Abstract

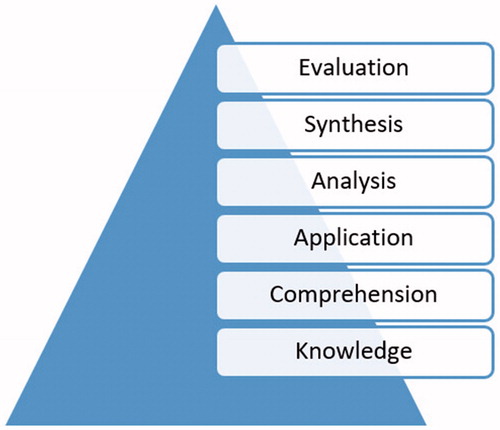

This article shows how a gallery walk exercise can be used to encourage broad participation and higher-level thinking among undergraduate students of political science. Asked to visualize the future of different political ideologies, the students work together in groups to create posters that they then present for each other during a vernissage-like event that includes a Q&A session. This seminar format enables an iterative, adaptive, and reflective approach to learning that stimulates higher-level skills such as synthesis and evaluation. As such, the gallery walk exercise can be seen as a useful complement to more traditional didactic learning activities aimed at the lower levels of Bloom’s taxonomy (e.g., knowledge and comprehension). Based on written course evaluations, the students seem to appreciate not only the novelty of the gallery walk seminar format but also how it prompted them to see the different ideologies in a new light and that it significantly deepened their understanding of the subject matter.

Introduction

While the study of political ideologies may not play a prominent role in contemporary political science (Kaufman-Osborn Citation2010), it is still common for students in Sweden but also other countries to begin their undergraduate studies in political science with an introductory course to political theory and the history of political ideologies. As a teacher of such courses for over a decade, I have been experimenting with different ways of making the subject matter come alive for the students in order to facilitate more active forms of knowledge construction (von Glasersfeld Citation1995). In this article, my aim is to show how an action-oriented seminar format or “gallery walk” exercise can deepen understanding of political ideologies, enhance critical thinking and give students an opportunity to practice transferable presentation skills.1 Unlike during a traditional literature seminar when perhaps only a few students are active and the teacher is the one primarily giving feedback, the gallery walk format ensures that all students actively contribute and give each other feedback that is both situated and interactive. Inspired by the theoretical work of Diana Laurillard (Citation2002) and her “conversational framework,” this affirms a view of learning as an inherently social activity which should be as iterative, adaptive, and reflective as possible.

Teaching political ideologies

In his widely used textbook on political ideologies, Andrew Heywood (Citation2017) defines the study of ideologies as being “concerned with analysing the content of political thought, to be interested in the ideas, doctrines and theories that have been advanced by and within the various ideological traditions” (4). As such, it is an activity somewhat at odds with an increasingly professionalized discipline aiming for empirical explanation (March Citation2009, 534). Still, many would argue that engaging with the realm of ideas and norms is essential for students of politics. Thus, many undergraduate programs in political science begin with a course covering classical political thought, normative political philosophy, and political ideologies. Even if these subjects are less prominent later in undergraduate programs, they are supposed to help students develop a historical and intellectual frame of reference for their future studies. Especially in a time of increasing political polarization and ideologically motivated cognition (Kahan Citation2013), learning to see the other side of arguments becomes a particularly important element of political science education (Baylouny Citation2009).

While political ideologies may be identified by familiar names such as “liberalism” or “socialism,” it makes little sense to think of them as self-contained sets of ideas that students can simply memorize (Wetherly Citation2017, v). Not only is “ideology” itself an essentially contested concept (Gerring Citation1997), but it is first when contextualized in relation to contemporary political debates that the blurry edges and internal contradictions of different ideologies become visible. In line with Michael Freeden (Citation2003), my point of departure is that “we produce, disseminate and consume ideologies all our lives, whether we are aware of it or not” (1), a view that also resonates with the resurgence of ideology in social psychology (Jost, Nosek, and Gosling Citation2008). As a consequence, one important role for me as a teacher is to make students reflect on the positions they take and the ideological “lens” through which they view the world. From this perspective, teaching political ideologies is as much about relating to the students’ lifeworlds as it is about providing a specific theoretical vocabulary and historical background to the study of political ideologies.

