Abstract

Objective

Abstinence has been the primary treatment goal for alcohol and other drug (AOD) users attending withdrawal treatment. However, other outcomes including harm reduction have also been identified. This observational study aimed to describe participants’ goals and reasons for seeking inpatient withdrawal treatment and compare the needs of clients with comorbid mental health problems and those without.

Methods

Participants completed questionnaires at intake and discharge. Questionnaires assessed reasons for entering withdrawal treatment, goals, comorbidity, and perceived help received.

Results

The sample comprised 1746 participants (69.4% male). Participants endorsed diverse reasons for entering withdrawal treatment. The most and least endorsed reasons were “stop using” (97.9%) and “legal reasons” (43.1%). Comorbidity groups varied significantly in their endorsement of reasons for mental health, physical health, harm reduction, financial, and legal.

Conclusion

AOD users enter withdrawal treatment with a variety of reasons and goals including harm reduction. Variations in rates of endorsement highlight the importance of identifying individual needs dependent on mental health comorbidity.

Introduction

Withdrawal treatment is the initial treatment experience for many individuals with alcohol and other drug (AOD) problems which are chronic relapsing conditions (Lee et al., Citation2014, Citation2020; Livingston et al., Citation2022). Positive outcomes from withdrawal treatment predict engagement in further treatment and re-engagement with services following relapse (Lee et al., Citation2014, Citation2020; Livingston et al., Citation2022). Withdrawal treatment without further treatment generally leads to relapse and readmission (Hutchison et al., Citation2019; Livingston et al., Citation2022). Past research has shown that withdrawal treatment services tend to focus on outcomes defined by service providers rather than considering the perspectives of service users and their recovery goals (Dodge et al., Citation2010; Taylor et al., Citation2021). This may result in a malalignment of the goals between service providers and recipients, discouraging AOD clients from seeking further treatment following relapse.

Research has suggested that while the primary goal of withdrawal treatment services is to assist clients in achieving abstinence, there are other important recovery domains for AOD users (Maffina et al., Citation2013; McCallum et al., Citation2015; Thurgood et al., Citation2014; Wang et al., Citation2023). In addition to abstinence, AOD users and their family and friends have identified improved social circumstances (e.g., stable housing), health, activities, supportive relationships, self-awareness (e.g., confidence), and well-being of family and friends as desirable outcomes (Thurgood et al., Citation2014). Therefore, it is likely that AOD users enter withdrawal treatment services with a variety of reasons and goals.

By way of example, although most AOD users identify abstinence as their treatment goal, some seek treatment for the purpose of harm reduction (Kenney et al., Citation2019; McKeganey et al., Citation2004; Neale et al., Citation2011; Taylor et al., Citation2021). In a study of 966 AOD users from 33 treatment agencies, McKeganey et al. (Citation2004) found that 56.6% chose “abstinence” as their only treatment goal, whereas 7.1% identified “reduced drug use” and 7.4% selected “stabilization” as their only goal. Drinkers with less severity of dependence were more likely to choose harm reduction goals (Adamson & Sellman, Citation2001; Booth et al., Citation1984). In the treatment of drug use, specifically cannabis, those who chose abstinence-based goals were more likely to achieve abstinence outcomes, while those choosing harm reduction goals were more likely to engage in moderate use at the end of treatment (Lozano et al., Citation2006). These findings suggest that a significant minority of clients in withdrawal treatment may have harm reduction as their goal rather than abstinence.

Individuals seeking withdrawal treatment often present with comorbid substance use and mental health disorders (Vella et al., Citation2015), which may influence their reasons and goals for seeking withdrawal treatment. Those with comorbidity are expected to have higher needs in general and for mental health needs in particular. The SAMHSA model of recovery proposes a holistic view of recovery incorporating biological, psychological, and social functioning (SAMHSA, Citation2012), which is consistent with other conceptual frameworks of recovery (Dodge et al., Citation2010; Thurgood et al., Citation2014), and other holistic measures to evaluate outcomes, such as Australian Treatment Outcomes Profile (Deacon et al., Citation2020). These recovery definitions are based on the recognition that there are a broad range of needs and goals that are designed to prompt recovery from both substance use disorders and other mental health problems.

Withdrawal treatment outcomes that better meet the needs of AOD users are also likely to motivate subsequent treatment seeking for this chronic relapsing condition. AOD clients who had their needs met were more likely to access follow-up treatment (McCallum et al., Citation2015). Similarly, withdrawal treatment that better aligns with individual needs produces greater treatment completion (Mutter & Ali, Citation2019), which has been associated with better future outcomes (Acevedo et al., Citation2020). One study reported that lower readmissions and greater engagement in follow-up services occurred by including an intake interview which asked for reasons for current readmission and identified discharge plans (Hutchison et al., Citation2019). These studies highlight the need to explore and understand various reasons and treatment goals that a person may have when seeking withdrawal treatment. However, there is a lack of prior research that describes the variety of reasons that clients endorse for entering withdrawal treatment services.

