Abstract

In recent years, nurses experienced higher workloads which has an adverse impact on their quality of life (QoL), particularly in nurses from neurological wards as they are exposed to additional stressors due to physical and psychological strains. This study analyzed the relationship between psychological morbidity, burnout, social support, career duration, and QoL in nurses from neurological wards, including the indirect effect of burnout. A total of 92 nurses were assessed on social support, psychological distress, burnout, and QoL. Pearson’s correlations and a path analysis were conducted to analyze the relationship among variables. The results showed that burnout had an indirect effect in the relationship between psychological morbidity/satisfaction with social support and mental QoL. Physical QoL showed an indirect effect in the relationship between career duration/psychological morbidity and mental QoL. Satisfaction with social support had a direct effect on mental QoL, although career duration directly impacted physical QoL. Interventions on burnout and physical QoL are crucial to promote nurses’ mental QoL, particularly nurses with longer careers. Programs of occupational health should address stress management to promote nurses’ engagement, since hospitals and nursing homes are excellent settings to offer these types of programs on a regular basis.

Introduction

Nurses represent more than half of health care professionals worldwide and have a critical role in health promotion (World Health Organization, Citation2020). Although the number of nurses has grown steadily over the past decades, during the last few years, nurses have experienced higher workloads, mainly due to increased demand for nurses and poor staffing ratios (Lee & Yusof, Citation2018), with an adverse impact on their quality of life (QoL) (Ebrahimi et al., Citation2021). In addition, nurses deal with multiple stressors such as poor work environments, fatigue, insufficient resources, the risk of infection, and low wages. Given that the QoL of nurses has an impact on health care quality and safety, it is of great importance for society to assess nurses’ QoL (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, Citation2021), particularly in nurses from neurological wards since they are more exposed to heavy workloads than other nurses working in other settings (Elovainio et al., Citation2015; Ślusarz et al., Citation2022).

Nursing professionals are more prone to physical, psychological, and social stressors (Serinkan & Kaymakçi, Citation2013), which is reflected in higher levels of burnout reported by these professionals (Woo et al., Citation2020). Burnout is a response to long-term job stressors characterized by emotional exhaustion, loss of motivation and commitment, with an impact in the quality of services provided (Johnson et al., Citation2018). The most widely recognized definition of burnout was proposed by Maslach and Jackson (Citation1981), who defined burnout as a syndrome that comprised emotional exhaustion (i.e., fatigue or energy depletion), depersonalization (i.e., lack of empathy with patients), and reduced personal accomplishment (i.e., unsatisfaction about own job accomplishments). According to a Portuguese study conducted with 1262 nurses and 466 physicians (Marôco et al., Citation2016), nurses and physicians reported moderate (21.6%) to high (47.8%) levels of burnout with no significant differences between the two health professions. In fact, nursing is considered one of the health professions with higher risk of job stressors and burnout (Bilal & Ahmed, Citation2017).

Burnout is responsible for low productivity, turnover, high absenteeism, and lower QoL in nurses (De Looff et al., Citation2019). The adverse effect of burnout on nurses’ QoL has been evidenced in several studies (Khatatbeh et al., Citation2022; López-López et al., Citation2019). Nurses working with patients with neurological conditions such as dementia are exposed to particular work stressors resulting from unpredictable and complex crisis situations, often involving conflict and aggressions (Miyamoto et al., Citation2010; Tonso et al., Citation2016) and, therefore, may be at a higher risk of experiencing burnout compared to other healthcare professionals (Brandford & Reed, Citation2016; Ślusarz et al., Citation2022).

As expected, psychological morbidity also impacts nurses’ QoL (Babapour et al., Citation2022; Cecere et al., Citation2023), usually being accompanied by physical and mental symptoms, as result of prolonged occupational state of stress (Schaufeli et al., Citation2017). In addition to burnout, nurses report high rates of anxiety and depression (Young et al., Citation2011) resulting in absenteeism, conflicts at work, and poor mental QoL (Perry et al., Citation2015). Although the prevalence numbers of depression may vary across countries, previous studies found that 5.9% to 38% of nurses exhibited clinical depression (Chen et al., Citation2019; Choi et al., Citation2018; Huang et al., Citation2022), and 19.8% to 41.2% reported anxiety symptoms (Belayneh et al., Citation2021; Maharaj et al., Citation2018).

Occupational stress levels and emotional exhaustion have been associated with low levels of social support. Support from nurses’ colleagues, family, and friends not only contribute to stress reduction but may also prevent the onset of burnout (Velando-Soriano et al., Citation2020), although low social support has been associated with more vulnerability to burnout (Wood et al., Citation2022). Regarding QoL, social support, especially from spouses and coworkers, was found to have a positive effect on nurses’ QoL (Fradelos et al., Citation2014; Yan et al., Citation2022). Also, nurses’ higher levels of perceived social support have resulted in improved performance and less stress at work (Orgambídez-Ramos & Almeida, Citation2017).

