Abstract

Background

This study aims to investigate decidual vasculopathy in preeclampsia at term and its relationship to spiral artery remodeling at implantation sites. Study design: Implantations sites with endovascular trophoblasts were reviewed from abortions with immunostaining for CD56. Placentas from patients with preeclampsia were also reviewed in association with other pathological features using placentas with decidual vasculopathy but not preeclampsia as controls. Results: Endovascular trophoblasts were phenotypically switched to express CD56 upon entering the spiral artery at implantation. CD56 expression is identified in classic decidual vasculopathy at term with or without preeclampsia. CD56 expression in addition to cytokeratin in decidual vasculopathy demonstrated the fetal trophoblastic origin, establishing the presence of endovascular trophoblasts at implantation and the decidual vasculopathy at term. Conclusion: Decidual vasculopathy at term contains the same CD56 positive extravillous endovascular trophoblasts seen with spiral artery remodeling in early pregnancy. CD56 may serve as a possible marker for decidual vasculopathy in the later stages of pregnancy.

Introduction

Decidual (maternal) vasculopathy is commonly associated with pregnancy induced hypertension (PIH) or preeclampsia. There are three types of decidual vasculopathy that are clinically recognized, namely acute atherosis, fibrinoid medial necrosis and mural arterial hypertrophy [Citation1]. These types of vasculopathy are present in approximately 20–50% placentas from preeclampsia [Citation1, Citation2]. Two separate issues are commonly seen: on the one hand, no specific morphological features of decidual vessels are identified in the remaining 50–80% preeclamptic placentas with clinical hypertensive manifestations [Citation3, Citation4]; on the other hand, there are morphological features of vasculopathy in normotensive patients with other pregnancy associated complications such as gestational diabetes, intervillous thrombosis, placenta infarcts, fetal meconium passage and aspiration, and occasionally normal-term pregnancy without identifiable complications. How the vasculopathy occurs in preeclampsia and how to bridge these gaps in understanding the disease process remain poorly understood. Traditionally, acute atherosis is characterized by the presence of foamy “macrophages” (cholesterol/lipid laden macrophages) within the intima of the maternal spiral artery in similar fashion to aortic atherosclerosis. These foamy macrophages also phenotypically express CD68 [5–10]. Fibrinoid medial necrosis is characterized by the fibrin-like eosinophilic hyalinized material within the maternal vascular walls immunohistochemically reactive to immunoglobulins and complements [Citation5–10]. Mural arterial hypertrophy is defined as the thickened decidual arteries similar to those in other tissue without trophoblastic remodeling and this type of vasculopathy is known to be more commonly associated with chronic hypertension [Citation11, Citation12]. Through extensive laboratory and animal studies, preeclampsia is thought to be caused by poor cytotrophoblastic remodeling of the spiral artery in early implantation and subsequently poor angiogenesis in placental vascular development [Citation13–16]. Decidual vasculopathy in preeclampsia at term was first found incidentally to be associated with CD56 expression of cellular components in the vascular wall, and the expression of CD56 on endovascular trophoblasts at the implantation site in early pregnancy has been previously reported [Citation17, Citation18]. The presence of CD56 expression in decidual vasculopathy raised the question of cellular origin of these “foamy” cells which were traditionally considered “macrophages/leukocytes” [Citation19]. CD56 is a defining marker for the natural killer (NK) cells within the decidua and circulation which play important roles in implantation and spiral artery remodeling in early pregnancy. CD56 is a glycoprotein first discovered in neuron, glial and neural tissues (neural cell adhesion molecule, NCAM). CD56 is also expressed in the inner cell mass of early embryonic development [Citation20]. In hematopoietic cells, CD56 marks the NK cell lineage and minor percentage of T cells, and aberrant expression of CD56 can be found in multiple myeloma cells and acute myeloid leukemia [Citation21]. In the current study, the histologic features seen with spiral artery remodeling in early pregnancy are compared to those abnormal changes found in decidual vasculopathy at term with or without an association with preeclampsia.

Materials and methods

The present study is exempt from Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval according to section 46.101(b) of 45CFR 46 which states that research involving the study of existing pathological and diagnostic specimens in such a manner that subjects cannot be identified is exempt from the Department of Health and Human Services Protection of Human Research Subjects. Implantation sites in early pregnancy up to 12 weeks (specimens submitted as “product of conception” (POC) including missed abortion, incomplete abortion, spontaneous abortion, and most specimens were from curettage without intact fetal tissues or embryonic sac), placentas with clinical diagnosis of preeclampsia, and placentas submitted for pathology examination for other pregnancy complications but no indication of preeclampsia were examined for decidual vascular changes with immunohistochemical staining for CD56, CD68, GATA3 and cytokeratin (AE1/AE3). Pathologic changes, placental measurements, the associated clinical information and diagnoses were recorded in pathology reports at the time of clinical examination. Implantation site is characterized by the presence of extravillous interstitial trophoblasts within the decidua associated with the endovascular trophoblasts. Placentas from normal pregnancies without clinical or pathological indications are not submitted for pathology examination in our institution.

