Abstract

First responders are frequently exposed to dangerous, high-stress, and traumatic situations, leaving them susceptible to both physical and mental health consequences. The current study explored factors that relate to both health and well-being in 391 first responders (255 males and 136 females), aged 18–64 years. The study’s aim was to explore the role of psychological capital (PsyCap), self-compassion, social support, relationship satisfaction, and physical activity in the health and well-being of first responders. Data was collected using an online survey which was distributed to first responders, including firefighters, police officers, and emergency medical personnel, in the state of Massachusetts, USA. Descriptive and correlational statistics were performed, followed by hierarchical multiple regression analysis and path analysis, revealing that PsyCap, self-compassion, social support, relationship satisfaction, as well as physical activity are key mediating factors impacting the health and well-being of first responders. Findings pose as a foundation and stepping-stone to improve first responders’ health and well-being. In particular, a multifaceted approach to intervention drawing on the combined variables identified in the path model is indicated.

Introduction

First responders are broadly defined as individuals who are first to arrive on the scene of an emergency, accident, or disaster, facing dangerous, challenging, and cumbersome situations to preserve and protect life, environment, and property (Arble & Arnetz, Citation2017; Marmar et al., Citation2006). They are further responsible for immediately reaching out to the survivors of disasters and providing not only physical but also emotional support (Kleim & Westphal, Citation2011). Historically, first responders include firefighters, search and rescue teams, police, and emergency medical personnel (Geronazzo-Alman et al., Citation2017). They are essential in ensuring the safety of the community following a disaster and maintaining critical public functions. While these duties are indispensable for the entire community, they are strenuous and taxing to first responders, putting them at risk for experiencing several physical and mental health consequences (Benedek, Fullerton, & Ursano, Citation2007; Fullerton, Ursano, & Wang, Citation2004).

Firefighters, police officers, and emergency medical personnel carry a 73% greater mortality risk compared to their non-first responder peers (Pedersen, Ugelvig Petersen, Ebbehøj, Bonde, & Hansen, Citation2018). During emergency missions, first responders are significantly more likely to suffer cardiac events, including sudden death, than while carrying out non-emergency duties (Varvarigou et al., Citation2014). First responders are also more likely to suffer early-onset cardiovascular disease and heart rate variability (Hourani et al., Citation2020; Superko et al., Citation2011).

The frequent exposure to high-stress situations and cumulative exposure to trauma also increases first responders’ risk for developing mental health consequences (McKeon et al., Citation2019). Overall, the prevalence of depression, PTSD, anxiety, sleep disturbances, and alcohol abuse in this profession is higher than among the general population (Jones, Citation2017). A systematic review by Stanley, Hom, and Joiner (Citation2016) indicates that emergency medical personnel, police officers, and firefighters may face a higher risk for suicidal thoughts as well as behaviors acting on these (Stanley et al., Citation2016).

Pietrantoni and Prati (Citation2008) looked at resilience among first responders and noted that in their sample, rescue and emergency personnel in fact experienced a low level of compassion fatigue and burnout while reporting overall good job satisfaction. The study found that despite being exposed to emergency situations, the majority of first responders do not appear to be affected by burnout or traumatic stress. The authors concluded that this observed resilience to critical events is based on feeling a sense of community among coworkers, experiencing collective efficacy, as well as self-efficacy. Research has shown that Psychological Capital (PsyCap), consisting of hope, resilience, optimism, and efficacy, is a measurable, valid, and reliable construct. PsyCap emerged as a good predictor for job satisfaction and the study authors emphasize that the four composite factors as a unit are superior at predicting job satisfaction and performance over each individual component (Luthans, Avolio, Avey, & Norman, Citation2007). Evidence suggests PsyCap is an important resource in promoting health and well-being (Avey, Luthans, Smith, & Palmer, Citation2010; Luthans, Youssef, Sweetman, & Harms, Citation2013; Youssef-Morgan & Luthans, Citation2015), and facilitating the various processes needed for attention, interpretation, as well as retention of constructive and positive memories, which are essential for achieving and maintaining well-being (Luthans & Youssef-Morgan, Citation2017).

Self-compassion is defined as having the ability to self-soothe and re-assure during difficult, adversarial times and simply being kind to one’s self, and encompasses the recognition that one’s experiences are part of the human condition and to not be judgmental about one’s self (Neff, Citation2003; Neff & Knox, Citation2017). It has been shown to impact positively on well-being and health (Homan & Sirois, Citation2017; Neff & Germer, Citation2017; Zessin, Dickhäuser, & Garbade, Citation2015). Self-compassion is able to elicit a state of mind characterized by calmness and content, including a sense of care, kindness, and social connectedness, the ability to self-soothe during stressful periods in life, further leading to a reduction of negative self-bias (Kirschner et al., Citation2019). On the contrary, self-criticism is considered maladaptive and linked with feelings of isolation and the sense of facing a fight-or-flight situation, leading to a heightened sense of threat during challenging situations (Warren, Smeets, & Neff, Citation2016).

