Abstract

The case for the use of simulations in political science seminars to provide illustrative learning of complex political process has been well demonstrated across a variety of sub-disciplines within political science. Their value to the teaching of European Union politics has also been explored and is particularly valuable for the EU’s numerous examples of complex decision-making processes. This is particularly true of the EU’s Qualified Majority of Voting (QMV) system used in its Council of Ministers. This article demonstrates the use of a QMV simulation for undergraduate EU politics classes. Achievement of learning outcomes was greatly improved versus the standard Socratic seminar method and was in confirmed student feedback.

Introduction

This article presents an in-class simulation for teaching European Union (EU) studies at undergraduate-level and in particular the “Qualified Majority Voting” (QMV) that takes place in the EU’s Council of Ministers. The QMV system, used for most EU decision-making on new legislation, is defined by a double majority voting system, one where, for a proposal for new legislation by the EU’s executive body—the European CommissionFootnote1—to pass, 55% of the member states in the Council must vote to approve itFootnote2 and this 55% must also represent 65% of the EU’s total population.Footnote3 The QMV simulation (hereafter abbreviated “QMVSim”) developed here, like other successful simulations, gives students a hands-on and interactive learning experience of this double-majority voting-based (65–55%) decision-making system in a single 1-h seminar session. The practical nature of the simulation has importantly enabled students to better understand the QMV system and the nature of intergovernmentalism in the EU more broadly. It has emerged as preferable to a traditional verbal recounting of the QMV process (by students and tutors) through the traditional, Socratic seminar.

This QMVSim starts out as a simplified model using a mock proposal for a new EU directiveFootnote4 but is designed to be developed into something closer to QMVs complex reality by students (using their pre-class reading) assisted by the seminar tutor. With new detail added the importance of key themes, such as consensus, state interests, and coalition politics are enacted and demonstrated, thus better grasped by students. This mock directive acts as a foil to give students a realistic view of the kinds of policy areas that the EU regulates, particularly in regard to the single market. Importantly, the role of the European Commission in the simulation, although minimal, provides a practical means to observe the inter-institutional politics of the EU (namely the interaction between the Council of Ministers and the Commission). Moreover, the QMV model can be expanded at a later week in the semester, where the full simulation ““Ordinary Legislative Procedure” (OLP)”, that includes QMV within it, would therefore introduce the European Parliament as well.

In delivering classes on the EU’s intergovernmental institutions, which in day-to-day policy-making terms sees QMV play a central role, the leading objective is for students to understand the process of QMV’s complex double-majority voting system in both a basic mechanical sense and, importantly, to grasp the processes of deliberation, negotiation, and consensus that define it. This also needs to encompass an understanding of why this double-majority system, why it was chosen, and what it does to bargaining between actors. This process aspect is the leading learning objective of the QMVSim as it leads to several other objectives critical to students’ learning of the subject. Drawn from this leading objective is the further objective that students be able to place the QMV regime within the broader OLP that governs most EU decision-making; more simply, students must also be able to situate the Council of Ministers (where QMV takes place) within the EU’s broader institutional system vis-à-vis the EU’s other institutions. A third important objective is theory development, with the opportunity for students to introduce theory themselves into the simulation. This takes two forms: one concerns the theoretical debates in European integration theory and the other is broader and asks students to engage with the politics of coalition building, political economy understandings of state interests, big state-small state interactions, and international relations theory.

The students with which this has been employed have been second year undergraduate students in politics (or aligned Degree subjects) and for the most part had not previously studied the EU as an academic subject. These students, therefore, came into the subject needing a basic introductory education into European Union processes, like QMV, that are different and more complicated than those found in their national politics. In a standard, discussion-based Socratic seminar, the discursive shared learning of these processes would have to occur with a greater distance between the student and the operational realities of QMV with an unavoidably higher degree of abstraction. The technical and multi-level aspects of a process can appear both dry and complex, so can be engaged with much better in a simulation than in the traditional seminar.

