Abstract

Sustainability transformations involve processes of social change that are carried by people. In the area of food systems, researchers have studied local food groups as an emerging phenomenon driving collective action toward systems change. A central question in this regard is how agency develops in a dynamic alignment between individual actors and collective action. Identity dynamics, as a result of social interactions at the individual and collective levels, help to understand processes vital to the functioning of local grassroots initiatives. This study provides an empirical examination of the interplay between individual and collective level identity in the formation, operation, and impact of local food groups. Using a case study of a food cooperative in northern Germany, we apply a conceptual framework around identification, verification, and formation dynamics. Results show that identity dynamics are well developed and important for the functioning of the food cooperative. Trust is central to the group, as it enables the various activities of the collective, which in turn is facilitated by the interaction and identity dynamics. Understanding initiatives not just as niches for individual political action or as alternative sources of sustainable products, but as social spaces of self-expression and community building, contributes to the discussion of how local initiatives can help to advance sustainability transformation.

Introduction

A transformation toward sustainability is accomplished by people (Middlemiss and Parrish Citation2010; Abson et al. Citation2017; Mock et al. Citation2019). Under the concept of enabling transformation, a vibrant field of research has emerged that focuses on agents of change and conceives of human agency, values, and capacities as prerequisites for managing uncertainty and collective action (O’Neill Citation2018; Scoones et al. Citation2020; Caniglia et al. Citation2020). In this context, opportunities for transformation are seen in aggregated individual actions that collectively, over time, shift system states in ways that may be unexpected but reflect the values and visions of the mobilized actors (Scoones et al. Citation2020). Grassroots initiatives are described as an effective lever to enable change as they spur innovative bottom-up solutions for sustainable development (Middlemiss and Parrish Citation2010; Hossain Citation2016). They are civil society-based and locally organized and can therefore respond to specific conditions on the ground and incorporate the interests and values of the communities involved. This enables them to act as spaces where individuals and organizations collaborate to develop localized bottom-up solutions for sustainable development (Seyfang and Smith Citation2007).

The development of local alternatives and niches has become a focal area of interest in the search for pathways toward more sustainable food systems (Levkoe Citation2011; Duell Citation2013; Pitt and Jones Citation2016; Weber et al. Citation2020). Sustainability scholars from diverse backgrounds are exploring how local grassroots initiatives form, operate, and create impacts, and under which conditions individuals and communities can be empowered to take action on their own behalf (Scoones et al. Citation2020). A key question in this regard is how agency develops in a dynamic alignment of individual actors and collective action (Grabs et al. Citation2016). Recognizing that not only individual choices but collective-level processes play a significant role in this process (Fritsche et al. Citation2018), research has stressed the need to more deeply engage with social psychological dynamics in grassroots innovation and other groups working for change (Maschkowski et al. Citation2015; Fritsche et al. Citation2018; Mock et al. Citation2019).

A number of studies engaging with the social-psychological dimension of initiatives working for sustainability have explored determinants of individual motivations to participate in those groups. In a study of the psychological well-being of people in sustainability initiatives, positive relations with others is seen as the most important motivating factor (Mock et al. Citation2019). Similarly, a study of grassroots movements shows that group cohesion, social capital, and collective action deriving from group dynamics motivate actor engagement (Maschkowski et al. Citation2015), and how collective processes around social identity help to explain pro-environmental behaviors (Barth et al. Citation2021). In addition, Grabs et al. (Citation2016) conducted a multi-level analysis of individual-level motivations, group-level interactions, and societal-level conditions in order to understand why grassroots innovation in the context of sustainable consumption is successful. Their findings reveal a number of social-psychological factors as relevant, especially pointing to the importance of positive group dynamics and feedback mechanisms between individuals and group (Grabs et al. Citation2016). These studies demonstrate the value of focusing on social interactions in grassroots initiatives as a factor shaping the motivations of individuals and the conditions for collective action.

The concept of identity has been proposed as potentially useful to bridge what Grabs et al. (Citation2016) describe as a gap in understanding the important nexus between individual motivation and collective action. It directs the researcher’s attention to processes in social interaction that construct and shape the self-understanding of individuals and the group’s understanding of “we” (Stets and Biga Citation2003; Burke Citation2004). This focus is promising for studying individual engagement and social interactions in local food groups. Thus far, however, the field of identity research, sustainability, and food has predominantly focused on individual political activism or marketing but largely failed to recognize how identities are shaped in the interplay of individual and collective levels in grassroots initiatives. Where local food and identity are studied, they have been conceptualized as collective identities in food movements (Bauermeister Citation2016) or described as individualized political action through alternative consumption practices (Dobernig and Stagl Citation2015).

One strand of prior research on local food and identity has explored different ways of using and appealing to local identity to market local and sustainable produce to consumers (e.g., Moreno and Malone Citation2021). Another area of research has sought to understand factors (e.g., status, class) influencing the formation of ethical consumer identities (Huddart Kennedy, Baumann, and Johnston Citation2019) and how ethical consumers navigate tensions and tradeoffs between local and organic foods (Long and Murray Citation2013). Only a few studies have considered the emerging processes of identity construction(s) at the interplay of individual and collective levels and the “identity dynamics” that they involve (Grabs et al. Citation2016). While this literature has provided preliminary evidence of the importance of identity dynamics for understanding individual consumer behavior and the group/collective aspects of engagement in sustainability (Barth et al. Citation2021), it has also been limited by its narrow focus on isolated levels of identity and its emphasis on the individual.

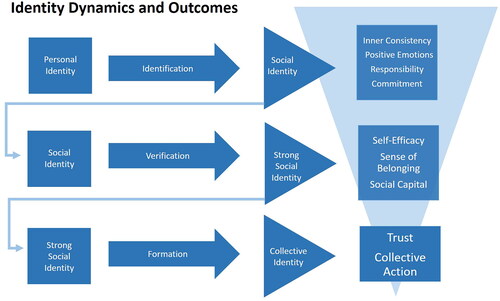

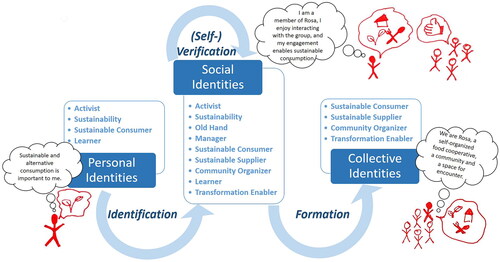

Identity dynamics refers to the multitude of social interactions on the individual and collective level that are used to define, integrate, and confirm one’s identity. Those interactions happen mostly unconsciously and are used in, for instance, social psychology and organizational psychology to explain a diverse set of behaviors (Pratt Citation2014; Fritsche et al. Citation2018). Identity dynamics in this study revolves around identification, that is, the process of identifying with a certain social category, as well as the ongoing verification of one’s identity through acting in accordance with that identity and receiving social feedback (Burke and Stets Citation1999; Stets and Burke Citation2000). Collective identity formation refers to identity dynamics that are engaged in producing a collective identity (Taylor and Whittier Citation1992).

The current study provides an empirical investigation of the interplay of identity on individual and collective levels in the emergence, operation, and impact of local food groups. By focusing on identity dynamics as a perspective that has been theoretically and empirically underutilized, it offers a more nuanced approach to researching local food initiatives as a space for identity construction in sustainability transformation. This lens helps to consider how identity dynamics can be useful and deepen the understanding of members’ engagement and create collective action for food-systems change on the local level. More broadly, the study of identity dynamics is also relevant to research on other types of groups, which is particularly meaningful in the context of the transformation to support sustainability initiatives, as it offers a novel approach to connect and understand individual and collective level dynamics. We use the empirical case of a food cooperative in Northern Germany to answer the following research questions:

How do identity dynamics unfold in local alternative food groups?