Previous studies have highlighted the effect of career duration on nurses’ QoL. More professional experience allows nurses to better handle stress and the job demands, which may have a positive impact on mental QoL (Chang et al., Citation2011; Moradi et al., Citation2014). However, a longer career duration may also negatively impact nurses’ physical QoL due to caregiving demands and work shifts, over time (Chang et al., Citation2011; Moradi et al., Citation2014). According to Gillespie et al. (Citation2009), nurses with a long professional experience may mobilize resources and adopt more appropriate communication styles to deal with adversity. Thus, long career duration has been associated with a better response to emotional stress and less vulnerability to burnout (Marôco et al., Citation2016).

Previous research has focused on the mediating role of burnout in relation to job satisfaction, work conditions, stress, and coping strategies in the work context (e.g., Dall’Ora et al., Citation2020; Leiter & Maslach, Citation2009). However, few studies have addressed the indirect effect of burnout in the relationship between nursing’s professional variables, psychological variables, and mental and physical QoL. This study was theoretically based on the Maslach and Jackson’s model (Citation1981) which identifies burnout as the result of a lack of resources and requirements at work, with a negative impact on the caregiver’s physical QoL. Based on the model, this study examined the indirect effect of nurses’ burnout in the relationship between psychological variables, that acted as potential resources (social support) or distress (psychological morbidity), professional factors (career duration), and QoL.

The aim of this study was: (i) to assess the relationship between career duration, psychological morbidity, social support, burnout, and QoL, and (ii) to analyze the indirect effect of burnout in the previous relationship. It was hypothesized that more years of professional experience would be associated with better mental QoL, but worse physical QoL (H1); nurses with higher levels of psychological morbidity and burnout would report worse physical and mental QoL (H2); and nurses more satisfied with social support would report better physical and mental QoL (H3). Furthermore, it was hypothesized that burnout would play an indirect effect on the relationships between career duration/psychological morbidity/social support, and QoL (H4).

Methods

Participants and procedure

This study used a cross-sectional design. The study was conducted in four central hospitals in the North of Portugal with inpatient neurology services and was approved by the ethic committe of each hospital. After presenting the aims of the study, all nurses from the public neurology wards of the hospitals where data collection took place were invited by the researchers to voluntarily participate in the study. Recruitment took place in the neurology service, and those who agreed to participate signed an informed consent form prior to answer the questionnaires. From a population of 102 nurses, 96 agreed to participate and the remaining six were not available, due to incompatibility with their schedules. Data collection took place between June 2015 and August 2015.

Measures

Demographic questionnaire

This questionnaire evaluates nurses sociodemographic (e.g., age, gender, education level, marital status) and professional (e.g., years of professional experience, multi employment) variables.

Satisfaction with social support scale (SSSS; Pais Ribeiro, Citation1999)

This instrument consists of 15 items that reflect the satisfaction level with an individual’s social life, including satisfaction with family, friends, and social activities. Items are scored on a 5-point scale, and possible scores range from 15 to 75. Higher scores indicate more satisfaction with social support. SSSS is composed of four dimensions with the following Cronbach’s alphas: Satisfaction with friends (.83), Satisfaction with family (.74), Intimacy (.74), and Social activities (.64). In this study, only the total scale was used. In the original version the Cronbach’s alpha was .85, and in the present study was .75.

Depression, anxiety and stress scale (DASS-21; Pais Ribeiro et al., Citation2004)

DASS includes 21 items that assess psychological morbidity using three subscales (Depression, Anxiety, and Stress) with 7 items each. Participants rate the extent to which they had experienced each symptom over the past week on a 4-point severity/frequency scale. Total scores range between 0 and 21, and higher scores indicate more depression, anxiety, or stress levels. The Portuguese version of DASS reported Cronbach’s alphas of .85, .74, and .81 for Depression, Anxiety, and Stress subscales, respectively. In this study, only the total score was used, with a Cronbach alpha of .93.

Maslach burnout Inventory-Human services survey (MBI-HSS; Pinto, Citation2000)

This scale assesses the perceived burnout through three subscales: Personal accomplishment, Emotional exhaustion, and Depersonalization. Items are answered on a 7-point scale, with total scores ranging from 0 to 132. Higher scores on the Emotional exhaustion and Depersonalization subscales indicate a higher degree of burnout, although higher scores on the Personal accomplishment scale indicate less burnout. The total score was used in this study. Original Cronbach’s alphas for the three subscales ranged between .71 and .90, and in this study the internal consistency of the total scale was .79.

