Abstract

Although aging and migration are major global demographic trends, little attention has been given to the health and well-being of immigrants who migrate later-in-life. Drawing on the social convoy perspective, we examine the social impact of late-life migration and explore patterns of human service provision among late-life immigrants in a midwestern U.S. region. Using qualitative data (N = 71)—in-depth interviews and focus group discussions— from diverse key informants, including late-life immigrants and local human service providers, our study attempts to expand the knowledge base on late-life migration and garner community-generated solutions for the well-being of this unique population.

Late-life migration is a burgeoning phenomenon worldwide, fueled largely by higher life expectancy, expanded legal pathways for family reunification and increased refugee admissions (Montayre et al., Citation2017). In the US, there are 4.6 million foreign-born individuals older than 65 (15% of the total foreign-born population), a number expected to exceed 16 million by 2050 (Treas & Batalova, Citation2007). Despite this looming population increase, gerontological research and program development in the US have focused, with a few exceptions (Heikkinen & Lumme-Sandt, Citation2013), on the native-born population (Liou & Shenk, Citation2016) or early-life migrants (Karl & Torres, Citation2016). Similarly, the migration literature has relatively poor coverage of late-life migration issues (Walters, Citation2002). In general, this literature has explored return migration—returning to one’s country of origin in old age (Conway & Houtenville, Citation2003)—or amenity migration—relocating internationally for a better postretirement life (Casado-Diaz et al., Citation2004). Studies investigating late-life migration identify several motives for moving: desire for kinship, financial problems, poor health, death or institutionalization of a spouse, and amenity reasons (Choi, Citation1996; Walters, Citation2002). Older immigrants moving for amenity reasons had higher-than-average incomes and lived for fewer than 15 years in their original homes; those moving for kinship were more likely to be nonwhite and live with adult children; and those moving for health reasons tended to be female, have increasing disability, live alone, and have comparatively lower levels of income and education (De Jong et al., Citation1995). There is, however, a paucity of literature on late-life migration for other reasons, such as mass, forced, or impelled migration.

Existing work has been limited to the plight of younger migrants in resettlement spaces, overlooking older persons who migrate later in life, either willfully or by default (Litwin & Leshem, Citation2008). Additionally, literature on late-life immigrants, particularly those from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds, is sparse and fragmented. Late-life migration in mass or forced displacement contexts is a crucial area of scientific inquiry because people migrating later-in-life face “double jeopardy,” confronting challenges of both migration and old age in new places of resettlement (Litwin & Leshem, Citation2008, p. 904).

Further, late-life migration is a crucial factor in local and economic development as it increases the geographic concentration of the older population (Walters, Citation2002). Of particular interest, is the social impact of late-life migration on the well-being of older immigrants in their new environments. Because migration is a critical component in the aging of state and regional populations (Walters, Citation2002), a nuanced understanding of age-based experiences of late-life migration, particularly the compounding challenges of migration and aging, is critical to expanding our conceptualization of aging and planning appropriate care for increasingly diverse older immigrants (Wilmoth, Citation2012). As the consequences of late-life migration are often more pronounced at the local and regional levels, understanding late-life migration patterns and developments in local contexts can enhance the pragmatic utility and overall well-being of local populations (Walters, Citation2002). In this study, we focus on late-life migration issues in the Midwestern US region, among immigrants and refugees from non-Western countries with culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds. We use the broader terms “late-life immigrants” and “older immigrants” to cover different migrant groups and begin with an overview of late-life migration; individual, community, and structural challenges; and the impact of late-life migration on the well-being of this population.

Late-life migration in the US

Although some foreign-born older adults in the US emigrated from Europe as either children or young adults, recent immigrants from Asia and Latin America more often arrive later- in-life (Gurak & Kritz, Citation2010). In addition to family-based immigration and refugee admissions, many older persons also visit the US temporarily to help their adult children with childcare responsibilities, share life benefits, or receive care from their family (Treas & Mazumdar, Citation2002). Unlike “returning migrants,” who bring lifelong earnings when they return to their original countries (Wong et al., Citation2007), or “amenity migrants,” who bring pension and social security income from their original countries (Warnes, Citation2001), late-life immigrants with mass migration or forced migration backgrounds not only lack financial support from their original homes but also face limited financial opportunities and fewer safety-net benefits provided by US welfare programs (Litwin & Leshem, Citation2008).

Late-life immigrants from non-Western countries typically have limited education, less English proficiency, exhibit lower socioeconomic status (SES), and are more likely to live with kin (Gurak & Kritz, Citation2010). Because their work histories do not qualify them for social security and employment pensions, late-life immigrants largely depend on their families (Van Hook, Citation2000). Although late-life immigrants who come to the US as refugees and asylees are eligible for welfare benefits, such as Supplemental Security Income (SSI), Medicaid, food stamps, and Temporary Assistance for Needy Families for the first 7 years, as well as Refugee Cash Assistance for 8 months, others do not qualify for these benefits until they become US citizens (Fix & Haskins, Citation2002). In fact, immigrant and refugee enrollment rates in public welfare benefits, which were already low, have significantly declined (despite eligibility) after the public-charge rule imposed by the Trump administration, due to persistent fear of adverse impacts on future legal status in the US (Capps et al., Citation2020). Additionally, late-life immigrants experience loss of social networks, fewer opportunities for socialization, changes family status, language and financial barriers, and challenges accessing health and other critical human services as they age (Tan, Citation2011).

Late-life immigrants and well-being

Compared with native-born adults, late-life immigrants experience higher levels of acculturative stress, depression (Wrobel et al., Citation2009), and loneliness (Guo et al., Citation2019;; Wu & Penning, Citation2015), a phenomenon whose causes and consequences are understudied (Syed et al., Citation2017). Cultural stigmas around mental health (Bhattacharya & Shibusawa, Citation2009), insufficient health insurance (Villa et al., Citation2012), and frustrations stemming from language barriers contribute to underutilization of health and human services, which further increases health risks and disparities with age (Ciobanu et al., Citation2017). Many late-life immigrants come from interdependent collective cultures with filial expectations. When adult children do not provide instrumental support, conflict and feelings of abandonment and shame can arise (Bhattacharya & Shibusawa, Citation2009). Still, late-life immigrants keep these feelings silent to avoid being a burden, leading to higher levels of depression and lower health outcomes (Ciobanu et al., Citation2017). In tandem, older immigrants’ social, emotional, and economic reliance on their adult children can lead to feelings of powerlessness (Liou & Shenk, Citation2016), diminish decision-making power (Da & Garcia, Citation2015), and inhibit successful integration into the host country (Treas & Mazumdar, Citation2002). Especially among older immigrant women (Liou & Shenk, Citation2016), who tend to shoulder the caregiving burden (Vega, Citation2017), perceived obligations to provide childcare and domestic help (Da & Garcia, Citation2015) can inhibit independence, further limited by language barriers—which can hamper engagement in religious, cultural, and community activities (Treas & Mazumdar, Citation2002)—and by the lack of a driver’s license and limited public transportation, (Dabelko-Schoeny et al., Citation2021).

