Abstract

Conflict has displaced 1.5 million Syrians to Lebanon and within this context, child marriage has reportedly increased. We present a thematic intersectionality analysis of focus group discussions examining specific intersections and how they influence marriage practices: (1) immigration status and safety; (2) immigration status and economic instability; as well as (3) safety and instability, with gender as a cross-cutting theme. We aim to understand how forced displacement intersects with other, more widely recognized vulnerabilities, such as poverty, insecurity and gender, thus contributing to increased rates of child marriage with the aim of informing holistic strategies to address harmful marriage practices.

Introduction

As a result of armed conflict in Syria since 2011, Lebanon is currently hosting 1.5 million displaced Syrians including 997,905 million registered as refugees with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) (UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, 2017). Approximately 70% of Syrian refugees in Lebanon are recognized as being poor by World Bank standards (The World Bank, Citation2015), and with increasing debt and a growing reliance on food aid, many Syrian families live in precarious circumstances. For instance, in the absence of formal camps, many live in makeshift structures within informal tented settlements in the Beqaa region or in overcrowded rented spaces in urban centers (Global Communities - Partners for Good, Citation2013). Being the highest per capita host of refugees in the world (Adaku et al., Citation2016) places considerable strain on Lebanon’s already fragile economy and public service infrastructure (Cherri et al., Citation2016). Tensions have developed between Syrian migrants and the host Lebanese community resulting, in part, from competing demands for basic goods, services, and livelihood opportunities. As competition for basic necessities and economic stability has escalated, frustration, scapegoating and discrimination have been reported by Syrian migrants in Lebanon (Guay, Citation2016).

Lebanon is hosting more than 500,000 displaced Syrian children (Human Rights Watch, 2016), some of whom have experienced physical injuries, psychological stress, food insecurity, and lack of basic health services (Bartels et al., Citation2018; Child Protection Working Group, Citation2013; UNICEF, Citation2016a; World Vision International, 2012). Furthermore, many Syrian children cannot access formal education and have had to enter the workforce to help support their families financially (Abu Shama, Citation2013; UNICEF, Citation2016a, Citation2014a). Additional gendered risks have been documented for displaced Syrian girls including harassment and gender-based violence (GBV), and recent reports have raised concern over increased rates of child marriage within the Syrian crisis (International Rescue Committee, Citation2015; Save the Children Fund, Citation2014; Spencer & Care International, Citation2015; UN Women, Citation2013; UNICEF, Citation2014a, Citation2014b; United Nations Population Fund, n.d.). Although child marriage occurred in pre-war Syria, forced displacement appears to have increased its prevalence (UNICEF, Citation2014b), and in 2017 approximately 35% of Syrian refugee girls/women in Lebanon were reportedly married before the age of 18 (in comparison to 13% of girls marrying in Syria before the age of 18 in 2006) (UNICEF, Citation2016b).

UNICEF defines child marriage as any formal or informal union where one or both parties is below the age of 18 (Sexual Rights Initiative, Citation2013). Early marriage additionally includes cases where the spouse may have attained the age of majority according to national laws (and therefore is not considered a child), or is over the age of 18 but is not physically, emotionally, sexually or psychosocially ready to consent to marriage. Forced marriage, that in which one or both of the spouses did not give their free and full consent, relates to Article 16(2) of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (United Nations, n.d.) and to the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (UN Women, n.d.). The authors recognize important distinctions between child, early and forced marriage and the current work is intentionally focused on child marriage, which is widely recognized as a human rights violation according to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (United Nations, n.d.), the Convention on the Rights of the Child (UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, Citation1989), the Convention on Consent to Marriage, Minimum Age for Marriage and Registration of Marriages (UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, n.d.) and the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (UN Women, n.d.).

Child marriage is a global issue, with gender inequalities and poverty continuing to be major underlying contributors, and with many parents believing that it is the best way to secure their daughters’ futures (Amnesty International Canada, 2013; Ganchimeg et al., Citation2014). During periods of armed conflict and forced displacement, rates of child marriage are reportedly increased as the heightened risk of sexual violence and harassment lead some families to feel that marriage and a good husband will offer girls necessary protection (Abu Shama, Citation2013; Raj, Citation2010; United Nations Population Fund, n.d.). This may be additionally associated with the notion that girls who have experienced sexual violence are considered unsuitable for marriage and bring dishonour to their families. In these settings, some parents arrange child marriages in an attempt to reduce or eliminate such risks. Furthermore, armed conflict and forced displacement are often associated with loss of employment and economic opportunities resulting in financial hardship for many families. In these settings, some parents decide to marry their daughters prematurely as a way to ensure that the girls are provided for and that their basic needs are being met.

There is a growing body of evidence on the consequences of child marriage including sexual and reproductive health risks such as complicated pregnancies and deliveries (International Rescue Committee, Citation2015; Nguyen & Wodon, Citation2014; Nour, Citation2006; Nove et al., Citation2014; Save the Children Fund, Citation2014), higher risk for neonatal death and stillbirth (Human Rights Watch, 2016; UNFPA, Citation2017; UNICEF, Citation2016a, Citation2014a), and higher risk of sexually transmitted infections, HIV/AIDS and cervical cancer (Chaaban & Cunningham, Citation2011). Furthermore, girls who marry early are often at higher risk of intimate partner violence (Human Rights Watch, 2016; UNICEF, Citation2016a, Citation2014a) and child marriage tends to reduce girls’ access to education, which limits their future literacy skills and earning potential (Chaaban & Cunningham, Citation2011; Nguyen & Wodon, Citation2014; Parsons et al., Citation2015).

Less evidence exists about the intersecting factors that contribute to child marriage in humanitarian settings and during forced displacement. Undoubtedly, gender inequalities and poverty continue to be important determinants but a more in-depth and nuanced understanding is needed of how forced displacement affects child marriage. To address this evidentiary gap, the current qualitative analysis investigated child marriage within the context of Syrian families’ forced migration to Lebanon. More specifically, our objective was to better understand how immigration policies and experiences as refugees intersect with other vulnerabilities, such as poverty and insecurity from the perspectives of displaced communities, to influence decisions around marriage practices for young girls. Since such vulnerabilities overlap in the everyday lives of Syrian families, we argue that an understanding of these intersections is important for informing strategic programming and policies to address child marriage in the future. Indeed, rather than seeing child marriage among displaced families as an extension of Syrian culture or patriarchy, we found that child marriage rates are impacted by structures of poverty, insecurity, migration and gender.

