Abstract

The Women’s Center of Jamaica Foundation’s (WCJF) Programme for Adolescent Mothers)—has supported pregnant girls and adolescent mothers to have uninterrupted access to education and allied services since 1978. This paper analyzes the conception, establishment, scale up and sustainability of the Programme. The Programme evolved from a small, local initiative into a national and international model. Repeat pregnancy has remained under 2% among programme beneficiaries since inception. While the core package of interventions has remained for the past 40 years, some new dimensions have been added, with the most recent one being support for transition to higher education, all of which are aimed at strengthening the impact of the Programme. The achievements of the Programme were propelled prominently by a progressive national policy environment with the support of several non-state actors. The PAM demonstrates the value of sustained cross-sectoral support, spearheaded, or fully supported by the state in providing opportunities for adolescent mothers.

Keywords:

Introduction

The international community has demonstrated keen interest in preventing unwanted pregnancy and childbearing among adolescents (Chandra-Mouli et al., Citation2013; Ingham, Citation2016; Salam et al., Citation2016; UNFPA, Citation2013; WHO, Citation2011) and also in supporting them to chart out their life goals after childbirth and achieve them. In part, this interest drove the commitment of the World Bank to devote considerable portions of the 2007 World Development Report to offering second chances to young people to rebuild their potentials after dropping out of school for diverse reasons, including for childbirth. This interest is based on the recognition that the social (Archer & Williams, Citation2005; Neill, Citation2015), health (Blencowe et al., Citation2019; Mathewson et al., Citation2017; Reinicke, Citation2021; Walker & Holtfreter, Citation2021), economic (Card & Wise, Citation2018; Hoffman & Maynard, Citation2008) and political benefits that can accrue from such investments are colossal and lasting (Jimenez et al., Citation2007; World Bank, Citation2006).

Policy discussions about adolescent childbearing in the Caribbean go back to the early 1970s, beginning with several surveys that were conducted to understand the scale of the phenomenon. These surveys showed that adolescent fertility ranged from approximately 77 births per 1000 women (15–19 years) in Trinidad and Tobago to 150 per 1000 women (15–19 years) in St Lucia and St Vincent. The adolescent birth rate (i.e., births per 1000 adolescents aged 15–19 years) was 113 in Jamaica (Wulf, Citation1986). They also showed that 60% of all first births in the region occurred among adolescents, and half of these births occurred in children, i.e., girls aged 17 years and below (Jagdeo, Citation1984). Given the generally low levels of formal education, limited employment opportunities, and restrictive social norms around the roles of women and men, early marriage and motherhood was not generally viewed as detrimental to girls and their families. However, with rising female participation in formal education and the labor market, it became apparent that adolescents who could not complete formal education stood a higher risk of losing out on emerging economic opportunities that didn’t exist for their parents’ generation (Levine et al., Citation1985).

Concerned about this situation, several governments in Latin America and the Caribbean initiated adolescent health programmes to prevent early pregnancy. For instance, in Mexico, the Centro de Orientación para Adolescentes (Adolescent Guidance Center – CORA) was established in 1978 to provide sexuality education and contraceptive services for young people. In Guatemala, the El Camino (The Way) was introduced in 1979 to offer sexuality education, contraceptive services, medical care for commonly occurring health problems, and sport opportunities for young people (Wulf, Citation1986). In Jamaica, a number of programmes from the mid-1970s on, targeted adolescents broadly: the Jamaican YWCA and the Jamaican Federation of Women collaborated with the Family Planning Board of Jamaica to conduct sexuality and family planning education for adolescents and the Unitarian Universalist Committee of Boston supported the Teenage Family Life Education Project (McNeil et al., Citation1983).

A common goal across all these programmes was delaying first births among adolescents and young people. Taking a detour from this paradigm, the Women’s Center of Jamaica Foundation (WCJF) initiated an innovative intervention called the Programme for Adolescent Mothers (PAM). The first of its kind in the Caribbean, the PAM sought to provide opportunities for pregnant girls and adolescent mothers to continue their education while pregnant and to reenter school after giving birth. In this paper, we look back on the conceptualization and evolution of the WCJF PAM and its journey over a period of 40 years to become a model of best practice for supporting adolescent mothers, particularly in the Caribbean. While this paper is timely, we acknowledge the existence of similar documentations on interventions to prevent unintended and repeat pregnancy among adolescents (Asheer et al., Citation2014; Frederiksen et al., Citation2018; Govender et al., Citation2018; Hindin et al., Citation2016; Key et al., Citation2001; Lin et al., Citation2019; Schaffer et al., Citation2008; Stevens et al., Citation2017; Tocce et al., Citation2012). Also, in terms of programmes, the Pathfinder International (Chau et al., Citation2015) and Save the Children (Save the Children, Citation2020) are providing services and support to adolescent mothers that go beyond preventing repeat pregnancies to tackling the holistic needs of adolescent mothers. The school reentry policy in Zambia (Chiyota & Marishane, Citation2020; Zuilkowski et al., Citation2019), Eswatini (Thwala et al., Citation2022) and Kenya (Undie et al., Citation2015) are some recent examples. This paper adds to the growing documentation of exemplary health and social programmes for adolescents in the global South. Specifically, this paper seeks to answer the following questions:

What circumstances/contextual drivers led to the conception of the PAM?

What is the evidence on the effectiveness of PAM in achieving its objectives?

What factors led to national expansion/scale-up?

What factors have helped to sustain the programme since inception?

Jamaica in context

The 1960s and 1970s were a time of great social and political change, both globally and in Jamaica. Changes in government in Jamaica in the 1970s, combined with the growth and strength of the local women’s movements, led to the creation of new laws and policies, and government programmes increasingly focused on the health and well-being of Jamaican women, including adolescent girls and young women. The creation of the Bureau of Women’s Affairs within the Jamaican Government in 1975 was symbolic of the increased attention to the status and needs of women within Jamaican society (McNeil et al., Citation1983).

Jamaica is a trailblazer in promoting access to contraception in the Caribbean region. It began its journey as early as 1967, when it first established the National Family Planning Board (McNeil et al., Citation1983). However, this did not translate into high uptake and use of contraceptives among adolescents, which is typical of contexts where there is limited or lack of access to such services to young people. In consequence, fertility rates were increasing rapidly amongst 15–19-year-olds, rising from 18.2% in 1963 to 22% in 1971 and then again to 27% in 1975 (Powell, Citation1980). By 1977, the proportion of adolescents giving birth was estimated at 31% and some of the documented risk factors included limited/lack of adolescents’ access to contraception and information and education on pregnancy prevention, and gender norms that disadvantaged girls and young women. Where the male/boy responsible for paternity was in school, they remained while the girl was expected to drop out (McNeil, Citation2002).

Even though there was no explicit policy that barred adolescent mothers from returning to school at the time WCJF was founded, social taboos and unwritten policies made it difficult for adolescent mothers to reenter schools after giving birth. For instance, the Government of Jamaica, Citation1980 Education Act of Jamaica (Government of Jamaica, Citation1980) authorized public school principals to expel pregnant girls, and it conditioned reentry on approval from the Minister of Education. Unfortunately, with no Ministerial policy framework to actualize this, prospects of reentry to public education institutions dimmed for many adolescent mothers (Ministry of Education, Citation2013). This was the vacuum the WCJF aimed to fill through its PAM.

Women’s Center of Jamaica Foundation and the Programme for Adolescent Mothers

As noted above, Jamaica experienced a high adolescent pregnancy rate in the 1970s compared to other nations in the Caribbean (Powell, Citation1980). Alarmed by this, the Churches’ Advisory Bureau of Jamaica raised the matter with the Bureau of Women’s Affairs (BWA) and discussed the need for remedial interventions (McNeil et al., Citation1983). In response, the BWA established a Special Committee on Adolescent Fertility to coordinate government and non-governmental efforts in addressing adolescent childbearing (Powell, Citation1980). In 1978, the WCJF was founded with seed funding from the Pathfinder Fund, the International Planned Parenthood Federation (IPPF) and in-kind support from the Government of Jamaica (GoJ) (McNeil et al., Citation1983).

Upon being established, the WCJF initiated an ambitious intervention, called the PAM, to provide opportunities for pregnant adolescents to continue their education while pregnant and to reenter school after giving birth. Complementary activities included family planning and contraceptive services (to minimize the risk of rapid repeat pregnancy) and life and skills counseling (including on parenting skills, self-esteem and overcoming social stigma and discrimination) to girls, their families, and the fathers of the girls’ children (commonly referred to as ‘baby fathers’ in Jamaica).

