Abstract

Energy efficiency and renewable energy strategies have been insufficient in achieving rapid and profound reductions of energy-related greenhouse-gas (GHG) emissions. Consequently, energy sufficiency has gained attention as a complementary strategy over the past two decades. Yet, most research on energy sufficiency has been theoretical and its implementation in policy limited. This study draws on the growing sufficiency literature to examine the presence of sufficiency as a strategy for reducing energy-related GHG emissions in Sweden, a country often regarded as a “climate-progressive” country. By conducting a keyword and content analysis of energy policies and parliamentary debates during four governmental terms of office (2006–2022), this research explores the extent to which sufficiency is integrated into Swedish energy policy, as well as potential barriers to its adoption. The analyses revealed a scarcity of sufficiency elements. Although some policies could potentially result in energy savings, they are infrequent and overshadowed by the prevailing emphasis on efficiency and renewable energy. Furthermore, Sweden lacks a target for sufficiency or absolute energy reductions. The main impediments to sufficiency implementation include the disregard of scientific evidence in the policy-making process and the perceived contradiction between sufficiency and industrial competitiveness. This study thus concludes that sufficiency at best remains at the periphery of Swedish energy policy. Given the reinforced ambitions within the European Union, this raises questions regarding the validity of Sweden’s reputation as a climate-progressive country.

Introduction

Reducing production and consumption plays a crucial role in addressing today’s interrelated environmental crises and realizing the targets outlined in the Paris Agreement (IPBES Citation2019; IPCC Citation2022). In the energy-policy domain, the two dominating approaches to reduce energy-related greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions have been improving energy efficiency and increasing renewable energy deployment. However, these strategies have been insufficient in achieving significant reductions due to rebound effects and resource limitations (IPBES Citation2019; Sorrell Citation2018; Wiedmann et al. Citation2015). There is therefore strong scientific support for supplementing these strategies with energy-sufficiency policies (henceforth “sufficiency policies”) (IPCC Citation2022; Lorek and Fuchs Citation2013; O’Neill et al. Citation2018).

The concept of energy sufficiency (henceforth “sufficiency”) provides a framework for understanding the meaning of enough (Darby Citation2007). It encompasses both minimum social thresholds (meeting basic human needs and promoting well-being based on principles of fairness) and upper limits (limiting or reducing energy use to remain within planetary boundaries) (Burke Citation2020; Princen, 2005). While acknowledging the necessity to consider both aspects of minimum social thresholds and upper environmental limits, this article focuses on the latter as a policy strategy to achieve climate targets (Di Gulio and Fuchs Citation2014). Although the notions of limits (Meadows et al. Citation1972) and reducing consumption for social and environmental reasons (Daly Citation1977) are not novel, they have re-emerged in science in response to the cascading impacts of climate change (Jungell-Michelsson and Heikkurinen Citation2022). Despite the growing number of science-based appeals for sufficiency policies over the past two decades, few recommendations have been implemented in policymaking (Brockway et al. Citation2021; Zell-Ziegler et al. Citation2021). However, it is possible to detect a slight shift toward the dissemination of sufficiency policies at the local level (Callmer and Bradley Citation2021), and a growing recognition of the importance of sufficiency in national and international policy discussions (Hotta et al. Citation2021; Zell-Ziegler et al. Citation2021).

Against this background, the objective of this article is to examine the extent to which sufficiency has been integrated in policymaking in a climate-progressive country. Sweden has been selected as the focus of study, with specific attention devoted to the area of energy policy. This research seeks to answer the following questions:

Is sufficiency, or similar concepts, mentioned or referred to in Swedish energy policy?

Does Sweden have an energy target for sufficiency and, if so, what does it imply?

Can any policies that aim to promote sufficiency be identified?

What are the main barriers to the implementation of sufficiency policies?

By answering these questions, we seek to enhance the understanding of sufficiency in policymaking and to identify concrete obstacles inhibiting the adoption and implementation of sufficiency policies. In doing so, this research contributes to the existing sufficiency literature by providing empirical evidence to supplement the primarily theoretical research conducted thus far and in line with calls from scholars (Bertoldi Citation2022; Zell-Ziegler et al. Citation2021).

Sweden presents an interesting case to investigate the extent of sufficiency policies. In addition to being recognized by researchers as a climate-progressive country (Karlsson Citation2021; Sarasini Citation2009), the nation began addressing the need to save energy for social and environmental reasons as early as the 1970s (SEGOV Citation1975). Sweden also aims to become the “world’s first fossil-free welfare state” (SEGOV Citation2016/2017a) and has reduced territorial GHG emissions by one third since 1990, although this volume is not consistent with the climate-mitigation targets adopted by the Parliament (SEPA Citation2022), indicating the need for more ambitious policies. This context should provide a good opportunity for sufficiency policies to emerge in policymaking. While sufficiency spans across policy fields, energy lies at the heart of the discussion. In particular, energy is an essential aspect of all production and consumption and thus, we will focus on the existence of sufficiency policies in energy as well as climate policy, as these two fields are inseparably linked.

The next section defines and elaborates on the concepts and theories that we use, followed by a section on materials and methods. Subsequently, the empirical results are presented, followed by a discussion of the implications for policymaking and future research that can be of value within and beyond the field of sufficiency.

Theory and context

Efficiency, renewable energy, and sufficiency are three complementary strategies to reduce energy-related GHG emissions (Santarius, Walnum, and Aall Citation2016). The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) defines the latter of these approaches as addressing the “causes of the environmental impacts of human activities by avoiding the demand for energy and materials” (IPCC Citation2022, 957). In contrast, efficiency strategies seek to reduce environmental impacts by improving the input-output ratio—for example by decreasing the energy input per produced or emitted unit of output—through technological innovations, while renewable energy strategies incentivize a shift of the energy base away from fossil fuels (Samadi et al. Citation2017). However, the boundary between sufficiency and efficiency is not always clear cut. To differentiate the two, one could say that efficiency measures aim to reduce environmental impacts by delivering the same energy service with less input or delivering more with equal input while sufficiency reduces environmental impacts by decreasing the level of the energy service. Thus, sufficiency provides a valuable complement to conventional technology-focused energy strategies (Vadovics and Živčič Citation2019). Notwithstanding the importance of efficiency and renewable energy strategies, they alone have limited capacity to rapidly mitigate climate change (Burke Citation2020). Efficiency measures often suffer from rebound effects that offset potential energy savings (Figge, Young, and Barkemeyer Citation2014; Santarius, Walnum, and Aall Citation2016) and renewable energy is constrained by the diffusion rate and resource limitations of such techniques (IPBES Citation2019). In other words, sufficiency offers an important perspective, visualizing the total environmental impact of all technologies and the constraints of technological shifts. However, sufficiency should not be seen as contradictory to efficiency and renewable energy, but the three agendas need to work in parallel (Spangenberg and Lorek Citation2019).

Sufficiency

There is no universally accepted definition of sufficiency. Some scholars consider it to be a goal (Darby and Fawcett Citation2018) or specific level at which basic needs are met (Millward-Hopkins et al. Citation2020), while others see it as a transformative strategy or a set of actions to reduce energy use (Brischke et al. Citation2015). An increasing body of research suggests that an overall transformation toward sufficiency could expedite the reduction of GHG emissions while maintaining or even improving well-being (see e.g., Grubler et al. Citation2018; Rao and Min Citation2018).

