Abstract

Students entering contemporary higher education have the question of employability at the forefront of their minds, both when deciding which institution to study at and which subject to study. However, the notion of the “employability agenda” is not often welcomed by academics. Focusing on teaching and learning in the UK, this article draws on Daubney’s (Citation2022) concept of “extracted employability” to ask what students of Politics and International Relations can expect in terms of employability outcomes from their degree and how that employability value can best be communicated. Highlighting resistance from academics and students to integrating employability into a demanding curriculum, this article, referencing the 2023 QAA Subject Benchmark Statement for Politics and International Relations, offers a subject-specific employability proposal. This suggestion could enhance Politics and International Relations degrees and be incorporated into institution-wide curricula and student recruitment activities. The Subject Benchmark Statement is utilized as a common understanding of the nature and standards of study in a subject area; one that can be applied in the delivery and promotion of degrees to help answer the call for those delivering Politics and International Relations teaching and learning to be more confident in their articulation of the employability value of a degree in the field.

Introduction

As most academics who have worked a student recruitment day or had discussions with undergraduate supervisees will attest to, the issue of employability is one at the forefront of students’ minds. Before beginning their studies, often even before choosing which subject they wish to study at university, students are worried about what their degree will mean for them in the world of work; whether it will lead to fruitful and enjoyable careers in the years to come. These questions of respective degrees’ employability value come not only from students, as well as parents, who have immediate personal investment in those outcomes. Increasingly, there is wider public and political interest in identifying a clear benefit in terms of earnings and employment from university degrees (Broms and de Fine Licht Citation2019; Norton Citation2019; Sin, Tavares, and Amaral 2017). This could be seen, for example, in the UK’s political debate over the summer of 2022, with discussions of limiting government support for ‘low-earning degrees’ (The Guardian Citation2022). This discourse is one of the latest ways that the ‘employability agenda’ (AdvanceHE Citation2019, 2) is marking higher education in the twenty-first century. Evidently, there is a need for academics across the full range of degree-level subjects to plainly identify and articulate what it is that their field offers both students and employers in terms of employability value. However, this is an agenda that is often resisted by those academics best placed to effectively respond to student needs, driven by concerns of being made to do too much “additional” work.

Looking at the example of teaching and learning in the UK’s higher education sector, this article critically examines the discipline of Politics and International RelationsFootnote1 to assess the subject’s employability value and to make the case that academic concerns about the employability agenda can be eased through the adoption of a simple student-facing statement of that value. This examination draws together the academic literature on employability in the field, assessing a variety of differing perspectives to the inclusion of employability in Politics and International Relations curricula and resistance to changes that bring in such measures. Daubney’s (Citation2022) distinction between ‘extracted employability’ and ‘added employability’ is used here to argue that, given workload pressures and desires to preserve teaching norms, more should be made of the value of identifying extracted employability in Politics and International Relations curricula and promotion of the field to prospective undergraduate students. Therefore, using Daubney’s “KASE framework” for articulating the employability value of a subject (2022, 100), a framing of a student-facing statement on the employability value of Politics and International Relations is proposed at the resolution of this article. This statement draws on the fifth edition of the UK’s Quality Assurance Agency’s (QAA) Subject Benchmark Statement: Politics and International Relations (2023)—a key text in understanding the baseline expectations of what a Politics and International Relations degree in the UK would likely cover and might provide in terms of graduate outcomes. The use of this, or a modified, statement within teaching and learning and the promotion of degrees, has the potential for better preparing undergraduate students to voice what it is that sets them apart as graduates of Politics and International Relations to potential employers—something that this article highlights that students might not currently be best placed to do. It also has the potential benefit of winning over potential Politics and International Relations undergraduate students who are unsure of what the benefit of studying the subject will mean in terms of career advancement.

This article is organized as follows. Section I reviews the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning (SoTL) literature to discuss the confusion over defining the employability value of a degree in Politics and International Relations and the variations in career paths taken by those that study the subject. In this context, SoTL literature encompasses research and scholarly works that explore pedagogical approaches, educational practices, and their impact on student outcomes. Section II explores why there has been and continues to be resistance to the employability agenda in higher education in general, as well as the more specific issues facing the embedding of employability in the teaching and learning of Politics and International Relations. Section III introduces and adopts Daubney’s (Citation2022) concept of extracted employability, making a proposal for how the employability value of Politics and International Relations degrees might be defined and articulated. This final section draws on the 2023 revised Subject Benchmark Statement: Politics and International Relations from the QAA to make the proposal, providing a contemporary understanding of a shared framework for communicating the employability value of degrees in the discipline.

Section I: Employability in Politics and International Relations

Employability is a contested and debated term (Harvey Citation2001; Norton Citation2019). Williams et al. (Citation2016) highlight that the complex and nuanced contemporary world of employment has, in turn, complicated understandings of the concept of employability. Within this article, employability is understood to be the range of qualities that an individual needs to demonstrate and to have to gain employment. However, as this section details, the Politics and International Relations discipline and the career pathways that result from it, reveal a complex picture of what it means to be employable with a degree in the field but also ground the need for a shared understanding of what the general value of Politics and International Relations degrees can be.

