?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Objective

Prepulse inhibition regulates sensorimotor gating and is a marker of vulnerability to certain disorders. We compared prepulse inhibition, psychopathy, and sensitivity to punishment and reward in patients with cocaine-related disorder without psychiatric comorbidities and a control group.

Methods

This was an observational study of a sample of 22 male cases with cocaine-related disorder and 22 healthy male controls. We used the Psychiatric Research Interview for Substance and Mental Disorders and Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview; the Sensitivity to Punishment and Sensitivity to Reward Questionnaire; and the Levenson Self-Report Psychopathy Scale and Hare Psychopathy Checklist-Revised. Prepulse inhibition was evaluated at 30, 60, and 120 ms.

Results

Cocaine-related disorder group had a higher overall score (t = 12.556, p = .001) and primary psychopathy score (t = 3.750, p = .001) on Levenson Self-Report Psychopathy Scale, a higher score on both Hare Psychopathy Checklist-Revised factors, sensitivity to rewards (t = 3.076, p = .005) and prepulse inhibition at 30 ms (t = 2.859, p = .008).

Conclusions

Cocaine use in patients without psychiatric comorbidities seems to increase sensorimotor gating. Therefore, these patients likely have an increased sensitivity to rewards, causing them to focus more on cocaine-boosting stimuli, thus explaining the psychopathic traits of these individuals.

Prepulse inhibition (PPI) of the startle reflex is defined as a reduction in the magnitude of this reflex when a low-intensity auditory stimulus occurs which would normally be unable to generate a response by itself (prepulse) 30–300 ms (millisecond) before the onset of a startle stimulus (pulse). It has been described as an operational measure of a central inhibitory mechanism that regulates sensorimotor gating, reducing the impact of irrelevant sensory stimuli. Therefore, an impairment of this mechanism expressed as a lack of attenuation of the reflexive startle reaction after the onset of auditory stimulus (prepulse-pulse) can be used as an endophenotype or biological marker of vulnerability to certain mental disorders such as schizophrenia (Kohl et al., Citation2013). Furthermore, it has been well documented that the duration of the prepulse-pulse interval helps define the type of processing taking place. Shorter intervals like 30 ms, respond to pre-attentive and automatic perceptual processing whereas longer intervals like 120 ms are defined as partially automatic, meaning they are capable of proceeding automatically but also of controlled attentional modulation (Schell et al., Citation2000).

According to the European Drug Report 2019, cocaine is the most commonly used illegal stimulant drug in Europe, with 1.2% of the population having consumed it in 2018 (European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction, Citation2019). The Survey on Alcohol and Drug use in Spain (Observatorio Español de las Drogas y las Adicciones, Citation2019) reported a somewhat higher figure than the European average (2.2%). In Spain, the prevalence of mental disorders in cocaine users (dual pathology) ranges between 61.8% and 73.4%, with psychotic disorders (15.5%) and antisocial personality disorder (20%) being two of the most prevalent combinations (Araos et al., Citation2014).

Concerning cocaine dependence (CD), it is evidenced that cocaine decreases PPI through postsynaptic dopamine receptors in animal models (Doherty et al., Citation2008). However, studies of the relationship between PPI and CD in humans have yielded conflicting results. On one hand, deficits in PPI have been identified upon the acute administration of cocaine, but on the other, the chronic administration of cocaine appears to normalize PPI (Arenas et al., Citation2017). A decrease in PPI has also been described during periods of substance withdrawal (Corcoran et al., Citation2011). However, Preller et al. (Citation2013) showed that recreational consumers and patients with CD showed an increase in PPI compared to controls. Therefore, the relationship between PPI and dopamine is neither simple nor unidirectional and its association with CD remains controversial (Martinez et al., Citation2007). Conflicting results have also been published with regards to the relationship between PPI and psychopathy (De Pascalis et al., Citation2019; Kumari et al., Citation2005).