Methods

An interdisciplinary research team conducted a mixed methods survey in 2016 (Bakhache et al., Citation2017; Bartels et al., Citation2018) and focus group discussions (FGDs) in 2017 on the topic of child marriage amongst Syrian refugees in Lebanon. ABAAD is a Lebanese nonprofit, nonpolitically affiliated, non-religious civil association that promotes equality, protection and empowerment of women. It has a history of grassroots work with Syrian refugee communities and had a very good rapport with FGD participants. Importantly, ABAAD also has a history of research collaborations and had identified the need for qualitative investigation of Syrian communities’ perspectives of child marriage in Lebanon from its own work and findings of previous studies. Canadian research partners consisted of a physician and global public health researcher, an epidemiologist, and a socio-legal scholar. Throughout the course of the project, the research team met in person and online to develop and discuss the research tools and analysis. The team was aware of the ethical concerns and power dynamics of working with vulnerable and displaced communities (elaborated further below) and was cognizant of the power dynamics within the research team. Team members from ABAAD and Queen’s University were equal partners and as reflexive as possible throughout the project.

Tool development

The interdisciplinary team developed a semi-structured questionnaire in English and translated it to Arabic. The Arabic translation was then independently verified by a native speaker and was used for data collection. The question guide aimed to elicit feedback on the results of the prior mixed methods study (Bartels et al., Citation2018) and to gather additional insights into perceptions about child marriage among Syrian families displaced to Lebanon. The FGDs were also intended to solicit responses to strategies that might be used to reduce rates of child marriage and to mitigate potential harms. Informed by ABAAD’s prolonged work experience with the communities, no demographic information or other identifiers were collected from participants (girls, women and men) due to fear that doing so would raise security concerns within the community, especially among male participants. It is worth noting that at the time of data collection, many displaced Syrians were concerned about potential repercussions of being identified, since some may have fled from army duty and/or were at risk of being detained by the Syrian regime due to anti-government political engagements.

Qualitative data collection

In January 2017, the ABAAD Resource Center for Gender Equality in Lebanon, in collaboration with Queen’s University, hosted 10 focus group discussions (FGDs). The FGDs were implemented in follow up to the larger mixed methods study conducted in 2016 examining the societal, economic, security, religious, and psychosocial factors contributing to child marriage among Syrian refugees in Lebanon (Bakhache et al., Citation2017; Bartels et al., Citation2018). At least three FGDs were conducted in each of the geographic regions:

Beirut/Mount Lebanon, Tripoli and Beqaa; one with Syrian girls (aged 13–18), one with Syrian mothers, and one with Syrian fathers. Beqaa was an exception as there were two FGDs held with women over the age of 18. Potential participants were approached by an ABAAD field team member who was actively engaged in the community.

ABAAD field workers reached out to potential participants, who had previously participated in one or more of ABAAD’s community-based programs and were therefore recruited through the organization’s beneficiary network. All potential participants were informed that their participation was voluntary without any implications for access to services by ABAAD or other humanitarian service providers. Interested participants provided verbal consent to take part in the study and were informed about their right to stop participation at any point throughout the FGDs. Focus group participants had not necessarily been involved in the 2016 mixed methods study.

The nature of the research was explained at the beginning of each FGD using a standardized script and each FGD was facilitated in Arabic by a member of ABAAD who had expertise working with survivors as well as women and girls at risk of GBV. All discussions were in Arabic and were audio recorded with permission of the participants. Audio files were later transcribed and translated from Arabic to English for coding and analysis. The transcripts were reviewed by an Arabic speaker for accuracy and nuanced interpretation.

Qualitative data analysis

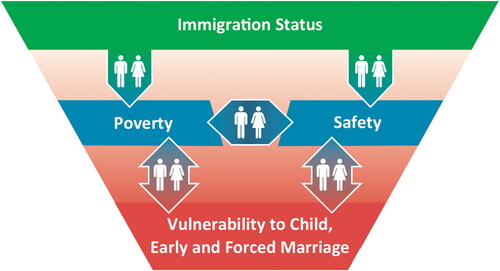

The purpose of this analysis was to better understand how marriage practices among young Syrians have been impacted by the forced migration resulting from the ongoing armed conflict in Syria. As such, an inductive thematic analysis of the transcripts was done according to Braun and Clarke incorporating a latent theme approach to examine the underlying ideologies that may have shaped the data (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006). Following familiarization with the data, codes were created in NVivo, and were then used to identify initial themes from the transcripts (SB). All themes were reviewed, defined and named, and then used to create a conceptual model (SB, SM, AB) representing the results presented in . Triangulation and critical dialogue between the researchers were essential to the analysis and the team was intentional in identifying which data were more relevant to the current analytical framework. Four main themes were identified from the data using an inductive or bottom-up approach: 1. economic insecurity, 2. safety concerns, 3. gender and 4. immigration status.

Figure 1. Conceptual framework of contextual factors affecting marriage practices in settings of forced displacement illustrating three important intersections: (a) immigration status and safety, (b) immigration status and poverty, as well as (c) poverty and safety. Gender is presented as a cross-cutting theme that impacts the experiences at all levels.

Intersectionality was then used as a theoretical approach to explore how the identified four structures of social vulnerability interact and affect each other with regards to child marriage practices. The data was revisited when needed to identify intersections as per the inductively developed and used theoretical framework. Rather than a more traditional interpretation of intersectionality as a study of how social and political identities combine to exacerbate discrimination, as introduced by Crenshaw (Citation1989) and other scholars, the current analysis examines the intersections between various structural vulnerabilities to child marriage after displacement. More specifically, a categorical or inter-categorical approach within intersectionality as described by McCall (Citation2005) was taken in an effort to understand the nature of relationships between identified social vulnerabilities and how those relationships have changed/are changing as a function of being displaced from Syria to Lebanon.