Short form health survey (SF-36; Ferreira, Citation2000)

SF-36 consists of 36 items that assess physical and mental health-related QoL through eight components: Physical function, Physical performance, Body pain, General health, Emotional performance, Social function, Mental health, and Vitality. SF-36 provides physical (PSM) and mental (MSM) summary measures with higher scores indicating better QoL. Both summary measures use a Likert scale with three, five, and six options. In the original study, Cronbach’s alphas for MSM and PSM were .88 and .92, respectively. In this study, the Cronbach’s alphas for both dimensions were .89.

Data analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics software (version 28.0). Demographic and professional characteristics of the sample were described using frequencies and percentages for categorical variables, and mean and standard deviation for continuous variables. Analysis of the relationships between career duration, psychological morbidity, social support, burnout, and QoL were performed using Pearson correlations. The hypothesized model, testing the indirect effect of burden between psychological morbidity and social support (exogenous variables) and QoL variables (endogenous variables), was evaluated using structural equation modeling with AMOS (version 28.0). Taking into consideration the number of predictors (career duration, psychological morbidity, satisfaction with social support, and burnout), a medium effect size, a desired power level of .80, and a significance level set at .05, the sample size required was 84 (Soper, Citation2019). All the corollaries to perform a path analysis were met (VIF < 5, tolerance > 0.20, eigenvalues not close to 0, and condition index values indicating non-collinearity).

Model fit was assessed using model chi-square (χ2) and relative chi-square (χ2/df), goodness-of-fit index (GFI), comparative fit index (CFI), standardized root mean square residual (SRMR), and root mean square error approximate (RMSEA). Adequate fit was defined as χ2 p-value over .05, χ2/df below 2, GFI and CFI over .95, SRMR below .08, and RMSEA below .07 (Hair et al., Citation2010). Standardized beta coefficients (β) were derived for each explanatory variable in order to allow for the comparison and estimation of the relative importance of each measure. The indirect effects were analyzed using the bootstrapping technique, considering 1000 samples and a 95% confidence interval (95% CI). A p value lower than .05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Sample characteristics

The sample included 92 nurses working in the neurological floors of four public hospitals. Participants were mainly women (77.2%) and were on average 36 years old (SD = 7.91). The participants’ sociodemographic characteristics are described in .

Table 1. Sample’s socio-demographic characteristics (N = 92).

Relationship between psychological morbidity, social support, career duration and QoL

Regarding nurses’ physical QoL, the results showed positive significant correlations with mental QoL (r = .638, p < .001) and satisfaction with social support (r = .227, p = .001), and negative significant correlations with psychological morbidity (r = −0.463, p < .001), burnout (r = −0.332, p < .001), and career duration (r = .638, p = .001). Mental QoL showed significant negative correlations with psychological morbidity (r = −.505, p < .001) and burnout (r = −0.539, p < .001), and a positive significant correlation with satisfaction with social support (r = .467, p < .001) ().

Table 2. Relationship between variables.

Path analysis model

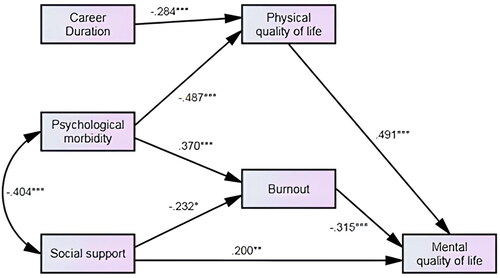

The global fit of the initial proposed model was not adequate, revealing poor fit indices and showing several non-significant pathways (covariances) between the variables (χ2 = 69.02, p < .001, χ2/df = 9.860, GFI = .796, CFI = .566, SRMR = .163, RMSEA = .312). Subsequently, the model was explored according to the modification indices and significance of path coefficients, resulting in the final adjusted model with a good global adjustment (): χ2 = 7.93, p = .339, χ2/df = 1.132, GFI = .972, CFI = .994, SRMR = .055, RMSEA = .038.

Figure 1. Path analysis with standardized direct effects and correlations.

*p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001.

NO COLOR.

The final model showed that career duration (β = −0.284, p < .001) and psychological morbidity (β = −0.487, p < .001) were negatively associated with physical QoL. Burnout was positively predicted by psychological morbidity (β = .370, p < .001), and negatively predicted by social support (β = −0.232, p < .05). Social support (β = .200, p < .01) showed a positive association with mental QoL.

