Public child welfare (PCW) is always seen as a state concern. This Special Issue addresses child protection issues from the angle of analyzing the educational preparedness of child protection service (CPS) workers and the nation’s readiness for building a strong workforce through Title IV-E support. Its content is examined with a connection between the past as a link to the present and the future.

The past

History has set the stage for improvement. In 1961, the federal government sought to standardize support through the creation of the federal foster care system and the enactment of Title IV-E entitlement programs. Since 1980, Title IV-E has been an entitlement program for state-managed foster care or subsidized adoption (Valentine, Citation2012). Within this funding mechanism, state-university partnership has been the Title IV-E training arm aiming to increase the skill level of PCW workforce for the prevention of out-of-home placements.

Even though the funding formula for training and education has been and continues to be determined by the reimbursement rate a state can receive to provide out-of-home care for children under state custody, this rate with state variations has dropped from 70% in the 1980s to 30–50% in the recent decade. This decreasing trend has affected not only workforce planning but also Title IV-E budget on training and education (Children’s Defense Fund, Citation2018). In 1995, as a bridge to initiate a block grant concept for services, the reenactment proposal in Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act was vetoed by the President (CWLA, Citation2018). Since then, legislature has focused on how deal with PCW workforce issues, with research supporting social work education’s role (Zlotnik, Citation2003). In 2006, similar discussions about IV-E eligibility were brought back regarding the possible impact of block grants on administrative and training cost reimbursement (Whitaker & Clark, Citation2006). The history highlights the importance of education and training for improving services.

The present

Now is the time to act. The landscape of government funding has changed its direction, particularly with the recent passing of the Family First Prevention Services Act in 2018 (“Family First”) that may change and limit the service scope under Title IV-E reimbursement. Outcome evaluation is a required step in persuading legislators with evidence that educational training is an essential preventive element in combating child abuse and neglect problems.

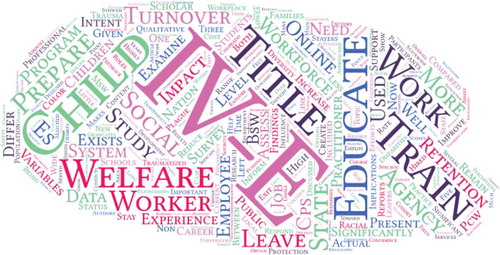

This Special Issue of the Journal of Public Child Welfare includes contributions from diverse scholars in the child welfare field who have studied the impact of Title IV-E partnerships on PCW development. Diverse themes are examined in nine refereed articles regarding Title IV-E projects’ educational principles and tested outcomes. From the abstracts of these 9 articles, a word-cloud analysis shows 10 popular words: Title IV-E (29), Educate (23), Child (23), Welfare (21), Train (17), Work (13), Workforce (11), Agency (10), Employee (9), and Retention (9). While these words connect child welfare education with workforce retention, they also specify research findings in three categories: education and training outcomes, child welfare workforce culture and environment, and retention and turnover issues.

Education and training outcomes

Strand and Popescu in their article entitled “An effective pedagogy for child welfare education” describe the intersection of social work education with child welfare. With results from 29 schools of social work, Title IV-E curriculum was tested with positive outcomes that increased workers’ confidence and preparedness to work toward improving the goals in child protection. This study can be used to advocate the inclusion of trauma-informed training so that the preventive nature of social work education can be highlighted.

The process of education and preparedness is also reported in “What’s in an MSW?” by Deglau, Akincigil, Ray, and Bauwens. These authors address the use of educational and workplace experiences to influence MSW graduates’ career aspirations for the professionalization of PCW practice. Their findings address the intentions to stay as this variable is associated with opportunities for growth and stress manageability.

Child welfare workforce culture and environment

With advances in technology, it is crucial to examine how the IV-E community will respond to the online delivery of social work education. Trujillo, Bruce, and Obermann provide a conceptual framework for analyzing an online platform for Title IV-E education in their article, “The future of online social work education and Title IV-E child welfare stipends.” The best support for students is the creation and implementation of a support network to help them balance their time while studying. Online social work programs that provide a flexible opportunity for PCW workers, particularly those working in rural counties, must also provide learning support so that they would use innovative methods for reaching out to their clientele.

Title IV-E education is designed with an aim of promoting workforce diversification. In “The role of Title IV-E education and training in child protection workforce diversification,” Piescher, LaLiberte, and Lee identify ways to reduce racial/ethnic disparities in the CPS system. Their research from a survey of 679 child welfare workers shows that children of color have been disproportionately overrepresented in the CPS, while professionals of color are disproportionately underrepresented. Having a realistic expectation of the work environment and job demand is essential to combat work-related alienation.

Turnover within PCW

With a focus on individual-system connection, Griffiths, Royse, Piescher, and LaLiberte in “Preparing child welfare practitioners” report the responses from a national sample of the Title IV-E academy. Turnover can be prevented if the workers maintain positive attitudes about their work. In “Views on workplace culture and climate,” Hermon, Biehl, and Chahla further illustrate individual differences that may lead to job factors and complex attitudes toward the workplace. Compared to Title IV-E graduates who stayed, those who left the agency had significantly lower supervisor satisfaction and worse efficacy scores; in contrast, these differences were not found among non-Title IV-E stayers and leavers. Interpreted with a positive note, these findings show that Title IV-E graduates with a high level of service satisfaction are likely to stay.

