Abstract

This paper investigates migrant representation patterns according to media political orientation, analyzing the coverage of key-events by liberal/conservative online newspapers of France, Greece, Italy, UK. From our textual and visual analysis, it is possible to recognize slight specificities between liberals and conservatives, but not indicative of a deep change of narratives. In both, we registered a prevalence of the “acceptance frame”, an infrequent use of negative tones in texts and aesthetic topic in images, among the “topics of suffering” by Boltanski. Moreover, a domesticity approach limiting the possibility of new narratives of Europe and the rest of the world emerges.

Introduction

It has been noted that media usually propose negative portrayals of migrants (Gemi et al., Citation2013; Goodman et al., Citation2017; Greussing & Boomgaarden, Citation2017; Heller, Citation2014; Holmes & Castaneda Citation2016; Vezovnik, Citation2017) and that public opinion is influenced by the news representation of immigration (Berry et al., Citation2015; Eberl et al., Citation2018).

The 2011 Qualitative Eurobarometer on Migrant Integration (European Commission, Citation2011) shows that it is believed that the media convey an overly negative view of migrants in society. The 2018 Special Eurobarometer 469 devoted to the same topic (European Commission, Citation2018) reaffirms these findings, confirming that, according to European public opinion, a negative portrayal of migrants is commonly shared by media: over a third (36%) of Europeans think the media present immigrants too negatively, while only just over one in ten (12%) respondents think they are presented too positively.

As stressed by these Eurobarometer surveys, media coverage contributes to the construction of socially-shared representations of refugees and asylum seekers (Blinder & Allen, Citation2016; Quinsaat, Citation2014) and therefore to their acceptance and integration (King & Wood, Citation2001; CitationSchemer, 2012). Although it has been hypothesized that visibility of immigrants in the news may imply less public alarmism on immigration (Boomgaarden & Vliegenthart, Citation2009), other studies found that the media visibility of immigration increases public anti-immigration attitudes (van Klingeren et al., Citation2015).

Starting from these premises, a question is if media with different political orientation, while dealing with specific topics like migrations, still adopt divergent representations or converge instead. Some studies have shown that conservative newspapers tend to harbor more negative views on immigration compared to liberal ones (Caviedes, Citation2018; Fryberg et al., Citation2012; Gabrielatos & Baker, Citation2008; KhosraviNik, Citation2010; KhosraviNik et al., Citation2012; Merolla et al., Citation2013), to an extent that may also depend on the country considered (Berry et al., Citation2015). However, this kind of studies, often limited to the Anglo-Saxon press, are so sparse that recent systematic reviews about media discourse of immigration in Europe just mention the issue of liberal-conservative narratives, but neglect it while conducting the analysis (Eberl et al., Citation2018): political orientation seems not to be so common as a variable in studies about migrant representation by media. As a matter of fact, many authors, although considering opposite political orientations while selecting newspapers to be analyzed, do not go further in explicitly comparing migrant representation in the two kinds of sources (Jaworsky, Citation2020; Mancini et al., Citation2021); nevertheless, comparison based on political orientation is more frequently found in analyses of discourses of political parties, possibly reported in newspapers (Bourbeau, Citation2011; Helbling, Citation2014) or in party manifestos (Alonso & Fonseca, Citation2012).

Besides recognizing media political orientation as a variable, other aspects are not enough explored while investigating migrant representation: among these, there is little comparative research on the media systems across different European countries, and online media are largely neglected (Berry et al., Citation2015; Eberl et al., Citation2018), also with reference to images accompanying the news (Fryberg et al., Citation2012).

In order to fill this gap in literature – related to low attention given to political orientation as a variable, to comparing different countries and considering new media, including images - our study aims at analyzing core issues of migrant representationFootnote1 by media emerging from the analysis of both written texts and images, focusing on political orientation of online newspapers in selected European countries.

We wonder if liberal and conservative newspapers spread similar views of migrations, an issue that has such a peculiar place in the public agenda, involving so many dimensions and being associated with individual and collective identities. We also wonder if the possible differences in representations are so deep to produce completely discordant framings of migrants and migration issues.

Specifically, we investigate if and how representation patterns of migrants vary along with political orientation in liberal/conservative newspapers, with reference to:

the coverage of key events related to migration;

the narrative frames and format, style and tone, in the written texts;

the visual representation of migrants’ suffering in the images, according to the “topics of suffering” developed by Luc Boltanski.

Most of the studies on migrant representation adopt the “frame analysis” approach (Lippi et al., Citation2020; Mancini et al., Citation2021; Scheufele & Tewksbury, Citation2007), where “to frame is to select some aspects of a perceived reality and make them more salient in a communicating context, in such a way to promote a particular problem definition, causal interpretation, moral evaluation and/or treatment recommendation” (Entman, Citation1993, p. 52); this methodology has been applied to examine media coverage of a variety of issues, besides those related to migrations (D’Angelo & Kuypers, Citation2010). These works propose a diversity of frame definitions – some referring to generic news frames, others to issue-specific frames (Eberl et al., Citation2018), heterogeneously detailed, often overlapping - that have not led to a shared categorization to conduct this kind of studies. To make an example, Benson (Citation2015) presented ten frames grouped in the three categories of enemy, victim and hero, also considered by other scholars (Friese, Citation2018; Horsti, Citation2016; Mitić, Citation2018), while the articulated classification in eight frames proposed by Philo et al. (Citation2013) has been enriched by an extra transversal frame (Joris et al., Citation2018).

