Abstract

Micro- and small-sized sustainable fashion businesses benefit greatly from their formal and informal networks which provide a wide variety of support and services. This exploratory study reports on the findings of a UK-based research project that investigated 27 firms in this category. We focus on four case studies comprising two designers running their own labels and two product developers who support other designers. Our analysis maps the networks of these micro- and small-sized sustainable fashion businesses. Taking an approach informed by actor-network theory (ANT), we describe human, organizational, and social media actors in formal and informal networks. We show how networks are formed and extended through supply-chain relationships, professional networks, and the serendipity of personal and online contacts. Focusing on informal networks, the article also discusses the models of working and the role that geographical (or physical) and cognitive proximity plays. The networks of sustainable businesses particularly depend on trust and shared values and help designers to understand and increase their sustainable practices.

Introduction

While the fashion industry overall is still dominated by large corporations, there are many micro- and small-sized designer-led businesses that espouse a more sustainable way of creating and using fashion and clothing. Establishing any business involves challenges such as finding finance, premises, and suitable suppliers, and many small businesses fail within the first few years. Running a business with a focus on sustainability can be even harder, as material costs are often higher and tracing supply chains and engaging with suppliers and customers about sustainability takes time. In many cases, such businesses are run by an individual designer or a very small team who rely on support networks to thrive. This article is informed by an actor-network theory (ANT) approach and analyzes such formal and informal networks. We focus on four case studies of UK-based designer-led fashion enterprises out of the 27 sustainable businesses that we studied as part of a larger project “Rethinking Fashion Design Entrepreneurship: Fostering Sustainable Practices (FSP).” We investigated the following questions: (1) How are these informal networks created and maintained? (2) What is shared within the network? (3) What is particular to sustainable businesses?

The UK’s designer-fashion sector, with an estimated £32.3 billion gross value added (GVA) before the pandemic, is largely made up of micro- and small-sized enterprises (MSEs) which are widely acknowledged for their creative influence (BFC Citation2018). This article highlights particularly micro-fashion enterprises with 0–9 employees, including innovative startup businesses and sole traders, where much creativity is found. Many designer-led MSEs pioneer alternative visions of prosperity in business and can provide a key focus for the sector’s transition to sustainability. The research project informing this article interpreted sustainability holistically across four key dimensions: environmental, social, cultural, and economic. We focused on MSE designers and founders who aimed to reconcile all of the sustainability dimensions while maintaining a viable business. This is a journey of constant learning and improvement. It often started with material choices and minimizing waste but extends across all aspects of running a business including interactions with employees, suppliers, clients, and customers. Sustainable fashion businesses seek to transform current practices of fashion, encourage sufficiency, and create long-lasting products, while creatively educating their customers and clients about sustainability values and behavior.Footnote1

As explained in the following sections, networks play a hugely important role in the success of businesses and this is well recognized in the fashion industry. We then outline the FSP project and its methodology in the next section. In the following section, we discuss four case studies – two designers with their own labels and two designers supporting other design businesses – to illustrate patterns of behavior observed across the FSP project. The presentation of the results starts with a section on networks of designers. This discussion features a map of the formal and informal networks that the designers in the FSP project were part of and describes the fluidity of membership and dynamic changes in category membership of the actors. The subsequent section discusses how networks are formed or enlarged and highlights the serendipity of collaboration and then moves on to outline the modes of working in the networks, the role that geographical (or physical) and cognitive proximity play in the working of the networks, and their role of proximity in enabling businesses to be sustainable. The penultimate section brings out insights into the conflation of human and non-human actors (in fashion), before we draw several conclusions in the final section of this article.

Networks of fashion businesses

Networks have been studied from multiple theoretical positions and practical questions. Rather than comprehensively review this literature, we select here several aspects that are relevant to our analysis of the networks of sustainable micro- and small-sized businesses. In particular, see García‐Lillo et al. (Citation2018) for a comprehensive overview of the literature on clusters and industrial districts.

Collaboration in networks

Collaborations among all agents in a network, such as suppliers, distributors, customers (often involved in co-creation initiatives), and even competitors, can be drivers of innovative and sustainable business models in fashion. More specifically, collaboration allows the creation of a supporting ecosystem (Todeschini et al. Citation2017). Collaborative design is a knowledge-sharing and knowledge-integration process (Kleinsmann, Buijs, and Valkenburg Citation2010) and it occurs in conversational turns in which everyone contributes their own expertise (McDonnell Citation2009). Collaborations across the supply-chain benefit from an alignment of business priorities (Macchion et al. Citation2015) and can contribute positively to income (Wenting, Atzema, and Frenken Citation2011), for example, through co-branding (Oeppen and Jamal Citation2014).

An important element of many networks is proximity, which has two dimensions: cognitive proximity and geographical (or physical) proximity (Balland, Belso-Martínez, and Morrison Citation2016). The notion of cognitive proximity indicates “that people sharing the same knowledge base and expertise may learn from each other” (Boschma and Ter Wal Citation2007). Knowledge is transferred between businesses in a highly dynamic process according to a study of Italian industrial districts by Camuffo and Grandinetti (Citation2011, 820):

The facilitation of inter-organizational and interpersonal relations.

The observation, aimed at imitation, of the artifacts and actions of other firms in

the district.

The mobility of human resources from an existing firm to another existing firm.

The creation of new ventures through spin-offs (i.e., the mobility of human resources from one existing firm to a newly born firm.

Industrial districts foster mutual and reciprocal cooperation which increases trust, constitutes a form of collective capital (Dei Ottati Citation1994, 531), and creates a balance between competition and collaboration. Relations between actors are socially embedded when they involve trust based on friendship, kinship, and proximity (Boschma and Ter Wal Citation2007). Co-working occurs in localized spaces where independent professionals share resources and are open to imparting their knowledge to the community. Under such circumstances, small businesses can get involved in collective innovation processes (Capdevila Citation2019).

Historically, networks were often based on geographical (or physical) proximity. Piore and Sabel’s (Citation1984) seminal work proposed that industrial districts with flexible specializations could take advantage of the latest technological advances and provide an alternative to mass production by being more adaptable in responding to demand for a variety of customized items. Their analysis focused on industrial districts with many examples drawn from the garment industry where flexibility and specialization have long been based on strong community ties and cooperation through networks of small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). A critique of Piore and Sabel’s (Citation1984) research found that flexible specializations within these industrial districts have been disrupted by globalization and affected by the destabilization of institutions (Marangoni and Solari Citation2006). Many businesses have thrived in the context of globalization because cognitive proximity enables businesses to become agents of change combining global and local knowledge (Camuffo and Grandinetti Citation2011). In addition, Guercini and Ranfagni (Citation2016) argue that conviviality both forms and maintains entrepreneurial communities. It preserves individual identities, creates social capital, and promotes greater knowledge and trust. Interactions with other firms can lead to the implementation of innovative strategies such as the development of new products or the development of better-performing business models (Guercini and Runfola Citation2012).