For these purposes, role-playing is one active learning technique that I have used extensively when teaching political ideologies (Oros Citation2007). However, role-playing is also an activity whose success very much depends on the creativity and self-confidence of the individual students. Some semesters, the results have been very good, while other semesters, the role-playing seminars have fallen flat as the students have been too self-conscious or nervous to fully act their different roles. In order to avoid this sense of uncertainty, both among the student group and me, I started to experiment with different alternative seminar formats.

Through a course organized by the Centre for Educational Development at Umeå University, I became acquainted with the “gallery walk” exercise (Chin, Khor, and Teh Citation2015; Francek Citation2006) and how “Magic Charts”—i.e., an erasable electrostatic poster that resembles a whiteboard—could be used to facilitate collaborative idea generation. Inspired by this experience, I designed a seminar in which students would work in groups to visualize the future of different political ideologies and then present their work in the form of a vernissage or gallery walk. After a bit of thinking, I settled on a 3-hour class format by which the first 2 hours are used by the students to prepare their posters and the last hour is used for the gallery walk which includes both a presentation and a Q&A part. In my current course schedule, the gallery walk seminar comes after a lecture-intensive week with six 2-hour sessions aimed at giving a thorough introduction to each of the political ideologies.

My reason for working with the future of the political ideologies rather than the present is that I wanted to introduce an active and dynamic factor that prompts the students to not only regurgitate what they have learned during the preceding lectures. Just as in politics more generally (Karlsson Citation2005), thinking about the future brings an element of indeterminacy that liberates the imagination and make ideological choices visible. At the same time, visualizing the future also raises questions about political feasibility constraints and the broader relationship between the different ideologies and social change. In my instructions to the students, I do not, however, define how many years into the future they should look but rather encourage the students to take the question of time horizons as a starting point for their group discussions. Similarly, I do not restrict the spatial scope of the exercise, leaving it up to the students if they want to think in global, regional, or national terms.

Visualizing the future of political ideologies

Working with about 20–25 students at a time, I typically divide them into four to five smaller groups that are each assigned one ideology. Rather than allowing the students to choose which ideology to work with themselves, I make a pedagogical point of randomly assigning the ideologies so that the students may have to work with an ideology that they still may feel uncertain about. Otherwise, in terms of the style of their presentations, it is up to the students if they want to draw a simple mind-map or create something more visually advanced. Throughout, I have tried to minimize the amount of instructions given to the students in order to not stymie their creativity or unnecessarily limit the plurality of ways in which they approach the task.

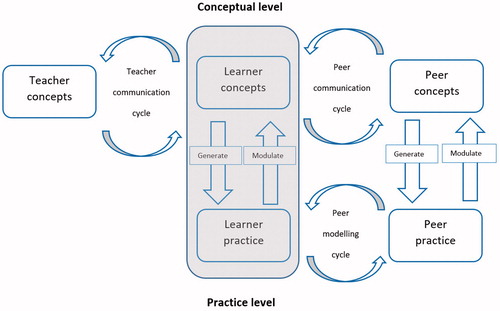

In the process of creating their posters, a lot of interaction and modulation take place between the students as they compare lecture notes, review the course literature, or search the internet for additional information—all supporting higher-order thinking skills such as analysis, evaluation, and synthesis. During this time (typically 2 hours including a break), I move between the groups, offering formative feedback and answering questions that they might have. Interpreted through Laurillard’s conversational framework, this collaborative form of learning allows each student (at the center of the figure below) to engage in cyclical communication with both peers and me as the teacher, moving between the conceptual and practice level ().

Figure 1. The conversational framework, inspired by Laurillard (Citation2013).

Once finished, the students put up their posters on the wall in the classroom and are then asked to create new intergroups in which one student represents each ideology. With the new groups in place, the actual gallery walk exercise starts and the students are given 4 minutes to present their work to their new group members followed by 4 minutes of Q&A. All groups do this simultaneously in different parts of the classroom. After eight minutes have passed, the groups rotate clockwise in the classroom ().