Given the overlapping boundary between sufficiency and efficiency, it is difficult to categorize sufficiency policies unambiguously (Zell-Ziegler et al. Citation2021). For instance, energy taxation could be classified as both a sufficiency and efficiency policy, but present rates are commonly too low to foster sufficiency (Tvinnereim and Mehling Citation2018). Despite the somewhat disputable distinction, several definitions for sufficiency policy have been proposed. According to the IPCC (Citation2022, 101) sufficiency policies are “a set of measures and daily practices that avoid demand for energy, materials, land and water while delivering human wellbeing for all within planetary boundaries.” Sorrell (Citation2018, 24) describes sufficiency policies as “reductions in the consumption of energy services, with the aim of reducing the energy use and environmental impacts associated with those services.” Many scholars concur with this distinction, arguing that the intention of a policy—to reduce energy use—is crucial in determining whether it should be regarded as a sufficiency policy (Spangenberg and Lorek Citation2019; Thomas et al. Citation2015; Tröger and Reese Citation2021). Such policies can take many forms including, for example, energy taxation, information and communication campaigns, and energy-savings feed-in tariffs (Bertoldi Citation2022).

There are still scientific controversies regarding how to design effective sufficiency-policy packages and targets. Some authors argue that absolute energy targets and energy caps are necessary as they provide long-term incentives to reduce energy use for businesses, households, and society at large (Callmer and Bradley Citation2021; Rijnhout and Mastini Citation2018). In contrast, relative targets, such as energy intensity (kilowatt hours per unit of gross domestic product, or kWh/GDP), do not necessarily provide a clear incentive for energy-use reductions (Burke Citation2020). Others assert that absolute targets may be redundant if stricter financial policies are implemented in the form of, for example, energy taxation that directly targets energy use (Freire-González Citation2020; Sorrell Citation2018). However, tax rates must be ambitious and assessed regularly to move toward sufficiency (Toulouse et al. Citation2017). Although there are varying views, much of the scientific literature concludes that either ambitious energy taxation or caps, as well as absolute energy targets, are a necessary part of an effectual sufficiency-policy package (Jungell-Michelsson and Heikkurinen Citation2022).

It is important to note that sufficiency extends beyond individual actions such as downshifting or voluntary simplicity as such practices could free-up temporal and financial resources and lead to rebound effects (Alcott Citation2008; Sorrell Citation2018). Thus, achieving profound cuts in GHG emissions requires macro-level energy reductions (Jungell-Michelsson and Heikkurinen Citation2022). Consequently, given that energy is essential for most modes of production and consumption, this becomes a multi-dimensional transformation that requires changes in norms, values, and behaviors across social, political, and cultural dimensions, as well as physical infrastructure and production processes (Sorrell Citation2018; Spangenberg and Lorek Citation2019). However, pathways for achieving such a transformation and widespread adoption of sufficiency in policymaking remains largely unexplored in research (Sandberg Citation2021). Nevertheless, we can identify some levers in the literature including enhanced policy integration to ensure that policymakers, as far as possible, consider and account for synergies between separate policy fields (Welch and Southerton Citation2019), reduce science-policy gaps (e.g., through more policy-relevant research) (Fritzsche, Niehoff, and Beier Citation2018), and improve knowledge of the co-benefits of energy-sufficiency policy and recognition of these outcomes (Creutzig et al. Citation2022; Finn and Brockway Citation2023). Sufficiency co-benefits in the form of, for example, social or environmental benefits beyond climate mitigation attributable to sufficiency policies are significant and may lead to improved health and energy security and enhanced biodiversity (Finn and Brockway Citation2023; Karlsson, Alfredsson, and Westling Citation2020).

Barriers to the diffusion of sufficiency policies

Sufficiency barriers refer to societal aspects inhibiting policy adoption (Sandberg Citation2021), for instance the belief that ever-increasing energy use is essential for welfare and well-being (Spangenberg and Lorek Citation2019). However, there are diminishing marginal benefits of energy use and beyond a certain threshold, which affluent countries have long since surpassed, increased energy use does more harm than good (Hickel et al. Citation2021). Other barriers include social norms and behaviors such as consumerist cultures (Gossen, Ziesemer, and Schrader Citation2019), political systems (including governance structures, legislation, and vested power interests) (Lorek and Fuchs Citation2013), physical systems (including fossil-fuel dependency) (Welch and Southerton Citation2019), and lack of vision or deeper understanding of what a society based on sufficiency principles would entail (Tröger and Reese Citation2021). Insufficient understanding of sufficiency on the part of policymakers can also help to explain the lack of policy discussions on this topic (Sandberg Citation2021). The emergence and existence of these barriers are, however, dependent on the social context (Spangenberg and Lorek Citation2019) and the following section considers this factor with respect to Sweden.

The Swedish energy-policy context

Energy policy in Sweden must resonate with and be nested under the relevant laws of the European Union (EU). The Energy Services Directive (ESD) was introduced by the EU to enhance energy security, to manage energy demand, and to promote the deployment of renewables (EU Citation2006). As per the ESD, member states were obliged to provide a triannual National Energy Efficiency Action Plan (NEEAP), indicating their strategies to overcome obstacles to efficient energy use. In 2009, the EU adopted an energy and climate package which aimed to improve energy efficiency by 20% by 2020 (EU Citation2009). The emphasis on energy efficiency was strengthened by adoption of the Energy Efficiency Directive (EED) in 2012, its revision in 2018, and the recast proposal in 2021 (EU Citation2012, Citation2018a, Citation2021). The EED requires all member states to develop National Energy and Climate Plans (NECPs). Following the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 and soaring energy prices, the importance of energy savings was emphasized both in the REPowerEU plan (EU Citation2022b) and in communications from the European Commission (EU Citation2022a). In March 2023, the European Council and the European Parliament agreed on the EED recast proposal, but sufficiency was not mentioned (EU Citation2023). This retrospective shows that sufficiency is still uncommon in European political decisions.

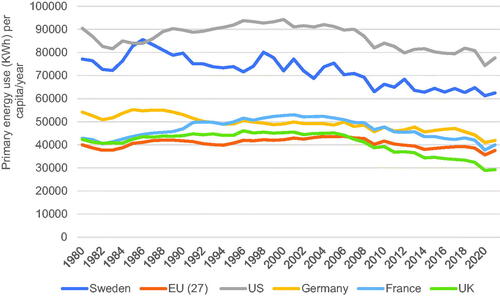

In Sweden, total primary energy usage has remained relatively stable at 500–600 terawatt-hours (TWh) since 1985, while total final energy usage has fluctuated around 380 TWh during the same period (SEA Citation2022).1 Despite a reduction in the share of fossil fuels in the Swedish energy mix since the 1970s, these sources still account for 24% of total primary energy. Simultaneously, population and gross domestic product (GDP) have grown by 19% and 88%, respectively, between 1993 and 2020 (SEA Citation2022). These trends have resulted in a decline of energy intensity (measured in kWh/GDP) by 31% between 2005 and 2020 (SEA Citation2022). Despite this progress and efforts to improve energy efficiency, energy use per capita in Sweden is still 50% higher than the EU average ().

Figure 1. Comparison of primary energy use in kWh per capita/year for the EU-27 and selected European countries, 1980–2021. Sources: BP (Citation2022) and Word Bank (Citationn.d.).

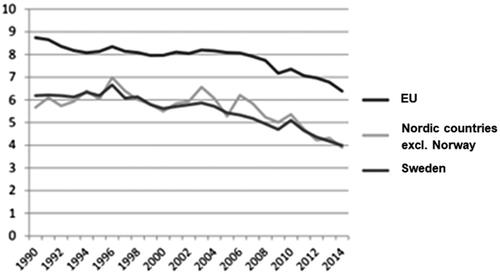

Energy-related GHG emissions in Sweden are lower than the EU average due to a low reliance on fossil fuels in the country’s energy mix (). However, the proportion of energy-related GHG emissions compared to total GHG emissions is similar in Sweden to that of other EU countries (SWEC Citation2017).

