. This article proffers that the concept of consumption corridors provides a timely lens to initiate discussion and to critically consider the potential of ascertaining maximum levels of consumption across Ireland. Drawing on analyses of an extensive database of 1,500 households across two policy regions − Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland − we argue that there is no single universally just and ecologically sustainable way of setting limits to consumption. Numerous factors must be considered including scale, policy influences, cultural understandings, and varying expectations of standards of living and quality of life. The article reports on participants’ perceptions of material items as needs and satisfiers and aims to advance methodological applications of the consumption-corridors concept. This study offers evidence highlighting a need for tailored sustainability policies.

Introduction

In western societies, the act of consuming has infiltrated cultural norms forming significant components of an individual’s attempt to find meaning, status, social distinction, social cohesion, and identity formation (Jackson Citation2005a; Princen Citation2002), as well as facilitating a wide range of complex, deeply engrained, social conversations and social processes (Gatersleben, Murtagh, and Abrahamse Citation2014; Smart Citation2010; Bauman Citation2007; Jackson Citation2005a). The reality of our modern “throw-away” culture, with its constant need to satisfy an ever-increasing consumer demand for goods and services, is that excessive consumption levels are exerting immense strain on the global environment (Alfredsson et al. Citation2018). Furthermore, increasing quantities of space, material, and energy are needed to maintain currently increasing levels of consumption (Hubacek et al. Citation2017; UNEP Citation2015). Material-intensive consumption is accompanied by escalating quantities of waste, pollution, and carbon-dioxide (CO2) emissions, with approximately 19 million tons of industrial CO2 emissions per annum alone being attributed to direct lifestyle and consumption-related activities worldwide (UNEP Citation2015). A shift toward sustainable consumption is imperative, particularly for those in political arenas where there is a need to alter current consumption patterns in order to merge economic resilience with environmental protection and social development. This is a key priority if global emission-reduction targets are to be achieved (Jackson Citation2009).

One critical issue within sustainability debates is the association between the “good life” and consumption. The pursuit of happiness or enhancement of quality of life issues in modern consumer society tends to focus on the rapid appropriation and disposal of material goods and services (Bauman Citation2007). Many pro-consumption commentators argue that this ability to consume at will permits the satisfaction of consumer wants and needs through the sense of self-fulfillment and enhanced quality of life that the act of consuming permits (Bauman Citation2007; Smith Citation1937 [1776]). Indeed, one common contemporary preconception equates increased consumption with enhanced quality of life and wellbeing (Donovan and Halpern Citation2003). Critics of consumption challenge this association, arguing that escalating economic growth (and the resulting expansion of consumption rates) has no direct correlation with improved levels of wellbeing or enhanced quality of life (Stutzer and Frey 2010). On the contrary, ever-changing and expanding states of consumption may be linked to higher levels of stress and anxiety in certain instances (Ahuvia Citation2008). Hence, the current scale of consumption may not only be environmentally damaging, but also psychologically harmful to individuals (Fredrickson et al. Citation2013; Jackson Citation2005b). Excessive consumption appears neither to be a factor for attaining the “good life” nor a synonym for a state of happiness.

A certain level of consumption is necessary to address basic human needs. Hence, the distinction between needs and satisfiers is paramount for sustainability debates. Needs tend to be finite, few, and universal, whereas satisfiers are theoretically infinite and can depend on a range of personal, social, and cultural choices (see Max-Neef Citation1992). The distinction between physiological needs and social or psychological needs is also significant. Material commodities tend to be effective satisfiers for physiological needs, yet inferior satisfiers of psychological and social needs. Tsang et al. (Citation2014) argue that attempting to satisfy psychological and social needs through increased materialistic means is not effective. A growing number of authors argue that sufficiency is an organizing principle with the potential to replace the current growth paradigm (Spangenberg Citation2018; Lorek and Spangenberg Citation2014; Gabriel and Bond Citation2019). Spengler (Citation2016) posits sufficiency as the antithesis to modern-day overconsumption which implies the need to establish upper limits for resource consumption (Fuchs Citation2017: Mont Citation2019). In terms of the implications of these debates for sustainable consumption, a greater understanding of what individuals believe to constitute a good life is necessary.

A radically different vision of growth, success, and development is needed to secure a more equitable and sustainable society (Soper Citation2007). Until recently, sustainability policy has been largely based on such a refutably objective measure of income and growth using gross domestic product (GDP) per capita (Stutzer and Frey 2020). Although a reliable tool for measuring progress toward the goal of increased economic production, GDP has been critiqued as a poor measure of progress in relation to wellbeing and enhanced quality of life (Wilkinson and Pickett Citation2009; Oswald and Nattavudh Citation2007). It tends to overemphasize the importance of monetary gains in relation to wellbeing and happiness, while simultaneously underestimating other factors (such as health, family, and stable employment) (Graham 2012; Easterlin Citation1974).

Conceptualizing sustainable consumption in terms of “consumption corridors” (Defila and Di Giulio Citation2020) is an alternative approach that is gaining momentum. This multi-dimensional concept emphasizes the interconnectedness of several domains of living, resulting in a broader scope of focus. The special issue of which this article is a part, posits that the point of departure to define such corridors should be universal needs. The maxima and minima of consumption should refer to satisfiers (and/or resources) that are essential with a view to satisfying universal needs. In theory, consumption corridors demarcate the space for sustainable consumption by defining minimum and maximum consumption standards that permit individuals to satisfy their needs and to live a life they value without impairing the possibility of a good life for other people. The space between these minimum and maximum standards is what is referred to as corridors of sustainable consumption. Consumption corridors have potential to operationalize and implement strong consumption governance.

Consumption corridors are advantageous in that they address planetary boundaries and issues of both intergenerational and intragenerational justice (Lorek and Fuchs Citation2019). With a focus on environmental awareness and finite material concerns, consumption corridors may provide a lens to implement the concept of the “double dividend” (see Jackson Citation2005b, Citation2009) that is inherent in sustainable consumption discourses.Footnote1 Consumption corridors make it possible for individuals to live better by consuming less and reducing their impact on the environment in the process. Maximum consumption limits demarcate the level beyond which an individual’s or group’s consumption may compromise or infringe on another’s ability to meet their needs and achieve minimum consumption (Mont Citation2019). Maximum consumption standards aim to guarantee access to adequate resources for others to live a life they value, both in the present and in the future, by preventing individual consumption from adversely impacting the ability of current and/or future generations to achieve a good life.