Alongside, a body of scientific work highlighted how media coverage of migrants - including refugees and asylum seekers - focuses on two main representation frames (Eberl et al., Citation2018; Greussing & Boomgaarden, Citation2017), both narratively and visually (Amores et al., Citation2019). First, a negative and alarmist frame, within which migrants and refugees are portrayed as invaders and threat (Gemi et al., Citation2013; Heller, Citation2014; Lawlor, Citation2015; Lippi et al., Citation2020; Lueck et al., Citation2015; Lynn & Lea, Citation2003; Parker, Citation2015), associated with illegality, terrorism and crime (Buonfino, Citation2004; Ibrahim, Citation2005) and accused of draining public resources (Caviedes, Citation2015; Quinsaat, Citation2014; Silveira, Citation2016). Second, a frame representing migrants as innocent and passive victims in need of protection (Colombo, Citation2018; Horsti, Citation2008; Lippi et al., Citation2020; Parker, Citation2015; Van Gorp, Citation2005). It has been stressed that the predominance of these frames varies according to the media considered and socio-political contexts of different Western countries (Amores et al., Citation2019). Following to this literature, we decided to base our frame analysis of written texts on two main wide frames we called “acceptance” and “threat”, further explained in the next Materials and Methods section.

Framing approach, more commonly referred to written texts, has also been applied to image analysis: image, like word, can work like a framing device (Amores & Arcila, Citation2019). Nevertheless, although framing research should include visual as well as verbal content (Coleman, Citation2010), the application of the theoretical lens of framing to images is much less frequent. The difficulty in applying frames developed for written texts to images may be explained by the great differences existing between these two communication modalities, that go well beyond a different editorial production and selection process: visuals are decoded in different ways compared to texts and they can evoke meanings not explicitly addressed in the textual counterpart (Geise & Baden, Citation2015); they can be considered as the key to lead emotional responses to migration (Powell et al., Citation2015), “which are key determinants of attitudes and behaviors” (Lecheler et al., Citation2019, p. 700); it has been proved that showing a photographic image, while providing information about a current event, increases the possibility of an emotional response by the audience (Amores & Arcila, Citation2019; Maier et al., Citation2017). This is the reason why, for the analysis of images representing migrants, we decided to focus on the “topics of suffering” proposed by the sociologist Luc Boltanski (Citation1993), further described in the next Materials and Methods section.

Materials and methods

In conducting the analysis, we adopted a qualitative approach, drawing on news framing and critical discourse analysis. Basically, in investigating online newpapers, we made reference to the Multimodal Critical Discourse Analysis (MCDA), which recognizes the importance of textual and visual modalities in discourse analysis, aimed at finding meanings underlying different semantic structures (Jones, Citation2012; Ledin & Machin, Citation2020; LeVine & Scollon, Citation2004; Machin & Mayr, Citation2012; Royce & Bowcher, Citation2007). Developed as an extension of Critical Discourse Analysis, MCDA allows for the examination of every communicative form in the process of social construction, from written language to (audio) visual communication. In fact, the text of an article is only one of the many semiotic resources of (linguistic and non-linguistic) representation that are used in the construction of discourse.

Following Ledin and Machin (Citation2020), we mean “discourse” as socially constructed knowledge about the world, connected with complex ideas, as suggested by Foucault (Citation1977). Discourses are coded into material culture, as “semiotic material house our ideas, values, identities and templates for social interaction” (Ledin & Machin, Citation2020, p. 20). “Social semiotics” is the theory of communication proposed by Halliday (Citation1978), that differs from the semiotics of Barthes (Citation1977) as it “needs to look at the whole of the composition” (Ledin & Machin, Citation2020, p. 14) and is based on a system of choices that reflects what one wants to achieve in a context, in terms of influence, persuasion, dissuasion. Multimodality took up this notion of choice, moving away from what Kress and Van Leeuwen (Citation1996, Citation2001) called monomodal approach; all semiotic modes are forms of communication needing to be approached with the same attention and not institutionalized into separate disciplines, what became easier by the spread of technology.

MCDA has proved to be extremely useful in some dimensions of analysis, such as the iconographic/iconological analysis of images in order to explore "the way that individual elements in images, such as objects and settings are able to signify discourses in ways that might not be obvious at an initial viewing" (Machin & Mayr, Citation2012, p. 31).

Selection of the units of analysis: key-events, countries and newspapers

Visions on immigration are primarily constructed on events that elicit intense moments of public debate (Binotto et al., Citation2016). However, there are not many studies on immigration-related key-events in a short/medium timespan (Lippi et al., Citation2020; Rodrigues et al., Citation2021). For this reason, and in order to allow a more informed interpretation of data, we focused on the representation of key-events that occurred in 2016 over a period of three days - the day of the event, the day after and the day before - rather than considering the media coverage over the long-term.

We analyzed newspapers from France, Greece, Italy and the United Kingdom, among the top six European countries for the number of first asylum requests in 2016, according to Eurostat data.Footnote2 Moreover, in 2016, Italy and Greece formed part of the principal migration routes toward the EU, representing the top countries for arrivals by sea, while in UK the migration issue seems to have played a role in determining Brexit (Goodwin & Heath, Citation2016).

We selected eight events relevant both for European and national policies, representing the variety of themes in migration narrative, including policies and practices related to reception of migrants, management of flows, security and to social and cultural occasions. The selected 2016 events are:

the Golden Bear award at the Berlin International Film Festival to the movie Fuocoammare (Fire at Sea), shot on the island of Lampedusa (20 February);

the EU-Turkey Agreement for the management of migrant arrivals on the Greek coasts (18 March);

the visit of the Pope to Lesvos (16 April);

the evacuation of the Idomeni refugee camp (24 May);

the clashes between migrants and security forces in Ventimiglia - Italian town on the border with France (5 August);

the referendum in Hungary to decide whether or not to accept the national share of asylum seekers in line with the EU distribution plan (2 October);

the Lampedusa celebrations for the Day of Memory and Welcome (3 October);

the evacuation of the Calais refugee camp (24 October).

