ABSTRACT

People with mild to moderate dementia often struggle with disorienting and alienating effects of the disease. Being attuned to spiritual sources of strength has been shown to be helpful in facing these challenges. In current dementia care practice and literature however, not enough attention is paid to fostering this type of connection. Our research offers a first overview of spiritual strength attunement in dementia. Results make clear how dementia impacts people spiritually, what the properties are of strength attunement and how professional caregivers foster this type of attunement with their clients. Insights are summarized in an integrated model.

KEYWORDS:

Introduction

Worldwide, more than 55 million people have dementia. This number is rapidly growing with 10 million cases per year (WHO, Citation2016). The disease is characterized by a progressive loss of cognitive functions such as memory, problem solving, attention, language, and reasoning (Palmer et al., Citation2020). Dementia is often divided into 3 stages: mild, moderate and severe. In the mild stage people can still function independently, in the moderate stage people require more help to take care of themselves and in the severe stage people require around the clock care (Arvanitakis et al., Citation2019). Especially in the mild to moderate stages of the disease people may be very aware of its disorienting and alienating effects. Living with dementia can then become a great struggle to live a meaningful life (Goodall, Citation2009).

It has repeatedly been shown that spirituality can be very important in enhancing the well-being of people with mild to moderate dementia (Bursell & Mayers, Citation2010; Toivonen et al., Citation2017). Hereby, the consensus definition of spirituality given by the European Association for Palliative Care (Nolan et al., Citation2011) has been referenced regularly: ‘Spirituality is the dynamic dimension of human life that relates to the way persons (individual and community) experience, express and/or seek meaning, purpose and transcendence, and the way they connect to the moment, to self, to others, to nature, to the significant and/or the sacred.’ A deep sense of connectedness to self, others, God or the world in general are therefore seen as important sources of strength and vitality for people (Palmer et al., Citation2022). Within the scientific literature however, very little is known about how to support people with mild to moderate dementia in connecting to their sources of spiritual strength (Britt et al., Citation2023; Palmer et al., Citation2020). This is unfortunate as there have been multiple signs that people’s needs for this type of support have not been met (Britt et al., Citation2023; Daly et al., Citation2019; Scott, Citation2016).

One reason for this literature gap is that professional caregivers who offer spiritual support, such as chaplains, are often not surveyed about their ways of working (Palmer et al., Citation2020). Another reason may be that these caregivers are not always fully aware of how their support works. Relevant knowledge can be difficult to articulate, especially if it goes beyond strictly religious sources (Ødbehr et al., Citation2017; Powers & Watson, Citation2011).

Because of the scale and impact dementia has, it is important to ascertain, analyze and disseminate more knowledge on how to help people get in touch with their spiritual (in the broadest sense) resources. This knowledge may help professional dementia caregivers to foster the well-being of people with mild to moderate dementia (Everett, Citation2015; Palmer et al., Citation2020). We therefore sought to investigate how professional caregivers help clients to attune to spiritual sources of strength. Hereby, attune was understood as becoming more closely connected to a spiritual source and attunement as being more closely connected. Specifically, we sought to answer three research questions:

How are sources of spiritual strength understood by professional dementia caregivers?

How do professional dementia caregivers understand the existential/spiritual impact of dementia on clients?

How do professional dementia caregivers help clients with mild to moderate dementia to attune to their sources of spiritual strength?

We not only sought to find answers to each research question, but also to gain an understanding of the relationship between the three.

Materials and methods

Design

We conducted qualitative research in the form of focus groups and single interviews with professional caregivers. Qualitative methods are particularly suited to explore the how and why of phenomena, as opposed to quantitative methods that focus more on how much something occurs (Patton, Citation2001). We chose a qualitative design because not much is known about our research subject. Focus groups allowed respondents to react to one another, and compare best practices and cases. Semi-structured interviews allowed us to explore aspects more in-depth with single respondents. This combination of qualitative methods gave us a balanced understanding of the practice of fostering spiritual strength attunement.