Within the UK, the last decade has seen a sharp increase in the expectations on disciplines to engage with the employability agenda. This has largely been driven through the enterprise and entrepreneurship education (herein: EED) discourse, which was an evolution of the earlier work on entrepreneurship education (which is where the EED acronym originates from, for more on EED’s development see Hannon Citation2005). The QAA’s 2012 Enterprise and Entrepreneurship Education marked a turn to a more active engagement with employability with the intention that it would result in “a significant impact on the individual student in terms of successful careers, which in turn adds economic, social and cultural value to the UK” (QAA Citation2018, 2). Whilst all subjects are under increasing pressure to articulate their employability value, Politics and International Relations is one field in which this is by no means a new development. Both Harrison (Citation2012, 39) and Lightfoot (Citation2015, 114) vent their frustration in the academic literature about the oft repeated question asked of many Politics and International Relations students, “so are you going to become a politician?”. Whilst undoubtedly made frustrating by its repetition, the question does have an understandable cause; it is not immediately clear what degrees in Politics and International Relations are “for”. Even scholars in the discipline ask the question—“What is the point of a political science degree?” (Marineau Citation2020). This is to say, what can students in the field expect of life after they have completed their studies? The fraught nature of the employment question in Politics and International Relations is, interestingly, much more marked in the subject-specific SoTL literature in the UK than it is in the US. In a review of six US and UK Politics and International Relations SoTL journals, Blair (Citation2015) found that 3 per cent of US journal articles addressed the issue of employability, whereas 22 per cent did in the UK.

This sense of confusion over the point and purpose of a degree in Politics and International Relations at least partly originates from the largely non-vocational nature of the discipline (Broms and de Fine Licht Citation2019; Craig Citation2015; Harrison Citation2012). It is not that the ∼36,500 students currently enrolled in Politics and International Relations undergraduate programmes in the UK (HESA Citation2022) have all selected the degree because they think it is the next step toward becoming a Member of Parliament or Prime Minister (even with the increasingly rapid turnover of Prime Ministers in the UK, it would mean quite a number of students would have disappointed career plans if this was the case). Naturally, there are many students that want to go into politics-related careers (e.g. local government, think tanks, non-governmental organizations, etc.) and choose to study with that career in mind (Craig Citation2019). For these students, the emergence of practitioner-focused degrees is a notable development (e.g. Wyman, Lees-Marshment, and Herbert 2012; Craig Citation2010). However, the “end destination” of a degree is not something that all students have clearly in mind when their studies begin. The lack of primary career outcomes was identified in the first edition of the QAA Subject Benchmark Statement: Politics and International Relations which highlighted the diversity in post-degree fields of work (Harrison Citation2012, 40). Therefore, understanding the study-employability link is particularly interesting and important for Politics and International Relations. Harrison identifies what she terms as a “fuzzy link” between a Politics degree and a preferred career outcome, a link that has become a focus of developing curriculums:

This “fuzzy” link between a Politics degree and preferred career has become a central focus for curriculum development in many universities in recent years. Students opt for our subject because they have an “interest” in the subject matter, and enjoy the opportunity to develop skills such as critical analysis and problem solving (Harrison Citation2012, 39).

Nevertheless, despite the non-vocational nature of Politics and International Relations, there are still trends in terms of the employment choices that students make after graduation (Harrison Citation2012), trends for which Politics and International Relations curricula could do more to prepare students (Wyman, Lees-Marshment, and Herbet Citation2012). As detailed in , the UK graduate-careers organization Prospects details some of the options that students in the discipline might wish to consider. Academics who have had a few years’ experience of writing reference letters for graduates will likely recognize that even the range of career paths suggested in is limited when compared to the true variety of paths our graduates take. Not only is there a large variety in the different career paths that respective Politics and International Relations students embark on once they have graduated, but individual graduates are also now expected to be prepared for a variety of different careers throughout their working lives (Broms and de Fine Licht Citation2019). Williams et al. describe the “protean career and the rise in discussion of the boundaryless career” (2016, 878) as a sign of the greater emphasis on the individual’s perspective and experience of employability. Thijssen, Van der Heijden, and Rocco have noted this development stating that, “the ‘half life’ of [higher education] qualifications is becoming shorter” (2008, 166). Similarly, Allen and van den Velden (2011) highlight this trend as the rise of the “flexible professional” that has resulted from a globalized and ever-changing employment market. This demonstrates something of the difficulty of skills training to prepare Politics and International Relations students for a clear career path.

Table 1. Career path recommendations for Politics and International Relations students (Prospects Citation2021).

Whilst a primary motivation for undergraduate students in Politics and International Relations will be their interest in the field and the desire to expand their knowledge, employers don’t necessarily want graduates who have an extensive knowledge of politics, rather they want skilled graduates (Harrison Citation2012, 46; Hayton Citation2008, 209). One of the key issues that is raised in the SoTL literature is not that Politics and International Relations graduates lack employable skills; rather they lack a self-awareness of the skills that they developed over the course of their studies and the fact that these skills make them valuable to potential employers (Barrow, Innes, and Robertson Citation2023). Having a knowledge of the skills that make graduates employable is, of course, not exclusive to this discipline. As Harrison states, “A student of Politics needs, like many other students, to be able to articulate their achievements in a highly competitive graduate market” (Harrison Citation2012, 39). Whilst it is disappointing for someone to not get a job because someone better qualified did, it is all the worse to not get the job when one has the skills and the qualifications but did not properly understand that they did (Lightfoot Citation2015, 151). Whilst this might be an issue across disciplines, and although they were writing from a US perspective, Breuning, Parker, and Ishiyama highlight that this may well be a problem that particularly bedevils Politics and International Relations graduates:

Quite often, people make jokes at the expense of political science majors. These jokes suggest that political science majors—and especially those graduating from liberal arts colleges and universities—have not acquired the necessary practical skills to make a living, let alone to acquire a lucrative career… Only if our majors understand what they have learned and what skills they have to offer can they have the “last laugh” as they climb the successive rungs of the career ladder (2001, 657).

