Abstract

The current study focuses on care for West African Victims of human trafficking (VHTs) in The Netherlands and addresses the question of how (1) social and legal professionals and (2) religious leaders of African-led migrant (Pentecostal) churches perceive their relationship with these VHTs. Thematic analyses of qualitative interviews (N = 21) revealed that both groups share the perception that VHTs are vulnerable, especially in view of so-called voodoo spells. Social and legal professionals noticed that West African VHTs prototypically appear as ‘demanding’ in a rather pro-active manner. Religious leaders on the other hand indicated that the VHTs feel at ease in the church in a more adaptive sense and may find ways of changing their lives after experiencing the Pentecostal “deliverance” ritual.

Introduction

Victims of human trafficking (VHTs) arriving in western European countries face complex tasks in finding their way toward a safe and meaningful living environment. They must cater to the most essential socio-economical needs and aspire to ease their minds after a period that, in many cases, is marked by emotional turmoil, frequently including traumatizing events. Although the majority of the VHTs in Europe come from European countries, there is a substantial minority, estimated at nearly 20 per cent, that arrives from outside Europe (United Nations Office on Drugs & Crime, Citation2014, p. 60). Among the victims from outside Europe, the largest group – about one third – originate from western sub-Saharan Africa, Nigeria in particular. In the Netherlands, about 200-300 sub-Saharan African VHTs – of which about 90 per cent are female – were each year recorded by the registration authorities between 2010 and 2014 (Nationaal Rapporteur Mensenhandel en Seksueel Geweld tegen Kinderen, Citation2015). Many of these African VHTs are moved between cities or across national borders, have no legal status and face considerable problems in attaining this status at all (Gemmeke, Citation2013).

In Western Europe, victims of human trafficking from West Africa are likely to receive care from at least two sources: professional (social and legal) refugee care based on secular notions of providing help and support and as such organized by secular institutions in society, and religious care usually organized within the context of African-led migrant churches. Professional caregivers in Western Europe are often unfamiliar with this particular African migrant setting of religious care structures. While especially in cultural anthropology, the interrelatedness of health – physical as well as mental – and religion has long been a terrain of study (Csordas, Citation1994; Werbner, Citation2015 [note 1]), recent developments in socio-psychological research on the relation between health and religion (Koenig et al., Citation2012) make this lacuna among legal and care professionals even more pronounced.

In the Netherlands, this type of recent research focuses on the role of religion in mental health care. Empirical studies on religion and mental health in the Netherlands (Braam et al., Citation2010; Pieper & Van Uden, Citation2005) have demonstrated that for clients and patients, religiosity (e.g. an intrinsic religious motivation or religious practices) is often of considerable significance for coping with mental disease. Concepts like ‘religious coping’ (Pargament, Citation1997; Tepper et al., Citation2001) and ‘religious security’ (Leutloff-Grandits et al., Citation2009) pinpoint the impact of religion, its practices, and ways of viewing the world for meaning-making, dealing with loss, mourning, and the search for an emotional balance, as well as for creating a meaningful relationship with the social environment of the individual. Nevertheless, in both sources of care (representing either a form of ‘coping’ or a form of ‘security’) there is a tendency to consider and use religion as a tool and thus to instrumentalize its meaning and understanding. Consequently, we run the risk of implying that the more fundamental meaning of religion as part of one’s complex identity is neglected. In the Discussion section, this problem will be discussed on the basis of this study’s results.

On the other hand, religious leaders and volunteers of migrant religious communities in Western Europe may (potentially) not be fully informed about specialized and professionalized trauma care, what it can offer and how to access it. The two sources for care thus substantially differ in their basic notions of help and support, which complicate the process of how emotions and care needs can be profitably addressed. In general, the tensions between the two sources can be understood as a result of the history of cultural, social, and political secularization that has characterized not only the Global North since the beginning of modernity, but also other parts of the world. Recent scholarship in anthropology has challenged this perception of secularism as an exclusive European invention; the ‘multiple secularities’ perspective (Burchardt et al., Citation2015) challenges Eurocentrism here and decenters Europe by pointing at non-Western cultural forms of secularity that have emerged elsewhere. This implies that Africa also has its forms of secularism and therefore African migrants into Europe may not experience European secularism as something entirely new or strange (Burchardt et al., Citation2015). The implication of this being that from a religious perspective in these African migrant communities, secular forms of care may also become the subject of criticism, if not straightforward rejection.

However, while in Western societies in particular a radical secular-religious divide emerged (as it is called nowadays in philosophical scholarship), in recent decades this divide has come under pressure: a process that is often analyzed as a ‘post-secular’ period of a ‘return of religion’ (Habermas, Citation2003; Habermas, Citation2004; Joas, Citation2008; Vattimo, Citation2002; Berger, Citation1999; Kate et al., Citation2012). European philosophy is thus challenged by the ‘multiple secularities’ perspective as indicated above, forcing it to start looking beyond its own cultural borders. The problematic state of this secular-religious divide is particularly apparent in the two sources of care explored here.

Among professional caregivers, one can observe an embarrassment about religion making it impossible to acknowledge it as a practical and concrete phenomenon in society (Pieper & Van Uden, Citation2005). Western societies appear strongly secularized, and religious frames of reference are increasingly disqualified from the representation of professionalism in the public sphere.

Care professionals are not alone in this embarrassment. It is a fundamental condition of late-modern culture, as Charles Taylor points out in his A Secular Age (2007). And yet he maintains that modern secular societies do not render religion superfluous; on the contrary. Taylor states that the ‘secularity’ of the secular age consists of new ‘conditions of belief’ that reformulate religious traditions on the one hand, while challenging and transforming the secular mode of living and thinking on the other. Taylor develops a framework in which religion and secularity are no longer seen as divided, but in fact lead to new accommodations that appear to become increasingly relevant in many sectors of life, including – as we argue – the field of care. We contend that the care offered to West African VHTs forms one of the many examples of this complexity. When VHTs enter European, post-secular societies, and engage social practices like care, they involve their own pluralism of religious and secularized worldviews. They, too, bring their experiences of the questioning of religion from their own cultural milieus; hence, skepticism with regard to religious and secular worldviews is not strange to them, which, in turn, complicates matters when it comes to approaching both systems of care – the care offered by religious authorities and groupings, as well as the care offered by professionals.

