Abstract

Fashion’s unsustainability needs transformative action, as policymakers, business, and wider society all agree. The lack of a clear definition of sustainable fashion is often given as a major reason behind fashion’s increasing unsustainability. Taking a social-ecological system perspective, augmented by a feminist critical realist understanding of being (ontology) and knowledge of being (epistemology), I examine the past two decades of academic literature mentioning the concept “sustainable fashion.” I find a definition is indeed lacking in various academic discourses and approaches related to sustainable fashion. This lack is problematic because it means the fashion industry can talk preposterously without making useful progress on decreasing its negative impacts on people and the living planet. However, the ever-changing patterns and contexts of fashion would soon outdate a single fixed definition. What is presented as a two-sided problem – whether or not to define sustainable fashion – is instead a problématique. Sustainable fashion is better understood as an unsolvable predicament in a complex dynamic intertwined social-ecological system. While no solution exists, there are appropriate reflexive responses. These start by using a critical systems approach that includes fashion’s social (non-material) and ecological (material) aspects. A social-ecological system approach prevents businesses from exploiting the slipperiness of inconsistent definitions, aids policymaking by providing context and structure for the many contributory concepts (e.g., slow, green, or circular fashion), and fosters vital transdisciplinary research on sustainable fashion.

Introduction

The fashion industry indisputably causes undesired impacts on people and the living planet. The recent exponential growth of the industry, now worth US$200 billion (Gaubys Citation2023), is expected to continue (McKinsey & Company and Business of Fashion Citation2022), with fast fashion –“low-cost fashion textile apparel frequently updated in large retail chains” (Entwistle Citation2000; Zamani Citation2014) – as the most rapidly growing part of the fashion industry. Fast-fashion accounts for most of the approximately 60 million tons of clothing globally consumed each year (House of Commons Citation2019) and one in eight workers estimated to be employed in the international fashion industry (Common Objective Citation2018). The fashion industry’s vast size means it contributes up to 10% of carbon emissions (Niinimäki et al. Citation2020; Watson, Eder-Hansen, and Tärneberg Citation2017) and 20% of industrial water pollution (Rathinamoorthy Citation2019). An estimated 35% of all primary source microplastics in the marine environment are from synthetic clothing (Henry, Laitala, and Grimstad Klepp Citation2018) and over 15,000 chemicals have been identified in textile clothing (Niinimäki et al. Citation2020; Swedish Chemicals Agency Citation2014). In addition, the fashion industry is repeatedly scrutinized for poor working conditions, child labor, and modern-day slavery (Hart Citation2016; McGuire Citation2021; Powell Citation2014; Talbot Citation2018; Walk Free Foundation Citation2010).

As these negative impacts become more perceptible and widely known, sustainable fashion is increasingly receiving attention from policymakers and fashion stakeholders. The United Nations Environment Programme established an umbrella framework for sustainability and circularity in the textile-value chain overseeing multiple initiatives (UNEP Citation2021), where circular economy centers on the “decoupling of natural resource extraction and use from economic output, having increased resource efficiency as a major outcome” (Corvellec, Stowell, and Johansson Citation2022). The European Union has developed a strategy for actions to make the “textiles ecosystem” fit for the circular economy (European Commission Citation2022a), and as a national example, the Swedish government has a strategy for textiles and fashion to become part of the circular economy (Government Offices of Sweden Citation2018). Increasingly fashion businesses are publishing sustainability reports and engaging in initiatives to reduce their impacts (McKinsey & Company and Business of Fashion Citation2022; Palm, Cornell, and Häyhä Citation2021). Accordingly, academic publications relating to the (un)sustainability of fashion are increasing.

Despite this fast-growing interest, the negative impacts of fashion are projected to rise (McKinsey & Company and Business of Fashion Citation2022). One reason put forward for the absence of desired results, especially by actors within the fashion industry, is the lack of a clear definition of “sustainable fashion.” Mehar (Citation2021) argues that “[t]he most significant loophole in sustainability is its lack of a clear, quantifiable definition.” CNN (Citation2019) notes that “The term ‘sustainability,’ therefore, is considered by some industry experts to be so broad as to be problematic,” and a designer interviewed in the same article says, “there isn’t actually a defined way to determine what is sustainable fashion and what isn’t sustainable fashion.” A leading fashion-media company states that “sustainability is fashion’s word of the moment, encompassing any effort by a brand to operate more responsibly. Its definition, therefore, is hazy. Often, brands don’t need to use the word ‘sustainable’ at all to communicate a moral high ground to their customers.” (Fernandez Citation2021). The Financial Times (Bauck Citation2021) finds the concept of sustainable fashion more problematic than useful saying “the word ‘sustainable,’ which has become so diluted from overuse that its meaning is vague at best, ‘regenerative’ is becoming an increasingly popular label for brands looking to position themselves on the cutting edge.” In these discussions, some propose discontinuing use of the concept. The European Commission (2022b) has referred to sustainable fashion being a buzzword, indicating a view of its transience. A high-profile stakeholder organization, the Ellen MacArthur Foundation, has even stopped using the wording “sustainability” and talks instead of a “better” economy (Clancy and Makover Citation2019).

It is remarkable that despite a consensus that the unsustainability of fashion needs to be addressed, there is so much disagreement about the definition of sustainable fashion. Little research has examined academic definitions and perspectives on sustainable fashion. In previous transdisciplinary work, we have argued that fashion “makes complex links between global industry, culture and Earth’s dynamics” (Palm, Cornell, and Häyhä Citation2021), but we found stark gaps between social and biophysical conceptualizations of fashion (Palm and Cornell Citation2022). Importantly, we discovered that academic studies and “real-world” actions aiming to reduce the industry’s impacts are more likely to have a desired outcome if they use a social-ecological system approach recognizing these links.

In this Brief Report, I critically review the growing body of scholarly literature discussing the concept sustainable fashion, seeking to understand how the notion is defined in academic studies and how the concept is approached. I use a social-ecological system perspective expanded by a feminist critical realist understanding of being (ontology) and knowledge of being (epistemology) to examine and critique the various academic discourses and conceptualizations related to sustainable fashion. My aim is to identify a navigable route through academic definitions of sustainable fashion to investigate the accuracy of the claim that the lack of a clear definition lies behind the industry’s continuing unsustainability and to reflectively explore the role of academia in informing a transition toward sustainability. My starting point is the statement in the Brundtland Report (WCED Citation1987) that the aim of sustainable development is to promote “harmony among human beings and harmony between nature and humans.” The issue of whether the globalized fashion industry can ever, under any circumstances, be or become sustainable calls for data, approaches, analysis, and findings well beyond the scope of this study.

