ABSTRACT

The rising popularity of veganism and vegetarianism has attracted significant market attention, yet limited understanding exists regarding consumer perceptions and adoption of these ethical and sustainable lifestyle choices. To address this gap, we conducted a netnographic analysis using Google Trends and HappyCow. Google Trends data found that food and restaurant-related searches predominated, with lower volumes in France, indicating a distinct food culture and potentially less interest in veganism. Australians exhibited higher search frequencies for “vegan,” reflecting a keen interest in vegan food establishments and products. HappyCow data indicated a relatively more significant number of vegan outlets in Australia. This study provides cross-cultural insights into consumer information-seeking behavior regarding veganism, highlighting the availability of vegan choices in diverse food settings and influencing factors for plant-based alternatives.

1. Introduction

The increasing popularity of vegan and vegetarian food, commonly referred to as plant-based options, has elicited significant attention worldwide. This surge in interest can be attributed to concerns surrounding various aspects, including environmental sustainability, human health, animal welfare, and global hunger (Besson, Bouxom, and Jaubert Citation2020; D’Souza, Brouwer, and Singaraju Citation2022). Despite the growing awareness and availability of such food choices, adopting a plant-based lifestyle remains relatively limited. To effectively develop targeted interventions, it is imperative to understand how consumers perceive and engage with the plant-based lifestyle. However, the current literature lacks a comprehensive analysis that integrates consumer behavior research with market development strategies under the lens of behavior change theories. This study innovatively bridges the empirical analysis of veganism-related search trends via Google Trends and HappyCow with the theoretical insights of the Transtheoretical Model. This integrative approach is meticulously designed to dissect the nuances of consumer interest evolution and market response, providing a holistic understanding of the transition toward plant-based diets.

Prior studies that focused on the stages of change in the plant-based lifestyle adoption have explored the importance of perceived pros and cons in dietary change (Canseco-Lopez and Miralles Citation2023; Lea, Crawford, and Worsley Citation2006; Lourenco et al. Citation2022; Wolstenholme et al. Citation2021; Wyker and Davison Citation2010). However, the importance of increased awareness and market availability of plant-based foods remained unclear. This is important as lack of knowledge and low availability of plant-based options were the most frequent barriers to following plant-based diets (Bryant, Prosser, and Barnett Citation2022). Search engines and social media provide a platform for people to search for information and share opinions (Zhao and Zhang Citation2017), allowing researchers to uncover what people want to know and an indication of their thoughts; many platforms offer data extraction and analytical tools.

This research aims to fill this gap and contribute to the literature by exploring consumer information about veganism and considering market dynamics. To accomplish this, data from Google Trends and HappyCow were selected as sources to understand how curiosity and awareness of veganism are developed and how market offerings align with consumer demands. The choice of these websites is due to their availability in terms of access to data. The selection of Google Trends and HappyCow as pivotal data sources is underpinned by their proven efficacy in reflecting real-time consumer interests and the geographical distribution of vegan options. This choice is further bolstered by a critical evaluation of their utility in capturing the dynamic interplay between consumer curiosity and the accessibility of plant-based foods, addressing a significant research gap in the literature.

This research specifically focuses on exploring veganism in Australia, France, Spain, and Portugal, considering the importance of regional background in global food transitions (Lourenco et al. Citation2022). Focusing on Australia, France, Spain, and Portugal, this research acknowledges the critical influence of regional backgrounds on food transition trends. The deliberate selection of these countries, based on their unique cultural and dietary landscapes, facilitates a comparative analysis that enriches our understanding of global veganism adoption patterns. The choice to study veganism in Australia, France, Spain, and Portugal is grounded in the diverse cultural and dietary landscapes these countries offer, providing a rich context for examining the adoption of veganism. Each country’s unique sociocultural background influences consumer attitudes toward veganism, making them ideal case studies for exploring the global vegan movement. [C4] This study’s structured approach, leveraging both theoretical and empirical methodologies, aims to unravel the complex process of dietary change, offering valuable insights into consumer behavior, market dynamics, and the cultural adaptation of veganism across diverse contexts.

2. Theoretical framework

Theoretical frameworks are important in understanding behavioral changes related to dietary and lifestyle choices (Wyker and Davison Citation2010). In this study, we adopt the Transtheoretical Model (TM, Prochaska et al. Citation1994) to explore the attraction of a vegan diet. The TM is widely used in behavior change research, including dietary and lifestyle transitions (Kambanis et al. Citation2022; Lea, Crawford, and Worsley Citation2006; Lourenco et al. Citation2022).

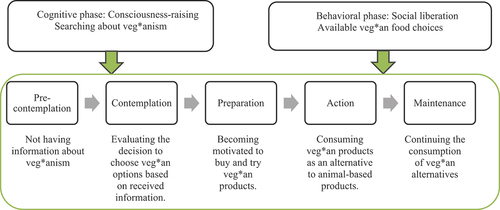

In the realm of veganism, the Transtheoretical Model (TM) has been effectively utilized to scrutinize the different stages of becoming vegan (Bryant, Prosser, and Barnett Citation2022; Mendes Citation2013; Salehi, Díaz, and Redondo Citation2020). The TM’s relevance to veganism lies in its ability to delineate the progression through various stages of change, from initial unawareness to sustained adoption of a vegan diet. According to the TM, individuals progress through five stages of change during the behavior change process: (1) pre-contemplation, characterized by lack of familiarity; (2) contemplation, involving reflection on the need for change; (3) preparation, focusing on planning for change; (4) action, encompassing the adoption of new habits, and (5) maintenance, involving the ongoing practice of the new behavior (Prochaska Citation2020). These stages are underpinned by various processes of change, with particular relevance to this research being consciousness-raising (seeking information about the issue) and social liberation (increasing availability and supportive behaviors in favor of new behavior). Several studies have highlighted the low familiarity of consumers and the limited market availability of vegan choices as barriers to transitioning to a vegan lifestyle (Adise, Gavdanovich, and Zellner Citation2015; Bryant, Prosser, and Barnett Citation2022).

This study delves deeper into the consciousness-raising and social liberation processes within TM, highlighting their critical roles in the adoption of veganism. Consciousness-raising involves the active search for information about veganism, reflecting the cognitive phase where individuals begin to contemplate dietary change. Social liberation, on the other hand, emphasizes the growing market availability of vegan options, facilitating the move toward action and maintenance stages. We further elaborate on how Google Trends and HappyCow data exemplify these TM processes. Search trends reflect the public’s growing curiosity and engagement with veganism, indicative of the consciousness-raising phase. Meanwhile, HappyCow listings serve as a barometer for social liberation, revealing the increasing acceptance and support for vegan choices in the marketplace. By integrating these data sources, we aim to provide a nuanced understanding of the factors driving the shift toward vegan diets, thereby enriching the literature on vegan consumer behavior and market dynamics.

2.1. Cognitive phase: consciousness raising

Motivation to switch to veganism often stems from an awareness of the environmental impacts of farming, concerns for human health, animal welfare, world hunger, and food justice issues (Janssen et al. Citation2016). While the number of vegans or individuals transitioning to plant-based diets is unavailable, these percentages likely remain relatively small in most Western countries. Limited awareness and familiarity with veganism continue to hinder the transformation to vegan lifestyle (Adise, Gavdanovich, and Zellner Citation2015). As shown in , individuals in earlier stages of the TM are involved in the cognitive process of seeking information on veganism.

There is increasing interest in consumers’ willingness to choose vegan products; barriers such as food neophobia and concerns about food technology were found to inhibit cultured meat (Alcorta et al. Citation2021; Rombach et al. Citation2022). Food curiosity, beliefs about meat’s importance, and consumers’ perceptions of cultured meat as a realistic alternative to regular meat were important drivers that positively impacted consumers’ willingness to try, buy and pay more (Rombach et al. Citation2022). While population percentages remain low, the number of people eating plant-based foods has doubled from 2008 to 2019 in some markets (Alae-Carew et al. Citation2021). Those individuals who become convinced to try vegan products after their evaluation of these novel products may enter a behavioral phase (preparation, action, and maintenance).

2.2. Behavioural phase: social liberation

In the behavioral phase of the Transtheoretical Model, market availability plays a crucial role in facilitating behavior change. This phase focuses on the adoption of new habits and the actualization of behavioral choices. In the context of veganism, the market has witnessed the emergence of various options for individuals interested in alternative proteins, reflecting the growing demand for plant-based products. One of the key challenges in promoting alternative proteins is to ensure their acceptability among consumers. This involves addressing concerns related to the nutrient content and sensory traits of these products. For instance, fermentation has been explored as a potential solution to improve the sensory attributes and overall acceptability of alternative proteins (Molfetta et al. Citation2022).

