Abstract

Low-tech approaches have come to the fore in the last few years, mainly in opposition to the techno-optimistic model proposed to solve current and future environmental crises. However, low-tech thinking is multifaceted, making the concept potentially rich but also vague. This article develops a seven-principle framework to categorize low-tech concepts based on an abductive approach which included a literature review and interviews with low-tech actors. Principle occurrence was assessed among the authors and interviewees. The results demonstrate that the low-tech movement entails more than a shift to robust and less-consumptive technical artifacts. While resource efficiency and material reuse are important traits of low-tech approaches, technical appropriation is the most frequently cited key principle in the literature and by the actors. This delineation into several principles can help to differentiate low-tech from other sustainability concepts related to resource conservation such as frugal innovations and circular economy. We aim in this article to open a discussion about the ways low-tech proponents are seeking to introduce transformative development pathways to sustainability.

Introduction

Societies are facing a major ecological crisis that risks altering their functioning in a lasting and irreversible way (Rockström et al. Citation2009; Steffen et al. Citation2015). At the same time, recent discussions on the emergence of alternative development pathways such as circular economy and degrowth have noted the key role of technology in addressing the sustainability challenge (Bauwens, Hekkert, and Kirchherr Citation2020; Calisto Friant, Vermeulen, and Salomone Citation2020; Kerschner et al. Citation2018). These authors have highlighted the debate between enthusiasm and skepticism toward technology in its ability to mitigate environmental problems. For instance, Kerschner et al. (Citation2018) emphasizes that the mainstream sustainability discourse is currently focused on a techno-optimistic model which suggests that the marketing of new green tools alone can overcome the ecological obstacles that contemporary societies face. In the context of circular economy, this analysis was also endorsed by Calisto Friant, Vermeulen, and Salomone (Citation2020) who categorize the circularity discourses made by the government and corporate sectors and show that 84% of the examples that they analyzed could be labeled as “technocentric.”

In response to this vision, a low-technology (low-tech) narrative has emerged and generated interest in the literature in recent years (Alexander and Yacoumis Citation2018; Bauwens, Hekkert, and Kirchherr Citation2020). However, definitions of “low-tech” are diverse, if not ambiguous. For example, to many techno-optimists, low-tech is similar to no-tech, which can partially be compared to the Amish style of living (Kerschner and Ehlers Citation2016). In the innovation literature, low-tech solutions “can typically be fabricated with a minimum of capital investment and are characterized by the low knowledge transfer costs incurred to understand them” (Bauwens, Hekkert, and Kirchherr Citation2020). From an engineering perspective, Alexander and Yacoumis (Citation2018) consider low-tech a technology that “does not require electricity or fossil fuels to operate.” However, the same authors also define low-tech as consisting of “behavior changes” and argue for “low-tech living” (i.e., not relying on complex technological solutions to live), thus adding a sociotechnical dimension to the concept.

In the past decade in France, this sociotechnical dimension has been explored under the influence of several actors who have helped to diffuse different perspectives on low-tech. For example, author and engineer Philippe Bihouix (Citation2014) linked global resource depletion to the use of advanced technology. He described how a constrained and finite natural environment redefines the use of technology which should be limited to covering what societies consider essential needs. Low-tech solutions are therefore not only low-energy technical objects but also a design approach not centered on technology. Another actor, the Low-Tech Lab, highlights and promotes the technical accessibility of low-tech. The association fosters a community of independent users able to repair and reuse various technical objects (Low-Tech Lab Citation2022). Under this leadership, low-tech has become a research agenda in numerous disciplines including design studies, history, urban planning, and engineering, each with its own focus on what low-tech might entail (Abrassart, Jarrige, and Bourg Citation2020; Carrey and Lachaize Citation2020; Florentin and Ruggeri Citation2019; Grimaud, Philippe, and Vidal Citation2017; Roussilhe Citation2020). A common thread, however, is reference to the seminal work of Ivan Illich (Citation1973) on convivial tools, suggesting the potentially large scope of low-tech research and connecting this work to longstanding interest in alternative technology for sustainability.

These examples highlight the multifaceted nature of the low-tech concept in France and elsewhere as well as its potential to address some of the criticism frequently made with respect to techno-optimistic interventions (Kerschner et al. Citation2018). However, the concept relies on scattered perspectives and motivations ranging from the resource conservation of Bihouix (Citation2014) to the commentary of Alexander and Yacoumis (Citation2018) and social accessibility outlined by the Low-Tech Lab. The absence of a clear and definitive framework puts the concept at risk of being amalgamated within the logic—most notably of green growth—that it seeks to oppose. The concept of low-tech would thus benefit from being clarified to identify its specificity and potential contribution to systemic societal transformation.

The work presented in this article aims to gather the perspectives found in the low-tech literature and practice to define a general framework that delineates the scope of its expected outcomes in response to environmental, social, and political issues introduced by the use of advanced technology. Specifically, we aim to explain the underlying key principles of low-tech approaches to better assess the notions driving low-tech projects and discourses. The decomposition into distinct but interconnected principles helps to account for the multifaceted nature of low-tech approaches, avoiding the pitfalls of formulating a fixed definition and addressing a current gap in the literature. We also strive to make more definitive links with other sustainability efforts and to identify the contribution of low-tech in this field. This work is the result of a collaborative research project conducted between 2020 and 2021 that gathered academics from three French universities and two industrial partners.Footnote1

The article is structured as follows. The next section describes the abductive approach based on a literature review and semi-structured interviews with relevant actors that we developed to identify seven low-tech principles. We then explain the key principles based on the different actor perspectives. Finally, we describe our eventual framework and clarify the links between low-tech and several prominent sustainability concepts.

Materials and methods

The objective of this study was to develop a framework to explain the origins and motivations of the low-tech movement as expressed today in Western countries, particularly France. We adopt the view that these approaches can be described by a set of key principles. A key principle is defined here as a response to a problem caused by the use of technology in contemporary society. The objective of the key principles is to formulate a framework that specifies the issues that low-tech interventions intend to address.

The key principles may be interconnected—that is, one key principle may be difficult to consider without another—but they are each a distinct response to one or more problems. In comparison to Bihouix’s principles, for example, they represent the lowest common denominators of the issues addressed by the low-tech community, shared by different authors and actors. Each key principle taken separately is not a low-tech characteristic but rather may be shared by other scientific currents seeking to improve system sustainability. It can also constitute a one-dimensional low-tech vision expressed by an author or actor, depending on his or her discipline, the problem addressed, and his or her background. In addition, taken together, the key principles delineate the origins and motivations of low-tech approaches.

