Abstract

This article aims to uncover diverse perspectives regarding what sustainable consumption is and should be in the future. We draw upon and combine critical futures studies with recognitional justice. Futures studies enables inclusive approaches and divergence from current narratives of the future that are perceived as dominant. Recognitional justice allows for reflection upon who is usually not in the room when consumption futures are discussed. The article analyzes sustainable consumption-futures workshops held with four groups in Sweden. The first was with partners in a research program focusing on sustainable consumption. The second workshop enlisted elderly rural retirees, the third newly-arrived women from Syria and Eritrea, and the fourth high-income earners. A variety of traits in the discussions were noticeably influenced by the local context and backgrounds of the participants. Several issues brought up in the discussions dealt with issues that are on the political agenda in Sweden, such as circulating materials and more information and knowledge. There were also matters not on the political agenda such as eating a vegetarian diet, reducing consumption, and spending less time working. In addition, the newly-arrived women and, to some extent, the retirees, framed peace and ending the use of weapons as a vital element in sustainable consumption. This diversity and divergence highlights that, if it is to become relevant and inclusive, both research and policy need to recognize a multitude of perspectives and incorporate the distribution of power and critical futures perspectives to navigate a pathway toward consumption that is just and sustainable.

Introduction: transformation toward sustainable consumption

What might sustainable consumption be in the future? What changes should be made, what can sustainable consumption futures imply, and according to whom? This article explores such questions with the help of groups of Swedish respondents. We start out with the challenge of reconciling aspirations for a good life for all with the constraints of planetary boundaries and long-term sustainability (Di Giulio and Fuchs Citation2014; Jackson Citation2009). The consumption and production systems upon which countries such as Sweden rely have so far failed to deliver adequate outcomes but have instead resulted in many burdens on social and ecological systems. These impacts are also unevenly distributed across the globe and between different groups in society. For example, consumption by inhabitants of Sweden still results in approximately 10 tonnes of greenhouse-gas emissions (carbon-dioxide (CO2) equivalent) per person per year, even though the recommended level to avoid dangerous temperature increases is approximately 1.6 to <1 tonne per capita (e.g., Fauré et al. Citation2016; O’Neill et al. Citation2018). Hence, a just transition to sustainable consumption is much needed, and urgent.

But what is sustainable consumption, and what should it be in the future? Perspectives on sustainable consumption and narratives about it vary among contexts, countries, organizations, and so forth. Some narratives have become more dominant than others, such as the focus on efficient use of resources and access to information and awareness among consumers that is visible in Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 12 of Agenda 2030 (ensure sustainable consumption and production patterns). Green consumerism has also been promoted as a dominant focus according to Akenji (Citation2014). Such narratives may lead to choices and decisions in planning and policy that filter out or block other alternatives. In this way, some ideas or conceptions are also conveyed into the future and thus “colonize” future spaces (Milojević Citation2015).

But there are several additional framings of what sustainable consumption is, or should be in the future. Who becomes involved, and who has the power to influence which future to strive toward is still a relatively neglected issue in research, planning, and policy for transitions to sustainable consumption. Kantamaturapoj et al. (Citation2022) highlight a demand for more participatory, anticipatory, and imaginative policy developments, and argue that futures studies can play a positive role in shaping outcomes. In particular, critical futures studies may be important. Such an approach challenges existing structures and the colonization of the future by particular interest groups, suggests inclusive and equal futures, and includes an analysis of power and the meanings associated with future alternatives (Son Citation2015). This norm-critical approach allows the involved actors to diverge from current hegemonic ideas and images of the future (Goode and Godhe Citation2017). For example, futures can be consciously articulated based on feminist values to challenge dominant descriptions of the future that are perceived as male-biased (e.g., Gunnarsson-Östling, Svenfelt, and Höjer Citation2012). Likewise, scrutinizing and rethinking current consumption, as well as formulating participatory sustainable consumption futures, can be a way to construct a link between practice, provisioning, and policy in the present.

In this article, we draw upon and combine critical futures studies with environmental justice, particularly recognition and participation as elements of justice (Schlosberg Citation2004). Our aim is to uncover and analyze perspectives from different groups regarding what sustainable consumption is and what it should be in the future. The questions that have guided the research are: Who or what is perceived as missing when sustainable consumption is discussed? What ideas and visions of the future are discussed and formulated by different groups? What are the differences and similarities between groups? In what ways do the added perspectives challenge current assumptions about the future of consumption?

By bringing together futures studies and visioning with recognitional justice and sustainable consumption, we seek to contribute to the body of research that deals with planning and transitions to sustainable consumption and shed light on who gets to envision, influence, and “colonize” the future of consumption.

Sustainable consumption futures and recognition

Sustainable consumption research is inherently about the transition from unsustainable current practices. As such, it is implicitly about the future because it contains ideas that focus on new ways of being a consumer or progressing beyond a consumer-producer dichotomy. Issues such as consumers purchasing green products (Young et al. Citation2010), consumption based on the circular economy (Mylan, Holmes, and Paddock Citation2016), seeking to share and repair instead of buying new (Mont et al. Citation2020), or buying less and living simpler lives (Alcott Citation2008), working less (Neubert et al. Citation2022), eating plant-based food, and taking vacations via trains (Curtale, Larsson, and Nässén Citation2023) are options that frequently appear in research publications. Such solutions can be said to be an unarticulated view of the future because they are based on research that has focused attention on the assertion that technology alone cannot suffice for achieving climate targets – but that more profound changes are also needed (Lorek and Fuchs Citation2013; Lorek and Spangenberg Citation2014; Welch and Southerton Citation2019). Sustainable consumption can also concern social justice and empowerment, for example creating new structures and spaces for collaborative consumption (Jaeger-Erben, Rückert-John, and Schäfer Citation2015). But which groups are recognized as actors in research and processes of mainstreaming sustainable consumption? Such issues of recognition have thus far not gained attention in sustainable consumption research. Fuchs et al. (Citation2016, 306) argue that research on sustainable consumption and reductions in consumption “need to consider who sets the agenda, defines the rules and the narratives, selects the instruments of governance and their targets, and thus influences people’s behaviour, options, and their impacts.” The authors also argue that, so far, neither academia nor policy making have dealt with power relations in sustainable consumption, but rather have avoided confronting such challenging issues.

This is a research gap that this article aims to help to fill by addressing one aspect of power in transitions to sustainable consumption, namely the issue of recognitional justice. Recognitional justice – or recognition as grounded in the environmental justice field – is used here to guide the research design and as a basis for posing new questions in sustainable consumption research. Recognition concerns who or what is included, recognized, and respected as part of decision-making and political processes (Schlosberg Citation2004). According to Schlosberg (Citation2007), environmental justice is increasingly focusing on recognitional justice. Environmental justice is a pluralistic field that started out as a powerful movement protesting the unfair distribution of environmental burdens, mainly local pollution such as toxic waste and landfills (e.g., Bullard Citation2000). Environmental justice also concerns access to and the distribution of environmental goods, such as ecosystem services and resources (Chaudhary et al. Citation2018; Movik Citation2014).

Defining environmental justice is not easy because there are many possible definitions (Agyeman and Evans Citation2004). Several interlinked elements of environmental justice can be useful in the analysis of sustainable consumption: distributive justice (which concerns how environmental burdens and benefits are, or could be, distributed) (e.g., Dobson Citation1998; Meyer and Roser Citation2006), substantive justice (which centers on the right to live in a clean and healthy environment) (Agyeman Citation2005), procedural justice (which involves participation and meaningful involvement in processes and decision-making) (Agyeman Citation2005), and recognitive justice or recognition (Schlosberg Citation2004).

