ABSTRACT

This research explores the degree to which gender affects safety behaviors and outcomes in the fire service. Semistructured focus groups and interviews were conducted based on findings from the literature on women and gender in the fire service. Four focus groups (N = 22) and eight interviews were recorded, transcribed, and coded using NVivo 10 software. This methodology explored if female gender improves safety behaviors through (1) weighing the risks and benefits of dangerous situations, (2) focusing on biomechanics and technique, (3) asking for help, (4) being motivated to report injuries, (5) being heard by colleagues, and (6) illuminating a hostile work environment’s contribution to safety. Participants report that women have less of a “tough guy” attitude than their male colleagues and felt that deviating from the modernist American hyper-masculine norm may have a positive impact on their work practices and injury outcomes. If women in the fire service perceive risk differently than their male colleagues, perhaps strengthening efforts to recruit women and creating a culture that values their perspective will improve the occupation’s overall safety outcomes. Further research is necessary to quantify these gender differences and their relationship to safety outcomes.

Introduction

This exploratory research aims to assess the perceptions of women in the fire service regarding the way that gender affects workplace safety behaviors and injury prevention. Fire service members in this study include firefighters, paramedics, and emergency medical technicians (EMTs). Women make up 3.7% of the fire service nationally—a small fraction of which are women of color (Hulett, Bendick, Thomas, & Moccio, Citation2008). Jahnke et al. (Citation2012) explain that the fire service has the lowest rate of female participation when compared to other male-dominated, dangerous, and physically taxing jobs, including the police and the Marines. Gender and sexuality are commonly left out of occupational analysis. As Tracy and Scott (Citation2006) explain, applying gender theory to occupational analysis aids in deconstructing the social dynamics of a particular industry.

Previous research has shown that organizational safety climate is an indicator of occupational injury (Christian, Bradley, Wallace, & Burke, Citation2009). Safety climate refers to employee perceptions regarding an organization’s policies, procedures, practices, and the types of behavior that are rewarded and supported at the workplace (Schneider, Gunnarson, & Niles-Jolly, Citation1994). Climate is the measurable aspect of safety culture (Sexton et al., Citation2006). Job risk is listed as a “distal factor” in the safety climate theoretical model (Christian et al., Citation2009). Although job risk is a validated measure of safety climate and gender affects risk perception, gender has never been studied for its contributions to safety climate and therefore safety outcomes, like injuries.

What is known is that in the civilian population women have lower unintentional injury rates than men. In 2012 the National Center for Injury Prevention and Control found that the frequency of unintentional nonfatal injuries in the United States was approximately double for men (603.46/100,000) compared to women (375.49/100,000). As masculinity is socially constructed, it varies across time, place, and social groups. Kimmel (Citation1994) writes, “We come to know what it means to be a man in our culture by setting our definitions in opposition to a set of ‘others’—racial minorities, sexual minorities, and above all, women” (p. 120). Research on masculinity and health explains that American men are socialized to perpetuate the belief that they are the “stronger sex” by showcasing masculine values in regard to health behaviors.

Masculine performance in the United States is often counter to ideas of healthfulness and safety. For example, because risk aversion and seeking health care are seen as feminine, masculine performance encourages men to deny physical discomfort and avoid seeking health care to highlight their difference from women (Courtenay, Citation2000). Therefore, though men could improve their health status by taking more caution in high-risk situations and/or seeking medical attention, doing so would be accepting vulnerability that is associated with femininity. Meaning that if men are injured and seek help or health care they are failing to measure up to the belief that “real men” are brave, strong, and stoic in the face of pain (Courtenay, Citation2000).

Importance

Gender and sexuality in the fire service

Sexuality and gender shape and limit employee efforts to preserve their desired identity on and off the job (Hall, Hockey, & Robinson, Citation2007). Firefighters perpetuate their public image as hypermasculine, but this reputation is vestigial as the fire service responded to 9.5 million emergency medical service (EMS) calls in comparison to 2.5 million fire calls nationally in 2015 (FIREHOUSE, Citation2016). EMS involves not only medical treatment, but also listening and consoling patients, which are generally considered “feminine” traits. Alongside gender, other social constructions of identity such as self-reliance and working-class values can influence the fire service’s preferred depiction as strong, brave, and tough—rather than kind, empathic and nurturing.

Firefighters manage the taint associated with this “feminized care work” by relying on the occupational prestige and their public image as hypermasculine and by disproportionately promoting “masculine” heroic events like saving lives during fires (Tracy & Scott, Citation2006). Firefighters reported frustration that they were not living up to “the men they felt they could be” when they did not feel the adrenaline rush of fire calls (Hall et al., Citation2007). This desire to live up to the hypermasculine ideal of being tough and fearless is not easily achieved. Kimmel (Citation1994) writes, “masculinity must be proved, and no sooner proved that it is again questioned and must be proved again” (p. 122). This quote eludes to the firehouse culture of peer pressure in which peers monitor and regulate one another’s behaviors to maintain the hypermasculine standard. Deconstructing occupational identity is useful for this article as it has been associated with health and safety decisions, justifying unethical behavior and group motivation within workplaces (Tracy & Scott, Citation2006).

