Introduction

In crowdfunding, individuals or small enterprises seek to attract funds for an innovative project by collecting small amounts of capital from a large number of people. In the last decade, it has become a popular form of fundraising that helped thousands of early stage entrepreneurs and ordinary people to realise their business idea (Mollick, Citation2014). The level of crowdfunding activity grew massively with the advent of the Internet, as project founders can nowadays easily reach a vast public by setting a campaign online. Between 2009 and 2021, over four billion dollars have been pledged on Kickstarter, one of the world’s most popular crowdfunding websites (Kickstarter, Citation2021a). In uploading a project on Kickstarter or similar venues, founders specify a funding target that must be met for the project to be successful and design a multimodal campaign (including video, images and written text) in which they pitch their project to an audience of potential backers.

Crowdfunding campaigns, not very different from other fundraising or non-financial campaigns (e.g., political campaigns), constitute a genre of strategic communication, particularly when the latter is understood as communication related to the very existence and survival of a corporate entityFootnote1 (Hallahan et al., Citation2007; Zerfass et al., Citation2018). Indeed, the business project for which funding is sought can be set up only if it gains legitimacy (Frydrych et al., Citation2016) from funders, which in turn depends on the founders’ ability to communicate their project in a persuasive way. As this study will show more in detail, the discursive content of a crowdfunding campaign involves some of the typical “ingredients” of strategic communication, like, for example, the legitimation of societal needs, the construction of reputation and of a trustworthy image, the connection between the promoted products/services and the expectations of customers and other stakeholders, the exposition of plans for the achievement of business goals, etc. In other words, crowdfunding campaigns are persuasion endeavours that cannot be fulfilled by merely routinised and operational messaging, requiring instead the adoption a strategic approach to communication, which includes the deployment of micro-level communication strategies (Palmieri & Mazzali-Lurati, Citation2021; Van Werven et al., Citation2015).

The need for a strategic approach when communicating a crowdfunding project is implicitly demonstrated by the fact that many campaigns fail to obtain their funding goal. For example, Kickstarter has currently a 38.76% acceptance rate (www.kickstarter.com/help/stats) and it includes overly successful campaigns as well as very unsuccessful ones. The chances of losing a crowdfunding bid are not slim as largely unknown entities with little, if any, track record and prior reputation have to obtain resources in a highly competitive environment where thousands of projects are proposed every year.

It is, therefore, not surprising that the identification of the factors explaining the outcome of crowdfunding campaigns represents an important object of academic research. Scholars in management and linguistic disciplines have investigated the communicative drivers of the success of a crowdfunding campaign, looking at how founders strategically mobilise various discursive resources to convince the crowd to fund their project (Chen et al., Citation2016; Mitra & Gilbert, Citation2014). According to Frydrych, Bock and Kinder, “crowdfunding success is based less on platform-specific functions, and primarily associated with the creation of a convincing narrative” (Frydrych et al., Citation2016, p. 102, our emphasis). The narrative perspective they take is common to several management studies in entrepreneurial pitching that highlight how funders use storytelling to give their project a sense of legitimacy and distinctiveness (Martens et al., Citation2007; Mollick, Citation2014). While the centrality of compelling narratives to the success of crowdfunding campaigns is explicitly acknowledged, the linguistic-discursive ‘ingredients’ making a pitching narrative compelling remain vaguely defined and largely unexplained. Frydrych et al. (Citation2016), for example, present narratives as strategic tools that, going beyond financial calculation, enable sense-making, coherence and legitimacy, but do not go deeper in examining how such narrative tools operate from a discursive-linguistic point of view. This is due also to the quantitative methods adopted in most narrative studies of crowdfunding pitching which prevent from capturing the micro-level aspects of these instances of strategic communication.Footnote2 A qualitative investigation of the structure of crowdfunding stories has been undertaken by Manning and Bejarano (Citation2017), who identify two main distinct narrative styles, namely ’ongoing journey’ and ’results-in-progress’. Their approach focuses on the temporal dimension of the entrepreneurial story, while neglecting the rhetorical and logical aspects that characterise the linguistic content of the (crowdfunding) pitch.

Inspired by recent research on the micro-rhetoric of investor pitching (Van Werven et al., Citation2015, Citation2019) and by theories of rhetorical entrepreneurship and rhetorical legitimacy (Harmon et al., Citation2015), this article elaborates on the hypothesis that a compelling crowdfunding narrative is such when it conveys sound and effective argumentation (Jacobs, Citation2006; Van Eemeren, Citation2010). This happens when founders succeed in justifying their entrepreneurial proposal with reasons that effectively address all issues potentially raised by the crowd, thereby creating a convincing case for funding. To do so, funders cannot limit themselves to achieve dialectical soundness, which consists in the rational justification of claims with logically valid arguments based on shared premises. They also need to deploy discourse strategies that achieve rhetorical effectiveness by favouring the understanding and eventual acceptance of arguments as well as compliance with cultural, cognitive, institutional and other situational constraints. Indeed, rhetorical argumentation strategically combines critical thinking and reasoned discussion with interpersonal, emotional and socio-cultural factors inhering any form of contextualised communicative interactions (Rigotti & Rocci, Citation2006; Van Eemeren, Citation2010). The reconciliation of logical-dialectical and rhetorical-relational aspects is textually accomplished through appeals to ethos, logos and pathos, which refer to the speaker’s trustworthiness, the message’s cogency and the audience’s perspective, respectively.

The goal of this article is to highlight and investigate the argumentative features of the crowdfunding pitch, including the dialectical and the rhetorical aspects, with the ultimate aim of identifying those argumentative strategies that are more likely to explain the (lack of) success of a crowdfunding campaign. Two main gaps in existing related research are addressed: (1) while a few scholars have looked at the use of rhetorical argumentation appeals (i.e., ethos, logos and pathos) in crowdfunding presentations (Majumdar & Bose, Citation2018; Tirdatov, Citation2014), the argumentative dynamics specific to this pitching context have been scarcely investigated. As a consequence, the argumentative nature of crowdfunding narratives remains under recognised; (2) the majority of studies aimed at identifying linguistic and rhetorical factors of success are based on the analysis of funded projects only, while our dataset includes both successful and unsuccessful crowdfunding campaigns.

The results of this study demonstrate the argumentative nature of crowdfunding pitches and highlight a variety of argumentative patterns at the level of ethos, logos and pathos which reflect the founders’ effort to construct a dialectically reasonable and rhetorically effective presentation of their project. The study reveals crucial differences in argumentative patterns between successful and unsuccessful campaigns based on which future quantitative studies on larger datasets can be accomplished.

The article is structured as follows: in the next section, an argumentative model of the crowdfunding pitch is built by integrating existing models of entrepreneurial pitching with argumentation theories. Subsequently, the methodology underlying our empirical study is explained, followed by a section dedicated to the presentation and discussion of results. The final section concludes the article with a summary of the key findings and with suggestions for future research as well as implications for practitioners.

Theoretical framework: the crowdfunding pitch as an argument

Entrepreneurial pitching: narrative or argument?

Crowdfunding campaigns include quantitative information (e.g., the funding target, the rewards or returns promised to the backers etc.) and qualitative information, in particular the video description of the project in which founders pitch their idea in front of an audience of potential funders (backers). Generally speaking, an entrepreneurial pitch – aka investor pitch – is a relatively short message (written or spoken) in which founders of a new business activity or product promote their idea in the hope of persuading backers to finance the advertised project. A pitch can occur in different contexts, including a crowdfunding website, in which case it can be referred to more specifically as crowdfunding pitch (CP).

Studies interested in the discursive content of entrepreneurial pitches have examined the thematic and compositional structure of this genre of entrepreneurial communication as well as the different strategies deployed therein. The structural analysis of the pitch identifies the typical sections it is composed of, specifying, for each section, both thematic content and intended communicative function. Daly and Davy (Citation2016), who examine the structure of a non-crowdfunding pitch, identify parts with an interactional or relational aim (e.g., greetings, thanking the audience, recapitulating) and parts focusing on the presentation of the pitched project, which include information about the founder, the requested funding, the future plans, the characteristics of the product, and the target customers (p. 125). To our best knowledge, no study exists on the compositional and thematic structure of CPs, although Manning and Bejarano remark that “[crowdfunding] Videos typically start with a description of a need, then summarise how the projects started and what has been achieved, followed by future plans; they typically end with a direct request for support from the viewers” (Manning & Bejarano, Citation2017, p. 199, emphasis added).