Consumption corridors provide a new framework for governance with potential to provide common ground beyond traditional political divides (Defila and Di Giulio Citation2020). Translating consumption-corridor concepts into policies may encourage essential changes in consumption without imposing specific lifestyles on individuals and without demonizing consumption (Defila and Di Giulio Citation2020). If people are willing to engage with arguments in favor and against the concept of consumption corridors, this opens the lines of communication on sustainability issues. It is a complex undertaking to design consumption corridors because they aim to promote the need for redistribution of global resources. This will be challenged in line with other strong sustainable consumption concepts (Mont Citation2019).

In the sections that follow, we argue that there is no singular and universally just and ecologically sustainable means of setting limits to consumption. Humans have varying conceptions concerning how their needs should be satisfied, as well as what their entitlements are to live a good life. There are numerous factors that require consideration including different cultural, historical, and personal contexts within which individuals are embedded. Consumption corridors need to be tailored and developed according to these contexts. Underlying principles of nationally defined corridors mean that an objective need, as well as criteria and procedures on how to define such corridors, merit international discussion and debate. Hence, the relationship between sustainable consumption and corridors of consumption requires further investigation that must first be viewed in terms of the importance of identifying upper and lower limits of consumption.

There is a dearth of research on consumption corridors and their necessary upper and lower limit definitions in an Irish context. This article addresses this gap in knowledge and attempts to initiate discourse around establishing minima and maxima levels of consumption using the island of Ireland.Footnote2 Drawing on extensive analysis of households across Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland, we report on results of a research study that investigated participants’ perceptions of material items in terms of needs and satisfiers in their everyday lives. Perceptions of needs and luxuries are influenced by attitudes, social norms, and habits. These factors are important influences on consumption patterns becauseneeds are not easily quantified and may mean different things to different people. Understanding the reported needs and characteristics of individuals has the potential to assist in creating consumption corridors. The next section presents our study location and this is followed with an outline of the methodological approach employed in the research.

Sustainable consumption and the case of Ireland

Research in the field of sustainable consumption has grown extensively over the past ten years in the Irish context (see Fahy, Goggins, and Jensen Citation2019; Lavelle, Rau, and Fahy Citation2015; Davies, Fahy, and Rau Citation2014). Although there is ample evidence of reduced emissions (related to transport and construction sectors experiencing a steady downward trend during the recession in Ireland) and a recent decline in air pollution during the recent COVID-19 pandemic (EPA Citation2020), domestic consumption levels and subsequent emissions are still growing in line with global trends. Sustainability policy in Ireland has been led predominantly by international initiatives in the environmental field (Pape et al. Citation2011). For example, the European Union’s (EU) Waste Framework Directive 2008 has directly shaped waste-management policy in Ireland and since then the country has had considerable success in achieving national and EU targets for recycling and recovery of waste materials. In addition, the Republic of Ireland adopted its National Sustainable Development Strategy (NSDS) in 1997. However, two decades after implementation of this strategy, several areas still need to be addressed in terms of sustainable consumption for the island. For example, the Organization for Co-operation and Development (OECD) Citation2018) identified housing, health, and commuting to work as priority sustainability areas for Ireland. In order to direct attention to these issues, policy makers have tended to focus on technological solutions, in conjunction with several economic incentives. Commentators posit that consumption behavior is constantly shaped by contextual factors and structural features and pivotal for sustainability policy to recognize and address these factors (Princen Citation2002; Cohen and Murphy Citation2001). The role of human choice, which technological approaches tend to overlook, is also important (Princen Citation2002). While public discourse in Ireland has primarily focused on minimum levels of consumption (with local and national media outlets frequently reporting on minimum wages, acceptable minimum levels of food, shelter, and healthcare), there has been an absence of discussion on the concept of maximum levels of consumption. This article aims to address this dearth of research through the exploration of what individuals consider to be important in terms of satisfiers and needs. The next section describes the methods employed to conduct this study.

Materials and methods

The survey, conducted as part of the CONSENSUS Project, was the first quantitative investigation to date to produce a baseline dataset for three study locations on the island of Ireland on household consumption and lifestyles (see Lavelle, Rau, and Fahy Citation2015). A cross-border focus on attitudes and behaviors toward consumption and lifestyles aimed to address the challenge of implementation of sustainable consumption policies between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland by developing roadmaps toward more sustainable consumption in both regions based on the generation of up-to-date information (Lavelle and Fahy Citation2014). Drawing from analysis of OECD’s reports (Citation2008) and European Action Programmes (EC Citation2008), we identified water, transport, food, and energy as priority areas in terms of sustainable consumption for Ireland. Subsequently, the questionnaire instrument (containing predominantly pre-coded questions) explored sustainable lifestyles and specifically focused on the aforementioned domains.Footnote3 This research enabled a nuanced investigation of household consumption andwe designed our survey using an adapted version of Barr’s Framework of Environmental Behavior (see Barr Citation2006). The survey included questions that probed into social and environmental concern variables, situational variables (i.e., structural, socio-demographic, knowledge, and experience) and psychological variables (e.g., self-efficacy, perceptions of environmental responsibility, social norms and social desirability, and intrinsic motivation) (see Lavelle and Fahy Citation2014). The instrument – CONSENSUS Lifestyle Survey – was developed, piloted, and implemented to collect large-scale data from 1,500 people using a multi-stage cluster sample. The primary clusters consisted of three counties: Derry/Londonderry, Dublin, and Galway (Lavelle and Fahy Citation2016).Footnote4 The total population was defined as all adults 18 years of age or over residing in domestic households in both Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland.

