ABSTRACT

We all occasionally need the help of others whom we do not know well. In four studies, we studied the influence of the facial appearance of both the potential helper and the help seeker on such a decision. In three studies (1a-1c), across different help domains, participants rated a person with submissive facial appearance as more likely to help. This was mediated via the perception of the submissive person as caring and helpful. The notion that submissive individuals will be perceived as more likely to help when a dominant person asks was only supported in the context of financial help. The preference for a submissive potential helper was also found when participant had to choose a helper for themselves (Study 2). (120 words)

We all have moments when we need the help of others for issues as diverse as practical help with a project or information that someone else has or even a loan of money. The question then arises whom to ask? Clearly we would want to ask someone who is likely to be willing to help. Yet, how can we know if someone is likely to be willing to help or not, especially when the prospective helper is not well known to the help seeker? One factor that may determine the assessment of a person’s likely willingness to help is facial appearance.

Facial appearance is one important source of first impressions (Zebrowitz, Citation2004), which are formed rapidly and spontaneously about a person’s character, such as their trustworthiness (e.g. Hareli & Hess, Citation2010; Hess, Adams, & Kleck, Citation2009; Todorov, Citation2008; Zebrowitz, Citation1996), or even their sexual orientation (Rule, Ambady, & Hallett, Citation2009). These impressions then shape subsequent decisions (Bar, Neta, & Linz, Citation2006; Todorov, Dotsch, Porter, Oosterhof, & Falvello, Citation2013; Willis & Todorov, Citation2006). In fact, first impressions of the likeability of a person based on a photo have been shown to persevere even after a real life encounter one month later (Gunaydin, Selcuk, & Zayas, Citation2017).

To the degree that facial appearance cues have been considered in regard to helping behavior, research has focused on the person receiving help. For example, attractive people are more likely to receive help from a stranger (Wilson, Citation1978) and the same is true of baby-faced adults in comparison with more mature looking persons (Keating, Randall, Kendrick, & Gutshall, Citation2003).

The present research, by contrast, focused on the importance of facial appearance for perceived helping intentions. Specifically, we assessed participants’ expectations for a person to help or receive help as a function of the facial appearance of both the helper and the help seeker. We further assessed whether the perception that a person would be likely to help because they either have a caring nature or feel an obligation to help mediates this process.

1. Facial appearance and first impressions

Much of the research on first impressions focuses on facial appearance (Zebrowitz, Citation1997), in line with the observation that, when presented with a complex scene including a person, people tend to focus on the face (Fletcher-Watson, Findlay, Leekam, & Benson, Citation2008). In this context, appearance cues that can signal general dispositions and behavioral intentions are of special relevance. Thus, a square jaw, high forehead, or heavy eyebrows cross-culturally connote social dominance (Keating, Mazur, & Segall, Citation1981; Keating, Mazur, Segall, Cysneiros, Divale, Kilbridge, Komin, Leahy, Thurman, & Wirsing, Citation1981; Senior, Phillips, Barnes, & David, Citation1999). On the other hand, a rounded face with large eyes, thin eyebrows, and low facial features – a babyface – connotes approachability (e.g. Berry & McArthur, Citation1985).

These evaluations are based on the resemblance of the facial morphology underlying dominance and affiliation with emotional cues to anger and smiling (Hess et al., Citation2009). More generally, it is assumed that a perceptual overlap between emotion expressions and certain facial features drives the attribution of behavioral intentions to some types of faces (Zebrowitz, Fellous, Mignault, & Andreoletti, Citation2003). Thus, the perception of trustworthiness in neutral faces has been found to be linked the resemblance of these faces to expressions of anger and happiness (Oosterhof & Todorov, Citation2009).

