Abstract

A central promise of urban experiments (UEs) is to create sites for social learning. However, research on such learning in sustainability transitions still lacks conceptual clarity and empirical evidence. This article helps to close this gap by analyzing how social learning emerges from urban experimentation. It adopts a transactional understanding of learning induced by disruptions of everyday habits and distinguishes cognitive, normative, and relational learning processes. Further, the additional dimension of socio-material learning is derived to account for changes in understanding or interpreting material realities. These concepts serve an analytical framework for a case study of two transition experiments carried out as part of the transdisciplinary research project “Dresden – City of the Future.” The two UEs strive to initiate local sustainability transitions pertaining to participatory governance of urban districts and co-creation of a livable schoolyard. The empirical results illustrate how interventions by the two UEs induced learning in the sense of changes of cognitive understandings, norms, relations among people, as well as between people and their socio-material environments. The experiments encouraged individual and collective learning and in particular the formation of collective identities and interpretations of specific places. By comparing two UEs, we further show differences in learning regarding the actor groups, namely that the majority of learning processes in the first experiment dealt with bridging the gap between prevalent routines of the school community and novel habits introduced by the initiators of the experiment. Participants of the second experiment were socio-ecologically minded from the outset and therefore fewer learning processes took place in this regard.

Introduction

In urban experiments (UEs) abstract and complex issues of sustainability transitions (STs) are translated into concrete actions in particular places (Evans et al. Citation2016, 1). Sengers, Wieczorek, and Raven (Citation2019, 2) point out that in UEs “a variety of real-world actors commit to the messy experimental processes tied up with the introduction of alternative technologies and practices in order to purposively re-shape social and material realities.” The experiments intervene in real-world contexts with the aim of changing local or even societal regimes (Castán Broto and Bulkeley Citation2013). Various definitions of UEs all posit the centrality of learning (Evans et al. Citation2016; Karvonen and van Heur Citation2014; Matschoss et al. Citation2021; Sengers, Wieczorek, and Raven Citation2019). Learning is seen as a “driver to plant the seeds of change that may induce a broader transformation” (Weiland et al. Citation2017, 1). More specifically, such learning should allow the temporally and spatially constrained UEs to unfold an impact beyond the context of any single intervention (Luederitz et al. Citation2017; Weiland et al. Citation2017).

The recognition of learning as an important seed is countered by the criticism that learning and its relation to STs has hitherto been insufficiently conceptualized (Matschoss et al. Citation2021; van Mierlo et al. Citation2020; Van Poeck, Östman, and Block 2020). A recent special issue on learning in STs criticizes conceptual haziness, deficient application of well-established fields of research, and lack of empirical evidence (van Mierlo et al. Citation2020; Van Poeck, Östman, and Block 2020). The criticisms point to several tasks for future research in ST studies, in particular the need for a precise definition of learning that is clearly demarcated from other outcomes of UEs (Reed et al. Citation2010).

We begin our article by establishing a definition of social learning before going on to address how learning comes about and which specific processes of social learning emerge from urban experimentation. We first introduce a transactional understanding to conceptualize the learning processes and afterwards differentiate four dimensions of learning (cognitive, normative, relational, and socio-material) that refer to changes in cognitive understandings, norms and values, and identities of individuals and communities (McFadgen and Huitema Citation2017), as well as their relations to places and materials. This fourth dimension of socio-material learning has not previously been considered in ST studies. It is based on work by educational scholars who have outlined the role of materials in the learning process (Hofverberg and Maivorsdotter Citation2018; Östman Citation2010).

Our investigation aims to answer two specific research questions: (1) How do urban experiments initiate learning processes? (2) Which processes of social learning emerge from urban experimentation? Here our focus is on short- and middle-term learning processes rather than long-term learning or other dynamics emerging from UEs. Based on the argument that UEs are conducted to foster social learning (Sengers, Wieczorek, and Raven Citation2019), we contribute to understand learning dynamics arising from experimentation.

In a case study of two UEs, we apply our theoretical framework to examine the four proposed kinds of learning processes (see also the methods section). The UEs are embedded in a real-world laboratory run by the transdisciplinary research project “City of the Future” in Dresden, Germany. The objective of this real-world laboratory is to co-create knowledge through the collaborative efforts of scientists, residents, and civil society initiatives, the business community, public officials, and politicians. The first UE, called “Schools as Living Spaces Created Together,” aimed to collectively rebuild a schoolyard in a sustainable manner. Here participatory methods and approaches of environmental education were introduced to the school community to empower students, teachers, and parents. The second UE “District Funds and Councils for Sustainable and Active Neighborhoods” aimed to transform urban districts by strengthening participation and self-organization. For this purpose, district councils were elected to decide on the funding of micro-projects in the districts. The outcomes of each UE are presented in the results section below. In our empirical analysis we focus on micro- and meso-level processes of learning and changes in habits. Furthermore, we aim to sketch avenues for analyzing how learning might contribute to STs at a macro level by discussing the role of power and materiality. Both shape learning processes but were also found to crucially affect the potentials of broader change (Avelino Citation2017; Avelino and Wittmayer Citation2016; Frantzeskaki, van Steenbergen, and Stedman Citation2018). In this context, we also discuss the involvement of different actor groups. We thereby refer to transition management, an approach that operationalizes transition governance through the development of tools such as transition arenas, scenarios, and experiments. Transition management highlights the role of sustainability pioneers who are referred to as frontrunners (Loorbach Citation2010). The empirical findings are subsequently compared and discussed and the final section of this article offers conclusions.

Learning through urban experimentation

To introduce the state of research on social learning in STs, we define social learning, address the questions of how learning comes about, and discuss what is (or should be) learned in STs.

What is social learning?

Striving to counteract the current fuzziness in sustainability transition studies when distinguishing learning from other processes, we start with a definition of learning by Reed et al. (Citation2010): Learning is (1) a change in understanding at the individual level; (2) situated within communities of practice or wider social units; and (3) taking place through social interaction. This definition is frequently applied in ST studies. It integrates both the individual and social characteristics of learning (e.g., Beers et al. Citation2014; Herrero, Dedeurwaerdere, and Osinski Citation2019; van Mierlo and Beers Citation2020) without overemphasizing the role of consensus and communities for learning. Further, the definition precisely states that learning consists of a change in understanding and accordingly, other changes, for example at the behavioral level, may well be consequences of learning, but not learning itself.

How does learning come about?

To conceptualize the emergence of learning through UEs, we will build on transactional learning theory. This learning theory is essentially based on the work of pragmatist thinker John Dewey and views learning as an interplay of intrapersonal, interpersonal, institutional, and material aspects (Dewey Citation1938, Citation1934; Van Poeck, Östman, and Block 2020; Van Poeck and Östman Citation2021). It emphasizes the constant reciprocal relations of individuals, communities, and materials going beyond single interactions. They are therefore referred to as transactions.