Four research questions structure this analysis. The first two deal with concept clarity and meaning: Do the articles define sustainable fashion? And if so, what understandings do they display of the concept sustainability? Exploring views on the notion of sustainability is important because knowing what our concepts entail affects how we approach the world (Ramsey Citation2015). The next two questions deal with context: How do the articles using the concept of sustainable fashion relate to fashion as a social-ecological system? How do they relate to evolving policy and business discourses regarding sustainable fashion? These reflections affect the potential use and usefulness of academic studies for decision making.

Seeing fashion from a feminist critical-realist social-ecological system perspective

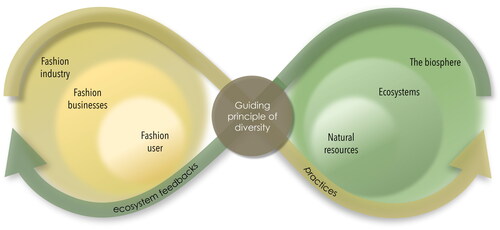

A social-ecological approach regards humans and nature as inseparable (Folke et al. Citation2016), meaning that all aspects significant to societies (for example, economy and equality) shape, depend upon, and coevolve with living ecosystems. Approaching fashion in terms of social-ecological systems brings the social (non-material) and ecological (materialFootnote1) aspects into a shared perspective where they are intertwined. Good and bad social practices and, desired and undesired ecosystem feedbacks, continuously flow into each other ().

Figure 1. A feminist critical realist social-ecological systems approach to fashion as system. Note: This figure is based on a conceptual framework of linked social–ecological systems first introduced by Berkes, Colding, and Folke (Citation2002). It illustrates the connections between ecosystems, knowledge (as seen in how we manage things), and institutions and indicates how to effectively deal with these connections to enhance resilience and adaptability.

I also take a critical realist philosophical approach. Critical realism understands reality as an open stratified system (Bhaskar Citation2008), distinguishing domains of the real (what is possible), the actual (what events take place), and the empirical (what is experienced). Experiences (the perceptions of things by agents), events (the things that are being perceived), and causal mechanisms (the things that tend to produce the events) are all part of reality (Bhaskar Citation2008). All that is, is real, irreducible to its generated patterns of actual and empirical events. In the context of sustainable fashion this means that actions must understand all material and non-material aspects as intertwined “all the way through” the domains of a stratified reality. Reality is much more than what is observed, experienced – and quantified. My view of fashion as a stratified intertwined social-ecological system is represented in . Applying critical realism as metatheory helps to see social-ecological systems not only as structures of materially connected components, but as real systems where emergence of experiences and events is possible. This in turn helps critique and expose assumptions made in academic studies on sustainable fashion.

Social practices influence and are shaped by ecosystem feedbacks that span across scales. A feminist lens brings attention to social diversity, an imperative part of sustainable development.

My approach to sustainability is centered by a feminist perspective emphasizing aspects of diversity related to social practices including power, justice, equality, and the production of knowledge in different contexts (Carey et al. Citation2016; Crenshaw Citation1989) (). Fashion is rooted in social aspects. People’s everyday act of getting dressed is a micro-scale activity imperative for micro-social order (Entwistle Citation2000), shaping how individuals orient themselves to the world. Social aspects, including norms and values, financial status, class, and gender, steer people’s daily choices on what to wear, clearly highlighting the non-material dimensions of the system’s underlying “real” domain. However, fashion is not merely social: the production and life cycle of clothing cannot exist without material “stuff” from nature.

Critical realist metatheory and a feminist lens highlight how a choice to represent something in one way (for example, in quantified material terms) is a choice to not represent it in another way. This combined approach helps break open representations of the system, identify absences and gaps, and look critically at wordings and concepts that may cover up social or ecological dimensions of the system’s behavior. Fashion is thus seen as a complex social-ecological system where the ideational aspects and textile materials of fashion are intertwined, through mechanisms and contexts that have global reach with simultaneous local impacts. Contextualizing academic definitions of sustainable fashion means paying attention to these dimensions, especially where they lead to harms and injustice.

Methodology

Identifying, selecting, and screening documents

In this study, I focus on the concept of sustainable fashion as it is currently the prevailing term used by businesses and policymakers and as such it is the key notion on which the discourse on future fashion with less negative impacts hinges. This Brief Report combines text-topic analysis of academic articles mentioning sustainable fashion with a contextualizing disciplinarity analysis based on the journals where they have been published. There are various other concepts in use that aim to capture fashion with fewer or no negative social and/or ecological impacts, but their definitions are not contested and debated in sustainable business and policy contexts. These concepts include ecofashion (Thomas Citation2008), cradle-to-cradle (Borland and Lindgreen Citation2013), circular fashion (Rathinamoorthy Citation2019), green fashion (Debnath Citation2016), ethical fashion (Orzada and Cobb Citation2011), and organic fashion (Dhange et al. Citation2022), among others. Academic attention has also turned to the concept slow fashion which challenges the ever-faster way fashion is produced and consumed (Clark 2008; Fletcher 2010, Jung and Jin Citation2014; Bain 2016). All these notions are unlikely to collapse into one dominant idea. But since they all point to different aspects of the unsustainability of fashion, increased clarity around the concept of sustainable fashion can facilitate the development of a shared aim and mutual understanding.

I identified articles from the Web of Science (WoS) citation database that is frequently used in bibliometric studies. WoS provides global coverage and spans a broad disciplinary scope. The initial search was for articles regardless of contributory discipline, using sustainable fashion as the search term in title, abstract, and keywords. The timeframe starts in 2008 (the first publication using sustainable fashion) and ends April 13, 2022.

This search returned 455 documents. Because my focus is on international discourses and on the globalized fast-fashion industry, 13 documents were excluded as their body-text languages were Afrikaans, French, German, Japanese, Portuguese, Spanish and Turkish. I excluded 214 off-topic documents for simply referring to something done in a sustainable way, unrelated to fashion. Seven book reviews were excluded as they do not represent the full content of the books and 25 documents were neither available as full-text at Stockholm University Library nor provided after requests to their authors. Half of these were conference proceedings, editorials, and book reviews. The remainder were in WoS research categories “Business and Economics” and “Arts Humanities Other Topics,” the categories containing most publications (see Results), so excluding these articles likely had minimal impact on overall findings.

