ABSTRACT

Background

Meckel’s diverticulum (MD) is a remnant of the omphalomesenteric duct. Although the majority of MD are asymptomatic, it can present with severe hematochezia. Hematochezia is generally considered to result from a peptic ulcer caused by ectopic gastric mucosa in MD. However, this hypothesis has not been proved.

Methods

10 cases of surgically resected MD initially presenting with severe hematochezia were histologically examined.

Results

Ectopic gastric mucosa was present in 9 cases, two of which also contained ectopic pancreas. No ectopic tissue was found in one case, which shows that bleeding can occur in MD without ectopic gastric mucosa. In addition, a rupture of aberrant submucosal arterioles through the overlying mucosa, a vascular abnormality called Dieulafoy’s lesion, was detected in all the 10 cases.

Conclusion

This study suggests that the actual cause of massive bleeding in MD is not a peptic ulcer, but Dieulafoy’s lesion.

Introduction

Meckel’s diverticulum (MD) is a small outpouching of the gastrointestinal tract caused by the incomplete obliteration of the omphalomesenteric duct between the 5th and 7th week of fetal life. Although MD usually remains asymptomatic, its complications include bleeding, obstruction, and inflammation. The most common complication in children is bleeding, which is potentially life-threatening and frequently severe enough to require blood transfusion [Citation1,Citation2]. Indeed, if an infant or child presents with significant painless rectal bleeding, the presence of MD has to be suspected. It has been widely accepted that the bleeding results from a peptic ulcer caused by the acid-producing ectopic gastric mucosa in MD [Citation1–5]. However, in the author’s experience, a large and/or deep ulcer that can cause such severe hemorrhage is infrequently detected in resected MD, and furthermore MD without ectopic gastric mucosa also can develop serious bleeding.

First described in 1898 by French surgeon George Dieulafoy, Dieulafoy’s lesion (DL) is a vascular abnormality characterized by a large tortuous submucosal arteriole that erodes the overlying mucosa and leads to massive bleeding if ruptured. DL can occur throughout the gastrointestinal tract. The most common site is the stomach, which accounts for nearly three-quarters of all DLs, followed by the duodenum, esophagus, colon, and small intestine [Citation6,Citation7]. Although DL is one of the significant causes of severe gastrointestinal bleeding, it has not been suggested as the cause of hematochezia in MD. In this study, we investigated the presence of DL in MD by histological examination and clarified the cause of massive bleeding in MD.

Materials and methods

This study examined 10 cases of pediatric patients who underwent the surgical removal of MD initially presenting with severe hematochezia at Miyagi Children’s Hospital, Japan. Pertinent clinical and histological information is summarized in . The patients included 9 males and 1 female, and the mean age at presentation was 6.8 years (range, 1.8–14.8 years). All 10 patients exhibited moderate to severe anemia due to hematochezia, and 4 cases required blood transfusion. Technetium-99m pertechnetate (Tc-99m) scintigraphy demonstrated abnormal uptake in the expected area of occurrence of MD in 8 cases. For histological examination, the resected specimens were fixed in 10% formalin, sliced at 5 mm intervals, embedded in paraffin, sectioned at 3.0 µm thickness, and stained with hematoxylin-eosin and Elastica-Masson stains. If the specimen was not immediately diagnostic, up to 50 30-μm step sections were added to detect the vascular lesion.

Table 1. Summary of the cases.

Results

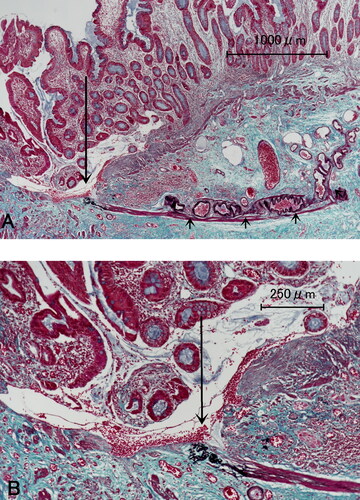

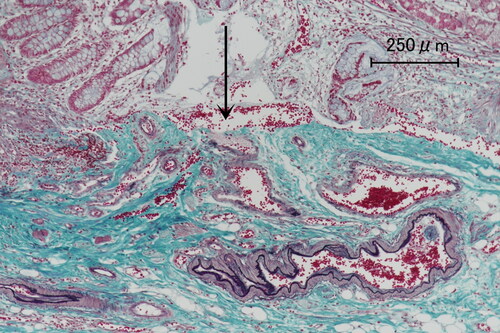

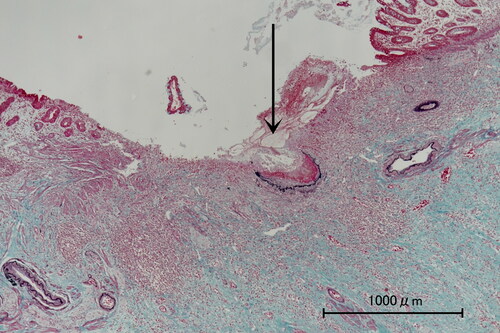

The results are summarized in . Macroscopic observation of the resected specimen revealed a minute ulcer in one case (case 1), but ulcerated lesions were not evident in the other 9 cases. Histological examination found ectopic gastric mucosa in 9 cases, all of which were oxyntic, and ectopic pancreas in two cases. No ectopic tissue was found in one case. Aberrant submucosal arterioles were observed in all 10 cases, which exhibited marked tortuosity with various degrees of proliferation. The tissue around the arterioles did not resemble granulation tissue. A rupture of these arterioles into the intestinal lumen with a small mucosal defect, that is, DL, was detected in all 10 cases (Figures –). DL appears to be an ulcer that has eroded into an underlying arteriole. However, except for case 1, the lesion was so small that it was covered with surrounding mucosa, which was ileal in 7 cases, gastric in one case, and junction of them in one case.

