ABSTRACT

Architectural lighting provides optimum visibility for tasks but illuminations convey meanings as well. Though many studies analyze technical dimensions of lighting, research on the meaning is rare. Therefore, this article discusses semiotics as a methodology for lighting design within the design process and critically reflects the appearance of light and architecture. The semiotic discourse starts with terminology and presents models of architectural signs. The history of architectural semiotics serves as a background for the transfer to lighting and leads to an understanding of recent debates. The relevance of semiotics for lighting design is shown in three aspects: Firstly, the influence on the lighting design process; secondly, how physical characteristics of light intensity, distribution, and spectrum are interpreted as signs; and, thirdly, the evaluation of different lighting design tasks like daylight, lamp and luminaire design, interior and exterior lighting, as well as media façades. A critique of architectural and lighting semiotics reveals the methodological limitations of the linguistic concept. It can be concluded that semiotics provides a useful instrument to identify the meaning, which helps to improve the quality of lighting design. The semiotic matrix offers a differentiated view of relationships based on the aspects of sign, object, and interpretant with relation to light characteristics, illuminated buildings, and architectural lighting in general.

1. Introduction

Semiotics is a method to study the meaning of signs and therefore represents an interesting approach to analyze sign systems like architecture. The semiotics of architecture has emerged as a branch of semiotics for visual communication and allows the interpretation of the building as a sign and the user as a receiver. Similarly, windows, luminaires, and lighting pattern in the space embody signs. Consequently, the transfer of semiotics to lighting design offers an opportunity to enhance the discussion of the quality of lighting. This strategy can be beneficial for a more comprehensive evaluation of architectural lighting regarding research, education, and design. Such a view is especially relevant for lighting situations that appear technically correct but where users experience problems in meeting their expectations and understanding their meaning.

Semiotics studies complex systems of signs and their meaning as part of a communication between sender and receiver (Nöth Citation1990). Three dimensions of semiotics indicate the scope: syntax as the grammar, semantics as the relationship between signs and their meaning, and pragmatics as the language within the social context ().

Semiotics has mainly been influenced by linguistics and was later applied to aesthetics and visual communication like architecture, painting, or film. Light is examined as a code and a unit of information that produces an identity as result of a linguistic outcome. Within this perspective, light in architecture is used as a social construct, where contrastive and fluid identities emerge (Wardhaugh and Fuller Citation2015). When the relationship between architecture and light is not reduced to conveying only the meaning and function but also understood as an influence on our behavior, we even assign a rhetoric role (Hattenhauer Citation1984).

The impact of light for generating an identity is particularly interesting for clients who strive for representation and a narrative component for their corporate design (Jackson et al. Citation2015). The latter is of high interest for the retail environment, urban design, and marketing. Eye-catching animations on media façades are just one form of architectural expression that use light to communicate a message to people. On a small scale, semiotics for lighting can help to understand the interest in symbolism like the retro designed Edison light bulbs with light emitting diode (LED) technology. In the future, the rising LiFi technology will add another dimension to the semiotic analysis of architectural lighting, where the spectrum, light distribution, and luminaire form will influence not only the meaning but also the content, which the beam sends to users (Elgala et al. Citation2011).

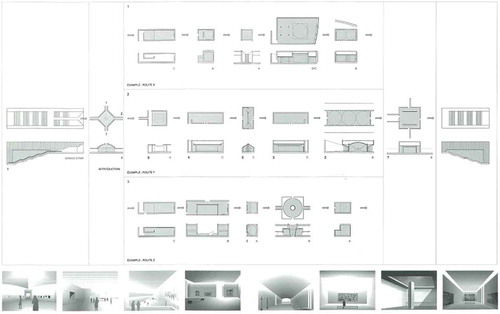

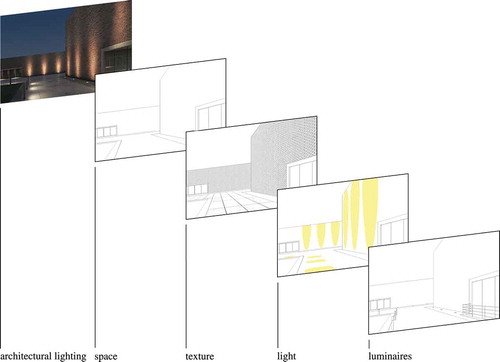

Using sign theory for architectural lighting offers methodological impulses for different research strategies in architecture: qualitative research, logical argumentation, case studies, and interpretive–historical research according to the categories by Groat and Wang (Citation2002). On the one hand, focus on the qualitative aspects of lighting enhances individual well-being by including social and communicative aspects as well as aesthetic judgement, whereas, on the other hand, quality improves architecture with the aspects of style and composition when referring to Veitch’s definition of lighting quality (Veitch Citation2001). Environmental studies have developed an information processing model to evaluate qualities where the factor legibility indicates a link to semiotics even if it has not been explicitly discussed yet (Kaplan and Kaplan Citation1989; Major et al., Citation2005). The logical argumentation is particularly relevant in an educational context, as part of the design process, and in the critique of illuminated projects, where, for instance, the arrangement of the different units such as light source, luminaires, light distribution, and architectural elements are analyzed () (Krautter and Schielke Citation2009).

Fig. 2. Semiotic design layers for architectural lighting: Space, texture, light, and luminaires. Rendering layers: Axel Groß. Image © ERCO.

Concerning case studies, semiotics can help to identify complex systems of how lighting technology can be applied and the generated image and user experience combined. It could offer input to increase interest in the psychological effects in identifying the way in which lighting can benefit a desirable outcome (Boyce Citation2014). Current research on the illumination hierarchy that expresses visual significance of the content of spaces appears to be relevant for a semiotic perspective (Mansfield Citation2018). The importance of the interpretative–historical research became obvious in studies that examined cultural phenomena with changes of meaning through time or relationships between different fields such as art, retail, and lighting (Neumann Citation2002; Salomon Citation2014).

When semiotics is applied to lighting it can be used as a tool to overcome the crisis in methodology of design and naïve functionalism and point out interpretational pluralities by placing man in the center. Thereby semiotics could provide an impulse for the quantitative interpretation of light, which has been criticized by the recent human-centric light movement, among others (Bodgrogi et al. Citation2017). A qualitative method like semiotics can be added to quantitative research in order to adequately prepare it or to explain it afterwards (Kelly Citation2017).

Architectural semiotics presents a branch of semiotics for visual communication, which is related to aesthetics, objects, and space. In architecture, the semiotic approach became very popular with the onset of postmodernism, where designers criticized the primacy of function by using dominating forms as meaningful entities or alternatively by deconstruction to reveal morphological elements (Lagopoulos Citation1993). These specific buildings range from explicit representations through their shape and construction, like the Binoculars Building in Los Angeles, to metaphorical applications of the linguistic concept by Eisenman (Djalali Citation2017). The recent emergence of iconic landmark buildings—for instance, the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao leading to the so-called Bilbao effect—exemplifies the topicality of architecture as a sign (Jencks Citation2005). In a similar way, the rising interest of builders to include a media façade shows the interest of creating a specific identity with light (Jackson et al. Citation2015). Additionally, architectural photography has reinforced the trend for pictoriality and architects’ interest in creating attractive images (Ruby et al. Citation2004).

Introducing various semiotic theories in this article offers the chance to explore different perspectives for lighting tasks—for example, to understand the meaning of a specific lighting installation, the design rules that create a structure of light for buildings, and the historical or cultural context—which has an impact on the perception of an illuminated space. The theories also provide the possibility to select simple or complex models to analyze solutions.

In this article, the semiotic discourse for light starts with models of architectural signs. The history of architectural semiotics serves as a background for the transfer to lighting and leads to an understanding of recent debates. Options to use semiotics for lighting are illustrated regarding the design process, the meaning of photometric parameters, and lighting design tasks ranging from the light source up to urban design issues. A critique of architectural and lighting semiotics reveals the methodological limitations of the linguistic concept.

2. Models of the Architectural Sign

Semiotics does not just have one unifying theory but has different models to interpret the relation between sign and the interpreter, which influences the analysis. For the architectural sign, the behavioristic, dyadic, glossematic, and triadic sign models play a central role (Nöth Citation1990).

2.1. Morris’s Behavioristic Model

The behaviorist model goes back to Morris and was written by Koenig (Koenig Citation1964). The architectural sign is considered a preparatory stimulus where specific behaviors result as a response (Nöth Citation1990). Nöth exemplified this with learning building: The denotata of a school are the children who study there. The significatum of this building is the fact that these children go to school ().

