Abstract

This study examines the effectiveness of expressive writing in reducing work stress. Expressive writing involves structured written exercises of self-disclosure for cognitive and affective processing of stressful experiences over several writing sessions. Using a 3x3 mixed design, we examined the effects of the intervention on work stress as well as work-related motivation and attitudes in 62 German participants. We found a sex-specific effect in the significant reduction of exhaustion in men in the experimental group. In contrast, women in the control group showed significantly higher levels of exhaustion. This effect was not found for women in the experimental group. Despite the limitations of our research in terms of sample differences in baseline levels, our research identifies an alleviating effect of expressive writing on emotional exhaustion as the core facet of burnout. Future research should specifically select individuals with higher levels of stress to address the limitations mentioned.

Introduction

Work stress is a thoroughly studied phenomenon. Its detrimental effects on employees’ mental and physical health (Madsen et al., Citation2017) and work-related attitudes and behavior (Mazzola & Disselhorst, Citation2019) seem widely acknowledged. The issue of work stress is typically addressed through work design (e.g., flexibilization of working conditions) or stress management interventions (Holman et al., Citation2018; De Wijn & Van Der Doef, Citation2022).

One stress management intervention that is gaining increased attention is expressive writing (Caputo et al., Citation2022). Expressive writing is a structured written emotional disclosure intervention designed to help participants process stressful thoughts and feelings related to specific topics or events (Caputo et al., Citation2022; Lukenda et al., Citation2023). In professional contexts, expressive writing was applied to address issues like organizational injustice (Saldanha & Barclay, Citation2021), improving mental health (Procaccia et al., Citation2021), and enhancing employee resources (Round et al., Citation2022). To deepen the understanding of expressive writing in organizational settings, Lukenda et al. (Citation2023) emphasized key enhancements in this field of research. Firstly, incorporating follow-up measurements is crucial to assess long-term effects. Currently, only a few studies employ pre-, post-, and follow-up measurements to analyze if the effect of expressive writing on work stress is durable (Ashley et al., Citation2013; Michailidis & Cropley, Citation2019). Secondly, it is recommended to emphasize work-related variables (e.g., burnout, work engagement, commitment) to pinpoint the specific effects of expressive writing on work experiences and behaviors. Current research tends to focus on mental health or social variables (Procaccia et al., Citation2021; Saldanha & Barclay, Citation2021). Although considered dependent variables in some studies (Cosentino et al., Citation2021; Round et al., Citation2022), organizational outcomes have not yet been the primary focus. This is evident in that theoretical explanations for significant findings are confined to the expressive writing paradigm without establishing a connection to the work stress literature.

Our current research tries to address these research gaps by investigating expressive writing’s influence on work stress in a 3 × 3 factorial design. We measure work stress through burnout, irritation, and psychosomatic complaints in a non-clinical context, low positive and high negative affectivity, low life satisfaction, and general well-being. Additionally, we examine expressive writing’s impact on work-related attitudes, motivational constructs, and workplace behavior. Our theoretical foundation integrates expressive writing into a work stress framework, contributing to a comprehensive understanding of the intervention in the professional field. The following sections will define expressive writing, outline theoretical foundations, describe the research design and sample, and present and discuss results.

Work stress

In occupational psychology, a distinction is made between work stress and strain, with stress referring to environmental demands and strain encompassing the personal health consequences of these demands (Richter, Citation2000). However, from a clinical perspective, this distinction is less pronounced, as stress is often equated with psychological distress, characterized by emotional suffering (Procaccia et al., Citation2021).

A reconciling perspective is offered by the Transactional Stress Model (Lazarus & Folkman, Citation1987), which conceptualizes stress as a negative emotional response arising from cognitive appraisal processes through which environmental factors are evaluated as threatening and exceeding an individual’s coping abilities.

Within the expressive writing paradigm, “stress” is commonly used to describe this perspective, whereas “strain” would be the more appropriate term from an organizational psychology standpoint. To maintain uniform terminology within the paradigm, we adopt the term “work stress”, acknowledging its broader implications beyond mere psychological distress. Based on the transactional stress model, work stress is therefore defined as an evaluation of demands within the work environment as threatening and surpassing coping abilities, leading to emotional suffering and potential health implications.

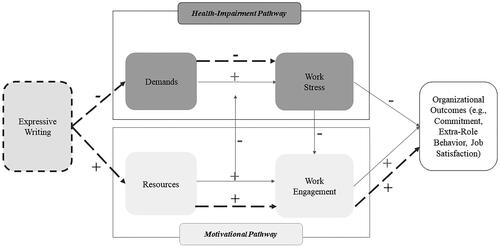

The Job Demand-Resource (JD-R) Model (Bakker & Demerouti, Citation2017; Demerouti et al., Citation2001) can provide theoretical support for the antecedents and effects of work stress. It categorizes working conditions into job demands and resources. Job demands, such as customer interactions and conflict, require physical or psychological efforts, while resources, like skill variety or feedback, support personal growth and help to handle demands. These conditions trigger two interconnected but distinct pathways: the health-impairment and motivational pathways. These pathways are depicted in the visualization of the research model in .

Figure 1. Visual presentation of the research model. The pathways within the boxes represent the assumptions of the JD-R model (Bakker & Demerouti, Citation2017). The dotted pathway illustrates the anticipated effect of expressive writing within this framework.

In the health-impairment pathway, heightened job demands lead to strain, resulting in exhaustion and health complaints. Through the motivational pathway, job resources enhance work engagement, characterized by vigor, dedication, and absorption, as the opposite of strain (Schaufeli et al., Citation2002). The interplay between the pathways is evident in the protective role of resources against the detrimental effects of demands and the adverse impact of stress on work engagement.

Work stress is known to impact employee attitudes and behavior negatively (Morrissette & Kisamore, Citation2020; Siltaloppi et al. Citation2009), while work engagement is linked to positive job attitudes such as job satisfaction and commitment, as well as to extra-role behaviors like Organizational Citizenship Behavior (OCB) (Saks, Citation2019).

Commitment refers to employees’ identification, involvement, and loyalty to their organization (Allen & Meyer, Citation1990), while job satisfaction encompasses an individual’s holistic, subjective assessment of their work (Podsakoff et al., Citation2007). OCB refers to voluntary workplace behaviors beyond formal job demands and is defined via the dimensions of Altruism, Conscientiousness, Courtesy, and Sportsmanship (Currall & Organ, Citation1988).