Regarding indirect effects, burnout had an indirect effect in the relationship between psychological morbidity and mental QoL (β = −0.250, p < .01), and between satisfaction with social support and mental QoL (β = .206, p < .01). Physical QoL also had an indirect effect in the relationship between career duration and mental QoL (β = −0.150, p < .05), and between psychological morbidity and mental QoL (β = −0.295, p < .01) ().

Table 3. Standardized indirect effects identified by the path model.

Discussion

The goal of this study was to test a hypothesized model regarding QoL in nurses working in neurology wards in north Portugal. As hypothesized, physical and mental QoL showed negative relationships with psychological morbidity and burnout, and a positive association with satisfaction with social support. Career duration correlated significantly with physical QoL, but not with mental QoL. In fact, previous studies have stressed the increased risk for occupational diseases in nurses, as a result of the adverse impact of workplace and occupational hazards on their health and QoL (Babapour et al., Citation2022). Particularly, caring for patients with neurological disorders requires a vast knowledge regarding neurological conditions, as well as mastering a variety of skills (e.g., crisis intervention skills, communication skills, physical endurance to assist with mobility). Regarding mental QoL, there are divergent findings in the literature, as some studies found a negative effect of increased work experience in nurses’ mental health (Abarghouei et al., Citation2016; Ślusarz et al., Citation2022), and other studies indicate a higher prevalence of mental health problems, particularly, among younger nurses (Adriaenssens et al., Citation2015; Ning et al., Citation2020). A study in Portuguese nurses (Marôco et al., Citation2016) revealed that nurses and physicians with more years of professional experience were less impacted by burnout. This health outcome may be explained by the career experience gained over time, that may enable the acquisition of vital skills crucial for the management of stressful situations related to the profession. However, the physical efforts, the shift work, and multiple tasks that caring for neurological patients require, have a negative effect on physical QoL. The relationship between nurses’ career duration and their mental QoL is complex and other dimensions such as work conditions (e.g., shift duration, hospital facilities) may play a role as well. Further studies to address the impact of career duration on nurses’ mental QoL are needed. Overall, H1 was confirmed.

Regarding the indirect effects in the model, the results revealed that nurses’ career duration influenced mental QoL through physical QoL. The nursing profession is particularly prone to work strain due to a combination of work demands and few available resources, that often have a negative impact on nurses’ physical health (Babapour et al., Citation2022). In addition, nursing care involves high physical demands (e.g., transferring or repositioning patients), with a great impact on physical QoL over time (Chang et al., Citation2011), which may also have negative consequences on mental health.

Physical and mental health are fundamentally linked. The literature has shown the mutual influence that physical and mental health have on each other (e.g., Doan et al., Citation2023), therefore, it is not surprising that physical QoL had an indirect effect on the relationship between psychological morbidity and mental QoL. In fact, nurses are described as the most stressed, depressed, and anxious professionals among health care professionals (Chou et al., Citation2014; Ning et al., Citation2020) and, over time, psychological morbidity symptoms may lead to somatization and severe health problems (Chang et al., Citation2011), resulting in poor mental QoL.

Burnout had an indirect effect on the relationship between psychological morbidity and mental QoL. The literature shows a relationship between psychological morbidity and emotional exhaustion, which may have implications on the experience of burnout (Koutsimani et al., Citation2019). Furthermore, both, psychological morbidity and burnout are known to have harmful consequences on mental QoL (Babapour et al., Citation2022; Cecere et al., Citation2023; López-López et al., Citation2019). Given that neurological nurses are at serious risk of mental disorders and burnout (Ślusarz et al., Citation2022), it comes as no surprise that their mental QoL may be compromised. Overall, H2 was confirmed, and H4 was partially confirmed since burnout had no indirect effect in the relationship between psychological morbidity and physical QoL.

Satisfaction with social support had a direct effect on mental QoL, which is in line with extant literature indicating that social support provided by spouses, colleagues and family is a protective factor for nurses’ mental QoL (De Looff et al., Citation2019; Feng et al., Citation2018). Burnout had an indirect effect on the relationship between satisfaction with social support and mental QoL, but not regarding physical Qol, thus partially confirming H4. More satisfaction with social support predicted less burnout in nurses, as expected (Velando-Soriano et al., Citation2020; Wood et al., Citation2022), given that greater perceived social support is a source of security and support, particularly, in vulnerable times. Accordingly, previous studies have shown that poor supportive relationships and marital status may even contribute to the development of burnout syndrome in nurses (Cañadas-De la Fuente et al., Citation2018; Geuens et al., Citation2017). By reducing burnout, perceived social support may also enable healthcare professionals to deal more effectively with the emotional demands that taking care of neurological patients require, with better outcomes on mental QoL. Finally, although social support was expected to have a protective effect against physical and mental health problems (Fradelos et al., Citation2014; Lin et al., Citation2010; Yan et al., Citation2022), given that nurses in neurological wards experience high levels of burnout (Brandford & Reed, Citation2016; López-López et al., Citation2019), it makes sense that the influence of perceived social support was more visible on mental QoL.

