Abstract

This study investigated employees’ perceptions of incorporating traditional health practitioners’ services in employee assistance programmes in the South African context. A qualitative approach was used in which 49 participants completed a qualitative online questionnaire to share their perceptions. The study’s findings revealed that the wellness needs of African employees in the workplace were not being met; that employees were not aware of African traditional health practitioners’ services available on their company’s employee assistance programmes; and indicated the services of African traditional health practitioners that employees would like to be included in their company’s employee assistance programmes. These findings point to the need for organizations to provide more diverse and inclusive services through their employee assistance programmes.

Introduction

Historically, due to colonization and apartheid, traditional health practitioners (THPs) have been sidelined in South Africa. However, in the past decade, there has been a resurgence of interest in THPs’ methods as practised by indigenous South Africans (Peltzer & Khoza, Citation2002). This resurgence has been driven by the increase in the discourse about African’s valuing and loving who they are and decolonizing themselves from Western thoughts and beliefs. In public discourse, more individuals have spoken up about being izangoma or izinyanga, including celebrities, such as radio personality and actor Treasure Tshabalala, female hip-hop artist Boitumelo Thulo, actresses Dineo Langa, Letoya Makhene, and Lerato Mvelase, actors Zola Hashatsi and Bongani Masondo, musical artist Phelo Bala and singer Buhle Mda (eNCA, Citation2019). Radio and television shows have also included programming where THPs and cultural experts are interviewed to educate their audiences about African traditions and cultures (MetroFM, Citation2018). Traditional health practitioners are also engaging publicly on traditional health practices on social media, such as Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, and YouTube. The Statistics South Africa General Household Survey (2018) indicates that there has been an increase in the use of THPs in the country between 2002 and 2014, the highest it has been in 14 years (StatsSA, Citation2018). Previously, it was reported that traditional medicine is used by 80% of South Africans to satisfy their primary health-care needs (Mbatha, Street, Ngcobo, & Gqaleni, Citation2012).

Although the workplace has been transformed immensely since democracy in South Africa, where 91% of the South African workforce are black people of which 78,8% are African (CEE, Citation2019), little has been done to accommodate the wellness needs of this diverse workforce (Govender & Vandayar, Citation2018). For many black South Africans, especially Africans, the existing model of employee assistance programmes (EAPs) in the country has inadequately incorporated and addressed cultural aspects of spirituality, such as the importance of ancestors (Maynard, Citation2017), with very few organizations accommodating African cultural beliefs. For example, the University of KwaZulu-Natal (UKZN) has a THP on its staff and student counseling and wellness programme. The University of Pretoria accepts sick notes from a registered THP. Sun International and the Chamber of Mines have a similar agreement with employees granted three days’ leave to consult a traditional healer. (Mbatha et al., Citation2012). Govender and Vandayar (Citation2018) also report that some EAPs have started to reach out to THP associations when dealing with issues of employees undergoing intwaso, a traditional initiation to become a THP.

The existing model of EAPs follows modern allopathic medicine and modern psychology that are influenced by the Western approach to knowledge and do not recognize the cultural difference that is typical of a multicultural country, such as South Africa. For example, in general, EAPs are composed of social workers, human resource specialists, and occupational health practitioners (Govender & Vandayar, Citation2018; Willemse, Citation2018). In South Africa, these specialists and practitioners have studied at higher education institutions that have imprinted a Western praxis, which has resulted in the neglect of African knowledge and identity (Plaatjie, Citation2021). In addition, over the past few years, the lack of therapeutic models capable of accommodating all cultures are being recognized as a limitation on the impact of counseling (EAPA-SA, Citation2022; Madlingozi, Citation2019). Scholars, such as Asante (Citation1991, Citation2014), Chawane (Citation2016), and Dei (Citation1994) argue that Eurocentricity focuses on the European ways of doing and experiences as the universal truth. Therefore, it is possible that the wellness needs of employees from traditional African backgrounds are not adequately being provided for in several EAPs (Bomoyi, Citation2011). It is against this backdrop that this study sought to answer the research question “What are South African employees’ perceptions of incorporating traditional health practitioners’ services in employee assistance programmes?”

Literature review

Traditional African belief views wholeness and good health as being in a harmonious relationship with the local ecosystem of animals, plants, the elements, and other individuals (living or dead), as well as with the universe (Ajima & Ubana, Citation2018; Omonzejele, Citation2008; Shizha & Charema, Citation2011). As such, health is not only the absence of disease but also includes a person’s ability to operate within their context whereas a deterioration in the social relations makes a person susceptible to ill health. Therefore, to be in good health, an individual must ensure a balance between the physical, social, mental, familial, and spiritual realms of life (Bomoyi, Citation2011). The traditional view of self, health, and illness is thus different from the individualistic Western perspective in which an individual is responsible for their own health (Bomoyi, Citation2011).