Work stress and expressive writing

A theoretical rationale is provided for the value of expressive writing as a work stress management intervention based on the antecedents and consequences of work stress outlined above. Expressive writing, defined as a structured written emotional disclosure writing exercise, helps individuals confront challenging emotions related to stressful events or topics, regulate unprocessed thoughts and feelings, and enhance overall well-being (Caputo et al., Citation2022). Extensively studied since the 1980s and subjected to meta-analyses (Pavlacic et al., Citation2019), expressive writing generally positively affects well-being, with few exceptions (Reinhold et al., Citation2018). Reinhold et al. (Citation2018) suggest variations may be due to factors like the implementation protocol (e.g., longer sessions seem more beneficial) and participant characteristics (e.g., baseline level stress, sex, and personality).

Caputo et al. (Citation2022) meta-analytically replicate these findings in the organizational context, showing positive effects, especially on affect variables. Lukenda et al.'s (Citation2023) systematic literature review supports these findings. Nine out of thirteen studies investigated in the review reported significant positive effects of expressive writing, influencing mental health variables (Cosentino et al., Citation2021; Procaccia et al., Citation2021), personal resources (Kirk et al., Citation2011; Saldanha & Barclay, Citation2021), and organizational outcomes (Cosentino et al., Citation2021; Round et al., Citation2022). For instance, Procaccia et al. (Citation2021) found that expressive writing reduced general psychopathology among healthcare personnel during the COVID-19 pandemic. Cosentino et al. (Citation2021) observed improvements in sleep disturbance, anger, intrusiveness, and hyperarousal in palliative care staff. Kirk et al. (Citation2011) noted increased self-efficacy in employees with a low or medium baseline level. Saldanha & Barclay (Citation2021) showed increased resilience and willingness to forgive after an organizational injustice. These benefits extend to organizational outcomes, with Cosentino et al. (Citation2021) reporting positive effects on continuance commitment and Round et al. (Citation2022) identifying higher job satisfaction among expressive writing participants.

The effects of expressive writing can be attributed to cognitive (Alparone et al., Citation2015; Bourassa et al., Citation2017) and emotional processing (Robertson et al. Citation2021). The premise of cognitive processing is introduced early in the paradigm through inhibition theory (Pennebaker & Beall, Citation1986), which posits that unprocessed thoughts and feelings can burden the nervous system and induce strain. Expressive writing helps to alleviate this load by processing the previously unprocessed cognitions and affects through writing and therefore reducing cognitive load (Pennebaker & Beall, Citation1986). Subsequent research highlights the significant role of linguistic manifestations of this process in essay structure and word choice (Alparone et al., Citation2015; Bourassa et al., Citation2017). Increased coherence is associated with indicators of better heart health (Bourassa et al., Citation2017), and higher use of cognitive words appears to impact anxiety positively (Alparone et al., Citation2015). This is explained by the fact that improved coherence helps to integrate unprocessed thoughts and feelings into autobiographical memory, thereby reducing mental stress (Bourassa et al., Citation2017). Linguistically, this integration process is supported by increased cognitive words (Alparone et al., Citation2015).

Emotional processing posits that repeatedly addressing emotionally stressful experiences can lead to habituation, thereby diminishing the stress response when faced with similar situations (Sloan & Marx, Citation2018). This mechanism was initially identified by Sloan et al. (Citation2005), who found that writing about the same traumatic event has a more significant effect on well-being than writing about different events. Recent experimental research further underlines that this habituation process also manifests linguistically. Robertson et al. (Citation2021) demonstrated that using the first-person singular within expressive writing essays is associated with a significant reduction in anxiety. The authors explain this by stating that using the first-person singular denotes a confrontation with oneself, which can be seen as a habituation process, thus attenuating the intense anxiety response to the stressor.

To theoretically substantiate the impact of expressive writing on work stress, the laid-out theoretical assumptions are integrated into the JD-R model (), from which a research model and testable hypotheses are derived.

It is assumed that expressive writing influences the motivational and health-impairment pathways (, left). Regarding the health-impairment pathway (, upper part), it is proposed that participants consciously address stress-inducing job demands within expressive writing sessions, thereby triggering an integration process of unprocessed thoughts and feelings and a habituation process against the demands reflected upon. Consequently, capacity is liberated, and the overall load is reduced. Moreover, when faced again with stress-inducing job demands, whether mentally or in the actual work environment, the demands are perceived as less threatening, which reduces the direct negative effect of job demands on work stress. This effect is illustrated in by the dotted pathway within the health-impairment pathway (upper part).

Given this theoretical framework, the study posits that a measurable reduction in work stress should occur from pre- to post-measurement/follow-up in the expressive writing condition. This expected outcome forms the basis of our first hypothesis and is illustrated by the dotted upper path in . Accordingly, we hypothesize:

Hypotheses 1: A reduction of participants’ work stress from pre- to post-measurement/follow-up measurement will occur in the expressive writing condition but not in the control and comparison condition.

According to the JD-R model, increased resources enhance work engagement via the motivational pathway (, lower part). Since expressive writing serves as a new practical resource for employees and simultaneously liberates mental resources through cognitive and emotional processing, a general increase in resources is anticipated. In line with the JD-R model, this increase is expected to manifest as heightened work engagement among employees. illustrates this assumption through the lower dotted path. Building on this theoretical foundation, the second hypothesis is proposed:

Hypotheses 2: An increase in participants’ work engagement from pre- to post-measurement/follow-up measurement will occur in the expressive writing condition but not in the control and comparison condition.

Heightened work engagement is correlated with positive outcomes on attitudes and behaviors toward the employer (Saks, Citation2019). This correlation suggests that improvements in work engagement could translate into better attitudes and behaviors within the workplace. Therefore, assuming that expressive writing enhances work engagement, it should similarly foster more positive attitudes and behaviors toward the employer (, right dotted path). This leads us to the third hypothesis:

Hypotheses 3: An increase in participants’ positive attitudes and behavior toward their employer from pre- to post-measurement/follow-up measurement will occur in the expressive writing condition but not in the control and comparison condition.