What are the outcomes of identity dynamics at the individual and collective level in local alternative food groups?

This integrated approach to exploring identity in local food groups offers a new perspective on the potential of grassroots initiatives to work toward a more sustainable future. Our case study approach is informed by a conceptual framework of identity dynamics, which we will introduce in the next section. The case-study research serves as an empirical exploration of the conceptual framework and to illustrate its usefulness for understanding dynamics of local food groups and potentially other grassroots initiatives. We then outline the methodological approach of our case-study design, report our main findings, and critically discuss them considering the literature. We conclude by highlighting implications of this study and future research avenues.

Identity dynamics in local food initiatives: a conceptual framework

Local food systems are characterized by direct and localized relationships with producers, short supply chains, and higher nutritional quality of food (Feenstra Citation2002; Duell Citation2013; Batat et al. Citation2016). They typically comprise small-scale alternatives and collaboration in different organizational forms or activities rooted in local landscapes, such as purchasing groups, food-sharing initiatives, community-supported agriculture, and community gardens. The academic discussion of local food systems continues to evolve. The early assumption that local systems were the better alternative to the global food system (Feenstra Citation1997), which was later referred to as the “local trap” (Born and Purcell Citation2006) has evolved into a more nuanced examination of local producers and distributers and their impact on food systems. Enthoven and van den Broeck (Citation2021), for instance, show in their comprehensive review that the actual impact of local food systems depends on the type of supply chain being studied. Authors emphasize the possibility that “relational proximity” (Eriksen Citation2013) allows not just for the development of direct relations between local food-system actors and consumers but also a wider impact of local food initiatives on community and political participation in the change process toward sustainability (Connelly, Markey, and Roseland Citation2011; Kneafsey et al. Citation2013; Valchuis et al. Citation2015). Similarly, local food initiatives have been shown to provide spaces for community development (Connelly, Markey, and Roseland Citation2011). Critical reflection is needed to avoid the reproduction of unequal power structures in the food system and one-dimensional assumptions that local is better (DuPuis and Goodman Citation2005; Levkoe Citation2011; Duell Citation2013; Kirwan and Maye Citation2013).

Local buying groups, also known as food cooperatives or food co-ops, collectively buy produce according to specific standards, often driven by a commitment to social justice and environmental sustainability, as an approach to re-interpret what “quality” means regarding food consumption and production (Fonte Citation2008; Brunori, Rossi, and Guidi Citation2012; Zitcer Citation2017). Food co-ops have been characterized in prior research as communities practicing solidarity within the group and with producers, working toward improving employment and working conditions of actors along the supply chain (Weber et al. Citation2020). They are run by citizen-consumers and aim for reflexive consumption (Fonte Citation2008; Brunori, Rossi, and Guidi Citation2012; Broad Citation2016). These groups organize their consumption choices around ethical considerations and food has been identified as a prominent form of ethical consumption (Huddart Kennedy, Baumann, and Johnston Citation2019). Ethical consumption is concerned with buying goods and services that are produced in circumstances that meet the consumer’s ethical criteria (Carrier and Luetchford Citation2012, Huddart Kennedy, Baumann, and Johnston Citation2019) and has been widely studied in the context of sustainable consumption (Oh and Yoon Citation2014). The employment of identity theory has in this context proven meaningful as a factor to determine individual’s choices, thus making identity relevant in the context of consumption, food, and sustainability (Huddart Kennedy, Baumann, and Johnston Citation2019). Local grassroots initiatives as ethical consumptions sites offer a way to understand consumption from more than a monolithic individual-identity perspective, acknowledging the embeddedness of consumption, as well as community aspects (Soron Citation2010). The examination of identity dynamics serves to enhance an understanding of the direct relationships between members of local food initiatives, the social spaces they provide, and collective action undertaken by these groups. In our case study, a conceptual framework of identity dynamics (Poeggel Citation2022) is used to empirically analyze the role of identity in the interplay between individual and collective levels. The framework distinguishes three phases: identification, verification, and formation. The tripartite distinction is based on social psychological identity theories, which define identity as a set of meanings individuals hold for themselves that define who they are, as a person, as group members, and as a collective (Stets and Biga Citation2003; Burke Citation2004). Mobilization theory together with aspects of collective identity incorporate the wider context of society and culture, which is valuable for exploring the group and its societal dimensions (Taylor and Whittier Citation1992). The framework around identity dynamics provides insights into internal processes of individuals and groups, and how the different identities an individual possesses are formed and strengthened.

Identification

As an individual becomes a member of a group, they come to increasingly identify with that group and this first identity dynamic is called identification, the process of locating oneself within a system of social categorization (Stets and Burke Citation2000). Social categories develop by focusing on similarities, common fate, proximity, shared threats, and other factors, and in a social comparison process individuals recognize others similar to their own social category and label them as the in-group (Stets and Burke Citation2000). In this process, specific personal identities are linked to particular social identities, and consequently a personal identity expands to include a social identity (Deaux Citation1992). The outcome can be beneficial on individual and collective levels. Identification provides inner consistency as individuals can act according to their own values, therefore contributing to a sense of self (Turner Citation1982; Maschkowski et al. Citation2015). On a collective level it can lead to a strong attraction and greater commitment to the group (Hogg and Hardie Citation1992; Ellemers, Spears, and Doosje Citation1997). When the individual adopts a social identity, it provides a strong foundation for joint action and for further identity and social dynamics, making group behavior possible (Turner Citation1982).

Verification

In a second step, the verification dynamic is a process where an individual’s social identity is invoked and verified through a cognitive process of matching the self-relevant meanings occurring in group situations with internal identity meanings and through behaving according to one’s own identity. This process occurs by regarding the responses and views of others in the group (Burke and Stets Citation1999). Verification within a group can generate positive feelings and commitment, as the individual develops a perception that he or she is part of a group (Burke and Stets Citation1999). Trust in the group develops, which is an important condition for collective mobilization (Gawerc Citation2016). Similarly, group processes and joint action lead to social capital as group cohesion and connections between group members develop (Maschkowski et al. Citation2015).

Formation

The formation processes around collective identity are threefold. First, the development of boundaries as a set of markers, similar to social categories, means individuals being located as members of a group and creating new values and structures that heighten the group’s sense of self (Taylor and Whittier Citation1992). Second, the group becomes conscious of itself as a group. Members reevaluate themselves and their experiences in regards to dominant structures and define socially constituted criteria that account for the group’s structural position (Taylor and Whittier Citation1992). Finally, negotiation is a way of thinking and acting in private and public settings established by the group that “encompasses the symbols and everyday actions subordinate groups use to resist and restructure existing systems of domination” (Taylor and Whittier Citation1992). The three processes construct and shape the group’s collective identity. The formation of a collective identity is critical for understanding ongoing participation and commitment in groups (Biddau, Armenti, and Cottone Citation2016) as it fosters group cohesion, produces and maintains shared meanings, and fosters a sense of collective purpose.

Case study

The aim of this article is to explore how identity dynamics unfold in local alternative food groups and how they influence the individual and the group. A case-study approach allows a rich description of a phenomenon (Yin Citation2018) as well as testing and advancing a theoretical framework (Siggelkow Citation2007; Crowe et al. Citation2011; Gustafsson Citation2017). A preliminary investigation will indicate both whether the conceptual framework is applicable and if it can serve for analytical generalization by allowing local food initiatives to be considered in terms of the social spaces they provide (Siggelkow Citation2007). A combination of methods highlights different perspectives on the same problem. The initial participant observations helped us gain a wider understanding of the case and prepared the ground for a two-step interview approach, which aimed at understanding the perspective of the participants on their identities, and the identity dynamics occurring on an individual and group level. Similarly, the context of a case study allowed us to take into account the wider social and political environment and consciously apply reflexivity measures to accommodate our subjectivity (Crowe et al. Citation2011). Here, the design of the case study with a specific conceptual framework, including forms of triangulation and transparency in the research process, enable scientific rigor and preempt potential pitfalls in case-study research (Flyvbjerg Citation2006; Crowe et al. Citation2011). In the following section we explain our positionality, provide a detailed account of the case, discuss why we chose it, and describe our data collection and analysis procedures.