Limitations

This study has some limitations that need to be acknowledged. The limited size of the sample, composed by nurses working in neurological wards requires caution regarding the generalization of findings. The cross-sectional design does not allow causal relationships between the variables. Therefore, it would be important to use longitudinal designs in future research. Also, this study did not evaluate work-related variables and, therefore, future research should assess job satisfaction, work shifts, communication and relationships within the healthcare team, and lifestyle behaviors in order to evaluate their potential moderator or mediator role in the hypothesized model. Additionally, since all instruments were self-report measures, further research should include specific physiological measures of burnout, depression, anxiety and stress. The comparison of nurses in neurology wards versus other wards is also warranted. Finally, data was collected almost five years before the pandemic and, since then, there has been changes and innovations in healthcare services, particularly in the nursing practice. Also, given that, after the COVID-19 pandemic, patients’ neurological difficulties and disabilities were more challenging for health professionals, it would be important to further investigate the QoL of nurses from neurological wards, after the pandemic.

Conclusion

According to the results, it is important to develop intervention strategies to decrease psychological morbidity and promote social support (e.g., from supervisors, colleagues, family and friends), particularly for those nurses with a longer working career in neurology wards. Since burnout had an indirect effect in the relationship between psychological morbidity and mental QoL, it is important that health care institutions focus on the prevention of burnout in their professional staff. As such, there should be a regular assessment of burnout and physical QoL in healthcare institutions, as part of their regular occupational medicine consultation.

In order to promote nurses’ QoL, interventions should also focus on social support (since it played a direct effect on mental QoL), stress management, teamwork, communication skills, and psychological interventions focused on coping skills to better handle stress.

This study focuses on data collected before the pandemic and, although it provides important clues on how to improve nurses’ QoL, it is essential to take account the most recent changes in healthcare services with the new challenges that followed. For example, at the beginning of 2024, health care services were reorganized and integrated into Local Healthcare Units that include primary, hospital, and continuing care under the same managment within the same geographical area (National Association of Public Health Pysicians (ANMSP, Citation2023). Integrated care poses new challenges for health professionals, and the new demands are a great opportunity to offer formal caregivers the services needed to promote their overall wellbeing.

Ethics approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institution and/or national research committee and with the Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Approval was obtained from the ethics committee of the Hospital Center of S. João.

Consent to participate

All participants who agreed to participate signed an informed consent form.

Authors’ contributions

Lima, S. was responsible for data acquisition, data interpretation, and manuscript preparation; Machado, J. C. was responsible for data analysis, data interpretation, and manuscript review; Vilaça, M. was responsible for data interpretation and manuscript review; Pereira, M. G. was responsible for the study design, data interpretation, and manuscript review and editing.

| Abbreviations and Acronyms | ||

| β | = | Standardized beta coefficients |

| CFI | = | Comparative fit index |

| CI95% | = | Bootstrap bias-corrected confidence interval at 95% (1000 samples), lower and upper |

| DASS | = | Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale |

| GFI | = | Goodness-of-fit index |

| M | = | Mean |

| MBI-HSS | = | Maslach Burnout Inventory-Human Services Survey |

| MSM | = | Mental summary measure |

| p | = | Statistical significance level |

| PSM | = | Physical summary measure |

| QoL | = | Quality of life |

| r | = | Correlation coefficients |

| RMSEA | = | Root mean square error approximate |

| SD | = | Standard deviation |

| SF-36 | = | Short Form Health Survey |

| SRMR | = | Standardized root mean square residual |

| SSSS | = | Satisfaction with Social Support Scale |

| χ2 | = | Model chi-square |

| χ2/df | = | Relative chi-square |

Acknowledgments

There were no other contributors to the article than the authors. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Code availability

C31; I31

Disclosure statement

The authors have no funding or conflicts of interest to disclose.

Data availability statement

The authors have full control of all primary data and they agree to allow the journal to review their data upon request.