These behavioral dispositions are of central importance for our interactions with others as they allow us to judge vital social characteristics of an individual we may interact with. In hierarchical primate societies, for example, highly dominant individuals pose a certain threat insofar as they can claim territory or possessions (food, sexual partners, etc.) from lower status group members (Menzel, Citation1973, Citation1974). Hence, the presence of a perceived dominant other should lead to increased vigilance and a preparedness for withdrawal (Coussi-Korbel, Citation1994). In contrast, an affiliation motive is associated with nurturing, supportive behaviors and should lead to approach when the other is perceived to be high on this disposition. That appearance cues can have lasting effects on individuals was shown for example by Mueller and Mazur (Citation1996) who found the perceived dominance of West Point cadets, based on photos alone, to be a predictor of later military rank.

The present research focuses on perceived dominance versus submissiveness as a cue for perceived helpfulness. In particular, we consider both the dominance of the potential helper and the dominance of the help seeker. As regards the helper, low dominance is associated with perceptions of warmth, kindness and interpersonal receptivity (Keating & Doyle, Citation2002; Zebrowitz & Montepare, Citation1992). Yet, not only warmth but also competence is often perceived to be associated with dominance as people believe that high status individuals are more capable than people of low status (Oldmeadow & Fiske, Citation2007).

At the same time, the dominance of the help seekers themselves may also play a role. Thus, it is possible that participants will consider a submissive help seeker to be more likely to receive help, simply because they appear less able to help themselves. In this vein, baby faced adults have been found to receive more help in comparison with more mature looking persons (Keating et al., Citation2003). Yet, by definition, dominant persons are expected to have more influence over others and hence when the help seeker is dominant one may expect that the person who is asked for help may feel obliged to do so. Thus, we did not make explicit predictions for the effect of the dominance of the help seeker.

2. The present research

The present research approached the question of the impact of perceived dominance on helping behavior from two angles. As regards the potential helper, we predicted that submissive helpers might be solicited more readily because they appear caring and likely to help. A contrasting hypothesis was that dominant helpers would be solicited because they appear competent.

As regards the help seeker we predicted that dominant help seekers might be more likely to receive help, because, by definition, dominant individuals have the ability to compel others. Thus, we predicted that dominant help seekers receive help because the helper feels obliged to help.

We tested these predictions in three studies, each within a different help context. Specifically, we presented participants with short vignettes that described a situation in which one person requires the help of another person. Help was required either to put together a set of furniture (Study 1a), to find information (Study 1b) or to obtain a loan (Study 1c). These contexts were chosen because they vary the potential time investment of the helper and whether help was sought in the interpersonal or the financial domain. Study 2 extended this research by asking if and to what extent the facial dominance of prospective helpers affects participants’ choices of a helper for themselves. As studies 1a to 1c used the same methodological approach and variables, these studies will be described together.

3. Studies 1a-c

3.1. Method

3.1.1. Participants

All participants were recruited through Prolific Academic. For Study 1a, 275 participants (119 men) with a mean age of M = 39 (SD = 13) years, for Study 1b, 272 participants (123 men) with a mean age of M = 35 (SD = 11) years, and for Study 1c, 273 participants (122 men, 2 gender unknown) with a mean age of M = 37 (SD = 12) years completed the experiment and passed control questions probing for attention. The majority of the participants were white, native speakers of English with some level of university education (see in the supplementary materials for details).

3.1.2. Stimulus material

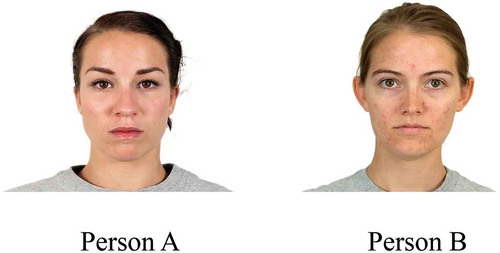

Photos of six men and six women showing neutral facial expressions were taken from the Chicago face data base (Ma, Correll, & Wittenbrink, Citation2015). The Chicago face data base provides information on the facial dominance of the actors. According to Ma et al. (Citation2015) this information is based on a norming sample of at least 1087 participants. Participants always saw two individuals who were either high in facial dominance (M > 3.70 on a seven-point scale) or low in facial dominance (M < 2.00), see for an example. This resulted in a 2 (dominance of the help seeker: low vs. high) x 2 (dominance of the potential helper: low vs. high) between–subjects factorial design. The two individuals were labeled with the letter A and B. The positions of the prospective helper versus the help seeker were counterbalanced across participants.

