ABSTRACT

Social media, particularly its more social aspects, can be challenging for organizations. In this article local governments’ communication on Facebook is used as a case study and analyzed through a mixed methods approach, utilizing distant and close readings of 50,000 Facebook posts from 23 Swedish local governments. The aim is to investigate patterns in both content and style with a particular focus on social interaction, drawing on a neo-institutional approach and the idea that communication can play an explicit social function. The findings suggest that local governments used Facebook mainly to inform citizens, whereas dialogue and discussion were directed elsewhere. When local governments translate social media into practice, it seems to be done in line with established channels and ways of communicating. These findings underline the need to understand local governments’ use of social media in relation to concepts such as openness and control, where attempts are made to control an uncontrollable online environment. Another key finding is that local governments seemed to post when there was very little or nothing to say; they posted about the mundane, trivial, and ordinary. These findings indicate an adaptation of the language and discourse of social media which contrasts with bureaucratic language.

Introduction

The life of contemporary organizations is characterized by insecurities. In response to these insecurities, organizations are turning to communication to create long-term stability and security; to ‘get this right’ (Zerfass et al., Citation2018, p. 495), and to build a blueprint for navigating a society that is permeated by symbols and symbolisms. At the heart of such struggles is the recognition that communication is an interactive, participatory, and constitutive process (Van Ruler, Citation2018). Here, social media and its social logic are challenging for the organizations who use them, and yet are an intrinsic resource in their strategic efforts to reach organizational goals, attain license to operate, compete, and better relationships with the outside world (Heide et al., Citation2018, p. 452). Volk and Zerfass (Citation2018, p. 435) notes that in this process, ideally, communication policy and activities should be aligned with each other and overall goals. A strategic approach supports and informs organizations and practitioners’ navigation of the delicate digital and social landscape.

In this paper organizations’ use of social media are analyzed, using Swedish local governments and their social media presence as a case study. This article utilizes digital text analysis and topic modelling to map and explore patterns in content and style, with a particular focus on how local governments promote social interaction. Local governments are an interesting and illuminating object of study as they are large, diversified, complex, and rule-based organizations. Drawing from a neo-institutional perspective, Fredriksson et al. (Citation2018) show that despite governments’ internal differences, tasks, and makeup, they aim to communicate a cohesive and unambiguous image to many different audiences and stakeholders while at the same time appearing transparent and open. Like many other organizations, local governments are also indirectly driven by competition for labor, service, investments, and tourism, and innovative services to become more efficient and more attractive; but also – and in contrast to many other organizations – by softer values such as democracy.

Local governments, like most organizations, have increasingly turned to social media platforms like Facebook to pursue activities such as listening, interaction, creating brand awareness, marketing, service, customer service, and more. From a perspective of local governments and organizations, social media’s technical aspects have become crucial as they allow dissemination of a broad spectrum of messages in a fast, directed, and cost-efficient way. Also important, but less utilized and far more challenging, are the social aspects of social media as they potentially allow governments to interact with their citizens (Van Dijck, Citation2013), and even turn them into a ‘voluntary’ strategic resource (e.g., Zerfass et al., Citation2018). At the strategic level, the technical and social dimensions connect to discussions of control versus openness and uniformity versus transparency within the field of strategic communication (Fredriksson & Edwards, Citation2019; Macnamara & Zerfass, Citation2012; Smith, Citation2015). Local governments thus need to make strategic decisions about their presence on social media, as it introduces both new possibilities and uncertainties surrounding ‘controlling’ their reputation, messages, image, brand, and more. However, local governments’ presence on social media also needs to be understood against the background of their institutional frameworks and regulations. What local governments can or cannot communicate differs compared with many other organizations (e.g., March & Olsen, Citation2008). For instance, local governments can’t be intentionally provocative or stand out as much other actors, features that have been shown to drive interaction on social media. Adopting a safe or cautious approach to controlling information and social media feeds can result in social media becoming ‘just’ another channel where information is routinely transmitted. The next section further situates local governments’ preconditions to working with strategic communication and social media. This is followed by a guiding theoretical framework and a literature review defining concepts and gaps. This is followed by an attempt to expand the concept of ‘social’ and a discussion of the articles’ aims and research questions.

Swedish local governments as organizations

Gulbrandsen and Just (Citation2016, p. 224) argues that to understand how the ‘strategic’ in strategic communication works, and who it is that is working strategically, one should not only ask how organizations communicate strategically, but also what kinds organizations are communicating. Politics and organizations at the municipal level in Sweden are characterized by strong centralized parties and an apolitical administrative culture. Local governments have considerable autonomy and taxation rights and are tasked with providing elder care, pre-school and K-12 schools, public transport, housing, garbage disposal, building permits, home-healthcare, and more. In Sweden there are 290 local governments of various sizes, all performing similar tasks at different scales and with varying structural preconditions (Montin & Granberg, Citation2013). Local governments are also often the largest employer in their own municipalities.

Communication departments in local governments do not generally have their own internal agendas. Communication activities are planned and based upon political priorities; usually based on a four-year political mandate by ruling parties, but also on long-term goals (such as population growth), often set down by a broader local political coalition. In practice, the communications department often supports other departments within local government organizations as they work to implement such goals by aligning (Volk & Zerfass, Citation2018) themselves with communication strategies through planning, production, and support. However, as a managing function, communication is also central to efforts of procuring investments, educating workers, and increasing tourism by maintaining and curating the image or brand of the municipality (Wæraas et al., Citation2015; Wæraas & Byrkjeflot, Citation2012). In terms of public information and crisis communication, managing communication pertains more to issues of guidelines, language, images, and organization; that is to standardize communication according to laws and requirements (Fredriksson et al., Citation2018). In this sense management includes the institutionalization of messages, graphics, profiles, images, and platforms. For instance, communication departments often have a major influence on how local governments utilize social media, by being responsible for guidelines for its use, or by preparing and suggesting revisions to communication policies.

A neo-institutional approach to strategic communication

A central and theoretical point of departure for this study is that local governments, as is the case in most organizations, abide by specific rules, norms and conceptions for how to appear, behave, and communicate (e.g., DiMaggio & Powell, Citation1983). As such, the ‘what’ and ‘how’ of communication are bound to conventions as to what is ‘appropriate’ for a particular organizational field (March & Olsen, Citation2008). Ideally, organizations and their members translate practices, like social media practices, to their fit their particular setting (e.g., Czarniawska & Joerges, Citation1996; Lövgren, Citation2017). What is appropriate in terms of communication can be made visible through policies, as shown in a recent policy study on communication work in Swedish local governments by Fredriksson et al. (Citation2018). They have shown that work is organized according to seven principles: interaction with stakeholders to gather opinions; positioning the municipality as a place to visit, work, and live in relation to other municipalities; organizing and erecting a structure for communications work to achieve organizational goals; appearing uniform by remaining consistent in communication and graphics; establishing routines for alerting inhabitants in the event of a crisis; serving citizens by utilizing digital services and the web; and informing by interacting with journalists and the ‘outside world.’