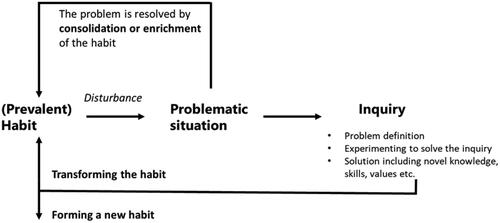

Learning is shaped by an interplay of intrapersonal aspects as well as (interpersonal, institutional, and material) aspects of the environment and, in turn, shapes a continuous, reciprocal, and simultaneous transformation of both the persons involved and their environment. Learning is induced by a disruption of everyday life, creating a problematic situation that does not align with prevalent assumptions and frames (see ). In other words, encounters of the acting individual with the external world can interrupt accustomed ways of thinking and acting - and encourage the actor to reflect on them (Van Poeck and Östman Citation2021). The external world represents all supra-individual elements such as discourses or materials. Disturbances can arise from different kinds of transactions such as discussions within a community (Didham, Ofei-Manu, and Nagareo Citation2017; Herrero, Dedeurwaerdere, and Osinski Citation2019), encounters with a novel environment (Pohlmann Citation2020; Van Poeck, Östman, and Block 2020) or with novel societal narratives or values (Chabay et al. Citation2019). The disruption creates a problematic situation since the encounter challenges previous assumptions and understandings of the person.

Figure 1. Transactional learning theory.

Source: Adapted from Van Poeck et al. (Citation2021, 158).

Following the conceptualization of Van Poeck, Östman, and Block (2020), intense learning is stimulated if the problematic situation cannot be handled by the modification of existing habits but requires an inquiry (a reflexive process). Such an inquiry, triggered by the disturbance, results in increased specification of the current problem and testing different potential solutions. Those solutions need to bridge the gap that arose between “what stands fast (e.g., what participants already know, what they have experienced before) and what is encountered in the present situation” (Van Poeck and Östman Citation2021, 162). Every inquiry involves processes of privileging. Novel knowledge, values, and associations that are privileged thereby become part of current understandings (while others are excluded from the privileging and, thus, the ongoing meaning-making). In this way, inquiries may generate new knowledge, skills, or meanings and, consequently, new habits may be formed, or old habits become transformed. However, a disturbance of habits does not necessarily induce an inquiry but can also be overcome by a slight adaptation of habits. This transactional view of learning as a process integrated into everyday life aligns well with the notion of UEs as interventions dealing with real-world problems (Schneidewind and Singer-Brodowski Citation2015).

What is learned?

Based on the abovementioned definition of social learning, this subsection investigates which aspects of understandings and frames can be transformed through learning. Transactional learning theory claims that intrapersonal, interpersonal, institutional, and material aspects affect learning and are also subject to it (Ardoin and Heimlich Citation2021; Van Poeck, Östman, and Block 2020). In the following we will distinguish four learning dimensions capturing these intrapersonal, interpersonal, institutional, and material aspects that may change due to learning: Cognitive and normative learning address changes on an intrapersonal level such as knowledge and norms and have already been discussed in the sustainability transition literature (Mogalle Citation2001; Walter et al. Citation2007). Interpersonal and institutional aspects are summarized as relational learning (Grunwald Citation2004; McFadgen and Huitema Citation2017; Walter et al. Citation2007; Weiland et al. Citation2017; Wiek, Kay, and Forrest Citation2017). We further introduce the dimension of socio-material learning to capture changes in the interpretation and understanding of socio-material configurations.

With reference to our definition of social learning, we first summarize cognitive learning as changes in understanding relating to system knowledge. Such knowledge includes insights on the current state and can refer to global (e.g., report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) or local sustainability issues (e.g., everyday consumption practices) (Grunwald Citation2004; Mogalle Citation2001). Mogalle (Citation2001, 12) specifies that system knowledge consists of natural-scientific understandings of environmental problems (e.g., effects of carbon-dioxide emissions) as well as knowledge about human actions, their causes, and the structures in which they are embedded. System knowledge enables individuals to better understand how concrete actions affect ecological and social configurations.

Second, we conceptualize normative learning as reflecting norms and objectives. It includes knowledge on desirable natural states as well as societal future visions and lifestyles in accordance with them (Mogalle Citation2001, 12). Outcomes are changed visions on desirable developments or revised preferences (Walter et al. Citation2007). Even though cognitive and normative learning are characterized here as intrapersonal aspects, we emphasize their co-constitution by social contexts. Knowledge and norms always emerge in relation to specific social contexts and unfold their meaning in relation to them.

Third, relational learning captures interpersonal and institutional aspects. Since STs require the forging of new alliances, learning processes in and between different communities are particularly relevant (Beers et al. Citation2019). Correspondingly, relational learning can involve (re-)negotiating or establishing a collective understanding, assumptions or attitudes that are relevant for the decision-making frames of individuals. Alongside consensus-building, relational learning encompasses other less consensual relational developments that support UEs (on the overemphasis of consensus cf. Wildemeersch and Vandenabeele Citation2007). One concrete example would be when a mayor does not support the approach of a transition initiative but accepts it as a vital partner for specific urban developments. Relational learning is closely associated with cognitive and normative learning; yet instead of knowledge and visions, it concerns relational traits such as recognition of each other, trust, attitudes, or some collective vision that matters for individual understanding.

Finally, socio-material learning captures changes in interpretations or relations to socio-material realities that were previously taken for granted. Both practice theorists and educational scholars argue for the relevance of materiality for practices and learning respectively. Starting by criticizing ST studies for overlooking the relevance of practices, Shove and Walker (Citation2010) outline how materials enable and at the same time confine practices. They argue that a rehearsed use of materials becomes part of a routine and thereby contributes to stability (Öztekin and Gaziulusoy Citation2019; Shove and Walker Citation2010). Educational scholars stress that socio-material relations enter the learning process and can also underlie transitions through learning (Hofverberg and Maivorsdotter Citation2018; Van Poeck, Östman, and Block 2020). The role of materials is exemplified in the case study of Hofverberg and Maivorsdotter (Citation2018), which shows how pieces of waste fabric stimulated the idea for a new product. Knowledge and ideas of the fabrics became part of the learning process (this was particularly apparent because ideas differed on what to do with the fabrics). While Hofverberg and Maivorsdotter (Citation2018) focus on the relevance of materials in learning processes, we are also interested in socio-material learning outcomes. An example would be if socio-material understandings of the fabrics in the above cited case study changed. Participants might start to perceive the fabrics not only as leftovers but also as valuable resources.

We acknowledge that there are overlaps between the dimensions. Relational learning within a group, for instance, will presumably also affect their socio-material understandings. However, we argue to make those analytical distinctions to allow for precise descriptions and interpretations of which learning processes take place. The transactional perspective (Van Poeck and Östman Citation2021) as well as the four dimensions of learning (see ) provide the analytical framework for the following analysis.