The age-friendly cities and communities movement promoted by the World Health Organization (Citation2018) focuses on addressing social isolation and loneliness at the community level, as one of eight domains for age-friendly cities. Accordingly, finding community support allows late-life immigrants to adjust to the new culture while also maintaining their cultural norms (Bhattacharya & Shibusawa, Citation2009; Liou & Shenk, Citation2016; Wrobel et al., Citation2009). Using their native language and forming active relationships beyond the kin-circle can reduce loneliness and promote belonging (De Jong Gierveld et al., Citation2015). These cultural and social ties protect late-life immigrants’ well-being, despite the disruptions caused by migration and relocation (Meeks, Citation2020). However, opportunities for community engagement and peer support in resettlement spaces are often limited. Scholars have continually emphasized the need for age-friendly initiatives to respond to these unique social support needs of diverse older immigrants (Syed et al., Citation2017). Underdeveloped social networks, dependence on the kin circle, transportation and language barriers, and increasing social isolation limit engagement opportunities (Dabelko-Schoeny et al., Citation2021). However, community-based organizations can help older immigrants decrease loneliness, build relationships, and develop their community pride through programs that promote engagement (e.g., volunteering; Morrow-Howell et al., Citation2015) and celebrate cultural activities (e.g., trips to a theater, garden, or art event; Cordero-Guzmán, Citation2005). These organizations allow immigrants to share wisdom and advice, feel worthwhile, and receive support (Liou & Shenk, Citation2016). Failing to acknowledge social, cultural, linguistic, and structural barriers to engagement may exclude diverse ethnic populations (Parekh et al., Citation2018). Moreover, service systems that are not equipped to meet the diverse cultural needs and care expectations of this unique population have far-reaching implications for aging and aging care experiences (Meeks, Citation2020).

Our study

We explored the impact of late-life migration on the well-being of older immigrants by: (a) examining barriers to and facilitators of sociocultural adaptation and (b) exploring patterns of human services provision, to expand our understanding of how societies care for late-life immigrants. Our qualitative study is part of a larger mixed-methods research project that used a community-based participatory research (CBPR) approach to assess the human services landscape in the Midwestern US (Maleku et al., Citation2020). In this study, we used immigrant-refugee perspectives from diverse age groups, including late-life immigrants and local service providers, to uncover sustainable, community-based solutions. Community and provider perspectives garnered a nuanced understanding of late-life migration challenges and local human services provision and helped elucidate convergent and divergent findings.

The Midwestern US, the setting of our study, is ranked among the nation’s top five refugee resettlement sites (Refugee Processing Center, Citation2020). This region hosts the largest Bhutanese and second-largest Somali refugee populations in the country. Older immigrants, who are mostly late-life immigrants in this region, experience transportation, human services access, and social integration challenges (Dabelko-Schoeny et al., Citation2021; Maleku et al., Citation2018). Our study focuses on late-life migration in mass migration and forced migration contexts, particularly humanitarian migrants—people requesting asylum, refugees, temporary protected-status holders, and noncitizen victims of crime for whom special visas are reserved—from non-Western countries with diverse cultural and linguistic backgrounds.

Conceptual framework: Social convoy perspective

Migration’s disruptive role in social networks and social support structures for immigrants, especially refugees, has profound impacts on their well-being (Wachter et al., Citation2021). However, predominant acculturation theories overlook the nature of social relationships and their influence on well‐being as a structural experience (Viruell-Fuentes, Citation2007) and disregard the crucial role of social relations in aging across the migration trajectory (Antonucci et al., Citation2014). Thus, we used the social convoy perspective as our guiding framework.

A convoy is a protective, dynamic network of close social ties that provides personal, familial, cultural, and professional linkages for an individual. Convoy structure (size and composition) is crucial, as are the personal (age, gender, race) and contextual (marital status, immigration) characteristics that form the basis of relationship and support quality (Sherman et al., Citation2015). The social convoy model conceptualizes the support systems that move with individuals and explains age-related continuity and change in the size and composition of individuals’ social networks across the life course (Antonucci et al., Citation2014). However, the closeness of these relationships depends on the frequency, function, and quality of interactions, with significant implications for older adults’ health and well-being (Antonucci et al., Citation2014), including the effect of migration stressors (Gentry, Citation2010). As late-life immigrants migrate to new spaces, their convoys are uprooted and some ties are dissolved, creating the “broken convoy” effect (Park et al., Citation2015). Migration disrupts convoy size, composition, and social support availability, especially when an individual has a limited or nonexistent convoy in the new space (Sherman et al., Citation2015). This loss of social connections at every convoy layer poses significant risks to postmigration health and well-being. While social support is crucial to overcoming migration stressors, such as discrimination, social stress, depression, or anxiety (Meeks, Citation2020), the absence of a protective social network compounds the risk factors associated with migration (Sherman et al., Citation2015). Faced with the demands of constructing new relationships in the absence of crucial activities such as employment or parenting young children, social isolation can prompt depression, anxiety, biological risk, and long-term effects on chronic health conditions during resettlement (Gruenewald et al., Citation2012).

Method

Research design

We collected qualitative data to explore the barriers and facilitators of sociocultural adaptation among late-life immigrants, then examined patterns of human services provision based on community and provider perspectives. Guided by the transformative lens of CBPR, key informants from immigrant-refugee communities, along with representatives from human services organizations (HSOs) including community-based ethnic organizations (CBEO), were involved in the community advisory committee (CAC) for the study. CBEOs were immigrant-led organizations, provided culturally responsive services, had a larger reach into immigrant-refugee communities, and brought an in-depth understanding of lived experiences. The CAC provided feedback and expertise throughout the research process, including study conceptualization, data collection, data analysis, and dissemination of study findings. Data were collected between August through December 2017. Institutional Review Board approval was obtained at the study site.

Data collection and study sample

The participants for this study (N = 71; ) included a subsample of human service providers (HSPs; n = 23) who participated in in-depth interviews (IDIs) and key informants (n = 48) from immigrant-refugee communities who participated in focus group discussions (FGDs). The HSPs represented local HSOs, which included public, nonprofit, for-profit, and government organizations. These HSPs had initially responded to a web-based survey exploring human services and had expressed their interest in optional 60-minute IDIs for this study (Maleku et al., Citation2020). Through semi-structured IDIs, HSPs were asked to describe immigrant-refugee issues, the most affected demographic subgroups, culturally responsive services, and the local human services environment. Given the recurring issue of late-life migration that needed exploration in its own right, unscripted prompts were used to elaborate on specific issues faced by late-life immigrants, available services, and HSPs’ experiences working with this population.

Table 1. Demographic Characteristics of Study Participants (N = 71).