Past research has examined harm reduction goals in non-withdrawal treatment settings (McKeganey et al., Citation2004; Neale et al., Citation2011), but no studies were found in withdrawal treatment settings that explored the initial goals, harm reduction, and a range of other reasons for entering treatment. To address this research gap, the current study aimed to explore treatment goals including harm reduction and various reasons participants endorse for entering withdrawal treatment at both intake and discharge. This study also examined participants’ perceptions of the extent to which they received help for the issues identified at intake. Given that individuals with comorbid mental health problems may have different needs, this study further examined differences in reasons endorsed by those with and without comorbid mental health problems when entering withdrawal treatment services.

The study aimed to answer the following research questions: (1) Do clients enter withdrawal treatment with goals other than abstinence? What proportion of clients endorse non-abstinence goals? (2) Do clients’ goals change from intake to discharge from withdrawal treatment? (3) To what extent do clients endorse a variety of reasons for entering withdrawal treatment? (4) At discharge, what proportion of clients felt that they had received help for the reasons that they had when entering withdrawal treatment? (5) Are there any significant differences in the levels of endorsement of the reasons for entering withdrawal treatment between those with comorbid mental health problems vs. those without?

Methods

Participants

The initial sample comprised of 2091 consecutive participants attending one of three Australian Salvation Army residential withdrawal treatment services in Sydney, New South Wales (10 beds), Brisbane, Queensland (12 beds), or the Gold Coast, Queensland (11 beds). These withdrawal treatment services provided non-medical or low-medical withdrawal treatments and did not admit individuals with severe medical or psychiatric complications. The standard program duration for withdrawal treatment was 7 days but it varied depending on the level of care required. Data were collected from April 2017 to November 2019. To adhere to ethical requirements, participants were deemed ineligible and asked not to participate if, in the judgment of treatment staff, they were experiencing very high levels of distress, aggression, or were considered medically unstable. The study protocols were reviewed and approved by the University of Wollongong Human Research Ethics Committee (HE16-922).

Measures

Demographics

Demographic and other service use information was extracted from The Salvation Army Management Information System (SAMIS). These data were entered by service staff and included gender, age, and primary substances of use (coded as “alcohol” or “other drugs”).

Development of survey questionnaire

Although prior measures have been developed that assess reasons for entering drug and alcohol treatment (e.g., Dugosh et al., Citation2014; Marlowe et al., Citation2001; Merrick et al., Citation2012; Meyers et al., Citation2014), they have not been developed or used in withdrawal treatment contexts. Often prior measures have targeted a specific reason domain only (e.g., influence of others; Meyers et al., Citation2014), or are too lengthy (e.g., Dugosh et al., Citation2014) for the very short duration of most inpatient withdrawal treatment programs. Thus, there was a need to develop a briefer study-specific measure that also covered multiple domains (see Supplementary Appendix A1: Intake Questionnaire and Supplementary Appendix A2; Discharge Questionnaire). The items in our measure cover the six domains identified in the factor analysis of Dugosh et al. (Citation2014) 121 item measure (i.e., social, financial, legal, medical, psychiatric, and family).

The development of the questionnaire involved interviews with field experts and identification of goal types from existing scales. Four Salvation Army program members, comprising one service manager and three direct service treatment staff, were interviewed individually by the researchers and asked to identify the reasons and motivations their previous clients had for entering their services. The staff were asked separately to identify these reasons based on their perceptions and past experiences working with the clients in general (i.e., they were not asked about the goals and/or reasons for specific clients).

Common reasons identified included: “harm reduction,” “becoming unwell, both physically and psychologically,” and “issues with or isolation from family, spouse or children,” etc. The results of the interviews suggested that most people enter withdrawal treatment for a range of reasons.

Notes were taken from the interviews with staff, then researchers organized these responses into the categories that would be included in the questionnaire. Reference to and decisions about the labels were also informed by the review of other measures and prior research (e.g., Dugosh et al., Citation2014). A literature search was also conducted to identify items from past papers and existing scales that address (1) the reasons for people to stop using drug and alcohol, (2) the reasons that people seek treatment initially and (3) the reasons people stay in treatment for AOD issues (e.g., Gilburt et al., Citation2015; Johnson & Cohen, Citation2004; Weisner & Matzger, Citation2002). Several scales were reviewed to inform the development of the questionnaire. Example scales were the Treatment Outcome Measure (Lawrinson et al., Citation2005), the Stages of Change Readiness and Treatment Eagerness Scale (Miller & Tonigan, Citation1996), and the Drinker Inventory of Consequences (Forcehimes et al., Citation2007).

Intake questionnaire

At intake, participants were asked to identify their withdrawal treatment goal with three options: abstinence, reduced/controlled use, and no intention of reducing use. Participants were then given a list of 14 questions which consisted of 13 specific reasons for entering withdrawal treatment (e.g., accommodation, legal, mental health, physical health, etc.), and one additional option for specifying “other” reasons. They were asked to rate whether these reasons applied to them on a Likert scale from 1 (“Strongly Disagree”) to 4 (“Strongly Agree”).