We categorized the low-tech concepts into a set of key principles using an abductive approach (Dubois and Gadde Citation2002). The abductive approach is a qualitative research method that aims to explain an observed phenomenon through an iterative process of (1) searching for possible explanations (based on scientific theory) and (2) evaluating the plausibility of these explanations through a confrontation with experience and the field. It is thus opposed to purely deductive (based on theory) or purely inductive approaches (based on experience) since it involves moving between the two approaches to expand the understanding of both theory and empirical phenomena (Dubois and Gadde Citation2002).

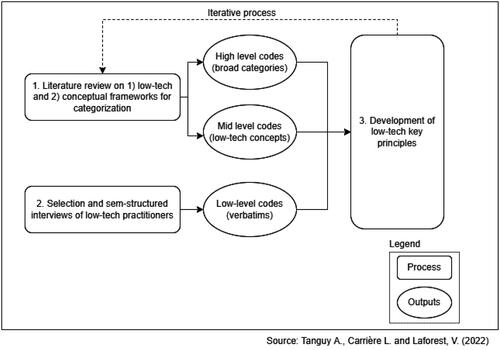

To better comprehend and deploy this concept, we analyzed the grey and scientific literature pertaining to actors’ discourses on the general subject. The results of these investigations led to identification of the key low-tech principles. shows the three-step sequence that we followed. Each step is described in further detail in the next subsection.

Literature review

We used the keywords “low-tech” and “low-technology” and their French equivalent (basses technologies) in the Scopus, Web of Science, and Cairn databases (the last being a French database for the humanities and social sciences) to identify articles published between September 2020 and December 2021. Using only “low-tech” as a search criterion was a conscious choice and was deemed necessary to limit as much as possible the bias introduced by literature close to the low-tech movement but whose links with it are not clearly identified and characterized (e.g., frugal innovations, convivial technologies) (Radjou and Prabhu Citation2015; Vetter Citation2018). This selection also excludes from the analysis works that predate the 2000s, such as the work of Ivan Illich cited in the introduction and whose ideas continue to percolate in the low-tech literature and, as a result, in the key principles, but which are not stamped as “low-tech.”

The initial search resulted in more than 550 papers, conference proceedings, and book chapters. The selected documents were in both English and French. We applied several selection criteria. The first was to exclude the research that did not address low-tech as a potential pathway to sustainability with respect to a field or a case study. For example, we excluded works if they referred to low-tech as an industrial sector such as the textile, paper, and cardboard industries. Also set aside were experiments carried out in microbiology or the educational sciences that were unrelated to sustainability. This criterion excluded the vast majority of the initial sample, resulting in a subset of 23 papers.

We then considered contributions further if they directly addressed a low-tech definition or explained low-tech characteristics with respect to a field or a case study. That is, if the article mentioned low-tech in the introduction only and then developed another topic (e.g., degrowth), it was excluded. This step resulted in eight retained papers.

Finally, we added the relevant grey literature via a snowball-sampling approach, discussions with specialists in the field, and checking citations in the sampled studies. In the end, 13 papers, essays, and reports constituted the overall sample.

The corpus that we obtained is quite heterogeneous, reflecting the multi-disciplinarity of the work carried out by the low-tech research community. Although the selected works are difficult to categorize, provides the main information about their objectives and scientific disciplines.

Table 1. Selected low-tech literature.

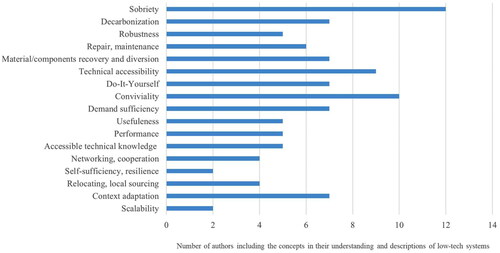

This literature led to a list of concepts associated with low-tech and contributed to development of the key principles. All of these ideas are listed in the appendix () along with the number of references that mentioned them. The criteria for selection were twofold: they had to introduce a new perspective to the concept and at least two sources had to refer to them in their definition of low-tech.

Finally, we looked for conceptual frameworks in the literature that could be used to categorize concepts into key principles. Indeed, abductive research does not seek to create new rubrics but rather to adapt existing ones and to specify them for the object of study (Dubois and Gadde Citation2002). The sustainability literature provides a number of conceptual frameworks, generally used to construct archetypes that reflect the processes underlying the emergence of sustainable approaches (Bocken et al. Citation2014; de Jong et al. Citation2015; Holden, Li, and Molina Citation2015). For example, Bocken et al. (Citation2014) developed archetypes of sustainable business models based on the nature of the change: technical (e.g., maximizing material and energy efficiency), social (e.g., encouraging sobriety), or organizational (e.g., allowing changes of scale). The advantage of this categorization method is that it is likely to parallel changes related to the techniques with social and organizational changes that are present in the low-tech literature (changes in the relationship between people and techniques). Ultimately, the higher-level classification (technical, social, and organizational) was used to guide the construction of the key principles for low-tech approaches.

Semi-structured interviews

In a second phase, we conducted 19 semi-structured interviews with actors working in the low-tech field in France. These interviews were conducted in French and then translated into English. The respondents represented organizational structures selected based on an Internet search using a search engine with the keyword “low-tech,” via dedicated websites—such as the Low-Tech Lab site, the LowTRE Forum, and the wikipage Les Communs—or directly via the project collaborators’ network. We prioritized the interviewees by those who put forward the term low-tech (in the organization’s name, on the website, or via an interview) and/or who used a majority of the mid-level concepts identified in the literature.

We divided the organizations into six categories according to their role in the low-tech sphere. This categorization made it possible, on one hand, to show the diversity of the actions carried out and, on the other hand, to present the key principles per actor category, which can reveal different low-tech visions. These categories and their sample shares are presented in .

Table 2. Respondents by category and organization.

Of the 19 respondents, 14 of them have at least two functions (e.g., designer and educator), but only their main functions are indicated in the table. The educators’ category is the most represented, likely because it is currently one of the only viable business models for low-tech actors. As one organization representative explained, “If we try to sell what we make in a low-tech way, the cost of labor compared to the cost…of the manufactured products is so expensive that we cannot make a living out of it.” Facilitators are also numerous in the sample, as this is historically a foundational function for low-tech activity in France, whose main representative is the Low-Tech Lab. The underrepresentation of designers and makers/fixers is, by contrast, a methodological bias of this study, as analysis of their practices is the subject of a work conducted by other members of the project team. Accordingly, we have not integrated these perspectives into this article to a significant degree. This omission could have consequences for the representation of key principles related to the repair and do-it-yourself movements that are essential to the work of makers and fixers (Hector and Botero Citation2022; Lepawsky Citation2020). Additional information about the interviewees’ activity profiles and examples of the low-tech objects that they use or develop are provided in the appendix ( and ).

