Abstract

The overcoming of outdated values embedded within the system of fashion requires a complete revamping of its very foundation toward a concept of cultural sustainability and preservation of material culture. Discussion about cultural sustainability and heritage preservation requires conservation and regeneration of the cultural beliefs and symbolic meanings embedded within the traditional processes and practices of craft. With meaning tied to place, and the evolution of ideas, attitudes, and practices, local knowledge of traditional handcrafts can be considered as a sustainable repository of culture. The purpose of this study is to interpret the most developed craft-based strategies in the field of fashion to promote positive and sustainable change and to disassociate from the practice of cultural appropriation. Through the presentation of selected case studies in the fields of fashion, design, and craftsmanship, this article provides an interpretative model for cultural sustainability through traditional craft. With a focus on the incorporation and valorization of material practices and knowledge in fashion, the proposition for design to act as a promoter of innovative processes and the nurturing and retaining of craft can ensue. This speculative model is built on case studies on cultural sustainability through traditional craft. It is focused on experimentation, innovation, and sustainability through the design and creative process expressed through cultural heritage strategies. The result is a range of possible outcomes, aligned with existing craft practices, that highlight opportunities for design to support traditional craft through innovative processes while maintaining their embedded codes.

Cultural sustainability: an introduction

The United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) (Citation2015) describes culture as a powerful driver for development that has communitywide social, economic, and environmental impacts. Related to this point, the FashionSEEDS project (Williams et al. Citation2019) defines cultural sustainability as

Tolerant systems that recognise and cultivate diversity. This includes diversity in the fashion and sustainability discourse to reflect a range of communities, locations, and belief systems. It includes the use of various strategies to preserve First Nations cultural heritage, beliefs, practices, and histories. It seeks to safeguard the existence of these communities in ways that honour their integrity.

Cultural sustainability is thus a response to a shift in our values that seeks to rectify the biases of the past by recognizing the importance of diversity, inclusion, representation, and respect for other people, communities, and their representative material cultures, as well as the role that craftsmanship plays in expressing traditional culture.

Originally, the term sustainability was conveyed predominately from an environmental perspective. The expansion of the concept of sustainability in “sustainable development” has been ongoing since publication of the Brundtland Commission’s report (WCED Citation1987) introducing three dimensions: economic growth, social inclusion, and environmental balance. The inclusion of a social and economic dimension in this framework was further validated in 1992 in the United Nation’s Agenda 21. In the same year, the Swiss project “Monitoring of Sustainable Development (MONET)” outlined a paradigm for sustainable development that incorporated three pillars, one each for environmental conservation, economic growth, and social equity (Keiner Citation2005a, Citation2005b). In 1994, the World Bank’s “capital stocks” model of sustainable development consolidated this paradigm by evaluating society as equal to the economy and the environment. This approach was based on the banking theory of ecological capital, that if you can live off the interest of your investment, you can maintain prosperity.

This formulation was further amended in 2001 by UNESCO’s Universal Declaration on Cultural Diversity by adding cultural diversity as an integral component in the form of a bridge connecting the other three pillars, rather than adding a pillar in its own right. The organization explained cultural diversity as a dynamic process within which cultural change can best be managed with intercultural dialogue and sensitivity to cultural contexts. However, it was not until 2010 that the United Cities and Local Governments (UCLG) published a policy statement arguing for culture as the fourth pillar of sustainable development. Axelsson, Angelstam, and Degerman (Citation2013) view the long debate about the need for the inclusion of a fourth pillar that expands upon previous expressions of social inclusion as encompassing a cultural perspective. Decoupling culture from the social pillar demonstrated a specific focus on cultural diversity as a set of shared values within a specific local community that are considered important levers to drive sustainable development and are on par with the environment, economy, and society, as shown by its promotion by the UCLG and adoption by the United Nations. The introduction of this fourth pillar has had profound implications when analyzed in a fashion context, particularly in relation to traditional craftsmanship.

As Boța-Moisin (Citation2017) argues, cultural sustainability in the fashion and interrelated textile field means supporting and sharing knowledge of traditional know-how, competencies, and skills of fashion and textile cultures with future generations. Therefore, cultural sustainability in fashion requires that we address the history of cultural appropriation (Kangas, Nancy, and Beukelaer Citation2017). Central to the problem of appropriation are the issues of ownership, authorship, respect, and power imbalances with brands too often utilizing unique cultural expressions and processes for commercial gain, sometimes in a disrespectful manner (Anderson Citation2010; Vezina 2019). Susan Scafidi, an expert in fashion law and author of Who Owns Culture? (2015), cites cultural appropriation as one of the main reasons why some cultures and their material representations are threatened. She sees the commercial exploitation of traditional craft as having devastating implications for indigenous communities, with tradition distributed by brands without gratitude or economic benefit to the original creators.

Scafidi (Citation2015) cites the vast gulf between cultural appropriation, cultural appreciation, and cultural exchange. First, cultural appropriation is commonly mentioned as contributing to the loss and devaluation of cultural heritage and its material representation through unsolicited use and misuse. Second, cultural appreciation generally refers to the admiration for “another” culture and an interest in learning about it. Finally, cultural exchange is a sharing of skills and knowledge. UNESCO’s report on Intangible Cultural Heritage (2018) documents hundreds of different forms of intangible cultural heritage from around the world. The interactive listing offers insight into the major contributing factors to the loss of tradition worldwide, citing cultural appropriation as one of many threats to continued viability.