Discharge questionnaire

At discharge, participants were again asked to indicate their goal “immediately after this withdrawal treatment” with three options: abstinence, reduced/controlled use, and no intention of reducing use. They were then asked to evaluate the extent to which they felt they had received help during withdrawal treatment for each of the 14 reasons using the same questionnaire structure, responding on a Likert scale from 1 (“Not at all”) to 4 (“Very much”), with an additional option (“Does not apply to me”). Comorbid and non-comorbid groups were formed based on participants’ response to the following item: “Right now, do you think you have a mental health problem?” Participants responded using a 4-point Likert scale that ranged from 1 (“No Problem”), 2 (“Small Problem”), 3 (“Large Problem”) to 4 (“Very Large Problem”).

Procedure

The Salvation Army staff invited all eligible clients to participate in the study. Participants were approached and given the intake questionnaire after service staff determined they were medically stable (typically on the third day). Participants were then given the discharge questionnaire by staff before their discharge (typically the day before). Participants completed questionnaires privately in a confidential setting. All participants received written information describing the study and highlighting the voluntary nature of participation. Written consent was obtained. The staff were responsible for providing the questionnaire to participants who then completed the survey. The completed surveys were gathered by staff.

Analysis plan

Before conducting the main analyses, we explored whether there were differences in all main study variables between participants presenting with alcohol as their primary substance of concern, compared to those with other drugs.

Goals at intake and discharge were analyzed using frequencies. Frequencies were calculated to determine the percentage of participants endorsing each goal at both intake and discharge. This analysis comprised the 1494 participants who indicated a treatment goal at both intake and discharge.

A Pearson non-parametric chi-square test was performed to examine whether there was a significant difference between participants with comorbidity and those without in relation to their endorsement of reasons for entering inpatient withdrawal treatment. For the purposes of the current study, participants who responded 1 and 2 (i.e., “No Problem” and “Small Problem”) were categorized into the “non-comorbidity” group. Those responding 3 and 4 (i.e., “Large Problem” and “Very Large Problem”) were allocated to the “comorbidity” group which comprised 362 (55%) participants. Many people enter withdrawal treatment experiencing some form of psychological distress which may or may not constitute a more persistent mental health problem (e.g., Engel et al., Citation2016; Ostergaard et al., Citation2019). We made the decision to include responses of 3 and 4 (and exclude “small problem”) to constitute the comorbidity group because we wanted to compare those likely to have more severe mental health problems. As noted, all reasons were rated using a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (“Strongly Disagree”), 2 (“Disagree”), 3 (“Agree”), to 4 (“Strongly Agree”). Responses of either 1 or 2 were categorized as “Disagree” whereas responses of either 3 or 4 were categorized as “Agree.”

A 2 (comorbid/non-comorbid) by 2 (Agree/Disagree to reasons) Pearson non-parametric chi-square test was performed to examine whether there was a significant difference in the proportion of participants in the groups endorsing each reason for entering inpatient withdrawal treatment. To control for Type-I-error due to multiple comparisons, a Bonferroni corrected p-value of p = .004 was used to determine significance.

Results

Demographics

Of 2091 participants, 345 (16%) were readmissions within the study period, so second admission data were excluded. The final sample comprised of 1746 participants (69.4% male) aged 22 to 83 years (M = 42.96, SD = 10.88). The majority (65.6%) were seeking help for drugs other than alcohol use.

Unfortunately, more detailed information about the frequency of different types of other drugs was not available in this data download from the service information system. However, prior research in two of the three Salvation Army withdrawal treatment services used in the current study indicated that the frequencies of different substances being used in a sample of n = 218 participants were as follows: alcohol (50.9%), amphetamine-type substances (16.5%), cannabis (15.6%), heroin (8.3%), and opioid-type substances (8.7%; Vella et al., Citation2015).

Comparisons between “alcohol” and “other drug” groups

There were no statistically significant differences in reasons for entering withdrawal treatment, proportions endorsing different goals at intake or at discharge, and perceived helpfulness of withdrawal treatment. As such, all following analyses report results for the total sample rather than for “alcohol” and “other drugs” groups separately.

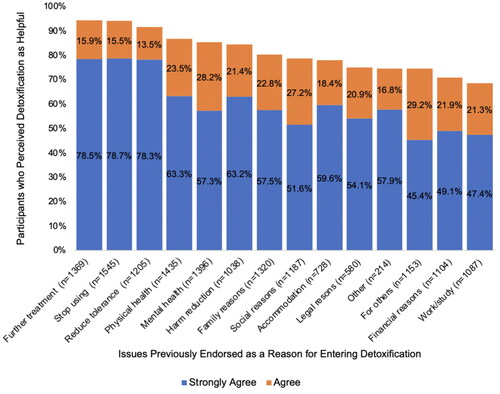

Reasons for entering withdrawal treatment

At intake, 1688 (96.68%) participants indicated a withdrawal treatment goal. Of these, 94.1% endorsed abstinence as their goal at intake, 5.5% reported wanting to reduce their use, and the remaining 0.4% reported wanting to have a short-term break from use with no intention to reduce or stop use in the long term. displays the percentages of those who endorsed “Agree” or “Strongly Agree” for the reasons for entering withdrawal treatment. With the exception of accommodation and legal reasons, all other reasons (85.7%) were endorsed by at least 70% of participants. The most highly reported reasons for entering were “stop using” (97.9%, M = 3.82, SD = 0.47) and “physical health” (92%, M = 3.54, SD = 0.46), and the least reported reasons were “accommodation” (50.1%, M = 2.52, SD = 1.17) and “legal reasons” (43.1%, M = 2.30, SD = 1.21).