It is worth highlighting that gender was employed as a cross-cutting variable within each of the three identified themes: economic insecurity, safety concerns, and immigration status, as opposed to a stand-alone identity as introduced by Crenshaw (Citation1989). This decision was made for three reasons. First, the earlier mixed-methods study (Bartels et al., Citation2018) demonstrated significant quantitative gendered differences in how child marriage was perceived, thus underscoring the need to further investigate gender qualitatively and with an intersectional approach. Second, since first-person perspectives of men are often missing in studies of child marriage (in particular, the perspectives of young men and fathers), we believed including the male FGD represented a unique opportunity to fill a contextual gap in understanding child marriage among displaced communities. Following Henry, this inclusion of men’s perspectives in our intersectional analysis does not shift the analysis away from “male privilege and power” (Henry, Citation2017). Finally, a robust gendered understanding of the factors impacting child marriage is vital since men are often the main decision-makers in the household (Mourtada et al., Citation2017).

Ethical review

The research protocol was approved by the Queen’s University Health Sciences and Affiliated Teaching Hospitals Research Ethics Board (#6020027). Individuals over the age of 13 were eligible to participate and focus group members were recruited from within community programs offered by the ABAAD Resource Center for Gender Equality in each of the three locations. All participants gave verbal informed consent prior to the start of the FGDs. As per Rima Hibab’s work, we recognize that informed consent is challenging when conducting research with refugee populations living in precarious environments given that restricted autonomy and other circumstances may inadvertently lead to coercive conditions (Habib, Citation2019). However, the research team tried to be sensitive to this reality during study implementation. For instance, the recruitment process was done by ABAAD field teams and refrained from using community gatekeepers such as ‘Shaweesh’ to identify participants for the study, in order to minimize possibilities of coerced consent due to power imbalance between community members and gatekeepers. Participants were asked not to share names or other identifying information and were requested to not disclose details of the discussion with others. Transportation costs and light refreshments were provided to participants in the FGDs, but no monetary or other compensation was offered.

Results

Number of participants in each FGD by location are outlined in .

Table 1. Number of participants per focus group in each location.

As illustrated in , this thematic analysis identified three inter-related post-migration factors that contributed to child marriage among Syrian refugee families in Lebanon: (1) immigration status, (2) safety, and (3) economic insecurity. For the purpose of this analysis, “immigration status” refers to nationality, refugee status and legal residency. “Syrian refugee” refers to a self-identified Syrian national displaced to Lebanon as a result of armed conflict in Syria regardless of whether the individual was officially registered as a refugee with UNHCR. “Economic instability” was a term derived directly from the data and was taken to reflect the unpredictability and changes over time (mostly negative) in household income.

While safety and poverty have been well documented as individual contributors of child marriage particularly in humanitarian settings, this analysis contributes an examination of the intersection between immigration status and safety as well as the intersection between immigration status and economic insecurity. In doing so, we recognize the central role that immigration status plays in exacerbating perceived risks of safety and economic insecurity for adolescent refugee girls. Safety and economic insecurity are inter-related in a bi-directional manner and this intersection will also be explored. We view gender as a critical, cross-cutting fourth factor that permeates each of the above three intersections. Rather than examining gender as an independent factor, it will be integrated within each of the above analyses since each intersection is experienced differently by men/boys and women/girls as illustrated by the gendered symbols on the arrows in . FGD excerpts are presented to illustrate the gendered experiences at each of three intersections presented below.

Intersection 1: immigration status and safety

Safety and security concerns were raised prominently in all FGDs and in many cases the concerns were perceived to result from being a Syrian refugee in Lebanon. Many participants reported that they and their family members were singled out as targets for GBV, robbery, violence, etc., making them fear for their safety because they were Syrian. In other cases, it was the perceived discriminatory practices and policies within Lebanon that prevented Syrian refugees from being able to obtain the required legal documents that would allow them to pass police checkpoints and to have safe freedom of movement.

While security concerns were raised for all family members, safety for Syrian women and girls was a particular issue in discussions across all three locations. Again, there was a clear sense that women and girls were being specifically targeted because they were Syrian. As one man in Beirut shared, “They [Lebanese] insult Syrian girls and say bad words, and some even come in and take off their clothes.” Many of the participants felt that they had no mechanism or avenue for recourse since they were not legal residents in Lebanon. There was a sense that this vulnerability was recognized by members of the host community and that some Syrians were intentionally being taken advantage of because they were illegal immigrants in Lebanon. For example, another man in the Beirut focus group stated:

When a Syrian girl is walking in the streets, Lebanese guys see her as easy to get. ‘I can talk to her, I can harass her.’ This is because of the financial situation and no one to protect. She is an easy prey. While a Lebanese guy will not approach a Lebanese girl either because her mom works in the governmental sector, or her family is known, or they have money. A Syrian girl is not protected. If they call the police their papers are not valid.

If Syrian refugees were to go to the authorities to lodge a complaint, they would be first asked to show their up-to-date renewed documentation and, without these documents, they would be at risk of being imprisoned, fined or even deported. One woman in Beirut said, “They tell her, ‘if you don’t do this, I will report you to the police/security.’ They are not Syrians but Lebanese. If you don’t do as we say, you will not stay in this area.” In some cases, it was clear that male participants felt they were unable to protect their wives from being harassed as discussed by this man in Tripoli:

Women used to go out [in Syria], had their freedom, there was security. But now if a man is not with her, he will not feel secure if she goes out. Someone might verbally harass her. If I let my wife go out alone and a man harassed her verbally, I cannot do anything because I am Syrian.

Even in extreme cases involving sexual assault, many participants categorically felt that there was no protection for Syrians in Lebanon and there was a sense of resignation that such abuses had to be endured. Thus, in addition to fears of reporting to police that victims of GBV experience in most jurisdictions around the world, Syrian women and girls expressed the view that their precarious immigration status exacerbated their insecurity. As one woman in Tripoli shared:

You cannot go to security and complain unless you have valid papers. This is very important. If they hit you, harass you, rape you, you cannot go to security unless you have valid papers. You have to shut up. There is no security.

Female participants talked extensively about the risk of “harassment” faced by Syrian girls in their communities. Follow up inquiries by researchers into what was meant by harassment revealed that it could mean anything from verbal harassment by men on the street to sexual assault. When asked directly what parents need to protect their daughters from, one female participant in Beirut responded, “they want to protect them from rape mainly”. Recent evidence documents that Syrian women and girls face high levels of multiple forms of GBV in Lebanon (Michael et al., Citation2018); the perceived risks discussed by participants, therefore, were well founded.