So far, we have approached religion as a general phenomenon. In speaking about religion as a general and necessarily abstract concept we follow current philosophical and innovative accounts of religion, as in the critical debates on post-secularism (e.g. Assmann, Citation2008; Taylor, Citation2003). However, religion is never a general phenomenon to be grasped in a universal concept but needs to be situated in a plurality of particular socio-cultural contexts in order to become meaningful in the first place (De Vries, Citation2008). In this study the focus lies on a specific context: many West African migrants have joined religious communities that can be classified as Pentecostal (Anderson, Citation2014; see the next section for a further brief account). In the following analyses, the term ‘religion’ is used in this limited meaning referring to the West-African Pentecostal context.

As far as West African Pentecostalism is concerned, the dynamics of care as offered in the situation of migration are complex. The West African Pentecostal domain is determined by particularly moral and inspirational Christian convictions and a this-worldly outlook on social reality that, in many cases, emphasizes achieving economic prosperity and following an individualistic lifestyle (Kalu, Citation2008). The personal relationship with God leads toward a rather radical submission and surrender to the charismatic power of the Holy Spirit in church services. Outside the context of the church, this personal relationship continues to shape the social identity of the believer as a person who lives a modern and hence post-traditional lifestyle (Lindhardt, Citation2011). Many Pentecostals view their identity as being newly shaped by holding a critical distance from the West African cultural and societal conditions, and from Western societies as well (Dijk, Citation2004): in some sense, they construct a new ‘third way’ identity. In recent literature this is addressed as powerfully decentering Europe by adhering to a transcultural Pentecostal identity that allows for association with a large and globally expanded Pentecostal domain that is capable of situating itself in Africa and elsewhere in the world (Krause & Dijk, Citation2016; Dijk, Citation2001, Citation2002a).

All of this produces a complex dynamic in which this dominant form of West African Pentecostalism and the care its leaders offer may not be fully understood or appreciated by professional caregivers and vice versa. The current study aims to highlight the main perceptions of cultural identity and care needs of West African VHTs that are current among key actors who provide practical, social, legal, and religious care for this specific group. Employing qualitative interviews, the different perceptions of cultural identity, relationality, and care are assessed for two groups. The first group can be characterized as ‘Western’ and includes legal and (social) care professionals in the Netherlands. The second group consists of Pentecostal clergy in the Netherlands (‘religious leaders’). The following research questions are addressed:

1. Which perceptions about the cultural identity and care needs of West African victims of human trafficking are reported by legal and care professionals in the Netherlands? Do legal and care professionals recognize and acknowledge religious convictions and practices as a potential and/or prominent element in the lives of their clients?

2. Which perceptions about the cultural identity and care needs of West African victims of human trafficking are reported by leaders of African led migrant churches? Do religious leaders acknowledge the potential of professional (trauma) care in Western Europe? Before presenting the results of the current study, a brief background is offered on the significance of Pentecostalism in West Africa and for the West African migrant communities in the Netherlands.

West African Pentecostalism and African led migrant churches in Western Europe

Pentecostalism is known to be a particular form of Protestantism but is distinct from other forms of Protestantism precisely because of its charismatic leadership, its ecstatic meetings (‘pneumatic phenomena’ such as speaking in tongues and healing practices; Asamoah-Gyadu, Citation2014; Lindhardt, 2015) and religious practices, and because of its strict ideology concerning personal morality. There does not exist an entire scholarly consensus about how to define Pentecostalism (Maltese et al., Citation2019): there is considerable overlap between the term ‘Pentecostal’ and closely related indications such as ‘charismatic’, ‘evangelistic’ and ‘evangelical’. Therefore, Maltese and colleagues advise to study Pentecostalism “within the discursive conditions in which it emerges as object” (Maltese et al., Citation2019, p. 13). In the current study, this pertains to West African Pentecostalism and its connections to migrant churches in Western Europe.

In short, Pentecostalism in West Africa became particularly known because of its determined rejection of many African historical religious and ritual practices. A dictum in their ideology became: ‘make a full break with the past’ (Meyer, Citation1998). The notion of this break with the past is that a born-again person can only be established as a confirmed believer if specific rituals have taken place that aim at breaking relations with ritual practices, ancestors, and any traditional healing that may have taken place in one’s personal past. The rituals, known as ‘deliverance’, are aimed at creating a ‘breakthrough’ (see among others Dijk, Citation1997; Meyer, Citation1998) as a result of which the person can feel ‘armored’ by the Holy Spirit in the pursuit of wealth and well-being and can no longer be blocked by any traditional spirit or ancestor (see e.g. Kamp 2016 for a recent ethnographic study).

The notion of creating ‘breakthroughs’ in personal circumstances, in success, and prosperity made this new Pentecostal movement highly attractive to new middle and entrepreneurial classes. Countries with upcoming markets and urban economies, such as Ghana and Nigeria, began to witness the booming of what came to be called ‘prosperity churches’ (Gifford, Citation2004). The ‘prosperity gospel’ became one of the most important ideological lines in this form of Pentecostalism. In both countries, so-called megachurches emerged (Cartledge et al., Citation2019; Gifford, Citation2016), led by a charismatic leader who usually excels in conducting electrifying deliverance sessions that are attended by thousands of aspiring followers. These charismatic churches expanded their activities through the effective use of their own radio, television, and video-production facilities as well as the use of the social media (Faimau & Lesitaokana, Citation2018).