Method

Participants

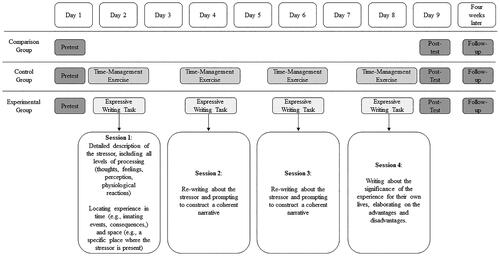

The current study was conducted as a 3 × 3 factorial randomized controlled trial, incorporating a within-subject factor of measurement time points (pre- and post-test, and follow-up) and a between-subject factor of group assignment (comparison, control and experimental groups). depicts the study’s design. A total of 62 participants were randomly assigned to a comparison group (n = 21), a control group (n = 18), or an experimental group (n = 23) (, left column). At the pre- and post-test, 62 participants were involved, averaging M = 28.44 years old (SD = 7.75) with an average employment duration of M = 4.99 years (SD = 5.90). Forty-eight participants studied alongside their professional employment. The most common industries represented were manufacturing (n = 13) and the service sector (n = 11). Participants worked M = 37.66 h per week (SD = 13.10) and had an average of M = 10.88 family working hours (SD = 11.92). Sex distribution was 61% for females and 39% for males; no person with a non-binary gender identity took part in the study. From the post-test to the follow-up, nineteen participants dropped out. Of the remaining 43 participants, 11 were in the comparison group, 12 in the control group, and 20 in the experimental group.

Design and procedure

First, we describe the study’s design very briefly. depicts the 3 × 3 factorial randomized controlled trial with the within-subject factor measurement time points and the between-subject factor of group assignment. The experimental group engaged in four expressive writing sessions with a duration of 20 min, the control group received a time management intervention at the same interval and duration, and the comparison group underwent no treatment. Evaluations were conducted for all three groups at baseline (pretest), immediately post-intervention (post-test), and four weeks post-intervention (follow-up). The same questionnaires (see Measures) were utilized at all three measurement time points. By incorporating the three measurement time points, we aim to evaluate the direct effect of expressive writing on work stress and its durability. By examining differences in manipulation through the experimental conditions, we also investigate whether potential changes in work stress levels can be attributed to emotional and cognitive processing. The study adhered to ethical guidelines, with approval from the Ethics Committee of the German Police University (approval number DHPol-EthK.2022.Mey1).

Second, we provide a very detailed description of the procedure of the study, including the recruitment of the sample and the procedure of data collection. The study took place in North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany, from December 2022 to March 2023. Participants were recruited through the researchers’ networks, encompassing academic colleagues, LinkedIn contacts, and students from three applied sciences universities. This approach resulted in a convenience sample. Recruitment methods encompassed digital bulletin board postings and short presentations at lectures, inviting individuals to contact the study team if interested in participating proactively. The bulletins disclosed only the occurrence of a stress-management intervention and the occurrence of three measurement time points, withholding details about the experimental conditions.

Participants included in the study must be actively employed, working at least 20 h per week. Exclusion criteria specified individuals under 18 and those undergoing acute therapy to avoid influencing therapy outcomes. The inclusion and exclusion criteria were communicated to potential participants through the notice board and verified in the questionnaire.

After participants contacted the study management via email, they were randomly assigned to one of the three experimental conditions through random selection. The comparison group was informed about participating in three measurement points before the intervention, which served as a cover story. With the participants of the experimental and control groups, Zoom meetings were scheduled for the pretest, the writing sessions, and the post-test.

The study began with the pretest on the first day (, column “Day 1”). The survey for baseline measurement was available to all participants via a digital link. All important information for completing the questionnaire was made available via a written introduction within the digital application. It was also pointed out that all questions were mandatory, meaning that all items had to be answered to submit a completed questionnaire. While the experimental and control groups completed the questionnaire in the Zoom call with the study manager present, the comparison group completed it independently.

The next day (, columns “Day 2” - “Day 8”), the experimental and control groups started the intervention phase. Over the next seven days, four writing sessions of 20 min each were conducted. They took place every second day on Zoom calls with the study manager present. The instructions were sent to the participants individually via a link in an email before their writing session. Therefore, participants were blind with concern about their group assignment, and several participants from different groups could work on the same Zoom call. The experimental group practised expressive writing, guided by instructions adapted from Pennebaker (Citation1997). The original instructions included the request to write for 20 min without interruption about a stressful event or topic and to deal intensively with thoughts and feelings. They also contained the instruction not to worry about spelling and orthography. This essence was adopted. However, the request was added that the topic of the essay should relate to the professional context. Also, a narrative element was added. Participants were prompted to approach their topic as if crafting a story, considering elements like settings, periods, characters, and their relationships. For Days 1 to 3 (), the instructions remained consistent. On Day 4, participants were additionally prompted to reflect on possible positive aspects of their experience. The control group was assigned a time management task, focusing on daily, weekly, monthly, and yearly schedules, a commonly used task for control groups in occupational settings (Lukenda et al., Citation2023). The comparison group did not receive any treatment during the seven-day intervention period.

On Day 9 (, column “Day 9”), at the end of the intervention phase, the post-test was carried out. Participants, again, responded to the same online survey as in the pretest. Four weeks later (, column “Four weeks later”), the follow-up measurement took place. The same online survey was again made available to all three groups. For the follow-up-measurement no Zoom calls took place.

The manipulation was controlled in the experimental and control groups through the Zoom calls and in the comparison group through mandatory feedback via e-mail after the questionnaires had been completed.

At the end of the study, all participants were informed about their group membership, and the control and comparison groups had the opportunity to participate in the expressive writing exercise. Students who took part in the study were able to collect class credit.

Measures

Work Stress is assessed through burnout, psychosomatic complaints (non-clinical), irritability, negative affectivity, low life satisfaction, and low general well-being.

Burnout is assessed using the Maslach Burnout Inventory (German version, MBI-D) by Büssing & Perrar (Citation1992), which includes exhaustion (5 items), cynicism (5 items), and personal accomplishment (6 items). Participants rate frequency from “never” to “daily” on a seven-point Likert scale. Cronbach’s alphas are α = .79 for exhaustion, α = .61 for cynicism, and α = .73 for personal accomplishment. High exhaustion and cynicism, and low personal accomplishment, indicate greater work stress. Psychosomatic complaints were assessed using a shortened version of Mohr & Müller’s (Citation2004) scale, selecting 11 of 20 items based on high discriminatory power (> 0.70) and following item exclusion recommendations by Kleka & Soroko (Citation2018). Symptoms’ frequency was rated on a five-point Likert scale from “never” to “almost daily.” The scale’s reliability, verified by Cronbach’s alpha, showed values of α = .78, α = .84, and α = .87 at three measurement points. It is assumed that increased psychosomatic complaints are linked to increased work stress.