Defining traditional health practices

Traditional health practices are heterogeneous and differ from one region to another and from one culture to another (Gessler et al., Citation1995; Mokgobi, Citation2014). These traditional health practices are well established and organized in certain countries, such as China and India, however, not so much in countries, such as South Africa (Mokgobi, Citation2014). However, traditional medicine is the oldest form of medicine; it is an essential part of African and other indigenous societies and is used for both mental and physical aspects of sickness (Bomoyi, Citation2011). Traditional health practices focus on creating an alignment between the body and the mind (Lichtenstein, Berger, & Cheng, Citation2017; Sandlana & Mtetwa, Citation2008). According to UNAIDS (Citation2006), it encompasses using herbs on the one hand to spiritual treatment on the other, thus making it a holistic and integrated approach drawing from the collective wisdom of indigenous knowledge handed down through generations.

Traditional health practitioners and their work

According to Sandlana and Mtetwa (Citation2008), a traditional healer is defined as an individual recognized by their community as an expert in providing health care using plants, animals, and other methods based on the beliefs, knowledge of religion, and culture of that community to address mental, physical, social well-being and causes of illness and disability. Traditional healers are included in the South African Traditional Health Practitioners Act 22 of 2007 as health professionals. They provide an array of divination, counseling, and medical services (Mokgobi, Citation2014), find lost objects or lost people, and establish direct contact with the ancestors and the supernatural (Cumes, Citation2013).

The Traditional Health Practitioners Act of 2007 recognizes four different types of traditional healers in South Africa. For the purposes of this study, three categories of traditional healers—isangoma (the diviner), inyanga (the herbalist), and umthandazi (the African religious faith healer)—are discussed as they seem to be working directly with people on their daily health, including mental and emotional issues similar to the services offered by EAPs.

Firstly, the role of isangoma is to diagnose illness as they specialize in explaining the causes of events. They use their tools and the spirits of their ancestors to diagnose and prescribe medication for a variety of physiological, psychiatric, and spiritual conditions (Bomoyi, Citation2011; Mokgobi, Citation2014), and also interpret dreams. Through the throwing of bones, isangoma communicates directly with ancestors. By using their supernatural abilities, they can distinguish ancestral illnesses from non-ancestral illnesses and their respective treatments (Ndlovu, Citation2016). There are also specialist sangomas who practice ukufemba, which is equated with a psycho-spiritual surgery that rids the patient of intruding spirits. A sangoma channels their own ancestors to connect with their client’s ancestors to relay the necessary information and in the case of ukufemba, the sangoma connects with the intruding spirit possessing the client (Cumes, Citation2013). The focus of isangoma is to diagnose the unexplainable, especially among Western doctors (Kubeka, Citation2016). To become isangoma, an individual undergoes a training period called ukuthwasa in which traditional healing fundamentals are taught (Ndlovu, Citation2016). During the training, isangoma learns how to throw and read bones and control the trance-like state where communication with the ancestral spirits takes place (Kubeka, Citation2016).

Secondly, inyanga is an authority on herbs, plants, and traditional therapeutic interventions (Zuma, Wight, Rochat, & Moshabela, Citation2016). In addition to diagnosing and prescribing herbs, medication, and enemas for a variety of ailments, inyanga is also credited with preventing witchcraft, bringing prosperity and happiness, and protecting against witchcraft (Ross, Citation2010). They produce medicines through access to their ancestors (Bomoyi, Citation2011) and interpret dreams. Isangoma frequently refers patients to them for healing, and they use their medicinal expertise to complete the process. Despite their specialization in certain illnesses, such as snake poison or mental illness, inyanga is generally capable of healing any illness they come across. They undergo several years of apprenticeship under renowned healers to enhance their competence (Ndlovu, Citation2016).

Lastly, umthandazi (faith healer) is a professed Christian belonging to a traditional African church. They use water, prayer, ash, and touching to heal patients (Bomoyi, Citation2011; McFarlane, Citation2015). In addition to herbs, remedies, and holy water, umthandazi often use religious symbols to encourage and exhort, offering hope to those who are afflicted (Ndlovu, Citation2016). Through prayer, Bible reading, and singing, umthandazi invokes spiritual energy (umoya) (Kubeka, Citation2016). It is believed that the healing powers of umthandazi come from God and are a combination of the spirits of the ancestors and the Christian Holy Spirit. Amthandazi describes healing in terms of three levels of consciousness, namely arising in the unconscious, in conscious awareness, and through consciousness, for example, trauma or anxiety (Kubeka, Citation2016). Like isangoma, umthandazi may also go through a training period which includes going through purification rituals in rivers, mountains, and oceans (Kubeka, Citation2016).