A total of 241 documents remained for the review and analysis, consisting of 204 articles, 23 proceedings, and 19 reviews/editorial material, distributed over 80 unique journals. The articles spanned 32 of the 250 WoS research areas.Footnote2

Strategy for literature categorization and review

My narrative review approach focused on analyzing key concepts, themes, and theoretical perspectives used in relation to sustainable fashion, giving a topic overview, helpful for developing theoretical models and shaping research agendas (Snyder Citation2019). A previous study (Palm and Cornell 2022) found that fashion is absent in studies of resilience of social-ecological systems, and that sustainable fashion scholars are not working in the influential social-ecological resilience research domain. My assumption was therefore that articles would not entail systems terminology frequently used within this domain (e.g., regimes, complexity, adaptiveness), but instead demarcate the system in other narrative ways. The main focus of the articles, based on reading their abstracts, was thus first categorized as social, environmental, or social-ecological. The category social contained articles highlighting the non-material aspects of fashion. Articles focusing on material textiles and/or biophysical aspects were classified as environmental and articles accounting separately for non-material and material aspects were sorted in both categories. When non-material and material aspects were understood as systemically linked (with or without a resilience perspective), articles were categorized as social-ecological.

I then searched the texts for definitions of the concept sustainable fashion. This search targeted versions of the word “definition,” and other words frequently used when explaining or defining concepts such as “meaning,” “means,” “understood as,” and “is.” The search terms used were “defin*” OR “mean*” OR “underst*” OR “sustainable fashion.” I read the sentences and paragraphs of all the returned hits to identify and extract any clear definition statements.

A full analysis of the semiotics and ontology of sustainability, sustainable, and development is far beyond the scope of this paper. However, an initial investigation is necessary to capture some of the epistemology of sustainability fashion definitions. I searched the articles for references to the internationally agreed Brundtland Report (WCED Citation1987) to understand how their authors interpreted sustainability and cognate concepts like sustainable development.

Results

Sustainable fashion really lacks definition

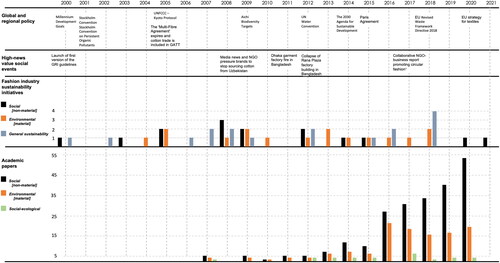

Sustainable fashion is a relatively new and growing research topic (), and 65 of the 241 articles that I examined presented a clear statement of what sustainable fashion is. Definitions were found in 41 of the 127 articles (32%) in the category social/non-material and 10 of the 58 environmental/material articles (17%). A total of 12 articles of 40 categorized as both social and environmental included definitions (30%).

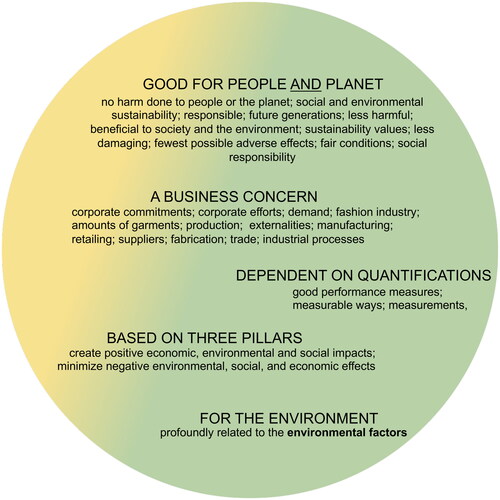

Table 1. Recurring and prominent keywords from 66 identified definitions can be grouped into five themes.

Table 2. Exploring article focus areas and their impact on sustainable fashion definitions.

Twenty-six articles referred directly to the Brundtland Report (WCED Citation1987) and none expressed disagreement with it, indicating broad consensus on what sustainable development is. Fifty-two articles mentioned future generations, a phrase in the widely-used “Brundtland definition” of sustainable development, “meeting the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.”

Although including a definition is a rising trend, no statements were identical, and I found no mutually agreed definition. The definitions cannot be considered to contradict or clash with each other as they mostly focus on parts of the fashion system rather than fashion as a whole system. For instance, definitions with wordings “people” and “social” exclusively refer to workers and working conditions in the global South.

None of the definitions mirrored a system understanding. Based on prominent keywords in the 65 identified “definitions,” five themes surfaced of how sustainable fashion was regarded by the authors ( and ).

Multidisciplinary scholarship rather than sustainability science

shows the distribution of the articles under the five WoS research categories with their top keywords. Close to 40% of the articles were in “Business & Economics,” the fastest growing and largest research area. Three articles are found in the research area “Environmental Sciences & Ecology,” revealing the minimal attention of sustainability scientists so far in studying fashion’s unsustainability. and demonstrate the firm line dividing research on non-material and material aspects of fashion, supporting previous findings (Palm and Cornell 2022) that academic studies of fashion seldom adopt transdisciplinary scope.

Table 3. Distribution of articles across five WoS Research categories and their top keywords.

The most frequent keywords used by all articles are dominated by the keywords of articles in the WoS research areas “Business & Economics” and “Science & Technology.” Studies in the former are primarily concerned with consumer attitudes, corporate responsibilities, and business management and the latter focuses on material aspects of fashion and circular economy. Studies in “Arts & Humanities” primarily related to “non-economic” aspects such as ethics, activism, crafts, creativity, and designer roles. Strikingly, there was a dearth of keywords pointing to environmental impacts on the living planet, even in the Life and Physical Sciences categories.

Sustainable fashion reveals splits rather than intertwined systems

Academic papers, global and regional policy responses to environmental conditions, media reporting, and industry actions are part of the dynamically interacting fashion system. places the articles on a timeline of fashion-sustainability initiatives, policy strategies, and newsworthy events, adapted from Palm, Cornell, and Häyhä (Citation2021). It helps visualize how academic studies both relate to and create meanings of what sustainable fashion is, in relation to real-world discourses.

Figure 3. Timeline of responses to fashion’s undesired impacts. Note: The table contextualizing publication of academic papers with policy responses to global environmental changes, media reporting, and launches of industry-sustainability initiatives. The categories for “Fashion industry sustainability initiatives” are adopted from Palm and Cornell (n.d). The “general sustainability” category is not interchangeable with the articles’ “social-ecological” category.

The timeline shows that in real-world discourses social events tend to get more news attention than environmental, while high-level policy tends to focus on environmental aspects. When the industry takes action regarding social aspects it is following media reporting, as seen after the collapse of the Rana Plaza building in Bangladesh in 2013 (Auke and Simaens Citation2019). Environmental initiatives follow prominent international agreements, such as the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (United Nations Citation2015) and the Paris agreement on climate change (UNCC Citation2015). The emerging case of circularity shows different patterns as business initiatives are set up in anticipation of policy changes. Academic studies tend to mostly follow these real-world discourses, as seen in increased interest in circular fashion and science-based target-setting.