With four to five posters, this means that the actual gallery walk exercise takes roughly 35–40 min. During this time, I again move between the groups and listen to their respective presentations. This way of presenting the posters means that each student has to take “ownership” of the process and be ready to answer questions from the other students. This is a significant difference from a regular group poster presentation which can easily be dominated by a few assertive group members, something that seems important to avoid, not the least, from a gender or intersectional perspective (Diller Citation2018).

During the Q&A sessions, the students ask questions that open up conversations between the posters and ideologies, often emphasizing the fundamental truth that politics is not so much about offering different solutions to the same problem, as it is about offering different conceptions of what the problem is represented to be (Bacchi Citation2012). After all groups have presented, I give some final summative feedback, reflecting on the performance of the whole class but also the content of the individual posters. While it would hypothetically be possible to give the students an opportunity to once again go back and revise their posters after this final stage, that is not something that I have pursued in my seminars but something that could perhaps be useful in a different setting.

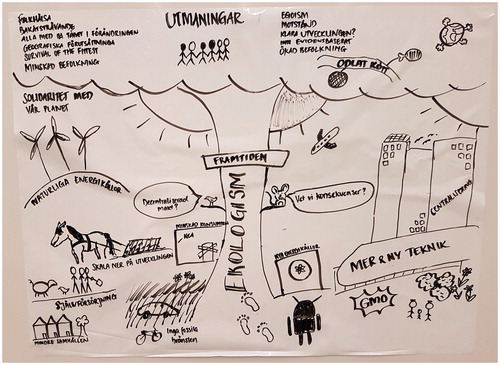

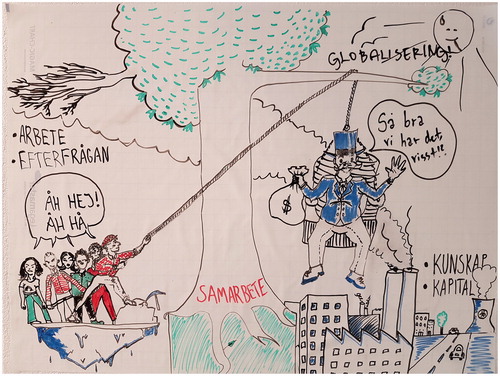

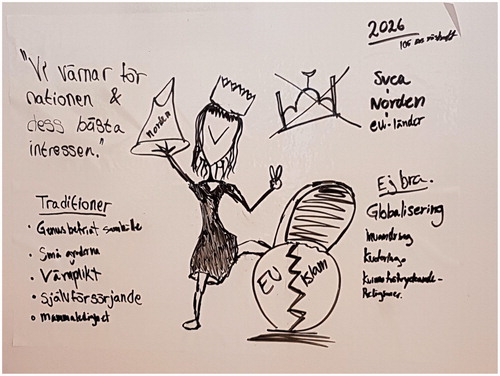

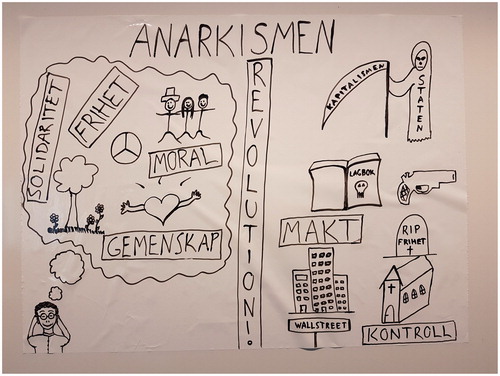

In order to give an impression, albeit in Swedish, of the kind of work created through these workshops, I have included four sample posters below (). In these four posters, it is evident that the groups have grappled with questions of political feasibility and tensions within the different ideologies; for instance, the divide between deep ecological and ecomodernist perspectives as seen in the “ecologism” poster (Symons and Karlsson Citation2018) which uses the stem of a tree to separate these two very different futures. To the left in this first picture, one can see the symbols of traditional environmentalism and its desire to harmonize with nature through small-scale agriculture, decentralization, and degrowth whereas to the right, greater separation from nature makes possible planetary-scale rewilding and urbanization. In the second, “socialism” poster, the conflicted yet mutually interdependent relationship between capital owners and workers is explored in the context of globalization and climate change. To the right in the picture, one can see a stereotypical capitalist sitting in a swing extolling how good everything is, while, to the left, the workers are pushing the swing even as the ice is melting below their feet. Globalization is also an important topic in the “conservatism” poster although the focus there is more on the social value conflicts that it generates (Steger Citation2008). In this third picture, the resurgence of ethno-nationalist thinking has led to a shift away from multiculturalism and emancipative values. Finally, the fourth “anarchism” poster is focused around the temporal distance between its desired vision of the future (to the left) and present day political realities (to the right) as divided by an envisioned temporal rupture or “revolution.”

While I have chosen these particular four posters in part due to their artistic qualities and accessibility to a non-Swedish-speaking audience, I must say that I have generally been impressed by the work that the students have produced in these seminars. However, it is worth pointing out that, sometimes, a well-thought-out mind map can be just as useful for facilitating peer learning as more advanced art work.

Student response and evaluation