Setting and sampling

We recruited professional caregivers who provide care to people with dementia still living at home, as well as people living in nursing homes. In the Netherlands, people with mild to moderate dementia most often receive spiritual support in these settings (Alzheimer Nederland, Citation2017). Purposive sampling was used to identify caregivers that were experienced in helping people with mild to moderate dementia (Patton, Citation2001). Our selection criteria were: more than two years of experience caring for people with mild to moderate dementia, where working with sources of spiritual strength was an important aspect of delivered support.

Recruitment and participants

Spiritual strength experts were recruited through a campaign on the social media channels of the researchers and their university. In the beginning of the recruitment we focused exclusively on chaplains, as they explicitly deal with spiritual resourcing in the Netherlands (VGVZ, Citation2015). Gradually we included other caregivers, such as art therapists, if they met our selection criteria to get a more complete view. The characteristics of the 20 respondents are represented in .

Table 1. Characteristics of respondents.

Ethics

In our recruitment we explained the purpose and background of the research. Respondents willing to participate were then contacted via e-mail to check if they met our selection criteria. In that same email we explained our data-handling procedure. Respondents were given a week to decide if they wanted to participate, after which they provided informed consent via email. The University Medical Center ethics review board determined that formal approval of our study by the review board was not required according to the Dutch Medical Research Involving Human Subject Act (WMO, art.1b), as it did not fall under research concerning medically invasive interventions.

Data collection, handling and analysis

Data collection started on October 31 2022 and ended March 31 2023. The interview guide consisted of the three interview questions stated in the introduction. Follow up questions sought to elicit examples from practice and explore the how and why of given answers. Group discussions lasted 2 hours on average, interviews 1 hour. All discussions and interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed. The anonymized transcriptions, e-mail correspondence and research notes were stored in a secured database at the University.

Data were analyzed with thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006). The principle and second researcher reviewed the data independently and noted possible important themes. These themes were then shared and debated, after which an extended coding list was constructed. The transcripts were then coded in the analysis program AtlasTi. From these coded transcripts several subthemes emerged for each of the three research questions. The two researchers then discussed the relative importance of and relation between the subthemes with regard to the research questions. Based on this discussion an integrated model of spiritual strength attunement was constructed. This model was shared with respondents through a presentation. Feedback from the respondents was used to enhance the validity of the findings and further develop the model.

Results

In total, 3 group discussions and 4 one-on-one interviews were conducted. Below we present the most important themes from our research in the order of the research questions asked.

How are sources of spiritual strength understood by dementia caregivers?

Though respondents often remarked that a source of spiritual strength could be anything, they did have a clear idea about the properties or functions of spiritual strength attunement. Five functions or properties were named repeatedly.

Attunement is a base

Many caregivers understood connecting to a spiritual source of strength to be a foundational experience for people.

It’s about finding ground, grounding, finding a base. (Chaplain 10)

It has something to do with foundations, with roots. (Chaplain 6)

Such connections were seen to give people a solid grounding in life and function as starting points for life’s endeavors.

Attunement gives grip

Rootedness was also associated with the second property that was often named: a spiritual resource is also something to hold onto.

It is something that you can graft onto, where you can rest upon and find new strength and encouragement to deal with bad things that might happen to you. (Chaplain 1)

Spiritual resources are really something to grip tightly when times are tough. (Chaplain 9)

By turning to a spiritual resource in difficult life situations, people are able to reconnect with something essential in their existence and draw solace and courage to face their predicament.

Attunement sets things in motion

Next to the sturdy qualities of foundation and grip, spiritual resources were also seen as instigators of movement.

If suffering is a headwind, then a spiritual resource can be a wind in the sails. (Chaplain 1)

Its an energy giver that can set people in motion. (Chaplain 6)

Peoples sources of strength were reported not only to move them but flow through them like flows of energy

Attunement inspires

Spiritual sources were often reported to be sources of inspiration.

That which feeds and inspires me, gives enthusiasm and lifts me up and makes me want to really live … (Chaplain 12)

That from which people can get inspiration and zest. (Art therapist 2)

Attunement appears to motivate clients to live life to the fullest.

Physical manifestations of attunement

Many caregivers were also in agreement about the physical manifestation of spiritual strength attunement. They spoke of witnessing their clients rise up, straighten their bodily posture and become more alive.