Section II: Resistance to change

Politics and International Relations has been noted in the SoTL literature as having a long-standing record of limited innovation (e.g. Ishiyama, Breuning, and Lopez Citation2006; Hamann, Pollock, and Wilson Citation2009, 130). One innovation that Ishiyama, Breuning, and Lopez have pushed is that academics should be more willing to present the employability value of a degree in the field, stating that “it is incumbent upon political scientists as educators to provide a rationale for students to take the courses we offer, to explain how the political science curriculum can help equip them for the challenges of their careers” (2006, 664). This change would, in-part, be made in response to student expectations, as Wyman, Lees-Marchmant, and Herbet state: “most students see the delivery of degree programmes as an implicit contract, where the costs of the degree programme legitimize questions as to what the outputs are, particularly in financial or career development terms” (2012, 238). However, the increased focus on the employability agenda has not been met with enthusiasm in all quarters. Daubney (Citation2022) found that, across disciplines, academics are often resistant to adding employability to an already well-established and designed curriculum. Politics and International Relations is no exception to this.

A core driver in the resistance to the employability agenda is that academics are already pressured by significant workloads (Graham Citation2015) and therefore resist any potential additions to this burden. Those responsible for teaching and learning on Politics and International Relations degrees are being asked to take an ever-greater account of student concerns (Wyman, Lees-Marshment, and Herbet Citation2012, 238), with future employment a central concern. Solutions such as increased engagement with academics to discuss future employment options (e.g. Chaturvedi and Guerrero Citation2022) or even the total redesign or creation of degrees to have a professionalized Politics and International Relations curriculum (e.g. Wyman, Lees-Marshment, and Herbet Citation2012) would involve significant increases to staff workloads. Furthermore, there is reason to doubt that asking academics to shoulder the burden of embedding employability into their curriculums is an efficacious path to engendering employability skills in students (Sin, Tavares, and Amaral 2019, 923–924), further validating academics’ resistance to adding such tasks to their workloads.

There is also resistance based on differing understandings of what academia is and what it should be. For example, Sin, Tavares and Amaral highlight the “long-standing academic resistance to outside political interference in academic affairs and to the vocationalisation of higher education” (2019, 921). Similarly, Maurer and Mawdsley (Citation2014) assert that much of academic resistance to the employability agenda is driven by concerns about a resulting weakening of academic rigor. These arguments feed into the idea that universities are meant to be centers for the pursuit of knowledge before anything else. It is worth noting that the resistance to the reframing of what constitutes a degree and to the employability agenda might be particularly pronounced in the field of Politics and International Relations because of the inherent features of the discipline and the interests of those that pursue careers in the field. Academics in the discipline may find the idea of becoming agents of the employability agenda a distasteful proposition (e.g. Pal Citation2022). In the SoTL literature there is the identification of a tension between “infusing concern for graduate outcomes within a pedagogic framework that emphasizes critical engagement with the underpinning political structures of the labor market” (Donna, Foster, and Snaith 2016, 95). This is a concern that Lightfoot similarly shares, wondering if the teaching of critical thinking (core to Politics and International Relations degrees) might be an anti-employability skill: “If we ask students to question the world around them, what happens when they gain employment and perhaps start questioning the power relations within the firm?” (2015, 146). Therefore, there may well be the need for sensitivity around the topic of employability in the delivery of Politics and International Relations teaching and learning.

Further to this, not all students enthusiastically pursue the inclusion of employability in their education. Whether students want to engage with employability material varies widely between the years of their undergraduate education, with students unsurprisingly being more favorable toward the content in the final year of their studies (Tymon Citation2013). Before this point, the employability agenda can be a “turn-off” (Lightfoot Citation2015, 152). Lee, Foster, and Snaith describe the existence of “a resistant or employability skills averse student body” (2016, 32) in the Politics and International Relations discipline, resulting at least partly from the apathy students have toward what they see as a “business-led skills agenda” (2016, 34). In the UK’s marketised higher education sector where the student is viewed (legally, at least) as a customer, concerns for quality that delivers “customer satisfaction” have become paramount (one common measure of this is the UK’s annual National Student Survey) (Calma and Dickson-Deane Citation2020). Therefore, despite awareness of its potential important benefits, any embedding of the employability agenda into Politics and International Relations curricula would need to be handled with sensitivity and care.

A common thread in the issues detailed above is a resistance to “too much”; whether it be too much new work for overloaded academics, too much of a departure from the traditional ideal of higher education, or too much unwanted material for students that signed up to learn about a subject and not necessarily how to be a good employee. This understanding of resistance to “too much” provides the basis for the proposal detailed in the following section.

Section III: Extracted employability

The concept of extracted employability is one developed by Daubney (Citation2022) as a contrast to that of added employability. This section introduces the two distinct concepts, before critically assessing the QAA’s fifth edition Subject Benchmark Statement: Politics and International Relations to develop a student-facing statement for use in programme delivery and promotion as a model of extracted employability.