Patients with CD but without any comorbidities are very uncommon; however, they constitute a population with behavioral problems and there is a lack of specific pharmacological treatments for these patients at present. Chronic cocaine users display neurochemical and functional alterations in brain areas involved in the regulation of social cognition (Volkow et al., Citation2011). This may increase social isolation which might lead to a vicious circle of drug use (Homer et al., Citation2008). Preller et al. (Citation2014) showed that recreational and dependent use of cocaine was associated with impairments in emotional empathy and mentalizing abilities.

Considering this above-mentioned literature, one of the research questions posed was whether PPI was related to the psychopathic traits shown by CD patients. Our primary hypothesis proposes that patients with CD and no comorbidities will have higher PPI than controls because they have shown greater restricted interest in drug-seeking behavior and consumption, specifically better at filtering non-drug-related stimuli (irrelevant and relevant). The secondary hypothesis proposes that CD patients will have an increase in psychopathic personality traits, which relate to PPI abnormalities, when compared to controls. A better understanding of PPI in this population could contribute to existing knowledge about the development of such behaviors and aid in the future development of new therapeutic strategies to curb these behaviors.

Methods

This was an unblinded, observational, cross-sectional study of cases and controls. A sample of 22 cases with CD, without psychiatric comorbidities, was identified from a population of 128 men aged over 18 years. Other substance use disorders were also accepted in this group. The 22 cases were analyzed when undergoing treatment for CD while interned at the Consorcio Hospitalario Provincial Detoxification Unit (Castellon, Spain). A sample of 22 men over 18 years of age and with no personal or family history of psychiatric or substance use disorders was recruited by convenience sampling at Consorcio Hospitalario Provincial’s open days and was used as the control group.

In order to diagnose CD, exclude the presence of other psychiatric diagnoses, and detect other substance use disorders from a categorical perspective, the Psychiatric Research Interview for Substance and Mental Disorders (PRISM-IV) (Torrens et al., Citation2004) and the Dual Diagnostic Screening Interview (DDSI) (Mestre-Pintó et al., Citation2014) were used. To confirm the absence of any mental disorders or addictions in the control group, the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI-5.0) (Sheehan et al., Citation1998) was performed and a drug urine toxicity test was performed to rule out active drug consumption. The psychopathy of both groups was assessed using the Levenson Self-Report Psychopathy Scale (LSRP) (Levenson et al., Citation1995) and Hare Psychopathy Checklist-Revised (PCL-R) (Hare, Citation2003). Additionally, the Sensitivity to Punishment and Sensitivity to Reward Questionnaire (SPSRQ) (Torrubia et al., Citation2001) was performed.

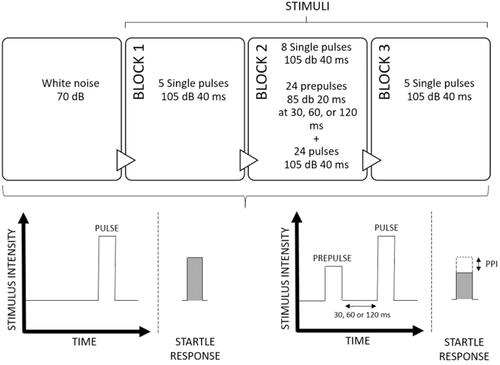

PPI was assessed in order to evaluate sensorimotor gating by using a BIOPAC MP150 Quick-Start research system, following the same protocol used by authors in a previous study (Fuertes-Saiz et al., Citation2019) as shown in . Participants could not smoke or drink coffee for 1 h before the test. The CD group was assessed when psychopathological stability was achieved after 7–10 days of treatment in the Detoxification Unit. All participants received white noise at 70 dB, followed by three blocks of stimuli. The first block consisted of five single pulses. The second block consisted of eight single pulses and 24 pulses preceded by a prepulse at 30, 60, or 120 ms. The third block was the same as the first one. The pulse intensities were 105 dB and lasted 40 ms and the prepulse intensities were 85 dB and lasted 20 ms. The three main dependent variables were the PPI percentages with prepulse at 30, 60, and 120 ms calculated as: {[(response strength for the single pulse) − (response strength for the pulse preceded by the prepulse)] ÷ (response strength for the single pulse)} × 100.