According to Schlosberg (Citation2004), building on work by the philosopher Iris Young (Citation1990), recognition does not replace distribution or participation; instead, these three are interlinked. Recognition is a foundation for participation and distribution, because if one is not recognized they cannot participate (Schlosberg Citation2004). Young (Citation1990) stresses the importance of differences between social groups – some privileged and some oppressed – and argues that such differences need to be acknowledged and addressed. Recognition is tied to social norms and social differences and needs to occur as much in the social, cultural, and symbolic realms as in the political/institutional realm, because recognition is difficult to distribute when compared to other goods or services (Schlosberg Citation2004). Recognition has been used to highlight the lack of acknowledgement accorded to global movements for environmental justice, but also within other research close to sustainable consumption. In these cases, the definition of recognition might focus on identifying interest groups and potential holders of rights in just transitions (Krawchenko and Gordon Citation2021), reversing the misrecognition of marginalized groups in energy justice (Mccauley and He Citation2018), or recognizing social differences in climate policymaking (Singleton Citation2022). Consumers and sustainable consumption have not often been the focus of an environmental justice perspective, although there are a few notable exceptions (Middlemiss Citation2010; Peleg-Mizrachi and Tal Citation2019; Seyfang and Paavola Citation2008). Recognition of a variety of actors in transition planning and research can help us to become aware of and integrate differences rather than dismiss them.

Envisioning futures

As with recognition, the terms visioning and visions have different meanings, but describe preferred or desired futures in one way or another (Börjeson et al. Citation2006; Milojević and Inayatullah Citation2015). Accordingly, futures studies and visioning address recognition, although not explicitly using that or related terms, such as recognitional justice. According to Eleonora Masini (Citation2002, 250), futures studies has both engaged and involved people in different circumstances to think about and “choose their own future rather than accept one chosen for them.” To exemplify this situation, Masini (Citation2002) writes about involving new generations in developing countries in futures studies during the 1980s. Exploring gendered or feminist futures (Gunnarsson-Östling, Svenfelt, and Höjer Citation2012) is also a kind of recognition. However, even in futures studies and visioning, women and other “Others” have not been sufficiently recognized and have not participated. As a result, future narratives/visions have tended to be colored by the values of dominant groups (Hudson and Rönnblom Citation2020).

Goode and Godhe (Citation2017) call for critical futures studies that examine values and assumptions to loosen the constraints around public debates and imaginings of possible futures and Wittmayer et al. (Citation2019) suggest that the strategic use of narratives of change, in a language suited to practitioners, can be picked up and appropriated or translated by the actors involved in these activities. Stories of alternative futures and narratives have proven to be especially beneficial in evoking imagination, guiding action, and dealing with uncertainty (Milojević and Inayatullah Citation2015). According to Elise Boulding (Citation1988), who builds on Fred Polak’s (Citation1973) theory of the image of the future as an agent of social change, creating and telling new stories or narratives about the future can become a powerful tool. Such new narratives may be able to challenge dominant ones. Narratives can be descriptive accounts of futures that extend beyond academic disciplines and can thus highlight the perspectives of groups involved in the visioning process (Hanger-Kopp, Lieu, and Nikas Citation2019).

Closely related to imagining/visualizing futures are social imaginaries, which have been described by Riedy and Waddock (Citation2022, 2) as how people collectively “see, sense, think and dream” the world and make changes in that world. Hence, new narratives and images can potentially create reflections upon and expectations of different futures and these can thus be discerned through creative visualization. Boulding (Citation1988) argued that visioning the future can both provide a tool for social change and help to move beyond thinking about obstacles. However, current deeply rooted culture, or the underlying assumptions, myths, and metaphors that form deep culture, might stand in the way of transitions. Hence, they need to be brought to the surface and changed, otherwise they may be transferred into the future and create the risk of perpetuating more of the same, instead of achieving the desired changes, as argued by Milojević and Izgarjan (Citation2014).

Visioning approaches have been used in several studies in the sustainability research arena over the last approximately two decades. There are many examples of visioning approaches in the backcasting literature and tradition (e.g., Anderson et al. Citation2008; Petheram, Stacey, and Fleming Citation2015; Sandström et al. Citation2016). We can understand backcasting as a type of visioning or as encompassing elements of visioning. Increasingly, backcasting and visioning studies are focused on sustainable consumption and sustainable lifestyles. Some examples include scenarios for sustainable lifestyles (Mont, Neuvonen, and Lähteenoja Citation2014), practice-oriented participatory, backcasting processes focused on home heating, personal washing, and eating (Doyle and Davies Citation2013), future options for meat consumption based on expert opinions (Vinnari and Tapio Citation2009), and elaboration of lifestyle scenarios grounded in participatory proposals for future lifestyles (Tasaki et al. Citation2016).

Discussing and inventing new narratives and images can potentially lead to reflection and shared meaning between people. Social imaginaries are a resource for both understanding the current world and creating representations of possible future states of the world (Moore and Milkoreit Citation2020). They “provide a shared sense of meaning, coherence, and orientation around highly complex issues” (Levy and Spicer Citation2013, 660) and may shape the mindsets or paradigms upon which people act. The relationship between visions or future narratives and action is difficult to trace, but there are many examples of projects in which visions have inspired both action and critique (e.g., Solinger, Fox, and Irani Citation2008). Hence, they can be essential aspects of transformation and succeed by creating a space for actors to challenge and deconstruct dominant assumptions and narratives about the future (e.g., Inayatullah Citation2008). Wittmayer et al. (Citation2019) have analyzed social innovation initiatives as narratives of change and as something that might replace dominant framings of the future. The authors understand such narratives of change as “sets of ideas, concepts, metaphors, discourses or storylines about societal transformation” (Wittmayer et al. Citation2019, 2). The narratives of change explored in this article are visions that were created during facilitated workshops. The discussions during the development of these visions constitute the main body of data analyzed in this article.

The ambition of the study presented here is to combine recognitional justice with the envisioning of futures and to apply these to sustainable consumption. We asked questions about which groups in society should be recognized during the process of creating narratives of change for the future of sustainable consumption and invited such groups to participate in this initiative. We did so to improve recognition in sustainable consumption contexts and to invite people who are usually not in the room when sustainable consumption futures are considered.

Study area and context

The study was performed in Sweden, a Nordic country that is often portrayed as a sustainable society, and ranks high on environmental performance indices (e.g., Wendling et al. Citation2018). If viewed from a consumption perspective, however, Swedish consumption per capita requires a large share of global ecological resources, and results in many negative social and environmental effects (e.g., Brown, Berglund, and Palm Citation2021). Hence, Sweden is a relevant case for exploring ideas about sustainable consumption, and very much highlights the dilemma between transforming consumption so that it remains within planetary boundaries, while simultaneously succeeding in maintaining quality of life.

The study was conducted within a larger research program on sustainable consumption. This initiative engages researchers from various scientific disciplines and societal partners from the public sector, business, and civil society. Its purpose is to enhance knowledge about how to enable sustainable consumption practices.

Selection and description of workshop groups

The selection of groups was intertwined with the workshops themselves, as a way of allowing recognitional justice to influence the research design and selection of groups. Therefore, in all the workshops participants were asked the question: “Who is not in the room?”, as we sought to establish which other groups in society ought to be recognized and asked for their visions of sustainable consumption. The question of who is not in the room but should be heard on issues of sustainable consumption generated a lot of activity in the workshops. There was a wide variety of suggestions including, for example, homeless people, people with diverse ethnic backgrounds, influencers, the super-rich, children, young people, people uninterested in the environment, right-wing politicians, poor people, and many more. The suggestions for groups included both those who were seen to be underrepresented – such as children, poor people, and minorities – as well as groups in power (including politicians, business leaders, and influencers) who, according to the workshop participants, need to discuss sustainable consumption issues.

The initial input was provided at the first workshop with the researchers and societal collaborators within the research program (henceforth “partners”). This assemblage included primarily influential and highly educated individuals. While this mode of organization allowed a large and relatively privileged – although not entirely homogeneous – group to contribute to the selection of the other potential workshop groups, the selection was broad and preliminary, since the subsequent groups were also asked the same question. The suggestions were not used directly to recruit groups; instead, the responses enabled us to identify various aspects that could be used to search for participants for subsequent workshops, such as age, income, and urban/rural background. Based on these aspects we identified three additional groups: 1) retired elderly people in a rural municipality (“retired”), 2) younger women newly arrived in Sweden as refugees living in suburbs in a metropolitan region (“newly-arrived”), and 3) middle-aged people with high incomes living in urban areas in a metropolitan region (“high-income”) (see ). To recruit respondents from these groups, we used personal contacts and snowballing, i.e., contacts were requested to ask/recruit relevant participants.