Added employability

Added employability is the form of employability that will be most readily recognized as part of the employability agenda. It can be defined as “the teaching of employability, and sometimes careers education, by identifying content that can be added to a programme to enhance or supplement its innate extracted employability” (Daubney Citation2022, 98). Examples of added employability abound, including the creation and integration of employability-focused material into curricula, external partners providing input into learning design, and careers advice sessions as part of teaching delivery. On both sides of the Atlantic, one form of added employability in Politics and International Relations programmes that has seen a surge in popularity is the inclusion of credit-bearing work placements (Lucas Citation2023). These “deeper interventions” (Bozward et al. Citation2023) closely reflect the EED initiatives, called for by the QAA (Citation2012), which have shaped understandings of employability in the UK over the last decade. It is the inclusion of these additional activities and changes to degree programmes that often meet resistance (Pal Citation2022). As Daubney states: “added employability will be familiar to academics, careers professionals and students, as well as employers, and are often the content academics mean when they say, ‘teaching employability is not my job’” (2022, 98). This resistance provides a grounding for reconsidering approaches to employability by adopting an extractive method.

Extracted employability

Daubney defines extracted employability as the analysis and identification of the “innate employability value in a programme, subject or discipline” (2022, 97). Given the review of the various points of resistance to the employability agenda in the previous section, one can see the potential benefits of focusing attention on the concept of extracted employability. Whilst added employability might be marked as being “too much” in terms of change, additional work, and distraction from the norms of the curriculum, extracted employability ensures continuity but with an identified and shared understanding of that education’s employability benefits. The merit of extracted employability is in the fact that students often lack a self-awareness of the skills developed during their studies. This is a finding underpinned by research from the Institute of Student Employers (ISE) in the UK that finds that students not only lack self-awareness (Citation2020, 20) but also that it is the attribute that employers are most likely to be working to develop once graduates are hired (Citation2022, 41). It is a finding that has been a core driver of contemporary EED work in the UK (Barrow, Innes, and Robertson Citation2023, 1). The importance for developing student self-awareness has long-standing support in the SoTL literature. For example, Knight et al. warn and ask: “When employability-enhancing elements are only tacitly present, students’ claims to employability are seriously compromised. If your project fosters achievements valued by employers, does it also ensure that learners know this?” (Knight et al. Citation2003, p. 5). Therefore, ensuring the employability benefits of a degree are clearly identified has the capacity to directly benefit students’ employability outcomes.

While the concept of extracted employability is new, the idea of fostering employability self-awareness among Politics and International Relations students has been previously considered. Robinson (Citation2013) has argued that the development of student skills through innovative pedagogy and training is only useful if they understand what skills they are gaining through that teaching or training. Lightfoot has claimed that employability for Politics and International Relations courses is not dependent on adding new areas of teaching but that instead, “the key skills employers seek in graduates can be found in political science degree courses and that the role of faculty is to ensure the students are aware of this fact” (Lightfoot Citation2015, 144). It should be noted that there could be some areas of the discipline that do lend themselves more toward the easy extraction of employability skills and knowledge. For example, Maurer and Mawdsley (Citation2014) argue that European studies leads to the development of transferable skills actively engage with the specifities of the EU policy environment through their studies. One could contrast this with the teaching and learning of political theory where the direct relation to the development of employability skills might need highlighting. Nevertheless, Daubney’s proposal is that there is the opportunity for a model of extracted employability at the subject level, one that spans subdisciplines, and that more easily allows for students to develop a clear self-awareness of their developed skills, and that this shared understanding can be drawn from the QAA’s Subject Benchmark Statements.

Using the QAA subject Benchmark statements

The emergence of subject benchmarking in the UK during the 1990s was a response to the rapid increase in student enrollment. The initiative aimed to identify threshold standards across institutions and programs, while also informing students and employers about the potential knowledge and skills gained from a degree in the relevant field (Williams Citation2010). Whilst not a prescription for program standards, they can be a useful guideline for program design. Within the Politics and International Relations SoTL literature, a case has been made for the type of subject benchmarking that the QAA Subject Benchmark represents. Harrison highlights two ways to see these exercises as beneficial to the development of the field: “(1) a vehicle with which we can compare and contrast expectations regarding essential knowledge and skills, and (2) a regular review by which we can explore what is fit for purpose in addressing student expectations and needs” (Harrison Citation2012, 39). Daubney stresses that the Subject Benchmark Statements are important sites for “unearthing attributes and transferable skills” (2022, 100) engendered by completing a degree in a certain discipline and therefore an important starting point for identifying extracted employability.

The use of Subject Benchmark Statements is, however, one that is not insulated from potential criticism, especially in terms of outlining the employability value of the respective disciplines. For example, the membership of the advisory groups that create the Subject Benchmark Statements overwhelmingly consists of academics. This is an issue when assessing a subject’s employability value. As Harrison states:

I am probably not alone in suggesting that academics are almost certainly not the best career advisors. In setting the curriculum we should be more willing to consult key employers – public administrators, professional communicators and business managers to ensure what we deliver is fit for purpose in relation to both academic content and skills (2012, 45).