You can see how they suddenly rise up and the eyes begin to sparkle. (Chaplain 3)

When the eyes begin to sparkle and the hands all of a sudden begin to gesture much more … (Social worker)

Connecting to spiritual strength thus radiated upwards and outwards in its manifestation.

They spring up, you see it in their demeanor, in their being engaged, that things are expressed naturally, coming from a deep place. (Chaplain 13)

How do dementia caregivers understand the existential/spiritual impact of dementia on clients?

Caregivers reported that dementia disconnected people from spiritual strength. One respondent provided a striking metaphor to summarize the total negative impact of dementia on people.

There is a great feeling of loss across all fields of experience. It starts small but becomes bigger and bigger. It is like you have fallen through the ice and you try to grasp the edges, but every time you grasp more seems to crumble away. (Chaplain 12)

This metaphor suggests a ‘sinking away’, through a brittle foundation, where efforts to find grip and footing are unsuccessful because what you are trying to hold onto keeps disintegrating. The perceived experience of clients was often characterized as a deep sense of loss and insecurity influencing three levels of experience.

The experience of being in the world

Various respondents reported that their clients felt insecure because familiar and trusted patterns of being in the world were disrupted.

People with dementia stand on very unreliable ground. Things start to become very unpredictable, for instance due to forgetting. That makes the foundation on which they stand very shaky. (Chaplain 12)

This loss of a relatively predictable and stable mode of being in the world was reported to regularly lead to confusion and fundamental questions concerning life and meaning.

“[In supportive conversations] it is often about: ‘We are searching for how, in god’s name, are we supposed to handle this. Now what? Where to? Why? How?’” (Chaplain 13)

The experience of being in social relations

A loss of stability and security was also seen to affect clients socially.

What comes up often is the theme that relating to the surrounding [social] world produces a lot of struggles: that other people just don’t really understand what clients are going through or that they try to ignore [the effects of dementia] or that they pretend to know what it’s like but really have no idea. (Chaplain 13)

Such struggles were reported to be very frustrating for clients because they made it difficult to truly share their experience of dementia with others. Some respondents also noted that clients could be inhibited in their sharing by the societal stigma surrounding dementia.

The images of [people with] dementia that are circulating in society at large are often very negative and that makes it really hard for clients to communicate honestly about what they are going through. (Chaplain 12)

Because of these experiences, clients frequently felt disconnected to others and alone in their predicament.

The experience of being yourself

Respondents also noted that their clients often retreated into themselves because they felt increasingly disconnected to the world and their social relations.

[As the disease progresses] you see clients become more and more quiet and despondent. (Chaplain 14)

As clients retreat into themselves there is inevitably a loss of self-worth.

“People start to feel worthless, to think to themselves: ‘I have become a useless person’”. (Chaplain 14)

The result could be a more apathetic state, whereby clients felt unable to continue being the way they were, yet confused about how to reposition themselves.

How do dementia caregivers help clients with mild to moderate dementia to attune to their sources of spiritual strength?

When exploring this question, various respondents started with a word of warning about this type of support. Whether or not they could actually help a client become more attuned to spiritual sources of strength was seen to be an uncertain process. There could be no guarantee that such attunement would take place.

“It’s not like you start with: ‘Okay let us now tune in to your sources of strength shall we’, that’s not how it works. You start a journey together and the road becomes apparent”. (Chaplain 2)

We must do everything we can to help people, but we cannot force a connection to sources of strength. (Chaplain 1)

Other caregivers also stated that spiritual strengths should not be seen as completely separate from clients’ experiences of loss. For them, attention to loss could open up a way to strengths and not fully acknowledging loss could be seen as a barrier for attunement.

Sources of strength are not available in a vacuum, you have to pay equal attention to a sense of loss, because otherwise the sources won’t become apparent. (Chaplain 6)

Despite these words of caution, it became apparent that caregivers did have trusted strategies to help clients connect with spiritual sources of strength. Analysis of these ways revealed three types of focus, which could be interrelated:

Evocative focus

In the process of developing rapport and getting to know clients, caregivers often remarked that they paid special attention to what would evoke emotional engagement in their clients.

It’s about exploring the lifeworld of the person who you find before you, with whom you set out on a journey, so you can explore what moves them. (Chaplain 2)

Surveying evocative intimate objects

Various respondents remarked that their caregiving experience had made them extra sensitive to what could be seen as possible symbols of significance.

