Abstract

Disasters annually ravage numerous African countries. Flooding is the most severe and prevalent adverse event and has serious implications for sustainable development. As the world is currently facing the COVID-19 pandemic, disasters such as flooding are still occurring but limited attention is being paid. This research analyzes the cause of flooding in Nigeria and Ghana, two countries regularly affected by floods. Previous analysis of the causes of flooding has mainly been done on a national scale. This work adopts a transnational approach by studying the flooding phenomena in both countries. It highlights an opportunity for international partnership in disaster-risk reduction (DRR) as both Nigeria and Ghana are signatories to the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction that advocates an understanding of disaster risk and aims to foster international cooperation. Appreciating the root causes of flooding is the first step in building awareness of the common problem that could be the foundation of seeking and adopting solutions. A systematic review of peer-reviewed papers was conducted. This study finds that the underlying drivers of flooding are similar in the two nations and advocates research and data-sharing as ways of partnering to tackle the common problem. This finding has the potential to promote and facilitate capacity building for DRR and flood-risk management (FRM). Potential solutions could also be scaled to other countries of comparable profiles facing related flooding challenges. This approach is likely to yield better and quicker results while presenting opportunities for partnership in achieving the United Nations 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development that has already suffered COVID-19-related setbacks.

Introduction

While African nations face various forms of disaster each year, the resultant adverse events are often underreported (CRED 2015). These adverse events pose a global problem but the impact is more serious in developing countries as a result of fewer resources which undermine effective management and coping ability (Reinhardt, Fu, and Balikuddembe Citation2019). Flooding is the most wide-reaching disaster and constitutes the majority of all disasters in Africa. It is a threat to sustainable development especially in Sub-Saharan African countries with their current levels of development (Adedeji, Odufuwa, and Adebayo Citation2012; Olanrewaju et al. Citation2019). By August of 2020, there had been reports of at least eight serious flooding events and twenty deaths in Nigeria and Ghana during the year though reporting and attention were largely overshadowed by the COVID-19 pandemic.Footnote1 Flooding events in African nations are mostly induced by anthropogenic factors as opposed to uncontrollable events like cyclones and hurricanes (Adedeji, Odufuwa, and Adebayo Citation2012; Echendu Citation2020a). Over the past decade, flooding incidences have been on the rise, constitute the majority of disaster cases, and have led to deaths and damage of up to US$1 trillion (CRED Citation2015; Echendu Citation2021; Hino and Nance Citation2021).

The financial costs of flooding to the many developing nations of Africa are very significant and are predicted to increase in the coming years (Oppenheimer et al. Citation2019). The United Nations 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development calls for a global partnership in addressing problems to achieve sustainable development. Intending to highlight areas of possible partnership on disaster-risk reduction (DRR), this article analyzes the causes of flooding in Nigeria and Ghana, two West African nations that are prone to perennial flooding, and advocates how transnational cooperation in managing flood risks could be developed. The two countries acknowledge their risks to flooding and welcome DRR initiatives as evidenced by their adoption of the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction (SFDRR). The SFDRR encourages cooperation among countries in managing disasters, complementing the sustainable development framework that emphasizes the need for partnerships to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

Understanding and analyzing the causes of flooding being experienced in the study countries is one step toward finding lasting solutions and reducing disaster risk. This would, in turn, promote sustainable development. It is hoped that strengthening this understanding on an international scale between two countries that witness similar phenomena will open new frontiers for cooperation in policy building as advocated in the Sendai Framework. Partnerships among low- and middle-income countries can drive invention, foster collaboration, and promote the research necessary to design evidence-informed policy for disaster response and resilience-building (Bucher et al. Citation2020). This article analyzes the flooding problem from a transnational perspective and identifies an opportunity for cross-border cooperation geared toward finding solutions to problems that have similar root causes, especially among countries of similar profiles.

The SDGs are due to expire in 2030. While the world was already off target by the end of 2019, it is now at risk of severely falling short of meeting its ten-year objectives due to the COVID-19 pandemic (UNDESA Citation2020). Meanwhile, disasters and disaster risk in Africa continue to rise due to a mix of factors including but not limited to climate change. This article lays the groundwork for collaborative work which is anticipated to facilitate quicker problem solving thus saving costs on research while channeling scarce resources to other areas that also deserve attention.

This article represents the only known work to discuss the common problem of flooding in Nigeria and Ghana within the context of the SFDRR and sustainable development. It highlights possible areas of cooperation in policy development and responds to Priority 1 and Target 6 of the SFDRR which call for understanding disaster risk and promoting international cooperation. I first discuss the Sendai Framework and the United Nations 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development laying the contextual framework of this work. The research methods are then discussed. An overview of flooding in Nigeria and Ghana is presented and the main drivers are analyzed. The current state of flood-risk management (FRM) and DRR in the study nations are investigated to understand lapses and areas of improvement. Possible areas of collaboration are presented and I conclude by discussing the implications of the findings and summarizing the key points.

The Sendai Framework and the United Nations 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development

The Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction (SFDRR) came into effect in 2015 as a follow-up to the Hyogo Framework for Action (HFA) which lapsed in the same year (Rivera, Ceesay, and Sillah Citation2020). It is theoretically built on insights gained from the execution of the HFA (de la Poterie and Baudoin Citation2015) and is aimed at reducing the mean per 100,000 global disaster-related deaths and the number of people affected by disasters by 2030 compared with the 2005‒2015 Hyogo Framework targets (UN Citation2015b). The goal is to prevent the occurrence of new disasters and to lower current disaster risk by applying a mix of integrated measures focused on various dimensions: environmental, political, legal, health-related, structural, and technological. The Sendai Framework emphasizes that pursuing this goal requires improving the implementation capability and capacity of developing countries, particularly landlocked countries, small island developing nations, and African countries ‒ and that this necessitates international cooperation and support. The overarching objective is to promote sustainable development and to improve lives. There are seven targets and four priorities for execution in the SFDRR (Aitsi-Selmi, Blanchard, and Murray Citation2016). The Sendai Framework has been lauded as the most holistic and comprehensive disaster-risk policy in current times (Aitsi-Selmi, Blanchard and Murray Citation2016; Briceño Citation2015; Phibbs et al. Citation2016).

The HFA was the disaster risk-reduction plan from 2005 to 2015 that aimed at significantly lowering disaster-related deaths and the economic, social, and environmental losses that globally occurred in the wake of adverse events. There were five areas of priority and practical means and guidelines for action to build resilience to disasters which were spotlighted in the HFA (UNISDR Citation2005). The HFA is deemed the document that popularized the concept of DRR and reflected a focus on risk prevention and preparedness in contrast to response and recovery that had been the priorities in the past (de la Poterie and Baudoin Citation2015).

The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development is the blueprint for prosperity and peace for humans and planet Earth for today and the future. Launched in 2015, the agenda has been endorsed by all of the United Nations member states and at its core are seventeen interconnected sustainable development goals that address an array of global challenges tied to inequality, poverty, environmental degradation, climate change, and peace and justice. The SDGs call for international unity and action in tackling these global challenges (UN Citation2015a) but disasters of various kinds continue to undermine progress toward sustainable development (Mochizuki and Naqvi Citation2019). The outcomes of the SFDRR and the SDGs are interconnected and overlap demonstrating the synchrony between the two agendas as shown in .

There are synergies between the SFDRR and the SDGs. For instance, the Sendai Framework emphasizes that DRR and risk-aware development are instruments to slow the hazard-perpetuating wheel of disaster exposure and ingrained poverty while poverty eradication is the first SDG. Also, disaster-risk mitigation would reduce the negative impact of disasters on productive assets and the agricultural sector. DRR is a precursor to protecting livelihoods and is thereby essential to ensure food security and eradicate hunger. There is strong alignment between the environmental aspect of sustainable development and DRR whereby climate change has an impact on the scale and frequency of environmental disasters such as flooding (Faivre et al. Citation2018). Flooding is of particularly great concern because of the frequency of its occurrence and the impact on affected victims and the environment. The scale, nature, and low reporting of its occurrence in countries such as Nigeria and Ghana in international media make it even more important that attention be paid to this hazard. Understanding its precursors is an initial step in building lasting solutions and analyzing the flooding problems in Ghana and Nigeria will likely foster cooperation between the countries to mitigate the common dilemma. Reducing disaster risk is central to achieving sustainable development especially in developing countries.