There is an understanding that firefighting culture is hypermasculine because it is a paramilitary organization. Berkman, Floren, and Willing (Citation1999) highlight that though negative aspects of the military including not questioning commands are present in the fire service, better cultural attributes like responsibility and regulating offensive conduct of its members are not. Leadership within the fire service has the opportunity to integrate this militaristic accountability into upholding antiharassment policies that stop unfair treatment of women. This is especially necessary because estimates of sexual harassment among career and volunteer female firefighters are around 85% (Berkman et al., Citation1999). The rate of reporting such harassment is less than 5% because women do not want to be further isolated or retaliated against. Due to poor policies addressing sexual harassment, women firefighters report attempting to handle the harassment themselves or by requesting transfers (Berkman et al., Citation1999).

Women in the fire service

The limited research on women firefighters has examined: best practices for management to integrate women into the fire service (Berkman et al., Citation1999), ergonomics and anthropometry for personal protective equipment (Berkman et al., Citation1999, Stirling, Citationn.d.), racialized gender discrimination in the fire service (Yoder & Aniakudo, Citation1996; Yoder & Aniakudo, Citation1997; Yoder & Berendsen, Citation2001), making fire service inclusive for women (Hulett et al., Citation2008), health of women in the fire service (Jahnke et al., Citation2012), and cancer mortality and incidence among firefighters (Daniels et al., Citation2015). Although large-scale nationwide studies are being conducted to assess the health of firefighters, female firefighters are largely excluded due to their small proportion in the occupation (Jahnke et al., Citation2012).

Best practices for management to integrate women into the fire service include creating a reporting system that addresses harassment, providing women with appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE) and creating safeguards for reproductive health of men and women firefighters (Berkman et al., Citation1999). Men and women firefighters are at risk for negative reproductive health outcomes due to the amount of toxins they are exposed to at work. One study found that 79.9% of women firefighters reported ill-fitting gear compared to 20% of men (Hulett et al., Citation2008). This is particularly dangerous as Jahnke et al. (Citation2012) report that women firefighters are more likely to smoke than women in the general public. If firefighters’ coats do not fit properly they are vulnerable to burns, if their self-contained breathing apparatus (SCBA) does not fit they are not protected from breathing in toxins. Women described having to advocate for years for proper equipment, with several buying their own after years of inadequate management response (Berkman et al., Citation1999).

Jahnke et al. (2012) found that about one fourth of female firefighters were in the range of being clinically diagnosed as depressed, a higher rate than the national average. The authors suggest that the social pressure they feel in a male-dominated field may be a contributor. Studies of race and gender in the fire service report that Black women are dually disadvantaged and must cope with the cumulative effect of race and gender. This “double jeopardy” is documented to be different than experiences of White women and Black men in the fire service. The authors found a relentless and inescapable pattern of Black women’s exclusion in the fire service. Where White women reported eventually proving themselves and achieving acceptance within their departments, many Black women were never accepted (Yoder & Aniakudo, Citation1996, Citation1997; Yoder & Berendsen, Citation2001).

The term outsiders within (Collins, Citation1986) from Black feminist theory captures how marginalized groups have a distinct ability to assess situations as they are simultaneously part of the group and disregarded by it. As a result, “outsiders within” can critique and deconstruct the status quo in a way that group insiders cannot. Women’s unique role as “outsiders within” the fire service may situate them as change agents to challenge the hypermasculine culture that values aggressive behavior over safety (Yoder & Aniakudo, Citation1997).

For instance, though women are generally smaller than men, they are capable of completing physically strenuous tasks, particularly if attention is paid to ergonomics. If fire departments used techniques that better distributed weight or exerted less energy, then firefighters of all sizes would benefit from this efficiency. These steps would not only make the fire service more inclusive for all members it could also make firefighting smarter and safer (Hulett et al., Citation2008).

Risk perception

Researchers have established that people perceive risk differently based on their sex and race (Byrnes, Miller, & Schafer, Citation1999; Maxfield et al., Citation2010; Slovic, Citation1999), worldview (Finucane, Slovic, Mertz, Flynn, & Satterfield, Citation2000), age and health status (Harrant & Vaillant, Citation2008), and social context (Olofsson & Rashid, Citation2011). Women that self-select into occupations that cultivate a hypermasculine culture may be less risk averse than women who do not. To date, research has yet to confirm whether women in high-risk occupations are as prone to risk taking as their male colleagues (Chua, Citation2012; Hardies, Breesch, & Branson, Citation2013).

The fire service has an almost fourfold higher fatality rate than other occupations in the United States (Hulett et al., Citation2008). Risk is generally understood as part of firefighter culture, and as such firefighters are highly motivated to take risks, leading to outcomes that foster a sense of achievement, membership, and power within the crew and the general public (Fender, Citation2003). Another study found that when facing line of duty deaths, fire departments publically eulogized the fallen fighters as heroes but internally fostered a mentality that overstated personal responsibility and diminished organizational and management failures (Desmond, Citation2010).

Method

The data utilized for this exploratory project came from two data sources: one analyzing safety climate within the fire service (safety climate) and another identifying assaults in fire service nonfatal injury reporting systems (FIRST).

