ABSTRACT

This study extends the existing research on C-suite communication and corporate communicators by adding the perspective of the supervisory board. Building on principal-agent theory and the public arena model the supervisory board chair’s communicator role is conceptualized, and established and stakeholders are identified. Based on 28 qualitative expert interviews with supervisory board chairs, public relations, and investor relations managers from 10 DAX and MDAX companies, the study highlights the objectives for the chair’s communication as well as responsibilities within the public relations and investor relations departments. The findings show that transparency and the establishment and maintenance of relationships are the main objectives of the chair’s communication. Furthermore, the findings show that there is rarely a clear responsibility within the public relations or investor relations functions for the chair’s communication. Closer cooperation leads to more professionalized chair communication – but not necessarily more active external communication. The article contributes to communication management and strategic communication research by highlighting the conceptual-theoretical challenge of the communication of the supervisory board because its actions set the framework for the corporate strategy.

Introduction

Public relations research highlights the Chief Executive Officer (CEO) role as a communicator. The communication and positioning of the CEO have also become an established field of research. CEOs can be seen as agents in managing strategic communication (Zerfass et al., Citation2018) and new phenomena like CEO activism (Bojanic, Citation2023). However, only some studies have analyzed the communication of the board of directors (Brennan et al., Citation2010; Palmieri, Citation2014). The chair of the board does not get much attention in this context. This seems peculiar considering that the chairperson plays a decisive role in corporate governance and shareholder relations.

In the context of corporate governance research, the supervisory board has long been a much-noticed subject in the fields of economics and law. Concerning the communicative tasks of the supervisory board, reference is made exclusively to the disclosure obligations (Grundei & Zaumseil, Citation2012). However, the supervisory board’s monitoring activities and corporate governance can only be perceived externally if they are communicated to all stakeholders through appropriate communication measures. So far, communication science has not yet extended its view to the supervisory board’s communication.

And the tide is changing. Investors demand access to the chair of the board when investing in corporations. Several corporate governance codes call for an engagement of the board with the companies’ stakeholders. For instance, the German Corporate Governance Code (GCGC) adopted a recommendation calling for more communication between the supervisory board and investors (Regierungskommission, Citation2017). The UK Corporate Governance Code recommends that the chair should seek regular engagement with major shareholders to understand their views on governance and performance against the strategy (Financial Reporting Council, Citation2024).

This development allows public relations research to analyze the supervisory board’s new communications role. Moreover, it raises the question of how these new dynamics can be integrated into established communications practices. Representing the company and communicating about the business tends to remain in the domain of management thought. But there are topics that only the chair of the board can talk about, such as corporate governance, remuneration, etc. This poses a significant challenge to corporate communications officers: they need to adhere to the law with the clear boundaries of the board’s communication while addressing this new demand from investors.

The study contributes to research on C-suite communication by adding the perspective of the supervisory board. It is the first to conceptualize the communicator role of the chair of the supervisory board as well as relevant stakeholders. It highlights the implementation of the chair’s communication in a communication management process. In short, this exploratory study addresses the questions on objectives and responsibilities for the chair’s communication.

Literature review

This literature review aims to give an overview of communicator research to show that chairpersons have so far not been perceived as relevant corporate communicators. Furthermore, it will present insights into corporate governance systems and basic assumptions from previous communication management research to highlight the foundation and challenges for the communication of the chair of the supervisory board.

Research on corporate communicators has a long tradition in public relations and communication science. But the research focuses on public relations practitioners (e.g., Dozier & Broom, Citation1995) or, nowadays, communication managers (e.g., Falkheimer et al., Citation2016) as professional communicators. Regarding the communication of corporate directors, the communication and positioning of the CEO (Zerfass et al., Citation2016) have also become an established field of research. The communication of other board members, on the other hand, has hardly been researched. However, the Chief Financial Officer (CFO) is considered to play a leading role in communication with capital market players (Nolop, Citation2012). In summary, the communication and positioning of the CEO, CFO, and other members of the company management represents a challenge for communication management, especially with new phenomena like CEO activism (Bojanic, Citation2023).

Depending on the corporate governance system, corporations are governed by either a unified administrative board (known as a one-tier or monistic system, i.e., the Anglo-American model) or a separation between the executive and supervisory board (known as a two-tier or dualistic system, e.g., applied in Germany). Only some studies have analyzed the communication of the board of directors, especially the communication in takeover bids (Brennan et al., Citation2010; Palmieri, Citation2014) – one of the few situations when the entire board is obliged to speak. All disclosure obligations by the supervisory board will be discussed in the next chapter of this paper. However, the communicative tasks and measures of the chair of the board of directors in the monistic board nor the chair of the supervisory board in the dualistic system have not yet been discussed conceptually or empirically.

Academically, supervisory board chairs have hardly been perceived as communicators. Concerning the research on corporate governance, the supervisory board has long been a subject of attention in economics and law (Grundei & Zaumseil, Citation2012). In this context, the function of the supervisory board is emphasized with its role to establish transparency and trust in corporate management. Moreover, the structures and required competencies within the board are discussed (Kuck, Citation2006). Concerning the communicative tasks of the supervisory board, reference is made exclusively to the disclosure obligations. Thus, a communication science perspective on the supervisory board’s communication is necessary.

Corporate governance and its relevance for communication research

Corporate governance is a comprehensive analytical concept that combines many different economic phenomena. Today, it is one of the most discussed management topics (von Werder, Citation2009). Principal-agent theory (Jensen & Meckling, Citation1976) makes a great contribution to the explanation of corporate governance and provides a theoretical basis for the function of the supervisory board as a body. The basic idea is that one party (principal) delegates a certain task to a second party (agent), which is to perform a certain activity or make a certain decision for the principal. This division of labor results in a different distribution of risk, information, and interests between the principal and agent.

To control the company’s management, one organizational approach is to implement a control body – the supervisory board. The introduction of such an institutionalized body creates a two-tier principal-agent relationship (Lentfer, Citation2005, pp. 149–152; Metten, Citation2010, p. 48) (): On the first level, the shareholder (principal) elects the supervisory board (agent) to represent their interests. This constitutes the requirement for transparent communication of the supervisory board. At the second level, the supervisory board (principal) appoints but also controls the executive board (agent). This relationship exhibits considerable information asymmetries since members of the supervisory board rely on information from the executive board about operational and strategic topics to fulfill their control duties. This results in a challenging situation for strategic communication. The supervisory board has a clear responsibility to inform stakeholders about its duties. At the same time, however, the executive board, for and foremost the CEO, is the central spokesperson both internally and externally. The question arises when and how the supervisory board can speak to internal and external stakeholders and who will support it in doing so.