“I always scan the home very rapidly. That is almost an immediate process. And then I almost always start asking questions like ‘Gee, what a beautiful painting you have hanging there what does it portray?’ So you try to create an environment in which something can spring to life”. (Chaplain 5)

Symbols rich with potential were reported to be: objects and images, sensibilities and preferences (for instants taste in texture, color and style), and words and phrases imbued with a high intensity of feeling. One caregiver referred to such symbols as clients’ “intimate objects”.

Evoking safe opportunities

Direct questioning was regularly deemed inappropriate however, since clients could be wary of opening up. Caregivers therefore reported that they would also frequently engage by sharing their own experiences or associations to provide clients with more secure opportunities to participate.

If I tell a story about something that I have just witnessed, or share associations that I have with a color that seems to be significant, then I am providing safe ground, as it were, for people, a kind of foundation to the conversation that might give someone a sense of security, something to latch onto. (Chaplain 12)

Through their way of interacting caregivers tried to evoke a safe space for their clients to start sharing their inner life. Caregivers thereby proactively sought to find and explore intimate objects to open up a field of potentiality. Hereby the bodily reaction of clients was reported to guide the way.

When the eyes start to light up, then I know, that’s where I need to be. (Art therapist 2)

The search for, and exploration of, evocative material could be hampered however by client’s sense of loss.

Affirmative focus

Multiple caregivers spoke of the importance of just being there for the client as an empathetic and supportive presence, especially when clients seemed to be in low spirits or agitated.

A lot of caregivers are there to do something; they are there for an intervention of sorts. But I don’t really have to do anything, I can just be with the person and listen to them, to whatever comes up in the moment and go with that. (Chaplain 9)

A dominant way to get in touch with clients under these circumstances was to get a feeling for the state of the other by paying close attention to body language and mood, before opening a line of conversation.

It could be that a person feels bad because they are gripped by a sense of loss. At that moment, look someone in the eyes and say: ‘it seems as though you are really feeling bad, what’s going on?’ Just be there with the other in that moment to touch and be touched. (Chaplain 1)

Affirming humanity and personhood

Various respondents spoke of this kind of contact as a social-emotional embrace, which could also affirm that the client matters.

“Clients can then experience: ‘there is someone who can see me, not the diagnosis’.” (Chaplain 12)

“That you take the time to look at people and put an arm around them, so they can feel ‘I am being seen’ and in that being seen they also feel safe in my experience”. (Music therapist)

These caregivers spoke of the sharing of suffering as a form of spiritual strength attunement. By being an empathetic and caring presence, caregivers gave clients something to hold on to in an insecure and confusing world; something that also allowed them to open up and express themselves more fully and deeply.

In those moments you could say that I am a source of strength for people in that they can be and express themselves. (Chaplain 11)

Rekindling affirming sustaining memories

Clients were regularly said to have lost touch with what had given them strength in the past, due to dementia’s effects. Breathing new life into these past experiences and celebrating them together was therefore seen as an important activity. Seeing clients more than once was fundamental in this regard, because it offered more time and opportunities to explore more fully the symbols that seemed to strike a chord with clients. Respondents also reported asking family members about meaningful aspects in the life of clients so they could bring them up if it seemed relevant.

I often ask about the early family situation of the client, what mother and father did, if they were a first, second or third child, things like that. (Art therapist 2)

Repeated visits were also reported to be important because of the unpredictability of what could trigger a life story at any given moment.

You can be talking about chestnuts or something, and then all of a sudden a story pops up about how they used to roast chestnuts when they where little and that it always gave them a warm and cozy feeling to be a part of that family event. (Chaplain 6)

Various caregivers spoke of getting closer to sources of strength with clients if the conversational tone shifted from small talk to a deeper opening up, where clients’ eyes started to shine. One caregiver spoke of such stories as “sustaining memories” that seemed to affirm a felt sense of meaning and personhood. Various caregivers spoke of their engagement in these interactions as a type of appreciative inquiry, wherein they sought to help articulate, highlight and reflect the personal significance of the stories told.