2.2. Saussure’s Dyadic Model

The model of Saussure with the sign as the unit of the signifier in the sense of sign body and signified as meaning was incorporated by De Fusco into his semiotic analysis of architecture, in which he interpreted architecture as a mass medium (De Fusco Citation1972; Saussure Citation1969). He illustrated this aspect, among other things, with the development of large department stores and museum buildings, which became centers of communication. De Fusco referred to Saussure’s terminology of “signifier” and “signified” when he introduced his categories of outer and inner space, where the inner space embodied the essence and imagination of architecture ().

The perception of a built project serves as an illustration: The Institut du Monde Arabe in Paris: The actual building with the diaphragms to filter daylight embodies the signifier. The architecture and daylight design signifies a hinge between the Arabic and European culture as between tradition and modernity. The façade details appear as homage to Arabic culture with the modern interpretation of mashrabiya as traditional Arabic screen, whereas the general form does not quote typical Arabic forms like mosques but rather refers to rational geometries. The detailing of the diaphragms with the characteristic apertures also refers to the tradition of photographic development in France. In addition, the motorization of the diaphragms epitomizes modern high-tech design.

2.3. Hjelmslev’s Glossematic Model

In addition to the behavioral model of Morris and the dyadic approach of Saussure, Nöth identified the glossematic model of Hjelmslev, which Eco (Citation1972) further developed. Eco saw a weakness in the triangular model, because one cannot differentiate between the signifier as a material sign bearer and the object of the signs because both units refer to the same physical reality. His differentiation from “denotation” and “connotation” was based on the content and expression of substance and form (). The units of expression, morphemes, had the units of content, the semene, as a counterpart. The semene is divided into architectural function, either in the denotative physical functions or in the connotative socio-anthropological functions. Concerning architectural lighting, a glazed entrance hall provides natural light in the physical dimension and at the same time represents transparency and openness on a connotative level. The morphemes as elements of expression are divided into a comparable form. This means that one can use the semantic component “luxurious” with a morphological component such as “valuable glass crystals.”

2.4. Peirce’s Triadic Sign Model

The fourth model for Nöth was the model of Peirce, consisting of sign, object, and interpreter. If you transfer this tripartite model to the New Yorker Empire State Building with its color coding at the top of the building to inform about holidays and events, then the building would represent the object. The changing architectural lighting program with colored light can be considered as a sign and the citizens and tourists of Manhattan represent the interpretant.

The relation of the sign to the three poles was accordingly the reference to the sign, object, and interpretant () (Bense and Walther Citation1973). The sign reference was divided into the qualisign as a sensible appearance of the sign (for example, color); the sinsign, which was location and time dependent as a real existing character; and the legisign, which was not bound to a singular appearance. The object reference was in turn divided into the icon, which mimicked its object as a character; the index, which had a direct relationship to the object as location and time dependent; and the symbol, which was arbitrary to the object but can be based on cultural assumption. The interpretant reference consisted of the rhema, which offered a qualitative possibility; the dicent, which really existed and could therefore be true or false; and, finally, the argument for a legitimate context.

The model of Peirce also allows a transfer to architectural lighting, illustrated in , and can be applied to a project like the Yas Viceroy Hotel with its media façade (Schielke Citation2014). The colored light of the media façade serves as the qualisign. The specific grid of the media façade in Abu Dhabi corresponds to the sinsign and the general meaning of media facades the legisign. The object reference can be differentiated into the icon with the design program for marketing; for example, with the aspects specificity and exclusivity. The uniqueness as meaning of Yas Viceroy media façade forms the index. The specialty of media façades corresponds to the symbol and derives from the fact that media façades are only used in singular cases and thereby generate a strong contrast when compared to conventionally illuminated facades. The qualitative evaluation of colored light and dynamics in general represents the rheme, whereas the dicent refers to the tourist’s opinion of whether the media facade of the Yas Viceroy Hotel looks exceptional and exclusive. The argument deals with the aspect of which extent media facades are a special feature.

Table 1. Semiotic matrix for architectural lighting based on Peirce’s classes of signs.

3. History of Architectural Semiotics

The semiotics of architecture originated as a sideline from semiotics in the 1960s, which focused on the meaning of buildings based on architecture history and theory with early titles like “Meaning in Architecture” (Jencks and Baird Citation1969) and “The Language of Architecture” (Prak Citation1968). At the end of the 1960s, architectural semiotics became an independent field of semiotics (Nöth Citation1990). For Nöth the architectural semiotics covered the construction from the single building up to urban design as a sign system and systematically described it as a code. Thereby, it established a contrast for him in relation to the asemantic nature of architecture, which interpreted the architecture exclusively in its functionality.

Barthes was one of the first who applied the ideas of semiotics to visual images and later developed a high interest in urban design, which became visible in his 1964 essay of the Eiffel Tower as an iconic center and functioned as a signifier independent of any specific referent (Barthes Citation1997). Norberg-Schulz, influenced by Morris’s interpretation of semiotics, invented a phenomenological approach with four levels of “existential space”: geography and landscape, urban level, and “the thing” (Haddad Citation2010). He observed the relationship between the man-made world and natural world through a three-point process of visualization, complementation, and symbolization. His theory involved a reductive approach with three categories for the landscape and the man-made world with romantic, cosmic, and classical archetypes.

The publications “Learning from Las Vegas: The Forgotten Symbolism of Architectural Form” (Venturi et al. Citation1977) and “The Language of Post-Modern Architecture” (Jencks Citation1977) have been very influential in the semiotic context. Jencks revealed how architecture can be regarded as a sign from a metaphor to a cliché. In his view, architectural elements like windows and columns can be regarded as “words” and identified as a reuse of symbolic signs linked to a specific meaning. For instance, a problem with the meaning becomes noticeable when purist transparent architecture with ribbon windows is transformed into conventional signs of homes by the residents with added shutters and more window mullions due to the perceived lack of shelter and protection. The rules for combining the various words of windows and walls are interpreted as syntax, whereas the semantics describe the relationship of the elements and their meaning.

According to Preziosi, the functions of architecture were divided into six points: (1) referential function of the architectural context, (2) aesthetic function via the architectural design, (3) metacodal function as architectural allusions or quotations, (4) phatic function in the sense of a territorial aspect of a building, (5) expressive function as self-representation of the builder, and (6) conative function in terms of user-related aspects of architecture (Nöth Citation1990; Preziosi Citation1979). To exemplify the different functions above the corner window at the Fallingwater building from 1939 serves as a daylight detail. Frank Lloyd Wright said in an interview,

The corner-window is indicative of an idea conceived early in my work, that the box was a Fascist symbol, and the architecture of freedom and democracy needed something beside the box. So, I started out to destroy the box as a building. Well, the corner-window came in as all the comprehension that ever was given to that act of destruction of the box. The light came in where it had never come before, vision went out. And you had screens instead of walls—here the walls vanished as walls, and the box vanished as a box. (Downs and Wright Citation1953)

The architectural context of the project consists of a natural environment. The special aesthetics of the window derive from the dematerialized corner, which was solid in the architecture and windows were only positioned next to the corner support. The meta-architectural function lies in the political dimension, where the architect used a certain design to mediate freedom and democracy with a window instead of planning a closed volume. The territorial perspective results from the topography of the waterfall at the house and the spectacular view of the landscape through the window. As an owner of a department store in the heavily steel-dominated city of Pittsburgh, the client looked for a compensation of his industrial environment with his holiday home surrounded by unspoilt nature. The client’s openness toward modern art and design, the choice of architect, and the realization of a visionary building for that time clearly demonstrate an architectural self-representation with an expressive orientation. The connotative function for the residents finally lies, on the one hand, in a unique window, which was later published worldwide, and, on the other hand, in the individual associations with the residents’ view.

Mitchell intensified the discussion of languages of architectural form and their specifications by means of formal grammars (Mitchell Citation1990). His view was based on Chomsky’s theories of language. He described the classical order of architecture with linguistic theory for analyzing sentence structures.

Unfortunately, this strategy did not consider the perspective of meaning.

4. Architectural Semiotics Since 2000

With the critique of postmodernism, the debate about architectural semiotics has almost vanished. In contrast to the theories of the 1960s to the 1980s, the newer approaches do not interpret architecture as language or as a model of verbal speech. Most of the critique regards architectural semiotics as one aspect of a comprehensive architectural theory. The review of recent literature begins with three books where Baumberger deals with semantics, Schumacher with syntax, and Delitz with pragmatics, followed by recent papers.

