ABSTRACT

Two studies were conducted to investigate the factors determining consumers’ purchase intentions toward dried fruit in Taiwan. In the first study, we identified the most appropriate scale structure by using exploratory factor analysis on data from 306 participants. In the second study, the factor structures were verified by performing a confirmatory factor analysis of a sample comprising 575 participants. Structural equation modeling was then applied to test the hypothesized relationships, followed by a correspondence analysis to associate the eating experience of dried fruits with all participant sociodemographics. The results revealed that first, the high purchase intention toward dried fruits is positively influenced by autonomy motivation, relatedness motivation, and perceived convenience value, whereas it is negatively influenced by competence motivation and perceived health value. Second, the eating attitude mediates the effects of autonomy and competence motivation as well as perceived emotional and health values on the purchase intention. Third, marked differences are present in the choice and eating habit of dried fruits in the analysis of socioeconomic variables. Overall, the study results imply that dried fruit purchasing is a hedonistic-oriented behavior, and that consumers are confused regarding the products that are considered dried fruits; hence, a clear definition of dried fruits and effective consumer education are necessary. Furthermore, dried fruit manufacturers must improve the utilitarian values of health and convenience.

Introduction

Understanding consumer perceptions, motivations, attitudes, and purchasing behavior regarding a particular food is crucial, especially for the functional food industry (Nystrand and Olsen, Citation2020). Recent studies have highlighted that product attributes; consumer knowledge about nutrition and health; cognitive and affective precursors such as beliefs, attitudes, and motivations; and sociodemographic variables are critical determinants based on which consumers decide their food choice, and these factors also determine purchasing behavior (Mogendi et al., Citation2016; Nystrand and Olsen, Citation2020). Although the reasons for consuming healthy food products are mixed and even contradictory (Nystrand and Olsen, Citation2020), food acceptance is closely related to consumer motivation, with a belief in its overall health benefits or perceived rewards of consumption (Siegrist et al., Citation2015).

Motivation is an essential source of social and self-regulation, making individuals persistent and active in the enactment of their behaviors (Deci and Ryan, Citation2002). Self-determination theory (SDT) is a general theory of human motivation proposed by Deci and Ryan (Citation2002); it identified the three universal psychological of needs competence, autonomy, and relatedness. Healthy eating motivation is associated with healthy lifestyles, and it can predict the actual adoption of healthy behaviors in the long term (Smit et al., Citation2018). Currently, an increased intake of fresh fruits and vegetables and a lower intake of foods high in fat and sugar are an obvious market trend (Naughton et al., Citation2015). Specifically, the concept of psychological needs can be used to examine the motivation–behavior association by using comprehensive measures of food consumption (Verstuyf et al., Citation2012). SDT provides a framework to understand the health-related eating behaviors involved in eating regulation.

Products may provide benefits by offering functional, emotional, and social values (Sweeney and Soutar, Citation2001). Functional value involves product quality and perceived short-term and long-term costs; emotional value denotes affective feelings generated by a product; and social value represents the ability of the product to enhance consumer social self-concept (Ruiz-Molina and Gil-Saura, Citation2008; Sweeney and Soutar, Citation2001). Awareness of the eating behavior required for a healthy lifestyle has increased among the public (Savurdan and Aktas, Citation2011). When consumers choose a snack, they may pay more attention to the nutrition information and value of that product. Recent studies focusing on functional properties of dried fruits have indicated that these products can not only be an excellent alternative to chocolates (Magalhães et al., Citation2017) but also increase the consumption of healthy products. Thus, dried fruits should be given greater promotion as a part of the diet, and there is a general agreement on this (Sadler et al., Citation2019).

Modern drying technology allows manufacturers to produce dried fruits with high concentrations of bioactive compounds (Ullah et al., Citation2018). Research has found that functional properties such as sweetness and high fiber levels render dried fruits suitable to be incorporated into cereal bars or chocolates, which is different from the situation of fresh fruits (Magalhães et al., Citation2017). This trend indicates that foods can serve more roles than merely providing energy; certain foods can also be consumed to ensure healthy lifestyles and eating habits (Savurdan and Aktas, Citation2011). Although dried fruit intake is still low compared with overall fresh fruit intake, European consumers purchase dried fruits at least once a month (Jesionkowska et al., Citation2009). Some consumers use dried fruits as an energy snack, whereas others use them as a convenient product for baking or as healthy and functional products to be added to breakfast cereals (Jesionkowska et al., Citation2009). Dried fruits as a functional, convenient, healthy, and luxurious snack are categorized as niche products in Europe (Alphonce et al., Citation2015). However, consumers misunderstand what “dried fruits” are, and the marketing of dried fruits as a healthy snack is relatively new (Sadler et al., Citation2019). Thus, further investigation should be conducted on whether health reasons (as opposed to mere enjoyment) prompt consumers to consume dried fruits.

Although dried fruits are widely available in the Taiwanese market (Lee et al., Citation2016; TAITRA, Citation2020), to date, it is unclear how consumers interpret these products, what factors motivate them to purchase these products, and why they purchase these products and the underlying the cultural context. This study developed a comprehensive theoretical framework (based on the modified SDT) on the determinants of dried-fruit purchase intention. The research questions are as follows: (1) How do eating motivation, perceived value, and eating attitude affect the purchase intention toward dried fruits? (2) How much does eating attitude mediate the effects of eating motivation and perceived value on purchase intention? To answer these questions, a survey scale was developed and verified through both exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses with two independent samples. Structural equation modeling was used to test the research hypotheses, and correspondence analysis was used to analyze the association between sociodemographic variables and dry-fruit eating experience. The research outcomes are expected to provide insights into effective nutrition education and operative marketing strategies to position dried fruits in food marketing and guide consumers’ healthy choices.

Research Context

Current dried fruit studies have mainly focused on European markets (Alphonce et al., Citation2015; Cinar, Citation2018), and the results have indicated that European consumers are considerably familiar with dried fruit products, their processes, and drying technology, but they do not know much about tropical dried fruits (Cinar, Citation2018); however, European consumers prefer tropical fruits, such as mango, pineapple, and banana. They are willing to pay extra for tropical dried fruits produced in Africa (Alphonce et al., Citation2015). Till now, limited studies have focused on tropical and subtropical markets, especially Asia. Asia and South East Asia are the two major areas producing most common tropical fruits in world trade (Gepts, Citation2008). Between 2009 and 2014, the consumption of dried fruits in Asia-Pacific increased in terms of volume growth per capita (Kocheri and Shreyansh, Citation2015). This result revealed the trend of Asian consumers’ demand for healthy and convenient alternatives to fresh fruits and the increase in disposable income. It is appropriate to initially understand consumer perception and purchase intention for dried fruits in Taiwan (one of the most crucial economies in the Asia-Pacific region) and then conduct further in-depth investigation on the whole Asian market.