Research on the topic of social support and its impact on health and well-being is robust (Uchino, Citation2006). Viswesvaran, Sanchez, and Fisher (Citation1999) reviewed 68 studies that showed that social support had an impact on the perception of work stress. Ozbay et al. (Citation2007), emphasize the importance of social support for the maintenance of good overall health. The researchers point out that positive social support is able to not only increase resilience to stress but also contribute to warding off trauma-induced psychopathology and reducing its functional consequences (Ozbay et al., Citation2007). Prati and Pietrantoni (Citation2010) meta-analysis examined the influence of social support on psychological health among first responders. The authors found a significant relationship between social support and the mental health of first responders, noting that it poses an element of resilience following traumatic events.

Specifically, family support has been associated with enhanced health outcomes (Holt-Lunstad, Smith, & Layton, Citation2010), and increased life expectancy (Shor, Roelfs, & Yogev, Citation2013). As Adams and Blieszner (Citation1995) point out, family relationships are essential resources for support during difficult times, gaining importance with advancing age (Thomas, Liu, & Umberson, Citation2017; Merz, Consedine, Schulze, & Schuengel, Citation2009).

Holt-Lunstad (Citation2017) notes that friendships may contribute to enhanced health outcomes by having an impact on behavioral as well as psychological processes. Several recent research studies indicated a statistically significant relationship between social network structure and an individual’s wellness states and health behavior (Lin, Faust, Robles-Granda, Kajdanowicz, & Chawla, Citation2019; van der Horst & Coffé, Citation2012).

Romantic relationships, both positive and negative, have shown to be important social interactions with the ability to influence the well-being of the individuals in the partnership (Kamp Dush, Taylor, & Kroeger, Citation2008; Lavner & Bradbury, Citation2010; Roberson, Norona, Lenger, & Olmstead, Citation2018). Research indicates that positive relationship characteristics, like mutual spousal support or the ability to communicate effectively, led to an increase in partners’ well-being, including life satisfaction, and have been associated with both more favorable mental and physical health outcomes (Carr & Springer, Citation2010; Kamp Dush et al., Citation2008; Lavner & Bradbury, Citation2010; Pateraki & Roussi, Citation2013; Roberson et al., Citation2018; Sebern & Riegel, Citation2009). Thomas et al., (Citation2017) note that marital relationships may provide social support, leading to an overall improved ability to cope with stress and adopt more health behaviors, oftentimes leading to enhanced well-being. Alternately, unfavorable relationships tend to have a negative influence on partner well-being, including poor physical health effects and an increase in depressive symptoms (Kamp Dush & Taylor, Citation2012; Kansky, Citation2018).

Individuals with a history of trauma and stress exposure oftentimes exhibit a decrease in critical health behaviors (de Assis et al., Citation2008; Schnurr & Spiro, Citation1999). However, in several research studies, exercise has been reliably associated with increased life satisfaction, overall better physical and mental health, as well as an increase in quality of life (Farmer et al., Citation1988; Meyer & Broocks, Citation2000; Ruegsegger & Booth, Citation2018).

Health and well-being are inherently linked with each other (Diener & Chan, Citation2011; Howell, Kern, & Lyubomirsky, Citation2007; Lyubomirsky, King, & Diener, Citation2005). A meta-analysis by Howell et al. (Citation2007) explored the positive impact well-being may have on health, in both healthy and ill individuals. A variety of health-defining parameters were included, for example, cardiovascular functioning, immune system functioning, and respiratory functioning. The authors concluded that well-being does in fact have an effect on health outcomes, potentially affecting biological pathways by creating a barrier to stress as well as strengthening a person’s immune system (Chida & Steptoe, Citation2008).

This paper will shift from the traditional pathogenetic approach, which focuses on the origins of risk factors and disease, and take a closer look at Antonovsky’s research question “what makes people healthy?” (Antonovsky, Citation1987, p.128, Citation1996), putting the emphasis on salutogenesis instead (Mittelmark & Bauer, Citation2017). In this context, the impact psychological capital, self-compassion, and social support have on a first responder’s health and well-being will be evaluated. Additionally, relationship satisfaction, as well as physical activity, will be taken into consideration.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO, Citation2020), health is defined as a state of physical, mental, as well as social well-being, and not simply as a lack of disease or infirmity. While there is no consensus on a universal definition of well-being, several determinants are generally agreed upon: according to the hedonistic tradition, well-being encompasses the presence of positive moods and emotions, along with the eudemonic tradition including satisfaction with life, the absence of negative emotions like anxiety and depression, positive functioning, and fulfillment (Deci & Ryan, Citation2008; Diener, Citation2000; Ryff & Keyes, Citation1995).

The aim of this study was to estimate the relationships between PsyCap, self-compassion, social support, relationship satisfaction, and physical activity, and the health and well-being of first responders. Understanding the health and well-being of first responders may lead to a better understanding of this complex dynamic, and ultimately to more effective interventions.