Irritation is measured through cognitive (3 items) and emotional (5 items) aspects using an 8-item scale, demonstrating high reliability (Cronbach’s alpha between α =.84 and .91). Participants responded using a seven-point Likert scale, where “does not apply at all” denotes the lowest response and “applies almost completely” signifies the highest response. High irritation is associated with high work stress.

Affectivity is assessed using the German Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS), featuring 20 items that describe various affect states. Participants gauge the intensity of their feelings over a set period using a scale from “1 = not at all” to “5 = extremely.” The scale’s reliability, indicated by item factor loadings between λ = .43 and λ = .89, confirms that the items effectively capture the constructs of negative and positive affectivity (Janke & Glöckner-Rist, Citation2013). Higher work stress is linked to increased negative and decreased positive affectivity.

Life satisfaction is measured by the German Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS), a five-item scale with responses ranging from “1 = strongly disagree” to “7 = strongly agree.” Its reliability, Cronbach’s alpha, is between α = .84 and .87 (Glaesmer et al., Citation2011). Higher work stress is expected to lower life satisfaction.

General well-being is assessed with the German EUROHIS-QOL scale (Schmidt et al., Citation2005), which evaluates life quality aspects through 8 items on a five-point scale (α = .80), ranging from “1 = not at all” to “5 = completely”. Higher work stress is anticipated to lower well-being.

We assessed work engagement through the German abbreviated version of the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (UWES) (Schaufeli et al., Citation2003), which comprises 9 items. Participants evaluated how frequently they experience vigor, dedication, and absorption using a 7-point Likert scale from “0 = never” to “6 = always.” The scale’s internal consistency, indicated by Cronbach’s alpha, has consistently been reported around α = .90 (Demerouti et al., Citation2001).

To measure commitment, we used a shortened version of the German Organizational Commitment Questionnaire (OCQ-G) by Maier & Woschée (Citation2002). We selected ten of the original fifteen items based on their high discriminative power (> 0.70), in line with the methodology recommended by Kleka & Soroko (Citation2018). Participants rated their agreement with each statement on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from “1 = strongly disagree” to “5 = strongly agree.” The reliability of our shortened scale was confirmed by Cronbach’s alpha values of α = .80, α = .85, and α = .89, respectively.

Job satisfaction was gauged with a single-item measure from Wanous et al. (Citation1997) on a five-point scale from “1 = dissatisfied” to “5 = very satisfied,” showing a strong positive correlation (r = .67) with the construct it aims to measure.

Organizational Citizenship Behavior (OCB) was measured using the FELA-S by Staufenbiel & Hartz (Citation2000), encompassing four OCB subscales and Civic Virtue, each with five items rated on a seven-point scale from “1 = not at all true” to “7 = completely true.” Reported reliabilities for the subscales ranging from α = .52 to α = .72, indicating moderate to acceptable reliability (Gerhardt et al., Citation2011).

The demographic and employment-related variables age, length of employment, working hours, and family working hours were collected as control variables. Participants provided these variables using a free-text field, allowing them to enter the corresponding metric freely (e.g., years, hours). Sex and industry were collected as categorical variables, with participants selecting their sex from options “female,” “male,” or “diverse” and their industry from categories including administration, trade, industry, media, tourism, real estate, health, services, finance, e-commerce, telecommunications, learning and teaching, agriculture, or other.

Statistical analysis

First, we conducted a descriptive statistical analysis to identify potential variations in data structure by exploring the distribution of baseline levels across the three experimental conditions. Baseline levels of dependent variables were tested for deviations from normal distribution using Shapiro-Wilk tests. Additionally, multivariate ANOVA was performed to identify group differences in baseline levels.

Second, we conducted a 3 × 3 repeated-measures Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) to investigate the influence of expressive writing on the dependent variables. This analysis considered the within-subject factor measurement time point and the between-subject factor group, considering the control variables as covariates. All statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics Version 27 (Citation2022) with an alpha level set at α < 0.05. Before proceeding with the ANOVA, a thorough assessment of the assumptions of normality and sphericity was conducted to validate the integrity of the analysis. The results from Mauchly’s test either confirmed the assumption of sphericity or prompted the application of the Greenhouse-Geisser correction when it was violated.

Results

Descriptive statistical analysis

In the experimental group, deviations from normal distribution are evident in exhaustion (W = 0.90, p = 0.025) and cynicism (W = 0.90, p = 0.020), both showing right-skewedness (skewness: exhaustion = 0.77, cynicism = 1.10). Positive affectivity (W = 0.91, p = 0.049) and negative affectivity (W = 0.86, p = 0.004) also deviate from the normal distribution. Positive affectivity displays a left-skewed pattern (γ = −0.08), while negative affectivity shows a right-skewed distribution (γ = 1.24).

In the control group, deviations from the normal distribution were observed for negative affectivity (W = 0.85, p = 0.009) and general well-being (W = 0.89, p = 0.034). Both displayed a right-skewed distribution (negative affectivity: γ = 1.45, general well-being: γ = 0.73).

The comparison group showed deviations from the normal distribution in the variables: Personal accomplishments (W = 0.85, p = 0.005), general well-being (W = 0.84, p = 0.034), negative affectivity (W = 0.89, p = 0.018), and psychosomatic complaints (W = 0.84, p = 0.003). Personal accomplishments (γ = 0.56) and negative affectivity (γ = 1.15) showed a right-skewed departure from normal distribution, while general well-being (γ = −1.37) was a left-skewed.

Group differences between the experimental, control, and comparison group at baseline were tested for significance using an ANOVA. The results indicate a significant group difference in life satisfaction (F(2, 59) = 5.09, p = 0.009). Life satisfaction is significantly higher in the experimental group (M = 5.27, SD = 0.94) compared to the comparison group (M = 4.28, SD = 1.24). The comparison between the experimental and control groups revealed no significant differences.

Concerning the work attitudes and behavior measures, only job satisfaction significantly deviated from the normal distribution in the experimental group (W = 0.80, p < 0.001), control group (W = 0.89, p = 0.033), and comparison group (W = 0.88, p = 0.012). In the experimental and control groups, this deviation was left-skewed (experimental group: γ = −1.40, control group: γ = −0.27). In the comparison group, a right-skewed distribution (γ = 0.08) was found.