Figure 1. Reasons for entering withdrawal treatment. Note. The figure shows the percentage of participants who reported “strongly agree” and “agree” in response to each reason for entering withdrawal treatment.

Overall, almost 60% of participants endorsed the “other reason” item, specifying miscellaneous reasons for entering withdrawal treatment including, but not limited to God/spirituality, desire for happiness, wanting a new life/their life back, and parental and custody issues.

Of the 1482 participants who indicated the degree to which they entered the withdrawal treatment service for themselves or others, two-thirds endorsed entering withdrawal treatment either mostly (31.8%) or entirely for themselves (34.9%).

Goals at intake and discharge

At intake, 94.9% (n = 1418) endorsed abstinence as their treatment goal, whilst 4.9% (n = 73) and 0.2% (n = 3) indicated reduced use and no intention of reducing use, respectively. At discharge, 94.7% (n = 1415) indicated abstinence, 4.8% (n = 72) indicated reduced use, and 0.5% (n = 7) indicated no intention of reducing use as their goals.

In some cases, treatment goals changed from intake to discharge. Of the 1418 participants who indicated abstinence as their goal at intake, 2.1% changed their goal to reduced use and 0.4% to no intention of reducing use.

Seventy-three participants indicated reduced use as their intake goal. Of these participants, 43.8% changed to abstinence and 1.4% changed to no intention of reducing use. These results revealed that many more participants changed their goals to abstinence than those who changed their goals to non-abstinence.

In addition, three participants endorsed no intention of reducing use at intake. Of these, two changed to reduced use at discharge. The low sample sizes for some cells did not allow a formal statistical test of differences in proportions between the “alcohol” and “other drug” groups.

Comparison of reasons for entering inpatient withdrawal treatment between participants with comorbid mental health problems and non-comorbidity

As shown in , significant differences between the comorbid vs. non-comorbid groups were found in the endorsement of reasons for harm reduction (p = .002), financial reasons (p = .004), legal reasons (p < .001), physical health (p = .004), and mental health (p < .001). The comorbid group rated all reasons except for legal reasons significantly higher than their non-comorbid counterparts.

Table 1. Comorbidity vs. Non-comorbidity Participants’ Endorsement of Reasons for Entering Inpatient Withdrawal Treatment

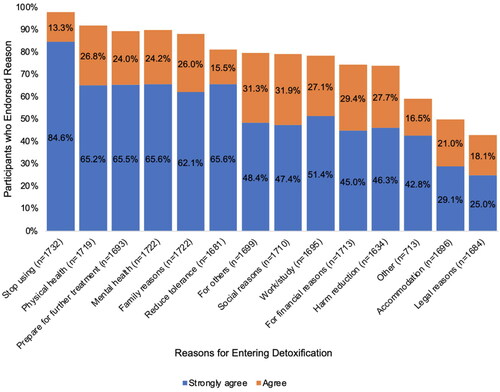

Perceived helpfulness of withdrawal treatment

illustrates the participants’ perception of the helpfulness of the withdrawal treatment program in addressing the specific reasons that they endorsed for seeking treatment. It provides a visual comparison of helpfulness frequencies for each reason endorsed when entering withdrawal treatment. Only individuals who endorsed each domain as a reason for entry were included in . The withdrawal treatment program helped 94.4% (M = 3.7, SD = 0.66) prepare for future treatment and 94.2% (M = 3.69, SD = 0.70) to stop using. Work/job/study (68.7%, M = 2.84, SD = 1.37), financial reasons (71.0%, M = 2.23, SD = 1.09), and “other” (74.6%, M = 2.88, SD = 1.55) had the lowest ratings of help received.

Discussion

Main findings

Participants endorsed diverse reasons for entering withdrawal treatment. Twelve of the 14 specific reasons including “other reason” were endorsed by more than 70% of participants. Traditionally, inpatient withdrawal treatment has largely focused on abstinence-oriented outcomes (Baxley et al., Citation2019). However, our results indicate that although abstinence is a prevalent goal (94.1%), 5.9% of participants did not endorse abstinence as a goal for entering withdrawal treatment. Instead, most of these participants sought to reduce their use, indicating that a harm reduction approach to treatment may be more appropriate for these individuals. Harm reduction approaches in opioid use treatment include prioritizing patient perspectives and allowing for the choice of selection and dose of medication using a shared decision-making framework (Taylor et al., Citation2021). Some harm reduction approaches incorporate counseling regarding overdose prevention strategies, such as advocating for drug intake through non-intravenous routes (Taylor et al., Citation2021).