Methods

Design: This study employed a survey design, in which questionnaires were utilized in a one-time assessment of a sample population as a method to collect the data. The predictor variables were comprised of participants’ presence and level of psychological capital, self-compassion, social support, relationship satisfaction, and physical activity. The dependent variables were health and well-being.

Participants: Participants (n = 391) in this study were full-time first responders over the age of 18 from the state of Massachusetts, USA. The sample consisted of police officers, fire-fighters, and Emergency Medical Personnel; 255 (65.2%) were male and 136 (34.8%) were female. Ages ranged from 18 to 64 years (M = 35.88, SD = 14.08).

Materials: At the beginning of the survey, participants were asked for age in years, sex (male, female, other, prefer not to say), education (highest qualification), years (years and months) in this job, and current rank. They were then asked to complete the following self-administered questionnaires.

The Self-Compassion Scale—Short Form (SCS-SF) by Neff is an assessment tool that measures an individual’s self-compassion. It has demonstrated psychometric validity (Neff, Citation2016) and is as reliable as the long-form Self-Compassion Scale (Raes, Pommier, Neff, & Van Gucht, Citation2011). It consists of 12 items that assess how an individual typically acts toward himself when experiencing difficult times. Each of the items is rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from Almost Never (=1) to Almost Always (=5). Higher scores indicate a larger amount of self-compassion (Neff, Citation2016). The Cronbach’s alpha for this scale in the current study is 0.80.

The Compound PsyCap (CPC-12) Scale is a composite measure of hope, resilience, self-efficacy, and optimism, encompassing 12 items. Each of the four components is reported on a 6-point Likert scale from Strongly Disagree (=1) to Strongly Agree (=6). It measures psychological capital in a universal manner. The CPC-12 has been demonstrated to have good reliability and external validity (Lorenz, Beer, Pütz, & Heinitz, Citation2016). In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha for the CPC-12 scale was 0.93.

The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS) is a self-report survey that contains 12 items that examine a person’s perception of the social support the person experiences from friends, significant others, and family. Each of the items is rated on a 7-point Likert scale, which ranges from Very Strongly Disagree (=1) to Very Strongly Agree (=7). It has good internal reliability and factorial validity (Dahlem, Zimet, & Walker, Citation1991; Zimet, Powell, Farley, Werkman, & Berkoff, Citation1990). The Cronbach’s alpha for this scale in the current study was 0.92.

The Relationship Assessment Scale (RAS; Vaughn & Matyastik Baier, Citation1999) is a 7-item scale that was created to measure overall satisfaction in a relationship. It is appropriate for the assessment of dating or cohabitating couples as well as for married couples. Its items measure an individual’s satisfaction within a specific relationship. Lower scores reflect low relationship satisfaction while higher scores are indicative of more satisfaction within the relationship. The RAS has been shown to have solid criterion-based validity (Vaughn & Matyastik Baier, Citation1999) as well as good test-retest reliability (Hendrick, Dick, & Hendrick, Citation1998). In the current study, the Cronbach alpha for the Relationship Assessment Scale was 0.93.

The Brief Physical Activity Scale (Marshall, Smith, Bauman, & Kaur, Citation2005) is a 2-item questionnaire to determine physical activity in the general population. One question assesses the duration and frequency of physical activities at moderate intensity, while the second question measures the duration and frequency of vigorous physical exercise performed in a typical week. Results are combined and a scoring algorithm identifies whether an individual meets current physical activity guidelines. It has been identified to be a reliable instrument and it shows validity that is comparable to more lengthy and detailed assessments of physical activity (Marshall et al., Citation2005). The Cronbach’s alpha for this scale in the current study was 0.740.

The Warwick Edinburgh Mental Well-Being Scale short form (WEMWBS) assesses an individual’s well-being, including psychological functioning, cognitive-evaluative dimensions, and affective emotional aspects. It consists of 7 items that prompt individuals to rate their thoughts and feelings throughout the previous two weeks. Each item is ranked on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from None of The Time (=1) to All of The Time (=5). Scores from the seven items are summed up, with lower scores indicating a lesser level of mental well-being, while higher scores reflect an elevated level of mental well-being. It has good content validity as well as test-retest reliability (Tennant et al., Citation2007). The Cronbach’s alpha for the Warwick Edinburgh Mental Well-Being Scale in this study was 0.758.

A single item Health Rating Scale (Wanous & Reichers, Citation1996) was employed: How would you rate your overall health?—Excellent—Good—Fair—Poor. Similar single-question surveys have been utilized to determine individual health and have demonstrated reliability and validity within satisfactory levels (Bowling, Citation2005). Since Cronbach’s alpha requires two random samples of items taken from a number of items contained in a survey, for example, Cronbach (Citation1951), the coefficient alpha could not be calculated for this part of the assessment. However, utilizing a single-item measure in order to assess a self-reported fact is a generally accepted practice (Wanous & Reichers, Citation1996).