Analysis and reflections

Is the lack of a definition problematic?

Academic articles have long remarked on the lack of a definition of sustainable fashion. The earliest paper by Thomas (Citation2008) calling for science to clarify the terms of sustainable fashion is now a highly-cited publication on terminologies related to what was then called “ecofashion.” Henninger, Alevizou, and Oates (Citation2016) find “current studies lack an academic understanding of what sustainable fashion is from a holistic perspective.” Vijeyarasa and Liu (Citation2022) observe a “significant overlap in definitions but also differences in the depth and rigor of key concepts.” They argue that lack of clarity makes the industry vulnerable to businesses consciously making misleading environmental claims. From a management perspective, Mukendi et al. (Citation2020) finds “the academic literature has been slow to define and conceptualize SF [sustainable fashion]” and (Evans and Peirson-Smith Citation2018) argue for moving toward sustainability is slowed because “it seems that uncertainty reigns about what sustainable fashion actually is.” Busalim, Fox, and Lynn (Citation2022) find that “what is exactly meant by sustainable or slow fashion remains elusive” within media and literature. Researchers continue to find that despite a consensus about sustainability, “ad hoc definition for the fashion-apparel industry is missing and there are different approaches regarding how to undertake and instrumentally define it” (Garcia-Torres et al. Citation2022).

The concept of “definition” itself needs defining if to understand whether this deficiency is problematic. A formal definition consists of the term being defined, its classification, and differentiation. Sustainable fashion has all these components. The fashion industry, policymakers, and consumers/users all agree that the fast-fashion segment is the focus for classification as it is the highest contributor to the industry’s well-characterized negative social and environmental impacts. Sustainability, the differentiating characteristic, is well-defined by policy, as I discuss more fully in the following section. Seen in this way, a general definition is: Sustainable fashion (term) is fashion (class) where the most impactful segment – fast-fashion – operates fully within society’s objectives for sustainable development (differentiating it from other kinds of fashion). An extended definition could deepen the classification, explicitly describing the class and identifying smaller parts; and expand the differentiation, explaining what sustainable fashion is not, clarifying how it affects people and the living planet. What is it, then, that every engaged community expresses the need for?

Ramsey (Citation2015) asks whether a specified definition of “sustainability” would “provide a platform for the intended reform of our society,” concluding that we cannot define our way to clarity, because “what appears to be an issue about clarity in language is really a set of issues about how we view and interact with the world.” From a critical realist perspective, I disagree with Ramsey’s starting point that all things are languaged into being. Ramsey goes as far as stating “for a definition to make sense, the social practices of interpreting have to be in place already” and “definitions absent from social practices” are doomed to fail as a guide toward a desired goal. But sustainability cannot be regarded as merely social when understanding that its intertwinement with Earth’s biophysical processes is real.

The fashion industry has never had the “social practices of interpreting” that Ramsey (Citation2015) argues is needed to make sense of any definition. Since the beginning of industrialization, fashion production has had negative consequences for workers and nature. Aspects regarded as being history – slavery, sweatshops, counterproductive irrigation systems, and polluting emissions – are still present. Features of the fashion system such as trading routes, value chains, and business ownerships, have been empirically the same for several centuries. Despite the system’s centuries-old social dynamics, policymakers, the fashion industry, and a growing share of academic studies focus narrowly on quantifiable material aspects of fashion.

The lack of a definition is problematic if the aim is to quantify the industry’s way to sustainability. One way to understand these outspoken demands for a definition – especially a “science-based” definition – is that it can then be used for establishing targets and criteria for the industry’s claims to do better. There is agreement on the necessity of transparency of the value chain to access information that is “accurate, trusted, timely and useful” for their operations and for the reliability of sustainability claims” (Garcia-Torres et al. Citation2022). Ramsey (Citation2015) argues that the request for a definition is often motivated by a desire to operationalize it “in terms akin to ostension: given the correct criteria, we could point (via measurement) to a property or process and agree that it exemplifies sustainability.” However, as multi-actor platforms set goals and targets to give businesses a shared context for action (Hileman et al. Citation2020), they steer the focus to narrower, more aggregated quantifications of the industry’s material environmental impacts – at the expense of non-quantifiable social impacts. Corporate sustainability reports emphasize relative measures of sustainability progress over absolute numbers, obscuring systemic impacts and the social practices that perpetuate them, despite industry awareness of them.

and shows no definition sees fashion as a system in line with . Instead research communities quantify disparate details such as effects of changing temperature and water regimes on cotton yield and quality (Bange Citation2016), gendered perceptions of sustainable fashion (Gazzola et al. Citation2020), and supply chains of Hijab fashion (Sumarliah, Li, and Wang Citation2020). Articles in the research area “Technology” commonly focus on quantitative assessments of material throughput in ever-increasing detail, suggesting ways to decrease the need for virgin materials (Claxton and Kent Citation2020; Lee et al. Citation2020; Moorhouse and Moorhouse Citation2018; Raebild and Bang Citation2017) as if circular economy were only material. An emerging but still small body of literature is now flagging concerns regarding social sustainability in circularity (Jaeger-Erben et al. Citation2021; Maitre-Ekern Citation2021; Palm, Cornell, and Häyhä Citation2021). Articles in the fast-growing area “Business & Economics” almost exclusively have a quantitative viewpoint. In general, their attention toward social (non-material) aspects focuses on consumer motivations and behavior, to increase economic growth, material value, and business profitability.

When empirical quantifiable evidence is regarded as the only reality that counts, it neglects both what is possible and what actually takes place. It neglects ways consumer culture operates leading to social-ecological harms, and ways biophysical laws govern the links between environmental impacts and global change processes. It ignores the role of high consumption by wealthier societies in the global North, and clothing dependence on resources extracted and produced in colonized or formerly colonized countries in the global South.

The lack of a definition is problematic because it lets the fashion industry talk preposterously without making useful progress to reduce its negative impacts. Businesses use vague wordings such as “better,” “green,” and “more responsible” in their communications, presenting partial versions of sustainability. Gray (Citation2010) observes treating “social responsibility” as a synonym means sustainability “becomes a term that offers no threat to corporate attitudes and activity.” The flipside is mounting greenwashing accusations presenting business risks by threatening to decrease consumer trust (Evans and Peirson-Smith Citation2018; Kim and Oh Citation2020; Thomas Citation2008).

However, the lack of a definition of sustainable fashion is not problematic in changing contexts where a rigid, quantified definition becomes useless or even harmful. Sustainability is a process; therefore, sustainable fashion is neither a noun nor a target to hit. Working toward sustainable fashion calls for expressing things relationally and processually, rather than categorically. The Brundtland Report observed this 35 years ago.

