Abstract

Waste management is one of the most important environmental and public health issues of the 21st century. In Indonesia, the trend in waste management has changed from a government-led to a community-driven social activity, which significantly manages household-solid waste and positively affects the environment. Additionally, waste management supports the circular economy (CE), a topic that many scholars and policymakers are now debating. Waste sadaqah (WS) is a community-based waste-management movement that seeks to achieve economic empowerment through social action. This Brief Report describes how WS contributes to waste handling and how the community engages in social actions that affect the environment and advance CE practices. The focus of our data collection and analysis was the province of Yogyakarta, a well-known region on the Indonesian island of Java. This study reports participant observations and casual discussions with the founders. To capture photographic evidence to support the interview findings, we supplemented the study with a field survey. To highlight WS practices, we applied the perspectives of community theory, social capital, social action, and empowerment theory. We found evidence that this practice is distinct from other modes of community-based waste management.

Introduction

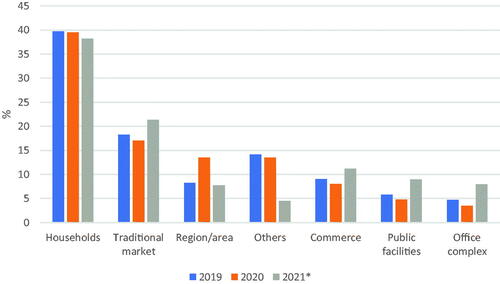

Waste is a major environmental and public health concern in developing countries. For example, approximately 85% of the waste generated in Vietnam is buried without treatment at landfill sites, 80% of which is unhygienic and pollutes the environment (Globenewswire Citation2020). Pakistan generates approximately 49.6 million tons of solid waste annually, an amount that has been increasing by more than 2.4% every year, creating serious environmental problems (ITA Citation2022). Meanwhile, approximately 27.8 million tons of solid waste are produced in Thailand, which translates into a daily volume of 1.13 kilograms (kg) per person, of which 12–13% comprises plastics (Simachaya Citation2020). Bangladesh has been facing rapid growth in waste generation, and in the last three decades, the country’s waste volume has doubled every 15 years. An average of 55% of solid waste remains uncollected in the country’s urban areas, with a variation in collection efficiency from 37 to 77%. In Bangladesh, discarded materials are not formally segregated, contributing to the accumulation of waste, and creating pressure on landfills that are not managed sustainably (Islam Citation2021). The Ministry of Environment and Forestry (KLHK), the government agency in charge of waste management in Indonesia, reported that 67.8 million tons of rubbish were produced nationally in the country in 2020. This implies that 270 million individuals produce approximately 185,700 tons of daily waste, an amount equal to roughly 0.68 kg of waste per person every day. Compared with earlier years, this is a significant increase. In 2018, the country’s population of 267 million generated 64 million tons of waste nationwide, with households accounting for 37–39% of all national waste sources, making them the largest contributor ().

Figure 1. Sources of waste in Indonesia, 2019–2021. Note: Data for 2021 are provisional. Source: Ministry of Environment and Forestry, Republic of Indonesia, 2021.

These nations currently have a waste problem that pollutes both land and water—in this case, the oceans, lakes, rivers, and also air. According to Ferronato and Torreta (Citation2019), the primary and most readily discernible environmental impacts are visual effects, air contamination, odors, greenhouse-gas emissions, disease vectors, and surface water and groundwater pollution.

Why has waste become a burden for many local authorities in developing countries? We examined a portion of the relevant literature and concluded that the problem exists within the domain of public governance and management, as well as in the political systems and their interrelationships. In the public sphere, the issue pertains to public awareness (Hasan Citation2004; A. Islam et al. Citation2021), which is also tied to educational level and employment status (Wang et al. Citation2020). Generally speaking, the higher a person’s level of education, the greater their pro-environmental awareness.

The waste issue also relates to public and private sector interactions and the level of political support for engagement in the governance context (Bull et al. Citation2010). Moreover, Mmereki, Baldwin, and Li (Citation2016) determined that solid-waste management in developing countries is often ineffective. A lack of coordination among stakeholders, institutional and structural deficiencies, lack of recycling legislation, and ad hoc and uncoordinated measures were identified as the most significant problems.

In Indonesia, it has been a long time since numerous government programs raised public awareness of the importance of the environment. During the era of the New Order that characterized the Suharto presidency from 1966 to 1998, the government rewarded institutions and individuals who cared about and took action on environmental issues through a series of initiatives called “Kalpataru” (the root of the Sanskrit word—kalpavriksha—which means tree of life). These programs aimed to increase awareness, to stimulate opportunities for the development of innovation and creativity, and to encourage community initiatives as a form of recognition and motivation to individuals and community groups engaged in sustainable environmental and forest-management protection. The arrangement was reinforced at the start of the Jokowi administration in 2014 by a dedicated regulation promulgated by the Ministry of Environment and Forestry pertaining to the Kalpataru Award.

Another program initiated in 1986 called Adipura developed reputational incentives for mayors to seek recognition of their cities as “green and clean.” This initiative relies on inspections and public disclosure of results to evaluate city-level waste management and cleanliness (Dethier Citation2017). However, Dethier argued that the program had little effect on waste reduction due to a decline in the prominence of environmental problems on the political agenda.