The 2023 Subject Benchmark Statement marked an important development in terms of employability. For the first time, the statement included an EED section that directly engaged with engendering employability (this section is a part of all new and revised Subject Benchmark Statements). Importantly, the EED section reflects a mix of extracted and added employability with reference to the identification of skills that are developed through the course of studies (extracted) and those developed through the “promotion” of employability activities (added). The 2023 Subject Benchmark Statement for Politics and International Relations highlights areas for potential improvement in aligning with the assertions presented in the SoTL literature discussed in this article. One example is the statement’s emphasis on how Politics and International Relations courses purportedly assist students in recognizing, reflecting on, and communicating the value of entrepreneurial behaviors, attributes, and competencies both during and after university (QAA Citation2023, 7). This assertion prompts consideration of the existing perceptions among students and scholars who may not fully perceive the employability value of Politics and International Relations degrees. Still, given that it is the one core review of subject content and outcomes in UK higher education, it remains a compelling subject of study and considered application. Furthermore, the utilization of the common framework of a Subject Benchmark Statement, which makes broad generalizations about the outcomes of respective degrees, may also help build a clearer common understanding about the value of that degree, beyond those that are most familiar with the field.

Articulating the employability value of politics and international relations

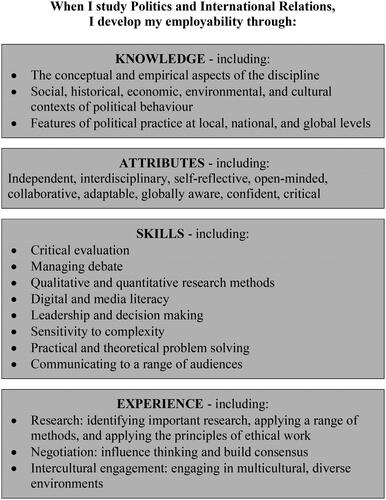

Daubney proposes that understanding the employability value of a subject can be started through the close reading and careful analysis of the QAA Subject Benchmark Statement for that discipline and that this “process of articulating the employability innate to a subject can then be refined into a student-facing statement at programme level” (Daubney Citation2022, 100). Daubney suggests a model for this, a figure composed of four key areas (knowledge, attributes, skills, experience) in response to the statement “When I study [subject name], I develop my employability through…” (Daubney Citation2022, 101). The four key areas are elucidated upon as follows:

Knowledge: the acquisition of specialist knowledge through a range of contexts, but also the ability to learn.

Attributes: qualities (I am…), behaviors (I act to…), values (I believe in…)

Skills: subject-specialist, profession-specialist, transferable and career management.

Experience: the application of knowledge, attributes and skills in and alongside the degree (Daubney Citation2022, 97).

The acronymised label of “KASE framework” is used to identify these four points and the overall framing. Through an analysis of the 2023 fifth edition Subject Benchmark Statement: Politics and International Relations, relevant statements were coded in line with the four areas of the KASE framework (knowledge, attributes, skills, experience) to develop a student-facing statement of the discipline’s employability value, based on the idea of extracted employability (i.e. without additional embedding of employability in the course’s teaching and learning). A core component of the student-facing statement is brevity. Such a statement needs to communicate the benefits of undertaking a particular degree concisely and effectively without seeming to do “too much”, for the reasons outlined above. Therefore, a comparison of statements within the same codes identified areas of overlap and consistent themes for each of the four areas, which was the basis of determining key summarizing words and statements for the student-facing statement. The resulting statement is shown in .

Figure 1. Student-facing statement of Politics and International Relations innate employability value.

highlights the themes that were identified through the analysis of the fifth edition Subject Benchmark Statement: Politics and International Relations. These themes are unlikely to be a surprise to those working in the delivery of university-level courses in Politics and International Relations – some might also not be remarkable to the unfamiliar learner and may confirm expectations. The emphasis on debate, criticality, confidence, and leadership skills, for example, might not put to rest the oft-repeated question asked of Politics and International Relations “so are you going to become a politician?” (Harrison Citation2012, 39; Lightfoot Citation2015, 114). However, these are features strongly emphasized in the document. Still, for a current or prospective student, this articulation could serve as a useful reminder of the employability value of their degree and give clarity to how they may develop through their studies.

A reader of the Subject Benchmark Statement: Politics and International Relations (QAA Citation2023), or of the student-facing statement shown in , will likely be struck by the breadth and lack of precise details, for example, of gained knowledge. This is partly a result of the need for breadth in bringing together courses taught at many different universities, each having variations in modules and learning foci. However, there is also something specific to the Politics and International Relations case here. It would not be possible, for example, to replicate a point of knowledge as in Daubney’s case study of the QAA Subject Benchmark Statement for History – wherein students could be assured that they would gain knowledge on “Europe: 1750–1919” and “Global security dynamics since 1989” (Daubney Citation2022, 101). As the analyzed Subject Benchmark Statement addresses, “The scope of Politics and International Relations is broad, and the boundaries of the discipline are often contested and in movement” (QAA Citation2023, 3). There is also much that is understated in the brevity of and fails to fully demonstrate areas where the Politics and International Relations has managed to evolve and innovate. For example, the inclusion of “qualitative and quantitative research methods” does not fully represent the extent to which quantitative methods have developed to become much more accepted and established in contemporary UK social science teaching through recent innovations, for example the Q-Step project, as well as varieties that still exist between institutions in this transition (Ferrie and Spreckelsen Citation2023). Therefore, the proposal laid out in for a student-facing articulation of Politics and International Relations may well be more of a starting point than a final word. The possibility of using the Subject Benchmark Statements is something that Daubney recognizes, stating: “Where curriculum statements exist at subject level, these can be a useful starting point for unearthing attributes and transferable skills” (Daubney Citation2022, 100). At the institutional, departmental, modular, and even the individual instructor level, adjustments could be made to stress the specifities of learning styles, subject focus, and employability outcomes.