Methods

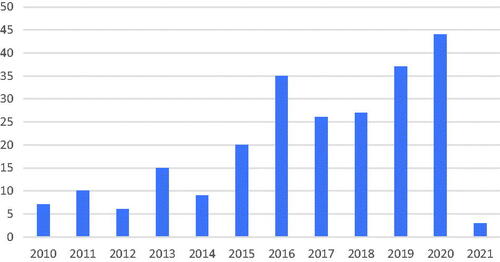

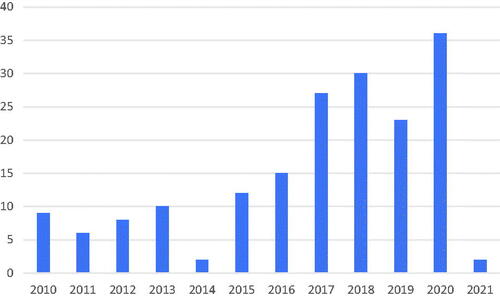

This study employed a systematic review of journal articles sourced from the Web of Science academic database. Such an undertaking involves framing a research question, locating previous research, selecting relevant studies, evaluating the findings, analyzing and synthesizing information, and summarizing and reporting the evidence in a manner that a new and clear conclusion can be drawn and new knowledge produced (Khan et al. Citation2003). Separate searches were conducted for Nigeria and Ghana using the same keywords for articles published from the start of 2010 to mid-February of 2021. Keywords used included “flooding in Ghana” which produced 180 results and “flooding in Nigeria” which produced 239 results, Searches based on “causes of flooding in Nigeria” yielded 40 results while “causes of flooding in Ghana” resulted in 31 results. All of the articles appearing in the results of the search for causes of flooding also featured in the broader search on flooding in both countries. The period was used to ensure currency of the causes of the flooding. The articles were scanned and then selected based on the relevance of their title and abstract to the assessment. In the end, 80 papers were selected in the final round for this systematic review. and depict the results of the searches on flooding in Nigeria and Ghana, respectively. Data for 2021 in the charts cover only the first few months of the year.

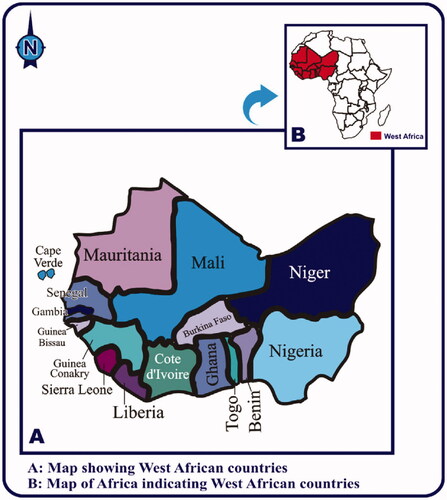

There is already a history of cooperation between the two countries on the common and shared environmental issues faced by their ports with the participation of both state and non-state actors (Barnes-Dabban, van Koppen, and van Tatenhove Citation2018). Partnerships on joint environmental policy making between the port authorities alongside direct engagement with regional intergovernmental actors are developing. is a map of West Africa showing the study countries.

Figure 4. Map of West Africa (Source: Uchechi et al. Citation2021).

Overview of flooding conditions in the study countries

Nigeria

Nigeria is a West African country of 208 million people and comprises 36 states and the Federal Capital Territory of Abuja (Olanrewaju, Olafioye, and Oguntade Citation2020). Many communities in the country increasingly suffer perennial flooding (Njoku, Efiong, and Ayara Citation2020), especially during the rainy season which occurs between March and November. Recent studies estimate that at least 20% of Nigeria’s population is vulnerable to flooding (Abimbola et al. Citation2020; Etuonovbe Citation2011). The annual flooding hazard causes more displacements than any other disaster though exact figures of perennial flood-related displacements, as well as deaths, are not certain from the available literature due to poor reporting (Cirella and Iyalomhe Citation2018). The impact of flooding is felt more by the urban poor who tend to be the most vulnerable because they mostly live in marginal flood-prone locations with poor housing conditions that cannot withstand flooding (Dube, Mtapuri, and Matunhu Citation2018; Echendu Citation2021) The extent of flooding in Nigeria is so severe that it is a major limiting factor to achieving the SDGs (Echendu Citation2020a).

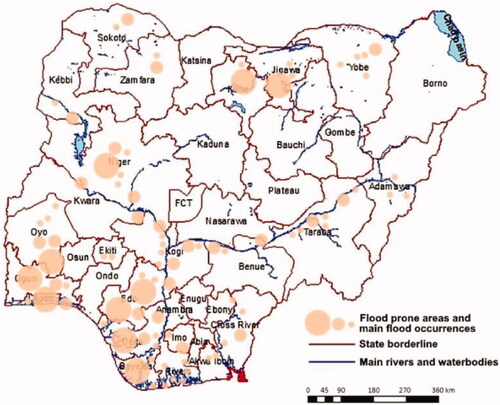

Despite the extent and impact of flooding in Nigeria, little has been done by the authorities to control the hazard as evidenced by the lack of a concrete policy on flooding or a national flood risk-management framework (Adekola and Lamond Citation2018; Echendu Citation2020a). The impact cuts across sectors including but not limited to health, agriculture, education, transport, water resources, environment, and the economy (Echendu Citation2021). Despite the endemic flooding, there is a lack of requisite preparations to avert its effects since rising water is always imminent during the rainy seasons. Nigeria’s flooding is mainly rainfall-induced and compounded by a host of anthropogenic factors tied to poor governance (Agbola et al. Citation2012; Odufuwa, Adedeji, and Oladesu Citation2012). At the same time, evidence suggests the flooding in Nigeria can be effectively averted or controlled by putting in place and implementing a suitable integrated flood risk-management strategy (Adelekan Citation2016; Nkwunonwo, Whitworth, and Baily Citation2016). highlights the areas of Nigeria prone to flooding.

Figure 5. Map of Nigeria showing areas prone to flooding (Source: Cirella and Iyalomhe Citation2018).

Ghana

Ghana, is a West African country with a population of 30 million people (approximately one-seventh the size of Nigeria) and also plagued by perennial flooding (Sarfo and Karuppannan Citation2020). The nation currently comprises 16 regions and experiences an annual flooding incidence, often with accompanying devastation, destruction, and deaths. Neither urban nor rural areas are spared but the occurrence in heavily populated areas has more damaging impacts (Addo and Danso Citation2017; Afriyie, Ganle, and Santos Citation2018; Musah et al. Citation2013). In 2018, two major flooding events on June 18 and 28 in the cities of Kumasi and Accra resulted in 14 fatalities, 34,076 displacements, and significant economic loss (Ansah et al. Citation2020). Another singular flooding-related event on June 3, 2015, resulted in the deaths of 152 persons (Asumadu-Sarkodie, Owusu, and Rufangura Citation2015). Flooding affects more people in Ghana than any other hazard and the fatality rate is only exceeded by fatalities due to epidemics (Okyere, Yacouba, and Gilgenbach Citation2013).

Researchers have blamed Ghanaian authorities for not doing enough to effectively mitigate the recurrent flooding (Poku-Boansi et al. Citation2020; Ahadzie and Proverbs Citation2011). They have also criticized the country’s current laws and policies on flooding like the Blue Agenda, the National Water Policy, and the Sanitation Policy for their inadequacy and poor implementation (Addo and Danso Citation2017; Danso and Addo Citation2017). Ghana’s flooding is found to be mainly anthropogenic (Okyere et al. Citation2013) and the degree and frequency of flood occurrences in the country impairs its pursuit of sustainable development. shows the map of Ghana.

Figure 6. Map of Ghana (Source: https://www.ghanamissionun.org).

Main drivers of flooding in Nigeria and Ghana

Using the Driver-Pressure-State-Impact-Response (DPSIR) framework classification for drivers as causal factors, the drivers of the flooding being experienced in the study countries are analyzed. The DPSIR framework assumes a chain of causal links starting with “driving forces” which could be human activities to “pressures,” for example land-use change. The “states” could be physical states like flooding and “impacts” on ecosystems (health, economic), eventually lead to political or policy “responses,” for instance environmental regulations (Hashemi et al. Citation2014; Rehman et al. Citation2019; Wang, Sun, and Wu Citation2018). The focus here is on the drivers of pluvial urban flooding that occurs on a perennial basis, more frequently and scattered across urban areas in both countries than fluvial or other types of flooding.Footnote2

Despite the difference in the population size of Nigeria and Ghana, the findings of the underlying drivers of flooding are similar. There are multi-causal drivers and as discussed below they include rapid urbanization, inadequate drainage systems and waste management, poor spatial/physical planning, and high rainfall (intensified by climate change).