Tropical fruits reportedly contain healthy natural antioxidants (Pereira-Netto, Citation2018). The most popular tropical fruits worldwide are pineapple, mango, and papaya (Faostat, Citation2014), and these fruit species are common in Taiwan, the so-called Fruit Kingdom. As it is located in a subtropical climate zone and has hillside terrain and mountains, Taiwan is a region in which various tropical and subtropical fruits are cultivated, and the quality and sweetness of fruit and the competence of fruit breeding technology are all considered outstanding. However, climate change has significantly influenced the output and quality of fresh fruit and has increased the risk of fruit decay. Moreover, the perishability of fresh fruits, uncontrollable supply, and strict import regulations of each country affect the quality of fruits exported to overseas markets (Alphonce et al., Citation2015). Drying fresh fruit can increase its shelf life and ensure the reliability of supply, and drying technology can be easily adopted by small-scale individual owners and entrepreneurs. Recently in 2019, one important revised act contributed to the evolution of agricultural products in Taiwan; that is, the Agricultural Production and Certification Act (LTN, Citation2019). This lifted the restriction prohibiting farmers from setting up factories on farmland, encouraging them to produce processed products such as dried fruits and roasted beans through primary processing and thus promoting the added value of agricultural products. This may create business opportunities for Taiwan’s small-peasant economy and thereby increase household and national incomes.

Literature Review

Attitude and Consumption Behavior

Attitude refers to an individual’s evaluation of a given behavior as favorable or unfavorable and is formed based on individual belief about the outcomes of the behavior (Ajzen and Fishbein, Citation2005). Attitudes are learnt and affected by perceived information and experience. Attitudes are ambivalent when people have both positive and negative evaluations of behavioral outcomes (Sparks et al., Citation2001). Patch et al. (Citation2005) found that the attitude toward novel food enriched with omega-3 is the only significant predictor of the intention to consume the food. Numerous scholars have indicated that consumer attitude shows the strongest association with consumer intention, especially in terms of behavior toward functional food (Hung et al., Citation2016). Studies on the relationship between attitude and the intention of consuming organic food, fruit, and vegetables have consistently shown positive associations (Emanuel et al., Citation2012; Wang and Wang, Citation2015). Hung and colleagues (Citation2016) also demonstrated that attitude is the most vital determinant for the purchasing intention toward a new functional product. Thus, the first research hypothesis was proposed as follows:

H1. Consumer attitudes of eating dried fruits positively affect the purchase intention.

Motivation Based on Self-determination Theory

Motivation is considered the initial driving force of behavior (Huang and Hsu, Citation2009). SDT is one of the most influential theories of human motivation, and it explains that human behavior is motivated by a natural drive to satisfy basic and innate human needs, leading to growth, development, and well-being (Deci and Ryan, Citation2000). Human behavior is motivated by three main psychological needs: competence, autonomy, and relatedness (Deci and Ryan, Citation2000).

Competence motivation represents individuals’ belief in their ability to interact with the external environment (Deci and Ryan, Citation2002). Individuals self-regulate their motivations toward dietary restrictions, certain lifestyles and family structures, and particular social beliefs. They know what they are doing and what they are capable of in the pursuit of alternative foods. Autonomy motivation refers to the free will to choose and to be the origin of one’s own behavior (Edmunds et al., Citation2007), and it also outlines that one’s behavior emanates from an internal perceived locus of causality (Wilson et al., Citation2003). Relatedness motivation represents a feeling of being connected to others and belonging to a particular group (Baumeister and Leary, Citation1995). Husby et al. (Citation2009) suggested that sharing foods with others as a social activity contributes to a sense of belonging to a group, especially for women.

Motivation is reflected in cognitive attitude (perceived benefit), but it is distinct from cognitive attitude because attitude is indicative of autonomous motivation based on SDT (Paisley and Sparks, Citation1998). Research has identified that individual motivation has a significant predictive effect on attitude (Ham et al., Citation2018). Motivation with multidimensional aspects may have different effects on attitude (Al-Jubari, Citation2019; Fayolle et al., Citation2014). These conclusions indicate that motivation exerts diverse effects on attitude and behavior. Because motivation is considered the initial driving force of behavior, it is likely that individual eating motivation affects the attitude toward dried fruit consumption. Therefore, we posited the second set of hypotheses:

H2a: Competence motivation of eating dried fruits positively affects the eating attitude.

H2b: Autonomy motivation of eating dried fruits positively affects the eating attitude.

H2c: Relatedness motivation of eating dried fruits positively affects the eating attitude.

SDT states that individuals tend to engage in a behavior for their own sake, interest, or pleasure (Deci and Ryan, Citation2000) and as an essential determinant of behavioral change (Smit et al., Citation2018). SDT has been used to explain human behavior in various domains, especially in terms of changing diets to include more sustainable food choices (Schösler et al., Citation2014). Intrinsic motivation based on SDT to adopt healthier lifestyle patterns, such as healthy eating, fruit and vegetable consumption, and exercising, has been found to directly predict the actual adoption of these behaviors in the long term (Teixeira et al., Citation2015). Payne et al. (Citation2004) also indicated that individual intrinsic motivation related to cognitive processing for decision-making could culminate in intention formation. Smit et al. (Citation2018) identified that young adolescents’ intrinsic motivation is a stronger predictor of their intention for the consumption of fruit, vegetables, and water. Therefore, we posited the third set of hypotheses:

H3a. Competence motivation of eating dried fruits directly and positively affects the purchase intention.

H3b. Autonomy motivation of eating dried fruits directly and positively affects the purchase intention.

H3c. Relatedness motivation of eating dried fruits directly and positively affects the purchase intention.

Perceived Value of Products

Perceived value reflects ‘the consumer’s overall assessment of the utility of a product based on perceptions of what is received and what is given’ (Zeithaml, Citation1988: 14). The experience of perceived value relies on the individual, situation, or product (Holbrook, Citation2005) in the purchase context. Because it is a subjective and ambiguous concept (Woodruff, Citation1997), scholars have found it difficult to compare the results of different empirical studies on perceived value; thus, inconsistency exists in the measurement of perceived value (Ruiz-Molina and Gil-Saura, Citation2008). The fundamental dimensions of perceived value are emotional, social, and functional values (Sweeney and Soutar, Citation2001). Recent research on fruit product consumption has confirmed that consumers’ perception of product attributes, such as sensory appeal, freshness, nutrition, cost, serving size, convenience, where the food come from, and how the food is produced, are their main considerations (Asioli et al., Citation2016; Harker et al., Citation2009). In addition, Sijtsema et al. (Citation2012) identified three dimensions of consumers’ perception of dried and fresh fruits: perceived health, perceived convenience, and perceived price. Focus group research has further indicated that the healthiness of dried fruits is perceived in nutrition, naturalness, taste, and well-being (Sulistyawati et al., Citation2019).

