ABSTRACT

Superfruit refers to food items with exceptional health benefits. The study aims to determine the factors that influence the intention of Malaysians to consume dates; to compare the consumption patterns of dates between the B40 and non-B40 groups; and to explore both groups’ willingness to pay when date prices decrease or increase. Employing the survey research design, 329 survey questionnaires were collected and analyzed using structural equation modeling (SEM) and descriptive statistics. The results showed that attitude was not a significant predictor of intention to consume dates, but subjective norm significantly and positively predicted intention. The consumption patterns of B40 and non-B40 consumers were contrasting: The share of regular B40 consumers was lower than that of non-B40, while the group’s non-consumers were higher. The non-B40 group, relative to the B40 group, was more willing to pay higher prices for all types of dates, likely due to the former’s higher income level. Based on these findings, marketing managers should target health-conscious consumers so that they can encourage their friends and families to consume dates.

KEYWORDS:

Introduction

Superfruits are a marketing term used mainly to refer to fruits and vegetables that contain high nutritional contents (Gross, Citation2010). It is grouped under the broader umbrella of superfood, which refers to food items with exceptional health benefits. Crawford and Mellentin (Citation2008) asserted that superfruits are a novel, value-added niche in the nutrition market, which is created by the combination of marketing and science. The marketing strategy for superfruit emphasizes on its health benefits. The success of this strategy rests on six aspects: sensory appeal, novelty, convenience, control of supply, health benefit, and marketing (Crawford and Mellentin, Citation2008).

Branding a fruit as superfruit and superfood may increase its value, driven up by both marketing and scientific findings. This can be seen in the case of blueberry. The growing number of manuscripts published on the fruit’s many health benefits, and the labeling of the fruit as a superfruit by the media, have increased the fruit’s value (Crawford and Mellentin, Citation2008; Lila, Citation2013). The prevalent use of the superfood and superfruit labels, even without the backing of scientific evidence, has also increased their demand. Consumers, especially in Western countries, are demanding more healthy products, and they perceive fruits branded with these two labels as healthy, clean, and natural (CBI, Citation2015).

According to Hsu and Chen (Citation2014), consumers have worried about the quality of the food they eat. In understanding a consumer attitudes and intention toward food, Loudon and Della Bitta (Citation1993) define attitude as an enduring organization of motivational, emotional, perceptual and cognitive process with respect to some aspects of an individual’s world. Others argue that attitude refers to people’s evaluation of some concepts (Bagozzi, Citation1992). This abstraction process emerges continuously from the assimilation, accommodation, and organization of environmental information by individuals, to promote interchanges between the individual and the environment that, from the individual’s perspective, are favorable to preservation and optimal functioning (Haris et al., Citation2017).

Moreover, individual’s subjective norm is determined by normative beliefs, which is a function of perceived expectations of specific referent individuals or groups, and his or her motivation to comply with their expectations (Fishbein and Ajzen, Citation1975). Several studies have been conducted in understanding consumer’s attitudinal and normative factors on purchase intention particularly on food purchase and consumption (Bianchi and Mortimer, Citation2015; Haris et al., Citation2017; Matheny et al., Citation1987; Rana and Paul, Citation2017; Rutter and Bunce, Citation1989; Towler and Shepherd, Citation1992; Yadav and Pathak, Citation2016). Although shopping for food products can be considered as a routine purchase, food consumption choices are often symbolic in nature and they can signify a lot to consumers and to some significant others in their lives (Haris et al., Citation2017).

Since superfruit and superfood are terms initially established and predominantly used in marketing, they are not recognized by the scientific circle. However, due to its increasing popularity, there have been some attempts in defining both. In a symposium held by the United Nations Food and Agricultural Organization, researchers have defined some characteristics inherent to superfruits, such as the presence of significant nutritional and extra-nutritional composition, bioactive properties, unique appearance and taste, and exoticness. Fruits that satisfy the first two criteria fall into the superfruit category. The nutritional properties of such fruits should also be supported by scientific proofs (FAO, Citation2013).