This article begins with a brief overview of the existing use of simulations in European integration studies and situates that offered here within this. This is then followed by a main section detailing the process of the QMVSim’s operation and its virtues. This is then followed by an assessment of the simulation and future development.

The use of simulations in EU studies

The strengths of in-class simulations for political science teaching have been demonstrated in the pages of this journal (Perry and Robichaud Citation2020; Baranowski Citation2006; Baranowski and Weir Citation2015; Asal and Kratoville Citation2013; Shellman et al. Citation2006; Gorton and Havercroft Citation2012). EU studies have also made use of simulations, but examples of their use in delivering individual seminar classes are limited and have usually has pursued outside of taught classes in student conferences (e.g. Clark et al. Citation2017; Jones and Bursens Citation2014). In the area of European integration studies, Lightfoot and Maurer (Citation2014), Jones (Citation2008), and Clark et al. (Citation2017) have developed several simulation models. Unlike the single seminar-based simulation presented here, both Clark et al. (Citation2017) and Jones and Bursens (Citation2014) offer simulations designed for multi-day conference settings (“Eurosim”), which are too different in format and scale to be viable in a single taught seminar. These certainly lend more support for simulations and the level of engagement students achieve by being absorbed in role-based learning of policy processes. Brunazzo and Settembri (Citation2015) present a simulation much closer to that offered here but differs in important ways. The Brunazzo and Settembri model appears to require more time than that available in a typical 50–60 minute seminar as well as much more prior knowledge on the part of the student. Brunazzo and Settembri note that “simplification is one inevitable characteristic of simulations,” but their simulation is much more detailed than that offered here and, it is argued, too much so for students who have not studied the EU political system previously. Brunazzo and Settembri use a real world proposal (European Citizens’ initiative) as the foil for their simulation, whilst that offered here uses a fictional and simplified legislative proposal as it provides more space to address the QMV process rather than any excessive detail of new policy. The learning outcomes here are about the process and not any aspect of policy (although some secondary learning can occur here too). Moreover, Brunazzo and Settembri do. Brunazzo and Settembri claim that “there is little or no time for national positions to be articulated,” yet the QMVSim offered explicitly indulges this and places students into the roles of member states as this is essential for elements of “process” to be learned. This QMVSim places these roles centrally into the simulation and allows students to develop these. Again, this simplification is not only there to enable a starting point introduction to intergovernmental deliberation in the EU, but also to allow students to develop their knowledge and think creatively and add to the model themselves before, during, and after class.

Organization, materials, and process

Organization and materials

The organization of the QMVsim begins with students sat in an oval shape in the class room to replicate and affect a deliberative and vote-based forum, such as the Council of Ministers. Each student is turned into a member state. The seminar tutor anoints themselves as the European Commission that is proposing a mock proposal for a new EU directive (as is the Commission’s role). Before the class, students are advised to familiarize themselves with the broader OLP that contains QMV, but the tutor should briefly run through this at the beginning using a visual aid/overhead slide. Students are instructed to read Nugent (Citation2015), given its clarity and its coverage of issues presented by eastward (post-2004) enlargement on Council deliberations, as well as Golub (Citation2012) and Naurin (Citation2018).

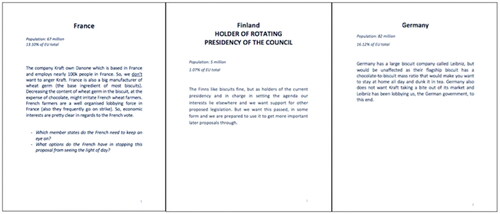

As is typical in most seminars (capacity 12–15 students) there are not 28Footnote5 students present to have all 28 members states (at the time of writing; 27 post-Brexit) to be represented in the QMV simulation, but at least 11–12 students should be present. Each student is provided a single sheet of A4 paper (“a brief”), with the member state’s name on top and that member states’ interests described on that brief. Each student/member state is then handed another “brief” with the mock proposal on it. This is simply for their information, as this mock proposal will be read out. One student will be the member state holding the rotating presidency of the Council. The students are then asked as to the significance of this rotating presidency role so as to draw out the first item of knowledge from their reading.