There are currently few to no legal protections in place to safeguard indigenous material culture, allowing brands to continue to raid cultural heritage as a source of inspiration, despite being publicly shamed in social media for doing so. With multiple indigenous communities in the process of trying to expand upon intellectual property law to include collective material culture under its protection, the time will soon pass when a designer can dip into another culture for inspiration and produce designs without recompense to the community that inspired their work. Despite the progress of several initiatives including the Maasai Intellectual Property Initiative, the National Mayan Weavers Movement, the Mexican government’s public commitment to developing legislation, the Lao Traditional Arts and Ethnology Centre’s efforts, the overarching work of the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO), and the Cultural Intellectual Property Rights Initiative (CIPRI), most protections remain aspirational. Collectively these proposals seek to safeguard the traditional knowledge and the custodians of traditional cultural expressions with protection against misappropriation under law. However, until these legal protections are implemented within comprehensive frameworks, brands will continue to “copy and borrow” indigenous material culture with impunity (Vézina Citation2019).

Multiple examples of blatant cultural appropriation litter Western fashion history, from Victoria’s Secret’s 2012 fashion show with Karlie Kloss strutting down the catwalk wearing a traditional First Nations war bonnet and turquoise jewelery to Carolina Herrera’s Resort 2020 collection (Friedman Citation2019). Herrera’s collection, naïvely intended as a homage to Latin America, resulted in the Mexican government accusing her of plagiarizing several indigenous communities and setting in motion the development of legal protections for the country’s intangible cultural heritage. Isabel Marant’s Spring/Summer 2015 collection, which copied a traditional Mexican blouse from Oaxaca, resulted in the designer being sued in a French court (Larson Citation2015). Dior’s direct copy of a traditional Romanian vest resulted in the launch of an online platform called Bihor Couture selling original Romanian artisan-made versions while publicly shaming Dior for the theft (Bihor Couture Citation2018). This is a long conversation, punctuated with periods of dormancy and outrage, reminiscent as it is of colonialism, fueled anew with activism in defense of threatened tribal peoples and traditions from around the world.

A virtuous example of cultural appreciation followed by cultural exchange, in line with Scafidi’s arguement, is represented by Oskar Metsavaht, the Creative Director of Osklen and the Ashaninka collection. Metsavaht collaborated with the Ashaninka people from the rainforests of Amazonia for his Spring 2016 collection. The collection was a collaboration and an exchange, with Metsavaht working directly with elders from the community to ensure that no symbols, colors, or patterns were utilized inappropriately. He developed a logo for community use and effectively treated the relationship as an artistic collaboration, with the tribe benefitting from royalties from every sale and their accreditation in all communication as the source of inspiration (Quartz Citation2015). Metsavaht showed that by using the vehicles of traceability, transparency, provenance, and authorship, material culture and craftsmanship can be reclaimed an honored.

In the following sections, we discuss how design accesses craft culture through a knowledge exchange of practices and techniques in order to reconfigure processes and to encode different meanings into new narratives rooted in the appreciation of a specific culture.

Intangible cultural heritage in the fashion system

Given the challenges of craft retention, a design-oriented approach offers a strategic option for solution-oriented implementation of artisan knowledge. This strategy would redefine directions in support of the development of territory and community through the conservation of culture. Artisans would be provided with the tools for self-evaluation, enabling them to better articulate the intrinsic qualities of their work. A methodological process of product development can be designed through successive phases of knowledge, reflection, activation, and preservation of specific know-how, thereby informing the continuous enhancement of craft-knowledge from a design-oriented perspective. As Fry (Citation2009) argues, design participates in the planning of culture through the introduction of an object into the world. Therefore, the history of designed objects is the history of culture. Design is never culturally neutral, but always transports socio-cultural values, with the value dependent upon the “the symbolic, emotional and identification of meaning it embodies” (Rullani Citation2004, 13). According to Oppenheimer (Citation2019), craft is not a finished product, or even a set of refined technical skills, but a means of understanding the material world. By producing handicrafts that strengthen and valorize local culture, meaning transcends simple income generation, allowing people to act in line with their values and to create new means to overcome their circumstances. This concept is called platforming by Fry (Citation2009) and described as a strategy that maintains existing and traditional economic activity and work culture, while building a new direction with new products.

LVMH, one of the largest luxury conglomerates in the world with over seventy brands to its name, understands the need to maintain the renowned French metiers that luxury fashion relies upon as a means to retain and retrain young people for the longevity of luxury craftsmanship. For the company, preserving know-how has become an increasing concern (Hope Citation2015). In an effort to maintain tradition, LVMH developed an initiative called L’institut des Métiers d’Excellence (IME) (The Institute for the Professions of Excellence) in 2014. The IME provides training for young people to learn these skilled trades while providing long-term investment and support for their most valued suppliers (LVMH Citationn.d.). The loss of traditional craft skills in France has been magnified by the loss of global craftsmanship, which is disparate, splintered, and exacerbated by modernization and globalization (Murphy Citation2018).

Other examples of retention exist in the educational space, with some universities fostering collaborations between students and artisanal communities. While these examples are limited, they represent a realization of the importance of retaining these endangered crafts. One example is Officina Borbonese which is a collaboration between The New School’s Parsons Paris campus and the craft cooperative Su Trobasciu in Mogoro, Italy. This small Sardinian village plays host to an innovative project that reinterprets the iconic tapestries and carpets typical of the region. A specific initiative called Savoy Faire focuses on sustainability by enhancing local culture and operating a traceable and transparent supply chain. The idea was founded on the identity and values of the Borbonese and reinterpreted through the material culture of Sardinian craftswomen and fashion-design students. This venture is further supported by students from programs in strategic design and management and they created the marketing and communication strategy for a Fall/Winter 2021 capsule collection.