Analyzing the distribution parameters of the OCB variables, both the control and comparison groups show no significant deviations from the normal distribution across all variables. However, the experimental group exhibits a left-skewed deviation for sportsmanship (γ = −0.56) (W = 0.91, p = 0.044) and altruism (γ = −0.88) (W = 0.865, p = 0.005).

Furthermore, an ANOVA revealed significant mean differences in conscientiousness and civic virtues between the experimental conditions. The experimental and control groups significantly differed from the comparison group in terms of baseline conscientiousness levels (F(2, 59) = 5.30, p = 0.005), with the comparison group reporting lower conscientious behavior. Additionally, the comparison group significantly differed from the experimental group concerning civic virtues (F(2, 59) = 4.41, p = 0.016), indicating fewer behaviors associated with civic virtues in the comparison group.

In summary, the baseline analysis reveals non-normal distributions across all groups, with notable variations in several psychological and behavioral measures. The experimental group exhibited deviations in exhaustion, cynicism, both positive and negative affectivity, job satisfaction, sportsmanship, and altruism. The control group showed differences in negative affectivity, general well-being, and job satisfaction, while the comparison group presented irregularities in personal accomplishments, general well-being, negative affectivity, psychosomatic complaints, and job satisfaction. These deviations generally indicate stress-related constructs skewing right and personal or work-related resources skewing left. Additionally, significant group differences were observed in life satisfaction, with the experimental group reporting higher levels than the comparison group. Differences in conscientiousness and civic virtues between these groups were also significant.

Repeated-measures analysis of variance

In , we present the results of the repeated-measures ANOVA. Here, the two significant interaction effects are evident. The significant interaction effect of measurement time point and group for positive affectivity (F(2, 80) = 2.92, p = 0.026, η2 = 0.13) and conscientiousness (F(2, 80) = 2.79, p = 0.032, η2 = 0.12).

Table 1. Results of the repeated-measures ANOVA.

There is a significant main effect of measurement time on positive affectivity in the experimental group. Positive affectivity decreased significantly from measurement time one to three (Mdiff = −0.37, SE = 0.188, p = 0.011, 95% CI [-0.66, −0.07]) and from measurement time two to three (Mdiff = −0.35, SE = 0.188, p = 0.017, 95% CI [-0.64, −0.05]). Individuals in both the experimental and control groups experienced a decrease in positive affectivity during the study period. For conscientiousness, a significant main effect was found in the comparison groups. Conscientiousness increased significantly between measurement time one and measurement time two (Mdiff = 0.55, SE = 0.192, p = 0.021, 95% CI [0.07; 1.03]).

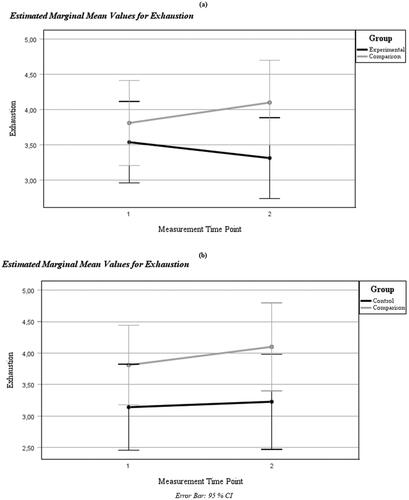

An explorative analysis revealed a slight decrease in exhaustion scores within the experimental group and the control group between measurement times one and two. In contrast, the exhaustion levels of the comparison group increased during the same period. To delve deeper into the change in exhaustion between measurement time points one and two, separate group comparisons were conducted using repeated-measures ANOVA.

These comparisons were carried out separately for the control and comparison group, and the experimental and comparison group. The analysis did not reveal a significant interaction effect for the control and comparison group, even when accounting for the covariate sex (F(1, 36) = 1.13, p = 0.295, η2 = 0.03) (). However, the analysis did uncover a significant interaction effect in the comparison of the experimental and the comparison group, when controlling for sex (F(1, 41) = 5.61, p = 0.023, η2 = 0.12) ().

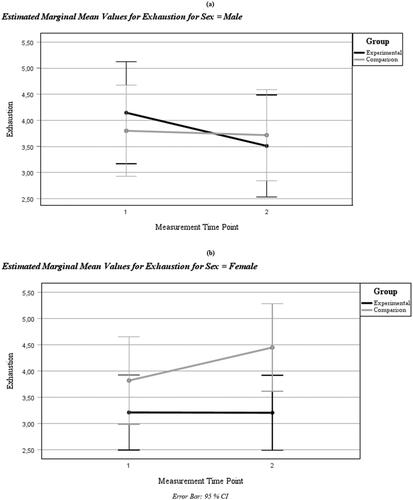

Figure 4. Marginal mean values of the dependent variable exhaustion in separate group comparisons over measurement time point one and two.

To explore this interaction effect in more depth, the control group was excluded from the dataset, and pairwise comparisons of marginal means were conducted with Bonferroni correction. This revealed no significant main effects for either the group comparison or the measurement time point. Only the interaction effect exhibited significance. For this reason, the covariate sex was further analyzed, and sex was included as a second group factor in the ANOVA analysis. The interaction effect of measurement time point, experimental group, and sex was not significant (F(1, 40) = 0.025, p = 0.876, η2 = 0.01). However, there was a significant interaction effect of sex and measurement time point (F(1, 40) = 6.61, p = 0.014, η2 = 0.14). Paired marginal means with Bonferroni correction were computed for this model as well. These analyses revealed a significant mean difference between measurement time points one and two in the experimental group for males (Mdiff = −0.636, SE = 0.300, p = 0.039, 95% CI [-1.24; −0.03]), indicating that males in the experimental group significantly reduced their exhaustion compared to males in the comparison group (). For females, the changes between measurement time one and measurement time two were not significant in the experimental group (Mdiff = −0.006 (SE = 0.218), p = 0.978, 95% CI [-0.45; 0.44]). In the comparison group, the mean difference for females indicated a significant increase in exhaustion (Mdiff = 0.629, SE = 0.256, p = 0.02, 95% CI [0.12; 1.14]) ().

To summarize, significant interactions were observed for positive affectivity and conscientiousness. In the participants of the experimental group, positive affectivity decreased significantly during the study period, especially from the first to the third measurement. Conversely, participants in the comparison group increased their conscientiousness. In addition, a notable interaction effect was found for fatigue between the experimental and comparison groups, with a focus on gender as a covariate. Specifically, male participants in the experimental group significantly reduced their fatigue compared to participants in the comparison group. In contrast, women in the comparison group reported increased levels of fatigue, particularly between the first two measurements. Consequently, the results partially support hypothesis one, while hypotheses two and three were not confirmed.