Through helping to find fitting words to express these experiences and appreciating what is special about them, these experiences acquire a halo or give extra power to someone. (Chaplain 6)

Though the emergence of such sustaining memories was not guaranteed, exploring certain types of experience increased the chance that they would arise. These included: what one cherishes most or is proud of, times and situations of carefree childhood and family life or being cared for or taking care of others.

Invocative focus

Because clients regularly, due to the effects of the disease, experienced a disenchanted world, caregivers also spoke of a third focus: one of invocation. That is, they often sought to help clients attune to something larger than themselves in the hope that a transcendent experience might occur.

It’s about finding a way to relate to something bigger. (Chaplain 10)

An experience wherein they can feel one with something higher or part of something larger. (Art therapist 1)

Invoking beauty

Various caregivers spoke of the power of beauty to move clients, especially when they were feeling disheartened with life in general. Nature was seen as particularly rich in ways to invoke a sense of beauty in the world’.

“This lady was feeling down because she didn’t find anything meaningful to do and she would get fixated on death. So I took her for a walk and started pointing out things in nature that I felt were quite beautiful: ‘look at this flower, how it blooms!’ or ‘what a beautiful bird’ and after a while she started to get into it too and said ‘nature can be so beautiful, so beautiful’ and she really started to become one with that feeling of beauty and with that you could see her regain strength”. (Chaplain 7)

This type of connection could also occur when appreciating art.

We organize groups visits to the museum, where we have a guide tell background stories about pieces of art, something to invoke the beauty of the work and then ask group members to share their reactions. And that can be wonderful because the emotional life of people with dementia seems to get stronger. (Chaplain 12)

Providing opportunities to experience beauty by guiding attention was reported to be particularly important for clients who had become less engaged in life. Because dementia tends to make feelings stronger, experiencing beauty could become very intense.

Invoking creative muses

Because clients were said to regularly feel constricted in expressing themselves, respondents spoke of the importance of trying to facilitate creative ways of expressing and sharing experience. Creative rituals, guiding templates for a type of creative self-expression, were reported to offer a way for active participation and attunement to a larger whole. Semi-choreographed dance, collage work or painting sessions for instance, were found to be fruitful here.

If you know how to facilitate movement in a special space, if you build it up with short movements first and then invite them to dance by tuning in to the music … They enjoy that tremendously, they experience a great sense of freedom to express themselves, they seem to be connected to a wellspring. (Art therapist 1)

Caregivers did emphasize, however, that a good balance needed to be found between preconceived forms and encouragement and appreciation of playfulness and improvisation. The key focus in these ritual invocations was one of playful exploration, whereby the sensory realm of experiences was foregrounded and where everything was possible.

[In collage-work] we explore the senses; picking up leaves, laying them in a certain way in the mandala, it’s sensory attentiveness in the looking, smelling and placing. (Art therapist 1)

It’s about trying things out in a playful manner … by going with that, allowing yourself to be spontaneous as well, then something new can spring to life. (Chaplain 11)

This playful or experimental exploration was also seen to be a key factor in invoking new inspirations with previously surveyed fascinations or passions.

I have one client who was an architect and he is fascinated by the influence of light. So we kind of developed a ritual where I would show him photographs that fascinated me in terms of lighting so I could learn to look at the picture through his eyes. We could also draw a scene together and compare our experiences whilst drawing. (Art therapist 2)

Receiving inspiration or becoming captivated by a wondrous new discovery was held to be elusive. But exploring intimate materials together in new and creative ways was also seen to be a focused appeal to the muses.

Invoking a higher power or truth

Lastly, respondents spoke of various spiritual rituals that could help clients to attune to something higher. Helping return to the habit of prayer was mentioned several times as a spiritual attunement for clients who felt disconnected.

I would definitely say recalling known prayers from long ago, such as a Hail Mary or an Our Father, as attuning to a source of strength, as well as new personal prayers wherein current worries and wishes can be articulated. (Chaplain 10)

By encouraging old and new ways to re-build relationships with God, chaplains hoped clients would be able to experience a sense of grace and communion. More than once, chaplains reported that such experience could occur quite suddenly, even with people with advanced moderate dementia, when participating in spiritual ritual.