For this particular study, all principles except ‘organizing’ form a framework for understanding local governments’ communication tactics and use of social media. Organization is important in that structures and priorities have a decisive influence on communication but are also difficult to study through content alone. However, content and connections like links can potentially say something about structure: about how different channels are connected and where the public’s attention is to be directed. The other six principles are more productive when it comes to learning about social media as they, in one way or another, describe particular content such as marketing, or a particular style of communication such as interaction or one-way modes of informing or alarming. In line with an established approach to strategic communication (Zerfass et al., Citation2018) these principles can be viewed as a framework to facilitating overall achievement of organizational goals. The extent to which different principles are repeatedly invoked says something about how different objectives are prioritized. For instance, how local governments address citizens or followers on social media – according to which principles – can be informative as to goals and intent. Whether citizens are intended to participate in building a strong brand, to inform themselves about events or decisions, or participate in decision-making processes can point to different and sometimes conflicting principles and goals (e.g., Fredriksson & Pallas, Citation2016)

However, it is important to note that the neo-institutional view underlines strategic communication as institutional work which infuses organizations with meanings and values to shape organizational goals and practices (Fredriksson & Pallas, Citation2015). Extending this further by drawing on Botan’s (Citation2017) publics-centered view on strategic communication as cocreational, the principle of interaction combined with the social dimension of social media places the public, citizens, and stakeholders in center of creating new meanings. Reconciling interaction with principles like uniformity and positioning can present difficulties. Maintaining control and appearing to be a consistent actor is difficult for large and complex organizations, especially when they are supposed to be open and responsive (Fredriksson & Edwards, Citation2019). Again, how organizations choose to utilize social media in such cases is in part a result of how they translate it into the organization (Lövgren, Citation2017; Sahlin-Andersson, Citation1996). With these theoretical conceptualizations in mind, the content (what) and style (how) of local governments’ communication on Facebook can be elaborated by a literature review.

Local governments and social media content

Previous research on local governments’ Facebook use has focused on what shape content takes qua media use (links, video, image, events, and status text), as well as on the topical content itself: societal information, marketing, social gestures, and so on. Studies have concluded that visual materials such as video and images in general provide higher interactivity scores and potentially optimize message impact (Baltz, Citation2020; Lappas et al., Citation2018; Lev-On & Steinfeld, Citation2015). In a longitudinal study of Swedish local governments’ Facebook use, Baltz (Citation2020) showed that local governments were adjusting their posts to a ‘visual online culture’ over time. Previous research is quite clear that topical content most often adopts an informative stance rather than performing questions or using other means to entice participation or social interaction (DePaula et al., Citation2018; Lappas et al., Citation2018, Citation2021). Content is dominated by topics on what local governments do, presenting public information on services, events, or maintenance (DePaula & Dincelli, Citation2016; Gao & Lee, Citation2017; Lappas et al., Citation2018, Citation2021), but also takes the form of self-presentation (Bellström et al., Citation2016; DePaula et al., Citation2018). However, less is known about these developments over time.

Research has continuously articulated the potential of social media as an important space not just for participation, but also for collecting information or accessing knowledge outside the organization (Avery & Graham, Citation2013; Norström, Citation2019; Plowman & Wilson, Citation2018; Rasmussen & Ihlen, Citation2017). Content that includes posing questions (rhetorical or not), visual materials, and faster response rates have shown the potential to both increase citizen outreach and participation (Lappas et al.; Lai et al., Citation2020; Mergel, Citation2017; Metallo et al., Citation2020). Previous research highlights both the challenges and the possibilities of expanding citizens’ roles from receptive public to co-creator or participant. On this point Criado and Villodre (Citation2021, p. 271) also argue that frameworks used to study social media rarely include service as a central aspect. By expanding this point, when and where information dissemination, listening, participation and co-production are invoked relates to organizational processes. Issues like service co-production can be ongoing throughout the year, while other issues are more likely to occur at certain times. A considerable gap in previous research, which is likely due to its reliance on smaller datasets collected over limited timeframes, is the question of when organizations like local governments communicate certain topics, and thus when they seek citizens’ attention on different matters. In this article such patterns in content is traced through topics generated by the topic modelling (as a pattern can consist of many topics) and close readings that leans on our theoretical framework.

Local governments and communication styles in social media use

A common way of classifying local governments’ communication styles on social media has been the push, pull and networking framework developed by Mergel (Citation2013) and expanded by DePaula et al. (Citation2018). “Push” captures one-way styles of communication such as increasing information flows and transparency by disseminating information and education; “pull” (or “calls”) is occupied with ways of drawing followers into discourse in deliberation, participation, and collaboration; and “networking” captures collaboration with citizens on issues or design of services (Mergel, Citation2013). DePaula et al. (Citation2018, p. 101) expanded this typology to also include symbolic or social acts to also capture and describe communication that lie outside of the commonly-mentioned features as transparency, participation, and collaboration. A more recent study by Lappas et al. (Citation2021, pp. 2–3) suggests, through a literature review, that local governments’ posts on social media have six aims spanning both styles and content: informing, transparency, branding and Public Relations, facilitating online and offline participatory activities, and increasing responsiveness. In essence, these frameworks direct their attention to information flows between local governments and their citizenry. Similar to the guiding framework proposed by Fredriksson et al. (Citation2018) they contain ideas of both democracy and government – informing, transparency responsiveness and participation – and ideas of local governments operating in a market on the other hand; namely branding and Public Relations. The former set inhabits a communication style that focuses on communicating information about the government and its operations while the latter aims to position the place to the outside world.

Most studies on local governments’ styles of communication in social media have, to little surprise, concluded that pushing information is the most common style of communication. There is empirical evidence that local governments use social media primarily to facilitate information delivery and increase transparency (DePaula & Dincelli, Citation2016; Gao & Lee, Citation2017; Lappas et al., Citation2021; Reddick et al., Citation2017) and marketing (Bellström et al., Citation2016; Bonsón et al., Citation2015; Magnusson et al., Citation2012). These findings reflect Van Dijck’s (Citation2013) conception of Facebook as technical infrastructure for pushing information, and social media as a fast and cost-efficient way to reach audiences. Leaning on the technical infrastructure may be an attempt to manage and retain control over information and organizational image and perception (Mergel, Citation2017; Wukich & Mergel, Citation2016). For instance, evidence that social media is institutionalized in ‘ordinary ways’ of doing communication is visible through governmental policies, which often require information to first be posted on the governmental web page and a strong connection (links) between local governments’ Facebook pages and webpages (Baltz, Citation2020). Leaning on institutional resources like references or links to governmental web pages can also be viewed as being risk-averse in an environment that can be difficult to control. Yet, as noted by Macnamara and Zerfass (Citation2012, pp. 303–4) such an approach is at risk of being in “direct conflict with the philosophies of openness, participation, and democratization of Web 2.0.” Connected to this philosophy is a particular style of ‘mass self-communication’ inherent to social media (Castells, Citation2009, pp. 65–7). Communication still reaches a mass audience but is more self-regulated in terms of what, when, and how content is to be consumed or shared. To more fully understand how users’ (cultural) practices and social media habits impact communication styles and content, it is necessary to expand the notion of what ‘social’ means in relation to social media.

Extending the notion of the ‘social’ in social media

While the frameworks and research presented in the previous sections capture many aspects of communication, they are mainly situated, in style and topical content, inside a construct of communication that hinges on description or intellectual reflection. As alluded to above, DePaula et al. (Citation2018) extends their framework to include symbolic representations and social signals such as favorable representation, expressing gratitude or reference to cultural symbols, and thus begins to explore the social and meaning-making aspects of communication. However, they do not fully explore a less goal-oriented and trivial ‘phatic’ function that fosters social connections (Miller, Citation2017). Thus, to ‘harness the power of social media’ (Lappas et al., Citation2021, p. 1) and broaden our understanding of local governments’ social media practices, and to potentially build strategies that can develop and sustain organizations and their goals and relationships, these social aspects require closer scrutiny.