Positionality

Research is a process shaped by the person doing the investigation and their inherent bias (Bourke Citation2014). In the current case study, the first author was the sole researcher gathering data in this project, while the second author supported this process, contributed to the study conception and design, and was actively engaged in writing the manuscript. Thus, the statement of positionality and data-collection moments are narrated in the first person from the perspective of the first author. I am a member of the food cooperative and thus have an insider status that brings advantages. Nevertheless, personal involvement can also lead to a further influence of positionality (Bourke Citation2014; Unluer Citation2015). In order to address this situation, reflexivity was practiced throughout the entire research project as a process of understanding the researcher’s positionality and how it affected the research and its findings (Watanabe Citation2017). I am a female PhD researcher and studied sustainability for several years with a special interest in food, food-systems transformation, and the socio-cultural contexts of food production and consumption. In the food co-op, my insider role consisted of being a group member with similar values as well as being involved with the university, both of which built trust and provided access to the field and participants. My outsider role was defined by my position as the researcher as well as the fact that I am a lecturer at the same university, both of which may imply hierarchy and institutional representation. Overall, the entire research process is shaped by my interest and theories, and the interview in particular, as a complex, meaning-making dialogue, is embedded in a relationship with a power imbalance (Finlay Citation2002).

To accommodate positionality and power imbalance, I took several measures. Research diaries helped to remain reflective on positionality throughout the process. When entering the field, I always informed the other members about the research we were undertaking (Bourke Citation2014). As described above, the two-step interview approach allowed a narration to unfold and the participant to comment on our reading of it (Finlay Citation2002; Hammersley Citation2003). In this way, the interview process took longer, reflection was facilitated, and both parties were more equally involved, acknowledging the process of knowledge co-production (de Fina Citation2015). Deductive analysis of the data assured a focus on theoretical concepts, reducing the influence of any insider role on analysis. Throughout the whole research process ethical issues were considered and the fieldwork involved an external advisor and collaborator to minimize the impact of positionality (Unluer Citation2015). The sum of these measures assured that positionality was acknowledged, accommodated, and the potential limitations of the research approach were minimized.

Case and case selection

Local buying groups are common examples of grassroots innovation. In Europe alone, there are an estimated 40,000 agricultural cooperatives with approximately 9 million farmer-members and over 600,000 workers (Ajates Citation2020). This study focuses on the case of a local purchasing group – hereafter called Rosa – in a medium-sized city in Northern Germany that provides organically grown and low-waste products. One of the researchers has been purchasing produce from the group for many years and has had at times a more active role within the organization. Rosa’s aims are to keep transport distances as short as possible, promote organic farming (especially in the region), and create low-waste impact. Rosa operates as a food co-op and has been providing sustainable food for about three decades to up to 400 members. The co-op is connected to the local university and counts as a student initiative, so many of its members are drawn from this community. The level of engagement is very fluid, with 5–20 people actively involved in keeping the initiative running. Rosa relies on volunteer labor and many dedicated Rosa members organize themselves in working groups to order and unpack products, keep the store clean, and handle various chores. This keeps the cost of its products comparatively low. The purchasing process at Rosa is based on trust. Members enter the shop by inputting a password onto a keypad, weighing their produce into the containers they have brought, totaling the costs of their items, and electronically transferring the money to the co-op’s bank account. The food cooperative is self-organized, and decisions are made consensually by all members after a process of deliberation. The main decision-making body is a plenary meeting that takes place once a month, with all discussion based on principles of direct democracy with the aim of open and respectful communication. Rosa’s long-standing existence in combination with a model solely based on volunteering are characteristics that make it a suitable case for this study’s interest in understanding the role of identity processes in sustainability initiatives. The assumption is that a long-operating volunteer-based food co-op has established practices and processes to connect and align the identities of individual members with the collective identity of the cooperative in a way that has enabled its continued functioning.

Data collection and analysis

Data collection for this project spanned several months, in part during the COVID-19 pandemic. In line with case-study methodology, one of us (Poeggel) engaged in participant observation at the beginning of the research and regularly took part in the working groups, the plenary sessions, and used the cooperative’s communication platform. This essential step allowed for a first understanding of the hows and whys of the group (Guest, Namey, and Mitchell Citation2013). Because I was immersed in the group, this provided direct experience of the activities and thus a holistic knowledge of the setting, activities, and meaning of the group, as well as an understanding of the broader context in which people interacted (Spradley Citation[1980] 2016). Further, participation in the work of the group helped to build trust, which facilitated interaction with the group and thus made further data collection (e.g., interviews) easier. Observation protocols ensured that a structured record of experiences was maintained during the lively working meetings. The data obtained informed the interview process as background knowledge.

A two-step interview approach facilitated the further collection of data, with narrative interviews as a first step and follow-up semi-structured interviews as a second step. The two-step approach allowed the interviews to be explicitly recognized as a performative social interaction and reflection space (Hammersley Citation2003). It also gave greater emphasis to knowledge co-production as it was a more extensive (two points in time) and a more interactive process. Finally, this methodology also helped to acknowledge and critically reflect on positionality and power in shaping the interview and its interpretation, for example, by including member checks for the purpose of triangulation, thereby giving participants more power over the reading of their data. The two-step interview approach allowed the participants to freely choose to talk about what they considered relevant, with the result that the outcome of the interview was less influenced by researchers’ positionality and self-interest. Nevertheless, the second interview gave the opportunity to ask deeper and more specific questions, while acknowledging the interview situation as performative, contextual, and as a reflective social space.

One of the key predicaments of the narrative interview method is that personal stories become the organizing principle for human action as individuals construct past events and actions in personal narratives to claim identities and construct lives (Riessman Citation2002). Identity dynamics is the explicit focus of this study, and their inherent connection to narratives as a way to express and negotiate individual and collective identities suggests the use of narrative interviews (de Fina Citation2015). The interview was prompted with “Tell me your personal story with Rosa!” and the participant was free to talk about whatever came to mind. In narrative interviews, the emphasis is on a free and uninterrupted flow of narration, as the meaning-making structure of the narratives must be preserved (Riessman Citation2002). The beginning of the second semi-structured interview was marked by a member check. A written case description based on the analysis of the first interviews was read by the participants, followed by an invitation to provide feedback. The semi-structured approach enabled us to formulate more specific follow-up questions to things that had been said and/or to ask questions about additional aspects previously not mentioned by the participant (e.g., questions derived from the conceptual framework). The second interview was also used to actively reflect on the interview situation and gave the participant the opportunity to also ask questions of the researcher. The selection of the sample was guided by the research focus on identity dynamics in the local food groups. Hence, the selection of respondents was based on who was frequently involved in the various activities of the food cooperative, such as attending plenary meetings, participating in the various working groups, and being active on the communication platform (). Duration of engagement was a significant sampling criterion, as frequent engagement shaped interactions in the groups and made their perspectives relevant to the theory and resulting research questions. The findings of participant observation guided the selection of the sample. For comparison purposes, the analysis included two individuals who were either freshly involved in the group or had not been very active in the recent past. This supplemented the number of individuals who are very involved and had been involved for a long time (up to a decade). Seven members were chosen for interviews as the focus of the sample was to provide a rich, complex, and detailed representation of the identity dynamics in the food co-op. After the first author had been involved with the food cooperative for a period of time and had conducted a series of participant observations, members were selected for interviews. The narrative approach was explained to them and seven interviews of varying lengths were conducted, as interviews were terminated whenever no further thoughts were added. All interviews were audio-recorded. The first set of interviews was then transcribed and analyzed using a codebook based on the conceptual framework. After approximately three months, the second set of interviews was conducted with the opportunity for member checking and asking more explicit questions, which varied slightly according to the analysis of the narrative interviews. The second set of interviews was also recorded and transcribed. The transcripts of the interviews formed the core of the data analysis. The transcripts were coded based on qualitative content analysis and the codes were deductively derived from the conceptual framework. Each transcript was read and analyzed line by line.

