Abstract

Existing models of job stress assume consistent appraisals of stressors over the course of a career, and the developing nature of workers is often overlooked. This study explored how workers’ self-concepts evolved over the career development process, and the conjoined experience of stress. Semi-structured interviews were conducted between April 2017 and October 2018 with 17 engineers employed at a Japanese construction firm. A coding procedure based on grounded theory was used to identify key categories. Early in their careers, workers viewed themselves as mostly carrying out assigned tasks in a passive manner. Over the career course, workers had a growing sense of responsibility toward their work and tried to fulfill their roles as proactive agents. Eventually, workers came to view themselves as making contributions to their jobs by creating unique value. Accordingly, a stressor (e.g., work pressure) was perceived differently as the self-concept evolved, namely as psychological distress, challenge for growth, or opportunity to express one’s value. These findings suggest that the psychological management of work-induced distress and eustress should match a worker’s development of self-concept over the course of a career.

Introduction

Although studies on work-related stress have long focused on physical and psychological distress, recent studies have adopted the positive psychology perspective to address eustress—the positive aspects of work experiences such as work engagement (Attridge, Citation2009; Bakker & Derks, Citation2010). Accordingly, the theoretical models of job stress and subsequent empirical studies have sought to identify the work environment characteristics that lead to workers’ distress and eustress (Colligan & Higgins, Citation2006; Kahn & Byosiere, Citation1992). For example, the job demands–resources model suggests that general categories of job demands (e.g., work pressure, emotional demands, and role ambiguity) and job resources (e.g., social support, performance feedback, and autonomy) result in workers’ strain and motivation, respectively, which, in turn, affect organizational outcomes (Bakker & Demerouti, Citation2007).

Existing models of job stress usually aim to explain general relationships between stressors and health outcomes that are applicable to a wide range of occupational settings (Mark & Smith, Citation2008). In contrast, some studies have suggested that job stressors are experienced differently depending on a worker’s appraisal of these stressors in different situations (Lazarus & Folkman, Citation1984; Rodríguez, Kozusznik, & Peiró, Citation2013; Webster, Beehr, & Love, Citation2011). Instead of classifying the stressors a priori as either negative or positive, these studies emphasize workers’ experience of stress under specific circumstances (Glazer & Liu, Citation2017).

Some studies have further explored the psychosocial factors shaping workers’ stress appraisal. However, these studies have focused mainly on the personality traits that are considered stable over time (e.g., optimism, hardiness, and locus of control), and the evolving and developing nature of workers is often overlooked (Nelson & Simmons, Citation2003; Parent-Lamarche & Marchand, Citation2019). An exception is a field of study pertaining to workers’ self-concept, which refers to a worker’s evoked sense of himself or herself when performing the job (Gecas, Citation1982; Walsh & Gordon, Citation2008). A worker’s self-concept is dynamic and is constructed and reconstructed throughout his/her career (Hall, Citation2002). Theoretical studies have posited that workers with different identities (a term used synonymously with self-concepts) attach different meanings to stressors and, hence, appraise these stressors differently (Ashforth & Kreiner, Citation1999; Thoits, Citation2013). Indeed, empirical studies have found that the health effects of job stressors vary across a worker’s career stages and job roles (Frone, Russell, & Cooper, Citation1995; Hurrell, Mclaney, & Murphy, Citation1990), possibly as a result of changes in self-concept at different career stages, or certain time periods in a worker’s work life that are characterized by distinctive values, attitudes, and expectations of the worker (Hall, Citation2002).

These lines of study suggest that the process through which workers (re)construct their self-concept may be dynamically associated with their stress experiences. To the best of our knowledge, however, existing job-stress models pay limited attention to the dynamic nature of stress experiences (Cooper, Dewe, & O’Driscoll, Citation2001), especially in association with the process of self (re)construction. Therefore, the purpose of the present study was to explore the process through which workers (re)construct their work-related self-concept in the workplace and the relationship between this process and the stress experience.

We expect the present study to open a new platform by integrating stressors, which are identified in existing models as leading to either distress or eustress, within the conceptual framework of self (re)construction. This study may also contribute to designing a set of preventive interventions by indicating the risk factors to which workers with specific self-concepts are especially vulnerable.

Methods

Study design

A qualitative research design was employed because the themes of the present study were relatively unexplored in the existing literature. Specifically, grounded theory methodology was used for the data collection and data analysis. Grounded theory methodology aims to develop a conceptual model that explains the phenomenon of interest. The procedures involved are primarily inductive and abductive, starting from empirical observations and moving toward abstract concepts and the relationships between them, with an emphasis on constant comparison (Corbin & Strauss, Citation2015; Neuman, Citation2014). We employed this method in the present study specifically because the study aimed to develop a new conceptual model that could be compared and contrasted with existing models.