The legislation for waste management in Indonesia is listed in . Instead of being effective in addressing the waste problem, implementation is often contradictory. These regulations have become a mountain of policy texts without comprehensive follow-up programs to ensure their effective enactment. Similar paradoxes of policy are frequently evinced at the global and national levels (Muheirwe, Kombe, and Kihila Citation2022) and are particularly prevalent at the local governmental level in Indonesia. Therefore, waste-management frameworks in the country should be designed and implemented with a more coherent approach to obtain public support and to maximize policy effectiveness (Bull et al. Citation2010; Wan, Shen, and Choi Citation2018).

Table 1. Indonesian regulations focused on waste management.

Some policies, as outlined in , allow the private sector and the general public to engage in waste management, primarily as an economic or a community-service activity. To this end, in the era of regional autonomy, local administrations are permitted to manage and address the issue of waste in their own areas. This includes the creation of regionally-based regulations to develop and enhance public knowledge.

Accordingly, as described in their anthropological studies (Schelehe and Yulianto Citation2018, Citation2020), waste management has become an integral part of the daily lives of Indonesians. They practice waste self-management, such as burning solid waste in their backyards, which is a part of local and national culture. However, community engagement in waste management has increased over the last 10 years (Dholikah, Trihadiningrum, and Sunaryo Citation2015; Prasetiyo, Kamarudin, and Dewantara Citation2019; Schelehe and Yulianto Citation2020; Amin et al. Citation2021; Kurniawan et al. Citation2021).1

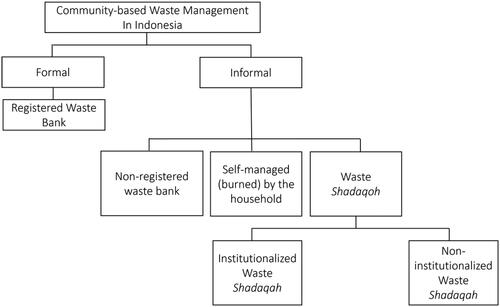

In Indonesia, research has focused on waste banks as distinctive community-based waste-management enterprises. Premised on regulation of the Ministry of Environment and Forestry No. 14/2021, the waste bank (bank sampah in Indonesian Bahasa) is a facility that is established and managed by the community, businesses, and/or local government with the purpose of managing waste based on the 3R principles (reduce, reuse, and recycle) as well as educating people, changing their behavior toward waste management, and implementing a circular economy (CE). Waste banks are superior alternatives to conventional waste management and contribute to societal and economic benefits (Faradina, Maryono, and Warsito Citation2020). In the social realm, they facilitate environmental awareness education, waste recycling, waste-bank management, ecotourism development, and creation of instructional tools for young students (Indrianti Citation2016; Prasetiyo, Kamarudin, and Dewantara Citation2019). Even today, the presence of waste banks results from a more collaborative approach (Fatwamati et al. Citation2022). Following studies by Schelehe and Yulianto (Citation2018, Citation2020), we developed a classification pattern for community-based waste management in Indonesia ().

The Ministry of Environment and Forestry has issued two regulations governing the existence of waste banks () and the government recognizes waste banks as community-based waste-management activities. Waste banks are regarded as an institutional tool and the government encourages the relevant institutions to be supported by administrators, organizational structures, and work programs. In addition, waste banks can register their facilities with the local government and the formal rules take effect as soon as this is achieved. The waste bank benefits from this registration because the local government provides complimentary scales, a waste-bank book to record transactions, and promotional banners.

Nevertheless, numerous waste banks operate autonomously by exploiting the economic benefits of their activities, namely the sale of recyclable materials to waste entrepreneurs (Indrosaptono and Syahbana Citation2017). By contrast, waste management by the community is conducted individually by burning waste (Schelehe and Yulianto Citation2020). However the self-management of waste is incompatible with the five CE principles of reduce, reuse, recycle, recover, and revalue, according to the current trend in modern waste management (Kirchher, Reike, and Hekker Citation2017).

Community-based waste management in Indonesia has expanded to include waste sadaqah (WS), a novel innovation. As it is not registered with the government-regulatory system, but rather is a movement that is more informal and charitable than that of the waste bank (Hasanah et al. Citation2018). An absence of formality, ceremonies, and institutional organization typically characterizes WS. For this Brief Report, we explored how the description and practice of WS contribute to the management of waste in Java and how the community transforms waste into social actions that affect its environment and facilitate CE practices

Although some scholars have studied WS projects, such as Muslim (Citation2015) who discussed the practice and its implementation in Yogyakarta and Endah and Kasjono (Citation2017) who assessed the success of WS practices in Semarang City, few studies link the existence of WS to the challenges of CE. According to Wiesmeth (Citation2021), the CE discourse is still centered on economic integration with the environment and neglects the role of social action as a tool. In this Brief Report, we explain how WS is not only pursuing economically-oriented waste management, but also engendering activities that have a social dimension. Furthermore, we elaborate the results of empirical studies related to waste management in Indonesia, followed by a descriptive overview of the practice of WS, with the support of photo documentation. In the next section, we describe the differences between WS, waste banks, and other community-based waste-management systems in the CE context. We conclude this Brief Report with several recommendations from scientific and policy-making perspectives.