Studies have consistently shown that consumers’ perceived value has a significant influence on their behavioral intentions (McDougall and Levesque, Citation2000; Ryu et al., Citation2012), either directly or indirectly. First, purchasing food products can be positively affected by health benefit and nutrition information (Silvestri et al., Citation2018). Globally, there is increasing emphasis on the health benefits of fruit products as their most perceived value (Cinar, Citation2018; Jesionkowska et al., Citation2009; Sijtsema et al., Citation2012). Second, perceived emotional value is mainly derived from consumers’ perception of the product (Migliore et al., Citation2015), partially determining consumer food choice and consumption (Macht, Citation2008). Third, perceived convenience value including price, convenience, and availability also affects consumer food selection (Sabbe et al., Citation2009). The more positively consumers rate the health and convenience aspects of fruit products, the more they are willing to forego their health (Sijtsema et al., Citation2012). Accordingly, the fourth set of hypotheses were proposed:

H4a. The perceived health value of eating dried fruits directly and positively affects the purchase intention.

H4b. The perceived emotional value of eating dried fruits directly and positively affects the purchase intention.

H4c. The perceived convenience value of eating dried fruits directly and positively affects the purchase intention.

Diverse factors determine people’s dietary attitudes, such as sensory preferences, beliefs about the nutritional quality, and health perception of food (Naughton et al., Citation2015). Studies have confirmed that perceived value affects customer attitude (Ruiz-Molina and Gil-Saura, Citation2008). In Western societies, consumers’ general attitude toward healthy eating is positive (Hearty et al., Citation2007), which is mainly attributed to the reasonably high level of nutritional and health knowledge (Aikman et al., Citation2006). Positive attitudes have been found to be related to consumer perceptions of the health benefits of dried fruits; thus, favorable attitudes toward fruits may arise from the perceived health benefits and good taste. The fifth set of hypotheses were thus proposed:

H5a: The perceived health value of eating dried fruits positively affects the eating attitude.

H5b: The perceived emotional value of eating dried fruits positively affects the eating attitude.

H5c: The perceived convenience value of eating dried fruits positively affects the eating attitude.

Research Methods for Study 1

Methods

Participants

Those who had both experience with eating dried fruits and basic knowledge of Taiwanese dried-fruit products were target respondents. To identify eligible respondents, all respondents were first asked whether they ate dried fruits recently. In addition, we provided information on the definition, types, and characteristics of Taiwanese dried fruits at the beginning of the questionnaire. Study 1 included a total of 306 Taiwanese participants as the calibration sample to test the number of factors in each scale through an exploratory factor analysis (EFA). Almost two-thirds of participants were women and were aged less than 20 years (22.88%), 21–30 years (30.72%), 31–40 years (15.69%), 41–50 years (18.62%), and 51 years or older (13.09%); 76.47% had no children; 50% were students; and 44.77% preferred to eat dried fruits at home (). Participation was voluntary, confidential, and anonymous.

Table 1. Analysis of sociodemographics (n = 306)

Measures

To achieve the study purpose, in addition to an extensive literature review for identifying measurement items, focus group interviews with experts were conducted to generate useful information for instrument development. As dried fruits are considered to be between fruit processed products and snacks, no existing scales are available that can be directly adapted. Expert advice was used when developing the survey instrument. Eating motivation was measured using a 14-item scale based on three dimensions of SDT (Deci and Ryan, Citation2000). A 14-item scale for measuring perceived value was developed based on the scales of Sweeney and Soutar (Citation2001) and Ruiz-Molina and Gil-Saura (Citation2008) as well as based on quantitative and qualitative studies on consumer perception of dried fruits (Cinar, Citation2018; Sijtsema et al., Citation2012). Finally, measures for eating attitude and purchase intention were slightly modified based on a 3-item scale derived from Jun and Arendt (Citation2016). The items were evaluated using a 6-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree).

Procedures

An online questionnaire was developed using SurveyCake, a Taiwanese survey platform; the questionnaire represented a convenient and immediate means for participants to provide responses. The survey web address was sent by e-mail and posted on Facebook between October and November 2019.

Results

EFA is a well-established technique for exploring the factor structure of a specific variable, with n = 50 as a reasonable absolute minimum (de Winter et al., Citation2009). The conventional cutoff loading is.3 for EFA. The data were analyzed using R, and an item analysis was performed using the psych package (Revelle, Citation2012). A factor loading more than .3 was the cutoff point. EFA was conducted using principal analysis. The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin test, which measures sampling adequacy, was performed for analyzing the motivation (0.86), perceived value (0.86), attitude (0.66), and intention (0.74) items. In addition, Bartlett’s test of sphericity was performed, and the results were statistically significant for the motivation (χ2 = 40, df = 10, p < .005) and perceived value (χ2 = 70, df = 10, p < .005) items. Therefore, the sample data were considered appropriate for factor analysis. Principal axis factoring (PAF) analyses with promax rotation were conducted to determine the dimensionality of these four variables.

Based on the established criteria (Tabachnick and Fidell, Citation2001), three-factor solutions (eigenvalues more than 1) explaining 48.00% of variance were considered the optimal factor structure for individual motivation. Factor 1 was autonomy motivation; factor 2 was competence motivation; and factor 3 was relatedness motivation. The correlation coefficients among the three factors were .38, .47, and .51, and the Cronbach’s α values of factors 1, 2, and 3 were .834, .803, and .928, respectively.

In addition, three-factor solutions (eigenvalues greater than 1) explaining 60.00% of variance were considered the optimal factor structure for perceived value. Factor 1 (health value) included items related to nutrition and health benefits; factor 2 (emotional value) included items related to the feelings experienced when eating dried fruits; and factor 3 (convenience value) included items related to their utility. The correlation coefficients among the factors were .26, .43, and .45, and the Cronbach’s α values of factors 1, 2, and 3 were .908, .798, and .778, respectively.

Furthermore, the Cronbach’s α values of eating attitude and purchase intention were .763 and .928, and the one-factor solution explained 44.00% and 64.00% of variance, respectively. The high level of internal consistency indicates the appropriate reliability of the developed scales. presents the results of the analysis of four variables obtained in Study 1.

Table 2. PAF, mean, and standard deviation of the scale (n = 306)

Research Methods for Study 2

Methods

A total of 575 participants were recruited for Study 2 in Taiwan as the validation sample. This sample was used to confirm the established factor structures by performing a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). This sample also served as the modeling sample to test the study hypotheses through structural equation modeling (SEM), followed by correspondence analysis (CA) to examine whether different consumer segments exist for dried fruits. Most participants were women (67%); 48.3% were college students; the age groups were less than 20 years (22.78%), 21–30 years (30.78%), 31–40 years (15.65%), 41–50 years (18.61%), and 51 years or older (12.17%); and 73.91% had no children (). Participation was voluntary, confidential, and anonymous. The measures and research procedures were the same as those in Study 1, except for the survey schedule (from November to December 2019).