Rapid urbanization

The African continent is rapidly urbanizing but without the requisite infrastructural base required to sustain the growing population (Bandauko, Annan-Aggrey, and Arku Citation2021). The urban growth rate is expected to continue to rise and Nigeria’s growth rate and population size have been particularly notable as the country has in recent decades become an urban giant in Africa (Fox, Bloch, and Monroy Citation2018). The rapid and unplanned nature of urban growth has made many African cities hotbeds of health and environmental problems such as flooding (Abass Citation2020; Echendu and Georgeou Citation2021; Nyamekye et al. Citation2020; Osawe and Ojeifo Citation2019). Urbanization is the rate of movement of people from rural to urban areas in search of better living opportunities and the process has emerged as a leading cause of flooding in flood-prone African urban centers (Abeka et al. Citation2020; Mashi et al. Citation2020). The expansion and densification of cities change the natural landscape of a place as land-use modifications are implemented to suit the needs of humans. These changes increase impervious areas and significantly reduce vegetative cover that acts as a buffer against floods by absorbing surface water (Korah and Cobbinah Citation2017). When the natural vegetative cover is cleared to make room for construction the resultant impervious surfaces do not absorb water, thus increasing run-off. For instance, Accra, Ghana’s capital city, lost more than half of its vegetation from 1986–2013 (Owusu Citation2018) and this change has had a notable impact on the city’s flood risk (Ighile and Shirakawa Citation2020).

Nigeria and Ghana are both rapidly urbanizing with 55% of the population in Nigeria living in urban areas and 58% of Ghana’s population living in similar urban conditions (Kranjac-Berisavljevic et al. Citation2019; Aliyu and Amadu Citation2017). Urbanization in the two countries has occurred in a largely unplanned fashion and led to the establishment of a surge in informal settlements.

Nigeria’s high urbanization rate has led to myriad problems of which flooding has the most significant impact (Cirella and Iyalomhe Citation2018). The intensity of this pattern has been so pronounced that, for instance, the land area of Kano city increased from 39.2 square kilometers (km2) in 1986 to 256 km2 in 2018 (Mohammed, Hassan, and Badamasi Citation2019). Such patterns of rapid growth have been similar in other parts of the country and the unregulated growth has worsened urban challenges (Aliyu and Amadu Citation2017). Unfortunately, informal settlements are only one of the issues tied to rapid and unfettered urbanization (Ojo, Tpl, and Pojwan Citation2017). In Ghana, there has been a high influx of people seeking to earn a living in the large cities. Having no adequate shelter, they resort to informal settlements characterized by inadequate living conditions and environmental hazards, increasing vulnerabilities (Mensah and Ahadzie Citation2020; Twum and Abubakari Citation2019). These settlements are usually located in areas topographically prone to flooding but are the only areas the poor migrants can afford to live (Amoako and Inkoom Citation2018; Okyere, Yacouba, and Gilgenbach Citation2013).

Urbanization has been attributed to the floods being experienced in Nigeria and Ghana but it is important to note that many fully urbanized countries of the world do not experience flooding of this nature linked to urbanization. These different experiences suggest that there are ways to manage urbanization more effectively and to mitigate issues like flooding.

Inadequate drainage systems and waste management

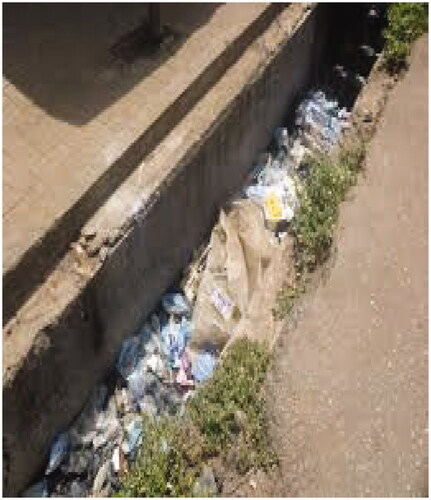

The dearth of adequate stormwater-management infrastructure and drainage is one of the leading causes of flooding in the study countries (Asiedu Citation2020; Salami, Von Meding, and Giggins Citation2017). Effective planning practices incorporate sustainable drainage management (Adedeji, Odufuwa, and Adebayo Citation2012), but poorly constructed and managed drains are hallmarks of the majority of Nigerian and Ghanaian cities. Most of the storm drains are open and small and this design feature makes them unable to support large volumes of water during heavy rainfall. In addition, the absence of covers makes them easy dumping sites by undisciplined citizens. Most of the drains are furthermore characterized by poor or an absence of connectivity to discharge points (Frimpong Citation2013). For instance, drainage for an area may be provided without considering other neighboring locales. The drains then go on to discharge in adjoining communities constituting more flooding problems. and show the small and open nature of drains common in both Nigeria and Ghana. is an example of a drain overtaken by rubbish and can no longer serve its primary purpose.

Figure 8. Drain in a Ghanaian city (Source: Bali Citation2013).

In Nigeria, there is inadequate drainage infrastructure, and the construction of facilities lags behind urban expansion (Echendu Citation2020a). As a result, the existing drainage is not adequate to discharge runoff, thus increasing the risk of flooding (Cirella and Iyalomhe Citation2018). Waste management, a core part of urban governance, is poor in both countries. However, this is known to be a problem for many developing countries and contributes enormously to flood risk (Adeleye et al. Citation2019; Lamond, Bhattacharya, and Bloch Citation2012). The situation is not different in Ghana as lack of drains and ineffectual refuse disposal and management practices are major contributors to the flooding problem (Abass Citation2020; Agyapong and Arthur Citation2018; Braimah et al. Citation2014). In addition to the poor quality of drains to properly channel water, residents dump solid waste in the drains (Echendu Citation2021; Owusu-Ansah Citation2016). In a study by Kordie, Codjoe, and De Graft (Citation2018) on vulnerability to flooding in Ghana, poor waste-disposal practices were found to be the most frequently recorded cause of flooding in the surveyed communities. There have been efforts by the Ghanaian government to combat flooding by building drainages and water-runoff reservoirs along the main river basins in the capital city of Accra but the capacity and size of these drains are still insufficient and the problem is exacerbated by the blockades of accumulated refuse. It is important to conduct an appropriate assessment that would factor in anticipated runoff, and to factor these findings into the design and construction of drainage systems (Tengan and Aigbavboa Citation2016).

Poor physical planning

The importance of spatial planning in mitigating environmental disasters and achieving sustainable development cannot be overemphasized (Adedeji, Odufuwa, and Adebayo Citation2012; Meyer and Auriacombe Citation2019). Yet, the planning system in both Nigeria and Ghana is generally inadequate and has been criticized for ineffectiveness and lack of integration with FRM (Frick-Trzebitzky and Bruns Citation2019; Olalekan Citation2014; Tasantab Citation2019). Nigeria and Ghana are both characterized by poor urban governance and weak planning institutions despite their rapid population and urban growth (Korah and Cobbinah Citation2017; Meyer and Auriacombe Citation2019). The result is the inability of physical planning to keep up with expanding size of cities in the two countries. Urban planning presents opportunities for regulating the environment, mitigating global warming, and achieving sustainable development. However, the detachment of urban planning and implementation from reality worsens the environmental problems faced by African developing nations (Mohammed, Hassan, and Badamasi Citation2019). Corruption and political meddling in land-use matters are also common (Chiweshe Citation2021). Regulation of development is the purview of urban and physical planning and where there is a rise in informal settlements, urban planning has failed.