The FGD sub-sample included members of immigrant-refugee communities from diverse age groups, ranging from ages 18 to 66 (M = 41.93, SD = 13.5). FGD participants represented 16 nationalities: Bhutanese, Kenyan, Rwandese, Somali, Ethiopian, Iraqi, Mexican, Venezuelan, Colombian, Sudanese, Eritrean, Liberian, Korean, Filipino, Thai, and Japanese. We conducted six FGDs, each spanning 90 minutes, in five languages: English, Arabic, Nepali, Kiswahili, and Spanish. Researchers in the study team fluent in English, Nepali and Kiswahili conducted these FGDs. We hired bilingual interpreters, recommended by the advisory committee, for the Arabic and Spanish FGDs. The FGDs gathered direct lived experiences of late-life immigrants and key informants from immigrant-refugee communities, who were knowledgeable about late-life migration issues affecting their communities. A structured focus group guide and unscripted prompts were used to discuss specific issues related to late-life immigrants. The CAC assisted in recruiting five initial seed FGD participants. Then, respondent-driven sampling was used to recruit members of the seeds’ social networks, tapping into the informal community networks to gather a sample of 48 participants.

Venues most convenient to study participants were used for data collection, including HSOs, local libraries, local community spaces, and the study site. Each study participant received an incentive for their participation (gift cards worth $25 for IDIs and $20 for FGDs). The IDIs and FGDs were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. FGDs conducted in other languages (Nepali, Arabic, Spanish) were first transcribed in respective languages and then translated into English by an external transcription and translation service. A two-person research team took general observatory field notes. When interpreters were used in the FGDs, they were engaged in debriefing meetings as a cross-language strategy to review findings and discuss their experiences (Temple & Edwards, Citation2002). The recognition of interpreters as key informants helped mitigate the limitations of word-by-word translation, where cultural expressions often go unnoticed. These discussions allowed for reflexivity and helped the researchers maintain a transparent audit trail of observations and methodological decisions, thus strengthening the rigor of cross-language qualitative research (Temple & Edwards, Citation2002).

Data analysis

We first used the rapid and rigorous qualitative data analysis (RADaR) technique—an individual and team-based approach to coding and qualitative data analysis—to develop data reduction tables in Excel—beneficial in streamlining qualitative data, often from multiple sources (Watkins, Citation2017). The tables, which included multiple rows and columns with texts from IDI and FGD transcripts, formed the basis for coding and analysis. We followed five steps of thematic analysis (Nowell et al., Citation2017): data triangulation with field notes and reflection; generation of initial thematic codes through line-by-line coding; generation of thematic connections based on relationships between codes, frequencies, and meaning across codes; review of themes and interrelated subthemes, testing for referential adequacy; and reevaluation of data analysis by all authors to generate consensus. To maintain methodological rigor, the first and second authors coded the data independently. We ran kappa analysis (Cohen’s k) to determine the level of intercoder agreement (McHugh, Citation2012); results determined substantial agreement in data coding and analysis (k = .692, p = .001). All authors then reevaluated the data analysis, unanimously agreed on the themes, and finalized the translation of themes table ().

Table 2. Translation of Themes.

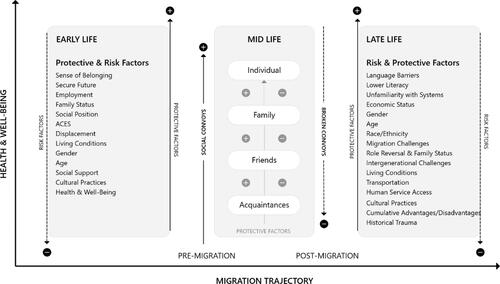

We generated a substantive schema based on data analysis illustrating the level of late-life immigrant well-being based on the presence or absence of risk and protective factors mediated by social convoys, throughout their migration trajectory. In places of resettlement, health and well-being in later-life increases in the presence of protective social convoy and decreases when social convoys are broken, presenting significant risk to well-being ().

Results

We describe the five overarching themes that emerged from data analysis with representative quotes from study participants.

Theme 1: Cultural context of aging

The cultural views of what constitutes older age in non-Western countries vary from aging parameters in the US, including the benefits threshold of 65. These cultural values associated with age are often internalized by individuals and facilitate socioemotional aging processes. Participants emphasized the unique chronology of aging among late-life immigrants, highlighting cross-cultural differences in the social construction of aging, and how the experiences of immigrants who arrive in their 40s and 50s are parallel with native-born in their 60s:

We have a population that comes here already at old age—in their 40s and 50s. You don’t think of it as old age, but when you come to the country at that age, it’s so much more difficult to integrate because you just don’t have time to move from A to B. We will see people soon reaching their 60s who came here later-in-life and didn’t have a chance to learn English, or understand the systems. Service providers might not look at them as those who have barriers. Yet they have [barriers] because they moved after they became older and are more vulnerable. (HSP IDI)

We’re dealing with a much younger, older population in the Latino community than other segments. We have grandparents who have stayed and no longer going back to their country, their kids have kids, so now they’re taking care, and helping. We could have a senior at late 40s, early 50s. They’re in the same situation as a 60-year-old here. They don’t know anybody, not currently employed and lonely. (HSP IDI)

Further, cultural mismatch in the definition of older age contributes to gaps in programs and services that are often not responsive to cultural views of aging. Participants emphasized the consequent need for tailored services for late-life immigrant women who might not necessarily fall under the parameters of older group in the US:

There aren’t any services for women in their 40s and 50s. Although women in their 40s and 50s are not considered older in the US, they are older in different cultures. There’s nothing in the community for this group. (Bhutanese FGD)

Theme 2: Late-life migration challenges in new spaces

For late-life immigrants, migration challenges are compounded by their age and migration stressors in a new space. Participants corroborated the individual, environmental, and structural challenges encountered by late-life immigrants. Specific challenges associated with language, transportation barriers, the built environment, and lack of legal literacy affected late-life immigrants’ well-being. Findings corroborate linguistic isolation issues, whereby limited English proficiency dramatically hindered integration into new spaces. Participants also discussed challenges with transportation and how older immigrants’ reliance on their children caused them to be housebound, increasing social isolation and inhibiting access to needed services:

The older generation definitely suffers more. There are shackles of hurdles, and problems become very difficult. (African FGD)

Most of our population consists of older people, and about 95% to 97% of them are [not literate]. They don’t even know how to read our native language. Learning English at an older age is nearly impossible. This greatly limits their ability to do anything, including passing the naturalization tests. (Bhutanese FGD)

I never learned how to drive. I’ve always relied on my son or daughter. There are many times when your children are busy with their things. So, I cannot go anywhere. Who will take me? What should I do? (Latino FGD)

Low housing quality, pollution, crime, and the shortage of open and green spaces, negatively affected older immigrants’ well-being. Living spaces, particularly for refugees, also need to be spaces for healing that can contribute to their sense of belonging and overall well-being. Late-life immigrants from rural, open areas or those who come from agrarian societies have a deep spiritual relationship with land, green spaces, and nature. Transitioning to cities within closed spaces can, therefore, be very challenging:

One of our members said that she misses sitting on her porch and watching people walk by and watch the world walk by. She said, “Here, everything is in cars. Watching cars is not comparable to sitting outside in the porch being with nature and learning about your feelings. All you see and smell here is traffic.” (HSP IDI)