Employee assistance programmes

According to Soeker et al. (Citation2015), an EAP is a set of company policies and procedures that is used to identify or respond to employees’ emotional or personal problems which, directly or indirectly, affect job performance. EAPs assist employees in coping with the stresses they face at work or at home. According to the EAPA-SA (Citation2015), the role of employee assistance is to enhance employee and workplace wellness through prevention, identification, and resolution of personal and productivity issues using core technologies. These core technologies include training and development, marketing, case management, consultation with work organizations, stakeholder management, and monitoring and evaluation.

The concept of EAPs began in the United States of America (USA) and over time it has transformed to include a broader range of issues regarding employees and workplace health and well-being (Roche et al., Citation2018; Willemse, Citation2018). EAPs have been adopted by different countries and adapted from the original format. They have evolved from a one-size-fits-all format to one that appreciates and addresses the cultural uniqueness of different regions. South African EAPs differ from the original American format as the former have been shaped by the need to address the impact of the HIV/AIDS pandemic; the transformation issues driven by the dynamic political changes; organizational development; occupational health and safety; and other issues outside of the traditional focus on psychosocial issues experienced by employees (Willemse, Citation2018). Currently, EAPs exist in almost all industries including medium and large organizations in South Africa, and are mandatory in the public service (Maynard, Citation2017). The EAPs in South Africa are complex and sophisticated, having transformed from social welfare and occupational social work, to include human resource management, occupational health, and the mental and medical fields. Many organizations prefer a hybrid model in combining elements of internal and external service providers because external service providers provide an extended offering that includes financial, legal, health, ergonomics, disability management, counseling, and absenteeism advice. The EAPs adopt a proactive approach to employee wellness through health screening and testing, wellness education, as well as a reactive risk-management approach to employee support and counseling (Govender & Vandayar, Citation2018).

Theoretical framework

This study employed the transformative paradigm to investigate important issues in including traditional healers in EAPs. The transformative paradigm is useful when a researcher is investigating issues in which people are born into situations of oppression and discrimination because of historical, physical, economic, or other factors. Mertens (Citation2009) describes the transformation theory as an umbrella term that includes paradigmatic perspectives that are aimed at being inclusive, participatory, and emancipatory. It is in response to individuals who have been marginalized throughout history and continue to face limited access to resources (Mertens, Citation2009). The African worldview maintains that African culture should be at the center of research involving African participants and accepts the interconnectedness of people (Asante, Citation1991). Placing African culture at the center of this study was key because this study is culture-specific. Scholars have pointed out that researchers often use Western methodologies in non-Western research (Mkabela, Citation2005; Reviere, Citation2001).

Methods

Research approach and design

This study used a qualitative research approach with an exploratory and descriptive research design. The qualitative research approach provides a wide range of detailed descriptions of participants’ feelings, opinions, and experiences; and explains the meanings of their actions (Denzin, Citation1989; Saunders & Lewis, Citation2018).

Sampling

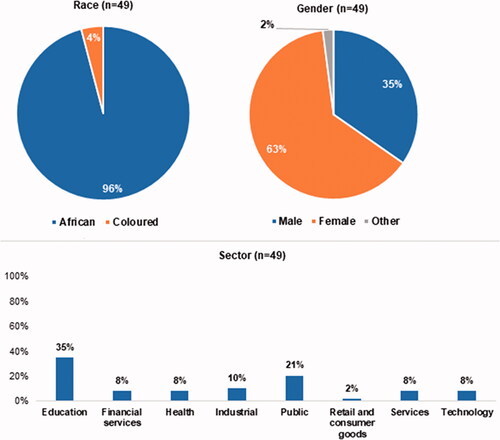

Convenience river sampling was used to recruit participants online. The idea of river sampling describes the way researchers dip into the traffic flow of a website, catching some of the users floating by Lehdonvirta, Oksanen, Räsänen, and Blank (Citation2021). Convenience sampling is characterized by a nonsystematic approach to recruiting respondents that often allows a potential respondent to self-select into the sample (Jang & Vorderstrasse, Citation2019). A passive online participant recruitment method using an online flyer was used to recruit participants (Gelinas et al., Citation2017; McInroy, Citation2016). This method was beneficial for obtaining samples from the public for research on delicate subjects, such as for soliciting individuals’ perceptions of traditional healers (Harris, Loxton, Wigginton, & Lucke, Citation2015). A multimodal recruitment strategy using LinkedIn, Twitter, and Facebook was employed. This approach sought to minimize geographical barriers and allow participants from across the country, industries, ages, and backgrounds to be successfully recruited (McRobert, Hill, Smale, Hay, & van der Windt, Citation2018). A sample of 49 participants was achieved. shows the racial, gender, and industry breakdown of the participants. It was not surprising that most of the participants were African because studies suggest that up to 80% of black South Africans consult traditional healers (Boum, Kwedi-Nolna, Haberer, & Leke, Citation2021; Mncube, Citation2021). Additionally, research by Ramulondi, De Wet, and Ntuli (Citation2022) and Shewamene, Dune, and Smith (Citation2017) shows that due to the deep-rooted cultural trust in THPs and traditional medicine, African women usually prefer THPs to biomedical healthcare professionals.