For each country we considered two online newspapers, according to the following criteria: first, widest audience, identified by the websites Alexa and SimilarwebFootnote3; second, political equilibrium, considering both conservative and liberal perspectives; finally, the chosen newspapers had to have freely accessible online archives, allowing deep and reproducible search by keywords.

As a result, the following newspapers were selected: La Repubblica (liberal) and il Giornale (conservative) for Italy; I Efimerida ton Syntakton (liberal) and I Kathimerini (conservative) for Greece; Le Monde (liberal) and Le Figaro (conservative) for France; The Guardian (liberal) and Daily Mail (conservative) for the UK.

The Daily Mail is a mid-market newspaper (Blinder & Allen, Citation2016), intermediate between broadsheet and tabloid (Silveira, Citation2016). The latter is a product which differs from newspapers, not only because of the editorial format, but also in journalistic language and quality. The functional difference between newspaper formats is, however, always less distinct; as a matter of fact, quality newspapers such as The Guardian also recently started to make use of the tabloid format. Moreover, it was observed that “the framing patterns of tabloid and quality media become highly similar” (Greussing & Boomgaarden, Citation2017, p. 1749), with predominance of stereotyped interpretations of refugees and asylum issues and thus persisting routines in both, expecially in times of crises; as a matter of fact, several outlet-specific analyses indicate that distinct framing patterns and practices in the coverage of tabloid and quality media do not appear to be reflected in the data (Greussing & Boomgaarden, Citation2017; Lawlor, Citation2015; O’Malley et al., Citation2012; Zaller, Citation2003).

Therefore, we decided to include the Daily Mail,Footnote4 given also its wide circulation.

We have to recognize that the selection process of newspapers according to the second criterium – political orientation – was not trivial, considering that the labels “conservative” and “progressive” necessarily include various nuances and that newspapers may, also deeply, swing in their political perspective over time. For this reason, for instance, in the case of Italy, we chose il Giornale instead of the more widely read Corriere della Sera, sometimes mentioned in literature as conservative.Footnote5

As in UNHCR report (Berry et al., Citation2015), research of news was conducted within the selected online newspapers archives using a common set of keywords – immigrant(s), refugee(s), migrant(s), asylum seeker(s) – integrated with specific sets of keywords for each event, translated in the considered languages taking into account linguistic specificities.Footnote6

Coding instruments

We focused on two different units of analysis – text and images – and developed a codebook including analytical grids with multiple variables.

For written texts we considered the following variables:

The type of article and narrative style of the texts. The following classification of journalistic formats was used for the article type: "news story", "editorial", "interview", "investigative/reportage" and "write-up". The following styles of the text were defined based on previous codification proposed by literature (Bernard et al., Citation2008; Caravita & Valente, Citation2013): "informative", characterized by the effort or pretension to impartially report facts, descriptions, notions and concepts; "persuasive", characterized by the conveying of assertive messages, inducing opinions and using moralistic tones; "propositional/participatory", characterized by the intent to involve the reader by actively calling the reader to the cause or highlighting proposals for solutions.

The overall tone of the article texts, “positive” or “negative”, taking as a reference pairs of opposite attributes referred to migrants. The negative ones are connected to the concept of distance (antithesis us/them), aversion (rejection, fear and hostility) and disparagement (of the other than self). Conversely, positive attributes are connected to the concepts of proximitas, caritas and humanitas. Texts not attributable to any of the two opposites were registered as “neutral”.

The narrative frames underlying texts in representing the migration theme. Following to previous researches (Valente et al., Citation2016), we considered two frames: “acceptance”, including both “moral acceptance” and “acknowledgement of worthiness” of migrants, the latter referred to intending migrants as an economic, demographic or cultural resource or as bearers of rights; and “threat” (in terms of security, identity, costs, or underlying the absence of political solutions), widely used in literature (Caviedes, Citation2015; Davidov et al., Citation2020; Triandafyllidou, Citation2018). We need to specify that we associated to “threat” also texts emphasizing problems connected to the presence of migrants that may cause a danger, a risk or a difficulty, a hazard, without necessarily evoking a “direct” threat.

Considering that any story can contain multiple frames (Lawlor, Citation2015), in order to identify the prevalent frame, we made reference to the whole text, considering not only the point of view of the authors, but also the sources cited in the article (interviewed or cited people). Indeed, the choice of the quotes is not casual, but the intentional product of a selection performed by authors and editors. In a holistic perspective, the written text was intended as a cauldron in which strategies of construction of significance come alive.