Procedure: Upon receiving approval from the University Research Ethics Committee, the study questionnaire was uploaded via Qualtrics Software. The Chief of Police (ret.) of Massachusetts was contacted and informed about the study make-up and purpose. Various regional fire-, police- and EMT department chiefs and training coordinators subsequently received the study information and granted permission for the study to be conducted. First responders who volunteered to take part in the study were provided with a written summary of the study’s goals and expectations of its participants, along with an email link leading to the questionnaire they were asked to complete. The questionnaire was only accessible after consent was given. A total of 391 participants completed the survey in its entirety. Information regarding the survey link was provided on websites so a response rate is impossible to calculate. It was a self-selecting sample. Data were first prescreened for outliers and missing values (Kwak & Kim, Citation2017), and descriptive statistics were obtained. There were less than 2% missing values that were randomly distributed. The middle value on each item was inputted where a value was missing. Data analysis further included Pearson Correlation Coefficient, Hierarchical Multiple Regression Analysis (HMRA), as well as Structural Equation Modeling.

Data analysis: Initial analysis following data cleaning involved descriptive statistics (means and standard deviations) and Pearson bivariate correlations. This was followed by Hierarchical Multiple Regression Analysis (HMRA) to identify the relationship between the measured variables and health and well-being as the dependent variables. As the data is cross-sectional the order of entry of independent variables could have varied. In this instance, variables were entered in the order, demographics, psychological constructs (self-compassion and psychological capital), social constructs (social support and relationships), and finally behavioral constructs in terms of exercise. The significant beta values from the HMRA were then used to test a potential path model of the relationships using the Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) procedure in AMOS 25.

Results

The aim of this study was to explore the relationship between PsyCap, social support, self-compassion, relationship satisfaction, physical activity, and the health and well-being of first responders.

The first part of the analysis involved calculating descriptive statistics and correlations as shown in . These results indicate a significant positive correlation between age and education (r(391) = 0.453, p < 0.01). Results from also propose negative correlations, which were significant, between age and health (r(391) = −0.363, p < 0.01), education and health (r(391) = −0.236, p < 0.01), as well as years in this job and health (r(391) = −0.335). Further, the findings in suggest a statistically significant, positive correlation between age and years on this job (r(391) = 0.956, r < 0.01) and years in this job and education (r(391) = 0.363, r < 0.01).

Table 1. Descriptive statistics and correlations.

To explore these relationships more fully, a hierarchical multiple regression analysis (HMRA) was used firstly with health as the dependent variable, as shown in . As the data is cross-sectional the order of entry of independent variables could have varied. In this instance, variables were entered in the order, demographics, psychological constructs (self-compassion and psychological capital), social constructs (social support and relationships), and finally behavioral constructs in terms of exercise. There have been no previous studies that test these variables in combination therefore there is no precedent upon which to base the order of entry.

Table 2. HMRA to identify the predictors of Health.

Age, sex, education, years in the job, and current rank, were entered as predictor variables in step one and accounted for 14.1% of the variance. Age was the only significant predictor (β = −0.407, p < 0.05). Self-compassion was entered on step two but did not add to the explained variance. Psychological capital was entered on step three but did not add anything significant to the explained variance. Support from friends, family, and significant other, and relationship satisfaction were entered on step four and accounted for 6.5% of the variance in health. The significant individual predictors on this step were supported by family (β = 0.384, p < 0.001), and support from a significant other (β = 0.309, p < 0.001). The exercise was entered on the next step and accounted for 6.4% of the variance in health, (β = 0.272, p < 0.001). Well-being was added on step six and accounted for 2.1% of the variance (β = 0.179, p < 0.001). Overall, the model predicted 29% of the variance in health.

A further HMRA was used with well-being as the dependent variable, as shown in . Age, sex, education, years in the job, and current rank, were entered as predictor variables in step one and accounted for 11.4% of the variance. Education (β = −0.320, p < 0.001) was the only significant predictor. Self-compassion was entered on step two and accounted for 15.2% of the explained variance (β = 0.400, p < 0.001). Psychological capital was entered on step three and accounted for 4.3% of the explained variance (β = 0.235, p < 0.001). Support from friends, family and significant other, and relationship satisfaction were entered on step four and accounted for 7.9% of the variance in well-being. The significant individual predictors on this step were supported by friends (β = 0.161, p < 0.01), support from a significant other (β = 0.195, p < 0.01), and relationship satisfaction (β = 0.153, p < 0.001). The exercise was entered on the next step but did not account for a significant portion of the variance. Overall, the model predicted 37% of the variance in well-being.

Table 3. HMRA to identify the predictors of well-being.