Theoretical dimensions

The formation of community-based movements directed toward the environment have become a global trend over the last 50 years. In studying these activities, the term community has been employed in many different ways. One popular approach has relied on the work of sociologist Joseph Gusfield (Citation1975) which distinguished two distinct community groups: territorial and geographical (neighborhood, town, and city) (Tu Citation2019). Based on these distinctions, Hayden Roberts (Citation1979) contended that the community is “a collection of people who have become aware of some problems or some broad goal, who have gone through a process of learning about themselves and their environment, and have formulated a group objective”—an appropriate explanation of the existence of communities against waste around the world.

How can the community be effective in mobilizing society? Communities motivate and encourage people to develop themselves through self-initiative and with minimum assistance from the government. They enable processes in which people, in partnership with those able to assist them, are increasingly encouraged to assume responsibility and plan, manage, control, and assess their collective actions (Mezirow Citation1997). Recent evidence suggests that civil society actors can create platforms for environmental justice and resistance to overcome inequitable and unsustainable development practices (Suharko Citation2020).

This leads us to assess the importance of community empowerment and scholars have provided several definitions. For instance, McClelland (Citation1975) stated that empowerment is a change process, but to gain power organizers need to know themselves and their surroundings and be able to identify and collaborate with others. Empowerment is the process of expanding the ability of individuals and groups to make choices and to change toward a common goal. Immanuel Wallerstein (Citation1992) translated empowerment as a social action process that promotes the participation of people, organizations, and communities toward enhancing individual and community control, political efficiency, improved quality of life, and social justice. Peterson and Reid (Citation2003) suggested a few steps and processes for implementing an empowerment approach in community development which to be successful needs to be followed sequentially: (1) building hope, (2) fostering widespread participation, (3) forging relationships, (4) creating visions, (5) establishing a work plan, (6) finding resources, (7) creating success, (8) developing community capacity, (9) adopting a strategic plan, and (10) aiming toward sustainability.

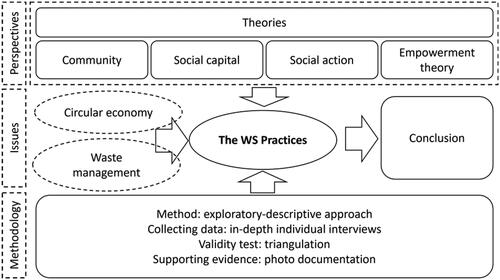

Another explanation relies on neighborhood-based forms of social capital. Political scientist Robert Putnam (Citation1993) defined social capital as a picture of social life that allows participants to act together more effectively to achieve common goals. Trust, norms, and social networks enable citizens to act together and constitute forms of social capital. This was demonstrated through a notable study by Liao and Xing (Citation2023) in China which found that social capital could change plastic-recycling behavior. The upshot is that more robust social capital can lead to a more positive attitude toward the environment (Onyx, Osburn, and Bullen Citation2004) and can facilitate development of education and engagement strategies to promote environmental responsibility (Miller and Buys Citation2008). Drawing on the aforementioned theoretical perspective, we present a framework for examining the practice of WS ().

Methods

This study is based on empirical evidence from Yogyakarta, a province on Java Island, Indonesia. Based on Creswell (Citation1994), we deployed a descriptive-qualitative approach that involved in-depth individual conversations (lasting two days) with WS initiators in November 2021. The present study reports on a field visit conducted to the Muhammadiyah Central Leadership Tablig Council Office located in the Kasihan District, Bantul Regency, Yogyakarta where we interviewed the initiator of WS and who served as the key informant. Furthermore, the interview process involved several young people who had volunteered for WS. In order to ensure accurate documentation of the interview, a mobile phone was used to record the conversation. Subsequently, the interview results were transcribed into a script for further analysis.

We combined this methodology with a field survey to obtain photographic documentation that supported the interview results and was intended to contribute to a triangulation process to assess the validity of the information that we collected (Carter et al. Citation2014). The photographic documentation was obtained to provide a visual record of WS activities and infrastructure, including storage warehouses and the involvement of young people in the waste-sorting process as described in the next section.

Results

We initially focused our research on waste banks and unexpectedly discovered the concept of WS (Schelehe and Yulianto Citation2020; Wijayanti and Suryani Citation2015; Nilan and Wibawanto Citation2015). The proposal for this work focused on exploring policies and indicators of sustainable waste-bank governance in Muhammadiyah, Indonesia’s very large religious and social organization (Fuad Citation2004; Barton Citation2014). We selected Muhammadiyah because it has been extremely diligent in bringing environmental issues to the fore over the last 10 years, especially climate change, and also advocates for government action on environmental issues. According to Ikhwanudin (Citation2020), there has been a notable shift in the organization’s perspective toward the environment. Initially, the organization focused on academic promotion, as illustrated in “Environmental Theology” (Asaad Citation2011), which presents an Islamic perspective on environmental discourse. However, the organization has now moved toward advocating for environmental issues, reflecting the current circumstances that necessitate significant efforts toward developing a practical direction for the environmental awareness movement.

We became familiar with the notion of WS while interviewing one of the heads of the Environment Council, a department that handles environmental issues in Muhammadiyah. The specific term WS was introduced in 2011 by the Council and Ananto Isworo followed this up with more specific action. In 2013, Isworo was the first person to promote environmental issues, particularly waste management, across the community in Brajan Village, Bantul (a district to the north of Yogyakarta City). In March 2020, he was invited by the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) to the Global Forum on Environment, Gender Mainstreaming, and Empowering Women for Environmental Sustainability held in Paris.