Figure 1. Racial, gender, and employment industry breakdown of participants. Coloured refers to the mixed racial group in South Africa (Petrus & Isaacs-Martin, Citation2012).

Data collection and analysis

An online structured qualitative questionnaire was used to collect the data. Participants were asked seven questions. The questions related to (1) participants’ opinions on whether the wellness needs of African employees were well catered for in their organizations, (2) the main challenges of providing wellness services to African employees in the workplace, (3) knowledge of the existence of THP services in the EAPs in their organizations, (4) suggestions of the THP services they felt should be included in the EAP suite of services in their organizations, (5) the advantages and challenges of including THP services in the EAPs in their organizations, and (6) their recommendations on the inclusion of THP services in EAPs. The questions were used as the data analysis framework. The data were analyzed thematically using Braun and Clarke's (Citation2013) six-step process. The first step was skipped because there was no need for transcription of the participants’ responses. Therefore, the following steps were followed. Firstly, the participants’ responses were read and re-read to determine items of interest. Secondly, the coding process was followed to identify latent and obvious content. Thirdly, codes were examined to determine if any trends emerged. Fourthly, the themes were chosen and assessed in line with the aim of the study in mind. Lastly, the emerging themes were named. The holistic collective method of data analysis was used (Mkabela, Citation2005). This analysis method requires the researcher to be culturally sensitive and accepting of different participants’ views.

Ethical considerations

Before data collection, the study was approved by the Ethics Review Committee of the Unisa College of Education (2021/06/09/90179617/10/AM). This study was conducted in line with ethical research practices, including ensuring participants provided informed consent to participate in the study, assuring participants of their right to withdraw from the study at any time, and assuring them of their anonymity and confidentiality.

Findings

Six themes were derived from the data.

Lack of accommodation of THP services in EAP

Most of the participants stated that the wellness needs of African employees were not well catered for in their organizations and they indicated that their organizations did not have African traditional healing services as part of their EAPs.

“No. Wellness programmes do not include other cultural norms of the vast majority of South Africans” (P6, African, male)

“No they aren’t.” (P14, Coloured, female)

Key challenges of providing THP services to African employees in EAP

There were four subthemes that were evident in this theme. These were:

Participants raised the concern that there was limited knowledge of THPs’ healing methodologies:

“Lack of knowledge and information is a huge challenge when it comes to providing wellness services to African employees. Understanding our African background allows proper diagnosis and assistance, which is lacking in the Western approach” (P20, African, male)

“There is very limited understanding of Africanism and roots of African people. Just that creates barriers in our livelihood at work and brings hidden conflict and misunderstandings and non-compromise. Employees are disciplined harshly. when other measures could have been taken to support them” (P1, African, female)

Participants indicated that there was a lack of recognition of THPs’ healing methodologies:

“The services of traditional healers in the workplace are not recognised in terms of the policy design and implementation” (P4, African, female)

“The ignorance of traditional healing and methods to address wellness, these are not acknowledged and accepted by the employer and therefore are non-existent/excuses from the employers’ perspective” (P38, African, female)

The prevailing negative perceptions of THPs’ healing methodologies were raised by participants:

“If you indulge in them, you are thought to be a witch old fashioned and down-right stupid. You are treated with suspicion.” (P3, African, female)

“The challenge is that employers don’t openly support this. And it’s still seen as a taboo. People that do consult traditional healers want to do it in secret and don’t want it to be known. If you openly voice out that you consult traditional healers you will be seen as a witch or a person that goes there to bewitch people. Whereas you consult for your own well-being and to know and hear from one’s ancestors when you are troubled or having spiritual problems” (P9, African, female)

Participants also voiced the fact that there was more focus on the Western perspective of managing employees in organizations:

“Eurocentricity of HR policies.” (P9, African, female)

“Viewing wellness only from a Western perspective” (P25, African, female)

Recommendations for the THPs’ services to be included in the EAP

Participants recommended that prophetic healers and izinyanga/izangoma (traditional healers) should be included in EAP.