SPSS software (version 21) for Microsoft (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY) was used for all the statistical analyses. After the exploratory and descriptive study, the sociodemographic variables were compared using Student’s t-tests for quantitative variables and chi-squared tests for categorical variables. Correlations between dependent variables were calculated using Pearson’s correlation coefficient. Because dependent variables were correlated, we performed a MANOVA. A series of independent t-tests were used to evaluate differences between CD patients and controls on SPSRQ, LSRP, and PCL-R scores. Mixed ANOVA was used to assess differences in prepulse inhibition (PPI) between groups, with prepulse interval (30, 60, and 120 ms) serving as a within-subject factor and group (CD vs. control) as a between-subject factor. Post-hoc comparisons were done using Tukey’s test. The study was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki guidelines (World Medical Association, Citation2013). There was a complete discussion of the study with potential participants and written informed consent was obtained after this discussion. The study was approved by the institutional review boards of both CEU-Cardenal Herrera University and Consorcio Hospitalario Provincial in Castellon.

Results

The average participant age was 40.71 years (SD = 10.13) and there were no significant differences between the groups. However, patients with CD were more often single ( = 19.82; p < .001), had lower education levels (

= 12.92; p = .019), and were more often unemployed (

= 24.50; p < .001) than the control group. No differences were found in terms of the time either group had spent incarcerated. Subjects with CD were chronic cocaine users, with a mean duration of use equaling 18.52 years (SD = 8.97) and a mean duration of addiction equaling 12.88 years (SD = 8.13). Half of the patients with CD were polyconsumers: 36.4% depended on cannabis (n = 8), 31.8% on alcohol (n = 7), 22.7% on heroin (n = 5), and 9.1% on sedatives (n = 2) or stimulants (n = 2). shows characteristics of addictions in the CD group.

Table 1. Characteristics of Addictions.

PPI at 30 ms was related to LSRP score,both primary (rho = .521, p = .005) and secondary psychopathy (rho = .407, p = .035), and reward sensitivity (rho = .459, p = .016). At 120 ms, PPI was related to secondary psychopathy (rho = .473, p = .017). In the CD group, PPI at 30 ms and 60 ms was related to the number of years of patient addiction (rho = −.941, p = .002 and rho = −.977, p = .001), and at 60 ms, it was related to the age of addiction onset (rho = .824, p = .044).

MANOVA found that there was a difference between the groups in the dependent variables (F = 44.945; p < .001). The patients with CD were not actively consuming drugs, did not have an antisocial personality disorder or any other comorbidities, presented greater levels of primary psychopathy (according to the total LSRP score and both PCL-R factors), and based on the SCSR scores, were more sensitive to rewards ().

Table 2. Comparisons of the Scores for the Dependent Variables (Activation, Behavioral Inhibition, and Psychopathy) in the Group With a Cocaine Dependence and Controls Without a Cocaine Addiction.

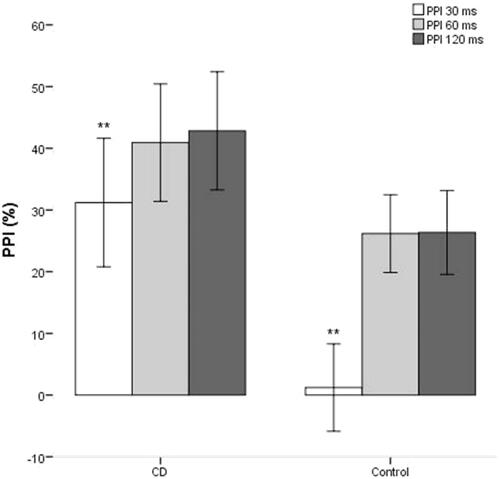

In the ANOVA, there was a principal effect of prepulse interval (F = 7.926; p = .001). There were no effects of group and interaction. IPP was lower at 30 ms than in 60 ms (p = .002) and 120 ms (p = .003). Although shows a trend toward greater prepulse inhibition in CD patients compared to controls, post-hoc test showed a statistically significant difference in PPI between CD patients and controls only for the 30 ms prepulse interval ( CD = 38.67, SD = 23.04;

controls = 1.21, SD = 31.67; t = 2,859; p = .008).