Table 1. Overview of interviewees.

Findings

We structure the presentation of our findings along the lines of the two research questions of this study: (1) How do identity dynamics unfold in local alternative food groups and (2) What outcomes do they have at the individual and collective levels in these groups?

Identity dynamics and outcomes

In what follows, we will present the main findings for each of the three process steps of the framework separately: identification, verification, and formation (). The name of the food cooperative and the members are anonymized by using pseudonyms, and direct quotes are translated from German. The interview sources are denoted as I1 and I2, corresponding to the two interviews conducted in the two-step interview approach.

Identification: “Sustainable and alternative consumption is important to me that’s why I am part of Rosa”

Identification is the process of locating oneself within a system of social categorization (Stets and Burke Citation2000) and recognizing others or a group similar to these categories to develop a social identity. In terms of self-categorization in Rosa all participants emphasized the importance of sustainable consumption for them, speaking about organic certification and low waste reflecting a personal sustainable identity: “But the initial motivation, which I still find important, is to buy organic products with as little packaging as possible” (Fiona, I2). Similarly, most participants wanted to actively engage in creating a consumption alternative and be a hands-on part of organizing a more sustainable consumption space that reveals a personal activist identity: “Yes, I think because I also have wanted to be part of something, to help organize something” (Peter, I1). Most became aware of the initiative through their social circles, which in turn were often made up of people who exhibit personal identities of sustainability and activism: “But all of them were somehow at Rosa [laughs]. So, um…the people or the group that I had to do with, it was clear that they live in shared flats, um, bigger or smaller, who anyway shop at Rosa” (Sabrina, I1).

Some co-op members also emphasized how their lifestyles are reflected in the product range of the initiative, for instance, Karen described how she finds all the products she needs for her vegan cooking at Rosa. Similarly, as they explained their relationship to Rosa, all participants used self-categorization that alluded to shared attributes of a social identity. In particular, sustainability and activist identity were described in relation to participation in the initiative, as these are relevant social categories for the group: “I think that through this topic, the topic of sustainable consumption, Rosa is an initiative that simply attracts people who tick similarly in a certain way” (Fiona, I1). Social identity was also clearly indicated by the framing of the participants when talking about joint decisions, the work they do collectively, and the recurring use of “we.” Philip described how he found himself to be part of Rosa: “And then suddenly I was part of it. Also more part of Rosa” (I1).

The social identity that the participants hold contributes to a sense of commitment they feel toward the initiative. Thus, Maria described, for instance, how she developed a routine to “just go there every now and then, and check if there is stuff that needs to be done and then get it done” (I2) and Fiona recounted the responsibility she feels toward the initiative, “I as an individual am responsible for the fact that things may or may not happen” (I1). Participants expressed a diversity of feelings in relation to Rosa. Positive emotions resulting from the identification process and the social identity the members hold was expressed in different ways. Maria described the initiative as her “feel-good place” and similarly Sabrina says “Well, it gives me a good feeling, uh, to have such a place in the city where I can, um, just go like this” (I1). The identification with a group can also provide a positive feeling of inner consistency and being able to live according to one’s values. “So, for example, that we now have maybe one or two more products from cool local people, uh, which then also makes me happy again on such a level that it saves even more packaging” (Peter, I1). Lara also described the positive feeling of being able to live out her ideals with Rosa “and I thought that was super great, that you can initiate something like that and live it out a bit” (I1).

Verification: “I am a member of Rosa, I enjoy interacting with the group, and my engagement helps to enable sustainable consumption for myself and others, which feels good”

The verification process of an individual’s social identity occurs either through feedback in interactions with others, in group situations, or by behaving according to their identities (Burke and Stets Citation1999). Verification was expressed by most participants through acknowledging positive feedback from others, “Oh cool, in two weeks we’ll order again and of course that feels nice to get feedback from other people too that it’s kind of a nice space for them to be in” (Peter, I1). This is often associated with special roles or a function individuals hold in the initiative and how others recognize them in this role. Sabrina described her role as an “old hand” and how having this position and others asking her questions “feeds her ego” (I1). Maria described how she became the go-to person for information: “I was more often in the store and very quickly was also asked things by new people. And…found myself very quickly also in the role where I also already passed on my knowledge. Which I thought was kind of cool” (I1).

Similarly, many of the participants articulated how the work they do for the initiative is fun because it is often a social activity and tasks are accomplished together. In terms of activities that verify their identity, all participants described how they enjoy buying food at Rosa and emphasized how it is in many ways better than conventional purchasing processes in the supermarket. Peter described how he enjoys going shopping at Rosa and meeting nice people while getting his produce and Lara described the advantages “so that it is just calmer and more relaxed. I have to make fewer decisions, because a preselection has already been made” (I2). Engaging in a non-conventional form of shopping and experiencing positive feelings can be seen as a verification of their identities as they behave according to their values. Being practically active for sustainability is quite important for most of the participants. Moreover, the feeling of having agency within/with the group and agency for transformation plays a role for a few as well and can be seen as a form of self-verification, especially in their social activist identity. “So I find then also the work with Rosa or also not only with Rosa somehow. In such contexts is also somehow something very satisfying, even if it is work somehow” (Peter, I2). Peter shows what others also experience when they reflected on how doing something for the initiative felt good as a form of self-verification and strengthened their identities potentially beyond their work with the co-op, for instance in their jobs or in activities in other food initiatives.

Ongoing verification processes lead to positive feelings toward the initiative, which were very prevalent among all participants. Many enjoy the space, how things are done at Rosa, the community, and the access to inexpensive but high quality and sustainable produce. Lara described it as “Well, the people are great and the products are great and the concept is just awesome” (I2). This connects with a sense of belonging to the group that develops from the verification processes. At Rosa it is recognizable in how they compared the initiative to family, emphasized how they feel at home and at ease in the space and in the group and expressed a feeling of connection to the initiative as a community. The ongoing verification and interaction in the group leads to relationships that can be described as social capital (Maschkowski et al. Citation2015). Many of them alluded to social capital and the network the initiative presents for them when they described how it is a group of people they know and like. “I have people there who know me, who I can approach with certain questions in any case and even beyond Rosa” (Maria, I2). They elaborated on how through personal contact the work in the co-op is organized and tasks get accomplished. A few also emphasized how different skill sets come together, there is a lot of exchange and discussion, and they learn from one another.

A strong sense of social identity is also connected to trust as another outcome of positive verification processes. “Yes, I trust the people who have ordered from Rosa because I know how they tick” (Lara, I2), which others also alluded to, emphasizing when a person belongs to the initiative they can trust them. Trust was repeatedly mentioned in the interviews and happens at many levels: Trust no one is helping themselves from the till, trust decisions made at Rosa are good decisions, trust others’ financial responsibility, and also trust that all people and ideas are treated equally: “a safe place and open and tolerant to everyone” (Karen, I2). As the identification process already created commitment to the co-op, this was enhanced by verification dynamics in the group. Especially the physical activities at the initiative, the alternative purchasing processes but also the work they do leads not just to inner consistency, but also to a feeling of self-efficacy. Most participants talked about how they enjoyed being active for their own alternative consumption, while also providing an alternative for others. This experience of doing practical work and seeing visible results that they expressed as “move something,” “make a difference,” “just design this myself,” and “get active for change.” This is also evident in the specific roles, functions, or areas of responsibility they delineated as their own. “So that I have the feeling that, hey, this also really has remarkable, uh, effects and that feels very good, of course” (Peter, I1)

Formation: “We are Rosa, a self-organized food cooperative, a community and a space for encounters and we organize alternative consumption for ourselves and others”

In a formation process, a group develops a collective identity by engaging in three distinct processes: boundaries that define and demarcate the group from others, the development of a consciousness of the group itself and its structural position in society, and negotiation, that is, shared ways of thinking and acting (Taylor and Whittier Citation1992). The boundaries of the co-op mentioned by the respondents were formed on multiple levels. Boundaries define a consumption space that demarcates the initiative from conventional stores such as supermarkets. Here the participants mentioned cheaper prices, organic certification, trustworthy products, less packaging, fewer choices, and greater quantities.