Participants were told that B is the individual asking for help and A is the individual being asked. The two individuals shown were always of the same gender.

3.1.3. Context

Participants read a vignette, which described the specific help situation. In all cases, the potential helper was described as an acquaintance of the help seeker, whom the latter is considering to ask for a help.

In Study 1a, the help seeker purchased a new piece of self-assembling furniture and needed someone to help with the assembly since it is rather complicated and one person alone cannot do it. This context was selected because it represents a situation where the potential helper invests a considerable amount of time in the help and, ideally also should have skills for this task.

For Study 1b, the vignette described a situation in which someone requires the services of a good structural engineer in time to complete a building project before the onset of winter. The person has an acquaintance who is knowledgeable in the domain and considers the option of asking this person for help in finding a suitable engineer rapidly. In this context, little time and energy are required to help.

In Study 1c, a different domain was chosen to generalize findings. Here, the vignette described a situation in which someone urgently needs $5000 to pay medical bills for his/her daughter and considers asking an acquaintance for a loan.

3.1.4. Procedure and dependent variables

After participants agreed to participate in the study, they saw a screen with instructions, followed by the vignette and the two faces, which were shown at the same time. They then saw a series of screens asking for (a) the likelihood that the help seeker would ask the potential helper for help as well as the likelihood that the potential helper would agree to help.

We then (b) asked for the presumed motives of the potential helper. Specifically, participants rated to what degree they think that the helper would help because s/he is (a) a caring and helpful person, (b) feels obliged to help, (c) is the sort of person who takes on the problems of others, (d) has the skills to help. For Studies 1b and 1c, no skill question was asked,Footnote1 as it was not clear what type of skill could underlie this behavior.

Finally, a last screen asked, as a manipulation check, for the perceived dominance of both helper and help seeker. The results (see Table 2 in the supplementary materials) showed that the faces were perceived as intended).

All ratings were made on 7- point scales anchored with 1 – not at all and 7 – very high.

4. Results

4.1. Initial analyses

Initial analyses showed that caring and taking on problems were highly correlated (Study 1a: r = .74, Study 1b: r = .61, Study 1c: r = .64, for all correlations, see Table 3 in the supplementary materials). We therefore combined these two into a new caring variable by averaging them.

However, unexpectedly the skills item in Study 1a was also strongly correlated with both caring (r = .49) and taking on problems (r = .44). Combining this variable with caring and taking on problems would have resulted in an adequate alpha (.79), but is theoretically problematic, as this item was intended to be orthogonal to caring. We therefore decided to drop this variable from the analysis and to consequently drop the hypothesis related to competence. By contrast, feeling obliged was not correlated substantially with caring across all studies. Thus, participants did not generally rate all motives similarly, i.e. there was no evidence of a halo effect. Rather, it seemed that in the context of helping participants did not consider skills separate from indicators of willingness to use these skills.

4.2. Descriptive analyses

A series of 2 (dominance of the helper) x 2 (dominance of the help seeker) analyses of variance were conducted on the dependent variables for each study. The results are shown in .

Table 1. Main effects of helpers’ and help seekers’ dominance on the dependent variables.