History of WS as part of community empowerment

The WS movement initially gained momentum during the fast-breaking event of Ramadan in 2013 that was attended by a large number of local residents of Brajan Village.2 The ceremonial meal was held in a mosque called the Masjid Al Muharram that led to the generation of a sizable amount of solid waste from rice boxes and snack packs. Isworo then invited the attendees to collect the leftover packaging and dispose of it in an available sack for donation.

Since local residents were aware that sadaqah had previously been limited to monetary donations, they quickly protested the announcement, particularly on the basis of their budgetary constraints. However, after a few weeks, Isworo demonstrated that properly managed waste could be profitable. The proceeds from the sale of the waste collected at the mosque were then presented to the community. Local residents were amazed by the profits from the waste, and began to realize that their discarded materials had economic value. These findings led us to conclude that religious predispositions can affect environmental awareness. Isworo also addressed the topic of economic incentives in a nuanced manner and the resultant economic benefits raised the consciousness of this mostly lower income community. As a result of the realization that waste may have financial advantages, they were inspired to become more involved.

Local residents were also motivated, from a religious standpoint, by the rewards that they gained from their charitable deeds. In Islam, a tangible or intangible asset issued by a Muslim or commercial entity outside of zakat (tithing) for the benefit of society is referred to as sadaqah. According to Islamic principles, Muslims believe that the material or immaterial items that they donate will atone for their sins and bring them rewards from Allah. The local residents soon realized that sadaqah was the genuine preaching of a Muslim to other people, without being constrained by time or finances. Sadaqah encompasses all acts of charity and good deeds and is not limited to issuing or donating tangible objects. In this instance, collecting waste is construed as kindness because the material damages the environment. As stated in Sura Ar-Rum 41–42, we are prohibited from destroying nature at whim to indulge in self-lust and preventing positive experiences for subsequent generations.

Therefore, the main principles of WS operations comprise Islamic practices of ta’awun (giving aid to each other) and takaful (cooperating with each other). The value of human pursuits is, as the initiator statement elaborates, “to work and to give in the congregation so that everyone has the right to help and has the right to participate with all their abilities.” In addition to these values, the WS movement also draws on Islamic values regarding the importance of caring for the environment. Under Islamic law, every Muslim is obliged to preserve the environment, utilize useful goods for only the requisite benefit, and avoid israf (excessive behavior) and tabdzir (various acts of wasting materials that can still be used). In Islamic preachings, protecting and preserving the environment is tantamount to sustaining generations of human descendants on Earth. In the language of sustainability, current environmental damage affects future generations. Thus, those values lead local residents to believe that their performance is a good reward in Allah’s ibadah (“notebook”).

The WS concepts and the basis of religious motivation

It was easy for WS founders to motivate Yogyakartans because WS originated in a mosque. For Muslims, the mosque is highly significant since it serves as an assembling space for prayer and social interaction (Hidayat Citation2015) and they frequently use mosques as gathering sites for communal events. Every Muslim is bound by Islamic law and associated societal norms serve as the foundation for the development of social activities (Tuomela Citation1984). Congregation improves their ability to communicate with one another and can inspire them to join the WS movement. Our findings support other studies that claim that mosques play a vital role in enhancing Muslims’ external integration, whether in ancient history or the present (Kamil and Darajat Citation2019). Mosques also serve as places where religious beliefs can be integrated into daily life (Tugal Citation2009), and even provide a platform for economic activity (Ch Citation2016). Seen through the lens of contemporary social theory, mosques are the foundation of social capital (Moqaddam and Mohammadi Citation2016).

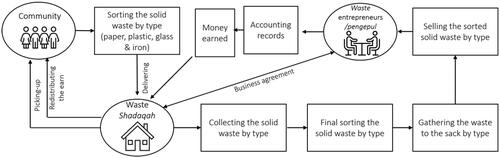

Relevant to this discussion is the work of ecotheologian Mawil Izzi Dien (Citation1997) who discussed the Islamic paradigm of the environment. Although Dien (Citation1997) concludes that Islam has many difficulties in practice because of misunderstandings, misinterpretations, and misappropriations, our evidence shows that Islamic values are very congenial for real-world practice. By implementing these ideas, the movement can encourage people to take a more active personal interest in the management of household waste (Vitria Citation2015). Our reference here to WS also enriches previous studies, such as the work of Afroz, Hanaki, and Tuddin (Citation2010) which focused on Bangladesh. Prior research pertaining to household waste has raised doubts about community involvement in waste management (Odufuwa et al. Citation2012) and has identified low levels of motivation among community members to engage more extensively in such activities (Ying, Qinghua, and Haight Citation2007). We also found that the movement encourages youth to voluntarily participate in sorting the waste delivered by community members (). This distinguishes the WS movement from waste banks and other community-based waste management. A detailed description of these differences is displayed in .

Table 2. The distinguished motives for community-based waste management.