Increasingly, these churches also placed themselves in global circles of exchange and became transnational by establishing their branches in Europe (as well as the Americas and Asia), especially where communities of West African migrants can be found (Knibbe, Citation2010; Dijk, Citation2001; Währisch-Oblau, Citation2016). In many Ghanaian and Nigerian migrant communities (such as in the United Kingdom, The Netherlands, or Germany), these charismatic churches play an important role in social and religious life (Kalu, Citation2008, pp. 287–288, Adogame, Citation2013) . As Währisch-Oblau (Citation2016) indicates for the German situation, Pentecostal religious leaders are mostly migrants themselves. They produce their own materials, engage in international travel as preachers, and are active on the internet. In this context too, leaders offer ‘authority prayers’ or ‘prayers of command’ to effectuate deliverance, healing or ‘breakthroughs’ that are aimed at defeating spirits or powers that are considered responsible for causing certain problems in the life of the migrants. As also a recent literature on affective repertoires is indicating (see some of the contributions to Cole & Groes, Citation2016; Dilger et al., Citation2020), the religious identity and care that is offered in and through Pentecostalism to migrants in the complexities of their migrant-situation is as much social and spiritual as it is emotional. Pentecostalism is of significance as a way of reaching out to people, although this is primarily directed to migrant groups and not to native Germans. While in certain European countries, such as the United Kingdom, the African led migrant Pentecostal churches seem to have become more sizeable (Hunt & Lightly, Citation2001), in Germany (Währisch-Oblau, Citation2016) and The Netherlands (Knibbe, Citation2010; Dijk, Citation2004), they have remained rather small in size although still proliferating.

Methods

To examine the perceptions about the cultural identity and care needs of West African VHTs, a qualitative approach was chosen. Qualitative research provides the opportunity to observe how people create a social reality, how they give meaning to it, and what kind of relationships they have (Boeije, Citation2005). The current study explores the research questions in a heuristic way: as a point of departure there was no specific coherent theoretical frame, but insights from the literature were utilized for further definition of themes that emerged from exchanges with our interlocutors. Semi-structured, in-depth interviews provided the exclusive source of information – no other sources were utilized in the current study.

Sample and procedure

Researchers from the University of Humanistic Studies utilized the extensive network of the FairWork Foundation [note 2] that provided access to care professionals and legal professionals. Based on this network of the FairWork Foundation, potential respondents were approached in a wide range of organizations, such as organizations specialized in social welfare for sex-workers, organizations for social housing and sheltered living facilities, police, and the International Office for Migration. The respondents from a number of African religious communities were all identified by the researchers themselves (e.g. by using personal contacts, the internet, and snowballing).

All respondents were informed about the research procedures and agreed to be interviewed about the VHTs they encountered in their communities or work and on the basis of this informed consent agreed with the presentation of anonymized results.

The empirical data were collected using semi-structured, in-depth interviews of about 1.5 hours with 21 professionals from ten different organizations and six different migrant Pentecostal churches. The interviews took place in 2013–2014. The first subsample is defined as ‘legal and care professionals’: five professionals were active in care, such as social workers or care coordinators; two professionals worked for the Immigration and Naturalization Office; and four were police officers. The care professionals were all female, aged on average around 40. Most legal professionals were male, aged on average around 50. Four professionals visited West Africa at some moment in their lives. All professionals grew up in a Christian tradition (e.g. Roman Catholic or Reformed Protestant), but only a few still had affinity with religious beliefs or spirituality. The interviews in this subsample were conducted in the Dutch language.

The second subsample is defined as ‘religious leaders’: five pastors and two active volunteers. These interviews were conducted in English. The religious leaders were all born in West African countries, were predominantly male (one volunteer was female), and the average age was about 40. They have lived in the Netherlands for about 20 years (range 10-30 years).

For both series of interviews, the researchers employed a topic guide based on theory, actual needs in the field as noticed by the FairWork Foundation, and supplemented by subsequent topics that heuristically emerged during the extended interviews and based on the researchers’ uncovering of key issues during previous interviews. Topics included the background of the participant, the organizations’ mission and vision, their positive and negative experiences in their contact with the VHTs, and their perceptions of the VHTs with respect to needs, values, and religious convictions.

In both subsamples, the interviews concentrated on exploring deeper insights into the experiences, feelings, and thoughts of the professionals. Five of the 21 interviews were conducted jointly by the two researchers (JvR and FB). In the first series, 12 of the 14 interviews were conducted at the workplace, in the same room as where the professional would otherwise be in contact with VHTs; the other interviews took place outside of the workplace setting. The second series of interviews took place in the offices of the religious leaders within the church environment. The interviews included both ‘mapping’ and ‘mining’, leading to a situation in which, at a certain point, specific concepts and statements started to recur; this was taken as a sign of information saturation.

The interviews were transcribed and were coded by employing the coding program Atlas.ti. The thematic analyses started with inductive, ‘open coding’, where possible ‘constructed codes’ as far could be related to available theory. This was followed by ‘axially and selective coding’ using the Boeije method (2005) as a guide, with an emphasis on integration of the identified themes and their interrelationships.

A limitation of the current study is that the VHTs themselves were not interviewed. This is because approaching the VHTs for interviews is very complicated in the context of ethics and (legal) procedures. Any contact demands substantial care because of their vulnerability and their tendency toward avoidance.

Results

Care professionals and legal professionals

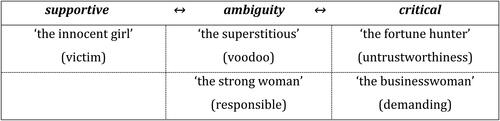

The qualitative analysis yielded several main codes, defined as ‘perception components’, entertained by the professionals of the West African VHTs indicating the extent to which religious identities, experiences and practices matters. The following perception components of West African VHTs were discovered: ‘the strong woman’; ‘the fortune hunter’; ‘the innocent girl’; and ‘the businesswoman’. Although less pronounced in the interviews, a fifth component is added: ‘the superstitious’. As summarized in , the perception components consist of a variety of ways of perceiving the victim, reflecting characteristics of both the professional and the victim, as well as the context of their connection. As a general finding, all interviews with the professionals contained a degree of ambiguity, illustrating the difficulty of expressing how victims are perceived in a single statement. Within each professional’s perception of the victims, contrasting or opposing components co-occur, as one of the participants, a care coordinator, stated: ‘Also within the organization I notice that it's a difficult group of people. They come across as very strong and they are very vulnerable at the same time. Their level of likeability (‘being pettable’) is not so high.’ [All quotes from respondents are translated from Dutch.]

Figure 1. Diagram with the five main codes, as extracted from interviews with legal and care professionals, with components of their perceptions of West African victims of human trafficking (VHTs).