Figure 1. Photomicrograph of case 1. Elastica-Masson staining shows a ruptured arteriole (arrow) with a mucosal defect, measuring up to 2 mm in diameter.

Discussion

The present study showed that the immediate cause of bleeding in MD cases was not a peptic ulcer, but DL, which is compatible with the severe hemorrhage and lack of ulceration observed. DL is a serious diagnostic challenge as the lesion is usually quite small and surrounded by a normal surface. Without suspicion, it can be easily missed both clinically and pathologically. An ordinary histological examination is often insufficient for histological diagnosis, and many pieces of step sections are required for successful detection.

Tc-99m scintigraphy, which examines for the presence of ectopic gastric mucosa, is a useful diagnostic method in the differential diagnosis of pediatric patients with gastrointestinal bleeding. Ectopic tissue was positive in 8 of the 10 cases in our series, which is consistent with the histological findings (). However, negative findings of Tc-99m scintigraphy, such as in cases 6 and 10 in our series cannot exclude MD because it sometimes fails to detect MD due to the absence or paucity of ectopic gastric mucosa [Citation5].

Ectopic tissue was absent in one case (case 10), indicating that bleeding can occur in MD regardless of the presence of ectopic tissue. The other 9 cases contained ectopic tissue, which suggests that MD with ectopic tissue is more likely to cause bleeding. This is supported by the data that the frequency of symptoms in all MD is approximately 2%–4%, whereas those in MD with ectopic tissue is as high as 60% [Citation4]. However, the present study seems to indicate that ectopic tissue does not signify bleeding in MD.

Although not employed in this study, angiography can be a diagnostic tool for MD [Citation5,Citation8]. MD receives arterial blood supply from the vitelline artery, a remnant of the omphalomesenteric artery, which usually arises from a distal ileal branch of the superior mesenteric artery. Visualization of this artery on angiography is diagnostic for MD. It is also characteristic to see a group of tortuous vessels at the distal portion of the vitelline artery, which may be an origin of DL. Okazaki et al. [Citation8] reported that a dense capillary staining of the vitelline artery was exclusively found in patients with ectopic gastric mucosa, which suggests that MD with ectopic tissue may be more likely to contain DL. However, DL occurred away from the ectopic gastric mucosa in 8 of 10 cases in this study. Therefore, there seemed to be no close relationship between DL and ectopic gastric mucosa.

Conclusions

This systematic histological study detected DL in all the cases of MD examined. This important finding strongly suggests that the massive bleeding in MD is caused by DL.

Acknowledgment

The author would like to thank Mr. Kenji Takasaki and Ms. Masumi Kurumada for their technical assistance in the histological examination for this paper, and Enago (www.enago.jp) for the English language review.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Funding

The author(s) reported there is no funding associated with the work featured in this article.

References

- Turgeon DK, Barnett JL. Meckel’s diverticulum. Am J Gastroenterol. 1990;85(7):777–81. PMID: 2196781

- Kennedy M, Liacouras CA. Meckel diverticulum and other remnants of the omphalomesenteric duct. In: Kliegman RM, Stanton BF, Schor NF, St. Geme III JW Behrman RE, editors. Nelson textbook of pediatrics. 19th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2011. p. 1281–2.

- Hansen CC, Søreide K . Systematic review of epidemiology, presentation, and management of Meckel’s diverticulum in the 21st century. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97(35):e12154 doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000012154. PMID: 30581496

- Keese D, Rolle U, Gfroerer S, Fiegel H . Symptomatic Meckel’s diverticulum in pediatric patients-case reports and systematic review of the literature. Front Pediatr. 2019;7:267 doi:10.3389/fped.2019.00267. PMID: 31294008

- Kovacs M, Botstein J, Braverman S . Angiographic diagnosis of Meckel’s diverticulum in an adult patient with negative scintigraphy. J Radiol Case Rep. 2017;11(3):22–9. doi:10.3941/jrcr.v11i3.2032. PMID: 28584569

- Baxter M, Aly EH . Dieulafoy’s lesion: current trends in diagnosis and management. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2010;92(7):548–54. doi:10.1308/003588410X12699663905311. PMID: 20883603

- Senger JL, Kanthan R. The evolution of Dieulafoy’s lesion since 1897: then and now-a journey through the lens of a pediatric lesion with literature review. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2012;2012:432517. doi:10.1155/2012/432517. PMID: 22474434

- Okazaki M, Higashihara H, Saida Y, Minami M, Yamasaki S, Sato S, Nagayama H . Angiographic findings of Meckel’s diverticulum: the characteristic appearance of the vitelline artery. Abdom Imaging. 1993;18(1):15–9. doi:10.1007/BF00201693. PMID: 32726168