Table 1. Description of the four workshops.

Of the 41 participants in the first workshop (see ), half were researchers and the other half partners of the research program from Swedish companies, civil society organizations, municipalities, and national authorities. The participants came from across the country, from the north to the south. The nine participants in the second workshop were retired and lived in the small rural municipality of Ljusdal, which has 19,000 inhabitants. The eight participants in the third workshop were all women in the age group 25–40, and they were all so-called “newly-arrived” refugees. This group comprised people who have been granted residence permits and have a two-year establishment plan, during which they learn Swedish and apply for employment. This workshop was held in Arabic. The women lived in suburbs north of Stockholm. The five participants in the fourth workshop were people with high incomes, defined as more than one million SEK per year (approximately US$90,000). They all held influential and established positions in society/business and lived in Stockholm or in the vicinity of the city.

Visioning approach

The visioning approach builds on the ideas of Boulding (Citation1988) and on the workshop design of several backcasting studies (e.g., Carlsson-Kanyama et al. Citation2008; Kok et al. Citation2011; Svenfelt, Engström, and Svane Citation2011). Within this approach, participants are led through a process of discussing and envisioning desirable futures. We organized and facilitated four workshops to generate visions for sustainable consumption in 2030 with the aim being to explore different perceptions of sustainable consumption expressed as future visions.

Each workshop lasted approximately three hours. The first author and a colleague facilitated the partner workshop, while the second and third authors participated. In the following three workshops, the first and second authors took turns facilitating and assisting. The workshops were structured at the beginning of the session, and later completely open, allowing the participants to discuss and create visions among themselves while the facilitators left the room. Each workshop began with a presentation to introduce visioning, with examples of visions from related sustainability issues, but not concerning sustainable consumption. The introduction also included one official definition of sustainable consumption, from the United Nations definition of SDG 12, to introduce the topic of sustainable consumption without overly influencing the participants.

The structured part then continued with the focus question: “What elements do you think sustainable consumption should contain?” The participants’ ideas were then individually written down on post-it notes and they also voted for which of these elements they considered most important and for the ones that they did not think were very important.

During the unstructured part, participants were instructed to pick a maximum of ten post-it notes with elements they wished to use as a basis for creating a joint vision for sustainable consumption in 2030. They were given just a few instructions and were left to discuss and use their own creativity. The facilitators returned to the groups on several occasions and asked if they needed help. All the workshops were recorded and transcribed, but not all parts of the first workshop (see ).

At the end of the sessions, the groups reported back to explain their vision, and reflected upon the visioning experience.

Data and analysis

The data that we gathered consisted of the elements generated during the workshops, the visions that were created, and the transcripts of the discussions and presentations. The partner group is clearly overrepresented in terms of number of participants. It is not, however, overrepresented in the analyzed data because during this particular workshop we recorded and transcribed only the presentations of the visions while in the other three workshops we did so for the whole session (see ).

The transcripts were compiled, compared, and analyzed for similarities and differences, with the objective of understanding the participants’ reasoning about sustainable consumption futures. All data were entered into NVivo, and we used this qualitative data-analysis software as an aid for organizing and examining the transcripts. The coding and analysis were undertaken by the first author. In NVivo, the transcripts were read and coded and the coded text was then read through to find themes that had been discussed in more than one group. These themes were written up, and we included some illustrative quotes from the participants. The themes are not exhaustive, but constitute a selection of the discussions, nor are they discrete, but overlap in several respects.

Results

The groups’ visions of sustainable consumption

During the first, structured, part of all the workshops, participants individually generated elements that they considered to be vital aspects of sustainable consumption. This brainstorming generated over 100 different suggestions of a wide variety and ranged over many topics. For example, in the newly-arrived group, the elements “education about sustainable consumption” and “don’t throw away materials and products that someone else can use” were brought up. In the partner group, two of the examples were “products and services are produced under just working conditions” and “sustainable alternatives are available and affordable to everyone.” The different groups each chose approximately 10–15 different elements upon which to build their visions.

Most of the visions were expressed as text though one was presented in the form of a poem. Some of the visions were combined with a drawing, and one of the partner groups role-played their vision. highlights the translated vision of one of the six groups in the partner workshop and the three visions of the other three groups. The visions from the different groups have quite different forms, content, and perspectives. The actual visions were only a small part of the outcomes of the workshops; rather, the discussions during the process of arriving at the visions, as well as the discussions during the presentations of the visions, were the main outcome, and the themes of these discussions are described in the next sections.

Table 2. One of the created visions from each of the workshops.

Themes brought up during the discussions

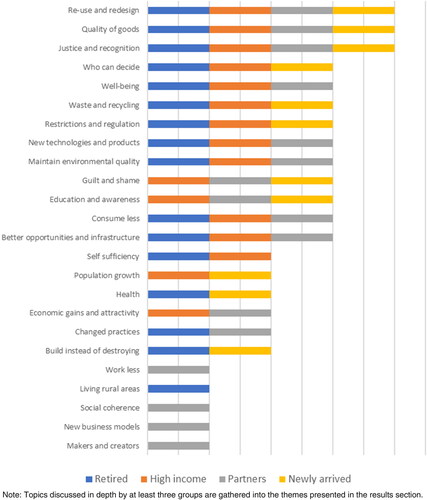

Although the different groups all received the same instructions and the same introduction to the subject, they interpreted sustainable consumption in diverse ways, and emphasized different elements. For example, two of the groups (retired and high-income) discussed local self-sufficiency, buying both food and other goods locally, as important elements of future sustainable consumption but the other groups did not consider these elements. The high-income group and the newly-arrived group both brought up guilt and shame, the former in the sense that they felt guilty about their consumption, for instance flying, or wanted to question whether they should have to feel guilty, because perhaps this guilt is focused on the wrong thing. For example, instead of thinking about the details of consumption, buying 1,000 square meters of solar panels might be a better contribution, one participant argued. The latter group discussed the fact that other people living in Sweden think so much about the environment and tell them to sort their waste or bicycle to kindergarten, making them feel ashamed. Flying less and eating plant-based foods, instead of animal-based, were brought up several times in the partner workshop, but less so or not at all in the other groups. Several themes were only highlighted in one or two groups, while others were raised in more or all groups (see ). The following sections are descriptions of the themes that were developed in more detail by at least three of the groups.

Power over decisions

Some of the discussions touched upon power issues and who can influence development. The retired group discussed the idea that what the individual does and decides has little significance and that individuals are more or less powerless. “We try to do what we can, but it doesn’t seem to help,” one participant said. It is the great powers and big finance that rule, and we are too small, they asserted. The high-income group argued that regulation should increase, because it would probably be difficult to solve the problems based purely on everyone’s good will and knowledge. For participants in the newly-arrived group, faith also played an important role in this matter, and hence God is seen as having power.

In the high-income, retired, and newly-arrived groups, people were mostly discussed as consumers who have little control, while in the partner groups people were also described as makers and creators. Several of the visions in the partner workshop envisioned individuals as more than consumers, and primarily as citizens, who play an active role in the transition to sustainable consumption.

Justice and recognition

Several of the visions, and the discussions about them, contained elements related to justice in different ways. In the retired group, justice was mentioned at both the local level, between different groups in Sweden, and globally among different countries. The international issue concerned drinking water, and that everyone should have sufficient access. The more local issue concerned injustices in climate transition regarding opportunities for people living in rural areas compared to urban, particularly concerning mobility. “I don’t think it’s taken into consideration that there are so many people living in rural areas. Everything starts out from the big cities, but you must solve this because you can’t live out here unless you drive a car,” said one of the participants.