Participants

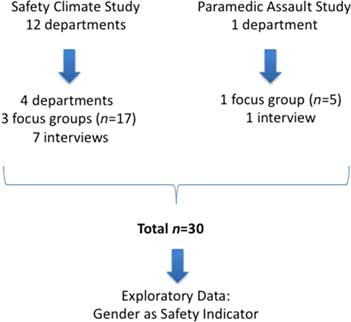

Data for this study included 30 participants from five paid municipal career fire departments located in the eastern, central, and western regions of the United States, culminating in eight interviews (n = 8) and four focus groups (n = 22) (see ). Departments were identified for inclusion in both projects based on previous collaborations and existing relationships with the investigators. Once a partner agreed to participate, the investigators worked with department leadership to recruit participants. In some cases leaders reached out to participants directly, and in others they gave the investigators contact information for participants. To control for anonymity or appearance of coercion, leadership did not participate in focus groups. Members of the department were identified to participate in focus groups and interviews according to the eligibility criteria provided by the investigators. Inclusion criteria for focus group participants was (1) that they were female firefighters or paramedics that had been (2) working in the fire service for at least 1 year and (3) were at least age 18 years. From the Safety Climate data, three focus groups consisting of career rank-and-file women firefighters were included. These three focus groups were conducted in two fire departments identified as having greater women firefighter representation. Two focus groups were conducted in one of these departments, and one focus group was conducted in the other department. From the FIRST study, one focus group consisting of women paramedics was included in this analysis. Women in this focus group had experienced a patient-initiated assault injury. All focus groups lasted approximately 1½ hours.

Department leadership, regardless of gender, also participated in this study to capture perspectives from decision makers at departments with greater women’s participation. Although these interviews were not meant to be exhaustive or representative, investigators felt the leadership perspective was important to include. Particular interviews were selected for inclusion in this study based on whether the participant was a woman in the fire service or if the interviewee was a male leader in a fire department that had a stated emphasis on gender diversity. Interviews included two women in leadership, two men in leadership, three women rank-and-file firefighters, and one woman paramedic. Interview participants were from all five of this study’s departments and lasted approximately 60 minutes. The criteria for leadership interviews were (1) female or male, (2) in a leadership position, (3) has been in that position for at least 1 year, and (4) at least age 18 years. Informed consent was obtained from all participants and the Drexel University Institutional Review Board approved the interview and focus group procedures.

Data collection

The interview and focus group guides included open-ended questions that prompted information about women’s experiences in the fire service. Both guides were informed by an in-depth literature review of women and gender in the fire service.

Focus groups and interviews covered topics such as the relationship of gender to job risk, safety outcomes, and the work environment. All interviews and focus groups were audio-recorded and transcribed by an external agency. All identifying information was redacted. Participants quoted within this article have been assigned pseudonyms and their length of experience has been categorized to preserve their anonymity and uphold the confidentiality of their viewpoints.

Data analysis

The redacted transcripts were analyzed using QSR NVivo 10 software (QSR International, Citation2012). Three investigators collaborated to create a 33-node coding structure used to organize and analyze themes. Themes were identified in the data through a close reading of the transcripts by all authors. Once the final codebook was established, YK coded all transcripts and ALD coded 30% of the transcripts. The percent agreement between YK and ALD was 98.49%. After coding was completed within the 33-node coding structure, axial coding was then used to identify the six most salient themes.

Results

Interview themes

Focus group and interview participants offered a variety of perceptions about how gender did or did not affect the culture of their fire departments. Some participants felt that being a woman shaped the majority of their interactions within the department. Others preferred not to focus on differences as they felt doing so would create divisions in a field where teamwork is essential for safety. Despite this, all participants stressed a hypermasculine culture through various references to firefighters not wanting to appear weak.

Several themes emerged from the participant responses; overall participants felt that women are less likely to have aggressive attitudes than their male colleagues. Female gender may improve safety behaviors through (1) weighing the risks and benefits of dangerous situations, (2) focusing on biomechanics and technique, (3) asking for help, (4) being motivated to report injuries, (5) being heard by colleagues, and (6) illuminating a hostile work environment’s contribution to safety.

Weighing risks and benefits

A majority of participants noted that while firefighting is a dangerous job there are many precautions that enable safer work practices. Many participants described weighing risks and benefits as a safety technique, albeit an unpopular one. Women firefighters expressed that their male colleagues often equated the success of firefighters with their willingness to take risks and were frustrated when safety interfered. Several participants expounded by saying that the thrill and danger of being inside a fire is what attracted many male firefighters into the service. Participants explained that since thinking about consequences diminishes the excitement of risk taking, aggressive firefighters are not likely to do so.

A veteran firefighter in leadership described a scenario where she was determining the course of action for a particular property fire, meaning there were not people inside, and the crew was not making much progress against the fire. She instructed the crew to leave the building and faced severe opposition from her crew, who expected to go into the building despite there being no one to save:

The insurance company will be able to rebuild it. I can’t rebuild you. And so that cultural part, you know, hopefully everybody starts to accept that … the risk versus the gain here. I mean, we’re not making any headway, let’s just back out. It’s not working, something’s just not right, I don’t even want you to fall through the floor … for what? For a stud? It doesn’t make any sense to me. (Jessie, female in leadership, over 20 years experience, FD 2)

Men in leadership also described a culture that valued risk taking as heroic even when there was no benefit in terms of saving lives or property. This unnecessary risk taking sometimes led to serious injuries requiring medical leave or inability to return to work. One leader expressed that when firefighters believe risk taking is essential to firefighting they seek out daring stunts in lieu of following standard operating procedures:

A couple of the guys have a hard time because they like to climb on the roof … that’s been hard because it’s not macho to just kind of spray water on it [the fire] and not go in [to the burning building]. I mean, if this is a room fire, yeah, we’ll go in and we’ll take care of it, but if the whole house is going up, it’s not worth it. So – a lot of guys have a hard time. They’re like, “we’re firefighters. We’re supposed to be doing this heroic [interior attack] or [going up] on the roof.” (Michael, male in leadership, over 20 years experience, FD 1)

A number of female participants connected motherhood with an unwillingness to take unnecessary risk. They described their families as their top priority rather than needing to feel brave or tough:

I’m starting an IV and I’m five months pregnant and I’m still out [in the field]. And I said to myself, what are you doing? It’s not about you anymore. It’s about the baby, because if I poke myself, if I get sick, there’s not any medicine that I can give myself that wouldn’t terminate my child. And I think women are a little softer in that sense, especially if they have kids. (Debbie, female firefighter, over 20 years experience, FD 2)

Other participants noted that having children affects people differently. Several participants noted that as single mothers or the primary care giver for their family they prioritized their personal safety over the thrill of risk taking. The following example highlights how women without children are also invested in staying healthy:

I don’t have kids, but not only do I want to go home every night, when I retire, I want to have a retirement. And I think I’ve heard more than one guy on this job say, oh, I want to die on this job! Well, so right there, that mentality tells me they’re going to take more risks. Right there. Sometimes I think the men will see the statistics and we [women] don’t, because I hear them also say around the table, oh, we don’t live past 10 years after retirement anyway. Well, let’s change that. Women, I think, are more apt to try to do that. Men kind of get set in their ways. (Kathy, female firefighter, over 15 years experience, FD 1)

Biomechanics and technique

Many respondents described using techniques that worked with their biomechanics as critical to performing their job safely. Because women were often physically smaller than their male coworkers, they would seek out different ways to accomplish a task. Several participants felt that women firefighters were significantly more aware of biomechanics than their male colleagues:

There are smarter ways to go about doing things and I think that’s an element that we [women] add to it, because … what if you’re not 6′4″ and 225. I mean like a football team, everybody has a position and there are a variety of sizes that fit the position. (Linda, female firefighter, over 30 years experience, FD 1)

Respondents emphasized that all firefighters, regardless of sex or body size, would benefit from incorporating proper technique. Several noted that their male colleagues would just “muscle through” various jobs without considering the future impact on their bodies:

I think where we [women] benefit too is with technique because other things can be a struggle. We use better technique and a lot of guys get hurt because they just try to muscle it or god forbid that they ask somebody for help and god forbid they ask a woman to help with a ladder. So a lot of guys will just muscle things that really would be more efficient as a two-person job. And women I think are smart enough, especially once you get on [the job] long enough, maybe not when I was younger, but when you’ve been on long enough to say you know what, I need help and I’m just gonna ask for help. (Mary, female firefighter, over 15 years experience, FD 1)

Several participants gave examples of modeling different techniques and breaking through the “tough guy” attitude of relying on brute strength. In the following instance a woman firefighter who worked in the training department highlights how she explains the importance of proper technique to new recruits:

Yes, I know you’re strong…. It’s good to be strong. But why don’t you do it smarter so that when you do have a different assignment, you have some energy to do it? And they’re like, “wow, so it’s really about technique. It doesn’t have to be brute strength all the time.” (Tia, female firefighter, over 10 years experience, FD 2)

Another participant described informally reaching out to probationary firefighters to explain the importance of using biomechanics and not tiring themselves out by “muscling through” tasks:

And I’ve even stopped a couple of them and said I know that it’s easy for you to grab that ladder, or that piece of equipment and do this with it, but you’re doing it all wrong and it’s going to catch up with you. And then showing them shortcuts on some of the equipment and saying, well, why can’t you just carry this ladder like a suitcase and go … or if it’s a 35-footer and you have to move it by yourself, let it drag. Take the front half of it because you have an SCBA on. Just let it scape the ground a little bit. It’s okay. And a lot of them have – some of the probationary guys said, “I never thought about it that way.” I’m like, “The goal is to do this.” And if you work yourself to the point where by the time you go to throw this ladder then you can’t do it, then what good have you done? (Fatima, female firefighter, over 10 years experience, FD 2)

The next participant emphasized that technique is related to body size rather than sex:

Everything is technique, because what works for someone who’s taller, like going back to the ladder, the taller you are on the ladder carries, the easier it is. It isn’t even strength on the ladder. The shorter you are, it’s a different fulcrum. So I have to use a different technique from someone who’s six foot. And you just have to find out what works well for you, and that’s men or women. There are guys that aren’t that tall. So you just have to find the technique for you. (Laura, female firefighter, over 20 years experience, FD 2)

Participants reported feeling empowered by incorporating an understanding of biomechanics into their technique as it directly countered stereotypical ideas that they were unable perform physically demanding aspects of the job.

Asking for help

In our effort to understand the conditions under which women asked for help, participants offered a variety of perspectives. They explained that the culture of “machismo” in the fire service discouraged appearing weak or vulnerable, which makes asking for help socially undesirable regardless of sex. Some women participants felt that after gaining seniority on the job they would be more comfortable asking for help, whereas others explained that a woman asking for help would always reinforce the stereotype that women were incapable of performing job duties. One female participant in leadership captured how some firefighters negotiate asking for help without appearing incompetent:

Communication is – you’ll always hear in our after-action is communication can be better. It’s like that’s when I think something breaks down. When someone doesn’t feel that they have a voice, or that they don’t feel safe, because they’re going to be ridiculed. And that isn’t just a gender issue, I think in the fire service, like calling a “mayday,” I think people are afraid to admit they got themselves in a jam, and the machismo side can be just as dangerous as over here, thinking I don’t want them to know, because then they’ll think it’s because I’m a woman. (Jessie, female in leadership, over 20 years experience, FD 2)

Many participants described that it was easier for their male colleagues to ask for or accept help if a female firefighter initiated team work. Many participants described men on their crew appreciating them asking for help by calling for a “four-point,” meaning that four people are lifting the patient’s stretcher rather than two people, during EMS runs:

There is a culture of guys they don’t want to ask for help. And so, when I’m on a call, I’ll say let’s do a four-point or a four-person on this. I’ll just interject. And you could see relief on their faces. But they would never ask for it themselves … younger in my career I never would either. I would never ask for help because I didn’t want to be that girl. But now I have no problem. (Fatima, female firefighter, over 10 years experience, FD 2)

A majority of participants described how their ability to speak up around lifting depended on the context of the situation. This speaker explains that she will not accept lifting help from male colleagues in public. “I’m afraid of what it looks to the public that, ‘oh look that guy had to move in and lift that cot for that woman because she couldn’t lift it,’ when that’s not the case” (Mary, female firefighter, over 15 years experience, FD 1). Another respondent with a shoulder injury pointed out that there are often crewmembers available to help, like the driver or by calling in other employees at the station:

This person weighs over 200 pounds, get your a** on the gurney with me, and we’re gonna four-point it, or – No. Let’s wait for extra techs to come in, and help us move the patient to the hospital bed, like I didn’t the time I tore it [my shoulder]. So it’s not worth it, and most of the guys are like, “oh yeah. I have been a little sore lately, that’s probably not a bad idea” … that’s another thing, it’s “I’m tough.” That’s a lot of culture, too, that leads to the injuries, “oh I don’t need to ask for help, I can just do it.” (Tess, female firefighter, over 5 years experience, FD 3)

Motivation to report injuries

Participants explained that injury reporting was akin to asking for help in that if firefighters, regardless of sex, were comfortable asking for help they may be more likely to report an injury. Participants experienced injury reporting as difficult because it counters the “tough guy,” heroic culture. The next respondent contrasts how women differ from the cycle of masculinity and nonreporting of injuries:

… whereas men are just going to power right through it and when they get hurt, they’re going to go, I don’t want to say something because that’ll make me look weak and stupid. Whereas [women are] more like, I want to make sure I’m covered, so if I really, truly get hurt, I’m going to be taken care of. (Kathy, female firefighter, over 15 years experience, FD 2)

The consequences of not reporting an injury can be career ending as described in the following story of a firefighter that was assaulted during an EMS run. In this case, the patient punched the firefighter in the nose and the impact of the punch caused the firefighter’s head to hit a metal grate that was behind him. His female partner recounts the story:

He didn’t think it was a big deal. He just moved his nose thinking “oh, I’ll snap it back into place. I’m not reporting it.” Well, make a long story short, he had a deviated septum, which [he] had to have surgery for … now he’s suffering from seizures from hitting his head on that grate and … he hasn’t been back to work in two years all from the assault. (Alli, female paramedic, over 10 years experience, FD 5)

In the following quote a veteran female firefighter describes injury reporting as obvious and necessary despite the negative social consequences. She recalls her frustration after hurting her back at work because of how the rest of the department would react; she explains how her partner responded to her frustration:

I was airing my frustrations on the way to the hospital because, of course, if you get hurt on duty you have to go to the ER and … she’s [the speaker’s partner is] like … you’re allowed to get hurt,” I’m like, no because then all the men are going to think women are weak on in this department. It was because I knew [the men would say] “oh there [she is] running to the ER” because it would spread to the women and I was just like pissed because I hated that. (Kate, female firefighter, over 20 years experience, FD 1)

Being heard by colleagues

Rank-and-file firefighters as well as men and women in leadership roles noted the differences in how women’s concerns are received in comparison to their male colleagues. This lack of equity will diminish the potential impact that women firefighters could have disturbing the status quo of safety practices, which are reinforced by a dominant culture of hegemonic masculinity. Hegemonic masculinity is defined as actions that promote the dominant position of men over women (Connell & Messerschmidt, Citation2005). One rank-and-file firefighter said that when she speaks up her words are not as respected as those of her male colleagues, “I sometimes feel as a woman you’re b****ing. If you’re a man, you’re just being assertive and telling them what you need and I feel like that even off of this job” (Mary, female firefighter, over 15 years experience, FD 1). One leader described the moment he realized how gendered notions of authority can supersede rank within the fire service. He recounts an interaction earlier in his career with a female lieutenant about a person he described as a bigot being selected for a leadership role in their department. The woman lieutenant was unwilling to bring concerns about this inappropriate selection to the chief:

I said to her, “I can’t believe that the women on this job support her selection.” And she said, “what do you think we should do about it or what could we do about it?” And I said, “well, I think you’d go to the chief and tell her your concerns.” And she said, “you don’t get it. Our concerns are not heard unless somebody like yourself says something.” And that is in the back of my head every day, that little interaction. I said, “you know what, I get it.” Until White males in the fire service stand up and say the culture needs to be diverse, it won’t be. (Michael, male in leadership, over 20 years experience, FD 1).

The hostile work environment’s contribution to safety

Female participants reflected on aspects of the work environment that affected safety directly or indirectly. They reported that women’s concerns were not taken as seriously as their male colleagues and surmised that women’s ability to improve safety would increase by eliminating hostile work environments that discriminate against women firefighters. They explained that it only took one or two discriminatory firefighters to make the fire station a hostile place. Participants noted that though women might be socialized to be more risk averse, they may feel the need to overcompensate and outperform by taking additional risks to prove their abilities and be seen as competent and accepted by male colleagues.