Celebrating mass can be an important source of strength. [Religious] symbols, rituals and music speak to people at a deeper level, it touches them beyond the parts of the brain that are affected by dementia … it can happen that someone who is deep in the grips of sorrow at the start of the ceremony can become alive and lucid during the ceremony and positively beaming at the end. (Chaplain 9)

Here too a combination of a guided attention and sensory stimulation through (familiar) symbols and music could be a fertile ground for a transcendent experience. Such embodiment of the ceremony by clients was inspiring and moving for some chaplains. It could fill them too with a sense of spiritual wonder and strength. Some chaplains stated that it was the capacity for people with dementia to strongly connect to feelings that could help them attune so deeply.

I think for people with dementia the source of strength does not necessarily lie in the talk of God as such, but more in the deep feelings embedded in the songs and texts. (Chaplain 2)

Various respondents also spoke of the importance of incorporating meaningful themes or symbols in interaction with clients to allow an even more intimate invocation.

We did a spiritual celebration about the sea, a theme that was close to his heart. And in-between we listened to Taizé, a type of spiritual music and at a certain point he began to cry. I was a bit worried but I let it unfold. I could see that something was opening up deeply for him … I had seashells laid out on a table and afterwards we selected a few together, he did so with great care and was totally in the moment as he spoke about fatherhood and his desire to reconnect with his daughter. (Chaplain 10)

For these caregivers trying to help integrate “the universal with the personal” was seen as opening up the possibility for a higher consciousness or state of grace, which could move people to reconnect with what is truly important at this moment.

Discussion

The main goal of our research was to gain a better understanding of the practice of helping clients with mild to moderate dementia to attune to spiritual sources of strength. Whereby attune was understood as becoming more closely connected to a spiritual source. In our qualitative research we ascertained and analyzed caregivers’ understanding of how spiritual strengths work, how dementia impacts spiritual well-being and how to foster spiritual strength attunement. Since these insights are interrelated we have summarized and integrated these findings with the help of a model.

Main findings

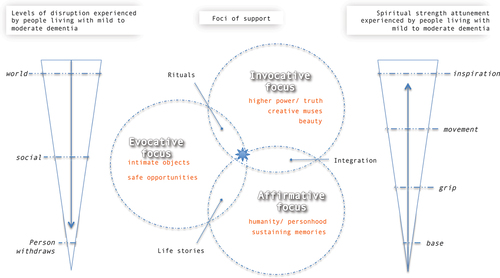

shows an integrated model of our main results. This model can be seen as topography of the spiritual strengths landscape for mild to moderate dementia.

Dementia disruptions and spiritual strengths attunement

The impact of dementia and the working properties of spiritual strength attunement are depicted on the left and right hand side of the topography respectively. Dementia was reported to cause a closing down or sinking away type of movement, whereby clients could be disrupted on three levels of experience. Due to cognitive challenges, clients could experience the world more as unstable and unpredictable, disrupting basic patterns of understanding. Sharing this type of experience with others was furthermore reported to be difficult because of others’ inability to relate and stigmatization. Due to these disruptions, clients often retreat into themselves, resulting in alienation and feeling downhearted.

Spiritual strength attunement was conversely reported to be an opening and uplifting type of movement. Herein, connecting to a source was reported to have four types of experience that seem to correspond with a physical transformation in clients. Attunement was said to offer an experiential base or grounding experience, give a sense of grip or something to hold onto, set things in motion through an energy flow and give inspiration and motivation to engage with something larger.

Foci of support

In-between these two movements, the three types of caregivers’ supportive focus are represented. Within the evocative focus, caregivers sought to gain a sense of the field of potential spiritual sources of clients. They did this by surveying clients’ intimate objects to locate important touchstones for people as possible gateways for deeper exploration. Alternately, caregivers could also share their own associations; experiences or appreciations surrounding such objects to avoid being over inquisitive and provide safe opportunities for clients to participate in the conversation. This focus was also seen as fruitful in (re-) establishing social rapport and trust. In terms of spiritual strength attunement, caregivers could be said to try find a first sense of what moves people and offer a sense of grip through their way of relating to them.