There was a sense that having a daughter in Lebanon brought the additional responsibility of having to accompany her everywhere because it was unsafe for her to go out alone. This added responsibility in a setting that is already high pressure may further contribute to parents marrying their daughters early, particularly if the added responsibility of accompanying them distracts from the parents’ employment opportunities. There was some discussion among women’s and girls’ FGDs about girls wanting freedom, despite the well documented fears by men about safety and a suggestion that it was difficult at times to ensure that girls were at home where they would be safe. One mother in Beqaa commented as follows, “They are not protected, we don’t allow them to go outside alone. If you leave your daughter to do what she wants, you will lose her. Last night drunk people attacked the camp.”

Lebanon was perceived to be more ‘liberated’ and more ‘Western’, which led to concern that girls would be at higher risk of deviating from cultural values. This often led parents to restrict the mobility of girls as a means to prevent them from engaging in perceived risky behaviors thereby protecting them from harm. A woman in Beirut shared her perspective,

Early/child marriage is related to traditions and culture, girls would be scared to deviate [in Syria]. Here in Lebanon it is easier [to deviate], there is more freedom and socially more open. So, they [parents] choose to let their daughter marry so that she doesn’t deviate.

These security risks were perceived to be so high that in some cases, women and girls never left the home and it was only men who ventured out into the community. One male participant in Beqaa said, “Our girls are left at home, only men are leaving the house,” and a female participant in Beirut reported “My husband and kids used to work and my daughters and I stayed home 24 hours a day.” In the most extreme example, a male participant in Beirut admitted, “My wife, I haven’t taken her out for three years.”

As reported in other research (Abdulrahim et al., Citation2016; Bartels et al., Citation2018; Mourtada et al., Citation2017), restricted movement for Syrian girls limits their educational opportunities and sometimes contributes to parents feeling as though the best option is to marry their daughters since the girls are at home with little to occupy their time and with no or little hope to return to formal education. Restricted movement can be so severe that it leads to a sense of isolation and to some girls choosing to marry as a way out of unfavorable living conditions at their parent’s home. As one girl in Beirut bluntly stated:

First thing I want to talk about the girls who are protected too much, it’s like they imprison them. They don’t have the right freedom. They simply cannot go outside, have fresh air or see somebody or even to the veranda. It shouldn’t be like that. There is a difference between those that are protected enough and those that are overprotected.

In summary, at the intersection of safety and immigration status, some parents believed that their daughters were at higher risk to experience harassment and violence because they were Syrian and these perceived risks appear to be well founded based on recent research (Dionigi, Citation2016; Michael et al., Citation2018). This was often linked to host communities’ heightened perception of Syrian women and girls’ vulnerability, especially that they often lacked the means to report it. As such, to protect girls some Syrian parents resorted to marrying their daughters at a younger age.

Intersection 2: immigration status and economic insecurity

Economic insecurity was raised frequently in all FGDs and in many cases was perceived to be exacerbated by immigration status. Many participants reported that it was more difficult to work as a Syrian, more difficult to rent accommodations, etc. In other instances, perceived discriminatory practices and policies prevented Syrians in Lebanon from being able to obtain the necessary legal documents that would allow them to have safe freedom of movement, to work legally, to register their children in school, etc. and this further contributed to their poverty. Finally, Syrian men seemed to be specifically targeted for robbery because they would not be able to report theft to the police given that they did not have the renewed paperwork allowing them to be in Lebanon legally.

It was unanimous across subgroups of participants and across various focus group locations that economic insecurity was one of the greatest challenges facing Syrian families in Lebanon. Differences between life in Syria and life in Lebanon highlighted some of the causes of poverty as well as the demands that added to economic strain, including the role of the state services and access to employment and agriculture. For example, one woman in Beirut commented,

In Syria it was easier, a man working in agriculture was able to secure his family, not like here in Lebanon. In Syria everything was for free (school, university, heath). Increase in family members and being a refugee has had an impact.

It was evident how difficult it was to get ahead in Lebanon as a Syrian refugee because of restrictive employment policies that contribute to high unemployment rates, coupled with scarce opportunities to find work as a Syrian. For instance, one female participant in Tripoli stated, “Some [employers] put signs saying, ‘Syrians are not allowed to work.’”

In cases where Syrians reported access to the job market, participants reported that they were being exploited because they were paid less than their Lebanese coworkers. Again, there was little mechanism for recourse among individuals in desperate need of earning income but without valid documentation to lodge a complaint. There was considerable discussion around how income earned was often not enough to meet the family’s needs and the needs of girls specifically. The latter finding is significant in terms of child marriage since impoverished parents sometimes feel they are unable to provide for their daughters and therefore turn to child marriage as a way of securing their daughters’ economic futures. One woman in Tripoli reported,

Syrians are working but at lower wages because they accept what God gives them. They work a lot and at the end of the day they get 10000L.L.Footnote1 and girls have a lot of needs. But the Lebanese they don’t work a lot and they ask for money. They ask for specific time for specific salary and if they don’t accept, they have an alternative unlike Syrians.

There was some dialogue around girls choosing to marry as a way of meeting their own financial and material needs when they perceived that their families were unable to do so because of unemployment. One man in Tripoli stated,

When we came here things changed, girls don’t have a choice or they want to leave their homes if their fathers are not taking care of them financially. They say, “I want to get married so that my life is better because my father is not working and cannot afford buying me the things I want.”

In addition to receiving less salary, it was clear that in some cases, the costs of living were higher for Syrians, a burden exacerbated by receiving lower salaries. One woman in Tripoli recounted how a landlord admitted that he would rent to Syrian tenants at a rate of 1,00,000 L.L. more per month.

The interlinkages between poverty and immigration status were further highlighted around having the resources to update immigration paperwork in order to have the proper legal documents for freedom of movement in Lebanon. One man in Beirut noted that it cost him $1300 to renew his papers. Not having the proper paperwork prohibited many from being able to pass security checkpoints, which often limited participants’ ability to work. Since women faced additional security threats in their communities and in some cases may have been perceived as having lower earning potential, less priority was sometimes placed on renewing their documents and thus women were less likely to be employed.