The two-tier corporate governance system was first adopted in Germany, Austria, Netherlands, China, and others (Lutter, Citation1995). It is defined by the institutional separation of the executive board and the supervisory board. As the controlling body, the supervisory board sets the framework for corporate governance and thus also the actions of the executive board, while the executive board is responsible for strategic and operational management (Tüngler, Citation2000). The supervisory board represents the interests of the shareholders and, in co-determined supervisory boards, also the interests of the employees. The representation of employees on the supervisory board is a distinctive feature of the German co-determined separation model and extends the supervisory board’s control function to include the reconciliation of interests (Hutzschenreuter et al., Citation2012).

In contrast, the monistic (one-tier board) system of corporate governance is the corporate governance system predominantly found worldwide – particularly in the Anglo-American world. In the monistic system, there is no institutional separation between the management and control functions.

The key difference between the two governance systems is the separation between the management and the oversight of the company. In the dualistic system, the supervisory board is meant to provide independent oversight of the management, whereas, in the one-tier system, the board of directors has a more direct role in managing the company. The dualistic system is designed to ensure that there is a clear separation of powers, with the supervisory board providing independent oversight – however, based on the information provided by the executive board. This results in an independent communication function of the chair for the respective company. The management and oversight of the company are strategically significant for the survival and success of the company. While CEO communication is often part of strategic communication management (Zerfass et al., Citation2018), there is no research so far, on the strategic communication of the chair of the board of directors nor differences between the corporate governance systems. Due to the closer cooperation in the one-tier system, it could be assumed that there is also close coordination in terms of communication. For this reason, the dualistic system is particularly interesting, as there is an organizational separation – although both bodies discuss extremely relevant strategic issues for the corporation.

However, global public relations theory shows that public relations are empowered by the dominant coalition or by a direct reporting relationship to the senior management (Gregory, Citation2018; Grunig et al., Citation2002; Zerfass & Franke, Citation2013). These findings can also be confirmed for the investor relations function (Binder-Tietz et al., Citation2021). But can the same communications manager report to the CEO and the supervisory board chair? To avoid obvious conflicts of interest for communication managers, the organization of the chair’s communication must be challenged. So far, there is no research on the communicative support of the board of directors in either the corporate governance system or research on the organization of the chairperson’s communication.

Challenges for previous research in communication management

Moreover, the communication of the supervisory board poses a conceptual-theoretical challenge for research in communication management. Thus, basic assumptions of previous communication management research must first be questioned. The previous research poses that the objectives for communication are derived from the corporate strategy (Gregory, Citation2018; Zerfass & Viertmann, Citation2017). This understanding cannot be applied to the communication of the supervisory board due to its formal structural position.

Ulrich (Citation2014) shows in a systematic literature review that the connection between corporate governance and strategy has been neglected so far. The 20 studies identified relate exclusively to the monistic system of corporate governance. Within the two-tier system, the executive and supervisory boards have a distinct division of responsibilities under the German Stock Corporation Act (§§ 76–116 Aktiengesetz). The supervisory board monitors the actions of the executive board and in doing so also the implementation of the corporate strategy.

Although the supervisory board and its chair function as a “sounding board” (Grundei & Graumann, Citation2012, p. 285) to the executive board, they are not responsible for or subject to the corporate strategy. It is their responsibility to review and challenge the company’s strategy. Objectives for the communication of the supervisory board must therefore theoretically be derived from its monitoring function. So far, there is no research on the objectives of communication for the board of directors in either corporate governance system.

This leads to two research questions:

RQ1:

What objectives are pursued in the communication of supervisory board chairs?

RQ2:

Who is managing the communication of supervisory board chairs?

Following this initial literature review, the next step is to develop the conceptual basis for supervisory board communication in the dualistic system.

Conceptual work: Establishing the chair of the supervisory board as a corporate communicator

The supervisory board chair is not an independent body but plays a special role in the work of the supervisory board. The supervisory board as a body is not permanently active but acts within meetings. In contrast, the supervisory board chair is in constant contact with the executive board, so they act and react on an ongoing basis. The success or failure of the company’s development, therefore, is often decisively determined by the person chairing the supervisory board (von Schenck, Citation2013, p. 132).

Peus (Citation1983, p. 16 ff.) divides the tasks of the chair are divided into three areas:

coordination and management of the supervisory board proceedings,

representation of the company in the submission of certain declarations to the commercial register,

representation of the supervisory board vis-à-vis the executive board and the annual general meeting.

They function as spokespersons for the supervisory board and therefore have a clearly defined communication mandate for the company. Some topics are only decided by the supervisory board, such as appointments and compensation of executive and supervisory board members. The result is that only the chair of the supervisory board can discuss these topics with stakeholders.

Thus, communication is a principal component of the task of supervisory board chairs. Internally, the separation of functions in the dualistic corporate governance system creates a knowledge asymmetry between the supervisory board and the executive board. The supervisory board performs its supervisory duties based on the reports of the executive board (Diederichs & Kißler, Citation2008). The chair has a hinge function to optimize the communication between the supervisory board and the executive board. Externally, the supervisory board has several disclosure obligations and increased additional voluntary communication with stakeholders performed by the chair.

Stakeholder of the supervisory boards’ communication

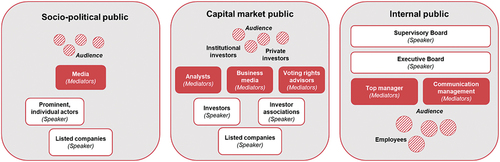

To conceptualize the stakeholders of the chair’s communication, the public arena model (Hilgartner & Bosk, Citation1988) is used to approach the concept of the public sphere. Public arenas differ with regards to specific actors, audiences, and in rationality how topics are selected and discussed. Hereby, two public arenas are identified as relevant for chairs’ communication: the sociopolitical public and the capital market public.

The sociopolitical public is a “sounding board for society-wide problems and proposed solutions” (Zerfass, Citation2010, p. 201). In this arena, impulses from other public arenas are taken up and condensed into an overarching agenda. In doing so, it relies on the mediating power of the media.

