Abstract

Up to half of the population have introverted personalities. Workplace diversity can lead to increased productivity, creativity and problem-solving. Understanding introversion in relation to workplace performance and creativity and how to encourage inclusion of introverts would benefit employers and employees. We describe the evidence defining and evaluating introversion, prevalence of introversion across groups, and strategies for promoting workplace inclusion of introverts. We searched MEDLINE®, Embase, and PsycINFO up to February 11, 2021. Of 2,724 records, 21 studies were included. Introversion definitions were generally negative and dated. Robust prevalence data were unavailable, and no studies aimed to test strategies for promoting workplace inclusion of introversion. Nevertheless, literature suggests that employees who identify with modern definitions of introversion may benefit from individualized workplace strategies such as flexible working environments, work/home-life boundaries, varied team composition, provision of social support, and relaxation training. Further empirical studies in the industrial setting with robust designs using modernized personality definitions are warranted to support the development of effective strategies to increase inclusion of different personalities in the workplace.

Background

Personality theory is a compelling area of research within psychology that has been applied to individual differences (Furnham, Citation2001), health conditions (Strickhouser, Zell, & Krizan, Citation2017), and the workplace (Beus, Dhanani, & McCord, Citation2015; Lundgren, Kroon, & Poell, Citation2017; Van Hoye & Turban, Citation2015). The theory has developed extraversion and introversion as two key personality types, which psychologists have hypothesized to exist at opposite ends of the same continuum. Personality types and the extraversion/introversion dimensions were initially popularized by Jung in 1921 in his work on psychological types. Since then, early personality theorists have suggested that specific personality traits are stable and measurable (Allport, Citation1937; Cattell, Citation1965; H. J. Eysenck, Citation1952). Similarly, definitions of introversion and extraversion have also evolved over time, although the key characteristics have remained largely unchanged. Modern personality researchers often categorize extraversion (and its counterpart, introversion) as one of five key dimensions of personality, referred to as the Five Factor Model: Extraversion, Agreeableness, Conscientiousness, Neuroticism, and Openness to Experience (Goldberg, Citation1992). In this model, extraversion is represented as a continuum in which higher extraversion is associated with higher sociability, dominance, and positive emotions. Conversely, introversion is associated with lower scores on these characteristics (Costa & McCrae, Citation1988; Goldberg, Citation1990). Similarly, in Western cultures, stereotypes of these two personality types generally attach positive characteristics to extraverts compared with introverts (McCord & Joseph, Citation2020). Extraverts are most often characterized as warm, assertive, and sociable (Costa & McCrae, Citation1992; Watson & Clark, Citation1997), whereas introverts have been described as introspective, quiet, unsociable, and lacking in assertiveness (Bendersky & Shah, Citation2013; Watson & Clark, Citation1997).

The tendency toward a negative view of introversion was raised in Susan Cain’s book, Quiet: The power of introverts in a world that can’t stop talking (Cain, Citation2012). This popular work discusses the issue of bias within the workplace based on the notion that an extraverted personality remains ideal in contemporary Western cultures to the detriment of introverts. Cain reports that one third to half of Americans are believed to be introverts. However, the lack of inclusion in the workplace for introverts has resulted in missed opportunities in relation to innovation and productivity. Cain suggests that the challenges individuals may face in the workplace within the United States (US) due to being perceived by colleagues as introverted are numerous, and include being treated rudely, being seen as inferior, and being overlooked for promotions and leadership roles.

Previous literature reviews on personality in the workplace have primarily focused on extraversion and its effect on work performance (Sackett & Walmsley, Citation2014; Wilmot, Wanberg, Kammeyer-Mueller, & Ones, Citation2019). However, no existing reviews have provided insight on the importance of recognizing and promoting the inclusion of introverts in the workplace, or providing strategies to do so (Balsari-Palsule & Little Citation2020; Blevins, Stackhouse, & Dionne, Citation2021; Farrell, Citation2017). Gaining an understanding of the current landscape of evidence on introversion in the workplace may help to identify the obstacles that introverts face in the workplace, and what interventions may be successful to increase inclusion of introverts, based on robust scientific evidence. Many companies are keen to implement diversity and inclusion initiatives, but without understanding how introversion affects productivity and innovation, it is difficult to design effective workplace strategies. Thus, the objectives of this systematic review are to (1) describe and characterize the landscape of evidence defining and evaluating introversion, (2) determine the prevalence of introversion across various groups (e.g., age groups, races/ethnicities, gender identities, occupations), and (3) summarize the proposed potential strategies to recognize and promote the inclusion of introversion, all within the context of the global workplace.

Methods

Data sources and search strategies

Standard methodologies for conducting and reporting of systematic reviews as recommended by the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions were followed (Higgins, Citation2011). Results were reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, & Altman, Citation2009).

Searches were conducted in MEDLINE® and Embase via OvidSP, and PsycINFO via EBSCOhost, to capture records published from database inception to February 11, 2021. Search strategies consisted of keywords such as “introversion,” “extraversion,” “productivity,” “innovation,” “workplace” and “occupation,” which were searched for in the titles and abstracts of records. Full details of the search strategies are provided in Tables S1–S3 of the Supplementary Materials. Searches were limited to records published in English. Gray literature searches of conference proceedings indexed in Embase published from 2018 to 2021 were conducted as part of the main database search, as well as “hand-searches” of Google Scholar using our keywords, and the bibliographies of relevant literature reviews.

Table 1. A summary of the definitions and personality measures used to evaluate introversion among the included studies.

Table 3. Summary of proposed strategies to better accommodate introverts in the workplace.

Study selection

Study eligibility criteria were defined using a modified PICO framework (Population, Intervention, Comparator, Outcomes) as outlined in Table S4 of the Supplementary Materials (Higgins, Citation2011). These criteria guided the identification and selection of relevant studies for the review. Briefly, included were any studies on working adults that reported data addressing any of our research objectives. Studies enrolling populations of graduate- or undergraduate-level students were also included if their findings were considered applicable to the workplace setting (i.e., if the experiment or concept being tested was relevant to workplace tasks, such as group work dynamics).

