Abstract

Chaperone-assisted selective autophagy (CASA) is a tension-induced degradation pathway essential for muscle maintenance. Impairment of CASA causes childhood muscle dystrophy and cardiomyopathy. However, the importance of CASA for muscle function in healthy individuals has remained elusive so far. Here we describe the impact of strength training on CASA in a group of healthy and moderately trained men. We show that strenuous resistance exercise causes an acute induction of CASA in affected muscles to degrade mechanically damaged cytoskeleton proteins. Moreover, repeated resistance exercise during 4 wk of training led to an increased expression of CASA components. In human skeletal muscle, CASA apparently acts as a central adaptation mechanism that responds to acute physical exercise and to repeated mechanical stimulation.

Muscle represents a postmitotic tissue with a high demand on protein homeostasis (proteostasis).Citation1-3 In contracting muscles force-bearing and -generating structures are constantly subjected to mechanical, heat, and oxidative stress. Accordingly, proteostasis mechanisms need to be in place for the disposal of terminally damaged proteins and for the synthesis of new components in order to maintain muscle function.Citation2-4 Chaperone-assisted selective autophagy (CASA) is of critical importance in this regard because it mediates the degradation of large cytoskeleton components damaged during contraction.Citation3,5 Impairment of CASA in flies and mice leads to muscle weakness accompanied by a rapid deterioration of cytoskeleton architecture under mechanical strain.Citation3,6 Furthermore, mutations in the CASA-inducing cochaperone BAG3 in humans are associated with severe childhood muscle dystrophy and cardiomyopathy.Citation7-9 Although the latter findings illustrate the essential role of CASA in muscle maintenance in humans, it is still unclear to what extent CASA operates in muscles of healthy individuals. By studying the impact of resistance exercise on a group of moderately trained healthy men, we show here that CASA represents a central adaptation mechanism in human skeletal muscle in response to acute and repeated mechanical stimulation by exercise.

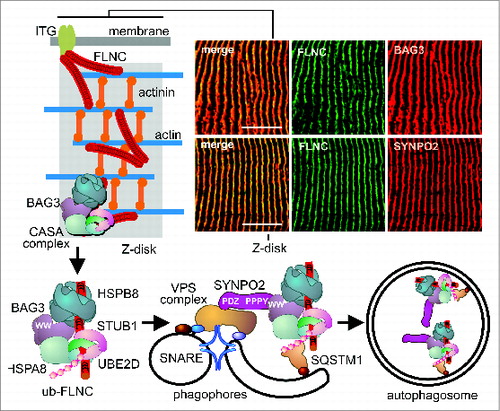

In striated skeletal muscle CASA operates at the Z-disk, a large protein assembly that mediates the anchoring of actin filaments ().Citation10 A target of CASA at the Z-disk is the actin-crosslinking protein FLNC (filamin C, gamma), which is a homodimer of ∼500 kDa consisting of 2 rod-like structures with terminal actin-binding sites ().Citation3,11 Contraction of the actin network results in the mechanical unfolding of protein domains within the filamin rods,Citation12,13 leading to recognition by the CASA chaperone complex.Citation5 The complex comprises the molecular chaperones HSPA8/HSC70 and HSPB8/HSP22, coupled by the cochaperone BAG3 that is essential for the initiation of CASA.Citation3,14,15 BAG3 cooperates with the HSPA8-associated ubiquitin ligase STUB1/CHIP and its partner UBE2D (ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2D) in the ubiquitination of chaperone-bound FLNC ().Citation3 This provides a signal for the recruitment of the autophagic ubiquitin receptor SQSTM1. During CASA BAG3 also interacts with SYNPO2, which in turn is in contact with a VPS and SNARE protein-containing, membrane-fusion machinery involved in autophagosome formation ().Citation5 Autophagosomes eventually fuse with lysosomes, where damaged FLNC is degraded. Degradation is apparently a prerequisite for the Z-disk incorporation of newly translated functional FLNC.Citation4,5 The CASA machinery thus fulfills key functions in muscle homeostasis.

Figure 1. The CASA machinery is localized at Z-disks in human skeletal muscle. Sections of resting biopsies from human vastus lateralis leg muscle were immunostained for FLNC, BAG3, and SYNPO2 (upper right panels). Schematic presentation of the CASA pathway that mediates the autophagic degradation of the actin-crosslinking protein FLNC following contraction-induced damage. Scale bars: 10 μm.