Finally, the objective of the interviews was to collect from low-tech actors their perceptions and definitions of what a low-tech approach can be. To this end, we built an interview grid (). It addressed questions pertaining to the general understanding of the term low-tech and its stakes, the existing concepts that would fit/not fit into the actors’ definitions of low-tech, low-tech implementation examples and difficulties, and the motivations and values underlying the related actions. We designed this interview grid to ask open-ended questions without reference to the concepts seen in the literature so as not to influence the resultant answers. The term “principle” was not mentioned either, at the risk of referring to Bihouix’s (Citation2014) seven principles.

Key-principle development

This section describes the process of key-principle development from the low-tech concepts identified in the literature and the statements obtained during the interviews. The method that we used to elicit important themes from the literature and practice was based on Bocken et al. (Citation2014) who has developed archetypal sustainable business models and Holden, Li, and Molina (Citation2015) who formulated archetypal sustainable neighborhoods. These authors used both theoretical and open-coding. Theoretical coding includes the higher-level literature categorizations (e.g., technical, social, and organizational change) and the mid-level codes derived from the literature. Open-coding is a specific low-tech characteristic given by an organization and designates the low-level codes. The low-level codes from the practice were systematically compared to the higher-level codes from the literature to check for similarities and differences. An example of this process is given in the appendix (see and ).

The mid-level codes were then grouped to form key principles. A key principle is self-explanatory, self-sufficient, and not redundant with other key principles. During the analysis, if a new principle appeared to refer to an existing principle, it was either broken down so that each part was integrated with other principles or selected as a new key principle (Luederitz, Lang, and Von Wehrden Citation2013). As a part of this process, members of the project team conducted joint discussions to understand the reasoning behind these categorizations. We obtained the ultimate list of key principles when we reached a final agreement and saturation. shows an example of a final output of this exercise for social change.

Table 3. Coding exercise for the key principle back to basics.

Results

We present our results in two parts. The first part presents the key principles that emerged from the analysis of the low-tech literature and practice. They constitute the basis with which both researchers and practitioners generally agree. The second part presents a quantitative analysis of the key principles that allows us to distinguish the various degrees to which they are integrated into the definitions.

Qualitative analysis of low-tech key principles

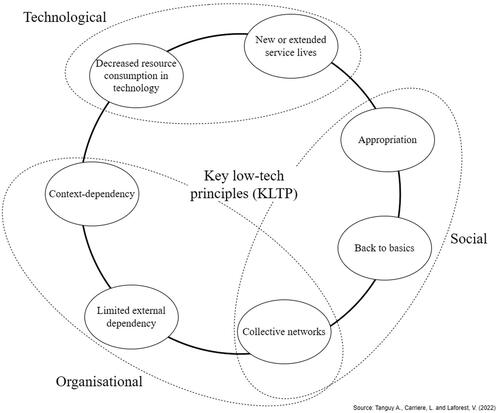

This section describes the key low-tech principles (KLTP) systems extracted from the literature and the semi-structured interviews. They are not individually specific to low-tech approaches, but they represent the conceptual space within which low-tech systems are bound. As presented in , we extracted seven KLTPs and gathered them into three high-level codes.

The following sections explain each principle in detail.

KLTP 1: decreased resource consumption in technology (especially nonrenewable resources)

The concept of decreased resource consumption is ubiquitous in the low-tech literature and the among actors. Abrassart, Jarrige, and Bourg (Citation2020) described low-tech approaches as “above all a set of tools, equipment and intellectual approaches, oriented towards real resources savings.” One respondent observed, “The first word of low-tech is sobriety [in resources consumption]” (Experimenter 2021). On the energy issue, Alexander and Yacoumis (Citation2018) added a further distinction stating that “a technology can be considered ‘low-tech’ if it does not require electricity or fossil fuels to operate, or if it relies on passive or direct (non-electric) solar, wind, or human-powered energy.” This is a direct response to the main environmental concerns of the Anthropocene era which are the pressure on (nonrenewable) resources and especially the ecological costs of their extraction and use (e.g., climate change). Indeed, the high-tech solutions—such as solar panels, large-scale wind turbines, smart cities, and so forth—that are now being put forward to solve this environmental crisis, aided by the development of digital technology, are of concern because of their dependence on metals, in particular rare-earth metals, and the fossil energy used for their extraction (Bihouix Citation2014; De Decker Citation2017).

Therefore, low-tech systems aim to provide a way out of this ever-increasing quest for resources, either by dismissing nonrenewable resources or by using them parsimoniously, in comparison to a conventional alternative (De Decker Citation2017). This concept can be easily illustrated by citing famous low-tech examples such as the solar oven or the Piggott wind turbine. However, it refers more broadly to any material- or energy-sobriety strategy that helps reduce or substitute the use of nonrenewable resources in technology: from using warm clothing instead of increasing the room temperature to encouraging permaculture. The mid-level concepts linked to KLTP 1 are sobriety and decarbonization.

KLTP 2: new or extended service lives

This principle combines a set of heterogeneous strategies and practices that have the common goal of keeping objects in the cycle of use for as long as possible regardless of the uses and motivations for doing so (e.g., environmental, social). These strategies are (1) the use of robust technical systems designed to last over time, (2) the use of repairable technical systems, and (3) the recovery and diversion of objects and materials. These actions are foundational to the low-tech way of thinking. As stated by Grimaud, Philippe, and Vidal (Citation2017), “maintaining is the ultimate low-tech move.” This statement can be explained by the historical origin of what is now called low-tech. Low-tech was the first simple, robust, and easily repairable technique used in environments constrained by a lack of material and/or financial resources (Abrassart, Jarrige, and Bourg Citation2020). This was the case in Europe before the Industrial Revolution and it remains the case in many developing countries. The reparability and robustness of past technical systems (in the European case) were conditions sine qua non for their perpetuation in use and practice. The modern low-tech movement explicitly acts against planned obsolescence as one respondent acknowledged, “[We] try to act upstream and make sure that there are fewer obsolescent objects” (Educator 2021). This key principle seeks to revive the logic of “generalized maintenance” (Grimaud, Philippe, and Vidal Citation2017) and is organized into networks whose objectives are to divert, recover, and rehabilitate old objects to make them current (Abrassart, Jarrige, and Bourg Citation2020). The mid-level concepts linked to KLTP 2 are robustness, repair, maintenance, material/component recovery, and diversion.