Two independent senior reviewers were responsible for reviewing abstracts, conference proceedings, and gray literature sources according to the pre-defined selection criteria. All relevant records identified during title/abstract screening proceeded to a full-text screening phase for assessment of inclusion. Any discrepancies were resolved by a third reviewer. Studies that matched the PICO criteria following full-text screening were included for data extraction.

Data extraction and study quality assessment

Study characteristics such as study name, year, design, and country were extracted alongside participant characteristics such as age, gender, personality type, occupation, participant level of introversion, education level, job level, and size of the company or number of employees in the participants’ company. Data on personality measures used to evaluate introversion, interventions and outcomes of interest (e.g., those related to productivity, creativity and innovation in the workplace) were also extracted. Key conclusions and practical implications for managers and organizations were extracted and summarized qualitatively in tabular format by two senior reviewers. Strategies to better accommodate introverts in the workplace and factors affecting performance, creativity, burnout, engagement, and well-being/stress response of introverts in the workplace were categorized by the same senior reviewers to facilitate the summary of information.

Two independent investigators performed a critical appraisal of included studies using the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Checklist for Quasi-Experimental Studies (Joanna Briggs Institute, Citation2017), and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies (NIH National Heart, Lung, & Blood Institute n.d.). Any discrepancies were again resolved by a third reviewer.

Results

Study selection

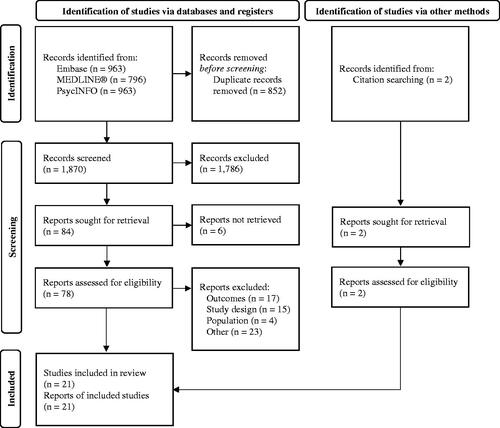

The literature search identified a total of 2,722 records and 2 additional records through searching the reference list of the included literature reviews. In total, 21 studies were included in the review ().

Study quality assessment

Non-randomized experimental studies (number of studies [n] = 8) were assessed with the JBI Checklist for Quasi-Experimental Studies (Figure S1 of the Supplemental Materials). Most studies were rated as generally high-quality for some domains (e.g., “cause” and “effect” description, similarity of outcome measurements). However, study quality was generally low or unclear based on domains including lack of control of participant groups being compared and lack of clarity in relation to the statistical analysis performed.

Cross-sectional studies (n = 11) and two cohort studies were assessed with the NIH Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies (Figure S2 of the Supplemental Materials). For this assessment, studies were high-quality across some domains (e.g., clearly stated research question) but were considered poor quality (i.e., high risk of bias) across most domains resulting in generally low ratings for the studies overall.

Study and participant characteristics

Most studies utilized a cross-sectional (n = 9) or quasi-experimental study design (n = 8). Total sample size ranged from 16 (Furnham & Bradley, Citation1997) to 897 participants (Rogers & Barber, Citation2019) (median: 157). The majority of studies were conducted in the US (n = 11); however, Europe (n = 7), China (n = 2), and Australia (n = 1) were also represented. Notably, over half of the studies (57%) were more than a decade old, and almost 40% (n = 8) were published before 1998.

Mean or median age across 14 reporting studies ranged from 19.8 years (Walker, Citation2007) to 44.9 years (Dijkstra, van Dierendonck, Evers, & De Dreu, Citation2005; Rogers & Barber, Citation2019) (median: 30.5). The percentage of women in the study groups varied widely from 11% (Dijkstra et al., Citation2005) to 100% (Parkes, Citation1986) (median: 56.2%) across 17 studies. Of note, studies enrolling 90% or more women were those conducted on nurses (Eastburg, Williamson, Gorsuch, & Ridley, Citation1994; Parkes, Citation1986; Regts & Molleman, Citation2016; Yao et al., Citation2018), a well-known female-dominated profession. Studies enrolling less than 20% women were conducted on employees of a company specializing in the development and construction of food processing systems, and employees of a coal manufacturing and transportation company (Dijkstra et al., Citation2005; Zhang, Zhou, & Kwan, Citation2017). Only four studies reported race/ethnicity, with three of them consisting of approximately 80% White participants (Baer, Jenkins, & Barber, Citation2016; Naylor, Kim, & Pettijohn, Citation2013; Rogers & Barber, Citation2019). Twelve studies enrolling populations of graduate- or undergraduate-level students were included. Of the nine studies involving working populations, occupations were mixed. Four studies recruited nursing staff, another four studies involved a mix of occupations (e.g., bankers, small business owners, delivery drivers, or university staff) and one study recruited those working in social care. A summary of study and participant characteristics is provided in Table S5 of the Supplementary Materials.

Participant level of introversion, education level, job level, and size of the company or number of employees in the participants’ company were poorly reported. These parameters were anticipated to be used in conjunction with population data on introverts to gain an understanding of the prevalence of introversion across groups; however, no such analyses could be made due to lack of reporting.

Definitions and evaluation of introversion

Personality was measured and defined with a variety of instruments across the included studies (). The most common measures used were those based on Eysenck’s theory of personality, which was linked theoretically to biological factors and focused on two dimensions: introversion/extraversion and neuroticism/stability. Across nine studies, introversion was measured with subscales taken from standardized instruments such as the Eysenck Personality Inventory or Eysenck Personality Questionnaire, which were developed and revised from 1964 to 1992 (with the exception of the 2000 Chinese translation). The main focus of these subscales was to evaluate extraversion; therefore, introverts were defined as those who scored low on the extraversion scales, which generally consisted of six to 12 items.