Collaborative networks furthermore provide for flexibility and cooperation and allowing SMEs to compete in niche markets for high-value, high-quality fashion products (Courault and Doeringer Citation2007). For the creation of new value, actors need to both learn and interact with others in their local community and to benefit from investment aimed at building communication channels beyond the local context (Bathelt, Malmberg, and Maskell Citation2004). Training and organizational support can be more fruitful if enterprise development is treated as a collective activity (Mills Citation2011).

Much of the literature on industrial districts and clusters has focused on textiles centers in Italy. While a detailed analysis of the cultural differences between Italian and UK assemblages is beyond the scope of this article, it merits noting that London has long been recognized as a creative cluster with rich ecosystems of knowledge and resources (Rieple et al. Citation2018). Innovation in the British capital is enabled by scale, diversity of demand, and cultural dynamics. The city also offers urban markets, good transport systems, and supporting institutions (Athey et al. Citation2008). London is the home of multiple national and regional fashion organizations (Virani and Banks Citation2014) and supports numerous networks that include funding bodies and universities that foster design collaboration through philanthropy, education, and consultancy (Azuma and Fernie Citation2003; Ashton Citation2006). It further is home to the recently created East London Fashion Cluster.Footnote2 These formal networks can help SMEs grow in terms of their net assets and net value (Schoonjans, Van Cauwenberge, and Vander Bauwhede Citation2013).

Collaboration in networks of sustainable fashion businesses

Sustainable clothing businesses face multiple challenges: maintaining product value, quality, and esthetics; meeting the needs of suppliers; and coping with higher material and labor costs (Curwen, Park, and Sarkar Citation2013). Personal (informal) and formal industry networks and professional connections play key roles in helping startups meet the challenges they face (Mills Citation2018; Aakko and Niinimäki Citation2018) as SMEs often lack sufficient resources and knowledge for business operations (Schoonjans, Van Cauwenberge, and Vander Bauwhede Citation2013). In particular, building relationships with manufacturers is important (Malem Citation2008). Many designers use networks of friends to source staff and produce small production runs (Athey et al. Citation2008) as the dominance of global supply chains requiring large throughput is not suitable to their needs and values (Ashton Citation2006).

Ashton (Citation2006) proposes that we think of networks as based on social relationships and common values in which knowledge and products are shared among a wide range of participants. The businesses sit in a range of nested or overlapping networks which may be clustered geographically, with access to immediate networks as well as to conduits to other networks of suppliers, customers, and collaborators – sometimes with a global reach (Athey et al. Citation2008; Ashton Citation2006). The uncertainty associated with creative businesses leads to designers developing bonds based on personality, style, or shared background rather than economic reciprocity (Gu Citation2014). Accordingly, personal relationships and shared cultural understanding play an important role.

Methodology

This article draws on actor network theory (ANT) to analyze the findings of the subsequent case studies that were carried out as part of the project “Rethinking Fashion Design Entrepreneurship: Fostering Sustainable Practices (FSP).”

Actor network theory as an approach to analyze design processes

We utilized an ANT framework to support our analysis as “it does not limit itself to human individual actors but extends the word actor – or actant – to non-human, nonindividual entities” (Latour Citation1996) and does not have preconceptions about the distance between actors, the direction of their influence, or the size of the network. This makes ANT a valuable framework for the empirical analysis of organizations (Whittle and Spicer Citation2008) as it assumes that if any actor – human, technological, or organizational – is added to or removed from the network the network will change (Doolin and Lowe Citation2002). This is an important aspect of ANT for understanding the dynamic nature of the designers’ networks.

Actor-network accounts of design tend to focus on the role of the designed object. “Expanding the project of ANT to the field of design requires mobilizing this method’s persistent ambition to account for and understand (not to replace) the objects of design, its institutions and different cultures” (Yaneva Citation2009, 280). ANT accounts also enrich the discussion of co-design, because they highlight that in a collaborative process not only the invited participant, but also unintentionally included or unexpected actors, can play an important role (Andersen et al. Citation2015). Studies of emergency situations have shown how different actors – human and technical – come together to share critical information (Potts Citation2009). “Participants in such systems engage in networked communication; they forage for information and then assemble that information in an ad-hoc, but still coordinated, manner” (Potts Citation2013, 48) moving flexibly through different media to obtain information as required.

Entwistle (Citation2016) advocates that ANT is a useful tool to examine the everyday routines and practices of fashion – how people do fashion. It entails “following the actors” (human and non-human) through observation (ethnomethodology) of the rules, practices, habits, and routines of daily life. She observed models and fashion shows, the role of the photograph, and the fashion cycle (fashion weeks, fashion buyers, and merchandizing in Selfridges department store). ANT gives equal agency to humans and devices, tools or objects, where the non-human actors support the human ones, for example websites facilitating sales.

The research project

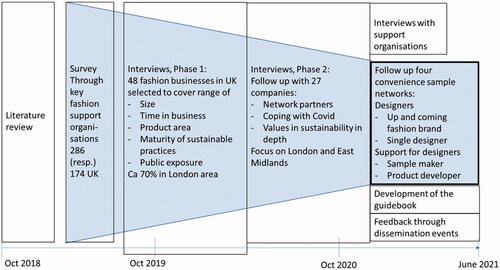

As noted above, the research reported in this article was part of a UK-based project entitled “Rethinking Fashion Design Entrepreneurship: Fostering Sustainable Practices (FSP)” (see ). Our aim was to investigate creative and business practices in design-led fashion MSEs to evidence their potential to exemplify transformation toward a more sustainable fashion industry. The research team examined the fashion-design entrepreneurs’ visions, values and capabilities, designs and operations, business models, working practices, and networks. While many of the fashion companies were centered in and around London, the authors also studied designers in the Midlands to diversify the sample outside of the capital area and to extend the project to an important region in the UK fashion (manufacturing) industry.

Micro- and small-sized fashion-designer firms are heterogenous with different attitudes toward their markets, peers, and use of external resources (Rieple et al. Citation2018). To capture this rich diversity, the project went through several phases of data gathering, as illustrated in . After an initial survey of the networks of several key support organizations (including the British Fashion Council, Center for Fashion Enterprise, and UK Fashion and Textiles Association (UKFT)), we selected 48 fashion MSEs (predominantly in London, with a few in the South East, South West, and East Midlands) for first-stage interviews between September 2019 and March 2020. Each interview was conducted by two of the researchers from the project to provide a cross-disciplinary perspective of different businesses.