Over the four semesters that I have used this seminar format, I have asked the students specifically about the gallery walk seminar in the written (anonymous) course evaluations. An overwhelming majority of the students (above 90%) state that they appreciated the gallery walk seminar and thought that it contributed to their overall learning, often emphasizing its interactive nature and how it encouraged broad participation. As an illustration, I have translated a few sample comments:

“I really liked the seminar format! Appropriate group size for presentation and fun subjects to think about.”

“The seminar was more valuable than I had expected and gave more thanks to that you got to hear different views and not only those of a few students”

“More rewarding, one could dive deeper and make one’s knowledge relevant.”

“Great seminar! It made it easy for each individual to participate and get new perspectives and ideas through the discussions.”

“Personally I prefer more traditional seminars as they tend to give more knowledge, but exciting with something different. Valuable in other ways.”

Although I have not received any negative feedback from the students, it is worth emphasizing that I see the gallery walk seminar activity as a complement and not as a substitute to more traditional didactic learning activities. Conceptualized in relation to Benjamin Bloom’s classic taxonomy (Bloom Citation1964), this means that while I use lectures for the lower levels of the taxonomy—e.g., knowledge and comprehension—the gallery walk seminar has more of a synthesizing function as it allows the students to apply what they have learned through the lectures but also make a qualitative evaluation of what it means in relation to their own values and ideological assumptions.

Unfortunately, in terms of its pedagogical effects, the fact that the gallery walk seminar is so integrated in the course makes it difficult to evaluate its specific contribution to learning beyond what the students themselves convey in the written course evaluations. Yet, I have repeatedly seen how themes from the posters reappear in the final take-home exams and how students have sharpened their arguments in response to feedback they have received at the seminar.

From the teacher’s perspective, one possible disadvantage with the gallery walk seminar format is that it is fairly time consuming compared to a traditional seminar. With about 50 students taking this course each semester at Umeå University, I have to run the seminar twice, normally as one morning (9 a.m.–12 p.m.) and one afternoon (1 p.m.–4 p.m.) session. While it may be possible to shorten the time allocated for the seminar, that would take away much of the added value in terms of modulation and peer learning.

Conclusions

Throughout, and in line with Laurillard (Citation2002), I strive to achieve a democratic learning environment that encourages iterative dialogue and puts emphasis on “the participants’ conceptions, and the variation between them” (73). By working together in groups and creating posters, the students have to modulate their different conceptions and collectively make sense of what they have learned. As each student not only has to present the poster but also be prepared to answer questions from the other students during the gallery walk, there is much less of an incentive to free-ride compared with a more traditional group assignment. This also potentially gives voice to students who otherwise would be marginalized by their more assertive peers.

In conclusion, the gallery walk format offers a useful, albeit time consuming, substitute to traditional literature seminars that encourages active learning, broad participation, and the practicing of higher-level skills such as synthesis and evaluation. While of course not limited to the teaching of political ideologies, I consider the format particularly useful for making undergraduate students develop a deeper understanding of political ideologies and how differently these ideologies may view the future.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Jonathan Symons as well as three anonymous referees for valuable comments.