Table 1. Dimensions of learning processes

Analysis of transition experiments: case-study design

We adopted a qualitative case-study design that compares two UEs in order to gain contextualized knowledge on the phenomenon of social learning. This research design allowed for the collection of context sensitive data over a period that have high explanatory power for the processual and context-dependent phenomenon of learning (Cundill et al. Citation2014; Yin Citation2008). To elucidate our empirical methods, we describe the selection of cases and introduce the two UEs immediately below before discussing the methods of data collection and analysis in the subsequent subsection.

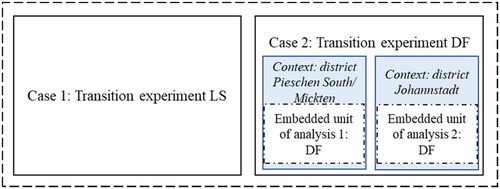

Case-study design

We searched for UEs which (1) strive to initiate social learning among different actors; (2) aim to contribute to (local) STs; and (3) are accessible to research over a period. To this end, we selected two resident-led UEs that are part of the transdisciplinary research project “Dresden – City of the Future.” The general goal of this project is to co-create knowledge through the activities of both scientists and residents. While both chosen UEs meet all criteria, their target groups, motivation, and thematic focus differ (see ). As they constitute dissimilar cases in a similar context, their comparison allows us to analyze learning in different UEs and settings.

Table 2. Comparison of the two UEs

The first considered UE, “Schools as Living Spaces Created Together” (LS), aimed to empower a school community by introducing methods supporting environmental education, encouraging participatory planning, planting of vegetation, and building activities. The voluntary project team initiated the UE and collaborated with a school and the municipality. A highlight of this UE was a construction and planting week, during which specialists guided students in collectively building playground equipment, which afterwards was permanently installed in their schoolyard.

The second UE, “District Funds and Councils for Sustainable and Active Neighborhoods” (DF), provided a funding tool for micro-projects run by residents or associations within the district (Stadtteil). Informed by different (sustainability) criteria, elected district councils decided which projects should receive funding. Based on the underlying premise that residents are particularly interested in improving their local living environment, this UE explored new modes of participatory governance in the two districts of Johannstadt and Pieschen-South/Mickten (for readability in the following summarized as Pieschen). The project team in Johannstadt was able to draw on experiences from a neighborhood council established in 2015. From mid-2019 until the end of 2021, 45 projects were funded in Johannstadt and 29 in Pieschen. Typical examples include the purchase of a cargo bike, the setting up of a district festival, and the acquisition of mobile greening. Due to the project implementation in two separate districts, our case-study design features two embedded units of analysis in this second case (see ).

Figure 2. Multiple embedded case design.

Source: Adapted from Yin (Citation2008).

A major limitation of the case-study design is the small number of cases that share a common context, which affects the transferability of results due to possible variations in the conditioning aspects of learning processes in different contexts. However, following Geertz (Citation1973), we argue for the value of small-n in-depth case studies because they allow to analyse complex phenomena in detail in their real-world context. Furthermore, the observation period of two years is too short to analyze long-term processes, which would also entail a more detailed examination of the cause-effect relationships of experimentation and subsequent learning due to the temporal detachment.

Data collection and analysis

We face several challenges regarding empirical research on learning. Learning in everyday life comprises cumulative and often unconscious processes that cannot be directly observed or experienced by researchers (Ardoin and Heimlich Citation2021). Learning processes need to be distinguished from other dynamics arising from an intervention (Gould et al. Citation2019; Reed et al. Citation2010). Further, researchers must ensure that identified learning processes are indeed related to the investigated UE. We will not be able to resolve all these analytical problems but outline how our empirical procedure attempted to deal with them.

Applying the principle of triangulation, we combined different modes of data collection to compensate for the shortcomings of individual methods (Yin Citation2008) and to better understand the complex and invisible processes of learning. By making use of diverse data-collection modes in this way, we were able to accompany the UEs over their entire duration, and thus to capture possible encounters and potential learning processes caused by transactions of the UEs. We conducted participatory observations, qualitative semi-structured interviews, focus-group discussions, and document analyses. We observed strategic meetings of the organizational teams, negotiations with politicians and the administrative staff, and participatory events (see Appendix 2). Reflection workshops scheduled for all ten UEs of the transdisciplinary research project “Dresden – City of the Future” served as focus groups (see Appendix 3). These were designed to encourage participants to reflect on and exchange experiences on what was learned. The collective reflection should serve as a stimulus and potentially reveal previously unconscious processes. The organizational teams provided us with project plans and email conversations so that we could keep track of developments between our participatory observations. Based on the participatory observations and the documents, we selected interview partners from different sectors (e.g., civil society or public sector) and with a varying degree of involvement (e.g., organizational team or participant) to capture the learning processes of members from diverse communities (see Appendix 1). Due to pandemic restrictions, some of the observations and most of the interviews were conducted online with some exceptions to not exclude persons.

Our analysis focused on interview data collected at the end of each UE, when we systematically asked the participants what they had learned regarding cognitive, normative, relational, and socio-material aspects. The interviews were recorded and transcribed for a detailed two-step data analysis. In the first step, a qualitative content analysis (Mayring Citation1994) identified passages that indicated a disturbance of habits, a problematic situation, or a change related to one of the aspects specified in the analytical framework (see Appendix 4 for the coding categories). The software tool MaxQDA was used to deal with the large volume of interview data. To ensure inter-coder reliability, several pretests were conducted to compare the coding of a text by three different coders (Mayring Citation1994, 162). In the second step, we closely examined the coded text passages to understand if and how learning processes took place. Since it is not possible to identify causal relationships, we searched for indicators that related identified changes to encounters and subsequent reflections induced by the UE. In so doing, we attempted to distinguish slight adaptions in habits from learning due to reflexive processes (including an inquiry). Data might include, for instance, reflections that are direct responses to encounters in the context of the UE such as a voiced argument, an email, an impulse, or a collaborative activity. While sometimes interviewees reflected on their learning process in a very detailed manner, elsewhere we needed to consult other data sources. In contrast to the interview data, these documents cover the whole duration of each UE, thereby helping us pinpoint which cognitive, normative, relational, and socio-material notions the participants held before taking part in the UE and which changes occurred.

Case studies: social learning through local experimentation

This section presents empirical insights on each UE structured along the four dimensions of learning processes. Of course, much more happened in the two UEs over the two and a half years than we can depict here. We therefore focus on the most common learning processes. We illustrate at least one exemplary learning process in detail by specifying disturbance, problematic situation, inquiry, and potential effects on habits. We further aim to shed light on the learning dynamics among different actor groups. To do so we include some less detailed interpretations and summaries of learning experiences.

Schools as living spaces created together (LS)

The main actors of LS were the organizational team initiating the UE, the school community including teachers, educators, students, and their parents. Primarily two offices of the public administration were involved in the UE: the school-administration office (Schulverwaltungsamt) was consulted with regard to the planning and approval of structural modifications of the schoolyard. The Office of City of the Future (DCF office), which was created as a horizontal unit within the Mayor’s Office to facilitate cooperation between the municipality and the UE, adopted an advisory and intermediary role. LS was anchored within the school community, an existing institution with prevalent habits. Although the principal could be convinced to take part in the UE, her motives for participating differed greatly from those of the organizational team. Teachers and educators had to go along with their principal’s decision and some of them were very skeptical about the UE in the beginning. The main interventions were (1) the intensive planning process regarding the participatory and ecological rebuilding of the schoolyard involving all three actor groups and (2) the collective construction and planting week of the organizational team and school community.