KLTP 3: appropriation

Low-tech is unanimously described as appropriable which means that individuals and communities can potentially design, build, and/or operate technical objects. This concept is referenced in the literature as “democratic reappropriation of know-hows” (Grimaud, Philippe, and Vidal Citation2017), “technological sovereignty” (Abrassart, Jarrige, and Bourg Citation2020) or “technical democracy” (Florentin and Ruggeri Citation2019). Appropriation relies on an in-depth understanding of techniques. Western populations have progressively lost this knowledge, accumulated over decades of experience and practice, in exchange for the comfort and efficiency provided by new technologies, but at the expense of increased material intensity and dependence on a few industrial holdings owning most of the technological patents (Bihouix Citation2014; Roussilhe Citation2020).

Therefore, thinking low-tech presupposes reconsidering, at least partially, the conventional post-industrial relationship between people and techniques. As one actor put it, “[T]hat is what low-tech is all about, the fact that people can get hold of it and it is not something reserved for experts” (Experimenter 2021). Drawing in particular on the analyses of Ivan Illich, the low-tech movement aims to reduce society’s dependence on technical complexity and advocates for the use of human experience and skills over machines (Bihouix Citation2014; Florentin and Ruggeri Citation2019). The mid-level concepts linked to KLTP 3 are technical accessibility, do-it-yourself, and conviviality.

KLTP 4: collective networks

The low-tech sphere in France and abroad is organized above all around networks of associations and collectives whose objective is to disseminate and administer around low-tech approaches (Bihouix Citation2014). As Roussilhe (Citation2020) stated, “behind the concept of low-tech, there are human communities, knowledge, travels, passions and commitments, so this concept does not belong only to the world of ideas, it materializes in educational documents, concrete places, objects and devices created by women and men around the world.” This bottom-up approach makes the notion extremely salient for local and localized communities (Durand, Cavé, and Pierrat Citation2019). It opposes a globalized vision of materials and energy exchanges, but not of knowledge and practices. As one interviewee stated, it is a matter of “working in a network with one’s territory” (Experimenter 2021). This collective approach is justified by the development of “skills that one cannot have alone” (Designer 2021) but also to “make the link between the inhabitants” (Facilitator 2021) to renew the social links distended by industrial practices.

Thus, knowledge sharing and open source are a foundation upon which authors and actors agree (Bihouix Citation2014; Carrey and Lachaize Citation2020). According to one respondent, “[L]ow-tech only works if there is open source” (Experimenter 2021). Low-tech solutions are “real solutions for sharing” (Maker 2021). An emblematic example of this idea is the Low-Tech Lab, an association created in 2014, that has a mission to discover low-tech experiences around the world, to document them in the form of tutorials and technical documents, and to make them available in a substantial database (over 800 entries) (Low-Tech Lab Citation2022). Low-tech can thus be seen as a facilitator to build what Gauthier Roussilhe (Citation2020) calls “a technical culture,” which he defines as how societies create, disseminate, and enrich technical know-how. The mid-level concepts linked to KLTP 4 are accessible technical knowledge, networking, and cooperation.

KLTP 5: back to basics

To decrease resource consumption, many authors and actors have suggested that the debate should refocus on needs before examining the impact of technology. One interviewee stated that “[low-tech] is to go back to things that are essential…How we are going to feed ourselves, to buy vegetables, to heat our homes, to consume in general” (Maker 2021). A primary goal is therefore to satisfy those needs qualified as “essential,” “basic,” or “elementary” (Bihouix Citation2014; Carrey and Lachaize Citation2020; Hurson Citation2019; Moriarty and Honnery Citation2008). For some actors, those needs are at the bottom of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs pyramid (Maslow Citation1943). Authors, such as Roussilhe (Citation2020) prefer to use the matrix of needs developed by Manfred Max-Neef (Citation1991), because it does not rely upon a hierarchy. Instead, Max-Neef offers a distinction between needs and what he calls satisfiers. Needs are universal and the same for all cultures (for example, the need for subsistence). Satisfiers are the ways and means by which the needs are satisfied, which depend on the culture and evolve over time (Max-Neef Citation1991).

Using this terminology, the low-tech community does not question needs as much as it interrogates current satisfiers. For example, when Bihouix (Citation2014) advocates for eliminating some needs (advertising materials) and reducing others (meat consumption, cosmetic products), he refers to the practices and types of behaviors that are currently the norms to satisfy the needs of interacting and subsisting in Western countries. Specifically, low-tech proponents argue for strategies to decrease the demand for new satisfiers, in the form of products or advanced technical systems.

This reframing of issues is constrained by some criteria of performance, comfort, and usefulness (Bihouix Citation2014; De Decker Citation2017). For example, concerning reuse at the end of life, the idea is not to reuse for its own sake or to provide surplus or useless objects but to satisfy an everyday use: “[O]ur low-tech vision is to be able to recover objects and give them a daily usage by reusing them” (Facilitator 2021). A certain level of comfort and technical performance is also considered essential because the objective is not to return to the Stone Age (Bihouix Citation2014). Low-tech alternatives must instead conform to a minimal and precise function (e.g., refrigerating or heating at the right temperature, washing). The mid-level concepts linked to KLTP 5 are demand sufficiency, usefulness, and performance.

KLTP 6: limited external dependency

Low-tech thinking emphasizes the issue of autonomy, or its corollary, the dependence of communities on outside interactions (Bauwens, Hekkert, and Kirchherr Citation2020; De Decker Citation2017; Durand, Cavé, and Pierrat Citation2019). This dependence is less toward a particular resource than toward high-tech in general (Alexander and Yacoumis Citation2018). This nuance can be illustrated with the example of solar panels. Photovoltaic-type equipment can contribute to the electrical autonomy of a house or a neighborhood (i.e., independence from a centralized energy source). However, they do not prevent dependence on a high-tech value chain that consumes fossil energy and rare metals (construction of the panels). Therefore, a low-tech approach would recommend using solar panels as a last resort to a more global sobriety strategy in order to limit their number (Bihouix Citation2014). A condition put forward by one interviewee was that “you need the [low-tech with some high-tech] equipment to work even if the high-tech [part] does not” (Experimenter 2021).

Low-tech could free societies from the vulnerabilities of high-tech (e.g., dependence on fossil fuels and rare metals, price volatility) (De Decker Citation2017). In this context, actors highlight the notion of relocating production activities when possible. One interviewee mentioned the term “localism” to explain the greater reliance upon a proximate economic fabric consisting of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and social- and solidarity-based firms (Experimenter 2021). Another respondent stated that low-tech systems should “answer local needs with local resources” (Federator 2021). The mid-level concepts linked to KLTP 6 are self-sufficiency, resilience, relocating, and local sourcing.