Participants

The present study focused on civil and architectural engineers (hereafter referred to as engineers) working at a large construction firm in Japan. This focus was chosen based on the principle of extreme case sampling (Patton, Citation2002), where job stress is reported to be high in these occupations. Construction work is characterized by its project-based nature, which requires the involvement of multiple stakeholders, each of whom has a different goal, and these goals must be combined with limited time and within a limited budget (Leung, Chan, & Cooper, Citation2014). These characteristics have implications for the types of stressors to which construction personnel may be exposed, such as personal (e.g., work–home conflict), interpersonal (e.g., distrust in teams), task (e.g., work overload), organizational (e.g., lack of manpower), and physical (e.g., an unsafe site environment; Leung et al., Citation2014). Thus, construction personnel, including engineers, engage in work that is both physically and psychologically demanding (Lingard & Turner, Citation2017). In addition, Japanese production management, known as kaizen—or lean production, is practiced in the construction industry. Although this practice enhances efficiency and competitiveness, it may also impose pressure on workers to work harder, leading to distress among construction personnel (Kawakami & Haratani, Citation1999; Lingard & Rowlinson, Citation2005). Indeed, among workers in all occupations in Japan, engineers in the construction industry have been found to have the highest number of compensation claims for job-related health problems such as cardiovascular disease and mental disorders (Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Citation2018).

An additional reason for selecting this company was its use of the lifetime employment system, which is associated with long-term relationships between employers and workers, characterized by mutual trust, goodwill, and commitment and often accompanied by employment contracts without fixed duration (Kondo, Citation1990; Moriguchi & Ono, Citation2006). This type of employment prevailed in the majority of companies in Japan until the 1990s, when the economic recession and the rise of globalization forced some companies to implement layoffs, pay-for-performance plans, and mid-career recruitment, thus withdrawing from the lifetime employment system. However, the lifetime employment system has been maintained in relatively large firms in Japan (Moriguchi & Ono, Citation2006). A core feature supporting this system is human capital development via various programs, such as on-the-job and off-the-job training, which aims to improve a worker’s ability over the course of his/her career, thus providing incentives for both employers and workers to retain their relationship (Moriguchi & Ono, Citation2006). Because this system encourages workers to grow and thrive, we anticipated observing a process through which workers’ self-concepts evolved over their careers (Kegan, Citation1982; Kegan & Lahey, Citation2016). The company selected for the present study specialized in the design and management of construction projects in both the private and the public sectors. We had access to a contact person in the company who provided support throughout the research process.

Purposive sampling was used to recruit engineers working at the participating company. The inclusion criteria were permanent employment and experience performing engineering work in either the civil engineering department or the architecture department. These criteria were selected because we specifically aimed to explore how workers’ self-concepts evolved over the course of their careers in different work environments. During the participant recruitment process, the above-mentioned liaison in the company contacted the heads of the relevant departments (i.e., the civil engineering, architecture, and human resources departments) on behalf of the researchers to convey information about the study to the workers and to grant permission for interested employees to participate in the interview during their working hours. Prospective participants then contacted the liaison to schedule a date for their interview. Because the liaison neither belonged to the departments from which the participants were recruited nor was in the position to assess the participants, the involvement of the liaison was considered having minimal effect, if any, on the participants’ decisions to take part in the interview. In total, 17 participants were interviewed ().

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of participants (N = 17).

Data collection

The interviews were conducted in the company’s meeting rooms by one of the authors (N.Y.) from April 2017 to October 2018. The interviews began with questions about the participant’s demographic characteristics, including age, sex, education, and occupational position. The semi-structured interviews then continued, following an interview guide. The interviewer first asked a “life-chapter question” (McAdams, Citation1993), which allowed each participant to organize their work history into a narrative consisting of several sections reflecting different time points in their career. Specifically, the interviewer made the following or similar request: “I would like you to begin by imagining your work history as if it were a book, where each part of the history composes a chapter. Now, please divide your work history into its major chapters, and briefly describe each chapter.” This was followed by a question concerning the salient stress experiences in each chapter mentioned: “Could you talk about your experience when you felt/feel distressed or motivated in your work?” All participants were asked to divide their work lives into chapters and then to describe the salient stress experiences in each life chapter in this manner.