Cognitive learning

The week of collective construction and planting disrupted everyday habits, confronting previous knowledge with new insights on ecosystems. The head of the after-school care center, for instance, brought up two encounters:

I overheard the kids saying that insect hotels need to face south. I also noticed that all our built insect hotels have the same orientation. I didn’t know that before. I just hung mine on the apple tree at home. [LS6]Footnote1

Another learning experience of a member of the organizational team refers to the reuse of old concrete slabs for the foundation of a playing area [LS2]. Here, not only the novel idea of reuse caused a disturbance, but the interviewee described a general problem that she recognized regarding the participatory and ecological renewal of the schoolyard: The school administration had just re(-built) some areas of the schoolyard. Replacing those newly built elements with sustainable but new materials would not be sustainable. This illustrates her ongoing inquiry for an unresolved problematic situation. The idea of reusing concrete slabs proposed by another team member presented to some extent a solution to that dilemma. Confirming that she privileged this idea, she stated to consider doing the same in future projects. This indicates, firstly, cognitive learning as she acquired a novel strategy for dealing with concrete slabs and, secondly, the prospect that she might form novel habits in the future.

While we outlined several learning processes of the organizational team and school community there is less evidence regarding the staff of the school-administration office. It was not possible to precisely determine if and why learning did not take place, but we found one explanation: An interviewee pointeds to the immense workload of the administrative staff. “She manages 168 schools and therefore – just due to bare efficiency purposes – she is not able to deal with one school so intensively.” [LS1] This indicates that the interventions of the UE such as joint project planning did interrupt administrative habits but may not have led to an inquiry due to a lack of personnel capacities. This refers not only to potential cognitive learning, but also to the other learning dimensions. We find that habits of the school-administration office did not change but were mainly consolidated [LS1, LS2].

Normative learning

In the following we describe a joint learning process of the school community and the organizational team. The main aspiration of the team was to establish participatory and ecological principles for redesigning the schoolyard. The school mainly participated in the project to improve the school grounds and the school’s reputation. The team intervened in the everyday school life by implementing participatory approaches such as asking the students about their hopes regarding the design of the schoolyard. Several teachers responded with skepticism and described a problematic situation:

What if they wish for a treehouse? In the end, we have to supervise the children and oversee the schoolyard.…But then we realized it is good if we discuss several ideas and don’t decide everything on our own. [LS4]

And especially during the construction week, I experienced that the children did not choose [those construction and planting activities] which I found most interesting. Insofar, it was good to identify their needs beforehand. [LS4]

We observed similar learning processes among members of the school community and the organizational team regarding the introduction of environmental education approaches to the school. Normative learning becomes apparent when contrasting the initial motivation of the school actors, namely, to improve the condition and reputation of the school, with the statements made after the week of collective building and planting. As one of the project initiators described:

Certain aspects of our project were initially of secondary importance for the school: The environmental education, to understand the school ground as a living space, also the opening of the school to the neighborhood and the district. [LS1]

Relational learning

Intense relational learning took place between the students and their teachers. This quote by an educator nicely illustrates a relational learning experience:

Kids, who are usually very unfocused, were totally engaged [in the construction week] and wanted to finish their project. I was amazed and saw some of the children from a different perspective. [LS9]

In contrast, several interviewees were dissatisfied about collaboration with the organizational team, school community, and school administration as different logics of action clashed: bottom-up, participatory versus top-down, hierarchical. We will reconstruct the processes from the perspective of the organizational team. By intervening in the routines of school community and school administration they sought to establish a collaborative style based on the principles of co-creation and transparent communication. They discovered a problematic situation insofar as their approach of collaboration conflicted with the top-down and hierarchical style of decision-making by the school-administration office. The organizational team scheduled several meetings to find common ground and a way of constructive collaboration. Thereby, they learned a lot about how to communicate with the administration. However, we could not find evidence for collective learning by the members of the organizational team, the school community, or the two involved offices of the public administration. Instead, actors of all three parties reported a lingering gap since they hoped to achieve some relational learning in the sense that the other parties should better recognize their interests and working logics. An example is given by one of the organizers.

We tried to initiate several discussions and receive a decision [about additional funding sources] from the administrative office. However, we were told that they function according to their own time schedule and in their own way. Frustrating. [LS1]

This quote illustrates how disempowered the organizational team felt due to the nontransparent processes. The problematic situation of establishing a collaborative working style could not be resolved. Also, power inequalities became apparent. Notably, the representatives of the school administration could ignore the wishes raised by the organizational team (non-privileging) and continue with their usual workflow, whereas the team depended on its collaboration. Here, the representatives of the school administration did not join an inquiry but consolidated prevalent habits.

Socio-material learning

First, the participation process to generate ideas on redesigning the schoolyard and, second, the construction week interrupted everyday habits of the school. Both activities opened a space for creativity and empowerment insofar as the participants were invited to co-design the schoolyard, changing their roles from passive users to active co-creators. The inquiry of this learning experience goes beyond encountering novel information followed by an actualization of beliefs (as described above for the instance regarding the insect hotels). It was an experimental process of taking part in the construction week and adopting a novel role. The participants attached new meanings to the materials with which they worked. During the construction week, new identities were formed regarding the socio-material environment (that differ from the previous perception of the schoolyard as an area made available by the school administration).

A part of the schoolyard wasn’t directly accessible – it had to be approved by the respective authority and the pupils asked their teachers: When can we go to our site? That was now their site, which they had helped to build. [LS1]

This demonstrates how the students started to identify with their schoolyard, a process that indicates socio-material learning. Various interviewees expected them to treat the built items with particular care [LS1, 2, 3, 6]. However, due to the limited observation period, we could not confirm whether these expectations materialized.

District funds and councils for active and sustainable neighborhoods (DF)

To the main actor groups of DF belonged the organizational team initiating the UE, members of the district council, and the project applicants. DF is not anchored within an institution but relied on voluntary participation of residents as members of the councils or project applicants. The main interventions were the provision of funding for residents to co-create their urban districts, district-council meetings to decide on funding, and implementation of projects by the residents.

Cognitive learning

An established principle for the district council was to fund projects that are accessible to as many residents of the district as possible [DF2, 4]. Therefore, a council member faced a problematic situation during a district-committee meeting as a project applicant suggested to fund a swimming course for Muslim women only. An interviewee described the situation.