References

- Abarghouei, M. R., Sorbi, M. H., Abarghouei, M., Bidaki, R., & Yazdanpoor, S. (2016). A study of job stress and burnout and related factors in the hospital personnel of Iran. Electronic Physician, 8(7), 2625–2632. doi:10.19082/2625

- Adriaenssens, J., De Gucht, V., & Maes, S. (2015). Determinants and prevalence of burnout in emergency nurses: A systematic review of 25 years of research. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 52(2), 649–661. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2014.11.004

- Associação Nacional dos Médicos em Saúde Pública (ANMSP) (2023, January 25). A criação das Unidades Locais de Saúde em Portugal: Desafios e perspetivas para a Saúde Pública [The development of Local Healthcare Units in Portugal: Challanges and Opportunities to Public Health]. https://www.anmsp.pt/post/unidade-locais-de-saude

- Babapour, A. R., Gahassab-Mozaffari, N., & Fathnezhad-Kazemi, A. (2022). Nurses’ job stress and its impact on quality of life and caring behaviors: A cross-sectional study. BMC Nursing, 21(1), 75. doi:10.1186/s12912-022-00852-y

- Belayneh, Z., Zegeye, A., Tadesse, E., Asrat, B., Ayano, G., & Mekuriaw, B. (2021). Level of anxiety symptoms and its associated factors among nurses working in emergency and intensive care unit at public hospitals in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. BMC Nursing, 20(1), 180. doi:10.1186/s12912-021-00701-4

- Bilal, A., & Ahmed, H. M. (2017). Organizational structure as a determinant of job burnout: An exploratory study on Pakistani pediatric nurses. Workplace Health & Safety, 65(3), 118–128. doi:10.1177/2165079916662050

- Brandford, A. A., & Reed, D. B. (2016). Depression in registered nurses: A state of the science. Workplace Health & Safety, 64(10), 488–511. doi:10.1177/2165079916653415

- Cañadas-De la Fuente, G. A., Ortega, E., Ramirez-Baena, L., De la Fuente-Solana, E. I., Vargas, C., & Gómez-Urquiza, J. L. (2018). Gender, marital status, and children as risk factors for burnout in nurses: A meta-analytic study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(10), 2102. doi:10.3390/ijerph15102102

- Cecere, L., de Novellis, S., Gravante, A., Petrillo, G., Pisani, L., Terrenato, I., Ivziku, D., Latina, R., & Gravante, F. (2023). Quality of life of critical care nurses and impact on anxiety, depression, stress, burnout and sleep quality: A cross-sectional study. Intensive & Critical Care Nursing, 79, 103494. doi:10.1016/j.iccn.2023.103494

- Chang, E. M., Daly, J., Hancock, K. M., Bidewell, J. W., Johnson, A., Lambert, V., & Lambert, C. E. (2011). The relationships among workplace stressors, coping methods, demographic characteristics, and health in Australian nurses. Journal of Professional Nursing, 22(1), 30–38. doi:10.1016/j.profnurs.2005.12.002

- Chen, J., Li, J., Cao, B., Wang, F., Luo, L., & Xu, J. (2019). Mediating effects of self-efficacy, coping, burnout and social support between job stress and mental health among Chinese newly qualified nurses. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 76(1), 163–173. doi:10.1111/jan.14208

- Choi, B. S., Kim, J. S., Lee, D. W., Paik, J. W., Lee, B. C., Lee, J. W., Lee, H. S., & Lee, H. Y. (2018). Factors associated with emotional exhaustion in South Korean nurses: A cross-sectional study. Psychiatry Investigation, 15(7), 670–676. doi:10.30773/pi.2017.12.31

- Chou, L. P., Li, C. Y., & Hu, S. C. (2014). Job stress and burnout in hospital employees: Comparisons of different medical professions in a regional hospital in Taiwan. BMJ Open, 4(2), e004185. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004185

- Dall’Ora, C., Ball, J., Reinius, M., & Griffiths, P. (2020). Burnout in nursing: A theoretical review. Human Resources for Health, 18(1), 41. doi:10.1186/s12960-020-00469-9

- De Looff, P., Didden, R., Embregts, P., & Nijman, H. (2019). Burnout symptoms in forensic mental health nurses: Results from a longitudinal study. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 28(1), 306–317. doi:10.1111/inm.12536

- Doan, T., Ha, V., Strazdins, L., & Chateau, D. (2023). Healthy minds live in healthy bodies – effect of physical health on mental health: Evidence from Australian longitudinal data. Current Psychology, 42(22), 18702–18713. doi:10.1007/s12144-022-03053-7

- Ebrahimi, H., Jafarjalal, E., Lotfolahzadeh, A., & Kharghani Moghadam, S. M. (2021). The effect of workload on nurses’ quality of life with moderating perceived social support during the COVID-19 pandemic. Work, 70(2), 347–354. doi:10.3233/WOR-210559

- Elovainio, M., Heponiemi, T., Kuusio, H., Jokela, M., Aalto, A. M., Pekkarinen, L., Noro, A., Finne-Soveri, H., Kivimäki, M., & Sinervo, T. (2015). Job demands and job strain as risk factors for employee wellbeing in elderly care: An instrumental-variables analysis. European Journal of Public Health, 25(1), 103–108. doi:10.1093/eurpub/cku115

- Feng, D., Su, S., Wang, L., & Liu, F. (2018). The protective role of self-esteem, perceived social support and job satisfaction against psychological distress among Chinese nurses. Journal of Nursing Management, 26(4), 366–372. doi:10.1111/jonm.12523

- Ferreira, P. L. (2000). Development of the Portuguese version of MOS SF-36. Part I. Cultural and linguistic adaptation. Acta Medica Portuguesa, 13(1-2), 55–66.