Paraffin embedded tissues from routine surgical pathology specimens and routine hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stained pathology slides were examined using light microscopy using the Amsterdam criteria [Citation22]. No special procedures were employed. Implantation sites and maternal vasculopathy such as acute atherosis and fibrinoid medial necrosis in preeclampsia or unknown clinical conditions were identified during the routine clinical service, and subsequently examined by immunostaining for CD56 expression.

Immunohistochemical staining procedures were performed on paraffin embedded tissues using Leica Biosystems Bond III automated immunostaining system following the manufacturing instruction. CD56 monoclonal antibody was purchased for clinical in vitro diagnostics from Agilent DAKO (mouse monoclonal antibody against human, Cat. # M730401-2) with appropriate dilutions and controls. AE1/AE3 and CD68 monoclonal antibodies were from Agilent DAKO under catalog numbers M351501-2 and M081401-2 (Agilent DAKO, CA). GATA3 monoclonal antibody was from Leica Bioscience under the catalog number PA0798.

The data from 451 placentas of patients with clinical history of preeclampsia (PIH) and 583 placentas of patients with vasculopathy but non-hypertensive complications (non-PIH) were extracted from the records with associated pathologic findings without the patients’ identifiers. The vasculopathy was divided into four groups: classic type including acute atherosis and fibrinoid medial necrosis (Classic type), mural arterial hypertrophy (Mural hypertrophy), mixed type with combination of classic type and mural hypertrophy (Mixed type), and preeclampsia (PIH) without vasculopathy (no vasculopathy). The data was examined statistically and plotted using various R statistics programs (http://statistics4everyone.blogspot.com/). Baseline characteristics table is a program from the R statistics package available from the above website. All the tables () were generated by using the Baseline characteristics table program. Placental weight and various types of decidual vasculopathy were plotted by using dot plot program of the R-statistics package. Correlation of placental weight and gestational age of various types of decidual vasculopathy was plotted by using conditioning plot program of the R-package.

Table 1. Baseline characters table for 451 preeclamptic placentas (PIH) with different types of vasculopathy and associated pathologic findings. The baseline character table with p value calculation is generated by using the R-statistics program as described. C: C-section delivery; V: Vaginal delivery; cHTN: chronic hypertension; MFI: maternal floor infarction; Cord issues include marginal or velamentous insertions, 2 vessel cord, true knots, Others include oligohydramnios, polyhydramnios, placental previa, placental increta/percreta, bilobed placentas, fetal anomalies, chromosomal abnormalities, maternal history of IBDs, lupus, thyroid diseases, cholestasis and cancers.

Table 2. Baseline characters table for 583 placentas from non-preeclampsia patients with different types of vasculopathy and associated pathologic findings. The baseline character table with p value calculation is generated by using the R-statistics program as described.

Table 3. Baseline characters table for 877 placentas with vasculopathy associated with or without preeclampsia. The baseline character table with p value calculation is generated by using the R-statistics program as described.

Table 4. Placental weight associated with vasculopathy and other pathologic features to assess the effect of individual pathologic features on placental weight development. All placentas with vasculopathy are included (n = 877), and placentas associated with preeclampsia but not vasculopathy are excluded (n = 157).

Results

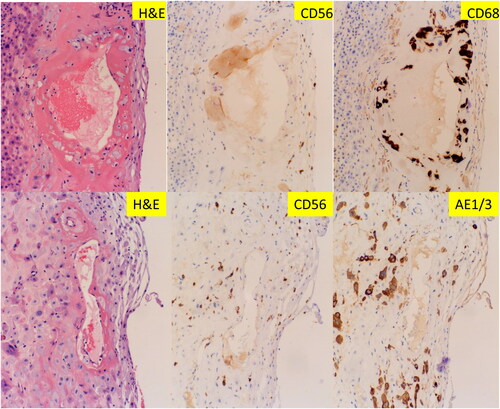

Trophoblastic expression of CD56 in spiral artery at implantation sites

We reviewed 104 implantation sites from the routine pathology practice. Trophoblastic remodeling of the maternal spiral arteries can be easily identified in the background of decidua with extravillous trophoblasts. The vascular walls within the implantation sites show various degrees of fibrinoid medial necrosis, a typical morphological feature of decidual vasculopathy in preeclampsia (). The morphologic features of acute atherosis are also seen occasionally, but much less common than those of fibrinoid medial necrosis. Mural arterial hypertrophy of decidual vessels is commonly present in the implantation sites but its clinical significance is uncertain given the early stages of morphologic changes in the decidua and implantation site. It remains possible that the spiral artery remodeling by trophoblasts is yet to happen to these decidual vessels with mural hypertrophy in early implantation. There are scattered lymphocytes within the decidua tissue. Immunohistochemical staining for CD56 expression showed strong membrane/cytoplasmic staining signals only on the endovascular trophoblasts, but not on extravillous trophoblasts in the decidua (). These endovascular trophoblasts are also reactive to AE1/AE3 and GATA3 (see ), indicating the fetal trophoblastic origin. These endovascular trophoblasts are also weakly reactive to CD68, a common macrophage/monocyte/histiocyte marker. The lymphocytes within the decidua are positive for CD56 expression, consistent with the uterine natural killer (NK) cells as expected since CD56 is a defining marker for uterine NK cells. The extravillous trophoblasts within the decidua outside vessels are reactive to both AE1/AE3, GATA3 and weakly to CD68, but not to CD56. Immunostaining for CD56 expression was performed for 30 consecutive cases (implantation sites), and 100% of the endovascular (intraluminal) trophoblasts were stained positive. CD56 expression on endovascular trophoblasts and embryonic tissue have been previously reported [Citation17, Citation18].