Studies looking at the pitching strategies deployed by founders in their project descriptions can be divided into three main groups corresponding to different conceptual and analytical perspectives to entrepreneurial communication: (1) narrative and storytelling (e.g., Frydrych et al., Citation2016; Manning & Bejarano, Citation2017; Martens et al., Citation2007); (2) persuasive linguistic techniques (e.g., Chen et al., Citation2016; Majumdar & Bose, Citation2018; Mitra & Gilbert, Citation2014; Parhankangas & Renko, Citation2017; Xiang et al., Citation2019); (3) rhetorical argumentation strategies, such as ethos, logos, and pathos appeals (e.g., Tirdatov, Citation2014; Van Werven et al., Citation2019). Taking this third perspective, the present article conceives of CPs as rhetorical texts in which argumentative strategies play a predominant role in the founder’s attempt to persuade the crowd and garner their financial support (see Van Werven et al., Citation2015).

What distinguishes argumentation from other modes of persuasive communication is the centrality of reasons based on which arguers justify a claim (or standpoint) in front of the critical audience they are trying to persuade (Rigotti & Morasso, Citation2009; Van Eemeren & Grootendorst, Citation2004). Ever since Antiquity, argumentation has been understood as a communicative activity that simultaneously involves a dialectical and a rhetorical concern (Van Eemeren, Citation2010). The dialectical dimension reflects the arguers’ commitment to critically discussFootnote3 the advanced claims and reasons starting from shared premises and commonly established interactional and dialogical procedures. The rhetorical dimension corresponds to the arguer’s effort to communicate reasons effectively by using a variety of lexical, stylistic, textual and, when relevant, audio-visual and multimodal resources that make the arguments situationally appropriate and, as such, more likely to obtain persuasion.

Thus defined, argumentation features both differences and commonalities with narratives or stories. Simply put: argumentation presupposes the existence of an issue and entails the attempt to resolve this issue with dialectically sound and rhetorically effective reasons; storytelling (or narrative) has more to do with the creative and retrospective reconstruction and sharing of facts and events (see Tindale, Citation2017), which in organisational contexts is often associated to sense-making processes.Footnote4

A crucial starting point for narrative approaches to crowdfunding discourse is that the entailed decision-making process is not based on financial modelling, but rather on shared perceptions of value, which are “socially constructed within an entrepreneurial context, rather than financially calculated in an investment context” and conform “to a heuristic of narrative coherence” (Frydrych et al., Citation2016, p. 104). Within an argumentative perspective, the CP is best understood as a response to a rhetorical situation (Bitzer, Citation1968), and more specifically an argumentative situation (Palmieri, Citation2014), where the exigence of getting the project funded depends upon persuading the crowd with arguments that are able to resolve the different issues entailed by the founder’s proposal (see next section). However, there are also important points of convergence between argumentation and narrative that should not be overlooked (Olson, Citation2017).

On the one hand, stories can and often do contain what, as a matter of facts, are arguments (see the concept of narrative arguments in Tindale, Citation2017): from corporate websites where founders recall the decision-making process that led to set the business up, to fairy tales in which the novelist describes the reasoning made by a character confronted with a difficult choice. Moreover, even unargued stories can fulfil an argumentative function by creating a sense of plausibility (Olmos, Citation2013). For example, the accuracy and realism with which a news story reports an event can be taken as implicit evidence of its truth.Footnote5

On the other hand, argumentative texts can include narrative elements, as it was clearly acknowledged already in the earliest studies of argumentation within Classical Rhetoric. Within the well-known canonical model of rhetorical speech, expounded in the Rhetorica ad Herennium (Cicero, Citation1954), narratio represents a crucial part of a persuasive argumentative speech in which the relevant facts of the case under the discussion are strategically recalled and reconstructed. The subsequent stages devoted to the elaboration of arguments (confirmatio) and counter-arguments (refutatio) are largely based on the premises established in the narratio. As this study shows, CPs work in a very similar way: while their core content consists in the communication of rhetorical arguments in support of the campaign, narration can be deployed strategically to fulfil a dialectical or a rhetorical function.

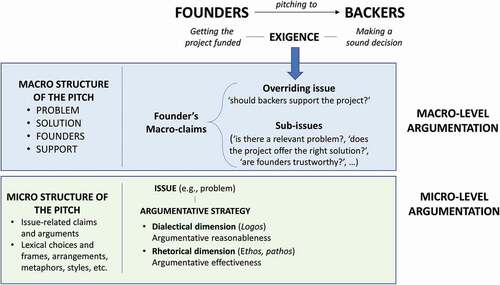

The argumentative structure of the crowdfunding pitch

The first crucial step towards an argumentative account of the CP is to recognise that it is constituted by a set of issuesFootnote6 that reflect the critical questions implicitly raised by the crowd-audience. Any CP represents the response to an exigence-related overriding issue, which could be rendered through the following question: ‘should we (i.e. the crowd) support the pitched project?’ From a dialectical point of view, founders hold an affirmative claim on this issue (i.e., ‘you (the crowd) should support our project’) and need to offer compelling reasons for such a claim in order to eventually convince the crowd to pledge money to the campaign. To do so, founders have to discuss a set of sub-issues regarding more specific aspects of the campaign such as those identified in previous studies on entrepreneurial pitching (see Van Werven et al., Citation2019): the existence of a problem or gap in the market; the originality and effectiveness of the proposed product; the experience and trustworthiness of the founders; etc.

In other words, an argumentative framing of the CP considers the content of its thematic part – or at least, of some of them – as functional to resolving the issues entailed by the campaign. The constellation of issue-related claims put forward by founders gives rise to a macro-level argumentation. The logical connection between the different thematic parts of the CP, which constitutes the macro-structure of a text or speech (see Van Dijk, Citation1988), builds up the macro-argument governing the logic of the whole CP. To illustrate how this works, let us briefly examine an excerpt from one the campaigns included in our dataset (see “Methodology” section), namely Suvie, a kitchen robot invented by founders Robyn Liss and Kevin Incorvia (www.suvie.com):

As shows, this pitch starts with the description of a problem (i.e., the lack of time for preparing good food) to present the product as the ideal solution to such a problem. It is clearly assumed that a potential funder would wonder why this kitchen robot is needed, what problem is there that requires Suvie as its solution. Subsequently, the description of the product in its features and advantages evidently represents a response to questions regarding the quality of the product and its actual ability to resolve the problem previously identified. Moreover, the founders briefly talk about themselves to highlight their previous professional experience and boost their credibility in the eyes of the funders who may ask themselves whether the campaigners are trustworthy or not. Finally, the pitch tackles the ‘support’ theme, which coincides with the overriding issue (‘should the crowd support the project?’) and the corresponding founders’ main claim (‘you should support our project’).

Table 1. An example of macro-level argumentation in a crowdfunding pitch: Suvie

The responses to all these questions are implicit macro-claims (see Van Werven et al., Citation2019) which, once taken together, co-construct as sort of macro-level logic that could be formulated through the following maxim (Rigotti & Greco, Citation2019): ‘If project X is the best solution to an important problem and is proposed by trustworthy people, X should be supported’.

Within each thematic part of the pitch, the implicit macro-claims are supported and elaborated with further reasons that correspond to the micro-level argumentation. In Suvie’s case, for example, the problem-related claim (“Providing fresh, nutritious, flavourful meals for our families has become a challenge”) is justified with arguments that point to lack of time (“The time and energy it takes to shop, prep, cook and clean … we just don’t have it”) due to an ever-busier life (“Life is busier than ever”). Similarly, the trustworthiness of the founders is supported by reference to their former professional experience (“a former Apple engineer”; “founder of Review.com”).