While the GoJ played an important role in the initiation of the PAM through BWA/WCJF, it did not directly contribute funding for the first two years. However, the GoJ pledged to fund a substantial proportion of WCJF’s budget (e.g., salaries, wages, and utilities) on the condition that the concept/pilot showed promise in its first two years of implementation. This commitment was fulfilled by the GoJ in January 1980 based on a favorable evaluation report (Powell, Citation1980). That same year, the Swedish Development Authority also provided funds to support the implementation of the PAM for three years (McNeil et al., Citation1983).

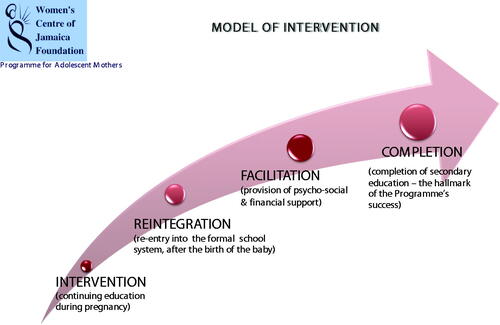

With a combination of government and external donor support, the WCJF has scaled up the PAM to 10 centers and 8 outreach stations spread across the 14 parishes of Jamaica by 2018. To promote the PAM’s sustainability, the WCJF worked closely with agencies of the GoJ (e.g., Ministry of Education (MoE), National Family Planning Board and several NGOs (e.g., Jamaica Family Planning Association) to deliver the package of intervention. The PAM interventions—broadly comprising continuing education, reintegration, facilitation, and completion (see ).

Methods

Data collection

The paper draws on diverse data and information sources to answer each of the four research questions i.e., factors that informed PAM’s conceptualization, the evidence on the effectiveness of the programme, what factors led to national scale-up and what factors have contributed to the sustainability of the program. While the four research questions are addressed with a complementary collection of documents, there are some specificities in respect of the documentation for each research question. The question on circumstances/contextual drivers of the PAM initiative is addressed with published—primarily journal articles and dissertations that describe the social and cultural state of Jamaica prior to the establishment of WCJF and more specifically adolescent sexual and reproductive health and wellbeing. Excerpts are also drawn from the biography of the first director of the WCJF. The second question draws extensively from programme evaluation reports commissioned by WCJF as well as those initiated by external funders (see ). For the third question, we rely on a series of formal and informal discussions/interviews with former and current staff of the Center, and programme reports. The final question draws inferences from the synthesis of evidence around the first three questions.

Table 1. Documents from which information was sought.

Data analysis

To answer the research questions, this paper is organized around the WHO ExpandNet Framework (World Health Organization, Citation2011) and the political prioritization schema of Shiffman (Citation2007). Even though the conceptualization, development, and scale-up of the PAM were not guided by WHO’s ExpandNet and Shiffman’s propositions, they serve as useful organizing frameworks for our analysis of WCJF’s PAM.

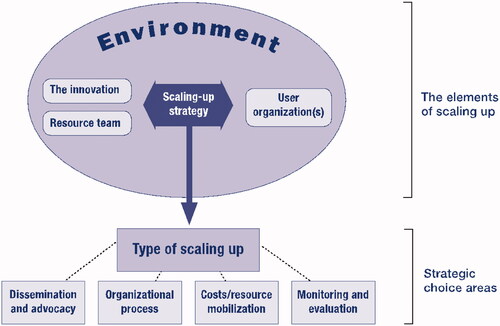

The ExpandNet Framework (see ) was designed to guide the planning, management, and evaluation of scaling up processes, particularly for sexual and reproductive health (SRH) interventions, and can be used by programme managers, researchers, and technical support agencies. It has been applied in diverse contexts to evaluate other programmes to address the SRH needs of adolescents (see, for instance, Huaynoca et al., Citation2014; Kempers et al., Citation2015; Svanemyr et al., Citation2015; Chandra-Mouli et al., Citation2018). There are three complementary dimensions in the framework: planning for scale-up (which comprises the innovation, resource team, the user organization(s) and the larger social, political, economic and institutional environments), the strategic choice areas for scaling up, and considerations for managing scale-up (which includes dissemination and advocacy, organizational processes, cost/resource mobilization and/or monitoring and evaluation) (World Health Organization, Citation2011).

The Shiffman (Citation2007) political prioritization schema outlines three criteria for judging political commitment to a problem. Originally proposed for studying prioritization of attention to and action on maternal mortality, it sets out an operational definition for political prioritization and what it took—in the countries Shiffman studied—to build it: (i) national political leaders publicly and privately express sustained concern for the issue; (ii) the government, through an authoritative decision-making process enacts policies that offer widely embraced strategies to address the problem; and (iii) the government allocates and releases public budgets proportional to the magnitude of the problem.

Findings

The innovation

PAM was the innovation provided by WCJF. The PAM was designed to provide second chances to pregnant adolescents whose education had been interrupted because of pregnancy and to facilitate reentry into secondary, high, and technical schools after childbirth. The PAM also sought to build the capacity of participants with knowledge, attitudes, and skills (e.g., counseling on self-confidence and assertiveness), and to encourage the use of a contraceptive method to prevent a second unintended pregnancy and/or school dropout. Complementary to interventions to prevent second pregnancies, first pregnancy was also targeted through in-school peer counseling, in-school group counseling on adolescent pregnancy, and young men at risk, including “baby fathers.” The core elements of the PAM are shown in . The PAM was therefore a restorative platform principally for adolescent mothers who, otherwise, would have forfeited their educational aspirations due to an early—and likely unintended—pregnancy. The relevance of the intervention was clearly established based on two key observations; first, the high rates of adolescent fertility in the country meant that more teenage mothers were at high risk of incomplete secondary education given no formal policy on returning to school after childbirth. Second, the high rates of adolescent fertility posed a significant threat to human capital formation for national development. At the time, pregnant adolescents were largely “compelled” to drop out of school as a matter of social custom. In most cases, returning to school was a “privilege” rather than a right; school principals had the discretion to allow adolescent mothers to return or not. In many instances, they were refused for “fear of contagion” or perceived negative influence on the other students (McNeil et al., Citation1983; Powell, Citation1980; Powell & Jackson, Citation1979).

Table 2. Core elements of PAM.

The collaboration between state (e.g., BWA, Family Planning Board) and non-state actors (e.g., Churches Advisory Bureau, Pathfinder International, UNICEF, UNFPA, Canadian Children’s Fund, Family Planning Association of Jamaica) contributed to the PAM’s credibility. The credibility of the PAM can be attributed to several other factors as well. Firstly, the establishment of WCJF was sponsored by a central government agency—BWA. Secondly, the first wave of assessments conducted after the first year of the intervention clearly pointed to the promise of the approach; for instance, around 73% (N = 204) of registered mothers had been enrolled in secondary and vocational schools by 1979 (McNeil et al., Citation1983). Thirdly, the backing of the then First Lady Beverley Manley (1972–1980) and Portia Simpson-Miller who held different political roles (first as a Member of Parliament from 1976 and later as a cabinet Minister of Labor, Welfare and Sports; 1989–1995 and later as Prime Minister 2006–2007 & 2012–2016) from 1978 through to 2016.

The clarity of the programme packages that were offered contributed substantially to the acceptance and grounding of the PAM right at the inception. The innovation had two well-defined arms. First, PAM was anchored on providing uninterrupted education to pregnant adolescent girls and facilitating their reintegration into the school system. This was complemented with family planning counseling and services, life skills for confidence building, child-care services, and counseling for baby-fathers as well as parents of PAM beneficiaries.

Despite the clarity, there were difficulties with the installation. On one score, it remained challenging for the mass enrollment of adolescent mothers. In many instances, it was mainly pregnant mothers who met health care providers or those referred by former students and other social networks who enrolled. Another difficulty with installing the intervention, particularly continuous education for pregnant adolescents was the inability of WCJF to obtain concessions for such girls to remain in school while pregnant and their return to school after childbirth. This element of PAM was sometimes incompatible with the prevalent cultural norms in schools and the wider community, i.e., some school principals resisted and did not allow pregnant girls to stay in school and return on delivery as well. The programme component for baby-fathers was also difficult to install, partly due to laws/acts such as the Offences Against the Person Act (Cap.269) and Child Care and Protection should read Child Care and Protection Act Citation2004. Many under-age mothers were reluctant to link their partners to the programme for fear of being prosecuted on charges of carnal knowledge of a minor.