In Nigeria, there is high demand for housing due to the rapidly growing population of over 200 million people who predominantly reside in the urban areas. This increasing need for housing has resulted in a surge of informal and unplanned settlements. The unregulated manner of urban planning means there is not enough information on the size of built-up areas to adequately assess impacts. Mismanagement and corruption are rife in the urban management sector as evidenced by some buildings having valid approvals in areas not designated for such construction including on drain paths and waterways (Adegboyega et al. Citation2019; Dalil et al. Citation2015; Echendu Citation2020b; Owusu-Ansah Citation2016; Jegede Citation2020). Some town-planning officials are complicit and approved buildings become significantly altered by the owners without adequate authorizations (Oladokun and Proverbs Citation2016). The situation is not different in Ghana as corruption also plagues the planning sector and land-use regulations are relaxed for developers who bribe their way to illegal developments (Acheampong Citation2019; Mwingyine, Akaateba, and Laube Citation2020). The relevant planning agencies do not liaise with each other to improve planning outcomes (Frimpong Citation2013; Poku-Boansi et al. Citation2020). Institutions responsible for urban planning in both countries do not have a lack of knowledgeable professionals or laws and policies to manage the physical environment, but there is a deficit in implementation and control that reduces their effectiveness (Echendu Citation2019; Gyau Citation2018; Ikelegbe and Andrew Citation2012; Korah et al. Citation2017; Owusu-Ansah Citation2016). In summary, poor planning and regulation of development have significantly contributed to flooding problems in the two countries.

High rainfall (intensified by climate change)

Climate change is a global phenomenon but it is a fact that developing countries of the world are disproportionately suffering and will suffer the most damaging future impacts (Akeh and Mshelia Citation2016; Azadi, Yazdanpanah, and Mahmoudi Citation2019). Weather patterns in many parts of the world have changed and in Africa climate-related events are manifesting in disasters like flooding and droughts. Climate change will steadily and continuously increase flood risk in the coming years by inducing sea-level rise, increases in river flows, and heavier, prolonged rainfall durations and flooding (Ahmed et al. Citation2018; Akeh and Mshelia Citation2016). Larger numbers of flooding incidents in Nigeria and Ghana have been attributed to increased rainfall events (Amoateng et al. Citation2018; Campion and Venzke Citation2013; Dike, Lin, and Ibe Citation2020; Tella and Balogun Citation2020). Making the situation worse is the fact that rainfall patterns have also become more erratic and unpredictable with different parts of each country experiencing different phenomena in terms of intensity, duration, frequency, and trends (Ansah et al. Citation2020; Kpanou et al. Citation2021).

In Nigeria, the effects of climate change vary according to the region; for instance, the arid northern areas of the country are getting drier while the humid southern areas are experiencing increasingly wetter conditions (Olaniyi, Olutimehin, and Funmilayo Citation2014). The issue of rainfall-induced flooding is more serious because Nigeria and Ghana lack the infrastructure to channel rainwater and surface-runoff water that exacerbates flood risk.

In Ghana, the rainfall patterns have changed significantly and this has led to increased precipitation and subsequent flooding (Afriyie, Ganle, and Santos Citation2018; Mensah and Ahadzie Citation2020). The most serious flooding events reported in recent years have occurred after episodes of heavier than normal rainfall. In as much as climate change has altered rainfall patterns, numerous research studies have found that flooding is caused more by anthropogenic factors (Adeloye and Rustum Citation2011; Campion and Venzke Citation2013; Olajuyigbe, Rotowa, and Durojaye Citation2012; Owusu-Ansah Citation2016).

Current approaches to FRM and DRR in the study countries

Disasters are not natural events even though the associated hazard may be (Kelman et al. Citation2016; Shi Citation2019). The focus of disaster agencies has shifted from emergency-disaster response to reducing and managing hazards, vulnerability, and exposure. This necessitates identifying and mitigating the elementary drivers of risk. However, there remains a gap in DRR in the study countries.

In Nigeria, there is a lack of legal and policy FRM frameworks at all levels of government which points to an absence of attention to the rising flood risk (Echendu Citation2020a). There has historically been more focus on post-disaster response with the government being more disposed to release funds in the aftermath of disasters than on a preventive basis to avert or mitigate the problem. Addressing and reducing exposure to flood risk is listed as a national priority in the Nigerian government’s disaster risk-management agenda and there is also a national framework aimed at proactive risk management. In reality, no concrete action has taken place and there is not yet a national framework on FRM to harmonize or guide practice (FGN Citation2013; Okoye Citation2019). This situation points to a lack of political will and commitment to address the problem. Despite the presence of relevant institutions, there is insufficient coordination among them. The National Emergency Management Agency (NEMA) is poorly equipped to handle disasters in Nigeria (Mashi, Oghenejabor, and Inkani Citation2019; Olanrewaju et al. Citation2019; Olorunfemi Citation2009). The legislative act establishing NEMA also lacks a clear-cut direction on means to mobilize resources in the aftermath of disasters and does not confer the agency power to ensure integration among the different public and private institutions working in the area of FRM and DRR (Mashi, Oghenejabor, and Inkani Citation2019).

In Ghana, the National Water Policy is the primary program aimed at ensuring the integration of water-resources management (Monney and Ocloo Citation2017). It encompasses measures directed at mitigating floods via flood warning and establishing buffer zones in consultation with relevant communities (Almoradie et al. Citation2020). The Blue Agenda is another policy that focuses on development control, public education, provision of drainage, and flood-control initiatives in urban communities (Danso and Addo Citation2017). However, these policies have failed to achieve the desired results of adequately managing the flood risk (Poku-Boansi et al. Citation2020). The country also has no specific law that addresses flood DRR which highlights the need for legislation or other policy to impel action. Several analysts have decried the lack of clarity of the roles of some of the institutions involved in FRM in Ghana and highlighted their ineffectiveness (Almoradie et al. Citation2020; Atanga Citation2020). In addition, disaster reporting and climate-variability records are deficient as many incidents go unreported which also adversely affects the level of institutional attention (Fadairo, Williams, and Nalwanga Citation2020; Ibeje and Ekwueme Citation2020; Satterthwaite and Bartlett Citation2017; Tschakert et al. Citation2010). The similarity of the issues with DRR and FRM observed here depicts an urgent need to go back to the drawing board in the study countries given the severity and frequency of the flooding issue.

Areas of possible collaboration

As these two countries face the problem of flooding with the same underlying drivers, this presents a collaboration opportunity to find lasting solutions to the common problem to achieve sustainable development. These opportunities are discussed in this section in terms of research and data-sharing.

Research

Research is an area of possible cooperation between the two perennial flooding and disaster-plagued West African countries. Flood-data collection and availability are limited (Almoradie et al. Citation2020; Nkwunonwo, Whitworth, and Baily Citation2020; Ouikotan et al. Citation2017; Satterthwaite and Bartlett Citation2017). Research-backed climate data, as well as soil and land data, are needed to inform DRR and FRM measures. Joint research projects could make available the needed data. These undertakings could be in the areas of assessing risks, establishing enhanced reporting procedures (perhaps involving citizen scientists), developing sustainable monitoring and warning services, improving information dissemination, and building capabilities for mitigation and sustainable response strategies. Individually, funding such intensive research could be more expensive for the two developing countries but cooperating and sharing costs could relieve some financial burdens, with savings directed toward the implementation of ideas and even infrastructural upgrades. While the two countries do not share a common boundary, the similarities of the root causes of the flooding problem underline the need for cooperative capacity building. This is achievable because, despite the more known fractious trade relations between these countries, they have a working relationship on environmental problems.

The place of research in DRR cannot be overemphasized. There is an information gap due to a lack of knowledge in specific areas of DRR and inadequate records on past flood events (Egbinola, Olaniran, and Amanambu Citation2017). Research is key to providing hydrological data, modeling information, flood warning, risk analysis, simulation, forecasting, and adaptation (Kreibich et al. Citation2017; Liu et al. Citation2018). Enhancing scientific expertise can also result in the revelation of previously unidentified gaps. Current approaches do not holistically address complex flooding issues and priority is not given to disaster management in national budgets (Ouikotan et al. Citation2017). Political and institutional support at the local, national, and international levels is needed to finance and build up the necessary research infrastructure.

Data sharing

Institutional tools for managing flooding are poorly defined in both countries. It is important to share data on exposures, vulnerabilities, and hazards given the similarities of the causative factors. Such data can inform flood-risk assessment and response and also enable both countries to learn from each other and previous errors. An upfront framework that outlines collaboration and sharing modalities will help to remove potential problems associated with bi-national cooperation that could impede knowledge sharing. Governments at all levels are encouraged to promote transnational sharing of hydro-meteorological data which can enhance capacity-building and the ability of both nations to battle the common problem. Successful cooperation could set the path for the involvement of other West African countries such as Cameroon and Senegal that suffer flooding to work together as has been done among some of the countries in the European Union.