For Study 1a, the ANOVAs suggest that facial dominance affects both the perceived likelihood that someone will help and that they would be asked for help. The motive that emerged significantly was caring, which was associated with the facial dominance of the potential helper. Contrary to expectations, the facial dominance of the person asking for help did not affect the degree to which the person asked would feel obliged to help. The results from Studies 1b and 1c replicated these findings for the likelihood that the other person would help if asked and the motives for such help. Interestingly, in Study 1c, the facial dominance of the help seeker was found to have an effect on the likelihood would be helped. Specifically, a dominant help seeker was expected to be more likely to be helped.

However, the main effect of facial dominance of the potential helper on the likelihood that the person would be asked was only significant in Study 1a. Yet, this does not mean that the predicted indirect effect is also not significant (Hayes, Citation2017).

4.3. Hypothesis testing

We used a serial mediation model (see –) using PROCESS model 6 (Hayes, Citation2017) to test two hypotheses: first, the helper hypothesis stating that the facial dominance of the potential helper predicts that this person is considered to be caring and in turn to be willing to help, which then predicts the perceived likelihood that the person is asked for help. And second, the help seeker hypothesis stating that when asked by a dominant help seeker, potential helpers feel obliged to help and hence are perceived as willing to help, which in turn should predict the likelihood that they will be asked.

Figure 2. Serial mediation model predicting being asked for help from dominance of the helper (a) and help seeker (b) – Study 1a. Dominance was coded 0-submissive, 1-dominant.

Figure 3. Serial mediation model predicting being asked for help from dominance of the helper (a) and help seeker (b) – Study 1b. Dominance was coded 0-submissive, 1-dominant.

Figure 4. Serial mediation model predicting being asked for help from dominance of the helper (a) and help seeker (b) – Study 1c. Dominance was coded 0-submissive, 1-dominant.

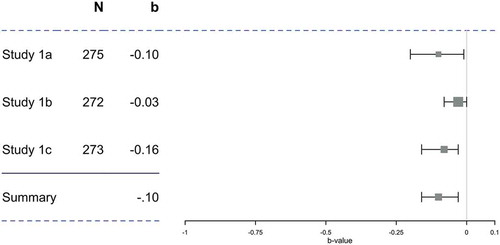

4.3.1. Helper hypothesis

A shown in , in Study 1a, the dominance of the potential helper was negatively associated with the perceived caring of the helper, which in turn was positively related to the perceived likelihood that the person would help if asked, which in turn predicted the likelihood that the person would be asked. The indirect effect across all variables was significant (b = -.10, CI95% = -.20, -.01) as was the direct effect from caring to the likelihood of asking. Thus, the first hypothesis, that submissive helpers would be perceived as willing to help because of their perceived caring nature was supported.

These findings were closely replicated in Study 1b and 1c (see and ). The indirect effect across all variables was significant (Study 1b: b = -.03, CI95% = -.08, -.00, Study 1c: b = -.08, CI95% = -.16, -.03). shows a summary of these effects.

In addition, in Study 1c only, the direct effect from dominance of the helper to the likelihood to help and the direct effect from caring to being asked to help were both significant, as were the indirect effects from dominance through the likelihood to help to being asked (b = -.13, CI95% = -.28, -.01) and the indirect effect from dominance through caring to likelihood to help (b = -.08, CI95% = -.20, -.01).

4.3.2. Help seeker hypothesis

For Study 1a and 1b, as shown in and , the help seeker hypothesis was not supported. There was also no significant direct negative effect from dominance of the help-seeker to the likelihood of being helped. Thus, it is unlikely that participants thought that a submissive helper would receive more help simply for being submissive nor that a dominant helper would compel help.

Replicating the findings from Study 1a and 1b, in Study 1c the dominance of the help seeker also did not predict the perceived obligation of the potential helper to help. However, both the direct effect from dominance to the likelihood to help and the indirect effect from dominance through the likelihood to help to being asked for help (b = .18, CI95% = .04, .35) were significant (). These effects were positive, suggesting that a dominant help seeker would be more likely to receive help and consequently ask for help, yet this was not mediated trough the motive of feeling obliged.