Scientific studies have found that most superfruits are nutritionally equal or superior to other fruits. Gross (Citation2010), using a set of criteria, listed 20 superfruits that are richer in nutritional components and health benefits compared to non-superfruits. This list includes mango, fig, date, pomegranate, and guava, among others. Dates are abundant in dietary fiber, various vitamins and minerals, phytosterols, carotenoids, and polyphenols (Al-Farsi & Lee, Citation2012). The fruit also has multiple medicinal benefits: it is antioxidant and anti-inflammatory, and provides protection to the liver, stomach, and kidney (Al-Orf et al., Citation2012). This fruit can therefore be consumed as a nutritional supplement to fulfil the recommended daily nutrient intake recommended by the Ministry of Health Malaysia.

The import quantity and value of dates in Malaysia have steadily increased since 2000. In 2000, Malaysia imported 11,158 tonnes of dates worth 9.8 USD million. In 2013, the volume increased to 19,421 tonnes, and its value to 47.2 USD million (FAO, Citation2017a). The global dates production also increased during the same period. It was 6.5 million tonnes in 2000, and in 2013 it was 7.6 million tonnes (FAO, Citation2017b). The producer prices for dates in Algeria, Iran, Iraq, Pakistan, and Tunisia, all major producers, have steadily increased (FAO, Citation2017c). These statistics indicate the increasing price, production, and consumption of dates domestically and globally.

The aforementioned factors could potentially increase the value of dates and subsequently price out consumers with lower purchasing power, which, in the Malaysian context, is the B40 group. Therefore, this study attempts to (1) determine the factors potentially affect consumers’ intention to consume dates; (2) examine dates consumption pattern of B40 and Non-B40 groups; and (3) explore both groups’ willingness to pay when date price changes.

Literature Review

Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA) and Fruits Consumption

The theory of reasoned action (TRA) supposes that attitudes and subjective norms can influence intention, which in turn influences behavior (Ajzen and Fishbein, Citation1980; Fishbein and Ajzen, Citation1975). TRA specifies that individual performance of a given action is mainly determined by one’s intention to perform that behavior. Intention itself is influenced by two principal factors: the individual’s attitude toward the action and the influence of the individual’s social environment. The theory has been applied in many areas, including food consumption, education, green hotels, and takaful (Husin et al., Citation2016; Hussain and Noor, Citation2018; Mansor et al., Citation2015). In numerous studies, the model has proved its importance, strength, and validity.

TRA has likewise been used prevalently to understand food purchase and consumption behaviors (Bianchi and Mortimer, Citation2015; Matheny et al., Citation1987; Rana and Paul, Citation2017; Rutter and Bunce, Citation1989; Towler and Shepherd, Citation1992; Yadav and Pathak, Citation2016). Although shopping for food products can be considered as a routine purchase, food consumption choices are often symbolic in nature and they can signify some information about consumers and their significant others (Bourdieu, Citation1984; Mennell, Citation1985; Warde, Citation1997). For example, Choo et al. (Citation2004) found that subjective norms play a major role in Indian consumers’ decision to purchase new food products. This result is in tandem with the belief that people living in a collective culture (like India) place more import on conforming to social norms. However, Eves and Cheng (Citation2007) found that attitude, relative to subjective norms, is a more important determinant of intention to buy new food products among English and Chinese consumers. This result contrasts with the belief that in a collectivist culture, such as China, subjective norms are more likely to influence behavioral intention. However, on further investigation, this discrepancy can probably be attributed to the different demographics of the samples used in the studies. The sample of the Indian study came from both urban and rural areas, while in China only residents of some major cities were considered. Eves and Cheng (Citation2007) acknowledged this, stating that the results might be different if they include samples from rural areas.

Kaur and Singh (Citation2017) highlighted four broad determinants of functional food purchasing behavior through a systematic review. These are (1) personal factors e.g., demographic characteristics, habits, intention, and knowledge; (2) psychological factors, including perception and attitude, belief and values, motivation, trust, and confidence; (3) cultural and social factors, such as the roles of family and friends, cultural and social norms, geographical factors, and ethnic and social status; and (4) factors related to functional food products e.g., functional components, convenience, price, and taste.

In addition, Moreira et al. (Citation2015) suggested that individual, social, environmental, and economic factors can influence the consumption behavior of nutritious food. Nutritious food generally has a higher price compared to other types of food; hence, its consumption is limited only to those who can afford it. Rana and Paul (Citation2017) found that the reasons for purchasing organic food in developing and developed countries differ. Based on their survey, people in developed countries purchase organic food because of the environment, health benefits, and knowledge, while those in developing countries do so because of their need for food safety.