Instruments for measuring extraversion/introversion based on the Five Factor model were also commonly reported (n = 8). This model suggests that personality consists of five key traits: extraversion, openness, agreeableness, neuroticism and conscientiousness (Soldz & Vaillant, Citation1999). These measures of introversion commonly include 10 items. In alignment with Eysenck’s measures, these scales define introverts as those who score low on an extraversion scale. Much like Eysenck’s definition, extraversion was represented by warmth, positivity and assertiveness, while introversion was deemed as the opposite and grouped with adjectives like timid, withdrawn, unadventurous and reserved.

The last four studies used a variety of measures, two of which were standardized: the 16 Personality Factor H Questionnaire (16PF) (Eastburg et al., Citation1994) and the Ten Item Personality Inventory (TIPI) (Naylor et al., Citation2013). The 16PF was developed by Cattell, Eber, and Tatsuoka (Citation1970) and the “Factor H” scale was of one of 16 factors thought to make up personality. This scale was designed to measure social boldness and was reported as representing extraversion. If one scored low on this scale, they were thought to be shy, timid and threat-sensitive, and could therefore be classified as an introvert. Extraverts were those who scored high on the scale and were defined as being socially bold, venturesome, and thick-skinned.

The other standardized measure was the TIPI (Gosling, Rentfrow, & Swann, Citation2003). It is worth noting that this tool is exceptionally brief and consequently, the study that utilized this tool had only two items to measure introversion (i.e., the lack of extraversion). Participants were asked to describe how they rated themselves on a scale from one to seven in relation to two descriptions: “Extraverted, enthusiastic” and “Reserved, quiet”. If they scored higher on the former they were classified as extraverts, and if they scored higher on the latter they were classified as introverts. Those who had equivalent scores were excluded from the analysis.

The remaining studies utilized measures ranging in psychometric robustness. One study used a tool with some validation (Baer et al., Citation2016), the HEXACO-60 (Ashton & Lee, Citation2009). This instrument was originally based on the Five Factor model instruments but was adapted as the researchers who created the tool believed that personality has a sixth major dimension, “honesty-humility”.

Another study used a commercially developed measure, the PROSCAN (Houston & Solomon, Citation1977) for which no scientific validation information was available. However, this tool was used in combination with the Factor H scale (i.e., social boldness) of the 16PF. The PROSCAN tool measures extraversion by assessing whether one’s interaction style is outgoing versus bashful.

The last study (Kulik & Mahler, Citation1986) did not use a standardized instrument, but rather measured introversion by asking participants to rate themselves on the following three dimensions: outgoing-shy, extravert-introvert or talkative-quiet. Rating was done on a nine-point scale (with nine being very introverted) and those who rated themselves from seven to nine on at least two of the dimensions were classified as introverts.

Prevalence of introversion across groups

None of the studies explicitly aimed to measure the prevalence of introversion in a given population. However, the proportion of participants who were classified as introverts in the study were reported in four studies. The first study (Yao et al., Citation2018) reported that 53% of the participants were introverts, and the second study reported an inclusion rate of 43% introverts in their study (Naylor et al., Citation2013). However, it is likely that study investigators specifically aimed to recruit a balanced mix of introverts and extraverts.

The last two studies were less clear in how they came to include the number of introverts that they reported. The first of these studies (Jung, Lee, & Karsten, Citation2012) recruited a total of 88 upper-level business students from a large state university in the US, and reported that the final selection was ten introverts and ten extraverts. However, the authors were unclear if there were more or less of each classification to choose from or if this was essentially an opportunity sample. The second study (Kulik & Mahler, Citation1986) simply reported that their study group consisted of 23% introverts and 35% extraverts, but gave no indication of how many were originally assessed. Therefore, the true prevalence rate is unclear.

Finally, as one of the objectives of this review was to examine trends in population data on introverts across various groups (e.g., age groups, race/ethnicities, etc.), we aimed to capture data on participant characteristics of the introverts across reporting studies. However, none of the included studies reported participant characteristics specifically for the groups of introverts. In fact, there was a lack of detail overall in regard to participant characteristics, with three studies providing no participant data other than confirmation of student status (Barry & Stewart, Citation1997; Cox-Fuenzalida, Angie, Holloway, & Sohl, Citation2006; Topi, Valacich, & Rao, Citation2002).

Potential strategies for recognizing and promoting inclusion of introversion in the workplace

No studies were identified that aimed to test or describe an intervention or strategy designed to recognize and promote inclusion of introverts in the workplace. However, nine studies were identified that described factors shown to affect performance, creativity, burnout, engagement, and well-being/stress response in introverts (). These factors were considered to be key mediators in understanding what types of work environments are most suitable for introverts, and how workplaces can be tailored to better suit different personality types.

Table 2. Summary of factors affecting performance, creativity, burnout, engagement, and well-being/stress response of introverts in the workplace.

Factors that positively impacted the work performance of introverts included being connected to others in a network (specifically for introverts who are high on neuroticism) (Regts & Molleman, Citation2016), avoidance of sudden changes in workload level (although introverts had a smaller reduction in performance than extraverts in response to sudden changes in workload level) (Cox-Fuenzalida et al., Citation2006), and removal of distracting stimuli (Furnham & Bradley, Citation1997). Distracting stimuli and the use of computer-mediated communications were factors associated with decreased creativity in introverts (Jung et al., Citation2012).

Factors that led to reduced burnout and increased work engagement included social support (although introverts required less social support than extraverts to avoid burnout) (Eastburg et al., Citation1994), adequate separation between home and work life (Baer et al., Citation2016), and reduced stress (Yao et al., Citation2018). Factors associated with poor well-being and increased stress for introverts were workplace conflicts (Dijkstra et al., Citation2005) and intrusions in the workplace (unexpected interpersonal contact that disrupts workflow) (Rogers & Barber, Citation2019). Interestingly, it was observed that introverts were less stressed in response to workplace intrusions compared to extraverts. Rogers and Barber (Citation2019) considered this observation to be counterintuitive, as it did not support their initial hypothesis. A potential explanation for this finding was described, stating that extraverted employees may have been experiencing more intrusions overall than introverts, but were reporting on them less because they did not interpret such interactions as “disruptive,” but rather as welcomed interpersonal contact or social support.