The tutor, again acting as the Commission, can read out the proposal, but it is also advantageous to ask the student acting out the Council of Minister’s’ President to read outFootnote6 the mock proposal instead.

Materials

Council of Ministers’ voting calculator from the Council website (on projector)

Member state: statement of interests (A4 brief)

Mock proposal for new legislation

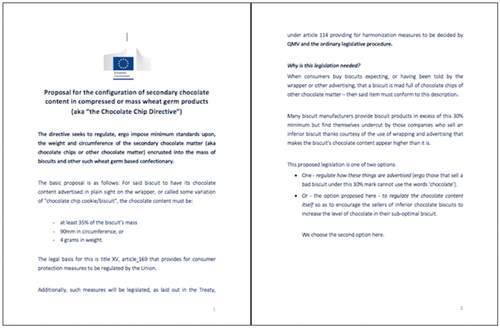

The subject matter for this mock proposal is again fictional, but contains realistic elements of the EU’s political system. The mock proposal () offers a policy change as to how the chocolate content of biscuits is regulated, and more precisely seeks to create minimum standards therein (minimum 35% chocolate matter, 90 mm in circumference, or 4 g in weight) ().

Again, rather than use a real example of EU legislation that might be too lengthy and detailed, this mock proposal was designed to be simpler as the details of the actual proposal are less important than the processes in question; to reiterate, the learning objectives are to demonstrate the operation of QMV’s double-majority system and its politics of coalitions and consensus-building. Those realistic aspects the mock proposal represents is found in the cross-cutting policy subjects it raises. This includes subjects of product regulation, consumer rights, and the national interests these raise, that European legislation addresses all the time; this also raises the abstract (but critical subject in EU terms) ofthe single European market. Bringing these together, this mock proposal raises two potent areas of the EU’s ‘competence‘ or remit: regulating the free movement of goods in Europe and the harmonization of rules for the purposes of consumer protection. A particular harmonized set of standards were proposed in the QMVSim’s mock directive, standards that would please particular producers of biscuits (high quality manufacturers) but would not please others (low quality manufacturers). Added geo-political and political economy contrivances are also constructed into the QMVSim: a large non-European, multi-national corporate actor, Kraft, acts as a private sector lobbying actor and, crucially, an opponent to the proposed directive. Other interests supporting the directive are found in domestic actors that also lobby member states (from within these countries). These different economic interests are partly fictitious and partly not, but nonetheless represent abstracted examples of real world realities that are very relevant to EU policy-making.

This mock directive is also designed to allow discussion to go beyond this particular tradable food product. An important inside-the-model–outside-the-model aspect is incorporated so that an opportunity is allowed for other policy topics to be brought in by students to add further detail. The Council of Ministers will not only be looking toward any single proposal at any one time, but several proposals that are to come and some member states will still have recent successes or defeats with other proposals in their minds. Member states need to act on favors they have promised from previous council deliberations and seek new ones for later proposals. So alongside the economic interests presented, this tradable food stuff-based directive itself, there are clear policy interests both inside and outside the scope of this individual proposal, the latter of which can be brought into the simplified simulation to complicate it. Two member states’ interests in the model are in fact presented as being more concerned with other (later) proposals than the present mock proposal, indicating these member states’ openness to barter for votes.