KLTP 7: context-dependency

This principle answers the question of whether tools should be global and identical in all places or local and linked to their particular environment. One actor’s input summarizes the perspective of the low-tech movement quite well: “When we want to do something low-tech, with things we have at hand, it is often tailor-made” (Educator 2021). To design low-tech solutions is to become aware of the material but also the human constraints of a given environment which high-tech has oftentimes forgotten (Roussilhe Citation2020). As Calame and Mouchet (Citation2020) noted, “the specificity of high-tech—be it chemistry, mechanics or big data—is to rely on sophisticated tools produced far from their place of use, and mobilizing resources on a planetary level.” Instead, a low-tech approach considers the geographical, climatic, and cultural specificities of a place (Durand, Cavé, and Pierrat Citation2019; Jaglin Citation2019), which means that the satisfaction of a need will not use the same tools, the same materials, the same processes in every region. For example, dry toilets are considered low-tech in Europe and are rarely deployed. However, they are an obvious technical choice for other places because they are adapted to contexts particularly constrained by the availability of water resources. The direct transposition of the technical object itself to Europe is hardly possible (except in specific contexts). However, the approach raises notions about the underlying issues (excreta recovery, use of drinking water), which allows us to question European techniques (Roussilhe Citation2020).

The presence of these material constraints also raises questions about the notion of the scale of the proposed solutions (Bihouix Citation2014). While the scale is difficult to quantify, actors agree that it must be “small,” considering the available resources and networks. The change in scale is a real problem for actors who want to disseminate and professionalize the approaches without industrializing or risking “wasting a lot of time and energy trying to reach the greatest number of people and potentially never succeeding” (Educator 2021). One possible solution is to change the logic and to no longer think in terms of physical size but rather from the standpoint of potential influence, as one actor suggested: “Scaling up is not so much related to the size of the company, but rather to the possibility of diffusing ideas from one territory to another” (Educator 2021). The mid-level concepts linked to KLTP 7 are context-adaptation and scalability.

Quantitative analysis of low-tech key principles

shows the number of times the key principles were mentioned in the selected low-tech literature and by the actors.

Table 4. Key principle occurrence in the literature and in practice.

shows that both sides agree on appropriation. This principle was cited most frequently by the actors and in the literature. In addition, there is a priori no general agreement on collective networks, even though more than half of the authors and interviewees referred to it in their definitions of low-tech. In the literature, decreased resource consumption in terms of technology and appropriation were especially mentioned, while appropriation and new or extended service lives were relatively more frequently mentioned among the actors. Overall, except for appropriation, the highest consensus between both sides was found over technological changes. Social changes ranked second with appropriation and back to basics while the key principles related to organizational changes were the least mentioned overall (KLTPs 4, 6, and 7).

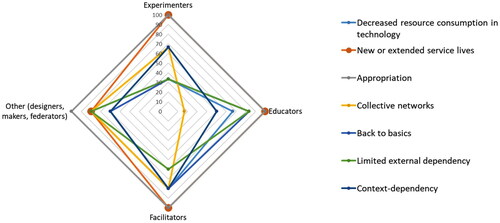

Moreover, the categorization by actor type allows the principles to be represented by category. presents the number of actors per category (in percent) who mentioned the key principles.

Facilitators agreed on a majority of the identified key principles: six of them were mentioned by at least 80% of the interviewed facilitators. Limited external dependency was the least frequently quoted for this category, although 60% did mention it. Experimenters tended to have the same profile as facilitators (they mentioned the same principles most frequently), but they put forward fewer principles: four of the seven key principles were mentioned by at least two experimenters (of three): appropriation, new or extended service lives, collective networks, and context-dependency. Finally, educators were the most divided on the low-tech principles and put forward two that are were infrequent among experimenters and, to a lesser extent, facilitators: back to basics and limited external dependency.

Thus, low-tech exhibits different representations for actors playing different roles in the low-tech sphere, within different environments, and with different objectives. These differences can be linked to the occupied function. For example, facilitators have many interactions with other actor types and this characteristic may explain their systemic view of low-tech and the consensus observed in this category. These different representations may also stem from a specific regional context which feeds different visions and priorities regarding low-tech deployment. For example, all of the educators, unlike those in the other categories, live in rural areas. These geographic differences may explain the importance given to the principle of limited external dependency, associated with local autonomy, an issue that is more complex to address in urban areas. Finally, these results must be put into perspective with regard to the biases and limitations of this quantitative study which are detailed in the next section.

Discussion

Defining low-tech: a difficult question

This article presents a framework for exploring the low-tech concept as described in recent literature and current practice. It provides a structured synthesis of the issues that drive low-tech, making the notion easier to understand and appropriate. The originality of this work lies in its cross-analysis of the scientific literature and interviews with actors that highlights a convergence on the identified key principles (all of them were cited by at least half of the literature and respondents).

This framework emphasizes the different change levels driving low-tech: technical, social, and organizational. Technical changes (e.g., repairable, less energy-intensive objects) constitute the expected definition of low-tech and are the most straightforward principles. However, principles linked to social and, to a lesser extent, organizational changes (e.g., appropriation) are equally important within the low-tech community, if not more so. Some of these issues are largely addressed in the literature on alternative technologies to sustainability that have clearly inspired the low-tech movement analyzed in this study. For example, Vetter (Citation2018) defined five dimensions of convivial technology and found “appropriateness” was one of them. Appropriateness refers to the appropriate technology movement initiated by Schumacher (Citation1973) and means “[taking] the whole situation into account, [considering] the local availability of materials and skills, and then [deciding] where a technology makes sense and where not” (Vetter Citation2018). As shown with the principle of context-dependency, this idea is shared by a majority of the authors and interviewees in this study. Therefore, according to the matrix of convivial technology (MCT) developed by Vetter (Citation2018), most of the low-tech technologies used and/or designed by the low-tech community could be considered good examples of convivial technologies. However, unlike the MCT, this framework is not intended to describe the characteristics of desirable technologies. It aims at giving a multifaceted definition of low-tech, by designating an approach rather than technical objects. Moreover, some aspects are clearly nontechnological (e.g., the back-to-basics principle).

This article suggests that low-tech research is a continuation of previous work on intermediate, convivial, and appropriate technologies, given the nature of the identified principles. Nevertheless, a comparative analysis should be carried out to draw conclusions on how these movements intersect more precisely. Such work could help refine the low-tech principles and identify their specificity compared to other alternative technology movements. One initial point gathered from this analysis is the focus on resource conservation as the main driver (especially regarding fossil energy and metal consumption), from which four of the framework principles are directly derived (KLTP 1, 2, 5, and 6). This is a general observation, and the quantitative analysis here suggests that low-tech is a heterogenous concept with differently prioritized principles depending on who is defining it. The proposed framework is an attempt to specify the main conceptual aspects of the current low-tech trajectory. Nevertheless, future research is needed to analyze the dynamics among the principles as the movement develops: how the principles are applied, their prevalence in different contexts, the tensions and synergies rising from their implementation, and the consequences for movement diffusion.