Among the many public arenas in which corporations engage their stakeholders (Freeman, Citation1984), capital markets stand out because financial audiences directly impact the viability of an enterprise. The capital market public has specific actors and distinct topics, which do not necessarily have to be part of the discourse in the sociopolitical public. Companies, in turn, form their own communication spaces “in which a specific cross-section of topics and structures from other spheres is reflected” (Zerfass, Citation2010, p. 201). Further external public arenas are assumed to be irrelevant due to the function of the supervisory board.

Furthermore, a distinction can be made between different actors and roles within the two public arenas: Speakers, mediators, and the audience. This conceptual part aims to show relevant stakeholders for the chair’s communication, and that supervisory board chairs (can) function as speakers in different arenas.

Regarding the audience: In the sociopolitical public the audience consists, in principle, of all citizens of society or a respective country. In the capital market public, the audience consists of private and institutional investors who hold shares in companies listed in respective markets. Within a stakeholder management framework, however, shareholders are a key corporate audience – one particularly insistent on direct interaction with members of the C-suite (Hoffmann, Citation2019) – and now also the supervisory board chair. Thus, especially (institutional) investors can be considered the most important stakeholder group for the chair’s communication.

Regarding mediators: Media are important mediators in both arenas and therefore journalists are relevant stakeholders. The role can be considered even more prominent in the sociopolitical public. In the capital market public, in particular, analysts (Binder-Tietz & Frank, Citation2021) and voting rights advisors (Schwarz, Citation2013) can be identified as additional intermediaries, as they provide specific services to investors as information intermediaries. Journalists can be considered a relevant stakeholder group for the chair’s communication in both arenas. Voting rights advisors often address corporate governance issues, so it can be assumed that they have a natural interest in the supervisory board and are therefore relevant stakeholders in its communication. In contrast, analysts tend to focus on the operational development of the company, which is the responsibility of management, so they may be less relevant for supervisory board communication.

Regarding speakers: Listed companies as collective actors function as speakers in both arenas. The role of corporate spokespersons is conducted by communication professionals from public relations and investor relations departments as well as high-ranking corporate representatives. Besides the executive board members, the chair of the supervisory board can speak for the company – as the elected spokesperson of the committee.

In addition, however, supervisory board chairpersons can also express themselves as experts or intellectuals (Neidhardt, Citation1994, p. 14) on topics that have nothing to do with the company. This role of the chair as an individual speaker can be assumed especially for the sociopolitical public.

In the capital market public, individual institutional investors are also relevant as speakers – in situations when they try to gain attention for their specific interests. The same applies to shareholder protection associations as they represent the interests of private investors.

In addition, the corporate public within the company is also relevant for the communication of the chair. First, the communication within the supervisory board itself – because the chair is the elected representative of the body. In addition to representing the board at the annual general meeting, internal information dissemination is one of their main tasks: the chair convenes and chairs the meetings of the board, and they are responsible for the agenda, and the coordination of the committees as well as with the executive board. While corporate governance research focuses on the written information supply, there are no studies on communication within the board.

Second, the CEO or the executive board is particularly noteworthy – while being a speaker internally and externally for the company itself. From the perspective of corporate governance research, the CEO, respectively the executive board, are the only internal stakeholders in the chair’s communication. The focus here is on the provision of information to the supervisory board, and thus a prosperous cooperation and communication between the two bodies (Seibt, Citation2009). Von Schenck (Citation2013, p. 136) argues that a weekly telephone call should be the minimum that supervisory board chairs should use to maintain contact with the CEO. So far there have been no studies on communication between the chair and the CEO.

Third, this study argues that there are more relevant stakeholders inside the company: Managers play a key role as mediators between the company’s management and its employees. While top managers report to the executive board, it is not yet clear if there is also communication with the supervisory board chair. This could offer the supervisory board a direct view of specific issues as well as of the possible successors for the executive board of the company (Seibt, Citation2009, p. 400). Direct contact between the supervisory board, executives, and employees is ideally understood as part of a transparent corporate culture in which loyalty is maintained by the employee and the executive board (Leyens, Citation2006, p. 198). In the case of codetermined supervisory boards, the board also represents the interests of employees – another reason communication within the company is of interest. So far there have been no studies on communication between the chair and managers or employees.

provides an overview of the described actors, and thus stakeholders of the chair’s communication in the socio-political public, capital market public as well and the internal corporate public.

Disclosure obligations and voluntary communication of supervisory board chairs

Disclosure obligations arise from the stock market listing and are thus mainly one-way communication measures directed to capital market participants. gives an overview of the disclosure obligations that apply but may vary in most countries and stock markets:

Table 1. Disclosure obligations for the supervisory board.

Overall, the requirements of the legislator and the Corporate Governance Codes in respective countries are leading to more detailed Supervisory Board and Corporate Governance reports. In most cases, this is part of the company’s regular communications, with the investor relations department and, depending on the company, also the public relations department taking on these tasks as part of communications management.

Specifically, this involves the Supervisory Board Report as part of the annual report being one of the central instruments of financial communication. In addition, all public information on the work of the supervisory board is published permanently on the company’s website. These are, therefore, mostly written disclosure requirements. However, the information provided by the supervisory board at the annual general meeting as well as further voluntary public statements shows that communication must not only be in writing.

The recommendation of the several corporate governance codes calling for more engagement between the supervisory board and investors, especially in the UK and Germany can be seen as a turning point for the chair’s external communication. Since investors operate internationally, they also expect similar behavior from chairs in different markets regarding their communication. Based on principal-agent theory, investors elect the supervisory board to represent their interests. Accordingly, they also have a high interest in an exchange with the supervisory board outside the Annual General Meeting.

Furthermore, voluntary communication by the supervisory board chair has not yet been investigated, even if it can be found increasingly in media reports triggered by a corporate crisis. However, the communication of the supervisory board in a crisis is a “competence tightrope walk” (Schilha et al., Citation2018, p. 18), as it must be clarified whether the topics discussed fall within its competence and do not restrict the competencies of the executive board. The same applies to public statements by the chairperson in other situations.

Objectives and definition of supervisory board communication

As shown in the literature review, the objectives of communication must be derived from their function due to the unique position of the supervisory board. In general, the supervisory board has three functions: (1) the control function, (2) the balancing of interests, and (3) the advisory function (Hutzschenreuter et al., Citation2012, p. 719).

According to principal-agent theory, shareholders delegate their control and decision-making authority regarding the executive board to the supervisory board, whereby their greatest risk lies in the unequal distribution of information. The primary objective of the supervisory board’s communication should therefore be transparency about the delegated tasks.

In addition, the supervisory board fulfills a function of balancing interests, as the members of the supervisory board represent both the shareholders and the employees. Overall, as an independent body, the supervisory board should be aware of the various interests of the company’s diverse stakeholders.