Conclusion

This article has shown that flooding in Nigeria and Ghana is caused by a mix of socio-political (unplanned urban expansion, inadequate drainage systems and waste management, poor spatial/physical planning) and changing climatic factors (high rainfall). There is evidence that the climatic factors being experienced today are worsened by human actions. It is thus safe to conclude that the flooding being experienced in these countries is mainly due to anthropogenic factors. Working at scales that are larger than a particular geographic area is consistent with the tenets of sustainable development and multilateral collaboration can foster the design of novel strategies that would not otherwise be available. The similarity of the causes of flooding in Nigeria and Ghana presents opportunities to partner and learn from each other in the development of an integrated flood risk-management framework. As the findings of this research have identified the core drivers of the flooding, it would be interesting to extend the research by looking at other countries in Sub-Saharan Africa that witness the same phenomena. If the causes are also similar, it could pave the way for working on flooding solutions that can be applied transnationally with only slight adaptations to suit specific or local situations. This approach would foster better understanding and lay the foundation for the roll-out of integrated solutions. It would also foster information sharing and partnerships in the management of flooding which is a global problem. The exchange of knowledge is important and should be standard practice in today’s world whereby countries can emulate best practices from elsewhere and adapt them to their particular circumstances. Research findings could also potentially yield a framework for influencing policy decisions on an international level. This study also raises many questions. For example, why are the fundamental problems the same? Is it an issue of leadership? Why are the urban management problems similar? Why is there a problem with the implementation of policies? Answers to these questions would provide important knowledge that would transcend the flooding problem and benefit sustainable development.

The current FRM and DRR practices in both countries are deficient, lack integration, and also adequate legal backing. This necessitates a change in these core aspects of disaster mitigation and management. As Nigeria and Ghana have this common problem of flooding with similar divers, cooperation between them is likely to improve their capacity to apply and execute DRR measures and policies, especially in this context of flooding. Interventions consistent with DRR entail understanding the root causes of the problem and tailoring relevant strategies as a response. A transnational approach is advocated in solving the flooding problem which afflicts many countries in the world because of limited opportunities for learning from each other. This article has contributed to the response to Priority 1 and Target 6 of the SFDRR which call for understanding disaster risk and promoting international cooperation. It also responds to the call for academics and other researchers to work to foster knowledge and education on disaster-risk factors by engaging in work that could guide science and inform policy and action. International support is needed to enable countries to mitigate and improve resilience to flooding which would help in ensuring that they move closer to achieving their SDGs. As this article has highlighted possible areas of cooperation in policy development on flood control and management, the governments of both countries at all levels are encouraged to embrace and take up this opportunity to work together to find solutions to this problem that impacts the core fabric of the society. The United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction is urged to take the lead in convening a forum on addressing flooding challenges among these countries with a view to fast-tracking solutions especially in light of the current setbacks to achieving the SDGs as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. It is not too late to stem the tide. Collaboration and partnerships in DRR can contribute to helping the world achieve global goals in a more timely manner.

Acknowledgements

I acknowledge the anonymous peer reviewers whose inputs and comments improved the quality of this article. I also thank my mentors Nichole Georgeou and Allison Goebel for their formative role in my work.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes

1 See http://floodlist.com/

2 Fluvial flooding occurs when water levels in rivers rise and the banks overflow while pluvial flooding happens after prolonged or intense rainfall.

References

- Abass, K. 2020. “Rising Incidence of Urban Floods: Understanding the Causes for Flood Risk Reduction in Kumasi, Ghana.” GeoJournal, Published October 15. doi:10.1007/s10708-020-10319-9.

- Abeka, E., F. Asante, W. Laube, and S. Codjoe. 2020. “Contested Causes of Flooding in Poor Urban Areas in Accra, Ghana: An Actor-Oriented Perspective.” Environment, Development and Sustainability 22 (4): 3033–3049. doi:10.1007/s10668-019-00333-4.

- Abimbola, A., H. Bakar, M. Mat, and O. Adebambo. 2020. “Evaluating the Influence of Resident Agencies’ Participation in Flood Management via Social Media, in Nigeria.” Pertanika Journal of Social Science and Humanities 28 (4): 2765–2785.

- Acheampong, R. 2019. Spatial Planning in Ghana. Cham: Springer.

- Addo, I., and S. Danso. 2017. “Sociocultural Factors and Perceptions Associated with Voluntary and Permanent Relocation of Flood Victims: A Case Study of Sekondi-Takoradi Metropolis in Ghana.” Jàmbá: Journal of Disaster Risk Studies 9 (1): 1–10. doi:10.4102/jamba.v9i1.303.

- Adedeji, O., B. Odufuwa, and O. Adebayo. 2012. “Building Capabilities for Flood Disaster and Hazard Preparedness and Risk Reduction in Nigeria: Need for Spatial Planning and Land Management.” Journal of Sustainable Development in Africa 14 (1): 45–58.

- Adegboyega, S., J. Oloukoi, A. Olajuyigbe, and O. Ajibade. 2019. “Evaluation of Unsustainable Land Use/Land Cover Change on Ecosystem Services in Coastal Area of Lagos State, Nigeria.” Applied Geomatics 11 (1): 97–110. doi:10.1007/s12518-018-0242-2.

- Adekola, O., and J. Lamond. 2018. “A Media Framing Analysis of Urban Flooding in Nigeria: Current Narratives and Implications for Policy.” Regional Environmental Change 18 (4): 1145–1159. doi:10.1007/s10113-017-1253-y.

- Adelekan, I. 2016. “Flood Risk Management in the Coastal City of Lagos, Nigeria.” Journal of Flood Risk Management 9 (3): 255–264. doi:10.1111/jfr3.12179.

- Adeleye, B., A. Popoola, L. Sanni, N. Zitta, and O. Ayangbile. 2019. “Poor Development Control as Flood Vulnerability Factor in Suleja, Nigeria.” Town and Regional Planning 74 (1): 23–35. doi:10.18820/2415-0495/trp74i1.3.

- Adeloye, A., and R. Rustum. 2011. “Lagos (Nigeria) Flooding and Influence of Urban Planning.” Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers – Urban Design and Planning 164 (3): 175–187. doi:10.1680/udap.1000014.

- Afriyie, K., J. Ganle, and E. Santos. 2018. “‘The Floods Came and We Lost Everything’: Weather Extremes and Households’ Asset Vulnerability and Adaptation in Rural Ghana.” Climate and Development 10 (3): 259–274. doi:10.1080/17565529.2017.1291403.

- Agbola, B., O. Ajayi, O. Taiwo, and B. Wahab. 2012. “The August 2011 Flood in Ibadan, Nigeria: Anthropogenic Causes and Consequences.” International Journal of Disaster Risk Science 3 (4): 207–217. doi:10.1007/s13753-012-0021-3.

- Agyapong, D., and K. Arthur. 2018. “Sustainable Business Practices among MSMEs: Evidence from Four Metropolitan Areas in Ghana.” International Conference on Innovation and Entrepreneurship. https://www.proquest.com/conference-papers-proceedings/sustainable-business-practices-among-msmes/docview/2291485804/se-2.

- Ahadzie, D., and D. Proverbs. 2011. “Emerging Issues in the Management of Floods in Ghana.” International Journal of Safety and Security Engineering 1 (2): 111–182. doi:10.2495/SAFE-V1-N2-182-192.

- Ahmed, S., S. Agodzo, K. Adjei, M. Deinmodei, and V. Ameso. 2018. “Preliminary Investigation of Flooding Problems and the Occurrence of Kidney Disease around Hadejia-Nguru Wetlands, Nigeria and the Need for an Ecohydrology Solution.” Ecohydrology & Hydrobiology 18 (2): 212–224. doi:10.1016/j.ecohyd.2017.11.005.

- Aitsi-Selmi, A., K. Blanchard, and V. Murray. 2016. “Ensuring Science is Useful, Usable and Used in Global Disaster Risk Reduction and Sustainable Development: A View through the Sendai Framework Lens.” Palgrave Communications 2 (1): 1–9. doi:10.1057/palcomms.2016.16.

- Akeh, G., and A. Mshelia. 2016. “Climate Change and Urban Flooding: Implications for Nigeria’s Built Environment.” MOJ Ecology and Environmental Science 1: 1–4.

- Aliyu, A., and L. Amadu. 2017. “Urbanization, Cities, and Health: The Challenges to Nigeria – A Review.” Annals of African Medicine 16 (4): 149–158. doi:10.4103/aam.aam_1_17.