Table 3. Analysis of sociodemographics (n = 575)

CFA Results

Sample sizes >200 are regarded as acceptable for CFA (Boomsma, Citation1982). The conventional cutoff loading is .5 for CFA. In this study, CFA with maximal likelihood estimation was performed using the R lavaan package (version 8.80) to test the validity of the factor structures. The indicators recommended by Chen and Liu (Citation2008), Hu and Bentler (Citation1999), Kline (Citation2011), and Norberg et al. (Citation2007) were adopted to assess the goodness of fit of the model (RMSEA ≦ .10, SRMR ≦ .08, CFI ≧ .80, NFI ≧ .80, TLI ≧ .80). Regarding the motivation variable, the three-factor solution yielded an acceptable fit (χ2 = 348.96, df = 74, p < .005, RMSEA = .080, SRMR = .072, CFI = .87, NFI = .84, TLI = .84). shows the factor loadings and composite reliability results.

Table 4. CFAs of variables (n = 575)

In this study, construct validity was determined based on convergent validity and discriminant validity. The convergent validity of each factor was tested by assessing the standardized factor loadings (Hair et al., Citation2010). Discriminant validity was assessed by calculating the confidence intervals of interfactor correlation estimates, denoted as φ (Bagozzi and Phillips, Citation1982). The heterotrait–monotrait ratio of correlations (HTMT) was used to examine discriminant validity, because HTMT has recently been established as a superior criterion compared with conventional methods such as the Fornell–Larcker criterion (Henseler et al., Citation2015). The correlation between factors 1 and 2 was .643, factors 2 and 3 was .696, and factors 1 and 3 was .635, indicating that HTMT criterion values were below 1.0 (Henseler et al., Citation2015). The results confirmed that the convergent validity and discriminant validity of the factors.

Regarding the perceived value variable, the three-factor solution yielded an acceptable fit (χ2 = 388.762, df = 74, p < .005, RMSEA = .086, SRMR = .065, CFI = .88, NFI = .86, TLI = .86). shows the factor loadings and composite reliability results. Based on the criteria reported by Hair et al. (Citation2010), each factor achieved convergent validity. The correlation between factors 1 and 2 was .328, factors 2 and 3 was .494, and factors 1 and 3 was .411, respectively, indicating that HTMT criterion values were below 1.0; the results thereby confirmed discriminant validity (Henseler et al., Citation2015).

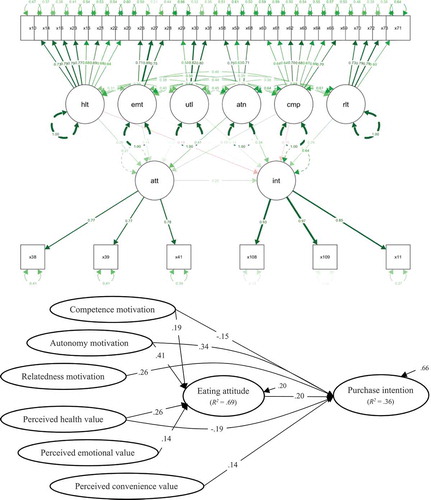

SEM Results

The proposed hypotheses were tested using the R lavaan package to perform SEM. We examined the mediating effects of the three factors by following the four steps suggested by MacKinnon, Lockwood, Hoffman, West, and Sheets (Citation2002). The final model fit was acceptable (χ2 = 1439.39, df = 499, p < .005, RMSEA = .056, SRMR = .066, CFI = .88, NFI = .823, NNFI = .861, TLI = .861), and the results accounted for substantial levels of variance for the variables of eating attitude (R2 = .692, residual = .201) and purchase intention (R2 = .358, residual = .656). Squared multiple correlation (R2) is a common indicator showing the integrated effect size for endogenous variables used to predict a particular phenomenon. According to the recommendations of Cohen (Citation1988), R2 values of .01, .09, and .25 denote small, medium, and large effects, respectively, in behavioral sciences. The results of the present study illustrated that the structural relations in the final model explained 31% of the total variance in eating attitude and 64% of the total variance in purchase intention.

Overall, as the structural model in indicates that the eating attitude positively affected the purchase intention; thus, H1 was supported. All three motivations (competence, autonomy, and relatedness) and two perceived values (health and convenience) had direct effects on the dried fruit purchase intention; autonomy, relatedness, and convenience had positive effects, whereas competence and health perception had negative effects; hence, H3b, H3 c, and H4 c were supported, but H3a and H4a were rejected. H4b was also rejected because perceived emotional value had no significant effect on the purchase intention. In addition, competence, autonomy, perceived health value, and perceived emotional value positively affected the eating attitude; thus, H2a, H2b, H5a, and H5b were supported, whereas relatedness motivation and perceived convenience value had no significant effects on the eating attitude; thus, H2 c and H5 c were rejected ().

Table 5. Summary for hypothesis testing

In terms of predictive validity, autonomy motivation had the highest direct and positive effects on both the eating attitude (.41) and purchase intention (.34) (). Relatedness motivation (.26) and perceived convenience value (.14) also had direct and positive effects on the purchase intention. This result indicates that if dried fruits meet the needs of autonomy, socialization, and utility, consumers develop a purchase intention without too much cognitive consideration. However, the results revealed that competence motivation and perceived health value directly and negatively affected consumers’ purchase intention with comparatively similar power (−.15; −.19). Thus, even if consumers perceive dried fruits as unhealthy and not in accordance with their beliefs or ability to interact with the external environment, they still have the intention to purchase dried fruits.

Table 6. Correlation coefficients and the effects of latent independent variables (n = 575)

The direct, indirect, and total effects in indicate that the eating attitude mediates the effects of competence motivation, autonomy motivation, perceived health value, and perceived emotional value on the purchase intention toward dried fruits.

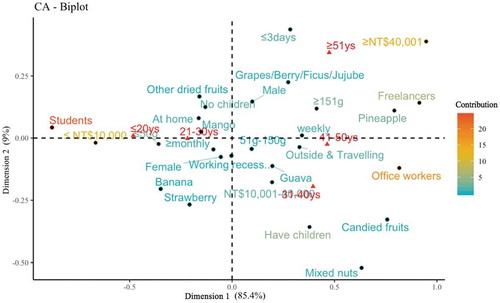

Correspondence Analysis Results

Correspondence analysis (CA) aims at investigating the structure of relationships between categorical variables and their categories; in this study, CA was applied to purchase behavior data (Grunert et al., Citation2016). CA was used in this study to determine the existence of different dried-fruit consumer segments. CA plots data in a two-dimensional space, portrays information sources’ positions in a connotative space, and evaluates the association between variables in a contingency table (Sun et al., Citation2020). This analysis was conducted using R with the CA package (Nenadic and Greenacre, Citation2007), and R packages such as FactoMineR, factoextra, and ggplot2 can facilitate the extraction and visualization of the output. describes a CA plot of dried fruit choices and their relationship with consumer sociodemographic variables.