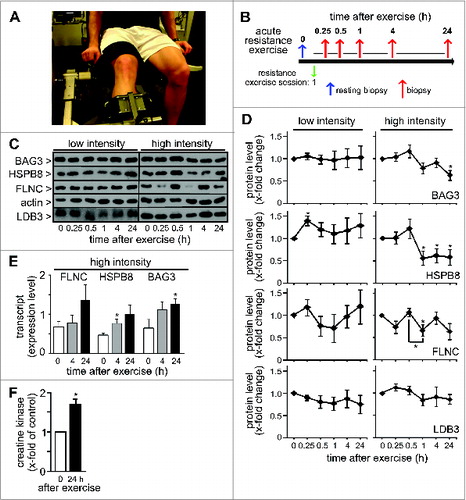

In order to assess the importance of CASA for muscle physiology under nonpathological conditions in humans, moderately trained healthy men were subjected to different resistance exercise set-ups ().Citation16 In a first set-up, the impact of a single bout of low intense or maximal eccentric resistance exercise on CASA in leg muscles was investigated (). To this end biopsies of leg vastus lateralis muscle tissue were performed before the exercise session and at 0.25, 0.5, 1, 4, and 24 h after exercise and obtained samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE, immunofluorescence, and electron microscopy.

Figure 2. Maximal eccentric resistance exercise induces CASA in human leg muscle. (A) Moderately trained healthy men were subjected to resistance exercise in a leg extension machine. (B) Impact on CASA was analyzed after a single bout of resistance exercise followed by 5 biopsies within 24 h. (C) Subjects performed low intensity concentric-eccentric resistance exercise (low intensity) or maximal eccentric resistance exercise (high intensity). Expression levels of the indicated proteins were investigated by immunoblotting. Each lane corresponds to 15 μg of protein. (D) Quantification of data obtained as described under C. Levels detected in the resting biopsies were set to 1. Mean +/− SEM, n ≥ 4, *P < 0.05. (E) Levels of FLNC, HSPB8, and BAG3 transcripts were determined by qPCR in muscle tissues of subjects before and at 4 h and 24 h after maximal eccentric resistance exercise (high intensity). Expression levels normalized to reference transcripts are shown. Mean +/− SEM, n = 5, *P < 0.05. (F) Serum CK levels were determined in the subject cohort before and 24 h after maximal eccentric resistance exercise. Levels detected in the resting biopsies were set to 1. Mean +/− SEM, n = 6, *P < 0.01.

Independent of training intensity a single bout of resistance exercise did not significantly affect the expression of LDB3/ZASP, a Z-disk protein that is neither degraded by CASA nor part of the CASA machinery (). Low intensity resistance exercise also did not cause significant changes of multiple CASA components, i.e. BAG3 and HSPB8, and the CASA substrate FLNC (). In contrast, maximal eccentric resistance exercise had a strong impact on the muscular concentration of these components. Levels of BAG3 and HSPB8, which are codegraded during CASA, were significantly reduced to 63% and 58% of the resting concentration, respectively, at 24 h after exercise (, high intensity). For the CASA substrate FLNC a statistically significant maximal reduction to 66% was observed at 60' after maximal eccentric resistance exercise. Strikingly, however, muscle concentration of FLNC showed an oscillating pattern in the wake of the acute mechanical insult (). During muscle repair disposal of damaged FLNC may therefore overlap with cycles of FLNC synthesis.

Degradation pathways other than CASA might possibly contribute to the observed reduction of protein levels. CAPN/calpain-mediated cleavage of FLNC has been observed in muscle cells,Citation17 and BAG3 might be subjected to CASP/caspase-mediated cleavage as previously revealed in nonmuscle cells.Citation18 However, the fact that multiple CASA components and the CASA substrate FLNC are similarly affected in human skeletal muscle following maximal eccentric resistance exercise argues for a dominant role of the chaperone-assisted autophagy pathway.

While FLNC, HSPB8, and BAG3 protein levels decreased after maximal eccentric resistance exercise, corresponding transcript levels did not decline, which provides further evidence for exercise-induced protein turnover (). In case of BAG3, a statistically significant 2-fold induction of transcript level was observed at 24 h after the exercise session (). This mirrors previous findings obtained with smooth muscle cells, where BAG3 transcription is activated by HSF1 (heat shock transcription factor 1) under mechanical strain.Citation5 Furthermore, HSPB8 transcript level was significantly elevated at 4 h after exercise (). Human muscle apparently responds to strenuous physical exercise with an increased expression of CASA components.