With the consent of the participants, all interviews were audio-recorded and field notes were taken. The field notes contained key words and brief summaries of the responses that were considered relevant. Each interview lasted 60–90 min. Five of the 17 participants also participated in follow-up interviews.

Data analysis

All interviews were transcribed verbatim prior to analysis. The analysis mainly consisted of three coding steps, namely initial coding, axial coding, and theoretical coding (Saldaña, Citation2016). First, initial coding was conducted. In this step, the interview data were coded word by word and line by line to understand the detailed experiences of the participants. Second, axial coding was conducted to organize and synthesize the fragmented pieces of code into categories with higher levels of abstraction. Additionally, the relationships between the categories were explored by comparing the data within and between individual participants. Third, theoretical coding was conducted to develop a conceptual model by focusing on the relevant categories and subcategories, as well as the relationships between them. These steps were repeated iteratively throughout the analytical process. The field notes were used as supplementary material to guide the coding procedure by suggesting parts of the data requiring special attention.

Both authors participated in the analysis, with different roles. First, N.Y. performed the coding procedure. Then, N.Y. and H.H. engaged in intensive peer debriefing to review the codes, interpretations, and assumptions.

The interviews were conducted and analyzed in Japanese. The textual materials involved in the process—the interview transcripts and field notes—were maintained in the original language. The resulting categories and key passages were subsequently translated into English by the researchers.

Quality control of the analysis

We used multiple analytical procedures to enhance the credibility of the study (Corbin & Strauss, Citation2015). In the early stages of data collection and analysis, peer debriefing was conducted with researchers who are familiar with grounded theory methodology to obtain feedback on the data collection and analysis process. For example, multiple approaches to coding were explored through group discussion during the initial coding. Member checking and follow-up interviews were also undertaken with the participants to ensure that the researchers’ interpretations reflected the participants’ intended meaning. Specifically, during the follow-up interviews, the researchers first presented their interpretations of key terms and expressions appearing in the transcript that had not been fully explicated during the first interview. The participants were then given the opportunity to confirm and/or elaborate on these interpretations by describing additional experiences. In later stages of data analysis, the results were fed back to the participants to determine whether the findings resonated with their experiences. This process, in contrast to the initial phase of member checking, involved abstract categories, and the participants generally responded that they “felt right” about these categories.

Ethical considerations

The study was reviewed and approved by the institutional ethics committee of the institution with which the authors are affiliated (No. 11507). Prior to beginning each interview, the interviewer provided a brief explanation of the study to the prospective participant. This explanation included descriptions of the study’s purpose, methods, and ethical considerations. Then, informed consent was obtained from those who agreed to participate in the interview. To ensure confidentiality, only the interviewer and the participant were present in the room during the interview.

Results

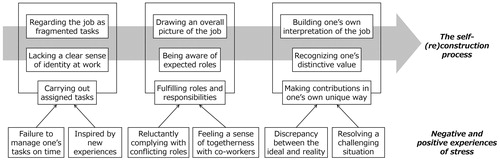

The emergent categories indicated that the (re)construction of the workers’ self-concept in terms of how they viewed themselves in relation to their work comprised three major stages: carrying out assigned tasks, fulfilling roles and responsibilities, and making contributions in one’s unique way. These categories were supported by constitutive subcategories. Importantly, the engineers’ stress experiences in terms of what was perceived as negatively or positively affecting them varied across the self-(re)construction process. Over this process of self (re)construction, the engineers also created meaningfulness in their jobs, which was often manifested as their “personal philosophy” toward work.

Carrying out assigned tasks

When the engineers were new to their jobs, they regarded the job as fragmented tasks and lacked a clear sense of their role at work. Consequently, they viewed themselves as mostly carrying out assigned tasks. That is, the engineers primarily focused on completing an assigned task for its own sake because they were not yet able to find meaningfulness in their work.

In the beginning, although I was given some task assignments, I wasn’t sure why I was doing them because I had no image of the overall picture. I was doing my work just because I was told to do so. [#9, 30 s]

Regarding the job as fragmented tasks

In the early stage of career development, the engineers regarded the pieces of the tasks assigned to them as their job. Because of their lack of knowledge and experience during this period, they struggled to fully understand the purpose of each task, and they had a limited grasp of the relationships between those tasks.

Before I got used to the basic procedures of my work, I had no idea what I should do. So I just worked on those miscellaneous tasks given to me. [#5, 40 s]

Lacking a clear sense of identity at work

In addition, novice engineers rarely had a clear sense of their role in the work setting. They were unsure about the expectations of their coworkers, supervisors, and clients, and they were therefore unable to position themselves among the relevant stakeholders.