One way to view symbolic acts and further distinguish them from other styles of communication is through the idea that communication could be phatic. Phatic communication can be traced back to Malinowsky (Citation1923), who, through the use of “phatic” points to language where the goal is the exchange of words in itself. Malinowsky (Citation1923, p. 315) suggests that “each utterance is an act serving the direct aim of binding hearer to speaker by a tie of some social sentiment or other.” The primary function of such language then is not to describe or to facilitate intellectual reflection; its principal aim is social engagement. Jakobson and Sebeok (Citation1960, p. 5) points out that certain language use primarily serves to:

… establish, to prolong, or to discontinue communication, to check whether the channel works (“Hello do you hear me?”)’ or to ‘attract attention of the interlocutor or to confirm his continued attention (“Are you listening?” and on the other end of the wire “Um-hum!”).

In context of an online setting, and in particular local governments’ Facebook pages both Malinowski’s and Jakobson’s notions of the phatic can be useful in distinguishing between different styles of communication, such as symbolic representation or where the principal style is socially based. Miller (Citation2017, Citation2008) has suggested that social media prioritizes “networking over content” and that mundane or trivial updates aim to maintain social ties (networking) rather than initiate purposeful conversation. In either case – social ties or simply keeping an open channel – this ‘phatic’ notion can be productive in expanding our understanding of how local governments use Facebook as a channel for communication; particularly highlighting the explicitly ‘social’ aspects of local governments’ use of social media. It can also be productive in facilitating a better understanding if, and if so, how, organizations struggle to translate goals surrounding their use of social media into practice and develop a sociable ‘persona’, acclimating their abstract self to the personal mode of social media.

To conclude, there is a rich body of smaller and insightful empirical studies with limited data regarding what and how local governments communicate via Facebook, but few studies have covered longer periods of time and larger amounts of data to articulate the question of social media use. The aim of this study is to gain further insight into local governments’ use of social media by examining communicative patterns in local governments’ Facebook posts. Furthermore, the study aims to investigate how local governments promote social interaction via Facebook. The aim is answered by utilizing distant reading as a method, which has its strength in discovering patterns in extensive materials (Maier et al., Citation2018), and by posing two questions, namely: what communicative patterns can be found in the posts and do they change over time (RQ1)?; and what patterns can be found in the style of communication and do they change over time (RQ2)? Examining patterns in communication can facilitate a deeper understanding of how local governments communicate via social media and of adaptation over time. It can also potentially inform a discussion on strategy. While it is challenging to examine strategies without asking practitioners how they reason, statements do not always reflect reality. Investigating patterns over time becomes a way of complementing existing discussions and knowledge about how social media can contribute to organizations’ strategic communication, specifically when they need to navigate ideals and norms such as transparency and uniformity. Such processes are relevant to both practitioners and researchers outside the Swedish context.

Material and method

Facebook is, and has been, by far been the most commonly-used social media platform in Sweden (Internetstiftelsen, Citation2020), and the sheer volume of use is in and of itself a strong motivation for any study. While Facebook shares many functions with other social media platforms, it is not limited in characters like Twitter and allows easier integration from external sites and services in comparison to mobile-first platforms like Instagram. Its ability to combine and integrate many different forms of media types may, in comparison to other social platforms, allow for a greater variation of both communications styles and contents, like including interactive maps from Google in times of a crisis.

The data was collected ex-post from 23 Swedish municipalities’ Facebook pages ranging from January 1, 2010, or when the first post was published, to September 15, 2017 (Appendix 1). The data includes 50,298 posts and were collected by interacting with Facebook’s API using a python script to collect posts and interaction statistics from the selected pages. The collection included status message, media type (video, photo, link, events, and status texts), links and date. Data collection excluded videos, images, and any comments written or included in said posts. However, the script provided a permalink to each and every post so that they were easily and manually accessible. The data used here is a subsample drawn from a larger database but controlled to ensure a variation in municipalities’ size and location built upon classifications drawn by the Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions (Citation2017). As the data covers a period of eight years, changes within the municipalities are to be expected, as are deleted posts. Facebook posts are, in general, considered public documents and are thus regulated by law as documents that must be saved, archived, and made available to the public. While this does not guarantee that no posts are deleted, it imposes legal restrictions on such practices. Over the studied period, policies and guidelines have been developed, the knowledge and skills of practitioners handling the accounts has increased, and political shifts have occurred. The growth of new platforms such as TikTok, Instagram, and Snapchat may very well have impacted posting patterns and content. However, a longitudinal approach also allows for the potential study of the professionalization of strategic communication on social media in terms of both style and content (Johann et al., Citation2021, p. 8). For the purposes of this article, the assorted status texts in each of the posts was used.

To interpret the results an abductive approach was used to move between material and theory, and the results are thus a product of engaging with theory, previous qualitative studies with smaller materials, and empirical findings in the corpus. It should be added here that methodological approaches that utilize distant reading are by nature also explorative, and the size of the corpuses and the automated thematic modelling can reveal patterns that otherwise go overlooked. However, and as outlined in the previous section, findings do require deeper contextual understanding before they can be situated. To process and analyze the status texts, topic modelling using the Mallet configuration was used (McCallum, Citation2002). The topic modelling used here is developed by Blei (Citation2012) and builds on Bayesian statistics and the ‘bag of words principle’, meaning that the algorithm measures the frequency of a word in each document, but the order in which a word appears is irrelevant. The model rests on the assumption that every document can contain several topics, and assigns documents that contain similar word distributions to similar topics (Maier et al., Citation2018). To answer the research questions, some preprocessing and cleaning of the text data (or corpus) was necessary. As the material ranges from 2010 to 2017, the material was divided into documents according to municipality and month to better see and understand the material based on when and under what preconditions it was produced. Large documents were split into several documents to keep the number of words in each document to around 500 for optimal results (e.g., Guo et al., Citation2016). The algorithm then uses a probability measure to distribute all words in the documents into topics (the number of topics is determined by the researcher). The connection between documents (in our case a months’ worth of posts from a municipality) and topic is thus based upon how many words a document contains in relation to the topic in question. It is important to note that the number of topics chosen by the researcher here affects the distribution of words to topics and thus a documents’ connection to a topic (Maier et al., Citation2018; Underwood, Citation2012). For this particular study a lower resolution (ten topics) was used to capture the ‘overarching’ themes present within the material. Models running with higher resolution (15, 20, 25, or 30 topics) resulted in similar but even more overlapping themes.

To answer RQ1, nouns and adjectives were selected, since nouns can give a good indication of the topics under discussion, while adjectives can indicate how local governments characterize such topics. To isolate these word classes and further ensure the quality of topics and facilitate their interpretation, text resources available at the Swedish Language Bank were used (spraakbanken.gu.se). Preparation of the material began through use of a part-of-speech tagger to identify and isolate nouns and adjectives. Commonly-used parts of speech like pronouns, conjunctions, and prepositions may, by means of their commonality, displace more interesting words in the topic modelling. Other issues that needed to be addressed were those of tense, numeracy, determiners, and occasionally, regional variations of words. For instance, variations of water (vatten, vattnet, vattnets) are perceived by Mallet as unique words, yet it may push away other interesting words and does not help us in any meaningful way to understand what other words water is connected to. To address this issue, the material was lemmatized using The Language Banks’ pipeline for language processing (“SPARV”) and their implementation of Stanza (Qi et al., Citation2020, Citation2020). A stop word list was then applied to remove regional or local words categorized as nouns such as place names. To tag or name the topics, a manual close reading of the 30 documents with highest weight to each topic was conducted. The results were exported to Excel and Gephi for modelling and presentation.