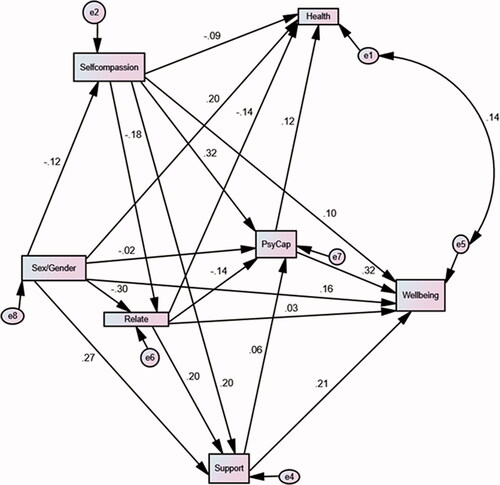

The significant beta values from the HMRA were then used to test a potential path model of the relationships using the Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) procedure in AMOS 25. This allowed testing of a path model of the predictors of well-being and health (See ). For the model to be a good fit for the data the chi-square should be non-significant or the Chi-square divided by the degrees of freedom should be less than 3. In addition, the comparative fit index (CFI), the normed fit index (NFI), and the incremental fit index (IFI) should be greater than 0.95, and the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) should be less than 0.08 (Hu & Bentler, Citation1999; Kline, Citation2015).

In this analysis fit statistics for the model were chi-square (1) = 0.34, p = 0.625, CMIN/DF = 0.24, GFI = 0.99, NFI = 0.99, IFI = 0.99, CFI = 1.00, RMSEA = 0.00, PCLOSE = 0.761. The model was an excellent fit for the data. The data support a tentative path model whereby self-compassion, psychological capital, social support, and quality of relationships combine to explain a portion of the variance in the health and well-being of first responders.

Discussion

The aim of the current study was to explore the relationship between psychological capital (PsyCap), self-compassion, social support, relationship satisfaction, and physical activity, and the health and well-being of first responders. Analysis suggests that psychological capital had no relationship with health and the early correlation of self-compassion is subsumed in later variables. Ultimately the direct predictors of health were social support from friends, family, and significant others, engaging in exercise, and well-being. Both psychological capital and self-compassion did play a role in well-being along with being in a relationship, and support from friends and significant others. In addition, females, those who were younger, those of lower rank, who had been less time in the job and were more educated exhibited better well-being. It would appear that the relationship between psychological capital and self-compassion and health is indirect through their relationship with well-being.

The significant positive correlation between self-compassion and well-being is consistent with previous research findings (Kirschner et al., Citation2019). In fact, self-compassion emerged as the most significant predictor for first responders’ well-being among the participants in this study. Additional research (Homan & Sirois, Citation2017) suggests a favorable impact of self-compassion on an individual’s health due to an increase in well-being.

Consistent with prior research (Luthans & Youssef-Morgan, Citation2017), the current findings note a significant positive correlation between psychological capital and well-being. Again, the relationship with health is indirect. Path analysis suggests that self-compassion may interact with psychological capital in regard to health.

The strong relationship between social support and both health and well-being is consistent with substantial previous findings (Holt-Lunstad, Citation2017; Holt-Lunstad et al., Citation2010; Merz et al., Citation2009; Roberson et al., Citation2018; Shor et al., Citation2013). Relationship satisfaction seems to correlate with well-being but did not have a significant relationship with health although some of the variances here could be subsumed in social support. Path analysis would suggest that relationship satisfaction is related to sex and self-compassion in that females and those with more self-compassion experience more positive relations. Consistent with previous research the importance of physical exercise and fitness for well-being and health is indicated. The results of this study further indicated a positive correlation between well-being and health, reflecting previous research findings (Howell et al., Citation2007).

The main limitations of this study stem from the fact that it is cross-sectional and therefore causal relationships cannot be drawn. Causal relations can be postulated for testing in future studies. The data do not allow the testing of a full SEM and SEM was used to test a set of relationships in a tentative path model. There are also some potential limitations based on the location of the sample although it is likely that the findings will show some generality.

To conclude, the results of this study provide evidence for the possible mediating role of self-compassion, PsyCap, social support, and relationship satisfaction on first responders’ well-being and ultimately on health. The findings further indicate that social support, relationship satisfaction, physical activity, and well-being have a significant relationship with first responder’s health. These findings point to the utility of positive psychology interventions with first responders. The findings in particular point to the utility of a multicomponent, multifaceted approach to all levels of prevention and intervention. There is existing evidence that interventions based on self-compassion, social support, hope, self-efficacy, optimism, and relationship building individually help to build resilience and enhance coping in the face of stress. What the current study points to is the use of interventions that focus on all these levels as appropriate. Future research should attempt to test the causal relations in the tentative model herein in longitudinal research and test the efficacy of multifaceted interventions as indicated. In addition, future research could include measures of the coworker and organizational support as these are likely to add something to the explained variance.