A majority of participants felt that there is a double standard for women, especially when they were the first woman to join a particular fire department. As one participant said, “We’re assumed incompetent basically, inferior and incompetent” (Linda, female firefighter, over 25 years experience, FD 1). Many participants described what they called “girl drills” or extra drills that were only required for women to do, well after they had established their ability to perform the task:

How many of you guys had to do a s*** ton of ladder drills when you were first on? I know I did. I mean, it was – there was a certain station that I went to that every time I went there, I knew that I was going to have to do ladder drills, because it’s one of the heavier things.… And so me, because I knew this captain for the f***ing 15th time has given me this drill, I would say, oh, this is so easy. It’s just like carrying a purse, because I’d put it on my other arm. (Fatima, female firefighter, over 10 years experience, FD 2)

Participants with seniority described past instances of dangerous and blatant discrimination:

They weren’t turning off other people’s air packs going into practice drills, but they were turning my air pack off, to see if I knew what to do. As soon as I proved myself, they backed off, you know, and it is a lot of proof, but … back then, I didn’t say anything. My first unit job, I had a lieutenant call me a c***, excuse my French, and that [word] just makes my hair stand up. [I] didn’t do anything about it, because I didn’t know what to do, I was brand new. What do you do? I’ve seen changes, I feel like there was a lot more, it was worse, I’m going to be honest, it [the discrimination] was worse. (Amber, female firefighter, over 20 years experience, FD 1)

In direct response to the previous participant’s comment, another participant described her unmet expectations of gender equality at their shared department, especially because she came from another department where she was the first woman hired:

I thought it would be better coming here because there [were] already men and women who had paved that path that I was paving. And I’ll be honest, it’s not. I don’t feel equal here. Maybe that’s me. I don’t feel equal even to the same people that I came out of the academy with. (Kathy, female firefighter, over 15 years experience, FD 1)

Several women participants explained that hostility took the form of sexual harassment. In the following instance a participant described how a man in leadership was sexually harassing another woman in her department:

She was put at a station with a captain and he would walk by and give her back rubs and then start playing with her hair. One night she went into the shower, and she came back, and she’s like, what the f***, and she starts going through her bag and she’s like, someone’s been in my bag. There was chocolates laid out on her underwear. (Debbie, female firefighter, over 20 years experience, FD 2)

A relatively new firefighter explained that she was forced to leave her previous department because of discrimination. She explained that although her colleagues treated her like an equal, leadership was openly hostile toward her and expected her to accept sexual harassment:

My last straw there was a lieutenant that kept touching me and he finally slapped my butt, and the chief told me “oh, he’s just joking. You got to learn to deal with that.” That was the answer for everything … it was kind of pointless bringing stuff up, so I just learned to keep my mouth shut. But there were times I actually went home sick, crying from work, because it was ridiculous. But all the guys were really nice to me, it was just management and they have a big part in your job. (Joan, female firefighter, less than 5 years experience, FD 1)

Other participants described unclear and ineffective policies that made reporting instances of harassment more problematic. Participants described extremely stressful situations that followed reporting hostile work environment complaints. Participants reported losing sleep, having nightmares, and considering leaving the profession after complaints were mishandled. One participant described an incident where a male firefighter made a discriminatory remark and though she wanted to handle the situation on her own, a chief heard about the incident and filed a sexual harassment case on her behalf, without her consent:

Well, somehow that rumor got sent to this person, that person, that person, and a female chief heard about it. She wrote him up. And then I got a call from a deputy chief saying that they were going to get him. They heard he was a piece of s***, that they were going to hang [him] up, out to dry, and whoa, whoa, don’t have me carry your f***ing flag. No way. If he did other things, then you need to ask [about] those. Do not hang this one thing on me and my situation, because you decide that you’re on a f***ing witch hunt. And I am sorry, but I don’t think this thing warrants somebody getting fired and I’m saying this as a female. I’m like; I wasn’t stressed out, now I am stressed out, because you’ve created something that has my name attached to it.

The participant continued:

And I’m telling the chief, this is like s*** we handle on our own, because we don’t need this. And it became to where I actually had nightmares that I was going to [get someone fired]. I had nightmares about it. (Fatima, female firefighter, over 10 years experience, FD 2)

Many other participants grappled with feeling like they had a responsibility to other women firefighters to not quit in spite of discrimination. One woman in leadership described her shock at how little support she received from her department and the larger fire community after being assaulted by another firefighter on a fire scene:

My world really was rocked because I’m like how can this happen? If anybody knows the system [I do], if they can do this to me, they can do it to anybody. And I’m just torn. I’m just torn, part of me is like I just want out, and life is too short for this. But part of me also felt the responsibility that then what? They drive you off, then what happens [to other women]? (Carmen, female in leadership, over 30 years experience, FD 1)

Limitations

A methodological weakness of this project is that the subset of interview and focus groups analyzed from the Safety Climate project were conducted in two fire departments known to have more female firefighters to ensure feasibility. Women in the fire service who are serving in areas where there are more women firefighters may have a less isolated experience than women firefighters in other areas. Also, because all of the participants are still active in the fire department investigators only captured the experiences of women that have remained firefighters. The remaining three fire departments included in this analysis were more traditional in that they had a significantly larger proportion of men than women. Soliciting participation from only five departments has some inherent limitations, as women’s experiences in the fire service likely cluster within a department, however we have geographic diversity among the fire departments that allowed us to hear a diversity of opinions.

Due to the scarcity of fire departments known to have greater than average proportions of women, we had to travel significant distances to conduct interviews and focus groups. Therefore, we did not seek data saturation as a way to determine thematic rigor. Rather, participation was determined by the resources available to support travel, and the fact that this was a pilot study to understand the phenomenon of gender and safety.