User organization

The user organization(s) comprises the institution(s) that seek to or are expected to adopt and implement the innovation on a large-scale (World Health Organization, Citation2010). The WCJF was a special-purpose vehicle sponsored by the BWA to spearhead the PAM. The WCJF was therefore the sole user organization as far as the implementation of the PAM was concerned. Nonetheless, it received support from several organizations at different times (See ). The collaboration of these agencies created an aura of credibility for the PAM to kickoff and thrive under different political actors. Again, the fact that the Churches’ Bureau had expressed concern about high adolescent pregnancy rates was important for PAM to gain attention and the interest of key constituencies. For instance, it was out of this credible perspective that St. Patrick’s Foundation—a Catholic NGO—offered its facilities in Olympic Way (a poor inner-city area in Kingston) to WCJF to provide outreach services (Barnett et al., Citation1996). The involvement of the Churches’ Bureau was particularly important given the opposition of religious bodies to sexual and reproductive health programmes for adolescents (see, for example, Defago & Faúndes, Citation2014; Di Mauro & Joffe, Citation2007).

The capacity of WCJF to implement the PAM and deliver on its offering successfully at inception was not certain, for which reason the GoJ conditioned its budgetary support on the effectiveness of the concept after the first two years of implementation. However, with close collaboration with the MoE, the Family Planning Board, and other civil society organizations such as the Family Planning Association of Jamaica, the effectiveness and the potential of the PAM was demonstrated.

The BWA as the founding agency of WCJF exhibited commitment to the PAM by seconding its own personnel, particularly, those from the gender unit to oversee the PAM. The MoE equally showed enormous commitment by facilitating the referral of a substantial number of adolescent mothers for enrollment. The Family Planning Board committed to providing family planning counseling and services to mothers prevent repeat pregnancies. As will be illustrated later, the impact of PAM in the first two years was promising because of which the GoJ fully backed the programme with annual budgetary support and remained consistently committed to PAM regardless of the party in power. The Jamaican Family Planning Association was an equally committed resource partner, which organized monthly family planning seminars from 1978 and, toward the end of 1979, hired a full-time family planning counselor for the Center (McNeil et al., Citation1983)

Resource team

Resource organizations are described as the individuals and institutions that contribute to promoting and facilitating widespread use of the innovation and they may play this role formally or informally (World Health Organization, Citation2010). The PAM rode on diverse resource teams that brought on board complementary leadership and credibility, skills, experience, resources, and stability to advance its packages. For instance, the programme benefited from a pool of experienced and credible researchers (e.g., Phillips, Citation1973; Powell, Citation1976, Citation1977, Citation1978, Citation1979) whose studies contributed to justifying the need for PAM. Once started, these experts continued to support PAM by conducting routine evaluation studies (Barnett et al., Citation1996; Chevannes, Citation1996; Drayton et al., Citation2000; Drayton et al., Citation2002; Powell, Citation1980; Powell & Jackson, Citation1979; Williams, Citation2014) at different stages of the programme. The MoE and the National Family Planning Board supported the WCJF in identifying potential participants (i.e., pregnant adolescents accessing antenatal care through its health facilities), and by providing linkages to free or subsidized contraceptive and family planning services. This was critically important as it has contributed substantially to the low rates of repeat pregnancies among the PAM students. For instance, in a 1990 evaluation applying case-control design, McNeil et al. (Citation1990) found 39% repeat pregnancy among control participants compared with average of about 12% at the Kingston and Mandeville centers. As of 2011, Simpson (Citation2011) reckoned that repeat pregnancy had remained around 2% for the last three decades among program beneficiaries. The MoE provided curriculum support and access to textbooks and teaching materials as well as pedagogical support to the WCJF. Apart from the foundational donors, UNICEF, UNFPA, USAID, AVSC International and Christian Children Fund of Canada generously provided resources to the Government of Jamaica in the late 1980s to the early 1990s (Barnett et al., Citation1996).

WCJF’s Leadership capabilities and credibility were crucial to the long-term sustainability of the PAM. At the start of PAM, even though the WCJF had not demonstrated experience in delivering similar innovation, it relied on the credibility of BWA, whose funding director was highly respected, which made international donors (e.g., IPPF and Pathfinder Fund) commit seed funding for the programme (McNeil et al., Citation1983). A medium-term (five years) financial support package from the Norwegian Red Cross was central to the Center’s accelerated expansion drive in the mid-1980s through the 1990s. Apart from these, the PAM benefited from a cadre of committed staff—both full-time, part-time, and volunteer teachers as well as other ancillary staff including, cooks, cleaners, family planning counselors and providers. A testimonial of one of the founding beneficiaries affirms this point.

Box 1 My name is (name with withheld). My journey as a teenage mother began in June 2018. I dropped out of school at age 17 in grade 10. The father of my child disappeared after hearing about my pregnancy. He said he wanted nothing to do with the child because it’s not his. My father destroyed my phone out of anger. I therefore had no way of communicating with anyone. My stepmother also stated I could not live with them, so my dad took me to live with my grandfather. I was depressed to the extent that I attempted suicide twice, but it seems God had another plan for me. I was registered in the Women’s Center Programme at the Highgate Outreach in St. Mary. I attended the Outreach Site as often as I could, despite moving from one residence to another. The Women’s Center assisted me with bus fare as well as items for my baby. After two visits to the Health Center, it was found out that I had difficulty with my pregnancy which led to an emergency C-section. After having my daughter, the Women’s Center reintegrated me at the Tacky High school to further my education. While attending high school I was paying rent as I could not return to my father’s house and there was no relative for me to live with. A relative who had recently migrated, though her herself not settled, assisted me with rent. Attending school, taking care of my daughter, and just balancing my time was a real struggle. Throughout all this time, the Women’s Center was by my side. Mrs. Campbell-Green, Counselor was my motivator. I was encouraged to apply for the A-STREAM scholarship programme and was selected. I received a Mentor who was a tower of strength to me. The scholarship I received paid for my CSEC subjects, schools supplies and transportation cost. At a point in my journey, I stopped attending school for an extended time. Mrs. McKenzie, Manager, Mrs. Campbell-Green and my Mentor visited my school and then my home in deep rural St. Mary to get me re-started on my educational journey, so I could complete high school. My Mentor told me that if I did well, I would get help from the Women’s Center to further my education which I did. I was successful in passing six subjects. I am currently studying Social Work at the Moneague College. The Women’s Center provided me with a scholarship as a high school student and continue to provide a scholarship for me as a tertiary student. I want to say thanks to everyone from the Women’s Center for their continuous help toward me.

Again, churches and church groups (e.g., Churches’ Bureau of Jamaica), major political parties and private sector players (e.g., National Commercial Bank) have been important in the scale-up and sustainability of PAM. The stability element in the PAM’s team, especially at the senior management level has been profoundly important for the scaling-up. For example, the founding director (Pamela McNeil) directed the programme for 23 years (1978–2001), followed by Beryl Weir (2001–2013) and the current one (Zoe Simpson), from 2013-present.

Policy and social environment

The environment for innovations is defined as the conditions which are external to the user organization but have considerable effects on the vision for scale-up (World Health Organization, Citation2010). With respect to PAM, three environmental enablers facilitated progress: (1) the rising adolescent fertility through much of the 1970s, (2) the emerging women’s rights movement in the 1970s and (3) GoJ’s promotion of liberal policies facilitated PAM to take-off and thrive (see ). First, at the time when the WCJF was founded, there was clear evidence of high rates of unintended pregnancy among adolescents, estimated at 30% among all adolescents in 1977 (McNeil et al., Citation1983). Second, the burgeoning local women’s movement led to the creation of new laws and social policies; further, government programmes were increasingly prioritizing the socioeconomic progress of women and girls. The creation of the Bureau of Women’s Affairs within the GoJ in 1975 was symbolic of the increased attention to the status and needs of women within Jamaican society (McNeil et al., Citation1983) Third, at the policy front, the GoJ established a liberal National Population Policy, which further elevated the emerging momentum for addressing adolescent pregnancy and childbearing. Three of the six goals in this Policy provided direct and strong support for efforts in this area, specifically: to achieve a population size of not more than 3 million; to provide high quality family planning services to all women in their reproductive years; and to increase employment opportunities (Government of Jamaica, Citation1988; United Nations Department of International Economic & Social Affairs, Citation1982).