By addressing these issues, alternative proteins can become more appealing and viable for individuals seeking vegan options. To investigate the dynamics of market availabilities and their influence on consumer behavior, our research employed a theory-driven version of netnography combined with data from Google Trends, and HappyCow. Google Trends data provided insights into consumer interest and information-seeking behavior related to veganism. In contrast, HappyCow data allowed us to explore the availability of vegan outlets in Australia, France, Spain, and Portugal. By integrating these data sources, we aimed to understand how market availabilities contribute to the social liberation process in the transition toward vegan diets. This approach enabled us to explore the interplay between consumer perspectives, market trends, and product availability, shedding light on the factors that facilitate or hinder the adoption of vegan choices. Through our methodological framework, we sought to bridge the gap between consumer behavior and market development, applying behavior change theories to analyze the stages of becoming vegan. By investigating the consciousness-raising process and the social liberation phase, we aimed to provide insights into the factors that shape consumer behavior and contribute to the expansion of vegan markets.

Overall, our research seeks to contribute to the existing literature by analyzing vegan consumer behavior and market dynamics. By examining the interrelationships between consumer perspectives, market availabilities, and behavior change theories, we aim to provide valuable insights into the process of change in the context of veganism.

3. Methods

3.1. Research design

The present study employed a mixed-methods approach, combining qualitative analysis of market availability. The study aimed to examine the differences in interest and engagement with veg*anism, as well as the specific topics and trends related to vegan diets and social media platforms. Additionally, the research sought to explain these differences and identify insights for improving access to and consumption of vegan products.

3.2. Research questions

The following questions guided the data collection and analysis:

How do Australia, France, Spain, and Portugal differ in terms of interest (consciousness-raising and social liberation) in veg*anism as indicated by netnography analysis?

What are people across these countries searching for in relation to veg*anism on social media?

How can differences be explained, and what are the learnings for improving access to and consumption of veg*an products?

3.3. Data collection

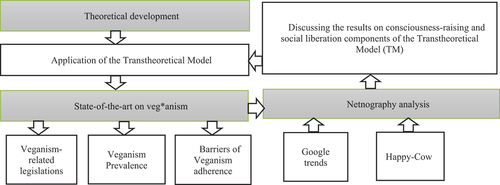

As it is shown in , to gather data for analysis, we utilized a modified version of netnography, a research methodology renowned for its efficacy in collecting and analyzing data directly from the internet and online communities (Borodako, Berbeka, and Rudnicki Citation2018; Kozinets and Gretzel Citation2022).

Google Trends. Google Trends, while a widely used platform for researching topics of interest and understanding research behavior (ZDNET Citation2022), comes with certain limitations. One such limitation is that it may not encompass all online search activity, as it only tracks searches conducted on Google. Additionally, the data provided by Google Trends are relative and may not reflect absolute search volumes. Moreover, Google Trends does not provide demographic information about the users conducting the searches, which limits the ability to draw precise conclusions about specific audience segments. Despite these limitations, Google Trends was chosen for this research due to its ability to customize searches by region, period, and category, enabling the analysis of changes and trends over time. Its widespread use and accessibility make it a valuable tool for gaining insights into broad patterns of interest in veg*anism across different regions.

In December 2022, an initial search was conducted on Google Trends using the search terms: “vegan” AND (Australia OR Spain OR France). For Australia, the search term was “vegan,” for France “vegan+vegetalien+vegetalienne,” and for Spain “vegano+vegana.” Google Translate indicated that the term used in Portugal was “vegano,” but Google Trends failed to provide data. Based on advice received from a reviewer in Portugal, it was determined that the term “vegan” was widely used, and the search was repeated using that term. The chosen category for analysis was “Food and Drink.”

HappyCow. Happy Cow (Citation2019) is a platform for searching for vegan, vegetarian, or veg-friendly establishments. Founded initially as a guide to vegetarian and vegan restaurants, HappyCow provides listings for various entities, including health food shops, juice bars, vegan-friendly accommodations, social and activity groups, and catering operations. It serves as an indicator of the availability of veg*an food products and establishments. HappyCow is included in our methodology to complement the consumer demand insights provided by Google Trends, offering a perspective on the supply side of the vegan and vegetarian food market. For this study, the number of HappyCow listings in each country was examined to determine the comparative availability of vegan, vegetarian, or veg-friendly products. The listings were analyzed to identify regional differences that might reflect varying levels of market acceptance of veg*an products.

3.4. Data analysis

The data collected from Google Trends, and HappyCow were analyzed using both quantitative and qualitative approaches. The analysis of Google Trends data involved examining the search volume for vegan and related terms in Australia, France, Spain, and Portugal from January 2004 to February 2023. Google Trends provides a normalized value ranging from 0 to 100, called relative search volume, which indicates the users’ interest in a keyword compared to the total web queries. The analysis focused on the search interest trends in each country.

4. Results

4.1. Google trends

Google Trends has some complexity in interpretation, but for this research, it indicates interest compared with other searches in each country. It also provides the search phrases people have been using over the previous 12 months, indicating what people are thinking about regarding veganism. Google Trends quantifies the users’ interests in a keyword by returning a normalized value ranging from 0 to 100, called relative search volume, proportional to the ratio between keyword-related and total web queries (Google Citation2022). The user can narrow the analysis to specific geographical areas (continents, states, regions, cities, etc.) in a fixed timelapse (Rovetta Citation2021).

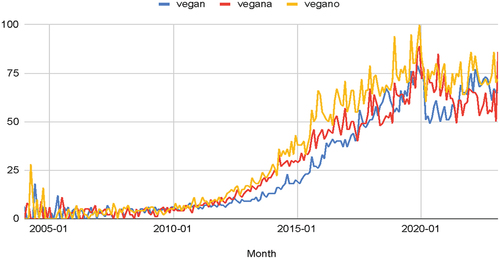

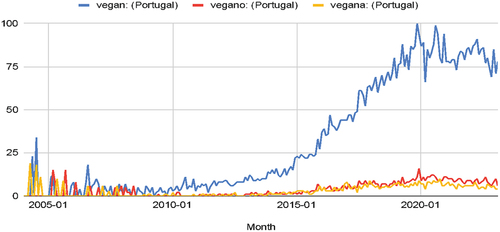

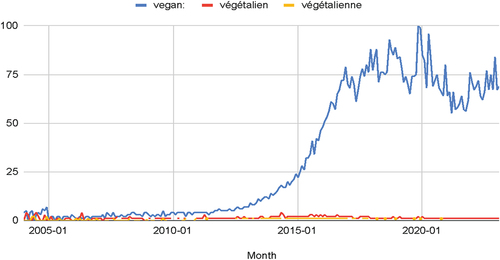

A Google Trends search was undertaken in February 2023 for vegan and local terms from 2004 up to 2023. Our designed keywords were “vegan” in Australia; “vegan” or “végétalien” or “végétalienne” in France; “vegan” or “vegana” or “vegano” in Spain, and “vegan” or “vegana” or “vegano” in Portugal.

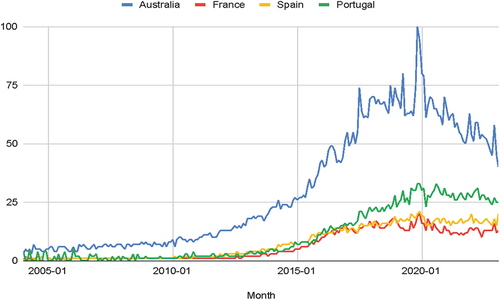

presents the monthly count of search activity involving the term vegan (and its local terms) in the four countries from January 2004 to February 2023. Numbers represent search interest relative to the highest point on the chart for the given region and time. A value of 100 is the peak popularity for the term. A value of 50 means that the term is half as popular. A score of 0 means more data is needed for this term.

The search interest in vegan and (and local varieties) varied by country. In Australia, the search interest was highest, followed by Portugal, Spain, and France. The search interest in Australia has steadily increased, with a significant spike in November 2019. The Australian data mainly stays around 60–75 between 2017 and 2023. In other countries, it is a similar increasing trend. We observed a few spikes in 2008, 2013, and 2019 in France. In Spain, we see a more erratic pattern of interest, with spikes and drops throughout the years. The trend line for Australia and Portugal fluctuates more than for France and Spain, with several spikes in Australian data.