As stated in the Introduction, we based our analysis of images representing migrants on the “topics of suffering” developed by the sociologist Luc Boltanski (Citation1993), that focus on the possible emotional impact of pain representation on the observer. Topics of suffering seem to be suitable for visual representation analysis of migrants, as the predominance in the media of visual frames representing migrants as “victim, sufferer and in need” has been recently recognized (Amores et al., Citation2019). The classification proposed by Boltanski introduces three topics of suffering to describe how images can produce moods and actions in the viewer: the “topic of sentiment”, where the image pushes the viewer to sympathize with the sentiment of gratitude toward a “benefactor” (represented or just evoked) that intervenes – at denotative or connotative level - in favor of a “victim”; the “topic of denunciation”, where the image induces the viewer to feel indignant and angry toward a “perpetrator” (represented or just evoked); the “aesthetic topic”, where the pain is presented not to feel touched, nor indignant, but as pure suffering, so that the observer can truly feel empathy. Suffering is depicted facing the truth as pure pain, “in its reality” (Boltanski,Citation1993, p. 187), beyond the icons of the persecutor and benefactor, bringing the spectator and the represented subject together, as in front of an art-work: the self of the observer becomes inclusive and, in the relationship with the represented migrants, the “us/you” stereotype tends to lose consistency. Thus, in this topic, a representation of the migrant as a victim for which feeling pity is overcome.

We also included two new topics, the “topic of joy” and the “neutral topic”, to characterize images not linked to suffering, where the migrants depicted show a feeling of joy or do not show either pain or joy, respectively.

The coders in charge of carrying on critical qualitative reading and detecting the presence of the defined variables were seven in total, either mother tongue (Italian and Greek languages) or with high level in English and French reading. Following to an initial training where each variable was discussed in depth with the coders, the analysis was carried out independently, with periodic meetings focused on the analysis of dubious cases. Recorded data were processed with the SPSS statistics software.

Results

Unit of analysis distribution

The research led to the identification of 2,323 imagesFootnote7 and 526 texts, a total of 2,849 units of analysis. The great number of images is consistent with the registered increment of visual information over the past two decades (Grabe & Bucy, Citation2009), following the use of internet and social media.

With the exception of the UK, conservative newspapers in the selected countries published less records on the considered issues (32% in Italy, 21% in Greece, 34% in France). The specificity of the UK (85%) can be explained by the fact that the Daily Mail, the closest to a tabloid, produces a higher number of articles.

As for the key-event coverage, the Calais evacuation was the most covered event in terms of number of units of analysis. Anyway, we must consider that images are preponderant: if we only refer to written texts, the most covered event is the EU-Turkey Agreement (32%), while the evacuation of Calais moves to the second place (25%).

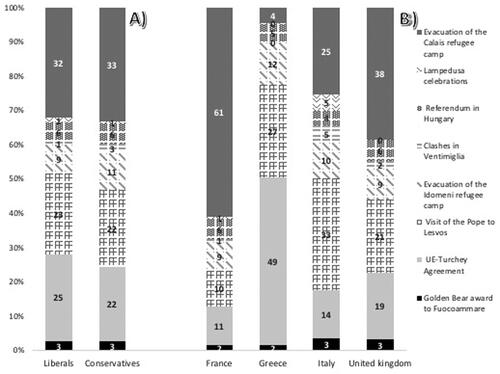

In order to verify the tendency of conservative newspapers to focus more on security-threat than on group-related problems, emerged from previous studies (Eberl et al., Citation2018), we analyzed the weighting given to the key-events by conservatives and liberals ().

Figure 1. Distribution of the units of analysis by event by: A) political orientation; B) country (percentage).

This tendency does not emerge from our analysis, both liberals and conservatives attributing a similar weight to the key-events, giving priority to the evacuation of Calais. This result is further supported by the “Gini Index of Heterogeneity” (between 0 and 1), calculated to describe attention given to events, which results as 0.88 for both groups of newspapers.

We also calculated the Gini Index for weighting the salience attributed to each event in the media arena at national level (): countries allocating a balanced space to the variety of events show a higher index; conversely, countries focusing more on specific events show a lower index. According to our results, the index value is 0.91 for Italy, followed by the UK, with 0.86, then Greece, with 0.75, and, finally, France, with 0.65.

The evacuation of Calais is the most covered event for France (63%) and the UK (40%), whose borders were directly involved; the EU-Turkey Agreement was covered in all countries, particularly by Greece, neighboring country (approximately half the units of analysis). Also the Idomeni evacuation refugee camp was covered in similar percentage by all countries, with slight predominance in Greece. The visit of the Pope to Lesvos involves almost one-third of the units of analysis. In Italy, this is the most covered event, given the geographical and historical proximity with the Vatican City. The referendum in Hungary found a limited but balanced representation in all countries, not concerning any one in a prevalent manner. Italian, the UK and, for a small percentage, French newspapers deal with Ventimiglia clashes, absent in Greek newspapers. The award to the film Fuocoammare at the Berlin Festival, an internationally significant cultural event, was afforded the small space usually reserved to cultural events in newspapers, although it was more covered in Italy. The UK and Greek newspapers do not cover the Lampedusa Celebration at all.

Insights from the written text analysis: format, style, tone and narrative frames

The analyzed articles are predominantly in news story format for both liberal (62.6%) and conservative (77.9%) newspapers. Liberals also give great importance to investigations and reportage, making up about 30% of the articles, which is almost double compared to conservative newspapers (17.4%). Both conservative and liberal newspapers feature interviews by about 10%.

The style prevailing in the written texts is informative, indicating the effort or presumption to describe facts in an objective manner. With reference to liberal and conservative newspapers, the informative style prevails in both (89 and 88% respectively), followed by the persuasive style, characterized by conveying assertive messages, inducing opinions and sometimes using moralistic tones (39 and 25% respectively). Examples of narrative fragments of these two styles are: “The demolition of the camp was scheduled to take place as part of government plans to clear it. Until the start of this week it was home to over 6,000 people” (Daily Mail, 25 October 2016, related to the evacuation of the Calais refugee camp) related to informative style, and, for persuasive style:

The USA, Russia, the EU governments, those who supported the dictators of the Middle East or their aspiring successors-collaborators of the imperialists in the face of the democratic uprisings of their peoples, have the audacity to close the borders to the oppressed. Those who wasted more than a trillion bombs in Afghanistan deny asylum to Afghan refugees!Footnote8 (I Efimerida ton Syntakton, 18 March 2016, related to the EU-Turkey Agreement).

