Abstract

The way in which time is produced and consumed during everyday life has crucial implications for sustainable consumption. Social practice approaches in particular have directed attention to the intersection of personal and collective temporalities as important for the patterning of everyday consumption. This article examines the temporal dynamics of daily practice-arrangement bundles experienced in “locked down” households in Germany, Ireland, Italy, Norway, and the UK during the COVID-19 pandemic. Drawing on 97 in-depth interviews with participants in all five countries, we investigate quotidian experiences of the breaking and (re-)making of daily routines in response to the pandemic. In doing so, we explore and document the temporal processes by which daily practice-arrangement bundles become undone, reassembled, and reconfigured. Our analysis reveals the institutional ordering of temporal relations between practices in terms of how they hang together, synchronize, or compete for householders’ time. Giving particular attention to socially differentiated lockdown experiences, we analyze how disruption-induced changes to social institutions and systems of provision impact the hanging together of daily practice-arrangement bundles and the strategies employed to restructure and rebundle them in unequal ways. We further consider varied experiences in temporal reorganizations of daily life that support sustainable consumption of food and mobility and reflect on the implications of the analysis for sustainability governance.

Introduction

The way in which time is produced and consumed during everyday life has implications for resource consumption and sustainability (Rau Citation2015; Hui, Schatzki, and Shove Citation2017). Social scientific accounts suggest that time, and how time is experienced and used, is socially and spatially constituted (Ho Citation2021), shaped by political-economic developments (Adam Citation2006) and the relationship between practices constituting everyday life (Shove, Trentmann, and Wilk Citation2009). Practice theoretical approaches have made significant advances in understanding the dynamic and contextual nature of ordinary routines, including how they shape and reflect social practices and configure patterns of consumption. Time is central to practice theoretical accounts of consumption where consumption is understood as an outcome of people’s participation in the repetitive and routinized performance of social practices (Warde Citation2005). Practices are understood as socially shared ways of doing, including, for example, feeding ourselves, getting around, and fulfilling social roles, such as those relating to work and parenting. Such practices are understood as sequential and patterned, exhibiting various forms of social and temporal coordination (Blue Citation2019; Southerton Citation2013). Conceptualizing the social world as constituted by a “nexus of practices” (Hui, Schatzki, and Shove Citation2017), practice accounts emphasize changing relations and interconnections between social practices as important for understanding social change and fluctuating interpretations of normal and desirable ways of living (Rinkinen, Shove, and Marsden Citation2020).

Recent work has revealed that understanding the recursive interaction between temporalities and performances of practices is a crucial yet underexplored aspect of the organization of everyday consumption (Blue Citation2019; Southerton Citation2020). The very notion of routine implies temporality to which specific configurations of practices constituting daily life produce a rhythmic temporal experience, manifesting in a sensation of order and stability (Ehn and Löfgren Citation2009). A temporal lens reveals how connections between practices are made, become entrenched, and change over time (Shove, Trentmann, and Wilk Citation2009). Much of the research on temporalities of practice has focused on how stability is produced, including how socio-temporal patterns (e.g., of work and school) and time-saving technologies lock individuals into repetitive performances of practice, resulting in, for example, more resource-intensive consumption of energy (Jalas and Rinkinen Citation2016), increased reliance on electronic products (Jalas Citation2002), or production of more waste from food (Mattila et al. Citation2019). Others have considered how the sensation of time scarcity in modern industrialized societies associated with changes in political -economic transformations in employment and production becomes a barrier to sustainable consumption and well-being (Southerton Citation2003; Warde Citation1999; see also Schor Citation2005; Jalas Citation2006; Rau Citation2015).

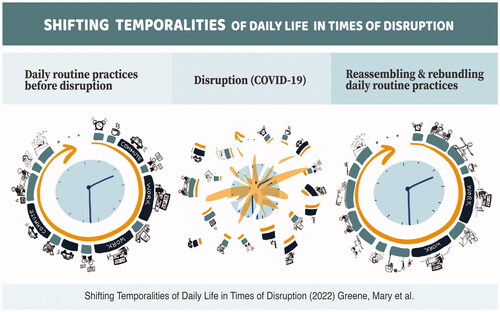

In recent years, the concept of “disruption” has gained traction as an important lens for studying the precarity of social practices, revealing how practices become unsettled and (re-)assembled when systems of provision are destabilized and taken-for-granted elements are challenged (Gibson, Head, and Carr Citation2015; Taylor et al. Citation2009; Wethal Citation2020; Chappells, Medd, and Shove Citation2011; Schäfer, Jaeger-Erben, and Bamberg Citation2012; Rinkinen Citation2013). Disruption has been conceptualized in different ways in practice research, ranging from ordinary everyday troubles (Cass et al. Citation2015) to full-blown societal breakdowns (Chappells and Trentmann Citation2018, 197). However, little work has considered disruption from the perspective of temporal dynamics of practices, including the everyday experiences of individual practitioners embodying them. An important exception is Frank Trentmann and colleagues who, working from a historical perspective, have studied different forms of disruption, in particular droughts and energy shortages, to explore how societal rhythms “unravel and are braided back together again, capturing the work that is needed to keep them going” (Trentmann Citation2009, 69; see also Shin and Trentmann Citation2019; Chappells and Trentmann Citation2018). These case studies have in common a focus on studying disruption as a dismantling of the taken-for-granted flow of life and an opportunity to analyze social practices. However, the localized cases studied to date are of a much smaller scale and magnitude compared to the macro-systemic disruptions experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic. In causing major disturbance to social institutions (e.g., of work and school) and systems of provision (e.g., supermarkets and transport systems) that underpin domestic life, the pandemic provides an important empirical moment to observe the underlying temporal constitution of social practices, including how they are embedded, reconfigured, and changed in socially varied ways.

In this article, we analyze the lockdown as a “temporary flashlight” (Trentmann Citation2009, 80) that illuminates dynamics of quotidian life normally obscured, including those relating to temporal differentiation. Focusing on daily practice-arrangement bundles implicated in household consumption, we advance understanding of socially varied temporalities of everyday life and their influence on practice performances and arrangements by contributing empirical evidence to theoretical accounts of consumption concerning (1) how (temporal) connections between practices (in practice-arrangement bundles) hang together, are formed, and change; (2) how daily routines are social differentiated, and (3) the institutional embedding of practices. Through qualitative investigation of the breaking and (re-)making of daily routines in response to the pandemic-impelled lockdown, we consider quotidian experiences of disruption, and the processes by which routines become undone, reassembled, and reconfigured. Our analysis reveals that social disruptions shed light on often hidden temporal and social dynamics constituting everyday practice-arrangement bundles, including their private and institutional regulation and degree of reflexivity. Finally, we consider the implications of these insights for research and policy on sustainable consumption. First, however, we situate our inquiry within scholarship on time, practice, and consumption.

Time, practice, and consumption

Departing from social-scientific approaches to time that frame it as a resource “spent” on different activities (a “time-as-a-resource” perspective), social practice theories view practices themselves as constituting and producing temporalities that shape the experience and performance of daily life (Schatzki Citation2009), as well as the resource implications that emerge (Shove, Trentmann, and Wilk Citation2009; Pantzar and Shove Citation2010). From this perspective, the timing of demand, and hence consumption, is “a consequence of how social practices are synchronized and sequenced” (Rinkinen, Shove, and Marsden Citation2020, 13). Emphasizing the intersection of social and personal temporalities in shaping patterns of daily consumption (Blue Citation2019; Southerton Citation2020), practice approaches stress that a discussion about time should be a discussion about the relations between practices rather than people or institutions (Pantzar and Shove Citation2010; Southerton Citation2020). Practices (and their relations), in other words, both produce and consume time (Bourdieu Citation2000; Shove, Trentmann, and Wilk Citation2009).