Figure 1. Morphologic features of maternal spiral artery remodeling in early implantation site with immunohistochemical staining for CD56, pancytokeratin (AE1/AE3) and CD68 expression. (A) Implantation site of early missed abortion with hematoxylin & eosin (H&E) stain. (B–D) The same section of implantation site as panel A with CD56, AE1/AE3 and CD68 immunostaining. (A–D at 400× magnification). Arrow indicates weak CD68 reactivity.

Figure 2. Morphologic features of classic decidual vasculopathy of preeclamptic placentas from the decidua basalis with immunohistochemical staining for CD56, AE1/AE3 and CD68 expressions. (A) Classic decidual vasculopathy with acute atherosis and fibrinoid medial necrosis by hematoxylin & eosin (H&E) stain. The same section of placenta as in H&E panel with CD56, AE1/AE3 and CD68 immunostaining. (All at 400× magnification). Arrows indicate positive reactivity to individual markers. (B) Decidual vasculopathy with immunostaining for CD56 and GATA3. Partial involvement of spiral artery wall by fibrinoid medial necrosis and acute atherosis in panel H&E stain. Adjacent space is an endometrial gland. The same vasculopathy as in H&E panel with immunostaining for CD56 and GATA3 (nuclear signal). All at 200× magnification.

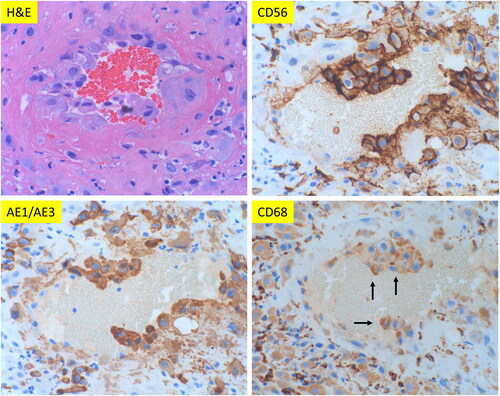

Trophoblastic expression of CD56 in decidual vasculopathy in preeclampsia

We have examined 451 placentas from patients with clinical diagnosis of preeclampsia using the additional knowledge of phenotypic switch of endovascular trophoblasts with CD56 expression above and utility of CD56 immunostaining. The morphological features of decidual vasculopathy and the corresponding immunostaining for CD56, AE1/AE3 and CD68 expression are shown in . The endovascular trophoblasts are again immunohistochemically strongly reactive to CD56. These endovascular trophoblasts are also positive for AE1/AE3 and weakly positive for CD68. The presence of AE1/AE3 expression on these endovascular cells indicates the fetal trophoblastic cell origin, rather than maternal macrophages/leukocytes/phagocytes. This is in contrast to the traditional view of acute atherosis being similar to atherosclerosis with foamy macrophages [Citation6, Citation8]. The fetal trophoblastic cell origin is further confirmed by the expression of GATA3 in . The presence of weakly CD68 expression on these intravascular trophoblasts, in addition to CD56 expression, may have other unknown implications, as weakly CD68 expression is found in all syncytiotrophoblasts of the entire term placenta (data not shown). However, CD56 expression is not identified on the extravillous interstitial trophoblasts outside the vessels or syncytiotrophoblasts.

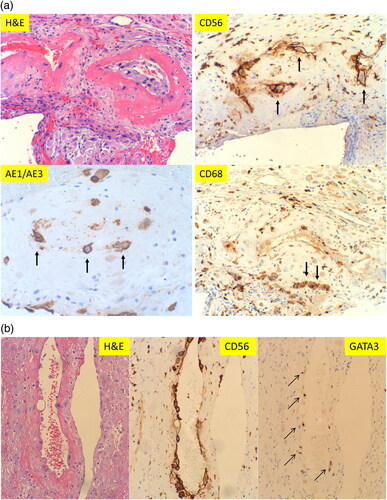

Vasculopathy in decidua basalis versus decidua capsularis (decidua vera)

CD56 expression on the vasculopathy present in the membrane roll was examined, in addition to immunostaining for CD68 and pancytokeratin (AE1/AE3) (). The endovascular cells within the decidua capsularis (membrane roll) are negative for CD56 and AE1/AE3 but strongly positive for CD68, indicating the macrophage cell origin. This is consistent with the traditional view that the endovascular cells within the decidual vasculopathy are inflammatory cells (leukocytes/macrophages), in contrast to the endovascular trophoblasts with CD56 expression described above at the decidua basalis. It appears that the mechanisms of vasculopathy development in decidua basalis are different from that in decidua capsularis, although the morphologic features of vasculopathy in both locations are identical.