The micro-level argumentation of the pitch strategically combines dialectical moves – i.e., logical structures of claims and reasons responding to the audience’s critical questions – and rhetorical moves, oriented at effectiveness.Footnote7 illustrates the argumentative structure of CP in its macro and the micro levels.

Methodology

The proposed study is guided by the following three questions that have been formulated on the basis of the literature review and conceptual framework elaborated in the previous sections: (1) To what extent is the content of crowdfunding campaigns argumentative? (2) What patterns of argumentative strategy characterise a crowdfunding pitch? (3) How do these patterns differ between successful and unsuccessful campaigns?

In order to answer these questions, a qualitative analysis of a relatively small corpus of crowdfunding project descriptions published on Kickstarter has been undertaken. This section of the article explains the process of data selection and collection and the analytic framework and procedure by which the corpus has been examined.

Dataset selection and collection

Launched in 2009, Kickstarter is one of the most popular crowdfunding websites, with over 5 billion dollars pledged on the platform as of end of April 2021 (Kickstarter, Citation2021a). Kickstarter is a reward-based crowdfunding platform, which means that the funders of a successful project receive a non-financial return reward in exchange for their pledge, typically in the form of a discounted price on the advertised product. The dataset includes 15 successful and 15 unsuccessful Kickstarter campaigns launched in the 2018–2019 period and belonging to one of the following three sub-categories: Fashion (10 projects), Food (10 projects) and Design (10 projects). The projects were selected to obtain a purposeful sample including campaigns with different outcomes and belonging to different sub-categories to limit sector-specific biases. The sample size was motivated by the purpose of the study, which was not to draw statistically significant generalisations, but to inductively identify (see Manning & Bejarano, Citation2017) a variety of meaningful micro-level argumentative patterns.

provides an overview ofthe projects included in the corpus, including the URL where theycan be found.

Table 2. Crowdfunding campaigns included in the corpus

The verbal component of each video description was manually transcribed and saved in txt format to make it readable by the annotation tool that we used as explained in the next sub-section.

Coding schemes and corpus annotation

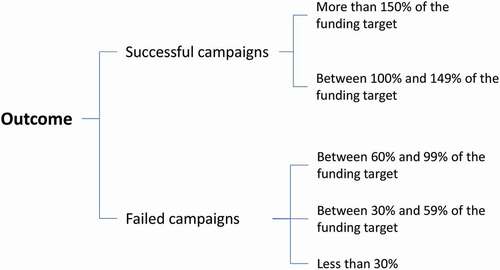

A qualitative manual analysis of all 30 transcripts was performed with the support of the annotation software UAM Corpus Tool (O’Donnell, Citation2008), freely available at http://www.corpustool.com/. This tool enables to upload texts, create multiple coding schemes (layers) to annotate them, search and explore the annotated textual segments, perform basic statistical analysis, and visualise results. On UAM CT, layers consist in a set of hierarchically structured features which can be applied either to the whole text (document-level layers) or to selected portions of it (segment-level layers). For the present study, one document-level layer (‘Outcome’) and four segment-level layers (‘Macro-themes’; ‘Ethos appeals’; ‘Pathos appeals; ‘Logos appeals’) were created.

For ‘Outcome’, the successful vs unsuccessful distinction was further specified into different degrees of success or failure depending on what percentage of funding target was eventually pledged (see ).

In order to design the segment-level layers, a two-step process was followed: (1) generic features were defined; based on prior literature and the theoretical framework explained in the previous section; (2) these features guided the initial exploration of the corpus aimed at inductively refine the layers with new and more specific features until a satisfactory and exhaustive list of categories was obtained. All features within the entire coding scheme were described with a gloss that was embedded into UAM CT to help the human annotator with the interpretation of the selected segment and with the choice of the most appropriate feature.

For the ‘Macro-theme’ layer, which is aimed at capturing the macro-level argumentation of the pitch, a first level of features based on the four sets of issues discussed in the theoretical section was defined, namely ‘problem’, ‘project’, ‘founders’ and ‘support’. For each of them, more specific features were identified, for instance, the project category was further specified into ‘origin of the idea’, ‘project features’, project advantages’, target customers’, ‘current state’ and ‘next steps’ (). reports, for each feature, its description and an example.

Table 3. Coding scheme for macro-theme layer

The layers ‘Ethos’, ‘Pathos’ and ‘Logos’ are meant to capture the micro-level argumentation of the pitch. For each theme, the same analytic-inductive procedure as for ‘macro-theme’ was adopted. The resulting coding schemes are explained and exemplified in .

Table 4. Explanations and examples for layer ethos

Table 5. Explanations and examples for layer pathos

Table 6. Explanations and examples for layer logos

Ethos appeals refers to attempt to construct the speaker’s credibility based on perceptions of competence, intelligence, virtue (integrity) and benevolence (see Schoorman et al., Citation2007). Logos is manifested by the advancement of explicit argumentative justifications of claims and is often signalled by logical connectives of support (e.g., because, therefore, so) or refutation (e.g., but, however, etc.). Pathos refers to the use of an audience-oriented and emotive language that demonstrates the speaker’s intention to create communion and empathy with the readers/listeners.

The multi-level annotation scheme was applied to the whole dataset by annotating each individual sentence against all four segment-level layers (Macro-theme, Ethos, Pathos and Logos). Then, patterns of argumentative strategies based on the most frequent annotated features were identified.

In order to ensure that the segmentation of the transcripts was the same across all four layers, the first step was to annotate all documents according to the ‘Macro-theme’ layer. This means that the human annotators had to decide what string of text to select only once, when annotating the macro-themes. Subsequently, the automatic coding function of UAM CT was used in order to reproduce the same segmentation for the Ethos, Pathos and Logos layers. As a result, every single segment selected by the annotator was separately analysed four times in relation to the macro-theme that is discussed, and to the presence and type of ethos, logos and pathos appeals.

The authors of this article worked together over a period of approximately two months to construct the layers, test them on the corpus and formulate the features’ descriptions. These were incorporated into UAM CT as glosses and worked as a coding book for the annotators. Subsequently, two students from the University of Liverpool with previous experience with text analysis were hired to work as independent annotators of the whole dataset. The students received training over multiple sessions devoted to the basics of argumentation theory and discourse analysis and to introducing them to UAM CT, the coding scheme (layers and features) and the coding book (glosses). Based on a sub-set of project descriptions, the two students worked separately on the same documents to exercise their annotation skills and familiarise themselves with the layers. Weekly meetings with the first author of this article were regularly held in order to verify the quality of their analysis and discuss dubious cases. Once a satisfactory level of mutual understanding was achieved, each student analysed half of the corpus (15 project descriptions) by annotating the transcripts for all five layers. Weekly meetings were held in order to review and verify the progress of the annotation. The entire process took approximately 8 weeks. Then, the ‘Search’ and the ‘Statistics’ functions of UAM CT were used to explore the analysis and identity patters of argumentative strategies that were relevant for the research questions.

Results of the analysis and findings

Macro-level argumentative patterns

reports the frequency of macro-theme segments across the entire corpus. A total of 602 segments were annotated. 68.77% of these segments belong to ‘Project’, followed by ‘Request to funders’ (13.29%), ‘Founder’ (11.63%) and ‘Problem’ (6.31%).

Table 7. Macro-themes

Project-related information dominate the pitch

The first evident finding from the analysis is that project-related themes represent the dominant part of the pitch, with an emphasis on the descriptions of the features (23.42%) and advantages (23.26%) of the product. An important part of the pitch is dedicated to the ‘Origin of the idea’ (10.80%), which are discussed more in details later. ‘Project’ is also the only macro-theme that is present in all 30 campaigns of the corpus, suggesting that this is a necessary component of any CP. There are at least two plausible explanations for such predominance: (1) the primary audience of a CP is made of people with a pre-existing interest for the type of product advertised or at least for the Kickstarter category it belongs to. This entails, for instance, less urgency to insist on the problem that is meant to be solved or to explain who the target users would be. Backers are keener and probably curious to understand how the product works and are more interested in seeing what benefits they would get from using it; (2) Founders are most of the time novice entrepreneurs with no prior reputation which means they do not have a lot to say about their profile that could give the pitch a sense of persuasiveness. As the analysis of ethos appeals will suggest, founders tend to signal their trustworthiness rather than disclosing it and using it as an explicit argument for the funding request.