- Almoradie, A., M. Brito, M. Evers, A. Bossa, M. Lumor, C. Norman, Y. Yacouba, and J. Hounkpe. 2020. “Current Flood Risk Management Practices in Ghana: Gaps and Opportunities for Improving Resilience.” Journal of Flood Risk Management 13 (4): e12664. doi:10.1111/jfr3.12664.

- Amoako, C., and D. Inkoom. 2018. “The Production of Flood Vulnerability in Accra, Ghana: Re-Thinking Flooding and Informal Urbanisation.” Urban Studies 55 (13): 2903–2922. doi:10.1177/0042098016686526.

- Amoateng, P., C. Finlayson, J. Howard, and B. Wilson. 2018. “A Multi-Faceted Analysis of Annual Flood Incidences in Kumasi, Ghana.” International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 27: 105–117. doi:10.1016/j.ijdrr.2017.09.044.

- Ansah, S., M. Ahiataku, C. Yorke, F. Otu-Larbi, B. Yahaya, P. Lamptey, and M. Tanu. 2020. “Meteorological Analysis of Floods in Ghana.” Advances in Meteorology 2020: 1–14. doi:10.1155/2020/4230627.

- Asiedu, J. 2020. “Reviewing the Argument on Floods in Urban Areas.” Theoretical and Empirical Researches in Urban Management 15 (1): 24–41.

- Asumadu-Sarkodie, S., P. Owusu, and P. Rufangura. 2015. “Impact Analysis of Flood in Accra, Ghana.” Advances in Applied Science Research 6 (9): 53–78.

- Atanga, R. 2020. “The Role of Local Community Leaders in Flood Disaster Risk Management Strategy Making in Accra.” International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 43: 101358. doi:10.1016/j.ijdrr.2019.101358.

- Azadi, Y., M. Yazdanpanah, and H. Mahmoudi. 2019. “Understanding Smallholder Farmers’ Adaptation Behaviors through Climate Change Beliefs, Risk Perception, Trust, and Psychological Distance: Evidence from Wheat Growers in Iran.” Journal of Environmental Management 250: 109456. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2019.109456.

- Bali, D. 2013. Stolen Trash Bins Contribute to Malaria, Flooding. Washington, DC: Pulitzer Center.

- Bandauko, E., E. Annan-Aggrey, and G. Arku. 2021. “Planning and Managing Urbanization in the Twenty-First Century: Content Analysis of Selected African Countries’ National Urban Policies.” Urban Research & Practice 14 (1): 94–104. doi:10.1080/17535069.2020.1803641.

- Barnes-Dabban, H., C. van Koppen, and J. van Tatenhove. 2018. “Regional Convergence in Environmental Policy Arrangements: A Transformation towards Regional Environmental Governance for West and Central African Ports?” Ocean & Coastal Management 163: 151–161. doi:10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2018.06.013.

- Braimah, M., I. Abdul-Rahaman, D. Oppong-Sekyere, P. Momori, A. Abdul-Mohammed, and G. Dordah. 2014. “A Study into the Causes of Floods and Its Socio-Economic Effects on the People of Sawaba in the Bolgatanga Municipality, Upper East, Ghana.” International Journal of Pure and Applied Bioscences 2 (1): 189–195.

- Briceño, S. 2015. “What to Expect after Sendai: Looking Forward to More Effective Disaster Risk Reduction.” International Journal of Disaster Risk Science 6 (2): 202–204. doi:10.1007/s13753-015-0047-4.

- Bucher, A., A. Collins, B. Heaven Taylor, D. Pan, E. Visman, J. Norris, J. Gill, et al. 2020. “New Partnerships for Co-Delivery of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.” International Journal of Disaster Risk Science 11 (5): 680–685. doi:10.1007/s13753-020-00293-8.

- Campion, B., and J. Venzke. 2013. “Rainfall Variability, Floods and Adaptations of the Urban Poor to Flooding in Kumasi, Ghana.” Natural Hazards 65 (3): 1895–1911. doi:10.1007/s11069-012-0452-6.

- Chiweshe, M. 2021. “Urban Land Governance and Corruption in Africa.” In Land Issues for Urban Governance in Sub-Saharan Africa, edited by R. Home, 225–236. Cham: Springer.

- Cirella, G., and F. Iyalomhe. 2018. “Flooding Conceptual Review: Sustainability-Focalized Best Practices in Nigeria.” Applied Sciences 8 (9): 1558. doi:10.3390/app8091558.

- Center for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters (CRED). 2015. The Human Cost of Weather-Related Disasters, 1995–2015. Geneva: United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction.

- Dalil, M., M. Mohammad, U. Yamman, A. Husaini, and S. Mohammed. 2015. “An Assessment of Flood Vulnerability on Physical Development along Drainage Channels in Minna, Niger State, Nigeria.” African Journal of Environmental Science and Technology 9 (1): 38–46.

- Danso, S., and I. Addo. 2017. “Coping Strategies of Households Affected by Flooding: A Case Study of Sekondi-Takoradi Metropolis in Ghana.” Urban Water Journal 14 (5): 539–545. doi:10.1080/1573062X.2016.1176223.

- de la Poterie, A., and M. Baudoin. 2015. “From Yokohama to Sendai: Approaches to Participation in International Disaster Risk Reduction Frameworks.” International Journal of Disaster Risk Science 6 (2): 128–139. doi:10.1007/s13753-015-0053-6.

- Dike, V., Z. Lin, and C. Ibe. 2020. “Intensification of Summer Rainfall Extremes over Nigeria during Recent Decades.” Atmosphere 11 (10): 1084. doi:10.3390/atmos11101084.

- Dube, E., O. Mtapuri, and J. Matunhu. 2018. “Flooding and Poverty: Two Interrelated Social Problems Impacting Rural Development in Tsholotsho District of Matabeleland North Province in Zimbabwe.” Jàmbá: Journal of Disaster Risk Studies 10 (1): 1–7. doi:10.4102/jamba.v10i1.455.

- Echendu, A., and N. Georgeou. 2021. “‘Not Going to Plan’: Urban Planning, Flooding, and Sustainability in Port Harcourt City, Nigeria.” Urban Forum 32 (3): 311–332. doi:10.1007/s12132-021-09420-0.

- Echendu, A. 2020a. “The Impact of Flooding on Nigeria’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).” Ecosystem Health and Sustainability 6 (1): 1791735. doi:10.1080/20964129.2020.1791735.

- Echendu, A. 2020b. “Urban Planning – ‘It’s All about Sustainability’: Urban Planners’ Conceptualizations of Sustainable Development in Port Harcourt, Nigeria.” International Journal of Sustainable Development and Planning 15 (5): 593–601. doi:10.18280/ijsdp.150501.

- Echendu, A. 2021. “Relationship between Urban Planning and Flooding in Port Harcourt City, Nigeria: Insights from Planning Professionals.” Journal of Flood Risk Management 14 (2): e12693. doi:10.1111/jfr3.12693.

- Echendu, A. 2019. “Urban Planning, Sustainable Development and Flooding: A Case Study of Port Harcourt City, Nigeria.” Master’s thesis, Western Sydney University.

- Egbinola, C., H. Olaniran, and A. Amanambu. 2017. “Flood Management in Cities of Developing Countries: The Example of Ibadan, Nigeria.” Journal of Flood Risk Management 10 (4): 546–554. doi:10.1111/jfr3.12157.

- Etuonovbe, A. 2011. “The Devastating Effect of Flooding in Nigeria.” FIG Working Week: Bridging the Gap between Cultures, Marrakech, Morocco, May 18–22.

- Fadairo, O., P. Williams, and F. Nalwanga. 2020. “Perceived Livelihood Impacts and Adaptation of Vegetable Farmers to Climate Variability and Change in Selected Sites from Ghana, Uganda and Nigeria.” Environment, Development and Sustainability 22 (7): 6831–6849. doi:10.1007/s10668-019-00514-1.

- Faivre, N., A. Sgobbi, S. Happaerts, J. Raynal, and L. Schmidt. 2018. “Translating the Sendai Framework into Action: The EU Approach to Ecosystem-Based Disaster Risk Reduction.” International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 32: 4–10. doi:10.1016/j.ijdrr.2017.12.015.

- Federal Government of Nigeria (FGN). 2013. Nigeria Post-Disaster Needs Assessment: A Report by the Federal Government of Nigeria, with Technical Support from the European Union, United Nations, World Bank, and Other Partners – Nigeria Post-Disaster Need Assessment. Lagos: FGN.