The research design and methods employed in this study were not without their limitations. We were conscious of several challenges involving the use of survey methods – particularly a survey instrument – when exploring attitudes and behavioral change. Some researchers such as Hobson (2003) contend that the use of quantitative methods in the study of human behavior is overly deterministic. The administered nature of this methodological design also raises issues of anonymity and confidentiality, which could deter respondents from participating in the study or promote reluctance to divulge personal information (e.g., age or income levels) to the interviewer (Ong and Weiss Citation2000). This study relied on self-reported data and such data are susceptible to numerous biases such as recall bias, confidence bias, and/or social desirability bias, which may limit the interpretation and generalization of the study’s findings. Although self-report measures utilized on surveys often provide a pragmatic and cost-effective way to measure pro-environmental behaviors (Fahy and Rau Citation2013), researchers who attempt to measure and report pro-environmental behaviors through the use of reported behavioral indices on survey instruments must be cautious of inaccurate reporting of actual behaviors (Barr and Prillwitz Citation2013; Gatersleben, Steg, and Vlek Citation2002; Viklund Citation2004). Another potential weakness related to scale (both in time and space) is inherent when employing this type of methodological approach. Temporally, this research was based on a snapshot of environmental action and attitudes at one point in time and failed to produce longitudinal data. Further, longitudinal research may be necessary to explore how these actions and attitudes change over time.

While acknowledging that surveys are not without their limitations (see Lavelle and Fahy Citation2014 for in-depth discussion), we assert that analysis of large datasets can facilitate more nuanced and detailed examination of various groups of respondents and their potential propensity toward defining items as satisfiers or needs. The fieldwork for this study was conducted over an eleven-month period and the surveying procedure entailed the individual who answered the door being recruited to participate in the administered survey.Footnote5 In terms of non-response, the interviewer would make several attempts to contact the selected households at different times of the day and on different days during the week. If the researcher could not contact a household after repeated attempts, then the dwelling on either side of the non-response household was contacted instead. The data were collected with a tablet computer, and a coding system was designed for each question using a spreadsheet to facilitate exportation directly from the Access interface onto SPSS. The analyses conducted for this article are descriptive in nature. Following the analysis of the results, our concluding discussion critically reflects on the potential contribution that the empirical data generated through this study might have on operationalization of the consumption-corridors concept in Ireland.

Results

Characteristics of sample

A total of 1,500 households participated in the study. outlines the social and demographic profile of the respondents. Results were compared to census data in the Republic of Ireland (CSO Citation2011) and Northern Ireland (NISRA Citation2011).

Table 1. Summary of characteristics of respondents in study.

In terms of national averages, the sample comprised a reasonably representative spread of respondents across all age categories. This was reflective of the national demographic profile of the Republic of Ireland. The Republic of Ireland has a relatively young and growing population with over one fifth of the population under 14 years of age (CSO Citation2011). Individuals over 65 at the time accounted for 12% of the Republic of Ireland’s population and 15% of Northern Ireland’s population (CSO Citation2011; NISRA Citation2011). Respondents’ ages ranged from 18 to 93 years, with an average age of 45 years. This mean age was higher than the mean age in Northern Ireland (38 years) and the Republic of Ireland (36 years), respectively. The proportion of women in this study is higher than the Republic of Ireland’s and Northern Ireland’s population at large (53% and 51% respectively). The proportion of men in this sample (41%) was less than the Republic of Ireland’s population (47%) and Northern Ireland’s population (49%). The proportion of respondents in our sample who had attained tertiary-level education or higher (54%) is higher than in the Republic of Ireland (51%) and Northern Ireland populations (24%) (CSO Citation2011; NISRA Citation2011).

Perceptions of luxury and necessity items

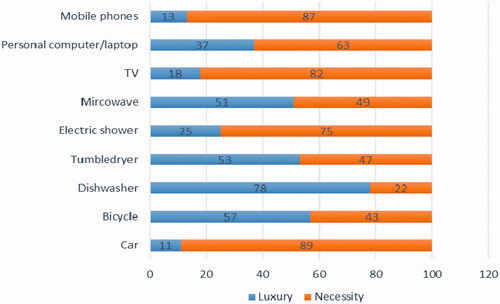

Terms such as luxury and necessity are subjective. In this study, we sought to obtain participants’ perceptions of material items as needs and satisfiers in their everyday lives with a view to helping to commence a discourse on establishing maximum consumption levels in Ireland. The CONSENSUS Lifestyle Survey instrument explicitly posed the question: “Do you consider the following household items as a luxury or necessity?” Respondents were provided with a list of nine common household items and indicated whether, or not, they considered that item to be a luxury or necessity item in their daily lives. outlines responses from the total sample to this question, illustrating the percentage of participants that reported items as either luxuries or necessities. Overall, respondents viewed the majority of items listed (e.g., power shower or electric shower, television, car, and mobile phone) to be necessity items.

Sociodemographic variables and need perceptions

The research explored the association between sociodemographic variables and participants’ perceptions of luxuries and necessities. shows the socioeconomic and demographic characteristics of the participants in the sample who reported that the items listed were necessities. illustrates the statistically significant associations between respondents across the various socioeconomic and demographic profiles and their agreement that items listed were necessity items.

Table 2. Socioeconomic and demographic characteristics of respondents who viewed the items as necessities (percentages).

Table 3. Overview of statistically significant associations between participants divided by sociodemographic variables and their agreement that the following household items were necessities.

Gender of respondents

A number of statistically significant associations were found to exist between male and female participants and their perceptions of car, bicycles, dishwashers, and laptops as necessity items. See for statistically significant associations. No statistically significant associations were noted between male and female participants and their perceptions of luxury and necessity for the following items: mobile phone, laptop, microwave, electric or power shower, and television.

Age cohorts

A number of statistically significant associations were found to exist between participants from different age cohorts and their agreement with the statement that the following items were necessities: car for personal use, bicycle, dishwasher, tumble dryer, microwave, computer and/or laptop, and mobile phone (see ). Younger participants were more likely to report that a microwave, power shower and/or electric shower, personal computer, or laptop and mobile phone were necessities, in comparison to respondents in older cohorts. The television was the exception to this rule with respondents in the older cohort (66 years and older) more likely to perceive the television as a necessity compared to the youngest age group.

Housing tenure

Housing tenure was found to be an important factor in terms of participants’ perceptions of luxury and necessity items. Statistically significant relationships were found to exist between participants in different housing-tenure status and their assessment of the following items as a necessity: tumble dryer, electric shower/power shower, television, personal computer and/or laptop, and mobile phone (see ). A greater number of homeowners (92%) (in comparison to renters (72%) or those whose accommodation was described as rent-free (81%)) viewed a car as a necessity. This difference was found to be statistically significant. In contrast, a greater number of renters (52%) and participants whose accommodation was categorized as rent-free (34%) or other (54%) viewed a bicycle as a necessity, in comparison to 41% of homeowners. This difference was found to be statistically significant. Renters were least likely to view dishwashers as necessity items, in comparison to other housing-tenure categories.