Process

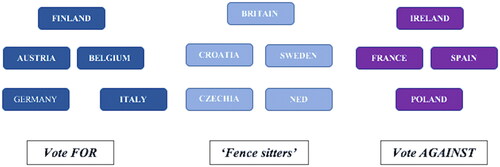

Once the proposal is presented, the students are asked in a specific order, starting with the Council president, to read out their briefs describing their interests that predicate their member state’s position on the proposal. Students are importantly also told to think about other members’ interests as well as their own. As the class hears from each “member state,” the member states that favor the proposed legislation and those which do not becomes clear. It also becomes clear that a third category emerges, one that has conflicting sets of interests making their position much less clear. This third “fence sitter” category of the member state is centrally important to the process as these constitute the fulcrum of the coalition-building process in the council. These “fence sitter” votes can be persuaded to vote “yes” or “no” by various aspects concerning the proposal itself (“inside the model”) or those things not relevant to the proposal (“outside the model”). This is the first invitation for students to think a little harder about what that member state’s position might be and to add new detail themselves to guide the process (the seminar tutor can also assist with this).

Once the member state interest briefs have each been presented, the tutor recaps the process and the 65–55% voting rule of QMV and shows the students the online Council of Ministers’ voting calculator on a projector. Importantly, the tutor then asks students “how often do formal votes in the Council actually take place?” with those who read Nugent (Citation2015) raising the approximate 20% figure raised in this article. This then raises the obvious question about what happens the rest of the time. This prompts the first theoretical discussion and the role of a consensus principle that guides Council deliberations. This raises a further discussion, again flowing from the Nugent article, concerning post-2004 EU enlargement and how this consensus principle (that so often avoided the need for formal voting) has persisted, despite enlargement by definition widening the number of actors and diversity and complexity in the Council of Ministers.

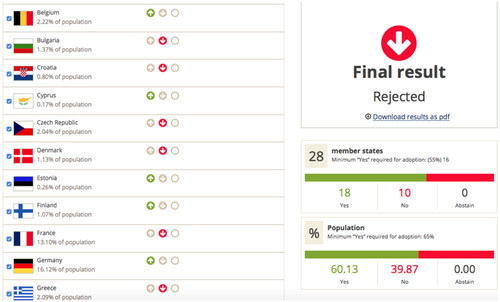

Despite this 20% number, the point is made that the voting arithmetic of the QMV vote is still clearly being calculated by all the member states in the room so that all potential outcomes can be played out, particularly by those member states who have a vested interest in getting a proposal passed or defeated. For this reason, a formal vote is then staged by asking each student how they think they and their counterparts would vote and then adding these into the Council of Ministers’ voting calculator one-by-one ().

Figure 3. Mapping member state interests: Yes votes (left), No votes (right), “fence sitters” (center), and the proposal (top center).

Additionally, the different positions of the member states are mapped out on a white board into for, against, and fence sitter categories. With this, some discussion is indulged around fence sitters and their conflicting interests. For example, the interests of Italy are specifically designed to only lean in favor (hence its slightly right-ward position in ), but not so clearly as, for example, Germany. Similarly to Germany, Italy’s interests saw a potent set of domestic interests (a high quality domestic biscuit confectioner) support the directive as the new standards would not affect them. Italy’s interested were however positioned to be concerned about possible takeovers of Italian biscuit confectioners by foreign companies like Kraft, something that had happened in Britain and France. In elevating the issues of takeovers, a contemporary theme in the European single market, the outlines of a “liberal intergovernmental” design become apparent to those students who have read about this renowned theory of Andrew Moravcsik (although not necessary at this point of the course). The point is made by the tutor that the EU encourages such cross-border takeovers as part of both the EU’s competition and single market programmes. This is useful secondary information, albeit parenthetical, for the student as it informs them further about what the single market is about. The prospect of a Kraft-led takeover is raised in regard to Italy, complicating their interests in regard to the proposal. For the sake of this mock QMV vote, however, it is important that Italy is kept on the “yes” side of this proposal so after a discussion Italy’s is kept in the “yes” camp. The role of BritainFootnote7 in the QMVSim also presents conflicting concerns in regard to the company Kraft. Here, realworld events concerning Kraft’s activities in Britain are used to construct the Britain’s interests, which see the company buying up Britain’s famous Cadbury company and reneging on promises not to cut jobs at Cadbury’s manufacturing plant in the English midlands. This positions Britain as an opponent of Kraft and therefore supporting the mock proposal (which, again, Kraft is not in favor of).