Within the affirmative focus, caregivers strove to help clients deeply reconnect with themselves. Clients overcome by sorrow were often seen to have lost touch with their own basic sense of humanity and personhood. By really looking clients in the eyes with compassion and embracing them in the depths of their sorrow, caregivers hoped to give rise to a feeling of mattering. By continuing to be an empathetic and caring presence for clients, caregivers also hoped to create a safe atmosphere wherein clients could open up and tell their life stories. Consequently, caregivers paid special attention to shifts in the conversation from small talk to recollections that seemed to stem from a deeper place and animated clients as they spoke. Through appreciative inquiry of these sustaining memories, weighing their value together and articulating their specialness, caregivers also sought to help clients rekindle them as a source of strength. In this focus caregivers thus sought to give clients something to hold on to and reflect with them sustaining on memories as the basis of their unique life and sense of personhood.

Within the invocative focus, caregivers sought to help clients more pro-actively (re-) connect to something larger than themselves. Supportive strategies were reported to be an appeal to something higher so that clients may experience transcendence. An appreciation of beauty, either through nature or art, could be a very moving experience, especially as clients had the capacity to experience emotions very intensely. Various creative forms, such as dance or painting were also seen to free up clients to express themselves in a non-cognitive way, by following creative muses. Herein, a good balance between guiding attention and non-judgmental room for playfulness and improvisation was said to be important. Helping clients get reacquainted with the practice of prayer supported attunement to a higher power or truth. Religious ceremonies could, through a combination of guided attention and sensory stimulation, also affect powerfully embodied transcendence. Through these forms and states of transcendence, the world could become a more enchanting place. Hereby clients could be moved by a higher energy and be called by a sense of inspiration.

The overlap of circles depicts inter-relational forms between foci. An evocative and affirmative focus could become interrelated through the sparking and sharing of life stories. An evocative and invocative focus could become interrelated through safe guiding rituals rich with symbolic value. An affirmative and invocative focus could become interrelated through an integration of the personal and universal. At the center, a symbol for a sparkle in the eyes is depicted, as this was the main touchstone for caregivers in their spiritual strength support.

Strengths and limitations

To our knowledge, this research presents a first overview of insights into spiritual strength attunement in mild to moderate dementia. This is significant as there are multiple signs that clients spiritual needs are not being adequately addressed (Britt et al., Citation2023; Daly et al., Citation2019; Scott, Citation2016). Through our research we have sought to learn from experts in the field about spiritual strength attunement in the broadest sense. We hope that our research will help to open up a new field of research that may greatly contribute to helping people living with dementia to attune to the vital and significant. It can also offer specialist and generalist caregivers a new frame of reference within which current practice can be better understood and further developed: a spiritual dimension of care that takes as its essential touchstone a sense of grounding enlivenment that lights up the eyes. Hereby it is important to note that, though these spiritual strength experiences occur in the sacred moment, repeated fostering of such experiences might also carry through beyond that moment. We see opportunities for different disciplines (for instance chaplaincy and art therapy, but also social work and neurology) to work together to deepen understanding and foster this way of support.

Our overview has limitations in that it is based on the experience of a limited amount of caregivers. Though we have spoken to caregivers with a combined experience of 250 years working with clients’ spiritual strengths, our analysis remains explorative in nature. More research needs to be done with a greater number of caregivers, with a greater variety of backgrounds, to further validate our results. With regard to the background of clients helped by the spiritual strength experts, we have not ascertained their ethnic or sexual identities. Increasing interest in the field of dementia research into the importance of these backgrounds in matching care to needs of persons living with dementia, makes clear that more research needs to be done in this regard (see for instance (Brijnath et al., Citation2022; Yeo & Gallagher-Thompson, Citation2006), To further validate the robustness of the findings across ethnic groups and sexual identities, follow up research therefore needs to actively recruit a diversity of clients. Furthermore, we have not spoken to clients directly, or observed interactions between caregivers and clients. In our follow up research we will seek to do so. Hereby we will seek to involve clients with the help of creative methods (Kara, Citation2022), such as drawing, collage work or installation building to further our understanding of spiritual strength attunement.

Conclusions

Our research presents first insights into a way of care that offers much potential for the wellbeing of people living with mild to moderate dementia. It is our hope that this “way of the sparkling eyes” can become more fully understood and disseminated in research and practice.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Alzheimer Nederland. (2017 July, 11). Cijfers en feiten over dementie.