For RQ2, AntConcs’ functions were used to look at and extract collocates, key words, and clusters from the lemmatized material, with the aim to zoom in on topics and language use to – at a deeper level of the texts – highlight different tendencies in topics. To zoom in on particular styles and label them as calls and pull messages, common phrases were used to explore what kind of calls local governments facilitated via Facebook (). On this final point it should be added that this study is limited in the sense that it does not engage with the comments. This limitation may potentially risk losing some sight of citizen–government interaction. However, the purpose here is not to study the interaction as such, but rather to identify patterns through which local governments are trying to draw citizens into exchange.

Table 1. Calls in the corpus constituted by the pronoun ‘du’ and the verb ‘tycker’.

Table 2. The 40 most common clusters containing verbs that co-occurred with the pronoun ‘you’ (or ‘your’) in the corpus.

Results

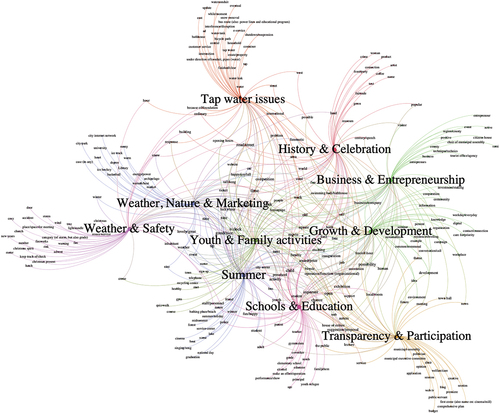

Topical content on local governments Facebook pages

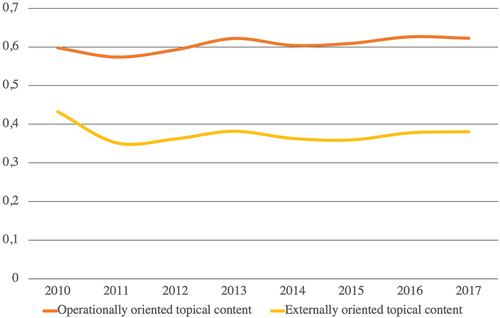

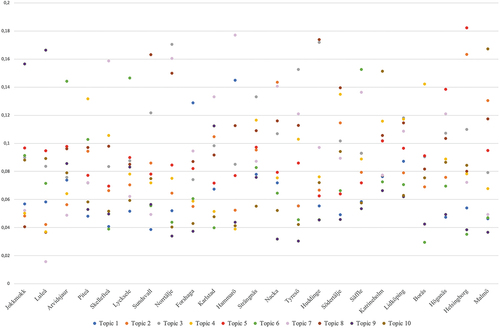

The ten topics generated by the model provided a thematic birds-eye view of the content posted by local governments as status texts (see, ). Drawing on Fredriksson et al.’s (Citation2018) classification of local governments as operationally or externally oriented in their communication, the former constituted a larger part of the content. Six of the topics were primarily concerned with government operations and activities, and four topics were primarily directed toward the outside world. The distribution of topics in the corpus between these two types of content also appeared to be relatively stable over time (). However, most topics include both parts.

Operationally oriented topical content

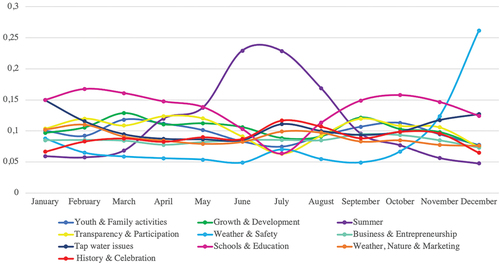

The topic growth and development (0,10,773) concerned issues related to how municipalities or regions could expand and prosper in the future. Seminars, education, lectures, workshops, and events raised issues such as entrepreneurship, employment, housing, and area development. Another key aspect of the theme was that growth and development were reached through participation, cooperation, and coordination between government, business, citizens, and associations. Topic four (0,10,164), transparency and participation, contained information about political processes and decisions such as planning work. This also included invitations and information on when and where to meet politicians and public servants, participate in dialogues on various topics, and follow municipal council and municipal executive committee meetings. These two topics were most closely linked to issues of participation, and also showed among the strongest increases after 2016. The topics weather and safety (0,07916) primarily concerned storms and accidents, such as winter storms, traffic accidents, and fires that occurred in connection to Christmas and New Year’s celebrations. The topic business and entrepreneurship (0,07603) mainly accentuated local governments’ company visits, meetings, or seminars with or about entrepreneurship, but also tourism and the tourism industry. The top documents contained various invitations to or retellings of visits, seminars and presentations or various rankings on the local business climate. The narrative was often characterized by positive adjectives. The topic tap water issues (0,10,830) deals with planned and unplanned interruptions or problems with drinking water supply, such as leaks, repairs, pressure losses, or infections in drinking water. The topic schools and education (0,14,052) had the strongest weight in the corpus. The topic drew from events and actors connected to pre-, primary, and secondary school. In the theme’s top documents, three actors were prominent: students/children, educators, and parents. The theme was not primarily focused on teaching, but rather on selecting schools, enrollment, different nominations, competitions, and prizes for students and educators ().

Figure 2. Figure illustrating ten topics through the top 50 nouns and adjectives in each topic.

Externally-oriented topical content

The topic youth and family activities (0,09988) contained information about activities and events primarily aimed at parents and families with children. For example, this included information about and links for opening hours, registration for various sports and cultural camps during the holidays and on weekends. References to various local sports events, whether the students in a school had achieved something special, and information given to parents prior to the start of the school semester were also frequently present in the documents with the highest emphasis within the theme. The topic summer (0,11,370) concerned events and activities happening during the summer. The topic’s top documents all came from the summer months. In particular, this mostly concerned school graduations, national holiday celebrations, summer holiday activities and activities that aimed to get people out in nature. The topic weather, nature, and marketing (0,08433) were largely based on status text’s function as a caption for various destinations, weather, and nature images. Captions and descriptions of nature, places, events, activities, and destinations to visit were often embedded in positive adjectives. Many posts in the highest-weighted documents also communicated famous buildings, landmarks, fairs, and the sort of activities the locals or tourists engaged in. The topic history and celebration (0,08867) was mainly based on posts where municipalities highlighted the history of the area, the city, or the community. Historicization took place mainly through longer narrative texts about local settlements, buildings, living conditions, or life stories. Another part of this historicization included various events linked to the anniversary of the city or some other important local feature.

Patterns in local governments content

When comparing the content against municipal tasks and mandates, it was striking how absent social services were from the content, as this is the other major task, besides education, (in terms of budget and personnel) that local governments provide. Overall, topics did follow what previous studies have found to a large degree. All topics, except the topics of weather, nature, and marketing, could be viewed mainly as communicating neutral information which reflects the formal image and task of local governments (e.g., Criado & Villodre, Citation2021; DePaula et al., Citation2018; Lappas et al., Citation2021). In this sense much of the content was apolitical. Another general pattern in local governments’ posts was that they exhibited a cyclical character ().

However, this is tied to Swedish tradition and need not necessarily be the case for other countries with different administrative structures (Lidén & Larsson, Citation2016). The school year and industrial (summer) vacation did, for instance, leave its mark on how posts emerged. Similar patterns could also be found in calls to participate with spikes before and after summer vacation. As in most other organizations, many things need to be finished before politicians, public servants, and communication professional can take their vacation. The summer, which is the time when tourism takes off, was also the time when externally-oriented topics increased the most. Increases in weather and safety topics stems from reminders to putt out candles, be careful with fireworks, and the topic of traffic increased as snow and winter storms started.