The project interviewed a total of 27 fashion businesses a second time 9–12 months later, four of which were selected for this article to compare businesses in the East Midland (that did not have the support of fashion organizations) with businesses in London. The interview period overlapped with the COVID-19 outbreak. While the original intentions of the research could not anticipate the pandemic, inevitably all businesses were affected in some way by the crisis, such as a loss of clients or needing to pivot to online retailing. The authors interviewed each of the designers in the four selected case-study companies at least three times. In addition, for the case study of Love White Rabbit (LWR), in February 2021 we interviewed collaborator Claire Shell from Pin Curls Vintage (PCV), and two managers of Maker’s Yard, the Leicester design hub where PCV and LWR are located.

We transcribed all interviews and manually carried out a thematic analysis that focused on networks. The qualitative data analysis followed the three flows of actions identified by Miles and Huberman (Citation1994): data reduction, data display, and conclusion drawing. For this article, we also analyzed the data from an ANT perspective. The interviews are referenced in the discussion below by the initials of the designer and the number of the interview.

The case-study companies

This article focuses on four case studies: one firm based in London and three others in the Midlands representing typical categories of MSEs encountered in the project at varying scales – designer/founders managing their own production and service businesses supporting designers (see ).

Figure 2. Positioning of case studies (bold, larger font) in the context of other examples in the FSP project. Note: Companies in smaller bold font are mentioned in the article to illustrate additional points

Designer-led businesses do not always support their own brands but may also work for other designer-led businesses as service providers. As illustrates, there also is a middle ground where some designers produce both their own designs and work for others as a sample maker, product developer, or producer of small runs. All four case-study companies (bold, large font in ) are led by trained fashion designers who have positioned themselves differently in the market. The following case studies showcase the spectrum of business activities. We selected for each scenario a larger business with multiple employees and a sole trader. Each is trying to be sustainable in its own way. The article also refers to the companies shown in bold, (smaller font), to show the range of different firms and to illustrate salient points that did not come from the four case studies alone.

The designers

The two designers who have set up their own fashion labels oversee the entire process from design to production. Throughout the article, we will refer to the case study by the name of the business or the person, depending on whether we are making a point about the respective firm or the individual

The designer brand

Sabinna Rachimova (Sabinna) came from Vienna to London to study fashion and worked for fashion labels in Paris and London before setting up her own label in London. Sabinna is a lifestyle brand that offers sustainable products and services beyond garments. The brand has a workspace and shop in London where the firm makes and sells some of its clothing. The garments are produced in small batches from natural fibers and designs aim to make use of deadstock. Packaging is compostable as far as possible. The brand is committed to fair wages across the supply chain and offers a free repair service for its garments. Rachimova has a close relationship with her customers through her studio/shop, pop-up shows and, increasingly, communication through her website and social media. The business is situated close to other small garment brands and creative businesses in East London’s Fashion District development,Footnote3 creating an informal network of co-location in an East London cluster. She is also part of several formal design networks in the city.

The FSP project also interviewed a number of other businesses that are in geographical proximity, located across East London, an area with a long history of garment manufacturing and now being redeveloped as the Fashion District (some are shown in ). These include Black Horse Lane Atelier that produces a denim-jeans range that can be tailored to customer measurements and manufactures for other fashion brands such as Raeburn. Phoebe English is a womenswear brand showing at London Fashion Week that has been instrumental in building a local London network of designers to share knowledge and resources.

The lone designer

Ismay Mummery is the founder and owner of Boy Wonder (BW). As a former designer for High-Street brands, she spotted a gap in the market for boys’ ethical clothing that is colorful and does not use stereotypical boys wear motifs. The brand was set up to follow environmental best practice in all aspects of the business. Following circular principles, her business model includes a buy-back scheme for outgrown clothes. The garments are made of organic materials using environmentally friendly dyes and are ultimately recyclable. Patterned fabric is digitally printed to easily adjust production volumes. BW is based in a small town in the Midlands with very little textile industry so there is no local network of companies with which to collaborate. As a result, Mummery has largely relied on online connections. She is committed to local production but has experienced difficulties finding suitable suppliers in nearby Leicester that are willing to supply small-order volumes reliably at reasonable cost. She has set up a widely read blog about sustainability and the fashion industry. Unable to access funding, she crowdfunded her 2019 collection and has continued trading and initiating and running online sustainable fashion events and workshops.

Designers supporting other businesses

These two designers offer services to other businesses starting with ideas or developed designs and facilitate product development and production.

Product developer

Fazane Fox trained as a fashion designer and worked as a senior account manager for an established fashion brand for several years. When setting up her business in rural Derbyshire, she was advised by her business mentor to establish a clothing development and production company instead of setting up her own clothing label. Starting with design briefs or rough ideas from clients, who often have no background in fashion, she oversees the entire process from the original designs to product completion. Fox has built up a network of suppliers that she works with on behalf of her clients. She largely collaborates with a network of manufacturers in Portugal because the Portuguese government enforces ethical work practices. Sustainability is becoming increasingly important to her business and her clients ask for more sustainable products. She has strong ethical principles about the treatment of people and works hard on being a responsible and flexible employer by providing secure employment for both her part-time and full-time employees. Fox comes from a family of entrepreneurs and various relatives provide business advice and office space, as well as childcare.

Sample maker

Florie Struthers from LWR took a Contour Fashion BA at De Montfort University and set up a business offering pattern-cutting, small production runs, apparel sampling, and conceptual and bespoke designs. Prior to the pandemic, Struthers worked mainly for two small swimwear businesses and other small designer firms that she had met online. She had also planned to take on an apprentice with investment by her family, but she experienced a dramatic fall in orders during the COVID-19 crisis. During this period, she become involved in making scrubs for the National Health Service (NHS) in the UK. LWR is based in Makers Yard in Leicester, a historic factory building run by the Leicester City Council for creative businesses but there is little support tailored to fashion businesses.

The networks of designers

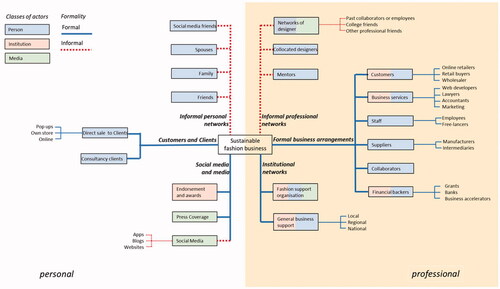

All of the respondents are part of numerous networks where they receive support and contribute to the support of peers. The following discussion focuses on networks that support designers over long periods of time rather than actant networks that are formed around a specific issue. The map in originated from summaries of the networks of the case-study designers and we supplemented it with the practices of other designers who were part of the FSP project. Not all areas are necessarily applicable in every case. For example, none of the case-study firms in this article sell through wholesale buyers which has until relatively recently been the norm in the designer-fashion sector. Most of the case-study companies excel at developing personal relationships with the people that they interact professionally. This situation makes it difficult to discern a clear distinction between personal and professional networks as a friend can become a collaborator or business services can be bartered with friends. Client and customer relationships are on the informal side of the map (indirect sales are covered under formal relationships with retail buyers) because several designers have built up personal relationships with their clients. For example, before COVID-19, Rachimova brought clothes from London to Vienna to sell to groups of regular clients in informal get-togethers (where she also received immediate feedback). Rachimova also encourages online clients to provide comments on her designs and thereby influence her design and color direction.