Australia. In the Australian Google Trends search results, we can see three peaks in 2022: (1) March 20–26: 91, (2) April 10–16: 95, and (3) December 18–24: 100. Australian searches rose from 71 on February 27-March 5 to 91 from 20–26 March 2022. It dropped from March 27-April-2 2022 to 80 and again rose to 95 during 10–16 April 2022. It fluctuates gradually until a peak of 100 on 18–20 December. Analyzing the searches in Australia from 2004 to 2023 () shows the evolutionary increase in vegan searches, with a peak in 2019 reaching 100. There have been several peaks since then, but the overall pattern is declining, with the last search frequency recorded below 50.

In terms of interest of Australian sub-origins, we noticed that were as follows: (1) Victoria (100), South Australia (98), Queensland (92), Western Australia (86), and Australian Capital Territory (80), New South Wales (73), and Northern Territory (68). Vegan searches during 2004–2023 in Australia were mainly associated with food; the terms veganism (100), recipe (14), and cake (4) were the top three. The data from Google Trends show that vegan searches relating to chocolate, protein, and cheese were rising.

Notably, in the last year, of the 25 top listed searches, 60% (15/25) were for food, 32% (8/25) restaurants, and 08% (2/25) a movie; in general, 92% of searches on Google with the word vegan were for food or a restaurant ().

Table 1. Searching the terms vegan: (1/1/22–1/1/23, Australia).

France. Based on the collected data from Google Trends, it appears that there has been a steady increase in searching the term vegan over the years studied, while the interest in végétalien and végétalienne terms has remained relatively stable or decreased slightly (). It is noteworthy to mention that the searching interest report (0–100) that is extracted from Google Trend is a variable selected countries and terms. In other words, by selecting four countries simultaneously the reported searching interests are comparative between countries. However, as it is illustrated in , by choosing one country the reported searching interest rates are based on France during time. As it could be seen that in December 2019 the rate in France is 100, when we analyze this country solely; while comparing the same time span with other countries (), the interest rate is lower than 25. In early 2004, the term vegan had a search interest score of 4, while other terms scored 0. However, by the end of 2019, the term vegan had a score of 100. Although the Google search interest scores are relative and are not necessarily indicative of absolute number of searches conducted for each term, the data suggest that the term vegan is becoming popular in France (compared with végétalien and/or végétalienne).

Figure 5. Searches with the term vegan, végétalien, & végétalienne in France (Google Trends 2004–2023).

In terms of sub-origins, the highest search interest during 2004–2023 is related to Alsace (98% vegan, 2% végétalien), Île de France (97% vegan, 3% végétalien), and Rhone-Alpes (97% vegan, 3% végétalien). As it is shown in , most of the searching activities were related to food category (recipe, restaurant) and regional availability of vegan products and/or restaurants in Paris.

Table 2. Searching the terms vegan, végétalien-ne : (1/1/22–1/1/23, France).

Spain. Analyzing the vegan term and the Spanish translation of the term vegan (vegano for masculine and vegana for feminine) during 2004–2023 suggests that veganism is attracting increasing interest in Spain (). In the earlier years, the interest in searching about veganism was relatively low, with some months showing zero interest. However, as time moves forward the later years, a clear upward trend in interest is observed, with some years showing very high levels of interest. For example, in November 2019, there is a peak in interest in all three terms reaching their highest level recorded. This trend decreases after 2020 (in comparison with 2018–2019 but seems to be increasing in the future. The data also shows that the searching activities were mainly through the term vegano. And the interest in terms vegan and vegana had a fluctuating pattern.

The highest interest rate in Spanish sub-origins is related to the Balearic Islands, the Canary Islands, and Catalonia. Interestingly, in all these three regions, the searches were conducted through the term vegan; while in the other areas, the term vegano has the highest percentage, followed by vegana, and vegan (). shows that 83% of searching activities were related to food; specifically, 50% were related to food products and/or meals; 33% were related to restaurants, cafes, or catering, and 17% were related to fairs or celebrities.

Table 3. Searching the terms vegan, vegana, vegano : (1/1/22–1/1/23, Spain).

Portugal. The collected data in Portugal depicts the relative search interest over time (). In 2004, the highest number of searches were related to the term vegan, with a peak of 34 in July 2004. However, this trend decreased to a very low until 2010. From 2010 to 2015, data suggest a steady growth in interest in searching using vegan terms in Portugal, and this interest had an exponential growth from 2015 to 2019, with two peaks in November 2019 and August 2020. Although the terms vegan and vegan seemed to be increasing, the interest in this term didn’t grow like the term vegan, and from 2010 to 2015, this interest in local terms was near zero.

Regarding regional interest, the data suggest the top regions are Castelo Branco District, Beja District, Azores, Evora District, and Bragança District. Interestingly in some regions, the only search term is vegan.

Likewise, with other countries, food-related searches were the top queries (i.e., vegan AND (receitas OR food OR bolo), and regional availability in the capital or country (i.e., vegan AND (lisboa OR Porto) was the highest ().

Table 4. Searching the terms vegan, vegano-a : (1/1/22–1/1/23, Portugal).

Overall, it can be observed that all countries had the highest interest in the term vegan in 2019. The term vegan seems to become the primary search for curiosity and information seeking related to veganism, even in non-English speaking countries. In our case, we focused on three Latin European countries. Furthermore, the results from different countries show that in France and Portugal, people rely on the English (or international) term vegan, compared to its translation in local terms. However, in Spain, both English and Spanish terms are popular in Google searches. It is worth noting that online information searching is the first step to learning about consumer perspective. After learning and becoming familiar with veganism, some consumers may develop the intention to try a vegan lifestyle.

Spain and France show a similar pattern of search volumes in Google. The top 12 search terms in Spain were for a vegan fair in Vigo, six search items related to specific food items or recipes (vegan tuna, mozzarella, vegan tart, paella), four restaurant search items, and for a celebrity animal activist who has attracted publicity. In France, the top search term was vegan bacon; the next two and the fourth most popular search terms were for a movie, Barbeque (https://www.imdb.com/title/tt12887770/) also released as Some Like it Rare. It is a 2021 French “comedy horror” film depicting a struggling butcher shop run by a married couple who begin hunting vegans and selling their meat, labeling it “pork.” The next most searched term was végétalien/vegan, which could indicate a search to understand vegans else a search for products/restaurants; further down in the list was “what does a vegan eat” and another for “why vegan wine,” indicating an interest in better understanding the concept. Almost half the top search terms searched for a vegan restaurant or product.

To analyze the search terms in detail coding guide was designed to classify the terms. Eight classifications emerged through coding of searching terms: (1) Food category with a focus on cooking: Fc (i.e., vegan recipes); (2) Food category with a focus on products or meals: Fp (i.e., vegan cake); (3) Food category with a focus on restaurants, cafes, bars or caterings: Fr (vegan restaurant); (4) general geographical search: G (i.e., vegan Melbourne); (5) Food category with a focus on restaurants in geographical context: FGr (i.e., best vegan restaurants in Sydney); (6) Food category with the focus on a diet: Fd (i.e., vegan diet); (7) Lifestyle aspect: L (i.e., Adidas samba vegan) (8) Media which include movies names or celebrities names: M (i.e., Bad vegan). The results are summarized in .

Table 5. Classification of searching the terms in four countries.

The analysis of the frequency of search terms shows that the most popular category of vegan-related search terms is related to food products (Fp). In Australia, the top category is Food products (Fp), representing 56% of all search terms, while the rising category is searches related to restaurants (Fr). In France, the most popular top category of vegan search terms is related to cooking and recipes (Fc), while searches on lifestyle factors are observed the most (26%). Among the searches with the local terms (végétalien.ne) in the top and rising trends, dietary inquiries (Fd) were the subject of many searches, representing 56% and 54%. In Spain, the most frequent category in top searches was related to restaurants (24%). However, the rising inquiries did not follow the same pattern and were related to media (44%), primarily searching about “The bad vegan” movie on Netflix. Most searches in local Spanish terms fell out in the food product category. In Portugal, the top category was food products (50%). Notably, the number of searches in local terms in Portugal was significantly lower than searching with the term vegan. This pattern was also observed in France. Relatedly, there was no available data on rising terms based on local terms searches in Google trends.

In this line, 56% of searches in Australia and Spain were related to vegan food products (i.e., vegan chocolate). Portugal followed the same trend, and data shows that 40% of searches on vegan terms were related to food products in Portugal. This suggests that individuals in Australia, Spain, and Portugal are highly interested in vegan food products. While in France, most of the search terms were related to the dietary aspect of veganism (i.e., vegan protein). The second most popular category was related to food products in France.