Figure 2. Energy-related GHG emissions in Sweden, the Nordic countries (excluding Norway) and the EU, 1990–2014. Source: SWEC (Citation2017).

The Swedish government has set two targets to achieve more efficient energy use including a national target to reduce energy intensity by 50% (kWh/GDP) by 2030 in comparison to 2005 levels and an energy-savings obligation under the EED which indicates that Sweden should achieve 0.8% new annual energy savings by 2030 (SEGOV Citation2017/2018).

The Swedish energy policy is guided by three overarching principles: security of supply, competitiveness, and ecological sustainability (SEGOV Citation2017/2018). The primary strategy to ensure that these principles are fulfilled is through price signaling, achieved through energy and carbon taxation (SFS Citation1990, Citation1994). Nevertheless, environmentally-related taxation has decreased from 6.23% to 4.47% of total tax revenue and from 2.87% to 1.99% of GDP between 1993 and 2020 (Statistics Sweden Citation2021a). Inflation-adjusted energy-tax rates have also declined since the adoption of the carbon tax (Andersson Citation2019).

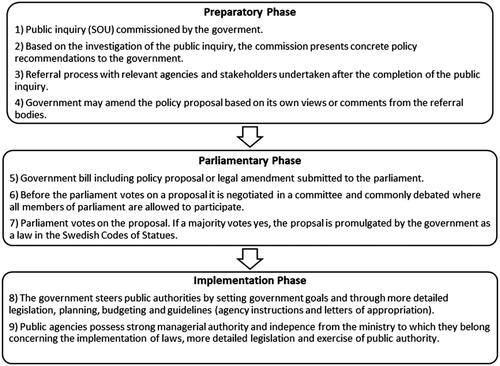

In Sweden, policymaking at the national level rests on an often rigorous policy-preparatory phase (Hall Citation2016). Most policy proposals and legislative amendments related to salient issues are preceded by public inquiries conducted by committees or commissioners working autonomously but still under governmental directives. points to the importance of the Swedish inquiry system and the central role of expert- and often science-based advice in the policy-making process. However, incongruence between public inquiry proposals and government proposals is not uncommon (Hall Citation2016). In the discussion section below, we further elaborate on the potential implications of this situation.

Figure 3. General-level structure of the Swedish national policy-making process. Source: SEGOV (Citation2018).

Materials and methods

Our study is based on a quantitative analysis of parliamentary debates and key energy- and climate-policy documents, as well as a qualitative evaluation of the same key policy documents. The investigation covers four governmental terms of office (2006–2022) that we chose to encompass the period when sufficiency emerged as a concept, the EED was developed and implemented (EU Citation2021), and there were different political coalitions governing Sweden. The timeframe allows us to identify how political decision-making has responded to scientific advances and to spot potential differences between governments across the political spectrum. Parliamentary debates, which were wide-ranging both in character and opinion, were not included in the qualitative analysis, as these results were not relevant to our aim of understanding the general orientation of Swedish energy policy. The following subsections outline the methodological details of our research.

Quantitative keyword analysis

The quantitative analysis centered on the Swedish Riksdag (Parliament) and its debates during the period under examination. We conducted a systematic search in the Parliaments’ open database on protocols from parliamentary debates between October 6, 2006 and September 11, 2022.2 The database allows for the identification of debates based on the use of specific words by parliamentarians. Our analysis is based on the number of parliamentary debates in which a particular keyword was mentioned. The selected keywords were derived from the theoretical section above and include Swedish terms for “energy efficiency” (“energieffektiv*” OR “effektiv* energi*”), “renewable energy” (“förnybar* energi” OR “förnyelsebar* energi”), and “energy sufficiency” (“energihushållning*” OR “hushållning med energi” OR “energibesparing*” OR “spara energi” OR “begräns* energi” OR “minsk* energi”). As the concept of “energy sufficiency” has no corresponding term in Swedish, it was identified by searching for “energy conservation,” “energy savings,” “save energy,” “limit energy use,” and “energy reduction” (Swedish translation above). Prior to the analysis, we manually screened all identified protocols to exclude any irrelevant topics and to ensure the inclusion of only relevant ones. A similar quantitative keyword analysis of the policy documents identified from the qualitative analysis (described below) was also conducted, following the approach outlined above.

Qualitative content analysis

The qualitative content analysis was devoted to proposals from governments in office during the study period and public inquiries preceding the proposals. The first eight years included two four-year, four-party conservative-liberal governments, followed by eight years of a series of social democratic-green and social democratic governments. The identification of relevant governmental proposals started with a broad search in the Swedish Parliament’s open database for governmental bills containing “energy” AND “climate”. This procedure resulted in 432 bills, including budget proposals. We scanned all bills manually, excluding those that (1) were not focused on national energy and climate policy, (2) focused on specific sectors, or (3) focused on specific energy sources. This delimitation was chosen as the aim of our investigation was to explore the overarching Swedish energy-policy strategy and whether sufficiency is a part of it. While acknowledging that the selected bills might not cover all implemented policies, we argue that they are suitable indicators toward this end. Three often-referenced bills on energy taxation were added, given the heavy emphasis on energy taxation. This resulted in eleven bills. We included all public inquiries preceding the identified bills in the analysis, in total five reports. Moreover, since Sweden’s energy policy must comply with the EED (and its predecessor ESD), the country’s NECP, and the four NEEAPs, two government explanatory memorandums on EU policy have also been included. Finally, two often-referenced government communications are part of the study. Altogether, we analyzed 25 policy documents ().

Table 1. Policy documents analyzed by the study.

For the collection of sufficiency policies, taking inspiration from Zell-Ziegler et al. (Citation2021), we defined “sufficiency policy” as any policy that explicitly targets, promotes, encourages, or enables the reduction or limitation of energy use, or explicitly mentions sufficiency. Our definition was deliberately broad to ensure that we did not overlook any policy initiative in support of sufficiency. Given the centrality of energy taxation to achieving energy targets in Sweden and its significance in the sufficiency literature, discussions concerning energy taxation were of particular interest for our analysis. Our scrutiny of each policy document was guided by the following questions:

Is sufficiency as a concept or idea explicitly mentioned or referred to?

Is there any target steering explicitly toward sufficiency?

Are there any concrete sufficiency policies?

Can any barriers to the implementation of sufficiency policies be identified?

Results

Keyword analysis

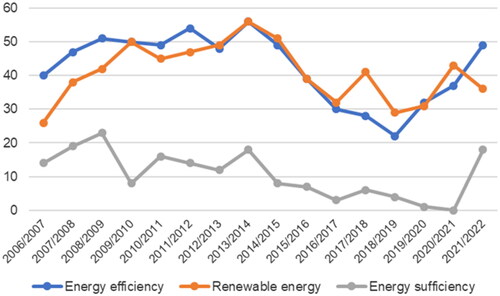

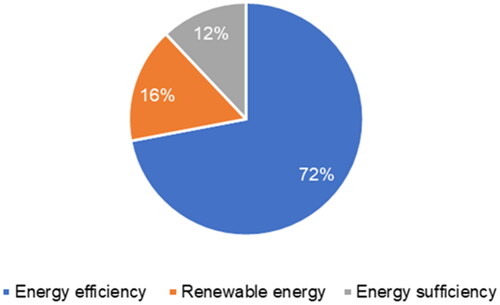

The keyword analysis revealed that “energy efficiency” (n = 681) was the most frequently used concept in Swedish parliamentary debates, followed by “renewable energy” (n = 655) (). “Energy sufficiency” received much less interest (n = 171) and there was no observable trend toward increased use of sufficiency-related keywords during the analyzed period, despite the concept gaining ground in the scientific community. However, we observed a slight shift in 2022, although it should be noted that this year only covered parliamentary debates up until September 11.