Practice theoretical accounts enable us to view routines as dynamic and open-ended, continuously being made and remade through performance and evolving over socio-historical time. Such accounts reveal how daily rhythms both constitute and are constituted by the collective rhythms of societies across days, weeks, and years (Walker Citation2014; Gram-Hanssen et al. Citation2020; Rinkinen, Shove, and Marsden Citation2020). Walker (Citation2014, 30) describes how societal rhythms and patterns of consumption “are essentially patterns in the routinized or habituated doing of practices in similar ways at similar times (eating, sleeping, washing, for example), and/or a functional coordination of different practices into connected sequences (waking, then dressing, then eating, then traveling, then working and so on).” These collective rhythms evolve over time and have material and environmental manifestations, such as electricity demand peaks in the mornings and evenings, rush hour-traffic jams, and increased demand for air travel during public holidays (Gram-Hanssen et al. Citation2020). With regard to the temporal paths of practices themselves (Shove et al. Citation2012), historical analyses reveal periods of gradual and rapid change in trajectories of practices (Cheng et al. Citation2007). In this context, we frame disruption as a speeding up of change in trajectories of practice evolution, that transpire as existing elements of a practice, or connections between practices, become unsettled. Thus, a practice approach necessitates a vigilant focus on the changing composition of daily life (Shove Citation2009, 18) in which the project of capturing “the temporal qualities of always changing, always-intersecting practices of daily life” and their relationship with wider social and historical dynamics is centralized (see Greene Citation2018a).

Theories of time seeking to explain rising consumption patterns during the 20th and 21st centuries generally point to transformations in economic structures and modes of production as crucial drivers of changing temporal dynamics of societies. Accounts of acceleration of time (Rosa Citation2013) describe shifts through different socio-temporal regimes, from rigid and synchronized industrial regimes to the increasingly flexible and chaotic temporal orders supposedly characterizing contemporary consumer societies. In relating the socio-temporal dynamics of societies to dynamics in consumption, scholars have linked transitions in political-economic structures and working arrangements to changing rhythyms of domestic practice arrangements and patterns of consumption. Such accounts connect with discussions of reflexive modernization (Giddens Citation1991; Beck and Beck-Gernshein Citation2002) which link dynamics in modern institutions with transformations in everyday life. For example, Juliet Schor’s analysis suggests that contemporary work-spend cycles (Schor Citation1992, Citation2005) have created a time squeeze (see also Southerton Citation2003) or time famine in daily life that acts as both a cause of, and barrier to addressing, societal problems associated with well-being and sustainability. According to these accounts, late industrial experiences of acceleration and speeding up of time produce increasingly complex dynamics of daily life as people struggle to coordinate an ever-expanding set of practices in an increasingly temporally and socially fragmented 24-hour consumer society. However, while some have argued that collective rhythms and their role in structuring personal routines seem to be giving way to more flexible and diverse temporal routines (Shove Citation2009; Southerton Citation2003), others have highlighted the enduring role of institutional rhythms in patterning practice arrangements in daily life, noting the ways that work and care practices, for example, continue to structure bundles of practices impacting domestic resource consumption (see Blue Citation2019; Greene Citation2018b; Jalas and Spurling Citation2021).

Southerton’s (Citation2003, Citation2006, Citation2020) work has been particularly informative in progressing a practice analysis of these wider political-economic dynamics and their relation with daily life. Paying particular attention to how practices are held together in practice-arrangement bundles (Schatzki Citation2016), his work pays attention to changing practice-temporal arrangements in terms of sequences and networked coordination. Practice sequences, as the temporal order in which activities and events are arranged, produce rhythms and give the tempo to everyday life (Southerton Citation2006). Within these sequences, synchronized activities, such as mealtimes, act as anchor points around which other activities are organized (Southerton Citation2020). Southerton (Citation2003) has shown how daily practices bundle together in “hot and cold spots” as individuals seek to assert “personal control” in organizing daily life in the context of increasingly harried and accelerated socio-temporal contexts. “Hot spots” refer to busy designated timeframes in which many practices are allocated and scheduled to achieve forms of network coordination, whether with family, friends, work colleagues, or other practices, in the end generating harriedness as temporalities are collectively organized. In contrast, “cold spots” refer to “free” timeframes characterized by practice experiences of temporal qualities associated with relaxation or social interaction (Southerton Citation2003). Southerton proposes that we should recognize that practices “produce their own temporal demands based on the degree to which they require coordination (or synchronization) with other people and practices” (Southerton et al. Citation2012, 343). Such temporal demands have implications for “ordering the temporal rhythms of everyday life” and structuring how resources are used and demanded. Some practices, such as eating meals with others or participating in an in-person work meeting, require coordination and synchronization between the schedules of co-participants. Others, such as reading or browsing the Internet, are less dependent on coordination (Southerton Citation2013, 344; see also Plessz and Wahlen Citation2020).

Understanding patterns of social differentiation in the lived experiences of daily practice dynamics is important for assessing how practices reproduce and change. However, despite the context-specific nature of practices and the inherent differentiation of social life, work considering variation in temporalities of daily practices remains a niche and underexplored domain.Footnote1 That said, a small but growing body of ethnographic and comparative work reveals differences both within and between societies in terms of the sequencing, coordination, and flow of daily routines. Researchers have revealed how rhythms of daily life and patterns of consumption vary over the life course, alongside changes in the presence or absence of children (Nicholls and Strengers Citation2015; Wanka Citation2020), work contexts, care roles (Pullinger et al. Citation2013), and household composition (Druckman et al. Citation2012; Smetschka et al. Citation2019). Gram-Hanssen et al. (Citation2020) reveal how temporalities and tacit knowledge concerning the appropriate frequency and performance of daily practices (such as personal washing and showering) are shaped by differences in socialization experiences and social and professional roles. Furthermore, comparative research has revealed cultural differences in terms of temporal norms and performances concerning practices of eating (Warde et al. Citation2007) and other daily practices (Hansen, Nielsen, and Wilhite Citation2016). However, despite these tentative insights, limited research to date has directly explored social differentiation and variation in temporalities of practices, especially concerning how practice-arrangement bundles become undone and restructured during moments of disruption and change.

This article seeks to respond to this gap by invesigating socially differentiated experiences and temporalities of practices in response to the COVID-19 disruption. The lens of disruption that we adopt is an explicit attempt to observe practices in flux, where the synchronicity and coordination of routines have been unsettled and the repetition of familiar patterns of practice interrupted. Observing how “regular” practices become unsettled and how alternative ways of doing daily life arise, even if only temporarily, provides insight into dynamics of stability and change in practices that could inform purposeful transformation in the future. Accordingly, we consider time and temporal experiences as an outcome of the social organization of practices in the sense that different arrangements of practices produce different rhythmic configurations and subjective experiences of daily life (Shove, Trentmann, and Wilk Citation2009). We position disruption as both a site of disintegration of consolidated practice arrangements and a site of possibility for practice innovation and restructuring, in which new practice bundles, sequences, and patterns of doing daily life may emerge. Crucial to this analysis is exploring how these processes of disintegration and restructuring play out in socially differentiated ways. Though we make no claims about the durability or impact of practice changes observed in this study, there is nevertheless an opportunity to explore how relations between practices are made and unmade when deep, widespread changes to institutional rhythms come about. Such insights are highly relevant for research and policies concerning consumption. For a summary of closures of key societal sites and services, and the dates by which they came into effect see .Footnote2

Methodology

This article explores temporalities of everyday practices under disruption through the perspective of the lives of individual practitioners and the practice-arrangement bundles constituting their daily routines. Analysis in this paper draws on 97 interviews conducted with participants in urban sites in Western Europe (Germany, Ireland, Italy, Norway, and the UK). The interviews were conducted during spring 2020, in the early months of the pandemic timeline in Europe, when many countries had implemented some degree of restriction on ordinary activity to control the spread of the virus. A shared interview guide, informed by theories of social practice and the sociology of consumption, was collaboratively designed by the research team and employed for interviewing in all countries.

Table 1. Summary of local COVID-19 restrictions.

We employed a purposive sampling approach to capture a diversity of household types that could enable exploration of social differentiated experiences of disruption. Specifically, we chose categories of differentiation that existing literature (e.g., Southerton Citation2006) suggested are associated with variation in domestic practice arrangements, including household composition (single, family, couple, shared house), employment status, and nature of work (essential worker, work from home, retired/unemployed), life stage (student, adults with children, adults without children, older-aged adults) and socio-economic status (low, middle, high). See for an overview of participant socio-demographics and contexts.