Interestingly, we observed a new category in the rising terms, media (M). In Spain, rising interest in media-related searches (primarily “The bad vegan” movie on Netflix) was the highest, with 44% of searches including the term vegan. Another trend that could be captured is the higher percentage of searches related to lifestyle (L) in rising interests (compared to top interest) in European countries. Most of these searches were related to a newly launched Adidas show. This result shows the importance of media and well-known brands in raising awareness of veganism.

Our results from the Google Trends data found that the food category is the most popular among searches, including the term vegan or equivalent. Therefore, we chose to analyze Happy Cow, an online platform for veg*an restaurants, to indicate the availability of vegan-friendly options in Australia, Spain, France, and Portugal.

4.2. HappyCow

HappyCow listings are provided by users who can be members of the public or business operators. Listings are free, and HappyCow provides guidelines and an online form to submit information. HappyCow was searched on 02/03/2023 for the number of veg*an and vegan listings for each country ().

Table 6. Happycow number of veg*an and vegan listings.

Since HappyCow compiles information worldwide, it allows for comparison between countries on the number of vegan businesses per capita. France also has a local site, VegoResto (https://vegoresto.fr/), which lists 3337 (02.03.2023) partner organizations, much less than the number of HappyCow listings. A search of VegoResto indicates that restaurants there are also found on HappyCow. Regardless HappyCow is a crude measure as there may be issues with the familiarity of restaurateurs and consumers with the HappyCow app in each country. Still, it does indicate the availability of vegan outlets in each country. It supports the anecdotal comments of vegan travelers on chat sites as well as the personal experience of the research team members in each country.

5. Discussion

This study aimed to explore the determinants of veg*anism prevalence, explicitly focusing on information seeking and market availability within the Transtheoretical Model (TM). By analyzing data from Google Trends and HappyCow, the study aimed to provide preliminary insights into the consciousness-raising (consumers’ information searching) and social liberation (market availabilities) aspects of practicing veg*anism in Australia, France, Spain, and Portugal.

5.1. Overall view of countries in this study

5.1.1. Australia

Despite being one of the highest meat-consuming countries (Bogueva and Marinova Citation2020), Australia has been consuming almost three times the average worldwide-115 kg meat per capita (Malek and Umberger Citation2021), veg*anism is increasing. One to 2 percent of Australians identify as vegan, and 4% as vegetarian (Malek and Umberger Citation2021; Pendergrast Citation2021). Animal welfare is a primary concern for many veg*ans (Pendergrast Citation2021), being environmental sustainability the second most important factor for many of them, as animal agriculture significantly contributes to greenhouse gas emissions (UNEP Citation2021). Finally, some Australian veg*ans choose this lifestyle for personal health and/or well-being. A well-planned veg*an diet can provide all nutritional needs and may help reduce the risk of certain diseases such as hypertension (Tuso et al. Citation2013), type 2 diabetes (Barnard et al. Citation2009; Lea, Crawford, and Worsley Citation2006; Tuso et al. Citation2013), COVID-19 infection (Kahleova and Barnard Citation2022), colorectal cancer (Loeb et al. Citation2022), among others.

Barriers to veg*an could be classified into three categories: (1) situational, (2) social, and (3) individual. Situational barriers are the veg*an products’ affordability and availability that may make it difficult for individuals to become veg*an. An initiative aimed at restricting “meat” terms for plant-based products failed; consumers did not find the plant-based product labeling deceptive (Buxton Citation2022a). In 2019, meat analogues reached over $150 million in the Australian market, and by 2030 plant-based sector sales are estimated to rise to approximately $3 billion (Melville et al. Citation2023). However, it still needs to be determined if consumers perceive these products as a meat substitute or establish an intention to maintain the purchasing of veg*an products (Curtain and Grafenauer Citation2019).

The increase in veg*anism in a country with the third highest per capita meat consumption may explain to some extent why negative veg*an stereotyping is common in Australia (Rodan and Mummery Citation2019). Many Australians consider meat consumption as part of the Australian way of life, perceiving veg*anism as un-Australian (Rodan and Mummery Citation2019); some meat advertising carries a masculine and nationalist theme (Drew and Gottschall Citation2018) and perpetuates the self-identity of the Australian population as meat eaters. A stigma around veganism has been given as a reason for non-vegans to be reluctant to consider vegan eating due to its perceived disruption of social conventions in relation to food (Markowski and Roxburgh Citation2019; Reuber and Muschalla Citation2022). Lastly, individuals’ eating habits, cravings for meat and other animal-based products, lack of convenience in the preparation of veg*an food, and lack of knowledge about veg*anism could be barriers to becoming veg*an in Australia.

5.1.2. France

As with many other countries, France’s veg*an market is growing (Allès et al. Citation2017). The motivation of non-veg*an people in France to adopt more plant-based products was primarily driven by health and nutrition concerns (Reuzé et al. Citation2022). French people have also been found to be concerned about the ethical and environmental problems linked to livestock farming and the conventional meat industry, and a significant percentage (45.6%) were found to believe that reducing meat consumption could be a solution to current problems (Bryant, van Nek, and Rolland Citation2020; Hocquette et al. Citation2015). France has passed animal welfare legislation to comply with EU requirements, but enforcement has been weak (Vogeler Citation2019). In some municipalities where there are Green or Parti Animalist political groups, leaders have required the provision of meat-free options in school canteens (France24 Citation2021).

France recognized animal sentience in 1976 Law10, French animal legislation, and a 2015 Civil Code reform that withdrew non-human animals from the category of legal things (Laffineur-Pauchet Citation2019). Further regulation aiming to protect animals faces strong opposition and many practices that use animals to make traditional French products continue, such as force-feeding ducks to produce foie gras or fatty liver disease, which is traditionally consumed especially for Christmas in France. France has a high level of consumption of dairy products; hard cheeses are considered an indispensable part of daily nutrition in France, although there is an increasing awareness of the effects on health (Adamczyk et al. Citation2022).

Although veganism and animal rights are becoming more accepted in France, there are unique barriers to the adoption of plant-based products and reduction in animal exploitation, including the national food tradition (Laffineur-Pauchet Citation2021) and the gastronomic identity of France. There is a strong link between traditional French food with its high density of animal products and the French national identity (Laffineur-Pauchet Citation2021); France is known for its cuisine, gastronomy, and arts de la table; these normally containing animal products, are seen as part of the French cultural heritage, and a source of national pride. This practice of eating with others together was included on UNESCO’s list of intangible cultural heritage (UNESCO Citationn. d).

Another barrier to the adoption of veg*n could be the attitudes of clinicians and clinician lack of knowledge about it. A survey of general practitioners and pediatricians in France (Vilette et al. Citation2022) found that half would dissuade patients from a vegan diet and 14% from an ovo-lacto-vegetarian diet; however, most of the respondents revealed they did not feel informed enough about these diets. While the negative attitudes of clinicians might dissuade some people from making a change, it might also discourage vegans and vegetarians from disclosing their diet practices to their clinician, which is consistent with the work of Canseco-Lopez and Miralles (Citation2023) that show that homophily and intimacy are necessary for the individual to communicate about his/her eating habits freely. The individuals consider this a private matter, and they prefer to self-disclose with their close ones (family and friends) with whom they have a certain level of homophily (connection because of their similarities regarding status and/or values). This could diminish the opportunity to receive critical information about doing vegan well, ensuring adequate nutrition, and the importance of Vitamin B12 supplementation (Bakaloudi et al. Citation2021).

For French consumers, motives underlying food choices in order of importance, taste, health and absence of contaminants, local and traditional production, price, ethics and environment, convenience, innovation, and environmental limitations (Allès et al. Citation2017) with pleasure and taste being mentioned as important drivers with regard to menu planning, and the main barriers against the adoption of plant-based foods, as well as meat reduction. For French participants, liking the taste of meat was the main reason for not consuming meat substitutes (Varela et al. Citation2022; Weinrich Citation2018). This aligns with the finding that exposure to more appealing vegan food increases preference for meat-free options (Bradford, Hancox, and Bryant Citation2022). This was borne out in relation to cultured meat - Hocquette et al (Citation2022) found barriers for French consumers were concern about the anticipated taste, health, and nutritional quality. Eighty percent of French consumers surveyed believe cultured meat will become widespread, whether they like it or not (Gousset et al. Citation2022).