Requests to join rather than to fund the project

The second most frequent macro-theme (13.29%) is ‘Request to funders’, which always occupies the very last sentences of the pitch, thus working as the logical conclusion of what was just expounded on the project. Indeed, as suggested in the “Theoretical framework” section, this macro-theme coincides with the overriding claim of the pitch. The majority of these features are ‘requests to join’ (example [i–ii]) rather than ‘requests to fund’ (ex. [iii]), which probably reflects the characteristics of the Kickstarter platform:

“So come join us at Better Half Brewing for some great beer” (Better Half Brewing)

“Now we are ready to bring Suvie to you, and we are looking for your support to help us revolutionize dinner together. The future is here. Join the Suvie dinner revolution today.” (Suvie)

“yeah, absolutely. In the words of little rascals, “we need your money!” Thanks!” (Cereal Milk Ice Cream)

Backers are would-be users of the product and, therefore, they are framed as members of a community. What is proposed to them is not an investment, but the opportunity to share an experience through the product. Backers are not promised rewards for a mere financial support, but for the opportunity to co-realise an innovative product from which they will benefit too. Interestingly, even ‘requests to fund’ are often framed as generic requests for help or support (ex. [iv–v]), without an explicit mention of money and leaving the financial consideration often implicit. It seems that founders do not want the financial aspects of the campaign to be foregrounded over the opportunity to build a community of users:

“For this reason, we need your help” (Sensolatino).

“Thanks for backing our campaign” (Zen).

In some cases, the expression of the support’s request is preceded by the ‘use of funds’ macro-theme, i.e. a short explanation of how the pledged funds will be employed. By this move, the founders empower the backers by showing what they would help accomplish with their positive funding decision:

“We are now ready to go, but we need your help to make these designs become reality” (Tilia Rose Swim).

“No business can run without a sign, so your donations will help my dream become a reality that you can also enjoy” (Just What I kneaded).

Founders’ profile is not a strategic resource

Sentences thematising the profile of the founders themselves are not very frequent (11.63%). This can be explained by the relatively low level of prior experience Kickstarter founders have, which prevents them from using their profile as a strategic resource supporting the funding request. Many of these segments include greetings and self-introduction (ex. [viii]), simple descriptions of the company’s core business (ex. [ix]), or the founder’s professional background [ex. [x]):

“Oh hi Kickstarter community, I’m Ali. And I’m Jack Burns. And we are the co-founders of Genusee” (Genusee).

“And we are ‘Yes Plz’, a coffee company that aims to democratize great coffee” (Yes Plz).

“Hi, I’m Kevin, a former Apple engineer” (Suvie).

Problem: a hidden claim?

Several campaigns do not contain segments covering the problem macro-theme, suggesting that some founders have not developed their project as a solution to a societal need or gap in the market. However, a closer inspection into the content of the macro-themes suggests that problem statements are much more frequent than what may appear at a first glance, as they are incorporated in other macro-themes, in particular the one called ‘Origin of the idea’. As example [xi] illustrates, these parts are expressed in a narrative style and consist in the founders recollecting the circumstances in which they came out with the project idea and decided to develop the product.

“Two years ago, we set out to design a revolutionary cooking appliance that was beyond anything on the market. We were tired of take out and delivery, and we found that traditional meal kits took too long to prep and clean up. We knew there is a better way, and that’s when we invented Suvie, the smart, refrigerated, multi-zone cooker that works with meals of fresh, raw, ready-to-cook ingredients.” (Suvie)

These short narratives describe the problem as it was personally experienced by the founders and reconstruct the reasoning path that led them to develop the project. This way of presenting the problem fulfils a trust-building rhetorical strategy, as better explained in the ‘Ethos’ section below.

There are also campaigns in which the project idea does not originate from the identification of a problem but rather from something that worked well in past:

“Yeah, I think we knew we were onto something special then, and that’s when Cereal Milk Ice cream was born” (Cereal Milk Ice Cream).

“Starting out as a powerful flashlight and a beautifully machined match store, we quickly realized a potential of LiteCans” (LiteCans).

Pitching strategies: 3 macro-level argumentative patterns

Based on how the problem issue is tackled, we can distinguish three main patterns of macro-argumentation strategies: (1) societal problem-solution; (2) personal problem-solution; (3) desire-project.

The first one is exemplified by the Suvie campaign discussed beforehand. The project is framed as the solution to a societal problem, that is a problem that the crowd can perceive as widespread and shared amongst a community or market. The overarching logic of this macro-pattern can be rendered as “If project X is a good solution to an important societal problem, X should be supported”.

The second pattern is similar to the first one except that the extent of the problem is limited to the founder’s personal situation. For instance, in Better Half Brewery, the founders mention an issue they have (no time available to visit breweries due to increasing family commitments), without explaining how this problem can pertain to a wider range of people. From a backer’s point of view, supporting their initiative would count more as helping the founders solve their own problem, rather than contributing to achieve shared needs and goals. The underlying logical principle in this case would be something like “If a project X helps the founders, X should be supported”.

The third pattern does not start from the existence of a problematic situation but from the identification of an intrinsically desirable initiative or product which requires funding to be realised. For example, Ketofest 2019 is a food festival that successfully took place in previous years and that requires funding to be organised again. The logic here is: “If project X represents something desirable, X should be supported”.

Ethos

In general, the number of segments using an ethos appeal (n = 270, 44.9%) is lower than the number of segments without ethos (n = 332, 55.1%). Out of 270 occurrences of ethos, ‘Integrity’ is the most frequent appeal (n = 105, 38.9%), followed by ‘ability’ (n = 71, 26.3%), ‘intelligence’ (n = 54, 20%) and ‘benevolence’ (n = 40, 14.8%).

The ethos-building function of ‘origin of the idea’

Ethos appeals play an important strategic function as part of the ‘Origin of the idea’, which is the macro-theme that features the highest number of appeals to integrity (n = 15, 14%) and appeals to intelligence (n = 16, 29%). As we explained above, the origin of idea statement is often constructed as a narrated argument in which the founder’s personal experience with a problematic situation constitutes the reason motivating the decision to resolve the problem or the inspiration for the development of the idea. The ethos analysis shows that integrity appeals are particularly frequent in the first part of this narrative argument, as the founder’s personal experience with the problem creates an image of authenticity (i.e., they know and have experienced what they are talking about). At the same time, appeals to benevolence and to intelligence are more likely to occur in the second part of the narrated argument, when the decision to act is made. Benevolence is signalled by the founder’s willingness to tackle the problem and do something good for society (example [xiv]), while intelligence is reflected in the founder’s know-how and creative elaboration of the solution (Suvie’s example [xi] above).

“In early 2015, I was back in my hometown of Detroit, volunteering with the Red Cross during the Flint water crisis and I observed that this community wasn’t just facing a horrific mannery water crisis, but now they were facing a localized environmental distrust, due to the fact that they were having bottled water for all of their daily needs. At the height of the water crisis, Flint was using more than 20 million water bottles every day. This ignited a conversation between Jack and I, “What kind of product of purpose could we design that could help address some of these issues we were seeing in Flint. Genusee was founded on the principles of doing good for people and the planet” (Genusee).