Thus, two central objectives of supervisory board communication are:

Content objective: Establish transparency about supervisory and control tasks.

Relationship objective: Establish and maintain (communicative) relationships within the supervisory board itself as well as between the supervisory board and internal and external stakeholders.

On this basis, the following definition is proposed for the communication of the supervisory board:

Supervisory board communication (at listed companies) is defined as all controlled communication processes of supervisory board members that take place within the supervisory board and with internal and external stakeholders. The central objectives are (1) to create transparency about the supervisory and control tasks of the supervisory board and (2) to establish and maintain relationships within the supervisory board and between the supervisory board and the stakeholders. Supervisory board communication includes the fulfillment of disclosure obligations as well as voluntary communication beyond this. As the elected spokesperson of the supervisory board, the chairperson of the supervisory board has special duties and tasks in this regard.

Due to the fact, that the chair of the supervisory board has a special role in coordinating the supervisory board and representing it externally, the following definition of the communication of the supervisory board chair builds on Zerfass and Sandhu (Citation2006, p. 52):

The communication of the supervisory board chair includes all controlled communication activities of the most senior representative of the supervisory board with internal and external and external stakeholders.

Method

A qualitative study using expert interviews was conducted to gain insights into the field of the chair’s communication, which has so far been little investigated.

The selection for the interviews was conducted based on predefined criteria. The study focuses on supervisory boards of listed companies in Germany – representing the dualistic corporate governance system. At first, it was relevant to talk to the chairs themselves as they are experts due to their specific knowledge and unique experience. In addition, the representatives of the investor relations and public relations functions from the same company were also interviewed – together they represent one case. By interviewing communication experts, the aim was to obtain a comprehensive picture covering both perspectives, the company’s communications (objectives) with its stakeholders, as well as the specific communication and objectives of the supervisory board.

In addition, the results of a preliminary content analysis of statements of supervisory board chairs by all 30 DAX and 50 MDAX companies over two years (01.01.2016–31.12.2017) in 15 German media outlets and publicly available analyst reports were used as another guiding selection criterion. Within the content analysis, it was possible to differentiate between five event-related types of communication of supervisory board chairs. The occasion of the communication (regular communication vs. special situations) and the statements made by the chair (statements as part of disclosure obligation vs. voluntary communication) were selected as typifying features. The dichotomy in the analysis between disclosure obligations and voluntary communication is important for a broader understanding that the communication of supervisory board chairs also includes voluntary communication measures. This resulted in the following four types: (1) Disclosure obligations of the chair as part of regular communication, (2) voluntary public communication by the chair as part of regular communication, (3) disclosure obligation of the chair in special situations, and (4) voluntary public communication by the chair in special situations. The content analysis also revealed another type (5) of public communication by supervisory board chairs with no connection to the company. The selected cases were identified within the content analysis. They cover all these types which aims to allow a maximum breadth of information from the expert interviews.

From December 2017 to October 2018, a total of 28 expert interviews (9 chairs, 9 investor relations, and 10 public relations managers) from 10 German blue chip (DAX) and mid-sized (MDAX) companies were conducted. The interviews were 20.3 hours long (1,215.30 minutes); the shortest interview lasted about 23 minutes and the longest interview lasted about 87 minutes. The number of cases and thus interviews was determined by theoretical saturation. It concludes in 10 cases with 28 expert interviews, because one person was the chair of two different companies and one company had one person being responsible for IR and PR.

Interviews were based on a guideline derived from the theoretical findings on supervisory communication described in this paper. The guideline consisted of four main sections: (1) Entry questions begin on a personal level with experiences of the chair’s communication. In addition, questions on the general role of the supervisory board chair and its communication were asked. (2) The organization of the chair’s communication was discussed based on questions of the organizational structure, e.g., resources for communication and coordination within the board and with the executive board. The role of the communication function as part of the organization was also addressed. The third section dealt with the communication management process focusing on the planning and objectives of the chair’s communication. The key questions for the chairs and communication manager in this section differ accordingly due to their different insights into corporate processes. The respondents were asked what the objectives of the chair’s communication are from their point of view, and on the other hand, the objectives derived from the theory (Chapter “Conceptual work: Establishing the chair of the supervisory board as a corporate communicator”) were discussed. Finally, (4) the concluding questions addressed the challenges of the chair’s communication both personally and organizationally. The experts are asked to assess the relevance and future development of the chair’s communication from their perspective.

The interviews were audio-recorded and fully transcribed for analysis. All interviewees were promised anonymization of the interviews. There will be no presentation by case to avoid references back to the companies. The responses were analyzed using a content structuring content analysis (Mayring, Citation2015). Four main categories were used: actors, organization, planning/objectives, and communication measures. Statements were summarized into these main categories and thus, subcategories and characteristics were further differentiated. Selected quotes will be shown in the results section.

Results

The first research question focuses on the objectives pursued in the communication of supervisory board chairs. The theoretical derivation has shown that the chair’s communication must be characterized differently from other personal communication in companies, such as CEO communication. Objectives for the supervisory board communication were derived from the function of the board to ensure the neutral monitoring function. In the interviews, both the goals derived from theory and further goals for the chair’s communication were identified and discussed. In doing so, the perspective and perception of the supervisory board chair as well as those responsible for communications are presented in the following findings. The results are shown along the publics (internal public and capital market/socio-political public) and differentiated by the stakeholder and the objectives of transparency and relationships.

This study relates to Rawlins’s (Citation2008) definition of transparency as “the deliberate attempt to make available all legally releasable information – whether positive or negative in nature – in a manner that is accurate, timely, balanced, and unequivocal, for the purpose of enhancing the reasoning ability of publics and holding organizations accountable for their actions, policies, and practices” (p. 75). In this context, the author elaborates on three qualities of transparency efforts, i.e., participation, substantial information, and accountability. These three qualities are based on the respective rationales, which suggest that transparency should be a process of encouraging “active participation” from stakeholders so that they can make informed decisions (p. 74); transparency is useful only when it contributes to stakeholder’s “understanding” of information rather than merely increasing the amount of information (p. 74); and the transparency is achieved through an organization’s accountable actions, words, and decisions (p. 75).