Discussion

Our study aimed to explore the effects of expressive writing, a structured emotional disclosure intervention, on work stress as well as work-related attitudes and behaviors. Lukenda et al.'s (Citation2023) research highlights expressive writing’s positive outcomes in organizational settings. They emphasize the need for more longitudinal studies to assess its long-term impact and explore effects on work motivations, attitudes, and behaviors. To address these research gaps, our study used a 3 × 3 mixed design with N = 62 German participants, assessing them at pre-intervention, post-intervention, and four weeks post-intervention. The experimental group engaged in expressive writing, the control group completed a time management task, and the comparison group received no treatment. We measured 18 dependent variables and tested three main hypotheses, assuming a positive influence of expressive writing on work stress (hypothesis 1), work engagement (hypothesis 2), and organizational outcomes (hypothesis 3). In summary, we found a significant reduction in exhaustion levels for males in the experimental group, while females in the comparison group experienced significantly increased exhaustion. These effects became evident only when the control group was excluded from the analysis. Furthermore, an unexpected effect in the experimental group was found, characterized by a significant reduction in positive affectivity between measurement times two and three. Building on these results, we found partial evidence for hypothesis 1 and were not able to accept hypotheses 2 and 3.

When interpreting the decrease in exhaustion for males within the context of the research model, expressive writing primarily impacts the health-impairment pathway. Our initial hypothesis suggested that expressive writing would lessen the overstraining interpretation of the demand, enhance resources, and therefore result in reduced work stress, increased motivation, and positive organizational outcomes. No significant increase in motivation and organizational outcomes was found, leading to the non-acceptance of these hypotheses. Consequently, the intervention has a limited impact on the motivation pathway, with the primary manifestation occurring through the health-impairment pathway (Bakker & Demerouti, Citation2017). The explanation for this manifestation could be derived from the transactional stress model (Lazarus & Folkman, Citation1987), as it assumes that the experience of stress depends on the subjective appraisal of the motivational significance of the demand (primary appraisal) and the resources an individual has to meet the demand (secondary appraisal). Based on this, expressive writing does not directly influence the demands or resources themselves. Instead, it facilitates the otherwise implicit and automatic primary appraisal process to occur explicitly and in a controlled manner. This conscious engagement with a potentially threatening demand can lead to a less intense stress reaction, thus reducing work stress.

This interpretation aligns with the emotional processing hypothesis of the expressive writing paradigm and could account for the observed sex differences as well. The emotional processing hypothesis posits that expressive writing allows individuals to consciously engage with themself and reflect upon unprocessed cognitions and emotions regarding the stressor, which in turn initiates a habituation process. This habituation process leads to a less intense experience of the stress response due to increased tolerance to stressors (Robertson et al. Citation2021).

Concerning the observed sex differences, this assumption could be applied as follows: For instance, Procaccia et al. (Citation2021) found significant improvements in psychopathological symptoms among males when they engaged in expressive writing and explained their findings based on a hypothesis made by Range & Jenkins (Citation2010). According to Range & Jenkins (Citation2010), males generally have a lower tendency to verbally express emotions and thus benefit more when specifically prompted to do so. Females, on the other hand, who are more likely to verbalize emotions in their daily lives, may not experience the same effect. This assumption implies that females are more habituated to verbally engage with threatening demands, leading to a less pronounced effect of emotional processing within expressive writing. In contrast, men benefit from this verbal habituation to a greater extent, as they typically engage less verbally with threatening demands.

However, this interpretation should not be accepted without critical examination, as other studies have identified positive effects of expressive writing on job attitudes. For instance, Round et al. (Citation2022) observed a positive influence on work satisfaction, and Cosentino et al. (Citation2021) found a positive impact of expressive writing on continuance commitment. Moreover, direct effects of the intervention on personal resources, such as self-efficacy (Kirk et al., Citation2011) and resilience (Saldanha & Barclay, Citation2021), have been demonstrated. It is also important to consider that the absence of significant effects in the present study may be attributed to methodological factors or the characteristics of the study sample, which will be discussed in the last section of this article.

Unexpected findings

Positive affectivity decreased significantly in the experimental group between the post-test and follow-up measurements. Initially, we expected that expressive writing would positively impact positive affectivity, as low positive affectivity was considered an indicator of work stress. Surprisingly, our results demonstrated the opposite effect. This outcome can be understood by considering findings on affective response patterns following expressive writing sessions, as reported by Pascual-Leone et al. (Citation2016). They observed an increase in positive affect in the experimental group but also noted an initial increase in negative affect after the writing session. This zig-zag pattern of affective response may contribute to the decline in positive affectivity in our study. Positive affectivity could have improved again by the third measurement time point, but our data does not show this, possibly due to the limited number of measurement points in our study compared to the six in Pascual-Leone et al. (Citation2016). The question of whether improvements in affectivity would return with a longer assessment duration remains to be addressed in future studies.

Conscientiousness increased significantly in the comparison group between the first and second measurement time points. The increase in conscientiousness in the comparison group, which underwent no treatment, can likely be attributed to the drop-out of less conscientious participants.

Limitations, future research, and implications

While our study provides valuable insights into the relationship between expressive writing and work stress, it has certain limitations that should be considered. The field experimental design is susceptible to external confounding factors, such as the timing of data collection coinciding with the Christmas season, introducing potential seasonal variations in stress levels. The sample, consisting mainly of in-service students, and the study period overlapping with the end of the semester may have influenced work stress due to academic commitments. Additionally, shortening two scales (psychosomatic complaints and affective commitment) could impact the validity of the measurements. Another limitation arises from our participant selection process. Despite aiming to investigate the influence of expressive writing on work stress, the experimental group exhibited lower work stress levels and higher resources than a typical distribution, potentially confounding the observed effects.

The selection of dependent variables could also be reconsidered. We focused on specific paths within the research model and primarily assessed the effects of resources, such as increased work engagement, rather than directly measuring resources themselves.

The recruitment strategy and execution of the design entailed enhanced email communication with participants to schedule Zoom sessions. This increased interaction with the experimenter potentially affecting implementation objectivity.