In sum, the findings from Study 1c closely replicated the findings from Study 1a and 1b for the link between dominance of the helper and the likelihood to ask the potential helper for help. Interestingly, when it comes to money issues the dominance of the help seeker is perceived to have an effect on the likelihood that help will be given and indirectly on the perceived likelihood that help would be asked for, however, this increased likelihood was not mediated by the perception that the potential helper would feel obliged to help.

In sum, in line with the argument by Keating and Doyle (Citation2002), as well as Zebrowitz and Montepare (Citation1992), we consistently found, across different helping domains, that when a potential helper has more submissive features, this person will be perceived as more likely to help than a person with dominant features because participants attribute a more caring nature to a submissive person.

However, we found much less evidence for the notion that the dominance of the help seeker predicted the perception that the potential helper felt obliged to help. Only in Study 1c, which concerned a financial loan, was weak evidence to that effect obtained. Study 2 was designed to assess whether the preference for a submissive helper would be maintained in a context where participants themselves are asked to choose between two people.

5. Study 2

5.1. Participants

A total of 62 participants (31 men) with a mean age of M = 34 (SD = 12) years who were recruited through Prolific Academic, completed the experiment and passed control questions probing for attention.

5.2. Stimulus material

The same pictures as in Study 1 were used. However, the participants now saw a person high in dominance and a person low in dominance side by side (the side on which the dominant/submissive person was shown was counterbalanced across participants). A manipulation check confirmed that the faces were perceived as intended (see Table 2 in the supplementary materials).

The vignette described a situation in which someone needs help with their 4th generation mobile phone, which stopped working properly and as the guarantee has expired, they want to solicit help with this problem from an acquaintance. Both individuals are described as competent and helpful in this regard and participants were asked to imagine themselves in this situation and to indicate whom they would choose to ask for help.

5.3. Dependent variable

Choice was a binary variable (0-submissive, 1 dominant). The same questions regarding motives and the manipulation check as in Study 1a were asked, in the same order, for both individuals. We replaced the skill question with a question about perceived competence. Caring and taking on problems were again substantially correlated (rdominant = .65, rsubmissive = .75) and combined into one variable. Competence again correlated substantially with both variables (see Table 3 supplementary materials).

6. Results

6.1. Choice of helper

Only 35% (SD = .48, CI95 = .24, .48) of the participants chose the dominant helper. That is, the preference for a submissive helper extended to a situation where participants were asked about their own preference.

6.2. Presumed motivation of the helper

A series of t-tests was conducted to compare presumed motivations for dominant versus submissive potential helpers. Participants considered submissive helpers to be significantly more caring and helpful They further considered the submissive helper to be more likely to agree when asked (see lower part of ).

7. Discussion

In sum, the preference for a submissive helper was also found when the participants were asked to imagine needing help themselves. The submissive helper was not rated as any more competent than the dominant helper but as more caring and more likely to agree. In this case, the submissive helper was also seen as more obliged to help.

8. General discussion

The results of Studies 1a to 1c suggest that people hold the view that the likelihood of a person to ask another for help depends on the submissiveness of the prospective helpers as reflected by their appearance. This link was mediated via the association between facial dominance and perceptions of being a caring and helpful person and hence likely to respond positively to the request. Specifically, since a submissive person appears to be more caring and helpful, as suggested by Keating and Doyle (Citation2002) as well as Zebrowitz and Montepare (Citation1992), they are also perceived as more likely to help when asked to do so (Keating et al., Citation2003). Williams and Williams (Citation1983) suggested that help seekers may be reluctant to seek help from powerful others because asking for help signals weakness and puts one in an inferior position. We found that help seekers are perceived as preferring to ask a submissive person for help because these are perceived as more caring. In fact, one can speculate that seeking help from a caring person may be less costly in terms of putting the help seeker in an inferior situation or losing face. After all, caring people may be also perceived as less concerned with their own status relative to the person in need of help.