Close readings of the content revealed other patterns. For instance, events and activities emerged in the largest topic schools & education, as well as in many other topics. In the case of education, this included educational fairs and student art exhibits. Events and activities, together with a range of tasks such as repairs and maintenance, highlighted how Facebook was used as a calendar of municipal events or operations. For instance, the most common noun in the material was the Swedish word klockan (o’clock, time), mentioned 4,213 times (this does not include semantic variations like “today at 11.00 … ”). Examining how different nouns correlated with the word “klockan” and its distribution over the topical content generated by the model () it was possible to delimitate this calendar function into patterns following the operational/external dimension (Fredriksson et al., Citation2018). Operationally-oriented content following the principles of informing, alerting, interacting and serving included examples like opening hours, when repairs of water pipes will be finished, or when and where replacement water tanks are available, information meetings on decisions or after decisions, invitations to participate, assembly meetings and more; and externally-oriented content that followed principles of informing and positioning, as in promotion of events such as festivals, art exhibitions, inaugurations, marketing, and more.

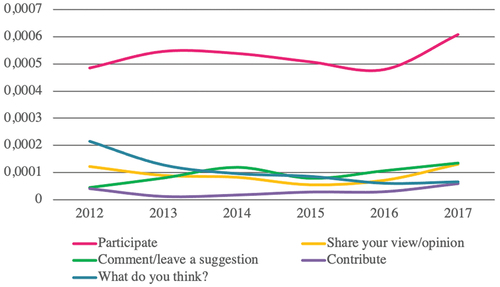

Close readings of the topical content revealed a large range of calls. By drawing on Lai et al. (Citation2020, p. 150), who found that a dialogic conversation-style aiming at ‘you’ or ‘we’ resulted in more interaction than non-dialogic–styled ‘he’ or ‘she’, calls were investigated in more depth by zooming in on the most commonly-occurring and interactive pronoun in the material; you (or your, in the Swedish language you is a pronoun that targets individuals and not collectives), and its co-occurrence with the verb think (the Swedish tycker) it was possible to note a range of ways in which local governments called upon their citizens (). In line with previous research (Lappas et al., Citation2021), offline participation was the most common pattern of participation in calls that were directed to the noun ‘you.’ The most common type of call was a call for participation in planning processes for local development, particularly detail and overview plans. It is in fact a type of participation that is defined and regulated in Swedish law (riksdagen.se).

Almost all calls followed a pattern that included information about where to join a meeting or where on the web page to read more about the plans; but in a few cases Facebook was used as a complimentary medium.

Another distinguishing pattern in local government’s calls where how they aimed to secure an inflow of information through surveys, feedback, and opinions. Political participation between elections in Sweden is centered around strong political parties as the main body (Montin & Granberg, Citation2013), which may in part explain why so many calls in the material contained language that indicated an aim to gather information from citizens, to strengthen input legitimacy. In the content, Facebook was conceived of as a more central space for interaction in calls interpreted as phatic or purely social; like what followers thought of a festival or event, how and if they liked different seasons, weather, or images depicting something local posted by the local government (see, ). Facebook also appeared more central in calls that had communication as a main theme, particularly when local governments were searching for input on their activities on Facebook.

Overall, and as was particularly clear in the calls presented in , it seems that when local governments translate social media into practice, they do so largely using their webpage as a model. While all principles could be identified, many over several topics, it is clear that interaction is a less salient principle than others. In the pattern of calls identified and the patterns that emerged as calendric, local governments showed that they wanted to inform, to be transparent, and so on; a result in line with previous studies (Bonsón et al., Citation2015; Lappas et al., Citation2018). It seems that when local governments have gotten hold of citizens’ attention, they insist on redirecting it elsewhere. This particular pattern is explored further in the following section.

Styles of communication on Facebook

Directing citizens’ attention elsewhere was a distinctive style of communication. This pattern was born out of a close relationship between the governments’ websites and Facebook pages, and was visible in the content through links (Baltz, Citation2020), but could also be seen linguistically. For instance, the most common word that co-occurred with information (1135 times) was by far the word more, most often in the form of ‘more information available on www’ or similarly ‘more information via the link below’ (). With the webpage as a base and Facebook as an extension of this base, a logical consequence of the relation between these two channels was for local governments to adopt strategies to pull citizens to the web page. Again, this particular use became visible through the pronoun you (or your) and its co occurrence with different verbs ().

In these calls local governments used a range of modalities to address their followers. For instance, it was possible to distinguish between how local governments called on their followers by encouraging them to ‘share your … ’ or to ‘read more and sign up … ’ or through propositions like ‘here you can read more … ’ or ‘now you have a chance to … ’, and rhetorical questions such as ‘are you up for … ’ or ‘do you want to know more … ’. As found in previous studies (Lappas et al., Citation2018, Citation2021) most clusters, regardless of modality, showed how local governments aimed to encourage citizens to take action elsewhere. Similar tendencies were found in topic transparency and participation, which thematically were more oriented towards institutional politics than other topics. Here, a common call included information on how to follow the assembly meeting via web-tv, or where and when developmental and planning meetings would take place offline. Previous research by Lappas et al. (Citation2021), Lai et al. (Citation2020), and Molinillo et al. (Citation2019) on followers’ engagement and willingness to participate show that the online aspect is important to keep followers engaged and encourage participation. Local governments’ insistent redirection of followers to the web pages can be detrimental to their participation in the long run, particularly if it is not balanced with dialogue on the platform itself. However, over the longer term, it was possible to notice a small increase in the relative use of calls’ weights against the entire corpus, particularly calls to participate ().

Again, these minor increases coupled with an overall increase in the topics of growth and development, and transparency and participation from 2016 on suggests a slight adaption to incorporate more participation, at least as a topic.

While calls increased, governments still predominately focused on one-way styles of information dissemination and seemed to lean mostly on principles such as information, transparency and alerting, and different local governments connected more strongly to different topics. Through the concept of alignment (Volk & Zerfass, Citation2018), patterns in style indicated that long-term goals of growth and geographical location may result in governments leaning more or less firmly into different types of content and styles of communication. For instance, Jokkmokk, the most northern municipality in the material, located some 1000 kilometers from Stockholm, focused more on place branding and marketing (). Overall, branding manifested mostly in careful and non-controversial expressions.

Figure 5. Local governments distribution over topics.

In Säffle one may get the opportunity to work in ‘Sweden’s youngest city’ which was marked with the hashtag #Swedensyoungestcity. In particular, positioning as branding communication often utilized the surrounding nature as a resource for identity creation, thus basing the identity in something local and possibly unique. For instance, the communication of most northern municipalities drew on a specific style that contrasted snow-filled winters with northern lights and warm summers with midnight sun, but also on humor bound to a specific practitioner’s persona:

–15 and the sun is shining! We would like to thank SJ (eds. National Railway Company) for all possible population growth, even if its temporary due to canceled trains! Thanks! <3 (Writers’ translation, Jokkmokk Municipality, February 2012).