Communication objectives with internal stakeholders

For the internal public, the following overview shows the communication objectives of stakeholders ()

Regarding transparency, the supply of information can be seen as the most important basis for the work of the supervisory board. However, the communication with the executive board leads to a “double dilemma” (Seibt, Citation2009, p. 392). First, there is an asymmetry of knowledge between the supervisory board and the executive board. Second, this leads to a conflict of interest for the executive board, which must provide the information for its monitoring and evaluation. This results in the objective of ensuring the supply of information for the supervisory board members from the executive board. A supervisory board chair sums this up: “On the one hand, to create a clear picture of the company as a whole for myself, but of course for the entire supervisory board. And, to communicate to the company at an early stage which topics the supervisory board should address. All of this, while ensuring reasonable, constructive cooperation between the supervisory board and the company, represented by the executive board.”

Regarding managers, several chairs stated that they want to clarify technical issues of the supervisory board. In addition, two supervisory board chairs also reported that they hope to gain an assessment of the corporate culture through an exchange with managers. Discussions with executives would provide further access to a better assessment of what is happening in the company. This would also give an impression of the board’s leadership quality. One supervisory board chair described this as follows: “The executive board’s leadership is expressed in who they hire. When I see the people and feel they are all smart, striving, and hardworking, I think the board has made good choices in the selection of personnel. When I also see peat heads running around, then I know something is wrong. Then the numbers will eventually follow. I will question why the executive board surrounds itself with such people.”

Regarding relationships, the representation of different perspectives and positions of the supervisory board members are of particular importance. This objective derives from the inherent function of the supervisory board to represent all interests of the companies’ stakeholders. A supervisory board chair quotes: “When the supervisory board meets, and you as chair of the supervisory board want it to work smoothly, then all members of the supervisory board must be involved beforehand. The agenda must be discussed in advance. You must know what the positions are.” This means that different interests should be integrated into the supervisory board – but these perspectives should be communicated from the supervisory board to the executive board.

Regarding the communication between the supervisory board and the executive board, more precisely the dialog between the two chairs, the primary goal can be seen to establish a trusting cooperation between the two boards. For a new chair of the supervisory board, this means getting to know the people involved and gaining a feeling for how the company is managed and shaped. “The role between the chair of the executive board and the chair of the supervisory board must be very close and trusting and characterized by mutual respect. That is a prerequisite and the main goal” (Supervisory board chair).

Furthermore, Döring (Citation2018, p. 39) describes the connection between corporate success and corporate ethics, which is expressed in the culture of appreciation. The communicative goal of showing managers the appreciation of the supervisory board is addressed by three chairs in the interviews: “It doesn’t mean that you discuss big issues with them, but rather that you show them that you’re very well aware that the success or failure of a company success depends not only on the executive level but in particular on the quality of the managers thereafter” (Supervisory board chair).

Communication objectives with external stakeholders

External communication of the supervisory board includes several disclosure information, mainly in written form, as stated in Chapter “Conceptual work: Establishing the chair of the supervisory board as a corporate communicator”. The following identified objectives go beyond these disclosure obligations and aim to encourage a process of active participation from stakeholders so that they can make informed decisions (Rawlins, Citation2008). For the external public, the following overview shows the communication objectives of stakeholders ():

Regarding transparency, the communication of the chair with all external stakeholders aims to create transparency regarding the supervisory board activities – in addition to disclosure obligations. The chairs aim to reduce information asymmetries – which is one of the most stated objectives of the chair’s communication. The dialog should also help clarify issues specific to the supervisory board so that for example shareholders approve the relevant points when voting at the annual general meeting: “I had very intensive discussions with investor X about the compensation of the executive board, but still couldn’t get him to agree to it in the end. But he at least understood what we were doing, and it is particularly important to me” (Supervisory board chair).

Regarding relationships with investors as well as journalists, the chair’s communication aims to ensure flexibility and the perception of legitimacy that the company has room to maneuver and continue to do so in times of change and crisis (Zerfass & Viertmann, Citation2017, p. 75). “I’m a friend of building those networks or establishing a dialog when the corporate situation is rather pleasant and not in a crisis when I am forced to” (Supervisory board chair).

Through dialog, supervisory board chairs seek to systematically build and maintain resilient networks with relevant external stakeholders. In this context, listening to the expectations of the shareholders is considered crucial so they can be considered in the supervisory board’s decision-making process. “I can already see the appreciation from investors that the chair is listening to their opinions and is taking them seriously. In some cases, their opinion even supports the decision-making – of course not in all cases. […] And it also helps us later at the Annual General Meeting. We do not have any surprises, if the major investors know our direction and that their opinion is included” (Investor Relations manager).

In a few cases, the chair’s communication aims to foster thought leadership regarding corporate governance which lies in the responsibility of the supervisory board: “I mean, what do you want to accomplish? If it contributes to the understanding or positive perception of the company. The company is perceived as a cohesive corporation with an unambiguous strategy, which is also implemented and controlled accordingly. That would be the goal” (Supervisory board chair).

In special situations, such as a crisis, the goal of communication by the supervisory board chair can be to give stakeholders orientation and to communicate the stability of the company: “There is no purpose in itself for the communication of a chair of the supervisory board, but I see the purpose then internally as well as externally, especially in times of times of crisis, to provide orientation and stability” (Supervisory board chair).

Management of the chair’s communication

The second research question focuses on the management and support for the chair’s communication within the investor relations and corporate communications department.

Regarding the personal communication measures of the supervisory board chair in the company, there is no support from the internal communications function. The manner, frequency, and intensity of communication depend on the chair and its communication style.

When it comes to the external communication of the supervisory board chair, findings are different: Disclosure obligations of the supervisory board directed at external stakeholders are fully embedded in the company’s regular communications. The preparation, internal coordination, and publication of the respective measures are managed by the investor relations and public relations departments (depending on the internal set-up of the departments).

Due to the recommendation on an investor dialog in the German Corporate Governance Code, IR officers have addressed the issue. However, relevant processes were established only in those companies in which supervisory board chairs already held discussions with investors or voting rights advisors. An investor relations manager explains the process: “We prepare the roadshow, in terms of content, via the annual general meeting agenda, but also in the selection of investors. We also talk to the investors in advance about the topics. In the same way, the supervisory board chair receives its briefing and then one of us is always present.”

The voluntary communication measures of supervisory board chairs within the socio-political public which were identified in the interviews are official interviews and background discussions with the media, but also voluntary statements made besides the chair’s monitoring duties. In most cases, the PR manager plays an advisory and coordinating role: “In terms of advice, I am of course always happy to be available. But the chair is then also quite free in his decisions, of course” (Public Relations manager).