Baumberger transferred Goodman’s architectural symbol system, which primarily described the notation system of drawings and plans, to general architecture like buildings and urban structures (Baumberger Citation2010; Goodman Citation1968). Baumberger explored the semantic dimension very analytically when he related the architectural signs to possible meaning by using Goodman’s terms of “denotation,” “exemplification,” “expression,” and “complex reference.” Thereby, Baumberger identified direct and indirect relations of buildings or building parts precisely and, for instance, divided references into stylistic, typological, local, and cultural aspects.

Schumacher’s system was developed as an extension of Luhmann’s theories, where he added architecture as an independent social system (Luhmann Citation1995; Schumacher Citation2011). Schumacher’s interest in contemporary architecture became visible in adding innovation to utility and beauty as elements of the double code of architecture. With this framework, he introduced and tried to justify parametricism as an upcoming universal style, which he designed in collaboration with Zaha Hadid. He argued that in the period of classic modern architecture, the indexical relation referred mostly to constructive and technical features. As a consequence, the iconic and symbolic relation was neglected. For Schumacher, a semiotic system was necessary within the design process so that new architectural forms could be read and understood by society.

In her theory, Delitz worked with a very tight constellation between architecture and society and thereby concentrated on the pragmatic perspective of architecture (Delitz Citation2010). She introduced society as an imaginary institution, where symbols were used as a form of expression and the architecture played a central role in the generation of self-presentation.

Semiotics also offered the possibility to examine the aspect of style (Tschertov Citation2006). For Tschertov, for example, syntax included continuity, homogeneity, symmetry, and dimensionality in the architectural code. Furthermore, the semantic forms of expression implied movement or development.

Iconic buildings like the Guggenheim Museum act as signature architecture and therefore the creation and reception of architecture requires a pictoriality, argued Ullrich (Citation2014). She referred to Peirce to point out differentiate levels of iconicity, when analyzing quotes: image, diagram, metaphor. In particular, media façades use the building surface for emotional pictures, which, when electronically controlled, emanate prerecorded repetitive patterns or can generate live or interactive content and thereby create a changing appearance of the building (Haeusler Citation2009).

Semiotics also has relevance for architectural conservation (Remei Citation2014). Preservationist processes change not only the appearance and physical features of a building but also its meaning. These measures are merely neutral but can entail modifications and even distortions of the original meanings. The quality of interventions can be analyzed in regard to epistemological and symbol-theoretical aspects. Three aspects were important for Capdevilla: (1) The preservationist measurements should avoid misunderstanding by accepting that they are not neutral but present interpretations of a symbol. (2) It is better to preserve a maximum of meanings instead of doing a selection. (3) Preservation should keep a plurality of meanings for an open interpretation in the future.

5. Semiotics and Lighting

The background of architectural semiotics provides a useful overview of several models and present discussions that can be applied to lighting design. Similar to architecture, light is used as a medium to generate an atmosphere. In addition to the functional aspect of visibility, it conveys a meaning. Studying the syntax—the grammar of how light elements can be combined—could enhance the design process. The semantic dimension raises awareness for the illuminated buildings as signs and what they stand for. Finally, a pragmatic perspective would complement the system to especially evaluate its interpretation in a social context. The different styles to illuminate a building find their equivalent in the different languages in the world.

Relevant academic literature about how semiotics and lighting could benefit from each other is still rare with a few exceptions. A first step toward semiotics started when architectural lighting was interpreted beyond visibility and focused on the meaning with aspects like addressing a mood or expressing intended use to complement structure or even modify the appearance of a space (Lam Citation1960). A close interplay of language and vision with a relation of text and image was applied to daylight observations and combined with a phenomenological method influenced by Norberg-Schulz (Plummer Citation2003). With this point of view, the character of light is explained not by historical influences or technology but by sensuous experience. An explicit connection between electrical lighting and semiotics was drawn by Ruxton as a perspective to assess lighting beyond technology (Ruxton Citation2011). A more detailed semiotic analysis was introduced for architectural lighting and particularly the retail environment and media façades with experiments and a model based on Peirce that links the different views of the sign, object, and interpretant (Schielke Citation2014, Citation2015).

In addition to the architectural context, publications about semiotics and stage lighting and visual arts exist. Semiotics became useful for analyzing stage lighting and the communication between the performer and the audience and to identify lighting signs associated with productions (Moran Citation2007). For instance, the image of the moon represents an indexical sign pointing to the fixture that is projecting it. Examining light and shadow for modern visual arts and in early cinema benefits from a semiotic analysis as well (Sadowski Citation2017).

Firstly, the various options to apply semiotics for daylight and lighting design are subsequently shown for the design process; secondly, how the basic light characteristics have a meaning in a general context; and, thirdly, specific design tasks are presented with the above semiotic models and theories based on specific projects.

5.1. Semiotics for Lighting Research

Semiotics provides a valuable addition to prevalent quantitative-orientated research strategies. It could help to detect significant factors for respective experiments and to classify the results. Qualitative studies would benefit from finely nuanced views of multiple semiotic theories. Especially for complex research questions like human-centric lighting, semiotics would raise an awareness for multiple parameters and social components. When utilizing case studies as a research method, semiotics offers a helpful matrix to relate lighting as a sign, the viewer as interpretant, and the light characteristics and architecture in general as an object. Interpretative–historical research projects would also benefit from this perspective. Similarly, the user as an interpretant would be beneficial for postoccupancy research.

5.2. Semiotics for Lighting Education

Educators can apply semiotics in various ways for teaching architectural lighting. Studying vocabulary and typologies serve as a basis to understanding existing situations as part of site visits or history and transferring the knowledge to design tasks. Learning a vocabulary of window types and the production of compositions has been a standard practice for architectural education (Mitchell Citation1990). The size, form, and proportion of a window in relation to the whole façade communicate a symbolic dimension; for example, a large horizontal window represents a modern style in contrast to small vertical windows (Corbusier Citation1927). Vernacular windows are not only a function of the daylight situation but are readable as social and aesthetic statements (Anselmo and Mardaljevic Citation2013). Typologies of daylight patterns allow architects to develop a precise language for their composition and help to compare design solutions (Rockcastle and Andersen Citation2013). These multiple views enhance students’ competence for a comprehensive evaluation of competition results and stimulate the exchange of interdisciplinary groups within complex projects. The quality of communication, like visualization, is another relevant factor for education and depends upon the media and the applied technique used (Innes Citation2012; Rozot and Peón-Veiga Citation2010; Schielke Citation2008).

5.3. Semiotics for Lighting Design

Semiotics can be relevant during the design process while analyzing a project, comparing designs, and visualizing. This viewpoint can be applied to daylight and illumination. Daylight openings and luminaires as tools possess an iconic quality but the generated light pattern in combination with different photometric parameters create specific lighting effects as well.

Pioneers of architectural and stage lighting defined functions of lighting beyond visibility early on. Stanley McCandless regarded communicating a mood with a dramatic effect as one of his four lighting functions for the stage (McCandless Citation1939). Influenced by McCandless, Richard Kelly defined three distinct functions of lighting “focal glow,” “ambient luminescence” and “play of brilliants,” which were based on daylight phenomena and linked to electrical lighting techniques to generate specific moods (Kelly Citation1952). The simplification of the lighting designer’s approach represented an effective communication strategy in the dialogue with clients to identify the desired mood, although the reduction of categories did not necessarily lead into a restricting factor as Kelly’s versatile design language showed (Neumann Citation2010). The luminaire itself can be interpreted as an icon of a specific style and conveys a historical message (Fiell and Fiell Citation2013).

5.3.1. Lighting design process

The methodology of semiotics can also be applied for the general collaborative design work within a lighting design office and with the architect. The design thinking is regarded in semiotic terms as a complex of signs with three components: a virtual building, an envelope of consideration, and a network of meanings (Medway and Clark Citation2003). A semiotic approach is useful for identifying complex environmental patterns within the analysis and helps to evaluate alternative concepts within the design phase. In addition to the oral and written communication of lighting design, semiotics enhances the understanding of visualizations. Drawings, diagrammatic representation, or computer-generated images represent a product of an ideological framework of a society and require a careful application (Riley Citation2004).