Participants additionally described the activity itself as less anonymous and often more sociable but also needing more time. “So it’s not like that, it’s not as anonymous as in a store, that somehow a thousand people are shopping there and you never talk to each other, but when you meet someone in Rosa, you chat” (Karen, I1). Also, the structure is very different to other consumption spaces, as it is self-organized and carried out by volunteers. And even for an initiative Rosa is different with a low involvement threshold and few fixed structures. Moreover, active members stay involved longer compared to other (student) initiatives. The co-op sees itself as an open space, a place of encounters, where people have a consciousness of sustainable consumption and being active for a more sustainable society. A few participants described the initiative as a “playground” to experiment in self-organization, to learn to implement different values, and to take on responsibility as a basis for transformation. “And for me, Rosa was somehow a part of this free space, of trying things out in self-organization. And I do believe that such experimental spaces are good, that they are important, and that they are also important for a transformation” (Philip, I2). Basic values are an appreciation of food, sustainability, community, trust, solidarity, and sincerity, all of which set the co-op apart from other consumption spaces and initiatives.

The group negotiates its structure through volunteers, is self-organized, and without hierarchy, and so every person acts in accordance with their own responsibility, which makes it very flexible and adaptive. Therefore, the initiative is able to change according to its active members, which gives the group resilience. “And I definitely appreciate that things are relatively loose, that, ahem, people act on their own responsibility with their own tasks” (Maria, I1). Rosa is a large, loose social network, some members with a passive consumer attitude and a core of members who actively participate and come to the plenaries. Decisions are made collectively, for instance, the criteria for the products discussed in smaller working groups or in the bigger plenary session. Community is an important value, as members not only take joint decisions but also work together. Other key values in the group are honesty, sincerity, and trust. Also values like transparency, equality, and diversity in the group and in their communication and decision-making are important. “People tend to communicate in a friendly way and with positive phrases…or also work in a transparent way, for example” (Sabrina, I2). The communication culture is also extremely positive. It is very constructive, caring, and sympathetic, framed with positive wording, respect, and equality, which creates a safe space for everyone to become involved without others judging them. However, most participants emphasized that there is always something not working perfectly at Rosa, and one member complained that at times there is a certain unreliability.

In different processes members negotiate how things are done in the co-op, which establishes a consciousness that demarcates the group from others, forming a collective identity. The collective identity of the initiative acts like an umbrella under which there is room for many different aspects with which individual members identify. The participants portrayed Rosa as an open space, a place of encounters, where people become active because of the bigger idea of sustainable consumption and transformation. Maria, for instance, talked about how the co-op opens avenues for broader change. “So a very, very important realization that there is an alternative at this point, which is not perhaps the organic supermarket, but somehow something else, because not only the component of shopping is changing, but also the societal structure and so forth” (I2). Lara emphasized that the political spectrum is very broad, ranging from radical anti-capitalist ideals to ecological values and solidarity-based consumption. The core values mentioned are an appreciation of food, sustainability, community, trust, solidarity, openness, and sincerity.

This collective identity empowers members to take collective action. The group discusses strategic and sustainable consumption. Collective action in Rosa also involves deliberations and collective decision-making, as well as the joint completion of the work at hand. An important part of the formation dynamics is that it enables the development of trust among members in the collective. Trust is a central theme among all members and occurs on many levels. The entire organization operates on trust, and without control mechanisms. Trust in the continued existence of the group is also expressed by its members. “But Rosa has actually always shown that it’s somehow possible to make progress over time [laughs] and overcome problems. And, um, yes, I trust that this will continue” (Maria, I1). Expressed outcomes of the formation dynamics are commitment and a sense of belonging. The process of forming a collective identity allows members to be committed to the initiative, its operations, and its goals, which is evident in a variety of ways among the participants. The core members are engaged and have been for a long time (e.g., Maria for two years, Peter for four years, and Sabrina for seven years). Even members who are not highly involved sometimes take on smaller or larger tasks or would do so whenever someone asks. The active members show a sense of duty toward Rosa. Similarly, their sense of belonging becomes evident as they describe Rosa as “family,” feel “at home” and feeling good with the group and the space, as well as expressing a feeling of connection to the community and experience positive relations with the other members.

Outcomes of identity dynamics

This study shows that taking on a distinct role with responsibilities and functions in a group is a pathway to identity verification. Verification of individuals occurs very much through group interactions, especially when the person has a special role in the group, identifies strongly with it, and receives positive feedback from others for fulfilling that role. Besides the importance of social interaction for the verification of individuals in their identities, we demonstrate how internal and individual levels play an important role in verification. In particular, processes of self-verification, such as individuals’ activities for the group, as well as the alternative consumption process, are important for the verification of individuals’ identities. Taking on tasks and doing work for the co-op, even alone, is often experienced with positive feelings by the active members, as they are verified in their activist identity enabling alternative and strategic sustainable consumption. Similarly, the act of selecting and buying alternative food products, as a clear boundary activity to conventional consumption, relates to good feelings for most participants and validates them in their sustainable identity. In addition to buying at the co-op, many participants highlighted the physicality of their work and how they experience the immediate effects of their activities. In both activities, the participants can act according to their own values and experience a sense of self-efficacy that verifies their identity.

Another finding of this study is that the multiplicity of identities held by an individual are negotiated in the initiative. Collective identity serves as an umbrella for diverse identities with different outcomes. Especially, an activist and a sustainability identity are found and described in the findings, as these are the main personal identities that evolve to social identities in the context of the local food initiative. While the sustainability identity referenced a more private space of individual consumer actions, the activist identity referred to a more collective space of civic action. In addition to these two identities, role identities (e.g., being a manager or “old hand”) showed to be important for the engagement of the participants, and many mentioned how it was central for them to be verified in these roles. This finding confirms the relevance of the framework used in this study. The self-image as a sustainable consumer proved significant for their behaviors. In their identity as a sustainable supplier, they enable sustainable consumption for others. The activist identity, which facilitates new forms of community with diverse and practically lived values, plays a role for many of the interviewed members. Moreover, the initiative serves as a space for personal development where members see themselves as learners. These different identities play a role within the initiative, but also externally as boundary markers. The political spectrum of the members is also diverse but gathered under the collective identity of Rosa. Some members hold more radical anti-capitalist values while others only aim to consume sustainably. Their different identities have varying levels of importance for the members and serve to identify, be verified, and collectivized, even though they can be in a state of tension with each other.

Trust is a clear result of the different identity dynamics found in this study. Trust as a positive attitude toward others and the willingness to rely on them and being potentially vulnerable (Rousseau et al. Citation1998) was shown during the analysis to be an essential feature of the group. It is a crucial value the members and the initiative hold, and it occurs on multiple levels. In their meta-analysis, Rousseau et al. (Citation1998) also emphasized how identity-based trust evolves from repeated interactions over time, which create expanded resources, including shared information, status, and concerns. Participants explained that the work at Rosa is accomplished by a few people who have personal contact with each other, are in constant communication, and trust each other to carry out the tasks. Similarly, the caring and constructive communication within the group and the joint decision-making processes foster trust. Members emphasized that all people and ideas are treated equally and described the group as a “safe place.”