The theoretical framework shows that intention is directly influenced by attitudes and subjective norms (Fishbein and Ajzen, Citation1975). A review of past literature also reveals several variables that can determine dates consumption. As dates consumption behavior has not been thoroughly examined in Malaysia, the study only constructed a simple two-factor TRA model to explain the behavior. In this case, it posited that a psychological factor (attitude) and a cultural and social factor (subjective norm) positively influence the intention of Malaysians to consume dates (). Two hypotheses, whose purpose is to answer the first research question, have been formulated:

H1:Attitude has a positive influence on the intention of dates consumption.

H2:Subjective norm has a positive influence on the intention of datesconsumption.

Willingness to Pay for B40 and Non-B40 Groups in Malaysia

Households in Malaysia are divided into three income categories: bottom 40% (B40), middle 40% (M40), and top 20% (T20). Based on 2014 data, on average a B40 household earns RM2,537; middle 40 earns RM5,662; and top 20 earns RM6,141. Approximately 64.7% of B40 households depend on a single income (Economic Planning Unit, Citation2015). Housing and utilities are the main expense for the T20 and M40 groups, while B40 households mostly spend on food and nonalcoholic beverages. Here, Engel’s law – that the proportion of food expenditure would decrease along with the increase in income – is evident. Health expenditure is also higher in the first two groups compared to B40 (Mahidin, Citation2015), suggesting that the non-B40 group is able to spend more on health.

The spending pattern of those groups reveal an intriguing case. According to the estimations of the Khazanah Research Institute (Citation2016), a household must spend at least between RM25.21 to RM38.45 per day, depending on city, for a nutritionally adequate diet. However, this is unattainable for a household whose monthly income is between RM2,000 and RM4,000, as its food budget is around RM600. It is likely that the adults and children living in such a household are unable to satisfy their daily required nutrition intake. To deal with this issue, the government has introduced several initiatives, such as the Poor Students Provident Fund (KWAPM) and Food Supplement Plan (RMT). While these aids target the poor, not all of them may be excluded for certain circumstances, such as proximity of residence to welfare center, access to information on assistances, and so forth. Providing nutritional and health support becomes the challenge for both consumers and policy makers.

Research Methodology

Sample and Location

The stratified random sampling method was employed to accomplish the research objectives. A total of 329 completed questionnaires were distributed and collected in 30 districts across eight states. The sample states were stratified according to monthly household income: Kuala Lumpur, Putrajaya, and Selangor represent the high-income states; Negeri Sembilan and Pahang the middle-income states; and Kedah, Perlis, and Kelantan the low-income population states. The sampling frame was further stratified into 30 most populous districts across the eight states. The population of each district was then classified into the three socioeconomic classes (B40, M40, and T20). The sample was taken proportionately from each stratum. Enumerators were appointed to distribute the survey questionnaires.

Questionnaire Design

The items were designed based on dates and food consumption research, common knowledge of local consumers, and informal discussions with four subject-matter experts. The questionnaire was pre-tested to assess the total time required to complete all of the questions (6–7 minutes), as well as to ensure the understandability of the questions.

The questionnaire comprises 24 questions in two sections. The first section inquires the demographic background of the respondents, covering gender, age, marital status, education, state of origin, occupation, and monthly income. It continues with questions regarding dates consumption behavior, such as the reasons for purchasing dates, types of dates purchased, and frequency of purchase.

In section two, the questions pertain to the attitude, subjective norm, and intention toward consuming dates. Questions concerning attitude include knowledge of health benefits, price, texture/hardness, preferred size, and taste. Questions on subjective norm focus on how family and friends influence the purchasing behavior. Meanwhile, inquiries on intention relate to the consumer’s future intention or plan to purchase dates. These items are measured on a five-point Likert scale, from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5).

The questionnaire also includes questions about the consumption patterns of the respondents. These include frequency of purchase and type of dates purchased. Meanwhile, consumers’ willingness to pay for dates was measured by asking whether they are willing to pay at the base and incremental prices (i.e., 10%, 20%, or 30% increase).

Data Analysis

Research questions one was analyzed using PLS-SEM, while questions two and three were descriptively analyzed using Microsoft Excel and SPSS 24. Besides descriptive analysis, where applicable, independent t-test was also carried out. The PLS-SEM method is further discussed below.