Educational attainment

Educational status was found to be another important factor in terms of participants’ perceptions of luxury and necessity items. Statistically significant relationships existed between participants’ perception of cars as necessity items and their educational attainment. For example, tertiary-level (i.e., university-educated) participants were less likely to report a car as a necessity item, yet more likely to report bicycles as necessity items (compared to participants who attained secondary-level education. Statistically significant relationships were also found to exist between participants’ education status and their perception of the following items as a necessity item: tumble dryers, microwaves, personal computers and/or laptops, and mobile phones.

Rural and urban locations

Several statistically significant associations were found to exist between a person’s residential location (that is whether they resided in a rural or urban electoral district in Ireland) and their agreement with the statement that the following items were necessities: cars, dishwashers, televisions, and laptops. More respondents residing in rural locations, in contrast to those residing in urban locations, reported that they viewed the following items as necessity items: cars, dishwashers, televisions, and laptops and/or personal computers as necessity items (see and ).

Different policy regions

Residing in various policy-region locations appeared to play a role in participants’ perception of necessities and luxuries. Several statistically significant associations were found to exist between a person’s residential location (i.e., whether they resided in Northern Ireland or the Republic of Ireland) and their agreement with the statement that the following household items were necessities: cars, dishwashers, and televisions (see ). More respondents living in Northern Ireland, in comparison to those residing in the Republic of Ireland, reported that these items were necessity items. No statistically significant differences were noted between participants in the Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland and their perceptions of luxury and necessity for the following items: mobile phone, laptop, microwave, power shower, and bicycle.

In the concluding sections, we argue that the responses to the survey questions are important to the discourse surrounding the construction of consumption corridors. They explore what respondents might be willing to do with regard to changing behavior. This has implications for the construction of corridors of consumption and defining minimum and maximum thresholds. We also reflect on the methodological approach adopted in this study and propose recommendations for future research. Specifically, there is a need for more holistic policies and initiatives to incorporate the concept of consumption corridors.

Discussion

As the literature reviewed earlier indicates, the concept of satisfiers and needs are increasingly regarded as important issues in terms of sustainability discourse and policy. We propose that consumption corridors facilitate a timely consideration of the potential of developing maximum levels of consumption across Ireland. The CONSENSUS Lifestyle Survey explored various aspects of consumption in Ireland including respondents’ perceptions of a wide array of household items as luxury or necessity items. In other words, perceptions of needs and satisfiers were unpacked in terms of everyday products.

Results demonstrate that the majority of items (in particular, recent digital innovations and technologies such as laptops, televisions, and mobile phones) were considered to be necessity items rather than luxury items by respondents in this study. This would imply a more utilitarian focus ‒ as well as the attribution of a purposeful rationale and functional value to such products. In contrast, luxury goods are often conducive to comfort and these goods frequently encompass physical, social, and psychological values to individuals (Shukla and Purani Citation2012; Wiedmann, Hennigs, and Siebels Citation2009). This finding is in line with other research that demonstrates that public attitudes on luxury or necessity questions have migrated toward “necessity,” and for most items these changes have taken place at a similar pace among all age groups (Taylor, Funk, and Clarke Citation2006; Twenge, Martin, and Spitzberg Citation2019).

The link between a number of sociodemographic variables and participants’ perceptions of luxury and necessity items is evident from the findings. On one hand, men were more likely to view the majority of the items (e.g., cars, dishwashers, bicycles, and computer and/or laptops) as necessities. On the other hand, women were more inclined to view tumble dryers and televisions in such terms. Researchers often attribute these disparities to gendered practices in the home and workplace (Lennon et al. Citation2020). Such an explanation does not appear to explain the findings in this research.

We found significant differences across gender and generational lines (in terms of patterns of online-media use) for children and adults and what they perceived as satisfiers (luxury items) and needs (necessities) (see Perrin Citation2015; Rideout, Foehr, and Roberts Citation2010; Kayany and Yelsma Citation2000). In the literature pertaining specifically to energy consumption, there are significant differences in energy consumption between men and women, and studies indicate that men consume more energy than women due to differences in disposable income, leisure time, and ownership and use of electronic devices (Pueyo and Maestre Citation2019). This may provide some context for the gender differences in this research that showed a larger proportion of men reporting laptops and/or personal computers to be necessities. Furthermore, gender differences in broader environmental behaviors may have an impact on what men and women view as necessities in daily life. For instance, sociodemographic variables and undertaking of environmental behaviors have been found to be important (De Oliver Citation1999) with women and men found to reduce environmental sustainability in “different proportions” (CAP-NET Citation2014, 13). Such gender differences in broader environmental behaviors may have an impact on what men and women view as necessity and luxury products.

Overall, we found the younger respondents to be more likely to view digital technologies and home appliances (that offer convenience and comfort) (e.g., power shower, laptop, mobile phone, dishwasher) as necessity items, with the exception of the car and the television. Research shows that people in various age cohorts may employ different lenses and mental schemata to deduce luxury or necessity calculations (Taylor, Funk, and Clarke Citation2006). The significant differences found in terms of patterns of online-media use for children and adults (Perrin Citation2015; Rideout, Foehr, and Roberts Citation2010) may contextualize why younger participants in this study reported that personal computer and/or laptops and mobile phones were necessity items in comparison to the older participants.

Although this study did not explore the rationale behind why items were viewed as necessity or luxury items, the survey did examine participants’ willingness to sacrifice some personal comforts in the home in order to save energy. The majority of respondents (70%, n = 1,038) stated that they would be willing to give up some personal household comforts to reduce their energy use. More homeowners (57%) than renters (52%) and respondents living rent-free (37%) reported being willing to accept cuts in their standards of living.

In terms of educational attainment, the greater number of years of schooling a respondent reported the more likely he or she was to identify a car, bicycle, tumble dryer, personal computer and/or laptop, and mobile phone as necessity items. There were slight variations among tertiary- and secondary-level educated respondents reporting items as necessities. For example, marginally more respondents who reported attaining secondary-level education (as opposed to tertiary-level education) indicated the following items as necessities: car, dishwasher, electric or power shower, microwave, and television. These findings may be related to higher educational status and housing tenure which are often correlated with higher income. The study further found that, in general, the more income a person has the more likely he or she is to view items as necessities. This is particularly the case for certain information-era items such as laptops and/or computers and mobile phones, but also includes cars and dishwashers. This finding is in line with another study (see Taylor, Funk, and Clarke Citation2006) that reported a steady acceleration of participants maintaining similar views.