The study of the framework shows how reliability and dependability in previous interactions give rise to positive expectations and furthers trust, which in turn facilitates the interaction and functioning of the group (Rousseau et al. Citation1998). Even the financial component of the initiative operates solely through trust. Each member is given access to the consumption area after a formal introduction to learn how the shopping process works. They can then enter, shop, check out, and pay on their own. As noted earlier, the initiative has around 400 members, thus a high level of trust is necessary to ensure that no one is dishonest and that the members handle the products and space in a responsible way. This confirms that trust can develop when there are no control mechanisms and can work as a substitute for control, reflecting a positive attitude about another’s motives (Rousseau et al. Citation1998). The participants also highlighted that they trust the concept and other members, which stems from and has enabled the organization’s continued stability and long history.

Throughout this study, Rosa proved to be a learning space for its members on different levels. Many of the participants reflected that they have developed their interpersonal skills by taking on responsibility and leadership tasks. They mentioned that they have gained confidence through their engagement with the initiative, learned about teamwork, how to lead meetings, when to hand over tasks, when to take on responsibility, and how to use different facilitation tools. Some also reflected on how they transfer the knowledge they have gained from Rosa to other activities in which they are involved or in their first job after graduation. The participants also described their learning and knowledge gain in organizing a food co-op and in practical aspects of alternative consumption, as well as in sustainable consumption and sustainability through exchanges with each other. Framed as a “playground” for self-organization, the participants consider spaces like the local food group essential for sustainable transformation as they allow individuals to experience alternatives to the conventional system, to feel a sense of self-efficacy, and to develop agency. Thus, the findings show how the learning space that a local food group provides can create attributes and capacities that empower individuals and communities to act on their own behalf.

Discussion

This empirical case study explored the questions of how identity dynamics unfold in a local alternative food group and the outcomes that they have on the individual and collective level. We investigated a conceptual framework that highlighted different identity dynamics relevant to grassroots initiatives such as a local food cooperative. This research adds to the literature on social psychological processes and identity dynamics and their importance for engaging in and maintaining local food initiatives as examples of grassroots innovations for transformation (Maschkowski et al. Citation2015; Fritsche et al. Citation2018; Mock et al. Citation2019). The conceptual framework defines several identity dynamics occurring at individual and collective levels when people engage in initiatives for change and shows potential outcomes of these dynamics. We described the dynamics of identification, verification, and formation in the empirical data of the case study, as the participants told their stories about working in the food cooperative. The outcomes included engagement, positive emotions, trust, sense of belonging, and collective action ().

Important for the discussion of enabling transformation are the long-term effects of engagement in alternative initiatives such as local food groups. This study shows that through the activities in the co-op and the various identity dynamics, personal identities (e.g., activist and sustainability) were strengthened and new identities, relevant to a sustainability transformation, also developed within the group. One participant described how she chose her first job after graduation in the area of sustainable food and how her prior engagement contributed to this choice. Similarly, several participants talked about starting a new food co-op themselves. These personal accounts demonstrate how the experience of being active in the initiative can influence members beyond their initial encounters. A key finding is therefore that participation in a local food group may contribute to broader changes in society, reflecting an enabling understanding of transformation (Scoones et al. Citation2020).

Similarly, grassroots initiatives designed with a focus on identity dynamics and learning can act as levers for enabling transformations insofar as they provide individuals with opportunities to take on small actions that collectively and over time can shift the system (Scoones et al. Citation2020). The findings of this study can inform a more purposeful design of grassroots projects such as local food groups. Organizers, for example, could foster identity dynamics and learning spaces more strategically by establishing community-building spaces to create more sustainable (consumption) alternatives. Here, an atmosphere of trust within the group has proven crucial. This can be achieved through the different identity dynamics, as trustful relationships promote a positive attitude toward others and a willingness to rely on each other (Rousseau et al. Citation1998). In this study, identity dynamics were shown to evolve when individuals are attracted by similar values or roles with which they can identify. This study suggests that the organization of the group can be improved when it is based on personal contacts, regular meetings, and joint work. This allows for a form of social interaction in a context that can contribute to identity verification and the formation of a collective identity, and likewise may lead to positive relationships within the group. A focus on learning, for instance, through collaborative discussions and decision making, as well as a safe space where people are confident to contribute and take responsibility, can also support individuals in developing change agency. The value of trust and of organizing initiatives that foster trust could be a key feature in realizing alternative forms of consumption and more sustainable societies. In that sense, this study provides several indications on how to design and manage grassroots initiatives on a practical level.

When focusing on the theoretical and practical aspects of identity dynamics in grassroots initiatives like local food groups, consumption becomes more than just a choice of product. Instead, studying the identity dynamics on individual and collective levels, as well as their interactions, shows how consumption in a local food group becomes an expression of identity and a practice of (collective) action. The members attach meanings to their consumption practices that have performative and generative impacts on their identities. It helps to understand consumers in their social contexts as part of a movement, rather than as individuals acting alone. The employment and development of identity theory helps to shed further light on the social-psychological processes by which identities are produced. It acknowledges the role of social contexts, which can lead to trust, a sense of belonging, and collective action (Taylor and Whittier Citation1992; Maschkowski et al. Citation2015; Poeggel Citation2022). The purposeful usage of identity dynamics, accommodating the individual and collective level, is a way to understand how these different identity dynamics can interact and become effective as these two dimensions are often regarded separately (Barth et al. Citation2021).

This study has several limitations that need to be considered. Its aim was to elicit rich in-depth insights into how identity dynamics unfold and play out in a particular case. With this methodological focus, its findings are not intended to be generalized (Flyvbjerg Citation2006). Still, the case allows for theory testing and a preliminary in-depth description of a phenomenon that needs to be investigated in further research projects. The sample of this study is limited because it only recruited core members of the initiative, that is, those people who are active on a regular basis. In most cases, these members have greater access to financial resources and/or knowledge, which makes this case study sample exclusive (Allen Citation2010). However, by recognizing that the need for identification, affirmation, and belonging is fundamentally present in everyone (Burke Citation2004; Max-Neef Citation2017), a more complete understanding of identity dynamics and the facilitation of social spaces in grassroots initiatives such as local food groups provides an opportunity to make these same groups more accessible and diverse.

Similarly, the methodology shows more of an individualistic point of view in its reliance on interviews, as the empirical data were gathered when physical distancing regulations were in place due to COVID-19, rendering more interactionist research methods impossible. Another limitation results from the theoretical framework’s focus on potentially positive outcomes of identity dynamics. This, together with the sampling of core-active members, may have prevented the identification of more negative aspects of identity dynamics in the empirical material. While this focus was due to our interest in understanding the continued successful functioning of a group engaged in providing alternative food products, further research on failing identity processes and potential power issues is needed. Another limitation results from the fact that in this case, direct social interaction within confined physical spaces played a central role. Future research could focus more on the specifics of identity dynamics in digitally-mediated forms of social interaction in local food groups as a potentially increasing phenomenon in post-pandemic times. Finally, future research could supplement the analytical focus on identity dynamics within local food groups with deeper engagement with how identities form, change, or stabilize in response to external influences such as religion, advertising, and so forth.

Conclusion

This study examined processes of identity dynamics in local food groups and their outcomes. Informed by a framework that spans individual and collective levels of social interaction occurring in local food initiatives, the findings show that identity dynamics are well developed and significant for the functioning of the food cooperative. Identification dynamics are evident when members described shared attributes with the group that indicated a social identity and expressed positive emotions and responsibility toward the group. Verification occurs especially when members take on specific roles and tasks and receive feedback from the group. In addition, the work they do for the initiative, in the group or alone, leads to verification. Trust in the group, a sense of belonging, and commitment are connected with the occurrence of these identity dynamics. Formation dynamics are determined by the boundaries created by the group, such as the criteria for their products. In negotiation processes the group develops ways of doing and acting, such as an open organizational structure, individual responsibility, and trust-based interactions.