Table 2. Participant information.

Semi-structured interviews elicited dialogue on the impact of lockdown disruption on daily routines and consumption activities.Footnote3 A socio-demographic survey was employed to facilitate the exploration of social differentiation in the (re-)configuration of daily routines and practice bundles. Interviews were carried out and transcribed in the native language of interviewees and relevant extracts were translated to English for collaborative analysis. As authors, we met regularly to discuss emerging themes as we employed an iterative deductive and inductive thematic analysis format in developing and revising emerging codes. Deductive codes were derived from key concepts from the literature on time, practice, and consumption (discussed in the preceding literature-review section), which were amended and developed further in light of inductive insights. We discussed codes and their arrangement and organization into categories until agreement was obtained concerning the content and importance of themes, categories, and their interrelationships.

Undoing and reassembling household practices during COVID-19

All the moments of passage during the movements of the day…that we often take for granted…in reality, they have great value…and in fact I realized…and I think many people have actually realized…the value of these moments of passage” (Italy, male, 32 years old, single, no children, full-time working from home (WFH).

As the above interview extract suggests, the lockdown evoked a degree of discursive reflexivity among participants concerning the role of previously taken-for-granted practices and their interrelation in producing rhythm and order in daily lives. A pervasive theme across participants’ experiences in the early phases of lockdown was the weakening of collective rhythms, particularly those associated with institutionalized school and work times and the daily commute, resulting in a loss of structure and coherence to everyday activity. Lockdown provoked the disintegration of routines which involved an unsettling of connections within practice-arrangement bundles. Accompanying this disintegration process were associated attempts to restructure and reorder routines through resequencing, re-coordinating, and, in effect, “rebundling,” daily practices into new configurations.

A key finding was that cultural differences and national contexts had little influence in structuring differentiation in how practice bundles responded during the lockdown. Rather, social differentiation between households in terms of household composition, work, and life-course contexts emerged as more significant indicators shaping observed differences.

In the following sections, we present participants’ experiences concerning the disintegration and restructuring of everyday routines during the lockdown, to which we pay particular attention to social differentiation in the private and institutional regulation of daily practice-arrangement bundles. Following this, we reveal different temporal strategies employed by participants to restructure disintegrated practice-arrangement bundles during and following the lockdown. The section closes with a discussion on reflexivity in practices under disruption, and the differentiated capacities for rearranging alternative practice arrangements toward healthy and sustainable lifestyles that emerged in participants accounts.

The disintegration of routines

Bundles becoming undone at the intersection of institutional and personal temporalities

The impact of COVID-19 regime responses to the pandemic, particularly school closures and changes to working practices, revealed the role of institutional rhythms in structuring and ordering practice-arrangement bundles in daily life. Across all urban sites, interviewees described various ways in which lockdown measures affected their daily lives, through which the flow of ordinary routines was disrupted and the links sustaining practices broken. For many respondents, the shift to WFH weakened the impact of work-related rhythms on their domestic routines, contributing to a loss of structure and punctuation in everyday activity, which was expressed through a sense of ontological insecurity. The following German interviewee highlights how these changes manifested in disrupting practice-arrangement bundles constituting her morning routine, giving rise to a sense of difficulty starting and managing her day.

During the initial hard lockdown, daily life was relatively unstructured. I did not manage that well. You need structure to your day…Normally I go to work around 8. That’s all gone now, of course…Everything was a little blurred…sometimes I read the newspaper in bed or something like that, which I wouldn’t normally do during the week…I set myself certain times to work…I just acted spontaneously (Germany, female, 39 years old, single, no children, full-time WFH).

This extract provides some insight into the sense of disorientation that came with the disintegration of daily practice-arrangement bundles in the early stages of the lockdown. This experience of a “blurring” of boundaries and loss of structure to daily routines was experienced across the urban sites. However, accompanying this quite negative ontological experience of bundles becoming undone were experiences of new forms of flexibility created by shifts in the temporal-spatial arrangements of daily practice bundles related in particular to the spatial reorganization of work practices to the home-space and the cessation of the daily commute. For example, the following UK participant reflects on a positively changed rhythm of the day accompanying a shift to WFH, with feelings of being less harried expressed.

You’re not waking up with anxiety of catching public transport and worrying whether you will be in office at 9:00 or 8:30 or whatever…you can wake up at whatever time you like in the morning refreshed, sit down to work…and when you finish your work, you’re not starting a long…75-minute journey back home, but you’re at home…in the evenings…we’ve been able to use that time to…step out for a walk or run or go out biking with my daughter or scooter or things (UK, male, 39 years old, family with one child, full-time WFH).

Thus, while some participants reported a sense of stress and ontological unease associated with the sudden disintegration of practice-arrangement bundles, for others the shift to WFH and the cessation of the commute created space in the day for allocating time to other activities with different, more positive temporal qualities, such as exercising, parenting, and interacting with loved ones. These experiences are discussed further in the section entitled Consumption, Time, and Sustainability below.

As the above extracts suggest, the experiences and effects of the initial breakdown of routines played out in socially differentiated ways. Generally, those whose lives and daily practice bundles were more embedded within institutional tempos associated with work, school, and childcare activities before the lockdown reported more destructive ripple effects throughout the temporal order of their daily routines during the disruption. A sense of stress and loss was particularly pronounced among people who could not work or became unemployed during the lockdown. For example, the account of this Norwegian student who lost her part-time job as a teacher highlights the intersection of personal and institutional temporalities in shaping differentiation in disintegration experiences, which for her lead to a negative loss of structure and rhythm to the day.

I work as a substitute teacher at a school, and when the schools closed I, of course, didn’t get any work, so…there’s kind of no school, no workout, no job, so all the anchor points of everyday life kind of disappear (Norway, female, 24 years old, no children, student).

The analysis revealed significant social differentiation in participants' experiences of practice-arrangement disintegration and restructuring according to life stage, household composition, and work context. Across all countries, the presence (or absence) of children was a major factor shaping practice dynamics. Working parents with young children were likely to report experiences of significant and stressful disruption to daily lives. For example, the following Irish participant’s experience highlights the major reorganization of sequences of daily practices that accompanied the closure of schools and shift to working from a home office.

I’ve had to restructure my working day around caring and home tasks. I try some of the smaller tasks that need to be ticking over during the day like phone calls and updates online…but work that needs more concentration I need to do it at night once the kids are gone to bed (Ireland, female, 37 years old, family with two children, full-time WFH).

The experience of feeling increasingly harried and stressed with the task of juggling competing practices relating to work, childcare, and domestic life into new temporal sequences was frequently highlighted by working parents with young children. Such experiences resonate with previous research suggesting parents as particular victims of contemporary time squeeze (e.g., Southerton Citation2003). These participants generally emphasized the longer-term unfeasibility of such disintegrated practices arrangements, a sentiment that was expressed by participants with young children across the urban sites. Many respondents stressed a desire for institutional rhythms associated with work, childcare, and school to restore structure to daily life, as indicated by this German participant.

I want normality, I don’t want to stay in home office any longer. I’m really worn out. I need my children to go back to their facilities…I want my life back as it was before (Germany, female, 33 years old, family with children, reduced hours WFH)

In contrast, in some instances, retired individuals, as well as those who were unemployed or without children, expressed less significant impacts of the pandemic on the arrangement and rhythm of practices constituting their daily lives.

So, if I am honest things are actually quite similar to how they were before in terms of the running of the day and all. We still do our food shop on Thursday afternoon, still eat the same meals, maybe some more treats than normal, traveling less of course…less pressure to do things socially which has been a relief…in some ways it’s been like a big holiday. (Ireland, female, 62 years old, couple, retired)

These socially differentiated experiences suggest that practice-arrangement bundles that were less enmeshed in institutional rhythms and roles before the lockdown were less affected by the disruption. Nevertheless, in some instances, retired or older-aged individuals and younger people living alone still experienced unease from the effects of the disintegration of practices, especially those associated with social interaction and recreational activities, which often formed a larger part of their day.