In June 2022, the French Government adopted legislation to ban specific names from designating vegetable protein foodstuffs (Carreño Citation2022). The prohibition was set to come into force on 1 October 2022 following a long campaign from French meat and livestock groups seeking to uphold the country’s conventions for naming food and drink. Still, an appeal by plant-food and animal welfare groups was successful in getting a suspension over concerns about the speed and scope of the legislation (MENAFN Citation2022). In France there is a patchwork of terms applied to plant-based products; plant-based milk in supermarkets can often be found adjacent to dairy milk but labeled boisson (drink), never “milk,” Burger King (burgerking.fr/) lists its plant-based burger in the burger section of its website with the terms veggie cheese and bacon, there is a new French term “vegetalien/vegetalienne” for vegan, but vegan is still commonly used including in product labeling and restaurant menus.

Barriers to veg*an in France include the cultural traditions, negative stereotype of vegans as militant and commercial influences protecting entrenched agricultural practices (Cole and Morgan Citation2011). To improve the adoption of veg*an products, there is a need to address common barriers across countries and those specific to national values and cultures.

5.1.3. Spain

Similar to the cultural narrative in other countries, food-related behaviors play an essential role in social and cultural traditions in Spain; there has, however, been a modest rise in veg*an diets (Montesdeoca et al. Citation2021).

Spain is often seen as lagging other European countries in animal rights. The importance of animal welfare for individuals in Spain is impacted by gender, age, origin (rural or urban), and education level, with an increase in animal welfare demonstrated by those in higher socio-economic, higher education outcomes and those who live in urban areas (Estevez-Moreno et al. Citation2021). Many Spaniards perceive animal welfare as a matter of profit and a part of modern farming practices; women are more likely than men to support and pay for products that prevent animal cruelty which may be explained by the cultural norm in Spain, where men associate meat consumption with masculinity and evolutionary superiority to animals (Estevez-Moreno et al. Citation2021).

The primary legislation protecting animal rights in Spain is the Organic Law for the Protection of Animals, enacted in 2003: the measures to be taken for the protection and care of animals. Later, Royal Decree 223/2013 established the minimum standards of pet animal protection (requirements for feeding, housing, and veterinary care). In 2022 it adopted new legalization of improved conditions for animals (Library of Congress Citation2022); it offered more severe penalties for mistreating vertebrate animals and prohibited killing except for illness or health reasons. For example, dog owners must register their animals, and breeders must also be registered; this came after what was seen as a high level of pet abandonment. The regulation bans selling dogs, cats, and ferrets in pet shops and forbids using wild animals in circuses or other activities where animals could be damaged. Despite the laws, there was no mention of bullfighting.

Influenced by increased awareness of animal rights and environmental sustainability, the veg*an market in Spain has significantly grown in recent years (Montesdeoca et al. Citation2021); 4.8% of Spanish adults have been found to follow a vegetarian diet, and 0.5% self-identify as vegans (Lantern Citation2019). This number has gradually increased and is predicted to keep rising in the future.

5.1.4. Portugal

The veg*an market in Portugal has shown significant growth in the last decade. A Portuguese Vegetarian Society (Citation2019) survey indicates that the number of vegan people in Portugal doubled from 2018 to 2022 and currently stands at 5% of the population and this is largely driven by moral concerns and ethical principles around animal welfare (Miguel, Coelho, and Bairrada Citation2021). These attitudes have largely driven a lower consumption of animal products and driven legislated shifts in animal welfare and the adoption of veg*an options (Miguel, Coelho, and Bairrada Citation2021).

In addition to the increasing number of veg*ans, the range and availability of veg*an products have expanded in Portugal. Many food companies and restaurants in Portugal have responded to this demand by offering various veg*an items to their product range. This trend is likely to continue, as an increasing number of veg*an Portuguese consumers stop consuming animals for the benefit of public health, the environment, and animals.

The Portuguese Animal Protection Law (No. 107/1999) set animal protection principles for animal owners, enforcing animal welfare legislation. The Portuguese Food and Feed Code (Decree-Law No. 43/2007) establishes the conditions for the labeling and marketing of food products, including veg*an products, requiring clear and precise information on food labels.

Veg*an options have been required by law to be available in Portugal since 2017; schools, canteens, universities, hospitals, prisons, and all other public buildings are required to offer plant-based options (Russell Citation2019). This was the first law in Portugal that specifically mentioned vegetarianism. Anecdotally it appears to have resulted in more private food operators also providing vegan options, as indicated by the high number of listings in HappyCow found for Portugal compared with Spain and France.

5.2. Consciousness raising and social liberation

5.2.1. Consciousness-raising: the increase in Google trend information search

This research reveals that searching for veg*anism on Google has increased exponentially in the last decade. According to the Transtheoretical Model (TM), higher consciousness raising suggests that people are moving from pre-contemplation to the next stages of change (Mendes Citation2013). This could be interpreted that people in Australia, France, Spain, and Portugal are moving from the pre-contemplation stage to the following stages of change; however, this increase in information searching on veg*anism has not grown parallelly. Although meat eating is lower per capita in Europe than in Australia, Google Trends revealed a higher rate of searching for the terms keyword “vegan” by Australians, which may reflect more active seeking of outlets for vegan food and other products. This may reflect the difficulty experienced in finding vegan food choices at the large majority of restaurant offerings in Australia, as the culturally dominant food offerings focus on meat consumption. The similarity between Spain and France noted on Google Trends is consistent with the research by Perez-Cueto et al. (Citation2022), who found few differences between European countries. Among European countries that analyzed in this study, Portugal showed a higher increase in information searching related to veganism. Because information seeking will not necessarily be translated to actual behavior, the barriers may explain a low number of the population in action and maintenance stages (Bryant, Prosser, and Barnett Citation2022). Although veganism is increasing in France (Allès et al. Citation2017), there is a backlash against vegans, as there is in some western countries as it does not fit within the dominant self-identified food culture (Dhont and Stoeber Citation2020). The influences of masculinity and evolutionary superiority can be a powerful determinant of dietary choice and contribute to the resistance to moving toward plant-based alternatives (Stanley, Day, and Brown Citation2023). This cultural trend is reflective of the interest in the movie Bar-b-que, found four times on the list of top Google Trend searches in France, contains many stereotypes, including militant, violent vegans, and could be considered part of this sentiment. The movie may express the pushback against the perceived challenge to the French food identity by vegans and veganism. The central place of gastronomy in France may also account for the lower rating of the search for vegan overall compared to Australia.

Previous studies on the role of cognitive and practical barriers on consumer veg*anism adherence showed that the role of practical barriers was the key to moving from the preparation stage to the action stage (Lourenco et al. Citation2022). Thus, future interventions should consider knowledge and familiarity in combination with practical barriers such as veg*an food availability in different regions (Stoll-Kleemann and Schmidt Citation2017).

5.2.2. Social liberation

More Happy Cow listings per head in Australia compared to France, Spain, and Portugal is consistent with the higher ranking of Australia on vegan interest as reflected by Google Trends. However, Australia is geographically significantly larger than Spain, France, and Portugal combined, such that the cities where most vegan establishments are located are some distance from each other. At the same time, France, Spain, and Portugal are closer; therefore, those wishing to find vegan food in Europe may have easier access.

People who eat plant-based foods primarily may not frequent fast-food chain stores such as McDonalds, in many European countries due to the culturally dominant food narrative which supports meat consumption. Although, in some countries, there are vegan options in fast-food chain restaurants such as Burger King, and they have specific Burger King vegan restaurant (Vienna)). France has seen a slower growth in fast food partly because of the solid gastronomic culture (Fantasia Citation1995); the opening of new stores has been vigorously resisted at various times (Bamat Citation2015; Chrisafis Citation2018). Australia, on the other hand, has followed American trends and embraced fast food. The interest in Australia Google searching for vegan could explain the tentative introduction of McPlant. However, comparing the alleged number of vegans in each country must provide a compelling explanation for the higher Google Trend searches or the Happy Cow listings. Wikipedia lists Australia as 2% as vegans, France as 1.1%, and Spain as 0.8%. However, the rate varies in different surveys and research, and this cannot be relied on as exact. McDonald’s is not following other organizations and introducing vegan burgers (for example, Hungry Jacks), but it is known that many consumers who are not vegan are eating more plant-based foods (Curtain and Grafenauer Citation2019; Estell, Hughes, and Grafenauer Citation2021), which would explain why sales of these products have increased. Vegans alone could not account for the increase; however, this may be explained by the increasing concern across Europe and Australia about the impact of animal agriculture on the environment and global warming.

As with any other food purchase, one of the critical drivers for buying plant-based food is taste; consumers are often unwilling to compromise with the product’s preference (Adise, Gavdanovich, and Zellner Citation2015; Schenk, Rössel, and Scholz Citation2018). The strong gastronomic tradition of France indicates that to be successful, plant-based alternatives must focus on taste and texture. As the taste and texture of plant-based meat alternatives are refined, there may be a shift in the culturally dominant cuisines, which is strongly linked to national self-identity in France. These motivations and beliefs are more common among younger adults fueling the plant-based trend. Consequently, brands that align with and communicate these values are more likely to target this group of consumers successfully.