The process of obtaining valid documentation was expensive with quoted prices ranging from $800 to $1300 USD per family. Most often it was because of economic insecurity that families were not able to validate their documents and as a result of not having valid documents they were not able to work, perpetuating the cycle of poverty. Participants spoke of being asked for a Lebanese sponsor, which was often not possible given tensions between the refugee and host communities (unless one was fortunate enough to have a close family member who was Lebanese).

With few employment opportunities, lower wages for Syrian employees, and discriminatory higher costs of living, many families rely on their children working to help meet the family’s financial needs. One female participant in Tripoli reported, “Most of the Syrian children are not in schools, they are working to support the family.” In some cases, a need for the children to work seemed to be related to parents not having the necessary funds to validate paperwork. By working, Syrian children were helping to meet their family’s basic needs such as food and shelter. As one woman in Beqaa confirmed,

Most men can’t work - they don’t have valid/legal papers so they can’t pass by police barriers. He can’t move from place to place. 10000L.L. per day what will it do? The children are forced to work so that we can pay the tent rental.

Economic strain and not having the finances to obtain the necessary documentation for school registration was discussed, particularly for Syrian girls. This finding is noteworthy since it has been well documented, both within the Syrian refugee crisis and elsewhere, that keeping girls in school is an important strategy for delaying marriage. One father in Beirut explained, “I had problems with [school] registration, their papers must be valid. We cannot put her in school. I just have the papers from the hospital and mayor.”

One focus group discussed how potential Lebanese suitors were often more interested in marrying Syrian women and girls because the bride dowry and wedding expenses were typically less and marriage was therefore more affordable. As for the perspective of Syrian families, it was reported that due to economic insecurity, parents were now accepting marriage offers that they might not have under different circumstances. The suggested stereotypical notion that Syrian brides were not as demanding as Lebanese brides possibly reflected the relative disempowerment of Syrian women and girls and a potential willingness to settle in less than ideal situations when opportunities for a better future were perceived to be limited. One man in Beirut said,

That’s why people are forced to let their children marry at a young age such as 13-14 because their financial situation is bad. She is a burden. I am against child marriage - how can a child raise a child? They both cry. We are against [chid marriage] but we are forced to do that because of financial situation. We as men, we are not providing the needs of our woman, even the basic needs such as food.

In summary, immigration status and economic insecurity intersect to create particular vulnerabilities for Syrian girls, with families often struggling to provide financially for their daughters’ food and shelter needs, let alone the ability to educate them. Since earlier research on child marriage established a clear link between the low socio-economic status of families and higher incidence of child marriage, our finding that displacement further intensifies this correlation is important. Under these circumstances some Syrian parents, like parents who face similar adversities in other parts of the world, often turn to child marriage as the perceived best option both for the family and for the girl herself.

Intersection 3: safety and economic insecurity

Safety and economic insecurity represent the third intersection contributing to child marriage among Syrian refugee families in this analysis. As discussed above for their respective intersections with immigration status, both safety and economic insecurity were prominent themes raised by participants in all FGDs across all three locations in Lebanon. In some cases, participants felt unsafe because financial constraints left them in situations that were perceived to increase their vulnerability (public transportation, housing, etc.). Furthermore, restrictive employment policies coupled with the lack of safety around passing police checkpoints and lack of freedom of movement meant that Syrian parents were unable to work to meet their families’ economic needs, leaving them in more economic strain than they would have been in had it been safe to go out to work.

One of the important safety/poverty intersections centered around accommodations with some participants noting that housing affordable to Syrian refugees was typically situated in unsafe and less desirable neighborhoods. Reference to living in less affluent communities arose in the context of discussing safety for Syrian girls. With parents feeling that there was little or no alternative to living in such accommodations, some parents may decide to marry their daughters as one way of improving her standard of living and her security. One man in Beirut explained,

As for protection and security, in the places that most Syrians come to which are relatively cheap, people there are misbehaving with low morale. We can’t live in a place where people are educated.

In other circumstances, participants reported that their use of public transportation (often due to not being able to pay for a private taxi), put them at risk of being targeted for harassment and this harassment, often around proving they possessed valid documents, was specifically targeted toward Syrians rather than other nationals. Here again a man in Beirut comments,

…there is discrimination against Syrians. When there is a Syrian in the van, they will stop the van because he is Syrian even though there are Egyptians and other nationalities. Based on our Syrian appearance, we are asked to show our papers. Others don’t have to do that.

In many cases, it was clear that participants believed it was unsafe for them to go out to work, even when there were employment opportunities available. Concerns about safety were often linked to not having valid legal documents in order to pass police and military checkpoints, which ultimately resulted from being a refugee and facing discriminatory policies for Syrians. A participant in Beqaa reported,

We are living on the border between Lebanon and Syria. We don’t have official papers. We couldn’t come to []. We have papers from the UN but the police tell us to go have it as a sandwich even if it proves that we are registered.

The repercussions around not having proper documentation included fines, deportation and imprisonment. All three of these penalties would significantly impact the family’s financial resources. One man in the Beqaa focus group shared that he “was arrested twice and in jail for two years function”. Realizing that lack of proper documentation made it difficult or impossible to work, some families were borrowing money or taking out loans in an effort to be able to work. Although helpful in the short-term, with high employment rates and later having to pay interest, this practice could put some families into more long-term debt.

Another intersection between safety and economic insecurity focused on how inaccessible education was as a result of economic strain and because it was perceived that girls were at risk of being harassed either at school or during the commute to/from school. In some cases, parents seemed resigned to the fact that their daughters would not be educated and under those circumstances marriage often offered the additional advantages of decreasing financial strain on the family while also protecting her honor, ensuring her safety and providing her with a perceived better future. A male participant in Beqaa had the following to say,

In Syria a girl could become a teacher or doctor - she had ambitions. When we came to Lebanon everything changed; the financial situation is hard…. Financial situation affects everything. A girl doesn’t like to marry at a young age, but now what can we do? We need someone to protect her honor. If she is at her husband’s house, he will take responsibility, a little of the burden will decrease.