Figure 4. Number of parliamentary debates mentioning energy efficiency, renewable energy, and energy sufficiency in 2006−2022 (the figures in 2006 and 2022 only cover parts of the year due to national elections in September).

The keyword analysis of the policy documents retrieved from the qualitative analysis indicate similar patterns (). The policy documents emphasized efficiency to a higher degree compared to renewable energy and even more so compared to energy sufficiency.

Figure 5. Energy efficiency, renewable energy, and energy sufficiency in selected energy-policy documents between 2006−2022.

Admittedly, these quantitative results say nothing about the content of the debate or the policy documents, but they clearly indicate that sufficiency is not a widely-used concept in Swedish policy discussions in the Parliament. The qualitative investigation below provides more in-depth analysis.

Qualitative analysis

The qualitative results focus on the extent and content of sufficiency in Swedish energy-policy proposals and potential barriers inhibiting the adoption of such policies. We have translated the quotations below from their original Swedish.

Negligence of sufficiency

The concept of sufficiency is not explicitly referenced in Swedish energy policy. Rather, the emphasis is repeatedly placed on energy efficiency and the proliferation of renewables as the fundamental pillars of energy policy (SEGOV Citation2008/2009b). To achieve the energy-efficiency target of reducing energy intensity by 50% by 2030 relative to 2005 levels, the Swedish government states:

Energy intensity depends on, besides GDP growth, primary energy use which, in turn, depends on renewable energy measures, energy efficiency, structural industry change, the future of nuclear power and general economic development. (NECP Citation2020, 26)

The second component of Swedish energy policy focuses on the proliferation of renewable energy, including biofuels. Throughout the bills and inquiries, the government expresses support for the development of renewable energy and has implemented several policies to promote the diffusion of such technologies. These policies include the GHG reduction mandate which encourages a greater share of biofuels in diesel and petrol (SEGOV Citation2019/2020), a system of financial support for solar and wind power (NECP Citation2020), an electricity-certificate system for renewable energy (NECP Citation2020), and a series of informative measures such as energy-advisory services (SEGOV Citation2019/2020).

Sweden has good prerequisites for renewable energy production and the government considers, aligned with the Energy Commission, that this should be encouraged. The technical development within renewable energy has been fast and continues to be so. Costs for new technology have simultaneously decreased significantly. (SEGOV Citation2017/2018, 24)

The overarching focus of Swedish energy policy is well-captured in discussions about reducing climate impacts from transportation. The government states that “the degree of electrification, energy-efficiency improvements and the proportion of sustainable renewable fuels are the factors with the largest impact on the development of GHG emissions from transportation” (SEGOV Citation2019/2020, 100). It is apparent that reducing traffic is not a primary strategy for decarbonizing transportation.

Lack of national target toward sufficiency

Swedish energy policy does not include a target for sufficiency (SEGOV Citation2019/2020). The energy-efficiency target of 50% is relative and can, therefore, be achieved without actual reductions in energy use provided GDP grows apace (NECP Citation2020). The government asserts that setting absolute targets for energy use is ineffective as it disregards economic development, potentially resulting in socioeconomically suboptimal decisions (SEGOV Citation2019/2020). Nevertheless, reductions in energy use may become a necessary but costly consequence if GDP grows less than expected (Swedish Government Communication Citation2015/2016).

The Energy Commission’s impact analysis shows that the target for energy use shall be calculated as the quotient between supplied energy and GDP in real prices (kWh/GDP). Compared to an absolute target for energy savings, as the EU target is designed, it provides a partially flexible roof for energy use since it considers the actual economic development. (SEGOV Citation2017/2018, 21)

Under the EED, Sweden should achieve 0.8% new annual energy savings in terms of final energy (EU Citation2018b). However, the achievement of this target does not necessarily entail absolute energy-use reductions, as the EU provides flexibility in how these savings are calculated. Sweden has chosen to utilize a counterfactual scenario method in which energy savings constitute the difference between enacted policies and a scenario without such policies. Since energy taxation is the main instrument to steer energy use, energy savings are calculated as resulting from the difference between the EU’s minimum energy-tax requirements under the Energy Taxation Directive (EU Citation2003) and the Swedish energy-tax level (NECP Citation2020). The government anticipates that the annual 0.8% savings will be achieved in the building and transportation sectors, whereas other sectors are not expected to achieve any energy savings (NECP Citation2020). Despite the flexibility of the target, the government is apprehensive toward the European Commission’s proposal to increase the annual energy-savings obligation under the EED.

The government considers that an increase in the annual energy savings obligation to 1.5% of the annual final energy consumption between 2024 and 2030 reduces the Member States’ possibility to carry out socioeconomically effective energy and climate policy. (Explanatory Memorandum 2021, 7).

Seeds of sufficiency policies but net effect is unclear

We have identified a few policies that could be classified as suggestive of sufficiency. Of these initiatives, energy taxation (as well as carbon taxation) has historically been and remains crucial to achieving Sweden’s energy targets. While initially introduced for fiscal purposes, energy taxation now has a greater focus on steering resource use (SEGOV Citation2017/2018, 2008/2009b).

Energy and carbon taxes make the use of energy more expensive and thus creates an incentive for energy users to adopt energy-saving measures to reduce or make energy use more effective. (NECP Citation2020, 85)

The Swedish government argues that energy and carbon taxation have been fundamental to territorial GHG emission reductions (SEGOV Citation2017/2018). Between 2011 and 2016, these types of releases were reduced by 16% (Statistics Sweden Citation2021b). Since taxation is the main policy instrument, it is fair to assume that the taxes have contributed to this reduction. One of the explanatory memorandums (Explanatory Memorandum Citation2013, 17) notes that “[I]f we for some reason want to save energy, a tax on energy will do the job, and there is no need for any further measures.”

The net effect of energy taxation, however, depends on the tax rate. Although nominal energy taxation has been increased in recent decades (SFS Citation2021), the government’s revenue from energy taxation relative to total tax revenue and GDP has still been low when compared to other EU countries (Eurostat Citation2020). Furthermore, primary energy use has remained steady since the mid-1980s (SEA Citation2022). In response to the COVID-19 pandemic and rising energy prices in 2022, the government implemented energy-tax deductions for companies (SEGOV Citation2021/2022) as well as for petrol and diesel to alleviate the financial pressure on businesses and households (SEGOV Citation2021/2022). However, the latter deduction was introduced for social and competitiveness reasons, with the government acknowledging that “this, ceteris paribus, will increase GHG emissions” (SEGOV Citation2021/2022, 15).