We had also considered the possibility that expectations that one is likely to agree to a request for help would be predicted by the dominance of the help seeker. Specifically, when the help seeker is dominant, the prospective helper may be perceived as being more obliged to help. Conversely, it could be that a submissive help seeker could be deemed to more deserving of help because they are less likely to help themselves. This, however, was not the case since the dominance of the help seeker had no effect on the perceived obligation of the helper to help in Study 1a and 1b. Nor was the direct effect from the dominance of the help seeker to the likelihood that help would be granted significant in Studies 1a and 1b. Only in Study1c, was high dominance of the help seeker related to expectations that the potential helper would help – however, this expectation was not mediated by the notion that the helper would feel obliged to help.

Interestingly, we also did not find a positive direct link from the facial dominance of the potential helper to either the likelihood to being asked for help nor the likelihood to respond to such a request. Such a positive link, suggesting that dominant individuals would be more likely to be asked for help or help, would be predicted by notions that dominance, through its link to status, is related to competence (Oldmeadow & Fiske, Citation2007). In fact, the only variable that clearly and consistently predicted the likelihood that a person would help and be asked for help was the perception that this person helps because s/he is caring and takes on the problems of others. This impression in turn was informed by the perceived submissiveness of the potential helper. Thus, the present findings clearly suggest that the perception of affiliative motives rather than skill related motives drive the search for a helping hand.

Overall, it is interesting that the dominance of the help seeker had very little effect on the process of help seeking. By definition, a dominant person is one who leads and compels followers. Generally, much of what happens in the social arena is determined by the power of the people involved (Russell, Citation1938), which is partially reflected by the facial dominance of the individual (Mueller & Mazur, Citation1996). People also are attuned to dominance cues and automatically take these into account when evaluating an interaction (Moors & De Houwer, Citation2005). Thus, it is surprising at first sight that participants did not consider the likelihood that the more dominant individual would compel a potential helper in Studies 1a and 1b. This was only the case in Study 1c, where the help seeker asked for money. At first glance one would think it more likely that an obligation to help lead to compliance with a request when it is very simple to do, as was the case in Study 1b. It is more likely that caring becomes relevant when indeed a substantial effort on the part of the helper is required as was the case in Study 1a. Giving a loan of $5000 seems also a substantial effort, yet, here dominance relations were considered. It is possible that the money domain by its nature primes power relationships and hence makes it more likely that the facial dominance of the help seeker predicts helping behavior. Such a priming effect could also explain why the motive to feel obliged was not significantly linked to either variable.

Study 2 showed that the preference for a submissive potential helper is also found when participants imagined needing help themselves. Specifically, participants attributed a more caring nature to a submissive person and assumed that the person would be more likely to agree.

The present study has a number of limitations. For one, we used a vignette methodology with limited information. In real life, issues are often more complex and hence the decision who someone will ask for help may depend on a number of factors other than the perceived helpfulness of a stranger. However, we also are often in contexts where we have to ask people for help of whom we know next to nothing and first impressions guide the decision whether to approach someone, or to avoid that individual (Szczurek, Monin, & Gross, Citation2012).

The use of still photos also limits the generalizability of our findings. However, it is interesting to note that the effect of impressions based on still images shown one month prior still impact on likeability ratings based on a real life interaction (Gunaydin et al., Citation2017).

Finally, as noted above, we were not able to obtain skill or competence ratings that did not correlate with caring. This may suggest that in the minds of the perceiver the usefulness of skills is dependent on the affiliative nature of the skillful person. This is also surprising as the stereotype content model (Cuddy et al., Citation2009; Fiske, Cuddy, & Glick, Citation2007) places warmth and competence on orthogonal scales. Yet, as caring did not correlate highly with feeling obliged to help, participants did not generally rate all motives similarly, i.e. there is no evidence of a halo effect. Rather, it seems that in the context of helping, participants do not consider skills separate from indicators of willingness to use these skills. This may be an interesting avenue for future study.