- Arvanitakis, Z., Shah, R. C., & Bennett, D. A. (2019). Diagnosis and Management of Dementia: Review. JAMA - Journal of the American Medical Association, 322(16), 1589–1599. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2019.4782

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in pscyhology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Brijnath, B., Croy, S., Sabates, J., Thodis, A., Ellis, S., de Crespigny, F., … Temple, J. (2022). Including ethnic minorities in dementia research: Recommendations from a scoping review. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: Translational Research & Clinical Interventions, 8(1), 8(1. https://doi.org/10.1002/trc2.12222

- Britt, K. C., Boateng, A. C. O., Zhao, H., Ezeokonkwo, F. C., Federwitz, C., & Epps, F. (2023). Spiritual needs of older adults living with dementia: An integrative review. Healthcare (Switzerland), 11(9), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11091319

- Bursell, J., & Mayers, C. A. (2010). Spirituality within dementia care: Perceptions of health professionals. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 73(4), 144–151. https://doi.org/10.4276/030802210X12706313443866

- Daly, L., Fahey McCarthy, E., & Timmins, F. (2019). The experience of spirituality from the perspective of people living with dementia: A systematic review and meta-synthesis. Dementia (London, England), 18(2), 448–470. https://doi.org/10.1177/1471301216680425

- Everett, D. (2015). Forget me not: The spiritual care of people with alzheimer’s disease. Spiritual Care for Persons with Dementia: Fundamentals for Pastoral Practice, (December 2014), 77–88. https://doi.org/10.1300/J080v08n01

- Goodall, M. A. (2009). The evaluation of spiritual care in a dementia care setting. Dementia (London, England), 8(2), 167–183. https://doi.org/10.1177/1471301209103249

- Kara, H. (2022). Creative research methods in the social Sciences. Creative research methods in the social Sciences. https://doi.org/10.51952/9781447320258

- Nolan, S., Saltmarsh, P., & Leget, C. (2011). Spiritual care in palliative care: Working towards an EAPC task force spiritual. European Journal of Palliative Care, 18(Februari), 86–89. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-05005-4_7

- Ødbehr, L. S., Hauge, S., Danbolt, L. J., & Kvigne, K. (2017). Residents’ and caregivers’ views on spiritual care and their understanding of spiritual needs in persons with dementia: A meta-synthesis. Dementia (London, England), 16(7), 911–929. https://doi.org/10.1177/1471301215625013

- Palmer, J. A., Hilgeman, M., Balboni, T., Paasche-Orlow, S., Sullivan, J. L., & Bowers, B. J. (2022). The spiritual experience of dementia from the health care provider perspective: Implications for intervention. The Gerontologist, 62(4), 556–567. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnab134

- Palmer, J. A., Smith, A. M., Paasche-Orlow, R. S., & Fitchett, G. (2020). Research literature on the intersection of dementia, spirituality, and palliative care: A scoping review. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 60(1), 116–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2019.12.369

- Patton, M. (2001). Qualitative research and evaluation methods. US Patent 2,561, 882 - 806 Pages. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8721.2007.00506.x

- Powers, B. A., & Watson, N. M. (2011). Spiritual nurturance and support for nursing home residents with dementia. Dementia (London, England), 10(1), 59–80. https://doi.org/10.1177/1471301210392980

- Scott, H. (2016). The importance of spirituality for people living with dementia. Nursing Standard (Royal College of Nursing (Great Britain): 1987), 30(25), 41–50. https://doi.org/10.7748/ns.30.25.41.s47

- Toivonen, K., Charalambous, A., & Suhonen, R. (2017). Supporting spirituality in the care of older people living with dementia: A hermeneutic phenomenological inquiry into nurses’ experiences. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, No-Specified. http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=psyc13a&NEWS=N&AN=2017-39938-001

- VGVZ. (2015). Beroepsstandaard geestelijk verzorger, 1–46. https://vgvz.nl/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/Beroepsstandaard-2015.pdf.

- WHO. (2016). WHO Factsheet - Dementia.

- Yeo, G., & Gallagher-Thompson, D. (Ed.). (2006). Ethnicity and the dementias (Second ed.). Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.