Figure 3. The networks of designers in the FSP research project exemplified by the four case studies.

Fluid classes of actors in networks

illustrates that the designers’ networks contain a combination of human actors, institutions, and media. As the distinction between the categories can become blurred, several boxes are marked to indicate multiple classifications. For example, the interviewees reported on getting grants from a bank as institutions but also spoke of bank managers as people. Some had individuals as backers, for example family friends. There is also a degree of overlap between media and people. For example, in the case of the fashion-support organization Make it British, the participants conflated the person running the organization, its website, and network into one actor rather than three. We nonetheless classify Make it British as an institution in the mapping in . In particular, during the COVID-19 crisis the designers interacted with colleagues in their informal networks through social media. For example, Fazane Fox joined a network of entrepreneurs in her region through a WhatsApp group and talked of them as the “WhatsApp group” as she had not yet met any of them in person. There is also, as noted above, a lot of overlap between personal and professional networks. In formal networks the designers act within the boundaries of contractual arrangements or become the recipients of other actors’ formal offerings or services, such as receiving a grant or business support from a regional council. In informal networks the actors have casual, but often long-term, relationships.

Formal networks

All four designers are part of formal business arrangements where contractual relationships determine the level of support that is provided. Both Rachimova and Fox have permanent staff who work for them as well as freelancers that they bring in for specific tasks or to ease the workload. Both have commented that their team is their greatest support but also a huge responsibility. As the quote below from Fazane Fox illustrates, this is particularly an issue for sustainable businesses that are committed to ethical treatment of staff.

If I want to grow my business, I’m going to have to take staff on which is scary…[It is] very important to me…making sure people are happy at work, well supported and paid properly…[also in] all the factories. Because the human cost is…sometimes worse than the environmental cost. A lot of time people forget that. (F1)

Struthers from LWR and Mummery from BW work on their own and commented that the step of taking on a permanent employee or an apprentice is a big one. All of the case-study businesses draw on business services, such as accounting or website development, either as a one-off service or on retainers, as well as banks. Many designers see their manufacturers or suppliers as very important actors in their networks. The suppliers understand the products and support the development process of specific garments. They also introduce designers to other suppliers if they do not have the capacity or experience to help. The fashion businesses also depend on general business support that they describe as either personal or institutional in nature.

Most of the businesses in our project have joined formal institutional networks and these networks exist in various parts of the UK. Makers Yard, where LWR is based, is a space for creative industries set up by the Leicester City Council. Fashion designers also have access to local and regional business support, which is funded through job-creation initiatives with the aim that the resident businesses will grow over time. However, as several of our respondents commented, they did not always find these services to be especially helpful as they did not want to expand but rather wanted to maintain their businesses in a steady state. For example, Struthers of LWR enjoys making clothes herself and does not wish to manage others doing the sewing.

In London, several design spaces and designers’ networks dedicated to fashion designers exist. For example, Rachimova is part of several networks including the Lone Design Club (sales support), the Trampery (studio spaces), and the Fashion Innovation Agency at London College of Fashion (special projects). These networks are also a means of accessing business support as well as for meeting other designers. Several national networks, like UKFT and Make it British have been set up in the UK and operate both online and through face-to-face events; they also lobby on behalf of the overall fashion sector. These networks are led by committed individuals who customarily built up a personal relationship with the members but proved very agile in offering their services online. In particular, during the pandemic, the designers interacted with their websites and spoke of these fashion-support organizations as websites.

Informal networks

Informal networks are often, but not exclusively, based on personal relationships. For many designers, their customers and clients are an important part of their network. Customers can provide feedback, encouragement, and inspiration. This assistance is particularly important for sustainable businesses that are usually committed to reducing waste and increasing longevity of garments. They want their customers to wear their clothing for a long time, but also to come back and buy new ones. Consequently, Sabinna, for example, has set up a repair service for her clothing. Both Sabinna and Black Horse Lane Atelier (mentioned above) run making workshops to get to know customers personally. Small businesses encounter their customers directly either online or physically if they run their own shops. Pop-up shops can be very successful, as customers often look online but like to buy in stores where they can see and feel the physical object. These retail facilities can also be a way to get quick feedback on specific garments, as customers comment on what they like and what alternatives they would have preferred, in particular around colors. Mummery writes, as mentioned above, a well-read blog but found that while she receives encouragement and press coverage through the online site, this network of readers did not translate into a significant number of orders. However, Mummery did use the blog to successfully crowdfund her collection in 2019.

For small fashion businesses, friends and particularly family members are an important part of their support network. Some of this assistance was highly practical, such as looking after children, while other relatives supported businesses financially, as the case of Fazane Fox illustrates. While BW, had recruited funders through the blog, an old friend of Mummery’s also become her lead customer.

In summary, these four fashion designers have built their own informal networks of designers and contacts throughout their careers including former university classmates, previous work associates, colleagues sharing workspaces, or people they meet through others. We discuss the significance of these relationships in further detail in the following section.

The dynamic formation of networks

While the categories of actors persist, the actual membership of the network is highly dynamic. Designers are constantly searching for and finding new collaborators and becoming part of other actors’ networks. As this section explains in more detail, actors help each other find other actors.

The supply chain as an enabler of networks

While the supply chain can become a very important network for designers, this can involve many false starts. Prospective clients frequently contacted both LWR and Fazane Fox about developing samples for them. Many of these contacts lead nowhere, as many potential clients do not think through what it means to set up a fashion business and the costs and expertise involved in doing so. Both respondents invested time in explaining basic business aspects and nurturing their clients by formulating an understanding and specifying what they want to achieve. Consequently, both Struthers and Fox have developed detailed explanations for different types of requests that they send out before engaging in a personal dialogue. Nevertheless, they have developed long-standing collaborations with client companies. Equally, finding suitable suppliers or manufacturers can be challenging for small sustainable fashion businesses, as the example of BW illustrates. However, once Mummery found her organic fabric supplier he was instrumental in introducing her to a local garment manufacturer.