Yet in the end, sustainable development is not a fixed state of harmony, but rather a process of change in which the exploitation of resources, the direction of investments, the orientation of technological development, and institutional change are made consistent with future as well as present needs. We do not pretend that the process is easy or straightforward. Painful choices have to be made (WCED Citation1987).

Is the lack of a systems approach problematic?

The overarching aim of the articles reviewed is moving fashion toward sustainability. While sustainability is debated within academia, it is well-defined by policy. The Brundtland Report’s definition (WCED Citation1987) is at the core of national and international sustainability strategies (European Commission Citation2022; DLUPHC Citation2022; Regeringskansliet (Swedish Government Office) Citation2022; United Nations 2015), influencing sustainable fashion policymaking at all levels (UNFCCC Citation2020; European Commission Citation2022a; Government Offices of Sweden Citation2018).

Fashion’s unsustainability is presented as a problem, but it is much more than a problem, it is a problématique. Fashion is not social and ecological, it is a social-ecological system () (Palm Citation2021; Palm and Cornell 2022). Svendsen (Citation2006) argues all humans today are part of the fashion system, because the size of the fashion industry makes it impossible to be unaware of it. This does not mean all people are sensitive to fashion fads, but it does suggest that their daily choices in dress are part of the negative impacts from the social-ecological fashion system. When science-based initiatives focus on mounting planetary pressures caused by the production of textile (material) clothes, they miss the social aspects and human practices intertwined in the system. When academic studies focus on human practices and at best refer to measured environmental impacts, for example carbon emissions as real, they also fail to engage with the underlying social-ecological intertwinedness of a stratified reality.

Although academic interest in fashion’s unsustainability is increasing, the sustainability science community has ignored fashion as a research topic. Sustainability science emerged as a discipline in the early 2000s, “dealing with the interactions between natural and social systems and with how those interactions affect the challenge of sustainability” (Kates Citation2011). However, Ecology & Society – a flagship journal for research on sustainable social-ecological systems – has not published any articles on fashion. Instead, publications come primarily from the research communities of business, arts, and technology (). Unsurprisingly, since studies focus either on the social or environmental aspects when they define sustainable fashion. Their lack of a system approach leads to lopsided definitions, addressing parts of the system. Not having a systems approach means academia is failing to capture the problématique of fashion: problems caused by the fashion system can neither be reduced to separate causes nor resolved with one or two simple interventions.

How should academia respond to the sustainable fashion problématique?

In contrast to academia, policy and industry initiatives appear more aware of the fashion system’s social-ecological complexity. shows multilateral policies tackling complex unsustainability, and it shows fashion-industry actions to minimize business risks in response to high-impact news and high-level policy requirements. But the steady flow of general sustainability initiatives focuses on promoting “sustainable fashion”; their purpose is not hands-on action to decrease the harms emerging from a social-ecological system problématique.

and reveal research on sustainable fashion is in its infancy, with articles appearing to follow real-world discourses. In cases such as the Rana Plaza incident it is understandable that studies are prompted by an event. But when academics work within narrow disciplines, uncritically follow business-led discourses, and report on assessments rather than explore meanings and ideas, it presents obstacles for these studies to contribute useful knowledge.

Circular fashion is an example. Circular fashion, as part of a circular economic system emphasizing material flows (Kirchherr, Reike, and Hekkert Citation2017), is a trending concept embraced by policymakers and the fashion industry. In Europe, the need for diverse market actors to make sense of green claims is a policy priority (European Commission Citation2020). Business initiatives can be seen to anticipate and influence political decisions on circularity, preempting regulation where possible. Accordingly, the main response to the changing policy context is to standardize environmental footprint methods. This context has led to a rapid rise in academic studies quantifying the ways materials circulate in the value chain. Worryingly, circularity is at times used as synonymous to sustainability, blurring the broad agreement of what sustainability means (WCED Citation1987). Elf, Werner, and Black (Citation2022) state circularity is “now being understood as a major opportunity to achieve sustainability across the fashion industry.” By following fashion-business discourses, academic studies risk supporting the fashion industry’s work to reform itself, as in reshaping the mechanisms of the current system to its own ends, rather than providing knowledge useful for transforming the system.

Returning to Ramsey’s (Citation2015) emphasis on finding shared meaning, transdisciplinary studies must reflect on how choices to represent something in one way (for example, circular fashion’s material-economic way) is a choice to not represent it in another way. The lack of transdisciplinary dialogue may explain why most studies are vague about their underlying assumptions and target audience. There are exemplary exceptions. For example, Peirson-Smith and Craik (Citation2020) use a decolonial perspective for re-imagining futures, making sustainable fashion a way of life for all. Payne (Citation2019) takes a philosophical approach to “fashion futuring,” considering how two apparently dichotomous ideological positions serve to make a future in which “these actions, entwined, will prompt the industry and cultural phenomenon of fashion to evolve.”

Combining critical realist metatheory with a feminist perspective helps uncover aspects often overlooked in system representations. Meanwhile, social-ecological systems approaches prioritize transdisciplinary methods, serving as a framework for fostering productive science-business-policy dialogues aimed at co-developing knowledge, as demonstrated by Schultz et al. (2018). This approach not only helps in understanding business risks but also provides clarity regarding the ramifications of policy decisions.

Conclusion: To define or not to define? There is a better question

My findings show no clear articulation of sustainability in the literature on sustainable fashion. Yet the question of whether or not to define sustainable fashion does not have a simple answer.

On one hand, the lack of a systemic definition is indeed problematic because it means businesses can talk about sustainable fashion without making any sense and advance sustainability claims without taking effective action. Though the concept of sustainable fashion is often mentioned, its meaning is rarely spelled out and the provided definitions are only relevant within a discipline or knowledge community. As policies increasingly target the fashion industry’s undesired impacts, the industry has responded through piecemeal actions and by establishing voluntary business initiatives for “general sustainability.” But the negative impacts have continued to increase in lockstep as the fashion industry has expanded. The articles reviewed here focus on aspects of sustainable fashion, and yet typically make broad conclusions on how to transform the system. This reveals a failure to recognize fashion’s problématique, delineating the epistemic system of study and the ontological system within which action is possible.

On the other hand, the lack of a specified definition is not problematic because the context of sustainable fashion is endlessly changing. A specified definition is potentially counterproductive as it risks being outdated before even being used. It may support the delusion that more precisely quantified material details or a breakthrough technical innovation will solve the problématique of fashion’s unsustainability. Working toward sustainable fashion needs an adaptive, relational approach with continuous revision.