- Fox, S., R. Bloch, and J. Monroy. 2018. “Understanding the Dynamics of Nigeria’s Urban Transition: A Refutation of the ‘Stalled Urbanisation’ Hypothesis.” Urban Studies 55 (5): 947–964. doi:10.1177/0042098017712688.

- Frick-Trzebitzky, F., and A. Bruns. 2019. “Disparities in the Implementation Gap: Adaptation to Flood Risk in the Densu Delta, Accra, Ghana.” Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning 21 (5): 577–592. doi:10.1080/1523908X.2017.1343136.

- Frimpong, A. 2013. “Perennial Floods in the Accra Metropolis: Dissecting the Causes and Possible Solutions.” African Social Science Review 6 (1): 1.

- Gyau, K. 2018. “Urban Development and Governance in Nigeria: Challenges, Opportunities and Policy Direction.” International Development Planning Review 40 (1): 27–49.

- Hashemi, M., F. Zare, A. Bagheri, and A. Moridi. 2014. “Flood Assessment in the Context of Sustainable Development Using the DPSIR Framework.” International Journal of Environmental Protection and Policy 2 (2): 41–49. doi:10.11648/j.ijepp.20140202.11.

- Hino, M., and E. Nance. 2021. “Five Ways to Ensure Flood-Risk Research Helps the Most Vulnerable.” Nature 595 (7865): 27–29.

- Ibeje, A., and B. Ekwueme. 2020. “Regional Flood Frequency Analysis Using Dimensionless Index Flood Method.” Civil Engineering Journal 6 (12): 2425–2436. doi:10.28991/cej-2020-03091627.

- Ighile, E., and H. Shirakawa. 2020. “A Study on the Effects of Land Use Change on Flooding Risks in Nigeria.” Geographia Technica 15 (1): 91–101. doi:10.21163/GT_2020.151.08.

- Ikelegbe, O., and O. Andrew. 2012. “Planning the Nigerian Environment: Laws and Problems of Implementation.” Contemporary Journal of Social Sciences 1 (2): 151–161.

- Jegede, A. 2020. “Environmental Laws in Nigeria: Negligence and Compliance in the Building of Houses on Erosion and Flood Prone Areas in the South-South Region of Nigeria.” European Journal of Environment and Earth Sciences 1 (3): 1–9. doi:10.24018/ejgeo.2020.1.3.23.

- Kelman, I., J. Gaillard, J. Lewis, and J. Mercer. 2016. “Learning from the History of Disaster Vulnerability and Resilience Research and Practice for Climate Change.” Natural Hazards 82 (S1): 129–143. doi:10.1007/s11069-016-2294-0.

- Khan, K., R. Kunz, J. Kleijnen, and G. Antes. 2003. “Five Steps to Conducting a Systematic Review.” Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 96 (3): 118–121. doi:10.1177/014107680309600304.

- Korah, P., and P. Cobbinah. 2017. “Juggling through Ghanaian Urbanisation: Flood Hazard Mapping of Kumasi.” GeoJournal 82 (6): 1195–1212. doi:10.1007/s10708-016-9746-7.

- Korah, P., P. Cobbinah, and A. Nunbogu. 2017. “Spatial Planning in Ghana: Exploring the Contradictions.” Planning Practice & Research 32 (4): 361–384. doi:10.1080/02697459.2017.1378977.

- Kordie, G., S. Codjoe, and A. De Graft. 2018. “Perceived Vulnerability to Flooding among Urban Poor Dwellers in Accra.” Ethiopian Journal of Environmental Studies and Management 11 (3): 317–331.

- Kpanou, M., P. Laux, T. Brou, E. Vissin, P. Camberlin, and P. Roucou. 2021. “Spatial Patterns and Trends of Extreme Rainfall over the Southern Coastal Belt of West Africa.” Theoretical and Applied Climatology 143 (1-2): 473–487. doi:10.1007/s00704-020-03441-8.

- Kranjac-Berisavljevic, G., G. Teye, and B. Gandaa. 2019. “Disaster Management in Ghana: Review of Efforts by Government and Research.” Paper Presented at the Fourth Global Summit of Research Institutes for Disaster Risk Reduction, Kyoto, Japan, March 13–15.

- Kreibich, H., G. Di Baldassarre, S. Vorogushyn, J. Aerts, H. Apel, G. Aronica, K. Arnbjerg-Nielsen, et al. 2017. “Adaptation to Flood Risk: Results of International Paired Flood Event Studies.” Earth’s Future 5 (10): 953–965. doi:10.1002/2017EF000606.

- Lamond, J., N. Bhattacharya, and R. Bloch. 2012. “The Role of Solid Waste Management as Response to Urban Flood Risk in Developing Countries: A Case Study Analysis.” WIT Transactions on Ecology and the Environment 159: 193–204.

- Liu, C., L. Guo, L. Ye, S. Zhang, Y. Zhao, and T. Song. 2018. “A Review of Advances in China’s Flash Flood Early-Warning System.” Natural Hazards 92 (2): 619–634. doi:10.1007/s11069-018-3173-7.

- Mashi, S., A. Inkani, O. Obaro, and A. Asanarimam. 2020. “Community Perception, Response and Adaptation Strategies towards Flood Risk in a Traditional African City.” Natural Hazards 103 (2): 1727–1759. doi:10.1007/s11069-020-04052-2.

- Mashi, S., O. Oghenejabor, and A. Inkani. 2019. “Disaster Risks and Management Policies and Practices in Nigeria: A Critical Appraisal of the National Emergency Management Agency Act.” International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 33: 253–265. doi:10.1016/j.ijdrr.2018.10.011.

- Mensah, H., and D. Ahadzie. 2020. “Causes, Impacts and Coping Strategies of Floods in Ghana: A Systematic Review.” SN Applied Sciences 2: 792.

- Meyer, N., and C. Auriacombe. 2019. “Good Urban Governance and City Resilience: An Afrocentric Approach to Sustainable Development.” Sustainability 11 (19): 5514. doi:10.3390/su11195514.

- Mochizuki, J., and A. Naqvi. 2019. “Reflecting Disaster Risk in Development Indicators.” Sustainability 11 (4): 996. doi:10.3390/su11040996.

- Mohammed, M., N. Hassan, and M. Badamasi. 2019. “In Search of Missing Links: Urbanisation and Climate Change in Kano Metropolis, Nigeria.” International Journal of Urban Sustainable Development 11 (3): 309–318. doi:10.1080/19463138.2019.1603154.

- Monney, I., and K. Ocloo. 2017. “Towards Sustainable Utilisation of Water Resources: A Comprehensive Analysis of Ghana’s National Water Policy.” Water Policy 19 (3): 377–389. doi:10.2166/wp.2017.114.

- Musah, B., E. Mumuni, O. Abayomi, and M. Jibrel. 2013. “Effects of Floods on the Livelihoods and Food Security of Households in the Tolon/Kumbumgu District of the Northern Region of Ghana.” American Journal of Research Communication 1 (8): 160–171.

- Mwingyine, D., M. Akaateba, and W. Laube. 2020. “Elite Capture of Land Commodification and Land Use Planning in Peri-Urban Northern Ghana.” In Civilizing Resource Investments and Extractivism: Societal Negotiations and the Role of Law, edited by A. Pereira and W. Laube, 185–208. Münster: LIT Verlag.

- Njoku, C., J. Efiong, and N. Ayara. 2020. “A Geospatial Expose of Flood-Risk and Vulnerable Areas in Nigeria.” International Journal of Applied Geospatial Research 11 (3): 1–24.

- Nkwunonwo, U., M. Whitworth, and B. Baily. 2016. “A Review and Critical Analysis of the Efforts towards Urban Flood Risk Management in the Lagos Region of Nigeria.” Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences 16 (2): 349–369. doi:10.5194/nhess-16-349-2016.

- Nkwunonwo, U., M. Whitworth, and B. Baily. 2020. “A Review of the Current Status of Flood Modelling for Urban Flood Risk Management in the Developing Countries.” Scientific African 7: e00269. doi:10.1016/j.sciaf.2020.e00269.

- Nyamekye, C., S. Kwofie, B. Ghansah, E. Agyapong, and L. Boamah. 2020. “Assessing Urban Growth in Ghana Using Machine Learning and Intensity Analysis: A Case Study of the New Juaben Municipality.” Land Use Policy 99: 105057. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2020.105057.