Handcraft and artisan production is estimated to be the second largest employer in the developing world (Alliance for Artisan Enterprise Citation2016), with women representing the overwhelming majority of garment workers and artisans. Globally, the artisan market is valued at approximately US$34 billion with 65% of this activity taking place in developing economies (Kerry Citation2015). UNESCO (Citation2018) lists a number of specific threats to the retention of tradition with both globalization and mass production featuring prominently in addition to the higher costs and the investment of time required to perform hand-crafted labor, the inability of artisans to adapt to market needs, the environmental pressures, and the loss of access to raw materials. A further factor is the lack of interest from the next generation to learn the requisite skills. Global craftsmanship does not enjoy the benefits of one of the world’s largest luxury conglomerates to protect it and to ensure its longevity, retention, and relevance (Black Citation2016). Moreover, the cultural and creative sectors have been disproportionately affected by the global pandemic (OECD Citation2020).

Research methodology: cultural sustainability through craft

In accordance with the definition of cultural sustainability, material culture consists of practices, techniques, and processes that are curated constantly by human capital. In many cases that capital has enabled the preservation of unique and distinctive knowledge and expertise within specific territorial contexts (Faro Convention Citation2005). These cultural heritage resources are facing major challenges today because of resource depletion, cultural appropriation (Pham Citation2014; Scafidi Citation2015), and globalization which has reduced the diversity and uniqueness of practices and knowledge. However, the distinctive practices and knowledge of authentic craft production have sparked renewed interest (Castells Citation2004; Kapferer and Bastien Citation2009; Mazzarella et al. Citation2015; Walker Citation2018) and these developments have led the fashion system to rediscover “cultural capital” (Throsby Citation1999) at a time when local communities and their material culture are suffering from impoverishment of meaning and value. Craftsmanship can support the codification of a new cultural language and, at the same time, target consumers who are increasingly attentive to the exclusivity and personalization of particular products (Sennett Citation2008). The interaction of craft and design can generate real value through the transfer of knowledge among stakeholders (EFI Citationn.d.). In this way, a craft-design approach can reconfigure the traditional codes and languages and outline a process of continuous innovation that can be replicated over time and is able to penetrate and compete in globalized markets, thereby valuing cultural diversity as a form of evolved creativity (Vacca Citation2013).

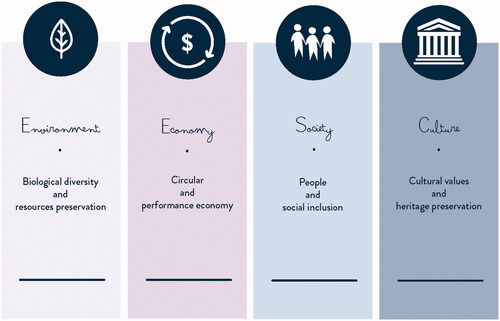

This study explored emerging design scenarios in the field of fashion and craftsmanship. It is oriented toward combining and consolidating the design disciplines with experimentation, innovation, sustainability, and inclusive processes and tools consistent with the four pillars of sustainability (UCLG Citation2010): (1) environment as biological diversity and resource preservation; (2) society as people and social inclusion; (3) culture as cultural values and heritage preservation, and (4) economy as circular and performance-based (). Through a holistic vision of the combined themes of sustainable development (WCED Citation1987) and sustainable fashion (Williams et al. Citation2019), the model attempts to identify strategic assets to deploy in the fashion system to address the challenges of sustainable transformation by enhancing, preserving, and integrating material culture. Accordingly, this study has four objectives. First, we sought to interpret, through the identification of significant and recurring trends, the most developed craft-based strategies in the field of fashion. Second, the work reported here was designed to highlight the dynamics and evolution that the craft and fashion sectors are experiencing currently to promote positive and sustainable changes within the cultural dimension. Finally, we strove to overcome the dynamics of cultural appropriation and misappropriation that have been carried out to the detriment of territories and communities that possess cultural heritage.

Figure 1. The four pillars of sustainability (adapted from UCLG Citation2010).

To design this speculative model, we drew on the results of several of our studies related to the phenomenon of cultural sustainability through traditional craft, with an emphasis on the cultural potential of processes oriented toward the valorization and incorporation of material practices and expertise in fashion (Brown Citation2021; Vacca Citation2013). In the past decade, we have developed personal research paths related to the themes of craftsmanship and cultural sustainability. In this context, we have analyzed skills, practices, methods, processes, materials, tools, relations, communities, and territories. Through these projects, we have come into contact with both micro-scale communities of autonomous and independent artisans and artisanal businesses that are larger and structured and organized more extensively. This study is based upon a global sample of 105 cases of crafting initiatives, each of which we evaluated through preliminary desk research and then developed a map based upon their characteristics. This was followed by a case study that allowed us to study complex phenomena within their contexts (Nixon and Blakley Citation2012). Then, we identified ten case studies and conducted semi-structured interviews with key respondents in each of them to gain deeper insight into their values, processes, approaches, and methodologies. These entities represent excellence in cultural sustainability practices, oriented toward the recovery and enhancement of fashion-design approaches to material culture. We refer to these examples as “culture-intensive artefacts” (Bertola et al. Citation2016). The semi-structured interviews were conducted to enable us to study the techniques, traditions, and customs behind these ancient producers. We identified their connections with the contemporary world, the products they produce, the means through which they communicate and distribute their work, and the nature of their collaborations—whether occasional or continuous—with brands and/or independent designers. Some of the cases were explored through participatory, co-design, and social innovation projects, while others were documented through observation and other modes of investigation. This feature of the project initiated the applied dimension of this research, which allowed us to experiment with models of preservation and the sustainable development of cultural heritage (Bertola, Colombi, and Vacca Citation2014). The expertise that we gained over several years and the sharing of corresponding studies, reflections, and results with us, has provided the data on which our model is based.