In the high-income workshop, justice was also brought up at both global and local scales. On an international scale, it had to do with the consumption of goods, and how this affects the conditions for people who work in production. Justice was also discussed regarding who has the ability to buy quality goods, and that there should be affordable quality goods. The group discussed that not everyone can pay 4,000 SEK (approximately US$350) for a pair of quality shoes, although they will last longer, and it would be much cheaper for a family to do so in the long term. It was also debated whether it is ethical to buy your way out of responsibility, and one example discussed was compensating for greenhouse-gas emissions for flying. One participant argued that it would be reasonable to buy a thousand acres of forest in the Amazon to compensate for flying, while another questioned whether one can buy themselves free from responsibility for climate impact, and asked “What gives us the right to consume unsustainably just because we [can]?”

In the partner workshop, justice between groups of people was discussed in most of the six different subgroups and also highlighted in their visions. One group stated that everyone should be given the means to live a good and sustainable life, and several other groups said that social justice and equity must be considered. Intragenerational justice was discussed; for example, one group stated that resources on Earth, within planetary boundaries, should be divided equally among the global population. A discussion in the partner workshop arose in relation to this issue, and one participant raised the point that this could be perceived as “too communist” and perhaps, another participant argued, different people have various needs and therefore the distribution should not necessarily be equal. Cancer patients, for example, may need more resources, this person continued. Another argument that was brought up against dividing resources equally is that the Western world has a historical debt due to its previous consumption, and that this would mean that perhaps we must consume even less than other countries.

Intergenerational issues were also addressed in both the partner and the newly-arrived groups. It was argued that resources should also be divided in time “so that future generations will also have theirs, just as much, and not be disadvantaged” (partner group), and that a person must think about future generations “so that he does not take advantage of these resources in taking everything and leave nothing to those who come after him” (newly-arrived group). This means that future generations are recognized as recipients of justice. In addition, both the partners and newly arrived brought up nature itself as a recipient of justice. For example, in the partner workshop, this was framed as sustainable consumption being fair across species, so that animals also have rights. In the newly-arrived group, this perspective was brought up as “respect for the rights of animals and trees,” and regarding meat consumption, with many in this group believing that it is wrong to kill animals.

Waste management and recycling of materials

Waste management and recycling were discussed in all the groups except the program partners, although circular flows were briefly mentioned in their visions. Recycling and the handling of waste seemed important elements in the other groups, mainly because several participants were confused about how to recycle due to lack of information and reliable facts. One participant in the high-income group questioned if it is right to focus on recycling and reflected that this might be compared to “straining at a gnat but swallowing a camel,” and “we sort glass bottles and then we’re the people who fly the most per capita.” Hence, this discussion was focused on what are the most efficient actions to achieve sustainable consumption.

In the newly-arrived group, cultural differences as well as difficulties in knowing what is right regarding recycling were reflected upon. Several had difficulties understanding the waste-recycling system and what to do and not to do. Several participants had been taught by their neighbors and children how to compost and recycle. Participants in this group wanted courses to communicate the concept of sustainable consumption and the importance of recycling.

In the retired group, the discussion was more focused on avoiding water and food waste. One of the participants noted that a lot of resources could be saved if water and food were not wasted. Another participant said that the younger generations seem to throw away a lot of food, and that this needs to be avoided.

Consume less

To consume less and be satisfied with less – in other words, sufficiency – was brought up most often in the partner group. Among these participants, there were a lot of discussions about consuming less, and how the link between status and owning things and shopping would become broken in the future. One group’s vision expressed this as “by 2030, all people will have access to attractive, welcoming, and consumption-free meeting places.” Exchanges about consuming less were often paired with statements and assertions about working less. For example, one participant said, “We talked a lot about exactly that, to consume less is also pretty much linked to us working less, that there is a clear connection between them.” However, within the same group, there were discussions about whether there actually is a direct link between working less and consuming less. By contrast, one participant argued, “If everyone works less then fewer goods and services are actually produced and in fact you then consume less, there is less to buy.” Working less did not come up in the discussions in any of the other groups.

In the high-income group, consuming less was brought up as an issue to counteract the fact that people in producing countries are paid too little. “Isn’t a basic problem that there are one billion people in India and China who are so incredibly disadvantaged and who work for nothing because there is incredible consumption? The consumption that must decrease, we must stop shopping.” This statement was contradicted by other participants, however, who argued that these are the people who will consume more in the future and that this is a large problem. “In India you have, after all, a country that’s booming, all of them should have refrigerators, and dishwashers and cars and that’s, after all, that’s the nightmare.”

In the retired and newly-arrived groups, consuming less was touched upon regarding food waste, in that large packages result in buying too much food that eventually turns bad, and that smaller packages would encourage people to buy less. In both these groups, less consumption (and production) of weapons also came up. In the retired group, one participant argued for stopping the arms race, discontinuing all weapons production, and using the money for welfare. The newly-arrived group discussed this issue a lot, and it became a vital part of their vision for sustainable consumption. It was emphasized that the problems of climate and the environment that the world is going through today are connected to products, and “the most important and worst of these products are the weapons factories.” Another participant argued that weapons contain materials that are destructive and deadly to humans, as well as to animals and plants, and that they affect the soil, water, air, atmosphere, and resources. Another said: “If the arms factories are stopped, human beings will feel safe and stable, as well as preventing weapons from destroying the environment and the atmosphere.”

Awareness, education, and opportunities

Particularly in the high-income group, there was a lot of frustration about not knowing what is the right thing to do when it comes to sustainable consumption, and that what is perceived as right changes all the time. To be able to achieve sustainable consumption, participants in the high-income group desired clear signals and information about what is sustainable. One option that was brought up was individual goals and how well, or how poorly, they are fulfilled. “I would like to see my quota. So that I know my consumption points per week, how many points I have to spend each week and then see if I go above or below the target, so to speak.” The same person also noted, “I would be very surprised if this [going below the target] can happen if you live as a normal person who doesn’t live in a tent.” The group eventually agreed that knowledge is a way forward, and a softer way (than regulation) to achieve sustainable consumption. Also, in the newly-arrived workshop, a lot of the discussion revolved around raising awareness and education, specifically in the form of courses to introduce the concept of sustainable consumption. In the other two groups, this theme was weak, or lacking.

However, discussions were not only about information and awareness, but also about opportunities. For example, in the retired group, where mobility was discussed at great length, it was suggested that public transport should have higher frequency and cost nothing. The high-income group also discussed prerequisites for shopping sustainably, arguing that alternatives should become available.

Discussion

Colonizing and decolonizing the future

This article has explored co-created visions of sustainable consumption futures as a way of opening space for additional perspectives and stories about consumption in the future. Formulating desirable visions, as these different groups sought to do, can be a way of telling new stories about the future. In that sense, visioning is a kind of storytelling. In this section, we discuss the stories told by the different groups at an overarching level. We see their stories as told both through the articulated visions (see ) and how the future was discussed by the groups. Stories have been said to “knit time-space relations in a coherent articulation of events that occur at a particular place and time” (Borges Citation2016, 25). Stories that connect elements into some form of coherent whole can not only help to make sense of the past, but also assist in preparing for the future and becoming oriented toward the future (van Hulst Citation2012). Storytelling has in particular gained a lot of attention in planning. For example, Ortiz (Citation2023) discussed the role of storytelling in decolonizing the reproduction of Western thought and white supremacy in planning and acknowledging alternative ways of knowing and being in planning. Can this way of thinking also apply to stories told about sustainable consumption?