Discussion

The results of this study confirm our primary hypothesis and support those of Preller et al. (Citation2013): patients with cocaine dependence have a higher PPI at 30 ms than non-consumers. This could point to the fact that in patients without comorbidities, cocaine use increases sensory filtering. However, in patients with dual pathologies, such as antisocial personality disorder or schizophrenia, such consumption likely fails to normalize the base deficit that these patients present (Fuertes-Saiz et al., Citation2019). In contrast, some antipsychotics have shown the ability to normalize sensory filtering in patients with schizophrenia and without comorbidities (Li et al., Citation2019).

Although cross-sectional studies are unable to infer causality, the results support our secondary hypothesis proposing that CD patients will have an increase in psychopathic personality traits, which relate to PPI abnormalities, when compared to controls. According to the LSRP scale and PCL-R, patients with CD without comorbidities (including antisocial personality disorder), present mild psychopathic traits and increased sensitivity to rewards operationalized as an increase in 30 ms PPI. Increased PPI has been related to the reinforcement sensitivity theory as well as increased psychopathy (De Pascalis et al., Citation2019). The Ventral Tegmental Area modulates sensitivity to rewards, and self-administration of cocaine induces long-term potentiation-like synaptic changes in dopaminergic neurons from the Ventral Tegmental Area (Sarti et al., Citation2007). These changes have been maintained more than 3 months after abstinence (Chen et al., Citation2008) making sensitivity to rewards a stable trait in short-term abstinence.

We suggest that cocaine use increases the most pre-attentional and therefore automatic stages of sensory filtering (30 ms). Therefore, due to the lack of control in automatic stimulus processing, these patients would have an increased sensitivity to rewards, causing them to focus more on cocaine-boosting stimuli and less on the negative consequences of these on their personal relationships and behaviors. This could explain both the primary psychopathic traits of these individuals such as lack of empathy, as well as their secondary psychopathic traits including antisocial behavior. Thus, the capacity of patients to inhibit the startle reflex could be a basic physiological expression of psychopathy, both in the general population (De Pascalis et al., Citation2019) and in patients with CD.

It is important to note that this study, like others examining PPI, had some limitations. First, because PPI varies according to sex, we made a methodological decision to only include male patients in the study cohort in order to avoid possible biases (Kumari et al., Citation2004). This makes our results not applicable to female patients. Second, the high percentage of polyconsumption may have hindered the assignment of PPI results to cocaine use. However, this is advantageous in terms of the extrapolation of our results to the general population of consumers because polyconsumption is the norm (Walderhaug et al., Citation2019). Third, our sample showed high severity and duration of addiction and although patients were reportedly stable as assessed by their psychiatrist when measuring PPI, withdrawal symptoms were not specifically assessed. This limitation must be considered when extrapolating the results. Fourth, LSRP and PCL-R correlate only moderately, which implies these two measures may be measuring somewhat different constructs of the psychopathy spectrum. In the case of LSRP, there is controversy about whether the latent structure is of two or three factors (Psederska et al., Citation2020). Lastly, the cognitive burden needed, and the risk of recall bias when answering questions in patients completing scales (e.g., LSRP) may result in lower quality of data.

Therefore, we suggest that cocaine dependence could increase psychopathic traits by modulating PPI in male polydrug patients without other psychiatric comorbidities (and therefore, patients presumably without deficits in sensorimotor gating). Thus, cocaine use in patients without any comorbidities seems to increase sensory filtering. Hence, these patients have increased sensitivity to rewards, causing them to focus more on cocaine-boosting stimuli and less on the negative consequences of these on their personal relationships and behavior, thereby explaining the psychopathic traits of these individuals.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all team members of TXP Research Group, CEU-Cardenal Herrera University and the Research Foundation of the Hospital Provincial de Castellón for their support with the research project.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Araos, P., Vergara-Moragues, E., Pedraz, M., Pavón, F. J., Campos Cloute, R., Calado, M., Ruiz, J. J., García-Marchena, N., Gornemann, I., Torrens, M., & Rodríguez de Fonseca, F. (2014). Psychopathological comorbidity in cocaine users in outpatient treatment. Adicciones, 26(1), 15–26. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.20882/adicciones.124