Lycksele municipality was perhaps most explicit in that they ended almost all their posts with a combination of hashtags that included #thecityinLappland, thus firmly communicating a position in relation to its geographical position and the surrounding nature. A stylistic pattern in topic nine was more emotive and less informative and neutral than discourse found in other topics, particularly when looking at top words. For instance, in the topic ‘weather, nature, and marketing’ it was possible to identify an emotive and positive discourse through the sheer number of positive adjectives in the top words (). Similarly, and as noted in previous research (DePaula et al., Citation2018; Lai et al., Citation2020; Lappas et al., Citation2021) dissemination of favorable information was also present here in, for instance, a range of job ads in the topic ‘schools and education’ (see, ). Here, their composition was mainly structured through emotional appeals interlinked with ‘caring’ professions. In the topic ‘business and entrepreneurship’, the emotive style was present when local governments talked about local businesses. Returning to the topic of weather, nature and marketing, this emotionally charged style connected in part to a feeling of pride for the local community. For example, followers were encouraged to share their favorite photos or ‘like’ and comment on photos with local motifs posted by local governments. Citizens were also encouraged to participate in marketing in other ways and to construct and share their (or their local government’s) construction of their location place with the outside world:

Luleå archipelago is one of the most beautiful in the country, and we are proud of that! We hope you are as proud as we are and are happy to show to the outside world. Therefore, we want to give you a gift in the form of a sticker that you can attach to your boat. Feel free to take a photo of the sticker when it is in place and tag with #Luleå in social media and you will help us spread the image of Luleå as a boat and archipelago city. You can also compete with your best boat picture […] (Writers’ translation, Luleå Municipality, June 2016).

In a more local setting topic tap water issues, revealed stylistic patterns due to developments during the studied period, and developments that needed to be addressed by maintenance or crisis communication. Local governments like Forshaga, Hammarö, Karlstad, Norrtälje and Skellefteå had issues with the provision of tap water during 2010–2017 and used Facebook to provide information and updates about water quality, boiling recommendations, testing results, updates on repairs, and places where water tanks with tap water had been placed (). Skellefteå, in particular, suffered an outbreak of cryptosporidium in their water supply that triggered extensive and continuous updates. Other examples from, for instance, Helsingborg Municipality, showed how Facebook could be used to provide quick updates on water pollution status as well as the use of Google maps to tag and visualize which areas were affected. The latter example also highlights the potential that Facebook and other social media have for crisis communication; and in the specific case of Facebook, a style of communication based on functions that allow for the integration of content from other platforms and services.

Another distinct style of communication manifested by closer readings of topic nine, in particular. In the intersections between positive adjectives, nature, and weather there were posts and messages that drew on similar resources as branding and identity building, but more closely resembled interactions like small talk or similar everyday forms of speech. Small talk, or speaking about something trivial, also holds parallels Jakobson’s and Sebeok (Citation1960) view; that is, both making sure the channel works, as well as attracting citizens’ interest and future interest. In the material, this was executed in different ways:

Good morning my dear friends! Today we can guarantee there are no mosquitos!:) –40.5 degrees Celsius and that below zero. No insect repellent BUT long sleeves required.;) (Jokkmokk’s Municipality, February 2012).

Happy weekend from a sunny Säffle wishes Säffle Municipality! (Writers’ translation, Säffle Municipality, July 2017).

This is what Klarälven [a river] looked like this morning. It will probably be a little warmer on the way home today, even if you probably need gloves. Now autumn is here for real. What do you think, do you like it or not? (Writers’ translation, Karlstad, September 2013).

Speaking about the weather can be the sort of trivial speech where speech itself is the goal; at least when we compare such speech to local governments ideals, tasks, and mandates. Interestingly, some of the original posts here are in English, which potentially signals that the target audience was perhaps outside the inner circle of local citizens, and where extreme weather is used as a resource to attract attention. Again, mixing such trivial talk about the weather with activities was a distinct style of communication, in particular among the four northernmost municipalities:

–29 Celsius. Man kan klaga på kylan eller så kan man göra som X // –29 Celsius. Complain or go out and do something about it:) Bike Life in Swedish Lapland #luleå #fatbike #vinter (Luleå Municipality, 2016, January).

Posts like these were particularly common in the topic weather, nature, and marketing, together with positive adjectives (), and humor. These posts had less to do with information exchange and could instead be understood as phatic communication. Phatic communication is focused on forming social harmony and maintaining a social connection (Jakobson & Sebeok, Citation1960; Malinowsky, Citation1923; Miller, Citation2017). In particular, communication interpreted as phatic provides a stark contrast to the type of information or messages that are characteristic of governments. While critics such as Miller (Citation2017) have argued that phatic communication on social media may reinforce a sort of status quo, that is drowning calls for social change in the nonsensical, it can have some value as part of a larger strategy. Viewing phatic communication from the perspective of ‘keeping an open channel’ and engaging in casual social talk with followers may result in stronger bonds between an organization and its public and a more enduring channel for both one-way and two-way communication.

Conclusions

The aim of this article was to gain insight into local governments’ use of social media by examining communicative patterns, particularly if and how they promoted social interaction on Facebook. Two questions were asked: what patterns could be found in the content and whether they changed over time, and what patterns could be found in the style of communication and whether they changed over time.

The results of the overall topical content (RQ1) and topics’ distribution over a yearly cycle suggest that the use of social media is institutionalized on a day-to-day business and, in line with the neo-institutional view, needs to be understood in context of the specific organization and its field. Using methodological approaches like the distant reading employed here affords a view of patterns (or ‘themes/discourses’) of recurring communication activities organizations use to achieve their long-term goals (Zerfass et al., Citation2018). Local governments showed some variation in their focus on one set of principles over others, possibly indicating slight divergences in priorities according to the operational/external dimension. Informing and serving were the most common topical patterns as in information on service, maintenance, events, and to a lesser extent, crisis information. These findings are also in line with previous smaller studies (DePaula & Dincelli, Citation2016; Gao & Lee, Citation2017; Lappas et al., Citation2021; Reddick et al., Citation2017). That is, when local governments translate social media goals for Facebook into practice, it seems to be done in line alongside established channels and ways of doing communication; more specifically communication on channels like the local government’s website. Local governments primarily embrace the technical infrastructure of social media, while social aspects are pushed somewhat to the side. However, certain tendencies in the content point to an increase in topics dealing with participation, and yet even here participation (and citizens’ attention) is directed elsewhere.

A drawback to this type of methodological approach is that variations in both topical content and local governments’ choice of different topics can also be determined by less visible principles such as organizing (e.g., Fredriksson et al., Citation2018). How an organization decides to organize its communication activities may deeply impact which goals are pursued where and is indeed hard to pinpoint through only distant reading and content analysis. Further contextual knowledge and a theoretical departure that begins with the organization is crucial to interpret the results. To gain further insight into the question of strategy, future research should continue using conventional approaches such as interviews and elicit distant reading as a complement, but also consider the relationship between an organization’s social media presence and other channels, thus taking a more systematic approach regarding how an organization affects strategy.

One key discussion in the field of strategic communication that has been particularly relevant for social media is the strain between openness and control (e.g., Botan, Citation2017; Fredriksson, Citation2021; Macnamara & Zerfass, Citation2012; Smith, Citation2015) Again, by using an approach like distant reading it was possible to discover larger patterns capturing these strains. In terms of patterns in style of communication (RQ2), local governments managed to appear transparent by using Facebook to re-mediate messages from institutional sources, particularly messages already published on the web. Interaction as a principle was less salient in the material as a whole when looking purely at the content. This particular pattern became more explicit in close readings of calls as they too signaled control, as in control of where and when issues and questions were open for discussion. Calls very seldom introduced Facebook as a space for discussion or deliberation. Patterns in posts containing calls were most often directed either toward the web page or an offline setting, findings that are also in line with previous studies (Bonsón et al., Citation2015; Lai et al., Citation2020; Lappas et al., Citation2021). Policies often constructed the web page as the space for such concerns (Baltz, Citation2020); as directing questions and concerns elsewhere partly reconnects to issues of control, but can also be seen as a tactic to sanctify Facebook as a space for other content. One limitation of this study is that it does not engage with comments, yet redirecting followers for more information can be viewed as a nice way of saying: no comments or questions here please!