They [the council members] find common ground through their respective areas of expertise. Someone asks a critical question: “Why is the sports course only for Muslim women?” And then Person B responds: “I always work with the women and that’s important; they need that.” Then the council members simply trust the expertise of each other. And since every council member simultaneously represents a group, it works well. [DF6]

The district-council member queried why the course is only for Muslim women. Another district-council member offered a solution for the inquiry by pointing to the need for privacy. The first district-council member accepted this solution because she trusted the expertise of the other one. Thereby cognitive and normative learning took place because the district council acquired novel knowledge and values (swimming courses by Muslim women require a safe space). The inquiry was enabled by a nonhierarchical atmosphere in the council and the inclusion of persons with different perspectives and expertise in decisionmaking. Several other district councils reported similar cognitive learning processes such as encountering novel arguments for why a shift toward ecological habits is important [DF2]. These cognitive learning experiences of individuals led to the emergence of collective voting habits in the council.

Normative learning

A crucial normative learning process refers to an increased feeling of self-efficacy through local action. A project applicant described her previous feeling of being overwhelmed by the global climate crisis.

I had really reached a frustration level in my life, where I thought that all of this is useless; it’s useless to shred a stupid plastic bottle somewhere here in a Johannstadt when the ocean is full. [DF6]

She continued to describe how interviewing a person who recycles plastic bottles and makes lamps out of them inspired her. We interpret this as a gap between renewed inspiration and her previous frustration due to being overwhelmed by the global crisis. The interview led to an inquiry and, subsequently to a change in norms.

And this conversation alone has just caused that I now look differently at those materials. And now I think it is better when the bottle is shredded. So, I actually became more optimistic and started to believe that these little steps also help achieve sustainability. [DF6]

The second part of the quote illustrates the process of privileging leading to normative learning. The quote also indicates socio-material learning as the interviewee reported that her perception of the bottles changed. She did not privilege the problems of plastic bottles polluting the oceans anymore but instead the inspiring idea of recycling plastic bottles locally. We found similar learning processes concerning the appreciation of democratic processes. A coordinator summarized a respective normative learning process.

[People] recognize opportunities to become actively involved in a pluralistic society, in a democracy. People who otherwise would not have done so; who, if the hurdles are higher, would not have written an application without any advice and support. And in the end, when they have succeeded, it is an incredibly positive experience of self-efficacy. [DF4]

As participation in DF was voluntary, most participants were already ecologically minded and active in local sustainability initiatives [DF1, 2, 3, 6, 7]. This narrowed the scope for normative learning due to the intervention. Encountering the principle of DF to foster sustainability did not lead to problematic situations but aligned with their own values. Therefore, the formation of novel participatory habits through DF was not a transformation but more an enrichment of already existing habits of co-creation for most participants. However, as illustrated in the example above, participation in the UE was a source of inspiration for some interviewees [DF4, 6].

Relational learning

The district council in Johannstadt developed a common perspective on various issues such as sustainable project implementation through moderated discussions. For example, a shared aspiration arose to foster local consumption and sharing. Applicants should use objects already available in the district (if possible), and place newly bought objects at public locations for sharing purposes [DF1, 7, 9]. We will further illustrate a collective experience in Pieschen that is particularly insightful regarding restraining factors for learning. During a district-council meeting a project application was discussed. A controversial debate ignited on whether remunerations for the working hours of project applicants should be funded. This debate represents a problematic situation since the councils hold diverging views on remuneration and were not confident on how to decide. While some opposed remuneration, arguing that voluntary engagement should not be rewarded through financial means (administrative perspective), others supported remuneration, arguing that it is important to show appreciation for voluntary engagement (cultural/arts perspective). The debate provoked an inquiry, however, the councils could not find a common position and decided to postpone a decision. One district-council member expressed her frustration that this collective inquiry was stalled.

I once identified this dilemma [regarding the consequences of being in-transparent about remunerations] quite openly and suggested that we somehow make a proposal on how to clarify it. And it was also stated that we wanted to do this. But then it didn’t happen. And I thought that was a great pity. [DF5]

The interviewee stated that there was a consensus to further discuss the question of remuneration indicating that also others defined this situation as problematic, but a collective inquiry did not proceed. She related this to missing facilitation by the organizational team that should have organized a discussion to resolve the problematic situation. She assumed that the organizational team was simply overwhelmed by the challenge of facilitation as they had no prior experience with this activity. Moreover, there were power imbalances within the council. District-council members with more expertise in administrative law and funding procedures dominated the debate. Here again facilitation and moderation would have been crucial to not sideline less experienced participants. In contrast, the organizational team of Johannstadt had previous experiences with a neighborhood council and could guide inquiries through facilitation [DF1, 13].

Furthermore, many simultaneous relational learning processes strengthened ties between applicants, councils, and residents and led to establishment of an active district community [DF1, 2, 3, 5, 7, 8]. This is evident in several interview passages such as the following.

[The local cafe owner and her business] were not so much on my radar in the past. But now it is because she is in the council, and I know how engaged she is. And I did recommend people to go there. [DF8]

The quote nicely illustrates the privileging process and novel habit of recommending the cafe to colleagues.

Socio-material learning

The relational learning processes were closely linked to socio-material learning and nearly all interviewees reported that participation in the UE changed their associations with the district [DF1, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 11, 12]. A respondant described a socio-material learning process caused by the possibility of adopting a novel role.

So, these [political activities] were all abstract variables for me until I started my work [creating a district magazine] here, and I think that this opportunity is great to get involved in this kind of political participation, where nothing is too small. So, if someone says I would like to have 10 bulbs there that can just help to influence, that he then just no longer cycle past the city district office and think these morons there, but thinks there are my bulbs. [DF6]

While residents previously had a more passive relationship to the district, they were invited to become active and explored possibilities to co-create it. This was a problematic situation since it did not align with their previous role of a more passive resident. As part of an inquiry, they got to know the district better and novel associations to specific places were formed. Participants developed more personal connections to shops, institutions, or squares within the district and often reported that they began to associate specific activities funded by the DF with those places. An example is a bee-keeping project located at the church which an interviewee remembered every time passing by [DF5]. Here, the inquiry included a sequence of experiences – potentially also involving gradual developments of novel associations. While nearly all interviewees reported some novel relations to the district, not all of them experienced a change in their role. For instance, a large share of participants, in particular in Johannstadt, were already very engaged in co-designing the district [DF2, 5, 6, 7, 9, 10, 11]. The participation in DF was therefore as elaborated above more an enrichment of existing habits of co-creation.

Discussion

Learning processes in the two urban experiments

Without attempting a systematic comparison, this subsection discusses striking commonalities and differences in the learning dynamics of the two UEs. Both experiments stimulated varying learning processes of individuals and communities. We identified a variety of encounters that interrupted prevalent habits and stimulated learning. Based on those circumstances, we could observe individual as well as collective inquiries in both UEs. An example for the former is the cognitive learning process regarding the flight directions of insects. The latter was illustrated by the collective process of developing a participatory approach that balanced supervision requirements with the inclusion of the students’ voices. The interventions of both UEs led to the empowerment of actors and changes in roles. Students and teachers, as well as residents, changed from being rather passive users to active co-designers during the experimentation. We interpret these collective experiences as joint inquires that strengthened relations within the school community and the district community, led to novel identities, and engendered novel associations and meanings attached to places. Simultaneously, learning processes supported participation of local actors as the interventions of both UEs created novel possibilities for co-creation and increased the appreciation for participatory processes. Thereby, relational and socio-material learning processes were highly entangled, which is illustrated by expressions from the students like “when can we go to our site?” [LS1]. Collective activities of building and planting in the school and of planning and implementing in the district simultaneously changed the relationships between the actors as well as their relationships to places. The quote illustrates this by creating a link between the collective social construction (our) and the schoolyard (site).