6. Conclusion

This study provides insights into the state of veganism in Australia, France, Spain, and Portugal. In terms of social liberation and the market availability of vegan choices, big cities have a higher availability of vegan restaurants. There is an opportunity to improve the availability of vegan meals in restaurants, including food chains.

6.1. Contributions

This study adopts the information-seeking approach and the social liberation (market availability) process as empirical factors in understanding consumers’ behavior. It extends previous evidence and conceptualizations on consumers’ readiness to practice veganism (Lea, Crawford, and Worsley Citation2006; Lourenco et al. Citation2022; Wyker and Davison Citation2010). Moreover, this article advances the current theoretical approach to switching to vegan lifestyle (Bryant, Prosser, and Barnett Citation2022; Mendes Citation2013; Salehi, Díaz, and Redondo Citation2020).

6.2. Limitations and future research directions

The search for information was restricted to Google and HappyCow, which may only represent some of the platforms used in different countries. Furthermore, the search data may not solely reflect the queries made by local populations, as these countries also attract many tourists. Although functional, Google Trends has limitations regarding the inferences that can be drawn from its data. Moreover, the rates of internet searches and the popularity of HappyCow can vary among these countries. Future research can be expanded to other platforms to increase the reliability of results.

This paper focused on the term vegan to compare the information searched across countries. This methodology could be expanded to other terms, such as plant-based, vegetarian, or flexitarian diets.

Finally, it is worth noting that while Google Trends offers valuable insights into the interest levels in veganism, it does not directly measure consumer perceptions or the depth of adoption of vegan lifestyles thoroughly. Future research could incorporate alternative data sources that can more accurately gauge consumer attitudes and the actual adoption of veganism. This article provides practical implications to address the increasing consumption of animal-based products and services.

6.3. Practical implication

The findings of this research hold significant practical implications for policymakers, academics, and marketers interested in understanding different segments of individuals and their response to veganism. Policymakers can utilize these results to develop more effective strategies for meeting the increased interest in vegan diets, tailoring campaigns to consider cultural traditions and preferences. Additionally, encouraging open discussions about eating habits outside individuals’ close networks could help stimulate greater engagement and acceptance. Academics stand to gain new insights into applying the Transtheoretical Model (TM) to plant-based (PB) adoption. This research can potentially lead to suggestions for improving the model and enhancing its relevance in dietary behavior change. For marketers, the results can inform the creation of workshops and practical courses that zoom in on these eating habits, aiming to motivate individuals to reconsider their previous dietary choices and embrace plant-based options. By offering educational opportunities and highlighting the benefits of plant-based diets, marketers can encourage individuals to transition toward healthier and more sustainable eating styles.

The results of this study showed the exponential growth in consumer search related to veganism. Many consumers still have insufficient knowledge regarding veganism and its importance on other sentient beings, environmental sustainability, public health, and world hunger (Lourenco et al. Citation2022). Thus, there is still a considerable need for informational campaigns and educational programs to increase awareness of the impact of food and lifestyle choices.

This research focuses on information seeking and market availabilities. However, one of the potential barriers in vegan food consumption is marketing communications. Attempts have been made in several jurisdictions to restrict or ban the use of terms associated with animal products such as mince, burger, sausage, and milk. There is no legal precedence in the European Union that prevents plant-based products from being labeled with meat-like terms such as sausage or burger; on the contrary, an amendment aiming at such a prohibition at the EU level was rejected, leading instead to the adoption of divergent legislation by member states on the labeling of plant-based products (Buxton Citation2022b). The European Parliament is also encouraging more plant-based eating, and a reduction in meat consumption is outlined in the strategy “Strengthening Europe in the Fight against Cancer” (European Parliament Citation2022). A record was set in 2021 in relation to sales of plant-based food in Europe, with an estimated increase of 19%; the €2.3 billion expansion is more significant than that for North America (GFI Citation2022). There was a 25% increase in HappyCow listings of vegan restaurants in Europe from the end of 2019 to the beginning of 2022; however, the increase in 2021 was 50% less than in previous years (Sapaico Citation2022), which is likely to have been associated with COVID.

Regarding the proposed Transtheoretical framework based on consciousness-raising and social liberation, it is essential to note that the model could not be fully confirmed in this study. However, this research opens up avenues for further investigations to explore and measure change processes across the stages of change. Furthermore, while there are some statistical reports, the number of people in action-maintenance stages could be approximately calculated. However, the number of people in the pre-disposition stages (i.e., pre-contemplation and preparation) is not precise. In this regard, future research is needed to conduct cluster analysis for segmenting non-vegan consumers in different stages, which can significantly leverage the success of future campaigns.

Ethical statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical approval H22REA287 was granted by the University of Southern Queensland Human Research Ethics Committee.

Availability of data

Data used in the study will be made available in contact with the corresponding author.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Adamczyk, D., D. Jaworska, D. Affeltowicz, and D. Maison. 2022. “Plant-Based Dairy Alternatives: Consumers’ Perceptions, Motivations, and Barriers—Results from a Qualitative Study in Poland, Germany, and France.” Nutrients 14 (10): 2171. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14102171.

- Adise, S., I. Gavdanovich, and D. A. Zellner. 2015. “Looks Like Chicken: Exploring the Law of Similarity in Evaluation of Foods of Animal Origin and Their Vegan Substitutes.” Food Quality and Preference 41:52–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2014.10.007.

- Alae-Carew, C., R. Green, C. Stewart, B. Cook, A. D. Dangour, and P. F. D. Scheelbeek. 2021. “The Role of Plant-Based Alternative Foods in Sustainable and Healthy Food Systems: Consumption Trends in the UK.” Science of the Total Environment 807:151041. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.151041.

- Alcorta, A., A. Porta, A. Tárrega, M. D. Alvarez, and M. P. Vaquero. 2021. “Foods for Plant-Based Diets: Challenges and Innovations.” Foods 10 (2): 293. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods10020293.

- Allès, B., J. Baudry, C. Méjean, M. Touvier, S. Péneau, S. Hercberg, and E. Kesse-Guyot. 2017. “Comparison of Sociodemographic and Nutritional Characteristics Between Self-Reported Vegetarians, Vegans, and Meat-Eaters from the NutriNet-Santé Study.” Nutrients 9 (9): 1023. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu9091023.

- Bakaloudi, D. R., A. Halloran, H. L. Rippin, A. C. Oikonomidou, T. I. Dardavesis, J. Williams, K. Wickramasinghe, J. Breda, and M. Chourdakis. 2021. “Intake and Adequacy of the Vegan Diet. A Systematic Review of the Evidence.” Clinical Nutrition 40 (5): 3503–3521. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2020.11.035.

- Bamat, J. 2015. “Paris Rejects Bid for New McDonalds on Historic Street, Again.” France 24. Accessed 7 Febuary, 2015. https://www.france24.com/en/20150702-paris-rejects-bid-new-mcdonald-historic-street-again.

- Barnard, N. D., J. Cohen, D. J. Jenkins, G. Turner-McGrievy, L. Gloede, Green, A. Green, and H. Ferdowsian. 2009. “A Low-Fat Vegan Diet and a Conventional Diabetes Diet in the Treatment of Type 2 Diabetes: A Randomized, Controlled, 74-Wk Clinical Trial.” The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 89 (5): 1588S–1596S. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.2009.26736H.

- Besson, T., H. Bouxom, and T. Jaubert. 2020. “Halo it’s Meat! The Effect of the Vegetarian Label on Calorie Perception and Food Choices.” Ecology of Food and Nutrition 59 (1): 3–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/03670244.2019.1652820.

- Bogueva, D., and D. Marinova. 2020. “Cultured Meat and Australia’s Generation Z.” Frontiers in Nutrition 7:148.

- Borodako, K., J. Berbeka, and M. Rudnicki. 2018. “Events KIBS on the Business Services Market–A Netnography Analysis.” European Journal of Service Management 27:7–14. https://doi.org/10.18276/ejsm.2018.27/1-01.

- Bradford, A., A. Hancox, and C. J. Bryant. 2022. “The Way to a Meat-eater’s Heart Is Through Their Stomach: Exposure to More Appealing Vegan Food Increases Preference for Meat-Free Options.” OSF Preprints. January 18. https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/746jm.

- Bryant, C. J., A. M. B. Prosser, and J. Barnett. 2022. “Going Veggie: Identifying and Overcoming the Social and Psychological Barriers to Veganism.” Appetite 169:105812. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2021.105812.