With the financial support of the World Bank, the government also replaced its Social Well-Being Programme with a new Human Resource Development Programme in 1989, which focused on rehabilitating and improving basic social, health and education services for vulnerable youth including pregnant and adolescent mothers. Subsequently, the GoJ established the 1990–1995 Development Plan, which, unlike the previous ones, departed from an exclusive focus on export promotion and agricultural growth to a greater focus on the social dimensions of development (Planning Institute of Jamaica, Citation1991). Additionally, in 1990, a Special Projects Unit was set up at the central level to coordinate and monitor projects funded by external partners as well as the GoJ. This was intended to ensure efficiency and effectiveness in programmes and the WCJF was one of the beneficiaries of this initiative (Planning Institute of Jamaica, Citationundated).

Further developments in the policy environment in the early 2000s strengthened the space for the PAM. Under the 2004 National Youth Policy, the GoJ emphasised holistic youth development; improved the capacity of service providers to offer accessible, relevant, and quality services to young people; and the utilization of a multi-sectoral approach to youth development. In the same year (Citation2004) the Child Care and Protection Act clearly established the best interests of the child rule in all government policies and interventions. The Vision 2030 Development Plan (2009–2030) had education and human capital development as core anchors, further strengthening the policy environment for the PAM to thrive. National Policy for the Reintegration of School-Aged Mothers into the Formal System (the Reintegration Policy, hereafter) has consolidated all these policies and programmes to offer state-sanctioned mandatory reintegration for returning mothers.

Scaling-up strategy and making strategic choices

The ExpandNet Framework views scaling-up as deliberate efforts to increase the impact of successfully tested health innovations to benefit more people and foster policy and programme development on a lasting basis. Scaling-up manifests in four ways; vertical (institutionalization through policy, political, legal and budgetary changes), horizontal (expansion/replication), spontaneous and diversification (World Health Organization, Citation2010). Vertical and horizontal scaling-up are predominant in the scale up of the PAM. The supportive policy environment described above was the bedrock of PAM’s initiation and continued to evolve favorably in subsequent years. The majority funding of PAM by the GoJ was the most direct manifestation of vertical scaling-up. The level of government funding varied but has averaged about $100 m annually up to 2011 (Simpson, Citation2011) and by 2021 is estimated at $250 m per annum.

One policy change that was central to the PAM was reserving the school spaces of pregnant adolescents to enable them to return to school after giving birth. While the GoJ through the 1980 Education Act (L.N. 67/1982) (Government of Jamaica, Citation1980) allowed reentry for adolescent mothers, this required the approval of the Minister of Education. However, this remained difficult for the first 35 years of PAM (1978–2013) until the Reintegration Policy was passed in 2013. The policy now mandates reservation of places in secondary schools for adolescent mothers, and has reinforced coordination and collaboration between the WCJF and the MoE (MOE, Citation2013). The widely described success of the Policy’s implementation is partly credited to the partnership between the education ministry and the WCJF. However, not all girls are integrated; while some are constrained by the age cut off threshold for schools, others pursue vocational training and/or seek employment.

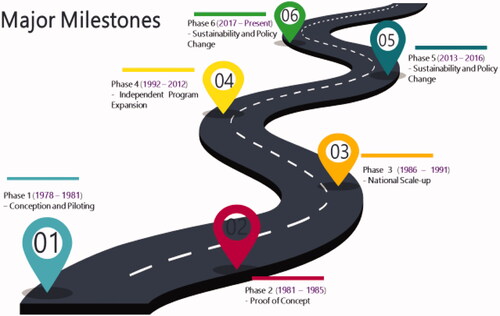

Horizontal scaling-up was deliberate and continues to evolve over the years. PAM was planned to use both government and donor funds. The programme expanded its reach to cover other parishes in Jamaica. Outreach stations were also established to reach more adolescents. The horizontal scale-up occurred in six phases (see ).

Phase 1 (1978–1981)—Conception and piloting

The BWA initiated PAM, and WCJF was the special purpose vehicle to pursue the interventions. To advance broad-based acceptance, a planning committee with membership from Ministries of Education, the Bureau of Health Education, the Department of Corrections, and the National Family Planning Board, as well as representatives of faith groups, civil society and women’s organizations was set-up. Through a series of meetings, the design and the funding modalities were discussed in detail. The Committee members also discussed and agreed on how to balance the core of WCJF’s work and their own institutional interests ().

Table 3. National policy/programme activities supporting PAM.

In the first year, WCJF relied on a manager/director, two social workers, eight volunteer part-time teachers, one health educator, and one janitor and eight-day nursery attendants seconded from the government’s Special Employment programme. At inception, there were 17 girls and by year end, 108 girls had enrolled. With the increased demand, a full-time family planning counselor and additional part-time counseling and administrative support were recruited by the WCJF. In these early years, school-age girls who dropped out of school due to pregnancy were targeted (McNeil, Citation2002). Unfortunately, resource constraints (human and financial) made it impossible to execute the skills training and job placement modules in the early years (McNeil et al., Citation1983). Later, targeted skills training programs were implemented for beneficiaries in the Kingston Center (doll making), St Margaret’s Outreach (pastry making), the Junction Outreach (basket making, garment and doll) and the Mandeville Center (cosmetology).

Phase 2 (1981–1985)—Proof of concept

As the GoJ had committed to expand and extend funding for the PAM if its concept proved successful, an external evaluation was carried out by Powell (Citation1980). It showed the value of the interventions. Specifically, the findings were that approximately 70% of the 1978-1980 cohort had successfully reentered secondary, high and technical schools. Similarly, more than 90% had accepted one or another form of contraceptive. However, it found that there were difficulties in placing some others in school due to the fixed academic calendar of government schools, which started in September each year (see ).

Table 4. Record of students from 1978 to 1981.

During this phase, new donors such as the Swedish International Development Agency (SIDA) and the Norwegian Red Cross and private sector companies (e.g., the National Commercial Bank) were cultivated through the support of the GoJ. Additionally, in-kind donations (e.g., materials, physical space, and volunteer time) were received from church groups.

Phase 3 (1986–1991)—National scale-up

In 1986, the Norwegian Red Cross, through a five-year funding agreement, supported the establishment of five additional centers (in St. Ann’s Bay, Montego Bay, Port Antonio, Savanna-la-Mar, and Spanish Town) (see ), bringing the total to seven centers across the country. These centers were established based on a needs assessment and sometimes based on what was feasible/doable. In terms of needs, communities with high rates of adolescent pregnancy were often targeted. In other instances, availability of physical space for setting up a center was another consideration. The National Director established relationships with residents who assisted in identifying available property, and local personnel to manage the new centers. Such staff were responsible for organizing all the logistics and startup infrastructure: usually a former school or clinic, refurbished with the capacity to provide the core elements (e.g., classroom; kitchen, private room, recreational space, and facility for vocational training—gardening and chicken-rearing). To minimize funding pressures, the national expansion drive was spaced out over the full funding period (1986–1991) of the Norwegian Red Cross grant.

Table 5. Sites of WCJF operations.

During this phase, the GoJ continued funding staff salaries, which were at par with the salaries of civil servants of the same level. The fact that many of the senior staff were initially on secondment from civil service positions helped establish a precedent for the higher-than-average pay scales for a development programme.

Phase 4 (1991–2012): Programme expansion

In 1991, the WCJF became a foundation. The move was motivated by the desire to attract donor and private funding directly and to expand the governance structures beyond the national government. An independent board of directors was created with members drawn from the parent ministry (Ministry of Labour, Welfare, and Sport) and other individuals selected because of personal expertise/influence. The Board’s mandate included fundraising, financial oversight, and programme guidance. The WCJF’s new status as a foundation, however, did not lead to loss of government funding, particularly for staff salaries. Indeed, the level of WCJF funding increased in the 1990s with a historically supportive party in power.