Although many of the professionals perceive the VHTs as being vulnerable, helpless, and innocent, the mixed, ambiguous perceptions of the VHTs cause a certain degree of confusion. The different perceptions of the VHTs appear to depend on the situation. For example, as one of the care workers noticed, the victims’ splendid outer appearance during church ceremonies makes it hard to recognize them as victims and is in stark contrast to how they appear in other situations. The ambiguous, simultaneous components of perceptions of the VHTs by the professionals is apparent from a mix of a sincere concerns and skeptical responses for each of these categories.

‘The strong woman’

The professionals report several aspects of ‘strength’ and stated that, in view of their physical appearance, the West African VHTs cannot simply and stereotypically be classified as vulnerable. More nuance is required here, as the following professional, a migration officer, indicated: ‘I would call them bolder than others, more edgy, bold simply according to their appearance. (…) Yes, more like that they are able to “pass through the windows”.’

As a second aspect of strength, the professionals, and the police officers in particular, consider the victim’s decision to contact the police a sign of courage. Thirdly, the strength of the VHTs is also noted as involving an attitude of responsibility toward their relatives in Africa, who may have high expectations of the material success that the VHTs in Europe will achieve.

‘The fortune hunter’

While this term bears a negative connotation and is often more used by legal and police professionals than by the care professionals, it tends to represent the professionals’ feelings of suspicion, resulting from a certain degree of (remarkable) similarity between the accounts of VHTs. Some police officers therefore often lack confidence in the VHTs’ statements: ‘You will never solve it. It's the same story over and over. So little detail. Often, they escaped from a house, you know, with trees, a red roof and a white front door. Just go and look for it, you won’t find it.’

According to the professionals, some of the victims might report, or reframe, their story of maltreatment and abuse to apply for a special legal status as a victim, which prevents deportation. Professionals often qualify these types of reports as a sign of calculating behavior and dishonesty. In turn, this leads to prejudices: some professionals reported that colleagues simply disqualified Nigerians as liars (‘Nigerians – Lie-gerians’). The emphasis on ‘truth’ among legal and police officers may be at work here as well, causing institutional ways of ‘othering’, preventing officers from taking the matter seriously for Nigerian and other West African VHTs.

‘The innocent girl’

The professionals also perceive VHTs as vulnerable, deceived, abused, and traumatized. Police officers even recognize this vulnerability as a cause of what they see as probably untruthful statements by VHTs. The professionals perceive an inescapable pressure on victims produced by voodoo-like rituals. As one police coordinator stated: ‘Because of that voodoo pressure, it is immense, as far we hear it, that they choose, that they prefer to continue to work in the prostitution scene, rather than breaking the voodoo promise. That’s because they are totally convinced that otherwise they will suffer something terrible, or worse, that something terrible occurs to their relatives.’

Another aspect of vulnerability is reflected by the assumption of several professionals that many victims have a low level of education, are illiterate, or less intelligent. In turn, according to the legal professionals, the traders in human trafficking have accurate knowledge at their disposal about the legislation in Western Europe and how to adapt their practices and traveling routes accordingly. This provides a power difference between the traders and their victims, for whom it will become very hard to escape the ongoing situation of exploitation. Indeed, professionals feel that some victims remain in the prostitution scene as a madam because of the lack of any other prospects – thus, the victim remains a victim and becomes an exploiter herself.

‘The businesswoman’

According to the professionals, West African VHTs have been used to a world of corruption and poverty in their countries of origin. They have learned that they will not survive unless they stand up for themselves. Therefore, the persistence and militancy of the victims is regarded as both impressive and troublesome. According to the professionals, VHTs rarely show signs of gratitude for their help, as is illustrated by the report of a social worker: ‘These Nigerian women, I think they are very strong, they know what they want. I think they are calculating; they are businesswomen. Also, in relation to me, for sure. If they can negotiate, they will. I think they are fighters, ambitious women. And mistrustful.’

In the perception of the professionals, some VHTs treat them in an instrumental way, focusing on the possibility of claiming more than what has been offered. The victim’s vigilance, unpredictability, and fierceness sometimes require the professionals to limit the demands that the VHTs place upon them. Some professionals interpret the fierce reactions and outbursts by the victims as a culmination of their feelings of tension and frustration. Often, more appropriate communication of their feelings is blocked by what the professionals see as their habitual sub-assertiveness and tendency to withdraw. In one way or the other, the professionals believe they need patience in their work with the VHTs.

‘The superstitious’

According to the professionals, all VHTs are Christian; yet at the same time, all VHTs are under the spell or pressure of ‘voodoo’ (Baarda, Citation2016). Often, professionals have little or no interaction with religious groupings, although they are generally happy if the victims feel supported by their faith. Especially the police officers have heard about the ‘voodoo’ threat and are very concerned about this aspect: ‘No, it is really difficult, that a lot of these women are caught, basically, by their voodoo beliefs and that they are entrapped in these convictions, but, in a way still truly persist in some of these beliefs.’

The professionals consider ‘voodoo’ a superstitious conviction. However, challenging these oppressive convictions proves to be complex, as one care coordinator illustrated: ‘If you are threatened that they will kill your family when you do not obey them, you cannot play jokes, challenging their promises. So, it [voodoo] suppresses them, captures them in their situation.’

The professionals also noted that many VHTs adhere to Christian beliefs, which seem to be supportive, although many victims rely on God’s providence in a way that is difficult to imagine for the professionals, as is phrased by a social worker: ‘Yes, almost all of them are religious and they believe that God will change their lives, improve and even will prevent a negative decision by the Immigration and Naturalization Office.’

Some professionals notice that the Christian (Pentecostal) churches provide a way to escape ‘voodoo’, by attending rituals of deliverance.

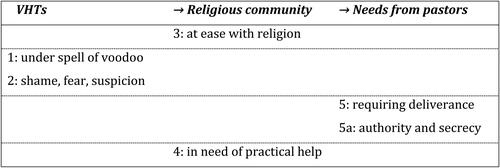

Religious leaders

Analysis of the interviews with the religious leaders yields five main codes. The main codes reflect five components of perception, most of which directly relate to the needs of the VHTs as perceived by the religious leaders. The five components include: ‘under spell of voodoo’; ‘shame, fear, and suspicion’; ‘at ease with religion’; ‘in need of social support’; and ‘requiring deliverance’ (). All interviewees considered involvement and support by religious communities as important to VHTs and an integral part of their lives. Furthermore, they formulated a variety of needs and types of involvement, as reflected in the aforementioned components. The pastors were not conclusive in their opinions about the need to fully involve African migrant religious communities in the care of VHTs. Some expressed substantial confidence. Others thought that only a minority of VHTs were really able to profit from religious involvement and that this process requires great patience.