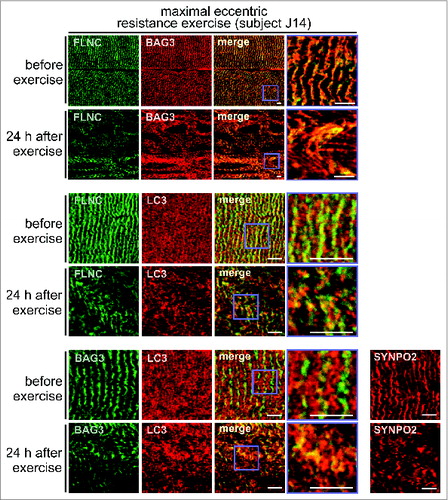

To evaluate muscle damage following exercise, we initially measured blood serum levels of CK (creatine kinase), which is almost exclusively expressed in muscle tissues and released into the circulation following exercise-induced muscle fiber disruption.Citation19 At 24 h after maximal eccentric resistance exercise, serum CK levels were indeed 1.7-fold increased, consistent with severe muscle damage (). Immunofluorescence microscopy further confirmed this. In muscle fibers of resting biopsies, a regular striated pattern was observed for FLNC and BAG3, in agreement with the colocalization of both proteins at Z-disks ().Citation3 After maximal eccentric resistance exercise, the regular striated pattern was almost completely lost with large areas of muscle fiber now showing a streaming and aggregation or vacuolization of FLNC and BAG3, apparently reflecting a mechanical induced disintegration of Z-disks and sorting of FLNC and BAG3 onto the CASA autophagy pathway (, upper panel set, Fig. S1). Next, sections were co-stained for MAP1LC3/LC3, the lipidated form (LC3-II) of which is a marker protein for autophagosome membranes. In resting muscle LC3 was diffusely distributed throughout fibers and localized mainly in small vesicles (, middle and lower panel sets). Maximal eccentric resistance exercise caused the formation of larger LC3-positive structures and increased colocalization of LC3 with FLNC (1.55-fold increase, P value: 0.012) and with BAG3 (1.54-fold increase, P value: 0.019) (, middle and lower panel sets, Fig. S2). The data are in agreement with an exercise-induced sorting of FLNC and BAG3 into autophagic structures. Finally, we also investigated the localization of SYNPO2, which cooperates with BAG3 during autophagosome formation at the Z-disk (see ). While displaying a regular striated localization in resting muscle, SYNPO2 showed a more speckled distribution in muscle fibers following maximal eccentric resistance exercise, consistent with a shift into larger protein assemblies and autophagic structures during CASA ().

Figure 3. Maximal eccentric resistance exercise causes Z-disk disintegration in human leg muscle and induces the colocalization of FLNC and BAG3 with the autophagic marker LC3. Localization of the indicated proteins in human vastus lateralis muscle fibers was performed by immunofluorescence microscopy. Scale bars: 5 μm.

Exercise-induced Z-disk disintegration and autophagosome formation was further evaluated by electron microscopy (). Resting fibers displayed a regular striated pattern of electron dense Z-disks, actin-rich A-bands, and myosin-rich M-bands. However, 24 h after maximal eccentric resistance exercise, muscle architecture was severely disturbed with Z-disks being misaligned and disrupted, and showing a high degree of vacuolization. Z-disk density was significantly reduced in this subject cohort (). Furthermore, autophagosomes were clearly detectable in mechanically stressed fibers at different stages of development as membrane enclosed vesicular structures (, lower panels).

Figure 4. Z-disk disintegration and autophagosome formation was evaluated by electron microscopy. (A) Biopsies of human vastus lateralis muscle tissue taken before and 24 h after maximal eccentric resistance exercise were analyzed. Scale bars: upper 4 panels, 1 μm; lower 2 panels, 0.5 μm. Z, Z-disk; A, A-band; M, M-band; a, autophagosome; m, mitochondrion. (B) Z-disk density was quantified following electron microscopy and showed an exercise-induced reduction. Mean +/− SEM, n = 3, *P < 0.01.