Decidual vasculopathy in placentas of preeclampsia

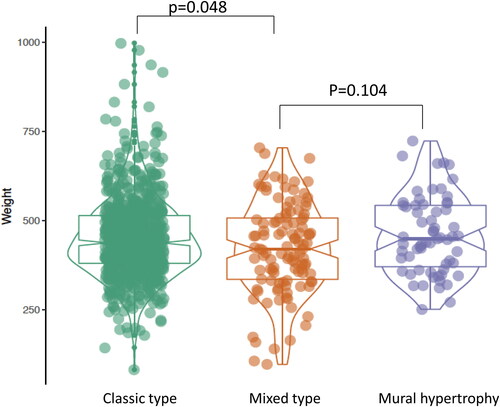

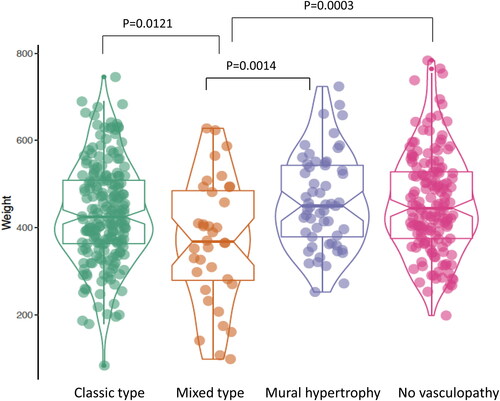

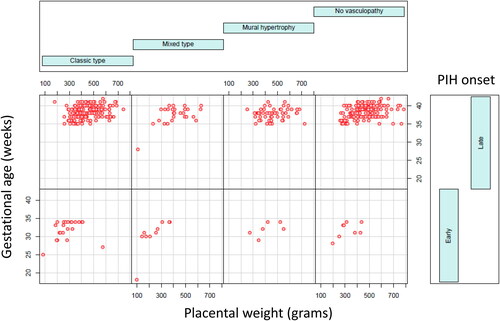

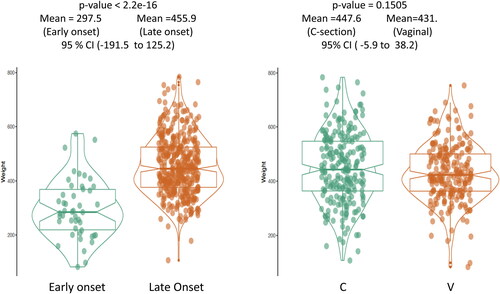

The clinical features of the 451 preeclamptic placentas are summarized in the baseline characteristics table () based on the types of decidual vasculopathy and clinical/pathological characteristics. The common placental pathologic features associated with abnormal pregnancies are listed as presence (1) and absence (0). Preeclampsia is also divided by early onset and late onset types. Notably the gestational age (delivery age) (early or late onset), placental weight, chronic hypertension, chronic villitis and intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) are statistically significant in association with decidual vasculopathy identified above (p < 0.05). Mixed type vasculopathy is found to be associated with low placental weight, early onset preeclampsia, IUGR and chronic hypertension ( and ), whereas chronic villitis is associated with no vasculopathy in preeclampsia population. Correlation between the placental weight, gestational age, various types of decidual vasculopathy, and early onset and late onset preeclampsia was demonstrated using conditioning plot method (). Early onset preeclampsia is associated with lower placental weight, and this is at least in part due to shortened gestational age (, left panel). The frequency of all types of decidual vasculopathy in preeclampsia is 65.2%.

Figure 4. Placental weight comparisons between the four types of vasculopathy: Classic type (including acute atherosis and fibrinoid medial necrosis) (n = 198), mural hypertrophy (n = 59), mixed type (mixed classic type and mural hypertrophy) (n = 37) and no vasculopathy (n = 157) in placentas from preeclampsia (PIH). P-value was calculated by using the ANOVA test in R-statistics program.

Figure 5. Correlation in aggregates of placental weight, gestational age and various types of decidual vasculopathy in patients with preeclampsia including early onset and late onset preeclampsia using conditioning plot (R-statistics package). Classic type n = 198, mural hypertrophy n = 59, mixed type n = 37, no vasculopathy n = 157. Details of specific type of vasculopathy and placental weight correlation is shown in the subsequent figures and tables.

Figure 6. Placental weight comparison from patients with early onset preeclampsia (n = 60) versus late onset preeclampsia (n = 391) (left panel) and C-section delivery (n = 227) versus vaginal delivery (n = 224) (right panel). Early onset preeclampsia (n = 60) represents 13.3% of total preeclampsia in current study. The baseline characters are listed in .

Immunostains for CD56 were performed for 39 cases, and 37 cases showed demonstrable immunoreactivity to CD56. The CD56 expression was found in the cellular elements within the vascular wall and the vascular lumen as shown (). Two negative cases for CD56 immunostaining were due to the disappearance of the decidual vessels on the immunostaining slides and the deeper sections.

Decidual vasculopathy without preeclampsia

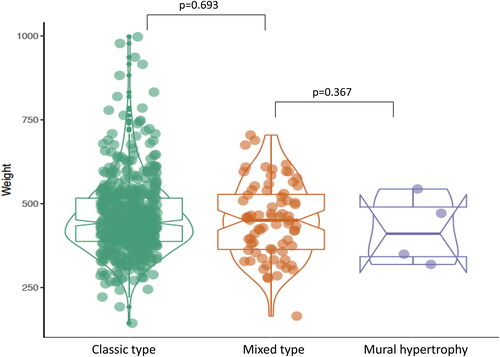

The 583 placentas with decidual vasculopathy and other pregnancy related complications are summarized in the baseline character table (), and these patients did not have clinical diagnosis of preeclampsia or hypertension. The morphological features of decidual vasculopathy were identical to those seen in . There is no statistically significant association among the vasculopathy type, clinical features and pathological features within this population except for acute chorioamnionitis which appears less frequently in placentas with mixed-type vasculopathy ().