Note

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Rasmus Karlsson

Rasmus Karlsson is an Associate Professor in political science at Umeå University.

He has published widely on climate mitigation policy, development ethics, and global affairs.

Notes

1 This research was carried out according to the ethical guidelines of Umeå University, Sweden. All students were fully informed that the gallery walk seminar would form the basis of a pedagogical article. The students whose artwork is included have given their explicit consent to this. The students were informed that not consenting would not negatively affect their grade. No personal data were stored in relation to this research.

References

- Bacchi, Carol. 2012. “Why Study Problematizations? Making Politics Visible. Open Journal of Political Science 2 (1):1. doi: 10.4236/ojps.2012.21001.

- Baylouny, Anne Marie. 2009. “Seeing other Sides: Nongame Simulations and Alternative Perspectives of Middle East conflict.” Journal of Political Science Education 5 (3):214–232. doi: 10.1080/15512160903035658.

- Bloom, Benjamin S., and Committee of College and University Examiners. (1964). Taxonomy of Educational Objectives (Vol. 2). New York: Longmans, Green.

- Chin, Chee Keong, Kwan Hooi Khor, and Tiam Kian Teh. (2015). Is Gallery Walk an Effective Teaching and Learning Strategy for Biology? In Biology Education and Research in a Changing Planet, ed. Esther Gnanamalar Sarojini Daniel (pp.55–59). Singapore: Springer.

- Diller, Ann. 2018. The Gender Question in Education: Theory, Pedagogy, and Politics. London: Routledge.

- Francek, Mark. 2006. “Promoting Discussion in the Science Classroom Using Gallery Walks.” Journal of College Science Teaching, 36 (1):27.

- Freeden, M. (2003). Ideology: A Very Short Introduction (Vol. 95). Oxford University Press.

- Gerring, John. 1997. “Ideology: A Definitional Analysis.” Political Research Quarterly 50 (4):957–994. doi: 10.1177/106591299705000412.

- Heywood, Andrew. 2017. Political Ideologies: An introduction. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Jost, John T., Brian A. Nosek, and Samuel D. Gosling. 2008. “Ideology: Its Resurgence in Social, Personality, and Political Psychology.” Perspectives on Psychological Science 3 (2):126–136. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6916.2008.00070.x.

- Kahan, Dan M. 2013. “Ideology, Motivated Reasoning, and Cognitive Reflection: An Experimental Study.” Judgment and Decision Making, 8,407–424.

- Karlsson, Rasmus. 2005. “Why the Far-Future Matters to Democracy Today.” Futures 37 (10):1095–1103. doi: 10.1016/j.futures.2005.02.007.

- Kaufman-Osborn, T. V. (2010). Political theory as profession and as subfield? Political Research Quarterly, 63 (3):655–673.

- Laurillard, Diana. 2002. Rethinking University Teaching: A framework for the effective use of learning technologies. London: Routledge.

- Laurillard, Diana. 2013. Teaching As a Design Science: Building Pedagogical Patterns for Learning and Technology. London: Routledge.

- March, Andrew F. 2009. What is comparative political theory? The Review of Politics 71 (4):531–565. doi: 10.1017/S0034670509990672.

- Oros, Andrew L. 2007. Let's debate: Active learning encourages student participation and critical thinking. Journal of Political Science Education 3 (3):293–311. doi: 10.1080/15512160701558273.

- Steger, Manfred B. 2008. The rise of the global imaginary: Political ideologies from the French revolution to the global war on terror. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Symons, Jonathan, & Rasmus Karlsson. (2018). Ecomodernist citizenship: Rethinking political obligations in a climate-changed world. Citizenship Studies, 22 (7):685–704.

- von Glasersfeld, Ernst. 1995. “A Constructivist Approach to Teaching.” In Constructivism in Education eds. L.Steffe & J.Gale. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum,3–16.

- Wetherly, Paul. 2017. Political Ideologies. Oxford: Oxford University Press.