5.3.2. Photometric parameters

The basic physical characteristics of light intensity, light distribution, and spectrum are introduced as carriers of meanings in a general context. The light intensity with dark and bright light is used as a sign to convey an atmosphere for night and day. The connotation for darkness ranges from feeling unsafe, for example, in hardly illuminated streetscapes up to fascination for magical exhibition where several exhibits are kept concealed (Lam Citation1977). The interest in shadow can be linked to local culture as well, as Tanizaki revealed in the case for Japan (Tanizaki Citation1977). In contrast, brightness is a sign to create the image of day, activity, transparency, and openness, with the risk of uncomfortable glare when too bright; for instance, as used with luminaires that have no cutoff. Daylight-filled atria are a sign for the bright design strategy as well.

The parameters of diffuse and directed light are closely connected to a cloudy sky and direct sunlight, respectively. They can be regarded as a medium to communicate either a soft atmosphere; for instance, with the signs of diffuse luminous ceilings in museums or rich in contrast mood with clear glass roofs for direct sunlight () (Krautter and Schielke Citation2009).

The spectrum will be discussed with regard to color temperature and colored light. Low color temperature reveals a similarity to fire or candlelight, whereas high color temperatures show a close link to daylight. The former can be found in restaurants and hotels for a cozy atmosphere, whereas the cooler light color is more often used as additional lighting to daylight in offices (Krautter and Schielke Citation2009). When color was taken into account, studies showed that cool material colors such as blue or green were associated with a tranquil effect in contrast to warm material colors like orange and red, which appeared stimulating (Babin et al. Citation2003; Bellizzi and Hite Citation1992; Crowley Citation1993). Associations for colored lighting were linked to natural light with the blue cast of twilight or the orange shift of the sunset and thereby colored light would act as a signifier for the respective atmospheres (Major et al. Citation2005). The meaning of colors can also be closely connected to local traditions, like the reflectance of daylight on gold or red surfaces in Japan (Plummer Citation1995). The use of cross-cultural color schemes needs to be carefully evaluated, because both similarities and dissimilarities occur for color meaning associations between different countries (Kress and Van Leeuwen Citation2002; Madden et al. Citation2000).

5.4. Lighting Design Tasks

Due to the fact that the types of projects vary widely, several semiotic issues become relevant. The examples will be illustrated with specific applications ranging from single installations up to urban design projects in the context of spectrum, light distribution, and luminaire form. They will be discussed in regards to style, the symbolic meaning, the role of the interpreter, and changes in context over time.

5.4.1. Daylight: Parametric language

The relevance of Schumacher’s notion for parametricism becomes visible in the use of diagrammatic grammar to translate algorithmic rules for daylight design solutions. The complex honeycomb-inspired shading system for the Al-Bahr Towers () in Abu Dhabi designed by AHR responds kinetically to the sun’s movement and generates a distinct identity for the client, involving a strong pictoriality that Ullrich discussed (Karanouh and Kerber Citation2015). The communication of the design was accompanied by a so-called code—the abbreviation for construction, operation, and design execution. The pattern design quotes the mashrabiya as a traditional and local Islamic façade detail. But with parametric modeling and control software, the solar screen evolves into a dynamic daylight façade. From a pattern point of view, the Al-Bahr Towers screen represents a large-scale quote of Jean Nouvel’s Institut Du Monde Arabe in Paris with its small-scale light-sensitive diaphragms but with an automated design process.

5.4.2. Lamp design: Signifier for price perception

The emergence of LED technology, which was accompanied by new forms for lamps and luminaires, has triggered a discussion about style and social context involving semiotics as well. The pixel aesthetic of LEDs has indicated innovative design. One part of this transformation is due to the changing perception of light sources when compared to the larger high-pressure discharge lamps, tungsten lamps, or older linear fluorescent lamps. Nevertheless, the rising usage of LED technology was accompanied by an increase in retro design mimicking vintage Edison filament light bulbs. This retro design can be assigned to a social environment and works as a signifier in the sense of Saussure’s model for a price level in stores; for example, in Brooklyn to indicate upscale shops (Campanella Citation2017).

5.4.3. Luminaire design: Genius loci

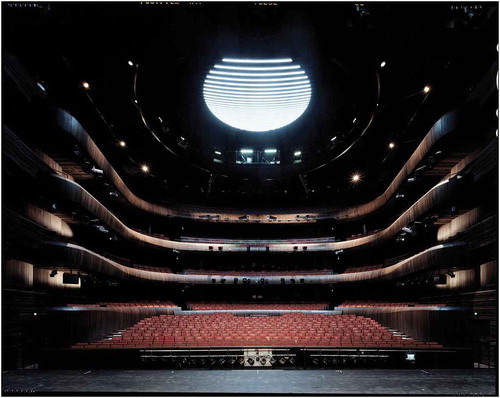

When looking for a contemporary expression in order to achieve a specific new identity for the client, the designer starts to question the traditional design language of luminaires. Historical concert halls like the Neo-Baroque Palais Garnier for the Paris Opera had a central decorative and round chandelier in their main halls (Schivelbusch Citation1995). For the main hall of the opera in Oslo, the designers quote a round form in combination with sparkling hand-cast glass bars, but the overall form is a large linear layout that can be found in modernist abstract paintings () (Snøhetta Citation2009). Further on, the detailed single crystals appear like an ice sculpture and thereby emphasize a link to the local environment of glaciers—an aspect that Norberg-Schulz discussed with the terms “geography” and “landscape” as part of his genius loci concept. The round cool form on the ceiling is a metaphor as it generates a connection to the moon.

5.4.4. Luminaire design: Direct quote

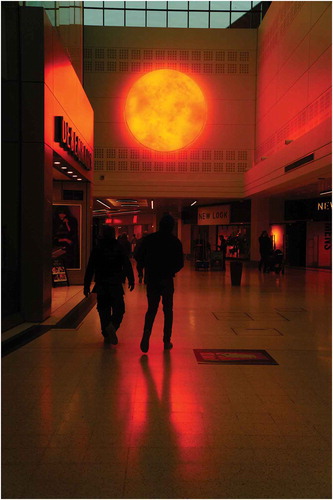

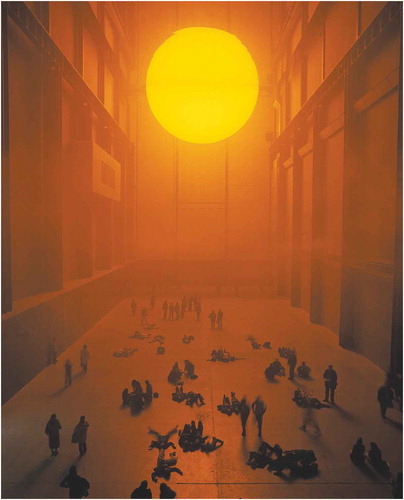

In contrast to the Oslo concert hall with a regional reinterpretation of chandeliers, direct quotes can, for instance, relate to culture, religion, or nature. The Kingfisher Mall in Redditch contains a strong symbolic dimension with a sun-like element (). The orange circle below the ceiling at the end of a long hall evokes the association of a sunset when compared to nature and emanates an intense pictoriality like Ullrich argued. With the widely published “The Weather Project” installation by Olafur Eliasson at the Tate Modern in London (), the orange circle appears like a quote of the artistic predecessor (May Citation2004). Considering that the artist himself quoted the natural sun, we find a quote of the first quote in the mall. The central upper position at the end of a long hall also creates an homage to Gothic church architecture with the characteristic luminous rose windows. The iconic orange image of both projects appears to be similar, though the details are different. Eliasson used a semicircle illuminated with monofrequency lights that he mirrored and a haze machine diffused the image. In contrast, Elektra Lighting avoided a single pure color and printed a graphic panel on the front for the sun at the mall. The two orange and red light colors in combination with light control lead to an animated surface.

Fig. 9. Main Hall at Norwegian National Opera and Ballet with chandelier, Oslo, Norway, 2008. Architecture: Snøhetta. Photo by Helene Binet. Image © Helene Binet.

Fig. 10. Kingfisher Mall, Redditch, UK, 2016. Lighting Design: Elektra lighting. Image © Elektra lighting.

The desire to quote daylight is visible in numerous projects. Numerous installations refer to the natural sky to enable a natural atmosphere for the interior, but often they achieve this only on the level of a static image on the ceiling. Dynamic ceiling images with changing patterns and colors are the exception, like the Condé Nast Cafeteria in New York completed in 2006, and often they still generate only diffuse light in contrast to direct sunlight. This means that on an image level we could detect a close relationship to nature for the ceiling, whereas with regard to the light effect in the space the relationship is not given due to lacking direct light.