Product developers like Fazane Fox find factories for their clients and Fox has many manufacturers on her books. She works with companies in Portugal that are well connected among themselves, and they pass work on to businesses they know if they do not have the technical knowhow, capability, or capacity to do the work themselves. Due to the effort involved in researching sustainable credentials, all sustainable businesses included in this project have a fairly stable manufacturing base and value relationships built up with suppliers. Sabinna has developed a small range of suppliers that pay fair wages to all of their staff including interns and produce locally (in Austria and the UK). In addition, she has hired seamstresses who sew directly for her. Small sustainable businesses also work for each other to help each other out.

The peer group of designers

University friends and former colleagues often provide practical support for designers. For example, Struthers stayed in touch with a former tutor who gave her access to production machines that he personally owned. Old friends also act as sounding boards and advisors. Rachimova is still in touch with many of her university colleagues in London and has also become a part-time lecturer which has enabled her to build up connections with other full-time and temporary staff. She brings them in for specific tasks as collaborators on one-off projects. In particular, the physical proximity to the peer group of other designers plays a crucial role in fostering collaboration for the designer brands. Fox also teaches on a part-time basis at Derby University and has benefited from both the personal connections and the professional acknowledgement associated with this role. Giving recommendations and making introductions to businesses services, staff, manufacturers, or suppliers is also an important function of these informal networks.

Unfortunately, these collaborations can take a long time to set up. Rachimova, who is considering working with a business located next door, commented in February 2021:

With collaborations you need to be a way ahead. So, we definitely have it planned out I think until almost August now and we are now starting to contact people for Christmas collaborations. (S3)

Time is required for ideas to develop as well as to negotiate the commercial aspects of a collaboration. This situation illustrates that many networks grow organically over time and are based on shared values. The relationship is markedly different when designers like Rachimova are hired as consultants by other brands. These potentially very lucrative arrangements, where the designer is in the role of a service provider, have clear deliverables.

The serendipity of collaboration

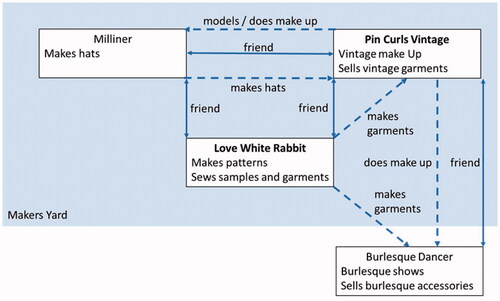

Many business arrangements are dynamic, informal, and serendipitous and networks tend to form through personal contacts. The resulting connections are a response to fluid opportunities and needs. LWR shares an office space with several lone designers, including Claire Shell from Pin Curls Vintage (PCV), who offer a range of vintage-inspired activities, including selling mid-twentieth century clothing. During the COVID-19 crisis, both Struthers and Shell struggled to maintain their businesses. When Struthers’ business was further hit by import and export complications from Brexit, she changed her business model and commissioned LWR to make replica-1940s garments using period fabric and haberdashery. Struthers’ pattern-cutting and sampling skills enabled her to adapt historic styles to larger contemporary bodies; she and Shell viewed the use of historic fabric and well-fitting clothes as a pathway to sustainability. Shell had a business background and saw the advantage of Struthers’ complementary expertise but also wanted to provide employment to her friend. She introduced LWR to a previous client who sells burlesque equipment. Physical proximity played an important role in developing their ideas as well as their businesses.

I mean we’re all really good…between us we have like a little fashion community going…I mean what we really push towards is sort of the quality of the design and the outcome. So, we have the same aesthetics in that group, so we find it very easy to tell each other what to do in their businesses and how to deal with customers and clients. (LWR1)

LWR, PCV, and a milliner are located in the same space and this proximity enables them to advise and support each other with ideas and practical suggestions. They also exchange services. Rather than having a formal contractual arrangement, they swap small services. For example, Shell did make-up for the milliner’s photoshoot and received a hat in exchange. illustrates the network that supported Struthers and LWR during the pandemic. This network is based on friendship, trust, and complementary expertise and it has enabled them to open up to each other and to bounce ideas around. Acquaintances or friends-of-friends can become collaborators when opportunity arises, and necessity demands it.

The case of BW made apparent how difficult it can be to set up collaboration without personal networks. The business is geographically isolated and for personal reasons Mummery could not easily join non-local networks. While she contacted similar businesses online for advice, she did not have the opportunity to develop the personal relationships and to gestate shared ideas. Especially for designers, serendipity is important for finding new projects and business opportunities. The situation is quite different for product developers like Fazane Fox who are often sought out by clients on the basis of personal recommendations.

Working in informal networks

Formal contractual relationships define specific interactions or create a framework for various types of services which are set up indefinitely until the aligned business run into problems, stop trading, or change their values or policies. Informal networks with often stable long-term relationships give rise to different modes of support between the members. While much of the assistance provided by informal networks can take place remotely, physical co-location plays an important part in how easily some of these relationships work.

Modes of working

Informal personal networks operate on different levels of engagement and commitment ranging from simple encouragement and advice to working together or working for each other, as discussed below, and illustrated across the four case studies.

Encouragement

For fashion designers, success and failure are very personal and this unavoidable feature makes direct encouragement very important. BW’s collection proved challenging to sell even though it had received very positive media coverage. The situation was emotionally challenging for the designer as she lives far from other designers, and this limits her ability to be in close contact with a wider community. In contrast, in a shared workspace like Maker’s Yard designers can support each other and consult on small-scale design decisions such as color combinations. Others act as sounding boards and proxies for customers. For example, Struthers of LWR and Shell of PCV realized that they were onto a good thing when they sold all their palazzo trousers to work colleagues before listing them in PCV’s online Etsy store. Conversely, if designers are not complimented on their creations, they can take this silence as a signal that the item may need improvement. This informal support takes very little time or commitment by any of the actors but it serves an important purpose in reinforcing relationships.

Recommendations

Designers who have trusted networks give each other recommendations, for example, for suitable suppliers, manufacturers, or service providers. Designers often gain business through these personal referrals and may also share information regarding poor experiences such as with particular wholesale customers.

Swapping services

As many relationships in the design field are based on personal friendships, designers try to help each other out. For example, when deadlines are looming, they might assist each other with packing. Rachimova commented on designers aiding each other with the customs declarations required since Brexit and Phoebe English initiated the pooling of surplus fabrics among a group of London designers. There is moreover a degree of expectation of mutuality. In some cases, there is a direct bartering of services or products, which gives designers access to high-quality products and services that they could not otherwise afford. This also applies to business-support services. For example, LWR commented that within her shared workspace she offered web design to other businesses while another business helped her with social media.

Working for other designers

Designers often have rather fluid working relationship with each other. This can start with a favor or informal hourly assignment and then turn into a contractual relationship, as illustrated in the section above on the serendipity of collaboration.