Waste sadaqah as a form of circular economy

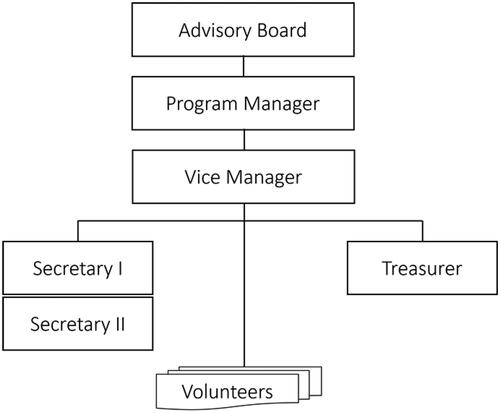

In terms of organizational management, the leaders of the WS movement have designed an optimal organizational structure () and series of action plans that includes offices and waste-storage warehouses () as well as social media accounts to disseminate information about its activities.3 In addition to having an organizational structure, the leadership has established standard operating procedures for WS management ().

There are additionally indications that the WS movement is developing strategies that are consistent with sustainable practices of CE which is a regenerative system that reduces the use of resources, the production of waste and emissions, and the utilization of energy by shortening the cycles of energy and materials. For environmental sustainability, this model focuses on making the most effective use of materials by recycling and/or reusing products (Wiesmeth Citation2021). CE is a framework that aims to sustainably combine economic growth and environmental well-being (Murray, Skene, and Haynes Citation2017). In certain situations, WS employs the 5Rs which serve as the backbone of waste management in CE standards (). Because the Islamic paradigm encourages healthy business and economic activities that are in line with maqasid sharia (the purpose of Islamic canonical law) there are opportunities to attain societal benefit with minimum harm (Khateeb, Jumat, and Khamis Citation2021).

In practical terms, the waste that is sorted according to type is sold to collectors (waste entrepreneurs). Each type of waste is priced, with the highest-priced articles being electronics. Detailed information on the waste prices by type is reported in . As a result of transacting waste, monetary value was earned, which reached a monthly total of 6,000,000 Indonesian rupiah (US$390). This money was then redistributed to poor people and older women or given away as school supplies in the village. The proceeds affected the local economy in the short term as well as the surrounding area by increasing capacity of people to meet their daily needs. In addition, through the WS fund, the movement provides educational scholarships for children in the village and health and basic food assistance to those in need (). Furthermore, the movement offers operational assistance to religious schools in the vicinity. summarizes information on the compensation programs for the poor in the village.

Table 3. Waste prices by type.

Table 4. Compensation program for the poor.

Compared with other empowerment movements, WS is an Islam-based approach to empower poor and lower income communities. As noted by Yunus et al. (Citation2019), “The WS engages in interventions in these underprivileged communities by promoting environmental awareness. This strategy affects the environment and the local economy of an underprivileged neighbourhood.” The WS movement in Yogyakarta is socially successful and has encouraged communities in other regions to implement similar practices.

Conclusion

While waste management was a governmental concern during Indonesia’s New Order, current national regulations promote a high level of public involvement. As a result, several innovations in local waste management such as waste banks have been developed and are regarded as successful examples of moving toward a CE. Furthermore, waste banks are well known and they are increasingly used in community-based waste management, both as a tool for environmental improvement and as a way to raise public environmental awareness through education.

In addition to waste banks, the Yogyakarta community is engaging in other charitable organizations. This movement is associated with Muhammadiyah, a well-known social and religious movement in Indonesia, that calls its activities waste sadaqah. Organizers have successfully mobilized public engagement and invoked public participation in the campaign, success that is attributable to its being mosque-based and supported by Islamic values. Respecting the values of ta’awun and takaful is the foundation of WS’s guiding philosophy. The characteristics of WS that deal with the problem of waste prioritize the social aspect of generating financial benefits, contrary to the operational procedures for waste banks. The WS approach seeks to address the waste issue through social programs and by benefiting underprivileged communities. Because local residents believe that their actions have religious significance, the activities have expanded into a social movement.

WS practices focus on environmental issues through social movement mobilization. Regarding environmental concerns, the implementation of WS has made a noteworthy contribution to the operationalization of fundamental principles of CE and effectively stimulated local residents to participate. This communal involvement functions as a supplement to the deficiencies of CE practices that overlook the social dimension which are crucial. The triple bottom lines model seeks to balance the economic, social, and environmental factors. We can conclude that the WS practice contributes to the sustainability of a CE.

Our research has resulted in numerous findings. However, the lack of local interviews posed a constraint to our study. The information provided by local residents regarding the effects of the program needs to be further investigated. This offers scope for further research in the field and our study can serve as a foundation for academics worldwide to investigate how WS is practiced in other countries. Furthermore, for policymakers in Indonesia, the WS strategy has revolutionized and complemented existing community-based waste management practices. Governments worldwide are encouraged to emulate this model and the related social practices for enhanced waste management.

Waste self-management exists not only in Indonesia but also in Europe, including Ireland (Davies Citation2007). It has been reported in Canada (Sholanke and Gutberlet Citation2022), Johannesburg, South Africa (Kubanza Citation2019), and Uganda (Tukahirwa, Mol, and Oosteveer Citation2010).

The WS movement is an inorganic waste-collection program that is based in mosques and the waste is intended as shadaqah to be further sorted and sold with the proceeds being used for social activities such as education, basic food, health compensation, teaching of the Quran.

For instance, WS’s Twitter handle is @shadaqahsampah.