Figure 7. Placental weight comparison from patients with vasculopathy but no preeclampsia (PIH) or hypertensive disorders. The baseline characters are listed in . Classic type vasculopathy n = 504, Mixed type vasculopathy n = 75, mural hypertrophy n = 4.

Immunostaining for CD56 expression was performed on 28 cases with identifiable decidual vasculopathy and all endovascular trophoblasts of the 28 cases were positive for CD56 reactivity.

Vasculopathy and clinical/pathologic features

In combination, there are 877 placentas with decidual vasculopathy identified in the current study with or without preeclampsia. The baseline characteristics table showed significant associations between the clinical/pathological features and the types of vasculopathy (). Notably mixed-type vasculopathy is associated with early onset preeclampsia, early delivery and IUGR. It is also associated with lower placental weight (). Mural hypertrophy appears associated with more C-section delivery and chronic hypertension. In the presence of vasculopathy, each individual pathologic feature is associated with significant changes of placental weight (), and these changes of placental weight are largely consistent with traditional views and other studies.

Discussion

Preeclampsia is a spectrum of clinical manifestations with various degrees of severity, and its placental manifestations are diverse. Decidual vasculopathy is known for many decades one of the defining features of preeclamptic placentas [Citation1, Citation19, Citation23]. In severe preeclampsia which represents approximately 5–20% of all preeclamptic patients, the placental villous tissue is hypoplastic and commonly associated with decidual vasculopathy, placental infarcts and thrombosis [Citation24]. In these cases, the pathological changes of the placentas are easily identified during routine placental examination. More commonly seen are mild forms of preeclampsia with borderline normal placentas and normal villous tissue development. In this mild form of preeclamptic cases, the placental pathological changes are harder to define, and decidual vasculopathy is difficult to identify [Citation22, Citation24]. Our previous survey indicated a relatively low percentage of placentas from the preeclamptic patients showed the presence of decidual vasculopathy [Citation4, Citation22]. Other studies have shown similar results [Citation1, Citation25]. In this setting, CD56 immunostaining can be used as an adjunct marker for identifying the endovascular (intraluminal) trophoblasts, and decidual vasculopathy. The spectrum of decidual vasculopathy from partial to complete acute atherosis or fibrinoid medial necrosis can be defined by the immunostaining for CD56 expression. Practically these decidual vascular lesions in preeclampsia are probably better designated as “CD56 related vasculopathy”, in comparison to another vascular lesion defined as “mural arterial hypertrophy”. In addition, the term “CD56 related vasculopathy” appears to unify the spectrum of morphologic changes in decidual vasculopathy with the implication of pathogenesis. Mural arterial hypertrophy is associated with significant pregnancy related complications [Citation11], and it represents failure of trophoblastic invasion of the spiral artery in implantation [Citation24]. In light of CD56 expression of endovascular trophoblasts in classic decidual vasculopathy in this study, mural arterial hypertrophy seems to be a separate but important vascular entity with different pathogenic mechanisms. Interestingly, CD56 expression is only found on endovascular trophoblasts and the scattered decidual NK cells. No other cell type in the implantation site or term placenta is found to be immunoreactive to CD56 expression. Traditionally acute atherosis and fibrinoid medial necrosis are related morphologic changes characterized by the endothelial cell damage, immunoglobulins/complements deposits, fat/cholesterol deposits and macrophage phagocytosis [Citation5–7, Citation10, Citation26]. Our current results demonstrated that these “macrophages” are phenotypically fetal trophoblasts in origin by immunostaining pattern for cytokeratin (AE1/AE3) expression. These “macrophages” in the vessels are also immunoreactive to CD56 expression and weakly reactive to CD68 expression. Identification of these “foamy macrophages” as fetal trophoblasts with expression of CD56, a defining NK cells marker, points to an entirely different direction for the pathogenesis of preeclampsia. CD56 expression is present on all endovascular trophoblasts in all implantation sites indicating the dynamic changes of CD56 expression and endovascular trophoblasts during normal pregnancy. Consequently, persistence of endovascular trophoblasts with CD56 expression during late gestations is associated with pregnancy related complications. This is in contrast to the traditional view of the lack of spiral artery remodeling by the trophoblasts as a basis of preeclampsia [Citation13–16]. We have seen CD56 expression on endovascular trophoblasts in placentas of up to 24 week gestation from early premature delivery due to chorioamnionitis without evidence of decidual vascular insufficiency (maternal vascular malperfusion). The mechanism by which CD56 expression disappears in temporal fashion from early to late gestations requires further laboratory studies.