- Bryant, C., L. van Nek, and N. C. Rolland. 2020. “European Markets for Cultured Meat: A Comparison of Germany and France.” Foods 9 (9): 1152. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods9091152.

- Buxton. 2022a. Australian Consumers Not Confused by Plant-Based Foods, New Study Concludes. Green Queen. Mar 11. Accessed November 21, 2022. https://www.greenqueen.com.hk/australian-plant-based-food-labelling/.

- Buxton. 2022b. French High Court Suspends Ban on Plant-Based Brands Using “Meat” Words. Plant-Based News. Accessed 21 November Aug 1, 2022. 2022 https://plantbasednews.org/culture/law/france-suspends-ban-plant-based-meat-words/.

- Canseco-Lopez, F., and F. Miralles. 2023. “Adoption of Plant-Based Diets: A Process Perspective on Adopters’ Cognitive Propensity.” Sustainability 15 (9): 7577. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15097577.

- Carreño, I. 2022. “France Bans “Meaty” Terms for Plant-Based Products: Will the European Union Follow?” European Journal of Risk Regulation 13 (4): 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1017/err.2022.22.

- Chrisafis, A. 2018. “Choose a Side: The Battle to Keep French Isle McDonalds-Free.” The Guardian, 24 August.

- Cole, M., and K. Morgan. 2011. “Vegaphobia: Derogatory Discourses of Veganism and the Reproduction of Speciesism in UK National Newspapers 1.” The British Journal of Sociology 62 (1): 134–153. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-4446.2010.01348.x.

- Curtain, F., and S. Grafenauer. 2019. “Plant-Based Meat Substitutes in the Flexitarian Age: An Audit of Products on Supermarket Shelves.” Nutrients 11 (11): 2603. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11112603.

- Dhont, K., and J. Stoeber. 2020. “The Vegan Resistance.” The Psychologist 34 (1): 24–27.

- Drew, C., and K. Gottschall. 2018. “Co-Optation of Diversity in Nationalist Advertising: A Case Study of an Australian Advertisement.” CONTINUUM: Lifelong Learning in Neurology 32 (5): 581–593. https://doi.org/10.1080/10304312.2018.1487033.

- D’Souza, C., A. R. Brouwer, and S. Singaraju. 2022. “Veganism: Theory of Planned Behaviour, Ethical Concerns and the Moderating Role of Catalytic Experiences.” Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 66:102952. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2022.102952.

- Estell, M., J. Hughes, and S. Grafenauer. 2021. “Plant Protein and Plant-Based Meat Alternatives: Consumer and Nutrition Professional Attitudes and Perceptions.” Sustainability 13 (3): 1478. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13031478.

- Estevez-Moreno, L., G. Maria, W. Sepulveda, M. Villarroel, and G. Miranda-de la Lama. 2021. “Attitudes of Meat Consumers in Mexico and Spain About Farm Animal Welfare: A Cross-Cultural Study.” Meat Science 173:108377. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.meatsci.2020.108377.

- European Parliament. 2022. Strengthening Europe in the Fight Against Cancer: European Parliament Resolution of 16 February 2022 on Strengthening Europe in the Fight Against Cancer—Towards a Comprehensive and Coordinated Strategy (2020/2267 (INI).

- Fantasia, R. 1995. “Fast Food in France.” Theory and Society 24 (2): 201–243. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00993397.

- France 24. 2021. “French mayor’s Decision to Serve Meat-Free School Lunches Sparks Outrage (21/02/2021).” (Accessed November 11, 2022). https://www.france24.com/en/europe/20210221-french-lyon-mayor-s-decision-to-serve-meat-free-school-lunches-sparks-outrage.

- GFI. 2022. “Plant-Based Meat Sales Up 19% to Record €2.3 Billion in Western Europe, Report Shows.” Good Food Institute 2022, April 14. Accessed December 25, 2022. https://gfieurope.org/blog/plant-based-meat-sales-up-19-to-record-e2-3-billion-in-western-europe-report-shows/.

- Google. 2022. “FAQ About Google Trends Data.” Accessed December 25, 2022. https://support.google.com/trends/answer/4365533?hl=en.

- Gousset, C., E. Gregorio, B. Marais, A. Rusalen, S. Chriki, J.-F. Hocquette, and M.-P. Ellies-Oury. 2022. “Perception of Cultured “Meat” by French Consumers According to Their Diet.” Livestock Science 260:104909. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.livsci.2022.104909.

- Happy Cow. 2019. “Team HappyCow.” Accessed November 04, 2022. https://www.happycow.net/about-us.

- Hocquette, A., C. Lambert, C. Sinquin, L. Peterolff, Z. Wagner, S. P. Bonny, and J. F. Hocquette. 2015. “Educated Consumers Don’t Believe Artificial Meat Is the Solution to the Problems with the Meat Industry.” Journal of Integrative Agriculture 14 (2): 273–284.

- Hocquette, É., J. Liu, M. P. Ellies-Oury, S. Chriki, and J. F. Hocquette. 2022. “Does the Future of Meat in France Depend on Cultured Muscle Cells? Answers from Different Consumer Segments.” Meat Science 188:108776. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.meatsci.2022.108776.

- Janssen, M., C. Busch, M. Rödiger, and U. Hamm. 2016. “Motives of Consumers Following a Vegan Diet and Their Attitudes Towards Animal Agriculture.” Appetite 105:643–651.

- Kahleova, H., and N. D. Barnard. 2022. “Can a Plant-Based Diet Help Mitigate Covid-19?” European Journal of Clinical Nutrition 76 (7): 911–912. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41430-022-01082-w.

- Kambanis, P. E., A. R. Bottera, C. J. Mancuso, and K. P. De Young. 2022. “Motivation to Change Predicts Naturalistic Changes in Binge Eating and Purging, but Not Fasting or Driven Exercise Among Individuals with Eating Disorders.” Eating Disorders 30 (3): 279–301. https://doi.org/10.1080/10640266.2020.1823174.

- Kozinets, R. V., and U. Gretzel. 2022. “Netnography.” In Encyclopedia of Tourism Management and Marketing, edited by D. Buhalis, 316–319. Cheltenham, United Kingdom: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Laffineur-Pauchet, M. 2019. “First Animal Code in France: A Response to a Dissonant Animal Law, dA.” Derecho Animal (Forum of Animal Law Studies) 10 (2): 83–94. https://doi.org/10.5565/rev/da.359.

- Laffineur-Pauchet, M. 2021. “Chapter 8: The Growth of Veganism in France.” In Law and Veganism: International Perspectives on the Human Right to Freedom of Conscience, edited by J. Rowley and C. Prisco, 143–169. Lanham, Maryland: The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc.

- Lantern. 2019. “The Green Revolution: Entendiendo la Expansión de la ola “Veggie”; Lantern Papers: Madrid, Spain.” Madrid Spain: Lantern. https://www.lantern.es/papers/the-green-revolution-2019.

- Lea, E. J., D. Crawford, and A. Worsley. 2006. “Public Views of the Benefits and Barriers to the Consumption of a Plant-Based Diet.” European Journal of Clinical Nutrition 60 (7): 828–883. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602320.

- Library of Congress. 2022. “Spain: New Law Providing for Increased Protection of Animals Adopted.” Web Page, The Library of Congress. www.loc.gov/item/global-legal-monitor/2022-01-17/spain-new-law-providing-for-increased-protection-of-animals-adopted.

- Loeb, S., B. C. Fu, S. R. Bauer, C. H. Pernar, J. M. Chan, Van Blarigan, E. L. Van Blarigan, E. L. Giovannucci, S. A. Kenfield, and L. A. Mucci. 2022. “Association of Plant-Based Diet Index with Prostate Cancer Risk.” The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 115 (3): 662–670. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/nqab365.

- Lourenco, C. E., N. M. Nunes-Galbes, R. Borgheresi, L. O. Cezarino, F. P. Martins, and L. B. Liboni. 2022. “Psychological Barriers to Sustainable Dietary Patterns: Findings from Meat Intake Behaviour.” Sustainability 14 (4): 2199. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14042199.

- Malek, L., and W. J. Umberger. 2021. “Distinguishing Meat Reducers from Unrestricted Omnivores, Vegetarians and Vegans: A Comprehensive Comparison of Australian Consumers.” Food Quality and Preference 88:104081. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2020.104081.

- Markowski, K. L., and S. Roxburgh. 2019. ““If I Became a Vegan, My Family and Friends Would Hate me:” Anticipating Vegan Stigma as a Barrier to Plant-Based Diets.” Appetite 135:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2018.12.040.