We conducted a comparative analysis, examining all of the interview data to identify common themes that came up repeatedly with an inductive approach. Then we clustered the cases to generate themes and to track the directions and behaviors of similar initiatives (Brown Citation2021; Vacca Citation2013). The model was then built with the goal to construct a detailed panorama that relates to contemporary craft dimensions and their implications with respect to fashion design-driven cultural sustainability. We wished to focus on charting trajectories and scenarios for cultural sustainability in fashion through design-led actions, practices, and methodologies that could generate positive transformation that alters the status quo. The research design was qualitative because of its ability to offer an unlimited range of inquiry into the cultural dimensions of the research (Denzin and Lincoln Citation2005). A qualitative approach, while not measurable or quantifiable, is more appropriate to present a broader, more extensive description and allows the researcher to make inductive observations, generate theories, and draw conclusions. However, this approach has three limitations: (1) It is impossible to discuss all of the case studies presented in the article comprehensively; (2) The conclusions cannot be generalized because they are based upon a limited number of observations, and (3) The interpretation of the data is based upon the researchers’ experience and expertise.

Cultural sustainability through craft: an interpretative model

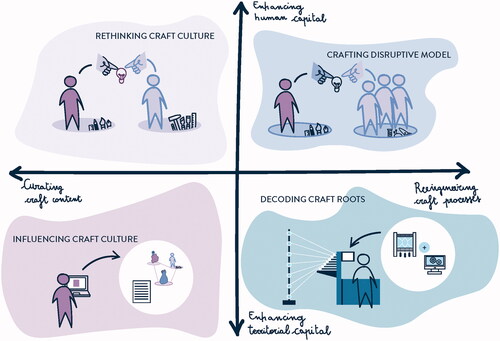

To fulfill the purpose of this study, the model () assesses the different approaches to craft sustainability that emerged from the case studies that we investigated. The two axes of the model are expressed as the polarities identified in the study.

The horizontal axis defines craft-based strategies that consider craft as content. Through design and the creative process, it highlights, on one hand, the distinctive qualities, values, and meanings from a curated, preserved, reactivated, and revalued perspective (curating craft content). On the other hand, craft-based strategies draw attention to the traditional skills, abilities, and technical capabilities that need to be decoded and re-engineered to reactivate and generate new and positive approaches to development (re-engineering craft processes).

The vertical axis identifies the methods and tools used to activate craft-based strategies through the enhancement of cultural heritage. Expressed through the empowerment of the socio-cultural dimension (enhancing human capital), its focus is the improvement of quality of life through community development. The sustainable development of local identity (enhancing territorial capital) to preserve natural resources while producing goods and services with traditional approaches is conducted to support and promote territorial cultural diversity.

By interpreting the polarities of cultural sustainability through craftsmanship, and after positioning the cases investigated in the model, four different scenarios emerged that represent different expressions of living cultural craft and highlight future design opportunities in the fashion field: Rethinking Craft Knowledge, Crafting Disruptive Models, Decoding Craft Roots, and Influencing Craft Culture. Each scenario was traced to identify analogies and similarities in behavior, practices, and methodologies. What emerged within each scenario is a vision of a plurality of meanings and values that each case study incorporates.

Scenario 1: rethinking craft knowledge

This craft-based scenario is oriented toward valorizing and reactivating material culture (curating craft content) through a design-driven approach that enhances artisan communities that hold a specific cultural heritage (enhancing human capital). The craft-design relation is one of continuous exchange and knowledge transfer of techniques and expertise intended to redesign and redefine the expressive codes and processes that combine ancient traditions with symbolic cultural innovation approaches. Artisan communities are not involved merely in production, but are an integral part of the design process, as they provide their skills and creative intelligence in design development. The designer explores generative actions in the design of unique and singular objects (Kopytoff Citation1986; Vacca Citation2013) to preserve the embedded meanings and expressions of heritage that the re-signified artifact expresses.

This scenario is exemplified by designers such as Stella Jean and Swati Kalsi who foster cultural exchange through the integration of artisan communities with the goal to alleviate poverty and contribute to social and creative emancipation through the dignity of work. Although similar, the two designers use two different models of collaboration. Beginning from the paradigms of cultural contamination, creolization and métissage (Glissant Citation1996; Gnisci Citation1998), the Italian/Haitian designer, Stella Jean, created a sustainable development platform called “Laboratorio delle Nazioni (Laboratory of Nations)” that supports her work with artisan communities. The designer’s international cooperation projects stem from her desire to study traditional textile processes and techniques which, hybridized with a design vision, become esthetic overlaps of great fascination within her collections. Each collaboration is a form of cultural exchange and “permissive appropriation” (Scafidi Citation2015) that results in positive interactions with artisan communities. In this scenario, the artisans’ work is not only recognized, communicated, and valued, but also emancipated through the development of a sustainable business model that empowers communities through the dignity of work.

Alternatively, the Indian designer, Swati Kalsi, is a spokesperson for a specific cultural heritage within India (Brown Citation2021). She works in a highly collaborative process to explore the technique and tradition of Sujani that pushes the boundaries and elicits the artist and creator within the women artisans which results in the repositioning of tradition. Kalsi’s collections are distinguished by the intersection of design, craftsmanship, and art. They consist of unique garments embellished elaborately with Sujani embroidery from the Bihar region. The designs are produced entirely outside of the seasonal fashion calendar and honor instead the time, skill, and labor required to achieve their intensive craftsmanship. The designer’s contribution is to conceive through ongoing dialogue and shared vision timeless garments that preserve, sustain, and tell the stories of women artisans, because, as Harrison (Citation1978, 1) argued, “Making items is part of a constructive cultural activity and is a part of the fabric of society.”