An interesting difference between liberals and conservatives is observed with reference to the propositional/participatory style, adopted in 14% of articles of liberal newspaper as opposed to 4% in conservatives. An example of this style is: “We must have a great responsibility in welcoming. I have always said that building walls is not a solution, we have seen the fall of another wall in the last century. Nothing is solved. We must build bridges, but intelligently, with dialogue and integration”Footnote9 (la Repubblica, 17 April 2016, related to the visit of the Pope to Lesvos).

The written texts were also analyzed according to the two frames – acceptance and threat -, by means of multiple choice. We connected to the two frames 80% of the results of the analysis, having the remaining 20% resulted as not applicable.

As for the adopted frames, acceptance was the prevalent (60%) compared to threat (40%). In the comparison between national newspapers, we found the prevalence of the acceptance frame for France (62%), the UK (61%) and Italy (55%), with the only exception of Greece (43%). Within the acceptance frame, we looked both for “moral acceptance” and “acknowledgement of worthiness”, as defined in Materials and Methods. In the majority of cases, acceptance stands for “moral acceptance”, while “acknowledgement of worthiness” reached just the 3,5% of the whole acceptance recordings, 1,3% for conservatives and 2,2% for liberals; due to the exiguity of these cases, we did not further process the two categories separately.

We report a few examples of narrative fragments that exemplify the analyzed frames. For the threat frame:

Over the past quarter-century or so, Europeans have experienced huge transformations: the fall of the Berlin wall, globalization, and now the impact of migration, terrorism and illiberal forces. European ambitions that were entertained just two decades ago seem to have shriveled, opening up a Pandora’s box of grievances. Of course, the 2008 financial crisis hasn’t helped, but economic statistics often fail to measure the gap between what citizens expected their lives to be like and what they feel they have ended up with (The Guardian, 3 October 2016, related to the referendum in Hungary).

The unprecedented migratory flow continues to grow: after one million arrivals in 2015, undoubtedly the same number in 2016 while several million people flock to the gates of Europe, in the impotence of a European Union which fails to organize itself to fight criminal trafficking and is breaking down when, on the contrary, it should join forcesFootnote10 (Le Figaro, 24 October 2016, related to evacuation of the Calais refugee camp).

For the moral acceptance frame:

He told me «Lampedusa is a place of fishermen, we are fishermen, and fishermen, they all accept always, anything that comes from the sea». So this may be a lesson that (we) should learn to accept anything that comes from the sea, Rosi said (Daily Mail, 20 February 2016, related to the Golden Bear to Fuocoammare).

It is an evident duty of the state and the European Union and each member state to receive and care for asylum and to take care of refugees, those who seek refuge in our territory, those who should be treated as sacred persons in the same way as victims of international crimes, victims of war are always treated…Footnote11 (I Kathimerini, 17 March 2016, related to the EU-Turkey Agreement).

For the acknowledgement of worthiness frame:

There has been no integration policy. Europe needs to regain its capacity for integration. Many nomads have arrived and enriched their culture. There is a need for integrationFootnote12 (la Repubblica, 17 April 2016, related to the visit of the Pope to Lesvos).

Looking at the event variable, the threat frame prevails only for the coverage of the clashes in Ventimiglia (64%). The acceptance frame prevails for all the other events: for the EU-Turkey Agreement (52%) and the referendum in Hungary (53%) the gap between the two frames is not so relevant, while it grows for the two evacuations, of the Calais refugee camp (60%) and the Idomeni Camp (61%). The distance between the two frames becomes clear for the visit of the Pope to Lesvos and the announcement of the Golden Bear to Fuocoammare, decisively characterized by moral acceptance (78% and 86% respectively).

With reference to political orientation, we could not find relevant differences in the distribution of the frames: acceptance reached 59% for conservatives and 61% for liberals, threat having 41% for the former and 39% for the latter.

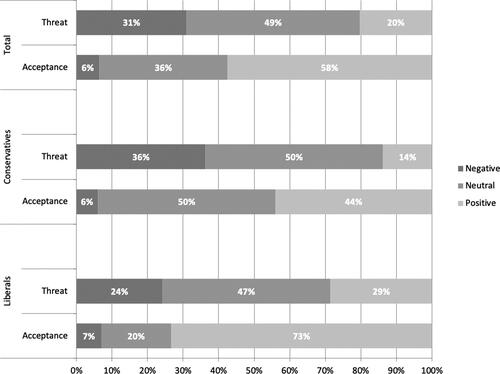

Nevertheless, interesting insights emerge if we connect frames and tone of the articles, an issue recommended by literature (Joris et al., Citation2018). If positive/neutral tone results as prevalent for the acceptance frame and neutral/negative for the threat frame, the analysis by political orientation shows significant differences. In fact, for both acceptance and threat frames, the tone used makes the difference for conservatives and liberals ().

Figure 2. Distribution of the tones for the two frames (threat and acceptance) by political orientation (percentage).

For the threat frame, conservatives show only 14% of positive tone, while liberals 29%, in the face of 36% and 24% of negative tone respectively. Even wider gap can be seen for the acceptance frame, characterized by positive tone in 44% of cases for conservatives and in 73% of cases for liberals. This result shows, on one hand, that the connection between frames and tone of the articles is complex, having multiple tones per each frame, and, on the other hand, that liberal newspapers tend to have more positive tones toward migrants compared to conservatives.