In an article regarding the Internet and digitalization, Dufva, Ikäheimo, and Dufva (Citation2020) argued that many current problems stem from previous images/visions of the future, which have led to a “colonization of the future” and resulted in a narrow, hegemonic description of the future. Colonization here is interpreted in a broad sense, meaning that some images or ideas of the future become dominant and hence these ideas come to occupy space in planning for, imagining, and anticipating future spaces (Milojević Citation2015). To remedy this, Inayatullah (Citation2008) argues, creating spaces for working with alternative futures/visions can aid in decolonizing the future by challenging concepts of what we think we might want the future to be like, and deconstructing dominant or hidden narratives. In some contexts, decolonization primarily refers to decolonizing the reproduction of Western thought and white supremacy (Ortiz Citation2023), but the idea of decolonizing the future can also be transferred to other areas where particular expectations of the future have become hegemonic. Some of the problems related to the sustainability of consumption might also be the result of a similar colonization. For example, the idea that increased production, consumption, and economic growth have to be maintained as a path toward welfare and wealth has become deeply rooted (see for example Schmelzer Citation2015). Hence, in planning, policy, and research tied to consumption, some images or ideas of the future become dominant and hence these ideas colonize “future spaces.” If the future is colonized by dominant past and current ideas and narratives, this creates a major flaw regarding inclusion and influence. The newly-arrived, high-income, and retired groups were all, for different reasons, perceived as being left out of the discussion, and the recognition of their narratives provides the addition of new perspectives and is a step toward decolonization, or even recolonization.

This is not only relevant for societal development in general, but also for research environments, since knowledge can be sought to inform or aim for transformation, with the ambition of changing the path that we are currently following. In this sense, research on sustainable consumption is colonizing the future and would benefit from considering more and diverse narratives. This could be done through reflecting upon recognitional justice and adapting the research design accordingly.

Several authors have used the participatory creation of future visions and future narratives as a way of critically analyzing and challenging norms of what the future can and should be. For instance, Sandström et al. (Citation2016) used visioning to explore different agendas for the future of forests and to raise awareness of tensions between different perspectives. The authors argued that their study “may facilitate current policy processes and potentially break current deadlocks in the debate on the future of forests.” Although not positioning themselves in the futures studies or storytelling fields (but “futuring” and “storying”), Jensen, Oldin, and Andersen (Citation2022) organized a workshop to co-create alternative narratives of traveling in the future and concluded that the workshop format equipped participants to explore and share a greater variety of climate futures.

The visions that were created by the participants in the visioning workshops reported in this article are not all complete stories about the future, as they do not connect elements into a coherent narrative. Regardless of the form of the visions, they can diversify the available perspectives on sustainable consumption in the future and thereby also reveal tensions and assumptions in sustainable consumption discussions, such as the tensions regarding who has power over decision-making.

Another transformative futures tool is causal layered analysis (CLA). This technique suggests specific processes and steps that can create spaces for generating alternative futures and for enabling awareness of different layers of discourse and assumptions about the future (Milojević Citation2015). A key proponent of this approach argues that CLA both confronts and works with power, through exposing existing power relations regarding colonizing the future, and also because the processes can reveal tensions and power struggles and challenge dominant assumptions. In this article, we have built on theories of recognition. We asked which groups in society should be recognized during processes of colonizing or decolonizing the future of sustainable consumption, and then specifically invited such groups to participate in our project. This can be considered a one-dimensional approach to power that does not permit the analysis of more complex power relations as compared, for example, to CLA. While acknowledging this drawback, we contend that the work still contributes to diversifying narratives of consumption in the future and thus sheds light on tensions between different perspectives. Nevertheless, research on and analyses of power and power relations related to sustainable consumption are scarce, and more initiatives would be welcome. For example, there can be power struggles between and within groups and contexts, and potential tensions that diverging visions reveal, which may need to be addressed.

Challenging or re-affirming the norm?

Futures studies tools can be used to challenge current hegemonic images of the future. For example, feminist visions have been called for to generate new and bold visions of the future, and even to form a desirable future (see e.g., Gunnarsson-Östling Citation2011). This is not to imply that diverging from what is considered the norm means the same thing to different people. Furthermore, what the norm, or dominant, view is can be different in various locations, contexts, and groups. The discussions and visions of the groups in this study illustrate this perspective. They are very different, and there were sometimes also divisions within the groups during the workshops that are relevant but perhaps not visible in the final visions. Furthermore, some aspects of the visions may align with what can be considered to be the norm, while other aspects of the content can be construed as norm-critical because they diverge from the current state of affairs.

For example, in the visions and discussions in the partner group, issues like veganism, decreased consumption volumes, working less, and sharing/renting goods were frequently discussed, which can be noticed in the visions. Many of the ideas from the partner/researcher workshop could be considered quite radical, and, if such ideas were to be realized, they could substantially affect people’s everyday lives. At the same time, the visions align with the norm within this particular group, as the participants from universities, businesses, government authorities, and civil society organizations are at the forefront of promoting sustainable consumption. It is interesting to note that no arguments for economic growth or increased consumption were brought up in the discussion, although several companies that depend upon product and service sales were present. Possibly such an argument would have been difficult to raise, as it would have challenged the norm in this specific context.

The retired, high-income, and newly-arrived groups did not propose any major lifestyle changes. In some ways, the discussions and visions here aligned more to what could be interpreted as the current norm when comparing them to common approaches in contemporary policy and planning in Sweden. For example, the highlighting of more and better information and knowledge to be able to make the right choice corresponds to often-used policy strategies. Another measure discussed in the groups was the sorting of waste, which is also in line with past and current Swedish policy. So, in some senses, the visions reflect current policy and norms. By contrast, the retired group also included localization and buying locally in their vision. A localized system is far from the current situation in Sweden, which engages in massive international trade, and is perhaps at odds with current norms. Furthermore, two of these groups discussed peace and the end of weapons as important elements of sustainable consumption. The framing of the consumption of materials of war in the context of sustainable consumption could be said to challenge the norm of what is considered to be sustainable consumption. This highlights the importance of researchers, and other actors working with measures for sustainable consumption, to venture outside of their own sphere when looking for answers and constructing relevant and effective measures.

Overall, several of the elements brought up in the visions and discussions dealt primarily with issues that are already on the political agenda in Sweden; for example, waste management, circulating materials, and providing information and knowledge about sustainable consumption to enable consumers to make informed and wise decisions. However, there were also elements relating to reduced consumption. Issues such as ceasing weapons production, stopping/reducing flying, eating vegetarian, decreasing material consumption, and spending less time working are not on the political agenda. Two different positions/frames can be discerned here, one focusing on efficiency measures similar to a circular economy and the other focusing more on reduced consumption and improved well-being.

This dichotomy between efficiency and sufficiency has been identified in previous research, for example weak and strong sustainable consumption (Fuchs and Lorek Citation2005) or a reformist vs. revolutionary approach, the latter offering a critique of consumer society (Geels and Schot Citation2007). Current attempts to shift toward sustainable consumption are failing to make significant advancements, according to several authors who have measured consumption-related environmental impacts (e.g., Lettenmeier, Liedtke, and Rohn Citation2014; Schandl et al. Citation2018). Some of the gains from efficiency-related measures, such as enhanced technology, have regrettably been eaten up by increases in consumption (e.g., Hertwich Citation2005; Ottelin, Cetinay, and Behrens Citation2020). Hence, reductions in consumption also have to be more widely addressed. But reductions for whom, and how? Wiedmann et al. (Citation2020) concluded that consumption by affluent households is the most important factor and what most accelerates increases in environmental and social impacts globally.

The groups in our visioning workshops all came from quite different backgrounds and socioeconomic contexts. The participants in the high-income groups all have a high income, and the participants in the partner group are also quite privileged. And although we did not ask about income, these two groups are well-educated, and have at least some opportunities to influence the political agenda. Since power and recognition differ between different groups in society, crucial questions to consider are: Who stands to benefit from different approaches? Who should be responsible for making the necessary adjustments? What are they adjusting from, and to?

Power and recognition

Between the visioning groups in this study, some have more power than others. For example, the partner group is privileged, well-educated, and has opportunities to influence the political agenda and which options are discussed. From that perspective, the fact that the discussions and visions in this group were quite different from those of the other groups may present a problem. If future visions and the associated suggestions for solutions and measures are too far removed from the conditions under which, and among whom, sustainable transitions are to take place, then it may be difficult for such solutions and measures to become relevant, accepted, and inclusive. How can they then possibly support sustainable consumption practices to become mainstream? There is a risk that if imaginaries/stories of future sustainable consumption are only told by the privileged and well-educated, those with the ability to influence the political agenda, then these stories are what take precedence and become hegemonic, without recognizing the perspectives of many of the groups who are expected to adopt the associated changes in consumption patterns.