Partial Least Squares-Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM)

PLS-SEM is more useful than covariance-based SEM when analyzing predictive research models that are in the early stages of theory development (Dijkstra and Henseler, Citation2015; Gimbert et al., Citation2010; Henseler, Citation2010; Henseler et al., Citation2016; Rezaei and Ismail, Citation2014). It can also deal with a small sample size and non-normal conditions of latent constructs (Chin, Citation1998). The statistical objective of PLS-SEM is to maximize the explained variance of the endogenous latent constructs (Hair et al., Citation2011). The common approach is to present the results in two phases (Chin, Citation2010): first is to focus on the reliability and validity of the items, and second involves the structural model assessment (Hair et al., Citation2013). The reliability and validity of the measures can be assessed simultaneously, and the relationships between these constructs can be predicted. The acceptable values for reliability and convergent and discriminant validity are shown in .

Table 1. Satisfactory level

Results

Socio-Demographic Profile of Respondents

illustrates the respondents’ profile. They were largely female and in the working age. Most of them were married and educated at secondary and tertiary levels. The respondents mostly worked as employees, whether in the public or private sector. Almost 60% of them belonged to the B40 group.

Table 2. Socio-demographic profiles

shows the reasons for purchasing dates and frequency of buying dates for both B40 and non-B40 groups. There were no distinctive differences between both groups, as they considered taste, family influence, and health benefits to be the most important reasons. Similarly, the types of purchased dates and frequency of purchase were more or less similar (). Ajwa and Mariami were the most popular varieties, and they typically buy them once a month or year.

Table 3. Reasons for purchasing dates

Table 4. Types of dates bought

Factors Influencing Intention to Consume Dates

Descriptive Analysis of Items

The descriptive statistics of the constructs’ items are shown in . There were no significant differences between both B40 and non-B40 groups, save for two items of attitude on the health benefits and tastiness of dates. In both cases, the means of the non-B40 group were higher. The group may be more aware of the health benefits of dates due to their higher level of education. They could also find dates tastier as they can afford better quality dates.

Table 5. Factors influencing fruit consumption patterns

Item Reliability and Validity

As show, the items were reliable and valid. The Cronbach’s alphas and composite reliability for all factors were above the acceptable level of 0.60. One item (ATT1 = 0.47) was deleted as it did not reach the acceptable threshold of 0.50. Convergent validity was established, though the average variance extracted (AVE) of attitude was below the suggested level. There was no issue with discriminant validity, as the square root values of the three constructs’ AVE (0.636, 0.716 and 0.938) were greater than the correlations between the constructs.

Table 6. Reliability and validity analysis

Table 7. Item loadings and cross loadings

Table 8. Discriminant Validity

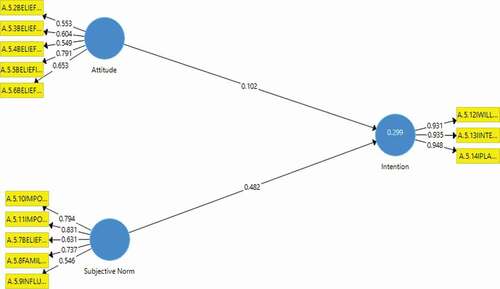

Inner Model Results

The inner model was evaluated using R2, Q2, and Goodness of Fit (GoF). The value of the R2 was 0.299. The outer model can be assessed by looking at Q2 (predictive relevance). According to Rezaei et al. (Citation2016), Q2 is equal to effect size, where 0.02 is small, 0.15 is medium, and 0.35 is large. A cross-validated redundancy greater than 0 shows the presence of predictive relevance (Chin, Citation1998). Computed using Tenenhaus et al. (Citation2005) formula, the cross-validated redundancy result (the Stone-Geisser test Q2) for this study was 0.299 > 0, indicating that the model has predictive relevance. Finally, the model’s Goodness-of-Fit (GoF) was manually computed using Tenenhaus et al. (Citation2005) formula. This returned a value of 0.228, placing it into the small fit category. Taken together, the model is robust and has adequate explanatory power, and thus it can be used to test the hypotheses.

illustrates the structural model, while shows the results of the hypothesis testing. The corrected R2 in refers to the explanatory power of the predictor variables on the dependent construct. The R2 values of attitude and subjective norms were 10 and 48%, which were respectively equal and above the recommended threshold of 10% (Falk and Miller, Citation1992).