The topic modelling and close readings of topics revealed two other stylistic patterns that ‘shared’ resources. Nature, weather, and landscapes were linguistic resources for both positioning (as means to articulate uniqueness to stand out among peers) and in casual phatic and social talk. One of the main contributions of this paper is to extend the latter point: governments are adapting even further to a ‘social media discourse’, by speaking about the mundane, trivial, or ordinary (e.g., Miller, Citation2017). As a distinct style of communication, it addresses a basic and fundamental ideal within strategic communication: social communion. In both positioning and social talk, as illustrated through topic nine (), local governments employed a style of communication laden with more positive adjectives in relative terms. A positive, value-laden, and emotive communication style also provides a stark contrast to the otherwise neutral, factual, and grey language of bureaucracies and administration. Such reoccurring language signals strategy: local governments are concerned with their relations and brand, and with tying positive connotations to it.

Implications for strategic communication and practitioners of social media

In the introduction to this paper, the approach was that the lives of organizations are characterized by uncertainty and that organizations seek stability and continuity. It was also suggested that social media can be perceived as a source for uncertainty, but also helps to create stability through the opportunities for interaction the technologies provide. Communication and interaction on social media might become a way of trying to establish meaning and create stability. However, this requires that organizations are transparent and open about what they do, and that they listen to opinions of their constituency or audience (Macnamara, Citation2016, p. 145), or that they at least balance listening with other activities (Volk & Zerfass, Citation2018, pp. 436–7). That is, organizations need to embrace the idea that ‘communication is a process that is interactive by nature and participatory at all levels’ (Van Ruler, Citation2018, p. 379). In the material, security and stability mainly seem to be a result of local governments using reoccurring one-way communication based on secure institutional sources, and by steering much of the interaction away from the platform. The result is that certain goals such as transparency and uniformity may be reached by explaining what the organization does and convey information of varying importance to the citizens. As argued by Baltz (Citation2020), this seems in fact to be a result of strategy, and an attempt to control the flow and content of information.

Of course, not all communication needs to be two-way (Van Ruler, Citation2018), but leaning too much on one-way communication to maintain stability ignores the fact that organizations and their image are shaped through a collective process. In this case citizens are key in constituting the stability sought after. Again, as (Volk & Zerfass, Citation2018, pp. 436–7) notes, there must be a balance. If organizations listen too little, they may appear arrogant, if they listen too much, they can appear to be ‘headless chickens.’ Also, to reiterate the points made by Lai et al. (Citation2020) and Molinillo et al. (Citation2019), the online aspects were important to keep followers engaged and encourage participation. Mixing the content and letting each channel be itself without being radically different should therefore be a cornerstone of any organizational strategy. The inherent characteristics and social logic of the various channels should be acknowledged when organizations reason about how media, seen as a system, is used to support achievement of organizational goals.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Avery, E. J., & Graham, M. W. (2013). Political public relations and the promotion of participatory, transparent government through social media. International Journal of Strategic Communication, 7(4), 274–291. https://doi.org/10.1080/1553118X.2013.824885

- Baltz, A. (2020). A longitudinal analysis of Swedish local governments on Facebook: A visualisation of communication. Nordicom Review, 41(2), 147–162. https://doi.org/10.2478/nor-2020-0020

- Bellström, P., Magnusson, M., Pettersson, J. S., & Thorén, C. (2016). Facebook usage in a local government: A content analysis of page owner posts and user posts. Transforming Government: People, Process and Policy, 10(4), 548–567. https://doi.org/10.1108/TG-12-2015-0061

- Blei, D. M. (2012). Probabilistic topic models. Communications of the ACM, 55(4), 77–84. https://doi.org/10.1145/2133806.2133826

- Bonsón, E., Royo, S., & Ratkai, M. (2015). Citizens’ engagement on local governments’ Facebook sites. An empirical analysis: The impact of different media and content types in Western Europe. Government Information Quarterly, 32(1), 52–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2014.11.001

- Botan, C. H. (2017). Strategic communication theory and practice: The cocreational model. John Wiley & Sons.

- Castells, M. (2009). Communication power. Oxford University Press.

- Criado, J. I., & Villodre, J. (2021). Delivering public services through social media in European local governments. An interpretative framework using semantic algorithms. Local Government Studies, 47(2), 253–275. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2020.1729750

- Czarniawska, B., & Joerges, B. (1996). Travels of ideas. In Czarniawska. B. & Sevón, G (Eds.) Translating organizational change (pp. 13–48). de Gruyter.

- DePaula, N., & Dincelli, E. (2016). An empirical analysis of local government social media communication: Models of e-government interactivity and public relations. Proceedings of the 17th international digital government research conference on digital government research,

- DePaula, N., Dincelli, E., & Harrison, T. M. (2018). Toward a typology of government social media communication: Democratic goals, symbolic acts and self-presentation. Government Information Quarterly, 35(1), 98–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2017.10.003

- DiMaggio, P. J., & Powell, W. W. (1983). The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. American Sociological Review, 48(2), 147–160. https://doi.org/10.2307/2095101

- Fredriksson, M. (2021). Organisationer och kommunikation (M. Fredriksson, Ed; (1). Studentlitteratur.

- Fredriksson, M., & Edwards, L. (2019). Communicating under the regimes of divergent ideas: How public agencies in Sweden manage tensions between transparency and consistency. Management Communication Quarterly, 33(4), 548–580. https://doi.org/10.1177/0893318919859478

- Fredriksson, M., Färdigh, M., & Törnberg, A. (2018). Den kommunikativa blicken–En analys av principerna för svenska kommuners kommunikationsverksamheter. University of Gothenburg.

- Fredriksson, M., & Pallas, J. (2015). Strategic communication as institutional work. In Holtzhausen. D. & Zerfass. A (Eds.) The Routledge Handbook of Strategic Communication, 143–156.

- Fredriksson, M., & Pallas, J. (2016). Diverging principles for strategic communication in government agencies. International Journal of Strategic Communication, 10(3), 153–164. https://doi.org/10.1080/1553118X.2016.1176571

- Gao, X., & Lee, J. (2017). E-government services and social media adoption: Experience of small local governments in Nebraska state. Government Information Quarterly, 34(4), 627–634. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2017.09.005

- Gulbrandsen, I. T., & Just, S. N. (2016). In the wake of new media: Connecting the who with the how of strategizing communication. International Journal of Strategic Communication, 10(4), 223–237. https://doi.org/10.1080/1553118X.2016.1150281

- Guo, L., Vargo, C. J., Pan, Z., Ding, W., & Ishwar, P. (2016). Big social data analytics in journalism and mass communication: Comparing dictionary-based text analysis and unsupervised topic modeling. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 93(2), 332–359. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077699016639231

- Heide, M., von Platen, S., Simonsson, C., & Falkheimer, J. (2018). Expanding the scope of strategic communication: Towards a holistic understanding of organizational complexity. International Journal of Strategic Communication, 12(4), 452–468. https://doi.org/10.1080/1553118X.2018.1456434

- Internetstiftelsen. (2020). Svenskarna och Internet 2020 [The Swedses and the Internet 2020] [Report]. Retrived May 3, 2021 from: https://svenskarnaochinternet.se/app/uploads/2020/12/internetstiftelsen-svenskarna-och-internet-2020.pdf

- Jakobson, R., & Sebeok, T. A. (1960). Closing statement: Linguistics and poetics. Semiotics: An Introductory Anthology, 147–175.