Under this dispensation, the WCJF expanded in two main dimensions: first, the service packages and secondly, geographical spread. About the service packages, walk-in counseling for adults who had personal challenges as part of ancillary social responsibility, and job and vocational skills support were added to the existing services. Regarding geographical spread, additional outreach sites were established and linked to centers where a full complement of services was provided. The outreach sites were, however, often temporary locations (e.g., church halls, health centers) used for meetings on an ad-hoc basis. Primarily, the outreach stations were established where pockets of adolescent mothers were identified. On many occasions, services at outreach stations were discontinued once the girls were reintegrated. The temporality of the outreach stations limited scope of services offered. For instance, the operational days at outreach stations were few compared to regular centers. This extent of inequality puts the girls who attend at the outreach stations at a disadvantage. Nonetheless, by the end of 1994, the programme had supported 16,500 adolescent mothers and the repeat pregnancy rate was estimated to be 1.4% (Barnett et al., Citation1996).

In this phase, preparatory work was also undertaken to shift national policies to guarantee the rights of pregnant adolescents to remain in school and to return to school after giving birth. In the early 2000s, the window of opportunity for these policy changes finally opened, sparked by local concerns, and reinforced by international support. The promulgation of the Child Care and Protection Act (Government of Jamaica, Citation2004) also expanded the enabling space for children’s welfare, through its emphasis on the best interests of the child, which precludes untimely termination of educational opportunities. International organizations such as UNFPA and UNICEF played instrumental roles in securing policy makers’ support for the prioritization of adolescent mothers’ reentry into schools. At the local level, in 2006, administrative data from Jamaica’s Registrar General reported that around 300 adolescents under 18 years had a second birth and this ignited national conversations on long-term opportunities for such adolescents. Also, the MoE’s strategy for providing education for Jamaican children hinged strongly on providing access to education and training for all, including all groups of young people, among whom were pregnant school-aged mothers. These developments set the stage for constituting the Reintegration Committee, set up by the MoE and WCJF with funding from UNFPA, to develop a policy to actualize the rights of adolescent mothers to return to school after giving birth (Ministry of Education, Citation2013).

Phase 5 (2013–2016): Policy change

The adoption of the National Policy for the Reintegration of School-Aged Mothers into the Formal School in 2013 marked the consummation of years of collaboration, and advocacy for the MoE to remove policy and administrative bottlenecks in reentry. The policy makes it mandatory for schools to reserve spaces for returning adolescent mothers and stipulates that the MoE’s Guidance and Counseling Unit will monitor compliance in collaboration with WCJF. WCJF was also mandated to review the academic records of reentry candidates and offer academic and social support to those facing challenges (Ministry of Education, Citation2013).

Phase 6 (2016–2018): Consolidation and maintenance

During this phase, completion of secondary school and pursuit of higher education were the focus. Also, this phase placed emphasis on mentorship, sponsorship, and scholarships to aid completion of secondary school. This focus was driven in part by the findings of Chevannes (Citation1996). A testimonial of a beneficiary of the secondary school completion and mentorship programme is highlighted in Box 1.

I clearly remember the day in 1978 when my friend introduced me to this lady who was recruiting girls who had dropped out of school because they had gotten pregnant. Her name was Mrs. Sheila Grant. At the time I was pregnant, and she said I could come to the Center to continue my education. I was shocked because at the time that was unheard of. Going back to school was the furthest thing from my mind. I remember my first day … there was about 10 of us there. Mrs. Pamela McNeil told us of the program and welcomed us with open arms. I had to take the bus to the Center every day and at times the adults would be very discriminatory. Even adults in the community would ask what the purpose is of going to school with a baby. However, the staff at the Center was kind and caring and made us feel wanted and welcome. I looked forward to the porridge in the morning for breakfast as sometimes there was none at home. The ancillary staff in the nursery were our mothers. They patiently showed us how to take care of our little ones and the counselors were patient and nonjudgmental. Mrs. McNeil always emphasized the importance of education and how we could use it to get out of the ghetto. I went back to school in September of 1979. However, in Citation1980 I became pregnant again because of the failure of the Lippes Loop with which I was fitted before being placed in school. I went back to the Center and again I was not refused. Mrs. Grant was very supportive and told me that it was not the end of the world. The Center set me on the path again by enrolling me in Vocational Training. Since then, I have not looked back. Attending classes with 2 children to take care of presented its challenges. However, I always knew that there was someone at the Center I could call and talk to when they arose. At the Vocational Center I did my secretarial subjects and completed my Certificate in Secretarial Studies. I went on to do my GCEs while taking care of my children. I have since completed my BA in Informal Education and Community Development and my master’s in public health. I am now enrolled with the University of the West Indies to do my PHD in Public Health looking at the “Ecological risk factors in unintended pregnancy among grand multiparous women in Jamaica.” I am eternally grateful to Mrs. Sheila Grant and Mrs. Pamela McNeil and the Women’s Center for the impact they have made on the life of the young girl from the inner city who thought that her life was over because of an early pregnancy. (name with withheld) MPH, Women’s Center—1st Cohort 1978

Three outreach stations have been upgraded to a Center status and since 2018, outreach stations have become permanent fixtures, operating additional days and services with a long-term goal of upgrading all outreach stations to main centers. Another focus of WCJF during this phase is expanding existing networks and courting more partners and working to tackle gender and sexual violence in collaboration with the Ministry of Justice. The Center is also partnering with the Jamaica Association for the Deaf and Jamaica Council for Persons with Disabilities to offer programme interventions to adolescent mothers with disabilities. To make social services complementary, the Center is creating a parish-level referral system to network with social programmes in support of adolescent mothers. This is being done with the Child Guidance Clinics and the Ministry of Labor and Social Security parish offices.

Scaling up strategy

The scaling up strategy refers to the plans and actions necessary to fully establish the innovation in policies, programmes, and service delivery. It further describes specific choices that must occur to strongly establish the innovation, which are dissemination and advocacy, organizational processes, resource mobilization and monitoring and evaluation (World Health Organization, Citation2010).

Dissemination and advocacy

Dissemination and advocacy were crucial to the expansion, scalability, and sustainability of WCJF. The Center relied on both personal and impersonal approaches to advocate for acceptance, support, and resources, reaching out to policy champions and gatekeepers within and outside the WCJF using multiple channels. From within, the first director—Pamela McNeil relied heavily on her rich networks within the education sector, attending several Parent-Teacher Association meetings within the Kingston area. This contributed immensely to the programme, to the extent that within six of years of WCJF, all schools in Kingston were accepting students from WCJF and were also referring their pregnant students to the organization (Barnett et al., Citation1996).

Outside the Center, individual sponsors/champions were harnessed from both the People’s National Party [PNP] (a social democratic party) and the Jamaican Labor Party [JLP) (a conservative party), the main political actors in the country. In the years preceding the passage of the reintegration policy, the published reports (evaluation and monitoring) of WCJF contributed in diverse ways to strengthen the case for the policy.

Organizational processes

The ExpandNet Framework describes organizational processes/approaches as involving the decisions on scope of scale-up, pace, number of agencies involved, adaptive or fixed process, centralized or decentralized and participatory or donor-expert led (World Health Organization, Citation2010). Aspects of these elements are observable in the processes applied in PAM. For instance, from 1978 to 1986, the Center operated only two centers in Kingston and Mandeville. This was not deliberate but largely due to funding constraints. With increased funding made available by the Norwegian Red Cross in 1986, five new centers (Montego Bay, Port Antonio, Savanna-la mar, Spanish Town, and St. Ann’s Bay) were established in other parishes of Jamaica. Both centralized and decentralized mechanisms were used to manage all project sites; while centers reported to the head office in Kingston, outreach stations reported to the immediate centers in their parishes. Centers and outreach stations had, and continue to have, the independence to adapt the timetable for activities, resource persons, topics for motivational sessions (depending on interests of students and availability of local resource persons) and vocational areas. However, the key offerings of PAM are provided in the national coordinating office.

Resource mobilization

The long-term vision of national scale-up was planned and executed while the WCJF was under the auspices of the GoJ through the BWA. The annual budget of the WCJF was submitted to the Ministry of Finance which was defended at the annual budget hearing of the Ministry. On becoming a foundation in 1991, the WCJF continued to receive government funding, while the board sought additional funding from external donors and the private sector. The WCJF continues to be fully government funded. However, additional fundraising continues to occur to supplement its budget, primarily to meet the welfare needs (e.g., bus fares, medical bills, and school fees) of participants.

Monitoring and evaluation

The use of data was central to the work of WCJF. Monitoring and external evaluation were crucial in establishing and justifying the financial, human resource and time investments in the programme. Five major evaluations have been conducted since inception; 1979, 1980 (findings consolidated into McNeil et al., Citation1983), 1989 (not accessible) 1996 and 2014. Monitoring reports informed the preparation of annual reports which have been and continue to be tabled in parliament.