There was discussion in one of the men’s FGDs about the degree to which girls were forced to marry in Lebanon. One man indicated that if a prospective groom proposed to his daughter, then it would be up to her to decide whether she wanted to marry him. Most other men in the room disagreed with this perspective indicating that the covert manner in which girls were enticed into marriage was, in essence, a way to force her. For instance, one man in Beirut shared the following,

He is talking about himself - people like him are only 1%. Many [parents] force young people to marry, the girl is immature so they tell her this guy will marry you, take you out, bring you stuff. This way, you force the girl but by persuading her.

A final intersection between safety and economic insecurity was the cycle of poverty which affects Syrian girls in the short and long-terms because they are not able to continue their formal education as a result of safety and financial concerns. Without formal education or skills/literacy training, girls will likely experience increased economic insecurity, their children will be less likely to be educated and are more likely to live in poverty, etc. affecting the next generation as well as this one. This cycle was appreciated by some participants. One man in Beqaa reflected on how life changed when his family moved to Lebanon,

When we came to Lebanon everything changed. The financial situation is hard and the family situation affects the financial situation. The financial situation affects education, education then affects the family. The financial situation affects everything.

In sum, participants were more impoverished because of insecurity and they were more unsafe because they were poor. With both economic need and safety known to be important independent factors that contribute to child marriage, it is critical to understand how the intersection of the two further increases girls’ vulnerability, particularly in settings of armed conflict and forced migration. Even at a young age, Syrian girls themselves recognized the importance of these two factors in marriage practices. As one girl in Beirut shared,

Some people force their children to get married early. They are scared for them - that something else will happen to them. It depends on the parents as well. Some parents are bribed by money to take the girl or the parents sell their daughters.

Implications for policy interventions

The current analysis of ten FGDs with a total of 99 Syrian girls, women and men in Lebanon highlighted the integral role of immigration in mediating economic insecurity and safety as risk factors for child marriage. Both economic insecurity and safety were exacerbated as a result of not having legal residency or refugee status in Lebanon. The converse was also true – economic insecurity and safety concerns made it more difficult to obtain legal residency in Lebanon. The experiences at each of the three examined intersections were gendered such that they were experienced differently by males and females, and all seemed to contribute to decisions to marry girls at a younger age. While immigration status, economic insecurity and safety may have other negative impacts on men and boys (such as vulnerability to violence, perceptions of marriage practices, etc.), the current discussions were primarily framed around women and girls. Despite this, the results suggest that men’s safety and financial stability are impacted by their immigration status. Further research is required to deepen our understanding of men and boys’ experiences in settings of forced displacement and how these experiences may or may not be impacted by their immigration status.

In 2015, the Lebanese government implemented new measures to dissuade Syrian refugees from seeking asylum in Lebanon. The new policy made it more challenging and more expensive to renew permissions to stay in Lebanon while simultaneously requiring all Syrians to have official documents indicating their place of residence (Dionigi, Citation2016). As a result of these new, seemingly discriminatory measures (Janmyr, Citation2016), in 2018 an estimated 74% of Syrians in Lebanon lacked legal status and were at risk of detention for unlawful presence in the country (Human Rights Watch, Citation2018). Human Rights Watch has raised concern about how Lebanon’s residency policy makes it difficult for Syrians to maintain legal status, heightening risks of exploitation and abuse and restricting refugees’ access to work, education, and healthcare (Human Rights Watch, Citation2018). Lack of legal refugee or residency status denies displaced individuals their basic rights and limits their ability to access services and justice in Lebanon (Dionigi, Citation2016). At the heart of the issue is the fact that Lebanon has not signed the 1951 Refugee Convention. Furthermore, Lebanon does not have any formal domestic refugee legislation (Janmyr, Citation2017). As a result of these policy decisions, refugees in Lebanon are provided with no status other than ‘foreign nationals’, forcing them to live in the country illegally, and often under harsh and marginalizing conditions (Janmyr, Citation2017). Thus, Lebanon is not obligated to provide asylum to refugees and it is not required to grant access to courts, elementary school education or travel documents. Furthermore, having not ratified the Refugee Convention, refugees in Lebanon are not entitled to the same public services and labor market as Lebanese citizens.

The current analysis did not provide any insights into whether having a valid UNHCR card mitigated the negative impact of immigration status on safety and/or economic insecurity. In fact, discussion around registration as a refugee was notably absent from the FGDs despite UNHCR having registered almost one million Syrian refugees between 2011 and 2015. Instead, focus among the current participants was very much on obtaining legal residency or renewing permits to stay in Lebanon. Future research should explore to what degree having UNHCR refugee status protects from the negative impacts of economic insecurity and safety with regards to child marriage.

In considering child marriage among forcibly displaced populations, the current results suggest that policies around legal residency must be included in a more comprehensive approach. Although we recommend that Lebanon ratify the 1951 Refugee Convention, this remains unlikely in the midst of the current refugee crisis and given that the Government of Lebanon has not ratified it despite considerable international pressure over the years. In the absence of ratification of the Refugee Convention, continued pressure on Lebanon from UNHCR, UNICEF, local human rights agencies, and others to provide a protective space to refugees is needed, and the crisis should be approached from a humanitarian perspective rather than a political one. It is particularly urgent to highlight how immigration policies impact the health and rights of children, especially the health and rights of girls and young women who are forced to marry prematurely. Additionally, policy review efforts for the legal age of marriage in Lebanon, should be coupled with community-based services aimed at increasing protection mechanisms, reducing economic insecurity and providing access to education. As suggested by Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs (Maslow, Citation1943), families and communities need to have their basic survival needs met (food, shelter, etc.) and they need to feel safe, in order to avoid negative coping strategies such as child marriage. More specific to the context, as argued by Yasmine and Moughalian (Citation2016), a structural approach to addressing GBV, including child marriage, is needed in humanitarian settings, with intervention efforts aiming to address the structural barriers such as poverty and discrimination rather than inaptly depoliticizing social struggles to intrapersonal shortfalls of individual girls and their families (Yasmine & Moughalian, Citation2016).