At the beginning, I mean just after I entered the company, I didn’t know how to present myself in the worksite. [#8, 40 s]

Failure to manage tasks on time

Because novice engineers focused on carrying out their assigned tasks, one potentially negative experience was the inability to manage these tasks on time. In the early career stages, the engineers were often deficient in the skills and knowledge required to carry out their tasks. Consequently, when they struggled to manage the assigned tasks in a timely manner, they felt overwhelmed by their work.

There were so many things to do every day, with lots of items to take care of. It was just not possible for me to manage them. I was saying in my head, “I’m working till midnight, but it’s just not possible to finish everything!” I had a hard time then. [#7, 30 s]

Inspired by new experiences

In contrast, some experiences had positive or motivational effects on the novice engineers. For example, they were inspired by new experiences and events in the workplace. They were motivated to acquire new knowledge and skills, although this feeling did not last long and eventually disappeared as they became accustomed to their new jobs.

[By working on new tasks], my skills as an engineer improved and I gradually became capable of doing those new tasks. This brought me a feeling of satisfaction. [#6, 30 s]

Fulfilling roles and responsibilities

As the engineers became capable of drawing an overall picture of the job and became aware of their expected roles, their self-concept grew to be more than just carrying out their assigned tasks; it expanded to fulfilling roles and responsibilities. The most notable difference compared with the previous phase involved the engineers’ agency at this stage. When they focused solely on carrying out their tasks, the engineers tended to follow instructions in a passive manner. In contrast, during this second stage, the engineers had a growing sense of responsibility toward their work and were confident in making some decisions by themselves as proactive agents, based on the skills and experiences they were acquiring.

There was a growing sense of responsibility in myself. Previously, I was doing what I was told to do, but now I have to think for myself and I’m responsible for the decisions I make. [#4, 30 s]

Drawing an overall picture of the job

As the engineers became more experienced and skillful, they came to recognize the purpose of each task and to be more aware of the relevant stakeholders. They gradually came to understand how the tasks and stakeholders were interrelated.

As I worked at a project site for a while, I started to notice the overall cycle of the project. For example, when creating reinforced concrete structures, we make pillars first, next beams, and then floors. [#8, 40 s]

Being aware of expected roles

As they acquired an overall picture of their jobs, the engineers began to understand their expected roles and responsibilities in terms of what they should be doing and how they should be performing in the workplace.

At first, I thought I came to this department to learn a variety of skills. I recognized myself as a guest. But this eventually changed. I started to think that I should be working as a leading person regarding concrete technologies in this department. [#9, 30 s]

Reluctantly complying with conflicting roles

During this period, the engineers had a growing sense of their roles and responsibilities, which was nurtured through their work experiences. However, to meet others’ expectations, the engineers occasionally had to complete tasks that conflicted with their existing roles.

About 10 years ago, when the market was highly competitive, we had to lower the price of our products to get contracts. But honestly that strategy led to “cheap and nasty” products. […] I was getting sick of doing that and was thinking inside my heart, “Why don’t we just give up these contracts and keep the quality of our products high?” [#17, 40 s]

Feeling a sense of togetherness with coworkers

In contrast, one type of positive and motivational experience the engineers reported during this stage was the feeling of being accepted as a member of a team in the workplace. In particular, the engineers had a feeling of togetherness when they were trusted and relied upon by their coworkers.

I felt that I became a site manager when the subcontracting staff asked me for help. When they trusted that I could do something for them, I could confirm that I was successfully playing my role as a team member—that of site manager. [#9, 30 s]

Making contributions in one’s unique way

When the engineers eventually built their own interpretation of their job and recognized their distinctive value, they viewed themselves primarily as making contributions in their unique way. The engineers were also able to create meaningfulness in their jobs, which was often manifested as a “personal philosophy.” For example, the engineers who redefined their jobs as harmonizing processes attempted to actively contribute to the creation of harmony in the form of consensus among diverse stakeholders by taking full advantage of their personal strengths.