We attempted to reduce investigator bias by recording all interviews and focus groups, making us less dependent on recollection and notetaking. Additionally, all transcripts were reviewed by all coauthors and finalization of the node list was reached by consensus.

Previous research has documented how women of color experience working in the fire service differently than White women. However, like the majority of firefighters in the United States, most participants of this study (N = 26) identified as White American. Future research should aim to capture the experience of women of color to provide a more complete assessment of gender and race in the fire service.

Discussion

This pilot study explored women firefighters’ perspectives on how gender affects safety. Women firefighters reported acting as change makers in terms of safety behaviors through (1) weighing the risks and benefits of dangerous situations, (2) focusing on biomechanics and technique, (3) asking for help, (4) being motivated to report injuries, (5) being heard by colleagues, and (6) illuminating a hostile work environment’s contribution to safety.

However, all participants described that women’s experiences working in the fire service are highly variable, depending on their immediate leadership, crewmates, and years of experience. Each of these factors can constrain or enhance firefighters’ ability, regardless of sex, to speak up about their safety behaviors. Participants reported that despite progress made to integrate women into the fire service, many are still facing discriminatory hostile work environments.

Several participants described the power of the hypermasculine culture and how it suppresses speaking up about harassment, reporting injuries, and asking for help for fear of seeming weak. The hypermasculine environment limits all firefighters’ ability to speak up and thus address safety concerns. Deconstructing this culture could challenge the idea that firefighters “should” be putting themselves in danger. Participants gave examples where standard operating guidelines like suppressing a fire from the outside are ignored for the more exciting and less safe strategy of entering the burning building. Participants explained that if there is someone to save then the risk of entering the fire is justified, but if not they fight the fire from outside. This suggests a disconnect between firefighters wanting to get inside a fire and take the associated risks and the need to do so.

If one person speaks up for safety that person is perceived as afraid, but if a department incentivized or normalized safer strategies it would avoid alienating the single firefighter. If firefighters feel more comfortable asking for help perhaps they will be less likely to over exert themselves and get hurt. If the fear of asking for help is reduced it will also be easier to report any injuries that do occur. Reporting injuries will improve their chances of being able to stay on the job and have a healthy life after retirement.

Women firefighters described many ways in which they are already disrupting the hypermasculine culture in their fire stations. One example is how they are following the ergonomic principle of fitting the job to the person, rather than adjusting the worker’s body for the task. Women firefighters are finding more efficient ways to do the same job based on height and body weight. Fire departments can document and popularize the biomechanical techniques that women firefighters are discovering and applying within their work.

Trainings can be restructured to include practice weighing risks and benefits in various situations and then how to speak up when the risk is unnecessary. Alongside stories of resistance to change, participants recounted instances where their male colleagues were open to new, safer techniques whether it was initiating teamwork to lift a heavy patient or carrying a ladder a different way to conserve energy. Recruitment can also shift to reflect the increasing percentage of EMS work in the fire service. New women and men recruits could start out with safer techniques rather than having to figure them out on their own.

Workplace harassment creates an unsafe environment for the victim(s) and detracts from the prioritization of safety as a shared value within a fire department. As outlined in the iWomen’s Managers Report (Berkman et al., Citation1999) it is every department’s legal responsibility to create a workplace free of harassment. This report emphasizes that each department should create clear, written policies prohibiting sexual discrimination and provide copies to all personnel. Additionally, departments should host antiharassment trainings that focus on disciplining the harasser rather than the victim to prevent retaliation against victims of sexual harassment. It is also important for management to be a positive and proactive example by addressing harassment swiftly and directly without punishing the reporter for speaking up.

Conclusion

Female firefighters are understudied and often left out of discussions on improving the fire service. We were unprepared for the emotional outpouring from participants as they recounted their experiences. As a result, having these conversations was in itself a palpably cathartic experience. As “outsiders within,” women firefighters offer a unique perspective that can be capitalized upon during efforts to make the fire service safer. However, until the fire service takes steps to be inclusive of women, their impact as change makers will remain severely limited.

wjwb_a_1358642_sm3807.docx

Download MS Word (17.8 KB)Additional information

Funding

References

- Berkman, B., Floren, T. M., & Willing, L. F. (1999). Many faces, one purpose: A manager’s handbook on women in firefighting (US Department of Homeland Security Rep. No. FA-196). Madison, WI. Retrieved October 10, 2013, from US Fire Administration website: https://www.usfa.fema.gov/downloads/pdf/publications/fa-196-508.pdf

- Byrnes, J. P., Miller, D. C., & Schafer, W. D. (1999). Gender differences in risk taking: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 125(3), 367–383. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.125.3.367

- Christian, M. S., Bradley, J. C., Wallace, J. C., & Burke, M. J. (2009). Workplace safety: A meta-analysis of the roles of person and situation factors. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94, 1103–1127. doi:10.1037/a0016172

- Chua, Y. T. (2012). The role of gender and risk perception among police officers general lifestyle risks and occupation-specific risks (Master’s Thesis). Retrieved from Michigan State University Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Collection. (UMI No.1531771)

- Chief and Assistant Chief Fire Officers Association. (n.d.). National Anthropometry Survey of Female Firefighters. Staffordshire, UK: Stirling, M. http://www.humanics-es.com/FireFighterAnthropometry.pdf