In sum, the present research provided consistent evidence across four studies that the impression that another person is caring drives potential help seeking behaviors. This impression in turn is linked to the submissiveness of the potential helper. Notably, it is not the case that a submissive potential helper it perceived as obliged to help, but rather it is the presumed character trait of submissive people, the notion that they are caring, that drives the effect. Thus, even though we manipulated facial dominance, participants based their judgment on the inferred affiliation of the individual. This suggests that helping is a domain more strongly linked to affiliation motives than to power. Reciprocity and mutual exchange are part of what binds social groups (Gouldner, Citation1960) and helping each other is an integral part of this process. It is often assumed that humans as hierarchical primates structure their social bonds along dominance lines (Mueller & Mazur, Citation1997). Yet, the role of affiliation should not be underestimated.

In the specific context of helping, facial appearance cues to dominance and submission, which people process automatically when perceiving others (Moors & De Houwer, Citation2005) are an important determinant to whom one should address a request for help. One of the advantages of social life is the ability to rely on others in order to achieve desired goals. The faces of our conspecifics help us to do this.

Tables_Sup_R1.docx

Download MS Word (22 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here

Notes

1. In Study 1b, a question about knowledge of structural engineers was asked but not further analyzed.

References

- Bar, M., Neta, M., & Linz, H. (2006). Very first impressions. Emotion, 6, 269–278.

- Berry, D. S., & McArthur, L. Z. (1985). Some components and consequences of a babyface. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 48, 312–323.

- Coussi-Korbel, S. (1994). Learning to outwit a competitor in mangabeys (cercocebus torquatus torquatus). Journal of Comparative Psychology, 108, 164–171.

- Cuddy, A., Fiske, S., Kwan, V., Glick, P., Demoulin, S., Leyens, J., & Sleebos, E. (2009). Stereotype content model across cultures: Towards universal similarities and some differences. The British Journal of Social Psychology, 48(1), 1–33.

- Fiske, S., Cuddy, A., & Glick, P. (2007). Universal dimensions of social cognition: Warmth and competence. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 11, 77–83.

- Fletcher-Watson, S., Findlay, J. M., Leekam, S. R., & Benson, V. (2008). Rapid detection of person information in a naturalistic scene. Perception, 37(4), 571–583.

- Gouldner, A. W. (1960). The norm of reciprocity: A preliminary statement. American Sociological Review, 161–178. doi:10.2307/2092623

- Gunaydin, G., Selcuk, E., & Zayas, V. (2017). Impressions based on a portrait predict, 1-month later, impressions following a live interaction. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 8(1), 36–44.

- Hareli, S., & Hess, U. (2010). What emotional reactions can tell us about the nature of others: An appraisal perspective on person perception. Cognition and Emotion, 24, 128–140.

- Hayes, A. F. (2017). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Guilford Publications.

- Hess, U., Adams, R. B., Jr., & Kleck, R. E. (2009). The face is not an empty canvas: How facial expressions interact with facial appearance. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society London B, 364, 3497–3504.

- Keating, C. F., & Doyle, J. (2002). The faces of desirable mates and dates contain mixed social status cues. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 38(4), 414–424.

- Keating, C. F., Mazur, A., & Segall, M. H. (1981). A cross-cultural exploration of physiognomic traits of dominance and happiness. Ethology and Sociobiology, 2, 41–48.

- Keating, C. F., Mazur, A., Segall, M. H., Cysneiros, P. G., Divale, W. T., Kilbridge, J. E., ... Wirsing, R. (1981). Culture and the perception of social dominance from facial expression. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 40, 615–625.

- Keating, C. F., Randall, D. W., Kendrick, T., & Gutshall, K. A. (2003). Do babyfaced adults receive more help? The (Cross-cultural) case of the lost resume. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior, 27(2), 89–109.