If we communicate with the stakeholders [when faced with a problem] and break down the complicated structure of the problem, there will always be a way to solve it. This is my philosophy, and this is what I was trying hard to do at the project site. [#8, 40 s]

Building one’s own interpretation of the job

The engineers eventually built their own interpretation of their jobs on the basis of their work experiences. Their interpretations were often in the form of simple statements regarding what they considered essential to their jobs. For example, some redefined their jobs as harmonizing processes among various stakeholders, emphasizing the interpersonal aspect rather than the engineering aspect of projects. The following participant used the term “philosophy” to describe his own interpretation of the job:

It is my philosophy that there is nothing that cannot be solved in projects. People from different organizations with different professional backgrounds get together and build one object, so there will always be conflicts, disputes, and disagreements. And it is our job to fill in the gap between different parties. [#8, 40 s]

Recognizing one’s distinctive value

Through their own interpretations of their jobs, the engineers became increasingly aware of the value they could provide in performing their work. Although they already had a sense of the roles and responsibilities that contributed to their work-related self-concept, they also discovered and recognized their own unique value, on the basis of their accumulated work experience.

As a designer in this company, I think my value resides in my ability to do both [theoretical and practical aspects of] work. Of course, I should be able to say what’s written in a textbook, but that doesn’t distinguish me from other consultants. I should also provide comments about what would happen in reality if we actually do that. […] It is like my reason for being in the workplace. [#7, 30 s]

Discrepancy between the ideal and reality

One significant type of negative experience during this career development stage was the discrepancy between the ideal and reality. Proficient engineers usually had “the ideal” in mind when evaluating the preferred process for and outcomes of their work. However, projects are inherently open to various possibilities because of divergent perspectives introduced by multiple stakeholders. This often resulted in work processes or outcomes being different from what the engineers considered ideal.

Although I had an idea to solve the problem, I wasn’t able to push my idea through. As a result, the solution ended up being different from what I considered favorable. The problem was solved but not in the best way. […] So I was not happy about that. [#5, 40 s]

Resolving a challenging situation

In contrast, resolving a challenging situation at work was a motivational experience that led to positive feelings among the engineers. For example, when they were able to successfully create consensus among stakeholders and push a project forward in a proactive manner, they felt that they were making unique contributions through their work. This feeling also resulted in a stronger sense of engagement in their jobs and increased their self-worth.

Even when I get “bingo” moments in my work where my contribution is quite valuable, it is often unnoticed. Nevertheless, I feel honor when I’m handling my part of the project without being caught up in any trouble. [#2, 30 s]

illustrates the relationships among the categories and subcategories presented above, which together explain the process through which the engineers (re)constructed their work-related self-concept, as well as the relationship between this process and their stress experience.

Discussion

Interpretations

To summarize the key findings, the engineers’ self-concept evolved from merely carrying out assigned tasks, to fulfilling roles and responsibilities, and finally to making contributions in one’s unique way. Importantly, the engineers’ experience of stress in the workplace changed during the process. For example, novice engineers tended to be particularly concerned with failure to manage tasks on time. In contrast, later in their careers, the engineers instead felt anxious about the discrepancy between the ideal and reality.

These results imply that stressors, which are often presumed to be appraised consistently as hindrances or challenges, might be experienced differently depending on a worker’s salient self-concept. For example, novice engineers, who focused on carrying out assigned tasks, were particularly distressed when they failed to manage their tasks in a timely manner, which could be prompted by work pressure. Thus, work pressure might be especially detrimental for novice engineers when it causes them to experience failure to manage their tasks on time. However, for more mature engineers, who focus more on making contributions in one’s unique way, work pressure could instead be a prerequisite for resolving a challenging situation by successfully overcoming this stressor. In this case, work pressure might be perceived as an opportunity instead of a threat.

We found that the process of self (re)construction involved three major stages: carrying out assigned tasks, fulfilling roles and responsibilities, and making contributions in one’s unique way. This finding concurs with previous models of professional career development in the workplace. For example, the five-stage model of skill acquisition proposed by Dreyfus states that, along with skill acquisition, a worker’s attitude may also shift from simply following the rules (the “detached observer”) to more involved participation and emotional commitment (the “involved performer;” Dreyfus, Citation2004). This proposition is in line with our results, where the engineers’ self-concept transformed from merely carrying out assigned tasks, to fulfilling roles and responsibilities, and then to making contributions in one’s unique way. Unlike the Dreyfus model, which focuses primarily on skill acquisition, the present model sheds light on the cognitive and attitudinal aspects of experiences at work.

Our results also suggest that the process of self (re)construction involves two sets of subcategories that are comparable to theoretical propositions in previous studies. The first is related to changes in workers’ perceptions of their jobs (i.e., regarding the job as fragmented tasks, drawing an overall picture of the job, and building one’s own interpretation of the job). These subcategories overlap with the notion of job crafting, and especially with cognitive job crafting, which emphasizes changes in perceptions and understandings of the job and how workers interpret and attach meaning to their jobs (Wrzesniewski & Dutton, Citation2001). The second point of comparison with previous theoretical propositions pertains to workers’ acquisition of social roles in the workplace (i.e., lacking a clear sense of role at work, being aware of expected roles, and recognizing one’s distinctive value). These subcategories are related to the notion of organizational socialization, in which a worker learns the beliefs and values that are shared within the workplace and thus makes the role transition from “outsider” to “insider” (Ashforth & Saks, Citation1996; Hall, Citation2002).