Other complementary policies that could promote sufficiency include abolishing tax deductions for heating and operations in certain sectors, supporting public transportation, making investments in cycling and walking, endorsing the GHG reduction mandate, creating energy-advisory services, establishing bonus malus schemes3 for light vehicles, implementing building and property regulations, fostering eco-design requirements for energy-related products, instituting energy-performance standards and eco-bonus systems to facilitate a transition from road to rail and shipping transportation (NEEAP Citation2006, Citation2011, Citation2014, Citation2017; NECP Citation2020; SEGOV Citation2020/2021b). Most of these policies are related to the transportation and building sectors. The government suggests that these initiatives can address information deficits, increase awareness and knowledge of energy-saving practices, and enhance the legitimacy of these measures and their potential to foster energy savings (NECP Citation2020). Although only considered as supporting the general financial instruments, they could promote sufficiency but receive far less attention than energy taxation (NEEAP Citation2017; NECP Citation2020, SEGOV Citation2017/2018). For instance, the GHG reduction mandate is a key policy to lower emissions from transportation but is not extensively discussed in the NEEAPs or the NECP and is not assessed as contributing to reduced energy use. Additionally, this measure does not have an upper limit on energy use or emissions. Therefore, its potential contribution to emissions reductions depends on its tax rate, which is subject to change, and is not elaborated on extensively in the policy documents that we analyzed. Overall, the net effect of complementary policies in terms of potential energy reductions is unclear and not assessed with respect to the energy-efficiency target (NECP Citation2020).

Sufficiency orientation inhibited by concerns for industrial competitiveness

The most important barrier to sufficiency as identified in discussions about Swedish energy policy is that steering toward sufficiency could potentially hinder industrial competitiveness. Many energy-intensive industries covered by EU Emissions Trading System (EU-ETS) are exempted or receive deductions from energy taxation (SEGOV Citation2017/2018). In the absence of an international carbon tax which, according to the government, could result in carbon leakage4 (NECP Citation2020), the government refers to economic theory to justify these exceptions.

The National Institute for Economics Research notes that a cost-effective climate policy builds on a uniform carbon price. Exceptions and reductions of the carbon tax could however be necessary for reasons of competitiveness. (SEGOV Citation2019/2020, 55)

Although the Swedish electricity grid has relatively low input of fossil fuels, and energy-intensive industries have a comparatively small carbon footprint, energy-intensive industries are responsible for one-third of total GHG emissions (SEGOV Citation2019/2020). However, the primary focus of the bills that we studied is put on industrial growth to ensure the export of novel climate solutions such as so-called “fossil-free” steel (SEGOV Citation2019/2020). We note that the production of “fossil-free” steel requires substantially more energy compared to conventional steel, but the Swedish government has argued that this is necessary to support these new technologies (NECP Citation2020). In fact, it has been contended that the country should use the climate and energy challenges as “economic levers” to increase exports of such products and techniques (SEGOV Citation2008/2009b, 52).

Sweden will show that it is possible to transform to a fossil-free country with maintained competitiveness and welfare…Sweden can contribute to reducing emissions beyond Swedish borders by exporting climate-smart energy and other climate-smart solutions. (SEGOV Citation2019/2020, 9)

Discussion and policy implications

This study shows that Swedish energy policy has given limited attention to sufficiency. The keyword analysis indicates a predominant focus on energy efficiency and renewable energy in both parliamentary debates and policy documents. This finding is supported by the qualitative review of relevant materials over the last four governmental terms of office. Interestingly, there is no discernible difference between liberal-conservative and social democratic-green governments. There is thus no obvious reason to assume that government composition has had any significant effect on the enacted policies in Sweden. Furthermore, there is no target for sufficiency in Sweden’s energy policy. While energy savings are mentioned sparingly and described as important for achieving energy and climate targets, there is no absolute target designed to steer toward reductions of energy use. Given that energy savings are considered counterfactually, that is, calculated as the difference between a scenario with explicit policies and a scenario without these policies, energy policy is not geared toward achieving energy reductions from current levels but rather toward avoiding increased energy use.

While important, avoidance of future potential energy use may not be adequate for rapid climate mitigation. The government even expresses an intention to work against an increased energy-savings obligation under the revised EED. Clearly, setting limits on or reducing energy use are presently not seen as politically prioritized strategies. Furthermore, Sweden predominantly relies on policies supporting technological development to improve energy efficiency and to accelerate the deployment of renewables. Embracing sufficiency would, of course, constitute a major shift as it would conflict with dominant contemporary economic and political values, requiring policymakers to understand the limits of energy efficiency and renewable energy deployment.

Although rebound effects are acknowledged in comprehensive public inquiries, this knowledge has not translated into concrete policy action. Additionally, Sweden relies heavily on financial instruments, particularly energy taxation. While often considered a key component of sufficiency-policy packages (van den Bergh Citation2011), current energy-tax rates are likely too low to steer toward absolute energy-use reductions. Recent years have seen a decrease in inflation-adjusted values of energy-tax rates and there is no indication of a reversal of this trend. Sweden also falls short of meeting the EU-wide primary energy ambition according to evaluations of the efficiency targets of EU member states in the 2020 NECP. Further, the overall intention to improve energy intensity has not increased in recent years (Economidou et al. Citation2022).

The Swedish government has implemented complementary policies in the transportation and building sectors. While these initiatives contain seeds of sufficiency, few of them are specifically targeted toward or assessed by the government as contributing to energy-use reductions. This lack of emphasis on sufficiency suggests the presence of sufficiency barriers in Swedish energy policy. In the following subsections, we identify two such barriers and discuss future avenues for research to help overcome them.

Science-policy gap

Moving beyond efficiency and toward sufficiency is imperative, particularly in affluent countries like Sweden. Our analysis reveals that Swedish policymakers either disregard or lack awareness of the role of sufficiency in achieving profound and rapid emissions reductions. Other recent studies draw similar conclusions (see, e.g., Callmer and Bradley Citation2021). Although we cannot conclude based on our analysis whether this negligence is deliberate or unintentional, a clear gap exists between scientific recommendations and policy action. To address this disparity, conducting case studies to enable policymakers to engage with and to comprehend the necessity of sufficiency could be a fruitful path for research. Additionally, there is an urgent need to understand dimensions of public support for sufficiency-oriented policies. Prior studies have suggested that policymakers avoid consideration of sufficiency because it might provoke public opposition (Gossen, Ziesemer, and Schrader Citation2019; Sandberg Citation2021). However, there has been a paucity of work to validate this contention. Since public opinion plays a key role in policymaking (especially in democratic countries such as Sweden), investigating public attitudes toward sufficiency policies could provide valuable insights. In addition, an important lever could be to more effectively communicate sufficiency co-benefits to policymakers as the framing of sufficiency policies has been shown to affect public attitudes (Jensen et al. Citation2019). Finally, further interdisciplinary research that incorporates social sciences to understand the social and collective aspect of energy use could offer additional insights beyond the conventional economic and behavioral science perspectives (Bertoldi Citation2022).

Conflict between sufficiency and green industrial competitiveness

In light of anticipated and unprecedented investments in clean technologies and the ambition to be at the front of green innovation (e.g., “fossil-free” steel) our analysis demonstrates that sufficiency may be regarded as a threat to the envisioned Swedish eco-industrial transformation. The reluctance of the country’s policymakers to increase energy taxation appears to stem from the belief that this would impede economic growth, restrain industrial competitiveness, and discourage investments in energy-intensive solutions. Consequently, steering toward a reduction in overall energy usage becomes less desirable. Although seemingly logical, the pursuit of more energy use by industry does not render sufficiency irrelevant, but rather more important, since it implies planned reduction of unnecessary energy use rather than a dramatic reduction of most energy consumption (Sorrell Citation2018). A sufficiency approach could reduce energy demand, thereby creating space for investments in – and expediting the development of – climate solutions (Creutzig et al. Citation2018; Grubler et al. Citation2018). However, research exploring the sufficiency-industry relationship is scarce (Sandberg Citation2021) and more knowledge is required to better understand the generally accepted conflict.

Climate-progressive Sweden?