The different evaluations (See ) illustrate the positive impacts of the PAM on girls and their children and by extension the country. For instance, between 1978 and 1980, around 92% of PAM beneficiaries did not transition to second pregnancies/births. Some interviewed beneficiaries reported improved self-image (McNeil et al., Citation1983). In a tracer study in 1995/1996, a little over half (51%) of beneficiaries had not transitioned to second births and the average spacing between the first and second birth was 5.5 years (Women Center of Jamaica Foundation, Citation1995). Nonetheless, there were some challenges around better implementation of the skills training and job placement effectively. This was due to the inability of the few programme staff to juggle between the core package of the PAM (continuous education) and job placement, given limited job opportunities (McNeil et al., Citation1983).

Table 6. Findings on key PAM studies.

Economically, millions of dollar returns to individuals and savings to the health system have been documented (Williams, Citation2014). Despite these impacts, some challenges have remained. For instance, the Programme lacks comprehensive data base for effective tracking of beneficiaries (Williams, Citation2014).

Implementation challenges

The implementation and scale-up of the WCJF and the PAM faced several challenges. Firstly, the social stigma faced by adolescent mothers extended to the women and men working to address their needs, particularly in the PAM’s early years. One of the most consistent sources of backlash stemmed from schools, with principals expressing concerns about “contagion” and the “discomfort” of having pregnant adolescents or adolescent mothers around the other students. Before the passage of the National Reintegration Policy, the strategies to circumvent this opposition involved individual advocacy and persuasion of school principals to accept adolescent mothers, and seminars and workshops for principals and school counselors about the value of opportunities for adolescent mothers to reenter school.

Secondly, there was a constant struggle between balancing the growth of the programme and the capacity of the counseling staff, who were tasked not only with supporting PAM’s participants, but also doing personalized advocacy with families and parents of participants, baby-fathers, school principals, and monitoring of mothers who returned to schools.

Thirdly, the absence of robust data/records on former students has remained a major weakness of the Center. This has affected effective follow-up, particularly on the academic and career progression of beneficiaries (Williams, Citation2014).

Other challenges included re-prioritization of donor funding modalities. In navigating around some of these challenges, the WCJF deployed multiple strategies. For instance, it made strong use of evidence to continue pushing for reforms around the policy on reentry. With verifiable results, supporters and champions across the political divide, private sector, churches and church groups, and external donor agencies were nurtured for continuous support and sustainability.

Discussion

This paper reports on the study of a programme which was developed to, first, offer pregnant adolescents with education opportunities, facilitate post-childbirth school reentry opportunities, and provide family planning services to avert or minimize the risk of repeat pregnancy and ultimately to offer second chances to adolescent mothers. Ultimately, these packages of interventions were geared toward helping beneficiaries re-build their human capital through formal education and/or skills training and job placement in Jamaica. Our inquiry focused on four key questions: examine the contextual drivers leading to the design and implementation of the PAM; the effectiveness of the programme; the systems/factors that led to successful scale-up, and sustained implementation for more than three decades. On each of the primary outcome areas i.e., pre-, and post-birth continuous education and reducing risk of repeat pregnancies, the PAM demonstrates effectiveness compared to what has been achieved elsewhere. For instance, an evaluation of the Second Chance Club in South Carolina between 1994 and 1997 reported repeat births of 6% retrospectively among beneficiaries (Key et al., Citation2001). Between 2008 and 2009, Tocce et al. (Citation2012) established repeat pregnancy of around 2.7% among adolescent mothers who participated in the Colorado Adolescent Maternity Program (CAMP). Lin et al. (Citation2019), in a 2016 evaluation of the Maikuru Program in USA found approximately 17% of beneficiaries had transitioned to second birth with all beneficiaries going on to complete secondary education. With an estimated consistent 2% repeat pregnancy rate among beneficiaries of PAM for more than three decades (Simpson, Citation2011; Williams, Citation2014), it is an illustration of high level of effectiveness comparable to other interventions. The PAM has stood the past 40 years on account of framing/conceptualization that resonated with beneficiaries, local ownership, and political commitment and WCJF’s fidelity to a core package of interventions.

First, the clarity in framing/conceptualization of PAM underscored by credible indicators/evidence (McNeil et al., Citation1989) was an important catalyst for action. Shiffman (Citation2007) makes a similar observation about how the deployment of credible data in Guatemala, Honduras, India, Indonesia, and Nigeria demonstrated to policymakers the existence of a problem that required action which resulted in clear reducing maternal mortality. Again, by projecting PAM on the premise of rebuilding the human and economic capital of adolescent mothers, rather than on providing adolescent mothers with family planning per say, the programme obtained critical support from a wide range of sponsors, including churches. Subsequent, application of data in advocating for policy changes in school reentry for adolescent mothers throughout Jamaica reinvigorates the calls for deliberate investments in high quality data in sustaining interventions (Forman et al., Citation2009). Unfortunately, a recent institutional review of WCJF (Williams, Citation2014) has highlighted some gaps and challenges in the data management capacity. This is an area where investments will be needed in the short-to-medium term. The PAM has a potential of becoming a global reference for longitudinal interventions on education and health for girls. Improving robust data management systems that are capable of tracking almost every beneficiary throughout their life course is imperative.

Second, the local ownership, particularly at the national level led to political prioritization with the GoJ’s annual budget support starting in Government of Jamaica, Citation1980 (McNeil et al., Citation1983). As the WCJF funding scenarios show, different funders supported the program at different times, yet their eventual phase out did not lead to the fold up of the PAM, which is contrary to some experiences resource constrained settings where effective programs end with the exit of funders (Bennett et al., Citation2015; Swidler & Watkins, Citation2009). The work of WCJF further shows how effective programmes can attain the attention of an array of political actors, sometimes regardless of ideological differences. In the case of PAM, both the PNP and JLP that alternated political power maintained central government support. Conceptually, the elements of political prioritization Shiffman (Citation2007) proposed are evident; public and private pronouncement of political leaders on a concerning issue (active promotion and advocacy for PAM), application of state-sanctioned authority to promulgate policies and instruments (e.g., the reintegration policy) and direct financial investments (annual budget support). Similar evidence has been documented on adolescents’ health and educational programmes. For instance, Udaan—a School-Based Adolescent Education Programme in Jharkhand, India (Chandra-Mouli et al., Citation2018) was sustained for over a decade due to ownership by the local government and its education agency. In Sierra Leone (Bash-Taqi et al., Citation2020) and the United Kingdom (Hadley et al., Citation2016), national programmes and policies to reduce adolescent pregnancy benefited considerably from political commitments at the highest decision making levels.

We further note that the PAM’s sustainability can be linked to the retention of the original core batch of interventions. Milat et al. (Citation2015) have observed that even though diversification can be useful in advancing effectiveness, and scale up of interventions, retention provides stronger impacts in the long term. Also, by maintaining its long-term vision of institutionalized school reentry policy, the WCJF was able to dedicate considerable resources, including evidence generation, to back its work. While the WCJF occasionally added to their offerings or modified the methods of delivery, the devotion to the core activities helped to ensure sustainability, given that the degree of fidelity or integrity (Dusenbury et al., Citation2003) is critical to effectiveness and efficiency.

Finally, the promulgation of the Reintegration Policy which the WCJF substantially contributed to, is worth mentioning. Nonetheless, evidence from other settings show that such policies may not be enough to address the social barriers—stigmatization, discrimination, mockery and abuse of pregnant and adolescent mothers as found in Zambia (Nkwemu et al., Citation2019; Zuilkowski et al., Citation2019). While laws and policies facilitate school reentry and there is more social acceptance of this than in the past, adolescent pregnancy is still stigmatized, and young mothers are seen as failures. Continuous efforts toward addressing social norms around adolescent pregnancy will remain important to actualizing the goal of the policy. This is particularly key given the all-too-familiar backlash that liberal and egalitarian sexual and reproductive health programmes for adolescents often face in many countries around the world. Succeeding in such environments calls for early and sustained community and stakeholder engagement, trusting partnerships, clear and persuasive communication and dissemination, capacity of decision-makers and commitment of adolescent mothers (Huaynoca et al., Citation2014; Walgwe et al., Citation2016).