Table 9. Structural Model Results

The hypotheses were tested by scrutinizing its path coefficient and utilizing the bootstrapping resampling technique with 500 sub-samples (Chin, Citation1998). Contrary to the expected result, attitude had a non-significant relationship with intention (β = 0.102). Thus, H1 was not supported. However, subjective norm had a significant and positive impact on intention (β = 0.482), indicating that H2 was supported.

Consumption Patterns Between Socioeconomic Groups

According to their consumption pattern, the respondents were categorized into three groups: regular, occasional, and non-regular (). Almost half of the respondents (44%), regardless of their household income, consumed dates at least once a week or every day. Occasional and regular consumers were almost equal. Stratified by income group, B40 and non-B40 consumers seemingly showed a contrasting pattern. The share of regular B40 consumers was lower than that of non-B40, while the group’s non-consumers were higher. It appears that their more constrained food budget does not afford them the luxury to consume dates more regularly.

Table 10. Consumption patterns between socioeconomic groups (N = 329)

Willingness to Pay for Dates

As shown in , the non-B40 group was generally willing to pay higher prices for all types of dates than the B40 group. The ability to pay higher prices among non-B40 was mainly because they earned higher income than the B40 group. For all consumers, the maximum willingness to pay was obtained for “others”, followed by Rotab, Mariami, and Ajwa. Similar patterns were found for both B40 and non-B40 groups. The reason for this may be due to the fact that (1) they typically buy date varieties other than the named three and (2) other varieties are typically cheaper.

Table 11. Willingness to pay by group

Discussion and Conclusion

This study has surveyed 329 respondents to investigate the factors influencing intention to consume dates, dates consumption pattern, and willingness to pay for dates. For the first objective, attitude did not significantly influence intention to purchase, but subjective norms did. These findings are partially consistent with past studies on fruits and vegetables consumption (e.g., Huang et al., Citation2020; Menozzi et al., Citation2015; Rodriguez et al., Citation2017), which found that attitude and subjective norms are significant predictors of intention to consume fruits. The non-significant attitude and significant subjective norms perhaps suggest that dates consumption in Malaysia is mostly driven by the influence of friends and families. It would also suggest that a consumer’s awareness of the health benefits of dates does not necessarily motivate him to consume them unless his immediate surroundings are also eating dates or encouraging him to do so. In most Muslim states, dates are typically consumed once a year during the month of Ramadhan. The fasting month creates an atmosphere of piety, and in it as well is the tradition of purchasing and consuming dates in homes and places of worship. The consumer does not necessarily need to fully understand the benefits of consuming dates, but he would nonetheless consume them should they be available at either of the two locations above. In fact, influenced by the subjective norms prevalent during the month, he could also be encouraged to buy dates. However, this assertion is not tested in the study.

With regards to the second and third objectives, the results showed that the non-B40 group was a more regular consumer of dates and was more willing to pay for dates should their prices increase. This is consistent with the findings of Ion and Dobre (Citation2018) and Othman et al. (Citation2013), which showed that fruits consumption increases along with the rise in income level. Similarly, these results are consistent with Engel’s law. The higher willingness to pay of the non-B40 group is likely due to their more flexible food budget. The B40 group, on the other hand, mostly depends on a single source of income, and any shocks would necessitate its households to reassess their priorities. In this case, since dates are not a major source of nutrition for Malaysian households, especially due to its relatively higher price compared to local fruits and vegetables, dates consumption will likely decline significantly if their prices go up. This pattern is evident for all households, but especially among the B40. Yet despite their prices, if the dates do in fact provide more nutritional benefits per Malaysian ringgit than local fruits, their consumption should still be promoted. Therefore, marketing managers may advertise dates as part of a healthier lifestyle that can fulfil the recommended daily nutrient intake.

The study is the first, to the authors’ best knowledge, to examine the consumption behavior, consumption pattern, and willingness to pay for dates in Malaysia. The study has also tested the ability of TRA to explain the dates consumption behavior of Malaysians. While not all hypotheses were found to be significant, the results still partially support the findings of past research on fruits consumption. Unlike those studies – which found that individuals consume fruits because they understand their benefits and are influenced by their surroundings – this study has revealed that attitude plays no significant role in explaining consumption behavior; rather, it is shaped only by the individual’s environment. This is likely because the tradition in Malaysia, especially among Muslims, is to consume dates during certain religious seasons. Outside of those periods, dates consumption can be said to be rare. However, this conclusion must still be strengthened with further studies.