5.4.5. Light art: Minimalism

The use of few architectural and lighting elements forms a reaction to a design environment that employs a multitude of signs such as those used in the baroque period. This minimalistic perspective was typical for the California “Light and Space” movement, which focused on perceptual phenomena in the 1960s. Light and dark, sunlight and shadow, time and space were central elements of the artworks (Butterfield Citation1993). Artists like Robert Irwin, James Turrell, and Douglas Wheeler used natural as well as electrical lighting for their ascetic spaces.

The influence of this movement is also visible in the works of artists like Olafur Eliasson or architects like Tadao Ando, Peter Zumthor, and John Pawson, where minimal interventions with daylight create impressive experiences. Regarding illumination, the concept of minimalism is apparent in a design approach where only the light is visible and not the luminaires that were used. Decorative luminaires as surface or pendant mounted are avoided in favor of concealed details like recessed luminaires or wallslot lighting. However, critics remark that the meaning of minimalism has shifted from an art-historical movement into a signifier of a global elite Chayka Citation2016.

5.4.6. Retail lighting: Indirect quote

Indirect quotes offer retail brands the chance to define their corporate design on an abstract, general level and thereby avoid a specific image that might look less attractive to some clients. The fashion retail showrooms by Jil Sander refer to American minimalism and the minimalistic light art of James Turrell Wagner Citation2017. The preference for translucence, invisible light sources and rendering volumes with light lines to create floating surfaces was introduced by the architect Gabellini Sheppard in the Jil Sander flagship showroom in Paris in 1993 () and later implemented in numerous showrooms worldwide and included in a corporate style guide. With this architectural lighting design scheme, the German fashion label pays homage to the American light artist and intensifies its simplistic brand image by forming a link to minimal art. Due to the fact that no specific art project with reference to form, material, and light was quoted in the Jil Sander showroom as Turrell’s Wedgework series emphasizing walls, the author would regard the reference in the Paris showroom, located at 52 Avenue Montaigne, as an indirect quote, although Turrell’s minimalism according to Ullrich is a metaphor. Indirect quotes enable stores to add a brand image on a conceptual level with regard to cultural, economic, ecological, and social contexts.

Fig.11. Olafur Eliasson: The Weather Project, 2003. Monofrequency light, foil, haze machine, mirror foil, scaffold. Installation view: Tate Modern, London, 2003. © Olafur Eliasson. Photo by Andrew Dunkley and Marcus Leith. Courtesy the artist; neugerriemschneider, Berlin; Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York.

5.4.7. Façade lighting: Modification in preservation

Illuminating historic buildings with modern lighting technology faces the challenge of linking a client’s desire for a more attractive marketing image with respect for conservative historians who attempt to preserve the original meaning. Therefore, increasing the intensity of lighting for visitors establishes a stark contrast to dimly illuminated spaces signifying an unchanged and neutral appearance. The Rookery building, designed by Daniel Burnham and John Wellborn Root, was completed in 1888 and designated a historic landmark in Chicago in 1970 as an early high-rise building with a steel frame. A central light court provided daylight for the offices. Electric lamps were available for illuminating buildings, but the architects assessed the technology as unreliable and therefore did not illuminate the building exterior (Evitts Dickinson Citation2012). The building underwent several renovations, including changes of interior luminaires and reopening of the light court ceiling, before exterior lighting was added in 2011 () (Pridmore Citation2003).

Fig.12. Jil Sander boutique, 52 Avenue Montaigne, Paris, France, 1993. Architecture: Gabellini Sheppard. Photo by Paul Warchol. Image © Paul Warchol.

A strict preservationist attitude would not have permitted illuminating the façade, because it would have broken up the original night appearance of the building. In contrast, the use of a steel frame at that time indicated that the architects expressed a high interest in the latest available technology. Therefore, the lighting designers from the Office for Visual Interaction considered contemporary lighting tools and sensitively lit all of the window frames of the brick façade with grazing light using sophisticated LED technology. Floodlighting and bright spotlights were regarded as inadequate lighting tools for the complex surface details. Of course, luminaires could not be directly fixed to the terra-cotta surface because of the building’s historical landmark status. The new façade illumination is not a neutral response due to its historical background as Capdevilla remarked, but it keeps the uniformity of the building by including all window frames while the front surface is not lit in order to provide a link with the original nonlit exterior lighting. A similar situation occurred for Carnegie Hall in New York, where the façade was illuminated for the first time after 125 years. The design for the landmark by Kugler Ning Lighting included illuminated window frames as well, but additional areas using grazing light for the entrance and first floor, as well as light for the cornice, have created a more festive image.

5.4.8. Media facades: Semantic shift across time

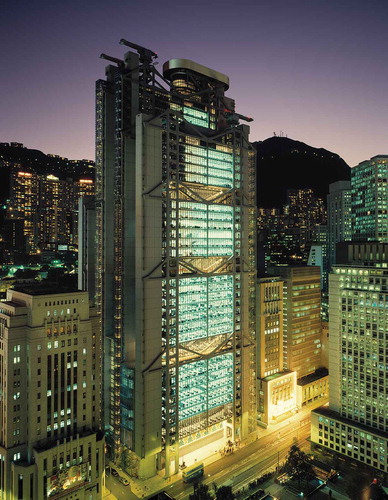

The field of media facades is another example where semiotics presents a valuable asset to evaluate the design and could help to develop readable design solutions for citizens. For example, the Hongkong and Shanghai Bank (HSBC) Headquarters by Norman Foster vividly illustrates the change of lighting over time in the digital age of LEDs and screen technology (Schielke Citation2016). The original open layout with its exposed steel structure generated a powerful corporate identity for the bank (). However, the restrained atmosphere of white architectural lighting with two color temperatures and the lack of distinctive façade lighting had lost its attractiveness two decades after its opening in 1986. The colorful and dynamic relighting presents a remarkable example of how an architectural icon has shifted from a productivist ideology toward a scenographic image—a temporal dimension that Bonta discussed (Frampton Citation2007). To the Western observer, the multicolored light language may give off a playful impression, but to the local culture the transformation evokes grandiosity.

Fig. 13. The Rookery, Chicago, Illinois, 2011. Architecture: Daniel Burnham and John Wellborn Root, 1888. Lighting design: Office for Visual Interaction. Photo by Adam Daniels. Image © Adam Daniels Photography.

In 2003, the façade illumination changed from a discreet glow from within into colorful light lines and bright search lights to create a beacon of light for the Hong Kong skyline. Since 2004, the Hong Kong Tourism Commission has tried to become a benchmark for city marketing in Asia with the largest sound and light show in the world, called “Symphony of Lights.” With globalization, rising economic competition, and political changes, the city has looked to tourism to increase business and to mark a strong, modern, and dynamic identity. Nevertheless, the first façade lighting update did not cover the newer expectation of higher visibility and more explicit messages of brand communication. For that reason, the façade lighting was amplified with a media wall for the 150th HSBC anniversary in 2015 (). Synchronized with the façade lighting, the media walls offer a very flexible infrastructure for independent content or echoing the effects of the architectural lighting on screen or vice versa. Erected originally on the ground of a British colony as a distinctive British high-tech office tower, localized with a feng shui expert, the HSBC building now resides on an autonomous territory of China. The search for a new identity, significantly influenced by globalization, has led to a new luminous mask to conceal a tough and cold finance building. This colorful overlay of pattern, made of light, has turned the HSBC into an obvious dualism: during the daytime, it conveys the cool rational image of productivism, but at night the explicit scenography demonstrates a soft emotional character.

Fig.14. Hongkong and Shanghai Bank Headquarters, Hong Kong, in 1986. Architects: Foster + Partners. Lighting design: Claude and Danielle Engle Lighting. Photographer: Ian Lambot. Image © ERCO, www.erco.com.

5.4.9. Street lighting: Psychological message

On a larger scale, many cities have updated their lighting installation for energy efficiency. Though from an engineering perspective the installations were comparable to or better than the older high-pressure sodium lamps in terms of illumination level, lighting distribution, energy consumption, and lifetime, the effect of one minor change was significantly underestimated. The local residents perceived the change to a cooler color temperature as less romantic (Squires Citation2017). The response revealed a strong symbolic power of the color temperature, which was also linked to different regions like Los Angeles as a modern city tolerating a cooler color temperature in contrast to the ancient origin of Rome requiring a more romantic, warmer light. In another city the residents called the new LED street lighting “zombie lights” and “prison lighting,” for example, due to a combination of high brightness and cool color temperature (Benya Citation2015). A semiotic analysis with the semiotic model of Peirce could help to identify the role of the interpreter to prepare a holistic, user-friendly design.