The key finding of our analysis is that sufficiency is not considered to be a viable strategy in Swedish energy policy. Although energy savings are occasionally mentioned, regulations aimed at achieving absolute energy-use reductions are rarely considered, let alone implemented in actual policies. Consequently, it is reasonable to question the conception of Sweden as a “climate-progressive” country. While Sweden has continuously implemented progressive climate policies, such as a carbon tax in the early 1990s, and been recognized as a climate leader by the scientific community (e.g., Sarasini Citation2009; Karlsson Citation2021), the apparent disregard for sufficiency policies calls this conception into question. This is particularly pertinent from the standpoint of EU policymaking, with the European Commission strengthening energy targets and setting ambitious plans to reduce energy use. In Sweden, however, reducing GHG emissions has been sidelined in favor of addressing financial turmoil, and subsequently rates of energy taxation have been lowered to ameliorate social and economic concerns. While scientists advocate for stronger sufficiency efforts across policy fields to meet set targets, the space for sufficiency in policy discussions and strategies in Sweden is limited.

Conclusion

In this article, we have disclosed that sufficiency at best remains at the periphery of Swedish energy policy. The country currently lacks a target for energy sufficiency, and while a few policies contain seeds of sufficiency, they are inadequate to achieve rapid reductions of energy-related GHG emissions. Our analysis concludes that the primary barriers hindering the adoption of sufficiency policies in Sweden include a lack of consideration of scientific evidence related to the need for sufficiency in the policy-making process and the perceived conflict between sufficiency and industrial competitiveness. Additionally, concerns for well-being may also impede the adoption of sufficiency polices in Sweden. We contend that more research is required to understand the perceptions of policymakers with respect to the relationship between energy-use reductions and well-being as the notion that high energy use is fundamental to societal welfare may hinder proposals to advance sufficiency policies.

Despite the growing tendency toward sufficiency within the EU in response to the concurrent and inextricably interrelated energy and climate crises, Swedish policies continue to rely on conventional and technology-focused strategies. The implications for Sweden of these contradictory developments remain to be seen. What can be asserted is that the gap between what science prescribes and policy delivers poses a significant risk to the achievement of Sweden’s energy and climate targets. To meet these objectives, it is essential that sufficiency becomes a primary focus rather than remaining on the sidelines of the country’s energy policies.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Correction Statement

This article was originally published with errors, which have now been corrected in the online version. Please see Correction (http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15487733.2023.2226002)

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The difference between primary and final energy usage is mainly losses related to nuclear power plants, and to some extent losses due to transmission and transformation.

2 See https://data.riksdagen.se/in-english. The selected dates coincide with the parliamentary elections in 2006 and 2022, respectively, which constitute the dates for new terms of office.

3 Bonus malus schemes reward vehicles that emit fewer carbon-dioxide (CO2) emissions (bonus) and punishes vehicles that emit more CO2 emissions (malus).

4 Carbon leakage may occur when companies move production to countries with weaker emission regulations due to high climate-policy costs, leading to increased emissions and undermining efforts to reduce GHGs.

References

- Alcott, B. 2008. “The Sufficiency Strategy: Would Rich-world Frugality Lower Environmental Impact.” Ecological Economics 64 (4): 1–15. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2007.04.015.

- Andersson, J. 2019. “Carbon Taxes and CO2 Emissions: Sweden as a Case Study.” American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 11 (4): 1–30. doi:10.1257/pol.20170144.

- Bertoldi, P. 2022. “Policies for Energy Conservation and Sufficiency: Review of Existing Policies and Recommendations for New and Effective Policies in OECD Countries.” Energy and Buildings 264: 112075. doi:10.1016/j.enbuild.2022.112075.

- British Petroleum (BP). 2022. Statistical Review of World Energy. London: BP.

- Brischke, L., L. Leuser, C. Baedeker, F. Lehmann, and S. Thomas. 2015. “Energy Sufficiency in Private Households Enabled by Adequate Appliances.” Proceedings of the European Council for an Energy Efficient Economy Summer Study 2015: 1571–1582.

- Brockway, P., S. Sorrell, G. Semieniuk, M. Kuperus Heun, and V. Court. 2021. “Energy Efficiency and Economy-wide Rebound Effects: A Review of the Evidence and Its Implications.” Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 141: 110781. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2021.110781.

- Burke, W. 2020. “Energy-sufficiency for a Just Transition: A Systematic Review.” Energies 13 (10): 2444. doi:10.3390/en13102444.

- Callmer, Å., and K. Bradley. 2021. “In Search of Sufficiency Politics: The Case of Sweden.” Sustainability: Science, Practice, and Policy 17 (1): 194–208. doi:10.1080/15487733.2021.1926684.

- Cross-Party Committee on Environmental Objectives (CPCEO). 2016a. Ett Klimatpolitiskt Ramverk För Sverige [A Climate Policy Framework for Sweden]. Stockholm: Fritzes.

- Cross-Party Committee on Environmental Objectives (CPCEO). 2016b. En Klimat- Och Luftvårdsstrategi För Sverige [A Climate and Air-protection Strategy for Sweden]. Stockholm: Fritzes.

- Creutzig, F., J. Roy, W. Lamb, I. Azevedo, W. Bruine de Bruin, H. Dalmann, O. Edelenbosch, et al. 2018. “Towards Demand-side Solutions for Mitigating Climate Change.” Nature Climate Change 8 (4): 260–263. doi:10.1038/s41558-018-0121-1.

- Creutzig, F., L. Niamir, X. Bai, M. Callaghan, J. Cullen, J. Díaz-José, M. Figueroa, et al. 2022. “Demand-side Solutions to Climate Change Mitigation Consistent with High Levels of Well-being.” Nature Climate Change 12 (1): 36–46. doi:10.1038/s41558-021-01219-y.

- Committee on Small Energy Players (CSEP). 2018. Mindre Aktörer i Energilandskapet [Smaller Players in the Energy Landscape]. Stockholm: CSEP.

- Daly, H. 1977. Steady State Economics: The Economics of Biophysical and Moral Growth. San Francisco, CA: W.F. Freeman.

- Darby, S. 2007. Enough Is as Good as a Feast—Sufficiency as Policy. Oxford: Oxford University Centre for the Environment.

- Darby, S., and T. Fawcett. 2018. Energy Sufficiency: An Introduction. Stockholm: European Council for Energy Efficient Economy.

- Della Valle, N., and P. Bertoldi. 2022. “Promoting Energy Efficiency: Barriers, Societal Needs and Policies.” Frontiers in Energy Research 9: 804091. doi:10.3389/fenrg.2021.804091.

- Di Gulio, A., and D. Fuchs. 2014. “Sustainable Consumption Corridors: Concept, Objections, and Responses.” GAIA 23 (3): 184–192. doi:10.14512/gaia.23.S1.6.

- Economidou, M., M. Ringel, M. Valentova, L. Castellazzi, P. Zancanella, P. Zangheri, T. Serrenho, D. Paci, and P. Bertoldi. 2022. “Strategic Energy and Climate Policy Planning: Lessons Learned from European Energy Efficiency Policies.” Energy Policy 171: 113225. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2022.113225.

- European Union (EU). 2003. Directive 200396/EC Restructuring the Community Framework for the Taxation of Energy Products and Electricity. Brussels: EU.

- European Union (EU). 2006. Directive 2006/32/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council on Energy End-use Efficiency and Energy Services. Brussels: EU.

- European Union (EU). 2009. Directive 2009/2008/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council on the Promotion of the Use of Energy from Renewable Sources. Brussels: EU.

- European Union (EU). 2012. Directive 2012/27/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council on Energy Efficiency. Brussels: EU.

- European Union (EU). 2018a. Directive 2018/2002/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council Amending Directive 2012/27/EU on Energy Efficiency. Brussels: EU.