Collaborations

Designers also engage in joint projects with their counterparts where they operate as equal partners. For example, Rachimova was at the time of our interview engaging in a collaboration with a jewelry designer. This relationship enabled both parties to increase their exposure, to try out new ideas, and to be inspired by others. These can be one-off partnerships or long-term arrangements. For example, via the Fashion Innovation Agency at the London College of Fashion, Rachimova collaborated with digital designers RYOT studio on a project that interpreted her design concepts for an immersive digital presentation as a virtual event that was part of London Fashion Week during the pandemic.Footnote4

A significant instance of designer collaboration took place in 2020 during the COVID-19 crisis using networks for a wider purpose. Three London-based fashion designers (Holly Fulton, Phoebe English, and Bethany Williams) formed the Emergency Designer Network to create and deliver personal protective equipment – coveralls known as “scrubs” – for NHS hospitals. Using their own trusted networks, they put together teams and raised funds through crowdsourcing and donations to provide materials and to pay workers. With the assistance of industry-support organizations, both makers and factories went into production of scrubs locally and across the UK.

The importance of physical proximity

The pandemic has highlighted the importance of physical proximity. For example, the collaboration described in , has come out of a shared space, in particular a coffee area where people meet and chat. Capdevila (Citation2019) describes three different types of co-working spaces: (1) sharing a space and assets to reduce costs for individual businesses without collaboration, (2) limited and focused collaboration, and (3) the emergence of a highly innovative community that engages in collaborative practices to create new knowledge and gain new resources. During the lockdown, the designers particularly missed the shared access to machinery as well as the ability to come up with new ideas together and to bounce ideas off each other. The second point – limited and focused collaboration – was easier to achieve. While designers can be successful in working remotely and moving their consumer interactions online, the tactile nature of fashion makes some activities (such as assessing fabric properties or fit), difficult to do remotely.

Support organizations facilitate the networking of designers. Local agencies can encourage access to new networks and mobility of labor, thus having interchanges to transfer knowledge (Ashton Citation2006). Some of these associations also provide the physical space to collaborate. The case studies illustrate a stark difference between, on one hand, the highly active and well-supported shared workspaces and networks in London (where Sabinna and most of our respondents in the FSP project are based) and, on the other hand, the Midlands (where the other three case-study companies are located). London is recognized as a creative cluster with resources, knowledge, and strong local networks (Rieple et al. Citation2018, Azuma and Fernie Citation2003; Ashton Citation2006). For Rachimova, her local networks have been a hugely useful opportunity to meet other designers and to gain visibility herself, for example, to become part of the research project reported in this article. Her London networks really understand the needs of sustainable fashion designers and have been able to offer her specific support. Her studio/shop is also physically located next to those of other sustainable fashion businesses and near others in the neighborhood.

By contrast, the Midlands companies had to rely on more general networks. Maker’s Yard is a creative industry space but does not seem to offer the level of support experienced by other case studies in London. The City of Leicester, where Maker’s Yard is located, has been an industrial district for fashion production since the early decades of the nineteenth century, but more recently it has become known for fast fashion and exploitative work practices. LWR and her network deliberately distanced themselves from these practices and had to actively fight the reputation of Leicester.

Fazane Fox received general regional business support and managed to find a network of local young entrepreneurs with whom she talked about general business challenges. BW largely relied on national online resources. Physical proximity also played a part during the pandemic-induced lockdown when both Fazane Fox and Sabinna Rachimova obtained assistance from their staff while Ismay Mummery of BW became further isolated.

None of the case-study designers utilized or attended traditional business-networking events intended to introduce businesspeople to each other and to exchange experiences. Instead, they tend to receive business advice through digital networks as the following quote by Fazane Fox illustrates:

I’m not a massive fan of networking in its traditional sense where you go to all these events. I used to do that a lot with my brand and hated it but that was necessary because I needed to meet the businesswomen that were going to wear my clothes. I don’t do any of that anymore. We get business and meet contacts through the website, social media, so Instagram and Facebook. (F1)

As Gu (Citation2014) also identified in his study of creative entrepreneurs, the four case studies discussed here formed their business networks based on bonds of trust and social relationships rather than the more traditional approach based on business advantage. For our respondent companies, shared values were an important selection factor for any actors in their networks. Regarding some activities, such as collaboration, they prioritized cognitive proximity over physical proximity. However, they also enjoyed the benefits of personal interactions and belonging to a community that comes from physical proximity.

Networks enabling sustainability

The sustainable fashion businesses in the FSP project were driven by strong moral values. All were extremely disillusioned with the fashion industry in general and wanted to earn a living in a more ethical manner. Ethical working was particularly important to these sustainable businesses and the owners strived to be good employers themselves and did not want to be associated with suppliers that exploited their workers. They discussed ways of being sustainable within their informal networks and learned from each other how to increase the sustainability of their performance.

The categories of network actors in cover all of the small fashion businesses studied in the FSP project and exemplified by the four case-study businesses. However, the number and relative importance of the actors under each category are strongly influenced by the sustainable values of the business owners. All of our respondent businesses are highly committed to sustainability across the entire supply chain and the life cycle of the product.

Supply chain: The designers wanted transparency across their supply chain and to be able to trace their production processes and materials as far back as possible. All worked with a small set of carefully selected suppliers which had been able to provide information to demonstrate their ethical credentials. For example, the designers wanted to ensure that their suppliers paid fair wages or used organic materials, if possible. They also wanted to source locally, or in the case of Fazane Fox, to purchase from one location to minimize transportation. Their suppliers typically were also small businesses committed to sustainability and this led to strong and persistent personal relationships. Often, they spoke directly to the owner of their supplier company and received business advice from them.

Personal interaction with customers: The four cases and others in the FSP project looked to personal contact with their customers or clients to understand what customers wanted and how they used the garments. Based on this feedback the businesses took active steps to prolong the life of their garments by offering repair services or resale options.

The case-study designers were passionate about their businesses and business success was very personal for them. This combination of enthusiasm and vulnerability also drew in a lot of personal support from friends and family. All the parents of the case-study designers seemed highly committed to supporting their daughters through emotional, practical, or financial help.

Perhaps not inevitably, but often, striving for sustainability pushes up the cost of products, but working together by sharing knowledge and resources and/or exchanging services enabled the businesses to stay competitive. Using up each other’s spare resources also minimizes waste. Bartering services was another important way of making sustainable fashion affordable for more customers. Forming networks and collaborating also generates opportunities for small sustainable fashion MSEs businesses, for example, by running joint pop-up shops or workshops.

Conflation of human and nonhuman actors

ANT gives equal agency to human and non-human actors, such as websites, institutions, and garments. These non-human actors promote and enable activities by human actors and facilitate the creation of networks. However, distinguishing between, on one hand, human actors and, on the other hand, business and institutions can be ambiguous in the case of the networks of small sustainable fashion businesses. For example, institutions, such as Make it British are run by a person, who also runs an online platform, to help fashion businesses to find human suppliers. In pre-pandemic times the individual small businesses would also connect physically in face-to-face events and trade fairs and talk to the online platform’s owner directly. The distinction between person and online platform can thus become blurred and the two can be conflated.