Six studies included in our review proposed potential strategies to better accommodate different personality types in the workplace by addressing issues pertaining to reduced performance, decreased creativity, burnout, and reduced engagement ().

The first of two studies proposing potential strategies to increase workplace performance described that introverts compared to both extraverts and control participants (those scoring mid-range on the extraversion scale used) reported having a more negative group-work experience, although it was noted that personality did not significantly affect the performance scores after completing the group work task (Walker, Citation2007). To mitigate this, authors suggested that group work may be structured to contain a combination of collaborative and individual work components. For example, some tasks may be divided into sub-components, where each group member is made responsible for an individual sub-component, and then the group can work collectively at the start and end of the task to divide work and assemble the final components. In line with this, the second study described that personality type plays an important role in group processes, and proposed that creating a diverse team, without overemphasizing extraversion as a favorable characteristic, may help to overcome potential performance losses (Barry & Stewart, Citation1997).

Proposed strategies to increase creativity in the workplace included the use of high-complexity tasks to challenge introverted colleagues, therefore enhancing their creativity (Zhang et al., Citation2017). As well, the use of relaxation training (e.g., stretching, breathing, freeing the mind of negative thoughts) was suggested, which was a creativity-enhancing technique found to be more beneficial to introverts than extraverts (O'Connor, Gardiner, & Watson, Citation2016).

Of two studies reporting strategies to reduce burnout and/or increase work engagement, one study focused on a group of nurses noted that those with introverted personalities feel stronger burnout when faced with stress compared to other personality types (Yao et al., Citation2018). To combat this, authors described that for introverts, strategies to enhance individuals’ self-efficacy, including psychological help and social support, may be implemented to help with burnout as needed. The second study investigated work-life balance in a group of crowdsourcing marketplace employees (Baer et al., Citation2016). Findings suggested that employers should encourage boundaries and reduce workplace norms that encourage them to be constantly accessible, rather than taking sufficient time to recharge in between work times.

Discussion

The aims of this review were to describe the evidence defining and evaluating introversion, determine the prevalence of introversion across various groups, and summarize the proposed potential strategies for recognizing and promoting inclusion of introversion in the global workplace.

As part of our first objective on the evaluation and definition of introversion, we identified trends in personality measures and author definitions of introversion that consistently leaned toward negative attributes. Examples of this can be found in published personality measures (i.e., HEXACO-60, 2009) (Ashton & Lee, Citation2009) where the statement, “I sometimes feel that I am a worthless person,” is included as one of ten questions to measure extraversion. When an individual strongly agrees with this statement, this translates to them being classified as an introvert. Additionally, it was observed that the most commonly used measures of introversion/extraversion were those based on Eysenck’s personality theory, which were developed and revised between 1964 and 1992. As well, the main focus of these tools was to evaluate extraversion, where introverts were defined as those who scored low on extraversion scales. The consistent use of such dated tools to measure personality in publications as recent as 2018 (Yao et al., Citation2018) demonstrates that there is a paucity of modern standardized and validated tools available to assess and define introverts.

The definition of introversion and extraversion that is encouraged in popular literature (Cain, Citation2012) approaches personality types quite differently than existing personality measures. In her book, Cain suggests that introverts are broadly represented by people that tend toward being energized from having some time to themselves while extraverts are those who tend to be energized after spending time with others. This is more in line with other areas of psychological research which suggests shyness, ability to lead, and high levels of productivity are not specific to the classic categories of personality type (Bortoluzzi, Carey, McArthur, & Menassa, Citation2018; Buchanan & Kern, Citation2017; Buss, Citation1986; Kawiana, Dewi, Martini, & Suardana, Citation2018).

In terms of our second objective, our review identified no relevant studies that provided robust or direct evidence on the prevalence of introverts across various groups (e.g., age groups, races/ethnicities, gender identities, occupations). This may reflect an overall scarcity of literature available on introverts. In addition, none of the included studies reported participant characteristics for introverts, and there was a lack of detail on several participant characteristics that we sought to identify: namely, level of introversion, education level, job level, and size of the company or number of employees in the participants’ company. Further research on introversion at the population level is needed to better understand introverts and their unique needs at the workplace and effective approaches to implement personality diversity.

With respect to our third objective on proposed potential strategies to recognize and promote the inclusion of introversion in the workplace, evidence was again scarce. No studies were identified that directly aimed to test or describe such strategies, which highlights an important knowledge gap. Nevertheless, we identified several factors shown to affect performance, creativity, burnout, engagement, and well-being/stress response in introverts. All factors were unique to a single study. The feeling of being connected to others in a network was a positive factor for introverts, as was the reduction of sudden changes to workload, social support, work-life balance, and elimination of workplace intrusions or distracting stimuli. The latter of these factors is consistent with existing research, which show that introverts tend to have higher sensitivity to noise during mental performance compared to extraverts (Belojevic, Jakovljevic, & Slepcevic, Citation2003). This finding suggests that allowing for quiet spaces and periods of time with limited interruptions may be beneficial for introverts to perform more effectively at work.

One of the key findings from our review was the identification of potential strategies to better accommodate different personality types in the workplace by addressing issues related to reduced work performance, decreased creativity, burnout, reduced engagement, and well-being/stress response. This was considered an important topic of our research because having a diverse workplace introduces many benefits that can be realized by employers and employees as well as policymakers, and practitioners. Benefits of diversity in the workplace include improved communication with an organization’s clients, a sense of harmony, and increased productivity, creativity and problem-solving (Foma, Citation2014). Previous research has shown that teams following diversity and equality management practices demonstrate higher productivity and innovation, as well as lower employee turnover (Armstrong et al., Citation2010). Turnover is expensive and hinders productivity. In fact, many company stakeholders now demand that the organizations in which they invest abide by practices encouraging low employee turnover, rewarding team performance and empowering employees to express themselves safely and openly (Foma, Citation2014).