- European Union (EU). 2018b. Regulation (EU) 2018/1999 of the European Parliament and of the Council on the Governance of the Energy Union and Climate Action. Brussels: EU.

- European Union (EU). 2021. Proposal for a Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council on Energy Efficiency (Recast). Brussels: EU.

- European Union (EU). 2022a. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions: EU: “Save Energy .” Brussels: EU.

- European Union (EU). 2022b. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the European Council, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions REPowerEU Plan. Brussels: EU.

- European Union (EU). 2023. Proposal for a Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council on Energy Efficiency (Recast) – Analysis of the Final Compromise Text with a View to Agreement. Brussels: EU.

- Eurostat. 2020. Environmental Tax Statistics. Luxembourg: Eurostat.

- Explanatory Memorandum. 2013. Plan for Implementation of Article 7 of the Energy Efficiency Directive, N2013/5035/E. Stockholm: Government Offices of Sweden.

- Explanatory Memorandum. 2021. Direktivet om Energieffektivitet [Directive on Energy Efficiency], 2020/21:FPM:134. Stockholm: Government Offices of Sweden.

- Figge, F., W. Young, and R. Barkemeyer. 2014. “Sufficiency or Efficiency to Achieve Lower Resource Consumption and Emissions? The Role of the Rebound Effect.” Journal of Cleaner Production 69: 216–224. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2014.01.031.

- Fossil Free Transport Committee (FFTC). 2013. Fossilfrihet på Väg [Fossil Freedom on the Way], SOU 2013:84. Stockholm: Fritzes.

- Finn, O., and P. Brockway. 2023. “Much Broader than Health: Surveying the Diverse Co-benefits of Energy Demand Reduction in Europe.” Energy Research & Social Science 95: 102890. doi:10.1016/j.erss.2022.102890.

- Freire-González, J. 2020. “Energy Taxation Policies Can Counteract the Rebound Effect: Analysis within a General Equilibrium Framework.” Energy Efficiency 13 (1): 69–78. doi:10.1007/s12053-019-09830-x.

- Fritzsche, K., S. Niehoff, and G. Beier. 2018. “Industry 4.0 and Climate Change–Exploring the Science-policy Gap.” Sustainability 10 (12): 4511. doi:10.3390/su10124511.

- Gossen, M., F. Ziesemer, and U. Schrader. 2019. “Why and How Commercial Marketing Should Promote Sufficient Consumption: A Systematic Literature Review.” Journal of Macromarketing 39 (3): 252–269. doi:10.1177/0276146719866238.

- Grubler, A., C. Wilson, N. Bento, B. Boza-Kiss, V. Krev, D. McCollum, N. Rao, et al. 2018. “A Low Energy Demand Scenario for Meeting the 1.5 °C Target and Sustainable Development Goals without Negative Emission Technologies.” Nature Energy 3 (6): 515–527. doi:10.1038/s41560-018-0172-6.

- Hall, P. 2016. “The Swedish Administrative Model.” In The Oxford Handbook of Swedish Politics, edited by J. Pierre, 299–314. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hickel, J., P. Brockway, G. Kallis, L. Keyßer, M. Lenzen, A. Slameršak, J. Steinberger, and D. Ürge-Vorsatz. 2021. “Urgent Need for Post-growth Climate Mitigation Scenarios.” Nature Energy 6 (8): 766–768. doi:10.1038/s41560-021-00884-9.

- Hotta, Y., T. Tasaki, and R. Koide. 2021. “Expansion of Policy Domain of Sustainable Consumption and Production (SCP): Challenges and Opportunities for Policy Design.” Sustainability 13 (12): 6763. doi:10.3390/su13126763.

- Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES)). 2019. Summary for Policymakers of the Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. Bonn: IPBES.

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). 2022. Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Jensen, C., G. Goggins, I. Røpke, and F. Fahy. 2019. “Achieving Sustainability Transitions in Residential Energy Use across Europe: The Importance of Problem Framings.” Energy Policy 133: 110927. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2019.110927.

- Jungell-Michelsson, J., and P. Heikkurinen. 2022. “Sufficiency: A Systematic Literature Review.” Ecological Economics 195: 107380. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2022.107380.

- Karlsson, M. 2021. “Sweden’s Climate Act.” Climate Policy 21 (9): 1132–1145. doi:10.1080/14693062.2021.1922339.

- Karlsson, M., E. Alfredsson, and N. Westling. 2020. “Climate Policy Co-benefits: A Review.” Climate Policy 20 (3): 292–316. doi:10.1080/14693062.2020.1724070.

- Lorek, S., and D. Fuchs. 2013. “Strong Sustainable Consumption Governance: A Precondition for a Degrowth Path?” Journal of Cleaner Production 38: 36–43. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2011.08.008.

- Meadows, D., D. Meadows, J. Randers, and W. Behrens. 1972. The Limits to Growth: A Report for the Club of Rome’s Project on the Predicament of Mankind. New York: Universe Books.

- Millward-Hopkins, J., J. Steinberger, N. Rao, and Y. Oswald. 2020. “Providing Decent Living with Minimum Energy: A Global Scenario.” Global Environmental Change 65: 102168. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2020.102168.

- National Energy and Climate Plan (NECP). 2020. Sweden’s Integrated National Energy and Climate Plan. Stockholm: NECP.

- National Energy Efficiency Action Plan (NEEAP). 2006. Sweden’s First National Energy Efficiency Action Plan. Stockholm: NEEAP.

- National Energy Efficiency Action Plan (NEEAP). 2011. Sweden’s Second National Energy Efficiency Action Plan. Stockholm: NEEAP.

- National Energy Efficiency Action Plan (NEEAP). 2014. Sweden’s Third National Energy Efficiency Action Plan. Stockholm: NEEAP.

- National Energy Efficiency Action Plan (NEEAP). 2017. Sweden’s Fourth National Energy Efficiency Action Plan. Stockholm: NEEAP.

- O’Neill, D., A. Fanning, W. Lamb, and J. Steinberger. 2018. “A Good Life for All within Planetary Boundaries.” Nature Sustainability 1 (2): 88–95. doi:10.1038/s41893-018-0021-4.

- Princen, T. 2005. The Logic of Sufficiency. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Rao, N., and J. Min. 2018. “Decent Living Standards: Material Prerequisites for Human Wellbeing.” Social Indicators Research 138 (1): 225–244. doi:10.1007/s11205-017-1650-0.

- Rijnhout, L., and R. Mastini. 2018. Sufficiency: Moving beyond the Gospel of Eco-Efficiency. Brussels: Friends of the Earth Europe.

- Samadi, S., M.-C. Gröne, U. Schneidewind, H.-J. Luhmann, J. Venjakob, and B. Best. 2017. “Sufficiency in Energy Scenario Studies: Taking the Potential Benefits of Lifestyle Changes into Account.” Technological Forecasting and Social Change 124: 126–134. doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2016.09.013.

- Sandberg, M. 2021. “Sufficiency Transitions: A Review of Consumption Changes for Environmental Sustainability.” Journal of Cleaner Production 293: 126097. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.126097.

- Santarius, T., H. Walnum, and C. Aall. 2016. “Introduction: Rebound Research in a Warming World.” In Rethinking Climate and Energy Policies, edited by T. Santarius and H. Walnum, 1–14. Cham: Springer.

- Sarasini, S. 2009. “Constituting Leadership via Policy: Sweden as a Pioneer of Climate Change Mitigation.” Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies for Global Change 14 (7): 635–653. doi:10.1007/s11027-009-9188-3.