Another group that was not directly represented among the workshop participants is non-humans. Despite the inseparability of humans and non-humans (Twine Citation2020), most non-humans are made invisible or commodified in hegemonic discourses on sustainability (Arcari Citation2017; Arcari, Probyn-Rapsey, and Singer Citation2021). However, two of the workshop groups (newly arrived and partners) did discuss the rights of animals and nature, arguably demonstrating recognition of non-humans in some capacity. There are real-world examples of non-human recognition, such as granting legal rights to nature (Higgins Citation2015; Page and Pelizzon Citation2022). One example of the latter is how the Whanganui tribe in New Zealand successfully championed the legal rights equal to humans of the Whanganui River (de Jong Citation2017). Indeed, one way to address the recognition of non-humans could be through representatives, which Boström and Uggla (Citation2016) argue is necessary, since non-humans cannot speak for themselves. It remains important, though, to keep a critical eye on such representatives – of humans and non-humans – including who they are and how they justify holding such positions of power (Boström and Uggla Citation2016).

Accordingly, one way forward may be enhanced recognition and participation. Kirveennummi, Mäkelä, and Saarimaa (Citation2017) concluded from their sustainable food-futures study that consumers’ own ideas about how to balance different perspectives need more attention during the political process. Efforts to open space for new narratives and images of the future of consumption, as interpreted by different societal groups, when analyzing or planning inclusive transformation, could advance sustainable consumption research and policy. However, this ought not to imply an increased burden of responsibility on individuals (Evans, Welch, and Swaffield Citation2017), which, arguably, is suggested by the general emphasis by the newly-arrived, retired, and high-income groups on information and knowledge to be able to make the right choice. The ability of individuals to shape their own lives within the existing structures and conditions is limited by boundaries set by various factors such as laws, regulations, income levels, access to a diverse range of choices, and personal circumstances and concerns. Even though individuals have the power to influence and alter these boundaries in multiple ways, for example by participating in elections, voting “with the fork,” or being active in sustainability transition movements, it is essential to acknowledge that such participation cannot be solely relied upon for this transformation to occur. This means that not all actors have the necessary capacity (i.e., agency, according to Schlosser Citation2015) to participate in or influence the debate. Dieterle (Citation2022) argues that very few people can actually vote with their fork/consume ethically because it requires not being misled by marketing, spending time to understand production practices, being strong-willed, and having the financial means and access to food that aligns with the values you want to “vote” for.

It is imperative that individuals” have the power to actively participate in shaping their societies, ensuring that necessary conditions are met, and opportunities are accessible to all. However, since opportunities and agency are not equally distributed, structural factors external to individuals are crucial. If consumption practices are to be reconfigured and new sustainable ones developed, such structural factors need to be taken into consideration when planning or working toward change (Sahakian and Wilhite Citation2014; Watson Citation2017). Goode and Godhe (Citation2017) argue that critical futures studies should work against powerful interests that narrow and monopolize our futural imagination, and particularly institutions that set society’s agendas and exhibit the most power over public discourse about the future. While we have argued that the newly-arrived, retired, and high-income groups conform in some ways to a normative approach to framing the locus and responsibility for change in public discourse and policy, perhaps none of the visions discussed here actually represent the norm or mainstream discourse. Politicians and other actors who do set the agenda, and can influence developments more directly, were not present.

Moreover, this study only includes four different groups in a Swedish context. Sweden is a Western country with specific conditions. Most notably, it is an affluent society, with a mostly temperate climate, a sparse population, and an abundance of natural resources compared to many other nations. For a just transition to sustainable consumption, it would be valuable to recognize more perspectives from all around the world, and particularly perhaps from less prosperous societies. Future research could strive to bring such perspectives to light, otherwise we must ask: Should we consider the issues brought onto the agenda to be for the privileged by the privileged? If so, can they possibly support efforts to regularize sustainable consumption practices?

Conclusion

For sustainable consumption to become mainstream, important questions include: Who gets to participate and be recognized? Who is supposed to alter their practices? Who is responsible? Regardless of who is seen as representing the norm, power balances and recognition when discussing and making the future of consumption become important.

Visioning can be, or become, an important tool for transitioning to sustainable consumption but, when exploring paths toward sustainable consumption futures, there is also the question of who gets to decide, influence, and “colonize” these futures. Through visioning workshops and other co-production tools with an explicit emphasis on recognitional justice, solutions can become based on other groups’ perspectives, and not just those of the people with power and an arena to influence. If future studies and visions are employed, the dominant assumptions about what the future should be, can be challenged. Existing power structures and, perhaps, interests that lead toward unsustainable developments can also be questioned. Of course, there will be narratives that do not prioritize sustainable consumption, potentially overlooking the urgent need for transformation. Such narratives need to be contested and competed with, in processes that harness hope, imagination and ambition for change, emphasizing inclusivity to represent diverse voices. Amid the current dystopian atmosphere and unarticulated ambitions, shared discussions about shaping the future can infuse a more positive force. Opening up the dialogue can counter the monopolization of the discourse by specific interests, thereby enhancing the ability to mitigate the worst scenarios.

Another important outcome of this study is the acknowledgement that research activities also need to develop an understanding of the perspectives of those who are “not in the room,” in order to generate more relevant and inclusive suggestions for enabling sustainable consumption. We have shown how a recognitional justice lens can enrich visioning work in sustainable consumption research by including such perspectives.

The stories, ideas, and metaphors resulting from collaborative visioning and creating new narratives can frame current problems, identifying matches and clashes between visions or perspectives and what might be needed to achieve sustainable consumption, as well as opening up space for alternative, inclusive and sustainable futures.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank all the participants in the visioning groups for their time and engagement in developing their future visions. We also express our appreciation to Annika Carlsson-Kanyama for help when planning the project and to Brita Hermelin, Ivana Milojević, and two anonymous reviewers for valuable comments on earlier drafts of the article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Agyeman, J. 2005. Sustainable Communities and the Challenge of Environmental Justice. New York: New York University Press.

- Agyeman, J., and B. Evans. 2004. “‘Just Sustainability’: The Emerging Discourse of Environmental Justice in Britain?” The Geographical Journal 170 (2): 1–17. doi:10.1111/j.0016-7398.2004.00117.x.

- Akenji, L. 2014. “Consumer Scapegoatism and Limits to Green Consumerism.” Journal of Cleaner Production 63: 13–23. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2013.05.022.

- Alcott, B. 2008. “The Sufficiency Strategy: Would Rich-World Frugality Lower Environmental Impact?” Ecological Economics 64 (4): 770–786. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2007.04.015.

- Anderson, K., S. Mander, A. Bows, S. Shackley, P. Agnolucci, and P. Ekins. 2008. “The Tyndall Decarbonization Scenarios – Part II: Scenarios for a 60% CO2 Reduction in the UK.” Energy Policy 36 (10): 3764–3773. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2008.06.002.

- Arcari, P. 2017. “Normalised, Human-Centric Discourses of Meat and Animals in Climate Change, Sustainability and Food Security Literature.” Agriculture and Human Values 34 (1): 69–86. doi:10.1007/s10460-016-9697-0.

- Arcari, P., F. Probyn-Rapsey, and H. Singer. 2021. “Where Species Don’t Meet: Invisibilized Animals, Urban Nature and City Limits.” Environment and Planning E: Nature and Space 4 (3): 940–965. doi:10.1177/2514848620939870.

- Borges, L. A. 2016. “Stories of Pasts and Futures in Planning.” PhD dissertation. KTH – Royal Institute of Technology, Stockholm.

- Börjeson, L., M. Höjer, K.-H. Dreborg, T. Ekvall, and G. Finnveden. 2006. “Scenario Types and Techniques: Towards a User’s Guide.” Futures 38 (7): 723–739. doi:10.1016/j.futures.2005.12.002.

- Boström, M., and Y. Uggla. 2016. “A Sociology of Environmental Representation.” Environmental Sociology 2 (4): 355–364. doi:10.1080/23251042.2016.1213611.