Strategies to improve work performance included adaptions to group work tasks to accommodate different personality types, and increasing diversity of teams with respect to personality type. Authors of one study forewarned the risks of overemphasizing extraversion as a favorable trait of team members, which may decrease overall performance (Barry & Stewart, Citation1997). We observed that some strategies may benefit certain personality types more than others. For example, relaxation training (e.g., stretching, breathing, freeing the mind of negative thoughts) was perceived to be a creativity-enhancing technique for introverts, while idea generation exercises were more effective for extraverts (O'Connor et al., Citation2016). This finding implies that there is no universal solution to inclusion of different personalities in the workplace; rather, techniques must be adapted to the unique needs of individual employees.

Removing workplace norms that encourage employees to be continuously accessible for work was also suggested as a potential strategy to accommodate different personality types in the workplace, as was encouraging employees to take sufficient time to recharge in between work time. These two strategies tie into a larger theme of a work-life balance. Allowing for flexible location or working hours are two examples of methods that can be used to encourage work-life balance for employees (Delecta, Citation2011). For example, employees may have the choice to work from home for a portion of the week, or those with flexible working hours may be required to work a number of hours each week, but have the ability to allocate their hours worked each day based on their preferences. Whether implementing these methods are effective from both an employee (job satisfaction, work-life balance) and an employer (return on labor, staff turnover, absenteeism, cost) perspective is debated in the current literature, as clear empirical evidence on their effectiveness is lacking.

In light of these various strategies, one key theme was described by all studies unanimously. Individual differences influence how people excel in the workplace, and managers and organizations should recognize and account for these differences when assigning tasks, creating teams, and establishing work environments aimed to increase productivity and innovation. Furthermore, there is evidence that suggests those who have less emotional stability (e.g., ability to cope with stress) or those with low self-efficacy could benefit from social support in the workplace (Yao et al., Citation2018). Offering social support to all employees may allow those who self-identify with modern characteristics of introversion (i.e., drawing energy from “quiet” practices) to be more aware and confident in using such services. Allowing for self-identification of optimal work preferences and processes may be the first step in identifying new strategies to increase inclusivity. Employees who have space to identify their strengths and to determine how their productivity and innovation can be naturally leveraged, might then be able to communicate their needs. It should not be assumed that they will be unable to offer this feedback. Shyness, which has been stereotypically considered a key “introvert” characteristic, is actually a different construct altogether and research has been conducted to attempt to tease out these differences (Jones, Schulkin, & Schmidt, Citation2014).

Additionally, it is important to consider that personality types are not currently considered as a key component of diversity in the US and other countries. Race, ethnicity, age, gender, sexual orientation, disabilities and socioeconomic status, as well as religious and political beliefs have generally been at the forefront of diversity and inclusion initiatives. However, employers and organizations should also pursue initiatives and strategies to include personality as part of diversity and inclusion activities. A recent umbrella review aimed at assessing the association between diversity, innovation, patient health outcomes, and financial performance, found that the majority of the 16 included reviews reported positive associations between diversity, work quality outcomes (e.g., clinical protocol adherence), and financial performance (Gomez & Bernet, Citation2019). Diversity dimensions of included reviews were race, ethnicity, gender, age, workplace role, and immigrant status, but did not include personality. This again points to a need for more empirical research on the role of personality type in improving workplace productivity and innovation.

Finally, an important point to consider regarding the timing of our review is that the impacts of introversion on productivity and innovation in the workplace has yet to be thoroughly investigated in light of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. In early 2020, organizations around the globe began a rapid transition to enforcing strict social distancing protocols and remote work given the pandemic. During this time, a common belief of the public has been that, anecdotally, remote working may have been more well received by introverts compared to extraverts. Although empirical data on this topic is somewhat lacking, there has been some evidence to suggest that extraverts, in response to working from home due to COVID-19, experienced reduced productivity, engagement and job satisfaction, and increased burnout (Evans, Meyers, De Calseyde, & Stavrova, Citation2021). Introverts have also been shown to have fewer depressive symptoms in response to more stringent COVID-19 pandemic-related restrictions (e.g., workplace office closings, travel restrictions, stay at home requirements) (Wijngaards, de Zilwa, & Burger, Citation2020). In this way, as working remotely has become a new social norm, individuals who are not dependent on large social gatherings and who thrive in “quiet” places may now be in demand. However, it is also important to consider the intricacies of working from home, and individual differences in preference. Issues such as the inability to separate work from home life may have detrimental effects in terms of burnout, engagement, and job satisfaction (Baer et al., Citation2016). Organizational strategies such as allowing for flexible working environments may help to foster a more inclusive company culture.

Our review has several strengths. Firstly, to our understanding, this is the first systematic literature review that aimed to describe strategies to recognize and promote the inclusion of introversion within the global workplace. Second, the searches used to identify our studies were comprehensive, and included three major electronic databases as well as gray literature sources. This resulted in an evidence base that is representative of the existing literature on this topic.

Limitations of our review included restriction of our inclusion criteria to articles published in English, which may have increased selection bias. Additionally, the personality measures which were used to define study populations tended to be heterogenous across studies, antiquated in nature, overly simplistic, and were generally negative in the perception of introverts. Outcomes for measuring productivity and innovation in the workplace varied substantially across the included studies. As such, it was not possible to analyze definitive or quantitative trends in factors that may affect the performance of introverts in the workplace. Moreover, it should be noted that introversion/extraversion is just one of many other personality characteristics, and our review did not consider other personality factors or characteristics of workers and how they may affect workplace performance. Further research into the interactions between introversion and other personality characteristics and the impact on workplace productivity and creativity is warranted. Lastly, studies identified were generally of lower quality, had small sample sizes (14 studies had <200 participants), and over half were published more than ten years ago. These limitations should be taken into consideration when interpreting the findings of this review, as larger, more robust study designs are needed to draw definitive conclusions. Additionally, considering the substantial changes in modern personality theory combined with drastically changed social norms (i.e., acceptable workplace behavior, occupational gender, and race bias awareness) (Bielby, Citation2000), it is crucial to consider the date of publication when interpreting the findings of the included studies.