Re-structuring and rebundling daily routines

Accompanying the disintegration of daily routines, participants revealed more or less widespread efforts to restructure and reorder daily practices into new practice-arrangement bundles. Strategies of (re)establishing fixed household socio-temporal routines involved re-making links between practices (including work and domestic practices) in new or modified practice arrangements. This was achieved through (1) developing new sequences of practices around key anchor practices, allocating and scheduling practices into restructured “hot and cold spots” (Southerton Citation2003) during the day, and (2) establishing new arrangements to coordinate practices with other people.

(Re-)sequencing and scheduling practices

In restructuring their routines in the new spatio-temporal contexts of the lockdown, interviewees described various ways in which they reordered and “rebundled” practices to increase alignment of “hot and cold spots” with others, including work colleagues (e.g., scheduling of Zoom meetings), family (e.g., scheduling of meal times and down time), and friends (e.g., scheduling of online hangouts, or, once restrictions were lessened, socially distant in-person walks and other outdoor get-togethers). Rescheduling routines and reestablishing anchor practices were central to the rebundling and resequencing process.

With regard to anchoring, certain practices and temporal locations and events during the day, such as mealtimes, exercise times, and bedtimes were used to organize practices in a structured and predictable fashion throughout the day. Again, the similarities in the various cultural contexts was striking. For participants across all social settings that we studied, practices of working, cooking, eating meals, and exercising outside the house became particularly important anchors around which other practices in the day were reorganized. For many respondents, new attention and focus on preparing and sharing meals were especially central. For example, the following student, sharing a flat with several others, reflected upon how meal times moved from being relatively unimportant to a core temporal anchor.

Breakfast and lunch…are normally quite insignificant meals for me…But with Corona, eating has kind of been the most exciting thing that happens in everyday life, because it’s kind of, ok guys, let’s all have breakfast together from 8 to 8:30 am, and then we eat again at 11:30, then eat again at 5pm. It’s become what you structure the entire day around, when you have these meals. (Norway, female, 25 years old, student, no children, shared flat)

This restructuring and reordering of routines around key anchoring practices were widely discussed throughout the sample. Participants sought to actively allocate and schedule practices into fixed time frames, which helped them to establish a feeling of ontological security, control, and normality amid the disruption. For many, the disruption caused “more blurred transitions…more blurred boundaries,” with efforts to reorganize the day expressed.

I guess in the beginning we tried to set up schedules, like at that time we will have lunch, at that time the (work) day is over. (Norway, female, 30 years old, no children couple, WFH full-time in the beginning, later allowed back to the office)

The extracts resonate with existing research, highlighting how intentionally synchronized activities and institutional rhythms provide temporal boundaries and act as anchor points structuring daily routines and patterns of domestic consumption (Southerton Citation2003, Citation2020). The lockdown, in driving a dramatic spatial reorganization of practices, resulted in spatial boundaries that usually structure daily life and differentiate practices between, for example, work and home, becoming increasingly blurred (see Wethal et al. Citation2022). In this context, time-related coordination became more important as participants implemented strategies to create temporal distinction while maintaining spatial continuity. These strategies ranged from separating relaxation and work spaces in the home to having a glass of wine to signal the change from work to leisure time in the same room.

Coordinating and negotiating practices

As suggested in the above extracts, setting new routines and schedules that enabled individuals to restructure their daily practices involved networked coordination and negotiation with other householders. In this respect, the process of disintegration and restructuring of routines revealed underlying dynamics of coordination essential for sustaining practice-arrangement bundles.

For many respondents, lockdown brought changes in dynamics of household composition, involving the confinement of existing householders to the space of the home for longer durations or additional dwellers moving into the household for the lockdown period. Examples of this included young adult children returning from shared, rented accommodation to the family home or relatives moving in together as support for elderly parents during the lockdown. Throughout these instances, the importance of coordination and negotiation to support the restructuring of new domestic practice arrangements and to ensure harmonious sharing of the home space was a common feature of lockdown experiences. For example, the following Irish participant discussed a process of adjustment and negotiation in relation to coordinating spatial and temporal elements of household practice in the context of adult children returning home from their university accommodation.

We kind of had to re-establish a kind of working routine between us all in the house so there was a bit of negotiation of how we could make it all work in the earlier stages of the lockdown…We made the decision to always try and eat dinner together…certain rooms could be used at certain times for working…And it was made quite clear that there would be times…where we wouldn’t want to be together. (Ireland, male, 48 years old, family with two adult children, full-time WFH)

As this account illustrates, the process of restructuring routines involved often deliberate efforts to coordinate household practices, particularly in relation to sharing space and (re-) arranging the temporal scheduling and performance of food shopping, preparation, and leisure practices. Establishing these new spatio-temporal practice-coordination arrangements often involved cautious negotiation, involving focused meetings or conversations between householders to establish a workable order for the management of household-practice bundles. This process was not always straightforward and sometimes the management of different practice demands required compromise and adjustment.

At the start, well throughout it really, we had some more formal, perhaps somewhat tense, discussions around: okay, who can use what room at what time? How can we manage the household budgets? The food shopping? How we should spend our free time? Or things like that…It wasn’t always easy and there’s definitely been adjustments and I guess compromises on both sides there. (Ireland, male, 33 years old, couple without kids, furloughed)

Consumption, time, and sustainability

The social organization of normality, and the unsustainable consumption patterns that at any given time are considered ordinary, represent a fundamental sustainability challenge (Shove Citation2003). Having unsettled familiar practices and their arrangements in various ways, lockdown encouraged reflexivity among participants concerning the temporal organization of practices in relation to how time is used and the way practices compete for their attention.

Despite some socio-demographic groups (particularly working adults with young children, as discussed above) experiencing more pronounced stress during the disintegration of routines, many interviewees contemplated positive experiences of “discovering time,” “having more time,” or feeling more agency to “organize their time more freely,” as illustrated by this German participant.

Since lockdown, I can organize my time more freely…I have more ability to determine a lot of things myself and manage my own time – I have really appreciated this. (Germany, female, 48 years old, couple without kids, full-time WFH)

Analysis suggests that such experiences of new time availability are the outcome of altered configurations of practice-arrangement bundles following lockdown, including work-related practices and their influence on the rhythm and configuration of practices at home. For example, this Norwegian interviewee describes a reorganization of practices in response to WFH measures as creating space for herself and her family to participate in practices with temporal qualities associated with well-being.

I have a lot more energy, I have had time to do exercise for the first time in five years. Because I don’t have to do the commute every day…I feel like this has been very good for me and my family…I don’t think we are the only ones to feel this way. I wish there were fewer work hours and a bit more time for other things. (Norway, female, 38 years old, family with three children, full-time WFH)

As these examples indicate, changes in the organization of practice-arrangement bundles illustrate the structuring role of work practices where rhythms of daily life are concerned. For many respondents, the new rhythms of everyday life during lockdown were experienced as a “slowing down,” a break from normally very frenzied sequences of practices comprising everyday lives. This led some participants to reflect on the overall temporal quality of the practice-arrangement bundles constituting their day, stimulating aspirations to maintain a decelerated, slower, more meaningful tempo to daily life going forward. For example, the following Italian mother reconsiders how she will plan her children’s daily schedules.

I think that I will no longer fill my children’s lives with a thousand activities because…I mean, it’s worth much more, the time spent chatting with a friend of yours than spending the afternoon running between soccer and athletics…and all these rhythms…It occurred to me that usually they never have time to just be and talk to each other, but in this period they talked with each other much more. (Italy, female, 45 years old, family with two children, full-time WFH)

These experiences resonate with accounts that connect decelerated daily life arrangements with possibilities for more meaningful and sustainable living (see Rosa Citation2013; Aldrich Citation2005). For many participants, the disintegration of practice-arrangement bundles led to an opportunity to reflect on the institutional structuring of daily arrangements and, in particular, upon relationships between demanding work routines, long commutes, and what have been labeled unhealthy or unsustainable practices, such as eating convenience-processed food and traveling long distances in a car. For example, the following Irish participant discusses the effect of the lockdown on his food practices.