In addition to the challenges of passing citizenship tests due to lower English language proficiency, challenges in understanding resettlement and citizenship policies and time limits for related services and benefits were discussed. Given these legal literacy challenges, FGD participants also noted the difficulties in seeking legal assistance and older immigrants’ vulnerability to predatory practices, particularly among those who do not have families or other support networks:

In the refugee community, most older adults come through a resettlement agency. For the beginning 8 months, they are all eligible for supplemental income. But after the 8 months post-resettlement, they have a period of 5 years to naturalize and become eligible for benefits. After 7 years, if they don’t become citizens, all the benefits are gone. Older people in our community are not aware of these legal provisions. Also, caseworkers who work with them do not educate the older members properly. So, many members run into problems due to unawareness of legal rules. (Bhutanese FGD)

Some people providing legal services seem to have some sort of agreement with one another. They tell older folks that they can help in getting naturalized citizenship. They say $800 should be given to the doctor and $300 to a lawyer. We had a recent case—the person assisting took $800 from an older lady, but he couldn’t help her get the citizenship. After the request had been rejected three times, the community came together, hunted the guy down, and had him repay. This is only an example. Legal support is crucial—we need to keep a credible attorney at our own community center. Otherwise, our older people will continue to be exploited. (Bhutanese FGD)

Theme 3: Broken convoys and social isolation

The nature of social isolation experienced due to migration stressors by late-life immigrants is different than the social isolation experienced by US-born older adults. As late-life immigrants migrate to new spaces, their convoys are uprooted and some ties are broken; convoys and support exchanges are limited to only family networks, creating gaps in emotional and instrumental support exchanges. This is evident among late-life immigrants, particularly from forced migration contexts and lower SES, who have either underdeveloped or nonexistent social convoys beyond kin. Kin circle dependence may lead to interruption in essential convoys with adverse impact on older immigrants’ social and mental well-being. This dependence further weakens social ties, and isolation originates within family networks. Despite the prevalent understanding of immigrant families as close-knit units, our findings document persistent social isolation, loneliness, and boredom faced by late-life immigrants, even in their extended-family households, in the absence of a broader convoy:

They become isolated because they don’t have that kind of access to community, don’t drive, don’t speak English. It would be great if there were things for them to do in the community, but often they live just within four walls [of their home]. (HSP IDI)

In addition to the absence of a larger social convoy, participants explained how the culture of male dominance in the Bhutanese refugee community can isolate older women, leading to severe mental health issues:

There are big issues among older women in our community. The husband can say, “The son and daughter-in-law are working. Why should you work?” and discourage older women to work outside the house. The women also refrain from work because they need to look after their grandchildren, cook, clean the house. If she goes and talks to her neighbor next door, she fears—what if the neighbor tells my husband tomorrow? So, they just keep things to themselves. And one day, this impatience explodes—may lead to divorce, even suicide. (Bhutanese FGD)

FGD participants from the Asian immigrant group corroborated mental health vulnerabilities among older Asian women, largely due to gaps in social networks. Stigma associated with mental health, lack of health insurance, gaps in culturally adapted treatment, and limited English proficiency prevent older Asians from seeking mental health services. Although it is important to consider the diverse Asian subpopulations, participants highlighted the higher risk of suicide among Asian women:

I worry mostly about [older] women who are not in the workforce, because they don’t have much exposure to anybody else, outside of their family. The Asian community [members] I work with don’t drive and are stuck at home with kids and grandkids. The older Asian women have a very high prevalence of mental health and suicidal ideation. (Asian FGD)

Access to information on available services is a huge problem experienced by immigrant-refugee communities. Although lower literacy levels among late-life immigrants from lower SES contribute to this issue, systematic gaps in outreach from HSOs add to accessibility challenges. Adverse mental health repercussions stem from insufficient access and utilization of community resources that further accelerate mental health issues. Participants emphasized that although English classes, citizenship classes, and health services are available, there are persistent access gaps because older immigrants are generally unaware of these services. Accessibility is further hindered by language, transportation, and fear of service use, ultimately increasing mental health issues:

There are medical services in adequate quantities, but accessibility is a major issue. Most older people in our community don’t know where to go, how to get there. So, they just stay at home. They can’t share their feelings with anyone, and it keeps piling. When they can’t share things, older people reach the tipping point of depression. (Bhutanese FGD)

Cultural norms of elder respect and filial piety are standard practices in non-Western interdependent and collectivist cultures. However, cultural conflicts with US society’s individualist norms undermine older immigrants’ social and economic position in the family and broader society, damaging their social status. Older immigrants are increasingly caregivers for grandchildren, often extending a temporary visit indefinitely to help their adult children. While taking the burden of providing assistance to their adult children, however, they face systematic challenges for their own care due to limited opportunities and ineligibility for safety-net benefits. The prevalence of circular migration patterns, wherein older immigrants live transnational lives in two places, was shared as a common practice:

I’ve noticed that many parents are coming here and staying three, four months, up to a year. Most are staying at home doing babysitting, helping out with their grandkids. (Kenyan FGD)

We’ve seen a lot of the senior folks—parents that are coming to visit their children in this country. And maybe they fall sick, try not to use the ER as a source of care, then they come to the free clinics. Some of them are here for a short stay. We try to make sure that at least they’ll be here long enough for us to coordinate the kind of care they need. (HSP IDI)

Migration can change intergenerational family dynamics and exacerbate the vulnerabilities faced by late-life immigrants. Bhutanese FGD corroborated that although intergenerational challenges stemming from a loss of family status affect older men, older women face increasing vulnerabilities due to diminished family status. The inability to participate in the workforce exposes older women, especially between ages 50 and 65, to domestic abuse and violence. Unable to work and burdened with caregiving responsibilities, older women are also barred from participating in community resources and services. Participants contended that older women, therefore, are disproportionately affected by isolation that affects their mental well-being. These responses affirm the disruptive role of migration in family dynamics, weakened family ties, gender vulnerabilities, and the impact of broken social networks on the mental well-being of late-life immigrants:

The whole family infrastructure that was intact back home is shaken when they come here. The elders were at the top as family authority figures. And now, the kids are pushing them aside and are taking the authority roles. (HSP IDI)

Our older people stay at home—mental torture begins. They cannot speak, can’t respond. They always need help. So, now the grandson talks. Who is superior then? Back home, you have a superior status as the elder in the family, but that status changes. Therefore, older people, especially older males, have reduced morale because of this loss of family status. (Bhutanese FGD)

Women between the ages of 50 and 65 aren’t a working group. They also don’t get SSI benefits. They don’t have Medicaid or Medicare. Since they are not bringing any additional benefits to a family, they’re sort of neglected. (Bhutanese FGD)

Because they don’t have language capacity, they can’t go find a job. So, either they have to babysit to please their kids or they’re subject to domestic violence—her presence in the family has no value, no one values her, but she’s somehow holding the house. Nonworking women ages 50 to 65 have no power in the family because they aren’t bringing money home. (Bhutanese FGD)

Theme 4: Human service provision, access, and utilization

Although older immigrants’ human services access and utilization are primarily limited by lower SES, limited English proficiency, transportation, and laws restricting access to federal programs based on citizenship status, accessible and culturally responsive human services could mitigate these challenges. Participants recommended that these services should consider the cultural views of aging; mitigating barriers of language and interpretation, transportation, and social isolation, and focusing on network-based, healing-centered interventions. Although age-friendly initiatives aim to create inclusivity, participants noted that these initiatives are mostly focused on Western contexts of aging, whereas the needs of older immigrants are often overlooked:

The immigrant seniors, who come here later in life, are the most tortured and abandoned group in our region. There are not any services. If there are, they are not culturally appropriate to these diverse seniors. (HSP IDI)

Definitely services for seniors is a huge need that is not looked at. [The] American population is not the only one that’s aging—we are aging, too! (HSP IDI).