Other uses of integrity appeals: sincerity and involvement

The appeal to integrity occurs in ‘Project features’ (n = 14, 13.3%) as founders highlight their personal involvement with the process of product creation and their commitment to standards of quality and sustainability:

“Your old glasses can be refurbished, donated, or recycled back to our material stream. [Ali:] we are committed to giving back to the Flint community, so we are donating a portion of our profit to local charity organizations” (Genusee)

“With garments from Econyl Italy our product satisfies highest ecological standards” (Neumühle)

“I took the time to speak to women just like you to make my swimwear as good as it could be” (Tilia Rose Swim)

In ‘Requests to funders’, appeals to integrity frame founders as partners in need for help to realise something they are sincerely and seriously committed to:

“No business can run without a sign, so your donations will help my dream become a reality that you can also enjoy […] And I just can’t wait to have that little … that little dough guy painted on the door, ehm … I’ll probably cry, I don’t know. Yeah, your support would just mean the world to me” (Just what I kneaded)

“We are going to be as transparent as we possibly can and have worked incredibly hard to bring this product to life. But now we need your help to take the final step […] We hope you’ll enjoy using StikChops as much as we do” (Stickchops)

Ability and intelligence appeals: self-attribution of quality and uniqueness

Appeals to ability occur mainly in the macro-theme ‘Project’ (n = 50, 70.4%), more specifically in the sub-themes ‘Project features’ (n = 18, 36%), ‘Origin of the idea’ (n = 14, 28%) and ‘Current state of the project’ (n = 11, 22%).

When describing the product features, the appeals to ability are used by founders to attribute the features of the product directly to their peculiar competence and expertise, thus suggesting a sense of uniqueness of project:

“We’re gonna source, roast, blend and continuously be editing the Mix” (Yes Plz).

“Designed with powerful computer-aided design software and machine from aircraft grade aluminium, we have designed and manufactured precise modules that screw together perfectly” (LiteCans).

In ‘Current state of the project’, appeals to ability allow founders to stress what they have already achieved so far, thus signalling their proven competence in the design and creation of a valuable product. This move paves the way to the ‘Request to funders’: given what the founders have been able to achieve so far, preventing the project from its completion would be a shame, a waste of a great existing opportunity:

“After a year of extensive research and prototyping with world-class manufacturers, we created AIR the ultimate breathable blazer” (AIR).

“I collaborated with Data Brand and they did one run of 350 sweaters and they sold all of them. Ever since I’ve been doing’em and producing them myself” (Leave me alone sweater).

Benevolence appeals: embedding goodwill in product designs

Appeals to benevolence prevails in ‘Project’ (n = 29; 72.5%) especially in ‘Project advantages’. The expected benefits of the product on the users’ life is framed as a primary motivation for the founder’s engagement with the project:

“We really want to rejuvenate that downtown area and feel like Better Half Brewing can be a huge asset to downtown Bristol” (Better Half Brewing).

“We want it to be the place where people rediscover the beauty and the historical nature of downtown to kind of reinvigorate the downtown area in general, this Kickstarter is intended to bring us once again together” (RPG).

Pathos

Overall, in our corpus we found 207 segments with pathos appeal (34.4%) and 395 segments without pathos appeal (65.6%). The most used pathos appeal is audience-framing (n = 114, 19% of all segments, 55% of pathos appeals), followed by audience engagement (n = 68, 11.3%; 33%) and emotion-evoking (n = 25, 4.2%, 12%). Thus, in our dataset, pathos is expressed more as an audience-oriented framing of the project, rather than as an emotionally charged discourse.

Audience-oriented framing of the project

Audience framing is frequently used when elaborating on project advantages (n = 58, 51% of all audience framing appeals). In these occurrences, the project’s positive effects and the new affordances are described with an explicit acknowledgment of the user’s perspective, highlighted by the use of second person pronouns:

“FLECTR helps you master every dangerous situation in the dark reflecting the light back to its source, making you visible with a stunning glow all around” (Flectr 360 Omni).

“By using a plant container made of silicone, you get the benefits of both flexibility and extreme rigidity” (Indapot).

A very similar strategy is adopted in “Project features” when the product is strategically “described” with audience framing to, somehow, already hint to the user’s benefits which are more explicitly stated in ‘Project advantages’:

“Suvie automatically detects your food and keeps it refrigerated until its algorithms tell the appliance exactly when to start cooking” (Suvie).

“Into Arduino you can even program different light sequences or levels of illumination, through the programmings of it behind the reflector” (LiteCans).

Engaging backers rather than attracting funders

Numerous occurrences of pathos in the macro-theme ‘Request to funders’ refer to the manifestation strategy of audience engagement (n = 30, 44.1% in ‘Request to join’; n = , 27.9% in ‘Request to fund’), reflecting the founder’s effort to persuade backers not simply to pledge money but to support the campaign and feel themselves part of it:

“Being a start-up, we need your help to finance this production. Please back our campaign today and help us to create the future generation of sustainable swimwear” (Neumühle).

“It’s time to bring it to life so we really need your support to make it possible” (Zen).

“Support us and we’ll leave you alone” (Leave me alone sweater).

Emotion evoking: bad problem, good solution

The explicit expression of an emotion is a less frequent manifestation of pathos in the campaigns we have examined. Although the numbers are relatively low, it is interesting to observe where positive and negative emotions are verbalised: the latter are more frequent in ‘Problem’ (see example [xxxiii]), to reinforce a sentiment of dissatisfaction with the current situation, while the former are more frequent in ‘Project’ (see example [xxxiv]), thus creating a feeling of relief and joy coming from the disappearance of the negative situation.

“There has never been a better time to be a coffee lover, but a lot of this stuff you can find, doesn’t live up to the hype, and that’s really frustrating” (Yes Plz, emphasis added).

“We focused on simple and elegant design, that’s intuitive to use, making mealtime more enjoyable” (Stickchops, emphasis added).

Logos

Unlike for ethos and pathos, segments containing a logos appeal (n = 318, 52.8%) are more frequent than segments not featuring logos (n = 282, 47.2%). This suggests that CP are highly argumentative also at the micro-level of the text. Logos appeals are frequently used to make the macro-level argumentative relations explicit through linguistic markers (e.g., ‘so’, ‘that’s why’, ‘therefore’). In example [xxxv], the ‘project advantage’ segment appears as a claim justified (“so … ”) by the preceding ‘project feature’ segment. In example [xxxvi], the overriding macro-inference of the CP aimed at justifying the main macro-claim of the founders is expressed in ‘Request to fund’, which indeed constitutes the logical conclusion of the pitch.

“Suvie automatically detects your food and keeps it refrigerated until its algorithms tell the appliance exactly when to start cooking, so everything is ready for you at the same time” (Suvie).

“so, check out our rewards on the side with some really cool stuff going on and please donate to our kickstarter and thank you so much from the bottom of our heart, it means so much (Cereal Milk Ice Cream).

Refuting status quo

In ‘Problem’, logos mainly occurs under the form of counter-argumentation, as marked by contrastive linguistic markers such as ‘but’. The strategic function of this logos appeal is that of expressing rejection of the present problematic situation to create a sense of urgency and desire towards finding a solution. An argumentative pattern combining pathos and logos can be observed here: negative emotion markers (see above) feature the concessive clause, while positive emotions characterise the main clause, thus creating at the same time desire and excitement for a possible future state and sense of lack and dissatisfaction towards the present situation:

“I love potatoes, and I want them to be fresh and organic, just like my other crops. But growing potatoes in the traditional way requires a lot of work and loads of space. And with pest problems harvesting can easily turn into a very disappointing experience” (Paul Potato)

“Mealtime makes you feel great, but it’s not always easy using chopstick” (Stikchops).

Signalling intelligence

As explained above, the ‘Origin of idea’ macro-theme fulfils a trust-building strategy in which the decision to invent a solution to a problem signals the intelligence of the founder. This move, which connects the founder’s experience with the problem and the subsequent decision to create the solution, is often marked linguistically with logos appeals, reflecting the founder’s intention to effectively cause backers to infer ethos from the narrated event:

“So not satisfied with this, we decided to try something even more dangerous, making classic lemonade shandies” (Lemonade shandies)

“But to be honest, we were not really happy with the products on the market. So we decided to design and produce our own diffuser” (Zen).

Supporting the funding decision with a summarising argument

Micro-level argumentation is used in the concluding part of the CP when the ‘Request to funders’ is not simply claimed and let be inferred from the arguments made in the previous macro-them. The founder elaborates a sort of argumentative summary of the previously exposed reasons, based on a promise of benefit that would follow the success of the campaign:

“if we can get a ton of support, we’re pretty sure we can get the price down even lower” (Yes Plz).