Notes

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the support from the Muhammadiyah Higher Education Research and Development Council through the #Batch5 Research Scheme in 2021. We would also like to express our gratitude to Muhammadiyah Central Leadership in Yogyakarta’s Environment Department and WS founder Ananto Isworo for agreeing to the interviews.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Afroz, R., K. Hanaki, and R. Tuddin. 2010. “The Role of Socio-economic Factors on Household Waste Generation: A Study in a Waste Management Program in Dhaka City, Bangladesh.” Research Journal of Applied Sciences 5 (3): 1–12. doi:10.3923/rjasci.2010.183.190.

- Amin, M., L. Adrianto, T. Kusumastanto, and Z. Imran. 2021. “Community Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices towards Environmental Conservation: Assessing Influencing Factors in Jor Bay Lombok, Indonesia.” Marine Policy 129: 104521. doi:10.1016/j.marpol.2021.104521.

- Asaad, I. 2011. Teologi Lingkungan (Etika Pengelolaan Lingkungan Dalam Perspektif Islam) (Environmental Theology (Ethics of Environmental Management in Islamic Perspective)). Jakarta: Deputy for Environmental Communication and Community Empowerment, Ministry of Enviroment, and Muhammadiyah Central Leadership Environmental Council. https://uho.ac.id/prodi/lingkungan/wp-content/uploads/sites/41/2019/01/Teologi-Lingkungan.pdf.

- Barton, G. 2014. “The Gülen Movement, Muhammadiyah and Nahdlatul Ulama: Progressive Islamic Thought, Religious Philanthropy and Civil Society in Turkey and Indonesia.” Islam and Christian–Muslim Relations 25 (3): 287–301. doi:10.1080/09596410.2014.916124.

- Bull, R., J. Petts, and J. Evans. 2010. “The Importance of Context for Effective Public Engagement: Learning from the Governance of Waste.” Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 53 (8): 991–1009. doi:10.1080/09640568.2010.495503.

- Carter, N., D. Lukosius, A. DiCenso, J. Blythe, and A. Neville. 2014. “The Use of Triangulation in Qualitative Research.” Oncology Nursing Forum 41 (5): 545–547. doi:10.1188/14.ONF.545-547.

- Ch, M. 2016. “Revitalization of Mosque Role and Function through Development of ‘Posdaya’ in the View of Structuration Theory.” Research on Humanities and Social Sciences 6: 43–51.

- Creswell, J. 1994. Research Design Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches. London: Sage.

- Davies, A. 2007. “A Waste Opportunity? Civil Society and Waste Management in Ireland.” Environmental Politics 16 (1): 52–72. doi:10.1080/09644010601073564.

- Dethier, J. 2017. “Trash, Cities, and Politics: Urban Environmental Problems in Indonesia.” Indonesia 103 (1): 73–90. doi:10.5728/indonesia.103.0073.

- Dholikah, Y., Y. Trihadiningrum, and S. Sunaryo. 2015. “Community Participation in Household Solid Waste Reduction in Surabaya, Indonesia.” Resources, Conservation and Recycling 102: 153–162. doi:10.1016/j.resconrec.2015.06.013.

- Dien, M. 1997. “Islam and Environment: Theory and Practice.” Journal of Beliefs & Values 18 (1): 47–57. doi:10.1080/1361767970180106.

- Endah, D., and H. Kasjono. 2017. “Faktor-Faktor Keberhasilan Implementasi Sedekah Sampah Di RW 1 Kelurahan Peterongan, Kota Semarang (Factors for the Success of Implementation of Garbage Alms in RW1 Peterongan Village, Semarang City).” Sanitasi 9 (1): 51–54. doi:10.29238/sanitasi.v9i1.750.

- Faradina, D., Maryono, and B. Warsito. 2020. “The Role of Waste Banks in Reducing Waste in Gunung Kidul Regency.” E3S Web of Conferences 202: 06038. doi:10.1051/e3sconf/202020206038.

- Fatwamati, N., M. Haerana, and R. Niswaty Abdilah. 2022. “Waste Bank Policy Implementation through Collaborative Approach: Comparative Study – Makassar and Bantaeng, Indonesia.” Sustainability 14 (13): 7974. doi:10.3390/su14137974.

- Ferronato, N., and V. Torreta. 2019. “Waste Mismanagement in Developing Countries: A Review of Global Issues.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16 (6): 1060. doi:10.3390/ijerph16061060.

- Fuad, M. 2004. “Islam, Modernity and Muhammadiyah’s Educational Programme.” Inter-Asia Cultural Studies 5 (3): 400–414. doi:10.1080/1464937042000288697.

- Globenewswire 2020. “Vietnam Waste Management Market (2020–2025).” Globenewswire August 31. https://www.globenewswire.com/news-release/2020/08/31/2085987/0/en/Vietnam-Waste-Management-Market-2020-2025.html

- Gusfield, J. 1975. The Community: A Critical Response. New York: Harper Colophon.

- Hasan, S. 2004. “Public Awareness Is Key to Successful Waste Management.” Journal of Environmental Science and Health, Part A, Toxic/Hazardous Substances & Environmental Engineering 39 (2): 483–492. doi:10.1081/ese-120027539.

- Hasanah, I., Husamah, G. Harventy, and N. Satiti. 2018. “Implementasi Sekolah Sedekah Sampah Untuk Mewujudkan Pengelolaan Sampah Berbasis Filantropi di SMP Muhammadiyah Kota Batu (Implementation of the Alms-Garbage School to Realize Philanthropy-based Waste Management at Muhammadiyah Middle School, Batu City.” International Journal of Community Service Learning 2 (4): 283–290. doi:10.23887/ijcsl.v2i4.14364.