Croatia and Sweden represent important demonstrations of another dynamic: as proxies for external factors to be introduced and, specifically have their interests set around other legislative proposals outside this proposal that they regard as more important to them. In prioritizing other legislative goals, these two member states’ votes are up for grabs as they can trade their support for this proposal in exchange for voting yes or no on another proposal (in this case, a contrived “anti-pollution” measure). One member however wants this measure to be as strong as possible (Sweden), whilst the other (Croatia) wants it weakened. These mutually exclusive interests of these two countries have an important descriptive purpose, as it introduces students to the reality of any legislative process where voting actors care more about later legislation yet to be introduced and act accordingly to shape it within the legislation that is currently in front of them. This contrives an opportunity cost for those that want the current proposal passed and points them toward the larger member state (Sweden) to increase the chances of passage.

In putting each of these member states’ interests together, the tutor asks each member state to declare how they are voting. Using the voting calculator and putting it up on the projector in the classroom, the votes are tallied with the result seeing the proposal rejected ().

Two points from earlier are repeated: The first is that most of the time formal votes do not actually take place (only about 20% of the time). Yet, and second, each member state who has a vested interest in getting the proposal defeated or passed are still “doing the maths” based on assumptions about how other members may vote. These two points are made to reiterate that this QMV “outcome” is not a final result, so leads to a critical discussion about what member states who support the proposal need to do to get it to pass. The rotating Council president, the Commission (the tutor) alongside proponents then lead an out-loud discussion about which member states could be brought on board, and which member states are needed to be brought on board for the proposal to pass. This leads to a further discussion about what changes to the proposal would be needed to get the proposal to pass. The tutor reiterates the emphasis on the consensus that exists in Council deliberations and that member states who support a proposal are willing to see it weakened, up to it a point. To repeat, the original proposal for regulating the chocolate content of biscuits proposed a single biscuit consisting of 35% chocolate matter, 90 mm in circumference, or 4 g in weight. Students would offer to lower all or some of these three sets of figures (i.e. 28% down from 30%, 70 mm down from 90 mm, or similar). Then the opponents are identified once more with the largest opponents (France, Spain) focused upon. Reminding students posing as these two member states that consensus is the guiding principle in the room, they are then asked if they are prepared to accept a counter proposal. This presents an opportunity for students to think creatively and suggestions for amendments can be made from these, or other, member states. Eventually, the proponents of the original proposal (including the larger countries) will decide if they will accept the weaker proposal generated by this discussion. This leads to deliberations that see the students not having enough information to know if country X will or not accept new proposals. Even with the abstract goal of “consensus” is given to students, it is difficult for them to assume what a particular country would do. However, the point is that students begin to grasp a process that is governed by a complicated interaction of economic and political interests on the one hand and the desire to forge consensus on the other.

The outcome may or may not see the proposed directive passed, and it is not particularly important as it is the process that is important and to understand outcomes only as that guided by this process.

Assessing the simulation’s effectiveness

This section will address the effectiveness of the simulation and how this is measured. No matter the form that such an assessment takes (quantitative/statistical or qualitative), the learning objectives from the outset must be clear. The learning objectives of the simulation presented in the introduction are outlined again.

The leading objective is for students to understand QMV in simple process terms and its bargaining process in particular. Students should understand the purposes of the double-majority system and the kinds of bargaining this produces between member states of different sizes and interests.

Secondly, the QMVSim enables students to place the Council of Ministers and the QMV system within a broader EU institutional system.