“I think I would add prophets as it incorporates African traditional spirituality and religion” (P18, African, male)

“Consulting with traditional doctors/practitioners” (P6, African, male)

“Referrals to Sangomas, Traditional church prophets (bo mamosebeletsi) and such” (P2, African, male)

Advantages of including THPs in the EAP

The participants indicated that by including THPs in EAPs, there would be an inclusive and holistic view of wellness and it would also reduce the stigma associated with traditional practices.

“It would make the wellness provided more holistic and inclusive” (P5, African, male)

“More people will be open to the idea. Making those who are already following the traditional healing route feel less isolated” (P33, African, male)

The challenges of including THPs in the EAP

Participants raised four main challenges with regard to including African THPs in EAPs. Participants stated that finding good and credible African traditional healers to include in EAPs would be a challenge:

“… getting credible healers involved in the programme” (P23, African, female)

“Getting good certified healers willing to enter into an employment contract. Policy drafting will also be a barrier” (P44, African, female)

Participants stated that developing a human resource management policy to include THPs in EAPs would be challenging:

“The HR processes are more inclined in accepting Western norms than an African perspective about the way things work” (P4, African, female)

“The design and implementation of such policies are time consuming” (P5, African, male)

The issue of stigmatization of employees for using THP services was also raised as a challenge:

“Stigmatisation and getting credible healers involved in the programme” (P22, African, male)

“I think they may not be understood, generally, people go and consult but they do not often speak openly about this. A lot of shaming still is associated by the society.” (P42, African, female)

Recommendations for the inclusion of THP services in EAPs

The participants indicated that they supported the inclusion of THP services in EAPs:

“I totally support this. Traditional healers are multidisciplinary in their approach and would add great value and new perspectives in EAP services. Some employees are traditionally ill but seek Western solutions because that is what employers are willing to fund and pay for” (P24, African, female)

“It should be a critical part in the EAP system as it would assist in healing processes of employees. It would also form part of cultural diversity programmes in the corporate and public sector” (P29, African, Male)

To facilitate the inclusion of THP services in the EAPs, participants indicated that organizations would need to conduct education and awareness of THP services available in EAPs to employees and management:

“Educating personnel about it to ensure that we are all on the same footing. It is difficult at times for colleagues to be integrated back to the office space after initiation” (P43, African, female)

“First we need to educate everyone as simply including traditional services will not cut it. To some they will add just because the law says so” (P34, African, female)

Discussion

This study sought to investigate South African employees’ perceptions of including THP services in EAPs. We found that participants had positive perceptions about the inclusion of THP services in EAPs. They indicated that traditional African employees’ wellness needs were not adequately catered for in their organizations’ EAPs and felt that this should change. The participants raised their concerns about the Eurocentric nature of managing employees in South African organizations, which did not recognize or accommodate the African way of viewing individuals. This was because of the limited knowledge, perceptions, and recognition of THPs’ healing methodologies.

The participants mentioned some advantages of including THP services in EAPs, which included having an inclusive and holistic view of wellness in organizations and by the fact that the inclusion of THP services in EAPs would reduce the stigma associated with THPs and their services and the use thereof. Although there were some advantages associated with including THP services in EAPs, participants pointed out some challenges in this regard. These included finding credible THPs to include in EAPs, the challenges associated with developing a human resource management policy to include THPs in EAPs due to the Eurocentric nature of South African organizations, and the fact that the process to develop a policy would be time-consuming.

Participants were emphatic about the benefits of including THP services in EAPs: they were of the view that South African organizations should include THP services in EAPs because as it would cater to the employees who feel left behind and are constantly searching for a sense of belonging in their well-being at work. Thus, the inclusion of THP services would contribute to EAPs providing a holistic wellness programme that caters to a diverse workforce as in South Africa. Therefore, the participants indicated that organizations would need to conduct education and awareness initiatives about the THPs and the services that are available in the EAPs.

Conclusion

To date, little research has been conducted on employees’ perceptions of including THP services in EAPs in South Africa. Therefore, the purpose of the study was to investigate employees’ perceptions of including THP services in EAPs in South Africa with the aim of highlighting this crucial human right service in attending to the diverse needs of the South African workforce. The study’s findings showed that there is a need for employers to include the services of THPs in EAPs; this is viewed as being inclusive and acknowledging the African context that they operate in as most of the workers are African. THPs have much to offer South African workers if they are given recognition and importance in the workplace. Traditional health practices and methodologies have survived for many years despite the constant pressure by Westerners to abandon it in favor of Western healing practices. If it had no merit, it would not have lasted through the burdens of time and prejudice against it. It is time for South African employers to open their minds to a new type of treatment. The implications of this study’s findings for employers include the fact that diversity and inclusion practices and strategies need to extend beyond just the racial, gender, and age elements of diversity. Employers also need to ensure that they provide diverse employee support services to meet the needs and expectations of their diverse workforce. This would have a positive effect organizations’ and employers’ branding and psychological contract with their employees.