- Hidayat, W. 2015. “Social Capital: Strategy of Takmir of Jogokariyan Mosque on Developing the Worshipers.” International Journal of Nusantara Islam 3 (2): 79–88. doi:10.15575/ijni.v3i2.1415.

- Ikhwanudin, M. 2020. “Muhammadiyah’s Response to Climate Change and Environmental Issues: Based on Tarjih National Conference.” Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research 436: 762–766. doi:10.2991/assehr.k.200529.161.

- Indrosaptono, D., and J. Syahbana. 2017. “Informal Sector Strategy in Urban Inorganic Waste Management toward 3-M Management (Merubah: Changing, Mengurangi: Reducing, Manfaat: Benefit) in Semarang City.” Journal of Architecture and URBANISM 41 (4): 278–287. doi:10.3846/20297955.2017.1411849.

- Indrianti, N. 2016. “Community-based Solid Waste Bank Model for Sustainable Education.” Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences 224: 158–166. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2016.05.431.

- International Trade Administration (ITA). 2022. “Pakistan-country Commercial Guide: Waste Management.” Trade, November 11. https://www.trade.gov/country-commercial-guides/pakistan-waste-management.

- Kamil, S., and Z. Darajat. 2019. “Mosques and Muslim Social Integration: Study of External Integration of the Muslims.” Insaniyat: Journal of Islam and Humanities 4 (1): 37–48. doi:10.15408/insaniyat.v4i1.12119.

- Islam, A., P. Karmakar, M. Hoque, S. Roy, and R. Hasan. 2021. “Appraisal of Public Awareness Regarding Plastic Waste in the Tangail Municipality, Bangladesh.” International Journal of Environmental Studies 78 (6): 900–913. doi:10.1080/00207233.2020.1852776.

- Islam, S. 2021. Urban Waste Management in Bangladesh: An Overview with a Focus on Dhaka. Singapore: 23rd Asia-Europe Foundation Summer University. https://asef.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/1ASEFSU23-Background-Paper_Waste-Management-in- Bangladesh.pdf.

- Khateeb, S., Z. Jumat, and M. Khamis. 2021. “Islamic Perspective on Circular Economy.” In Islamic Finance and Circular Economy, edited by S. Ali and Z. Jumat, 11–25. Singapore: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-981-16-6061-0_2.

- Kirchher, J., D. Reike, and M. Hekker. 2017. “Conceptualizing the Circular Economy: An Analysis of 114 Definitions.” Resources, Conservation and Recycling 127: 221–232. doi:10.1016/j.resconrec.2017.09.005.

- Kubanza, N. 2019. “The Role of Community Participation in Solid Waste Management in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Study of Orlando East, Johannesburg, South Africa.” South African Geographical Journal 103: 1–14. doi:10.1080/03736245.2020.1727772.

- Kurniawan, T., Avtar, R. Singh, W. Xue, M. Othman, G. Hwang Iswanto, A. Albadarin, and A. Kern. 2021. “Reforming MSWM in Sukunan (Yogjakarta, Indonesia): A Case-study of Applying a Zero-waste Approach Based on Circular Economy Paradigm.” Journal of Cleaner Production 284: 124775. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.124775.

- Liao, Y., and Y. Xing. 2023. “Social Capital and Resident’s Plastic Recycling Behaviors in China.” Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 66 (5): 955–976. doi:10.1080/09640568.2021.2007062.

- McClelland, D. 1975. Power: The Inner Experience. New York, NY: Irvington Press.

- Mezirow, J. 1997. “Transformative Learning: Theory to Practice.” New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education 1997 (74): 5–12. doi:10.1002/ace.7401.

- Mmereki, D., A. Baldwin, and B. Li. 2016. “A Comparative Analysis of Solid Waste Management in Developed, Developing and Lesser Developed Countries.” Environmental Technology Reviews 5 (1): 120–141. doi:10.1080/21622515.2016.1259357.

- Miller, E., and L. Buys. 2008. “The Role of Social Capital in Predicting and Promoting ‘Feelings of Responsibility’ for Local Environmental Issues in an Australian Community.” Australasian Journal of Environmental Management 15 (4): 231–240. doi:10.1080/14486563.2008.9725207.

- Moqaddam, S., and M. Mohammadi. 2016. “A Review of the Mosque’s Role in Increasing Social Capital Based on Its Principal Indicators in the Quran and Islamic Narratives.” Social Capital Management 3: 139–162. doi:10.22059/JSCM.2016.58849.

- Muheirwe, F., W. Kombe, and J. Kihila. 2022. “The Paradox of Solid Waste Management: A Regulatory Discourse from Sub-Saharan Africa.” Habitat International 119: 102491. doi:10.1016/j.habitatint.2021.102491.

- Murray, A., K. Skene, and K. Haynes. 2017. “The Circular Economy: An Interdisciplinary Exploration of the Concept and Application in a Global Context.” Journal of Business Ethics 140 (3): 369–380. doi:10.1007/s10551-015-2693-2.

- Muslim, A. 2015. “A Model of Shodaqoh-based Waste Management.” Environmental Management and Sustainable Development 4 (1): 164–179. doi:10.5296/emsd.v4i1.7300.