Finally, the transferability of the resulting model should be considered (Polit & Beck, Citation2010). The underlying premise of the current model is that the company attempts to provide engineers with an environment and opportunities that encourage their development within the company, and the engineers also expected this. This type of relationship between a company and its workers derives partly from the above-mentioned lifetime employment system, in which job security and career prospects are largely guaranteed. Therefore, the categories, subcategories, and relationships among them explored in the present study may also operate well for workers in other similar settings. In contrast, the conceptual model may have limited applicability to workers in different types of settings, such as those with non-regular employment (e.g., part-time or contract employment) or in small and medium-sized enterprises, who have less access to education and training provided by the company and thus have less opportunity to develop their careers within the company (Sano, Citation2012; The Japan Institute for Labour Policy and Training, Citation2016). In these types of settings, job insecurity and the lack of career prospects may emerge as prominent sources of distress for workers (Lai, Saridakis, & Blackburn, Citation2015).

The self-concepts developed in the present study may also reflect the culturally specific nature of the self in Japan. Notably, the emergent categories in this study (i.e., carrying out assigned tasks, fulfilling roles and responsibilities, and making contributions in one’s unique way) imply that the self-concepts assume the presence of other people and also evolve in close relationship with others. As previous studies have noted, individuals with high “interdependent self-construal” define the self with reference to group memberships in order to maintain group harmony, which are considered typical in Japan. In contrast, individuals with high “independent self-construal” are more likely to define the self with reference to dispositional characteristics that are stable and, hence, to seek independence from the group (Cross, Hardin, & Gercek-Swing, Citation2011; Markus & Kitayama, Citation1991). Therefore, caution is needed in applying our results to workers in cultural contexts where independent self-construal is dominant.

Implications

Although the conceptual model explored in the present study warrants further examination with quantitative methods, several possible implications can be inferred. The study’s findings imply that efforts to reduce distress and promote eustress should be considered in conjunction with the self-(re)construction process because workers’ stress experience varied across different stages of development of their self-concept.

Among workers who focus on carrying out assigned tasks, intervention measures such as reducing workload and providing instrumental support might be effective in alleviating the distress caused by failure to manage tasks on time. Assigning diverse tasks might contribute to sustaining the motivation of these workers by inspiring them with new experiences.

For workers who put more emphasis on fulfilling roles and responsibilities, it might be more important for supervisory personnel to prevent reluctant compliance with conflicting roles. Nurturing trust among coworkers in the workplace would also be beneficial because it might lead to workers feeling a sense of togetherness.

For those workers who are particularly concerned with making contributions in one’s unique way, guaranteeing the fairness of decision-making procedures may mitigate the emotional disturbance associated with discrepancy between the ideal and reality. An adequate level of psychological demand may also be advantageous because these workers feel motivated when they successfully resolve a challenging situation.

Limitations

A major limitation of the present study is that only workers who were able to continue working at the company were included. Workers who experienced turnover because of job stress were not included in the present study, and the categories found in this study may not explain job-stress-induced turnover among these excluded workers. Thus, future research should incorporate workers with different outcomes to explore variations in the categories (Mays & Pope, Citation2000). This future research could result in the modification of the conceptual model developed in the present study.

In addition, it is worth noting that the participants of the present study were mostly male, which may stem from the male-dominated environment of construction companies in general (Lingard & Rowlinson, Citation2005). The participants were also highly educated and many of them were in the positions of assistant manager, manager, or general manager. These participants were distinctive in terms of their willingness to develop their professional careers under the provisions of career support and opportunities. Therefore, future research could incorporate cases with other characteristics, such as those workers who are less interested in developing their professional careers. This could enhance constant comparisons and thus may improve the categories in terms of their variations.

Furthermore, this study relied on a single data collection method and data source. Although a strength of qualitative interviews is that they enable the exploration of workers’ subjective experiences (Mazzola, Schonfeld, & Spector, Citation2011), this method is also prone to bias, such as recall bias, caused by varying accuracy in people’s memories about their history (Malone, Nicholl, & Tracey, Citation2014). Thus, there might be a discrepancy between the actual interactions taking place in the workplace and the participants’ descriptions of these interactions. Triangulation of data collection methods and data sources may compensate for this weakness (Denzin, Citation1989). In particular, observational data on workers’ behaviors and interactions in the workplace could be incorporated into a study through participant observation. Such a study could contribute to a better understanding of the phenomenon of interest and could enhance the credibility of the findings.