The case-study companies also referred to the members of their networks both as the businesses and as the people. For example, the customers and suppliers of Fazane Fox interacted with the business – Fox and her employees – while some had only personal relationships with Fox. In talking about other businesses, the interviewees switched between the name of people and the name of businesses (e.g., Struthers talked about working for “Claire” or for Pin Curl Vintage depending on the context). This conflation of business and person is highly prevalent in the designer-fashion sector where the business and brand name are very often the personal name of the designer. The merging also masks the contribution of design and production teams behind the culture of the “genius designer.” In contrast, within the case-study businesses, both Fox and Rachimova were deeply concerned about the well-being of their employees, especially during the pandemic and listed them among their most important network members.

Conflation between the person and the role is an important element of relationships within formal networks both in employer-employee relationships and in collaborations. The blurring between the personal and the professional was also evident in the bartering of services, as illustrated by PCV receiving a hat as payment. It was not clear whether this was a friend helping out and receiving a gift or an in-kind business exchange.

The businesses constructed strong personal relationships with their suppliers which tended to blur the boundary between the person and the organization. For most of the designers that we studied in the FSB project, it was important to trace the supply chain of their materials back to their sources to ensure that they had been produced sustainability. Some designers depended on the word of their immediate supplier while others traced the materials further back, but all had to take some assertions on trust. This trust was built through knowing the suppliers personally, even though not all were local, and enabled the case-study businesses to establish a small base of trusted suppliers. To cope with the ebbs and flows of business, the companies also depended on their employees and suppliers to work overtime, if necessary.

Conclusion

This article describes the networks of micro- and small-sized businesses in the fashion-design industry. While the map in is based on the 27 companies that we studied in the FSB project, most of our insights are drawn from four main case-study companies. However, many of the observations could apply to fashion micro- and small-sized businesses in general. The high standards for sustainability added a burden that increased the need for support from the designers’ networks. Taking an ANT-informed approach, we analyzed support by other designers, businesses, and organizations, but also websites and social media, which were offered by the businesses as part of their support networks. We show how even small businesses depend on large and heterogenous networks. While some of these relationships are formal, many of them are between network partners and are deeply personal to the extent that the person and the business or organization of which they are part become conflated.

Physical proximity is important for the designers to get to know each other and to gestate ideas over time. Co-location in shared studio spaces and physical neighborhoods is an important enabler of collaboration. This particularly applies in London which has a high concentration of creative clusters centered around universities and their fashion alumni as well as specialized support organizations that understand the needs of fashion businesses and can advise and publicize the designers. In the absence of connections provided by a local fashion cluster, the designers in the Midlands tend to depend on personal informal networks or contacts they make online. Regardless of specific geographic location, networks provide important sources of both emotional and practical support.

The dynamic nature of networks is an important enabler of success and resilience for the designers. The people the case-study designers chose to interact with were those they aligned with cognitively and with whom they shared an outlook and values. In times of change or difficulty, such as during the pandemic, new collaborations could thrive based on recent physical proximity and pre-existing personal networks, irrespective of size. Regardless of the circumstances, networks, formal and informal, provide vital support for micro- and small-sized business without which few businesses could thrive. In particular knowledge about sustainability and ways to operate sustainably are shared through such networks.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all the designers who contributed their time, enthusiasm, and creativity to the project. Our particular thanks go to our case-study companies, Sabinna Rachimova from Sabinna, Ismay Mummery from BoyWonder, Fazane Fox from Fazane Fox, Florie Struthers from Love White Rabbit and her collaborator, Claire Shell, from Pin Curls Vintage (PCV).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 See case studies at Fostering Sustainable Practices (http://www.sustainable-fashion.com).

3 This initiative was founded in 2017 to support the regeneration of the creative fashion industry in East London and supported by the London College of Fashion (University of the Arts London) and five London boroughs. See https://www.fashion-district.co.uk.

References

- Aakko, M., and K. Niinimäki. 2018. “Fashion Designers as Entrepreneurs: Challenges and Advantages of Micro-Size Companies.” Fashion Practice 10 (3): 354–380. doi:10.1080/17569370.2018.1507148.

- Andersen, L., P. Danholt, K. Halskov, N. Hansen, and P. Lauritsen. 2015. “Participation as a Matter of Concern in Participatory Design.” CoDesign 11 (3–4): 250–261. doi:10.1080/15710882.2015.1081246.

- Ashton, P. 2006. “Fashion Occupational Communities – A Market‐as‐Network Approach.” Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management 10 (2): 181–194. doi:10.1108/13612020610667496.

- Athey, G., M. Nathan, C. Webber, and S. Mahroum. 2008. “Innovation and the City.” Innovation 10 (2–3): 156–169. doi:10.5172/impp.453.10.2-3.156.

- Azuma, N., and J. Fernie. 2003. “Fashion in the Globalized World and the Role of Virtual Networks in Intrinsic Fashion Design.” Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management 7 (4): 413–427. doi:10.1108/13612020310496994.

- Balland, P., J. Belso-Martínez, and A. Morrison. 2016. “The Dynamics of Technical and Business Knowledge Networks in Industrial Clusters: Embeddedness, Status, or Proximity?” Economic Geography 92 (1): 35–60. doi:10.1080/00130095.2015.1094370.

- Bathelt, H., A. Malmberg, and P. Maskell. 2004. “Clusters and Knowledge: Local Buzz, Global Pipelines and the Process of Knowledge Creation.” Progress in Human Geography 28 (1): 31–56. doi:10.1191/0309132504ph469oa.

- Boschma, R., and A. Ter Wal. 2007. “Knowledge Networks and Innovative Performance in an Industrial District: The Case of a Footwear District in the South of Italy.” Industry & Innovation 14 (2): 177–199. doi:10.1080/13662710701253441.

- British Fashion Council (BFC). 2018. London Fashion Week September 2018 Facts and Figures. London: BFC. https://www.britishfashioncouncil.co.uk/pressreleases/London-Fashion-Week-September-2018-Facts-and-Figures

- Camuffo, A., and R. Grandinetti. 2011. “Italian Industrial Districts as Cognitive Systems: Are They Still Reproducible?” Entrepreneurship & Regional Development 23 (9–10): 815–852. doi:10.1080/08985626.2011.577815.

- Capdevila, I. 2019. “Joining a Collaborative Space: Is It Really a Better Place to Work?” Journal of Business Strategy 40 (2): 14–21. doi:10.1108/JBS-09-2017-0140.