Furthermore, we presented evidence about how learning processes contributed to the reconfiguration of habits. However, several of our examples refer to rather small alterations or enrichments of habits then to real transformations. The relational learning process of a council member, for instance, who got to know the residents and their activities better and therefore now recommends a local café to colleagues, seems to be a very tiny novel habit that rather enriches other habits of talking to colleagues. Hopes of the initiators of the UE were that the participants would integrate several local habits in their everyday life, buying locally being only one of them. This could have been a more pertinent transformation of routines. Certainly, this is also a methodological problem since several of the learning processes we observed took place at the end of the UEs and we could not observe further developments such as whether the school continued the series of environmental education units.

Besides commonalities in learning processes, we want to point to important differences. The set-up of both UEs – LS anchored within a school community and compulsory in nature versus DF being open and voluntary in nature – crucially affected learning potentials. Since the actors in DF were mostly ecologically minded, the participatory and ecological criteria for funding local projects aligned with their mindset and did not cause problematic situations. Similarly, several participants of DF were already actively engaged in the district, which was continued during the UE. Therefore, habits were enriched but mostly not transformed. In contrast, anchoring LS within the school community proved as valuable to include actors – who were still skeptical toward the ideas of sustainability and participation – so that normative learning could occur. Further, the interventions of LS did directly address and partially interrupt the everyday habits and institutional processes of the school, while DF was more an additional engagement that intervened less in existing working or leisure habits of most participants.

However, balancing between the institutional logics and routines of the school and the approach of the organizational team was often a disempowering experience for the participants from the organizational team, school community, and public administration. The evidence demonstrates how a lack of capacities did not allow the administrative staff to join an inquiry. Similarly, the school community was overwhelmed by the additional project work. Having sufficient personnel capacities would be a basic condition to equally participate (in learning-related inquiries). Additionally, the involved parties need to be willing to take part in collective inquiries with the aim of uniting sustainability with their institutional habits. So, on one hand, LS induced learning between the school community and the organizational team that resulted in forming new participatory and ecological habits of co-creating the schoolyard, which replaced old habits. On the other hand, we demonstrated how problematic situations between the school community, organizational team, and school-administration office could not be resolved, so that neither learning took place nor habits were changed.

Understanding learning in urban experiments

In recent years, scholars have criticized ST literature as being rather vague on the learning processes and outcomes that can be expected from UEs (van Mierlo et al. Citation2020; Van Poeck, Östman, and Block 2020). To remedy this deficit, we adopted a transactional understanding of learning. We differentiated four types of processes that can emerge from learning in UEs, namely cognitive, normative, relational, and socio-material learning. This article elucidates conceptually and empirically how UEs can induce learning processes. Further analysis is still needed to determine how far those learning processes have the potential to contribute to STs. A common first step in approaching this issue in the sustainability transition literature is to classify learning as superficial (lower order) or deep (higher order) (Argyris and Schön Citation1978; van Mierlo and Beers Citation2020). While this idea of dividing learning processes into more basic and more impactful for STs is highly appealing, this categorization has been criticized as weakly substantiated in theory and practice (van Mierlo and Beers Citation2020, 13). We have addressed this issue following the distinction in transactional learning theory of slight adaptations in habits and learning resulting from reflexive processes, including inquiries that potentially transform habits. On one hand, future research needs to develop an understanding of how learning processes accumulate and can initiate changes of broader societal dynamics beyond the micro- and meso-levels (Van Poeck, Östman, and Block 2020). On the other hand, slight adaptation in habits instead of learning show that the potential of UEs to transform society should not be overrated (Torrens et al. Citation2019).

While we adopt a transactional pragmatist perspective and differentiate four types of learning, our empirical results additionally point to the importance of power and materiality for learning processes. We therefore argue for extending the learning concepts in STs. This can counteract the criticized blurriness in current analyses of learning in STs, and, as asserted in the following, provide entry points to conceptualize the impact of learning processes on broader processes of societal change. In our case study, power inequalities became apparent at the meso-level. Actors from the public administration exercised power over the members of the organizational team as they ignored their need for transparency and collaboration. Transactional theory mentions power as one of the interpersonal aspects that are part of transactions and thereby also potentially relevant for learning (Van Poeck, Östman, and Block 2020). While we investigated these power struggles at the meso-level, further conceptualizing the relationship between learning and power (a)symmetries might shed light on how experimentation might reshape broader power relations.

This observation links the debate on learning to the discourse on power in ST studies (Avelino Citation2017; Avelino and Wittmayer Citation2016). Gaining conceptual and empirical insights on collective learning and power is a starting point to eliminate current blind spots regarding the relation of individual and social learning (Reed et al. Citation2010, Van Poeck, Östman, and Block 2020). Transactional learning theory possesses explanatory power for analyzing learning processes of and between different actors involved in UE, as demonstrated in this article. Yet, it sometimes lacks a precise vocabulary to distinguish between different processes of social learning. Such terminology could highlight the differences between consensual learning in the sense of having a joint understanding of problematic situations and agreeing on a solution in contrast to more conflictual learning. Examples for the former are learning processes within the team that initiated LS while the latter is exemplified by the learning processes between the initiators of LS and the representatives of the public administration.

This article further contributes to conceptual sharpening by shedding light on the hitherto neglected role of materiality and socio-material relations in learning processes (Hofverberg and Maivorsdotter Citation2018; Van Poeck, Östman, and Block 2020, 9). Our findings of how novel socio-material associations led to changes in habits confirm a thesis advanced by practice theorists. They argue that practices are stabilized by linkages between meanings, competencies, and materials (Öztekin and Gaziulusoy Citation2019; Shove and Walker Citation2010), which implies that the formation of novel connections between these three elements might initiate changes in practices. This can be confirmed, for instance, by our findings that the students developed novel associations to the schoolyard through collective manual activities during the construction week. They began to identify with the schoolyard, calling it “their” site and were eager to try out the newly built devices (novel habits). Particularly meanings related to self-efficacy and a sense of community became associated with the newly installed elements at the schoolyard (materials), which represent novel linkages. In the same way, new craft skills (competencies) were associated with the school grounds (materials). Materials and their linkages to meanings and competencies are usually connected with various habits and (at least according to practice theory) affect habits over time (Shove and Walker Citation2010). Therefore, investigating how these linkages are formed and resolved can be a first step of approaching the so far black-boxed effects of learning on macro-level societal change. While we focused on socio-material learning, future research could also explore the effects of socio-material configurations on interventions. One could, for example, ask if some spaces are more fruitful locations for UEs. This requires a more detailed conceptualization of the aspects that constitute socio-material and socio-spatial configurations (Levin-Keitel et al. Citation2018).