Thirdly, the QMV seeks students to engage, and introduce, EU integration theory and as well as broader theoretical perspectives concerning coalitional politics, that drawn from political economy (as the design of this particular simulation encourages) and from international relations.

The assessment of the QMVSim itself has been built over several years and has included anecdotal assessments of comparisons between the QMVSim with the “standard” Socratic teaching of QMV and EU legislative processes. With this, reviews of the quality and nature of student performance have been gleaned from student assessments. Student feedback (at mid-semester and end-of-semester points) has also been central to assessing the QMVSim’s effectiveness. Although useful, a much more rigorous set of indicators is required to gauge learning outcomes. The first attempt to remedy this came by placing a short test in the mid-term student review of the module. These asked both more basic questions about the elements of the process and more substantive questions designed to gauge the student’s understanding of more complex themes. This latter element is more inductive and qualitative. This included asking which institution (Council, Parliament, the Commission) did what in and around QMV (and the OLP) and some more complex questions to gauge understanding, such as asking why such a double-majority regime is used and whom it benefits (e.g. big states or small states).

Where is QMV placed in the EU’s Ordinary Legislative Procedure?

What are the institutions involved in QMV?

What does QMV tell you about the interactions between member states?

What impressions does the simulation give you about EU integration theory?

Comparing your reading of the QMV process before the simulation, what questions or reflections do you have about QMV and how we understand it?

The qualitative nature of these questions, as supposed to the quantitative approach that is a popular form of learning outcome assessment in journals like this one, is appropriate given the centrality of students’ knowledge of the dynamic, intricate and innately qualitative process that defines QMV. As Cole and De Maio (Citation2009) note, standardized statistical modes of measuring learning outcomes have their strengths but crucially lack contextual and process-based information. This final question above is perhaps the most important as it asks students to examine their independent learning through reading about QMV and then compare this to the dynamic form of shared learning through the QMVSim.

Conclusion

The QMVSim provides a constructed venue for learning about the processes of the EU’s intergovernmental elements. Students are forced the think creatively about legislative processes and policy end-goals, particularly in a transnational, deliberative context, such as the EU’s Council of Ministers. Moreover, it provides empirical policy subjects with opportunities to introduce theoretical discussions. The QMVSim presents opportunities for further development, including being expanded into a broader simulation of the overall ordinary legislative procedure of the EU. This would extend the learning benefits of simulations beyond one class and further engage students by the complementing standard seminar format used on the module with engaging re-formatted seminars to diversity the taught content of the module.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Heidi Maurer of the Danube University Krems for reading an earlier draft and for providing helpful comments. I would also like to thank Simon Lightfoot and Charlie Dannreuther at the University of Leeds and Sophia Price and Leeds Beckett University for their advice and helpful comments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Andrew J. B. Morton

Andrew J. B. Morton graduated from the University of Leeds with his Doctorate Degree in 2019. His research and teaching interests include European integration, comparative political economy and policy studies. He currently works at Leeds Trinity University. Materials for this simulation are available on request.

Notes

1 QMV itself is part of what is called the “Ordinary Legislative Procedure” (OLP) of the EU. Before the Treaty of Lisbon of 2009, it was called “co-decision,” and its sees the European Commission produce legislative proposals that go to the Council of Ministers (where QMV takes place) and the European Parliament. For more information: https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/council-eu/voting-system/qualified-majority/.

2 With 27 member states, this means 55% is achieved with 15 member states voting for/against. This simulation was also taught before and after the U.K. left the EU.

3 The QMV regime was created in the 1985 Treaty called “the Single European Act.”

4 Directives are one of the two forms of legislation in the EU, regulations are the other.

5 Before the UK had left the EU. The EU now has 27 member states.

6 Students are asked, per a University’s inclusiveness policy, if they are comfortable reading things out in front of class.