I am definitely eating a lot more healthily and varied. Before [the lockdown] I definitely would have eaten out a lot…I was out of the house on the road a lot for work. I had very little time…I would have been more prone to eating fast food. Now I am cooking many more meals from scratch, even baking bread…I’m feeling a lot better for it. (Ireland, male, 33 years old, couple without children, furloughed)

Similar experiences were expressed by others across the sample whose days were constituted by busy working and childcare practices. For example, the following 33-year old single mother in Ireland working in a managerial position considers how the move to WFH has prompted her to question prelockdown work-related travel demands and has provided opportunities for more meaningful parenting, food growing, and healthier food consumption.

I mean the pandemic has shown that so much of it [travel] is unnecessary really…[pre-lockdown] I saw my daughter a lot less…I spent a lot more time in the car and on the train. But now I have so much more time in the evenings and we’ve made some big changes. I have started to get an organic veg[etable] box every week….foodwise we’re healthier than ever…like I’ve lost half a stone [seven pounds or 3.2 kilograms] and I feel really fit… I feel like the food that we’re eating is really, really local and healthy…we have planted loads of veg[etables] here in the garden as well.

Contrasting this situation with her pre-pandemic life, she extends:

Before this, like travelling up and down to Dublin for pretty pointless meetings – I would have done that twice a week…but it costs so much on your health, you’re exhausted, your child is being minded for longer than they should, and you’re eating absolute crap on the way up…you’re on the train and you get a coffee and a chocolate bar… just like to keep yourself going because you’re so tired on the way home…and essentially you’re just feeling crap…and feeling bad as a mother. (Ireland, female, 33 years old, single mother, full-time WFH)

As these extracts illustrate, the pandemic prompted many individuals to reflect on the overall time-space organization of their daily lives (Shove Citation2009). The role of work practices and the work commute emerged as particularly significant within participants’ accounts as practices that generally compete for time with many other practices deemed important for well-being and sustainability. Across the various urban sites that we studied, many interviewees expressed feeling less harried during the lockdown and experienced more time for parenting, exercising, food growing, and meal preparation. Several respondents reported signing up to local organic box schemes and taking up food cultivation, citing increased time, no commuting, and more flexible working arrangements as enabling them to allocate time for preparing meals with local, sustainable whole foods. It is important to note that participation in these practices appeared to be mediated by already existing contexts and was socially differentiated. Specifically, individuals who already had aspirations toward enacting more sustainable food and mobility practices, but had previously felt unable to do so due to competing demands from work and other practices, were likely to experience the disintegration of temporal connections between practices as an opportunity for transforming practices.

Discussion

We began this article by arguing that social variation in temporalities of practices and their arrangements in daily life is a crucial yet underexplored aspect of everyday consumption. Examining how practice-arrangement bundles constituting daily life become unsettled/destabilized and how alternative configurations arise, even if only temporarily, can provide insight into dynamics of transformation in practices that could inform purposeful transformation in the future. Following this observation, we have adopted a temporal lens to study the disintegration and restructuring of routines during disruption. In doing so, we have sought to reveal insights into how connections between practices become undone, remade, and re-entrenched and the role of such temporal dynamics in configuring consumption. In this discussion, we draw together our conceptual framing with the empirical insights to consider their implications for research and policy concerning consumption.

Interestingly, the results of this analysis suggest strong similarities across the cultural contexts studied in how practices responded during the lockdown. Categories of social class, gender, work situations, and other elements, such as life-course stage, emerged as stronger indicators of differentiation than national culture or city context. This could partly be explained by the fact that the countries and urban sites that were part of this project are all relatively affluent European consumer societies. In this respect, the findings resonate with broader discussions on the structural-institutional homogenization embedded in globalizing capitalism (Ram Citation2004; Hansen, Nielsen, and Wilhite Citation2016). In other words, the macro-infrastructural and institutional arrangements making up affluent, late-capitalist societies take many different shapes in different contexts but share fundamental similarities in how they structure socially differentiated daily experiences and consumption patterns. However, further research is needed to explore domestic practices across national cultures (see Welch, Halkier, and Keller Citation2020 for a broader account of the need to reappraise the culture in theories of practice), which, despite some recent exceptions (e.g., see also Durand-Daubin and Anderson Citation2017; Jensen et al. Citation2018; Christensen et al. Citation2020; Khalid and Razem Citation2022) remains a surprisingly neglected area of practice-based research. Furthermore, this research only studied practices under lockdown over a temporally limited timescale (the first lockdowns experienced between March and Summer 2020), and it remains unknown whether culture may play a more significant differentiating role when considering how practices and practice-arrangement bundles respond over the long term to the pandemic disruption (see also Greene et al. Citation2022 in this Special Issue). Further research is needed to better understand the longitudinal trajectories of practices under disturbance across contexts with differentiated cultural, political, and institutional responses.

As outlined in the section entitled Time, Practice and Consumption, debates exist concerning whether moves toward post-industrialization in western societies have led to deinstitutionalization of personal lives and practices (Giddens Citation1991). Previous research has highlighted the continued organization of domestic practice around the temporal structures of organizations and institutions, highlighting, for example, interconnections between practices at work and temporal experiences at home (Hochschild Citation1997; Southerton Citation2003, Citation2006; Spurling Citation2021) as well as increasingly harried experiences in daily life (Rosa Citation2013; Schor Citation2005; Southerton Citation2006). The personal temporalities of our participants’ responses to lockdown resonate strongly with these studies. Everyday domestic practices exist in complex and variously malleable sequences, spatio-temporally organized around anchoring practices that include work, childcare, and mealtimes. Our findings suggest that domestic practices are not only associated with everyday doings within the home but are influenced by people’s sense of the timetables and rhythms of externally imposed norms (e.g., working hours, school timetables), as well as broader ideologies and values of time (Liu Citation2021). The dramatic spatial reorganization and widespread changes to institutional rhythms brought about by lockdown led to losses of structure and coherence associated with these routinized institutional norms. However, in revealing socially differentiated experiences concerning the disintegration and reassembling of practice bundles, the findings have implications for considering socially varied capacities to reorganize and experiment with new practice-arrangement bundles in response to disruptions of various kinds. Recognizing multiple temporalities of the everyday thus calls for identifying how change processes (including those brought about by more targeted policy interventions – see below) play out within existing meshes of temporal power relations (e.g., Liu Citation2021).

Efforts to restructure routines and establish temporal order employed by participants, including sequencing, coordinating, and allocating practices into distinct temporal, and sometimes spatial, locations (see Wethal et al. Citation2022), resemble those found by others in contemporary flexible consumer societies (see Southerton Citation2020). Southerton and others suggest that these temporal ordering strategies are a means of responding to and alleviating pressures of an apparent time squeeze and continuous coordination challenges that characterize contemporary societies. However, the data here suggest that the establishment and adoption of structured temporal routines play an important adaptive and affective function in maintaining normality in the face of major social and personal disruption. The interaction between institutional and individual rhythms (van Tienoven, Glorieux, and Minnen Citation2017; Gram-Hanssen et al. Citation2020) and the social organization of practices in daily life is a complex phenomenon that has yet to be analyzed in depth.

Moving beyond a time-as-a-resource perspective (Shove, Trentmann, and Wilk Citation2009), the practice-based framework underpinning this investigation enlarged the descriptive possibilities of everyday practices. The analysis has highlighted how experiences of time, including having the time or feeling time scarce and harried, are temporal experiences shaped by the constitution of daily practice-arrangement bundles. Our findings support the practice-theoretical view that social organization of practices and their hanging together in everyday life shapes experiences of time. Pre-pandemic practice-arrangement bundles, locked in by time-ordering institutions, were generally experienced as busy and stressed and providing little room for alternate forms of doing consumption. The lockdown, in allowing for the disintegration of previously stable practice-arrangement bundles, enabled their reintegration in a manner that produced different temporal experiences of generally, although not always, less strained and more relaxed tempos that provided room for changing consumption. The analysis in this article demonstrates that through studying practices under disruption it is possible to identify the mechanisms by which old temporal arrangements are reconstituted and reinforced or new ones invented.