Conclusion

This review has identified significant gaps in the evidence relating introversion with productivity and innovation in the workplace. Recent studies on this topic with large sample sizes and robust methodologies are limited. The lack of standardized outcomes to measure innovation and productivity in the workplace pose a challenge for researchers and organizational leaders who seek to make evidence-based decisions on how to increase inclusion of different personalities in the workplace. Definitions of introversion have been relatively limited by negative theoretical assumptions, and the scarcity of introvert-specific literature reflects this. Nevertheless, available literature suggests that employees who positively identify with modern definitions of introversion (i.e., someone who benefits from solitude to recharge) would benefit from the adaption of workplace strategies to account for individual differences, such as flexible working environments, provision of social support where needed, and employer initiatives to increase personality diversity of teams. Future studies should be conducted in real-world workplace settings, as academic settings of student populations are not always diverse and students may not have the appropriate career or work experience for the study findings to be applicable to the corporate world. Further empirical research with robust designs utilizing modernized definitions of personality is warranted. This research can guide the development of effective strategies to increase inclusion of different personalities in the workplace.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (119.6 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Ana Howarth and Antonia Andonova of Evidinno Outcomes Research Inc. (Vancouver, BC, Canada) for their contributions in conducting the literature review. Medical writing support and editorial assistance were provided by Ana Howarth.

Disclosure statement

Juliet Herbert, Leticia Ferri, Iryna Shnitsar, and Kald Abdallah are employees and shareholders of Bristol Myers Squibb. Brenda Hernandez and Isaias Zamarripa were employees of Bristol Myers Squibb at the time the study was conducted. Mir Sohail Fazeli and Kimberly Hofer report employment with Evidinno Outcomes Research Inc., which was contracted by Bristol Myers Squibb to conduct this study.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Allport, G. W. (1937). Personality: A psychological interpretation. New York, NY: Holt.

- Armstrong, C., Flood, P. C., Guthrie, J. P., Liu, W., MacCurtain, S., & Mkamwa, T. (2010). The impact of diversity and equality management on firm performance: Beyond high performance work systems. Human Resource Management, 49(6), 977–998. doi:10.1002/hrm.20391

- Ashton, M. C., & Lee, K. (2009). The HEXACO–60: A short measure of the major dimensions of personality. Journal of Personality Assessment, 91(4), 340–345. doi:10.1080/00223890902935878

- Baer, S. M., Jenkins, J. S., & Barber, L. K. (2016). Home is private…Do not enter! Introversion and sensitivity to work-home conflict. Stress and Health, 32(4), 441–445. doi:10.1002/smi.2628

- Balsari-Palsule, S., & Little, B. R. (2020). Quiet strengths: Adaptable introversion in the workplace. In L. A. Schmidt & K. L. Poole (Eds.), Adaptive shyness (pp. 181–197). Cham: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-38877-5_10

- Barry, B., & Stewart, G. L. (1997). Composition, process, and performance in self-managed groups: The role of personality. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 82(1), 62–78. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.82.1.62

- Belojevic, G., Jakovljevic, B., & Slepcevic, V. (2003). Noise and mental performance: Personality attributes and noise sensitivity. Noise Health, 6(21), 77–89.

- Bendersky, C., & Shah, N. P. (2013). The downfall of extraverts and rise of neurotics: The dynamic process of status allocation in task groups. Academy of Management Journal, 56(2), 387–406. doi:10.5465/amj.2011.0316

- Beus, J. M., Dhanani, L. Y., & McCord, M. A. (2015). A meta-analysis of personality and workplace safety: Addressing unanswered questions. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 100(2), 481–498. doi:10.1037/a0037916

- Bielby, W. T. (2000). Minimizing workplace gender and racial bias. Contemporary Sociology, 29(1), 120–129. doi:10.2307/2654937

- Blevins, D. P., Stackhouse, M. R. D., & Dionne, S. D. (2021). Righting the balance: Understanding introverts (and extraverts) in the workplace. International Journal of Management Reviews, 24(1), 78–98. doi:10.1111/ijmr.12268

- Bortoluzzi, B., Carey, D., McArthur, J., & Menassa, C. (2018). Measurements of workplace productivity in the office context: A systematic review and current industry insights. Journal of Corporate Real Estate, 20(4), 281–301. doi:10.1108/JCRE-10-2017-0033

- Buchanan, A., & Kern, M. L. (2017). The benefit mindset: The psychology of contribution and everyday leadership. International Journal of Wellbeing, 7(1), 1–11. doi:10.5502/ijw.v7i1.538

- Buss, A. H. (1986). A Theory of Shyness. In W. H. Jones, J. M. Cheek, & S. R. Briggs (Eds.), Shyness: Perspectives on research and treatment (pp. 39–46). New York: Springer US. doi:10.1007/978-1-4899-0525-3_4

- Cain, S. (2012). Quiet: The power of introverts in a world that can’t stop talking. New York: Broadway Books.

- Cattell, R. B., Eber, H., & Tatsuoka, M. M. (1970). Handbook for the sixteen personality factor questionnaire (16 PF). Champaign, IL: Institute for Personality and Ability Testing.

- Cattell, R. B. (1965). The scientific analysis of personality. Hammondsworth: Penguin Books.