References

- Adams, R. G., & Blieszner, R. (1995). Aging well with friends and family. American Behavioral Scientist, 39(2), 209–224. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764295039002008

- Antonovsky, A. (1987). Unraveling the mystery of health: How people manage stress and stay well. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Antonovsky, A. (1996). The salutogenic model as a theory to guide health promotion. Health Promotion International, 11(1), 11–18. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/11.1.11

- Arble, E., & Arnetz, B. B. (2017). A model of first-responder coping: An approach/avoidance bifurcation. Stress and Health, 33(3), 223–232. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.2692

- Avey, J. B., Luthans, F., Smith, R. M., & Palmer, N. F. (2010). Impact of positive psychological capital on employee well-being over time. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 15(1), 17–28. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016998

- Benedek, D. M., Fullerton, C., & Ursano, R. J. (2007). First responders: Mental health consequences of natural and human-made disasters for public health and public safety workers. Annual Review of Public Health, 28, 55–68. doi:https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.publhealth.28.021406.144037

- Bowling, A. (2005). Just one question: If one question works, why ask several? Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 59(5), 342–345. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2004.021204

- Carr, D. & Springer, K. W. (2010). Advances in families and health research in the 21st century. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 72(3), 743–761. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00728.x

- Chida, Y., & Steptoe, A. (2008). Positive psychological well-being and mortality: A quantitative review of prospective observational studies. Psychosomatic Medicine, 70(7), 741–756. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0b013e31818105ba

- Cronbach, L. J. (1951). Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika, 16(3), 297–334. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02310555

- Dahlem, N. W., Zimet, G. D., & Walker, R. R. (1991). The multidimensional scale of perceived social support: A confirmation study. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 47(6), 756–761. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-4679(199111)47:6<756::AID-JCLP2270470605>3.0.CO;2-L

- de Assis, M. A., de Mello, M. F., Scorza, F. A., Cadrobbi, M. P., Schooedl, A. F., Gomes da Silva, S., … Arida, R. M. (2008). Evaluation of physical activity habits in patients with posttraumatic stress disorder. Clinics, 63(4), 473–478. doi:https://doi.org/10.1590/S1807-59322008000400010

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2008). Hedonia, eudaimonia, and well-being: An introduction. Journal of Happiness Studies, 9(1), 1–11. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-006-9018-1

- Diener, E. (2000). Subjective well-being: The science of happiness and a proposal for a national index. American Psychologist, 55(1), 34–43. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.34

- Diener, E., & Chan, M. Y. (2011). Happy people live longer: Subjective well‐being contributes to health and longevity. Applied Psychology: Health and Well‐Being, 3, 1–43. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1758-0854.2010.01045.x

- Farmer, M. E., Locke, B. Z., Mościcki, E. K., Dannenberg, A. L., Larson, D. B., & Radloff, L. S. (1988). Physical activity and depressive symptoms: The NHANES I Epidemiologic Follow-up Study. American Journal of Epidemiology, 128(6), 1340–1351. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115087

- Fullerton, C. S., Ursano, R. J., & Wang, L. (2004). Acute stress disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, and depression in disaster or rescue workers. American Journal of Psychiatry, 161(8), 1370–1376. doi:https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.161.8.1370

- Geronazzo-Alman, L., Eisenberg, R., Shen, S., Duarte, C. S., Musa, G. J., Wicks, J., … Hoven, C. W. (2017). Cumulative exposure to work-related traumatic events and current post-traumatic stress disorder in New York City’s first responders. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 74, 134–143. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2016.12.003

- Hendrick, S. S., Dick, A., & Hendrick, C. (1998). The relationship assessment scale. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 15(1), 137–142. . doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407598151009

- Holt-Lunstad, J. (2017). Friendship and health. In M. Hojjat & A. Moyer (Eds.), The psychology of friendship (p. 233–248). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Holt-Lunstad, J., Smith, T. B., & Layton, J. B. (2010). Social relationships and mortality risk: A meta-analytic review. PLoS Medicine, 7(7), e1000316. doi:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000316

- Homan, K. J., & Sirois, F. M. (2017). Self-compassion and physical health: Exploring the roles of perceived stress and health-promoting behaviors. Health Psychology Open, 4(2), 205510291772954. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/2055102917729542

- Hourani, L. L., Davila, M. I., Morgan, J., Meleth, S., Ramirez, D., Lewis, G., … Lewis, A. (2020). Mental health, stress, and resilience correlates of heart rate variability among military reservists, guardsmen, and first responders. Physiology & Behavior, 214, 112734. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2019.112734

- Howell, R. T., Kern, M. L., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2007). Health benefits: Meta-analytically determining the impact of well-being on objective health outcomes. Health Psychology Review, 1(1), 83–136. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17437190701492486

- Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6(1), 1–55. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

- Jones, S. (2017). Describing the mental health profile of first responders: A systematic review. Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurses Association, 23(3), 200–214. Doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1078390317695266

- Kamp Dush, C. M., & Taylor, M. G. (2012). Trajectories of marital conflict across the life course: Predictors and interactions with marital happiness trajectories. Journal of Family Issues, 33(3), 341–368.

- Kamp Dush, C. M., Taylor, M. G., & Kroeger, R. A. (2008). Marital happiness and psychological well-being across the life course. Family Relations, 57(2), 211–226. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3729.2008.00495.x

- Kansky, J. (2018). What’s love got to do with it?: Romantic relationships and well-being. In E. Diener, S. Oishi, & L. Tay (Eds.), Handbook of well-being. Salt Lake City, UT: DEF Publishers.