Scenario 2: crafting disruptive models

The second scenario proposes the reactivation of techniques and processes related to crafts (re-engineering craft processes) that embody capacity-building actions as the determinants of improved standards of living (enhancing human capital). Local production based upon traditional techniques becomes the vector with which to recontextualize, revalue, and revitalize material culture through participatory and co-designed innovative processes. Investment in human capital promotes new processes of value generation that result in products, as well as disruptive business models oriented toward the reconstruction of local communities as the means to promote cultural sustainability and ethics.

This scenario presents a plurality of actions that can be grouped into two main approaches. The first requires the commitment to work with disadvantaged social communities (Krippendorff Citation2006) with the intended outcome of social redemption. The second promotes the enhancement of a specific community’s cultural capital by rediscovering and redesigning distinctive craft practices to create new cultural and production models (Vacca Citation2013).

The first approach includes the social innovation projects that fashion companies and independent designers have promoted to emancipate specific communities. It targets fragile communities, not holders of a predefined cultural heritage such as prisoners, migrants, and the unemployed. The investment in cultural capital is expressed through the involvement of master craftspeople of distinctive techniques and processes rooted in territory. Programs are focused on the development of training that supports social development and positive growth to achieve better standards of living and opportunities for self-affirmation through dignified work. Examples of the cultural capital investment are expressed in such projects as “Made in Prison” by Carmina Campus, Tod’s collaboration with a recovery community for drug addicts in San Patrignano, Italy, and the ethical Italian fashion brand, Progetto Quid.

This second approach is characterized by the development of innovative and disruptive business models that invest in cultural heritage and knowledge to ensure the historical continuity of codes and meanings. Donna Karan’s Urban Zen Foundation exemplifies this scenario and represents a philosophical paradigm rooted in the preservation of culture and support of health and education. As an approach, its goal is to uphold community and to maintain identity and diversity through projects that preserve cultural and spiritual values, as well as facilitate the development of artisanal entrepreneurship through an educational commitment to the next generation. As a disruptive model based upon craft it is inspired by the theories of Amartya Sen (Citation2000), who advocates for social welfare based upon human rights, and the concept that people should reach their potential in doing and being, thereby becoming capable in the sense of learning and knowing the way to do things.

Scenario 3: decoding craft roots

The third scenario focuses on craft-based actions intended to decode manufacturing processes (re-engineering craft processes) to foster a local, territorial dimension (enhancing territorial capital). This concept of craftsmanship represents a departure from a simple definition of “handmade” with its emphasis on a master craftsperson’s manual skills (Adamson Citation2007). While it does embrace the broader meaning of craft knowledge and expertise as an expression of a specific territory, it is in constant evolution because of the embedded nature of the material culture (Sennett Citation2008; Vacca Citation2013). Therefore, this approach focuses on the recovery of production processes that have been forgotten in part or have become outdated because of obsolete technologies in which there is little interest or generational knowledge transfer. There are no predefined hierarchies of value between craftsmanship, industry, and technology, which thereby gives form to an advanced concept of authenticity. Enzo Mari (Citation2011, 67–68) explained this idea eloquently: “When you make a serial product…the heart, the cleverness of the factory is located in the department of prototypes, where the work of everyone, from the top designer to the last technician, is still artisanal, regardless of whether it is processed with the help of a computer or a pencil.”

The recognition of the cultural potential of manufacturing heritage and the construction of territorially specific models for the preservation of practices and methodologies form the basis of the philosophy of Bonotto’s “Fabbrica Lenta (Slow Factory).” Based in Molvena, Italy, Bonotto offers products rooted in the heritage of craftsmanship, combined with research, creativity, and innovation, and in opposition to the industrial standardization of production. The company has recovered proto-industrial machinery and technologies to develop highly limited and experimental production. The research process that Bonotto uses is focused on the overlap between design thinking and design methods. Fabbrica Lenta’s products are made through a hybrid process that combines the slowness and knowledge of craftsmanship produced on old looms with the speed of technological processes that give new meaning and importance to new products.

An interesting characteristic of this scenario is exemplified by many emerging startups that recognize the strong potential of cultural heritage expressed through manufacturing, skills, and expertise. Brands such as Wrad, Rifò, and Wuuls have developed their own identity precisely through re-engineering and regenerating manufacturing processes and techniques. They recontextualize methods and practices and thereby realign the value system to which they belong. The brands apply unconventional technologies and cutting-edge processes to traditional handicraft culture to envision contemporary archetypes with a renewed local authenticity. Thus, the application of advanced design practices oriented to identify future perspectives through the creation of innovative products and processes (Celi Citation2015) helps visualize future scenarios for artisans without the loss of the legacy, local identity, or artisanal expertise. Moreover, decoding the pairing of technology and craftsmanship amplifies the application and encourages positive social and cultural change.