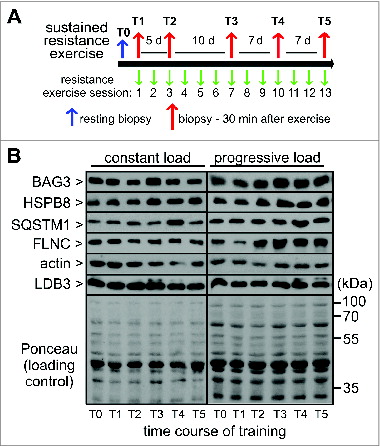

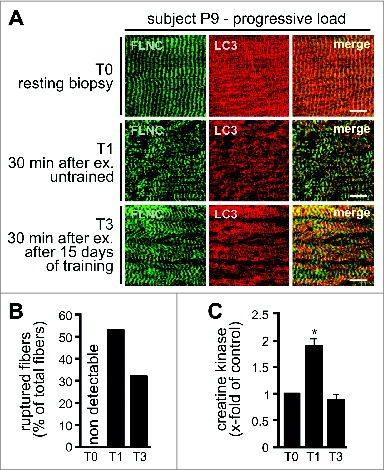

To elucidate the impact of sustained physical training on CASA, muscle biopsies were taken during 4 wk of training with 13 resistance exercise sessions (). Subjects were divided into 2 groups with either constant or progressively increasing training load during the study. Under constant load a statistically significant increase in the expression of a CASA component, i.e. HSPB8, was only observed at a single time point, T3, at 15 d of training (). In contrast, training with progressive load led to a significant increase in the muscular expression of HSPB8 (1.61-fold, SEM +/− 0.13), BAG3 (1.3-fold, SEM +/− 0.1) and the autophagic ubiquitin receptor SQSTM1 (1.5-fold, SEM +/− 0.13) becoming detectable after about 2 wk of exercise (). Moreover, force-bearing and -generating components, i.e. FLNC and actin, were also significantly upregulated in this training group. Repeated exercise with increasing mechanical load apparently induces the muscular concentration of the CASA components and the CASA target FLNC, which likely represents an adaptive mechanism to cope with increased cytoskeleton damage. Evidence for this hypothesis was obtained when we compared muscle fiber architecture 30 min after exercise in an untrained situation (T1) and after 15 d of training with progressive load (T3) of the same subject (). Fiber disintegration and rupture as well as CK release after resistance exercise was more limited after 15 d of training (, Fig. S3). During sustained training, attenuation of exercise-induced muscle damage apparently coincides with an increased expression of CASA components such as BAG3, HSPB8, and SQSTM1. Notably, BAG3 levels correlate with autophagic activity in muscle cells and other cell types.Citation3,5,14,15,Citation20-22 Induction of CASA may thus contribute to the repeated bout effect in skeletal muscle, which describes the immediate adaptation of skeletal muscle toward acute contraction-induced muscle damage and the significant reduction in muscle soreness and damage following a similar stimulation few days later.Citation23

Figure 5. Sustained resistance exercise during 4 wk of training causes alterations of the CASA machinery. (A) Schematic presentation of the training regimen. (B) Expression of the indicated proteins was analyzed by immunoblotting of biopsies taken before and during 4 wk of training with 13 resistance exercise sessions. One cohort performed the exercise with a constant weight load, while a second cohort was subjected to progressively increasing load during training. Each lane corresponds to 15 μg of protein. Shown are representative blots from individual subjects.

Figure 6. Sustained resistance exercise with progressive load leads to increased expression of CASA components and force-bearing cytoskeleton proteins. Expression levels of the indicated proteins were determined as described in and quantified. Mean +/− SEM, n ≥ 5, *P < 0.05.

Figure 7. Long-term training reduces muscle fiber damage and rupture in response to resistance exercise with progressive load. (A) Localization of the indicated proteins in human vastus lateralis muscle fibers was performed by immunofluorescence microscopy. Scale bars: 10 μm. (B) Ruptured fibers were quantified in biopsies of subject P9. Total number of analyzed fibers was set to 100% (T0: n = 90; T1: n = 142, T2: n = 109). (C) Serum CK levels were determined in the subject cohort subjected to sustained resistance exercise with progressive load. Mean +/− SEM, n = 3, *P < 0.01.

Previous studies using animal models provided evidence for exercise-induced autophagy in muscle to maintain energy and nutrient supply.Citation24-29 A prominent example is the BCL2-regulated autophagy pathway that is essential for glucose homeostasis in skeletal and cardiac muscles of mice.Citation29 It remains to be seen whether this pathway is linked to CASA, in particular because the CASA-inducing cochaperone BAG3 belongs to a family of BCL2-interacting proteins and modulates the interaction of BCL2 with BECN1.Citation30,31 Some of the effects observed here for general autophagy factors, such as LC3, may indeed be influenced by the BCL2-regulated pathway. Yet, the alterations detected for the CASA-specific components BAG3 and HSPB8 and the CASA target FLNC clearly demonstrate the induction of CASA in human muscle in response to physical exercise. Multiple lines of evidence indicate that CASA is primarily acting in protein quality control and not in nutrient homeostasis. Essential CASA components, like BAG3 and SYNPO2, are specifically localized at the Z-disk that is the force-bearing actin-anchoring structure most severely affected by mechanical stress during muscle contraction. A key target of CASA, also in human muscle, is indeed FLNC, which acts as a flexible anchor and crosslinker between actin filaments at the Z-disk and which becomes unfolded under mechanical strain, causing its recognition by the CASA machinery in the course of protein quality control.Citation4,5 We previously have shown that increasing mechanical tension within the actin cytoskeleton of isolated mouse muscles and cultured cells induces CASA activity.Citation3,5 The data presented here further extend this functional concept. Only upon maximal eccentric resistance exercise or training with progressively increasing load, was CASA activity significantly increased in muscles of the study cohorts. CASA apparently operates in healthy humans as a tension-induced proteostasis pathway essential for muscle maintenance and adaptation. So when you go to the gym, get your CASA machinery going.

Materials and Methods

Ethics statement

Participants were informed verbally and in writing of the study's purpose and the possible risks involved before providing written informed consent to participate. The study was approved by the Ethic Committee of the German Sport University Cologne in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Acute resistance exercise

Eleven moderately trained male subjects were subjected to different resistance training protocols on an isokinetic leg extension machine (Isomed 2000, D&R Ferstl GmbH, Germany). Subjects were divided into 2 groups with either maximal eccentric (n = 6, age 25 ± 7, height 183 ± 8 cm, weight: 84 ± 2 kg) or low intense concentric-eccentric resistance exercise (n = 5, age 23 ± 5, height: 181 ± 5 cm, weight: 74 ± 1 kg). Maximum eccentric resistance exercise comprised 3 sets with 8 repetitions of maximal lengthening contractions with 3 min rest between sets (100% of maximum eccentric force, range of motion 70°, angular velocity 25° per s−1, time under tension 67.2 s). Submaximal concentric-eccentric resistance exercise comprised 3 sets with 10 repetitions with 3 min rest between sets (75% of maximum concentric and eccentric force, range of motion 70°, angular velocity 65° per s−1, time under tension 66 s).