Integrating into new spaces later-in-life is often difficult because of the continual cultural challenges. Individuals often feel powerful bonds and attachments to places if their social relationships are strong. Those relationships are bolstered when individuals share commonalities and a consistent sense of identity and values with others. However, when cultural differences are ignored, older immigrants feel socially excluded. Therefore, targeted programs such as ESL classes that are available, accessible, and acceptable to late-life immigrants can create more opportunities for social engagement. Participants reiterated the need for more culturally responsive mental health services that put culture at the center:

They cannot integrate—you have to have that language; you have to have that culture. So, to bring them at an already older age and then put them with American seniors—it’s just really torturing them. (HSP IDI)

There’s still a lot of holes that I see, especially in terms of mental health services and helping them access these services is very important. Services like ESL classes are good. These give older men and women time to come together and support each other, which helps with their mental health. (Asian FGD)

Navigating bureaucratic hurdles and systemic barriers also discourages older immigrants from utilizing services. Particularly, the service utilization process may be dehumanizing and stressful when HSPs repetitively ask for personal information, which may precipitate anxiety. A Bhutanese FGD participant highlighted how late-life immigrants don’t have this personal information because they had to flee their original homes without these documents. So, in addition to the lack of translation and interpretation services in the social and health care system, the lack of culturally sensitive services that suit refugee needs greatly influences their service utilization:

When they do go to [a] health care facility—they ask our older folks a lot of personal information. They ask about birth dates, addresses. May I have the last four of your social security number? When these questions are asked, our older people stand still. They do not know what to do. In our culture, especially among refugees, birth certificates and birth dates or any other documents are difficult, because many people fled their homes without these documents. (Bhutanese FGD)

Theme 5: Community efforts and proposed solutions

HSPs discussed the current local efforts to address the needs and capacities of late-life immigrants and highlighted the need for culturally responsive responses. These programs ranged from companion programs for retired older adults, which increase socialization and employs their cultural assets, to socialization programs designed to mitigate social isolation and increase engagement. Although one senior companion program was initially not focused on immigrants, an HSP described how it has made an effort to address cultural variations among late-life immigrants via translations into 25 languages:

Programs like senior companion helps them not only financially, but also the sense of worth and an opportunity to give back to other homebound seniors that are lonely and have no family. (HSP IDI)

One immigrant leader noted services focused on “domestic violence and senior abuse” in addition to their “strong family support program that provides services to victims” (HSP IDI). Another HSP discussed the importance of targeted network-based services that provide older immigrants with needed relief from social isolation:

Through our senior support program for late-life migrants, we plan trips to a farm, city hall, taking them grocery shopping. We need more of this. (HSP IDI)

One FGD participant described the use of bicultural workers at her employment to deliver targeted outreach and health-related services through home visits:

We educate older adults on how to take medicine, monitor medications, check blood sugar—in their native language. Going to their homes provides opportunities for education, like what to eat or what not to eat if they are suffering from diabetes, when to call emergency, what is high blood-pressure, etc., in simple, plain language. (Bhutanese FGD)

In light of recent discussions around productive aging and how older adults’ capacities can be best utilized for their health and economic security, it is crucial to consider local, sustainable solutions that support larger efforts toward older immigrant inclusion. FGD participants proposed community solutions and delineated new initiatives, such as intentional use of public spaces and local libraries and tapping into the cultural knowledge of the older immigrants. These intentional efforts would aid in culturally responsive services for older immigrants that could support multiple dimensions of their well-being:

A recreation center near our community has a separate space for seniors. There are many things that are also free. But elders in our community—one, don’t know about it. Second, they will not utilize it because the system is all high-tech and not user-friendly. For our elders, this creates a lot of barriers. If these spaces were used wisely to integrate immigrant seniors, that would be very good. (Bhutanese FGD)

In the community library here, there is one book in Nepali. I took that book home—my dad read it all. If libraries could carry a good selection of books in various languages for our older members who can read, they would use library resources. (Bhutanese FGD)

Most of our elders are not literate in English, but can read Nepali. Every week, they read religious books like “Krishnacharitras and Ramayanas,” but in our local community, there are no places to take them. In our Bhutanese community, religious and spiritual programs, like prayers, yoga, are happening more—but more spiritual practice opportunities need to happen for elders in our community. (Bhutanese FGD)

Religious and spiritual coping—embedded in faith, values, and cultural beliefs—are important coping strategies to manage life challenges, especially among older immigrants. Study participants corroborated the need to provide network-based opportunities for spiritual practice. Further, immigrant-refugee participants from Africa highlighted the untapped potential of engaging older immigrant populations as cultural resources and assets, which would not only engage them in meaningful social roles that would promote their self-esteem and self-worth, but also aid in creating inclusive cultural spaces based on their cultural expertise:

We have a huge population of immigrants who are in their sunset years. We’re talking about old folks, older people, like grandmas, grandpas. We haven’t tapped that resource. Most of them stay home, they grew up in Africa and know [about culture]. If we can tap that as a resource, that can help a lot. [African FGD]

Discussion

Our study is an initial attempt to explore new insights and opportunities relevant to late-life immigrants from non-Western countries with mass and forced migration experiences, using the social convoy perspective. However, two critical areas need further examination: programs and policies that create inclusive spaces to optimally engage the resources of late-life immigrants, and opportunities to expand the discourse on late-life migration in gerontology and migration research. The erosion of social networks and social support loss in a new space is critical in both migration and aging; future studies of social convoy adaptation and stability can provide interesting new insights in migration and gerontological research. In the face of serious events such as the current COVID-19 pandemic, in which living with kin can be risky due to multigenerational living arrangements in close quarters and a greater likelihood of shared family stresses, further work should explore the role of social convoys in accessing health information and services, accessing basic needs such as food and everyday essentials, and navigating preventive behaviors, technology, and isolation. Given the proliferation of social media, the potential of virtual convoys cannot be ignored. Although we did not find a virtual transnational network in our study, future studies should explore the role of virtual convoys, particularly in the COVID-19 context. This might be particularly salient among late-life temporary migrants who live transnational lives.