Spatially, this research was conducted across two policy regions comprising the island of Ireland. Several statistically significant differences were found to exist between a person’s residential location (i.e., whether they resided in Northern Ireland or the Republic of Ireland) and their agreement with the statement that the following household items were necessities: car, dishwasher, and television. The sampling strategy also differentiated between rural and urban households. Urban residents were more likely to identify items such as a tumble dryer, microwave, and television as necessities. Equal percentages of urban and rural respondents reported a mobile phone to be a necessity item.

The concept of consumption corridors holds immense promise for operationalizing strong sustainable consumption governance. However, designing and implementing consumption corridors are complex and challenging tasks (Mont Citation2019). We argue that asking 1,500 participants to reflect on ‒ and to identify ‒ the material needs and satisfiers in their lives could provide a first step in developing a bottom-up approach for advancing the application of the consumption-corridors concept across the island of Ireland. Echoing results from another international study (Schäfer, Herde, and Kropp Citation2010), differences across respondents’ consumption patterns cannot be explained merely by differences in regions with differing policy contexts but also need to be interpreted from the standpoint of social stratification (such as levels of income, education, and profession) or variables like age and gender. Humans maintain varying conceptions about entitlements to live a good life. It is crucial to acknowledge these different understandings of needs and how they should be satisfied in order to permit people to live a life they value without impairing the possibility of a good life for others.

We recommend the formulation of policies to endorse and extend the concept of consumption corridors in terms of enhancement of quality of living aspects. For example, in the case of domestic energy use in Ireland and calls to shift toward more sustainable energy use, the predominant approach to date has been a national energy campaign with a focus on two main areas, encouraging retrofitting of homes and increasing energy awareness (see Goggins, Fahy, and Heaslip Citation2019). Organized by the Sustainable Energy Authority of Ireland, the last two decades have seen over 375,000 homes receive government grants for energy-efficiency improvements (Goggins, Fahy, and Heaslip Citation2019). However, to avail of these grants one needs to own the property. This requirement excludes those who rent public or private accommodation. Indeed schemes (such as the Better Energy Homes Scheme), which were established with the goal of supporting householders who receive fuel allowance or those who receive job-seekers benefits, are only available to homeowners (Lavelle, Rau, and Fahy Citation2015). Apart from ensuring that these grants and schemes are tailored to benefit their target audiences, we argue that these economic “fixes” need to be accompanied with an agenda that supports changing practices and lifestyles that use less energy and factors in quality-of-life considerations (such as expectations of comfort) when considering home heating. Such an agenda would support discussions around maximum levels of energy use in homes.

We argue that policy messages with a focus on quality of life may have cultural salience for many people and hence be more likely to promote favorable conditions for advancing the corridors concept. Political shifts are taking place internationally and this is reflected in different policy goals such as the OECD’s policy series of “better policies for better lives” (OECD Citation2011, Citation2020) or the Enquete Commission established in Germany to explore the links between growth, prosperity, and quality of life and their links to sustainable economic activity and social progress in the social market economy (Strunk Citation2015). Similarly, the Well-being Programme of the UK Office for National Statistics Programme (2020) (which was specifically established to measure national wellbeing) reflects this political shift in thinking. Greater critical engagement ‒ from policy makers, businesses, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), and consumers ‒ is essential in order to link issues pertaining to quality of life and wellbeing with consumption corridors. We believe that these groups should emphasize how sustainable living and consumption corridors could improve a person’s quality of life and lead toward “the good life.” The common misconception is that an individual’s quality of life will decrease if sustainable consumption policies are implemented, which has been found not to be the case (see Godin, Laakso, and Sahakian Citation2020).

To date, sustainable consumption policies in Ireland have tended to overlook the implementation of tailored or focused initiatives, instead opting for a “one-size-fits-all” approach to behavior change, which is evident in the environmental awareness campaigns disseminated by television and print media at the national level since 2000 (Goggins, Fahy, and Heaslip Citation2019; Lavelle, Rau, and Fahy Citation2015; Scott Citation2009).

Upon critical reflection, the data gathered through our survey were limited as they did not derive from a deliberative process for consensus building around needs or satisfiers to meet those needs. Within sustainability research, the deployment of large-scale attitudinal surveys is often critiqued for their tendency to provide a superficial identification of consumption issues rather than a deep investigation into the underlying rationale behind the responses and detailed exploration of such actions. While surveys are not without their limitations, it is still important to acknowledge the significance of large data sets for critically inspired and progressively orientated research agendas (Fahy and Rau Citation2013). This methodological approach is important and its merits are widely recognized. Advocates (see, for example, Barr Citation2006 and Motherway et al. Citation2003) argue that surveys permit the identification and examination of trends in attitudes and behaviors. We proffer that analysis of large datasets can facilitate nuanced and detailed consideration of various groups of respondents and their potential propensity toward defining items as satisfiers or needs.

We posit that our results provide a useful starting point to examine potential trends when exploring initial establishment of minimum and maximum levels of consumption. However, for those undertaking future work on operationalizing consumption corridors we would advocate strongly for other more collaborative approaches to establish minimum and maximum consumption levels. This article aims to add to the consumption-corridors literature by exploring the ways in which identification of the needs and characteristics of individuals might assist in creating consumption corridors. This exploratory investigation and its data findings are culturally specific to the island of Ireland. There is a need for research to be reproduced in other cultural contexts and countries and to explore what encompasses a need for individuals and communities, as well as to examine what are suitable satisfiers for those needs relevant to their context. Given that our study indicates that it is important to consider perceptions of necessity and luxury items from a comfort and convenience perspective, future researchers interested in the creation of consumption corridors may wish to consider incorporating an alternative practice theoretical perspective (see Jensen et al. Citation2019; Sahakian et al. Citation2019; Godin, Laakso, and Sahakian Citation2020), which may better enable a critical in-depth exploration of existing expectations around the notions of comfort and convenience.