- Fradelos, E., Mpelegrinos, S., Mparo, C. H., Vassiloupoulou, C. H., Argyrou, P., Tsironi, M., Zyga, S., & Theofilou, P. (2014). Burnout syndrome impacts on quality of life in nursing professionals: The contribution of perceived social support. Progress in Health Sciences, 4, 102–109.

- Geuens, N., Van Bogaert, P., & Franck, E. (2017). Vulnerability to burnout within the nursing workforce-The role of personality and interpersonal behaviour. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 26(23–24), 4622–4633. doi:10.1111/jocn.13808

- Gillespie, B. M., Chaboyer, W., & Wallis, M. (2009). The influence of personal characteristics on the resilience of operating room nurses: A predictor study. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 46(7), 968–976. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2007.08.006

- Hair, J. F., Black, W., Babin, B., & Anderson, R. (2010). Multivariate data analysis (7th ed.). Prentice Hall.

- Huang, H., Xia, Y., Zeng, X., & Lü, A. (2022). Prevalence of depression and depressive symptoms among intensive care nurses: A meta-analysis. Nursing in Critical Care, 27(6), 739–746. doi:10.1111/nicc.12734

- Johnson, J., Hall, L. H., Berzins, K., Baker, J., Melling, K., & Thompson, C. (2018). Mental healthcare staff well-being and burnout: A narrative review of trends, causes, implications, and recommendations for future interventions. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 27(1), 20–32. doi:10.1111/inm.12416

- Khatatbeh, H., Pakai, A., Al-Dwaikat, T., Onchonga, D., Amer, F., Prémusz, V., & Oláh, A. (2022). Nurses’ burnout and quality of life: A systematic review and critical analysis of measures used. Nursing Open, 9(3), 1564–1574. doi:10.1002/nop2.936

- Koutsimani, P., Montgomery, A., & Georganta, K. (2019). The relationship between burnout, depression, and anxiety: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 284. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00284

- Lee, Y. K., & Yusof, M. P. (2018). Quality of life among nurses in primary healthcare clinics in the health district of Petaling, Selangor. International Journal of Public Health and Clinical Sciences, 5(5), 57–67. doi:10.32827/ijphcs.5.5.57

- Leiter, M. P., & Maslach, C. (2009). Nurse turnover: The mediating role of burnout. Journal of Nursing Management, 17(3), 331–339. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2834.2009.01004.x

- Lin, H. S., Probst, J. C., & Hsu, Y. C. (2010). Depression among female psychiatric nurses in southern Taiwan: Main and moderating effects of job stress, coping behaviour and social support. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 19(15–16), 2342–2354. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2702.2010.03216.x

- López-López, I. M., Gómez-Urquiza, J. L., Cañadas, G. R., De la Fuente, E. I., Albendín-García, L., & Cañadas-De la Fuente, G. A. (2019). Prevalence of burnout in mental health nurses and related factors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 28(5), 1032–1041. doi:10.1111/inm.12606

- Maharaj, S., Lees, T., & Lal, S. (2018). Prevalence and risk factors of depression, anxiety, and stress in a cohort of Australian Nurses. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(1), 61. doi:10.3390/ijerph16010061

- Marôco, J., Marôco, A. L., Leite, E., Bastos, C., Vazão, M. J., & Campos, J. (2016). Burnout em Profissionais de Saúde Portugueses: Uma Análise a Nível Nacional [Burnout in Portuguese Healthcare Professionals: An Analysis at the National Level]. Acta Médica Portuguesa, 29(1), 24–30. doi:10.20344/amp6460

- Maslach, C., & Jackson, S. E. (1981). The measurement of experienced burnout. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 2(2), 99–113. doi:10.1002/job.4030020205

- Miyamoto, Y., Tachimori, H., & Ito, H. (2010). Formal caregiver burden in dementia: Impact of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia and activities of daily living. Geriatric Nursing, 31(4), 246–253. doi:10.1016/j.gerinurse.2010.01.002

- Moradi, T., Maghaminejad, F., & Azizi-Fini, I. (2014). Quality of working life of nurses and its related factors. Nursing and Midwifery Studies, 3(2), e19450. doi:10.5812/nms.19450