The findings also have several implications to marketing. First, in their marketing strategy, managers should emphasize heavily on the medicinal and health benefits of dates. Second, the influence of family and friends to increase dates consumption should be accounted for. By concentrating the marketing strategy on the health benefits of dates and targeting health-conscious consumers, marketers can indirectly gain more consumers, as the health-conscious consumers would likely encourage their families and friends to consume dates. This way, as well, the frequency of dates consumption could be increased, not only once but perhaps several times a year. Third, marketers should also segment their target market so the dates do not outprice their target market, hence premium quality dates, for instance, should be targeted for the non-B40 group.

There are some limitations that can be improved by future research. First, this study has only attempted to explain the behavior of consumers using TRA. Its parsimony perhaps does not lend to a full disclosure of the consumption determinants, hence future studies may apply the basic and extended theory of planned behavior to identify other possible determinants (Canova and Manganelli, Citation2016; Damghanian and Alijanzadeh, Citation2018; Sniehotta et al., Citation2014). Second, the structural model did not differentiate between the income groups. The heterogeneity between B40 and non-B40 groups likely caused a hypothesis to be rejected. Future research may consider building two regression models to compare between the groups. Analysis of variance may also be used for comparison purposes. Third, the consumption pattern and willingness to pay for dates have not been analyzed using inferential analysis, and as such the generalizability of the findings is questionable. In addition, other techniques to elicit willingness to pay, such as the bidding game, could also be employed to either support or challenge the present findings.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ajzen, I., and M. Fishbein. 1980. Understanding attitudes and predicting social behavior. Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ.

- Al-Farsi, M. A., & Lee, C. Y. (2012). The functional value of dates. In A. Manickavasagan, Essa, M., Sukumar, E. (Ed), In dates. production, processing, food, and medicinal values (pp. 351-358). CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL, USA.

- Al-Orf, S.M., M.H.M. Ahmed, N. Al-Atwai, H. Al-Zaidi, A. Dehwah, and S. Dehwah. 2012. Review: Nutritional properties and benefits of the date fruits (Phoenix dactylifera L.). Bull. National Nutr.Inst. Arab Republic Egypt 39:97–129.

- Bagozzi, R. P. (1992). The Self-Regulation of Attitudes, Intentions, and Behavior, Social Psychology Quarterly, 55(2), Special Issue: Theoretical Advances in Social Psychology, 178–204.

- Bianchi, C., and G. Mortimer. 2015. Drivers of local food consumption: A comparative study. British Food J. 117(9):2282–2299. doi: https://doi.org/10.1108/BFJ-03-2015-0111.

- Bourdieu, P. 1984. Distinction: A social critique of the judgement of taste. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA.

- Canova, L., and A.M. Manganelli. 2016. Fruit and vegetables consumption as snacks among young people. The role of descriptive norm and habit in the theory of planned behavior. TPM-testing, psychometrics. Methodol. Appl. Psychol. 23(1):83–97.

- CBI. 2015. CBI product factsheet: Superfoods in Europe. Ministry of Foreign Affairs, The Hague, The Netherlands.

- Chin, W.W. 1998. The partial least squares approach for structural equation modeling, p. 295–336. In: G.A. Marcoulides (ed.). Modern methods for business research. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers, Mahwah, NJ.

- Chin, W.W. 2010. Bootstrap cross-validation indices for PLS path model assessment, p. 83–97. In: V. Esposito Vinzi, W.W. Chin, J. Henseler, and H. Wang (eds.). Handbook of partial least squares: Concepts, methods and applications. Springer, Heidelberg, Dordrecht, London and New York, NY.

- Choo, H., J.-E. Chung, and D.T. Pysarchik. 2004. Antecedents to new food product purchasing behavior among innovator groups in India. Eur. J. Mark. 38(5/6):608–625. doi: https://doi.org/10.1108/03090560410529240.

- Crawford, K., and J. Mellentin. 2008. Successful superfruit strategy: How to build a superfruit business. New nutrition business, London, United Kingdom.

- Damghanian, M., and M. Alijanzadeh. 2018. Theory of planned behavior, self-stigma, and perceived barriers explains the behavior of seeking mental health services for people at risk of affective disorders. Soc. Health Behav. 1(2):54. doi: https://doi.org/10.4103/SHB.SHB_27_18.