Sustained resistance exercise

Eleven moderately trained male subjects (age: 25 ± 2 y, height: 184 ± 2 cm, weight: 81 ± 7 kg) participated in a resistance exercise regimen containing 13 subsequent resistance exercise sessions in 4 wk. Prior to the study strength tests were conducted to adjust the resistance exercise load for the study so that subjects were able to perform 10 repetitions in the applied training sets (75% to 80% of maximum voluntary force). During all single resistance exercise sessions participants were subjected to 6 sets of leg resistance exercise containing 8 to 12 repetitions (3 sets leg extension followed by 3 sets of leg press with 2 min rest between each set). Each repetition followed a standardized contraction pattern consisting a sequence of 2 sec concentric, 1 sec isometric, 2 sec eccentric and 1 sec isometric contractions.

Subjects (n = 11) were divided into 2 groups conducting the sustained resistance exercise protocol with different intensities over the time course. Subjects of the constant training group (n = 5) performed all resistance exercise sessions during the study with the initial training weight to induce adaptation to initial loading conditions. In the progressive training group (n = 6) training weight was increased by 5% to enforce mechanical strain on skeletal muscle, when the subjects were able to perform more than 12 repetitions in the previous resistance exercise set. Resistance exercise was carried out using standard leg extension and leg press machines (Gym 80®, Gelsenkirchen, Germany).

Skeletal muscle biopsies

Muscle biopsies from human vastus lateralis muscle were collected in the rested state at least 72 h after the last training activity, as well as at the indicated time points after exercise. Skeletal muscle samples were freed from blood and dissected from any visible fat and connective tissue. Muscle tissue samples for western blotting and immunohistochemistry were immediately placed in cryotubes and frozen in liquid nitrogen or carefully aligned for cross-sectional analysis, embedded in tissue freezing medium, frozen in liquid nitrogen-cooled isopenthane and stored at −80°C for further analysis.

Tissue preparation

Twenty mg of muscle tissue were homogenized using a commercially available micro-dismembrator (Braun, 853062) in ice-cold lysis buffer (Cell Signaling Technology, 9803). Homogenates were incubated in lysis buffer for 45 min on ice and each 15 min vortexed for 10 sec. Samples were centrifuged at 10,000 g for 20 min at 4°C, before collecting the supernatant containing sarcoplasmic and nuclear proteins. The protein content of each sample was determined via Lowry test kits (BioRad Laboratories GmbH, 500-0113 and 500-0114). Homogenates of each subject were diluted to a protein concentration of 1.5 μg per μl homogenate.

Creatine kinase measurement

Venous blood samples were drawn by antecubital venipuncture and collected into heparinized evacuated containers. Containers were stored for 18 min at 4°C without agitation and then centrifuged at 4000 g for 12 min at 4°C. The serum supernatant was stored at −20°C and the pellet discarded. Serum creatine kinase levels were determined via photometric determination at 340 nm on a KOBAS Mira Plus chemistry analyzer (Roche GmbH, Mannheim, Germany) using N-acetylcystein stabilized CK test kits (DIALAB GmbH, D98485).

Immonofluorescence microscopy

Longitudinal cut 7 μm thick skeletal muscle cryosections of representative time points were mounted in duplicates on polylysine glass slides and stained via fluorescence immunohistochemistry for target proteins as previously described.Citation32 Cryosections were brought to room temperature (RT) and subsequently incubated for 10 min at 37°C. Sections were fixed for 8 min in −20°C precooled acetone and afterwards air-dried at RT. Sections were blocked in 5% BSA (GE Healthcare, K41-001) diluted in 0.05 M Tris-buffered saline (TBS; Merck AG, 1083821000) for 1 h at room temperature. Slides were then incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies diluted in 0.5% BSA, 0.05 M TBS (antibody dilution: anti-FLNC [customized antibody, kindly provided by Dieter Fürst] 1:100, anti-BAG3 [Proteintech, 10599-1-AP] 1:100, LC3 [Novus Biologicals, NB100-2220] 1:100, anti-SYNPO2 [customized antibody, kindly provided by Dieter Fürst, University of Bonn] 1:100). Afterwards slides were washed 6 times for 5 min in distilled water and incubated with secondary fluorescent antibodies for 1 h at RT (goat anti-mouse Alexa488 [Invitrogen, A11029; dilution 1:500] and goat anti-rabbit Alexa555 [Invitrogen, A21429; dilution 1:500]). After incubation with fluorescent antibodies double staining was conducted by washing the slides 6 times for 5 min in distilled water and blocking with 5% BSA diluted in 0.05 M TBS for 1 h at RT. Hereafter staining procedure was repeated overnight incubating with a second set of primary antibodies using the same protocol and procedures. Pictures were taken with a Zeiss confocal laser scanning microscope equipped with a Plan-Apochromat 63x/1.4 Oil DIC objective (LSM 510Meta, Zeiss, Jena, Germany).