- Courault, B., and R. Doeringer. 2007. “From Hierarchical Districts to Collaborative Networks: The Transformation of the French Apparel Industry.” Socio-Economic Review 6 (2): 261–282. doi:10.1093/ser/mwm008.

- Curwen, L., J. Park, and A. Sarkar. 2013. “Challenges and Solutions of Sustainable Apparel Product Development: A Case Study of Eileen Fisher.” Clothing and Textiles Research Journal 31 (1): 32–47. doi:10.1177/0887302X12472724.

- Dei Ottati, G. 1994. “Trust, Interlinking Transactions and Credit in the Industrial District.” Cambridge Journal of Economics 18 (6): 529–546. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24231830. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.cje.a035289.

- Doolin, B., and A. Lowe. 2002. “To Reveal is to Critique: Actor-Network Theory and Critical Information Systems Research.” Journal of Information Technology 17 (2): 69–78. doi:10.1080/02683960210145986.

- Entwistle, J. 2016. “Bruno Latour: Actor-Network Theory and Fashion.” In Thinking through Fashion, edited by A. Rocamora and A. Smelik, 269–284. London: I.B. Taurus.

- García‐Lillo, F., E. Claver‐Cortés, B. Marco‐Lajara, M. Úbeda‐García, and P. Seva‐Larrosa. 2018. “On Clusters and Industrial Districts: A Literature Review Using Bibliometrics Methods.” Papers in Regional Science 97 (4): 835–861. doi:10.1111/pirs.12291.

- Gu, X. 2014. “Developing Entrepreneur Networks in the Creative Industries – A Case Study of Independent Designer Fashion in Manchester.” In Handbook of Research on Small Business and Entrepreneurship, edited by E. Chell and M. Karatas-Ozkan, 358–373. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Guercini, S., and S. Ranfagni. 2016. “Conviviality Behavior in Entrepreneurial Communities and Business Networks.” Journal of Business Research 69 (2): 770–776. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.07.013.

- Guercini, S., and A. Runfola. 2012. “Relational Paths in Business Network Dynamics: Evidence from the Fashion Industry.” Industrial Marketing Management 41 (5): 807–815. doi:10.1016/j.indmarman.2012.06.006.

- Kleinsmann, M., J. Buijs, and R. Valkenburg. 2010. “Understanding the Complexity of Knowledge Integration in Collaborative New Product Development Teams: A Case Study.” Journal of Engineering and Technology Management 27 (1–2): 20–32. doi:10.1016/j.jengtecman.2010.03.003.

- Latour, B. 1996. “On Actor-Network Theory: A Few Clarifications.” Soziale Welt 47: 369–381.

- Macchion, L., A. Moretto, F. Caniato, M. Caridi, P. Danese, and A. Vinelli. 2015. “Production and Supply Network Strategies within the Fashion Industry.” International Journal of Production Economics 163: 173–188. doi:10.1016/j.ijpe.2014.09.006.

- Malem, W. 2008. “Fashion Designers as Business: London.” Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management 12 (3): 398–414. doi:10.1108/13612020810889335.

- Marangoni, G., and S. Solari. 2006. “Flexible Specialisation 20 Years On: How the ‘Good’ Industrial Districts in Italy Have Lost Their Momentum.” Competition & Change 10 (1): 73–87. doi:10.1179/102452906X92019.

- McDonnell, J. 2009. “Collaborative Negotiation in Design: A Study of Design Conversations between Architect and Building Users.” CoDesign 5 (1): 35–50. doi:10.1080/15710880802492862.

- Miles, M., and A. Huberman. 1994. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Mills, C. 2011. “Enterprise Orientations: A Framework for Making Sense of Fashion Sector Start‐up.” International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research 17 (3): 245–271. doi:10.1108/13552551111130709.

- Mills, C. 2018. “Grappling with the Challenges of Start-Up in the Designer Fashion Industry in a Small Economy: How Social Capital Articulates with Strategies in Practice.” In Creating Entrepreneurial Space: Talking through Multi-Voices, Reflections on Emerging Debates, edited by D. Higgins, P. Jones, and P. McGowan, 129–155. Bingley: Emerald. doi:10.1108/S2040-724620189A.

- Oeppen, J., and A. Jamal. 2014. “Collaborating for Success: Managerial Perspectives on Co-Branding Strategies in the Fashion Industry.” Journal of Marketing Management 30 (9–10): 925–948. doi:10.1080/0267257X.2014.934905.

- Piore, M., and C. Sabel. 1984. The Second Industrial Divide: Possibilities for Prosperity. New York: Basic Books.

- Potts, L. 2009. “Using Actor-Network Theory to Trace and Improve Multimodal Communication Design.” Technical Communication Quarterly 18 (3): 281–301. doi:10.1080/10572250902941812.

- Potts, L. 2013. Social Media in Disaster Response: How Experience Architects Can Build for Participation. New York: Routledge.

- Rieple, A., J. Gander, P. Pisano, A. Haberberg, and E. Longstaff. 2018. “Accessing the Creative Ecosystem: Evidence from UK Fashion Design Micro Enterprises.” In Entrepreneurial Ecosystems and the Diffusion of Startups, edited by E. Carayannis, B. Dagnino, S. Alvarez, and R Faraci, 117–138. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar. doi:10.4337/9781784710064.

- Schoonjans, B., P. Van Cauwenberge, and H. Vander Bauwhede. 2013. “Formal Business Networking and SME Growth.” Small Business Economics 41 (1): 169–181. doi:10.1007/s11187-011-9408-6.

- Todeschini, B., M. Cortimiglia, D. Callegaro-de-Menezes, and A. Ghezzi. 2017. “Innovative and Sustainable Business Models in the Fashion Industry: Entrepreneurial Drivers, Opportunities, and Challenges.” Business Horizons 60 (6): 759–770. doi:10.1016/j.bushor.2017.07.003.

- Virani, T., and M. Banks. 2014. “Profiling Business Support Provision for Small, Medium and Micro-sized Enterprises in London’s Fashion Sector.” Creativeworks London Working Papers. http://www.creativeworkslondon.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/PWK-Working-Paper-9-SEO.pdf

- Wenting, R., O. Atzema, and K. Frenken. 2011. “Urban Amenities and Agglomeration Economies? The Locational Behaviour and Economic Success of Dutch Fashion Design Entrepreneurs.” Urban Studies 48 (7): 1333–1352. doi:10.1177/0042098010375992.

- Whittle, A., and A. Spicer. 2008. “Is Actor Network Theory Critique?” Organization Studies 29 (4): 611–629. doi:10.1177/0170840607082223.

- Yaneva, A. 2009. “Making the Social Hold: Towards an Actor-Network Theory of Design.” Design and Culture 1 (3): 273–288. doi:10.1080/17547075.2009.11643291.