Our findings emphasize the importance of evaluating and addressing the unique needs of AOD users when they enter withdrawal treatment. Evaluating individual needs during intake informs the provision of personalized withdrawal treatment and discharge planning, leading to greater treatment completion (Mutter & Ali, Citation2019) and improved future outcomes (Acevedo et al., Citation2020). By aligning follow-up referrals with the client’s individual reasons for entry and preferred treatment goals, tailored discharge planning can clarify which services are necessary and increase the likelihood of treatment retention. For example, clients in need of accommodation might benefit from referral to a residential rehabilitation service instead of an outpatient service, promoting long-term accommodation planning and enhancing follow-up treatment retention.

Our results indicate that initial treatment goals for substance use are malleable, even during a brief withdrawal treatment program of seven days. In our sample, 2.5% of participants endorsing abstinence at intake changed their goal to non-abstinence at discharge and over 40% of those endorsing reduced use at intake changed to abstinence at discharge. This change is likely to have been influenced by the abstinence orientation of the treatment services. However, it is also possible that, after completing withdrawal treatment, the goal of abstinence is perceived as more achievable. Future research should explore the influences and processes that lead to this change.

A small percentage of participants changed from abstinence at intake to non-abstinence goals at discharge, while other participants also maintained their non-abstinence goal from intake, meaning that 5.3% did not have abstinence as their goal at discharge. Given that prior research has emphasized that consideration of individualized treatment goals produces better outcomes and program completion (Mutter & Ali, Citation2019), it may not be helpful to refer those with non-abstinence goals to abstinence-oriented follow-up services. This aligns with previous research showing that goals for entering treatment vary, particularly among individuals using multiple substances (Kenney et al., Citation2019). For example, when drinkers can select a treatment goal aligned with their needs, positive outcomes can be achieved for both abstinence and harm reduction goals (Dunn & Strain, Citation2013). While assessing clients’ individual goals for future substance use may not change the need for abstinence during inpatient withdrawal treatment, it may mean that more tailored psychoeducational responses that highlight the risks and benefits of harm reduction vs. abstinence goals can improve the effectiveness of long-term treatment outcomes.

The current study is novel in its examination of perceived levels of help received in different domains. The majority of respondents (94%) reported receiving help in stopping use and preparing for further treatment. Work/study and financial reasons had the lowest perceived help received among those who had endorsed those reasons at intake, although nearly 70% of respondents still reported some level of help received in these areas.

At intake, participants with comorbid mental health problems indicated higher endorsement of mental health reasons and higher needs in general compared to non-comorbid participants. Previous research has shown a correlation between AOD problems and mental health conditions, where improvement or deterioration in one often corresponds with the same in the other (Vella et al., Citation2015). The strong association between AOD problems and mental health issues has clinical implications, highlighting the importance of providing withdrawal treatment and mental health treatment concurrently, and/or providing mental health treatment referrals following withdrawal treatment to prevent relapse in both areas and reduce readmissions.

Significant associations were found between comorbidity status and rates of endorsement of harm reduction and physical health. Harm reduction approaches not only address substance use but also prioritize the overall physical health and well-being of AOD users. Prior research has also found that patients with mental health comorbidity were also at the highest risk for five of the eight medical disorders measured (Dickey et al., Citation2002). Such findings highlight the need to address the range of physical health issues during withdrawal treatment and to provide relevant referrals at discharge.

Significant associations between comorbidity status and financial reasons indicate that comorbid participants showed a higher need for addressing financial issues. Prior research has revealed a strong association between mental illness, substance use, and unemployment in the U.S. (Song & Luan, Citation2022). In addition to increased treatment costs for mental health problems, experiencing comorbidity greatly reduced AOD users’ employability (Matthews et al., Citation2013). Therefore, comorbid participants may benefit from receiving a referral for employment support upon discharge from withdrawal treatment.

Our results suggest that those with comorbid mental health problems had lower legal needs. Prior research shows that among all offenses related to AOD use, alcohol is the most frequent cause of police detainment compared with all other drugs combined (Payne & Gaffney, Citation2012). In our sample, the proportion of non-comorbid participants with alcohol use as their main presenting issue was slightly greater (32.3%) than that of the comorbid group (27.6%). Whether these factors contribute to this finding needs to be clarified by future research.

Strengths and limitations

The large sample from multiple program locations increases the generalizability of the findings. Moreover, the present study is novel in its examination of a variety of goals and reasons endorsed at intake and the participants’ perception of the help received during withdrawal treatment in relation to the reasons initially endorsed. Although the current research has expanded the scope of research within Australia, it can be further expanded to increase generalizability internationally. The risk of selection bias within the sample may limit the generalizability of the results. Additionally, the exclusion of complex medical presentations and voluntary participation limit the variability in participant characteristics.