Insights from the image analysis: the topics of suffering

We analyzed images adopting the classification of the topics of suffering proposed by Boltanski, supplementing them with the “topic of joy” and the “neutral topic” for representations not focusing on pain.

Considering the distribution by event, the topic of denunciation is prevalent in almost all events, particularly for the evacuation of Calais and the EU-Turkey Agreement, often together with the aesthetic topic. The only exception is the visit of the Pope to Lesvos, where the topic of sentiment prevails, the Pope having the role of a "benefactor" arousing a sentiment of gratitude in the observer.

Representative examples of the three topics, taking into consideration the same event, the evacuation of the Idomeni camp, are: for the topic of sentiment, images in which the benefactor is represented by NGOs who patiently distribute food to migrants in the camp. Instead, the topic of denunciation is recognizable in actions and interventions of law enforcement officers, migrants leaving their own tents and collecting/packing their stuff in poor suitcases and garbage bags, and protest signs calling for human rights; other images illustrate long lines of migrants leaving the camp walking to the buses that will take them to other reception centers. Anger leading to the denunciation is moved by “sympathizing” (in the sense of suffering together, sharing a particular emotion) with the resentment of the victim (migrant) against the persecutor (police, government, EU). Finally, as for the aesthetic topic, regardless the subject of the picture, examples are migrants posing and looking at the photographer’s camera, as in a hand-painted family portrait; or static and serious faces of two migrants in front of the dilapidated railway station of Idomeni.

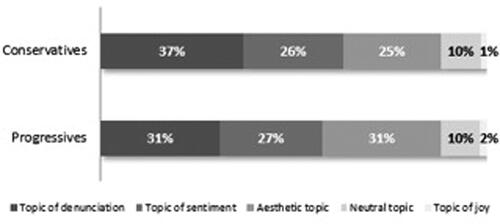

In the analysis of images representing migrants (57% of the total), the topic of denunciation is prevalent for conservative newspapers (37% conservatives against 31% liberals) ().

Figure 3. Distribution of topics in the images representing migrants by political orientation (percentage).

In liberals, the aesthetic topic has a weight equal to the topic of denunciation (31% against 25% for conservatives). The topic of sentiment has a similar weight for conservatives and liberals, being the second prevailing topic for conservatives (26%) and the third for liberals (27%). So, the distribution of the three topics of suffering results as more balanced for liberal newspapers. As expected, the topic of joy and the neutral topic are residual, achieving respectively: 2% in liberals and 1% in conservatives for the topic of joy and 10% for neutral topic in both groups of newspapers.

With reference to the three topics of sufferingFootnote13 we went more in depth, detecting further traits of the way migrants are represented, focusing on age, gender and individual/group representation.

The images of children and women resulted as a minority for both liberals and conservatives: only 13% of images represent just children (less than 40% if we sum images representing just children and children together with adults) and less than 10% of images represent just women (less than 35% if we sum images representing only women and women together with men).

Anyway, we found a correlation between the topic of sentiment and representation of children and women: images characterized by this topic are those in which children – alone or with adults - and women - just women or with males - prevail, confirming the use of women and children as victims to raise pity (Baines, Citation2004; Binotto et al., Citation2016; Johnson, Citation2011; Malkki, Citation1996; Silveira, Citation2016). For both liberals and conservatives, about 70% of images classified as topic of sentiment include children and more than 60% include women.

Going to the analysis of individual/group representation, if images of migrants as single individuals are a minority both for liberals (25%), and conservatives (19%), the aesthetic topic catalyzes representation of single individuals for liberal newspapers, reaching the 34%. This result can be read with reference to the traditional association between group representation and dehumanization (Esses et al., Citation2013; Greussing & Boomgaarden, Citation2017; Rajaram, Citation2002; Tudisca et al., Citation2019).

Discussion

Based on the findings related to written texts and images analysis, our study does not detect a completely different tendency in conservatives and liberal newspapers when writing about migration and representing migrants. The slight differences between the two groups of politically oriented newspapers cannot allow to infer the presence of strongly different narrative frames.

It is possible to recognize certain specificities of liberal online newspapers compared to conservative ones, in both texts and images: in the former, we find more various communicative formats, a more positive representation of migrants; liberals publish as much images classifiable according to the topic of denunciation as to the aesthetic topic. Nevertheless, these specificities are not indicative of a deep change of narrative frames compared to conservative newspapers.

Starting with the written text frames, conservative and liberal newspapers are associated by the prevalence of the acceptance frame, with the only exception of Greece, a country facing a deep internal crisis. However, what is even more important to highlight is that, independently on political orientation, the acceptance frame is not translated into an acknowledgement of immigrants as a possible resource or bearers of rights, which is hardly present in the press (Berry et al., Citation2015; Fryberg et al., Citation2012), but remains limited to the concept of moral acceptance; the acknowledgement of migrants as possible resource – cultural, social, economic - is even infrequent compared to discourses about migrants’ rights, and, meaningfully, can mainly be found in the Pope’s words, expecially with reference to the multicultural dimension.

So, beyond the moral acceptance-threat dichotomy, a third course in the newspapers debate, valuing the potential contributions migrants could give to the destination countries, does not emerge. Some differences between liberal and conservative newspapers appear when correlating frames and tone of the coverage; multiple tones coexist for each frame, which means that the same frame can be used in contexts that are in favor of migrants or not. With reference to political orientation, there is not much difference between conservatives and liberals in the frames adopted, being frames highly dependent on the event; what changes is the tone used toward migrants within each frame: liberals tend to use a more positive tone, in particular in relation to the acceptance frame, but also when dealing with the threat frame. But what matters is that the negative tone does not prevail neither in liberals nor in conservatives.