It is important to interpret the current results within the context of the research’s limitations. Firstly, the included participants comprise a convenience sample of beneficiaries who were accessing services and programs provided by the ABAAD Center for Gender Equality. They are not representative of the displaced Syrian population in Lebanon and the results therefore cannot be generalized. Detailed demographic information was not collected from FGD participants and it is quite likely that particularly vulnerable or marginalized individuals were missing from the sample due to not being able to access services and support. Secondly, the data was collected in Arabic but translated to English for analysis. In this process it is possible that some cultural and contextual nuances were lost. However, the translation was performed by a native Arabic speaker in Lebanon to help mitigate this risk and the local program manager and researcher was proficient in both languages and referred back to original Arabic texts as needed. And finally, the researchers recognize their positionality and note that as non-Syrian academics (SB and AB) and a civil society rights advocate (SM), the results are interpreted with our own biases and perceptions.

Conclusions

Our results illustrate the relationship between immigration status and economic insecurity as well as between immigration status and safety. Doing so highlights that immigration status may be an important contributor to child marriage among Syrian refugees in Lebanon. Our results further underscore the gendered impact of these factors on girls’ and women’s vulnerability to gender violence, in general, and child marriage, in particular. Intersectoral strategies are therefore required, including considering immigration policies, in a more comprehensive approach to address child marriage. We recommend additional research and policy analysis to better understand how immigration policies and legislation may predispose displaced girls to child marriage and impact marriage practices for displaced families more broadly.

| Abbreviations | ||

| FGD | = | Focus group discussion |

| IPV | = | Intimate-partner violence |

| GBV | = | Gender-based violence |

| UNHCR | = | United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees |

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the ABAAD Resource Center for Gender Equality for facilitating the focus group discussions and for making this work possible. We would like to thank all the participants for sharing their experiences and perspectives. This work would not have been possible without the financial support of the Sexual Violence Research Initiative and the World Bank Group.

Disclosure statement

None of the authors have any conflicts of interest to declare.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 L.L. = Lebanese lira.

References

- Abdulrahim, S., DeLong, J., Mourtade, R., Zurayk, H., Sbeity, F. (2016). The prevalence of early marriage and its key determinants among Syrian refugee girls/women: The 2016 Bekka study, Lebanon [www Document].

- Abu Shama, S. (2013). Early Marriage and harrassment of Syrian refugee women and girls in Jordan [WWW Document]. Amnesty Int. https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/campaigns/2013/09/early-marriage-and-harassment-of-syrian-refugee-women-and-girls-in-jordan/

- Adaku, A., Okello, J., Lowry, B., Kane, J. C., Alderman, S., Musisi, S., & Tol, W. A. (2016). Mental health and psychosocial support for South Sudanese refugees in northern Uganda: a needs and resource assessment. Conflict and Health, 10(18). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10/1186/s13031-016-0085-6

- Amnesty International Canada. (2013). Early marriage and harassment of Syrian refugee women and girls in Jordan [WWW Document]. Amnesty Canada Blog. http://www.amnesty.ca/blog/early-marriage-and-harassment-of-syrian-refugee-women-and-girls-in-jordan

- Bakhache, N., Michael, S., Roupetz, S., Garbern, S., Bergquist, H., Davison, C., & Bartels, S. (2017). Implementation of a SenseMaker® research project among Syrian refugees in Lebanon. Global Health Action, 10(1), 1362792. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10/1080/16549716.2017.1362792

- Bartels, S. A., Micheal, S., Rouptez, S., Garbern, S., Kilzar, L., Bergquist, H., Bakhache, N., Davison, C., & Bunting, A. (2018). Making sense of child, early and forced marriage among Syrian refugee girls: a mixed methods study in Lebanon. BMJ Global Health, 3. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10/1136/bmjgh-2017-000509

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10/1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Chaaban, J., Cunningham, W. (2011). Measuring the Economic Gain of Investing in Girls The Girl Effect Dividend [WWW Document]. World Bank Hum. Dev. Netw. Child. Youth Unit Poverty Reduct. Econ. Manag. Netw. Gend. Unit. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/730721468326167343/pdf/WPS5753.pdf

- Cherri, Z., Gonzalez, P. A., & Delgado, R. C. (2016). The Lebanese-Syrian crisis: Impact of influx of Syrian refugees to an already weak state. Risk Manag Healthc Policy, 9, 165–172. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10/2147/RMHP.S106068

- Child Protection Working Group. (2013). Syria Child Protection Assessment 2013 [WWW Document]. http://www.crin.org/en/docs/SCPA-FULL_Report-LIGHT.pdf

- Crenshaw, K. (1989). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory, and antiracist politics. Fem. Leg. Theory Readings Law Gend. 1. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10/4324/9780429500480

- Dionigi, F. (2016). The Syrian refugee crisis in Lebanon: State fragility and social resilience. UK.

- Ganchimeg, T., Ota, E., Morisaki, N., Laopaiboon, M., Lumbiganon, P., Zhang, J., Yamdamsuren, B., Temmerman, M., Say, L., Tunçalp, Ö., Vogel, J., Souza, J., & Mori, R. (2014). Pregnancy and childbirth outcomes among adolescent mothers: A World Health Organization multicountry study. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 121, 40–48. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10/1111/1471-0528.12630

- Global Communities - Partners for Good. (2013). Syrian Refugee Crisis - Global Communities Rapid Needs Assessment [WWW Document]. data.unhcr.org/syrianrefugees/download.php?id=3752%0A

- Guay, J. (2016). Social cohesion between Syrian Refugees and Urban Host Communities in Lebanon and Jordan [WWW Document]. World Vis. Behalf Soc. Cohes. Team Proj. https://www.preparecenter.org/sites/default/files/social-cohesion-clean-10th-nov-15.pdf

- Habib, R. R. (2019). Ethical, methodological, and contextual challenges in research in conflict settings: The case of Syrian refugee children in Lebanon. Conflict and Health, 13, 1–7. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10/1186/s13031-019-0215-z

- Henry, M. (2017). Problematizing military masculinity, intersectionality and male vulnerability in feminist critical military studies. Critical Military Studies, 3(2), 182–199. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10/1080/23337486.2017.1325140

- Human Rights Watch. (2018). World Report 2019: Lebanon [WWW Document]. Hum. Rights Watch. https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2019/country-chapters/lebanon

- Human Rights Watch. (2016). Lebanon: 250,000 Syrian Children Out of School [WWW Document]. Hum. Rights Watch. https://www.hrw.org/news/2016/07/19/lebanon-250000-syrian-children-out-school

- International Rescue Committee. (2015). Are We Listening? Acting on Our Commitments to Women and Girls Affected by the Syrian Conflict [WWW Document]. https://www.rescue.org/sites/default/files/resource-file/IRC_WomenInSyria_Report_WEB.pdf

- Janmyr, M. (2017). No Country of Asylum: “Legitimising” Lebanon’s Rejection of the 1951 Refguee Convention. International Journal of Refugee Law, 29(3), 438–465. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10/1093/ijrl/eex026

- Janmyr, M. (2016). Precarity in exile: The legal status of Syrian Refugees in Lebanon. Refugee Survey Quarterly, 35(4), 58–78. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10/1093/rsq/hdw016

- Maslow, A. (1943). The theory of human motivation. Psychol. Rev, 50(4), 370–396.