A further look at the organization reveals that the CEO can be part of the exchange between the supervisory board chair and communications managers. Mostly, this is the case for briefings on quarterly figures, but it is not mandatory. It is particularly noteworthy that all companies surveyed have established an exchange without the CEO. However, in most cases, there is no formal reporting line to the supervisory board. This means that the organizational structure has not been changed.

This could lead to a conflict of interest as one public relations manager describes: “After all, we have to separate. The supervisory board controls the executive board, and we are employees of the executive board and the Group. Therefore, we cannot advise our supervisory board chair too much at the same time. For example, when I write certain e-mails, I never write to both of them – but in a separate email, so it’s separate.”

In summary, there are three constellations identified as to how the management of the chair’s communication can be anchored organizationally. Interestingly, there are differences between the IR and PR departments, which will be discussed below.

No officially defined responsibility for the chair’s communication.

Defined contact person for supervisory board chairs and responsibility within the communications function.

Dedicated communications manager for the chair’s communications, independent of the communications functions.

First, in most companies surveyed, there is no officially defined management or responsibility for the chair’s communications. The exchange between the supervisory board chairs and the communications functions can take place regularly, but also more loosely and on an ad hoc basis – in most cases without the involvement of the CEO. Within the communications functions, the head of the department is usually the contact person for the chair and accompanies any external communication with investors or the media.

Second, in a few companies, especially in the PR departments, there are defined contacts for the chairs who have responsibility for the chair’s communications within the communications function – but this person is not the head of the department. This contact person has defined capacities for the chair’s communications as part of his or her working hours. The expert interviews show that these persons are also directly and more frequently contacted by supervisory board chairs regarding public topics. “Within the spokesperson team, I am responsible for [supervisory board chair]. I coordinate inquiries with him and am his contact person for issues relevant to the public. That takes up about ¼ of my time” (Public relations manager).

Both the chair of the supervisory board and those responsible for communication describe trusting cooperation with efficient coordination of disclosure obligations and voluntary communication. The communication officers are then also responsible for informing other internal stakeholders, especially the CEO and Chief Communication Officer, in the case of voluntary communication.

Third, at one of the companies surveyed, a position has been created that is exclusively responsible for the communication of the supervisory board. Here, organizational structures have changed to facilitate closer cooperation between the players. “One side of my job is the communicative all-around or 360-degree support of the supervisory board and advising the chairman of the supervisory board. Via all communication platforms and all stakeholders” described the communication manager of the chair. This is a special form of organizational structure, which can have considerable advantages, as one person is responsible for the communications management of the chair’s communication.

Furthermore, the findings show that there are differences in the management or responsibilities for the chair’s communication between investor relations and public relations, even within the same companies. The exchange between the supervisory board chair and the investor relations department is based primarily on briefings to the supervisory board after quarterly figures and other relevant occasions, which are often already institutionalized. In these briefings, the views, and expectations of the capital market participants about the development of the company and the sector are presented. In addition, IR managers tend to act on specific occasions, e.g., when organizing and preparing an investor meeting with the supervisory board chair. There is no officially defined contact person in the IR department, but the (unofficial) contacts become established over time. “I believe that we have achieved an excellent standing with the chair in recent years, also from the IR point of view. […] Of course, it takes a little while for people to get to know each other and know that you can rely on each other. But once contacts are established, why shouldn’t I pick up the phone directly?” (Investor relations manager).

In contrast, in the companies surveyed the PR departments are more likely to have a defined contact person with a dedicated capacity for the chair’s communication. Written information is also provided by the PR department, e.g., an evaluation of the media coverage after the quarterly figures. In contrast to the IR departments, however, the support of the supervisory board chair is more often provided directly. The contact with the PR manager is always topic- and situation-dependent, for example, a question about a media report or when communication measures relevant to the supervisory board must be prepared. However, it can be stated that in around half of the surveyed cases, there is a regular personal exchange between the chair and the communication manager on topics relevant to the public. “I would say that we have a personal exchange about every two to three months and then in between on an ad hoc basis. If I have a topic that I want to discuss with him, I approach him and always get an appointment. Or he calls me. […] For all important topics, we always talk with each other ” (Public Relations Manager).

Most PR managers surveyed see themselves in an advisory role for the chair about topics relevant to the public. This advisory role is not mentioned so explicitly by the IR managers surveyed. However, advice is provided during the steps in planning the investor dialog, such as the (pre-)selection of relevant investors or the presentation of the mood of the capital market players.

The difference in the frequency of exchanges and the self-perception of those responsible for communications may be related to the fact that IR departments are usually not as strongly staffed as the PR departments (Hoffmann & Tietz, Citation2019, p. 18), which are thus able to specialize in their tasks and topics.

In summary, it can be stated that a defined responsibility for the chair’s communication within the communication departments leads to more frequent, direct exchanges – but this does not necessarily result in more active communication by the supervisory board chair. Rather, the chairs report that they feel better and more comprehensively informed, especially about how stakeholders perceive the company. This is a valuable resource for their monitoring function and communication. In most cases, those responsible for communications also report, that, through an established exchange, they can better meet the information needs of the supervisory board chairs.

Discussion

The study is the first to reveal the chair of the supervisory board as a new corporate communicator. There are topics that only the supervisory board can decide on, such as the composition and remuneration of the boards, and therefore also speak about. These are strategically relevant topics for a company. It is therefore relevant for strategic communication research and practice to understand what this communication role of the chair includes and to what extent it is part of communication management.

There are distinct reasons for the change in supervisory board communication as an empirical phenomenon from silent controller to active communicator: Firstly, communication is changing within companies, as the professionalization of supervisory board activities has led to an increasingly advisory role in exchange with the executive board (Grundei & Graumann, Citation2012). Regarding external communication, the legal basis remains the same. At the same time, however, disclosure requirements are increasing, and various stakeholder groups have individual communication needs and the desire for dialog-oriented communication relationships with companies (Zerfass & Viertmann, Citation2017). The present study emphasizes the internal perspective by focusing on the objectives and responsibilities for communication by the supervisory board (chair).

The study establishes relevant publics and stakeholders of the chair’s communication. Different stakeholders have expectations of the company’s communication – and in this context also of the chair’s communication. Especially regarding investors, the chair’s dialog is necessary due to the recommendations in various corporate governance codes. Thus, the investor dialog by the chair will become an integral part of investor relations measures – and research will have to follow, as there is yet no knowledge on the subject.