Findings concerning the importance of networked coordination for the constitution of daily practices and routines have important implications for efforts to change domestic practices in more sustainable directions. Such insights suggest that efforts to promote change should move from an emphasis on targeting individual behaviors to instead consider the intersection of daily practices within the wider sets of networked practices that make up daily routines within a broader household dynamic. Such findings contribute to a wider body of research that calls for policies that recognize how connections between practices are involved in reproducing (un)sustainable practices, and the implications that it has for designing interventions for social change (see Kuijer and Bakker Citation2015; Vihalemm, Keller, and Kiisel Citation2015; Hoolohan and Browne Citation2020; Watson et al. Citation2020). Efforts that seek to promote changes in daily practices but fail to recognize this inherent embeddedness are unlikely to provoke change at the scale, depth, and longevity needed to address socio-environmental challenges (Kuijer and Bakker Citation2015).

Data concerning socially differentiated experiences of disruption and their impact on practice-arrangement bundles further suggest significant implications for policy interventions aimed at changing practices. They suggest the importance of issues of time and temporalities of daily life for sustainable consumption-related policy (see also Aldrich Citation2005). Policy interventions, which themselves can be viewed as efforts to disrupt and reconfigure daily routines (Spurling and McMeekin Citation2015; Sahakian and Wilhite Citation2014), should be sensitive to the socially varied ways in which practices are held together and compete for time in daily lives, with degrees of flexibility to change routines differing across social groups. While all individuals have the same number of hours in the day, the ways in which practices hang or bundle together within the organization of routines offer different possibilities for conducting and rearranging daily life. Life stage, household structure, and institutional constraints have important roles in bounding people to specific practice-arrangement bundles, that encompass a mesh of work and family-related practices, the performance of which may limit their capacity for other ways of doing things (Greene Citation2017; Hoolohan, McLachlan, and Mander Citation2018). Behavior-change policies could usefully devote greater attention to the intersection of temporal demands in such various life-practice domains and their influence on resource use and consider how interventions can be tailored for people whose daily routines are especially harried and inhibited by relational and institutional commitments.

Of particular relevance for consumption-related policy are findings concerning the role of work-related practices in shaping the rhythm and order of daily life. Many participants expressed wanting to maintain work flexibility and less work-related travel to facilitate more time with family and a slower, less-stressed tempo to their daily lives. For several participants, the pandemic provided space for them to enact what they saw as more sustainable forms of consumption, such as taking up food growing, cooking local and home-prepared meals, and cycling and walking more. While such accounts suggest time scarcity associated with contemporary “work-spend” cycles (Schor Citation2005) as a root cause of unsustainable consumption, the analysis here reveals that opportunities for sustainable consumption lie in specific favorable configurations of practice-arrangement bundles in daily life. Accordingly, efforts that seek to promote sustainable consumption should consider the institutional embedding of lives and the crucial role of workplaces as time-ordering institutions shaping consumption at home. Our findings suggest that calls for more flexible working arrangements and shorter working weeks could be a promising means of achieving urgent transitions toward more sustainable consumption patterns (see Sargent et al. Citation2021).Footnote4 Institutions, such as workplaces could provide an interesting starting point for efforts to promote more sustainable consumptions at home (Muster Citation2011; Røpke Citation2004; Süßbauer and Schäfer Citation2018, Citation2019).

Conclusion

This article has argued that recognizing the temporal patterning of practices is important for understanding routine social life and the consumption that takes place within it. Recent practice theoretical accounts have stressed the relevance of considering the complex interconnectedness of time and the social organization of practices configuring consumption patterns in everyday life. Specifically, the temporal qualities of daily practices, in terms of their synchronization, sequencing, and coordination, are important for constructing everyday experiences and performances. This article has built upon and added to this work, using a moment of disruption to illuminate how temporal connections between practices relate to consumption, and are arranged and changed in socially differentiated ways.

In treating disruption as a lens through which to observe transformation in practices, our analysis has highlighted the importance of studying relations between practices for understanding how time is experienced and performed and the consumption implications that emerge. Specifically, we have highlighted the institutional structuring of daily lives as crucial for shaping how practices hang together in socially differentiated ways and the particularly central influence of workplaces as time-ordering institutions shaping consumption at home. Analyzing how routines became undone and remade during the first COVID-19 lockdown in Europe revealed that the influence of institutional time structures on domestic consumption is mediated by socio-material constraints imposed by contexts, such as life stage, household structure, and working arrangements. Findings concerning new opportunities for rearranging domestic consumption following more flexible WFH arrangements suggest a need for research and policy to more seriously consider the potential that workplace institutions offer as sites for promoting more sustainable consumption in an era of (post-) pandemic urban governance.

The findings presented in this article clearly demonstrate the need for holistic approaches to sustainable consumption that go beyond a focus on individual behavior change and take into account the social and institutional conditioning of everyday life. Further research is needed to examine the longer-term impacts of the pandemic, specifically concerning the influence of culturally-specific institutional dynamics and potentially more negative impacts of extended lockdowns, on daily practice arrangements and their enduring consumption and sustainability implications.

Ethical approval

This research received ethical approval from the Ethics Commission, School of Social Sciences, University of Geneva. Code number: CER-SDS-25-2020.

Acknowledgments

We thank the consortium of researchers and assistants involved in the project “Everyday Life in a Pandemic” for data collection, data sharing, and coordinating early collaboration and continued engagement between the multinational teams. We would also like to thank Sindre Johan Cottis Hoff and Georgina Winkler for their help in interviewing some of the participating households referenced in this article and Thea Sandnes for her assistance in finalizing the manuscript for publication.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 This omission reflects a broader neglect within recent practice research concerning differentiation in individuals’ lives and variation in practices [see Greene and Rau (Citation2018) and Gram-Hanssen (Citation2021) for discussion].

2 Most interviews were conducted online using videoconferencing tools, but in certain instances, where restrictions allowed, some were carried out in person. Informed consent was obtained for all participants.

3 The shared interview guide used across country contexts explored participants’ everyday lockdown experiences and their comparison with pre-lockdown routines. Open-ended questions prompted reflection on a range of topics, including food practices, daily mobilities, leisure, working from home, and family life. The guide ensured continuity in questioning across country contexts while also retaining space for participants to direct the conversation and emphasize salient experiences. Participants were also asked reflective future-oriented questions concerning which aspects of their lockdown practices they wanted to maintain relative to which aspects of their pre-pandemic routines they wanted to reinstate as well as what aspects of the societal environment would reinforce and support desired changes. They were also prompted to reflect on the (perceived) sustainability of their practices prior to and during the pandemic.

4 These ideas are in line with the concept of “time wealth” (Rinderspacher Citation2002) – an immaterial form of prosperity which is intended to be an alternative or supplement to material prosperity that continuously increases ecological impacts (Wiedmann et al. Citation2020).

References

- Adam, B. 2006. “Time.” Theory, Culture and Society 23 (2–3): 119–126. doi:10.1177/0263276406063779.

- Aldrich, T., ed. 2005. About Time: Speed, Society, People and the Environment. Sheffield: Greenleaf.

- Beck, U., and E. Beck-Gernshein. 2002. Individualization: Institutionalized Individualism and Its Social and Political Consequences. London: Sage.

- Blue, S. 2019. “Institutional Rhythms: Combining Practice Theory and Rhythmanalysis to Conceptualise Processes of Institutionalisation.” Time & Society 28 (3): 922–950. doi:10.1177/0961463X17702165.

- Bourdieu, P. 2000. Pascalian Meditations. Pal Alto, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Cass, N., L. Doughty, J. Faulconbridge, and L. Murray. 2015. “Ethnographies of Mobilities and Disruption.” https://cris.brighton.ac.uk/ws/portalfiles/portal/353689/WP2+Disruption+report+final+March+2015.pdf

- Chappells, H., and F. Trentmann. 2018. “Disruption in and across Time.” In Infrastructures in Practice: The Dynamics of Demand in Networked Societies, edited by E. Shove and F. Trentmann, 197–210. London: Routledge.

- Chappells, H., W. Medd, and E. Shove. 2011. “Disruption and Change: Drought and the Inconspicuous Dynamics of Garden Lives.” Social & Cultural Geography 12 (7): 701–715. doi:10.1080/14649365.2011.609944.