These findings also have implications for policy in that section 23 of the Basic Conditions of Employment Equity Act (BCEA) 75 of 1997 (Republic of South Africa, Citation1997) requires THPs to be registered with the Traditional Health Practitioners Council of South Africa to issue valid medical certificates. However, the interim Traditional Health Practitioners Council established in 2014 does not appear to be functioning yet. Although the Department of Health provided a written reply in June 2020 to Parliament that the department is in the process of integrating THPs as registered health practitioners (Parliamentary Monitoring Group, Citation2020), the absence of the registry with a list of registered THPs poses a challenge for employers as they are not able to determine whether a THP is registered or not. Therefore, the government needs to take the necessary action to address this gap as South Africans are prepared to use THP services in EAPs, which would also enable employers to take the necessary steps to include more diverse services in their EAPs.

This article addressed one of the sensitive topics in the field of psychology and EAP where the majority workforce despite the level in South Africa is the black people whom EAP ought to consider in its core practice, yet this is not happening. Thus, this topic is envisaged to contribute to the employee understanding, equipping and empowering counselors and thus contributing to richer and accessible EAP programmes through the official inclusion of THP policy in the workplace and thus serve the previously marginalized workforce. EAP staff should initiate the revision of policy and operational guidelines for the inclusion of THPs. Active recruitment of suitable practitioners to represent THPs in the workplace should be done by the management of corporate companies, EAP service providers, and EAPA-SA Board as the representative body for the EAP fraternity. Training institutions should promote the concept of THPs in training offered in the EAP and wellness fields.

Recommendations regarding future research

Exploration of the views of respondents regarding the different types of traditional healing could have added value to the study and should be considered in future research efforts. Additionally, a sample of EAP coordinators, practitioners, professionals, and specialists may be considered in future research.

References

- Ajima, O. M., & Ubana, E. U. (2018). The concept of health and wholeness in traditional African religion and social medicine. Arts Social Science Journal, 9(388), 1–5. doi:10.4172/2151-6200.1000388

- Asante, M. K. (1991). The Afrocentric idea in education. The Journal of Negro Education, 60(2), 170–180. doi:10.2307/2295608

- Asante, M. K. (2014). Facing South to Africa: Toward an Afrocentric critical orientation. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books.

- Bomoyi, Z. A. (2011). Incorporation of traditional healing into counseling services in tertiary institutions: Perspectives from a selected sample of students, psychologists, healers and student management leaders at the University of KwaZulu-Natal. University of Kwazulu-Natal, Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Social Science in the Graduate Programme in Counseling Psychology. Durban: UKZN.

- Boum, Y., Kwedi-Nolna, S., Haberer, J. E., & Leke, R. R. (2021). Traditional healers to improve access to quality health care in Africa. The Lancet. Global Health, 9(11), e1487–e1488. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(21)00438-1

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2013). Successful qualitative research: A practical guide for beginners. London: Sage.

- Chawane, M. (2016). The development of Afrocentricity: A historical survey. Yesterday and Today, 16(16), 78–99. doi:10.17159/2223-0386/2016/n16a5

- Commission for Employment Equity (2019). CEE-annual report. Pretoria: Department of Labour. Retrieved May 27, 2020, from https://www.labourguide.co.za/workshop/1692-19th-cee-annual-report/file

- Cumes, D. (2013). South African indigenous healing: How it works. Explore, 9(1), 58–65. doi:10.1016/j.explore.2012.11.007

- Dei, G. S. (1994). Afrocentricity a cornerstone of pedagogy. Anthropology and Education Quarterly, 25(1), 3–25.

- Denzin, N. K. (1989). Interpretive interactionism. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

- EAPA-SA (2015). Standards for employee assistance programmes in South Africa: EAPA South Africa branch. Retrieved July 20, 2022, from https://www.eapasa.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/EAPA-SA-Standards-4th-edition-2015.pdf

- EAPA-SA (2022). EAPA-SA Annual Eduweek 2022. EAPA-SA. Retrieved July 22, 2022, from https://www.eapasa.co.za/eduweek-2022/theme-description-topics-2022/

- eNCA (2019, January 17). Five celebs who have accepted their calling. eNCA. Retrieved May 28, 2020, from https://www.enca.com/life/five-celebs-who-have-accepted-their-calling

- Gelinas, L., Pierce, R. L., Winkler, S., Cohen, I. G., Lynch, H. F., & Bierer, B. E. (2017). Using social media as a research recruitment tool: Ethical issues and recommendations. The American Journal of Bioethics, 17(3), 3–14. doi:10.1080/15265161.2016.1276644