- Melville, H., M. Shahid, A. Gaines, B. L. McKenzie, R. Alessandrini, K. Trieu, J. H. Y. Wu, et al. 2023. “The Nutritional Profile of Plant-Based Meat Analogues Available for Sale in Australia.” Nutrition and Dietetics 80 (2): 211–222. https://doi.org/10.1111/1747-0080.12793.

- MENAFN. 2022. “Veggie ‘Steak’ Spared the Knife in France.” Menafn.com. Accessed November 11, 2022. https://menafn.com/1104604409/Veggie-steak-spared-the-knife-in-France.

- Mendes, E. 2013. “An Application of the Transtheoretical Model to Becoming Vegan.” Social Work in Public Health 28 (2): 142–149. https://doi.org/10.1080/19371918.2011.561119.

- Miguel, I., A. Coelho, and C. M. Bairrada. 2021. “Modelling Attitude Towards Consumption of Vegan Products.” Sustainability 13 (1): 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13010009.

- Molfetta, M., E. G. Morais, L. Barreira, G. L. Bruno, F. Porcelli, E. Dugat-Bony, P. Bonnarme, et al. 2022. “Protein Sources Alternative to Meat: State of the Art and Involvement of Fermentation.” Foods 11 (14): 2065. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods11142065.

- Montesdeoca, C. C., E. S. Rodríguez, B. H. Ruiz, and I. D. Lores. 2021. “Adaptation and Validation of the Dietarian Identity Questionnaire (DIQ) into the Spanish Context.” International Journal of Social Psychology, Revista de Psicología Social 36 (3): 510–543. https://doi.org/10.1080/02134748.2021.1940703.

- Pendergrast, N. 2021. “The Vegan Shift in the Australian Animal Movement.” International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy 41 (3/4): 407–423. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSSP-08-2019-0161.

- Perez-Cueto, F. J. A., L. Rini, I. Faber, M. A. Rasmussen, K. B. Bechtold, J. J. Schouteten, and H. De Steur. 2022. “How Barriers Towards Plant-Based Food Consumption Differ According to Dietary Lifestyle: Findings from a Consumer Survey in 10 EU Countries.” International Journal of Gastronomy and Food Science 29:100587. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgfs.2022.100587.

- Portuguese Vegetarian Society. 2019. “Survey on Veganism in Portugal. https://www.vegetarianos.pt/estudo-sobre-veganismo-em-portugal/.

- Prochaska, J. O. 2020. “Transtheoretical Model of Behavior Change.” In Encyclopedia of Behavioral Medicine, edited by M. D. Gellman, 2266–2270. Cham: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-39903-0_70.

- Prochaska, J. O., C. A. Redding, L. L. Harlow, J. S. Rossi, and W. F. Velicer. 1994. “The Transtheoretical Model of Change and HIV Prevention: A Review.” Health Education Quarterly 21 (4): 471–486.

- Reuber, H., and B. Muschalla. 2022. “Dietary Identity and Embitterment Among Vegans, Vegetarians and Omnivores.” Health Psychology and Behavioral Medicine 10 (1): 1038–1055. https://doi.org/10.1080/21642850.2022.2134870.

- Reuzé, A., C. Méjean, M. Carrère, L. Sirieix, N. Druesne-Pecollo, S. Péneau, M. Touvier, S. Hercberg, E. Kesse-Guyot, and B. Allès. 2022. “Rebalancing Meat and Legume Consumption: Change-Inducing Food Choice Motives and Associated Individual Characteristics in Non-Vegetarian Adults.” The International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity 19 (1): 112. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-022-01317-w.

- Rodan, D., and J. Mummery. 2019. “Animals Australia and the Challenges of Vegan Stereotyping.” M/C Journal 22 (2). https://doi.org/10.5204/mcj.1510.

- Rombach, M., D. Dean, F. Vriesekoop, W. de Koning, L. K. Aguiar, M. Anderson, et al. 2022. “Is Cultured Meat a Promising Consumer Alternative? Exploring Key Factors Determining consumer’s Willingness to Try, Buy and Pay a Premium for Cultured Meat.” Appetite 179:106307. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2022.106307.

- Rovetta, A. 2021. “Reliability of Google Trends: Analysis of the Limits and Potential of Web Infoveillance During COVID-19 Pandemic and for Future Research.” Frontiers in Research Metrics and Analytics 6. 25 May 2021, Sec. Scholarly Communication, https://doi.org/10.3389/frma.2021.670226.

- Russell, H. 2019. “How Might Vegan Food Fit into the Future of Hospital Catering?” British Journal of Healthcare Management 25 (5): 181–183. https://doi.org/10.12968/bjhc.2019.25.5.181.

- Salehi, G., E. M. Díaz, and R. Redondo. 2020. “Consumers’ Reaction to Following Vegan Diet (FVD): An Application of Transtheoretical Model (TM) and Precaution Adoption Process Model.” IAPNM 19th conference, León (Spain): University of León. July 2th-4th, 2020.

- Sapaico, R. (2022, May 29). The Growth of Vegan Restaurants in Europe, 2022. Happy Cow. https://www.happycow.net/blog/the-growth-of-vegan-restaurants-in-europe-2022/.

- Schenk, P., J. Rössel, and M. Scholz. 2018. “Motivations and Constraints of Meat Avoidance.” Sustainability 10 (11): 3858. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10113858.

- Stanley, S. K., C. Day, and P. M. Brown. 2023. “Masculinity Matters for Meat Consumption: An Examination of Self-Rated Gender Typicality, Meat Consumption, and Veg* Nism in Australian Men and Women.” Sex Roles 88 (3–4): 187–198. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-023-01346-0.

- Stoll-Kleemann, S., and U. J. Schmidt. 2017. “Reducing Meat Consumption in Developed and Transition Countries to Counter Climate Change and Biodiversity Loss: A Review of Influence Factors.” Regional Environmental Change 17 (5): 1261–1277. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-016-1057-5.

- Tuso, P. J., M. H. Ismail, B. P. Ha, and C. Bartolotto. 2013. “Nutritional Update for Physicians: Plant-Based diets. The Permanente Journal.” The Permanente Journal 17 (2): 61–66. https://doi.org/10.7812/TPP/12-085.

- UNEP. 2021. “Global Methane Assessment.” [ONLINE] https://wedocs.unep.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.11822/35917/GMA_ES.pdf.

- UNESCO. n. d. “Gastronomic Meal of the French. UNESCO » Culture » Intangible Heritage » Lists ».” Accessed October 26, 2022. https://ich.unesco.org/en/RL/gastronomic-meal-of-the-french-00437.

- Varela, P., G. Arvisenet, A. Gonera, K. S. Myhrer, V. Fifi, and D. Valentin. 2022. “Meat Replacer? No Thanks! The Clash Between Naturalness and Processing: An Explorative Study of the Perception of Plant-Based Foods.” Appetite 169:105793. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2021.105793.

- Villette, C., P. Vasseur, N. Lapidus, M. Debin, T. Hanslik, T. Blanchon, and L. Rossignol. 2022. “Vegetarian and Vegan Diets: Beliefs and Attitudes of General Practitioners and Pediatricians in France.” Nutrients 14 (15): 3101.

- Vogeler, C. S. 2019. “Market-Based Governance in Farm Animal Welfare—A Comparative Analysis of Public and Private Policies in Germany and France.” Animals 9 (5): 267. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani9050267.

- Weinrich, R. 2018. “Cross-Cultural Comparison Between German, French and Dutch Consumer Preferences for Meat Substitutes.” Sustainability 10 (6): 1819.

- Wolstenholme, E., V. Carfora, P. Catellani, W. Poortinga, and L. Whitmarsh. 2021. “Explaining Intention to Reduce Red and Processed Meat in the UK and Italy Using the Theory of Planned Behaviour, Meat-Eater Identity, and the Transtheoretical Model.” Appetite 166:105467. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2021.105467.

- Wyker, B. A., and K. K. Davison. 2010. “Behavioral Change Theories Can Inform the Prediction of Young Adults’ Adoption of a Plant-Based Diet.” Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior 42 (3): 168–177. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneb.2009.03.124.

- ZDNET. 2022. “What’s the Most Popular Web Browser in 2022? – ZDNET.” Accessed November 04, 2022. https://www.zdnet.com.

- Zhao, Y., and J. Zhang. 2017. “Consumer Health Information Seeking in Social Media: A Literature Review.” Health Information & Libraries Journal 34 (4): 268–283. https://doi.org/10.1111/hir.12192.