Spiral artery remodeling occurs in the decidua basalis at the implantation site, and the decidua capsularis is formed when the endometrial epithelium and stromal tissue is fused and pushed to the uterine wall. Decidua capsularis (decidua vera), chorion and amnion membranes are delivered at term as fetal membrane tissue. Routine pathology examination of placenta requires a section of fetal membrane roll consisting of decidua capsularis. No significant spiral artery invasion by trophoblasts occurs within the decidua capsularis. Our previous study and others emphasized the presence of vasculopathy within the membrane roll [Citation4, Citation27]. Two physiologic processes of spiral artery remodeling in early pregnancy have been previously reported [Citation28]; namely trophoblastic dependent remodeling with direct cellular interaction with extravillous cytotrophoblasts in the decidua basalis where embryonic implantation occurs, and the trophoblastic independent remodeling in which there is no cellular interaction between the extravillous cytotrophoblasts and the cellular components of maternal vessels [Citation28, Citation29]. The trophoblastic independent spiral artery remodeling has been convincingly demonstrated in ectopic pregnancies previously [Citation29], and the vasculopathy seen at the decidua capsularis (vera) in the current study is likely trophoblastic independent in contrast to those seen at the decidua basalis described above. Only the trophoblastic-dependent spiral artery remodeling appears associated with phenotypic switch of endovascular trophoblasts. This may be the first detailed study to describe the similarities of the physiologic process of spiral artery remodeling to the histopathologic changes encountered in decidual vasculopathy at term. It is worth noting that the specimens of spiral artery remodeling in current study were mostly from curettage and it remains likely that these specimens were abnormal, although the implantation sites can be easily identified and CD56 expression demonstrated by using immunohistochemical staining.

Practically for histopathology examination of the placenta, it is important to note that the blood vessels with endovascular trophoblasts within the decidua basalis may or may not show complete fibrinoid medial necrosis or atherosis of the entire vessel wall. When fibrinoid medial necrosis replaces the entire walls of the vessels, no cellular components and no immunoreactive cells are to be found by immunostaining. It is this partial replacement of the vascular wall with the residual cellular components that can be identified by the morphologic assessment and immunostaining for CD56 expression. This type of partial fibrinoid medial necrosis of the vascular wall with endovascular cell components have not been previously appreciated and recognized as a type of decidual vasculopathy [Citation22]. It is also important to note that the endovascular trophoblasts in preeclampsia were greatly reduced in number in comparison to those in the implantation sites (), and the placentas from the normal term pregnancy show no evidence of endovascular trophoblasts or typical vasculopathy (atherosis and fibrinoid medial necrosis) [Citation25].

In light of immunostaining results and knowledge of CD56 expression in decidual vasculopathy, there are still 34.8% preeclamptic placentas without identifiable decidual vasculopathy in the current study. These preeclamptic placentas contain significant pathologic lesions such as infarcts, intervillous thrombosis and other findings similar to those identified in placentas with decidual vasculopathy. One of the possibilities may be related to the placental sampling, since the routine placental examination requires three sections of placental tissue including maternal and fetal surfaces plus one membrane roll containing the decidua capsularis, as recommended by international guidelines [Citation22]. Sectioning of the decidua basalis/interface using Khong’s method (horizontal decidual section) shows better visualization of decidual vessels [Citation30, Citation31]. Decidual vascular changes and classic vasculopathy are best appreciated on the decidua basalis (basal plate), and additional sampling in the basal plate may increase the yield of decidual vasculopathy.

Maternal spiral artery remodeling by the extravillous trophoblasts is critical for establishment of embryonic implantation in the endometrium [Citation32]. The expression of CD56 exclusively on the endovascular (intraluminal) trophoblasts, but not on the decidual extravillous trophoblasts suggests a dynamic interaction between the fetal trophoblasts and the maternal uterine NK cells upon invasion into the vascular wall. The maternal uterine NK cells can regulate the trophoblastic remodeling of maternal spiral artery by an unclear mechanism [Citation33–35], and direct acquisition of maternal NK cell marker CD56 by the fetal trophoblasts through direct cell-to-cell interaction seems to help explain the direct interaction between the maternal and fetal components, and such a mechanism has been previously described for other cell types [Citation36]. De novo expression of CD56 within the endovascular trophoblasts through transcription and translation also remains a possibility [Citation37, Citation38]. Curiously, CD56 expression is found in the myometrium of unclear significance (data not shown). The role of the uterine NK cells in implantation is likely to be a provider of the maternal CD56 to the endovascular (intraluminal) trophoblasts, in addition to autocrine and paracrine functions providing cytokines and secreting factors to the fetal development. Direct acquisition of maternal CD56 expression by the endovascular trophoblasts may have significance to suppress the maternal immune system or to induce maternal immune tolerance since invasion of trophoblasts into the maternal spiral artery is the initial exposure of the fetal cells to the maternal circulation [Citation37, Citation39]. The mechanism of the interaction between the fetal trophoblasts and the maternal NK cells should be further explored experimentally using in vitro models [Citation37]. However, there appears to be a limitation of methods employed to separate the different cell types in vitro as the endovascular trophoblasts are within the vascular lumen and failed to be identified [Citation37].

There is a soluble form of CD56 in the circulation [Citation21, Citation40], and it will be interesting and useful to see if the levels of the soluble CD56 is associated with development of preeclampsia.