Differences were identified in the choice of dried fruits. Students chose ≤ 50 g tropical dried fruits (mango, banana, and/or strawberry), with more snack-oriented function monthly, and they preferred to eat the fruits at home or when watching TV. The infrequency of eating dried fruits indicates that dried fruits may be one type of snacks consumed to fulfil their daily diverse needs. Middle-aged participants who were office workers and those with children preferred to eat mixed nuts and dried fruits during working or recess, with nutrition-oriented function. They also preferred to eat candied fruit, a Taiwanese soul food. Participants who were freelancers preferred to consume dried fruits with health benefits, such as dried grapes, ficus carica, and red jujube. They consumed larger amounts and with more frequency.

Discussion

The results revealed that the eating attitude affects the purchase intention of dried fruits, concurring with the results of previous studies (Emanuel et al., Citation2012; Hung et al., Citation2016). This indicated that consumers who recognize the value of eating dried fruits are interesting, fashionable, and wise and have a strong intent to buy the products. In addition, the results showed that the eating attitude plays a mediating role in the relationship between motivation and purchase intention, which is supported by prior research such as those by Ham et al. (Citation2018); Naughton et al. (Citation2015); and Fayolle et al. (Citation2014). This implies that vehicles to enhance the purchase intention of dried fruits must be considered to engage in the activity through the association between positive motivations and eating attitudes. Furthermore, we found that perceived values boost the purchase intention through attitudes, which is supported by several studies including those by Cinar (Citation2018); Hearty et al. (Citation2007); and Sijtsema et al. (Citation2012). This implies that the purchase behavior of eating dried fruits generally attributes to a high level of perceived values with eating attitudes. The effects of attitudes have crucial implications to dried fruit marketing; advertisers should associate motivations and perceived values to eating attitudes through storytelling and images.

The results revealed that the high purchase intention toward dried fruits is positively influenced by autonomy motivation, relatedness motivation, and perceived convenience value. This implies that dried fruits are considered as a snack among Taiwanese consumers. Research suggests that hedonic eating value (e.g. taste or enjoyment) may increase the consumption of snack foods, whereas utilitarian eating value (e.g. health or weight management) has the opposite effect on consumption (Nystrand and Olsen, Citation2020). This finding is consistent with the prior research finding that dried fruits can satisfy the consumer demand for bonding and socializing with families and friends (Grunert et al., Citation2016). This also supports that young adults may choose a combination of both healthy and unhealthy snacks as their general snacks (Savige et al., Citation2007); if they prefer the taste of unhealthy snacks, the existing more healthy alternatives may be less attractive (Grunert et al., Citation2016). This implies that advertising in the Taiwanese market for dried fruits should focus on the taste, the convenience of carrying and storing the products, and the enjoyment of sharing the products with friends and relatives; dried fruits should be treated as a local specialty to be gifted or as a snack in a festival or party.

The present study results demonstrated that perceived convenience values did not influence the eating attitude, and their effects were not strong as expected; this might be because a wide variety of fresh fruits is commonly available in Taiwan, which reduces the consumer need for dried fruits. When people intend to eat healthfully but realistically perceive that fresh fruits are not available in the immediate or limited environment (Naughton et al., Citation2015), dried fruits might be purchased. In other words, fresh fruit availability in the market plays an important role in influencing consumer purchase intentions toward dried fruits. This observation is consistent with the finding of previous studies that the lack of availability of certain food, the amount of effort, and certain place and time to acquisition limit consumer demand (Joshi and Rahman, Citation2015). These factors might influence the consumer need for these products; thus, consumers purchase other products instead.

Moreover, the results indicated that high purchase intention toward dried fruits is negatively influenced by perceived health value and competence motivation. Accordingly, individuals’ perceived health value and competence motivation are driven by rationality (Smit et al., Citation2018), implying that people associated with healthy lifestyles who rationally emphasize on health values and have perceived competence to distinguish healthy foods may not purchase dried fruits. This might be also because of cultural factors. A qualitative study of perceptions of dried fruits across cultures found that dryness (losing water) associated with ‘上火 shanghuo’ in traditional Chinese concepts might cause physical discomfort (Sulistyawati et al., Citation2019). Moreover, to meet the potential market need, many traditional candied fruit manufacturers have shifted to producing dried fruits, which utilize the same mixing process; this may mislead consumer perception. For example, some dried fruits are usually infused with sugar syrup or fruit juices prior to drying, although these fruits can be dried without any infusion (Sadler et al., Citation2019). These products are either classified as processed fruit products or preserved fruit and are sold in supermarkets and online shopping platforms; such classification further confuses consumers.

In this study, even though the results revealed that perceived emotional value positively affected the eating attitude, it had no overall effects on the purchase intention, and even the means of emotional value and eating attitude showed slight disagreement. Most of our survey participants were college students aged less than 25 years; the results revealed that dried fruits might be one type of diverse snack options, no single snack type dominates the youth’s choices, and the youth consumes new products with wide appeal; therefore, constructing a scale focused on one main product is challenging (Grunert et al., Citation2016). Furthermore, this study provides additional support to the market finding that watching TV and spending leisure time are the most frequent contexts for snacking (Savige et al., Citation2007). Research outcomes indicate that dried fruits are categorized as niche products in Europe (Alphonce et al., Citation2015), and this niche market also exists in Asia. However, given the general confusion and the lack of consensus on the definition of dried fruits, Taiwanese consumers may answer our questionnaire with either fresh fruit or candied fruit as the reference, which is consistent with the prior research finding that because individuals may not clarify their own misconceptions, they may not actively seek accurate nutrition information (Chery et al., Citation1987).

Conclusions and Contributions

The findings of this study indicate that first, availability plays a crucial role in influencing consumers to consume dried fruits, especially in certain eating situations, and the easy availability of fresh fruit in the Taiwanese market compared with that in the European market might be the reason for the low nutrition and health perceptions of dried fruits. Second, the high purchase intention toward dried fruits is positively influenced by autonomy motivation, relatedness motivation, and perceived convenience value and is negatively influenced by competence motivation and perceived health value, indicating that dried fruit purchasing is a hedonistic-oriented behavior rather than utilitarian-driven; consumers with strong motivation for healthy prefer eating dried fruits occasionally as a snack rather than changing their belief-driven long-term dietary routine. Third, dried fruits are regarded as a niche snack and as one type of diverse snack options among young consumers, but dried fruits do not dominate their snack preference. Fourth, the lack of a definite position and market segment for dried fruits cause consumers to have misconceptions and unclear nutrition information about these products.