- Boulding, E. 1988. “Image and Action in Peace Building.” Journal of Social Issues 44 (2): 17–37. doi:10.1111/j.1540-4560.1988.tb02061.x.

- Brown, N., M. Berglund, and V. Palm. 2021. “Potential Environmental and Socioeconomic Effects Overseas Due to the Mainstreaming of Sustainability-Motivated Niche Practices in Sweden.” Mistra Sustainable Consumption Report 1:8. Stockholm: KTH – Royal Institute of Technology.

- Bullard, R. 2000. Dumping in Dixie: Race, Class, and Environmental Quality. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

- Carlsson-Kanyama, A., K.-H. Dreborg, H. Moll, and D. Padovan. 2008. “Participative Backcasting: A Tool for Involving Stakeholders in Local Sustainability Planning.” Futures 40 (1): 34–46. doi:10.1016/j.futures.2007.06.001.

- Chaudhary, S., A. Mcgregor, D. Houston, and N. Chettri. 2018. “Environmental Justice and Ecosystem Services: A Disaggregated Analysis of Community Access to Forest Benefits in Nepal.” Ecosystem Services 29: 99–115. doi:10.1016/j.ecoser.2017.10.020.

- Curtale, R., J. Larsson, and J. Nässén. 2023. “Understanding Preferences for Night Trains and Their Potential to Replace Flights in Europe: The Case of Sweden.” Tourism Management Perspectives 47: 101115. doi:10.1016/j.tmp.2023.101115.

- de Jong, E. 2017. “New Zealand River Granted Same Legal Rights as Human Being.” The Guardian, March 16. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/mar/16/new-zealand-river-granted-same-legal-rights-as-human-being

- Di Giulio, A., and D. Fuchs. 2014. “Sustainable Consumption Corridors: Concept, Objections, and Responses.” GAIA 23 (3): 184–192. doi:10.14512/gaia.23.S1.6.

- Dieterle, J. 2022. “Agency and Autonomy in Food Choice: Can We Really Vote with Our Forks?” Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics 35 (1): 1–15. doi:10.1007/s10806-022-09878-3.

- Dobson, A. 1998. Justice and the Environment. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Doyle, R., and A. Davies. 2013. “Towards Sustainable Household Consumption: Exploring a Practice Oriented, Participatory Backcasting Approach for Sustainable Home Heating Practices in Ireland.” Journal of Cleaner Production 48: 260–271. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2012.12.015.

- Dufva, M., H. Ikäheimo, and T. Dufva. 2020. “Grasping the Tensions Affecting the Futures of Internet.” Journal of Futures Studies 24 (4): 51–60. doi:10.6531/JFS.202006_24(4).0005.

- Evans, D., D. Welch, and J. Swaffield. 2017. “Constructing and Mobilizing ‘The Consumer’: Responsibility, Consumption and the Politics of Sustainability.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 49 (6): 1396–1412. doi:10.1177/0308518X17694030.

- Fauré, E., Å. Svenfelt, G. Finnveden, and A. Hornborg. 2016. “Four Sustainability Targets in a Swedish Low-Growth or Degrowth Context.” Sustainability 8 (11): 1080. doi:10.3390/su8111080.

- Fuchs, D., A. Di Giulio, K. Glaab, S. Lorek, M. Maniates, T. Princen, and I. Røpke. 2016. “Power: The Missing Element in Sustainable Consumption and Absolute Reductions Research and Action.” Journal of Cleaner Production 132: 298–307. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.02.006.

- Fuchs, D., and S. Lorek. 2005. “Sustainable Consumption Governance: A History of Promises and Failures.” Journal of Consumer Policy 28 (3): 261–288. doi:10.1007/s10603-005-8490-z.

- Geels, F., and J. Schot. 2007. “Typology of Sociotechnical Transition Pathways.” Research Policy 36 (3): 399–417. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2007.01.003.

- Goode, L., and M. Godhe. 2017. “Beyond Capitalist Realism – Why We Need Critical Future Studies.” Culture Unbound 9 (1): 108–129. doi:10.3384/cu.2000.1525.1790615.

- Gunnarsson-Östling, U. 2011. “Gender in Futures: A Study of Gender and Feminist Papers Published in Futures, 1969–2009.” Futures 43 (9): 1029–1039. Futures doi:10.1016/j.futures.2011.07.002.

- Gunnarsson-Östling, U., Å. Svenfelt, and M. Höjer. 2012. “Participatory Methods for Creating Feminist Futures.” Futures 44 (10): 914–922. doi:10.1016/j.futures.2012.06.001.

- Hanger-Kopp, S., J. Lieu, and A. Nikas. 2019. Narratives of Low-Carbon Transitions: Understanding Risks and Uncertainties. London: Routledge.

- Hertwich, E. 2005. “Consumption and the Rebound Effect: An Industrial Ecology Perspective.” Journal of Industrial Ecology 9 (1–2): 85–98. doi:10.1162/1088198054084635.

- Higgins, P. 2015. Eradicating Ecocide: Laws and Governance to Prevent the Destruction of Our Planet, 2nd ed. London: Shepheard-Walwyn.

- Hudson, C., and M. Rönnblom. 2020. “Is an ‘Other’ City Possible? Using Feminist Utopias in Creating a More Inclusive Vision of the Future City.” Futures 121: 102583. doi:10.1016/j.futures.2020.102583.

- Inayatullah, S. 2008. “Six Pillars: Futures Thinking for Transforming.” Foresight 10 (1): 4–21. doi:10.1108/14636680810855991.

- Jackson, T. 2009. Prosperity Without Growth: Economics for a Finite Planet. London: Earthscan.

- Jaeger-Erben, M., J. Rückert-John, and M. Schäfer. 2015. “Sustainable Consumption through Social Innovation: A Typology of Innovations for Sustainable Consumption Practices.” Journal of Cleaner Production 108: 784–798. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.07.042.

- Jensen, C., F. Oldin, and G. Andersen. 2022. “Imagining and Co-Creating Futures of Sustainable Consumption and Society.” Consumption and Society 1 (2): 336–357. doi:10.1332/XQUM7064.

- Kantamaturapoj, K., S. McGreevy, N. Thongplew, M. Akitsu, J. Vervoort, A. Mangnus, K. Ota, et al. 2022. “Constructing Practice-Oriented Futures for Sustainable Urban Food Policy in Bangkok.” Futures 139: 102949. doi:10.1016/j.futures.2022.102949.

- Kirveennummi, A., J. Mäkelä, and R. Saarimaa. 2017. “Beating Unsustainability with Eating: Four Alternative Food-Consumption Scenarios.” Sustainability: Science, Practice and Policy 9 (2): 83–91. doi:10.1080/15487733.2013.11908117.

- Kok, K., M. van Vliet, I. Bärlund, A. Dubel, and J. Sendzimir. 2011. “Combining Participative Backcasting and Exploratory Scenario Development: Experiences from the SCENES Project.” Technological Forecasting and Social Change 78 (5): 835–851. doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2011.01.004.

- Krawchenko, T., and M. Gordon. 2021. “How Do We Manage a Just Transition? A Comparative Review of National and Regional Just Transition Initiatives.” Sustainability 13 (11): 6070. doi:10.3390/su13116070.

- Lettenmeier, M., C. Liedtke, and H. Rohn. 2014. “Eight Tons of Material Footprint – Suggestion for a Resource Cap for Household Consumption in Finland.” Resources 3 (3): 488–515. doi:10.3390/resources3030488.

- Levy, D., and A. Spicer. 2013. “Contested Imaginaries and the Cultural Political Economy of Climate Change.” Organization 20 (5): 659–678. doi:10.1177/1350508413489.

- Lorek, S., and D. Fuchs. 2013. “Strong Sustainable Consumption Governance – Precondition for a Degrowth Path?” Journal of Cleaner Production 38: 36–43. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2011.08.008.

- Lorek, S., and J. Spangenberg. 2014. “Sustainable Consumption within a Sustainable Economy – Beyond Green Growth and Green Economies.” Journal of Cleaner Production 63: 33–44. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2013.08.045.