- Arenas, M. C., Caballero-Reinaldo, C., Navarro-Francés, C. I., & Manzanedo, C. (2017). Efecto de la cocaína sobre la inhibición por prepulso de la respuesta de sobresalto [Cocaine effect on prepulse inhibition of startle response]. Revista de Neurología, 65(11), 507–519. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.33588/rn.6511.2017298

- Chen, B. T., Bowers, M. S., Martin, M., Hopf, F. W., Guillory, A. M., Carelli, R. M., Chou, J. K., & Bonci, A. (2008). Cocaine but not natural reward self-administration nor passive cocaine infusion produces persistent LTP in the VTA. Neuron, 59(2), 288–297. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2008.05.024

- Corcoran, S., Norrholm, S. D., Cuthbert, B., Sternberg, M., Hollis, J., & Duncan, E. (2011). Acoustic startle reduction in cocaine dependence persists for 1 year of abstinence. Psychopharmacology, 215(1), 93–103. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-010-2114-2

- De Pascalis, V., Scacchia, P., Sommer, K., & Checcucci, C. (2019). Psychopathy traits and reinforcement sensitivity theory: Prepulse inhibition and ERP responses. Biological Psychology, 148, 107771. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsycho.2019.107771

- Doherty, J. M., Masten, V. L., Powell, S. B., Ralph, R. J., Klamer, D., Low, M. J., & Geyer, M. A. (2008). Contributions of dopamine D1, D2, and D3 receptor subtypes to the disruptive effects of cocaine on prepulse inhibition in mice. Neuropsychopharmacology, 33(11), 2648–2656. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.npp.1301657

- European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction. (2019). European drug report 2019: trends and developments. http://www.emcdda.europa.eu/system/files/publications/11364/20191724_TDAT19001ENN_PDF.pdf

- Fuertes-Saiz, A., Benito, A., Mateu, C., Carratalá, S., Almodóvar, I., Baquero, A., & Haro, G. (2019). Sensorimotor gating in cocaine-related disorder with comorbid schizophrenia or antisocial personality disorder. Journal of Dual Diagnosis, 15(4), 243–253. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15504263.2019.1633489

- Hare, R. D. (2003). Hare Psychopathy Checklist‐Revised (PCL‐R) (2nd ed.). Multi‐Heath Systems.

- Homer, B. D., Solomon, T. M., Moeller, R. W., Mascia, A., DeRaleau, L., & Halkitis, P. N. (2008). Methamphetamine abuse and impairment of social functioning: A review of the underlying neurophysiological causes and behavioral implications. Psychological Bulletin, 134(2), 301–310. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.134.2.301

- Kohl, S., Heekeren, K., Klosterkötter, J., & Kuhn, J. (2013). Prepulse inhibition in psychiatric disorders-apart from schizophrenia. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 47(4), 445–452. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.11.018

- Kumari, V., Aasen, I., & Sharma, T. (2004). Sex differences in prepulse inhibition deficits in chronic schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research, 69(2–3), 219–235. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2003.09.010

- Kumari, V., Das, M., Hodgins, S., Zachariah, E., Barkataki, I., Howlett, M., & Sharma, T. (2005). Association between violent behaviour and impaired prepulse inhibition of the startle response in antisocial personality disorder and schizophrenia. Behavioural Brain Research, 158(1), 159–166. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbr.2004.08.021

- Levenson, M. R., Kiehl, K. A., & Fitzpatrick, C. M. (1995). Assessing psychopathic attributes in a noninstitutionalized population. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 68(1), 151–158. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.68.1.151

- Li, M., Wang, W., Sun, L., Du, W., Zhou, H., & Shao, F. (2019). Chronic clozapine treatment improves the alterations of prepulse inhibition and BDNF mRNA expression in the medial prefrontal cortex that are induced by adolescent social isolation. Behavioural Pharmacology, 30(4), 311–319. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1097/FBP.0000000000000419