In this study, self-determination theory was extended to include perceived value, and the results elucidate the influence of self-motivation, consumer perception, and eating attitude on dried-fruits purchase intention in the Taiwanese context. This study contributes to the food choice and eating behavior literatures in at least two respects. First, this study’s extension of self-determination theory extends our understanding of human needs, perceptions, and attitudes in psychological processes underlying dried fruit consumption. To the best of our knowledge, this extended model has not been used to investigate healthy eating behavior. Second, because needs, perceptions, and attitudes are part of cognition, ours is a dynamic theoretical framework that explains the premeditated psychological processes underlying eating attitude. Furthermore, we applied a novel concept and formulated a self-determination theory scale in the context of dried fruit consumption.

In summary, even if dried fruits have the same attributes as fresh fruits, fresh fruit consumption is higher in subtropical Taiwan, where the demand for processed fruits is limited, and the processing methods and quality control of the products may vary across different manufacturers, causing consumers to have misconceptions of their nutrition and health values. Successful food products should be both utilitarian and hedonic to satisfy consumer food needs and ensure loyalty to those product brands (Nystrand and Olsen, Citation2020; Steptoe et al., Citation1995; Verbeke, Citation2006). While lacking utilitarian value of dried fruit is generally existed among current Taiwanese perception. As a result, improving utilitarian value of dried fruit may achieve commercially succeed. This study revealed the need for designing more effective consumer education programmes or materials, including food labels, and promoting consumer knowledge on the functional properties of dried fruits for the domestic market to guide the healthy choices of consumers. The government and related public service sectors should clearly define the term ‘dried fruit’. For manufacturing and marketing operations, two aspects of dried fruits should be highlighted. One aspect is to satisfy consumer utilitarian needs for eating anytime and anywhere, and the other aspect is to fulfil the socializing and sharing needs. These measures would simultaneously balance consumer hedonic expectations and improved functional attributes, opening up new market segments.

Research Limitations and Closing Remarks

This study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, participants of both Study 1 and Study 2 were predominantly young people, a proportion similar to that of dried-fruit consumers in the general population (Pan et al., Citation2011). However, these samples might not be representative of the general Taiwanese population. Second, in combined Study 1 and Study 2, nearly 80% of participants reported their consumption frequency as more than 1 month. These participants may have consumed dried fruits occasionally; some might not even be familiar with dried fruits at all. To improve this limitation, comparisons between groups with unlike eating habits of dried fruits are necessary. Third, product familiarity can affect how consumers utilize product characteristics to form product quality judgment. When filling the questionnaire for this study, participants might set different reference objects based on their experience or familiarity with specific food products, which might cause contradictory responses. Future research may include fresh fruit, fruit products, or other snacks for reference or comparison to help participants clarify their doubts when answering questions.

References

- Aikman, S.N., K.E. Min, and D. Graham. 2006. Food attitudes, eating behaviour, and the information underlying food attitudes. Appetite 47(1):111–114. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2006.02.004.

- Ajzen, I., and M. Fishbein. 2005. The influence of attitudes on behaviour, p. 173–221. In: D. Albarracín, B.T. Johnson, and M.P. Zanna (eds.). The handbook of attitudes. Erlbaum, Mahwah, NJ.

- Al-Jubari, I. 2019. College students’ entrepreneurial intention: Testing an integrated model of SDT and TPB. Original Res. 9(2):1–15.

- Alphonce, R., A. Temu, and V.L. Almli. 2015. European consumer preference for African dried fruits. British Food J. 117(7):1886–1902. doi: 10.1108/BFJ-10-2014-0342.

- Asioli, D., M. Canavari, L. Malaguti, and C. Mignani. 2016. Fruit branding: Exploring factors affecting adoption of the new pear cultivar ‘Angelys’ in Italian large retail. Int. J. Fruit Sci. 16(3):284–300. doi: 10.1080/15538362.2015.1108894.

- Bagozzi, R.P., and L.W. Phillips. 1982. Representing and testing organizational theories: A holistic construal. Adm. Sci. Q. 27(3):459–489. doi: 10.2307/2392322.

- Baumeister, R.F., and M.R. Leary. 1995. The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychol.Bull. 117(3):497–529. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.497.

- Boomsma, A. 1982. The robustness of LISREL against small sample sizes in factor analysis models, p. 149–173. In: K.G. Jöreskog and H. Wold (eds.). Systems under indirect observation: Causality, structure, prediction (part 1). North-Holland, Amsterdam.

- Chen, S., and L. Liu. 2008. Measure of ERP users’ satisfaction. Proc. 2008 IEEE Int. Conf.Serv. Oper. Logist. Inf. 2:1980–1985.

- Chery, A., J.H. Sabry, and D.M. Woolcott. 1987. Nutrition knowledge and misconceptions of university students: 1971 vs. 1984. J. Nutr. Educ. 19(5):237–241. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3182(87)80051-1.

- Cinar, G. 2018. Consumer perspective regarding dried tropical fruits in Turkey. Italian J. Food Sci. 30(4):809–827.

- Cohen, J. 1988. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd ed. Lawrence Erlbaum, Hillsdale, NJ.

- de Winter, J.D., D. Dodou, and P.A. Wieringa. 2009. Exploratory factor analysis with small sample sizes. Multivariate Behav. Res. 44(2):147–181. doi: 10.1080/00273170902794206.

- Deci, E.L., and R.M. Ryan. 2002. Overview of self-determination theory: An organismic dialectical perspective, p. 3–33. In: E.L. Deci and R.M. Ryan (eds.). Handbook of self-determination research. Rochester University Press, Rochester, NY.

- Deci, E.L., and R.M. Ryan. 2000. The” what” and” why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behaviour. Psychol. Inq. 11(4):227–268. doi: 10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_01.

- Edmunds, J., N. Ntoumanis, and J.L. Duda. 2007. Adherence and well-being in overweight and obese patients referred to an exercise on prescription scheme: A self-determination theory perspective. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 8(5):722–740. doi: 10.1016/j.psychsport.2006.07.006.

- Emanuel, A.S., S.N. McCully, K.M. Gallagher, and J.A. Updegraff. 2012. Theory of planned behaviour explains gender difference in fruit and vegetable consumption. Appetite. 59:693–697. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2012.08.007.

- Faostat, F. 2014. Food and agriculture statistics: Trade. Food and Agricultural Organization, Rome. http://faostat.fao.org/site/342/default.aspx.

- Fayolle, A., F. Liñán, and J.A. Moriano. 2014. Beyond entrepreneurial intentions: Values and motivations in entrepreneurship. Int. Entrepreneurship Manage. J. 10(4):679–689. doi: 10.1007/s11365-014-0306-7.

- Gepts, P. 2008. Tropical environments, biodiversity, and the origin of crops, p. 1–20. In: P.H. Moore and R. Ming (eds.). Genomics of tropical crop plants. Springer, New York, NY.

- Grunert, K.G., S. Brock, K. Brunsø, T. Christiansen, M. Edelenbos, H. Kastberg, … K.K. Povlsen. 2016. Cool snacks: A cross-disciplinary approach to healthier snacks for adolescents. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 47:82–92. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2015.10.009.