Regarding the objectives of the chair’s communication, the findings show that the theoretically derived objectives determine the actions of the chair. This is particularly interesting since the communication professionals stated that there is yet no explicit definition of objectives for the chair’s communication in the context of communication management. The goals identified in the expert interviews are the result of the experiences of the people and not from a systematic analysis of the situation or the environment. Therefore, the expectations of the stakeholder regarding the chair’s communication are only unconsciously considered, but not systematically as part of a planning phase within communication management processes. This shows the relevance of including the chair’s communication in communication management and strategic communication research and practice.

Regarding the management and responsibility of the chair’s communication, the findings show that clear responsibilities within the public relations or investor relations departments rarely exist. However, all disclosure obligations of the supervisory board and all voluntary communication measures by the chair are an integral part of the company’s communication. The necessity of (own) resources for professional committee work is a question that is discussed in law and economic research on the professionalization of supervisory board activities (Grundei & Graumann, Citation2012; Schilha et al., Citation2018). Having said that, the chair does not necessarily require external communication support, because the chair’s communication is highly relevant to the company. For this reason, the study suggests that it is relevant to have a communication manager responsible for the chair’s communication within the company who knows the internal routines and processes of the communication functions. Supervisory board communication managers need a broad competence profile, as investors and the media as well as internal stakeholders with their unique needs and routines must be addressed. This also includes an understanding of the legal regulations, internal power structures, and the company’s strategy.

The study proposes two options regarding the management of the chair’s communications: (1) defined contact persons in communication functions with dedicated capacities for the chair’s communication, or (2) a dedicated spokesperson for the chair’s communications. Clear responsibilities support closer cooperation between the actors, which can lead to more professionalized chair communication. In addition, findings show that a close and trusting exchange is seen as positive and beneficial for both sides – by the supervisory board chairs and the communications managers alike.

These findings are subject to several limitations. First, the supervisory board is part of the dualistic corporate governance system, which is applied in Germany, and a handful of other countries. The institutional separation of management and control of a company represents a contrast to the monistic corporate governance system. Further studies should investigate this governance system. Second, while satisfactory, the cases chosen for the interviews were identified by a preliminary content analysis of media articles and analyst reports.

Finally, several implications for research can be derived: First, it is necessary to further discuss the communicator role of supervisory board chairs as relevant corporate communicators. This includes their understanding of the relevance of communication for the board as well as the company in general.

Second, the study highlights the need to examine how communication management deals with the requirements of stakeholders regarding the chair’s communication as well as the communication as part of the companies’ communication management in general. For communication scholars, the present findings help to establish a foundation for further analysis in the realms of communications management research.

Finally, the main function of the supervisory board chair is to coordinate the board’s activities and discuss the company’s development with the CEO. Thus, internal stakeholders for the communication such as members of the supervisory board, the members of the executive board, and others, should be analyzed in further detail.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Binder-Tietz, S., & Frank, R. (2021). Analysten und Institutionelle Investoren als Zielgruppen der Investor Relations und Finanzkommunikation. In C. P. Hoffmann, D. Schiereck, & A. Zerfass (Eds.), Handbuch Investor Relations und Finanzkommunikation (pp. 197–213). Springer Gabler.

- Binder-Tietz, S., Hoffmann, C. P., & Reinholz, J. (2021). Integrated financial communication: Insights on the coordination and integration among investor relations and public relations departments of listed corporations in Germany, Austria and Switzerland. Public Relations Review, 47(4), 102075. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2021.102075

- Bojanic, V. (2023). The positioning of CEOs as advocates and activists for societal change: Reflecting media, receptive and strategic cornerstones. Journal of Communication Management, 27(3), 398–413. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCOM-12-2021-0143

- Brennan, N. M., Daly, C., & Harrington, C. (2010). Rhetoric, argument and impression management in hostile takeover defence documents. The British Accounting Review, 42(4), 253–268. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bar.2010.07.008

- Diederichs, M., & Kißler, M. (2008). Aufsichtsratreporting: Corporate governance, compliance und controlling. Verlag Franz Vahlen.

- Döring, F. (2018). Bedeutung von Wertschätzungskultur und Ethik für die Aufsichtsratsagenda. Der Aufsichtsrat, 3, 38–40. https://research.owlit.de/document/6965fd9a-b8ff-35d0-b3fd-435a15a1fd3b

- Dozier, D. M., & Broom, G. M. (1995). Evolution of the manager role in public relations practice. Journal of Public Relations Research, 7(1), 3–26. https://doi.org/10.1207/s1532754xjprr0701_02

- Falkheimer, J., Heide, M., Simonsson, C., Zerfass, A., & Verhoeven, P. (2016). Doing the right things or doing things right? Paradoxes and Swedish communication professionals’ roles and challenges. Corporate Communications: An International Journal, 2(2), 142–159. https://doi.org/10.1108/CCIJ-06-2015-0037

- Financial Reporting Council. (2024). UK Corporate Governance Code, Retrieved February 1, 2024, from https://www.frc.org.uk/library/standards-codes-policy/corporate-governance/uk-corporate-governance-code/

- Freeman, R. E. (1984). Strategic management – a stakeholder approach. Pitman.

- Gregory, A. (2018). Communication management. In R. L. Heath & W. Johansen (Eds.), The international encyclopedia of strategic communication (pp. 216–229). John Wiley & Sons.

- Grundei, J., & Graumann, M. (2012). Zusammenwirken von Vorstand und Aufsichtsrat bei strategischen Entscheidungen. In J. Grundei & P. Zaumseil (Eds.), Der Aufsichtsrat im System der Corporate Governance: Betriebswirtschaftliche und juristische Perspektiven (pp. 279–310). Gabler Verlag.

- Grundei, J., & Zaumseil, P. (2012) (Eds.), Der Aufsichtsrat im System der Corporate Governance: Betriebswirtschaftliche und juristische Perspektiven. Gabler Verlag.

- Grunig, L. A., Grunig, J. E., & Dozier, D. M. (2002). Excellent public relations and effective organizations. Mahwah, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Hilgartner, S., & Bosk, C. L. (1988). The rise and fall of social problems: A public arenas model. American Journal of Sociology, 94(1), 53–78. https://doi.org/10.1086/228951

- Hoffmann, C. P. (2019). Investor relations communication. In R. L. Heath & W. Johansen (Eds.), The international encyclopedia of strategic communication (pp. 1–11). John Wiley & Sons.

- Hoffmann, C. P., & Tietz, S. (2019). Integrierte Finanzkommunikation: Eine Analyse der Zusammenarbeit von Corporate Communications und Investor Relations bei Themen der Finanzkommunikation. Center for Research in Financial Communication, Universität Leipzig.