Conclusion

Our study provides interesting insights that may be useful when attempting to establish minimum and maximum consumption levels across Ireland. Results indicate that it is important to consider perceptions of necessity and luxury items from the perspective of comfort and convenience. Although culture and policy are crucial factors to considering behavior differences and variations, there is clearly a need for more multifaceted and holistic approaches to understanding sustainable consumption. We posit that consumption corridors need to be developed according to specific political, cultural, and social contexts.

Results of this research indicate that a more customized policy approach to different groups of individuals may be more successful than general policy interventions for all. The policy relevance of the findings presented in this study cannot be overestimated. There is a need for all policy actors to recognize the complex, multi-layered nature of needs and satisfiers. Given the urgency of many current sustainability challenges, and the limited effectiveness of many policy initiatives to date, our efforts to promote a more nuanced understanding of needs and satisfiers (especially in key consumption sectors such as energy, water, and mobility) seem timely.

In summary, the concept of consumption corridors recognizes that while there is a need for absolute minimum and maximum consumption, these thresholds will differ across contexts. If the construction of corridors is largely insensitive to sociodemographic differences, including disparities in income, educational status, and housing tenure, resultant policy initiatives are likely to prove inadequate and to leave unaddressed ‒ or potentially exacerbate ‒ social inequalities and societal injustices. We suggest that by focusing on tailoring the construction of corridors could provide a first step in operationalizing a bottom-up approach for advancing a methodological application of the consumption-corridors concept across Ireland. The ultimate goal of the concept (to create a space where sustainable consumption is possible within planetary boundaries) could and should be a galvanizing idea at the national level. A collaborative approach to the construction of consumption corridors is required to foster a genuine cooperative and deliberative process at every level of scale. The research upon which this article is based produced valuable evidence that highlights a need to customize minimum and maximum consumption levels in accordance with differences across policy regions and cultural groupings, as well as different life stages. However, exploring trends in data are only a starting point. We acknowledge the need for more research, specifically more in-depth qualitative work, to assist in establishing minimum and maximum consumption levels. These data have the potential to act as a crucial step forward in the further development of consumption corridors.

Acknowledgements

This article is based on research conducted as part of the CONSENSUS Project which investigated household consumption, environment, and sustainability in the Republic of Ireland and in Northern Ireland.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Within sustainable consumption literature, claims that a reduction in consumption can not only benefit the environment but also make people happier are often referred to as the “double dividend.”

2 For the purposes of this article, the island of Ireland will be referred to as Ireland.

3 The questions were constructed utilizing previous surveys including several studies conducted on general attitudes toward the environment in an Irish context (see Drury, 2000; Motherway et al., 2003). Many of these studies explored the Republic of Ireland in isolation.

4 Thirty electoral districts (EDs) were selected for sampling based on varying social, economic, and demographic characteristics, as well as their varying geographical locations. EDs are defined as the smallest administrative area for which population statistics are published. In rural areas each ED consists of an aggregation of entire townlands. There are 3,440 EDs.

5 The fieldwork for this study was conducted from June 2010 to April 2011.

References

- Ahuvia, A. 2008. “If Money Doesn’t Make Us Happy, Why Do We Act as If It Does?” Journal of Economic Psychology 29 (4): 491–507. doi:10.1016/j.joep.2007.11.005.

- Alfredsson, E., M. Bengtsson, H. Brown, C. Isenhour, S. Lorek, D. Stevis, and P. Vergragt. 2018. “Why Achieving the Paris Agreement Requires Reduced Overall Consumption and Production.” Sustainability: Science, Practice and Policy 14 (1): 1–5. doi:10.1080/15487733.2018.1458815.

- Barr, S. 2006. “Environmental Action in the Home: Investigating the ‘Value-Action’ Gap.” Geography 91 (1): 43–54. doi:10.1080/00167487.2006.12094149.

- Barr, S., and J. Prillwitz. 2013. “Household Analysis: Researching ‘Green’ Lifestyles: A Survey Approach.” In Methods of Sustainability Research in the Social Sciences, edited by F. Fahy and H. Rau, 27–52. London: Sage.

- Bauman, Z. 2007. Consuming Life. London: Wiley.

- Central Statistics Office (CSO). 2011. Census Data 2011. Dublin: Central Statistics Office.

- Cohen, M., and J. Murphy. 2001. Exploring Sustainable Consumption: Environmental Policy and the Social Sciences. Oxford: Pergamon.

- Davies, A., F. Fahy, and H. Rau. 2014. Challenging Consumption: Pathways to a More Sustainable Future. London: Routledge.

- Davies, A., F. Fahy, H. Rau, L. Devaney, R. Doyle, B. Heissesser, M. Hynes, M. Lavelle, and J. Pape. 2015. ConsEnSus: Consumption, Environment and Sustainability. Wexford: EPA Ireland. Available: http://hdl.handle.net/10379/5330.

- De Oliver, M. 1999. “Attitudes and Inaction: A Case Study of the Manifest Demographics of Urban Water Conservation.” Environment and Behavior 31 (3): 372–394. doi:10.1177/00139169921972155.

- Defila, R., and A. Di Giulio. 2020. “The Concept of ‘Consumption Corridors’ Meets Society: How an Idea for Fundamental Changes in Consumption is Received?” Journal of Consumer Policy 43 (2): 315–344. doi:10.1007/s10603-019-09437-w.

- Donovan, N., and D. Halpern. 2003. “Life Satisfaction: The State of Knowledge and Implications for Government.” Paper presented at Conference on Well-Being and Social Capital. Harvard University, November.

- Easterlin, R. 1974. “Does Economic Growth Improve the Human Lot?” In Nations and Households in Economic Growth: Essays in Honor of Moses Abramowitz, edited by P. David and M. Reder. New York: Academic Press.

- Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). 2020. Recent Trends in Air Pollution Trend in Ireland. EPA: Ireland. http://www.epa.ie/newsandevents/news/name,68631,en.html.

- European Commission (EC) 2008. Progress on EU Sustainable Development Strategy. Brussels: European Commission. http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/3217494/5619864/KS-77-07-115-EN.PDF/06ee41ca-2717-46ee-bee5-07e6bf6c26a2.

- Fahy, F., and H. Rau. 2013. “Researching Complex Sustainability Issues: Reflections on Current Challenges and Future Developments.” In Methods of Sustainability Research in the Social Sciences edited by F. Fahy and H. Rau, 192–208. London: Sage.