Creating department- or module-specific versions of is an exercise that could go beyond the “lone scholar” approach used here to make the proposal. Similar curriculum innovations have, to increase the potential for buy-in, democratized the design process by including students (Harding Citation2023). A collaborative coding and exercise of the Subject Benchmark Statement could be one pathway to democratize this process. Some degree of faculty support would also be necessary to ensure successful coordination and dissemination. Whilst this may run into the challenges detailed in Section II, given the small initial time costs in developing a student-facing statement as shown in relative to the demands of added employability, this is a measure of employability that might find wider support amongst academics. This collaborative approach is one that could likewise be of use in non-UK contexts, where the UK-based Subject Benchmark Statement (if no national comparison exists) could be the basis of discussions around identifying the inherent employability value of a degree in Politics and International Relations by assessing areas of similarity and difference. The brevity and simplicity of the KASE framework’s structure has the double benefit of not seeming to do “too much” but also providing a reusable student-facing statement that could resonate with both current, as well as potential, undergraduate students. An employability-focused piece of media such as this should have easy application at, for example, open days and other student recruitment activities, on Politics and International Relations programme webpages, as well as in the delivery of undergraduate modules – whether that be in teaching sessions or on a module’s virtual learning environment webpage. Even if modifications were made by, for example, different instructors or departments, the easy reapplication of emphasizing the extracted employability of a students’ degree would compare favorably to developing added employability content and material in terms of workload burden for academic staff. In fact, repeated use of such a statement would also have the benefit of helping inculcate the employability value of their degree into students’ minds, so that when they begin to pitch themselves to potential employers, an awareness of their knowledge, attributes, skills, and experience will be readily available.

Conclusion

Contemporary Politics and International Relations graduates are entering a more competitive, precarious, and variable world of work than those of previous generations. Whilst this is an experience that they will likely share with their peers across a range of degree specialisms, the SoTL literature reviewed in this article identifies Politics and International Relations as a field that particularly struggles to articulate its employability value (Marineau Citation2020)—in part because of the non-vocational nature of the subject (Broms and de Fine Licht Citation2019; Craig Citation2015; Harrison Citation2012). This struggle would also appear to be a point of particular concern in the UK, given the level of attention given to the issue in the UK’s SoTL literature (Blair Citation2015). Therefore, this article has analyzed the 2023 fifth edition Subject Benchmark Statement: Politics and International Relations—a core text in understanding the threshold standards for a degree in the field. Using Daubney’s (Citation2022) KASE framework, the use of the Subject Benchmark Statement as a shared understanding of a degree in the field, allows for a wide breadth of view to propose one articulation of the employability value of studying Politics and International Relations as an undergraduate student. This article has proposed that this student-facing statement, articulating the employability value of a degree in the field, is utilized during programme delivery (in the classroom and virtual learning environments) and promotion (e.g. during student recruitment events to potential Politics and International Relations students). Such repeated utilization has the capacity for helping students learn and recall the employability value of their degree, while also not making significant demands on staff workloads or marking a significant deviation from current curricula.

The SoTL literature reviewed in this article identified a lack in a clear common understanding of the employability value of a degree in Politics and International Relations. This is something that scholars working in the field will need to address to ensure that the subject remains a compelling choice for undergraduate students. While this article has been on the experience in the UK, the conclusions are ones that are unlikely to be unique to that case. The field of Politics and International Relations could benefit from those that lead teaching and learning being more willing to confidently state the employability value of that education—while also being conscious of potential resistances to inserting too much focus on employability into already packed curricula. Therefore, a focus on the benefits of extracted employability over the onerous alternative of added employability is likely to be a fruitful path. Doing so through utilizing digestible, reusable, and repeat-worthy student-facing statements of the innate employability value of a degree means that academics do not have to add to already heavy workloads nor heighten the risk of discouraging students and colleagues from engaging with the employability agenda by seeming to do “too much”. This confident stating of their degree’s value—without necessarily directing graduates to specific career paths—could have the benefit of ensuring Politics and International Relations students will be able to excel and adapt within the demands of the contemporary employment market and the world of work.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Jeremy F. G. Moulton

Dr. Jeremy F. G. Moulton is a Lecturer at the University of York’s Department of Politics and International Relations and is a Senior Fellow of the Higher Education Academy. His teaching and research focus on environmental and European Union politics, as well as the scholarship of teaching and learning.

Notes

1 The full classification ‘Politics and International Relations’ is used here for two core reasons. Firstly, the QAA Subject Benchmark Statement (which is a core part of this article’s analysis and proposal) classifies the field thusly. Secondly, it is increasingly common for academic departments in the UK to brand themselves as Politics and International Relations departments. Scholarship and provision might also refer to the field as ‘Political Science’, ‘Political Studies’, or simply as ‘Politics’ and, separately, ‘International Relations’, to give only a few examples (e.g. QAA Citation2023, 3–4).