The reality is that the stalled progress toward sustainable fashion cannot be blamed on the lack of a clear definition. It is unlikely that sustainability will ever depend on a single definition. But the harms and injustices of today’s unsustainability are real. To address them, there is no option other than to move toward sustainability, with or without a definition. Yet what is often presented as a problem with a solution is actually a predicament with no solution. The many terms and concepts in use today that are related to sustainable fashion, for example circular, green, and slow fashion, will not collapse into one dominant idea that will trigger the transformation. They are all grappling with aspects of fashion’s unsustainability and reflect sustainability as a multifaceted responsive concept.

Finally, this Brief Report can contribute to future academic studies by showing the need to emphasize diversity and equality and the theoretical benefits of using a critical realist social-ecological system and feminist approach to do so. The inherent pluralism of this perspective promotes shared transdisciplinary understanding of the global fashion system, engaging with diverse peoples and knowledge. The approach fosters creative thinking about sustainable fashions instead of relying on piecemeal empirical evidence. Clarifying how theory and analysis underlay real-world understanding of the global fashion system is important for creative thinking and co-generation of knowledge in transdisciplinary work toward a different fashion system. Sustainability is defined by policy, so rather than a definition of sustainable fashion, this study shows policy and business decisions are more likely to lead to desired outcomes by adopting a social-ecological systems understanding of fashion’s problématique.

Clarifying how theory and analysis underlies real-world understanding of the global fashion system is important for co-generation of knowledge in transdisciplinary work toward a different fashion system. Future studies are needed on theoretical connections, differences, and similarities between concepts such as slow, circular, and sustainable fashion; on credibility of business claims on target-setting and progress toward sustainability; and on policy particularly in relation to the European Union’s Strategy for Sustainable and Circular Textiles (European Commission Citation2022a) which is likely in coming years to influence a range of aspects crucial for European fashion business.

Acknowledgements

This article is the result of ongoing conversations and reflections with Sarah Cornell at Stockholm Resilience Centre, Stockholm University, who was my doctoral supervisor. The author wants to thank her for insightful and constructive comments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes

1 To be clear, as in previous work (Palm Citation2021 and Palm, Cornell, and Häyhä Citation2021), I use the word material in its literal sense as “made of stuff,” not to be confused with the legal and financial senses of the word as “something of significance for decision making.” Following this, I use the wording non-material when referring to things “not made of stuff,” for example social values and norms.

2 For a complete list of Web of Science research areas and categories, visit Clarivate Analytics, https://images.webofknowledge.com/images/help/WOS/hp_subject_category_terms_tasca.html.

References

- Auke, E., and A. Simaens. 2019. “Corporate Responsibility in the Fast Fashion Industry: How Media Pressure Affected Corporate Disclosure Following the Collapse of Rana Plaza.” International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation Management 23 (4): 1–14. doi:10.1504/IJEIM.2019.10021652.

- Bange, M. ed. 2016. Climate Change and Cotton Production in Modern Farming Systems. Boston, MA: CAB International.

- Bauck, W. 2021. “The New Buzzword in Fashion.” Financial Times, April 2. https://www.ft.com/content/71b58bba-e95a-4e0e-85c0-c75717bdfdbc

- Berkes, F., J. Colding, and C. Folke, Eds. 2002. Navigating Social-Ecological Systems: Building Resilience for Complexity and Change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Bhaskar, R. 2008. A Realist Theory of Science. 3rd ed. London: Routledge.

- Borland, H., and A. Lindgreen. 2013. “Sustainability, Epistemology, Ecocentric Business, and Marketing Strategy: Ideology, Reality, and Vision.” Journal of Business Ethics 117 (1): 173–87. doi:10.1007/s10551-012-1519-8.

- Busalim, A., G. Fox, and T. Lynn. 2022. “Consumer Behavior in Sustainable Fashion: A Systematic Literature Review and Future Research Agenda.” International Journal of Consumer Studies 46 (5): 1804–1814. doi:10.1111/ijcs.12794.

- Carey, M., M. Jackson, A. Antonello, and J. Rushing. 2016. “Glaciers, Gender, and Science: A Feminist Glaciology Framework for Global Environmental Change Research.” Progress in Human Geography 40 (6): 770–793. doi:10.1177/0309132515623368.

- Clancy, H., and J. Makover. 2019. “GreenBiz 350 Podcast.” GreenBiz, June 21. https://www.greenbiz.com/article/episode-177-sounding-circularity-19

- Clarivate Analytics 2022. “Web of Science Core Collection Help.” https://images.webofknowledge.com/images/help/WOS/hp_research_areas_easca.html

- Claxton, S., and A. Kent. 2020. “The Management of Sustainable Fashion Design Strategies: An Analysis of the Designer’s Role.” Journal of Cleaner Production 268: 122112. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.122112.

- CNN. 2019. “The Problem with ‘Sustainable Fashion.’” CNN, October 11. https://www.cnn.com/style/article/the-problem-with-sustainable-fashion/index.html

- Common Objective 2018. “Faces and Figures: Who Makes Our Clothes?” Common Objective, May 22. http://www.commonobjective.co/article/faces-and-figures-who-makes-our-clothes

- Corvellec, H., A. Stowell, and N. Johansson. 2022. “Critiques of the Circular Economy.” Journal of Industrial Ecology 26 (2): 421–432. doi:10.1111/jiec.13187.

- Crenshaw, K. 1989. “Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics.” University of Chicago Legal Forum 1: 139–167. https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/uclf/vol1989/iss1/8.

- Debnath, S. 2016. “Unexplored Vegetable Fibre in Green Fashion.” In Green Fashion, edited by S. S. Muthu and M. A. Gardetti, 1–19. Singapore: Springer Singapore.

- Dhange, V. K., S. M. Landage, and G. M. Moog. 2022. “Organic Cotton: Fibre to Fashion.” In Sustainable Approaches in Textiles and Fashion, edited by S. S. Muthu, 275–306. Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore.

- Elf, P., A. Werner, and S. Black. 2022. “Advancing the Circular Economy through Dynamic Capabilities and Extended Customer Engagement: Insights from Small Sustainable Fashion Enterprises in the UK.” Business Strategy and the Environment 31 (6): 2682–2699. doi:10.1002/bse.2999.