- Collins, P. H. (1986). Learning from the outsider within: The sociological significance of black feminist thought. Social Problems, 33(6), S14–S32. doi:10.1525/sp.1986.33.6.03a00020

- Connell, R. W., & Messerschmidt, J. W. (2005). Hegemonic masculinity: Rethinking the concept. Gender & Society, 19(6), 829–859. doi:10.1177/0891243205278639

- Courtenay, W. H. (2000). Constructions of masculinity and their influence on men’s well-being: A theory of gender and health. Social Science & Medicine, 50(10), 1385–1401. doi:10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00390-1

- Daniels, R. D., Bertke, S., Dahm, M. M., Yiin, J. H., Kubale, T. L., Hales, T. R., … Pinkerton, L. E. (2015). Exposure–response relationships for select cancer and non-cancer health outcomes in a cohort of US firefighters from San Francisco, Chicago and Philadelphia (1950–2009). Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 72(10), 699–706. doi:10.1136/oemed-2014-102671

- Desmond, M. (2010). Making firefighters deployable. Qualitative Sociology, 34(1), 59–77. doi:10.1007/s11133-010-9176-7

- Fender, D. L. (2003). Controlling risk taking among firefighters. Professional Safety, 48(7), 14–19.

- Finucane, M. L., Slovic, P., Mertz, C., Flynn, J., & Satterfield, T. A. (2000). Gender, race, and perceived risk: The ‘white male’ effect. Health, Risk & Society, 2(2), 159–172. doi:10.1080/713670162

- FIREHOUSE. (2016). 2015 National Run Survey - Part 1. FIREHOUSE. Retrieved from http://www.firehouse.com/article/12207208/2015-national-run-survey-part-1

- Hall, A., Hockey, J., & Robinson, V. (2007). Occupational cultures and the embodiment of masculinity: Hairdressing, estate agency and firefighting. Gender, Work & Organization, 14(6), 534–551. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0432.2007.00370.x

- Hardies, K., Breesch, D., & Branson, J. (2013). Gender differences in overconfidence and risk taking: Do self-selection and socialization matter? Economics Letters, 118(3), 442–444. doi:10.1016/j.econlet.2012.12.004

- Harrant, V., & Vaillant, N. (2008). Are women less risk averse than men? The effect of impending death on risk-taking behavior. Evolution and Human Behavior, 29(6), 396–401. doi:10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2008.05.003

- Hulett, D. M., Bendick, Jr., M., Thomas, S. Y., & Moccio, F. (2008). Enhancing women’s inclusion in firefighting in the USA. International Journal of Diversity in Organisations, Communities & Nations, 8(2), 189–207.

- Jahnke, S. A., Poston, W. C., Haddock, C. K., Jitnarin, N., Hyder, M. L., & Horvath, C. (2012). The health of women in the US fire service. BMC Womens Health, 12(1), 39. doi:10.1186/1472-6874-12-39

- Kimmel, M. (1994). Masculinity as homophobia: Fear, shame and silence in the construction of gender identity. In H. Brod & M. Kaufman (Eds.), Theorizing masculinities (pp. 119–141). London, England: Sage.

- Maxfield, S., Shapiro, M., Gupta, V., & Hass, S. (2010). Gender and risk: Women, risk taking and risk aversion. Gender in Management: An International Journal, 25(7), 586–604. doi:10.1108/17542411011081383

- National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. National Electronic Injury Surveillance System (NEISS) All Injury Program. (2012). Unintentional all injury causes nonfatal injuries and rates per 100,000. Retrieved from http://webappa.cdc.gov/cgi-bin/broker.exe.

- Olofsson, A., & Rashid, S. (2011). The white (male) effect and risk perception: Can equality make a difference? Risk Analysis, 31(6), 1016–1032. doi:10.1111/j.1539-6924.2010.01566.x

- QSR International Pty Ltd. (2012). NVivo qualitative data analysis software, Version 10 [computer software]. Doncaster, VIC, Australia: QSR International.

- Schneider, B., Gunnarson, S. K., & Niles-Jolly, K. (1994). Creating the climate and culture of success. Organizational Dynamics, 23(1), 17–29. doi:10.1016/0090-2616(94)90085-x

- Sexton, J. B., Helmreich, R. L., Neilands, T. B., Rowan, K., Vella, K., Boyden, J., … Thomas, E. J. (2006). The safety attitudes questionnaire: Psychometric properties, benchmarking data, and emerging research. BMC Health Services Research, 6, 44.

- Slovic, P. (1999). Trust, emotion, sex, politics, and science: Surveying the risk-assessment battlefield. Risk Analysis, 19(4), 689–701. doi:10.1111/j.1539-6924.1999.tb00439.x

- Tracy, S. J., & Scott, C. (2006). Sexuality, masculinity, and taint management among firefighters and correctional officers: Getting down and dirty with “America’s Heroes” and the “Scum of Law Enforcement.” Management Communication Quarterly, 20(1), 6–38. doi:10.1177/0893318906287898

- Yoder, J. D., & Aniakudo, P. (1996). When pranks become harassment: The case of African American women firefighters. Sex Roles, 35(5–6), 253–270. doi:10.1007/bf01664768

- Yoder, J. D., & Aniakudo, P. (1997). “Outsider within” the firehouse: Subordination and difference in the social interactions of African American women firefighters. Gender & Society, 11(3), 324–341. doi:10.1177/089124397011003004

- Yoder, J. D., & Berendsen, L. L. (2001). “Outsider within” the firehouse: African American and white women firefighters. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 25(1), 27–36. doi:10.1111/1471-6402.00004