As a pilot study in the withdrawal treatment setting, this study used relatively brief measures of goals, reasons, and comorbidity. The intake assessment of reasons and goals is brief representing relatively global domains. The trichotomous survey items of “abstinence,” “reduced use,” and “no intention of reducing use” used to identify participants’ main goal of withdrawal treatment may not be an exhaustive assessment of goals and can be challenging to apply to polysubstance users. For example, polysubstance users may desire abstinence from one substance but a short break from another. Future research should examine how specific types of substances used relate to goals and reasons, and consider goals more widely, potentially through qualitative measures. More specific goal assessment, such as Goal Attainment Scaling (Kiresuk & Sherman, Citation1968; Peckham, Citation1977) would provide a more comprehensive assessment that could then be related to other outcomes, such as treatment satisfaction or engagement in follow-up treatment. From a practice perspective, identifying reasons is the first step. Treatment providers need to work with individuals to integrate entry reasons in goal planning and pursuit.

Some participants in this study altered their goal endorsement during the course of withdrawal treatment. Despite identifying abstinence as their goal at intake, some patients changed to reduced use or no intention of reducing use at discharge, but we did not investigate the reasons for this change. Future research could interview the participants to understand the underlying factors contributing to the change from abstinence to non-abstinence goals, which may shed light on the quality of services in the withdrawal treatment programs.

Comorbidity was assessed using a single item and AOD users with mental health problems are self-defined. Future research should use a more comprehensive measure, such as conducting a structured diagnostic interview to determine comorbidity.

Lastly, it remains unclear whether addressing AOD users’ needs in the short term contributes to longer-term outcomes. For example, if someone identifies accommodation difficulties as a reason for entering withdrawal treatment and reports receiving help in this area, it is unclear whether this outcome is a result of being provided with accommodation through the residential withdrawal treatment program or having received support to access accommodation after discharge. If individuals are unable to secure accommodation following withdrawal treatment, they may be more likely to repeatedly cycle through residential services, including inpatient withdrawal treatment, to address their ongoing accommodation needs.

Future directions

Readmission is highly prevalent in AOD populations (Satre et al., Citation2012), with the current sample possessing a 16% readmission rate. Therefore, future research should investigate the interplay between the goals and reasons for entering and returning to withdrawal treatment. For example, we showed that just over 50% of participants entered withdrawal treatment for accommodation help. Future research could further explore the readmissions of this group and investigate how accommodation needs may influence recovery, including readmission to withdrawal treatment. Additionally, it may be useful to identify patterns and distinct profiles of reasons endorsed by participants entering withdrawal treatment using Latent Class Analysis, which informs the tailored treatment for groups with distinct profiles of needs. As noted, clarifying what contributes to differences in some reasons for entering withdrawal treatment for groups with comorbidity is also needed (e.g., legal reasons, harm reduction, etc.). Finally, qualitative measures, such as longer-term follow-up and interviews can also be conducted to investigate the reasons for the change of goals observed among participants.

Conclusion

AOD users entered withdrawal treatment for a diverse range of reasons and goals including harm reduction, which aligns with the holistic recovery model (Deacon et al., Citation2020; Dodge et al., Citation2010; SAMHSA, Citation2012; Thurgood et al., Citation2014). Our findings underscore the importance of assessing and addressing the diverse individualized needs of AOD users entering withdrawal treatment. Given the high comorbidity rates in withdrawal treatment and the finding that individuals with comorbidity have a higher need in general and higher mental health needs in particular, it is crucial to identify individuals with comorbidity at the intake of withdrawal treatment and provide concurrent withdrawal treatment and mental health treatment, and mental health treatment referral at discharge. The findings from this study have important clinical implications as they highlight the importance of aligning AOD users’ individual needs with the provision of withdrawal treatment and referral to follow-up services. This has the potential to facilitate withdrawal treatment completion, maintenance of clinical gains, and relapse prevention.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (62.4 KB)Acknowledgments

We wish to thank all of the participants who volunteered for this research. In addition, thanks to the staff at The Salvation Army Withdrawal Treatment Services for their participation and support in administering the questionnaires.

Disclosure statement

Prof. Frank Deane and Prof. Peter Kelly have previously held research consultancy grants with The Salvation Army.

Data availability statement

Data are confidential since they are derived from clinical services. However, they may be made available upon reasonable request and following institutional ethical review and approval.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Acevedo, A., Harvey, N., Kamanu, M., Tendulkar, S., & Fleary, S. (2020). Barriers, facilitators, and disparities in retention for adolescents in treatment for substance use disorders: A qualitative study with treatment providers. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy, 15(1), 42. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13011-020-00284-4

- Adamson, S. J., & Sellman, J. D. (2001). Drinking goal selection and treatment outcome in out-patients with mild-moderate alcohol dependence. Drug and Alcohol Review, 20(4), 351–359. https://doi.org/10.1080/09595230120092670

- Baxley, C., Weinstock, J., Lustman, P. J., & Garner, A. A. (2019). The influence of anxiety sensitivity on opioid use disorder treatment outcomes. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 27(1), 64–77. https://doi.org/10.1037/pha0000215

- Booth, P. G., Dale, B., & Ansari, J. (1984). Problem drinkers’ goal choice and treatment outcome: A preliminary study. Addictive Behaviors, 9(4), 357–364. https://doi.org/10.1016/0306-4603(84)90035-2