- Entwistle, J. 2000. The Fashioned Body: Fashion, Dress, and Modern Social Theory. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- European Commission 2022. “EU Sustainable Development Strategy.” Brussels: European Commission. https://ec.europa.eu/environment/sustainable-development/strategy/index_en.htm

- European Commission 2020. “Initiative on Substantiating Green Claims.” Brussels: European Commission. https://ec.europa.eu/environment/eussd/smgp/initiative_on_green_claims.htm

- European Commission 2022a. “EU Strategy for Sustainable and Circular Textiles.” Brussels: European Commission. https://environment.ec.europa.eu/publications/textiles-strategy_en

- European Commission 2022b. “Sustainability Is the Buzzword When It Comes to Fashion: Our New EU Textiles Strategy Will Help the Sector Become More Sustainable and Circular, with the Green Transition Bringing New Opportunities.” Brussels: European Commission. https://twitter.com/eu_commission/status/1509115295025225729?lang=en

- Evans, S., and A. Peirson-Smith. 2018. “The Sustainability Word Challenge: Exploring Consumer Interpretations of Frequently Used Words to Promote Sustainable Fashion Brand Behaviors and Imagery.” Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management 22 (2): 252–269. doi:10.1108/JFMM-10-2017-0103.

- Fernandez, C. 2021. “The Trouble with ‘Sustainable’ Fashion.” The Business of Fashion, May 7. https://www.businessoffashion.com/articles/marketing-pr/the-trouble-with-sustainable-fashion

- Folke, C., R. Biggs, A. Norström, B. Reyers, and J. Rockström. 2016. “Social-Ecological Resilience and Biosphere-Based Sustainability Science.” Ecology and Society 21 (3): 16. doi:10.5751/ES-08748-210341.

- Garcia-Torres, S., M. Rey-Garcia, J. Saenz, and S. Seuring-Stella. 2022. “Traceability and Transparency for Sustainable Fashion-Apparel Supply Chains.” Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management: 26 (2): 344–364. doi:10.1108/JFMM-07-2020-0125.

- Gaubys, J. 2023. “Apparel Industry Statistics (2014–2027).” Oberlo, January. https://www.oberlo.com/statistics/apparel-industry-statistics

- Gazzola, P., E. Pavione, R. Pezzetti, and D. Grechi. 2020. “Trends in the Fashion Industry. The Perception of Sustainability and Circular Economy: A Gender/Generation Quantitative Approach.” Sustainability 12 (7): 2809. doi:10.3390/su12072809.

- Government Offices of Sweden 2018. “Samverkansplattform För Hållbar Svensk Textil Startar i Borås (Collaboration Platform for Sustainable Swedish Textiles Starts in Borås).” Stockholm: Government Offices of Sweden. https://www.regeringen.se/pressmeddelanden/2018/04/samverkansplattform-for-hallbar-svensk-textil-startar-i-boras

- Department for Levelling Up, Housing, and Communities (DLUPHC). 2022. “National Planning Policy Framework – 2. Achieving Sustainable Development – Guidance,” September 12. London: DLUPHC. https://www.gov.uk/guidance/national-planning-policy-framework/2-achieving-sustainable-development

- Gray, R. 2010. “Is Accounting for Sustainability Actually Accounting for Sustainability…and How Would We Know? An Exploration of Narratives of Organisations and the Planet.” Accounting, Organizations and Society 35 (1): 47–62. doi:10.1016/j.aos.2009.04.006.

- Hart, R. 2016. “Nike and the Sweatshop Debate: A Public Relations Crisis Seeking Resolution in the Principles of Image Repair Theory,” Kent State University, Cleveland, OH. doi:10.13140/RG.2.2.32950.50246.

- Henninger, C., P. Alevizou, and C. Oates. 2016. “What Is Sustainable Fashion?” Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management 20 (4): 400–416. doi:10.1108/JFMM-07-2015-0052.

- Henry, B., K. Laitala, and I. Grimstad Klepp. 2018. “Microplastic Pollution from Textiles: A Literature Review.” Oslo: Consumption Research Norway (SIFO). https://oda.oslomet.no/oda-xmlui/bitstream/handle/20.500.12199/5360/OR1%20-%20Microplastic%20pollution%20from%20textiles%20-%20A%20literature%20review.pdf.

- Hileman, J., I. Kallstenius, T. Häyhä, C. Palm, and S. Cornell. 2020. “Keystone Actors Do Not Act Alone: A Business Ecosystem Perspective on Sustainability in the Global Clothing Industry.” Plos ONE 15 (10): e0241453. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0241453.

- House of Commons 2019. “Fixing Fashion: Clothing Consumption and Sustainability.” Sixteenth Report of Session 2017–19. HC 1952. London: House of Commons. https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201719/cmselect/cmenvaud/1952/report-summary.html.

- Jaeger-Erben, M., C. Jensen, F. Hofmann, and J. Zwiers. 2021. “There Is No Sustainable Circular Economy without a Circular Society.” Resources, Conservation and Recycling 168: 105476. doi:10.1016/j.resconrec.2021.105476.

- Jung, S., and B. Jin. 2014. “A Theoretical Investigation of Slow Fashion: Sustainable Future of the Apparel Industry: A Theoretical Investigation of Slow Fashion.” International Journal of Consumer Studies 38 (5): 510–19. doi:10.1111/ijcs.12127.

- Kates, R. 2011. “What Kind of a Science Is Sustainability Science?” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 108 (49): 19449–19450. doi:10.1073/pnas.1116097108.

- Kim, Y., and K. Wha Oh. 2020. “Which Consumer Associations Can Build a Sustainable Fashion Brand Image? Evidence from Fast Fashion Brands.” Sustainability 12 (5): 1703. doi:10.3390/su12051703.

- Kirchherr, J., D. Reike, and M. Hekkert. 2017. “Conceptualizing the Circular Economy: An Analysis of 114 Definitions.” Resources, Conservation and Recycling 127: 221–232. doi:10.1016/j.resconrec.2017.09.005.

- Lee, E.-J., H. Choi, J. Han, D. Kim, E. Ko, and K. Kim. 2020. “How to ‘Nudge’ Your Consumers toward Sustainable Fashion Consumption: An fMRI Investigation.” Journal of Business Research 117: 642–651. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.09.050.

- Maitre-Ekern, E. 2021. “Re-Thinking Producer Responsibility for a Sustainable Circular Economy from Extended Producer Responsibility to Pre-Market Producer Responsibility.” Journal of Cleaner Production 286: 125454. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.125454.

- McGuire, D. 2021. “‘You Have to Pick’: Cotton and State-Organized Forced Labour in Uzbekistan.” Economic and Industrial Democracy 42 (3): 552–572. doi:10.1177/0143831X18789786.

- McKinsey & Company and Business of Fashion 2022. The State of Fashion 2022. London: McKinsey & Company. https://www.mckinsey.com/∼/media/mckinsey/industries/retail/our%20insights/state%20of%20fashion/2022/the-state-of-fashion-2022.pdf.