By applying the social convoy perspective to our study, we have developed a richer understanding of late-life immigrants’ challenges and have proposed solutions for responding to these challenges while building on the strengths of older adults. Our findings are consistent with studies that showed that diversity in convoy composition beyond family was significantly associated with higher health ratings and lower levels of depression among older immigrants (Park et al., Citation2019). Late-life immigrants face significant barriers to age-normed opportunities, like education and employment, that are available to younger adults and foster adaptation. In leaving their home country, older immigrants lose their status in a social network built across their life course; many also lose stature among co-residing family members. Our study corroborated linguistic isolation (Mutchler & Brallier, Citation1999), weak social ties, and loneliness (Wu & Penning, Citation2015) as prevalent issues among late-life immigrants. Although religious participation, ESL classes, and physical activities can foster socialization, participation is limited by older immigrants’ domestic roles and the lack of culturally appropriate services. Although late-life immigrants appreciate better quality of lives in the US compared to their previous lives (Poudel-Tandukar et al., Citation2019), our findings showed that late-life migration factors such as living arrangements, language, transportation, intergenerational relationships, economic status, and more importantly, social networks in new spaces affect older immigrants’ well-being in many ways. Specifically, the absence of diverse convoys beyond the kin circle could accelerate social isolation and mental health issues.

Findings emphasize unique structural vulnerabilities at the intersection of gender and age, wherein older immigrant women fall into multiple categories of disadvantage. Prior studies demonstrated that late-life immigrants who arrive in the US after age 60 are likely to be female, widowed, have limited education, and have multiple functional limitations (Wilmoth, Citation2012). We document that late-life immigrant women face unique barriers to social participation, largely due to persistent economic barriers, language, transportation, and gaps in targeted services. Further, older women from collectivist cultures, particularly in Asian subgroups, tend to report somatic symptoms while suppressing psychological or emotional problems (Lin & Cheung, Citation1999). In addition to deep mental health stigma, lack of health insurance, gaps in culturally adapted treatment, and limited English proficiency make it difficult for older Asians to seek mental health services in a timely manner, which significantly affects mental illness prevalence (Sorkin et al., Citation2011). Although subpopulation differences exist, our findings emphasize mental health vulnerabilities, including risk of suicide, among older Asian women. While this claim may seem crude, prior research has consistently reported higher suicide risk among older Asian women compared to other racial groups (Yang & Wonpat-Borja, Citation2007).

Our study highlights that migration is a stressful life event, frequently precipitated by cumulative traumatic experiences before and after migration. Particularly, older refugees and asylees often arrive with trauma from their home country, which may further complicate their transition (Wrobel et al., Citation2009). This population could benefit from programs centered on mindfulness and healing to create inclusive spaces for overall integration and well-being. Consistent with previous studies among older immigrants, findings show how religious and spiritual coping strategies that are embedded in faith, values, and cultural beliefs could prove beneficial to managing life challenges faced by late-life immigrants (Lee & Chan, Citation2009). Findings corroborate the importance of cultural assets, social roles, and attachments as essential determinants of well-being in later-life (Pillemer et al., Citation2000).

Many late-life immigrants live with extended families to conserve income and assets provide intergenerational support (e.g., childcare), prevent social isolation, and practice the cultural norm of filial piety (Wilmoth, Citation2012). These cultural views of caregiving obligations can also inform culturally responsive and diverse caregiving practices. Despite being viewed as family dependents, late-life immigrants make critical contributions to younger generations’ well-being (Wilmoth, Citation2012) by helping households conserve funds and offering cultural continuity. This is consistent with resource transfer patterns in nonimmigrant or early immigrant families, in which adult children are resource recipients until very late in parent’s life (Davey & Eggebeen, Citation1998). However, aging members of immigrant families seldom have their social and economic support needs adequately met. It becomes particularly challenging when this population also falls through gaps in the safety net provided by federal and state programs (Wilmoth, Citation2012). For example, age-based restrictions (60 years old or older) and length of stay in the US (up to 5 years) for financial support from the US Office of Refugee Resettlement do not necessarily correspond to cultural views of aging and long-term mental health needs due to the loss of social support networks in places of relocation (Frounfelker et al., Citation2020).

Limitations

We discussed overarching patterns of late-life migration based on the data from Midwestern US, limiting the generalizability of findings to other areas. Although our study sample consisted of culturally and linguistically diverse immigrant-refugee subgroups, exploring subgroup differences was beyond the scope of the study. We could not disaggregate the length of US stay among participants, which can alter people’s lived experiences. We could only briefly address late-life immigrants who visit temporarily and live transnational lives. Future studies should explore experiences of this niche group of immigrants in relation to their social convoys in two spaces. Although FGDs captured firsthand experiences of late-life immigrants, some contextual and culturally heterogeneous nuances may have been obfuscated by grouping all participants from different age groups across FGDs. The phenomenon of late-life migration was discussed more in certain FGDs compared to others, which might have created uneven representation. Although qualitative data were recorded, transcribed verbatim, and translated into English, original meanings might have been misinterpreted or lost in translation. Despite these limitations, our study captured the social impact of late-life migration on older immigrants and garnered community-proposed local solutions that can help create an inclusive environment for these new members of US society.

Implications

Meeting the challenges of the growing late-life immigrant population requires multisectoral collaboration among migration and aging researchers, HSOs, CBEOs, and government agencies. Investment in local CBEOs with cultural expertise and a broader reach across cultural subpopulation groups would be a step in the right direction, to mitigate gaps and promote inclusion of these new older adult members in U.S. society. Older immigrants develop feelings of belonging and strong emotional bonds with neighbors when they regularly help others, volunteer, and engage in cultural activities with others of shared backgrounds (Liou & Shenk, Citation2016). Moreover, older immigrants benefit from age-friendly communities that embrace a supportive reciprocal relationship with other immigrants in the community (Neville et al., Citation2018). Scalable local programs such as community trips, mentorship, intergenerational programs, and platforms to share stories and wisdom (Liou & Shenk, Citation2016) should, therefore, be replicated across urban regions. Because social networks with coethnic communities beyond kin are particularly salient, replication of peer-based interventions among older ethnic minority immigrants that include home visiting and social support meetings could improve resilience and reduce loneliness and depressive symptoms, mitigate barriers to social participation, and increase life satisfaction and happiness among socially isolated older adults (Lai et al., Citation2020). The senior companion program is a federally funded volunteer program for low-income older adults that matches volunteers aged 55 or older with other older adults who need care and support. Older volunteers visit their companions on a weekly basis and receive a modest tax-free stipend (Dabelko-Schoeny et al., Citation2021); this program could be extended to diverse late-life immigrants in local regions.

Given the unique challenges faced by late-life immigrant women, there is an urgent need to formulate alternative ways to decrease social isolation and provide opportunities to meaningfully participate in host communities, to forge social ties that will anchor them to their new homes (Banulescu-Bogdan, Citation2020). Thus, interventions that build on their existing skills, such as cooking, crafts, childcare, and gardening, could be connected to economic empowerment alternative programs that help them achieve a greater degree of financial independence and build social ties and resilience (Banulescu-Bogdan, Citation2020). These strategies, however, need to integrate wraparound services that ease transportation barriers and domestic burdens uniquely experienced by older women. Creation of child-friendly social spaces, where older women can bring their grandchildren, could provide spaces of social participation with other coethnic peers and opportunities for intergenerational learning.