Future research could directly collect demands and resources. Our choice of organizational outcomes may only partially capture the effects of expressive writing on work stress, as they primarily target the motivational pathway. The measurement period may also have been too brief to detect significant changes in organizational outcomes, considering their distal nature. Future research should anticipate potential disruptions and prescreen participants for baseline stress levels to address these limitations. Subsequent investigations should explore how expressive writing affects the evaluation of demands and resources by collecting them as dependent variables and revising organizational outcome measures, including more measures that capture in-role work behavior (e.g., withdrawal) instead of extra-role behavior.

Despite the study’s limitations, the significant association between expressive writing and a dimension of burnout is a noteworthy discovery, considering that prior research in this area could not find a significant effect (Round et al., Citation2022) or had only a quasi-experimental research design (Tonarelli et al., Citation2018). Therefore, our study is one of the first robust experimental investigations to establish a positive significant effect of expressive writing on burnout. Burnout incurs substantial costs for companies (Han et al., Citation2019) and places a heavy burden on individuals. Therefore, expressive writing could offer a simple and cost-effective approach to alleviate suffering and mitigate the material expenses of demanding work environments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Allen, N. J., & Meyer, J. P. (1990). Organizational socialization tactics: A longitudi-nal analysis of links to newcomers’ commitment and role orientation. Academy of Manage-Ment Journal, 33(4), 847–858.

- Alparone, F. R., Pagliaro, S., & Rizzo, I. (2015). The words to tell their own pain: Linguistic markers of cognitive reappraisal in mediating benefits of expressive writing. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 34(6), 495–507. doi:10.1521/jscp.2015.34.6.495

- Ashley, L., O’Connor, D. H., & Jones, F. (2013). A randomized trial of written emo-tional disclosure interventions in school teachers: Controlling for positive expectancies and effects on health and work satisfaction. Psychology Health & Medicine, 18(5), 588–600. doi:10.1080/13548506.2012.756536

- Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2017). Job demands–resources theory: Taking stock and looking forward. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 22(3), 273–285. doi:10.1037/ocp0000056

- Bourassa, K. J., Allen, J. F., Mehl, M. R., & Sbarra, D. A. (2017). Impact of narrative expressive writing on heart rate, heart rate variability, and blood pressure after marital separation. Psychosomatic Medicine, 79(6), 697–705. doi:10.1097/psy.0000000000000475

- Büssing, A., & Perrar, K.-M. (1992). Die messung von burnout. Untersuchung einer deutschen fassung des maslach burnout inventory (MBI-D) [Measuring burnout: A study of a German version of the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI-D)]. Diagnostica, 38(4), 328–353.

- Caputo, A., Monterosso, D., & Sorrentino, E. (2022). Writing about stressful work-place experiences: A systematic review with meta-analysis of the effectiveness of written emotional disclosure (WED) interventions in working adults. Psychology Hub, 39(2), 31–44.

- Cosentino, C., Baccarini, E., Melotto, M., Meglioraldi, R., D'Antimi, S., Semeraro, V., Cervantes Camacho, V., & Artioli, G. (2021). The effects of Expressing Writing on Palliative Care healthcare professionals: A qualitative study. Acta Bio-Medica: Atenei Parmensis, 92(S2), e2021335. doi:10.23750/abm.v92is2.12650

- Currall, S. C., & Organ, D. W. (1988). Organizational citizenship behavior: The good soldier syndrome. Administrative Science Quarterly, 33(2), 331. doi:10.2307/2393071

- De Wijn, A., & Van Der Doef, M. (2022). A meta-analysis on the effectiveness of stress management interventions for nurses: Capturing 14 years of research. International Journal of Stress Management, 29(2), 113–129. doi:10.1037/str0000169

- Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., Nachreiner, F., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2001). The job demands-resources model of burnout. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(3), 499–512. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.86.3.499

- Gerhardt, C., Bibe, a A., Burmann, K., Gundlach, J., & Fiedler, S. (2011). Freiwilliges Arbeitsengagement: Idealismus oder Eigennutz? Journal of Business and Media Psychology, 1, 43–51.

- Glaesmer, H., Grande, G., Braehler, E., & Roth, M. (2011). The German version of the satisfaction with life scale (SWLS). European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 27(2), 127–132. doi:10.1027/1015-5759/a000058

- Han, S., Shanafelt, T. D., Sinsky, C. A., Awad, K., Dyrbye, L. N., Fiscus, L. C., Trockel, M., & Goh, J. (2019). Estimating the attributable cost of physician burnout in the United States. Annals of Internal Medicine, 170(11), 784–790. doi:10.7326/M18-1422

- Holman, D., Johnson, S., & O'Connor, E. (2018). Stress management interventions: Improving subjective psychological well-being in the workplace. Handbook of Well-being, 1–13.

- IBM Corp. (2022). IBM SPSS statistics for windows (Version 27).

- Janke, S., & Glöckner-Rist, A. (2013). Deutsche version der positive and negative affect schedule (PANAS). Zusammenstellung Sozialwissenschaftlicher Items Und Skalen (ZIS).

- Kirk, B. A., Schutte, N. S., & Hine, D. W. (2011). The effect of an expressive-writing intervention for employees on emotional self-efficacy, emotional intelligence, affect, and workplace incivility. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 41(1), 179–195. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.2010.00708.x

- Kleka, P., & Soroko, E. (2018). How to avoid the sins of questionnaires abridgement. Survey Research Methods, 12(2), 147–160.

- Krohne, H. W., Egloff, B., Kohlmann, C., Tausch, A. (1996). Positive and negative affect schedule–German version [Dataset]. In PsycTESTS Dataset. doi:10.1037/t49650-000

- Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1987). Transactional theory and research on emotions and coping. European Journal of Personality, 1(3), 141–169. doi:10.1002/per.2410010304

- Lukenda, K., Sülzenbrück, S., & Sutter, C. (2023). Expressive writing as a practice against work stress: A literature review. Journal of Workplace Behavioral Health, 39(1), 1–32. doi:10.1080/15555240.2023.2240512

- Madsen, I. E. H., Nyberg, S. T., Magnusson Hanson, L. L., Ferrie, J. E., Ahola, K., Alfredsson, L., Batty, G. D., Bjorner, J. B., Borritz, M., Burr, H., Chastang, J.-F., de Graaf, R., Dragano, N., Hamer, M., Jokela, M., Knutsson, A., Koskenvuo, M., Koskinen, A., Leineweber, C., … Kivimäki, M, IPD-Work Consortium. (2017). Job strain as a risk factor for clinical depression: Systematic review and meta-analysis with additional individual participant data. Psychological Medicine, 47(8), 1342–1356. doi:10.1017/s003329171600355x

- Maier, G. W., & Woschée, R.-M. (2002). Die affektive Bindung an das Unternehmen: Psychometrische Überprüfung einer deutschprachigen Fassung des Organizational Commitment Questionnaire (OCQ) von Porter und Smith (1970). Zeitschrift Für Arbeits- Und Organisationspsychologie, 46(3), 126–136.