To analyze colocalization of FLNC and BAG3 with LC3, Pearson's correlation coefficients of fluorescently stained biopsies were calculated using ImageJ Plugin JACoP. Biopsies of acute resistance exercise subject J14, before and 24 h after training, were stained against FLNC/BAG3 and LC3 respectively. Subsequently stacks of 24.4 × 24.4 μm were taken and color channels corresponding to FLNC/BAG3 and LC3 were used for Pearson's coefficient calculation. For the colocalization of FLNC and LC3, and BAG3 and LC3 prior to training, 4 and 8 stacks, respectively, were analyzed, while 14 and 13 stacks, respectively, were used to quantify colocalization 24 h after the training stimulus.

Electron microscopy

Skeletal muscle biopsies were immersion-fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 24 h. Postfixation was performed with 2% osmium tetroxide buffered at pH 7.3 with sodium cacodylate for 2 h at 4°C. Biopsies were washed, stained in 1% uranyl acetate, dehydrated through a series of graded ethanol solutions and embedded in epon resin. Semithin sections (500 μm) were cut with a glass knife on an ultramicrotome (Reichert) and stained with methylene blue. Ultrathin sections (30 to 60 nm) for electron microscopy were processed on the same microtome with a diamond knife and placed on copper grids. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) was performed using a 902A electron microscope (Zeiss, Jena, Germany).

Z-disk integrity was determined in EM pictures from subjects subjected to maximal eccentric resistance exercise (n = 3). Loss in Z-disk integrity was determined as decline in optical density of Z-lines between 0 and 24 h biopsies, quantified via standardized selection of the z-line region of sarcomeres and its subsequent assessment by optical densitometry using the software ImageJ (National Institutes of Health, USA). Optical density of single z-lines before (n = 133) and 24 h after exercise (n = 145) were quantified as gray value in 8-bit greyscale pictures (7700-fold magnification) with a line scan (50 pixels in length) along the Z-line of single sarcomeres.

Immunoblotting

SDS samples of muscle homogenates were prepared as described above. For western blot analysis of respective samples 15 μg of protein were loaded. Effects of acute resistance exercise with submaximal and maximal load were analyzed in 5 and 6 training subjects, respectively. For the analysis of sustained resistance exercise effects, biopsies of 5 subjects training under constant load as well as 6 subjects training under progressive load were analyzed. Protein levels were quantified and normalized to Ponceau S stainings of respective nitrocellulose membranes. The following antibodies were used: anti-ACTB/β-actin (Abcam, ab8224), anti-BAG3 (Proteintech, 10599-1-AP), anti-FLNC, anti-HSPB8 (R&D Systems, MAB4987), anti-LDB3 (Abcam, ab40840) and anti-SQSTM1/p62 (Progen, GP62-C).

Transcript quantification

RNA was isolated using skeletal muscle tissue samples from resting, 4 h, and 24 h biopsies from 5 subjects that were subjected to maximal eccentric resistance exercise. Approximately 5 mg of muscle tissue was homogenized and powdered in liquid-nitrogen cooled Teflon tubes with a dismembrator (Braun, 853062). RNA was isolated using the TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, 15596018) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The extracted RNA pellets were dissolved in diethyl pyrocarbonate (DEPC; Sigma, D5758-50)-treated water and stored at −80 ⁰C for further analysis. Synthesis of cDNA was performed using Superscript Vilo cDNA synthesis Kit (Invitrogen, 11754-050) using 0.75 μg of RNA per sample in an overall reaction volume of 20 μl. PCR cycling conditions were used as stated by the manufacturer. Quantitative PCR (qPCR) was performed using SsoFast EvaGreen Supermix (Bio-Rad, 172-5200) according to the instructions of the manufacturer, with transcript levels for GAPDH and B2M (β-2-microglobulin) being monitored as references. Results were quantified with Bio-Rad software CFX manager.

Nucleotide primers for qPCR (human):

B2M forw: TGTCTTTCAGCAAGGACTGG

B2M rev: GCAAGCAAGCAGAATTTGGA

BAG3 forw: GCCTGTGTACCACAAGATCC

BAG3 rev: AGTTTCTCGATGGGTCATGG

HSPB8 forw: CAGAGGAGTTGATGGTGAAGAC

HSPB8 rev: GTTGAGTAAGGAGGGACCTG

FLNC forw: ACAACCATGACTACTCCTACAC

FLNC rev: GTTCACAGAGAATGCTTGTTCC

GAPDH forw: TGAGAAGTATGACAACAGCCT

GAPDH rev: GATGATGTTCTGGAGAGC

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed on the pub-lisher's website.