- Nilan, P., and G. Wibawanto. 2015. “‘Becoming’ an Environmentalist in Indonesia.” Geoforum 62: 61–69. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2015.03.023.

- Odufuwa, B., B. Odufuwa, O. Ediale, and S. Oriola. 2012. “Household Participation in Waste Disposal and Management in Ijebu-Ode, Nigeria.” Journal of Human Ecology 40 (3): 247–254. doi:10.1080/09709274.2012.11906543.

- Onyx, J., L. Osburn, and P. Bullen. 2004. “Response to the Environment: Social Capital and Sustainability.” Australasian Journal of Environmental Management 11 (3): 212–219. doi:10.1080/14486563.2004.10648615.

- Peterson, N., and R. Reid. 2003. “Paths to Psychological Empowerment in an Urban Community: Sense of Community and Citizen Participation in Substance Abuse Prevention Activities.” Journal of Community Psychology 31 (1): 25–38. doi:10.1002/jcop.10034.

- Prasetiyo, W., K. Kamarudin, and J. Dewantara. 2019. “Surabaya Green and Clean: Protecting Urban Environment through Civic Engagement Community.” Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment 29 (8): 997–1014. doi:10.1080/10911359.2019.1642821.

- Putnam, R. 1993. “The Properous Community: Social Capital and Public Life.” The American Prospect 13: 36–42.

- Roberts, H. 1979. Community Development: Learning and Action. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- Schelehe, J., and V. Yulianto. 2018. “Waste, Worldviews and Morality at the South Coast of Java: An Anthropological Approach.” Southeast Asian Studies at the University of Freiburg Occasional Paper 41. https://www.southeastasianstudies.uni-freiburg.de/documents/ocJ.Ncasional-paper/op41.pdf.

- Schelehe, J., and V. Yulianto. 2020. “An Anthropology of Waste: Morality and Social Mobilization in Java.” Indonesia and the Malay World 48 (140): 40–59. doi:10.1080/13639811.2019.1654225.

- Sholanke, D., and J. Gutberlet. 2022. “Call for Participatory Waste Governance: Waste Management with Informal Recyclers in Vancouver.” Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning 24 (1): 94–108. doi:10.1080/1523908X.2021.1956308.

- Simachaya, W. 2020. Solid Waste During COVID-19. Nonthabur: Thailand Environment Institute. https://www.tei.or.th/en/article_detail.php?bid=49.

- Suharko. 2020. “Urban Environmental Justice Movements in Yogyakarta, Indonesia.” Environmental Sociology 6 (3): 231–241. doi:10.1080/23251042.2020.1778263.

- Tu, W. 2019. “Combating Air Pollution through Data Generation and Reinterpretation: Community Air Monitoring in Taiwan.” East Asian Science, Technology and Society 13 (2): 235–255. doi:10.1215/18752160-7267447.

- Tugal, C. 2009. “Transforming Everyday Life: Islamism and Social Movement Theory.” Theory and Society 38: 423–458. doi:10.1007/s11186-009-9091-7.

- Tukahirwa, J., A. Mol, and P. Oosteveer. 2010. “Civil Society Participation in Urban Sanitation and Solid Waste Management in Uganda.” Local Environment 15 (1): 1–14. doi:10.1080/13549830903406032.

- Tuomela, R. 1984. A Theory of Social Action. Boston, MA: D. Reidel. doi:10.1007/978-94-009-6317-7.

- Vitria, W. 2015. “The Role of Civil Society in Encouraging Community Participation (Case Study: Brajan Village Garbage Alms Movement, Bantul).” PhD thesis, Gadjah Mada University.

- Wallerstein, N. 1992. “Powerlesness, Empowerment and Health: Implications for Health Promotion Programs.” American Journal of Health Promotion 6 (3): 197–205. doi:10.4278/0890-1171-6.3.197.

- Wan, C., G. Shen, and S. Choi. 2018. “Differential Public Support for Waste Management Policy: The Case of Hong Kong.” Journal of Cleaner Production 175: 477–488. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.12.060.

- Wang, H., X. Liu, N. Wang, K. Zhang, F. Wang, S. Zhang, R. Wang, P. Zheng, and M. Matsushita. 2020. “Key Factors Influencing Public Awareness of Household Solid Waste Recycling in Urban Areas of China: A Case Study.” Resources, Conservation and Recycling 158: 104813.doi:10.1016/j.resconrec.2020.104813.

- Wiesmeth, H. 2021. Implementing the Circular Economy for Sustainable Development. Amsterdam: Elsevier. doi:10.1016/C2019-0-04150-7.

- Wijayanti, D., and S. Suryani. 2015. “Waste Bank as Community-based Environmental Governance: A Lesson Learned from Surabaya.” Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences 184: 171–179. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.05.077.

- Ying, Q., Z. Qinghua, and M. Haight. 2007. “Empirical Study on Factors Influencing Residents’ Behavior of Separating Household Wastes at Source.” Chinese Journal of Population Resources and Environment 5 (2): 20–27. doi:10.1080/10042857.2007.10677497.

- Yunus, R., Y. Dekrita, M. Yamin, and A. Citta. 2019. “Poverty Reduction Model through Empowerment People’s Economy According to Islamic Perspectives (Study on Islamic Village in Sikka-Flores District).” Advances in Economics, Business and Management Research 92: 127–136. doi:10.2991/icame-18.2019.14.