Conclusion

This paper describes the long term and sustained growth of an innovative programme to support adolescent mothers and their families with continuous education, health, and other social services. To the best of our knowledge, the PAM is currently perhaps the longest running intervention aimed at supporting adolescent mothers with education, health, and social services to prevent repeat pregnancies and improve on life opportunities. With adolescent births still high in several countries, particularly in low- and middle-income countries, the PAM offers an example of integrated programming for policy makers and funders to achieve improved schooling and health outcomes for adolescent mothers concurrently. While programmes to prevent adolescent births in the first instance are crucial, several obstacles make this fully difficult, which justifies such interventions regardless of adolescent pregnancy rates.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Archer, D. N., & Williams, K. S. (2005). Making America the land of second chances: Restoring socioeconomic rights for ex-offenders. NYU Review of Law & Social Change, 30, 527.

- Asheer, S., Berger, A., Meckstroth, A., Kisker, E., & Keating, B. (2014). Engaging pregnant and parenting teens: Early challenges and lessons learned from the evaluation of adolescent pregnancy prevention approaches. The Journal of Adolescent Health, 54(3 Suppl), S84–S91.

- Barnett, B., Eggleston, E., Jackson, J., & Hardee, K. (1996). Case study of the Women’s Center of Jamaica foundation program for adolescent mothers. Family Health International.

- Bash-Taqi, R., Watson, K., Akwara, E., Adebayo, E., & Chandra-Mouli, V. (2020). From commitment to implementation: Lessons learnt from the first National Strategy for the Reduction of Teenage Pregnancy in Sierra Leone. Sexual and Reproductive Health Matters, 28(1), 1818376.

- Bennett, S., Ozawa, S., Rodriguez, D., Paul, A., Singh, K., & Singh, S. (2015). Monitoring and evaluating transition and sustainability of donor-funded programs: Reflections on the Avahan experience. Evaluation and Program Planning, 52, 148–158.

- Blencowe, H., Krasevec, J., De Onis, M., Black, R. E., An, X., Stevens, G. A., Borghi, E., Hayashi, C., Estevez, D., Cegolon, L., Shiekh, S., Ponce Hardy, V., Lawn, J. E., & Cousens, S. (2019). National, regional, and worldwide estimates of low birthweight in 2015, with trends from 2000: A systematic analysis. The Lancet. Global Health, 7(7), e849–e860.

- Brown, H. N. (1999). Preventing secondary pregnancy in adolescents: a model program. Health care for women international, 20(1), 5–15.

- Caleb-Drayton, V. L. (1999). Recidivism among Jamaican teenage mothers: A historical cohort study, 1995–1998. PhD Dissertation, Loma Linda University.

- Card, J. J., & Wise, L. L. (2018). 13 Teenage mothers and teenage fathers: The impact of early childbearing on the parents’ personal and professional lives. University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Chandra-Mouli, V., Camacho, A. V., & Michaud, P.-A. (2013). WHO guidelines on preventing early pregnancy and poor reproductive outcomes among adolescents in developing countries. The Journal of Adolescent Health, 52(5), 517–522.

- Chandra-Mouli, V., Plesons, M., Barua, A., Gogoi, A., Katoch, M., Ziauddin, M., Mishra, R., Nathani, V., & Sinha, A. (2018). What did it take to scale up and sustain Udaan, a school-based adolescent education program in Jharkhand, India? American Journal of Sexuality Education, 13(2), 147–169. https://doi.org/10.1080/15546128.2018.1438949

- Chau, K., Benevides, R., Cole, C., Simon, C., Balde, A., & Tomasulo, A. (2015). Reaching first-time parents and young married women for healthy timing and spacing of pregnancies in Burkina Faso key implementation-related findings from Pathfinder International’s “Addressing the Family Planning Needs of Young Married Women and First-Time Parents Project” Washington, DC. Pathfinder International.

- Chevannes, B. (1996). The Women’s Centre of Foundation of Jamaica: An evaluation. UNICEF/UNFPA & University of the West Indies.

- Chiyota, N., & Marishane, R. (2020). Re-entry policy implementation challenges and support systems for teenage mothers in Zambian secondary schools. The Education Systems of Africa, 2020, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-43042-9_44-1

- Defago, M. A. P., & Faúndes, J. M. M. (2014). Conservative litigation against sexual and reproductive health policies in Argentina. Reproductive Health Matters, 22, 82–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0968-8080(14)44805-5

- Di Mauro, D., & Joffe, C. (2007). The religious right and the reshaping of sexual policy: An examination of reproductive rights and sexuality education. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 4(1), 67–92. https://doi.org/10.1525/srsp.2007.4.1.67

- Drayton, V. L. C., Montgomery, S. B., Modeste, N. N., & Frye-Anderson, B. A. (2002). The Health Belief Model as a predictor of repeat pregnancies among Jamaican teenage mothers. International Quarterly of Community Health Education, 21(1), 67–81. https://doi.org/10.2190/42AY-851C-PWYA-MC31

- Drayton, V., Montgomery, S., Modeste, N. N., Frye-Anderson, B., & McNeil, P. (2000). The impact of the Women’s Centre of Jamaica Foundation programme for adolescent mothers on repeat pregnancies. The West Indian Medical Journal, 49(4), 316–326.

- Dusenbury, L., Brannigan, R., Falco, M., & Hansen, W. B. (2003). A review of research on fidelity of implementation: Implications for drug abuse prevention in school settings. Health Education Research, 18(2), 237–256.

- Forman, S. G., Olin, S. S., Hoagwood, K. E., Crowe, M., & Saka, N. (2009). Evidence-based interventions in schools: Developers’ views of implementation barriers and facilitators. School Mental Health, 1(1), 26–36. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-008-9002-5

- Frederiksen, B. N., Rivera, M. I., Ahrens, K. A., Malcolm, N. M., Brittain, A. W., Rollison, J. M., & Moskosky, S. B. (2018). Clinic-based programs to prevent repeat teen pregnancy: A systematic review. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 55(5), 736–746.

- Govender, D., Naidoo, S., & Taylor, M. (2018). Scoping review of risk factors of and interventions for adolescent repeat pregnancies: A public health perspective. African Journal of Primary Health Care and Family Medicine, 10, 1–10.

- Government of Jamaica. (1980). The Education Act. In G. O. Jamaica (Ed.), L.N. 67/1982 Kingston. GoJ.

- Government of Jamaica (1988). National Population Policy, 1983. In Annual review of population law. 1988/01/01 ed. GoJ.

- Government of Jamaica. (2004). Child Care and Protection Act. In P. O. Jamaica (Ed.), Act 11 of 2004 Kingston. GoJ.

- Hadley, A., Chandra-Mouli, V., & Ingham, R. (2016). Implementing the United Kingdom Government’s 10-year teenage pregnancy strategy for England (1999–2010): Applicable lessons for other countries. The Journal of Adolescent Health, 59(1), 68–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.03.023

- Hindin, M. J., Kalamar, A. M., Thompson, T.-A., & Upadhyay, U. D. (2016). Interventions to prevent unintended and repeat pregnancy among young people in low-and middle-income countries: A systematic review of the published and gray literature. The Journal of Adolescent Health, 59(3 Suppl), S8–S15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.04.021

- Hoffman, S. D., & Maynard, R. A. (2008). Kids having kids: Economic costs & social consequences of teen pregnancy. The Urban Insitute.

- Huaynoca, S., Chandra-Mouli, V., Yaqub Jr, N., & Denno, D. M. (2014). Scaling up comprehensive sexuality education in Nigeria: From national policy to nationwide application. Sex Education, 14(2), 191–209. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681811.2013.856292

- Ingham, R. (2016). Implementing the United Kingdom Government’s 10-year teenage pregnancy strategy for England (1999e2010): Applicable lessons for other Countries. Journal of Adolescent Health, 30, 1–e7.

- Jagdeo, T. (1984). An overview of teeniage pregnanicy in the Caribbean. Teenage Pregnancy in the Carribean Western Hamisphere Region. International Planned Parenthood Federation.

- Jimenez, E. Y., Kiso, N., & Ridao-Cano, C. (2007). Never too late to learn? Investing in educational second chances for youth. Journal of International Cooperation in Education, 10, 89–100.

- Kempers, J., Ketting, E., Chandra-Mouli, V., & Raudsepp, T. (2015). The success factors of scaling-up Estonian sexual and reproductive health youth clinic network-from a grassroots initiative to a national programme 1991–2013. Reproductive Health, 12, 1–9.