- Hair, J.F., W.C. Black, B.J. Babin, and R.E. Anderson. 2010. Multivariate data analysis: A global perspective. Pearson/Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, NJ.

- Ham, M., A. Pap, and M. Stanic. 2018. What drives organic food purchasing? Evidence from croatia. British Food J. 120(4):734–748. doi: 10.1108/BFJ-02-2017-0090.

- Harker, F.R., B.T. Carr, M. Lenjo, E.A. MacRae, W.V. Wismer, K.B. Marsh, … F.A. Gunson. 2009. Consumer liking for kiwifruit flavour: A meta-analysis of five studies on fruit quality. Food Qual. Prefer. 20(1):30–41. doi: 10.1016/j.foodqual.2008.07.001.

- Hearty, A.P., S.N. McCarthy, J.M. Kearney, and M.J. Gibney. 2007. Relationship between attitudes towards healthy eating and dietary behaviour, lifestyle and demographic factors in a representative sample of Irish adults. Appetite 48(1):1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2006.03.329.

- Henseler, J., C.M. Ringle, and M. Sarstedt. 2015. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J.Acad. Mark. Sci. 43(1):115–135. doi: 10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8.

- Holbrook, M.B. 2005. Customer value and autoethnography: Subjective personal introspection and the meanings of a photograph collection. J. Bus. Res 58(1):45–61. doi: 10.1016/S0148-2963(03)00079-1.

- Hu, L.-T., and P.M. Bentler. 1999. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equation Model. 6:1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118.

- Huang, S., and C.H. Hsu. 2009. Effects of travel motivation, past experience, perceived constraint, and attitude on revisit intention. J Travel Res. 48(1):29–44. doi: 10.1177/0047287508328793.

- Hung, Y., T.M. de Kok, and W. Verbeke. 2016. Consumer attitude and purchase intention towards processed meat products with natural compounds and a reduced level of nitrite. Meat Sci. 121:119–126. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2016.06.002.

- Husby, I., B.L. Heitmann, and K.O.D. Jensen. 2009. Meals and snacks from the child’s perspective: The contribution of qualitative methods to the development of dietary interventions. Public Health Nutr. 12(6):739–747. doi: 10.1017/S1368980008003248.

- Jesionkowska, K., S.J. Sijtsema, D. Konopacka, and R. Symoneaux. 2009. Dried fruits and its functional properties from a consumer’s point of view. J. Hortic. Sci. Biotechnol. 84(6):85–88. doi: 10.1080/14620316.2009.11512601.

- Joshi, Y., and Z. Rahman. 2015. Factors affecting green purchase behaviour and future research directions. Int. Strategic Manage. Rev. 3(1–2):128–143. doi: 10.1016/j.ism.2015.04.001.

- Jun, J., & Arendt, S. (2016). Understanding healthy eating behaviors at casual dining restaurants using the extended theory of planned behaviour. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 53, 106-115.

- Kline, R.B. 2011. Principles and practice of structural equation modelling. 3rd ed. Guilford, New York, NY.

- Kocheri, S., and Shreyansh 2015. Consumption of fruits and vegetables: Global and Asian perspective. Technical report. Euromonitor International, London. http://de.slideshare.net/Euromonitor/consumption-of-fruits-andvegetables-global-and-asian-perspective

- Lee, W.L., K.D. Chiou, and K.S. Chang 2016, November. Tropical fruit breeding in Taiwan: Technology and cultivars. Paper presented in the proceedings of International Society for Horticultural Science-ISHS2016. 577–588. Ibadan, Nigeria. https://www.actahort.org/members/showpdf?session=19307.

- LTN. 2019. A primary processing farm will be set up on agricultural land. https://law.moj.gov.tw/ENG/LawClass/LawSearchContent.aspx?pcode=M0060072&kw1=process.

- Macht, M. 2008. How emotions affect eating: A five-way model. Appetite 50(1):1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2007.07.002.

- MacKinnon, D. P., Lockwood, C. M., Hoffman, J. M., West, S. G., & Sheets, V. 2008. A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychological Methods , 7(1), 83–104.

- Magalhães, R., A. Sánchez-López, R.S. Leal, S. Martínez-Llorens, A. Oliva-Teles, and H. Peres. 2017. Black soldier fly (Hermetia illucens) pre-pupae meal as a fish meal replacement in diets for European seabass (Dicentrarchus labrax). Aquaculture. 476:79–85. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2017.04.021.

- McDougall, G.H., and T. Levesque. 2000. Customer satisfaction with services: Putting perceived value into the equation. J. Serv. Mark. 14(5):392–410. doi: 10.1108/08876040010340937.

- Migliore, G., A. Galati, P. Romeo, M. Crescimanno, and G. Schifani. 2015. Quality attributes of cactus pear fruit and their role in consumer choice: The case of Italian consumers. British Food J. 117(6):1637–1651. doi: 10.1108/BFJ-04-2014-0147.

- Mogendi, J.B., H. De Steur, X. Gellynck, and A. Makokha. 2016. Consumer evaluation of food with nutritional benefits: A systematic review and narrative synthesis. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 67:355–371. doi: 10.3109/09637486.2016.1170768.

- Naughton, P., S.N. McCarthy, and M.B. McCarthy. 2015. The creation of a healthy eating motivation score and its association with food choice and physical activity in a cross sectional sample of Irish adults. Int. J. Behav. Nutr Phys. Act. 12(1):74–83. doi: 10.1186/s12966-015-0234-0.

- Nenadic, O., and M. Greenacre. 2007. Correspondence analysis in R, with two-and three-dimensional graphics: The ca package. J. Stat. Softw. 20(3):1–12.

- Norberg, M., H. Stenlund, B. Lindahl, C. Andersson, L. Weinehall, G. Hallmans, and J.W. Eriksson. 2007. Components of metabolic syndrome predicting diabetes: No role of inflammation or dyslipidemia. Obesity 15(7):1875–1885. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.222.

- Nystrand, B.T., and S.O. Olsen. 2020. Consumers’ attitudes and intentions toward consuming functional foods in Norway. Food Qual. Prefer. 80:103827. doi: 10.1016/j.foodqual.2019.103827.

- Paisley, C.M., and P. Sparks. 1998. Expectations of reducing fat intake: The role of perceived need within the theory of planned behaviour. Psychol. Health. 13(2):341–353. doi: 10.1080/08870449808406755.

- Pan, W.-H., H.-J. Wu, C.-J. Yeh, S.-Y. Chuang, H.-Y. Chang, N.-H. Yeh, and Y.-T. Hsieh. 2011. Diet and health trends in Taiwan: Comparison of two nutrition and health surveys from 1993–1996 and 2005–2008. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 20(2):238–250.

- Patch, C.S., L.C. Tapsell, and P.G. Williams. 2005. Attitudes and intentions toward purchasing novel foods enriched with omega-3 fatty acids. J. Nutr.Educ. Behav. 37(5):235–241. doi: 10.1016/S1499-4046(06)60277-7.