Conclusion

We aimed in this article to deepen the understanding of learning through urban experimentation. We address the research questions on how and which processes of social learning are initiated by UEs. We introduced a transactional understanding to conceptualize how learning can emerge and distinguished between cognitive, normative, relational, and socio-material learning. A case study of two UEs demonstrates how interventions disturb the everyday life of actors and potentially induce inquiries. In those inquiries actors experiment with solutions for overcoming the disturbance and thereby acquire novel knowledge and values or built new relations to persons or materials. In both cases we identified several dialogues and socio-material encounters that disturbed habits and initiated reflections and learnings. We thereby found a striking difference between the two UEs: Anchoring a UE in an institution, which does not have a focus on sustainability yet, is challenging but at the same time enables to induce important (normative) learning processes. This should be mirrored in funding policies, for instance by incentivizing approaches of UE that address stakeholder groups without socio-ecological attitudes and develop strategies to involve them in learning processes. This latecomer approach, aiming at broad participation, stands in contrast to the frontrunner approach suggested by transition management that posits the central role of sustainability pioneers (Loorbach Citation2010). Approaches including a more diverse group should (1) ensure that those stakeholders have personnel capacities to take part in learning processes and (2) be sensitive for power inequalities that might require strategies to convince actors to participate in learning. We further elucidate conceptually as well as empirically how materiality matters for learning processes: While socio-material relations were part of encounters and inquires, they were also changed through learning, for instance by identity-building. We thus call for the consideration of socio-material relations in the debate on learning in STs.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Marc Wolfram, Katrien van Poeck, and Martina Artmann for valuable insights on former versions of the article. We are also grateful to two anonymous reviewers for their attentive reading and helpful comments and particularly thank the UE teams for their commitment and inspiration.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 All quotations were translated by the authors. The numbers in the brackets identify the various interviewees (see Appendix 1). To protect the anonymity of our interviewees we do not specify their gender and refer to all of them by using female pronounce.

2 We speak of a collective inquiry because several school actors as well as the organizational team participated in the inquiry.

References

- Ardoin, N., and J. Heimlich. 2021. “Environmental Learning in Everyday Life: Foundations of Meaning and a Context for Change.” Environmental Education Research 27 (12): 1–16. doi:10.1080/13504622.2021.1992354.

- Argyris, C., and D. Schön. Eds. 1978. Organizational Learning: A Theory of Action Perspective. Boston, MA: Addison-Wesley.

- Avelino, F. 2017. “Power in Sustainability Transitions: Analysing Power and (Dis)Empowerment in Transformative Change towards Sustainability: Power in Sustainability Transitions.” Environmental Policy and Governance 27 (6): 505–520. doi:10.1002/eet.1777.

- Avelino, F., and J. Wittmayer. 2016. “Shifting Power Relations in Sustainability Transitions: A Multi-Actor Perspective.” Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning 18 (5): 628–649. doi:10.1080/1523908X.2015.1112259.

- Beers, P., F. Hermans, T. Veldkamp, and J. Hinssen. 2014. “Social Learning Inside and Outside Transition Projects: Playing Free Jazz for a Heavy Metal Audience.” Wageningen Journal of Life Sciences 69 (1): 5–13. doi:10.1016/j.njas.2013.10.001.

- Beers, P., J. Turner, K. Rijswijk, T. Williams, T. Barnard, and S. Beechener. 2019. “Learning or Evaluating? Towards a Negotiation-of-Meaning Approach to Learning in Transition Governance.” Technological Forecasting and Social Change 145: 229–239. doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2018.09.016.

- Castán Broto, V., and H. Bulkeley. 2013. “A Survey of Urban Climate Change Experiments in 100 Cities.” Global Environmental Change 23 (1): 92–102. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2012.07.005.

- Chabay, I., L. Koch, G. Martinez, and G. Scholz. 2019. “Influence of Narratives of Vision and Identity on Collective Behavior Change.” Sustainability 11 (20): 5680. doi:10.3390/su11205680.

- Cundill, G., H. Lotz-Sisitka, M. Mukute, M. Belay, S. Shackleton, and I. Kulundu. 2014. “A Reflection on the Use of Case Studies as a Methodology for Social Learning Research in Sub-Saharan Africa.” Wageningen Journal of Life Sciences 69 (1): 39–47. doi:10.1016/j.njas.2013.04.001.

- Dewey, J., Ed. 1934. Art as Experience. New York: Perigee Books.

- Dewey, J., Ed 1938. Experience and Education. New York: Free Press.

- Didham, R., P. Ofei-Manu, and M. Nagareo. 2017. “Social Learning as a Key Factor in Sustainability Transitions: The Case of Okayama City.” International Review of Education 63 (6): 829–846. doi:10.1007/s11159-017-9682-x.

- Evans, J., F. Berkhout, A. Karvonen, and R. Raven. 2016. “The Experimental City: New Modes and Prospects of Urban Transformation.” In The Experimental City, edited by J. Evans, A. Karvonen, and R. Raven, 1–12. London: Routledge.

- Frantzeskaki, N., F. van Steenbergen, and R. Stedman. 2018. “Sense of Place and Experimentation in Urban Sustainability Transitions: The Resilience Lab in Carnisse, Rotterdam, The Netherlands.” Sustainability Science 13 (4): 1045–1059. doi:10.1007/s11625-018-0562-5.

- Geertz, C., Ed. 1973. The Interpretation of Culture. New York: Basic Books.

- Gould, R., N. Ardoin, J. Thomsen, and N. Wyman Roth. 2019. “Exploring Connections between Environmental Learning and Behavior through Four Everyday-Life Case Studies.” Environmental Education Research 25 (3): 314–340. doi:10.1080/13504622.2018.1510903.

- Grunwald, A. 2004. “Strategic Knowledge for Sustainable Development: The Need for Reflexivity and Learning at the Interface between Science and Society.” International Journal of Foresight and Innovation Policy 1 (1–2): 150–167. doi:10.1504/IJFIP.2004.004619.

- Herrero, P., T. Dedeurwaerdere, and A. Osinski. 2019. “Design Features for Social Learning in Transformative Transdisciplinary Research.” Sustainability Science 14 (3): 751–769. doi:10.1007/s11625-018-0641-7.

- Hofverberg, H., and N. Maivorsdotter. 2018. “Recycling, Crafting and Learning – An Empirical Analysis of How Students Learn with Garments and Textile Refuse in a School Remake Project.” Environmental Education Research 24 (6): 775–790. doi:10.1080/13504622.2017.1338672.

- Karvonen, A., and B. van Heur. 2014. “Urban Laboratories: Experiments in Reworking Cities: Introduction.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 38 (2): 379–392. doi:10.1111/1468-2427.12075.