- Key, J. D., Barbosa, G. A., & Owens, V. J. (2001). The Second Chance Club: Repeat adolescent pregnancy prevention with a school-based intervention. Journal of Adolescent Health, 28(3), 167–169. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1054-139X(00)00186-5

- Levine, S., Correa, C., Richman, A., & Levine, R. (1985). Are teenage mothers different? A comparison of mexican adolescent mothers and women who gave birth for the first time in their 20s? Oaxtepec Conference.

- Lin, C. J., Nowalk, M. P., Ncube, C. N., Aaraj, Y. A., Warshel, M., & South-Paul, J. E. (2019). Long-term outcomes for teen mothers who participated in a mentoring program to prevent repeat teen pregnancy. Journal of the National Medical Association, 111(3), 296–301. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnma.2018.10.014

- Mathewson, K. J., Chow, C. H., Dobson, K. G., Pope, E. I., Schmidt, L. A., & Van Lieshout, R. J. (2017). Mental health of extremely low birth weight survivors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 143(4), 347–383. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000091

- McNeil, P. (2002). As my mother taught me: The Jamaica Women’s Centre Story. Youth Support Publications.

- McNeil, P., Olafson, F., Powell, D. L., & Jackson, J. (1983). The Women’s Centre in Jamaica: An innovative project for adolescent mothers. Studies in Family Planning, 14(5), 143–149.

- McNeil, P., Shillingford, A., Rattray, M., Gribble, J., Russell-Brown, P., & Townsend, J. (1989). The effect of continuing education on teenage childbearing: The Jamaica Women’s Center: Final Report. The Population Council.

- McNeil, P., Shillingford, A., Rattray, M., Gribble, J., Russell-Brown, P., & Townsend, J. (1990). The effect of continuing education on teenage childbearing: The Jamaica Women’s Center. Final Report. The Population Council.

- Milat, A. J., Bauman, A., & Redman, S. (2015). Narrative review of models and success factors for scaling up public health interventions. Implementation Science, 10(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-015-0301-6

- Ministry of Education. (2013). National policy for the reintegration of school-aged mothers into the formal school system. G. A. C. Unit (Ed.). Ministry of Education.

- Neill, K. A. (2015). Second chances: The economic and social benefits of expanding drug diversion programs in Harris County. James A. Baker III Institute for Public Policy of Rice University.

- Nkwemu, S., Jacobs, C. N., Mweemba, O., Sharma, A., & Zulu, J. M. (2019). They say that I have lost my integrity by breaking my virginity”: Experiences of teen school going mothers in two schools in Lusaka Zambia. BMC Public Health, 19(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-6394-0

- Phillips, A. S. (1973). Adolescence in Jamaica. Macmillan International Higher Education.

- Planning Institute of Jamaica. (1991). Jamaica Five Year Development Plan 1990–1995: Education and training. Planning Institute of Jamaica.

- Planning Institute of Jamaica. (undated). Retrieved June 18, 2021, from A short timeline of the history of the Planning Institute of Jamaica.

- Powell, D., & Jackson, J. (1979). Report of the evaluation of the Women’s Centre. The Pathfinder Fund.

- Powell, D. (1977). Adolescent Pregnancy: Some Preliminary Observa tions on a Group of Urban Young Women. Kingston University of the West Indies, Department of Sociology.

- Powell, D. (1978). The social and economic consequences of adolescent fertility. Kingston Junaica Association of Social Workers.

- Powell, D. (1980). Report of the evaluation of the Women’s Centre Program for Pregnant Teenagers and Adolescent Mothers. Jamaica, Kingston University of the West Indies; 1980.

- Powell, D. L. (1976). Female labour force participation and fertility: An exploratory study of Jamaican women. Social and Economic Studies, 35, 234–258.

- Powell, D. L. (1979). Survey of Contrapective Use in Jamaica, 1979.

- Reinicke, K. (2021). “I thought, Oh shit, because I was 19.” Discourses and practices on young fatherhood in Denmark. Families, Relationships and Societies, 10(3), 463–478. https://doi.org/10.1332/204674320X15931658914802

- Salam, R. A., Das, J. K., Lassi, Z. S., & Bhutta, Z. A. (2016). Adolescent health interventions: Conclusions, evidence gaps, and research priorities. The Journal of Adolescent Health, 59(4S), S88–S92.

- Save the Children. (2020). Beyond the ABCs of FTP: A deep dive in emerging considerations for first time parents.

- Schaffer, M. A., Jost, R., Pederson, B. J., & Lair, M. (2008). Pregnancy‐free club: A strategy to prevent repeat adolescent pregnancy. Public Health Nursing, 25(4), 304–311. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1446.2008.00710.x

- Shiffman, J. (2007). Generating political priority for maternal mortality reduction in 5 developing countries. American Journal of Public Health, 97(5), 796–803.

- Simpson, Z. M. (2011). The return of teen mothers to the formal school system: Redeeming the second chance to complete secondary education. University of Sheffield.

- Stevens, J., Lutz, R., Osuagwu, N., Rotz, D., & Goesling, B. (2017). A randomized trial of motivational interviewing and facilitated contraceptive access to prevent rapid repeat pregnancy among adolescent mothers. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 217(4), e1–423. e9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2017.06.010

- Svanemyr, J., Baig, Q., & Chandra-Mouli, V. (2015). Scaling up of life skills based education in Pakistan: A case study. Sex Education, 15(3), 249–262. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681811.2014.1000454

- Swidler, A., & Watkins, S. C. (2009). “Teach a Man to Fish”: The sustainability doctrine and its social consequences. World Development, 37(7), 1182–1196. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2008.11.002

- Thwala, S. L. K., Okeke, C. I., Matse, Z., & Ugwuanyi, C. S. (2022). Teachers’ perspectives on the implementation of teenage mothers’ school re‐entry policy in Eswatini Kingdom: Implication for educational evaluators. Journal of Community Psychology, 50(2), 684–695. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.22656

- Tocce, K. M., Sheeder, J. L., & Teal, S. B. (2012). Rapid repeat pregnancy in adolescents: Do immediate postpartum contraceptive implants make a difference? American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 206(6), 481.e1–481.e7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2012.04.015

- Undie, C.-C., Birungi, H., Odwe, G., & Obare, F. (2015). Expanding access to secondary school education for teenage mothers in Kenya: A baseline study report.

- UNFPA. (2013). Motherhood in childhood: Facing the challenge of adolescent pregnancy (State of the World Population-2013). United Nations Population Fund New York.

- United Nations Department of International Economic and Social Affairs. (1982). Jamaica. Population policy compendium. 1982/03/01 ed. United Nations Fund for Population Activities.

- Walgwe, E. L., Lachance, N. T., Birungi, H., & Undie, C.-C. (2016). Kenya: Helping adolescent mothers remain in school through strengthened implementation of school re-entry policies.

- Walker, D. A., & Holtfreter, K. (2021). Teen pregnancy, depression, and substance abuse: The conditioning effect of deviant peers. Deviant Behavior, 42(3), 297–312. https://doi.org/10.1080/01639625.2019.1666610

- WHO. (2011). WHO guidelines on preventing early pregnancy and poor reproductive health outcomes among adolescents in developing countries. World Health Organization.

- Williams, C. (2014). Evaluation of the Institutional Capacity of the Women’s Centre of Jamaica Foundation. UNFPA.

- Women Centre of Jamaica Foundation (WCJF). (1995). Tracer study on ex-participants of the Women’s Centre of Jamaica Foundation (WCJF). P. McNeil (Ed.). Kingston WCJF.

- World Bank. (2006). World development report 2007: Development and the next generation. The World Bank.

- World Health Organization. (2010). Nine steps for developing a scaling-up strategy. World Health Organization.

- World Health Organization. (2011). Beginning with the end in mind: Planning pilot projects and other programmatic research for successful scaling up. WHO & ExpandNet.

- Wulf, D. (1986). Teenage pregnancy and childbearing in Latin America and the Caribbean: A landmark Conference. International Family Planning Perspectives, 12(1), 17–22. https://doi.org/10.2307/2947627

- Zuilkowski, S. S., Henning, M., Zulu, J., & Matafwali, B. (2019). Zambia’s school re-entry policy for adolescent mothers: Examining impacts beyond re-enrollment. International Journal of Educational Development, 64, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2018.11.001