- Payne, N., F. Jones, and P.R. Harris. 2004. The role of perceived need within the theory of planned behaviour: A comparison of exercise and healthy eating. British J. Health Psychol. 9(4):489–504. doi: 10.1348/1359107042304524.

- Pereira-Netto, A.B. 2018. Tropical fruits as natural, exceptionally rich, sources of bioactive compounds. Int. J. Fruit Sci. 18(3):231–242. doi: 10.1080/15538362.2018.1444532.

- Revelle, W. 2012. Procedures for psychological, psychometric, and personality research [Computer software manual]. Northwestern University, Evanston, IL. http://www.personality-project.net/r/psych-manual.pdf. (R package version 1.3.2).

- Ruiz-Molina, M.E., and I. Gil-Saura. 2008. Perceived value, customer attitude and loyalty in retailing. J. Retail Leisure Property 7(4):305–314. doi: 10.1057/rlp.2008.21.

- Ryu, K., H.-R. Lee, and W.G. Kim. 2012. The influence of the quality of the physical environment, food, and service on restaurant image, customer perceived value, customer satisfaction, and behavioural intentions. Int. J. Contemp. Hospitality Manage. 24(2):200–223. doi: 10.1108/09596111211206141.

- Sabbe, S., W. Verbeke, and P. Van Damme. 2009. Perceived motives, barriers and role of labeling information on tropical fruit consumption: Exploratory findings. J. Food Prod. Market. 15(2):119–138. doi: 10.1080/10454440802316750.

- Sadler, M.J., S. Gibson, K. Whelan, M.A. Ha, J. Lovegrove, and J. Higgs. 2019. Dried fruits and public health: What does the evidence tell us? Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 70(6):675–687. doi: 10.1080/09637486.2019.1568398.

- Savige, G., A. MacFarlane, K. Ball, A. Worsley, and D. Crawford. 2007. Snacking behaviours of adolescents and their association with skipping meals. Int. J. Behav. Nutr Phys. Act. 4(36):1–9. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-4-36.

- Savurdan, H., and N. Aktas. 2011. Developing knowledge level scale of functional foods: Validity and reliability study. African J. Biotechnol. 10(61):13355–13360.

- Schösler, H., J. de Boer, and J.J. Boersema. 2014. Fostering more sustainable food choices: Can self-determination theory help? Food Qual. Prefer. 35:59–69. doi: 10.1016/j.foodqual.2014.01.008.

- Siegrist, M., J. Shi, A. Giusto, and C. Hartmann. 2015. Worlds apart. Consumer acceptance of functional foods and beverages in Germany and China. Appetite. 92:87–93. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2015.05.017.

- Sijtsema, S.J., K. Jesionkowska, R. Symoneaux, D. Konopacka, and H. Snoek. 2012. Perceptions of the health and convenience characteristics of fresh and dried fruits. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 49(2):275–281. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2012.04.027.

- Silvestri, C., M. Cirilli, M. Zecchini, R. Muleo, and A. Ruggieri. 2018. Consumer acceptance of the new red-fleshed apple variety. J. Food Prod. Market. 24(1):1–21. doi: 10.1080/10454446.2016.1244023.

- Smit, C.R., R.N. de Leeuw, K.E. Bevelander, W.J. Burk, L. Buijs, T.J. van Woudenberg, and M. Buijzen. 2018. An integrated model of fruit, vegetable, and water intake in young adolescents. Health Psychol. 37(12):1159–1166. doi: 10.1037/hea0000691.

- Sparks, P., M. Conner, R. James, R. Shepherd, and R. Povey. 2001. Ambivalence about health‐related behaviours: An exploration in the domain of food choice. British J. Health Psychol. 6(1):53–68. doi: 10.1348/135910701169052.

- Steptoe, A., T.M. Pollard, and J. Wardle. 1995. Development of a measure of the motives underlying the selection of food: The food choice questionnaire. Appetite. 25:267–284. doi: 10.1006/appe.1995.0061.

- Sulistyawati, I., S. Sijtsema, M. Dekker, R. Verkerk, and B. Steenbekkers. 2019. Exploring consumers’ health perception across cultures in the early stages of new product development. British Food J. 121(9):2116–2131. doi: 10.1108/BFJ-02-2019-0091.

- Sun, Y., C. Liang, and C.C. Chang. 2020. Online social construction of Taiwan’s rural image: Comparison between Taiwanese self-representation and Chinese perception. Tourism Manage. 76:103968. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2019.103968.

- Sweeney, J.C., and G.N. Soutar. 2001. Consumer perceived value: The development of a multiple item scale. J. Retailing 77(2):203–220. doi: 10.1016/S0022-4359(01)00041-0.

- Tabachnick, B.G., and L.S. Fidell. 2001. Using multivariate statistics. 4th ed. Allyn and Bacon, Boston, MA.

- TAITRA 2020. Dried fruits in Taiwan. https://www.taiwantrade.com/products/search?word=dried%20fruits&type=product&style=gallery.

- Teixeira, P.J., E.V. Carraça, M.M. Marques, H. Rutter, J.M. Oppert, I. De Bourdeaudhuij, and J. Brug. 2015. Successful behaviour change in obesity interventions in adults: A systematic review of self-regulation mediators. BMC Med. 13:84–95. doi: 10.1186/s12916-015-0323-6.

- Ullah, F., K. Min, M.K. Khattak, S. Wahab, N. Wahab, M. Ameen, N. Li, X. Wang, S.A. Soomro, and K. Yousaf. 2018. Effects of different drying methods on some physical and chemical properties of Loquat (Eriobotrya japonica) fruits. Int. J. Fruit Sci. 18(4):345–354. doi: 10.1080/15538362.2018.1435330.

- Verbeke, W. 2006. Functional foods: Consumer willingness to compromise on taste for health? Food Qual. Prefer. 17:126–131. doi: 10.1016/j.foodqual.2005.03.003.

- Verstuyf, J., H. Patrick, M. Vansteenkiste, and P.J. Teixeira. 2012. Motivational dynamics of eating regulation: A self-determination theory perspective. Imt. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 9(1):21–36. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-9-21.

- Wang, Y.M., and Y.-M. Wang. 2015. Decisional factors driving organic food consumption. British Food Journal, 117(3), 1066-1081.

- Wilson, P.M., W.M. Rodgers, C.M. Blanchard, and J. Gessell. 2003. The relationship between psychological needs, self-determined motivation, exercise attitudes, and physical fitness. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 33(11):2373–2392. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.2003.tb01890.x.

- Woodruff, R.B. 1997. Customer value: The next source for competitive advantage. J.Acad. Mark. Sci. 25(2):139–153. doi: 10.1007/BF02894350.

- Zeithaml, V.A. 1988. Consumer perceptions of price, quality, and value: A means-end model and synthesis of evidence. J. Mark. 52(3):2–22. doi: 10.1177/002224298805200302.