Conclusion

Phenotypic switch of endovascular trophoblasts in the maternal spiral artery and persistence of CD56 expression in decidual vasculopathy in pregnancy complication suggest a different pathogenesis in preeclampsia, and CD56 expression by immunohistochemical staining help identify decidual vasculopathy in difficult cases of pregnancy complications.

Compliance with ethical standards

The study is based on the case-review and exempted from the review of Institutional reviewed board.

Contribution

PZ designed, conducted the study and wrote the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful for helpful communication with Dr. Jeehyoung Kim who developed the R-statistic programs (http://statistics4everyone.blogspot.com/) for analysis of our data.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Benirschke K, Burton GJ, Baergen RN. Pathology of the human placenta. 6th ed. 2012. Springer: New York.

- Ananth CV, Keyes KM, Wapner RJ. Pre-eclampsia rates in the United States, 1980–2010: age-period-cohort analysis. BMJ. 2013;347:f6564–f6564. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.f6564.

- Kim YM, Chaemsaithong P, Romero R, Shaman M, Kim CJ, Kim JS, Qureshi F, Jacques SM, Ahmed AI, Chaiworapongsa T, et al. Placental lesions associated with acute atherosis. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2015;28:1554–1562. doi:https://doi.org/10.3109/14767058.2014.960835.

- Zhang P, Schmidt M, Cook L. Maternal vasculopathy and histologic diagnosis of preeclampsia: poor correlation of histologic changes and clinical manifestation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194:1050–1056. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2005.10.196.

- Robertson WB, Brosens I, Dixon HG. The pathological response of the vessels of the placental bed to hypertensive pregnancy. J Pathol. 1967;93:581–592. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/path.1700930219.

- Labarrere C, Alonso J, Manni J, Domenichini E, Althabe O. Immunohistochemical findings in acute atherosis associated with intrauterine growth retardation. Am J Reprod Immunol Microbiol. 1985;7:149–155. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0897.1985.tb00344.x.

- Labarrere CA. Acute atherosis: a histopathological hallmark of immune aggression? Placenta. 1988;9:95–108. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/0143-4004(88)90076-8.

- Kitzmiller JL, Watt N, Driscoll SG. Decidual arteriopathy in hypertension and diabetes in pregnancy: immunofluorescent studies. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1981;141:773–779. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/0002-9378(81)90703-1.

- Kitzmiller JL, Aiello LM, Kaldany A, Younger MD. Diabetic vascular disease complicating pregnancy. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1981;24:107–123. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/00003081-198103000-00011.

- Kitzmiller JL, Benirschke K. Immunofluorescent study of placental bed vessels in pre-eclampsia of pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1973;115:248–251. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/0002-9378(73)90293-7.

- Labarrere CA, DiCarlo HL, Bammerlin E, Hardin JW, Kim YM, Chaemsaithong P, Haas DM, Kassab GS, Romero R. Failure of physiologic transformation of spiral arteries, endothelial and trophoblast cell activation, and acute atherosis in the basal plate of the placenta. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;216:287e1–e16.

- Hecht JL, Zsengeller ZK, Spiel M, Karumanchi SA, Rosen S. Revisiting decidual vasculopathy. Placenta. 2016;42:37–43. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.placenta.2016.04.006.

- Norwitz ER, Schust DJ, Fisher SJ. Implantation and the survival of early pregnancy. N Engl J Med. 2001; 345:1400–1408. doi:https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra000763.

- Cross JC, Werb Z, Fisher SJ. Implantation and the placenta: key pieces of the development puzzle. Science. 1994;266:1508–1518. doi:https://doi.org/10.1126/science.7985020.

- Goldman-Wohl DS, Ariel I, Greenfield C, Hochner-Celnikier D, Cross J, Fisher S, Yagel S. Lack of human leukocyte antigen-G expression in extravillous trophoblasts is associated with pre-eclampsia. Mol Hum Reprod. 2000;6:88–95. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/molehr/6.1.88.

- Roberts JM, Taylor RN, Musci TJ, Rodgers GM, Hubel CA, McLaughlin MK. Preeclampsia: an endothelial cell disorder. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1989;161:1200–1204. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/0002-9378(89)90665-0.

- Proll J, Blaschitz A, Hartmann M, Thalhamer J, Dohr G. Human first-trimester placenta intra-arterial trophoblast cells express the neural cell adhesion molecule. Early Pregnancy. 1996;2:271–275.

- Kam EP, Gardner L, Loke YW, King A. The role of trophoblast in the physiological change in decidual spiral arteries. Hum Reprod. 1999;14:2131–2138. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/14.8.2131.

- Hertig A. Vascular pathology in the hypertensive albuminuric toxemias of pregnancy. Clinics. 1945;4:602–614.

- Sundberg M, Jansson L, Ketolainen J, Pihlajamaki H, Suuronen R, Skottman H, Inzunza J, Hovatta O, Narkilahti S. CD marker expression profiles of human embryonic stem cells and their neural derivatives, determined using flow-cytometric analysis, reveal a novel CD marker for exclusion of pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cell Res. 2009;2:113–124. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scr.2008.08.001.

- Kaiser U, Oldenburg M, Jaques G, Auerbach B, Havemann K. Soluble CD56 (NCAM): a new differential-diagnostic and prognostic marker in multiple myeloma. Ann Hematol. 1996;73:121–126. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s002770050212.