- Hutzschenreuter, T., Metten, M., & Weigand, J. (2012). Wie unabhängig sind deutsche Aufsichtsräte? Eine empirische Analyse von 527 DAX-Aufsichtsratsmitgliedern. Zeitschrift für Betriebswirtschaft, 82(7–8), 717–744. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11573-012-0590-z

- Jensen, M. C., & Meckling, W. H. (1976). Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs, and ownership structure. Journal of Financial Economics, 3(4), 305–360. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-405X(76)90026-X

- Kuck, D. (2006). Aufsichtsräte und Beiräte in Deutschland: Rahmenbedingungen, Anforderungen, professionelle Auswahl. Gabler Verlag.

- Lentfer, T. (2005). Einflüsse der internationalen Corporate-Governance-Diskussion auf die Überwachung der Geschäftsführung: Eine kritische Analyse des deutschen Aufsichtsratssystems. Deutscher Univ. Verlag.

- Leyens, P. C. (2006). Information des Aufsichtsrats: Ökonomisch-funktionale Analyse und Rechtsvergleich zum englischen Board. Mohr Siebeck.

- Lutter, M. (1995). Das dualistische System der Unternehmensverwaltung. In E. Scheffler (Ed.), Schriften zur Unternehmensführung: Band 56. Corporate Governance (pp. 5–26). Gabler Verlag.

- Mayring, P. (2015). Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse: Grundlagen und Techniken (12th ed.). Beltz.

- Metten, M. (2010). Corporate Governance: Eine aktienrechtliche und institutionenökonomische Analyse der Leitungsmaxime von Aktiengesellschaften. Gabler Verlag.

- Neidhardt, F. (1994). Öffentlichkeit, öffentliche Meinung, soziale Bewegungen. In F. Neidhardt (Ed.), Öffentlichkeit, öffentliche Meinung, soziale Bewegungen, Kölner Zeitschrift für Soziologie und Sozialpsychologie (pp. 7–41). Opladen.

- Nolop, B. P. (2012). The essential CFO: A corporate finance playbook. Wiley-Blackwell.

- Palmieri, R. (2014). Corporate argumentation in takeover bids. John Benjamins Publishing.

- Peus, E. A. (1983). Der Aufsichtsratsvorsitzende: Seine Rechtsstellung nach dem Aktiengesetz und dem Mitbestimmungsgesetz 1976. Carl Heymann Verlag.

- Rawlins, B. (2008). Give the emperor a mirror: Toward developing a stakeholder measurement of organizational transparency. Journal of Public Relations Research, 21(1), 71–99. https://doi.org/10.1080/10627260802153421

- Regierungskommission, D. C. G. K. (2017, February 14): Proposed amendments to Code 2017 published, available at Retrieved February 1, 2024, from. http://www.dcgk.de/en/press.html

- Schilha, R., Theusinger, I., Manikowsky, D., & Werder, A. (2018). Die Rolle des Aufsichtsrats in der Krisenkommunikation: Interdisziplinäre Studie, available at Retrieved February 1, 2024, from https://www.noerr.com/de/newsroom/news/krisenkommunikation-was-kann-soll-und-darf-der-aufsichtsrat

- Schwarz, P. (2013). Institutionelle Stimmrechtsberatung: Rechtstatsachen, Rechtsökonomik, rechtliche Rahmenbedingungen und Regulierungsstrategien. Duncker & Humblot.

- Seibt, C. H. (2009). Informationsfluss zwischen Vorstand und Aufsichtsrat (dualistisches Leitungssystem) bzw. innerhalb des Verwaltungsrats (monistisches System). In P. Hommelhoff, K. J. Hopt, & A. von Werder (Eds.), Handbuch Corporate Governance: Leitung und Überwachung börsennotierter Unternehmen in der Rechts- und Wirtschaftspraxis (2nd ed., pp. 391–422). Schäffer-Poeschel Verlag.

- Tüngler, G. (2000). The Anglo-American board of directors and the German supervisory board - marionettes in a puppet theatre of corporate governance or efficient controlling devices? Bond Law Review, 12(2), 230–269. https://doi.org/10.53300/001c.5364

- Ulrich, P. (2014). Corporate Governance und Strategie: Gibt es erfolgreiche Muster für Strategiewechsel? Zeitschrift für Corporate Governance, 4(4), 157–162. https://doi.org/10.37307/j.1868-7792.2014.04.06

- von Schenck, K. (2013). Arbeitshandbuch für Aufsichtsratsmitglieder. Verlag Franz Vahlen.

- von Werder, A. (2009). Ökonomische Grundfragen der Corporate Governance. In P. Hommelhoff, K. J. Hopt, & A. von Werder (Eds.), Handbuch Corporate Governance: Leitung und Überwachung börsennotierter Unternehmen in der Rechts- und Wirtschaftspraxis (2nd ed., pp. 3–37). Schäffer-Poeschel Verlag.

- Zerfass, A. (2010). Unternehmensführung und Öffentlichkeitsarbeit: Grundlegung einer Theorie der Unternehmenskommunikation und Public Relations (3rd ed.). VS Verlag.

- Zerfass, A., & Franke, N. (2013). Enabling, advising, supporting, executing: A theoretical framework for internal communication consulting within organizations. International Journal of Strategic Communication, 7(2), 118–135. https://doi.org/10.1080/1553118X.2013.765438

- Zerfass, A., & Sandhu, S. (2006). Personalisierung der CEO-Kommunikation als Herausforderung für die Unternehmensführung. In A. Picot & T. Fischer (Eds.), Weblogs professionell: Grundlagen, Konzept und Praxis im unternehmerischen Umfeld (pp. 51–75). dpunkt.

- Zerfass, A., Verčič, D., Nothhaft, H., & Werder, K. P. (2018). Strategic communication: Defining the field and its contribution to research and practice. International Journal of Strategic Communication, 12(4), 487–505. https://doi.org/10.1080/1553118X.2018.1493485

- Zerfass, A., Verčič, D., Wiesenberg, M., & Andrea Catellani, P. (2016). Managing CEO communication and positioning: A cross-national study among corporate communication leaders. Journal of Communication Management, 20(1), 37–55. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCOM-11-2014-0066

- Zerfass, A., & Viertmann, C. (2017). Creating business value through corporate communication: A theory-based framework and its practical application. Journal of Communication Management, 21(1), 68–81. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCOM-07-2016-0059