- Chay, Y. W. (1993). Social support, individual differences and well-being: A study of small business entrepreneurs and employees. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 66(4), 285–302. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8325.1993.tb00540.x

- Costa, P. T., & McCrae, R. R. (1988). Personality in adulthood: A six-year longitudinal study of self-reports and spouse ratings on the Neo personality inventory. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(5), 853–863. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.54.5.853

- Costa, P. T., & McCrae, R. R. (1992). Normal personality assessment in clinical practice: The NEO Personality Inventory. Psychological Assessment, 4(1), 5–13. doi:10.1037/1040-3590.4.1.5

- Cox-Fuenzalida, L. E., Angie, A., Holloway, S., & Sohl, L. (2006). Extraversion and task performance: A fresh look through the workload history lens. Journal of Research in Personality, 40(4), 432–439. doi:10.1016/j.jrp.2005.02.003

- Delecta, P. (2011). Work life balance. International Journal of Current Research, 3(4), 186–189.

- Dijkstra, M. T. M., van Dierendonck, D., Evers, A., & De Dreu, C. K. W. (2005). Conflict and well-being at work: The moderating role of personality. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 20(2), 87–104. doi:10.1108/02683940510579740

- Donnellan, M. B., Oswald, F. L., Baird, B. M., & Lucas, R. E. (2006). The Mini-IPIP Scales: Tiny-yet-effective measures of the Big Five Factors of Personality. Psychological Assessment, 18(2), 192–203. doi:10.1037/1040-3590.18.2.192

- Eastburg, M. C., Williamson, M., Gorsuch, R., & Ridley, C. (1994). Social support, personality, and burnout in nurses. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 24(14), 1233–1250. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.1994.tb00556.x

- Erez, A., Schilpzand, P., Leavitt, K., Woolum, A. H., & Judge, T. A. (2015). Inherently relational: Interactions between peers’ and individuals’ personalities impact reward giving and appraisal of individual performance. Academy of Management Journal, 58(6), 1761–1784. doi:10.5465/amj.2011.0214

- Evans, A. M., Meyers, M. C., De Calseyde, P. P. V., & Stavrova, O. (2021). Extroversion and conscientiousness predict deteriorating job outcomes during the COVID-19 transition to enforced remote work. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 13(3), 781–791. doi:10.1177/19485506211039092

- Eysenck, H. J. (1952). The scientific study of personality. London: MacMillan.

- Eysenck, H. J., & Eysenck, S. B. G. (1975). Manual of the Eysenck Personality Questionnaire (junior & adult). London: Hodder and Stoughton Educational.

- Eysenck, S. B., & Eysenck, H. J. (1964). An improved short questionnaire for the measurement of extraversion and neuroticism. Life Sciences, 3(10), 1103–1109. doi:10.1016/0024-3205(64)90125-0

- Eysenck, S. B., Eysenck, H. J., & Barrett, P. (1985). A revised version of the Psychoticism scale. Personality and Individual Differences, 6(1), 21–29. doi:10.1016/0191-8869(85)90026-1

- Farrell, M. (2017). Leadership reflections: Extrovert and introvert leaders. Journal of Library Administration, 57(4), 436–443. doi:10.1080/01930826.2017.1300455

- Foma, E. (2014). Impact of workplace diversity. Review of Integrative Business & Economics Research, 3(1), 402–410.

- Francis, L. J., Brown, L. B., & Philipchalk, R. (1992). The development of an abbreviated form of the revised Eysenck personality questionnaire (EPQR-A): Its use among students in England, Canada, the U.S.A. and Australia. Personality and Individual Differences, 13(4), 443–449. doi:10.1016/0191-8869(92)90073-X

- Furnham, A. (2001). Personality and individual differences in the workplace: Person–organization–outcome fit. In B. Roberts & R. Hogan (Eds.), Personality psychology in the workplace (pp. 223–251). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. doi:10.1037/10434-009

- Furnham, A., & Bradley, A. (1997). Music while you work: The differential distraction of background music on the cognitive test performance of introverts and extroverts. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 11(5), 445–455. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1099-0720(199710)11:5<445::AID-ACP472>3.0.CO;2-R

- Goldberg, L. R. (1990). An alternative “description of personality”: The big-five factor structure. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 59(6), 1216–1229. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.59.6.1216

- Goldberg, L. R. (1992). The development of markers for the Big-Five factor structure. Psychological Assessment, 4(1), 26–42. doi:10.1037/1040-3590.4.1.26

- Goldberg, L. R. (1999). A broad-bandwidth, public domain, personality inventory measuring the lower-level facets of several five-factor models. Personality Psychology in Europe, 7(1), 7–28.

- Goldberg, L. R., Johnson, J. A., Eber, H. W., Hogan, R., Ashton, M. C., Cloninger, C. R., & Gough, H. G. (2006). The international personality item pool and the future of public-domain personality measures. Journal of Research in Personality, 40(1), 84–96. doi:10.1016/j.jrp.2005.08.007

- Gomez, L. E., & Bernet, P. (2019). Diversity improves performance and outcomes. Journal of the National Medical Association, 111(4), 383–392. doi:10.1016/j.jnma.2019.01.006

- Gosling, S. D., Rentfrow, P. J., & Swann, W. B. (2003). A very brief measure of the Big-Five personality domains. Journal of Research in Personality, 37(6), 504–528. doi:10.1016/S0092-6566(03)00046-1

- Heaton, A. W., & Kruglanski, A. W. (1991). Person perception by introverts and extraverts under time pressure: Effects of need for closure. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 17(2), 161–165. doi:10.1177/014616729101700207

- Hendriks, J., Hofstee, W., & Raad, B. (1999). The Five-Factor Personality Inventory. Personality and Individual Differences, 27, 307–325. doi:10.1016/S0191-8869(98)00245-1

- Higgins, J. P. (2011). Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration. www.handbook.cochrane.org.

- Houston, S. R., & Solomon, D. (1977). Human resources index occupational survey (Research Monograph Nos. 1 & 2). Professional Dynametric Program.

- Joanna Briggs Institute. (2017). The Joanna Briggs Institute critical appraisal tools for use in JBI systematic reviews: Checklist for quasi-experimental studies (non-randomized experimental studies). Retrieved April 7, 2021, from https://jbi.global/sites/default/files/2019-05/JBI_Quasi-Experimental_Appraisal_Tool2017_0.pdf.