“Join me now on this campaign and you will receive special gift items made by yours truly” (Launching Spring 2018)

This move recalls the final stage of the canonical model of rhetorical speech, the conclusio, in which speakers have to synthetically recall the main arguments for their claim and invite the judge to decide accordingly (Cicero, Citation1954).

Successful vs failed projects

The results reveal an important difference between successful and unsuccessful campaigns at the macro-thematic level in relation to the pitching strategy chosen by founders. Of the 15 approved projects, 11 features the societal problem-solution pattern, while the same pattern is found only in 2 unsuccessful projects. Founders of failed campaigns privilege either a personal problem-solution pattern (7) or a desire-project pattern (6). Interestingly, all the 7 highly successful campaigns (i.e. those that have raised more than 150% of the funding target) are based on the societal problem-solution strategy, suggesting than this pattern is more likely to lead to success rather than a founder-centric argumentative strategy.

The comparison of segment-level features between successfully funded campaigns and failed campaigns reveals some interesting patterns which are briefly discussed in this section. However, these findings need to be taken with caution due to the relatively small sample collected for this qualitative study. The few features which show statistically significant differences between winners and losers are: ‘Origin of the idea’ (13.5% vs. 8%); ‘Current state of the project’ (3% vs. 8.4%); ‘Appeal to intelligence’ (5.6% vs 12.4%); ‘Emotion evoking’ (6.3% vs. 2%).

The differences regarding ‘Origin of idea’ are of particular interest due the role this macro-theme plays in eliciting the problem tackled by the project. It corroborates the finding that successful founders are more likely to adopt a societal problem-solution pattern to encourage problem recognition and a sense of urgency in the mind of backers. Again, the significance of the differences in frequency substantially increases when the comparison is made between highly successful campaigns and the rest of the dataset, including moderately successful projects.

Overall, the findings suggest that the CPs of highly successful founders differ from the other campaigns in the following aspects:

They talk more about ‘Problem’ (11.6% vs. 9%) and ‘Project’ (76.2% vs. 66.37) and less about ‘Founders’ (4% vs. 14%) and ‘Request to funders’ (8% vs. 15%). This might also be explained by the fact that the founder has already a clear expertise or professional experience to claim and therefore less need for building a trustworthy image. Alternatively, it could suggest that successful founders understood that a focus on explaining how their project effectively resolves a common problem is a key driver of persuasion.

Within ‘Project’, they focus on ‘advantages’ (40.8% vs. 17.6%) more than on ‘features’ (23% vs 23.5%) and ‘Next steps of the project’ (0% vs. 5.5%). By doing so, successful founders effectively draw backers’ attention to the elements of the product that create expediency for the typical user-consumer audience on Kickstarter.

They use less ethos appeals (11.7% vs. 52.4%), but more pathos appeals (65% vs. 45%), reflecting an audience-oriented rather than founder-centric argumentative strategy (see above).

They use more argumentation (55.1% vs. 45.6%), i.e. they make a greater effort to present reasons connecting the different macro-thematic claims and reasons that justify micro-level claims. This is well exemplified by comparing a highly successful campaign like Suvie with an unsuccessful one like Sensolatino, which obtained less than 30% of its funding target. While Suvie’s pitch (see ) makes systematic use of argumentation to justify the problem and to highlight how the product solve them, the presentation of Sensolatino state the expected advantage without elaborating either on why this is really needed or desirable or on how this would be concretely achieved by the product. Even more interesting is the comparison between the just mentioned campaign of Sensolatino and a successful one made by the same firm back in 2016. The verbal track of the two campaigns is identical in the first part, but the video presentation of the successful one is longer and continues the pitch by elaborating arguments that highlight the product’s unique features, advantages and even the selection of the material. In their own words: “the reason we chose this material is not only because of their low weight but is its high durability and flexibility” (Kickstarter, Citation2016).

Conclusions

This article investigated the discursive content of crowdfunding pitches from the perspective of rhetorical argumentation, thus responding to recent calls for more qualitative investigations of crowdfunding presentations (Baid & Allison, Citation2019; Frydrych et al., Citation2016). The findings add to existing rhetorical research in crowdfunding and, more in general, entrepreneurial pitching (e.g., Tirdatov, Citation2014; Van Werven et al., Citation2019) while offering a complementary perspective to narrative studies of crowdfunding (e.g., Frydrych et al., Citation2016; Manning & Bejarano, 2014).

In relation to the rhetorical analysis of entrepreneurial pitching, this study brought to light the inherently argumentative dimension of crowdfunding campaigns not only in its micro-level rhetorical strategies (ethos, logos and pathos appeals), but also in its macro-level thematic structure. It was shown how project founders construct their pitch in such a way that it effectively responds to key issues potentially raised by a critical crowd to persuade them of the legitimacy and desirability of their project and, therefore, the expediency of funding it. Three main macro-level pitching strategies have been identified (societal problem-solution; personal problem-solution; desire-project) by which founders develop an argumentative structure governing the whole pitch. The logical connection between the macro-themes chosen by the pitching entity are often explicitly marked linguistic indicators of inference that further confirm the argumentative constituency of this genre of entrepreneurial communication. At the micro-level, a variety of patterns have emerged by which founders use appeals to ethos, logos and pathos in order obtain rhetorical effectiveness along with dialectical soundness. These patterns include offering further evidence of micro-claims related ta various aspects of the project, signalling trust-related qualities such as integrity or benevolence, and framing the project with an audience-oriented style.

Furthermore, the study proposed here examined argumentative strategies not only in funded campaigns (cf. Tirdatov, Citation2014), but also in failed ones, thus providing further evidence of the factors that explain success and contributing towards the identification of the elements that build up a compelling narrative (Frydrych et al., Citation2016; Luo & Luo, Citation2017). The findings suggest that this is the case when the pitch manages to construct a societal problem-solution macro-level pattern and, at the micro-level, to signal trustworthiness and to connect to the specific perspective and mood of the audience rather than developing a founder-centred presentation. More specifically, a compelling narrative (on Kickstarter) seems to have the following requirements: (a) make a case for a joint problem that is a societal need which is, at the same time, experienced by the founder and relevant for the backers; (b) connect problem and solution by focusing on the advantages of the project’s properties rather the description of its features; (c) signal integrity-based trust while arguing for the problem, benevolence-based trust when explaining the decision to elaborate a solution, and competence-based trust while describing the product; (d) keep an audience framing rather than developing a self-centred story. The later point requires, more specifically, to (i) describe the project with a pro-customer perspective, and (ii) use pathos appeals to emphasise the customer advantages stated in pragmatic arguments (i.e. reasons based on the positive consequences of an action).

Without neglecting the relevance of stories in entrepreneurial communication, the results of this study highlight the importance and convenience of framing the discursive content of a crowdfunding pitch in argumentative terms. A crowdfunding pitch is primarily constituted by arguments, some of which strategically conveyed in a narrative style (e.g., ‘Origin of the idea’), rather than stories possibly reporting reasons and argumentative experiences. In other words, the findings of this article suggest that founders on Kickstarter, and possibly similar crowdfunding platforms, are primary arguers rather than storytellers (cf. homo narrans in Fisher, Citation1984). They can profitably adopt narrative arguments (Tindale, Citation2017), i.e., using a storytelling mode to make communicated reasons more persuasive, but their primary communicative task is that of recognising and anticipating the issues raised by the crowd and respond to them with justified claims regarding the societal necessity, technical efficacy and practical desirability of the proposed project.

Apart from the above-mentioned theoretical implications, the findings of this study offer insights at practical and professional levels too. In designing their campaign, founders are recommended to adopt a rhetorical argumentative approach that starts from the identification of critical questions (issues) and address them with persuasive reasons that activate a societal problem-solution strategy. At the micro-level of the pitch, this strategy should use logos to ensure micro-claims are justified; exploit pathos to frame problems and solutions from the perspective of the consumer-funder rather than the founders’ one; and signal ethos, rather than explicitly claiming it. An excessively self-centred pitch, which focuses more on the founder’s personal story and desires, seems to be much less compelling than a presentation that provides evidence for a shared and societally relevant need and for a solution that is original, unique, feasible and, above all, useful for the ultimate user-funder.