- Mazzola, J. B., & Disselhorst, R. (2019). Should we be “challenging” employees? A critical review and meta‐analysis of the challenge‐hindrance model of stress. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 40(8), 949–961. doi:10.1002/job.2412

- Michailidis, E., & Cropley, M. (2019). Testing the benefits of expressive writing for workplace embitterment: A randomized control trial. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 28(3), 315–328. doi:10.1080/1359432X.2019.1580694

- Mohr, G., & Müller, A. (2004). Psychosomatic complaints in a non-clinical context. Compilation of Social Science Items and Scales (ZIS). doi:10.6102/zis78

- Morrissette, A. M., & Kisamore, J. L. (2020). A meta-analysis of the relationship between role stress and organizational commitment: The moderating effects of occupational type and culture. Occupational Health Science, 4(1-2), 23–42. doi:10.1007/s41542-020-00062-5

- Pascual-Leone, A., Yeryomenko, N., Morrison, O. P., Arnold, R., & Kramer, U. (2016). Does feeling bad, lead to feeling good? Arousal patterns during expressive writing. Review of General Psychology, 20(3), 336–347. doi:10.1037/gpr0000083

- Pavlacic, J. M., Buchanan, E. M., Maxwell, N., Hopke, T. G., & Schulenberg, S. E. (2019). A meta-analysis of expressive writing on posttraumatic stress, posttraumatic growth, and quality of life. Review of General Psychology, 23(2), 230–250. doi:10.1177/1089268019831645

- Pennebaker, J. W. (1997). Writing about emotional experiences as a therapeutic process. Psychological Science, 8(3), 162–166. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.1997.tb00403.x

- Pennebaker, J. W., & Beall, S. C. (1986). Confronting a traumatic event: Toward an understanding of inhibition and disease. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 95(3), 274–281. doi:10.1037/0021-843x.95.3.274

- Podsakoff, N. P., LePine, J. A., & LePine, M. A. (2007). Differential challenge stress-or-hindrance stressor relationships with job attitudes, turnover intentions, turnover, and with-drawal behavior: A meta-analysis. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(2), 438–454. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.92.2.438

- Procaccia, R., Segre, G., Tamanza, G., & Manzoni, G. M. (2021). Benefits of expressive writing on healthcare workers’ psychological adjustment during the COVID-19 pandemic. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 624176. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.624176

- Range, L. M., & Jenkins, S. R. (2010). Who benefits from Pennebaker’s expressive writing paradigm? Research recommendations from three gender theories. Sex Roles, 63(3-4), 149–164. doi:10.1007/s11199-010-9749-7

- Reinhold, M., Bürkner, P., & Holling, H. (2018). Effects of expressive writing on depressive symptoms - A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 25(1), e12224. doi:10.1111/cpsp.12224

- Richter, G. (2000). Psychische Belastung und Beanspruchung. Wirt-schaftsverlag NW.

- Robertson, S. M., Short, S. D., Sawyer, L., & Sweazy, S. (2021). Randomized controlled trial assessing the efficacy of expressive writing in reducing anxiety in first-year college students: The role of linguistic features. Psychology & Health, 36(9), 1041–1065. doi:10.1080/08870446.2020.1827146

- Round, E., Wetherell, M., Elsey, V., & Smith, M. S. (2022). Positive expressive writing as a tool for alleviating burnout and enhancing wellbeing in teachers and other full-time workers. Cogent Psychology, 9(1), 1–13. doi:10.1080/23311908.2022.2060628

- Saks, A. M. (2019). Antecedents and consequences of employee engagement revisited. Journal of Organizational Effectiveness: People and Performance, 6(1), 19–38. doi:10.1108/JOEPP-06-2018-0034

- Saldanha, M. F., & Barclay, L. J. (2021). Finding meaning in unfair experiences: Using expressive writing to foster resilience and positive outcomes. Applied Psychology. Health and Well-Being, 13(4), 887–905. doi:10.1111/aphw.12277

- Schaufeli, W. B., Bakker, A. B., & Salanova, M. (2003). Utrecht work engagement scale-9. Educational and Psychological Measurement.

- Schaufeli, W. B., Salanova, M., González-Romá, V., & Bakker, A. B. (2002). The measurement of engagement and burnout: A two sample confirmatory factor analytic approach. Journal of Happiness Studies, 3(1), 71–92. doi:10.1023/A:1015630930326

- Schmidt, S., Mühlan, H., & Power, M. (2005). The EUROHIS-QOL 8-item index: Psychometric results of a cross-cultural field study. European Journal of Public Health, 16(4), 420–428. doi:10.1093/eurpub/cki155

- Siltaloppi, M., Kinnunen, U., & Feldt, T. (2009). Recovery experiences as moderators between psychosocial work characteristics and occupational well-being. Work & Stress, 23(4), 330–348. doi:10.1080/02678370903415572

- Sloan, D. M., & Marx, B. P. (2018). Maximizing outcomes associated with expressive writing. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 25(1), e12231. doi:10.1111/cpsp.12231

- Sloan, D. M., Marx, B. P., & Epstein, E. M. (2005). Further examination of the exposure model underlying the efficacy of written emotional disclosure. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73(3), 549–554. doi:10.1037/0022-006x.73.3.549

- Staufenbiel, T., & Hartz, C. (2000). Organizational citizenship behavior: Entwicklung und erste Validierung eines Meßinstruments. Diagnostica, 46(2), 73–83. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2000-03885-002 doi:10.1026/0012-1924.46.2.73

- Tonarelli, A., Cosentino, C., Tomasoni, C., Nelli, L., Damiani, I., Goisis, S., Sarli, L., & Artioli, G. (2018). Expressive writing. A tool to help health workers of palliative care. Acta Bio-Medica: Atenei Parmensis, 89(6-S), 35–42. doi:10.23750/abm.v89i6-s.7452

- Wanous, J. P., Reichers, A. E., & Hudy, M. J. (1997). Overall work satisfaction: How good are single-item measures? Journal of Applied Psychology, 82(2), 247–252. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.82.2.247