- Johann, M., Wolf, C., & Godulla, A. (2021). Managing relationships on Facebook: A long-term analysis of leading companies in Germany. Public Relations Review, 47(3), 102044. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2021.102044

- Lai, C.-H., Ping Yu, R., & Chen, Y.-C. (2020). Examining government dialogic orientation in social media strategies, outcomes, and perceived effectiveness: A mixed-methods approach. International Journal of Strategic Communication, 14(3), 139–159. https://doi.org/10.1080/1553118X.2020.1749634

- Lappas, G., Triantafillidou, A., Deligiaouri, A., & Kleftodimos, A. (2018). Facebook content strategies and citizens’ online engagement: The case of Greek local governments. The Review of Socionetwork Strategies, 12(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12626-018-0017-6

- Lappas, G., Triantafillidou, A., & Kani, A. (2021). Harnessing the power of dialogue: Examining the impact of Facebook content on citizens’ engagement. Local Government Studies, 48(1), 87–106. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2020.1870958

- Lev-On, A., & Steinfeld, N. (2015). Local engagement online: Municipal Facebook pages as hubs of interaction. Government Information Quarterly, 32(3), 299–307. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2015.05.007

- Lidén, G., & Larsson, A. O. (2016). From 1.0 to 2.0: Swedish municipalities online. Journal of Information Technology & Politics, 13(4), 339–351. https://doi.org/10.1080/19331681.2016.1169242

- Lövgren, D. (2017). Dancing together alone: Inconsistencies and contradictions of strategic communication in Swedish Universities. Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis].

- Macnamara, J. (2016). The work and ‘architecture of listening’: Addressing gaps in organization-public communication. International Journal of Strategic Communication, 10(2), 133–148. https://doi.org/10.1080/1553118X.2016.1147043

- Macnamara, J., & Zerfass, A. (2012). Social media communication in organizations: The challenges of balancing openness, strategy, and management. International Journal of Strategic Communication, 6(4), 287–308. https://doi.org/10.1080/1553118X.2012.711402

- Magnusson, M., Bellström, P., & Thoren, C. (2012). Facebook usage in government–a case study of information content.

- Maier, D., Waldherr, A., Miltner, P., Wiedemann, G., Niekler, A., Keinert, A., Pfetsch, B., Heyer, G., Reber, U., & Häussler, T. (2018). Applying LDA topic modeling in communication research: Toward a valid and reliable methodology. Communication Methods and Measures, 12(2–3), 93–118. https://doi.org/10.1080/19312458.2018.1430754

- Malinowsky, B. (1923). The problem of meaning in primitive languages. The Meaning of Meaning, 296–346.

- March, J. G., & Olsen, J. P. (2008). The logic of appropriateness. In R. Goodin, M. Moran, & Rein, M (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Political Science. Oxford University Press.https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199548453.003.0034

- McCallum, A. K. (2002). Mallet: A machine learning for language toolkit. http://mallet.Cs.Umass.Edu.

- Mergel, I. (2013). A framework for interpreting social media interactions in the public sector. Government Information Quarterly, 30(4), 327–334. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2013.05.015

- Mergel, I. (2017). Building holistic evidence for social media impact. Public Administration Review, 77(4), 489–495. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12780

- Metallo, C., Gesuele, B., Guillamón, M.-D., & Ríos, A.-M. (2020). Determinants of public engagement on municipal Facebook pages. The Information Society, 36(3), 147–159. https://doi.org/10.1080/01972243.2020.1737605

- Miller, V. (2008). New media, networking and phatic culture. Convergence, 14(4), 387–400. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354856508094659

- Miller, V. (2017). Phatic culture and the status quo: Reconsidering the purpose of social media activism. Convergence, 23(3), 251–269. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354856515592512

- Molinillo, S., Anaya-Sánchez, R., Morrison, A. M., & Coca-Stefaniak, J. A. (2019). Smart city communication via social media: Analysing residents’ and visitors’ engagement. Cities, 94, 247–255. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2019.06.003

- Montin, S., & Granberg, M. (2013). Moderna kommuner. Liber.

- Norström, L. (2019). Social media as sociomaterial service: On practicing public service innovation in municipalities. University West].

- Plowman, K. D., & Wilson, C. (2018). Strategy and tactics in strategic communication: Examining their intersection with social media use. International Journal of Strategic Communication, 12(2), 125–144. https://doi.org/10.1080/1553118X.2018.1428979

- Qi, P., Zhang, Y., Zhang, Y., Bolton, J., & Manning, C. D. (2020). Stanza: A python natural language processing toolkit for many human languages. arXiv Preprint arXiv:2003.07082. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2003.07082

- Rasmussen, J., & Ihlen, Ø. (2017). Risk, crisis, and social media: A systematic review of seven years’ research. Nordicom Review, 38(2), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1515/nor-2017-0393

- Reddick, C. G., Chatfield, A. T., & Ojo, A. (2017). A social media text analytics framework for double-loop learning for citizen-centric public services: A case study of a local government Facebook use. Government Information Quarterly, 34(1), 110–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2016.11.001

- Regions, S. A. O. L. A. A. (2017). Kommungruppsindelning 2017 – Revidering av Sveriges kommuner och landstings kommungruppsindelning [Municipal group division 2017– Re-vision of Sweden’s municipalities and county councils’ municipal group division]. Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions. https://webbutik.skr.se/sv/artiklar/kommungruppsindelning-2017

- Sahlin-Andersson, K. (1996). Imitating by editing success: The construction of organizational fields. In Czarniawska. B. & Sevón, G (Eds.) Translating organizational change (pp. 69–92). de Gruyter.

- Smith, B. G. (2015). Situated ideals in strategic social media: Applying grounded practical theory in a case of successful social media management. International Journal of Strategic Communication, 9(4), 272–292. https://doi.org/10.1080/1553118X.2015.1021958

- Underwood, T. (2012). Topic modeling made just simple enough. The stone and the shell. https://tedunderwood.com/2012/04/07/topic-modeling-made-just-simple-enough/

- Van Dijck, J. (2013). The culture of connectivity: A critical history of social media. Oxford University Press.

- Van Ruler, B. (2018). Communication theory: An underrated pillar on which strategic communication rests. International Journal of Strategic Communication, 12(4), 367–381. https://doi.org/10.1080/1553118X.2018.1452240

- Volk, S. C., & Zerfass, A. (2018). Alignment: Explicating a key concept in strategic communication. International Journal of Strategic Communication, 12(4), 433–451. https://doi.org/10.1080/1553118X.2018.1452742

- Wæraas, A., Bjørnå, H., & Moldenæs, T. (2015). Place, organization, democracy: Three strategies for municipal branding. Public Management Review, 17(9), 1282–1304. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2014.906965

- Wæraas, A., & Byrkjeflot, H. (2012). Public sector organizations and reputation management: Five problems. International Public Management Journal, 15(2), 186–206. https://doi.org/10.1080/10967494.2012.702590

- Wukich, C., & Mergel, I. (2016). Reusing social media information in government. Government Information Quarterly, 33(2), 305–312. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2016.01.011

- Zerfass, A., Verčič, D., Nothhaft, H., & Werder, K. P. (2018). Strategic communication: Defining the field and its contribution to research and practice. International Journal of Strategic Communication, 12(4), 487–505. https://doi.org/10.1080/1553118X.2018.1493485