- Deacon, R. M., Mammen, K., Holmes, J., Dunlop, A., Bruno, R., Mills, L., Graham, R., & Lintzeris, N. (2020). Assessing the validity of the Australian Treatment Outcomes Profile for telephone administration in drug health treatment populations. Drug and Alcohol Review, 39(5), 441–446. https://doi.org/10.1111/dar.13088

- Dickey, B., Normand, S. T., Weiss, R. D., Drake, R. E., & Azeni, H. (2002). Medical morbidity, mental illness, and substance use disorders. Psychiatric Services, 53(7), 861–867. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.53.7.861

- Dodge, K., Krantz, B., & Kenny, P. J. (2010). How can we begin to measure recovery? Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy, 5(1), 31. https://doi.org/10.1186/1747-597X-5-31

- Dugosh, K. L., Festinger, D. S., Lynch, K. G., & Marlowe, D. B. (2014). The Survey of Treatment Entry Pressures (STEP): Identifying client’s reasons for entering substance abuse treatment. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 70(10), 956–966. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22093

- Dunn, K. E., & Strain, E. C. (2013). Pretreatment alcohol drinking goals are associated with treatment outcomes. Alcoholism: Clinical & Experimental Research, 37(10), 1745–1752. https://doi.org/10.1111/acer.12137

- Engel, K., Schaefer, M., Stickel, A., Binder, H., Heinz, A., & Richter, C. (2016). The role of psychological distress in relapse prevention of alcohol addiction. Can high scores on the SCL-90-R predict alcohol relapse? Alcohol and Alcoholism, 51(1), 27–31. https://doi.org/10.1093/alcalc/agv062

- Forcehimes, A. A., Tonigan, J. S., Miller, W. R., Kenna, G. A., & Baer, J. S. (2007). Psychometrics of the Drinker Inventory of Consequences (DrInC). Addictive Behaviors, 32(8), 1699–1704. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.11.009

- Gilburt, H., Drummond, C., & Sinclair, J. (2015). Navigating the alcohol treatment pathway: A qualitative study from the service users’ perspective. Alcohol and Alcoholism, 50(4), 444–450. https://doi.org/10.1093/alcalc/agv027

- Hutchison, S. L., Flanagan, J. V., Karpov, I., Elliott, L., Holsinger, B., Edwards, J., & Loveland, D. (2019). Care management intervention to decrease psychiatric and substance use disorder readmissions in Medicaid-enrolled adults. The Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research, 46(3), 533–543. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11414-018-9614-y

- Johnson, T. J., & Cohen, E. A. (2004). College students’ reasons for not drinking and not playing drinking games. Substance Use & Misuse, 39(7), 1137–1160. https://doi.org/10.1081/JA-120038033

- Kenney, S. R., Anderson, B. J., Bailey, G. L., & Stein, M. D. (2019). Expectations about alcohol, cocaine, and benzodiazepine abstinence following inpatient heroin withdrawal management. The American Journal on Addictions, 28(1), 36–42. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajad.12834

- Kiresuk, T. J., & Sherman, R. E. (1968). Goal attainment scaling: A general method for evaluating comprehensive community mental health programs. Community Mental Health Journal, 4(6), 443–453. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01530764

- Lawrinson, P., Copeland, J., & Indig, D. (2005). Development and validation of a brief instrument for routine outcome monitoring in opioid maintenance pharmacotherapy services: The brief treatment outcome measure (BTOM). Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 80(1), 125–133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.04.001

- Lee, M. T., Horgan, C. M., Garnick, D. W., Acevedo, A., Panas, L., Ritter, G. A., Dunigan, R., Babakhanlou-Chase, H., Bidorini, A., Campbell, K., Haberlin, K., Huber, A., Lambert-Wacey, D., Leeper, T., & Reynolds, M. (2014). A performance measure for continuity of care after detoxification: Relationship with outcomes. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 47(2), 130–139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2014.04.002

- Lee, M. T., Torres, M., Brolin, M., Merrick, E. L., Ritter, G. A., Panas, L., Horgan, C. M., Lane, N., Hopwood, J. C., De Marco, N., & Gewirtz, A. (2020). Impact of recovery support navigators on continuity of care after detoxification. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 112, 10–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2020.01.019

- Livingston, N., Ameral, V., Hocking, E., Leviyah, X., & Timko, C. (2022). Interventions to improve post-detoxification treatment engagement and alcohol recovery: Systematic review of intervention types and effectiveness. Alcohol and Alcoholism, 57(1), 136–150. https://doi.org/10.1093/alcalc/agab021

- Lozano, B. E., Stephens, R. S., & Roffman, R. A. (2006). Abstinence and moderate use goals in the treatment of marijuana dependence. Addiction, 101(11), 1589–1597. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01609.x

- Maffina, L., Deane, F. P., Lyons, G. C. B., Crowe, T. P., & Kelly, P. J. (2013). Relative importance of abstinence in clients’ and clinicians’ perspectives of recovery from drug and alcohol abuse. Substance Use & Misuse, 48(9), 683–690. https://doi.org/10.3109/10826084.2013.782045

- Marlowe, D. B., Glass, D. J., Merikle, E. P., Festinger, D. S., DeMatteo, D. S., Marczyk, G. R., & Platt, J. J. (2001). Efficacy of coercion in substance abuse treatment. In F. M. Tims, C. G. Leukefeld, & J. J. Platt (Eds.), Relapse and recovery in addictions (pp. 208–227). Yale University Press.