- Dijkstra, T.K., and J. Henseler. 2015. Consistent and asymptotically normal PLS estimators for linear structural equations. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 81:10–23. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csda.2014.07.008.

- Eves, A., and L. Cheng. 2007. Cross-cultural evaluation of factors driving intention to purchase new food products – Beijing, China and South-East England. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 31(4):410–417. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1470-6431.2007.00587.x.

- Falk, R.F., and N.B. Miller. 1992. A primer for soft modelling. University of Akron, Akron, Ohio.

- FAO. (2013). International symposium on superfruits: Myth or Truth? Proceedings. Food Agriculture Organizations, Ho Ci Minh, Vietnam.

- FAO. (2017a). Food agriculture organizations statistics (FAOSTAT): Crops and livestock products. [online]. http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/TP (accessed on 15 September 2017).

- FAO. (2017b). Food agriculture organizations statistics (FAOSTAT): Crops. [online]. http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QC (accessed on 15 Sep 2017).

- FAO. (2017c). Food agriculture organizations statistics (FAOSTAT): Producer Prices – Annual. [online]. http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/PP (accessed 15 September 2017).

- Fishbein, M., and I. Ajzen. 1975. Belief, attitude, intention and behavior. An introduction to theory and research. Addison-Wesley, Massachusetts.

- Gimbert, X., J. Bisbe, and X. Mendoza. 2010. The role of performance measurement systems in strategy formulation processes. Long Range Plan 43(4):477–497. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2010.01.001.

- Gross, P. 2010. Superfruits. McGraw Hill Education, New York, United States.

- Hair, J.F., C.M. Ringle, and M. Sarstedt. 2011. PLS-SEM: Indeed, A silver bullet. J. Marketing Theory Pract. 19(2):139–151. doi: https://doi.org/10.2753/MTP1069-6679190202.

- Hair, J.F., G.T.M. Hult, C. Ringle, and M. Sarstedt. 2013. A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

- Haris, A., Z. Kefeli, N. Ahmad, S.N.M. Daud, N.A. Muhamed, S.A. Shukor, and A.F. Kamarubahrin. 2017. consumers’ intention to purchase dates: Application of theory of reasoned action (TRA). Malaysian J. Consum. Family Eco. 20:1–15.

- Henseler, J. 2010. On the convergence of the partial least squares path modeling algorithm. Comput. Stat. 25(1):107–120. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00180-009-0164-x.

- Henseler, J., G. Hubona, and P.A. Ray. 2016. Using PLS path modeling in new technology research: Updated guidelines. Ind. Manage. Data Syst. 116(1):2–20. doi: https://doi.org/10.1108/IMDS-09-2015-0382.

- Hsu, C.L., and M.C. Chen. 2014. Explaining consumer attitudes and purchase intentions toward organic food: Contributions from regulatory fit and consumer characteristics. Food Qual. Prefer. 35:6–13. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2014.01.005.

- Huang, J., G. Antonides, and F. Nie. 2020. Social-psychological factors in food consumption of rural residents: The role of perceived need and habit within the theory of planned behavior. Nutrients 12(4):1203. doi: https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12041203.

- Husin, M.M., N. Ismail, and A.A. Rahman. 2016. The roles of mass media, word of mouth and subjective norm in family Takaful purchase intention. J. Islamic Marketing 7(1):59–73. doi: https://doi.org/10.1108/JIMA-03-2015-0020.

- Hussain, F.N., and A.M. Noor. 2018. An assessment of customer’s preferences on the selection of Takaful over conventional: A case of Saudi Arabia. Tazkia Islamic Finance & Bus. Rev. 12(1):33–60.

- Khazanah Research Institute. (2016). The state of household II. 2016 of Annual Report Khazanah Nasional Berhad, Khazanah Nasional Berhad, Kuala Lumpur. Malaysia.

- Ion, R.A., and I. Dobre. 2018. The influence of people income of fruits consumption in Romania. Int. Conf. Competitiveness Agro-food & Environ. Econ. Proc., The Bucharest University of Economic Studies. 7:75–81.

- Kaur, N., and D.P. Singh (2017). Deciphering the consumer behaviour facets of functional foods: A literature review, Appetite, doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2017.01.033.