These recommendations differ, to a certain extent, from those suggested in other pitching contexts. For example, Daly and Davy underline the “importance of the capacity to enact narratives and tell personal stories” (Citation2016, p. 128) based on their analysis of investor pitches addressing a jury of financial investors in a reality TV series. It goes without saying, though, that the effectiveness of a particular communicative strategy depends on its context and situation. The present study considered a specific genre of pitching (crowdfunding) in a specific type of platform (reward-based Kickstarter). Based on the findings of this research, founders of a Kickstarter campaign can draw a template that guides their communicative choices at the dialectical and rhetorical levels, considering both the structuring of the macro-level pitching strategy and the deployment of micro-level persuasive appeals.

The results can be of interest also for crowdfunding platforms, particularly Kickstarter and other reward-based crowdfunding websites, who need to formulate practical guidelines for founders. In this regard, it is worth remarking that Kickstarter gives a central role to storytelling in its handbook for project creators (Kickstarter, Citation2021b). While a more explicit emphasis on the argumentative management of the campaign is suggested here, this was not the aim of the present article. Further research is needed to understand how platform designs and guidelines can support founders in developing the most effective pitch. Future studies addressing this question could benefit from important works done within the field of argument design (e.g., Aakhus, Citation2003; Jackson, Citation2015).

In this article, crowdfunding campaigns were seen as a genre of strategic communication, not in the sense of an existing organisation advancing its mission (Hallahan et al., Citation2007), but as the attempt made by a communicative entity (the project founder) to build legitimacy for a not yet existing endeavour. The findings discussed above contribute to the study of strategic communication from a narrative-discursive perspective (e.g., Weber & Grauer, Citation2019) with a focus on argumentation. The study showed how argumentation constitutes a strategic resource that entrepreneurs mobilise in a non-routine communicative situation to obtain rhetorical legitimacy and to connect their strategic goals with the values and expectations of stakeholders. Because founders can rely on their existing reputation only to a limited, extent, their pitching strategy should focus more on highlighting the connection between the project’s features and the interests of the audience-funder while signalling their trust-related traits, such as competence, integrity and benevolence.

The patterns identified in this study inform the elaboration of message strategies, which represent one of the constitutive components of any campaign planning (Gregory, Citation2020; Mahoney, Citation2013). Another crucial element of such planning, which was not addressed in this study, is representede by media strategies, particularly how founders convey their pitch across multiple channels beyond the crowdfunding platform. Future research can investigate how the main arguments featuring a crowdfunding campaign are re-elaborated and adapted across different media, in particular social media.

This work did not come without limitations and gaps which future research can address in various ways. First of all, while the qualitative analysis developed in this study led to identifying a variety of strategic macro-level and micro-level argumentative patterns, the relatively small corpus examined does not lend itself to statistically significant generalisationse, especially for what concerns the comparison between “winners” and “losers”. Yet, this work built a theory-grounded and empirically-verified coding scheme that can be applied to similar studies on larger datasets. Moreover, the initial results obtained here suggest that the design of future studies comparing successful and failed campaigns would benefiting from overcoming the funded/not funded dichotomy to define more nuanced criteria of success. These should consider both the degree of success/failure (what percentage of the funding target has been (not) achieved) and the amount of funding requested.

Another limitation of this study is that it exclusively examined campaigns launched on Kickstarter and only in some of its sub-categories, which means that some of the key findings might be platform or sector-dependent rather than having relevance for any type of crowdfunding pitch. Therefore, future research could use the same corpus annotation method and apply it to the analysis of campaigns appearing on other crowdfunding platforms.

Similar to what done in most of the prior works, this study focused its analysis on the verbal track of the crowdfunding campaign, thus ignoring the audio-visual aspects, despite these being expected to fulfil very important rhetorical functions. Above all, audio-visual elements could convey emotional appeals that the analysis of the pitch’s transcript alone fails to capture. While the audio-visual analysis could result in a higher proportion of ethos and logos appeals, the possibility that multi-modal resources are used to convey or reinforce logical reasons should not be underestimated. For instance, the features of the product and its technical aspects are often visually displayed rather than being simply verbalised. Thus, the multimodal analysis of crowdfunding campaigns – which started attracting scholarly attention in recent years (e.g., Doyle et al., Citation2017; Grebelsky-Lichtman & Avnimelech, Citation2018) – constitutes an important area of future research that could extend the analytic framework constructed here to accommodate a variety of non-verbal argumentative strategies.

Finally, scholarly attempts to identify the key factors of success of crowdfunding campaigns would benefit from mixed-method approaches integrating the argumentative analysis of the pitch with process-oriented research aimed at shedding light on both the creation and the reception of a pitch. For example, retrospective interviews with creators of successful and unsuccessful campaigns may help understanding the process by which founders have formulated their pitching strategies. Similarly, interviews or focus groups with a panel of potential funders could offer stronger evidence for the effectiveness of a particular pitching strategy. For both lines of research, the findings of an argumentative analysis of the crowdfunding pitch, such as the one developed in this study, represents a vital starting point for the design of an appropriate theoretical and methodological framework.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank the two students from the university of Liverpool who helped with the collection and annotation of the dataset.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Strategic communication has been defined as “communication by an organization to fulfil its mission” (Hallahan et al., Citation2007, p. 3) and, more recently, as communication “substantial for the survival and sustained success of an entity” (Zerfass et al., Citation2018, p. 487). In this respect, crowdfunding campaigns can be framed as a form of strategic communication aimed at putting new institutional entities into existence.

2 As acknowledged by Frydrych, Bock and Kinder themselves, their methods “could not explicitly address certain key aspects of narrativity, such as role allocation, temporality and argumentative structure”. (Frydrych et al., Citation2016, p. 109).

3 A common misconception of argumentation is one which reduces it to formal logic and rationalistic discourse. Instead, argumentation should be more appropriately understood as a contextualised rhetorical activity aimed at reasonableness rather than rationality (Rigotti & Morasso, Citation2009; Van Eemeren, Citation2010). Adopting the normative ideal of reasonableness allows us to overcome the dichotomy between rationalist decision-making and heuristic-based choices to accommodate a compatibilist view of dialectic and rhetoric (Green, Citation2004; Jacobs, Citation2006) in which logical, interpersonal and emotional aspects can and do work together to obtain critical persuasion in context.

4 For reasons of space, we cannot discuss here the vast amount of literature on narratives and storytelling in organisational communication. Note that the two terms are used here interchangeably although important authors in the field (e.g., Boje, Citation2008) have clearly distinguished them.

5 As Olmos (Citation2013) explains, narratives can play an argumentative role in two senses: “(1) primary (core) narratives, regarding issues and facts under discussion, which may work as implicit arguments about the coincidence between discourse and reality via their own internal plausibility and 2) secondary narratives, imaginatively inserted in discourse, and serving as evidence for diverse lines of (either stated or unstated) analogical or exemplary argumentation” (p. 1).

6 We refer here to the doctrine of stock issues (Ehninger & Brockriede, Citation2008), introduced in the field of debate analysis as a method for identifying and evaluating arguments regarding the proposal of a new policy. Following this theory, four sets of questions need to be addressed in policy debates: (1) ILL (does the proposed policy deal with a relevant and urgent problem?); (2) BLAME (is the problem caused by the existing policy?); (3) CURE (does the proposed policy solve the problem?); (4) COST (do the expected benefits of the proposed policy outweigh the losses due the envisaged policy change?). The approval of the policy proposal requires all these issues to be resolved with an affirmative answer. A negative answer to one or more of these issues would normatively entail rejection of the policy.

7 Given the scope of this article, the very important audio-visual elements which fulfil both dialectical and rhetorical functions have not been considered here. the reconstruction of the multi-modal argumentative strategies in CPs is postponed to future studies.