- Gessler, M. C., Msuya, D. E., Nkunya, M. H., Schär, A., Heinrich, M., & Tanner, M. (1995). Traditional healers in Tanzania: Sociocultural profile and three short portraits. Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 48(3), 145–160. doi:10.1016/0378-8741(95)01295-O

- Govender, T., & Vandayar, R. (2018). EAP in South Africa: HIV/AIDS pandemic drives development. Journal of Employee Assistance, 48(4), 12–21. Retrieved May 27, 2020, from http://hdl.handle.net/10713/8392

- Harris, M. L., Loxton, D., Wigginton, B., & Lucke, J. C. (2015). Recruiting online: Lessons from a longitudinal survey of contraception and pregnancy intentions of young Australian women. American Journal of Epidemiology, 181(10), 737–746. doi:10.1093/aje/kwv006

- Jang, M., & Vorderstrasse, A. (2019). Socioeconomic status and racial or ethnic differences in participation: Web-based survey. JMIR Research Protocols, 8(4), e11865. doi:10.2196/11865

- Kubeka, N. P. (2016). The psychological perspective on Zulu ancestoral calling: A phenomenology study. Amini dissertation submitted in part fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Arts in Clinical Psychology. Pretoria: University of Pretoria. Retrieved July 23, 2022, from https://repository.up.ac.za/bitstream/handle/2263/57191/Kubeka_Psychological_2016.pdf?sequence=1

- Lehdonvirta, V., Oksanen, A., Räsänen, P., & Blank, G. (2021). Social media, web, and panel surveys: Using non‐probability samples in social and policy research. Policy & Internet, 13(1), 134–155. doi:10.1002/poi3.238

- Lichtenstein, A. H., Berger, A., & Cheng, M. J. (2017). Definitions of healing and healing interventions across different cultures. Annals of Palliative Medicine, 6(3), 248–252. doi:10.21037/apm.2017.06.16

- Madlingozi, P. (2019). Eduweek 2019 speaker presentations. EAPA-SA. Retrieved July 20, 2022, from https://www.eapasa.co.za/eapa-sa-eduweek-2019-speakers/

- Maynard, J. (2017, January 12). EAP and EAPA flourishing in South Africa. The Journal of Employee Assistance, 47(1), 12–13. Retrieved May 27, 2020, from http://0-bi.gale.com.oasis.unisa.ac.za/global/article/GALE%7CA478974875/19890331e4c7

- Mbatha, N., Street, R. A., Ngcobo, M., & Gqaleni, N. (2012). Sick certificates issued by South African traditional health practitioners: Current legislation, challenges and the way forward: Issues in medicine. South African Medical Journal, 102(3 Pt 1), 129–31131. doi:10.7196/samj.5295

- McFarlane, C. (2015). South Africa: The rise of traditional medicine. Insight on Africa, 7(1), 60–70. doi:10.1177/0975087814554070

- McInroy, L. B. (2016). Pitfalls, potentials, and ethics of online survey research: LGBTQ and other marginalized and hard-to-access youths. Social Work Research, 40(2), 83–94. doi:10.1093/swr/svw005

- McRobert, C. J., Hill, J. C., Smale, T., Hay, E. M., & van der Windt, D. A. (2018). A multi-modal recruitment strategy using social media and internet-mediated methods to recruit a multidisciplinary, international sample of clinicians to an online research study. PLOS One, 13(7), e0200184. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0200184

- Mertens, D. M. (2009). Transformative research and evaluation. New York, NY: Division of Guilford.

- MetroFM (2018, January 30). Fresh breakfast team. MetroFM. Retrieved from http://beta.sabc.co.za/metrofm/blog/freshbreakfast-with-gogo-dineo-ndlanzi/

- Mkabela, Q. (2005). Using the Afrocentric method in researching indigenous African cultures. The Qualitative Report, 10(1), 178–189. Retrieved May 27, 2020, from https://nsuworks.nova.edu/tqr/vol10/iss1/10

- Mncube, Z. (2021). On local medical traditions. In D. Ludwig, I. Koskinen, Z. Mncube, L. Poliseli, & L. Reyes-Galindo (Eds.), Global epistemologies and philosophies of science (pp. 231–242). London: Routledge.