Figure 2. Diagram with the five main codes and one subcode, as extracted from interviews with religious leaders, participating in migrant Pentecostal denominations in The Netherlands, with components of their perceptions of West African victims of human trafficking (VHTs).

‘Shame, fear, and suspicion’

This notion expresses the suffering of the victims, their difficulty and reluctance to get into contact with others, including members of African-led migrant churches. This perception relates to the component of taboo, but also to the dreadful consequences of exploitation. For example, one pastor articulates the extremely negative self-image of the victims as: ‘And you’ll look at yourself as if you are not a human being.’

‘Under the spell of taboo’

Almost all participants expressed their concerns about the victims suffering from the belief in, and the subsequent perceived pressure of, voodoo rituals as enforced by the traders before the victims traveled to Europe. Some talked about their interpretation of the voodoo beliefs that they see as being endemic in certain regions in West Africa: ‘[…] it is a kind of belief. An agreement that they make. They get something like a black covenant. We Africans have all kind of sort of black magic. They take something from your body, it will be more powerful. These things physically affect people.’

‘At ease with religion’

Most religious leaders describe how VHTs tend to be more open when they are in contact with the church. The VHTs are, as the majority of people in West Africa is, qualified by them as being ‘extremely religious’. The religious community members pray with the VHTs, thus providing a comfort zone, spiritual support, and encouragement. One pastor considers this mutual religious involvement as a condition for further contact: ‘So, take out their faith and you get nothing from them.’

Here, ‘religion’ also pertains to the broader cultural scope of meaning-making, as considered by the religious leaders: ‘Back in our culture, there is a meaning to every dream […] They tell me all the time, why should I tell the Dutch social worker, they don’t understand me.’

‘Requiring deliverance’

Following from the previous, all participants emphasized the role of the ritual of deliverance as a means to break the spell of voodoo. Deliverance is seen as ‘highly individual’ and is generally applied without the presence of any other participant apart from the pastor and the worshiper. The pastor should be experienced in this matter and needs to decide on the best individual approach to guide the person through the process of deliverance. In essence, deliverance is described as a way of prayer, but it can include other efforts, such as a period of fasting afterwards. The goal of deliverance is transformation – the victims of the voodoo spell learn to experience protection by God. According to some pastors, it also has a psychological effect, of ‘letting go’, and of change. A subcode, related to this component of deliverance, is that the pastor is seen as a religious authority and that he (or she) adheres to secrecy.

‘In need of practical support’

The majority of the participants describe venues to help the victims with their practical needs: assisting with finding housing, shelter, providing some financial support, taking care of kids, a job, training for the future, and education. This latter point also pertains to the need to learn about the possibility of professional, psychological treatment. As one of the spiritual leaders put it: ‘They are every day and every week in the church or church community. We live with them. We provide shelter, food, we give support to the babies. […] When they are traumatized, who do they speak to? It is the spiritual leaders.’

Discussion

General analysis of the results

The current study addresses the question of how, in a western European country, social and legal professional caregivers as well as Pentecostal leaders perceive ways of relating to West African VHTs in situations of providing them with care. From a historic and anthropological point of view, understanding the care needs of VHTs seems dependent on their cultural and religious traditions. It is in this context that the contemporary rise of African Pentecostalism deserves attention. Pentecostalism combines Christian religiosity and its moral dialogue with historical African religious traditions and the pursuit of material prosperity. To what extent are the care professionals informed by the ways in which Pentecostalism situates itself in the lives of the VHTs who have migrated to countries in Western Europe such as the Netherlands?

The qualitative interviews with social and legal professionals in the Netherlands yielded several ‘perception components’. These perceptions showed profound ambiguity and a considerable amount of contrast, ranging from positive and supportive perceptions to critical and disqualifying perceptions. With respect to the religiosity of the VHTs, the perceptions of the social and legal professionals seemed to emphasize these as being ‘superstitious’ in nature. This was not simply due to an entire ‘secular’ disregard of the intrinsic value of the role of religion in the lives of the VHTs: while most social and legal professionals had no close affinity with religion, all professionals had a Christian background.

The qualitative interviews with the religious leaders of African-led migrant churches in the Netherlands showed some overlap with the perceptions of the social and legal professionals. Here, the VHTs were perceived as victims: in their need of practical support, in their suggested ‘missing knowledge or lacking intelligence’, and in their beliefs in voodoo spells (although the religious leaders seem to interpret this as rather knowledgeable as they can frame it within their cultural setting). The religious leaders emphasized the role of the religious community as accommodating the VHTs as they are accepting practical help and utilizing the religious ritual of ‘deliverance’. Furthermore, the professionals and the religious leaders share a certain amount of ambiguity in their perception, especially the ambiguity of troublesome strength, something the religious leaders seem to interpret more in the lines of mistrust toward the professional caregivers. Here, one can assume the presence of intersecting ambiguities about the VHTs. Awareness of these ambiguities may be relevant to discourage stereotypes or prejudices about West African VHTs (Gemmeke, Citation2013).

According to the perceptions of the religious leaders, VHTs, as far they have been in contact with the leaders, attempt to cope with their situation by relying on religious notions and practices. Those VHTs connecting with religious communities are seen to be ‘at ease’ with a religious environment that generally relates to their cultural background. Eventually, they may enter the ritual of deliverance, which can help them to change (‘let go’) of their original perceptions of ‘voodoo’. This may subsequently open the way to dissolving the ties of victimhood, so the religious leaders claimed, and to restoring their sense of dignity and autonomy. While the VHTs may profit from the help of professional caregivers – socially and psychologically – in relation to the treatment of trauma, in view of the religious leaders, the VHTs would rather mobilize or utilize ways of religious coping.