The consciousness of the group members for who they are and what they stand for also forms a prerequisite for a collective identity, which then enhances trust in the group and enables collective action. Diverse identities are expressed in the different identity dynamics of the group. Trust is central to this group as it enabled the various activities of the group and was in turn facilitated by the interaction and identity dynamics. The study of identity dynamics and thus understanding initiatives not just in terms of niches for individual political action or as alternative sources of sustainable produce, but as social spaces of self-expression and community-building adds to the discussion on how initiatives can contribute to transformation. As Maria, one of Rosa’s members, puts it, involvement and work in the local food group can “change the fabric of society” not only by enabling alternative consumption, but also by providing learning spaces to build community, be politically active, and thus participate in and work toward a more sustainable society.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee of Leuphana University. The study was approved by the Ethical Review Board of Leuphana University of Lüneburg. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Acknowledgments

This research was made possible within the graduate school “Processes of Sustainability Transformation,” which is a cooperative venture between the Leuphana University of Lüneburg and the Robert Bosch Stiftung. We also thank the research participants who agreed to be interviewed for this project, Paul Lauer for his assistance in proofreading, and the reviewers for their constructive and insightful feedback.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abson, D., J. Fischer, J. Leventon, J. Newig, T. Schomerus, U. Vilsmaier, H. Wehrden, et al. 2017. “Leverage Points for Sustainability Transformation.” Ambio 46 (1): 1–17. doi:10.1007/s13280-016-0800-y.

- Ajates, R. 2020. “Agricultural Cooperatives Remaining Competitive in a Globalised Food System: At What Cost to Members, the Cooperative Movement and Food Sustainability?” Organization 27 (2): 337–355. doi:10.1177/1350508419888900.

- Allen, P. 2010. “Realizing Justice in Local Food Systems.” Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society 3 (2): 295–308. doi:10.1093/cjres/rsq015.

- Barth, M., T. Masson, I. Fritsche, K. Fielding, and J. Smith. 2021. “Collective Responses to Global Challenges: The Social Psychology of Pro-Environmental Action.” Journal of Environmental Psychology 74: 101562. doi:10.1016/j.jenvp.2021.101562.

- Batat, W., V. Manna, E. Ulusoy, P. Peter, E. Ulusoy, H. Vicdan, and S. Hong. 2016. “New Paths in Researching ‘Alternative’ Consumption and Well-Being in Marketing: Alternative Food Consumption/Alternative Food Consumption: What is ‘Alternative’?/Rethinking ‘Literacy’ in the Adoption of AFC/Social Class Dynamics in AFC.” Marketing Theory 16 (4): 561–561. doi:10.1177/1470593116649793.

- Bauermeister, M. 2016. “Social Capital and Collective Identity in the Local Food Movement.” International Journal of Agricultural Sustainability 14 (2): 123–141. doi:10.1080/14735903.2015.1042189.

- Biddau, F., A. Armenti, and P. Cottone. 2016. “Socio-Psychological Aspects of Grassroots Participation in the Transition Movement: An Italian Case Study.” Journal of Social and Political Psychology 4 (1): 142–165. doi:10.5964/jspp.v4i1.518.

- Born, B., and M. Purcell. 2006. “Avoiding the Local Trap.” Journal of Planning Education and Research 26 (2): 195–207. doi:10.1177/0739456X06291389.

- Bourke, B. 2014. “Positionality: Reflecting on the Research Process.” The Qualitative Report 19 (3): 1–9. doi:10.46743/2160-3715/2014.1026.

- Broad, G. 2016. “Introduction.” In More than Just Food: Food Justice and Community Change, edited by G. Broad, 1–15. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Brunori, G., A. Rossi, and F. Guidi. 2012. “On the New Social Relations Around and Beyond Food: Analysing Consumers’ Role and Action in Gruppi di Acquisto Solidale (Solidarity Purchasing Groups.” Sociologia Ruralis 52 (1): 1–30. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9523.2011.00552.x.

- Burke, P. 2004. “Identities and Social Structure: The 2003 Cooley-Mead Award Address.” Social Psychology Quarterly 67 (1): 5–15. doi:10.1177/019027250406700103.

- Burke, P., and J. Stets. 1999. “Trust and Commitment through Self-Verification.” Social Psychology Quarterly 62 (4): 347. doi:10.2307/2695833.

- Caniglia, G., C. Luederitz, T. Wirth, I. von Fazey, B. Martín-López, K. Hondrila, A. König, et al. 2020. “A Pluralistic and Integrated Approach to Action-Oriented Knowledge for Sustainability.” Nature Sustainability 4 (2): 93–100. doi:10.1038/s41893-020-00616-z.

- Carrier, J., and P. Luetchford, eds. 2012. Ethical Consumption: Social Value and Economic Practice. New York: Berghahn Books.

- Connelly, S., S. Markey, and M. Roseland. 2011. “Bridging Sustainability and the Social Economy: Achieving Community Transformation through Local Food Initiatives.” Critical Social Policy 31 (2): 308–324. doi:10.1177/0261018310396040.

- Crowe, S., K. Cresswell, A. Robertson, G. Huby, A. Avery, and A. Sheikh. 2011. “The Case Study Approach.” BMC Medical Research Methodology 11 (1): 100. doi:10.1186/1471-2288-11-100.

- de Fina, A. 2015. “Narrative and Identities.” In The Handbook of Narrative Analysis, edited by A. de Fina and A. Georgakopoulou, 349–368. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Deaux, K. 1992. “Personalizing Identity and Socializing Self.” In Social Psychology of Identity and the Self Concept, edited by G. Breakwell, 9–33. Guildford: Surrey University Press.

- Dobernig, K., and S. Stagl. 2015. “Growing a Lifestyle Movement? Exploring Identity-Work and Lifestyle Politics in Urban Food Cultivation.” International Journal of Consumer Studies 39 (5): 452–458. doi:10.1111/ijcs.12222.

- Duell, R. 2013. “Is ‘Local Food’ Sustainable? Localism, Social Justice, Equity and Sustainable Food Futures.” New Zealand Sociology 28: 123–144. doi:10.3316/informit.813145421257062.

- DuPuis, E., and D. Goodman. 2005. “Should We Go ‘Home’ to Eat? Toward a Reflexive Politics of Localism.” Journal of Rural Studies 21 (3): 359–371. doi:10.1016/j.jrurstud.2005.05.011.

- Ellemers, N., R. Spears, and B. Doosje. 1997. “Sticking Together or Falling Apart: In-Group Identification as a Psychological Determinant of Group Commitment versus Individual Mobility.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 72 (3): 617–626. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.72.3.617.

- Enthoven, L., and G. van den Broeck. 2021. “Local Food Systems: Reviewing Two Decades of Research.” Agricultural Systems 193: 103226. doi:10.1016/j.agsy.2021.103226.

- Eriksen, S. 2013. “Defining Local Food: Constructing a New Taxonomy – Three Domains of Proximity.” Acta Agriculturae Scandinavica, Section B – Soil and Plant Science 63 (Supp. 1): 47–55. doi:10.1080/09064710.2013.789123.

- Feenstra, G. 2002. “Creating Space for Sustainable Food Systems: Lessons from the Field.” Agriculture and Human Values 19 (2): 99–106. doi:10.1023/A:1016095421310.

- Feenstra, G. 1997. “Local Food Systems and Sustainable Communities.” American Journal of Alternative Agriculture 12 (1): 28–36. doi:10.1017/S0889189300007165.