- Khong TY, Mooney EE, Ariel I, Balmus NC, Boyd TK, Brundler MA, Derricott H, Evans MJ, Faye-Petersen OM, Gillan JE, et al. Sampling and Definitions of Placental Lesions: Amsterdam Placental Workshop Group Consensus Statement. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2016;140:698–713. doi:https://doi.org/10.5858/arpa.2015-0225-CC.

- Bustamante Helfrich BCN, He H, Cerda SR, Hong X, Wang G, Pearson C, Burd I, Wang X. Maternal vascular malperfusion of the placental bed associated with hypertensive disorders in Boston Birth Cohort. Placenta. 2017;52:106–113. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.placenta.2017.02.016.

- Redline RW, For the Society for Pediatric Pathology, Perinatal Section, Maternal Vascular Underperfusion Nosology Committee, Boyd T, Campbell V, Hyde S, Kaplan C, Khong TY, Prashner HR, Waters BL. Maternal vascular underperfusion: nosology and reproducibility of placental reaction patterns. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2004;7:237–249. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10024-003-8083-2.

- Kim YM, Chaemsaithong P, Romero R, Shaman M, Kim CJ, Kim JS, Qureshi F, Jacques SM, Ahmed AI, Chaiworapongsa T, et al. The frequency of acute atherosis in normal pregnancy and preterm labor, preeclampsia, small-for-gestational age, fetal death and midtrimester spontaneous abortion. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2015;28:2001–2009. doi:https://doi.org/10.3109/14767058.2014.976198.

- Brosens I, Robertson WB, Dixon HG. The physiological response of the vessels of the placental bed to normal pregnancy. J Pathol. 1967;93:569–579. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/path.1700930218.

- Chan J, H D, Baergen R. Decidual vasculopathy: placental location and association with ischemic lesions. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2017;20:44–48. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1093526616689316.

- Pijnenborg R, V L, Hanssens M. The uterine spiral arteries in human pregnancy: facts and controversies. Placenta. 2006; 27:939–958. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.placenta.2005.12.006.

- Craven CM, Morgan T, Ward K. Decidual spiral artery remodeling begins before cellular interaction with cytotrophoblasts. Placenta. 1998;19:241–252. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0143-4004(98)90055-8.

- Khong TY, Wolf F, Robertson WB, Brosens I. Inadequate maternal vascular response to placentation in pregnancies complicated by pre-eclampsia and by small-for-gestational age infants. BJOG:An International Journal of O&G. 1986; 93:1049–1059. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0528.1986.tb07830.x.

- Khong T, Chambers HM. Alternative method of sampling placentas for the assessment of uteroplacental vasculature. J Clin Pathol. 1992;45:925–927. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/jcp.45.10.925.

- Red-Horse K, Zhou Y, Genbacev O, Prakobphol A, Foulk R, McMaster M, Fisher SJ. Trophoblast differentiation during embryo implantation and formation of the maternal-fetal interface. J Clin Invest. . 2004; 114:744–754. doi:https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI200422991.

- Lash GE, Otun HA, Innes BA, Percival K, Searle RF, Robson SC, Bulmer JN. Regulation of extravillous trophoblast invasion by uterine natural killer cells is dependent on gestational age. Hum Reprod. 2010; 25:1137–1145. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/deq050.

- Lash GE, Robson SC, Bulmer JN. Review: functional role of uterine natural killer (uNK) cells in human early pregnancy decidua. Placenta. 2010;31:S87–S92. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.placenta.2009.12.022.

- Hanna J, Goldman-Wohl D, Hamani Y, Avraham I, Greenfield C, Natanson-Yaron S, Prus D, Cohen-Daniel L, Arnon TI, Manaster I, et al. Decidual NK cells regulate key developmental processes at the human fetal-maternal interface. Nat Med. 2006;12:1065–1074. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/nm1452.

- Nadkami S, S J, Sferruzzi-Perri AN, Ledwozyw MK, Hass R, Mauro C, Williams DJ, Farsky SH, Marelli-Berg F, Perretti M. Neutrophils induce proangiogenic T cells with a regulatory phenotype in pregnancy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:E8415–24. doi:https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1611944114.

- Vento-Tormo R, E M, Botting RA, Turco MY, Vento-Tormo M, Meyer KB, Park JE, Stephenson E, Polanski K, Goncalves A, et al. Single-cell reconstruction of the early maternal-fetal interface in humans. Nature. 2018;563:347–353. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-018-0698-6.

- Krendl C, S D, Rishko V, Ori C, Ziegenhain C, Sass S, Simon L, Muller NS, Straub T, Brooks KE, et al. GATA2/3-TFAP2A/C transcription factor network couples human pluripotent stem cell differentiation to trophectoderm with repression of pluripotency. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2017;114:E9579–E88. doi:https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1708341114.

- Fu B, Li X, Sun R, Tong X, Ling B, Tian Z, Wei H. Natural killer cells promote immune tolerance by regulating inflammatory TH17 cells at the human maternal-fetal interface. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:E231–40. doi:https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1206322110.

- Taylor RN, Heilbron DC, Roberts JM. Growth factor activity in the blood of women in whom preeclampsia develops is elevated from early pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1990;163:1839–1844. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/0002-9378(90)90761-U.