5.4.10. Light for branding: Urban identity

The term “light” has also been turned into a tool for urban self-representation and thereby into marketing communication as well. This strategy is visible in hotel names with illuminated signage on top of the building, like the Nordic Light Hotel in Stockholm, or for large-scale urban marketing with the term “city of light,” like Paris, Eindhoven, or Lüdenscheid—either associated with a long history of electric lighting going back to the Exposition Universelle of 1889 or with local lighting manufacturers like Philips or ERCO. The worldwide light festivals represent a temporary version for city marketing where cities use light to create awareness and use light to define their identity (Jackson et al. Citation2015).

5.4.11. Urban lighting: Images triggering sustainability

Despite the interest in light festivals and representative outdoor illumination, the rising awareness of light pollution has led to a countereffect where regions regard darkness as an important value and have started to establish dark sky parks in order to communicate their sustainable orientation (Anderson Citation2012; Edensor Citation2013). The growing number of satellite images of cities at night and the publication of respective reports have developed into important visual media to inform a wide audience about light pollution (Kyba et al. Citation2017). The change in visualizations of light from street-view photos to satellite images symbolizes a shift in the social context from local to global. Later, intense street lighting, captured on a large scale with satellite images, triggered discussions regarding politics and economics with the mutually profitable relationship between politicians, electrical distributors, and energy suppliers—a social dimension that Delitz emphasized and that had been pointed out, for example, in the highways in Belgium (Schreuer Citation2017).

5.4.12. Urban lighting: Rhetoric for political activism

The symbolic power of light and architecture has been used increasingly in recent years by various groups to engage the public and relates to the behavioristic semiotic model. Illumination with colors or projections with images and text were temporarily applied mainly to landmark buildings. The design ranged from abstract to figurative imagery and the fields of interest included environment, health, and social issues as well as politics. Iconic design solutions were used to ensure a wide response for mass communication in printed and social media.

The annual Earth Hour has turned into a global event to raise awareness of energy consumption and light pollution (World Wide Fund for Nature Citation2018). With its 1-h duration for turning off the illumination, the effect can be regarded as symbolic and not as a significant influence on the total lighting energy consumption. Famous landmarks like the Eiffel Tower play an important role to gain widespread attention. In contrast, artists considered projected animations of endangered species for their environmental campaign on the Empire State Building (Roston Citation2015). Again, the selection of a building with a global status was essential for press communication.

To focus on health issues like the World AIDS Day, text projections on several buildings were used to create awareness (Mixter Citation2018). Alternatively, the campaign against autism was more abstract and used blue light on World Autism Awareness Day (Autism Speaks Citation2018).

In opposition to the general projections onto façades, an art project in Sydney activated residents of two 30-story residential buildings to create an architectural light sculpture with light from within () (Harmon Citation2017). All participants received a color-changing luminaire for their window with a remote control to individually express their mood using constant color or strobe or flash. The protest was targeted against the demolition and privatization for a large inner-city real estate development and gained international press publicity.

Fig. 15. Hongkong and Shanghai Bank Headquarters, Hong Kong, in 2015. Architects: Foster + Partners. Photographer: Simon McCartney. Image © illumination Physics.

Political initiatives address issues like economy and terrorism. During the Occupy Wall Street movement, activists utilized text projection to summarize the protest of a march (Jardin Citation2011). Later, the New York art-activist collective “The Illuminator” used a van for optimum mobility for various events, which raised and lowered a projector through the roof and applied software that also allowed writing on buildings in light in real time. Light installations to commemorate tragic attacks by terrorists started with the “Tribute to Light” in New York in memory of the people killed on September 11, 2001 (National September 11 Memorial Museum Citation2018). The twin beams reached up into the sky and became an annual event. The worldwide terror threats led to global acts of solidarity and sympathy after terror attacks—for example, after incidents in Paris in 2015 and Brussels and Berlin in 2016—where international landmarks were highlighted with the color code of the respective nation (The Guardian Citation2015).

6. Limitations

The main critic against interpreting architecture as language lies in the aspect that architecture does not fulfill the two basic requirements for language: Parts of buildings do not create a vocabulary that creates certain meanings based on lexical rules and neither do syntactic rules exist for the way in which the meaning of complete buildings results from their parts (Baumberger Citation2014). The aspect of light as a medium additionally raises the argument that light can only be perceived via a reflective surface and therefore does not represent an independent language.

Fig. 16. #WeLiveHere2017 Community light project, Waterloo, Sydney, Australia, 2017, www.welivehere2017.com.au. Image by Jessica Hromas. © Jessica Hromas for #WeLiveHere2017.

6.1. Limitations for Architectural Semiotics

Critiques against architectural semiotics have been published by several authors. One problem of a linguistic view of architecture began with the different assumptions about the nature of language (Scruton Citation1979). Many writers mixed language with style, argued Scruton. Furthermore, he differentiated natural and intentional signs and concluded that architectural signs are rather natural but a code is not necessarily involved. It is also important to critically reflect on the perspective of the discourse, because interpretations can vary, depending on whether the analysis has a historical or stylistic focus or alternatively a functional or typological emphasis (Bonta Citation1979). For instance, when one depicts problems in the building type or in certain façade details, the typological or morphological similarities would be more important than historical links.

The analogy between architecture and language is tempting for the issue of meaning in architecture, but several criteria for language proved architecture to be nonlinguistic (Donougho Citation1987). Due to the opposition of form and content in combination with architecture as a field where the form appears to be paramount, one could detect attempts to isolate the content. This tendency marked a shift toward a discourse in an aesthetic of form rather than a semiotic discussion (Munro Citation1987).

Another reaction to very abstract semiotic analyses was the introduction of socio-semiotics, where the connotative codes were interpreted as products produced by groups and classes connected with urban life (Gottdiener and Lagopoulos Citation1986). One example is the legacy of Lynch, with his publication of the five features of paths, edges, districts, nodes, and landmarks as urban reference points, which reduced the use of urban environment to the activity of movement and did not consider the role of ideology according to Gottdiener and Lagopoulos. This urban view is particularly relevant for creating urban lighting and the creation of master plans.

For Harries, the fascination between linguistics and architecture was linked with the crisis of modern architecture, where meaning had been lost and critics had looked for more complex reflections (Harries Citation1997). He questioned whether objects could send an intentional message. For instance, if we call a cloud a sign of rain, it seems inappropriate to assume that this cloud wants to tell us something. Transferred to lighting, this would mean that we understand the sun as a sign of light. In the context of ancient Egypt, the sun was regarded as a sign linked to the solar deity Ra and could consequently be interpreted as a sign, but within modern natural sciences this intention of the sun is not given.

Furthermore, Harris warned that the use of words like “language,” “syntax,” and “grammar” could confuse more than they are able to explain. In a language, specific words can replace each other in a sentence whereas others cannot. For example, a window frame within a wall could be filled with stained glass or with simple transparent glass. This would be equivalent to introducing a word from another language. Filling the window frame with a brick wall would generate architectural nonsense, but we could imagine that a deconstructive or postmodern architect could attempt to do such construction. Certain brands, for example, break the role of good visibility in their stores in order to offer customers an abnormal mysterious appearance within a dark space (Schielke Citation2014).

Additionally, Harries referred to Eco when he mentioned that objects must communicate or denote their function and that this needs to be supported by existing codification. This aspect becomes apparent when new elements like light control interfaces are introduced with a radical new look. As a result, in his critique of symbols, Harries preferred to speak about architecture as representation and to ascribe a pictorial function. He exemplified this perspective with the medieval church and the use of gold and especially illuminated with flickering candles. The shimmering gold was a metaphorical device related to passages from the Bible and should transport the faithful from this world into “the True Light” (Harries Citation1997). The stained glass window was another metaphorical device for Harries. Here Harries indicated that we consider such language of light today as merely metaphorical, but for the medieval artist’s worldview, light was spiritual and the bridge to the sacred sphere.

Due to the linguistic- and image-orientated concepts of the sign theories by Ferdinand de Saussure, Charles S. Peirce, Nelson Goodman, and Umberto Eco, Gleiter suggested extending the semiotic model with phenomenology (Gleiter Citation2014). For him, architectural signs included three aspects: pictorial, phenomenological, and performative. From a distance, a window may appear as a pictorial sign. Being close to a window, it may appear as a real window for looking out and that it can be opened. If a person actually looks out of the window or opens it, a shift from the phenomenological aspect toward the performative begins.