To address concerns of those who had intent to leave, Benton and Iglesias in their article, “I was prepared for the worst I guess,” address the chronic high cost of turnover. Their qualitative interviews aimed to distinguish the differences between stayers and leavers with the hope to find effective retention strategies. However, once training and payback are fulfilled, the credentials for professionalizing child welfare will become the reason and opportunity to exit the CPS workforce. From another perspective, Barbee, Rice, Antle, Henry, and Cunningham in “Factors affecting turnover rates of public child welfare front line workers” discuss the impact of constant high turnover. While most impact studies in the literature have focused on the workers’ intent to leave, these authors address the importance of studying the actual exit.

In a longitudinal study, “IV-E or not IV-E,” Slater, O’Neill, and McGuire examined the effectiveness of training on BSW IV-E scholars (n = 52) as compared with a matched cohort of traditionally trained employees (n = 57). Their results included: (1) preparedness and (2) retention in the first 5 years of employment. If IV-E education is a confidence booster, the question is no longer about retention, but instead regards leadership training.

The future

The future of Title IV-E education is based on evidence. Research evidence in this Special Issue points at the connection between social work education and PCW workforce. However, additional research is still required to identify the complexities surrounding workforce issues, particularly when child welfare workers turn to other employment after obtaining their advanced degree. These complex issues are related to workload, staff-client ratio, supervisory relationship, and other systemic barriers and motivators (Leung & Cheung, Citation2017).

According to Torres and Mathur (Citation2018), the passing of “Family First” aims at preventing children from entering foster care by allowing states to use IV-E reimbursement to pay for substance abuse, mental health, and parenting skill programs. Child welfare advocates have argued against the form of a block grant (Children’s Defense Fund, Citation2018; Harfeld, Citation2017) in anticipation that preventive service funding may not be sufficient to reach the educational needs of frontline staff (CWLA, Citation2017). In the foreseeable future, it will be more imperative than ever that the Title IV-E education partnership programs justify continued federal support, showing effective outcomes to prevent or reduce congregate placements and improve child and family well-being.

Outcome evaluation is crucial to support educational work as preventive. Although this Special Issue contains diverse topics on Title IV-E stipend students’ learning outcomes and retention within CPS, no studies were submitted concerning how to use research data to testify. One important finding, however, as related to the turnover cost and retention capacities of CPS, has provided evidence about the opportunity benefit of maintaining Title IV-E education and a workforce that enjoys having a sense of belonging to work together for the welfare of children and their families. As witnessed by a CPS investigator, “The families are more open; they’re actually asking us to go back out again” (DFPS, Citation2018), it is time to use evidence to testify on behalf of our nation’s PCW workforce and our CPS families to build a network of togetherness.

References

- Child Welfare League of America. (CWLA). (2017). The danger of block grants. Retrieved from https://www.cwla.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/The-Danger-of-Block-Grants.pdf

- Child Welfare League of America. (CWLA). (2018). Could the family first act passage protect title IV-E from block grant? Retrieved from https://www.cwla.org/could-the-families-first-act-passage-protect-title-iv-e-from-block-grant/

- Children’s Defense Fund. (2018, February 19). Family First Prevention Services Act implementation timeline. Retrieved from http://www.childrensdefense.org/library/data/ffpsa-implementation.pdf

- Department of Family and Protective Services. (DFPS). (2018 April 18). DFPS on Facebook. Retrieved from https://www.dfps.state.tx.us/

- Family First Prevention Services Act, The. [“Family First”] (2018, February). Historic reforms to the child welfare system will improve outcomes for vulnerable children. Retrieved from http://fosteringchamps.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/ffpsa-short-summary.pdf

- Harfeld, A. (2017, February 1). IV-E change needed, but not in block grant form. Retrieved from https://chronicleofsocialchange.org/opinion/iv-e-change-needed-not-block-grant-form

- Leung, P., & Cheung, M. (2017). DFPS compensation assessment and employee incentives review. Retrieved from https://www.dfps.state.tx.us/About_DFPS/Reports_and_Presentations/Agencywide/documents/2017/2017-02-20_DFPS_Compensation_Assessment_Employee_Incentives_Review-Formal.pdf

- Torres, K., & Mathur, R. (2018, March 8). Fact sheet: Family First Prevention Services Act. Retrieved from https://campaignforchildren.org/resources/fact-sheet/fact-sheet-family-first-prevention-services-act/

- Valentine, C. (2012, March). Child welfare funding opportunities: Title IV-E and Medicaid. The State Policy Advocacy and Reform Center and First Focus. Retrieved from http://childwelfaresparc.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/22-Child-Welfare--Opportunities-Title-IV-E-and-Medicaid_0.pdf

- Whitaker, T., Clark, E. J. (2006). Social workers in child welfare: Ready for duty. Research on Social Work Practice, 16(4), 412–413.

- Zlotnik, J. L. (2003). The use of Title IV-E training funds for social work education: An historical perspective. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 7(1/2), 5–21. doi:10.1300/J137v07n01_02