References

- AdvanceHE. 2019. “Embedding Employability in Higher Education.” Accessed 23 November 2022. https://www.advance-he.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2020-05/Embedding%20Employability%20in%20Higher%20Education%20Framework.pdf?_cldee=DBBB6vKCHKauK4FbdwEXICL3qLmu942L1dCUqzNz2lC4Q5wLjWMqx-xfdGYzL3Am&recipientid=lead-b609b8b5126ced1181ac0022481b584d-9be72e98ca5546c7a3dde68a24288ad3&utm_source=ClickDimensions&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=Consultancy%20-%20Employability&esid=fc999a5e-47f9-481c-8ab8-fea82b715c23.

- Barrow, John, Tracey Innes, and Kate Robertson. 2023. “Transforming and Embedding Graduate Attributes and Skills at the University of Aberdeen.” QAA. 16 May 2023. Accessed 14 August 2023. https://www.membershipresources.qaa.ac.uk/docs/membership-resources/teaching-learning-and-assessment/case-study-transforming-and-embedding-graduate-attributes-and-skills.pdf.

- Blair, Alasdair. 2015. “Similar or Different?: A Comparative Analysis of Higher Education Research in Political Science and International Relations between the United States of America and the United Kingdom.” Journal of Political Science Education 11 (2):174–189. doi:10.1080/15512169.2015.1016037.

- Bozward, David, Matthew Rogers-Draycott, Kelly Smith, Mokuba Mave, Vic Curtis, Chinthaka Aluthgama-Baduge, Rob Moon, and Nigel Adams. 2023. “Exploring the Outcomes of Enterprise and Entrepreneurship Education in UK HEIs: An Excellence Framework Perspective.” Industry and Higher Education 37 (3):345–358. doi:10.1177/09504222221121298.

- Breuning, Marijke, Paul Parker, and John Ishiyama. 2001. “The Last Laugh: Skill Building through a Liberal Arts Political Science Curriculum.” Political Science & Politics 34 (03):657–661. doi:10.1017/S1049096501001056.

- Broms, Rasmus, and Jenny de Fine Licht. 2019. “Preparing Political Science Students for a Non-Academic Career: Experiences from a Novel Course Module.” Politics 39 (4):514–526. doi:10.1177/0263395719828651.

- Calma, Angelito, and Camille Dickson-Deane. 2020. “The Student as Customer and Quality in Higher Education.” International Journal of Educational Management 34 (8):1221–1235. doi:10.1108/IJEM-03-2019-0093.

- Chaturvedi, Neilan S., and Mario A. Guerrero. 2022. “Career Preparation and Faculty Advising: How Faculty Advising Can Improve Student Outcomes and Prepare Them for Life after Graduation.” Journal of Political Science Education 19(1):34–47. doi:10.1080/15512169.2022.2107536.

- Craig, John. 2010. “Practitioner-Focused Degrees in Politics.” Journal of Political Science Education 6(4):391–404. doi:10.1080/15512169.2010.518086.

- Craig, John. 2015. “Teaching Politics to Practitioners.” In Handbook on Teaching and Learning in Political Science and International Relations, eds. John Ishiyama, William J. Miller, Eszter Simon. Vancouver: Edward Elgar, 28–34.

- Craig, John. 2019. “The Emergence of Politics as a Taught Discipline at Universities in the United Kingdom.” The British Journal of Politics and International Relations 22 (2):145–163. doi:10.1177/1369148119873081.

- Daubney, Kate. 2022. “Teaching Employability is Not my Job!: Redefining Embedded Employability from within the Higher Education Curriculum.” Higher Education, Skills and Work-Based Learning 12 (1):92–106. doi:10.1108/HESWBL-07-2020-0165.

- Ferrie, Jo, and Thees Spreckelsen. 2023. “Teaching Methods: Pedagogical Challenges in Moving beyond Traditionally Separate Quantitative and Qualitative Classrooms.” Open Scholarship of Teaching and Learning 2 (2):64. doi:10.56230/osotl.64.

- Graham, Andrew T. 2015. “Academic Staff Performance and Workload in Higher Education in the UK: The Conceptual Dichotomy.” Journal of Further and Higher Education 39 (5):665–679. doi:10.1080/0309877X.2014.971110.

- Hamann, Kerstin, Philip H. Pollock, and Bruce M. Wilson. 2009. “Who SoTLs Where? Publishing the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning in Political Science.” Political Science & Politics 42 (4):729–735. doi:10.1017/S1049096509990126.

- Hannon, Paul D. 2005. “Philosophies of Enterprise and Entrepreneurship Education and Challenges for Higher Education in the UK.” The International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation 6 (2):105–114. doi:10.5367/0000000053966876.

- Harding, Lauren Howard. 2023. “Supporting Diverse Learning Styles: A Case Study in Student Led Syllabus Design.” Journal of Political Science Education 19 (1):83–90. doi:10.1080/15512169.2022.2117626.

- Harrison, Lisa. 2012. “Can Politics be Benchmarked?” In Teaching Politics and International Relations, eds. C. Gormley-Heenan and S. Lightfoot, 38–50. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Harvey, L. 2001. “Defining and Measuring Employability.” Quality in Higher Education 7(2):97–109. doi:10.1080/13538320120059990.

- Hayton, R. 2008. “Teaching Politics: Graduate Students as Tutors.” Politics 28 (3):207–214. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9256.2008.00323.x.