- Fahy, F., G. Goggins. and C. Jensen, eds. 2019. Energy Demand Challenges in Europe. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Pivot. 10.1007/978-3-030-20339-9_1.

- Fredrickson, B., K. Grewen, K. Coffey, S. Algoe, A. Firestine, J. Arevalo, and S. Cole. 2013. “A Functional Genomic Perspective on Human Well-Being.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 110 (33): 13684–13689. doi:10.1073/pnas.1305419110.

- Fuchs, D. 2017. “Consumption Corridors as a Means for Overcoming Trends.” In The 21st Century Consumer: Vulnerable, Responsible, Transparent? Proceedings of the International Conference on Consumer Research 2016, edited by C. Bala and W. Schuldzinski. Dusseldorf: Verbraucherzentrale NRW.

- Gabriel, Cle-Anne, and Carol Bond. 2019. “Need, Entitlement and Desert: A Distributive Framework for Consumption Degrowth.” Ecological Economics 156: 327–336. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2018.10.006.

- Gatersleben, B., N. Murtagh, and W. Abrahamse. 2014. “Values, Identity and Pro-Environmental Behavior.” Contemporary Social Science 9 (4): 374–392. doi:10.1080/21582041.2012.682086.

- Gatersleben, B., L. Steg, and C. Vlek. 2002. “Measurement and Determinants of Environmental Relevant Consumer Behavior.” Environment and Behavior 34 (3): 335–362. doi:10.1177/0013916502034003004.

- Godin, L., S. Laakso, and M. Sahakian. 2020. “Doing Laundry in Consumption Corridors: Wellbeing and Everyday Life.” Sustainability: Science, Practice and Policy 16 (1): 99–113. doi:10.1080/15487733.2020.1785095.

- Goggins, G., F. Fahy, 2019. and, E. Heaslip. “Reducing Residential Carbon Emissions in Ireland: Challenges and Policy Responses.” In Energy Demand Challenges in Europe, edited by F. Fahy, G. Goggins, and C. Jensen, 47–57. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Pivot. 10.1007/978-3-030-20339-9_5.

- Hubacek, K., G. Baiocchi, K. Feng, R. Castillo, L. Sun, and J. Xue. 2017. “Global Carbon Inequality.” Energy, Ecology and Environment 2 (6): 361–369. doi:10.1007/s40974-017-0072-9.

- International Network for Capacity Building in Integrated Water Resources Management (CAP-NET) and Gender and Water Alliance (GWA). 2014. Why Gender Matters: A Tutorial for Water Managers. Rio de Janeiro: CAP-NET and Delft: GWA. http://cap-net.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/gender-tutorial-mid-res.pdf.

- Jackson, T. 2005a. Motivating Sustainable Consumption: A Review of Evidence on Consumer Behaviour and Behavioural Change. London: Sustainable Development Research Network. http://www.sd-research.org.uk/wpcontent/uploads/motivatingscfinal_000.pdf.

- Jackson, T. 2005b. “Live Better by Consuming Less? Is There a 'Double Dividend' in Sustainable Consumption?” Journal of Industrial Ecology 9 (1–2): 19–36. doi:10.1162/1088198054084734.

- Jackson, T. 2009. Prosperity without Growth: Economics for a Finite Planet. London: Earthscan.

- Jensen, C., G. Goggins, I. Røpke, and F. Fahy. 2019. “Achieving Sustainability Transitions in Residential Energy Consumption across Europe: The Importance of Problem Framings.” Energy Policy 133: 110927. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2019.110927.

- Kayany, J., and P. Yelsma. 2000. “Displacement Effects of Online Media in the Socio-Technical Contexts of Households.” Journal of Broadcasting and Electronic Media 44 (2): 215–229. doi:10.1207/s15506878jobem4402.

- Lavelle, M., and F. Fahy. 2014. “Unpacking the Challenges of Researching Sustainable Consumption and Lifestyles.” In Challenging Consumption: Pathways to a More Sustainable Future, edited by A. Davies, F. Fahy, and H. Rau, 368–378. London: Routledge.

- Lavelle, M., and F. Fahy. 2016. “What’s Consuming Ireland? Exploring Expressed Attitudes and Reported Behaviours towards the Environment and Consumption across Three Study Sites on the Island of Ireland.” Irish Geography 49 (2): 29–54. doi:10.2014/igj.v49i2.1233.

- Lavelle, M., H. Rau, and F. Fahy. 2015. “Different Shades of Green? Unpacking Habitual and Occasional Pro-Environmental Behaviour.” Global Environmental Change 35: 368–378. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2015.09.021.

- Lennon, B., N. Dunphy, C. Gaffney, A. Revez, G. Mullally, and P. O’Connor. 2020. “Citizen or Consumer? Reconsidering Energy Citizenship.” Journal of Environmental Policy and Planning 22 (2): 184–197. doi:10.1080/1523908X.2019.1680277.

- Lorek, S., and D. Fuchs. 2019. “Why Only Strong Sustainable Consumption Governance Will Make a Difference.” In A Research Agenda for Sustainable Consumption Governance edited by O. Mont, 19–34. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar. doi:10.4337/9781788117814.00010.

- Lorek, S., and J. Spangenberg. 2014. “Sustainable Consumption within a Sustainable Economy beyond Green Growth and Green Economies.” Journal of Cleaner Production 63: 33–44. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2013.08.045.

- Max-Neef, M. 1992. “From the Outside Looking. In: Experiences.” In Barefoot' Economics, 208–209. London: Zed Books.

- Mont, O., Ed. 2019. A Research Agenda for Sustainable Consumption Governance. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency (NISRA). 2011. National Census. Belfast: NISRA Census Office.

- Motherway, B., M. Kelly, P. Faughnan, and H. Tovey. 2003. Trends in Irish Environmental Attitudes between 1993 and 2002: First Report of National Survey Data by the Research Programme on Environmental Attitudes, Values and Behaviour in Ireland. Dublin: Social Science Research Centre, University College Dublin.

- Ong, A. D., and D. J. Weiss. 2000. “The Impact of Anonymity on Responses to Sensitive Questions1.” Journal of Applied Social Psychology 30 (8): 1691–1708. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.2000.tb02462.x.

- Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD). 2008. Household Behavior and the Environment: Reviewing the Evidence. Paris: OECD. http://www.oecd.org/environment/consumption-innovation/42183878.pdf.

- Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD). 2011. Better Policies for Better Lives: The OECD at 50 and Beyond. Paris: OECD. http://www.oecd.org/about/47747755.pdf.

- Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD). 2018. OECD Economic Surveys: Ireland 2018. Paris: OECD. 10.1787/eco_surveys-irl-2018-en.

- Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD). 2020. Better Policy Series. Paris: OECD. http://www.oecd.org/about/publishing/betterpoliciesseries.htm.

- Oswald, A., and P. Nattavudh. 2007. “Obesity, Unhappiness, and the Challenge of Affluence: Theory and Evidence.” Economic Journal 117 (521): 441–454. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0297.2007.02077_1.x.

- Pape, J., H. Rau, F. Fahy, and A. Davies. 2011. “Developing Policies and Instruments for Sustainable Consumption: Irish Experiences and Futures.” Journal of Consumer Policy 34 (1): 25–42. doi:10.1007/s10603-010-9151-4.

- Perrin, A. 2015. Social Networking Usage: 2005–2015. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. http://www.pewinternet.org/2015/10/08/2015/Social-Networking-Usage-2005-2015/.

- Princen, T. 2002. “Consumption and Its Externalities: When Economy Meets Ecology.” In Confronting Consumption, edited by T. Princen, M. Maniates, and K. Conca. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Pueyo, A., and M. Maestre. 2019. “Linking Energy Access, Gender and Poverty: A Review of the Literature on Productive Uses of Energy.” Energy Research and Social Science 53: 170–181. doi:10.1016/j.erss.2019.02.019.

- Rideout, V., U. Foehr, and D. Roberts. 2010. Generation M2: Media in the Lives of 8 –18 Year-Olds. Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation.

- Sahakian, M., P. Naef, C. Jensen, G. Goggins, and F. Fahy. 2019. “Challenging Conventions Towards Energy Sufficiency: Ruptures in Laundry and Heating Routines in Europe.” Paper presented at ECEEE Summer Study 2019 Proceedings, Belambra Presqu'île de Giens, France, 3–8 June. aran.library.nuigalway.ie/bitstream/handle/10379/15274/Sahakian_et_al_2019_Challenging_conventions_towards_energy_sufficiency.pdf?sequence=1.

- Schäfer, M., A. Herde, and C. Kropp. 2010. “Life Events as Turning Points for Sustainable Nutrition.” In System Innovation for Sustainability 4: Sustainable Consumption and Production of Food, edited by U. Tischner, U. Kjaernes, E. Stø, and A. Tukker, 210–226. Sheffield: Greenleaf. doi:10.4324/9781351279369-12.

- Scott, K. 2009. A Literature Review on Sustainable Lifestyles and Recommendations for Further Research. Sweden: Stockholm Environment Institute. http://mediamanager.sei.org/documents/Publications/Future/sei_sustainable_lifestyles_evidence_report.pdf.

- Shukla, P., and K. Purani. 2012. “Comparing the Importance of Luxury Value Perceptions in Cross-National Contexts.” Journal of Business Research 65 (10): 1417–1424. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2011.10.007.

- Smart, B. 2010. Consumer Society: Critical Issues and Environmental Consequences. London: Sage.

- Smith, A. 1937 [1776]. The Wealth of Nations. New York: Modern Library.

- Soper, K. 2007. “Re-Thinking the ‘Good Life’: The Citizenship Dimension of Consumer Disaffection with Consumerism.” Journal of Consumer Culture 7 (2): 205–229. doi:10.1177/1469540507077681.

- Spangenberg, J. 2018. “Sufficiency: A Pragmatic, Radical, Visionary Approach.” In Sufficiency: Moving beyond the Gospel of Eco-Efficiency, edited by R. Mastini, 5–8. Brussels: Friends of the Earth Europe.

- Spengler, L. 2016. “Two Types of ‘Enough’: Sufficiency as Minimum and Maximum.” Environmental Politics 25 (5): 921–940. doi:10.1080/09644016.2016.1164355.

- Strunk, F. 2015. “The German Enquete Commission on Growth, Prosperity and Quality of Life: A Model for Futures Studies?” European Journal of Futures Research 3 (1): 58–66. doi:10.1007/s40309-014-0058-1.

- Stutzer, A. 2004. “The Role of Income Aspirations in Individual Happiness.” Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization 54 (1): 89–109. http://www.zora.uzh.ch/id/eprint/52024/1/iewwp124.pdf. doi:10.1016/j.jebo.2003.04.003.

- Taylor, P., C. Funk, and A. Clarke. 2006. Luxury or Necessity? Things We Can’t Live Without: The List Has Grown in the Past Decade. Washington, DC: Pew Research Centre. http://www.pewresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2010/10/Luxury.pdf.

- Tsang, J.-A., T. Carpenter, Ja. Roberts, M. Frisch, and R. Carlisle. 2014. “Why Are Materialists Less Happy? The Role of Gratitude and Need Satisfaction in the Relationship between Materialism and Life Satisfaction.” Personality and Individual Differences 64: 62–66. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2014.02.009.

- Twenge, Je, Ga. Martin, and B. Spitzberg. 2019. “Trends in U.S. Adolescents’ Media Use, 1976–2016: The Rise of Digital Media, the Decline of TV, and the (Near) Demise of Print.” Psychology of Popular Media Culture 8 (4): 329–345. doi:10.1037/ppm0000203.

- UK Office for National Statistics Programme. 2020. Personal Wellbeing in the UK: April 2019-March 2020 Statistical Bulletin. London: UK Office for National Statistics. http://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/wellbeing/bulletins/measuringnationalwellbeing/april2019tomarch2020.

- United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). 2015. Global Outlook on SCP Policies. New York: United Nations Environment Programme. http://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/index.php?page=view&type=400&nr=559&menu=1515.

- Viklund, M. 2004. “Energy Policy Options – from the Perspective of Public Attitudes and Risk Perceptions.” Energy Policy 32 (10): 1159–1171. doi:10.12691/ajap-1-3-6.

- Wiedmann, K., N. Hennigs, and A. Siebels. 2009. “Value-Based Segmentation of Luxury Consumption Behaviour.” Psychology and Marketing 26 (7): 625–651. doi:10.1002/mar.20292.

- Wilkinson, R., and K. Pickett. 2009. The Spirit Level: Why Equality is Better for Everyone. New York: Bloomsbury.