- Swedish Energy Agency (SEA). 2022. Energiindikatorer 2022 [Energy Indicators 2022]. Stockholm: SEA.

- Swedish Government (SEGOV). 1975. Proposition (1975:30) om Energihushållningen [Governmental Bill (1975:30) on Energy Management]. Stockholm: SEGOV.

- Swedish Government (SEGOV). 2008/2009a. Proposition (2008/09:162). En Sammanhållen Klimat- Och Energipolitik: Klimat [Coherent Climate and Energy Politics: Climate]. Stockholm: SEGOV.

- Swedish Government (SEGOV). 2008/2009b. Proposition (2008/09:163). En Sammanhållen Klimat- Och Energipolitik: Energi [Coherent Climate and Energy Politics: Energy]. Stockholm: SEGOV.

- Swedish Government (SEGOV). 2012/2013. Proposition (2012/13:21). Forskning Och Innovation För Ett Långsiktigt Hållbart Energisystem [Research and Innovation for a Long-term and Sustainable Energy System]. Stockholm: SEGOV.

- Swedish Government (SEGOV). 2013/2014. Proposition (2013/14:174). Genomförande av Energieffektiviseringsdirektivet [Realization of the Energy-efficiency Directive]. Stockholm: SEGOV.

- Swedish Government (SEGOV). 2016/2017b. Proposition (2016/17:66). Forskning Och Innovation på Energiområdet För Ekologisk Hållbarhet, Konkurrenskraft Och Försörjningstrygghet [Research and Innovation in the Energy Field for Ecological Sustainability,Competitiveness and Security of Supply]. Stockholm: SEGOV.

- Swedish Government (SEGOV). 2016/2017a. Proposition (2016/17:146). Ett Klimatpolitiskt Ramverk För Sverige [A Climate Policy Framework for Sweden]. Stockholm: SEGOV.

- Swedish Government SEGOV) 2017/2018. Proposition (2017/18:228). Energipolitikens Inriktning [The Orientation of Energy Politics]. Stockholm: SEGOV.

- Swedish Government (SEGOV). 2018. Swedish Legislation – How Laws Are Made. Stockholm: SEGOV.

- Swedish Government (SEGOV). 2019/2020. Proposition (2019/20:65). En Samlad Politik För Klimatet – Klimatpolitisk Handlingsplan[A Unified Policy for the Climate – Climate Policy Action Plan]. Stockholm: SEGOV.

- Swedish Government (SEGOV). 2020/2021a. Proposition (2020/21:65). Tillfällig Utvidgning av Statligt Stöd Genom Nedsatt Energiskatt [Temporary Extension of State Support through Energy-tax Deduction]. Stockholm: SEGOV.

- Swedish Government (SEGOV). 2020/2021b. Proposition (2020/21:97). Slopad Nedsättning av Energiskatt på Bränslen i Vissa Sektorer [Abolition of Energy-tax Deductions on Fuel in Certain Sectors]. Stockholm: SEGOV.

- Swedish Government (SEGOV). 2021/2022. Proposition (2021/22:84) Sänkt Energiskatt på Bensin Och Diesel [Reduced Energy Tax on Petrol and Diesel]. Stockholm: SEGOV.

- Swedish Environmental Protection Agency (SEPA). 2022. Fördjupad Analys av Den Svenska Klimatomställningen 2021 [In-Depth Analysis of the Swedish Climate Transformation 2021]. Stockholm: SEPA.

- Swedish Code of Statues (SFS). 1990. Lagen (1990:582) om Koldioxidskatt [Law on Carbon Taxation]. Stockholm: Swedish Government.

- Swedish Code of Statues (SFS). 1994. Lag (1994:1776) om Skatt på Energi [Law on Energy Taxation]. Stockholm: Swedish Government.

- Swedish Code of Statues (SFS). 2021. Förordning (2021:1078) om Fastställande av Omräknat Belopp För Energiskatt på Elektrisk Kraft För år 2022 [Ordinance on Determining the Recalculated Value of Energy Taxation on Electric Power for the Year 2022]. Stockhom: Swedish Government.

- Sorrell, S. 2018. Energy Sufficiency and Rebound Effects. Brussels: European Council for an Energy Efficiency Economy.

- Spangenberg, J., and S. Lorek. 2019. “Sufficiency and Consumer Behavior: From Theory to Policy.” Energy Policy 129: 1070–1079. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2019.03.013.

- Statistics Sweden. 2021a. Totala Miljöskatter i Sverige 1993–2020 [Total Environmental Taxes in Sweden 1993–2020]. Stockholm: Statistics Sweden.

- Statistics Sweden. 2021b. Totala Utsläpp av Växthusgaser Efter Växthusgas, Sektor Och år [Total Emissions of Greenhouse Gases according to Greenhouse Gas, Sector and Year]. Stockholm: Statistics Sweden.

- Swedish Energy Commission (SWEC). 2017. Kraftsamling För Framtidens Energi [Power Pool for Future Energy]. Stockholm: Fritzes.

- Swedish Government Communication. 2015/2016. Kontrollstation För de Klimat Och Energipolitiska Målen till 2020 Samt Klimatanpassning [Control Station of the Climate and Energy Policy Targets for 2020 and Climate Adaptation]. Stockholm: Swedish Government.

- Swedish Government Communication. 2018/2019. Första Kontrollstationen För Energiöverenskommelsen [First Control Station of the Energy Agreement]. Stockholm: Swedish Government.

- Thomas, S., L.-A. Brischke, J. Thema, and M. Kopatz. 2015. “Energy Sufficiency Policy: An Evolution of Energy Efficiency Policy or Radically New Approaches?” Proceedings of the European Council for an Energy Efficient Economy Summer Study 2015: 59–70.

- Toulouse, E., M Le Du, H. Gorge, and L. Semal. 2017. “Stimulating Energy Sufficiency: Barriers and Opportunities.” Proceedings of the European Council for an Energy Efficient Economy Summer Study 2017: 59–68.

- Tröger, J., and G. Reese. 2021. “Talkin’ Bout a Revolution: An Expert Interview Study Exploring Barriers and Keys to Engender Change towards Societal Sufficiency Orientation.” Sustainability Science 16 (3): 827–840. doi:10.1007/s11625-020-00871-1.

- Tvinnereim, E., and M. Mehling. 2018. “Carbon Pricing and Deep Decarbonisation.” Energy Policy 121: 185–189. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2018.06.020.

- Vadovics, E., and L. Živčič. 2019. “Energy Sufficiency: Are We Ready for It? An Analysis of Sustainable Energy Initiatives and Citizen Visions.” Proceedings of European Council for an Energy Efficient Economy Summer Study 2019: 159–168.

- van den Bergh, J. 2011. “Energy Conservation More Effective with Rebound Policy.” Environmental and Resource Economics 48 (1): 43–58. doi:10.1007/s10640-010-9396-z.

- Welch, D., and D. Southerton. 2019. “After Paris: Transitions for Sustainable Consumption.” Sustainability: Science, Practice, and Policy 15 (1): 31–44. doi:10.1080/15487733.2018.1560861.

- Wiedmann, T., H. Schandl, M. Lenzen, and K. Kanemoto. 2015. “The Material Footprint of Nations.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 112 (20): 6271–6276. doi:10.1073/pnas.1220362110.

- World Bank, n.d. “Population Data Services.” Washington, DC: World Bank.

- Zell-Ziegler, C., J. Thema, B. Best, F. Wiese, J. Lage, A. Schmidt, E. Toulouse, and S. Stagl. 2021. “Enough? The Role of Sufficiency in European Energy and Climate Plans.” Energy Policy 157: 112483. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2021.112483.