- Matthews, L. R., Harris, L. M., Jaworski, A., Alam, A., & Bozdag, G. (2013). Function in job seekers with mental illness and drug and alcohol problems who access community-based disability employment services. Disability and Rehabilitation, 35(6), 460–467. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2012.699583

- McCallum, S. L., Mikocka-Walus, A., Turnbull, D., & Andrews, J. M. (2015). Continuity of care in dual diagnosis treatment: Definitions, applications, and implications. Journal of Dual Diagnosis, 11(3–4), 217–232. https://doi.org/10.1080/15504263.2015.1104930

- McKeganey, N., Morris, Z., Neale, J., & Robertson, M. (2004). What are drug users looking for when they contact drug services: Abstinence or harm reduction? Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy, 11(5), 423–435. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687630410001723229

- Merrick, E. L., Reif, S., Hiatt, D., Hodgkin, D., Horgan, C. M., & Ritter, G. (2012). Substance abuse treatment client experience in an employed population: Results of a client survey. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy, 7(1), 4. https://doi.org/10.1186/1747-597X-7-4

- Meyers, R. J., Roozen, H. G., Smith, J. E., & Evans, B. E. (2014). Reasons for entering treatment reported by initially treatment-resistant patients with substance use disorders. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 43(4), 299–309. https://doi.org/10.1080/16506073.2014.938358

- Miller, W. R., & Tonigan, J. S. (1996). Assessing drinkers’ motivation for change: The Stages of Change Readiness and Treatment Eagerness Scale (SOCRATES). Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 10(2), 81–89. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-164X.10.2.81

- Mutter, R., & Ali, M. M. (2019). Factors associated with completion of alcohol detoxification in residential settings. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 98, 53–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2018.12.009

- Neale, J., Nettleton, S., & Pickering, L. (2011). What is the role of harm reduction when drug users say they want abstinence? The International Journal on Drug Policy, 22(3), 189–193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2010.09.007

- Ostergaard, M., Seitz, R., Jatzkowski, L., Speidel, S., Höcker, W., & Odenwald, M. (2019). Changes of self-reported PTSD and depression symptoms during alcohol detoxification treatment. Journal of Dual Diagnosis, 15(3), 123–129. https://doi.org/10.1080/15504263.2019.1620398

- Payne, J., Gaffney, A. (2012). How much crime is drug or alcohol related? Self-reported attributions of police detainees. Trends & Issues in Crime and Criminal Justice no. 439. Canberra: Australian Institute of Criminology. Retrieved from https://www.aic.gov.au/publications/tandi/tandi439

- Peckham, R. H. (1977). Uses of individualized client goals in the evaluation of drug and alcohol programs. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 4(4), 555–570. https://doi.org/10.3109/00952997709007011

- Satre, D. D., Chi, F. W., Mertens, J. R., & Weisner, C. M. (2012). Effects of age and life transitions on alcohol and drug treatment outcome over nine years. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 73(3), 459–468. https://doi.org/10.15288/jsad.2012.73.459

- Song, I., & Luan, H. (2022). The spatially and temporally varying association between mental illness and substance use mortality and unemployment: A Bayesian analysis in the contiguous United States, 2001–2014. Applied Geography, 140, 102664. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeog.2022.102664

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (2012). SAMHSA’s working definition of recovery: 10 guiding principles of recovery. Retrieved from https://store.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/d7/priv/pep12-recdef.pdf

- Taylor, J. L., Johnson, S., Cruz, R., Gray, J. R., Schiff, D., & Bagley, S. M. (2021). Integrating harm reduction into outpatient opioid use disorder treatment settings. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 36(12), 3810–3819. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-021-06904-4

- Thurgood, S., Crosby, H., Raistrick, D., & Tober, G. (2014). Service user, family and friends’ views on the meaning of a ‘good outcome’ of treatment for an addiction problem. Drugs: Education, Prevention & Policy, 21(4), 324–332. https://doi.org/10.3109/09687637.2014.899987

- Vella, V. E., Deane, F. P., & Kelly, P. J. (2015). Comorbidity in detoxification: Symptom interaction and treatment intentions. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 49, 35–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2014.07.016

- Wang, J., Deane, F. P., Kelly, P. J., & Robinson, L. (2023). A narrative review of outcome measures used in drug and alcohol inpatient withdrawal treatment research. Drug and Alcohol Review, 42(2), 415–426. https://doi.org/10.1111/dar.13591

- Weisner, C., & Matzger, H. (2002). A prospective study of the factors influencing entry to alcohol and drug treatment. The Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research, 29(2), 126–137. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02287699