6.2. Limitations for Lighting Design Semiotics

In general, the critique regarding architectural semiotics cannot be removed for architectural lighting, and some arguments have already been illustrated in terms of light. But due to the fact that we see only reflected light, the aspect of light is inherent to our observation of architectural forms, contours, textures, and materials. However, the dimension of either daylight or illumination is seldom addressed. It appears that the image of light emerges as another layer on the architectural surface. However, the rays of sunlight do not stop at the surface, but they are reflected and thereby influence the appearance of other areas as well. A discussion of light as a language independent from architecture seems absurd. But a semiotic perspective can help to identify the two elements of light and architecture and to describe their relationship; for example, as a unity, contrast, transformation, or exaggeration. For instance, a space with designed white walls generates a unity with reference to material and color. Considering downlights with their characteristic scallop pattern on the upper part of walls dissolves the unity, whereas a uniform lighting distribution of wallwashers enhances the spatial unity (Schielke Citation2013).

Hill responded to the issue of reflectivity on surfaces as well when he criticized Scruton’s arguments with realistic and nonrealistic subcategories (Hill Citation1999). When seeing physical objects like façade constructions creating patterns of bright light and shadow, one could assign a realistic seeing in Scruton’s terms. But the case is more problematic when the overall space is considered and we see a quality of calm and clarity of the light and raise the question of whether this should be regarded as nonrealistic seeing according to Scruton. Hill suggested solving this problem by interpreting light as reflectivity on surfaces. In the first step, the individual surfaces would be construed as realistic seeing, which would be equivalent with Scruton’s realistic perception. In the second step, the light in the space would be understood as an imaginative object, which would relate to the nonrealistic perception. An option for Hill was the idea that a space has characteristics, one of which is the quality of light. According to Hill, light moves people. He illustrated this with John Soane’s architecture and argued that the aesthetic perception does not derive from manipulating surfaces with color, decoration, and mirrors.

From a linguistic point of view, with morphemes as the minimal distinctive unit of grammar, light could be considered as a bound morpheme, which is linked to the architectural element. It requires architecture to alter the meaning (Crystal Citation2008). In this way light becomes a derivational affix. This means that as an affix it cannot exist without the morpheme of the respective architectural element, but as an affix it builds a new word in combination with the architectural unit and carries a new meaning.

Critique with regard to communication theory and light was brought forward by McLuhan, who said that light is not a medium and electric light is pure information, unless it is used to spell out some verbal advertisement or name (McLuhan Citation1964). This statement was developed from his understanding that a society is influenced more by the media used than the topics within this medium. However, this intense focus on the medium also implies that the content and social dimension of media are neglected. It is obvious from the different above-mentioned case studies that the content of the medium light has a substantial effect and is relevant for the resulting reactions by people and society.

7. Conclusion

Applying semiotics directs the focus on the quality of lighting design. Considering the meaning of light within the design process leads to more sustainable solutions with an optimization beyond the widely discussed economic and performance factors like efficiency or visibility. Semiotics can serve as a tool to understand architecture and lighting regarding their signifying dimension and to identify the meaning. This view is based on the concept that lighting conveys a meaning next to the function of visibility and safety.

The strength of the semiotic method lies in the ability to analyze complex systems of signs that lighting designers deal with: light sources, luminaires, integration in architecture, and illuminated interior spaces, up to urban design. This approach offers a variety of perspectives to imagine and analyze the structural rules of the lighting design composition, the relationship between the light-filled space and the meaning, and how people respond to light.

Theories of architectural semiotics offer a valuable background for transferring the method to architectural lighting design. The semiotic matrix offers a differentiated view of relationships based on the aspects of sign, object, and interpreter in relation to light characteristics, illuminated building, and architectural lighting in general. Depending on the research problem, the emphasis of the semiotic approach is adjustable. Academics have pointed out several aspects where the applications of semiotics could lead to problems; for instance, when semiotics bases everything on signs or words and moves away from perception without using words like the phenomenological perspective with emotion and presence. A semiotic analysis considering only light without architecture is short-sighted as well. However, the critique does not question the use of semiotics for architecture and light in general but focuses on structural details.

Addressing the meaning of light could also benefit the debate about human-centric lighting and its search to include the usefulness of lighting. With this methodological potential, semiotics deserves a larger recognition not only within the lighting research community but also for practitioners, educators, and critics.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Anderson J. 2012. Environmental Impact of Light Pollution and its Abatement. Toronto (ON).

- Anselmo F, Mardaljevic J. 2013. Vernacular windows. Daylight & Architecture. 25-33.

- Babin B, Hardesty DM, Suter TA. 2003. Color and shopping intentions. The Intervening Effect of Price Fairness and Perceived Affect. Journal of Business Research. 56:541-551. doi:10.1016/S0148-2963(01)00246-6.

- Barthes R. 1997. The Eiffel Tower and other mythologies. Berkeley (CA): University of California Press.

- Baumberger C. 2010. Gebaute Zeichen. In Eine Symboltheorie der Architektur. Heusenstamm: Ontos.

- Baumberger C. 2014. Neue Arbeiten zur Architektursemiotik: zur Einführung. Zeitschrift Für Semiotik. 36:3-12.

- Bellizzi JA, Hite RE. 1992. Environmental color, consumer feelings, and purchase likelihood. Psychology and Marketing. 9:347-363. doi:10.1002/mar.4220090502

- Bense M, Walther E. 1973. Wörterbuch der Semiotik. Köln (Germany): Kiepenheuer und Witsch.

- Benya JR. 2015. Nights in Davis: the initial LED streetlight installation went awry, but this story has a happy ending. Lighting Design and Application; p. 32-34.

- Bodgrogi P, Vinh QT, Khanh TQ. 2017. Opinion: the usefulness of light sources in human centric lighting. Lighting Research and Technology. 49:292. doi:10.1177/1477153517707427

- Bonta JP. 1979. Architecture and its interpretation: A study of expressive systems in architecture. London (UK): Lund Humphries.

- Boyce PR. 2014. Human Factors in Lighting. Boca Raton (FL): CRC Press.

- Butterfield J. 1993. The art of light + space. New York (NY): Abbeville Publishing Group.

- Chayka K. 2016. The Oppressive Gospel of “Minimalism.” New York Times [accessed 2018 Apr 21]. Available from: https://mobile.nytimes.com/2016/07/31/magazine/the-oppressive-gospel-of-minimalism.html.

- Corbusier L. 1927. Towards a new architecture. London (UK): Architectural Press.

- Crowley AE. 1993. The two-dimensional impact of color on shopping. Marketing Letters. 4:59-69.

- Crystal D. 2008. A dictionary of linguistics and phonetics. Malden (MA): Blackwell Publishing.

- De Fusco R. 1972. Architektur als Massenmedium. Gütersloh (Germany): Bertelsmann-Fachverlag.

- Delitz H. 2010. Gebaute Gesellschaft. Architektur als Medium des Sozialen. Frankfurt (Germany): Campus.

- Djalali A. 2017. Eisenman beyond Eisenman: language and architecture revisited. The Journal of Architecture. 22:1287-1298. doi:10.1080/13602365.2017.1394350

- Donougho M. 1987. The Language of Architecture. Journal of Aesthetic Education. 21:53-67.

- Downs H, Wright FL. 1953. A Conversation with Frank Lloyd Wright. USA: produced by King Studios for the National Broadcasting Company. Evanston (IL): Citadel Video; p. 1993.

- Eco U. 1972. Einführung in die Semiotik. München: Fink.

- Edensor T. 2013. The gloomy city: rethinking the relationship between light and dark. Urban Studies. 52:422-38. doi:10.1177/0042098013504009

- Elgala H, Mesleh R, Haas H 2011. Indoor Optical Wireless Communication: Potential and State-of-the-Art. IEEE Communications Magazine: 56-62.

- Evitts DE. 2012. Night Light. Architectural Lighting [accessed 2017 Dec 29]. Available from: http://www.archlighting.com/projects/night-light_o.

- Fiell P, Fiell C. 2013. 1000 Lights. Cologne (Germany): Taschen.

- Frampton K. 2007. Modern architecture. In A critical history. London (UK): Thames & Hudson.