- Finlay, L. 2002. “Negotiating the Swamp: The Opportunity and Challenge of Reflexivity in Research Practice.” Qualitative Research 2 (2): 209–230. doi:10.1177/146879410200200205.

- Flyvbjerg, B. 2006. “Five Misunderstandings about Case-Study Research.” Qualitative Inquiry 12 (2): 219–245. doi:10.1177/1077800405284363.

- Fonte, M. 2008. “Knowledge, Food and Place: A Way of Producing, a Way of Knowing.” Sociologia Ruralis 48 (3): 200–222. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9523.2008.00462.x.

- Fritsche, I., M. Barth, P. Jugert, T. Masson, and G. Reese. 2018. “A Social Identity Model of Pro-Environmental Action (SIMPEA).” Psychological Review 125 (2): 245–269. doi:10.1037/rev0000090.

- Gawerc, M. 2016. “Constructing a Collective Identity across Conflict Lines: Joint Israeli-Palestinian Peace Movement Organizations.” Mobilization: An International Quarterly 21 (2): 193–212. doi:10.17813/1086-671X-20-2-193.

- Grabs, J., N. Langen, G. Maschkowski, and N. Schäpke. 2016. “Understanding Role Models for Change: A Multilevel Analysis of Success Factors of Grassroots Initiatives for Sustainable Consumption.” Journal of Cleaner Production 134: 98–111. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.10.061.

- Guest, G., E. Namey, and M. Mitchell. 2013. Collecting Qualitative Data: A Field Manual for Applied Research. London: Sage.

- Gustafsson, J. 2017. “Single Case Studies vs. Multiple Case Studies: A Comparative Study.” https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1064378/FULLTEXT01.pdf.

- Hammersley, M. 2003. “Recent Radical Criticism of Interview Studies: Any Implications for the Sociology of Education?” British Journal of Sociology of Education 24 (1): 119–126. doi:10.1080/01425690301906.

- Hogg, M., and E. Hardie. 1992. “Prototypicality, Conformity and Depersonalized Attraction: A Self-Categorization Analysis of Group Cohesiveness.” British Journal of Social Psychology 31 (1): 41–56. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8309.1992.tb00954.x.

- Hossain, M. 2016. “Grassroots Innovation: A Systematic Review of Two Decades of Research.” Journal of Cleaner Production 137: 973–981. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.07.140.

- Huddart Kennedy, E., S. Baumann, and J. Johnston. 2019. “Eating for Taste and Eating for Change: Ethical Consumption as a High-Status Practice.” Social Forces 98 (1): 381–402. doi:10.1093/sf/soy113.

- Kirwan, J., and D. Maye. 2013. “Food Security Framings within the UK and the Integration of Local Food Systems.” Journal of Rural Studies 29: 91–100. doi:10.1016/j.jrurstud.2012.03.002.

- Kneafsey, M., L. Venn, U. Schmutz, B. Bálint, L. Trenchard, T. Eyden-Woods, E. Bos, G. Sutton, and M. Blackett. 2013. “Short Food Supply Chains and Local Food Systems in the EU: A State of Play of their Socio-Economic Characteristics.” JRC Research Reports. https://EconPapers.repec.org/RePEc:ipt:iptwpa:jrc80420.

- Levkoe, C. 2011. “Towards a Transformative Food Politics.” Local Environment 16 (7): 687–705. doi:10.1080/13549839.2011.592182.

- Long, M., and D. Murray. 2013. “Ethical Consumption, Values Convergence/Divergence and Community Development.” Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics 26 (2): 351–375. doi:10.1007/s10806-012-9384-0.

- Maschkowski, G., N. Schäpke, J. Grabs, and N. Langen. 2015. “Learning from Co-Founders of Grassroots Initiatives: Personal Resilience, Transition, and Behavioral Change – A Salutogenic Approach.” In Resilience, Community Action and Social Transformation: People, Place, Practice, Power, Politics and Possibility in Transition, edited by T. Henfrey and G. Maschkowski, 65–84. Lisbon: Permanent Publications.

- Max-Neef, M. 2017. Development Ethics. London: Routledge.

- Middlemiss, L., and B. Parrish. 2010. “Building Capacity for Low-Carbon Communities: The Role of Grassroots Initiatives.” Energy Policy 38 (12): 7559–7566. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2009.07.003.

- Mock, M., I. Omann, C. Polzin, W. Spekkink, J. Schuler, V. Pandur, and A. Brizi, and A. Panno. 2019. “Something Inside Me Has Been Set in Motion’: Exploring the Psychological Wellbeing of People Engaged in Sustainability Initiatives.” Ecological Economics 160: 1–11. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2019.02.002.

- Moreno, F., and T. Malone. 2021. “The Role of Collective Food Identity in Local Food Demand.” Agricultural and Resource Economics Review 50 (1): 22–42. doi:10.1017/age.2020.9.

- Oh, J.-C., and S.-J. Yoon. 2014. “Theory-Based Approach to Factors Affecting Ethical Consumption.” International Journal of Consumer Studies 38 (3): 278–288. doi:10.1111/ijcs.12092.

- O’Neill, K. 2018. “Community Action, Government Support, and Historical Distance: Enabling Transformation or Neoliberal Inclusion?” In Resistance to the Neoliberal Agri-Food Regime: A Critical Analysis, edited by A. Bonanno and S. Wolf, 120–132. London: Routledge.

- Pitt, H., and M. Jones. 2016. “Scaling Up and Out as a Pathway for Food System Transitions.” Sustainability 8 (10): 1025. doi:10.3390/su8101025.

- Poeggel, K. 2022. “You Are Where You Eat: A Theoretical Perspective on Why Identity Matters in Local Food Groups.” Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems 6: 782556. doi:10.3389/fsufs.2022.782556.

- Pratt, M. 2014. “Social Identity Dynamics in Modern Organizations: An Organizational Psychology.” In Social Identity Processes in Organizational Contexts, edited by M. Hogg, 13–30. London: Taylor and Francis.

- Riessman, C. 2002. Narrative Analysis. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

- Rousseau, D., S. Sitkin, R. Burt, and C. Camerer. 1998. “Not So Different After All: A Cross-Discipline View of Trust.” Academy of Management Review 23 (3): 393–404. doi:10.5465/amr.1998.926617.

- Scoones, I., A. Stirling, D. Abrol, J. Atela, L. Charli-Joseph, H. Eakin, A. Ely, et al. 2020. “Transformations to Sustainability: Combining Structural, Systemic and Enabling Approaches.” Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability 42: 65–75. doi:10.1016/j.cosust.2019.12.004.

- Seyfang, G., and A. Smith. 2007. “Grassroots Innovations for Sustainable Development: Towards a New Research and Policy Agenda.” Environmental Politics 16 (4): 584–603. doi:10.1080/09644010701419121.

- Siggelkow, N. 2007. “Persuasion with Case Studies.” Academy of Management Journal 50 (1): 20–24. doi:10.5465/amj.2007.24160882.

- Soron, D. 2010. “Sustainability, Self-Identity and the Sociology of Consumption.” Sustainable Development 18 (3): 172–181. doi:10.1002/sd.457.

- Spradley, J. [1980] 2016. Participant Observation. Long Grove, IL: Waveland Press.

- Stets, J., and C. Biga. 2003. “Bringing Identity Theory into Environmental Sociology.” Sociological Theory 21 (4): 398–423. doi:10.1046/j.1467-9558.2003.00196.x.

- Stets, J., and P. Burke. 2000. “Identity Theory and Social Identity Theory.” Social Psychology Quarterly 63 (3): 224–237. doi:10.2307/2695870.

- Taylor, V., and N. Whittier. 1992. “Collective Identity in Social Movement Communities: Lesbian Feminist Mobilization.” In Frontiers in Social Movement Theory, edited by A. Morris and C. Mueller, 104–129. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.