- Cheng, S.-L., W. Olsen, D. Southerton, and A. Warde. 2007. “The Changing Practice of Eating: Evidence from UK Time Diaries, 1975 and 2000.” The British Journal of Sociology 58 (1): 39–61. doi:10.1111/j.1468-4446.2007.00138.x.

- Christensen, T., F. Friis, S. Bettin, W. Throndsen, M. Ornetzeder, T. Skjølsvold, and M. Ryghaug. 2020. “The Role of Competences, Engagement, and Devices in Configuring the Impact of Prices in Energy Demand Response: Findings from Three Smart Energy Pilots with Households.” Energy Policy 137: 111142. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2019.111142.

- Druckman, A., I. Buck, B. Hayward, and T. Jackson. 2012. “Time, Gender and Carbon: A Study of the Carbon Implications of British Adults’ Use of Time.” Ecological Economics 84: 153–163. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2012.09.008.

- Durand-Daubin, M., and B. Anderson. 2017. “Changing Eating Practices in France and Great Britain: Evidence from Time-Use Data and Implications for Direct Energy Demand.” In Demanding Energy: Space, Time and Change, edited by A. Hui, R. Day, and G. Walker, 205–231. London: Palgrave Macmillan. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-61991-0_10.

- Ehn, B., and O. Löfgren. 2009. “Routines – Made and Unmade.” In Time, Consumption and Everyday Life: Practice, Materiality and Culture, edited by E. Shove, F. Trentmann, and R. Wilk, 17–34. Oxford: Berg.

- Gibson, C., L. Head, and C. Carr. 2015. “From Incremental Change to Radical Disjuncture: Rethinking Everyday Household Sustainability Practices as Survival Skills.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 105 (2): 416–424. doi:10.1080/00045608.2014.973008.

- Giddens, A. 1991. Modernity and Self-Identity: Self and Society in the Late Modern Age. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Gram-Hanssen, K., T. Christensen, L. Madsen, and C. do Carmo. 2020. “Sequence of Practices in Personal and Societal Rhythms – Showering as a Case.” Time & Society 29 (1): 256–281. doi:10.1177/0961463X18820749.

- Gram-Hanssen, K. 2021. “Conceptualising Ethical Consumption within Theories of Practice.” Journal of Consumer Culture 21 (3): 432–449.

- Greene, M. 2017. “Energy Biographies: Exploring the Intersections of Lives, Practices and Contexts.” PhD thesis, National University of Ireland, Galway. https://aran.library.nuigalway.ie/handle/10379/6888.

- Greene, M. 2018a. “Socio-technical Transitions and Dynamics of Everyday Life.” Global Environmental Change 52: 1–9. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2018.05.007.

- Greene, M. 2018b. “Paths, Projects and Careers of Domestic Practice: Exploring Dynamics of Demand over Biographical Time.” In Demanding Energy: Space, Time and Change, edited by A. Hui, R. Day, and G. Walker, 233–256. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Greene, M., and H. Rau. 2018. “Moving Across the Life Course: The Potential of a Biographic Approach to Researching Dynamics of Everyday Mobility Practices.” Journal of Consumer Culture 18 (1): 60–82.

- Greene, M., Volden, J. Ellsworth-Krebs E. Fox, and M. Anantharaman. 2022. “Practicing Culture: Exploring the Implications of Pre-Existing Mobility Cultures on (Post-)Pandemic Practices in Norway, Ireland, and the USA.” Sustainability: Science, Practice and Policy 18.

- Hansen, A., K. Nielsen, and H. Wilhite. 2016. “Staying Cool, Looking Good, Moving Around: Consumption, Sustainability and the ‘Rise of the South.’” Forum for Development Studies 43 (1): 5–25. doi:10.1080/08039410.2015.1134640.

- Ho, E. 2021. “Social Geography I: Time and Temporality.” Progress in Human Geography 45 (6): 1668–1677. doi:10.1177/03091325211009304.

- Hochschild, A. 1997. “When Work Becomes Home and Home Becomes Work.” California Management Review 39 (4): 79–97. doi:10.2307/41165911.

- Hoolohan, C., and A. Browne. 2020. “Design Thinking for Practice-Based Intervention: Co-Producing the Change Points Toolkit to Unlock (Un)Sustainable Practices.” Design Studies 67: 102–132. doi:10.1016/j.destud.2019.12.002.

- Hoolohan, C., C. McLachlan, and S. Mander. 2018. “Food Related Routines and Energy Policy: A Focus Group Study Examining Potential for Change in the United Kingdom.” Energy Research & Social Science 39: 93–102. doi:10.1016/j.erss.2017.10.050.

- Hui, A., T. Schatzki, and E. Shove. 2017. The Nexus of Practices Connections, Constellations and Practitioners. London: Routledge.

- Jalas, M. 2002. “A Time Use Perspective on the Materials Intensity of Consumption.” Ecological Economics 41 (1): 109–123. doi:10.1016/S0921-8009(02)00018-6.

- Jalas, M. 2006. Busy, Wise and Idle Time: A Study of the Temporalities of Consumption in the Environmental Debate. Helsinki: Helsinki School of Economics.

- Jalas, M., and J. Rinkinen. 2016. “Stacking Wood and Staying Warm: Time, Temporality and Housework around Domestic Heating Systems.” Journal of Consumer Culture 16 (1): 43–60. doi:10.1177/1469540513509639.

- Jensen, C., G. Goggins, F. Fahy, E. Grealis, E. Vadovics, A. Genus, and H. Rau. 2018. “Towards a Practice-Theoretical Classification of Sustainable Energy Consumption Initiatives: Insights from Social Scientific Energy Research in 30 European Countries.” Energy Research & Social Science 45: 297–306. doi:10.1016/j.erss.2018.06.025.

- Khalid, R., and M. Razem. 2022. “The Nexus of Gendered Practices, Energy, and Space Use: A Comparative Study of Middleclass Housing in Pakistan and Jordan.” Energy Research & Social Science 83: 102340. doi:10.1016/j.erss.2021.102340.

- Kuijer, L., and C. Bakker. 2015. “Of Chalk and Cheese: Behaviour Change and Practice Theory in Sustainable Design.” International Journal of Sustainable Engineering 8 (3): 219–230. doi:10.1080/19397038.2015.1011729.

- Liu, C. 2021. “Rethinking the Timescape of Home: Domestic Practices in Time and Space.” Progress in Human Geography 45 (2): 343–361. doi:10.1177/0309132520923138.

- Mattila, M.,. N. Mesiranta, E. Närvänen, O. Koskinen, and U.-M. Sutinen. 2019. “Dances with Potential Food Waste: Organising Temporality in Food Waste Reduction Practices.” Time & Society 28 (4): 1619–1644. doi:10.1177/0961463X18784123.

- Muster, V. 2011. “Companies Promoting Sustainable Consumption of Employees.” Journal of Consumer Policy 34 (1): 161–174. doi:10.1007/s10603-010-9143-4.

- Nicholls, L., and Y. Strengers. 2015. “Peak Demand and the ‘Family Peak’ Period in Australia: Understanding Practice (In)flexibility in Households with Children.” Energy Research & Social Science 9: 116–124. doi:10.1016/j.erss.2015.08.018.

- Pantzar, M., and E. Shove. 2010. “Temporal Rhythms as Outcomes of Social Practices: A Speculative Discussion.” Ethnologia Europaea 40 (1): 19–29.

- Plessz, M., and S. Wahlen. 2020. “All Practices Are Shared, but Some More than Others: Sharedness of Social Practices and Time-Use in Food Consumption.” Journal of Consumer Culture, Published online February 18. 146954052090714. doi:10.1177/1469540520907146.

- Pullinger, M., A. Browne, B. Anderson, and W. Medd. 2013. Patterns of Water: The Water Related Practices of Households in Southern England, and their Influence on Water Consumption and Demand Management. Final Report of the ARCC-Water/SPRG Patterns of Water Projects, Sustainable Practices Research Group. https://eprints.soton.ac.uk/359514

- Ram, U. 2004. “Glocommodification: How the Global Consumes the Local – McDonald’s in Israel.” Current Sociology 52 (1): 11–31. doi:10.1177/0011392104039311.