Religious coping in discussion

By comparing the statements of the two groups of main actors (care professionals and religious leaders), we can see that the notion of ‘religious coping’ acquires at least two fundamentally different meanings. On the one hand, we see particularly in the statements by the care professionals that religious coping primarily means its inverse; namely, coping with religion. In their reflections, religion becomes a force to be reckoned with, not easily controllable, and rather difficult to be turned into an instrumental device that has the potential to help and assist people in dealing with difficult situations. Rather, their position is that they need to cope with religion as a potentially harmful force that, through ritual practices associated with the voodoo threat, may jeopardize the VHTs’ position and their access to care and support. One of the key questions for them is actually how to appreciate their clients’ religion as being a form of assistance. Mostly paying lip-service to the idea, there seems to be only a rudimentary understanding at the level of the professional care-providers of the extent to which religion may indeed be a force and a domain that can assist people in coping with their personal circumstances. Added to this lacuna in understanding is the cultural divide, which only seems to increase the impossibility on the part of the professional care providers of acknowledging the potential of non-Western religious practices serving as a means of coping.

While it is certainly not the intention of our present contribution to simply and exclusively reify religion as a ‘coping mechanism’ (which would do a great injustice to the wide variety of experiences that characterize people’s engagement with it), the responses of the religious leaders resonate remarkably with a view that places religion primarily in the perspective of producing ‘coping’, ‘certainty’, ‘identity’, and ‘assistance’. In a way diametrically opposed to the professional care providers, it seems that their statements first of all define their religious practices of providing care not so much in their own terms of religious inspiration but in a more secular register of ‘coping’. The question is, how can we understand and interpret the fact that these Pentecostal leaders appear so interested and vocal in defining their intrinsically meaningful ritual practices as forms of ‘religious coping’?

As stated in the Introduction, a theoretical and practical framework of religious coping has been offered by the American psychologist of religion Pargament (Citation1997). According to Pargament, religious coping includes pathways, such as types of religious convictions and behaviors, as well as destinations, objects of (existential) significance and ultimate concern. With respect to these pathways and destinations, people can either maintain them, or opt for a change in pathway, in destination, or in both. Here, Pargament creates a dynamic model of religious coping. The initial inclination is ‘preservation’ of both pathways and destinations. When the destination remains the same, but the pathway is changed, this is called ‘reconstruction’ (e.g. switching denominations, purification rituals). On the other hand, when the pathways remain the same, but the destination changes, such as after a rite of passage, ‘re-valuation’ occurs. Finally, when both the pathways and the destinations change, ‘re-creation’ takes place – conversion and forgiving (as a process of change) may be regarded as examples.

Two and possibly three different religious coping methods can be discerned in the responses of the religious leaders. The tendency to feel more or less at home in a religious community may be regarded a sign of ‘preservation’. It is likely that the legal and social professionals regard all religious coping as something ‘clinging to traditions and the past’. However, religious leaders redefining the ritual of deliverance as a form of ‘religious coping’ may contain more dynamic components. Firstly, purification is likely to occur (‘reconstruction’). Secondly, and more importantly, the VHTs possibly adopt new meanings and identities during the deliverance process, including a change of the self with respect to their relationship with and attitude toward the sacred and to their personal circumstances for which deliverance offers a new answer. This last process of change could include a change toward the Pentecostal convictions in which the self no longer depends on traditional notions of (family/kinship-based) dependencies and instead feels the possibility of individual personal development (‘re-creation’).

Individualistic and collectivist approaches

One major difference between the perceptions of the social and legal professionals and the perceptions of the religious leaders pertains to the expectation that VHTs will profit from participating in a religious community. This religious, Pentecostal community is seen as providing social and material support, as well as a connection with religious practices. It is also seen as the ultimate passage to new development, i.e. rituals of deliverance. This, however, does not necessarily imply that VHTs experience a warm and unproblematic welcome within the religious communities; they are received critically, often as sinners, who should change their life course. The interview series in the second subsample shows that the religious communities are seen to provide new social support to VHTs; yet, we must allow for the possibility as some scholars also have been pointing at, that these communities can exert huge claims on the lives of VHTs, as they indeed can do on all of their members (Dijk, Citation2002b; Kamp, Citation2011).

The social and legal professionals reproduce a more individualist approach to social life, ultimately highlighting the possibilities of psychological treatment, such as psychotherapy, to cope with traumatic experiences. On the other hand, the religious leaders, as well as the VHTs themselves, tend to emphasize a more collectivist approach to social life, including a cosmology with ‘a routinized piety toward authority and its symbols’ (Douglas, 1970, p. 87). The results of the current study illustrate how social and legal professionals are more likely to underestimate the relevance of the religious and cultural community for VHTs. Terms such as ‘superstition’ (among social and legal professionals) show a sharp contrast with ‘feeling at ease’ in the Pentecostal religious community.

Limitations of the current study

The current results serve as a point of departure for further research, offering new hypotheses. One limitation of the present study is that the perceptions of care providers on how to relate to VHTs are exclusively based on experiences of those VHTs who have come into contact with legal and care professionals and with religious leaders. It is possible that a substantial group remains out of sight, either because they remain totally captured in the situation of exploitation, do not possess the required legal papers, or have found an escape without the help of officials. Moreover, the groups of VHTs that the professionals and religious leaders related to may have only partially overlapped.

Toward collaborative understanding?

The perceptions of the religious leaders in the African migrant churches on care for West African VHTs resemble patterns of mental health care delivery in Pentecostal churches in Ghana, as has been described by Asamoah et al. (2014). These researchers describe how Pentecostal clergy in Ghana reflect on the role of their churches in mental health care delivery. The Ghanaian Pentecostal clergy members emphasize three roles of the church in mental health care delivery: exorcism, social support and health education. The first two points clearly appear in the results of the current study, whereas the third point, health education, does not turn up at all. Asamoah et al. (Citation2014) recommend for the Ghanaian situation that collaborative understanding should be fostered, e.g. by education, both for clergy members and for formal care workers. A similar advice is clearly warranted for the Dutch situation. Furthermore, the Dutch social and legal professional may take notice of the importance of a collectivist approach in African migrant communities. In turn, the leaders of African migrant churches may learn about the relevance of specialized treatment and psychotherapy for traumatized VHTs. Both groups could consider the ‘intersecting ambiguities’ about the West African VHTs (‘pride’/‘mistrust’).