- Mokgobi, M. G. (2014). Understanding traditional healing. African Journal for Physical Health Education, Recreation and Dance, 20(Suppl2), 24–34. Retrieved May 27, 2020, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4651463/pdf/nihms653834.pdf

- Ndlovu, S. S. (2016). Traditional healing in KwaZulu-Natal province: A study of University students’ assessment, perceptions and attitudes. Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Social Sciences (Clinical Psychology) in the School of Applied Human Sciences. Pietermaritzburg: University of KwaZulu-Natal. Retrieved July 23, 2022, from https://ukzn-dspace.ukzn.ac.za/bitstream/handle/10413/14352/Ndlovu_Sithabile_Siphosenkosi_Progoria_2016.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- Omonzejele, P. F. (2008). African concepts of health, disease, and treatment: An ethical inquiry. Explore, 4(2), 120–6126. doi:10.1016/j.explore.2007.12.001

- Parliamentary Monitoring Group (2020). Question NW275 to the Minister of Health. Parliamentary Monitoring Group. Retrieved March 3, 2022, from https://pmg.org.za/committee-question/13610/

- Peltzer, K., & Khoza, L. B. (2002). Attitudes and knowledge of nurse practitioners towards traditional healing, faith healing and complementary medicine in the Northern Province of South Africa. Curationis, 25(2), 30–40. doi:10.4102/curationis.v25i2.749

- Petrus, T., & Isaacs-Martin, W. (2012). The multiple meanings of coloured identity in South Africa. Africa Insight, 42(1), 87–102. https://hdl.handle.net/10520/EJC125075

- Plaatjie, Q. A. (2021). Exploring students’ understandings of a decolonised psychology curriculum at a South African University. Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree MPsych at the University of the Western Cape. Retrieved July 22, 2022, from https://etd.uwc.ac.za/bitstream/handle/11394/8735/plaatjie_m_chs_2021.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- Ramulondi, M., De Wet, H., & Ntuli, N. R. (2022). The use of African traditional medicines amongst Zulu women during childbearing in northern KwaZulu-Natal. African Journal of Reproductive Health, 26(1), 66–75. doi:10.29063/ajrh2022/v26i1.7

- Republic of South Africa (1997). Basic Conditions of Employment Act, No. 75 of 1997. Pretoria: Government Printers.

- Reviere, R. (2001). Toward an Afrocentric research methodology. Journal of Black Studies, 31(6), 709–728. doi:10.1177/002193470103100601

- Roche, A., Kostadinov, V., Cameron, J., Pidd, K., McEntee, A., & Duraisingam, V. (2018). The development and characteristics of employee assistance programs around the globe. Journal of Workplace Behavioral Health, 33(3–4), 168–186. doi:10.1080/15555240.2018.1539642

- Ross, E. (2010). Inaugural lecture: African spirituality, ethics and traditional healing–implications for indigenous South African social work education and practice. South African Journal of Bioethics and Law, 3(1), 44–51.

- Sandlana, N., & Mtetwa, D. (2008). African religious faith healing practices and the provision of psychological well-being among AmaXhosa people. Indilinga: African Journal of Indigenous Knowledge Systems, 7(2), 119–132.

- Saunders, M. N., & Lewis, P. (2018). Doing research in business & management: An essential guide to planning your project (2nd ed.). Harlow, England: Pearson.

- Shewamene, Z., Dune, T., & Smith, C. A. (2017). The use of traditional medicine in maternity care among African women in Africa and the diaspora: A systematic review. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 17(1), 1–16. doi:10.1186/s12906-017-1886-x

- Shizha, E., & Charema, J. (2011). Health and wellness in Southern Africa: Incorporating indigenous and western healing practices. International Journal of Psychology and Counselling, 3(9), 167–175. doi:10.5897/IJPC10.030

- Soeker, S., Matimba, T., Machingura, L., Msimango, H., Moswaane, B., & Tom, S. (2015). The challenges that employees who abuse substances experience when returning to work after completion of employee assistance programme. Work, 53(3), 569–584. doi:10.3233/WOR-152230

- StatsSA (2018). General household survey. Pretoria: Statistics SA. Retrieved May 27, 2020, from http://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/P0318/P03182018.pdf

- UNAIDS (2006). Collaborating with traditional healers for HIV prevention and care in sub-Saharan Africa: Suggestions for program managers and field workers. Geneva: UNIAIDS. Retrieved May 28, 2020, from https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/documents/2006/20061020_jc967-tradhealers_en.pdf

- Willemse, R. P. (2018). An investigation into the South African correctional officers lived experience of their work and the employee assistance programme and meaning thereof. University of South Africa, Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of doctor of philosophy in the subject of psychology. Pretoria: UNISA. Retrieved May 29, 2020, from http://uir.unisa.ac.za/bitstream/handle/10500/25251/thesis_willemse_rp.pdf?sequence=4&isAllowed=y

- Zuma, T., Wight, D., Rochat, T., & Moshabela, M. (2016). The role of traditional health practitioners in Rural KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa: Generic or mode specific? BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 16(1), 304. doi:10.1186/s12906-016-1293-8