- Masini, E. 2002. “A Vision of Futures Studies.” Futures 34 (3–4): 249–259. doi:10.1016/S0016-3287(01)00042-8.

- Mccauley, D., and R. He. 2018. “Just Transition: Integrating Climate, Energy and Environmental Justice.” Energy Policy 119: 1–7. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2018.04.014.

- Meyer, L., and D. Roser. 2006. “Distributive Justice and Climate Change: The Allocation of Emission Rights.” Analyse & Kritik 28 (2): 223–249. doi:10.1515/auk-2006-0207.

- Middlemiss, L. 2010. “Reframing Individual Responsibility for Sustainable Consumption: Lessons from Environmental Justice and Ecological Citizenship.” Environmental Values 19 (2): 147–167. doi:10.3197/096327110X1269942022051.

- Milojević, I. 2015. “Conclusions.” In CLA 2.0: Transformative Research in Theory and Practice, edited by S. Inayatullah and I. Milojević. Tamsui, Taiwan: Tamkang University Press.

- Milojević, I., and S. Inayatullah. 2015. “Narrative Foresight.” Futures 73: 151–162. doi:10.1016/j.futures.2015.08.007.

- Milojević, I., and A. Izgarjan. 2014. “Creating Alternative Futures through Storytelling: A Case Study from Serbia.” Futures 57: 51–61. doi:10.1016/j.futures.2013.12.001.

- Mont, O., A. Neuvonen, and S. Lähteenoja. 2014. “Sustainable Lifestyles 2050: Stakeholder Visions, Emerging Practices and Future Research.” Journal of Cleaner Production 63: 24–32. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2013.09.007.

- Mont, O., Y. Palgan, K. Bradley, and L. Zvolska. 2020. “A Decade of the Sharing Economy: Concepts, Users, Business and Governance Perspectives.” Journal of Cleaner Production 269: 122215. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.122215.

- Moore, M., and M. Milkoreit. 2020. “Imagination and Transformations to Sustainable and Just Futures.” Elementa: Science of the Anthropocene 8 (1): 1–17. doi:10.1525/elementa.2020.081.

- Movik, S. 2014. “A Fair Share? Perceptions of Justice in South Africa’s Water Allocation Reform Policy.” Geoforum 54: 187–195. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2013.03.003.

- Mylan, J., H. Holmes, and J. Paddock. 2016. “Re-Introducing Consumption to the ‘Circular Economy’: A Sociotechnical Analysis of Domestic Food Provisioning.” Sustainability 8 (8): 794. doi:10.3390/su8080794.

- Neill, D., A. Fanning, W. Lamb, and J. Steinberger. 2018. “A Good Life for All Within Planetary Boundaries.” Nature Sustainability 1 (2): 88–95. doi:10.1038/s41893-018-0021-4.

- Neubert, S., C. Bader, H. Hanbury, and S. Moser. 2022. “Free Days for Future? Longitudinal Effects of Working Time Reductions on Individual Well-Being and Environmental Behaviour.” Journal of Environmental Psychology 82: 101849. doi:10.1016/j.jenvp.2022.101849.

- Ortiz, C. 2023. “Storytelling Otherwise: Decolonising Storytelling in Planning.” Planning Theory 22 (2): 177–200. doi:10.1177/1473095222111587.

- Ottelin, J., H. Cetinay, and P. Behrens. 2020. “Rebound Effects May Jeopardize the Resource Savings of Circular Consumption: Evidence from Household Material Footprints.” Environmental Research Letters 15 (10): 104044. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/abaa78.

- Page, J., and A. Pelizzon. 2022. “Of Rivers, Law and Justice in the Anthropocene.” The Geographical Journal 190 (2): 1–11. doi:10.1111/geoj.12442.

- Peleg-Mizrachi, M., and A. Tal. 2019. “Caveats in Environmental Justice, Consumption and Ecological Footprints: The Relationship and Policy Implications of Socioeconomic Rank and Sustainable Consumption Patterns.” Sustainability 12 (1): 231. doi:10.3390/su12010231.

- Petheram, L., N. Stacey, and A. Fleming. 2015. “Future Sea Changes: Indigenous Women’s Preferences for Adaptation to Climate Change on South Goulburn Island, Northern Territory (Australia).” Climate and Development 7 (4): 339–352. doi:10.1080/17565529.2014.951019.

- Polak, F. 1973. The Image of the Future. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

- Riedy, C., and S. Waddock. 2022. “Imagining Transformation: Change Agent Narratives of Sustainable Futures.” Futures 142: 103010. doi:10.1016/j.futures.2022.103010.

- Sahakian, M., and H. Wilhite. 2014. “Making Practice Theory Practicable: Towards More Sustainable Forms of Consumption.” Journal of Consumer Culture 14 (1): 25–44. doi:10.1177/1469540513505607.

- Sandström, C., A. Carlsson-Kanyama, K. Lindahl, K. Sonnek, A. Mossing, A. Nordin, E. Nordström, and R. Räty. 2016. “Understanding Consistencies and Gaps Between Desired Forest Futures: An Analysis of Visions from Stakeholder Groups in Sweden.” Ambio 45 (Suppl 2): 100–108. doi:10.1007/s13280-015-0746-5.

- Schandl, H., M. Fischer-Kowalski, J. West, S. Giljum, M. Dittrich, N. Eisenmenger, A. Geschke, et al. 2018. “Global Material Flows and Resource Productivity Forty Years of Evidence.” Journal of Industrial Ecology 22 (4): 827–838. doi:10.1111/jiec.12626.

- Schlosberg, D. 2004. “Reconceiving Environmental Justice: Global Movements and Political Theories.” Environmental Politics 13 (3): 517–540. doi:10.1080/0964401042000229025.

- Schlosberg, D. 2007. Defining Environmental Justice: Theories, Movements, and Nature. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Schlosser, M. 2015. “Agency.” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/agency

- Schmelzer, M. 2015. “The Growth Paradigm: History, Hegemony, and the Contested Making of Economic Growthmanship.” Ecological Economics 118: 262–271. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2015.07.029.

- Seyfang, G., and J. Paavola. 2008. “Inequality and Sustainable Consumption: Bridging the Gaps.” Local Environment 13 (8): 669–684. doi:10.1080/13549830802475559.

- Singleton, B. 2022. “Intersectionality and Climate Policy-Making: The Inclusion of Social Difference by Three Swedish Government Agencies.” Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space 40 (1): 180–200. doi:10.1177/23996544211005778.

- Solinger, R., M. Fox, and K. Irani. 2008. Telling Stories to Change the World: Global Voices on the Power of Narrative to Build Community and Make Social Justice Claims. London: Taylor and Francis.

- Son, H. 2015. “The History of Western Futures Studies: An Exploration of the Intellectual Traditions and Three-Phase Periodization.” Futures 66: 120–137. doi:10.1016/j.futures.2014.12.013.

- Svenfelt, Å., R. Engström, and Ö. Svane. 2011. “Decreasing Energy Use in Buildings by 50% by 2050 – A Backcasting Study Using Stakeholder Groups.” Technological Forecasting and Social Change 78 (5): 785–796. doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2010.09.005.

- Tasaki, T., A. Yoshida, M. Aoyagi, Y. Kanamori, K. Awata, N. Tominaga, A. Shimizu, H. Suwabe, and K. Nemoto. 2016. “Scenario Writing of Future Lifestyles in Japan for 2030.” Sustainable Development 24 (6): 406–415. doi:10.1002/sd.1636.

- Twine, R. 2020. “Where Are the Nonhuman Animals in the Sociology of Climate Change?” Society & Animals 31 (1): 105–130. doi:10.1163/15685306-BJA10025.

- van Hulst, M. 2012. “Storytelling, a Model of and a Model for Planning.” Planning Theory 11 (3): 299–318. doi:10.1177/1473095212440425.

- Vinnari, M., and P. Tapio. 2009. “Future Images of Meat Consumption in 2030.” Futures 41 (5): 269–278. doi:10.1016/j.futures.2008.11.014.