In the United Kingdom, Leavey et al. (Citation2017) argue that partnership between faith-based organizations and health services may benefit from attention to mutual understanding and cultural sensitivity. Members of African-led religious communities may help to explain health workers about idioms of mental distress among migrants from Africa and may assist patients to overcome stigma and engage with treatment and care (Leavey et al., Citation2017). Mutual understanding can also be facilitated by addressing the differences with respect to explanatory models of disease (Kleinman, Citation1988). For example, Leavey (Citation2010) describes how spiritual and supernatural models, on the one hand, and biomedical and psychosocial models, on the other hand, do not need to be mutually exclusive, but sometimes can be substitutive and contingent. By and large, these advices are also compatible with the recommendations of the Position Statement on Spirituality and Religion in Psychiatry by the World Psychiatric Association (Moreira-Almeida et al., Citation2016). One of these recommendations encourages psychiatrists to collaborate with leaders/members of faith communities, chaplains and pastoral workers, in support of the well-being of their patients.

Conclusion

Professional experiences with regard to care for West African victims point at a limited awareness of the significance of the religious and cultural community. In the current study, this religious and cultural community is represented by African Pentecostal notions and practices, in so far as these are dominant in contemporary West Africa and are relevant to the persons trafficked from there. The lack of mutual knowledge between Western, secular professionals and religious clergy members may impair collaboration between these two sources of care. In the worst case, this impairment is aggravated by stereotypes in the form of reciprocal imaging and ‘othering’. Collaboration may improve by providing more education among professionals about religious diversity in West Africa, and about the ways in which this has an impact on the religious frames of reference among VHTs in Europe, including the main components of African Pentecostalism. Research, education, and mutual exchange may contribute to more sensitivity among both sources of care to religious and secular complexity in 21st-century societies within a globalizing world.

Notes

1 As this has been, and still is, a vast terrain of study in Cultural Anthropology, these authors just represent a limited number of lines of interest and exploration, in no way to be considered fully representative of the many strands of research that this field harbors.

2 The FairWork Foundation, a nonprofit organization that directly supports victims of labor exploitation in the Netherlands, initiated the current study after signaling a knowledge gap with respect to aid to West African victims of human trafficking; a knowledge gap that specifically related to the significance of religious identities, experiences and practices both on the part of the professional care providers and on the level of the religious communities within the West African migrant population.

References

- Adogame, A. (2013). The African Christian diaspora. New currents and emerging trends in world Christianity. Bloomsbury Academic.

- Anderson, A. H. (2014). An introduction into Pentecostalism: Global charismatic Christianity (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Asamoah, M. K., Osafo, J., & Agyapong, I. (2014). The role of Pentecostal clergy in mental health-care delivery in Ghana. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 17(6), 601–614. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10/1080/13674676.2013.871628.

- Assmann, J. (2008). Translating gods: Religion as a factor of cultural (un)translatability. In H. de Vries (Ed.), Religion: Beyond a concept (pp. 139–149). Fordham University Press.

- Baarda, C. S. (2016). Human trafficking for sexual exploitation from Nigeria into Western Europe: The role of voodoo rituals in the functioning of a criminal network. European Journal of Criminology, 13(2), 257–273. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1477370815617188

- Berger, P. (1999). The de-secularization of the modern world: Resurgent religion and world politics. Eerdmans.

- Boeije, H. (2005). Analyseren in kwalitatief onderzoek: denken en doen. Boom onderwijs.

- Braam, A. W., Schrier, A. C., Tuinebreijer, W. C., Beekman, A. T. F., Dekker, J. J. M., & de Wit, M. A. S. (2010). Religious coping and depression in multicultural Amsterdam: a comparison between native Dutch citizens and Turkish, Moroccan and Surinamese/Antillean migrants. Journal of Affective Disorders, 125(1–3), 269–278. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10/1016/j.jad.2010.02.116

- Burchardt, M., Wohlrab-Sahr, M., & Middell, M. (Eds.). (2015). Multiple secularities beyond the west: Religion and modernity in the global age. De Gruyter.

- Cartledge, M. J., Dunlop, A. L. B., Buckingham, H., & Bremner, S. (2019). Megachurches and social engagement. Public theology in practice. Brill.

- Cole, J., & Groes, C. (Eds.). (2016). Affective circuits. African migrations to Europe and the pursuit of social regeneration. Chicago University Press.

- Csordas, T. J. (1994). The sacred self. A cultural phenomenology of charismatic healing. University of California Press.

- Dijk, R. van. (1997). From camp to encompassment: Discourses of transsubjectivity in the Ghanaian pentecostal diaspora. Journal of Religion in Africa, 27(2), 135–169. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10/2307/1581683

- Dijk, R. van. (2001). Time and transcultural technologies of the self in the Ghanaian Pentecostal diaspora. In A. Corten & R. Marshall-Fratani (Eds.), Between Babel and Pentecost. Transnational Pentecostalism in Africa and Latin America (216-234). Hurst Publishers/Indiana University Press.

- Dijk, R. van. (2002a). The soul is the stranger. Ghanaian Pentecostalism and the diasporic contestation of ‘flow’ and ‘individuality. Culture and Religion, 3(1), 49–67. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10/1080/01438300208567182

- Dijk, R. van. (2002b). Religion, reciprocity and restructuring family responsibility in the Ghanaian Pentecostal Diaspora. In D. Bryceson & U. Vuorella (Eds.), The transnational family. New European frontiers and global networks (173-196). Berg.

- Dijk, R. van. (2004). “Beyond the rivers of Ethiopia”: Pentecostal pan-Africanism and Ghanaian identities in the transnational domain. In W. M. J. van Binsbergen & R. A. van Dijk (Eds.), Situating globality: African agency in the appropriation of global culture (163-189). Brill.

- Dilger, H., Bochow, A., Burchardt, M., & Wilhelm-Solomon, M. (Eds.). (2020). Affective trajectories. Religion and emotion in African city-scapes. Duke University Press.

- Douglas, M. (1970/2002). Natural symbols: Explorations in cosmology. Routledge.

- Faimau, G., & Lesitaokana, O. (Eds.). (2018). New media and the mediatisation of religion. An African perspective. Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

- Gemmeke, A. (2013). West African migration to and through The Netherlands: Interactions with perceptions and policies. Urban Anthropology and Studies of Cultural Systems and World Economic Development, 42(1–2), 57–94.