- Kirschner, H., Kuyken, W., Wright, K., Roberts, H., Brejcha, C., & Karl, A. (2019). Soothing your heart and feeling connected: A new experimental paradigm to study the benefits of self-compassion. Clinical Psychological Science, 7(3), 545–565. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/2167702618812438

- Kleim, B., & Westphal, M. (2011). Mental health in first responders: A review and recommendation for prevention and intervention strategies. Traumatology, 17(4), 17–24. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1534765611429079

- Kline, R. B. (2015). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (4th ed.). Ann Arbor, MI: ProQuest.

- Kwak, S. K., & Kim, J. H. (2017). Statistical data preparation: Management of missing values and outliers. Korean Journal of Anesthesiology, 70(4), 407–411. doi:https://doi.org/10.4097/kjae.2017.70.4.407

- Lavner, J. A., & Bradbury, T. N. (2010). Patterns of change in marital satisfaction over the newlywed years. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 72(5), 1171–1187. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00757.x

- Lin, S., Faust, L., Robles-Granda, P., Kajdanowicz, T., & Chawla, N. V. (2019). Social network structure is predictive of health and wellness. PLoS One, 14(6), e0217264. doi:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0217264

- Lorenz, T., Beer, C., Pütz, J., & Heinitz, K. (2016). Measuring psychological capital: Construction and validation of the Compound PsyCap Scale (CPC-12). PLoS One, 11(4), e0152892. doi:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0152892

- Luthans, F., Avolio, B. J., Avey, J. B., & Norman, S. M. (2007). Positive psychological capital: Measurement and relationship with performance and satisfaction. Retrieved from http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/leadershipfacpub/11

- Luthans, F., Youssef, C. M., Sweetman, D. S., & Harms, P. D. (2013). Meeting the leadership challenge of employee well-being through relationship PsyCap and health PsyCap. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 20(1), 118–133. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1548051812465893

- Luthans, F., & Youssef-Morgan, C. M. (2017). Psychological capital: An evidence-based positive approach. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 4(1), 339–366. doi:https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032516-113324

- Lyubomirsky, S., King, L., & Diener, E. (2005). The benefits of frequent positive affect: Does happiness lead to success? Psychological Bulletin, 131(6), 803–855. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.131.6.803

- Marmar, C. R., McCaslin, S. E., Metzler, T. J., Best, S., Weiss, D. S., Fagan, J., … Neylan, T. (2006). Predictors of posttraumatic stress in police and other first responders. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1071(1), 1–18. doi:https://doi.org/10.1196/annals.1364.001

- Marshall, A. L., Smith, B. J., Bauman, A. E., & Kaur, S. (2005). Reliability and validity of a brief physical activity assessment for use by family doctors. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 39(5), 294–297. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsm.2004.013771

- McKeon, G., Steel, Z., Wells, R., Newby, J. M., Hadzi-Pavlovic, D., Vancampfort, D., & Rosenbaum, S. (2019). Mental health informed physical activity for first responders and their support partner: A protocol for a stepped-wedge evaluation of an online, codesigned intervention. British Medical Journal, 9(9), e030668. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-030668

- Merz, E.-M., Consedine, N. S., Schulze, H.-J., & Schuengel, C. (2009). Well-being of adult children and ageing parents: Associations with intergenerational support and relationship quality. Ageing and Society, 29(5), 783–802. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X09008514

- Meyer, T., & Broocks, A. (2000). Therapeutic impact of exercise on psychiatric diseases: Guidelines for exercise testing and prescription. Sports Medicine, 30(4), 269–279. doi:https://doi.org/10.2165/00007256-200030040-00003

- Mittelmark, M. B., & Bauer, G. F. (2017). The meanings of salutogenesis. In: M. Mittelmark (Ed.), The handbook of salutogenesis. Cham, Switzerland: Springer.

- Neff, K. D. (2003). Self-compassion: An alternative conceptualization of a healthy attitude toward oneself. Self and Identity, 2(2), 85–101. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/15298860390129863

- Neff, K. D. (2016). The self-compassion scale is a valid and theoretically coherent measure of self-compassion. Mindfulness, 7(1), 264–274. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-015-0479-3

- Neff, K. D., & Germer, C. (2017). Self-compassion and psychological well-being. In J. Doty (Ed.) Oxford handbook of compassion science. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Neff, K. D., & Knox, M. (2017). Self-compassion. In V. Zeigler-Hill & T. Shackelford (Eds.), Encyclopaedia of personality and individual differences. New York, NY: Springer.

- Ozbay, F., Johnson, D. C., Dimoulas, E., Morgan, C. A., Charney, D., & Southwick, S. (2007). Social support and resilience to stress: From neurobiology to clinical practice. Psychiatry, 4(5), 35–40.

- Pateraki, E., & Roussi, P. (2013). Marital quality and well-being: The role of gender, marital duration, social support and cultural context. In A. Michalos (Ed.), Social indicators research series (pp. 125–145). Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Springer.