Moreover, further differences between liberals and conservatives emerge in the format and style of articles. Investigations and reportages, closely linked to the concept of investigative journalism, are not neglected by liberal online newspapers, representing about one third of the format of the articles.

In addition, in liberal newspapers we find the presence of writing styles other than the informative style: they alternate with a style aimed at involving the reader in a propositional/participatory context, referred to contents offering possible proposals for political solutions. Nevertheless, for both liberal and conservative newspapers the dominant format is the news stories, characterized by an informative style not leaving too much space for proposing original reflections or further in-depth discourses, probably more present in the print version or in the paid online version of the newspapers.

As for the visual analysis, introducing a new approach to the analysis of migrant representation based on “topics of suffering”, we found out that, while for liberals the aesthetic topic reaches the same level as denunciation and for conservatives the aesthetic topic is a minority, the sum of denunciation and sentiment topic is prevalent for both.

The topic of denunciation, as well as the topic of sentiment, is usually associated to a representation of migrants as victims. Depicting migrants as victims, a tendency highlighted in literature (Barnett, Citation2002; Bos et al., Citation2016; Chouliaraki, Citation2012; Eberl et al., Citation2018), not always helps the migrant’s cause, tending to justify the condition and the status quo of refugees and to emphasize the boundaries between them and the natives (Esses et al., Citation2013). Indeed, the topics of sentiment and denunciation, focusing on the figures of the benefactor and the persecutor, follow a compassionate and paternalistic attitude, that risks to reinforce stereotyped representations of refugees.

Conversely, the role of aesthetics is to “challenging any representational system that aims at reducing migrant subjectivities to mere bodies without words and yet threatening in their presence as a mass” (Mazzara, Citation2015, p. 460). The aesthetic topic enhances individual identities and makes them come out of anonymity, turning migrants in human beings with the right to be seen. We found a correlation between the aesthetic topic and images representing individuals, that in our analysis are a minority compared to group representation. This confirms the role of aesthetics in overcoming a representation that in literature has been associated to multitude representation and de-humanisation (Baines, Citation2004; Esses et al., Citation2013; Greussing & Boomgaarden, Citation2017; Johnson, Citation2011; Malkki, Citation1996; Rajaram, Citation2002; Silveira, Citation2016), being emotional closeness and empathy typical of the aesthetic experience. Based on these reflections, not finding a dominance of the aesthetic topic both in liberal and conservative newspapers is noteworthy.

Our analysis does not confirm previous literature for which, in Western countries, media coverage of immigration has become more and more negative, although it supports previous researches (Eberl et al., Citation2018; Wodak & KhosraviNik, Citation2013) stating that liberal newspapers exhibit more positive portrayals of immigrants than their conservative counterparts (Geißler, Citation2000).

Despite the fact that we cannot definitely confirm the idea that, in immigration politics, the typical categories of left and right tend to overlap and become “scrambled”, as suggested by Benson (Citation2013) and other studies (Caviedes, Citation2018), a positive portrayal of migrants by liberal newspapers does not seem to be supported by an actually different, more complex narrative of migrations, that could have emerged through the “acknowledge of worthiness” frame.

We cannot even find a significantly different behavior of conservatives and liberals with reference to the events covered. In this case, the political orientation gives way to the media national belonging. In parallel, our study reveals the tendency of national newspapers to unbalance the coverage of news concerning migrations in favor of what takes place within national borders or close territories, showing a difficulty in acquiring migration as a common European issue. Failing to overcome local/national perspectives similarly characterizes liberal and conservative online newspapers. This tendency can be explained in terms of “domestication” (De Swert & De Smedt, Citation2014) or “domesticity” (Gleissner & de Vreese, Citation2005), referring to the assumption that “journalists report foreign events linking the story to the local, domestic situation” (Mancini et al., Citation2021, p. 4). The issue turns out to be: what is domestic, what is related to home? Differently from own national states, Europe seems to be excluded by the concept of home. As Triandafyllidou noted, “us” versus “them” is not always used to oppose Europeans to migrants: sometimes it states internal divisions between countries (Triandafyllidou, Citation2018, p. 212). The “threatening internal other” observed by Downing (Citation2019), with reference to depicting people or social groups within countries as if they were homogeneous stable entities, seems to act not only in stigmatizing social groups within the national borders, but also in keeping distance between European countries.

It has been observed that narratives are “the ligaments of identity, revealing how one constructs the boundaries of, and the connections between, the self and the other” (Andrews, Citation2007, p. 4).

Shaping new frames, introducing new narratives, requires challenging norms of tellability shared in social and political environments: “it is precisely through the act of contesting what counts as tellable that counter-discourses develop” (Cantat, Citation2015, p. 7).

What connects our findings – the detected differences in liberal and conservative newspapers not being enough to translate into a change in narrative frames, with both kinds of newspapers being subject to domesticity approach – is a symptom of the difficulty, or maybe lack of willingness, in abandoning the “us” versus “them” narrative dichotomy, that limits the possibility to be open to new narrative frames in the vision of both Europe and the rest of the world.

The main limits of the present study are connected to the need to widen the sample of European countries considered. In perspective, it would also be relevant to connect this study with further media effect research to investigate readers’ reactions to images classified according to the Boltanski topics of suffering, that we propose as a new theoretical lens to analyze images representing migrants.