1017186_supplemental_data.zip

Download Zip (1 MB)Acknowledgments

The authors thank all human subjects for excellent participation in this challenging study and all students helping in the organization of the studies.

Funding

This work was supported by the following grants: DFG SFB 635 TP8 and SFB 645 TPC6 to J.H., DFG FOR 1352 to J.H., and BISP IIA1-070112/13-14 and IIA1-070103/09-10 to S.G.

References

- Vainshtein A, Grumati P, Sandri M, Bonaldo P. Skeletal muscle, autophagy, and physical activity: the menage a trois of metabolic regulation in health and disease. J Mol Med (Berl) 2014; 92:127-37; PMID:24271008; http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00109-013-1096-z

- Banerjee A, Guttridge DC. Mechanisms for maintaining muscle. Curr Opin Support Palliative Care 2012; 6:451-6; PMID:23108340; http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/SPC.0b013e328359b681

- Arndt V, Dick N, Tawo R, Dreiseidler M, Wenzel D, Hesse M, Fürst DO, Saftig P, Saint R, Fleischmann BK, et al. Chaperone-assisted selective autophagy is essential for muscle maintenance. Curr Biol 2010; 20:143-8; PMID:20060297; http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2009.11.022

- Ulbricht A, Höhfeld J. Tension-induced autophagy - may the chaperone be with you. Autophagy 2013; 9:1-3; PMID:23518596; http://dx.doi.org/10.4161/auto.24213

- Ulbricht A, Eppler FJ, Tapia VE, van der Ven PF, Hampe N, Hersch N, Vakeel P, Stadel D, Haas A, Saftig P, et al. Cellular mechanotransduction relies on tension-induced and chaperone-assisted autophagy. Curr Biol 2013; 23:430-5; PMID:23434281; http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2013.01.064

- Homma S, Iwasaki M, Shelton GD, Engvall E, Reed JC, Takayama S. BAG3 deficiency results in fulminant myopathy and early lethality. Am J Pathol 2006; 169:761-73; PMID:16936253; http://dx.doi.org/10.2353/ajpath.2006.060250

- Arimura T, Ishikawa T, Nunoda S, Kawai S, Kimura A. Dilated cardiomyopathy-associated BAG3 mutations impair Z-disc assembly and enhance sensitivity to apoptosis in cardiomyocytes. Hum Mutat 2011; 32:1481-91; PMID:21898660; http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/humu.21603

- Selcen D, Muntoni F, Burton BK, Pegoraro E, Sewry C, Bite AV, Engel AG. Mutation in BAG3 causes severe dominant childhood muscular dystrophy. Ann Neurol 2009; 65:83-9; PMID:19085932; http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/ana.21553

- Lee HC, Cherk SW, Chan SK, Wong S, Tong TW, Ho WS, Chan AY, Lee KC, Mak CM. BAG3-related myofibrillar myopathy in a Chinese family. Clin Genet 2012; 81:394-8; PMID:21361913; http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-0004.2011.01659.x

- Small JV, Fürst DO, Thornell LE. The cytoskeletal lattice of muscle cells. Eur J Biochem 1992; 208:559-72; PMID:1396662; http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1432-1033.1992.tb17220.x

- Nakamura F, Stossel TP, Hartwig JH. The filamins: organizers of cell structure and function. Cell Adh Migr 2011; 5:160-9; PMID:21169733; http://dx.doi.org/10.4161/cam.5.2.14401

- Rognoni L, Stigler J, Pelz B, Ylanne J, Rief M. Dynamic force sensing of filamin revealed in single-molecule experiments. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2012; 109:19679-84; PMID:23150587; http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1211274109

- Lad Y, Kiema T, Jiang P, Pentikainen OT, Coles CH, Campbell ID, Calderwood DA, Ylanne J. Structure of three tandem filamin domains reveals auto-inhibition of ligand binding. Embo J 2007; 26:3993-4004; PMID:17690686; http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/sj.emboj.7601827

- Gamerdinger M, Hajieva P, Kaya AM, Wolfrum U, Hartl FU, Behl C. Protein quality control during aging involves recruitment of the macroautophagy pathway by BAG3. Embo J 2009; 28:889-901; PMID:19229298; http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/emboj.2009.29

- Carra S, Seguin SJ, Lambert H, Landry J. HspB8 chaperone activity toward poly(Q)-containing proteins depends on its association with Bag3, a stimulator of macroautophagy. J Biol Chem 2008; 283:1437-44; PMID:18006506; http://dx.doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M706304200

- Gehlert S, Suhr F, Gutsche K, Willkomm L, Kern J, Jacko D, Knicker A, Schiffer T, Wackerhage H, Bloch W. High force development augments skeletal muscle signalling in resistance exercise modes equalized for time under tension. Pflugers Arch 2014; PMID:25070178; http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00424-014-1579-y