- Martinez, D., Narendran, R., Foltin, R. W., Slifstein, M., Hwang, D. R., Broft, A., Huang, Y., Cooper, T. B., Fischman, M. W., Kleber, H. D., & Laruelle, M. (2007). Amphetamine-induced dopamine release: Markedly blunted in cocaine dependence and predictive of the choice to self-administer cocaine. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 164(4), 622–629. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.2007.164.4.622

- Mestre-Pintó, J. I., Domingo-Salvany, A., Martín-Santos, R., & Torrens, M. (2014). Dual diagnosis screening interview to identify psychiatric comorbidity in substance users: Development and validation of a brief instrument. European Addiction Research, 20(1), 41–48. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1159/000351519

- Observatorio Español de las Drogas y las Adicciones. (2019). Encuesta sobre Alcohol y Drogas en España (EDADES), 1995-2017. http://www.pnsd.mscbs.gob.es/profesionales/sistemasInformacion/sistemaInformacion/pdf/2019_Informe_EDADES.pdf.

- Preller, K. H., Hulka, L. M., Vonmoos, M., Jenni, D., Baumgartner, M. R., Seifritz, E., Dziobek, I., & Quednow, B. B. (2014). Impaired emotional empathy and related social network deficits in cocaine users. Addiction Biology, 19(3), 452–466. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/adb.12070

- Preller, K. H., Ingold, N., Hulka, L. M., Vonmoos, M., Jenni, D., Baumgartner, M. R., Vollenweider, F. X., & Quednow, B. B. (2013). Increased sensorimotor gating in recreational and dependent cocaine users is modulated by craving and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms. Biological Psychiatry, 73(3), 225–234. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.08.003

- Psederska, E., Yankov, G. P., Bozgunov, K., Popov, V., Vasilev, G., & Vassileva, J. (2020). Validation of the Levenson self-report psychopathy scale in Bulgarian substance-dependent individuals. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1110. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01110

- Sarti, F., Borgland, S. L., Kharazia, V. N., & Bonci, A. (2007). Acute cocaine exposure alters spine density and long-term potentiation in the ventral tegmental area. European Journal of Neuroscience, 26(3), 749–756. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05689.x

- Schell, A. M., Wynn, J. K., Dawson, M. E., Sinaii, N., & Niebala, C. B. (2000). Automatic and controlled attentional processes in startle eyeblink modification: Effects of habituation of the prepulse. Psychophysiology, 37(4), 409–417. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S0048577200981757

- Sheehan, D. V., Lecrubier, Y., Sheehan, K. H., Amorim, P., Janavs, J., Weiller, E., Hergueta, T., Baker, R., & Dunbar, G. C. (1998). The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): The development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 59(20), 22–57.

- Torrens, M., Serrano, D., Astals, M., Pérez-Domínguez, G., & Martín-Santos, R. (2004). Diagnosing comorbid psychiatric disorders in substance abusers: Validity of the Spanish versions of the Psychiatric Research Interview for Substance and Mental Disorders and the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 161(7), 1231–1237. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.161.7.1231

- Torrubia, R., Avila, C., Moltó, J., & Caseras, X. (2001). The Sensitivity to Punishment and Sensitivity Reward Questionnaire (SPSRQ) as a measure of Gray’s anxiety and impulsivity dimensions. Personality and Individual Differences, 31(6), 837–862. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(00)00183-5

- Volkow, N. D., Baler, R. D., & Goldstein, R. Z. (2011). Addiction: Pulling at the neural threads of social behaviors. Neuron, 69(4), 599–602. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2011.01.027

- Walderhaug, E., Seim-Wikse, K. J., Enger, A., & Milin, O. (2019). Polydrug use - prevalence and registration. Tidsskrift for Den Norske Laegeforening, 139(13). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.4045/tidsskr.19.0251

- World Medical Association. (2013). World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA, 310(20), 2191–2194. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2013.281053