- Odufuwa, O., H. Adedeji, and O. Oladesu. 2012. “Floods of Fury in Nigerian Cities.” Journal of Sustainable Development 5 (7): 69–79.

- Ojo, S., D. Tpl, and M. Pojwan. 2017. “Urbanization and Urban Growth: Challenges and Prospects for National Development.” Journal of Humanities and Social Policies 3 (1): 65–71.

- Okoye, C. 2019. “Perennial Flooding and Integrated Flood Risk Management Strategy in Nigeria.” International Journal of Economics, Commerce, and Management 7 (9): 364–375.

- Okyere, Y., Y. Yacouba, and D. Gilgenbach. 2013. “The Problem of Annual Occurrences of Floods in Accra: An Integration of Hydrological, Economic and Political Perspectives.” Theoretical and Empirical Researches in Urban Management 8 (2): 45–79.

- Oladokun, V., and D. Proverbs. 2016. “Flood Risk Management in Nigeria: A Review of the Challenges and Opportunities.” Flood Risk Management and Response 6 (3): 485–497.

- Olajuyigbe, A., O. Rotowa, and E. Durojaye. 2012. “An Assessment of Flood Hazard in Nigeria: The Case of Nile 12, Lagos.” Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences 3 (2): 367–375.

- Olalekan, B. 2014. “Urbanization, Urban Poverty, Slum and Sustainable Urban Development in Nigerian Cities: Challenges and Opportunities.” Developing Country Studies 4 (18): 13–19.

- Olaniyi, O., I. Olutimehin, and O. Funmilayo. 2014. “Review of Climate Change and Its Effect on Nigerian Ecosystem.” International Journal of Rural Development, Environment and Health Research 2 (3): 70–81.

- Olanrewaju, C., M. Chitakira, O. Olanrewaju, and E. Louw. 2019. “Impacts of Flood Disasters in Nigeria: A Critical Evaluation of Health Implications and Management.” Jàmbá: Journal of Disaster Risk Studies 11 (1): 1–9.

- Olanrewaju, S., S. Olafioye, and E. Oguntade. 2020. “Modelling Nigeria Population Growth: A Trend Analysis Approach.” International Journal of Innovative Science and Research Technology 5 (4): 52–64.

- Olorunfemi, F. 2009. “Disaster Incidence and Management in Nigeria.” Research Review of the Institute of African Studies 24 (2): 42711. doi:10.4314/rrias.v24i2.42711.

- Oppenheimer, M., B. Glavovic, J. Hinkel, R. van de Wal, A. Magnan, A. Abd-Elgawad, R. Cai, M. Cifuentes-Jara, R. Deconto, and T. Ghosh. 2019. “Sea Level Rise and Implications for Low-Lying Islands, Coasts and Communities.” IPCC Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate, edited by H. Pörtner. D. Roberts, V. Masson-Delmotte, P. Zhai, M. Tignor, E. Poloczanska, K. Mintenbeck, A. Alegria, M. Nicolai, A. Okem, J. Petzold, B. Rama, and N. Weyer. Geneva: Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

- Osawe, A., and O. Ojeifo. 2019. “Unregulated Urbanization and Challenge of Environmental Security in Africa.” World Journal of Innovative Research 6 (4): 1–10.

- Ouikotan, R., J. Der Kwast, A. Mynett, and A. Afouda. 2017. “Gaps and Challenges of Flood Risk Management in West African Coastal Cities.” Proceedings of the Sixteenth World Water Congress, Cancun, Quintana Roo, Mexico, May 29–June 1.

- Owusu-Ansah, J. 2016. “The Influences of Land Use and Sanitation Infrastructure on Flooding in Kumasi, Ghana.” GeoJournal 81 (4): 555–570. doi:10.1007/s10708-015-9636-4.

- Owusu, A. 2018. “An Assessment of Urban Vegetation Abundance in Accra Metropolitan Area, Ghana: A Geospatial Approach.” Journal of Environmental Geography 11 (1–2): 37–44. doi:10.2478/jengeo-2018-0005.

- Phibbs, S., C. Kenney, C. Severinsen, J. Mitchell, and R. Hughes. 2016. “Synergising Public Health Concepts with the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction: A Conceptual Glossary.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 13 (12): 1241. doi:10.3390/ijerph13121241.

- Poku-Boansi, M., C. Amoako, J. Owusu-Ansah, and P. Cobbinah. 2020. “What the State Does but Fails: Exploring Smart Options for Urban Flood Risk Management in Informal Accra, Ghana.” City and Environment Interactions 5: 100038. doi:10.1016/j.cacint.2020.100038.

- Rehman, J., O. Sohaib, M. Asif, and B. Pradhan. 2019. “Applying Systems Thinking to Flood Disaster Management for a Sustainable Development.” International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 36: 101101. doi:10.1016/j.ijdrr.2019.101101.

- Reinhardt, J., B. Fu, and J. Balikuddembe. 2019. “Healthcare Challenges after Disasters in Lesser Developed Countries.” In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Natural Hazard Science. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Rivera, J., A. Ceesay, and A. Sillah. 2020. “Challenges to Disaster Risk Management in the Gambia: A Preliminary Investigation of the Disaster Management System’s Structure.” Progress in Disaster Science 6: 100075. doi:10.1016/j.pdisas.2020.100075.

- Salami, R., J. Von Meding, and H. Giggins. 2017. “Vulnerability of Human Settlements to Flood Risk in the Core Area of Ibadan Metropolis, Nigeria.” Jàmbá: Journal of Disaster Risk Studies 9 (1): 1–14. doi:10.4102/jamba.v9i1.371.

- Sarfo, A., and S. Karuppannan. 2020. “Application of Geospatial Technologies in the Covid-19 Fight of Ghana.” Transactions of the Indian National Academy of Engineering 5 (2): 193–204. doi:10.1007/s41403-020-00145-3.

- Satterthwaite, D., and S. Bartlett. 2017. “The Full Spectrum of Risk in Urban Centres: Changing Perceptions, Changing Priorities.” Environment and Urbanization 29 (1): 3–14. doi:10.1177/0956247817691921.

- Shi, P. 2019. Disaster Risk Science. Cham: Springer.

- Tasantab, J. 2019. “Beyond the Plan: How Land Use Control Practices Influence Flood Risk in Sekondi-Takoradi.” Jamba: Journal of Disaster Risk Studies 11 (1): 1–9.

- Tella, A., and A. Balogun. 2020. “Ensemble Fuzzy MCDM for Spatial Assessment of Flood Susceptibility in Ibadan, Nigeria.” Natural Hazards 104 (3): 2277–2306. doi:10.1007/s11069-020-04272-6.

- Tengan, C., and C. Aigbavboa. 2016. “Addressing Flood Challenges in Ghana: A Case of the Accra Metropolis.” International Conference on Infrastructure Development in Africa, Johannesburg.

- Tschakert, P., R. Sagoe, G. Ofori-Darko, and S. Codjoe. 2010. “Floods in the Sahel: An Analysis of Anomalies, Memory, and Anticipatory Learning.” Climatic Change 103 (3–4): 471–502. doi:10.1007/s10584-009-9776-y.

- Twum, K., and M. Abubakari. 2019. “Cities and Floods: A Pragmatic Insight into the Determinants of Households’ Coping Strategies to Floods in Informal Accra, Ghana.” Jàmbá: Journal of Disaster Risk Studies 11 (1): 1–14.

- Uchechi, H., E. Asemota, C. Ogar, and I. Uchendu. 2021. “Coping with COVID-19 Pandemic in Blood Transfusion Services in West Africa: The Need to Restrategize.” Hematology Transfusion and Cell Therapy 43 (2): 119–125.

- United Nations (UN). 2015a. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. New York: United Nations.

- United Nations (UN). 2015b. Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030. New York: United Nations.

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UNDESA). 2020. Impact of COVID-19 on SDG Progress: A Statistical Perspective. New York: UNDESA.

- United Nations International Strategy for Disaster Reduction (UNISDR). 2005. Hyogo Framework for Action 2005–2015: Building the Resilience of Nations and Communities to Disasters. Geneva: UNISDR.

- Wang, W., Y. Sun, and J. Wu. 2018. “Environmental Warning System Based on the DPSIR Model: A Practical and Concise Method for Environmental Assessment.” Sustainability 10 (6): 1728. doi:10.3390/su10061728.