Scenario 4: influencing craft culture

The fourth and final scenario is contextualized in valorization of the territorial capital of a specific socio-cultural and productive system (enhancing territorial capital) through a design methodology that is editorial and curatorial in nature (curating craft content). The main objective of this scenario is to valorize the traditional archetypes of the most important handicrafts and transport them uncontaminated into the contemporary world. Abandoning the patina of time typical of ancient workmanship, it offers visibility and transparency in its stead as a new expression of respect. As a curatorial approach, it favors a dialogue and exchange between producer and consumer in the creation of cultural content. It fosters the ability to interact and experiment with personalized ways of using and means of understanding heritage. Design serves as the activator of socio-cultural networks between small, historically significant artisanal realities and the broader context. It is not bound by territory or local boundaries in an effort to access a wider market. It exploits the integration and hybridization of media, both with respect to diffusion through new media’s social platforms and through increased interaction with fashion’s meanings, techniques, processes, and culture with the user’s involvement and transmedia narratives as a way to reach the diverse fashion community. In this context, the production dimension is shown, told, and presented through storytelling that enhances technique as well as tangible memories, and the objects that represent the places and experiences behind them.

This scenario aspires to raise the visibility of local culture through awareness of the specificities preserved within that constitute heritage’s capability to bring economic development to local communities. Territorial storytelling serves as a route to “cultural appreciation” (Scafidi Citation2015) addressed to an increasingly attentive and aware public. It is a way to support a territory’s material culture by telling the stories of the craft. Further, it is a means of breaking established patterns related to territory through a complex narrative system that defines the limitations between plagiarism and inspiration, homage and appreciation, and includes the implicit denunciation of appropriation. The ability to tell stories effectively can give sense and meaning to lives and experiences. As Benjamin (Citation1968) argues, storytelling is therefore not only a way to see more deeply, but also an action of ethics and responsibility because of its ability to preserve and transfer knowledge, experiences, and traditions in a recognizable way.

Best practices in this field are represented by Bihor Couture which is transforming the way that “shared dialogic heritage” (Härkönen, Huhmarniemi, and Jokela Citation2018) is transferred radically through the creation of a physical as well as virtual space to showcase the various facets that local culture has to offer. Through provocation and cultural promotion, they offer an intelligent campaign born from collaboration between the magazine Beau Monde and the community of Bihor in Romania. After deciding not to suffer French Maison Dior’s misappropriation of their heritage for their pre-fall 2017 couture collection passively, they instead claimed proudly the ownership of the traditional embroideries handed down through generations that Dior copied. The denunciation project highlighted creatively the act of cultural misappropriation that characterizes increasingly the fashion industry’s ongoing failure to recognize the original holders of knowledge who are left all too often unprotected from the inappropriate and disparaging use of their cultural heritage (Boța-Moisin Citation2017). Bihor Couture was conceived as a website dedicated to the typical creations of the region. Through video interviews with local artisans, they describe the distinctive techniques that represent the region’s culture and customs and offer their traditional products for distribution through an e-commerce site that benefits the Bihor community. This offers an example of cutting-edge cultural experimentation in an era in which cultural appropriation is commonplace. Through the power of evocative storytelling, Bihor Couture seeks to restore authenticity to the territory in the form of cultural values and meanings linked to ideas, people, and place.

Conclusion

From this proposition, craftsmanship emerges as an “open knowledge system” (Sennett Citation2008) that by its nature evolves over time. Through continuous transformation, it becomes the core of community identity (Adamson Citation2007) and a differentiating factor in material culture (Miller Citation1987) through the deep connections that craftsmanship has with culture, memory, and tradition. Therefore, discussion about cultural sustainability as craft knowledge with deep historical roots entails approaching the issue of sustainable development by strengthening cultural identity (Friedman Citation1994; Matahaere-Atariki Citation2017) and revitalizing local cultural heritage through continuous investment in territory-specific human and cultural capital (Auclair and Fairclough Citation2015). This proposition highlights an increasing need for the legal protection of material culture supported by systemic change in the way fashion is taught in academia to eliminate the practice of cultural appropriation in design development. Although some universities have embarked on decolonization of the curriculum (The Fashion and Race Database Citation2017; FashionSEEDS Citation2019), many institutions continue to train designers as autocratic decision makers in product development regardless of context, leading to the belief that it is appropriate in all settings (Johnson Citation2018, 190).

The interpretative model proposed highlights the different opportunities for design to assume the role of promoter of continuously innovative processes that favor traditional activities and crafts without distorting the meanings or impoverishing the identity of the culture they represent. Exchanging practices and sharing methodologies between design and craft are the tools with which to bring different communities closer to the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), provided by the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (UN Citation2015). Archetypal productions that embody the customs, relations, knowledge, and techniques handed down from generation to generation in a localized context (Friedman Citation1994) are regenerated through a range of design-led processes of translation and exchange. Experimentation with increasingly innovative visions, approaches, and methods supports the consolidation and linkage of culture and territory. The relentless advancement of technological and digital resources, which are increasingly accessible, has led craftspeople to question how to integrate new and advanced processes without losing uniqueness and heritage. At the same time, this paradigm shift does not imply the passive adoption of specific technologies, but instead a path of re-engineering, exchanging, and sharing visions, practices, knowledge, meanings, and values through the process of similarity and contrast, of preservation and innovation, of typicality and novelty (Vacca Citation2013).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Adamson, G. 2007. Thinking Through Craft. London: V&A Publications.

- Alliance for Artisan Enterprise. 2016. 2016 Impact Report. Washington, DC: Aspen Institute. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/52669d1fe4b05199f0587707/t/584aec10440243bff33a0ab0/1481305126023/2016±AAE±Impact±Report_FINAL.pdf

- Anderson, J. 2010. Indigenous/Traditional Knowledge & Intellectual Property. Durham, NC: Center for the Study of the Public Domain, Duke University School of Law. https://web.law.duke.edu/cspd/pdf/ip_indigenous-traditionalknowledge.pdf

- Auclair, E., and G. Fairclough. 2015. “Living Between Past and Future: An Introduction to Heritage and Cultural Sustainability.” In Theory and Practice in Heritage and Sustainability. Between Past and Future, edited by E. Auclair and G. Fairclough, 1–22. London: Routledge.