- Lila, M.A. (2013). Superfruits: A. In: Gimmick or scientifically supported? How the science impacts the marketplace or vice versa International Symposium on Superfruits: Myth or Truth? Proceedings (pp. 12–16). FAO, Ho Ci Minh, Vietnam.

- Loudon, D. L., & Della Bitta, A. J. (1993). Consumer Behaviour: Concepts and Applications (4th ed). McGraw Hill: Auckland.

- Mahidin, M. U. (2015). The changing pattern of Malaysia’s household consumption expenditure. MIER National Economic Outlook Conference 2016-2017, 24-25 November 2015. Malaysian Institute of Economic Research (MIER), Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

- Mansor, K.A., R.M.N. Masduki, M. Mohamad, N. Zulkarnain, and N.A. Aziz. 2015. A study on factors influencing Muslim’s consumers preferences towards Takaful products in Malaysia. Romanian Stat. Review 2:79–89.

- Matheny, A.P., Jr., R. Wilson, and A. Thobcn. 1987. Home and mother: Relations with infant temperament. Dev. Psychol. 23(3):323–331. doi: https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.23.3.323.

- Mennell, S. 1985. All manners of food: Eating and taste in England and France from the middle ages to the present. Blackwell, Oxford/New York.

- Menozzi, D., G. Sogari, and C. Mora. 2015. Explaining vegetable consumption among young adults: An application of the theory of planned behaviour. Nutrients 7(9):7633–7650. doi: https://doi.org/10.3390/nu70953577633-7650.

- Moreira, C.C., E.A.M. Moreira, and G.M. Fiates. 2015. Perceived purchase of healthy foods is associated with regular consumption of fruits and vegetables. J. Nutri. Edu. Behav. 47(3):248–252. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneb.2014.12.003.

- Othman, K.I., M.S.A. Karim, R. Karim, N.M. Adzhan, and N.A. Halim. 2013. Consumption pattern on fruits and vegetables among adults: A case of Malaysia. Acad. J. Interdiscip. Stud. 2(8):424–430.

- Rana, J., and J. Paul. 2017. Consumer behaviour and purchase intention for organic food: A review and research agenda. J. Retailing Consum. Serv. 38:157–165. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2017.06.004.

- Rezaei, A., A. Nasirpour, H. Tavanai, and M. Fathi. 2016. A study on the release kinetics and mechanisms of vanillin incorporated in almond gum/polyvinyl alcohol composite nanofibers in different aqueous food simulants and simulated saliva. Flavour Fragrance J. 31(6):442–447. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/ffj.3335.

- Rezaei, S., and W.K.W. Ismail. 2014. Examining online channel selection behaviour among social media shoppers: A PLS analysis. Int. J. Electron. Marketing & Retailing 6(1):28–51. doi: https://doi.org/10.1504/IJEMR.2014.064876.

- Rodriguez, L., S. Kulpavaropas, and S. Sar. 2017. Testing an extended reasoned action framework to predict intention to purchase fruits with novel shapes. J. Agric. Food Inf. 18(2):161–180. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/10496505.2017.1300536.

- Rutter, D.R., and D.J. Bunce. 1989. The theory of reasoned action of Fishbein and Ajzen: A test of Towriss’s amended procedure for measuring beliefs. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 28(1):39–46. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8309.1989.tb00844.x.

- Sniehotta, F.F., J. Presseau, and V. Araújo-Soares. 2014. Time to retire the theory of planned behaviour. Health Psychol. Rev. 8(1):1–7. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/17437199.2013.869710.

- Tenenhaus, M., V. EspositoVinzi, Y.-M. Chatelin, and C. Lauro. 2005. PLS path modelling. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 48(1):159–205. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csda.2004.03.005.

- Towler, G., and R. Shepherd. 1992. Modification of Fishbein and Ajzen’s theory of reasoned action to predict chip consumption. Food Qual. Prefer. 3(1):37–45. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/0950-3293(91)90021-6.

- Economic Planning Unit. (2015). Strategy paper 2: Elevating B40 households towards a middle-class society in eleventh Malaysian plan. Percetakan Nasional Malaysia Berhad, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

- Warde, A. 1997. Consumption, food, and taste: Culinary antinomies and commodity culture. Sage, London.

- Yadav, R., and G.S. Pathak. 2016. Intention to purchase organic food among young consumers: Evidences from a developing nation. Appetite. 96:122–128. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2015.09.017.