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2021). The future of nursing 2020-2030: Charting a path to achieve health equity. The National Academies Press. doi:10.17226/25982

- Ning, X., Yu, F., Huang, Q., Li, X., Luo, Y., Huang, Q., & Chen, C. (2020). The mental health of neurological doctors and nurses in Hunan Province, China during the initial stages of the COVID-19 outbreak. BMC Psychiatry, 20(1), 436. doi:10.1186/s12888-020-02838-z

- Orgambídez-Ramos, A., & Almeida, H. (2017). Work engagement, social support, and job satisfaction in Portuguese nursing staff: A winning combination. Applied Nursing Research: ANR, 36, 37–41. doi:10.1016/j.apnr.2017.05.012

- Pais Ribeiro, J. L. (1999). Escala de Satisfação com o Suporte Social (ESSS) [Satisfaction with Social Support Scale (SSSS.)]Análise Psicológica, 3, 547–558.

- Pais Ribeiro, J. L., Honrado, A., & Leal, I. (2004). Contribuição para o estudo da adaptação Portuguesa das Escalas de Ansiedade, Depressão e Stress (EADS) de 21 itens de Lovibond e Lovibond [Contribution to the adaptation study of the portuguese adaptation of the Lovibond and Lovibond Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scales (DASS-21) with 21 items]. Psicologia, Saúde & Doenças, 5, 229–239.

- Perry, L., Lamont, S., Brunero, S., Gallagher, R., & Duffield, C. (2015). The mental health of nurses in acute teaching hospital settings: A cross-sectional survey. BMC Nursing, 14(1), 15. doi:10.1186/s12912-015-0068-8

- Pinto, A. M. (2000). Burnout profissional em professores portugueses: representações sociais, incidência e preditores [Professional burnout in. Portuguese professors: social representations, incidence and preditors]. [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. University of Lisbon.

- Schaufeli, W. B., Maslach, C., & Marek, T. (2017). Professional burnout: Recent developments in theory and research. Taylor & Francis.

- Serinkan, C., & Kaymakçi, K. (2013). Defining the quality of life levels of the nurses: A study in pamukkale university. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 89, 580–584. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.08.898

- Ślusarz, R., Filipska, K., Jabłońska, R., Królikowska, A., Szewczyk, M. T., Wiśniewski, A., & Biercewicz, M. (2022). Analysis of job burnout, satisfaction and work-related depression among neurological and neurosurgical nurses in Poland: A cross-sectional and multicentre study. Nursing Open, 9(2), 1228–1240. doi:10.1002/nop2.1164

- Soper, D. S. (2019). A-priori sample size calculator for multiple regression [Software]. https://www.danielsoper.com/statcalc/calculator.aspx?id=1

- Tonso, M. A., Prematunga, R. K., Norris, S. J., Williams, L., Sands, N., & Elsom, S. J. (2016). Workplace violence in mental health: A Victorian Mental Health Workforce Survey. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 25(5), 444–451. doi:10.1111/inm.12232

- Velando-Soriano, A., Ortega-Campos, E., Gómez-Urquiza, J. L., Ramírez-Baena, L., De La Fuente, E. I., & Cañadas-De La Fuente, G. A. (2020). Impact of social support in preventing burnout syndrome in nurses: A systematic review. Japan Journal of Nursing Science: JJNS, 17(1), e12269. doi:10.1111/jjns.12269

- Woo, T., Ho, R., Tang, A., & Tam, W. (2020). Global prevalence of burnout symptoms among nurses: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 123, 9–20. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2019.12.015

- Wood, R. E., Brown, R. E., & Kinser, P. A. (2022). The connection between loneliness and burnout in nurses: An integrative review. Applied Nursing Research: ANR, 66, 151609. doi:10.1016/j.apnr.2022.151609

- World Health Organization. (2020). State of the World’s Nursing 2020: Investing in Education, Jobs and Leadership. https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/331677/9789240003279-eng.pdf?sequence=1

- Yan, J., Wu, C., He, C., Lin, Y., He, S., Du, Y., Cao, B., & Lang, H. (2022). The social support, psychological resilience and quality of life of nurses in infectious disease departments in China: A mediated model. Journal of Nursing Management, 30(8), 4503–4513. doi:10.1111/jonm.13889

- Young, J. L., Derr, D. M., Cicchillo, V. J., & Bressler, S. (2011). Compassion satisfaction, burnout, and secondary traumatic stress in heart and vascular nurses. Critical Care Nursing Quarterly, 34(3), 227–234. doi:10.1097/CNQ.0b013e31821c67d5