- Gleiter JH. 2014. Die Präsenz der Zeichen: vorüberlegungen zu einer phänomenologischen Architektursemiotik. Zeitschrift Für Semiotik. 36:25-47.

- Goodman N. 1968. Languages of Art. In An Approach to a Theory of Symbols. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merril.

- Gottdiener M, Lagopoulos AP. 1986. The city and the sign. New York (NY): Columbia University Press.

- Groat L, Wang D. 2002. Architectural Research Methods. New York (NY): Wiley.

- Haddad E. 2010. Christian Norberg-Schulz’s Phenomenological Project in Architecture. Architectural Theory Review. 15:88-101. doi:10.1080/13264821003629279

- Haeulser MH. 2009. Media Facades. In History, Technology, Content. Ludwigsburg (Germany): av edition.

- Harmon S 2017. “These are people’s homes’: the art project making public housing in Sydney’s Waterloo glow. the guardian [accessed 2018 Jan 13]. Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2017/sep/06/these-are-peoples-homes-the-sydney-art-project-making-public-housing-glow.

- Harries K. 1997. The Ethical Function of Architecture. Cambridge (MA): The MIT Press.

- Hattenhauer D. 1984. The rhetoric of architecture: A semiotic approach. Communication Quarterly. 32:71-77. doi:10.1080/01463378409369534

- Hill R. 1999. Designs and their consequences. In Architecture and aesthetics. New Haven (CT): Yale University Press.

- Innes M. 2012. Lighting for interior design. London (UK): Laurence King Publishing.

- Jackson D, Kyriakou M-A, Petresin V, Schielke T, Weibel P. 2015. SuperLux. In Smart Light Art, Design & Architecture for Cities. London (UK): Thames & Hudson.

- Jardin X. 2011. Interview with creator of Occupy Wall Street “bat-signal” projections during Brooklyn Bridge #N17 march. Boing Boing [accessed 2018 Jan 13]. Available from: https://boingboing.net/2011/11/17/interview-with-the-occupy-wall.html.

- Jencks C. 1977. The Language of Post-Modern Architecture. London (UK): Academy Editions.

- Jencks C. 2005. The iconic building: the power of enigma. London (UK): Frances Lincoln.

- Jencks C, Baird G. 1969. Meaning in Architecture. London (UK): Barrie & Jenkins.

- Kaplan R, Kaplan S. 1989. The Experience of Nature. Cambridge (MA): Cambridge University Press.

- Karanouh A, Kerber E. 2015. Innovations in dynamic architecture. Journal of Facade Design and Engineering. 3:185-221. doi:10.3233/FDE-150040

- Kelly K. 2017. A different type of lighting research – A qualitative methodology. Lighting Research & Technology. 49:933-942.

- Kelly R. 1952. Light as an Integral Part of Architecture. College Art Journal. 12:24-30. doi:10.1177/1477153516659901

- Koenig GK. 1964. Analisi del linguaggio architettonico. Florence (Italy): Fiorentina.

- Krautter M, Schielke T. 2009. Light perspectives between culture and technology. Lüdenscheid (Germany): ERCO.

- Kress G, Van Leeuwen T. 2002. Colour as a semiotic mode: notes for a grammar of colour. Visual Communication. 1:343-368. doi:10.1177/147035720200100306

- Kyba CCM, Kuester T, Sánchez De Miguel A, Baugh K, Jechow A, Hölker F, Bennie J, Cd E, Kj G, Guanter L. 2017. Artificially lit surface of Earth at night increasing in radiance and extent. Science Advances. 3:e1701528.

- Lagopoulos AP. 1993. Postmodernism, geography, and the social semiotics of space. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space. 11:255-278. doi:10.1068/d110255

- Lam WMC. 1960. Lighting for Architecture. Architectural Record. 127:219-229.

- Lam WMC. 1977. Perception and lighting as formgivers for architecture. New York (NY): McGraw-Hill.

- Luhmann N. 1995. Social systems. Stanford: (CA) Stanford University Press.

- Madden TJ, Hewett K, Roth MS. 2000. Managing Images in Different Cultures: A Cross-National Study of Color Meanings and Preferences. Journal of International Marketing. 8:90-107. doi:10.1509/jimk.8.4.90.19795.

- Major M, Speirs J, Tischhauser A. 2005. Made of Light: the Art of Light and Architecture. Basel (Germany): Birkhäuser.

- Mansfield KP. 2018. Architectural lighting design: A research review over 50 years. Lighting Research and Technology. 50:80-97. doi:10.1177/1477153517736803

- May S. 2004. Olafur Eliasson: the Weather Project. London (UK): Tate.

- McCandless S. 1939. A Method of Lighting the Stage. New York (NY): Theatre Arts Inc.

- McLuhan M. 1964. Understanding media: the extensions of man. New York (NY): McGraw-Hill.

- Medway P, Clark B. 2003. Imagining the building: architectural design as semiotic construction. Design Studies. 24:255-273. doi:10.1016/S0142-694X(02)00055-8

- Mitchell WJ. 1990. The logic of architecture. In Design, computation, and cognition. Cambridge (MA): The MIT Press.

- Mixter W. 2018. “Radiant Presence” Marks World AIDS Day with Guerrilla Slideshow. hoodline [accessed 2018 Jan 13]. Available from: http://hoodline.com/2015/12/radiant-presence-marks-world-aids-day-with-guerrilla-slideshow.

- Moran N. 2007. Performance Lighting Design: how to light for the stage, concerts and live events. Bloomsbury (UK): London.

- Munro CF. 1987. Semiotics, Aesthetics and Architecture. The British Journal of Aesthetics. 27:115-128. doi:10.1093/bjaesthetics/27.2.115

- National September 11 Memorial Museum. 2018. Tribute in Light. National September 11 Memorial Museum [accessed 2018 Jan 13]. Available from: https://www.911memorial.org/tribute-light.

- Neumann D. 2002. Architecture of the night: the illuminated building. Munich: (Germany) Prestel.

- Neumann D. 2010. The Structure of Light. In Richard Kelly and the Illumination of Modern Architecture. New Haven (CT): Yale University Press.

- Nöth W. 1990. Handbook of Semiotics. Indianapolis (IN): Indiana University Press.

- Paris attacks: buildings around the world are lit up in honour of the victims of Friday 13. 2015. https://www.theguardian.com/world/gallery/2015/nov/14/paris-attacks-memorials-victims-friday-13 [ accessed 2018 Jan 13].

- Plummer H. 1995. Light in Japanese Architecture. Tokyo (Japan): Architecture and Urbanism.

- Plummer H. 2003. Masters of light. In First volume: twentieth-century pioneers. Tokyo (Japan): Architecture and Urbanism.

- Prak NL. 1968. The language of architecture. Nijmegen (Netherlands): Mouton.

- Preziosi D. 1979. Architecture, Language, and Meaning. Mouton (Germany): The Hague.

- Pridmore J. 2003. The Rookery: A Building Book from the Chicago Architecture Foundation. Rohnert Park (CA): Pomegranate Communications.

- Remei C-W. 2014. Restaurierte und rekonstruierte Zeichen: symbole und Baudenkmalpflege. Zeitschrift Für Semiotik. 36:125-150.

- Riley H. 2004. Perceptual Modes, Semiotic Codes, Social Mores: A Contribution towards a Social Semiotics of Drawing. Visual Communication. 3:294-315. doi:10.1177/1470357204045784

- Rockcastle S, Andersen M. 2013. Celebrating Contrast and Daylight Variability in Contemporary Architectural Design: A Typological Approach. Krakow (Poland):

- Roston T. 2015. Illuminating the Plight of Endangered Species, at the Empire State Building. New York Times [accessed 2018 Jan 13]. Available from: https://www.nytimes.com/2015/07/31/movies/illuminating-the-plight-of-endangered-species-at-the-empire-state-building.html?smid=pin-share.

- Rozot N, Peón-Veiga A. 2010. Drawing Light: A Graphical Investigation of Light, Space, and Time in Lighting Design. Parsons Journal for Information Mapping. 2:1–13.

- Ruby I, Ruby A, Ursprung P. 2004. Images. In A Picture Book of Architecture. München (Germany): Prestel.

- Ruxton I 2011. The meaning of light – towards a taxonomy of illuminatory semiotics. In: PLDC 3rd Global Lighting Design Conference. Madrid (Spain): Via Verlag.

- Sadowski P. 2017. The Semiotics of Light and Shadows. In Modern Visual Arts and Weimar Cinema. London (UK): Bloomsbury.