- Mehar, M. 2021. “The Deception of Greenwashing in Fast Fashion.” Down to Earth, February 16. https://www.downtoearth.org.in/blog/environment/the-deception-of-greenwashing-in-fast-fashion-75557

- Moorhouse, D., and D. Moorhouse. 2018. “Designing a Sustainable Brand Strategy for the Fashion Industry.” Clothing Cultures 5 (1): 7–18. doi:10.1386/cc.5.1.7_2.

- Mukendi, A., I. Davies, S. Glozer, and P. McDonagh. 2020. “Sustainable Fashion: Current and Future Research Directions.” European Journal of Marketing 54 (11): 2873–2909. doi:10.1108/EJM-02-2019-0132.

- Niinimäki, K., G. Peters, H. Dahlbo, P. Perry, T. Rissanen, and A. Gwilt. 2020. “The Environmental Price of Fast Fashion.” Nature Reviews Earth & Environment 1 (4): 189–200. doi:10.1038/s43017-020-0039-9.

- Orzada, T. B., and K. Cobb. 2011. “Ethical Fashion Project: Partnering with Industry.” International Journal of Fashion Design, Technology and Education 4 (3): 173–85. doi:10.1080/17543266.2011.606233.

- Palm, C. 2021. “Re:Ally Re:Think – Seeking to Understand the Matters of Sustainable Fashion.” Licentiate Thesis., Stockholm University, Stockholm, Sweden. https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1567605/FULLTEXT01.pdf.

- Palm, C., and S. Cornell. 2022. “Making Sense of Fashion: A Critical Social-Ecological Approach.” SSRN, http://ssrn.com/abstract=4043520

- Palm, C., S. Cornell, and T. Häyhä. 2021. “Making Resilient Decisions for Sustainable Circularity of Fashion.” Circular Economy and Sustainability 1 (2): 651–670. doi:10.1007/s43615-021-00040-1.

- Payne, A. 2019. “Fashion Futuring in the Anthropocene: Sustainable Fashion as ‘Taming’ and ‘Rewilding.” Fashion Theory 23 (1): 5–23. doi:10.1080/1362704X.2017.1374097.

- Peirson-Smith, A., and J. Craik. 2020. “Transforming Sustainable Fashion in a Decolonial Context: The Case of Redress in Hong Kong.” Fashion Theory 24 (6): 921–946. doi:10.1080/1362704X.2020.1800985.

- Powell, B. 2014. “Meet the Old Sweatshops.” Independent Review 19 (1): 109–122. https://www.independent.org/pdf/tir/tir_19_01_08_powell.pdf.

- Raebild, U., and A. Bang. 2017. “Rethinking the Fashion Collection as a Design Strategic Tool in a Circular Economy.” The Design Journal 20 (Supp 1): S589–S599. doi:10.1080/14606925.2017.1353007.

- Ramsey, J. 2015. “On Not Defining Sustainability.” Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics 28 (6): 1075–1087. doi:10.1007/s10806-015-9578-3.

- Rathinamoorthy, R. 2019. “Circular Fashion.” In Circular Economy in Textiles and Apparel, edited by S. Muthu, 13–48. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

- Regeringskansliet (Swedish Government Office) 2022. Regeringen Lämnar Första Skrivelsen Om Sveriges Genomförande Av Agenda 2030 till Riksdagen (The Government Submits the First Letter about Sweden’s Implementation of Agenda 2030 to the Riksdag).” Stockholm: Regeringskansliet (Swedish Government Office). https://www.regeringen.se/regeringens-politik/globala-malen-och-agenda-2030.

- Snyder, H. 2019. “Literature Review as a Research Methodology: An Overview and Guidelines.” Journal of Business Research 104: 333–339. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.07.039.

- Sumarliah, E., T. Li, and B. Wang. 2020. “Hijab Fashion Supply Chain: A Theoretical Framework Traversing Consumers’ Knowledge and Purchase Intention.” 8th International Conference on Transportation and Traffic Engineering, 308: 04004. doi:10.1051/matecconf/202030804004.

- Svendsen, L. 2006. Mode: en Filosofisk Essä (Fashion: A Philosophical Essay). Nora: Nya Doxa.

- Swedish Chemicals Agency. 2014. “Chemicals in Textiles: Risks to Human Health and the Environment. Stockholm: Swedish Chemicals Agency. http://www3.kemi.se/Documents/Publikationer/Trycksaker/Rapporter/Report6-14-Chemicals-in-textiles.pdf%5Cnhttp://www.kemi.se/en/directly-to/publications/reports

- Talbot, L. 2018. “Reclaiming Value and Betterment for Bangladeshi Women Workers in Global Garment Chains.” In Creating Corporate Sustainability: Gender as an Agent for Change, edited by B. Sjåfjell and I. Lynch Fannon. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Thomas, S. 2008. “From ‘Green Blur’ to Ecofashion: Fashioning an Eco-Lexicon.” Fashion Theory 12 (4): 525–539. doi:10.2752/175174108X346977.

- United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). 2021. “Sustainable and Circular Textiles.” Nairobi: UNEP. http://www.unep.org/explore-topics/resource-efficiency/what-we-do/sustainable-and-circular-textiles

- United Nations Climate Change (UNCC). 2015. “The Paris Agreement.” New York: United Nations. https://unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/the-paris-agreement/the-paris-agreement

- United Nations. 2015. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.” New York: United Nations. doi:10.1007/s13398-014-0173-7.2.

- United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). 2020. “Fashion for Global Climate Action. New York: United Nations. https://unfccc.int/climate-action/sectoral-engagement/fashion-for-global-climate-action

- Vijeyarasa, R., and M. Liu. 2022. “Fast Fashion for 2030: Using the Pattern of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) to Cut a More Gender-Just Fashion Sector.” Business and Human Rights Journal 7 (1): 45–66. doi:10.1017/bhj.2021.29.

- Walk Free Foundation 2010. “Global Slavery Index.” https://www.globalslaveryindex.org

- Watson, D., J. Eder-Hansen, and S. Tärneberg. 2017. Call to Action for a Circular Fashion System. Copenhagen: Global Fashion Agenda. https://refashion.fr/eco-design/sites/default/files/fichiers/A%20call%20to%20action%20for%20a%20circular%20fashion%20system.pdf

- World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED). 1987. Our Common Future. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Zamani, B. 2014. “Towards Understanding Sustainable Textile Waste Management: Environmental Impacts and Social Indicators.” Licentiate Thesis, Department of Chemical and Biological Engineering, Chalmers University of Technology, Göteborg, Sweden.