Conclusion

This study revealed a conceptual model that explains the process through which the work-related self-concept is (re)constructed in the workplace and the association between this process and workers’ stress experiences. The results suggest that the engineers’ experiences of stressors perceived as negatively or positively affecting them varied across the self-(re)construction process (i.e., carrying out assigned tasks, fulfilling roles and responsibilities, and making contributions in one’s unique way). These findings imply that prospective interventions that consider the evolving and developing nature of workers’ self-concept in the workplace may either reduce distress or promote eustress. Future research may incorporate data and methodological triangulations to further elaborate on the categories and conceptual model being developed in the present study.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ashforth, B. E., & Kreiner, G. E. (1999). “How can you do it?”: Dirty work and the challenge of constructing a positive identity. Academy of Management Review, 24(3), 413–434. doi:10.5465/amr.1999.2202129

- Ashforth, B. E., & Saks, A. M. (1996). Socialization tactics: Longitudinal effects on newcomer adjustment. Academy of Management Journal, 39(1), 149–178. doi:10.5465/256634

- Attridge, M. (2009). Measuring and managing employee work engagement: A review of the research and business literature. Journal of Workplace Behavioral Health, 24(4), 383–398. doi:10.1080/15555240903188398

- Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2007). The Job Demands–Resources model: State of the art. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 22(3), 309–328. doi:10.1108/02683940710733115

- Bakker, A. B., & Derks, D. (2010). Positive occupational health psychology. In S. Leka & J. Houdmont (Eds.), Occupational health psychology (pp. 194–224). Chichester, UK: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Colligan, T. W., & Higgins, E. M. (2006). Workplace stress: Etiology and consequences. Journal of Workplace Behavioral Health, 21(2), 89–97. doi:10.1300/J490v21n02_07

- Cooper, C. L., Dewe, P. J., & O’Driscoll, M. P. (2001). Organizational stress: A review and critique of theory, research, and applications. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

- Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. (2015). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory (4th ed.). Los Angeles, CA: SAGE Publications.

- Cross, S. E., Hardin, E. E., & Gercek-Swing, B. (2011). The what, how, why, and where of self-construal. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 15(2), 142–179. doi:10.1177/1088868310373752

- Denzin, N. K. (1989). The research act: A theoretical introduction to sociological methods (3rd ed.). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Dreyfus, S. E. (2004). The five-stage model of adult skill acquisition. Bulletin of Science, Technology & Society, 24(3), 177–181. doi:10.1177/0270467604264992

- Frone, M. R., Russell, R., & Cooper, M. L. (1995). Job stressors, job involvement and employee health: A test of identity theory. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 68(1), 1–11. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8325.1995.tb00684.x

- Gecas, V. (1982). The self-concept. Annual Review of Sociology, 8(1), 1–33. doi:10.1146/annurev.so.08.080182.000245

- Glazer, S., & Liu, C. (2017). Work, stress, coping, and stress management. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Psychology. Retrieved from 10.1093/acrefore/9780190236557.013.30.

- Hall, D. T. (2002). Careers in and out of organizations. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

- Hurrell, J. J., McIaney, M. A., & Murphy, L. R. (1990). The middle years: Career stage differences. Prevention in Human Services, 8(1), 179–203. doi:10.1300/J293v08n01_12

- Kahn, R. L., & Byosiere, P. (1992). Stress in organizations. In M. D. Dunnette & L. M. Hough (Eds.), Handbook of industrial and organizational psychology (2nd ed., pp. 571–650). Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press.

- Kawakami, N., & Haratani, T. (1999). Epidemiology of job stress and health in Japan: Review of current evidence and future direction. Industrial Health, 37(2), 174–186. doi:10.2486/indhealth.37.174

- Kegan, R. (1982). The evolving self. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Kegan, R., & Lahey, L. L. (2016). An everyone culture: Becoming a deliberately developmental organization. Boston, MA: Harvard Business Review Press.

- Kondo, D. K. (1990). Crafting selves: Power, gender, and discourses of identity in a Japanese workplace. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Lai, Y., Saridakis, G., & Blackburn, R. (2015). Job stress in the United Kingdom: Are small and medium-sized enterprises and large enterprises different? Stress and Health, 31(3), 222–235. doi:10.1002/smi.2549

- Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York, NY: Springer.