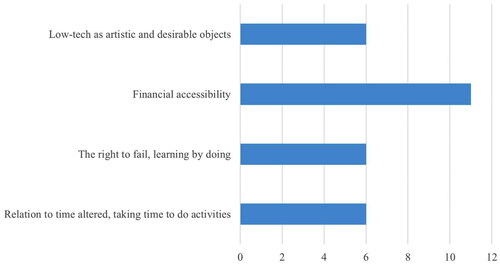

However, this work has some limitations that prevent the proposed framework from being generalized outside France and Europe more generally. A larger sample size (at least 50 respondents) would have been preferable to better validate the key principles in practice and to obtain a statistically reliable confidence level. In addition, a larger number of respondents would have provided representative stakeholder profiles, especially for designers, makers, and federators. This objective was not the focus of the analysis, but could be in future work. In addition, the key principles identified here are essentially a reflection of Western, and in the case of the actors, French low-tech thinking. This limitation influences the represented schools of thought. Works on the deployment of low-tech as applied to urban services in Africa have shown more pressing concerns about social equity, such as access to information for people with low educational levels (Jaglin Citation2019) and improving sanitary working conditions (Durand, Cavé, and Pierrat Citation2019). However, the approach followed in this work is replicable and the framework will evolve with growth in theoretical and practical knowledge on low-tech. An initial example could be the notion of financial accessibility, mentioned by many of the interviewees (see ).

Low-tech and sustainability

Although the link between low-tech and sustainability was not clearly explained by the authors or the actors, low-tech approaches obviously contribute to the efforts to “meet our own needs without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” (WCED Citation1987). Categorizing distinct key principles allows us to be more specific and to better identify the convergences and the divergences of low-tech with other well-established sustainability concepts.

Frugal innovation and circular economy are particularly close to low-tech because both of these approaches are driven by resource-constrained environments. They encourage improvements in production systems through more energy-efficient technologies and the reuse of easily accessible materials and components (KLTP 1 and 2 of the low-tech framework). However, they do not aim at the same socially transformative changes. For example, mainstream examples of frugal innovation emphasize financial accessibility while maintaining high levels of economic growth (Haudeville and Le Bas Citation2016; Tiwaris, Kalogerakis, and Herstatt Citation2014). The objective is to satisfy an unsaturated demand, especially in emerging economies, by allowing financially-constrained consumers to access new products and services (Tiwaris, Kalogerakis, and Herstatt Citation2014). This objective conflicts to some extent with KLTP 5 of the low-tech framework which advocates instead for a decrease in new product commercialization (especially high-tech products).

Low-tech approaches seek to reconnect human activities (e.g., food, housing, transportation) to the natural and the sociocultural environments where they occur (KLTP 7). With regard to the natural environment, reconnection means not only consuming fewer resources, but considering the capacity of local ecosystems to provide for these resources, in particular due to an absolute reduction in demand for new products (KLTP 5). The reconnection to the social environment is encouraged due to greater appropriation of technology by individuals (KLTP 3). This analysis coincides with a holistic and transformational vision of the circular economy, described as an “economy of voluntary moderation and sobriety” bound by the planetary boundaries framework (Arnsperger and Bourg Citation2016). However, this vision is far from dominant in current circularity discourses which are often more focused on increasing resource productivity on the basis of technological improvements (Kirchherr, Reike, and Hekkert Citation2017; Petit-Boix and Leipold Citation2018).

These divergences with mainstream strategies raise a question about the future of low-tech in its capacity to create actual transformations in society. Its popularity, especially in France, has grown in the past decade to the point of arousing the interest of public authorities and large companies. For example, in 2018, the French environmental agency organized a series of conferences on low-tech and innovations (ADEME Citation2020). However, past experiences in grassroots innovations have shown that diffusion to a larger audience might compromise the initial trajectory imagined by earlier thinkers (see, e.g., Smith Citation2005). As the low-tech movement develops, it could lose sight of principles such as appropriation (KLTP 3), back to basics (KLTP 5), and context-dependency (KLTP 7) which are currently missing in mainstream discourses on sustainability, especially discourses on circularity. These principles can be considered the “critical edge” of the low-tech movement (Smith et al. Citation2016) because its radical propositions tend to diverge from dominant high-tech approaches to technology. They are already facing challenges from various issues that emerged during the interviews such as expanding low-tech approaches at the national level and including high-tech technology within a low-tech approach.

Conclusion

The low-tech concept has come to the fore in the last few years, mainly in opposition to the techno-optimistic model proposed to solve current and future environmental crises. Several definitions of low-tech exist, offered by both academics and practitioners. They reflect diverse perspectives on how low-tech solutions can contribute to societal transformations (e.g., resource conservation, technical accessibility). This diversity potentially enriches the concept but also adds to its vagueness, preventing its specificity from being identified in comparison to more mainstream sustainability concepts. Therefore, this article developed a seven-principle framework to categorize low-tech concepts using an abductive approach accounting for the perspectives found in the literature and articulated by relevant actors.

The framework emphasizes the three types of sociotechnical changes desired by low-tech proponents, each fed by distinct principles. Principles related to technical changes (i.e., decreased resource consumption in technology and new or extended service lives) are the most expected given the origins of the low-tech movement (opposing advanced technology and programmed obsolescence). These principles are also shared by other sustainability concepts, especially those focused on resource conservation, such as the circular economy. However, the findings suggest that the principles linked to social and, to a lesser extent, organizational changes (e.g., appropriation) are equally if not more important among members of the low-tech community. This principle, along with back to basics (reducing the demand for new products) and context-dependency (considering the suitability of a technology given local resources and social context) distinguish low-tech from mainstream sustainability discourses, especially on circularity. These principles can be assimilated into what Smith et al. (Citation2016) called a “critical edge”—radical propositions that allow the continual challenge of dominant high-tech approaches to technology to create societal transformations. The remaining principles (collective networks and limited external dependency) are inherent parts of low-tech approaches but are more consensual motivations in sustainability discourses.

This study opens diverse research avenues. First, the framework could be used to illustrate various low-tech representations that differ between actors and geographical contexts. Second, delineation of the defining principles advanced in this article could be a starting point to analyze how the low-tech movement intersects with other movements of alternative technology. Finally, the dynamics between the different principles are likely to evolve as the movement diffuses into society and subsequent analyses could provide indications as to how it may move away from or remain close to its initial motivations.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the EcoSD French network in the framework of a collaborative research project (2020–2021). The authors thank all the project members, especially its coordinator, Alexandre Gaultier, for their help in conducting this work. They also thank the low-tech actors who kindly responded to the interview requests and the reviewers who helped bring significant improvements to an earlier version of this manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1 For details on the collaborative research project “Viabilité Low-Tech (Low-Tech Viability)” see https://lowtri.github.io.