- McCall, L. (2005). The complexity of intersectionality. Signs (Chic), 30(3), 1771–1800. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10/1086/426800

- Michael, S., Fenning, G., Saleh, R., & Marcella, R. (2018). SGBV BASELINE ASSESSMENT: SGBV trends, risk factors and coping mechanisms among Syrian Refugee Communities in the Bekaa-Lebanon.

- Mourtada, R., Schlecht, J., & Dejong, J. (2017). A qualitative study exploring child marriage practices among Syrian conflict-affected populations in Lebanon. Conflict and Health, 11(Suppl 1), 27. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10/1186/s13031-017-0131-z

- Nguyen, M. C., Wodon, Q. (2014). Impact of child marriage on literacy and education attainment in Africa [WWW Document]. World Bank Glob. Partnersh. Educ. http://allinschool.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/OOSC-2014-QW-Child-Marriage-final.pdf

- Nour, N. M. (2006). Health consequences of child marriage in Africa. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 12(11), 1644–1649. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10/3201/eid1211.060510

- Nove, A., Matthews, Z., Neal, S., & Camacho, A. V. (2014). Maternal mortality in adolescents compared with women of other ages: evidence from 144 countries. The Lancet Global Health, 2(3), e155–e164. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10/1016/S2214-109X(13)70179-7

- Parsons, J., Edmeades, J., Kes, A., Petroni, S., Sexton, M., & Wodon, Q. (2015). Economic impacts of child marriage: A review of the literature. Review of Faith and International Affairs, 13(3), 12–22.

- Raj, A. (2010). When the mother is a child: the impact of child marriage on the health and human rights of girls. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 95(11), 931–935. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10/1136/adc.2009.178707

- Save the Children Fund. (2014). Too young to wed – The growing problem of child marriage among Syrian girls in Jordan.

- Sexual Rights Initiative. (2013). Analysis of the Language of Child Early and Forced Marriages [WWW Document]. https://www.sexualrightsinitiative.com/sites/default/files/resources/files/2019-04/SRI-Analysis-of-the-Language-of-Child-Early-and-Forced-Marriages-Sep2013_0.pdf

- Spencer and Care International. (2015). “To Protect Her Honour”: Child Marriage in Emergencies – the Fatal Confusion Between Protecting Girls and Sexual Violence, Gender and Protection in Humanitarian Contexts: Critical Issues Series #1.

- The World Bank. (2015). Syrian refugees living in Jordan and Lebanon: Young, female, at risk [WWW Document]. World Bank Press Release. http://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2015/12/16/syrian-refugees-living-in-jordan-and-lebanon-caught-in-poverty-trap

- UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. (2017). Government of Lebanon, Lebanon crisis response plan 2017-2020 [WWW Document]. http://reliefweb.int/report/lebanon/lebanon-crisis-response-plan-2017-2020-enar

- UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. (1989). Convention on the Rights of the Child [WWW Document]. United Nations. http://www.ohchr.org/en/professionalinterest/pages/crc.aspx

- UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. n.d. Convention on consent to marriage, minimum age for marriage [WWW Document]. United Nations. http://www.ohchr.org/EN/ProfessionalInterest/Pages/MinimumAgeForMarriage.aspx

- UN Women. (2013). Inter-agency AssGender-based Violence and Child Protection among Syrian refugees in Jordan, with a focus on Early Marriage [WWW Document]. http://www.unwomen.org/-/media/headquarters/attachments/sections/library/publications/2013/7/report-webpdf.pdf?vs=1458

- UN Women. n.d. Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women [WWW Document]. United Nations. http://www.un.org/womenwatch/daw/cedaw/

- UNFPA. (2017). New study finds child marriage rising among most vulnerable Syrian refugees [WWW Document]. UNFPA. http://www.unfpa.org/news/new-study-finds-child-marriage-rising-among-most-vulnerable-syrian-refugees

- UNICEF. (2016a). Hitting Rock Bottom: How 2016 Became the Worst Year for Syria’s Children [WWW Document]. UNICEF. http://childrenofsyria.info/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/SYRIA6-12March17.pdf

- UNICEF. (2016b). Child marriage: Child protection from violence, exploitation and abuse | UNICEF [WWW Document]. UNICEF. https://www.unicef.org/protection/57929_58008.html

- UNICEF. (2014a). Under Siege: The devastating impact on children of three years of conflict in Syria [WWW Document]. URL http://www.unicef.org/publications/index_72815.html

- UNICEF. (2014b). A study on early marriage in Jordan [WWW Document]. UNIECF Jordan Ctry. Off. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10/1007/s13398-014-0173-7.2

- United Nations. n.d. Universal Declaration of Human Rights | United Nations [WWW Document]. United Nations High Comm. Refug. http://www.un.org/en/universal-declaration-human-rights/

- United Nations Population Fund. n.d. New study finds child marriage rising among most vulnerable Syrian refugees | UNFPA - United Nations Population Fund [WWW Document]. URL https://www.unfpa.org/news/new-study-finds-child-marriage-rising-among-most-vulnerable-syrian-refugees

- World Vision International. (2012). Robbed of Childhood, Running From War [WWW Document]. URL http://www.wvi.org/sites/default/files/RunningfromWarFINALUPDATED.pdf

- Yasmine, R., & Moughalian, C. (2016). Systemic violence against Syrian refugee women and the myth of effective intrapersonal interventions. Reproductive Health Matters, 24, 27–35. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10/1016/j.rhm.2016.04.008