- Axelsson, R., P. Angelstam, and E. Degerman. 2013. “Social and Cultural Sustainability: Criteria, Indicators, Verifier Variables for Measurement and Maps for Visualization to Support Planning.” Ambio 42 (2): 215–228. doi:10.1007/s13280-012-0376-0.

- Benjamin, W. 1968. “The Storyteller: Reflections on the Works of Nikolai Leskov.” In Illuminations, edited by W. Benjamin, H. Arendt, and H. Zohn, 83–109. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

- Bertola, P., C. Colombi, and F. Vacca. 2014. “Design Re.Lab: How Fashion Design Can Stimulate Social Innovation and New Sustainable Design.” The International Journal of Design in Society 7 (4): 47–61. doi:10.18848/2325-1328/CGP/v07i04/38548.

- Bertola, P., F. Vacca, C. Colombi, V. Iannilli, and M. Augello. 2016. “The Cultural Dimension of Design Driven Innovation. A Perspective from the Fashion Industry.” The Design Journal 19 (2): 237–237. doi:10.1080/14606925.2016.1129174.

- Bihor Couture. 2018. “Bihor Couture: The Story.” Video. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Q-i7-ZC-0Hs

- Black, K. 2016. “Working with Artisans Requires a New Model.” HuffPost, September 15. https://www.huffpost.com/entry/working-with-artisans-requires-a-new-business-model_b_57dae91ae4b053b1ccf29571

- Boța-Moisin, M. 2017. “Cultural Fashion: Transform the Fashion Industry from Villain to Hero.” Video. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=twHCsVPupXo

- Brown, S. 2021. “An Evaluation of the Types and Levels of Interventions Used to Sustain Global Artisanship in the Fashion Sector.” PhD dissertation, Manchester Metropolitan University. https://e-space.mmu.ac.uk/628738.

- Castells, M. 2004. Il potere delle identità (The Power of Identities). Milan: Edizioni UBE

- Celi, M. 2015. Advanced Design Cultures: Long-Term Perspective and Continuous Innovation. Cham: Springer.

- Denzin, N., and Y. Lincoln. 2005. The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Ethical Fashion Initative (EFI). n.d. ITC Ethical Fashion Initiative. Geneva: EFI. https://ethicalfashioninitiative.org/about

- Faro Convention 2005. Council of Europe: Convention on the Value of Cultural Heritage for Society. Strasbourg: Council of Europe. https://www.coe.int/en/web/culture-and-heritage/faro-convention.

- FashionSEEDS 2019. Fashion Societal, Economic and Environmental Design-Led Sustainability. London: London College of Fashion. https://www.fashionseeds.org.

- Friedman, J. 1994. Cultural Identity and Global Process. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Friedman, V. 2019. “Homage or Theft? Carolina Herrera Called Out by Mexican Minister.” The New York Times, June 13. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/06/13/fashion/carolina-herrera-mexico-appropriation.html

- Fry, T. 2009. Design Futuring: Sustainability, Ethics and New Practice. Oxford: Berg Publishing.

- Glissant, E. 1996. Introduction à une poétique du divers (Introduction to a Poetics of Diversity). Paris: Gallimard.

- Gnisci, A. 1998. Creoli, meticci, migranti, clandestini e ribelli (Creoles, Mestizos, Migrants, Illegal Immigrants and Rebels). Rome: Meltemi.

- Härkönen, E., M. Huhmarniemi, and T. Jokela. 2018. “Crafting Sustainability: Handcraft in Contemporary Art and Cultural Sustainability in the Finnish Lapland.” Sustainability 10 (6): 1907. doi:10.3390/su10061907.

- Harrison, A. 1978. Making and Thinking: A Study of Intelligent Activities. Hassocks: Harvester Press.

- Hope, K. 2015. “The Artisans in Danger of Disappearing.” BBC News, March 11. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-31791937

- Johnson, P. 2018. “New Caribbean Design.” In Design Roots Culturally Significant Designs, Products, and Practices, edited by S. Walker, M. Evans, T. Cassidy, J. Jung, and A. Twigger Holroyd, 190–197. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Kangas, A., D. Nancy, and C. De Beukelaer. 2017. “Introduction: Cultural Policies for Sustainable Development.” International Journal of Cultural Policy 23 (2): 129–132. doi:10.1080/10286632.2017.1280790.

- Kapferer, J., and V. Bastien. 2009. “The Specificity of Luxury Management: Turning Marketing Upside Down.” Journal of Brand Management 16 (5–6): 311–322. doi:10.1057/bm.2008.51.

- Keiner, M. 2005a. “History, Definition(s) and Models of ‘Sustainable Development.’” ETH Zurich. https://www.research-collection.ethz.ch/bitstream/handle/20.500.11850/53025/eth-27943-01.pdf.

- Keiner, M. 2005b. “Re-emphasizing Sustainable Development: The Concept of ‘Evolutionability.’” Environment, Development and Sustainability 6 (4): 379–392. doi:10.1007/s10668-005-5737-4.

- Kerry, J. 2015. “Celebrating the Power of Artisan Enterprise to Change the World.” Aspen Institute, September 15. http://aspen.us/journal/editions/septemberoctober-2015/celebrating-power-artisan-enterprise-change-world

- Kopytoff, I. 1986. “The Cultural Biography of Things: Commoditization as Process.” In The Social Life of Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspective, edited by A. Appadurai, 64–94. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Krippendorff, K. 2006. The Semantic Turn: A New Foundation for Design. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.