- HESA. 2022. “What do HE Students Study?” February 10 2022. Accessed 23 November 2022. https://www.hesa.ac.uk/data-and-analysis/students/what-study.

- Institute of Student Employers. 2020. Student Development Survey 2020. London: Institute for Student Employers.

- Institute of Student Employers. 2022. Student Development Survey 2022. London: Institute for Student Employers.

- Ishiyama, John, Maijke Breuning, and Linda Lopez. 2006. “A Century of Continuity and (Little) Change in the Undergraduate Political Science Curriculum.” American Political Science Review 100 (04):659–665. doi:10.1017/S0003055406062551.

- Knight, Peter, and ESECT Colleagues. 2003. “Briefings on Employability 3: The Contribution of Learning, Teaching and Assessment and Other Curriculum Projects to Student Employability.” ESECT. https://www.qualityresearchinternational.com/esecttools/esectpubs/knightlearning3.pdf.

- Lee, Donna, Emma Foster, and Holly Snaith. 2016. “Implementing the Employability Agenda: A Critical Review of Curriculum Developments in Political Science and International Relations in English Universities.” Politics 36 (1):95–111. doi:10.1111/1467-9256.12061.

- Lightfoot, Simon. 2015. “Promoting Employability and Jobs Skills via the Political Science Curriculum.” In Handbook on Teaching and Learning in Political Science and International Relations, eds. John Ishiyama, William J. Miller, Eszter Simon. Vancouver: Edward Elgar, 144–154.

- Lucas, Kevin Edward. 2023. “Internships for Credit: Linking Work Experience to Political Science Learning Objectives.” Journal of Political Science Education 2023:1–11. doi:10.1080/15512169.2023.2219398.

- Marineau, Josiah Franklin. 2020. “What is the Point of a Political Science Degree?” Journal of Political Science Education 16 (1):101–107. doi:10.1080/15512169.2019.1612756.

- Maurer, Heidi, and Jocelyn Mawdsley. 2014. “Students Skills, Employability and the Teaching of European Studies: Challenges and Opportunities.” European Political Science 13(1):32–42. doi:10.1057/eps.2013.34.

- Norton, Stuart. 2019. “The Trouble with Employability.” AdvanceHE. 6 November 2019. Accessed 14 August 2023. https://www.advance-he.ac.uk/news-and-views/trouble-employability-enterprise-employability.

- Pal, Maïa. 2022. “Employability as Exploitability: A Marxist Critical Pedagogy.” In Rethinking Neoliberalism: Alternative Societies, Transition, and Resistance, eds. Neal Harris and Onur Acaroğlu. Cham: Springer, 197–220.

- Prospects. 2021. “Politics”. March 2021. Accessed 23 November 2022. https://www.prospects.ac.uk/careers-advice/what-can-i-do-with-my-degree/politics.

- QAA. 2012. Enterprise and Entrepreneurship Education. Guidance for UK Higher Education Providers. Gloucester: QAA.

- QAA. 2018. “Enterprise and Entrepreneurship Education. Guidance for UK Higher Education Providers. Gloucester: QAA.

- QAA. 2019. “Subject Benchmark Statement: Politics and International Relations: Fourth Edition” QAA. December 2019. https://www.qaa.ac.uk/docs/qaa/subject-benchmark-statements/subject-benchmark-statement-politics-and-international-relations.pdf?sfvrsn=73e2cb81_5.

- QAA. 2023. “Subject Benchmark Statement: Politics and International Relations: Fifth Edition” QAA. March 2023. https://www.qaa.ac.uk/the-quality-code/subject-benchmark-statements/subject-benchmark-statement-politics-and-international-relations#.

- Robinson, Andrew M. 2013. “The Workplace Relevance of the Liberal Arts Politics Science BA and How It Might Be Enhanced: Reflections on an Exploratory Survey on the NGO Sector.” Political Science & Politics 46 (1):147–153.

- The Guardian. 2022. “Rishi Sunak Vows to End Low-Earning Degrees in Post-16 Education Shake-Up”. August 7 2022. Accessed 23 November 2022. https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2022/aug/07/rishi-sunak-vows-to-end-low-earning-degrees-in-post-16-education-shake-up.

- Thijssen, Johannes G. L., Beatrice I. J. M. Van der Heijden, and Tonette S. Rocco. 2008. “Toward the Employability – Link Model: Current Employment Transition to Future Employment Perspectives.” Human Resource Development Review 7 (2):165–183. doi:10.1177/1534484308314955.

- Tymon, Alex. 2013. “The Student Perspective on Employability.” Studies in Higher Education 38 (6):841–856. doi:10.1080/03075079.2011.604408.

- Williams, Gareth. 2010. “Subject Benchmarking in the UK.” In Public Policy for Academic Quality: Higher Education Dynamics 30, eds. David D. Dill and Maarja Beerkens. Dordrecht: Springer, 157–182.

- Williams, Stella, Lorna J. Dodd, Catherine Steele, and Raymond Randall. 2016. “A Systematic Review of Current Understandings of Employability.” Journal of Education and Work 29(8):877–901. doi:10.1080/13639080.2015.1102210.

- Wyman, Matthew, Jennifer Lees-Marshment, and Jon Herbet. 2012. “From politics past to politics future: Addressing the employability agenda through a professional politics curriculum.” In Teaching Politics and International Relations, eds. C. Gormley-Heenan and S. Lightfoot. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 236–254.