I love daylight and I’ll bet you do, too. In fact, though my work life focuses on light in the built environment, I spend much of my non-work life seeking light in nature. The attraction is primal, natural, and instinctual. Why is that? With that question, I’m not seeking an empty answer like people evolved under daylight, or daylight is natural. Rather, from an engineering perspective, what are the quantifiable characteristics of daylight that make it so appealing?

I should also clarify that here I am focused only on visual perceptions. LEUKOS readers understand that people have a photoperiod consistent with the earth’s daily rotation, and that the cycle of day and night strongly influences circadian photobiology and human health. The non-visual effects of daylight and darkness are indeed important, but they are largely unconscious and do not directly evoke transient emotions. To further clarify my question: From an engineering perspective, what are the quantifiable characteristics of daylight that make it emotionally appealing for vision and the psychology of visual perception?

Beyond the obvious that the sun and sky are awesome in their grandeur, I’ve come to believe that much of daylight’s emotional appeal is based on its spatial, spectral, and temporal variability, variability that is both predicable and random. Just as interesting as daylight’s intrinsic variability as a source, is how that variation perturbs the landscape, constantly revising the appearance of our physical environment through changes in shade, shadow, highlight, and color.

Temporally, some aspects of daylight’s annual and daily cycles are predictable. Annually, the earth makes one orbit around the sun. Because the earth is tilted on its axis with respect to its path around the sun, the density of solar radiation varies with time of year and position on the globe, as does the apparent position of sunset and sunrise, the position of the sun in the sky at different clock times, and the number of daylight hours. Daily, the earth makes one rotation around its axis, which we experience as dawn, daytime, dusk, and nighttime. These predictable rhythms are emotionally grounding—they connect us to the spirit of a place. An analemma is one way of illustrating the sun’s predictable annual variation; illustrates positions of the sun in the sky above Austin, TX throughout the year at a clock time of 9 AM.

Fig. 1. Composite image compiled from photographs taken between June 2014 and September 2016 at a clock time of 9 AM Central over Austin, TX. The lower right is the position of the sun at the winter solstice and the upper left the position of the sun at the summer solstice. The rotation and size of an analemma varies with latitude and longitude. Picture provided by Michael Brown, copyright 2016, all rights reserved, used with permission [Brown Citation2018].

![Fig. 1. Composite image compiled from photographs taken between June 2014 and September 2016 at a clock time of 9 AM Central over Austin, TX. The lower right is the position of the sun at the winter solstice and the upper left the position of the sun at the summer solstice. The rotation and size of an analemma varies with latitude and longitude. Picture provided by Michael Brown, copyright 2016, all rights reserved, used with permission [Brown Citation2018].](/cms/asset/673b5c54-5607-448b-9548-f083711f5c0f/ulks_a_1471941_f0001_oc.jpg)

Other temporal aspects of daylight are momentary and unpredictable, as when clouds occlude a sunbeam. These brief interludes delightfully influence perceptions of texture, shape, and space. includes two images taken just a few seconds apart, illustrating how a single cloud can change how objects are rendered.

Fig. 2. (a) Image of a handful of black raspberries taken under a direct sunbeam on a partly cloudy day. (b) Similar image, but taken as the sun passed behind a cloud. Pictures provided by Kevin Houser, copyright 2018, all rights reserved, used with permission.

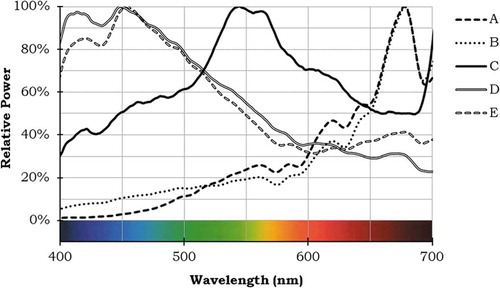

The spectral nature of daylight is a function of how the earth’s atmosphere modifies extraterrestrial solar radiation. When the sun is in different sky positions, it passes through different densities of atmosphere before arriving at the ground. When the sun is near the horizon the path-length through the atmosphere is greater, leading to more diffusion and scattering by aerosols. Shorter wavelengths are diffused while longer wavelengths make it through, which we see as red and yellow sunrises and sunsets. plots several measurements of real daylight, illustrating common variation in daylight spectra.

Fig. 3. Several spectral power distributions (SPDs) of real daylight: (A) 2300 K daylight at Bregenz, Austria just before sunset over Lake Constance; (B) 2600 K daylight at Mt. Hamilton in Santa Clara, CA just before sunset; (C) 5000 K daylight in Como, Italy measured underneath a tree canopy; (D) 17900 K daylight in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia measured under a clear sky; (E) 19500 K daylight in Cleveland, OH measured under a clear sky. Spectrometer recordings provided by Telelumen LLC, copyright 2018, all rights reserved, used with permission.

The spatial aspects of daylight are affected by the earth’s atmosphere and by terrestrial objects. An overcast day feels different from a partly cloudy day because patterns of luminance are distinctly different. On a clear day, the unobstructed sunlight on a beach is different from sunlight filtered through a tree’s canopy. The former creates crisp shadows; the latter casts dappled patterns on the forest floor. Dusk and dawn in the Rocky Mountains are different from dusk and dawn on the Great Plains because the horizons are so different. illustrates several images of the natural world, illuminated only by daylight, showing a common range of spatial patterns.

Fig. 4. Daylight images that suggest Richard Kelly’s concepts of (a) ambient luminescence, (b) play of brilliants, and (c) focal glow [Donoff Citation2016]. (a) Diffuse light of a foggy day. (b) Mottled sunlight through trees. (c) Warm glow of sunlight in a canyon. Pictures provided by Kevin W. Houser, copyright 2018, all rights reserved, used with permission.

![Fig. 4. Daylight images that suggest Richard Kelly’s concepts of (a) ambient luminescence, (b) play of brilliants, and (c) focal glow [Donoff Citation2016]. (a) Diffuse light of a foggy day. (b) Mottled sunlight through trees. (c) Warm glow of sunlight in a canyon. Pictures provided by Kevin W. Houser, copyright 2018, all rights reserved, used with permission.](/cms/asset/faea91da-c444-48be-9b22-709b78df1700/ulks_a_1471941_f0004_oc.jpg)

No matter how much time each of us spends outdoors, we would benefit if we did more of it. Even if your interior environment is beautiful and comfortable, I encourage you to go for a walk, each your lunch while sitting on a bench, and take frequent daylight showers. Even ignoring my didactic analysis, I do hope you’ll enjoy the annual, daily, and momentary variability that makes daylight so delightful.

References

- Brown M 2018. Austin analemma. [Online]. [ accessed 2018 April 25]. https://www.austinanalemma.com.

- Donoff E. 2016. 30 moments in lighting: 1 Richard Kelly’s three tenets of lighting design. Archit Light. 30(6):15.