Tailored strategies such as volunteering that acknowledge the social, cultural, linguistic, and structural barriers to engagement of diverse ethnic populations should likewise be created to increase community engagement and improve late-life immigrants’ quality of life (Morrow-Howell et al., Citation2015). Assessment of broader social networks to identify risk and protective factors for late-life immigrants’ overall well-being will be a crucial first step for service providers (Frounfelker et al., Citation2020) to support their transition. Policymakers urgently need to intentionally invest in reducing social isolation among late-life immigrants, not only as a path to economic self-sufficiency (Banulescu-Bogdan, Citation2020), but also to meaningfully anchor these new members of U.S. society to their new homes. Late-life immigrant are vessels of cultural capital and catalysts for family values. Therefore, programs that utilize the unique cultural assets of late-life immigrants can not only foster intergenerational cultural learning, but also provide opportunities for local spaces to remain home to a vibrant and diverse aging population. Addressing late-life immigrants as resourceful and valuable members of society will be a step toward achieving the World Health Organization’s (Citation2018) goal of inclusive age-friendly cities and communities.

Acknowledgments

Our sincere thanks to the Community Advisory Committee for all the guidance and feedback received throughout the study. We would also like to thank all the research participants for highlighting the important area of late-life migration and sharing their perspectives that brought this article to fruition.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Antonucci, T. C., Ajrouch, K. J., & Birditt, K. S. (2014). The convoy model: Explaining social relations from a multidisciplinary perspective. The Gerontologist, 54(1), 82–92. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnt118

- Banulescu-Bogdan, N. (2020). Beyond work: Reducing social isolation for refugee women and other marginalized newcomers. Migration Policy Institute.

- Bhattacharya, G., & Shibusawa, T. (2009). Experiences of aging among immigrants from India to the United States: Social work practice in a global context. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 52(5), 445–462. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01634370902983112

- Capps, R., Gelatt, J., & Greenberg, M. (2020). The public-charge rule: Broad impacts, but few will be denied green cards based on actual benefits use. Migration Policy Institute. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/news/public-charge-denial-green-cards-benefits-use

- Casado-Diaz, M. A., Kaiser, C. & Warnes, A. M. (2004). Northern European retired residents in nine southern European areas: Characteristics, motivations and adjustment. Ageing and Society, 24(3), 353–381.

- Choi, N. G. (1996). Older persons who move: Reasons and health consequences. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 15(3), 325–344. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/073346489601500304

- Ciobanu, R. O., Fokkema, T., & Nedelcu, M. (2017). Aging as a migrant: Vulnerabilities, agency and policy implications. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 43(2), 164–181. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2016.1238903

- Conway, K. S. & Houtenville, A. J. (2003). Out with the old, in with the old: A closer look at younger versus older elderly migration. Social Science Quarterly, 84(2), 309–328.

- Cordero-Guzmán, H. R. (2005). Community-based organisations and migration in New York City. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 31(5), 889–909. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13691830500177743

- D., Jong, G. F., Wilmoth, J. M., Angel, J. L., & Cornwell, G. T. (1995). Motives and geographic mobility of very old Americans. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences, 50(6), 395–404.

- Da, W. W., & Garcia, A. (2015). Later life migration: Sociocultural adaptation and changes in quality of life at settlement among recent older Chinese immigrants in Canada. Activities, Adaptation and Aging, 39(3), 214–242.

- Dabelko-Schoeny, H., Maleku, A., Cao, Q., White, K., & Ozbilen, B. (2021). "We want to go, but there are no options": Exploring barriers and facilitators of transportation among diverse older adults. Journal of Transport and Health, 20, 100994. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jth.2020.100994.

- Davey, A., & Eggebeen, D. J. (1998). Patterns of intergenerational exchange and mental health. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 53(2), 86–95.

- De Jong Gierveld, J., Van der Pas, S., & Keating, N. (2015). Loneliness of older immigrant groups in Canada: Effects of ethnic-cultural background. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology, 30(3), 251–268. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10823-015-9265-x

- Fix, M., Haskins, R. (2002). Welfare benefits for non-citizens. Brookings Institute. https://www.brookings.edu/research/welfare-benefits-for-non-citizens/

- Frounfelker, R. L., Mishra, T., Dhesi, S., Gautam, B., Adhikari, N. & Betancourt, T. S. (2020). “We are all under the same roof”: Coping and meaning-making among older Bhutanese with a refugee life experience. Social Science & Medicine, 264, 113311. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113311.

- Gentry, M. (2010). Challenges of elderly immigrants. Human Services Today, 6(2), 1–4.

- Gruenewald, T. L., Karlamangla, A. S., Hu, P., Stein-Merkin, S., Crandall, C., Koretz, B., & Seeman, T. E. (2012). History of socioeconomic disadvantage and allostatic load in later life. Social Science & Medicine, 74(1), 75–83.

- Guo, M., Stensland, M., Li, M., Dong, X., & Tiwari, A. (2019). Is migration at older age associated with poorer psychological well-being? Evidence from Chinese older immigrants in the United States. The Gerontologist, 59(5), 865–876. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gny066

- Gurak, D. T. & Kritz, M. M. (2010). Elderly Asian and Hispanic foreign and native-born arrangements: Accounting for differences. Research on Aging, 32(5), 56–594.

- Heikkinen, S. J. & Lumme-Sandt, K. (2013). Transnational connections of late-LIF migrants. Journal of Aging Studies, 27(2), 198–206.

- Karl, U., & Torres, S. (Eds.). (2016). Aging in contexts of migration. Routledge.

- Lai, D. W. L., Li, J., Ou, X., & Li, C. Y. P. (2020). Effectiveness of a peer-based intervention on loneliness and social isolation of older Chinese immigrants in Canada: A randomized controlled trial. BMC Geriatrics, 20(1), 356. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-020-01756-9

- Lee, O. E. Y. & Chan, K. T. (2009). Religious/spiritual and other adaptive coping strategies among Chinese American Older Immigrants. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 52(5), 517–533.

- Lin, K. M., & Cheung, F. (1999). Mental health issues for Asian Americans. Psychiatric Services, 50(6), 774–780.

- Liou, C. L., & Shenk, D. (2016). A case study of exploring older Chinese Immigrants' Social Support within a Chinese Church Community in the United States. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology, 31(3), 293–309. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10823-016-9292-2

- Litwin, H., & Leshem, E. (2008). Late-life migration, work status, and survival: The case of older immigrants from the Former Soviet Union in Israel. International Migration Review, 42(4), 903–925. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-7379.2008.00152.x

- Maleku, A., Kagotho, N., Baaklini, V., Filburn, C., Karandikar, S., & Mengo, C. (2020). The human service landscape in the midwestern U.S.: A mixed methods study of human service equity among the New American population. The British Journal of Social Work, 50(1), 195–221.