- Pedersen, J. E., Ugelvig Petersen, K., Ebbehøj, N. E., Bonde, J. P., & Hansen, J. (2018). Incidence of cardiovascular disease in a historical cohort of Danish firefighters. Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 75(5), 337–343. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/oemed-2017-104734

- Pietrantoni, L., & Prati, G. (2008). Resilience among first responders. African Health Sciences, 8(S), 14–20.

- Prati, G., & Pietrantoni, L. (2010). The relation of perceived and received social support to mental health among first responders: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Community Psychology, 38(3), 403–417. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.20371

- Raes, F., Pommier, E., Neff, K. D., & Van Gucht, D. (2011). Construction and factorial validation of a short form of the self-compassion scale. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 18(3), 250–255. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.702

- Roberson, P. N. E., Norona, J. C., Lenger, K. A., & Olmstead, S. B. (2018). How do relationship stability and quality affect well-being? Romantic relationship trajectories, depressive symptoms, and life satisfaction across 30 Years. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 27(7), 2171–2184. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-018-1052-1

- Ruegsegger, G.N., & Booth, F.W. (2018). Health benefits of exercise. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in medicine, 8(7), a029694. doi:https://doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a029694

- Ryff, C. D., & Keyes, C. L. M. (1995). The structure of psychological well-being revisited. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69(4), 719–727. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.69.4.719

- Schnurr, P. P., & Spiro, A., III. (1999). Combat disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms and health behaviors as predictors of self-reported physical health in older veterans. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 187(6), 353–359.

- Sebern, M., & Riegel, B. (2009). Contributions of supportive relationships to heart failure self-care. European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, 8(2), 97–104. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejcnurse.2008.07.004

- Shor, E., Roelfs, D. J., & Yogev, T. (2013). The strength of family ties: A meta-analysis and meta-regression of self-reported social support and mortality. Social Networks, 35(4), 626–638. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socnet.2013.08.004

- Stanley, I. H., Hom, M. A., & Joiner, T. E. (2016). A systematic review of suicidal thoughts and behaviors among police officers, firefighters, EMTs, and paramedics. Clinical Psychology Review, 44, 25–44. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2015.12.002

- Superko, H. R., Momary, K. M., Pendyala, L. K., Williams, P. T., Frohwein, S., Garrett, B. C., … Polite, S. (2011). Firefighters, heart disease, and aspects of insulin resistance. The FEMA firefighter heart disease prevention study. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 53(7), 758–7641.

- Tennant, R., Hiller, L., Fishwick, R., Platt, S., Joseph, S., Weich, S., … Stewart-Brown, S. (2007). The Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (WEMWBS): Development and UK validation. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 5, 63. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-5-63

- Thomas, P. A., Liu, H., & Umberson, D. (2017). Family relationships and well-being. Innovation in Aging, 1(3), igx025. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/geroni/igx025

- Uchino, B. N. (2006). Social support and health: A review of physiological processes potentially underlying links to disease outcomes. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 29(4), 377–387. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-006-9056-5

- van der Horst, M., & Coffé, H. (2012). How friendship network characteristics influence subjective well-being. Social Indicators Research, 107(3), 509–529. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-011-9861-2

- Varvarigou, V., Farioli, A., Korre, M., Sato, S., Dahabreh, I. J., & Kales, S. N. (2014). Law enforcement duties and sudden cardiac death among police officers in United States: Case distribution study. British Medical Journal, 349, 6534.

- Vaughn, M., & Matyastik Baier, M. E. (1999). Reliability and validity of the relationship assessment scale. The American Journal of Family Therapy, 27(2), 137–147. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/019261899262023

- Viswesvaran, C., Sanchez, J. I., & Fisher, J. (1999). The role of social support in the process of work stress: A meta-analysis. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 54(2), 314–334. doi:https://doi.org/10.1006/jvbe.1998.1661

- Wanous, J. P., & Reichers, A. E. (1996). Estimating the reliability of a single-item measure. Psychological Reports, 78(2), 631–634. doi:https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1996.78.2.631

- Warren, R., Smeets, E., & Neff, K. D. (2016). Self-criticism and self-compassion: Risk and resilience for psychopathology. Current Psychiatry, 15(12), 18–32.

- WHO. (2020). World health statistics 2020: Monitoring health for the SDGs, sustainable development goals. Geneva: World Health Organization. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- Youssef-Morgan, C. M., & Luthans, F. (2015). Psychological capital and well-being. Stress and Health, 31(3), 180–188. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.2623

- Zessin, U., Dickhäuser, O., & Garbade, S. (2015). The relationship between self- compassion and well-being: A meta-analysis. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being, 7(3), 340–364. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/aphw.12051

- Zimet, G. D., Powell, S. S., Farley, G. K., Werkman, S., & Berkoff, K. A. (1990). Psychometric characteristics of the Multidimensional Scale of perceived social support. Journal of Personality Assessment, 55(3–4), 610–617.