References

- Abrassart, C., F. Jarrige, and D. Bourg. 2020. “Introduction Au Dossier Low-Tech: Low-Tech et Enjeux Écologiques: Quels Potentiels Pour Affronter Les Crises?” [Introduction to the Low-Tech Special Issue: Low-Tech and Ecological Issues: Which Potentials to Face the Crises?] La Pensée Ecologique 5: 1. doi:10.3917/lpe.005.0001.

- Agence de la Transition Écologique (ADEME). 2020. Cycle de Conférences 2018: Approche Systémique, Source d’inspiration Des Politiques Publiques? [Conference Series 2018: System Approach as a Source of Inspiration for Public Policy?] Paris: ADEME. https://ile-de-france.ademe.fr/mediatheque/videos/cycle-de-conferences-2018/la-demarche-low-tech-comme-approche-systemique-de-linnovation

- Alexander, S., and P. Yacoumis. 2018. “Degrowth, Energy Descent, and ‘Low-Tech’ Living: Potential Pathways for Increased Resilience in Times of Crisis.” Journal of Cleaner Production 197: 1840–1848. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.09.100.

- Arnsperger, C., and D. Bourg. 2016. “Vers Une Économie Authentiquement Circulaire – Réflexions Sur Les Fondements d’un Indicateur de Circularité” [Towards a Genuinely Circular Economy – Reflections on the Foundations of a Circularity Indicator]. Revue de l‘OFCE 145 (1): 91–125. doi:10.3917/reof.145.0091.

- Bauwens, T., M. Hekkert, and J. Kirchherr. 2020. “Circular Futures: What Will They Look like?” Ecological Economics 175: 106703. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2020.106703.

- Bihouix, P. 2014. L’âge Des Low Tech: Vers Une Civilisation Techniquement Soutenable [The Low-Tech Era: Towards a Technically Sustainable Civilization.] Paris: Editions du Seuil.

- Bocken, N., S. Short, P. Rana, and S. Evans. 2014. “A Literature and Practice Review to Develop Sustainable Business Model Archetypes.” Journal of Cleaner Production 65: 42–56. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2013.11.039.

- Calame, M., and C. Mouchet. 2020. “Quelles Techniques Pour l’agriculture Écologique?” [Which Techniques for Ecological Agriculture?] La Pensée Ecologique 5: 2. doi:10.3917/lpe.005.0002.

- Calisto Friant, M., W. Vermeulen, and R. Salomone. 2020. “A Typology of Circular Economy Discourses: Navigating the Diverse Visions of a Contested Paradigm.” Resources, Conservation and Recycling 161: 104917. doi:10.1016/j.resconrec.2020.104917.

- Carrey, M., and S. Lachaize. 2020. “La Recherche Scientifique En Low-Tech : Définition, Réflexions Sur Les Pistes Possibles, et Illustration Avec Un Projet de Métallurgie Solaire” [Low-Tech Scientific Research: Definition, Reflections on Possible Paths, and Illustration with a Solar Metallurgy Project]. La Pensée Ecologique 5: 7. doi:10.3917/lpe.005.0007.

- De Decker, K. 2017. “Comment Bâtir Un Internet Low Tech” [How to Build a Low-Tech Internet]. Techniques & Culture 67: 216–235. doi:10.4000/tc.8489.

- de Jong, M., S. Joss, D. Schraven, C. Zhan, and M. Weijnen. 2015. “Sustainable–Smart–Resilient–Low Carbon–Eco–Knowledge Cities: Making Sense of a Multitude of Concepts Promoting Sustainable Urbanization.” Journal of Cleaner Production 109: 25–38. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.02.004.

- Dubois, A., and L.-E. Gadde. 2002. “Systematic Combining: An Abductive Approach to Case Research.” Journal of Business Research 55 (7): 553–560. doi:10.1016/S0148-2963(00)00195-8.

- Durand, M., J. Cavé, and A. Pierrat. 2019. “Quand Le Low-Tech Fait Ses Preuves: La Gestion Des Déchets Dans Les Pays Du Sud Technologie Pour Les Pauvres Ou Sobriété Écologique?” [When Low-Tech Proves Its Worth: Waste Management in the South Technology for the Poor or Ecological Sobriety?]. Urbanités 12: 1–13.

- Florentin, D., and C. Ruggeri. 2019. “Ville (S)Low Tech et Quête d’une Modernité Écologique” [(S)Low Tech City and the Quest for an Ecological Modernity]. Urbanités 12: 1–8.

- Grimaud, E., Y. Philippe, and D. Vidal. 2017. “Low Tech, High Tech, Wild Tech: Réinventer La Technologie?” [Low Tech, High Tech, Wild Tech: Reinventing Technology?]. Techniques & Culture 67: 12–29. doi:10.4000/tc.8464.

- Haudeville, B., and C. Le Bas. 2016. “L’Innovation Frugale: Une Nouvelle Opportunité Pour Les Économies En Développement?” [Frugal Innovation: A New Opportunity for Developing Economies?]. Mondes En Développement 173 (1): 11–28. doi:10.3917/med.173.0011.

- Hector, P., and A. Botero. 2022. “Generative Repair: Everyday Infrastructuring Between DIY Citizen Initiatives and Institutional Arrangements.” CoDesign 18 (4): 399–415. doi:10.1080/15710882.2021.1912778.

- Holden, M., C. Li, and A. Molina. 2015. “The Emergence and Spread of Ecourban Neighbourhoods Around the World.” Sustainability 7 (9): 11418–11437. doi:10.3390/su70911418.

- Hurson, L. 2019. De La Démesure à La Juste Mesure: Le Low-Tech, Entre Confort et Volonté de Changer [From Excess to Appropriate Balance: Low-Tech, Between Comfort and Will to Change]. Grenoble: Dépôt Universitaire de Mémoires Aprés Soutenance. https://dumas.ccsd.cnrs.fr/dumas-01996417.

- Illich, I. 1973. Tools for Conviviality. New York: Harper & Row.

- Jaglin, S. 2019. “Basses Technologies et Services Urbains En Afrique Subsaharienne : Un Low-Tech Loin de l’écologie.” [Low-Tech and Urban Services in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Low-Tech Far from Ecology]. Urbanités 12: 1–14.

- Kerschner, C., and M.-H. Ehlers. 2016. “A Framework of Attitudes Towards Technology in Theory and Practice.” Ecological Economics 126: 139–151. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2016.02.010.

- Kerschner, C., P. Wächter, L. Nierling, and M.-H. Ehlers. 2018. “Degrowth and Technology: Towards Feasible, Viable, Appropriate and Convivial Imaginaries.” Journal of Cleaner Production 197: 1619–1636. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.07.147.