7 Britain’s exit from the EU had not occurred at this point so was kept in the simulation.

References

- Asal, Victor, and Jayson Kratoville. 2013. “Constructing International Relations Simulations–Examining the Pedagogy of IR Simulations through a Constructivist Learning Theory Lens.” Journal of Political Science Education 9 (2):132–143. doi:10.1080/15512169.2013.770982.

- Baranowski, Michael K., and Kimberly A. Weir. 2015. “Political Simulations: What We Know, What we Think We Know, and What We Still Need to Know.” Journal of Political Science Education 11 (4):391–403. doi:10.1080/15512169.2015.1065748.

- Baranowski, Michael. 2006. “Single Session Simulations–The Effectiveness of Short Congressional Simulations in Introductory American Government Classes.” Journal of Political Science Education 2 (1):33–49. doi:10.1080/15512160500484135.

- Brunazzo, Marco, and Pierpaolo Settembri. 2015. “Teaching the European Union: A Simulation of Council’s Negotiations.” European Political Science 14 (1):1–14. doi:10.1057/eps.2014.34.

- Clark, Nicholas, Gretchen Van Dyke, Peter Loedel, John Scherpereel, and Andreas Sobisch. 2017. “EU Simulations and Engagement: Motivating Greater Interest in European Union Politics.” Journal of Political Science Education 13 (2):152–170. doi:10.1080/15512169.2016.1250009.

- Cole, Alexandra, and Jennifer De Maio. 2009. “What We Learned about Our Assessment Program That Has Nothing to Do with Student Learning Outcomes.” Journal of Political Science Education 5(4):294–314. doi:10.1080/15512160903253368.

- Golub, Jonathan. 2012. “How the European Union Does Not Work: National Bargaining Success in the Council of Ministers.” Journal of European Public Policy 19 (9):1294–1315. doi:10.1080/13501763.2012.693413.

- Gorton, William, and Jonathan Havercroft. 2012. “Using Historical Simulations to Teach Political Theory.” Journal of Political Science Education 8 (1):50–68. doi:10.1080/15512169.2012.641399.

- Jones, Rebecca and Peter Bursens. 2014. “Assessing EU Simulations: Evidence from the Trans-Atlantic EuroSim.” In Teaching and Learning the European Union, eds. S. Baroncelli, R. Farneti, I. Horga, and S. Vanhoonacker. Dordrecht: Springer, 199–215.

- Jones, Rebecca. 2008. “Evaluating a Cross-Continent EU Simulation.” Journal of Political Science Education 4 (4):404–434. doi:10.1080/15512160802413790.

- Lightfoot, Simon, and Heidi Maurer. 2014. “Introduction: Teaching European Studies – Old and New Tools for Student Engagement.” European Political Science 13 (1):1–3. doi:10.1057/eps.2013.28.

- Maurer, Heidi, and Neuhold Christine. 2014. “Problem-Based Learning in European Studies.” In Teaching and Learning the European Union, eds. S. Baroncelli, R. Farneti, I. Horga, and S. Vanhoonacker. Dordrecht: Springer, 199–215.

- Naurin, Daniel. 2018. “Liberal Intergovernmentalism in the Councils of the EU: A Baseline Theory.” Journal of Common Market Studies 56 (7):1526–1543. doi:10.1111/jcms.12786.

- Nugent, Niall. 2015. “Enlargements and Their Impact on EU Governance and Decision-Making.” Journal of Contemporary European Research 12 (1):424–439. doi:10.30950/jcer.v12i1.689.

- Perry, Tomer J., and Christopher Robichaud. 2020. “Teaching Ethics Using Simulations: Active Learning Exercises in Political Theory.” Journal of Political Science Education 16 (2):225–242. doi:10.1080/15512169.2019.1568879.

- Shellman, Stephen M., and Kürşad Turan. 2006. “Do Simulations Enhance Student Learning? An Empirical Evaluation of an IR Simulation.” Journal of Political Science Education 2 (1):19–32. doi:10.1080/15512160500484168.