- Raynaud F, Jond-Necand C, Marcilhac A, Furst D, Benyamin Y. Calpain 1-gamma filamin interaction in muscle cells: a possible in situ regulation by PKC-alpha. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 2006; 38:404-13; PMID:16297652; http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.biocel.2006.01.001

- Virador VM, Davidson B, Czechowicz J, Mai A, Kassis J, Kohn EC. The anti-apoptotic activity of BAG3 is restricted by caspases and the proteasome. PLoS One 2009; 4:e5136; PMID:19352495; http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0005136

- Ebbeling CB, Clarkson PM. Exercise-induced muscle damage and adaptation. Sports Med 1989; 7:207-34; PMID:2657962; http://dx.doi.org/10.2165/00007256-198907040-00001

- Liu BQ, Du ZX, Zong ZH, Li C, Li N, Zhang Q, Kong DH, Wang HQ. BAG3-dependent noncanonical autophagy induced by proteasome inhibition in HepG2 cells. Autophagy 2013; 9:905-16; PMID:23575457; http://dx.doi.org/10.4161/auto.24292

- Crippa V, Galbiati M, Boncoraglio A, Rusmini P, Onesto E, Giorgetti E, Cristofani R, Zito A, Poletti A. Motoneuronal and muscle-selective removal of ALS-related misfolded proteins. Biochem Soc Trans 2013; 41:1598-604; PMID:24256261

- Nivon M, Abou-Samra M, Richet E, Guyot B, Arrigo AP, Kretz-Remy C. NF-kappaB regulates protein quality control after heat stress through modulation of the BAG3-HspB8 complex. J Cell Sci 2012; 125:1141-51; PMID:22302993; http://dx.doi.org/10.1242/jcs.091041

- McHugh MP. Recent advances in the understanding of the repeated bout effect: the protective effect against muscle damage from a single bout of eccentric exercise. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2003; 13:88-97; PMID:12641640; http://dx.doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-0838.2003.02477.x

- Salminen A, Vihko V. Autophagic response to strenuous exercise in mouse skeletal muscle fibers. Virchows Archiv B, Cell Pathol Including Mol Pathol 1984; 45:97-106; PMID:6142562; http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF02889856

- Lira VA, Okutsu M, Zhang M, Greene NP, Laker RC, Breen DS, Hoehn KL, Yan Z. Autophagy is required for exercise training-induced skeletal muscle adaptation and improvement of physical performance. FASEB J 2013; 27:4184-93; PMID:23825228; http://dx.doi.org/10.1096/fj.13-228486

- Bayod S, Del Valle J, Pelegri C, Vilaplana J, Canudas AM, Camins A, Jimenez A, Sanchez-Roige S, Lalanza JF, Escorihuela RM, et al. Macroautophagic process was differentially modulated by long-term moderate exercise in rat brain and peripheral tissues. J Physiol Pharmacol: Off J Polish Physiol Soc 2014; 65:229-39; PMID:24781732

- Zaglia T, Milan G, Ruhs A, Franzoso M, Bertaggia E, Pianca N, Carpi A, Carullo P, Pesce P, Sacerdoti D, et al. Atrogin-1 deficiency promotes cardiomyopathy and premature death via impaired autophagy. J Clin Investigat 2014; 124:2410-24; PMID:24789905; http://dx.doi.org/10.1172/JCI66339

- He C, Sumpter R Jr, Levine B. Exercise induces autophagy in peripheral tissues and in the brain. Autophagy 2012; 8:1548-51; PMID:22892563; http://dx.doi.org/10.4161/auto.21327

- He C, Bassik MC, Moresi V, Sun K, Wei Y, Zou Z, An Z, Loh J, Fisher J, Sun Q, et al. Exercise-induced BCL2-regulated autophagy is required for muscle glucose homeostasis. Nature 2012; 481:511-5; PMID:22258505; http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature10758

- Antoku K, Maser RS, Scully WJ Jr, Delach SM, Johnson DE. Isolation of Bcl-2 binding proteins that exhibit homology with BAG-1 and suppressor of death domains protein. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2001; 286:1003-10; PMID:11527400; http://dx.doi.org/10.1006/bbrc.2001.5512

- Merabova N, Sariyer IK, Saribas AS, Knezevic T, Gordon J, Turco MC, Rosati A, Weaver M, Landry J, Khalili K. WW Domain of BAG3 is Required for the Induction of Autophagy in Glioma Cells. J Cell Physiol 2014; 230:831-41; PMID:25204229; http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/jcp.24811

- Gehlert S, Bungartz G, Willkomm L, Korkmaz Y, Pfannkuche K, Schiffer T, Bloch W, Suhr F. Intense resistance exercise induces early and transient increases in ryanodine receptor 1 phosphorylation in human skeletal muscle. PLoS One 2012; 7:e49326; PMID:23173055; http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0049326