- Leung, M. Y., Chan, I. Y. S., & Cooper, C. L. (2014). Stress management in the construction industry. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons.

- Lingard, H., & Rowlinson, S. (2005). Occupational health and safety in construction project management. New York, NY: Spon Press.

- Lingard, H., & Turner, M. (2017). Construction workers’ health: Occupational and environmental issues. In F. Emuze & J. Smallwood (Eds.), Valuing people in construction (pp. 22–40). London, UK: Routledge.

- Malone, H., Nicholl, H., & Tracey, C. (2014). Awareness and minimisation of systematic bias in research. British Journal of Nursing, 23(5), 279–282. doi:10.12968/bjon.2014.23.5.279

- Mark, G. M., & Smith, A. P. (2008). Stress models: A review and suggested new direction. In J. Houdmont & S. Leka (Eds.), Occupational health psychology: European perspectives on research, education and practice (pp. 111–144). Nottingham, UK: Nottingham University Press.

- Markus, H. R., & Kitayama, S. (1991). Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychological Review, 98(2), 224–253. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.98.2.224

- Mays, N., & Pope, C. (2000). Qualitative research in health care. Assessing quality in qualitative research. BMJ, 320(7226), 50–52. doi:10.1136/bmj.320.7226.50

- Mazzola, J. J., Schonfeld, I. S., & Spector, P. E. (2011). What qualitative research has taught us about occupational stress. Stress and Health, 27(2), 93–110. doi:10.1002/smi.1386

- McAdams, D. P. (1993). The stories we live by: Personal myths and the making of the self. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Government of Japan. (2018). Karoshi tou boushi taisaku hakusyo [White paper on the prevention of karoshi]. Retrieved from https://www.mhlw.go.jp/wp/hakusyo/karoushi/18/dl/18-1.pdf.

- Moriguchi, C., & Ono, H. (2006). Japanese lifetime employment: A century’s perspective. In M. Blomström & S. La Croix (Eds.), Institutional change in Japan (pp. 164–188). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Nelson, D. L., & Simmons, B. L. (2003). Health psychology and work stress: A more positive approach. In J. C. Quick & L. E. Tetrick (Eds.), Handbook of occupational health psychology (pp. 97–119). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Neuman, W. L. (2014). Social research methods: Qualitative and quantitative approaches (7th ed.). Essex, UK: Pearson Education Limited.

- Parent-Lamarche, A., & Marchand, A. (2019). Work and depression: The moderating role of personality traits. Journal of Workplace Behavioral Health, 34(3), 219–239. doi:10.1080/15555240.2019.1614455

- Patton, M. Q. (2002). Qualitative research and evaluation methods (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

- Polit, D. F., & Beck, C. T. (2010). Generalization in quantitative and qualitative research: Myths and strategies. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 47(11), 1451–1458. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2010.06.004

- Rodríguez, I., Kozusznik, M., & Peiró, J. M. (2013). Development and validation of the Valencia Eustress-Distress Appraisal Scale. International Journal of Stress Management, 20(4), 279–308. doi:10.1037/a0034330

- Saldaña, J. (2016). The coding manual for qualitative researchers (3rd ed.). London, UK: SAGE Publications.

- Sano, Y. (2012). Conversion of non-regular employees into regular employees and working experiences and skills development of non-regular employees at Japanese companies. Japan Labor Review, 9(3), 99–126.

- The Japan Institute for Labour Policy and Training; Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Government of Japan. (2016). Labor situation in Japan and its analysis: General overview 2015/2016. Retrieved from https://www.jil.go.jp/english/lsj/general/2015-2016/2015-2016.pdf.

- Thoits, P. A. (2013). Self, identity, stress, and mental health. In C. S. Aneshensel, J. C. Phelan, & A. Bierman (Eds.), Handbook of the sociology of mental health (2nd ed., pp. 357–377). New York, NY: Springer.

- Walsh, K., & Gordon, J. R. (2008). Creating an individual work identity. Human Resource Management Review, 18(1), 46–61. doi:10.1016/j.hrmr.2007.09.001

- Webster, J. R., Beehr, T. A., & Love, K. (2011). Extending the challenge-hindrance model of occupational stress: The role of appraisal. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 79(2), 505–516. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2011.02.001

- Wrzesniewski, A., & Dutton, J. E. (2001). Crafting a job: Revisioning employees as active crafters of their work. Academy of Management Review, 26(2), 179–201. doi:10.5465/amr.2001.4378011