- Jones, K. M., Schulkin, J., & Schmidt, L. A. (2014). Shyness: Subtypes, psychosocial correlates, and treatment interventions. Psychology, 5(3), 244–254. doi:10.4236/psych.2014.53035

- Jung, J. H., Lee, Y., & Karsten, R. (2012). The moderating effect of extraversion–introversion differences on group idea generation performance. Small Group Research, 43(1), 30–49. doi:10.1177/1046496411422130

- Kawiana, I. G. P., Dewi, L. K. C., Martini, L. K. B., & Suardana, I. B. R. (2018). The influence of organizational culture, employee satisfaction, personality, and organizational commitment towards employee performance. International Research Journal of Management, IT and Social Sciences, 5(3), 35–45.

- Kirkcaldy, B., Thome, E., & Thomas, W. (1989). Job satisfaction amongst psychosocial workers. Personality and Individual Differences, 10(2), 191–196. doi:10.1016/0191-8869(89)90203-1

- Kulik, J. A., & Mahler, H. I. (1986). Self-confirmatory effects of delay on perceived contribution to a joint activity. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 12(3), 344–352. doi:10.1177/0146167286123009

- Lundgren, H., Kroon, B., & Poell, R. F. (2017). Personality testing and workplace training. European Journal of Training and Development, 41(3), 198–221. doi:10.1108/EJTD-03-2016-0015

- Markus, H. (1977). Self-schemata and processing information about the self. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 35(2), 63–78. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.35.2.63

- McCord, M., & Joseph, D. (2020). A framework of negative responses to introversion at work. Personality and Individual Differences, 161, 109944. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2020.109944

- Mingyi, Q., Guocheng, W., Rongchun, Z., & Shen, Z. (2000). Development of the revised Eysenck Personality Questionnaire short scale for Chinese (EPQ-RSC). Acta Psychologica Sinica, 32(3), 317.

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., & Altman, D. G. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine, 6(7), e1000097. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

- Naylor, P. D., Kim, J., & Pettijohn, T. F. III. (2013). The role of mood and personality type on creativity. Psi Chi Journal of Psychological Research, 18(4), 148–156.

- NIH National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. n.d. Study quality assessment tools – Quality assessment tool for observational cohort and cross-sectional studies. Retrieved July 6 from https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools.

- O'Connor, P. J., Gardiner, E., & Watson, C. (2016). Learning to relax versus learning to ideate: Relaxation-focused creativity training benefits introverts more than extraverts. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 21, 97–108. doi:10.1016/j.tsc.2016.05.008

- Parkes, K. R. (1986). Coping in stressful episodes: The role of individual differences, environmental factors, and situational characteristics. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1277–1292. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1277

- Regts, G., & Molleman, E. (2016). The moderating influence of personality on individual outcomes of social networks. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 89(3), 656–682. doi:10.1111/joop.12147

- Rogers, A. P., & Barber, L. K. (2019). Workplace intrusions and employee strain: The interactive effects of extraversion and emotional stability. Anxiety, Stress, and Coping, 32(3), 312–328. doi:10.1080/10615806.2019.1596671

- Sackett, P. R., & Walmsley, P. T. (2014). Which personality attributes are most important in the workplace? Perspectives on Psychological Science, 9(5), 538–551. doi:10.1177/1745691614543972

- Saucier, G. (1994). Mini-markers: A brief version of Goldberg’s unipolar big-five markers. Journal of Personality Assessment, 63(3), 506–516. doi:10.1207/s15327752jpa6303_8

- Soldz, S., & Vaillant, G. E. (1999). The Big Five personality traits and the life course: A 45-year longitudinal study. Journal of Research in Personality, 33(2), 208–232. doi:10.1006/jrpe.1999.2243

- Strickhouser, J. E., Zell, E., & Krizan, Z. (2017). Does personality predict health and well-being? A metasynthesis. Health Psychology, 36(8), 797–810. doi:10.1037/hea0000475

- Topi, H., Valacich, J. S., & Rao, M. T. (2002). The effects of personality and media differences on the performance of dyads addressing a cognitive conflict task. Small Group Research, 33(6), 667–701. doi:10.1177/1046496402238620

- Van Hoye, G., & Turban, D. (2015). Applicant–employee fit in personality: Testing predictions from similarity-attraction theory and trait activation theory. International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 23, 210–223. doi:10.1111/ijsa.12109

- Walker, A. (2007). Group work in higher education: Are introverted students disadvantaged? Psychology Learning & Teaching, 6(1), 20–25. doi:10.2304/plat.2007.6.1.20

- Watson, D., & Clark, L. A. (1997). Extraversion and its positive emotional core. In R. Hogan, J. Johnson, & S. R. Briggs (Eds.), Handbook of personality psychology (pp. 767–793). San Diego: Academic Press. doi:10.1016/B978-012134645-4/50030-5

- Wijngaards, I., de Zilwa, S. C. S., & Burger, M. J. (2020). Extraversion moderates the relationship between the stringency of COVID-19 protective measures and depressive symptoms. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 568907. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.568907

- Wilmot, M. P., Wanberg, C. R., Kammeyer-Mueller, J. D., & Ones, D. S. (2019). Extraversion advantages at work: A quantitative review and synthesis of the meta-analytic evidence. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 104(12), 1447–1470. doi:10.1037/apl0000415

- Yao, Y., Zhao, S., Gao, X., An, Z., Wang, S., Li, H., … Dong, Z. (2018). General self-efficacy modifies the effect of stress on burnout in nurses with different personality types. BMC Health Services Research, 18(1), 667. doi:10.1186/s12913-018-3478-y

- Zhang, X., Zhou, J., & Kwan, H. K. (2017). Configuring challenge and hindrance contexts for introversion and creativity: Joint effects of task complexity and guanxi management. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 143, 54–68. doi:10.1016/j.obhdp.2017.02.003