- Maleku, A., Kagotho, N., Karandikar, S., Mengo, C., Freisthler, B., Baaklini, V., & Filbrun, C. (2018). The New Americans Project: Assessing the Human Service Landscape in Central Ohio (Public Report). Columbus, OH: The Ohio State University College of Social Work.

- McHugh, M. L. (2012). Interrater reliability: The kappa statistic. Biochemia Medica, 22(3), 276–282. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.11613/BM.2012.031

- Meeks, S. (2020). Common themes for Im/migration and aging: Social ties, cultural obligations, and intersectional challenges. The Gerontologist, 60(2), 215–218. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnz193.

- Montayre, J., Neville, S., & Holroyd, E. (2017). Moving backwards, moving forward: The experiences of older Filipino migrants adjusting to life in New Zealand. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being, 12(1), 1347011. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/17482631.2017.1347011

- Morrow-Howell, N., Gonzales, E., Matz-Costa, C., & Greenfield, E. A. (2015). Increasing productive engagement in later life (Grand Challenges for Social Work Initiative Working Paper No. 8). American Academy of Social Work and Social Welfare.

- Mutchler, J. E., & Brallier, S. (1999). English language proficiency among older Hispanics in the United States. The Gerontologist, 39(3), 310–319.

- Neville, S., Wright-St Clair, V., Montayre, J., Adams, J., & Larmer, P. (2018). Promoting age-friendly communities: An integrative review of inclusion for older immigrants. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology, 33(4), 427–440. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10823-018-9359-3

- Nowell, L. S., Norris, J. M., White, D. E., Moules, N. J., 2017. Thematic analysis: Striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 16(1). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406917733847.

- Parekh, R., Maleku, A., Fields, N., Adorno, G., Schuman, D., & Felderhoff, B. (2018). Pathways to age-friendly communities in diverse urban neighborhoods: Do social capital and social cohesion matter? Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 61(5), 492–512.

- Park, N. S., Jang, Y., Chiriboga, D. A. & Chung, S. (2019) Social network types, health, and well-being of older Asian Americans. Aging & Mental Health, 23(11), 1569–1577.

- Park, N. S., Jang, Y., Lee, B. S., Ko, J. E., Haley, W. E., & Chiriboga, D. A. (2015). An empirical typology of social networks and its association with physical and mental health: A study with older Korean immigrants. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 70(1), 67–76. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbt065.

- Pillemer, K., Moen, P., Wethington, E., & Glasgow, N. (Eds.). (2000). Social integration in the second half of life. Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Poudel-Tandukar, K., Chandler, G. E., Jacelon, C. S., Gautam, B., Bertone-Johnson, E. R., & Hollon, S. D. (2019). Resilience and anxiety or depression among resettled Bhutanese adults in the United States. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 65(6), 496–506.

- Refugee Processing Center. (2020). Interactive reporting. Admissions and arrivals. https://www.wrapsnet.org/

- Sherman, C. W., Wan, W. H., & Antonucci, T. C. (2015). Social convoy model. In The encyclopedia of adulthood and aging. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118521373.wbeaa094.

- Sorkin, D. H., Nguyen, H., & Ngo-Metzger, Q. (2011). Assessng the mental halth needs and barriers to care among a diverse sample of Asian Ameican Older Adults. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 26(6), 595–602.

- Syed, M., McDonald, L., Smirle, C., Lau, K., Mirza, R., & Hitzig, S. (2017). Social isolation in Chinese older adults: Scoping review for age-friendly community planning. Canadian Journal on Aging, 36(2), 223–245.

- Tan, J. (2011). Older immigrants in the United States: The new old face of immigration. Bridgewater Review, 30(2), 28–30.

- Temple, B., & Edwards, R. (2002). Interpreters/translators and cross-language research: Reflexivity and border crossings. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 1(2), 1–12. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/160940690200100201

- Treas, J. & Batalova, J. (2007). Older immigrants. In K. Warner Schaie & P. Uhlenberg (Eds.), Social structures: The impact of demographic changes on the well-being of older persons (pp. 1–24). Springer.

- Treas, J., & Mazumdar, S. (2002). Older people in America’s immigrant families: Dilemmas of dependence, integration, and isolation. Journal of Aging Studies, 16(3), 243–258. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0890-4065(02)00048-8

- Van Hook, J. (2000). SSI eligibility and participation among elderly naturalized citizens and noncitizens. Social Science Research, 29(1), 51–69. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1006/ssre.1999.0652.

- Vega, A. (2017). The time intensity of childcare provided by older immigrant women in the United States. Research on Aging, 39(7), 823–848. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0164027515626774

- Villa, V. M., Wallace, S. P., Bagdasaryan, S., & Aranda, M. P. (2012). Hispanic baby boomers: Health inequities likely to persist in old age. The Gerontologist, 52(2), 166–176. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gns002

- Viruell-Fuentes, E. A. (2007). Beyond acculturation: Immigration, discrimination, and health research among Mexicans in the United States. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 65(7), 1524–1535. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.05.010

- Wachter, K., Bunn, M., Schuster, R. C., Boateng, G. O., Cameli, K., Johnson-Agbakwu, C. E. (2021). A scoping review of social support research among refugees in resettlement: Implications for conceptual and empirical research. Journal of Refugee Studies, feab040. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/feab040.

- Walters, W. H. (2002). Later-life migration in the Unites States: A review of recent research. Journal of Planning Literature, 17(1), 37–66. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/088541220201700103

- Warnes, A. M. (2001). The international dispersal of pensioners from affluent countries. International Journal of Population Geography, 7(6):373–388. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/ijpg.232.

- Watkins, D. (2017). Rapid and rigorous qualitative data analysis: The “RADaR” technique for applied research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 16(1), 160940691771213–160940691771219. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406917712131

- Wilmoth, J. M. (2012). A demographic profile of older immigrants in the United States. Public Policy & Aging Report, 22(2), 8–11. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/ppar/22.2.8

- Wong, R., A. Palloni, and B. Soldo (2007). Wealth in middle and old age in Mexico: The role of international migration. International Migration Review, 41(1):127–151. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-7379.2007.00059.x.

- World Health Organization. (2018). The global network for age-friendly cities and communities: Looking back over the last decade, looking forward to the next. https://www.who.int/aging/publications/gnafcc-report-2018/en/

- Wrobel, N. H., Farrag, M. F. & Hymes, R. W. (2009). Acculturative stress and depression in an elderly Arabic sample. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology, 24(3), 273–290.

- Wu, Z., & Penning, M. (2015). Immigration and loneliness in later life. Ageing and Society, 35(1), 64–95. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X13000470

- Yang, L. H., & WonPat-Borja, A. J. (2007). Psychopathology among Asian Americans. In F. T. L. Leong, A. Ebreo, L. Kinoshita, A. G. Inman, L. H. Yang, & M. Fu (Eds.), Handbook of Asian American psychology (pp. 379–405). Sage Publications, Inc.