- Ma, D. S., Correll, J., & Wittenbrink, B. (2015). The Chicago face database: A free stimulus set of faces and norming data. Behavior Research Methods, 47, 1122–1135.

- Menzel, E. W., Jr. (1973). Leadership and communication in young chimpanzees. In J. E. W. Menzel (Ed.), Precultural primate behavior, 192–225. Basel, Switzerland: Karger.

- Menzel, E. W., Jr. (1974). A group of young chimpanzees in a one-acre field. In A. M. Schrier & F. Stollnitz (Eds.), Behavior of nonhuman primates, 83–153. San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

- Moors, A., & De Houwer, J. (2005). Automatic processing of dominance and submissiveness. Experimental Psychology (Formerly” Zeitschrift Für Experimentelle Psychologie”), 52(4), 296–302.

- Mueller, U., & Mazur, A. (1996). Facial dominance of West Point cadets as a predictor of later military rank. Social Forces, 74, 823–850.

- Mueller, U., & Mazur, A. (1997). Facial dominance in Homo sapiens as honest signaling of male quality. Behavioral Ecology, 8, 569–579.

- Oldmeadow, J., & Fiske, S. T. (2007). System-justifying ideologies moderate status = competencestereotypes: Roles for belief in a just world and socialdominance orientation. European Journal of Social Psychology, 37, 1135–1148.

- Oosterhof, N., & Todorov, A. (2009). Shared perceptual basis of emotional expressions and trustworthiness impressions from faces. Emotion, 9, 128–133.

- Rule, N. O., Ambady, N., & Hallett, K. C. (2009). Female sexual orientation is perceived accurately, rapidly, and automatically from the face and its features. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 45, 1245–1251.

- Russell, B. (1938). Power: A new social analysis. London: Allen and Unwin.

- Senior, C., Phillips, M. L., Barnes, J., & David, A. S. (1999). An investigation into the perception of dominance from schematic faces: A study using the World-Wide Web. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments and Computers, 31, 341–346.

- Szczurek, L., Monin, B., & Gross, J. J. (2012). The Stranger effect: The rejection of affective deviants. Psychological Science, 23(10), 1105–1111.

- Todorov, A. (2008). Evaluating faces on trustworthiness: An extension of systems for recognition of emotions signaling approach/avoidance behaviors. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1124, 208–224.

- Todorov, A., Dotsch, R., Porter, J. M., Oosterhof, N. N., & Falvello, V. B. (2013). Validation of data-driven computational models of social perception of faces. Emotion, 13(4), 724–738.

- Williams, K. B., & Williams, K. D. (1983). Social inhibition and asking for help: The effects of number, strength, and immediacy of potential help givers. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 44(1), 67–77.

- Willis, J., & Todorov, A. (2006). First impressions: Making up your mind after a 100-ms exposure to a face. Psychological Science, 17(7), 592–598.

- Wilson, D. W. (1978). Helping behavior and physical attractiveness. The Journal of Social Psychology, 104(2), 313–314.

- Zebrowitz, L. A. (1996). Physical appearance as a basis for stereotyping. In M. H. N. McRae & C. Stangor (Eds.), Foundation of stereotypes and stereotyping (pp. 79–120). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- Zebrowitz, L. A. (1997). Reading faces: Window to the soul? Boulder, CO, US: Westview Press.

- Zebrowitz, L. A. (2004). The origin of first impressions. Journal of Cultural and Evolutionary Psychology, 2, 93–108.

- Zebrowitz, L. A., Fellous, J., Mignault, A., & Andreoletti, C. (2003). Trait impressions as overgeneralized responses to adaptively significant facial qualities: Evidence from connectionist modeling. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 7, 194–215.

- Zebrowitz, L. A., & Montepare, J. M. (1992). Impressions of babyfaced individuals across the life span. Developmental Psychology, 28, 1143–1152.