- Kivimaa, P., W. Boon, S. Hyysalo, and L. Klerkx. 2017. “Towards a Typology of Intermediaries in Transitions: A Systematic Review.” SSRN Electronic Journal 17: 3034188. doi:10.2139/ssrn.3034188.

- Levin-Keitel, M., T. Mölders, F. Othengrafen, and J. Ibendorf. 2018. “Sustainability Transitions and the Spatial Interface: Developing Conceptual Perspectives.” Sustainability 10 (6): 1880. doi:10.3390/su10061880.

- Loorbach, D. 2010. “Transition Management for Sustainable Development: A Prescriptive, Complexity-Based Governance Framework.” Governance 23 (1): 161–183. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0491.2009.01471.x.

- Luederitz, C., N. Schäpke, A. Wiek, D. Lang, M. Bergmann, J. Bos, S. Burch, et al. 2017. “Learning through Evaluation – A Tentative Evaluative Scheme for Sustainability Transition Experiments.” Journal of Cleaner Production 169: 61–76. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.09.005.

- Matschoss, K., F. Fahy, H. Rau, J. Backhaus, G. Goggins, E. Grealis, E. Heiskanen, et al. 2021. “Challenging Practices: Experiences from Community and Individual Living Lab Approaches.” Sustainability: Science, Practice and Policy 17 (1): 135–151. doi:10.1080/15487733.2021.1902062.

- Mayring, P. 1994. “Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse [Qualitative Content Analysis].” In Texte verstehen: Konzepte, Methoden, Werkzeuge [Understanding Texts: Concepts, Methods, Tools], edited by A. Boehm, A. Mengel and T. Muhr, 159–175. Konstanz: UVK Univ.-Verl. Konstanz.

- McFadgen, B., and D. Huitema. 2017. “Are All Experiments Created Equal? A Framework for Analysis of the Learning Potential of Policy Experiments in Environmental Governance.” Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 60 (10): 1765–1784. doi:10.1080/09640568.2016.1256808.

- Mogalle, M. Ed. 2001. Management transdisziplinärer Forschungsprozesse [Management of Transdisciplinary Research Processes]. Basel: Birkhäusel.

- Östman, L. 2010. “Education for Sustainable Development and Normativity: A Transactional Analysis of Moral Meaning-Making and Companion Meanings in Classroom Communication.” Environmental Education Research 16 (1): 75–93. doi:10.1080/13504620903504057.

- Öztekin, E., and A. Gaziulusoy. 2019. “Designing Transitions Bottom-up: The Agency of Design in Formation and Proliferation of Niche Practices.” The Design Journal 22 (S1): 1659–1674. doi:10.1080/14606925.2019.1594999.

- Pohlmann, A. 2020. “Praxistheorie: Ansätze sozialer Praktiken am Beispiel der Nachhaltigkeit akademischen Lernens und Lehrens [Practice Theory: Approaches of Social Practices Using the Example of Sustainability in Academic Learning and Teaching].” In 10 Minuten Soziologie: Nachhaltigkeit [10 Minutes Sociology: Sustainability], edited by T. Barth and A. Henkel, 167–180. Bielefeld: Transcript-Verlag.

- Reed, M., A. Evely, G. Cundill, I. Fazey, J. Glass, A. Laing, J. Newig, et al. 2010. “What is Social Learning?” Ecology and Society 15 (4): 1. doi:10.5751/ES-03564-1504r01.

- Schneidewind, U., and M. Singer-Brodowski. 2015. “Vom experimentellen Lernen zum transformativen Experimentieren: Reallabore als Katalysator für eine lernende Gesellschaft auf dem Weg zu einer Nachhaltigen Entwicklung [From Experimental Learning to Transformative Experimenting: Real-Living-Fabs as Catalyst for a Learning Society toward a Sustainable Development.” Zeitschrift für Wirtschafts-und Unternehmensethik 16 (1): 10–23. ].” doi:10.5771/1439-880X-2015-1-10.

- Sengers, F., A. Wieczorek, and R. Raven. 2019. “Experimenting for Sustainability Transitions: A Systematic Literature Review.” Technological Forecasting and Social Change 145: 153–164. doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2016.08.031.

- Shove, E., and G. Walker. 2010. “Governing Transitions in the Sustainability of Everyday Life.” Research Policy 39 (4): 471–476. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2010.01.019.

- Torrens, J., J. Schot, R. Raven, and P. Johnstone. 2019. “Seedbeds, Harbours, and Battlegrounds: On the Origins of Favourable Environments for Urban Experimentation with Sustainability.” Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions 31: 211–232. doi:10.1016/j.eist.2018.11.003.

- van Mierlo, B., and P. Beers. 2020. “Understanding and Governing Learning in Sustainability Transitions: A Review.” Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions 34: 255–269. doi:10.1016/j.eist.2018.08.002.

- van Mierlo, B., J. Halbe, P. Beers, G. Scholz, and J. Vinke-de Kruijf. 2020. “Learning about Learning in Sustainability Transitions.” Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions 34: 251–254. doi:10.1016/j.eist.2019.11.00q.

- Van Poeck, K., and L. Östman. 2021. “Learning to Find a Way Out of Non-Sustainable Systems.” Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions 39: 155–172. doi:10.1016/j.eist.2021.04.001.

- Van Poeck, K., L. Östman, and T. Block. 2020. “Opening Up the Black Box of Learning-by-Doing in Sustainability Transitions.” Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions 34: 298–310. doi:10.1016/j.eist.2018.12.006.

- Walter, A., S. Helgenberger, A. Wiek, and R. Scholz. 2007. “Measuring Societal Effects of Transdisciplinary Research Projects: Design and Application of an Evaluation Method.” Evaluation and Program Planning 30 (4): 325–338. doi:10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2007.08.002.

- Weiland, S., A. Bleicher, C. Polzin, F. Rauschmayer, and J. Rode. 2017. “The Nature of Experiments for Sustainability Transformations: A Search for Common Ground.” Journal of Cleaner Production 169: 30–38. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.06.182.

- Wiek, A., B. Kay, and N. Forrest. 2017. “Worth the Trouble?! An Evaluative Scheme for Urban Sustainability Transition Labs (USTLs) and an Application to the USTL in Phoenix, Arizona.” In Urban Sustainability Transitions, edited by N. Frantzeskaki, V. Castán Broto, L. Coenen, and D. Loorbach, 227–256. London: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781315228389.

- Wildemeersch, D., and J. Vandenabeele. 2007. “Relocating Social Learning as a Democratic Practice.” In Democratic Practices as Learning Opportunities, edited by R. van der Veen, D. Wildemeersch, J. Youngblood, and V. Marsick, 19–32. Leiden: Brill. doi:10.1163/9789087903398_004.

- Yin, R. 2008. “How to Do Better Case Studies (with Illustrations from 20 Exemplary Case Studies).” In The Sage Handbook of Applied Social Research Methods, edited by L Bickmann and D. Rog, 229–260. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.