- Kirchherr, J., D. Reike, and M. Hekkert. 2017. “Conceptualizing the Circular Economy: An Analysis of 114 Definitions.” Resources, Conservation and Recycling 127: 221–232. doi:10.1016/j.resconrec.2017.09.005.

- Lepawsky, J. 2020. “Planet of Fixers? Mapping the Middle Grounds of Independent and Do-It-Yourself Information and Communication Technology Maintenance and Repair.” Geo: Geography and Environment 7 (1): 1–17. doi:10.1002/geo2.86.

- Low-Tech Lab. 2022. Low-Techs for a Sustainable and Desirable Society! Concarneau: Low-Tech Lab. https://lowtechlab.org/en

- Luederitz, C., D. Lang, and H. Von Wehrden. 2013. “A Systematic Review of Guiding Principles for Sustainable Urban Neighborhood Development.” Landscape and Urban Planning 118: 40–52. doi:10.1016/j.landurbplan.2013.06.002.

- Maslow, A. 1943. “A Theory of Human Motivation.” Psychological Review 50 (4): 370–396. doi:10.1037/h0054346.

- Max-Neef, M. 1991. Human Scale Development: Conception, Application and Further Reflections. New York: Apex Press.

- Moriarty, P., and D. Honnery. 2008. “Low-Mobility: The Future of Transport.” Futures 40 (10): 865–872. doi:10.1016/j.futures.2008.07.021.

- Petit-Boix, A., and S. Leipold. 2018. “Circular Economy in Cities: Reviewing How Environmental Research Aligns with Local Practices.” Journal of Cleaner Production 195: 1270–1281. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.05.281.

- Radjou, N., and J. Prabhu. 2015. Frugal Innovation: How to Do More with Less. New York: Public Affairs.

- Rockström, J., W. Steffen, K. Noone, Å. Persson, F. Chapin, E. Lambin, T. Lenton, et al. 2009. “Planetary Boundaries: Exploring the Safe Operating Space for Humanity.” Ecology and Society 14 (2): 32. doi:10.5751/ES-03180-140232.

- Roussilhe, G. 2020. “Une Erreur de Tech” [A Tech Mistake]. https://gauthierroussilhe.com/articles/une-erreur-de-tech

- Schumacher, F. 1973. Small is Beautiful: Economics as if People Mattered. London: Blond & Briggs.

- Smith, A. 2005. “The Alternative Technology Movement: An Analysis of Its Framing and Negotiation of Technology Development.” Research in Human Ecology 12 (2): 106–119.

- Smith, A., T. Hargreaves, S. Hielscher, M. Martiskainen, and G. Seyfang. 2016. “Making the Most of Community Energies: Three Perspectives on Grassroots Innovation.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 48 (2): 407–432. doi:10.1177/0308518X15597908.

- Steffen, W., K. Richardson, J. Rockström, S. Cornell, I. Fetzer, M. Elena, R. Biggs, et al. 2015. “Planetary Boundaries: Guiding Human Development on a Changing Planet.” Science 347 (6223): 1259855. doi:10.1126/science.1259855.

- Tiwaris, R., K. Kalogerakis, and C. Herstatt. 2014. “Frugal Innovation and Analogies: Some Propositions for Product Development in Emerging Economies.” In Proceedings of the R&D Management Conference, Stuttgart, June 3–6. doi:10.15480/882.1173.

- Vetter, A. 2018. “The Matrix of Convivial Technology – Assessing Technologies for Degrowth.” Journal of Cleaner Production 197: 1778–1786. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.02.195.

- World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED). 1987. Our Common Future: Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development. Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/139811.

Appendices

Low-tech concepts from the literature (mid-level codes)

We first retrieved main concepts from the low-tech literature. The mid-level codes constitute the process of developing the key principles (see in the methods section). They are an intermediary classification before identifying the key principles. shows these concepts with the number of authors in the final corpus that developed them in their definition of low-tech systems. As shown on the figure, efforts to reduce resource consumption is cited the most often, followed by the use of convivial techniques.

Activity profiles of the interviewees

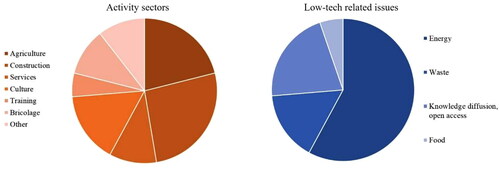

presents the activity sectors and low-tech-related issues addressed by the actors. While the activity sectors are quite diverse, and are even sometimes difficult to classify for some actors, the low-tech-related issues concern mainly energy (its production and use).

provides examples of low-tech objects or objects used from a low-tech perspective cited by the interviewees. These are examples that represent practical implementation of their low-tech approach which is either actual or projected. The objects mentioned are not necessarily low-tech (e.g., kettle) but the action carried out around these objects are part of the low-tech approach (e.g., design or repair of a kettle).

Table A1. Examples of low-tech objects and objects used from a low-tech perspective cited by the interviewees.

Table A2. The interview grid.

The interview grid used in this study

1. Date:

2. Interviewers:

3. Tools and Recording:

4. Presentation of the project’s context, the role, and so forth

5. Do you accept that I record this interview?

Low-tech concepts from the literature as expressed by the actors interviewed

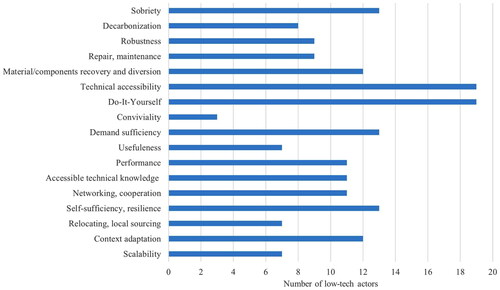

shows the number of actors that mentioned the low-tech concepts derived from the literature (). Three interviewees mention each concept at least once, suggesting a general convergence toward these concepts, to varying degrees. The discrepancies in occurrence observed between the literature () and practice () are explained in the article at the key-principles level. However, it is possible to point out here that actors tend to cite more often than the literature the technical simplicity of low-tech and its appropriation, even though it is still a dominant trait on both sides. Conviviality is the least mentioned concept among actors, while it is quite frequent among authors. This can be explained by the large influence of Illich’s work on current academic literature while the appropriation of the conviviality concept by actors can be easier to interpret as an improved appropriation of technical objects in general.

The interviews also revealed other important concepts frequently mentioned by the actors (). The most cited is financial accessibility which reflects the necessity to develop and promote either affordable ways of manufacturing common goods (e.g., wood stoves) or economic models relying on donation systems. Several actors link closely this necessity with the issue of time and users’ involvement: the products’ costs decrease because people take time to learn by themselves how to build and repair accessible versions of these products.