References

- Aakhus, M. (2003). Neither naïve nor critical reconstruction: Dispute mediators, impasse, and the design of argumentation. Argumentation, 17(3), 265–290. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1025112227381

- Baid, C., & Allison, T. H. (2019). How crowdfunding deals get done: Signalling, communication and social capital perspectives. In H. Landström, A. Parhankangas, and C. Mason (Eds.), Handbook of Research on Crowdfunding (pp. 191–226). Cheltenham/Northampton (MA): Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Bitzer, L. (1968). The rhetorical situation. Philosophy and Rhetoric, 1(1) , 1–14.

- Boje, D. M. (2008). Storytelling organizations. Sage.

- Chen, S., Thomas, S., & Kohli, C. (2016). What really makes a promotional campaign succeed on a crowdfunding platform? Journal of Advertising Research, 56(1), 81–94. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2501/JAR-2016-002

- Cicero, M. T. (1954). Rhetorica ad Herennium ( Translated by Harry Caplan. Loeb Classical Library 403). Harvard University Press.

- Daly, P., & Davy, D. (2016). Structural, linguistic and rhetorical features of the entrepreneurial pitch. Journal of Management Development, 35(1), 120–132. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/JMD-05-2014-0049

- Doyle, V., Freeman, O., & O’Rourke, B. (2017). A multimodal discourse analysis exploration of a crowdfunding entrepreneurial pitch. European Conference on Research Methodology for Business and Management Studies (pp. 415–423). Dublin: Academic Conferences International Limited.

- Ehninger, D., & Brockriede, W. (2008). Decision by debate. IDEA.

- Fisher, W. R. (1984). Narration as a human communication paradigm: The case of public moral argument. Communications Monographs, 51(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/03637758409390180

- Frydrych, D., Bock, A. J., & Kinder, T. (2016). Creating project legitimacy–the role of entrepreneurial narrative in reward-based crowdfunding. In J. Méric, I. Maque, & J. Brabet (Eds.), International perspectives on crowdfunding (pp. 99–128). Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

- Frydrych, D., Bock, A. J., & Kinder, T. (2016). Exploring entrepreneurial legitimacy in reward-based crowdfunding. Venture Capital, 16(3), 247–269. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13691066.2014.916512

- Grebelsky-Lichtman, T., & Avnimelech, G. (2018). Immediacy communication and success in crowdfunding campaigns: A multimodal communication approach. International Journal of Communication, 12(2), 4178–4204.

- Green, S. E. (2004). A rhetorical theory of diffusion. Academy of Management Review, 29(4), 653–669. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/20159076

- Gregory, A. (2020). Planning and managing public relations campaigns (5th ed.). Kogan.

- Hallahan, K., Holtzhausen, D., van Ruler, B., Verčič, D., & Sriramesh, K. (2007). Defining strategic communication. International Journal of Strategic Communication, 1(1), 3–35. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15531180701285244

- Harmon, D. J., Green, S. E., Jr, & Goodnight, G. T. (2015). A model of rhetorical legitimation: The structure of communication and cognition underlying institutional maintenance and change. Academy of Management Review, 40(1), 76–95. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2013.0310

- Jackson, S. (2015). Design thinking in argumentation theory and practice. Argumentation, 29(3), 243–263. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10503-015-9353-7

- Jacobs, S. (2006). Nonfallacious rhetorical strategies: Lyndon Johnson’s Daisy ad. Argumentation, 20(4), 421–442. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10503-007-9028-0

- Kickstarter. (2016). Sensolatino eyewear Italian luxury polarized sunglasses. Made with love. Retrieved October 7, 2021, from https://www.kickstarter.com/projects/sensolatino/italian-luxury-polarized-sunglasses-made-with-love?ref=discovery&term=sensolatino

- Kickstarter. (2021a). Stats. Retrieved April 29, 2021, from https://www.kickstarter.com/help/stats?ref=global-footer

- Kickstarter. (2021b). Telling your story. Retrieved October 7, 2021, from https://www.kickstarter.com/help/handbook/your_story

- Luo, X., & Luo, B. (2017). Research on environmental crowdfunding projects based on narrative Persuasion theory. European Journal of Business and Management, 9(33), 99–105.

- Mahoney, J. (2013). Strategic Communication. Principles and Practice. Oxford University Press.

- Majumdar, A., & Bose, I. (2018). My words for your pizza: An analysis of persuasive narratives in online crowdfunding. Information & Management, 55(6), 781–794. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2018.03.007

- Manning, S., & Bejarano, T. A. (2017). Convincing the crowd: Entrepreneurial storytelling in crowdfunding campaigns. Strategic Organization, 15(2), 194–219. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1476127016648500

- Martens, M. L., Jennings, J. E., & Jennings, P. D. (2007). Do the stories they tell get them the money they need? The role of entrepreneurial narratives in resource acquisition. Academy of Management Journal, 50(5), 1107–1132. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2007.27169488

- Mitra, T., & Gilbert, E. (2014). The language that gets people to give: Phrases that predict success on Kickstarter. Proceedings of the 17th ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work & Social Computing, ,Baltimore, MD (pp. 49–61).

- Mollick, E. (2014). The dynamics of crowdfunding: An exploratory study. JBV, 29(1), 1–16. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2013.06.005.

- O’Donnell, M. (2008). Demonstration of the UAM CorpusTool for text and image annotation. Proceedings of the 46th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics on Human Language Technologies: Demo Session, Columbu, Ohio (pp. 13–16).

- Olmos, P. (2013). Narration as argument. OSSA Conference Archive, Windsor, Ontario (p. 123). http://scholar.uwindsor.ca/ossaarchive/OSSA10/papersandcommentaries/123

- Olson, P. (2017). Narration as argument. Springer.

- Palmieri, R. (2014). Corporate argumentation in takeover bids. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

- Palmieri, R., & Mazzali-Lurati, S. (2021). Strategic communication with multiple audiences: Polyphony, text stakeholders and argumentation. International Journal of Strategic Communication, 15(3), 159–176. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1553118X.2021.1887873

- Parhankangas, A., & Renko, M. (2017). Linguistic style and crowdfunding success among social and commercial entrepreneurs. Journal of Business Venturing, 32(2), 215–236. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2016.11.001

- Rigotti, E., & Greco, S. (2019). Inference in argumentation. Springer.

- Rigotti, E., & Morasso, S. G. (2009). Argumentation as an object of interest and as a social and cultural resource. In N. Muller-Mirza & A. N. Perret-Clermont (Eds.), Argumentation and education (pp. 9–66). Springer.

- Rigotti, E., & Rocci, A. (2006). Towards a definition of communication context. Foundations of an interdisciplinary approach to communication. Studies in Communication Sciences, 6(2), 155–180.

- Schoorman, F. D., Mayer, R. C., & Davis, J. H. (2007). An integrative model of organizational trust: Past, present, and future. Academy of Management Review, 32(2), 344–354.

- Tindale, C. (2017). Narratives and the concept of argument. In P. Olmos (Ed.), Narration as argument (pp. 11–30). Cham: Springer.

- Tirdatov, I. (2014). Web-based crowd funding: Rhetoric of success. Technical Communication, 61(1), 3–24.

- Van Dijk, T. A. (1988). News as discourse. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Van Eemeren, F. H. (2010). Strategic maneuvering in argumentative discourse. John Benjamins.

- Van Eemeren, F. H., & Grootendorst, R. (2004). A systematic theory of argumentation: The pragma-dialectical approach. Cambridge University Press.

- Van Werven, R., Bouwmeester, O., & Cornelissen, J. P. (2015). The power of arguments: How entrepreneurs convince stakeholders of the legitimate distinctiveness of their ventures. Journal of Business Venturing, 30(4), 616–631. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2014.08.001

- Van Werven, R., Van, Bouwmeester, O., & Cornelissen, J. P. (2019). Pitching a business idea to investors: How new venture founders use micro-level rhetoric to achieve narrative plausibility and resonance. International Small Business Journal, 37(3), 193–214. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242618818249

- Weber, P., & Grauer, Y. (2019). The effectiveness of social media storytelling in strategic innovation communication: Narrative form matters. International Journal of Strategic Communication, 13(2), 152–166. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1553118X.2019.1589475