- Rau, H. 2015. “Time Use and Resource Consumption.” International Encyclopedia of the Social and Behavioral Sciences. 2nd ed., 373–378. Amsterdam: Elsevier. doi:10.1016/B978-0-08-097086-8.91090-0.

- Rinderspacher, J., ed. 2002. Zeitwohlstand. Ein Konzept Für Einen Anderen Wohlstand Der Nation (Time Prosperity: A Concept for a Different Prosperity of the Nation). Berlin: Nomo.

- Rinkinen, J. 2013. “Electricity Blackouts and Hybrid Systems of Provision: Users and the ‘Reflective Practice.” Energy, Sustainability and Society 3 (1): 25–35. doi:10.1186/2192-0567-3-25.

- Rinkinen, J., E. Shove, and G. Marsden. 2020. Conceptualising Demand; A Distinctive Approach to Consumption and Practice. London: Routledge.

- Røpke, I. 2004. “Work-Related Consumption Drivers and Consumption at Work.” In The Ecological Economics of Consumption, edited by L. Reisch and I. Røpke, 60–75. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Rosa, H. 2013. Social Acceleration: A New Theory of Modernity. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Sahakian, M., and H. Wilhite. 2014. “Making Practice Theory Practicable: Towards More Sustainable Forms of Consumption.” Journal of Consumer Culture 14 (1): 25–44. doi:10.1177/1469540513505607.

- Sargent, G., J. McQuoid, J. Dixon, C. Banwell, and L. Strazdins. 2021. “Flexible Work, Temporal Disruption and Implications for Health Practices: An Australian Qualitative Study.” Work, Employment and Society 35 (2): 277–295. doi:10.1177/0950017020954750.

- Schäfer, M., M. Jaeger-Erben, and S. Bamberg. 2012. “Life Events as Windows of Opportunity for Changing towards Sustainable Consumption Patterns? Results from an Intervention Study.” Journal of Consumer Policy 35 (1): 65–84. doi:10.1007/s10603-011-9181-6.

- Schatzki, T. 2009. “Timespace and the Organization of Social Life.” In Time, Consumption and Everyday Life: Practice, Materiality and Culture, edited by E. Shove, F. Trentmann, and R. Wilk, 35–48. London: Berg. doi:10.4324/9781003087236-4.

- Schatzki, T. 2016. “Practice Theory as Flat Ontology.” In Practice Theory and Research: Exploring Dynamics of Social Life, edited by G. Spaargaren, D. Weenink, and M. Lamers, 28–42. London: Routledge.

- Schor, J. 2005. “Sustainable Consumption and Worktime Reduction.” Journal of Industrial Ecology 9 (1–2): 37–50. doi:10.1162/1088198054084581.

- Schor, J. 1992. The Overworked American: The Unexpected Decline of Leisure. New York: Basic Books.

- Shin, H., and F. Trentmann. 2019. “Energy Shortages and the Politics of Time: Resilience, Redistribution and ‘Normality’ in Japan and East Germany, 1940s–1970s.” In Scarcity in the Modern World: History, Politics, Society and Sustainability, 1800–2075, edited by J. Brewer, N. Fromer, F. Albritton Jonsson, and F. Trentmann, 247–266. London: Bloomsbury.

- Shove, E. 2003. Comfort, Cleanliness and Convenience: The Social Organization of Normality. London: Berg.

- Shove, E. 2009. “Everyday Practice and the Production and Consumption of Time.” In Time, Consumption and Everyday Life: Practice, Materiality and Culture, edited by E. Shove, F. Trentmann, and R. Wilk, 17–34. Oxford: Berg.

- Shove, E., F. Trentmann, and R. Wilk, eds. 2009. Time, Consumption and Everyday Life: Practice, Materiality and Culture. Oxford: Berg.

- Shove, E., M. Pantzar, and M. Watson, eds. 2012. The Dynamics of Social Practice: Everyday life and How it Changes. London: Sage.

- Smetschka, B., D. Wiedenhofer, C. Egger, E. Haselsteiner, D. Moran, and V. Gaube. 2019. “Time Matters: The Carbon Footprint of Everyday Activities in Austria.” Ecological Economics 164: 106357. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2019.106357.

- Southerton, D. 2003. “‘Squeezing Time’: Allocating Practices, Coordinating Networks and Scheduling Society.” Time & Society 12 (1): 5–25. doi:10.1177/0961463X03012001001.

- Southerton, D. 2006. “Analysing the Temporal Organization of Daily Life: Social Constraints, Practices and Their Allocation.” Sociology 40 (3): 435–454. doi:10.1177/0038038506063668.

- Southerton, D. 2013. “Habits, Routines and Temporalities of Consumption: From Individual Behaviours to the Reproduction of Everyday Practices.” Time & Society 22 (3): 335–355. doi:10.1177/0961463X12464228.

- Southerton, D. 2020. Time, Consumption and the Coordination of Everyday Life. London: Palgrave Macmillan. doi:10.1057/978-1-349-60117-2.

- Southerton, D., C. Díaz-Méndez, and A. Warde. 2012. “Behavioural Change and the Temporal Ordering of Eating Practices: A UK – Spain Comparison.” International Journal of Sociology of Agriculture and Food 19 (1): 19–36.

- Southerton, D., W. Olsen, A. Warde, and S.-L. Cheng. 2012. “Practices and Trajectories: A Comparative Analysis of Reading in France, Norway, The Netherlands, the UK and the USA.” Journal of Consumer Culture 12 (3): 237–262. doi:10.1177/1469540512456920.

- Spurling, N. 2021. “Matters of Time: Materiality and the Changing Temporal Organisation of Everyday Energy Consumption.” Journal of Consumer Culture 21 (2): 146–163. doi:10.1177/1469540518773818.

- Spurling, N., and A. McMeekin. 2015. “Interventions in Practices: Sustainable Mobility Policies in England.” In Social Practices, Interventions and Sustainability, edited by Y. Strengers and C. Maller, 78–94. London: Routledge.

- Süßbauer, E., and M. Schäfer. 2018. “Greening the Workplace: Conceptualising Workplaces as Settings for Enabling Sustainable Consumption.” International Journal of Innovation and Sustainable Development 12 (3): 327–349. doi:10.1504/IJISD.2018.091521.

- Süßbauer, E., and M. Schäfer. 2019. “Corporate Strategies for Greening the Workplace: Findings from Sustainability-Oriented Companies in Germany.” Journal of Cleaner Production 226: 564–577. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.04.009.

- Taylor, V., H. Chappells, W. Medd, and F. Trentmann. 2009. “Drought is Normal: The Socio-Technical Evolution of Drought and Water Demand in England and Wales, 1893–2006.” Journal of Historical Geography 35 (3): 568–591. doi:10.1016/j.jhg.2008.09.004.

- Trentmann, F. 2009. “Disruption is Normal: Blackouts, Breakdowns and the Elasticity of Everyday Life.” In Time, Consumption and Everyday Life: Practice, Materiality and Culture, edited by E. Shove, F. Trentmann, and R. Wilk, 67–84. Oxford: Berg.

- van Tienoven, T., I. Glorieux, and J. Minnen. 2017. “Exploring the Stable Practices of Everyday Life: A Multi-Day Time-Diary Approach.” The Sociological Review 65 (4): 745–762. doi:10.1177/0038026116674886.

- Vihalemm, T., M. Keller, and M. Kiisel. 2015. From Intervention to Social Change: A Guide to Reshaping Everyday Practices. Farnham: Ashgate.

- Walker, G. 2014. “The Dynamics of Energy Demand: Change, Rhythm and Synchronicity.” Energy Research & Social Science 1 (1): 49–55. doi:10.1016/j.erss.2014.03.012.

- Wanka, A. 2020. “No Time to Waste – How the Social Practices of Temporal Organisation Change in the Transition from Work to Retirement.” Time & Society 29 (2): 494–517. doi:10.1177/0961463X19890985.