- Larson, N. 2015. “Inspiration or Plagiarism? Mexicans Seek Reparations for French Designer’s Look-alike Blouse.” The Guardian, June 17. https://www.theguardian.com/global-development-professionals-network/2015/jun/17/mexican-mixe-blouse-isabel-marant

- LVMH. n.d. “LVMH Metiers d’Art.” https://www.lvmh.com/group/lvmh-commitments/transmission-savoir-faire/lvmh-metiers-darts-initiative-lvmh/

- Mari, E. 2011. 25 modi per piantare un chiodo (25 Ways to Drive a Nail). Milan: Mondadori.

- Matahaere-Atariki, D. 2017. “Cultural Revitalisation and the Making of Identity within Aotearoa New Zealand.” Te Puni Kōkiri. https://www.tpk.govt.nz/en/a-matou-mohiotanga/culture/cultural-revitalisation-and-the-making-of-identity

- Mazzarella, F., C. Escobar-Tello, and V. Mitchel. 2015. “Service Ecosystem: Empowering Textile Artisans’ Communities Towards a Sustainable Future.” UAL Research Online. https://ualresearchonline.arts.ac.uk/id/eprint/15281/1/437-912-1-PB.pdf

- Miller, D. 1987. Material Culture and Mass Consumption. Oxford: Basil Backwell.

- Murphy, E. 2018. “Designing Authentic Brands.” In Design Roots Culturally Significant Designs, Products, and Practices, edited by S. Walker, M. Evans, T. Cassidy, A. Twigger Holroyd, and J. Jung, 331–339. London: Bloomsbury.

- Nixon, N., and J. Blakley. 2012. “Fashion Thinking: Towards an Actionable Methodology.” Fashion Practice: The Journal of Design, Creative Process and the Fashion Industry 4 (2): 153–175. doi:10.2752/175693812X13403765252262.

- Oppenheimer, T. 2019. “The Future is Handmade.” The Craftsmanship Quarterly, Winter. https://craftsmanship.net/the-future-is-handmade

- Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). 2020. Culture Shock: COVID-19 and the Cultural and Creative Sectors. Paris: OECD. https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/culture-shock-covid-19-and-the-cultural-and-creative-sectors-08da9e0e.

- Pham, M. 2014. “Why We Should Stop Talking About Cultural Appropriation”. The Atlantic, May. https://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2014/05/cultural-appropriation-in-fashion-stop-talking-about-it/370826

- Quartz. 2015. “Here’s What It Looks Like When Cultural Appropriation is Done Right.” Video. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cEz8-oywKUk

- Rullani, E. 2004. Economia della conoscenza: Creatività e valore nel capitalismo delle reti (Economy of Knowledge: Creativity and Value in Network Capitalism). Rome: Carocci.

- Scafidi, S. 2015. Who Owns Culture? Appropriation and Authenticity in American Law. New Brunswick NJ: Rutgers University Press.

- Sen, A. 2000. Development as Freedom. New York: Anchor Books.

- Sennett, R. 2008. L’uomo artigiano (The Craftsman). Milan: Feltrinelli

- The Fashion and Race Database. 2017. The Fashion and Race Database. https://fashionandrace.org.

- Throsby, D. 1999. “Cultural Capital.” Journal of Cultural Economics 23 (1–2): 3–12. doi:10.1023/A:1007543313370.

- United Cities and Local Governments (UCLG). 2010. Culture: The Fourth Pillar of Sustainability. Barcelona: UCLG. http://www.agenda21culture.net/documents/culture-the-fourth-pillar-of-sustainability

- United Nations Economics, Scientific, and Cultual Organization (UNESCO) 2001. Universal Declaration on Cultural Diversity. Paris: UNESCO. http://www.unesco.org/new/fileadmin/MULTIMEDIA/HQ/CLT/pdf/5_Cultural_Diversity_EN.pdf.

- United Nations Economics, Scientific, and Cultual Organization (UNESCO) 2015. UN System Task Team on the Post-2015 UN Development Agenda: Cutlure: A Driver and Enabler of Sustainable Development. Paris: UNESCO. https://www.un.org/millenniumgoals/pdf/Think%20Pieces/2_culture.pdf.

- United Nations Economics, Scientific, and Cultual Organization (UNESCO) 2018. Dive into Intangible Cultural Heritage. Paris: UNESCO. https://ich.unesco.org/en/dive&display=biome.

- United Nations 2015. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. New York: United Nations. https://sdgs.un.org/publications/transforming-our-world-2030-agenda-sustainable-development-17981

- Vacca, F. 2013. Design sul filo della tradizione (Design on the Thread of Tradition). Bolognia: Pitagora.

- Vézina, B. 2019. “Curbing Cultural Appropriation in the Fashion Industry.” Presentation at the ABC Copyright Conference, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, Canada, May 31. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/0725/4965e32967001380b9933fafab2a19f722e0.pdf

- Walker, S. 2018. “Culturally Significant Artifacts and Their Relationship to Tradition and Sustainability.” In Design Roots: Culturally Significant Designs, Products, and Practices, edited by S. Walker, M. Evans, T. Cassidy, A. Twigger Holroyd, and J. Jung, 39–50. London: Bloomsbury.

- Williams, D., N. Stevenson, J. Crew, N. Bonnelame, F. Vacca, C. Colombi, E. D’Itria, et al. 2019. Education and Research: Benchmarking Report. London: FashionSEEDS. https://www.artun.ee/app/uploads/2020/02/IO1_BENCHMARKING-REPORT_-Fashion-SEEDS.pdf.

- World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED) 1987. Our Common Future. Oxford: Oxford University Press.