- Gifford, P. (2004). Ghana's new Christianity: Pentecostalism in a globalizing African economy. Indiana University Press.

- Gifford, P. (2016). Healing in African Pentecostalism: The “victorious living” of David Oyedepo. In C. Gunther Brown (Ed.), Global Pentecostal and charismatic healing (pp. 251–266). Oxford University Press.

- Habermas, J. (2003). Between naturalism and religion: Philosophical essays. Polity Press.

- Habermas, J. (2004). Faith and knowledge. In J. Habermas (Ed.), The future of human nature (101-115). Polity Press.

- Hunt, S., & Lightly, N. (2001). The British black Pentecostal `revival`: Identity and belief in the `new` Nigerian churches. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 24(1), 104–124. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10/1080/014198701750052523

- Joas, H. (2008). Post-secular religion? On Jürgen Habermas. In H. Joas (Ed.), Do we need religion? On the experience of self-transcendence (105-111). Paradigm Publishers.

- Kalu, O. (2008). African Pentecostalism, An introduction. Oxford University Press.

- Kamp, L. van de. (2011). Violent conversion. Brazilian Pentecostalism and urban womenin Mozambique [PhD thesis]. VU Amsterdam.

- Kate, L. ten (2012). Re-opening the question of religion: Dis-enclosure of religion and modernity in the philosophy of Jean-Luc Nancy. In A. Alexandrova, I. Devisch, L. Ten Kate, & A. van Rooden (Eds.), Re-treating religion: Deconstructing Christianity with Jean-Luc Nancy (pp. 22–40). Fordham University Press.

- Kleinman, A. (1988). The illness narratives: Suffering, healing, and the human condition. Basic Books.

- Knibbe, K. E. (2010). Geographies of conversion: Focusing on the spatial practices of Nigerian Pentecostalism. Pentecostudies, 9(2), 175–194. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10/1558/ptcs.v9.i2.8881

- Koenig, H. G., King, D. E., & Benner Carson, V. (2012). Handbook of religion and health. Oxford University Press.

- Krause, K., & Van Dijk, R. (2016). Hodological care among Ghanaian Pentecostals: De-diasporization and belonging in transnational religious networks. Diaspora, 19(1), 97–115.

- Kwabena Asamoah-Gyadu, J. (2014). Pentecostalism and the transformation of the African Christian landscape. In M. Lindhardt (Ed.), Pentecostalism in Africa: Presence and impact of pneumatic Christianity in Postcolonial Societies (Global Pentecostal and Charismatic Studies) (Vol. 15, pp. 100–114). Brill.

- Leavey, G. (2010). The appreciation of the spiritual in mental illness: a qualitative study of beliefs among clergy in the UK. Transcultural Psychiatry, 47(4), 571–590. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10/1177/1363461510383200

- Leavey, G., Loewenthal, K., & King, M. (2017). Pastoral care of mental illness and the accommodation of African Christian beliefs and practices by UK clergy. Transcultural Psychiatry, 54(1), 86–106. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10/1177/1363461516689016

- Leutloff-Grandits, C., Peleikis, A., & Thelen, T. (Eds.). (2009). Social security in religious networks. Anthropological perspectives on new risks and ambivalences. Berghahn.

- Lindhardt, M. (2010). “If you are saved you cannot forget your parents”. Agency, power, and social repositioning in Tanzanian born-again Christianity. Journal of Religion in Africa, 40(3), 240–272. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10/1163/157006610X530330

- Lindhardt, M. (Ed.) (2011). Practicing the faith: The ritual life of Pentecostal-Charismatic Christians. Berghahn.

- Lindhardt, M. (Ed.) (2015). Pentecostalism in Africa: Presence and impact of pneumatic Christianity in postcolonial societies. Brill.

- Maltese, G., Bachmann, J., & Rakow, K. (2019). Negotiating Evangelicalism and Pentecostalism: Global entanglements, identity politics and the future of Pentecostal studies. PentecoStudies: An Interdisciplinary Journal for Research on the Pentecostal and Charismatic Movements, 18(1), 7–19. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10/1558/pent.38778.

- Meyer, B. (1998). Make a complete break with the past.' Memory and post-colonial modernity in Ghanaian Pentecostalist discourse. Journal of Religion in Africa, 28(3), 316–349.

- Moreira-Almeida, A., Sharma, A., Janse van Rensburg, B., Verhagen, P. J., & Cook, C. C. H. (2016). WPA position statement on spirituality and religion in psychiatry. World Psychiatry : official Journal of the World Psychiatric Association (Wpa)), 15(1), 87–88. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10/1002/wps.20304

- Nationaal Rapporteur Mensenhandel en Seksueel Geweld tegen Kinderen. (2015). Mensenhandel in en uit beeld. Update cijfers mogelijke slachtoffers 2010–2014. Nationaal Rapporteur.

- Pargament, K. I. (1997). The psychology of religion and coping: Theory, research, practice. The Guilford Press.

- Pieper, J., & Van Uden, M. (2005). Religion and coping in mental health care. Rodopi.

- Taylor, C. (2003). Varieties of religion today. William James revisited. Harvard University Press.

- Taylor, C. (2007). A secular age. Belknap Press/Harvard University Press.

- Tepper, L., Rogers, S. A., Coleman, E. M., & Malony, H. N. (2001). The prevalence of religious coping among persons with persistent mental illness. Psychiatric Services (Washington, D.C.), 52(5), 660–665. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10/1176/appi.ps.52.5.660

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). (2014). Global report on trafficking in persons 2014. United Nations Publication.

- Vattimo, G. (2002). After Christianity. Columbia University Press.

- Vries, H. de (2008). Introduction: Why still ‘religion’? In H. de Vries (Ed.), Religion: Beyond a concept (pp. 1–100). Fordham University Press.

- Währisch-Oblau, C. (2016). Material salvation: Healing, deliverance, and “Breakthrough” in African migrant churches in Germany. In C. Gunther Brown (Ed.), Global Pentecostal and charismatic healing (pp. 61–80). Oxford University Press.

- Werbner, R. (2015). Divination’s Grasp. African Encounters with the Almost Said. Indiana University Press.