Notes

1 Within the term “migrants” we included refugees, asylum seekers and immigrants, as summarized by the term RASIM (KhosraviNik, Citation2010).

2 121.185, 76.790, 49.875, 39.240 respectively (Eurostat, 2016).

3 See the following websites: www.alexa.com and www.similarweb.com.

4 Among the UK conservative newspapers, we did not consider the broadsheet The Daily Telegraph, which also has a wide audience, because it of its less accessible archive.

5 While in its very first article of March 5th 1876 Corriere della Sera called itself conservative, in its historical development within the Italian political context it presented many changes: at the end of the Sixties, the Director was in favor of an alliance of the center with the reformist left. In 1972, the newspaper further swung to the left, also following political belonging of editors and journalists. In 1996 and 2006, the support to the center-left coalitions became even more explicit. Further on, there has been a continuous exchange of journalist between Corriere della Sera and la Repubblica, sign of an increasing political closeness. Maybe due to this historical path, we registered a discordance in literature on the political orientation of Corriere della Sera (Berry et al., Citation2015).

6 While in Italian "profugo" and "rifugiato" have different meanings, in English, French and Greek the two words coincide, as already noted (Berry et al., Citation2015).

7 In photogalleries, we considered each photograph as a single image.

8 Original text in Greek: Οι ΗΠΑ, η Ρωσία, οι κυβερνήσεις της Ε.Ε., εκείνοι που στήριξαν τους δικτάτορες της Μ. Ανατολής ή τους επίδοξους διαδόχους τους-συνεργάτες των ιμπεριαλιστών απέναντι στις δημοκρατικές εξεγέρσεις των λαών τους, έχουν το θράσος να κλείνουν τα σύνορα στους κατατρεγμένους. Εκείνοι που σπατάλησαν πάνω από ένα τρισεκατομμύριο σε βόμβες στο Αφγανιστάν αρνούνται άσυλο στους Αφγανούς πρόσφυγες!

9 Original text in Italian: Dobbiamo avere una grande responsabilità nell’accoglienza. Ho sempre detto che fare muri non è una soluzione, abbiamo visto il secolo scorso la caduta di uno. Non si risolve niente. Dobbiamo fare ponti, ma in modo intelligente, con il dialogo, l’integrazione.

10 Original text in French: Le flux migratoire sans précédent historique, ne cesse de s’amplifier: après un million d’entrées en 2015, sans doute le même nombre en 2016 alors que plusieurs millions de personnes se pressent aux portes de l’Europe, dans l’impuissance d’une Union européenne qui ne parvient pas à s’organiser pour combattre les trafics criminels et se décompose alors qu’elle devrait au contraire unir ses forces.

11 Original text in Greek: Είναι αυτονόητη υποχρέωση του κράτους και της Ε.Ε. και κάθε κράτους-μέλους να υποδέχεται και να μεριμνά, να παρέχει άσυλο και να φροντίζει τους πρόσφυγες, εκείνους που αναζητούν καταφυγή στο έδαφός μας, εκείνους οι οποίοι πρέπει να αντιμετωπίζονται ως πρόσωπα ιερά όπως πάντοτε αντιμετωπίζονται τα θύματα διεθνών εγκλημάτων, τα θύματα πολέμου

12 Original text in Italian: Non c’è stata una politica d’integrazione. L’Europa deve riprendere questa capacità d’integrare, sono arrivate tante persone nomadi e ne hanno arricchito la cultura. C’è bisogno d’integrazione.

13 We excluded from this further analysis the topic of joy for the exiguity of cases.

References

- Alonso, S., & Fonseca, S. C. D. (2012). Immigration, left and right. Party Politics, 18(6), 865–884. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068810393265

- Amores, J. J., & Arcila, C. (2019). Deconstructing the symbolic visual frames of refugees and migrants in the main Western European media [Paper presentation]. In Proceedings of the seventh international conference on technological ecosystems for enhancing multiculturality (pp. 911–918). https://doi.org/10.1145/3362789.3362896

- Amores, J. J., Calderón, C. A., & Stanek, M. (2019). Visual frames of migrants and refugees in the main western European media. Economics & Sociology, 12(3), 147–161. https://doi.org/10.14254/2071-789X.2019/12-3/10

- Andrews, M. (2007). Shaping history: Narratives of political change. Cambridge University Press.

- Baines, E. K. (2004). Vulnerable bodies: Gender, the UN and the global refugee crisis. Ashgate.

- Barnett, L. (2002). Global governance and the evolution of the international refugee regime. International Journal of Refugee Law, 14(2 and 3), 238–262. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijrl/14.2_and_3.238

- Barthes, R. (1977). Image-music-text. Fontana.

- Benson, R. (2013). Shaping immigration news. Cambridge University Press.

- Benson, R. (2015). Quarante ans d’immigration dans les médias en France et aux Etats-Unis. Le Monde Diplomatique, 5, 1–1.

- Bernard, S., Carvalho, G., Berger, D., Thiaw, S. M., Sabah, S., Skujiene, G., Abdelli, S., Calado, F., & Asaad, Y. (2008). Sexually transmitted infections and the use of condoms in biology textbooks. A comparative analysis across sixteen countries. Science Education International, 19(2), 185–208.

- Berry, M., Garcia-Blanco, I., Moore, K. (Eds.) (2015). Press coverage of the refugee and migrant crisis in the EU: A content analysis of five European countries. Report prepared for the United Nations High Commission for Refugees. United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. https://www.unhcr.org/protection/operations/56bb369c9/press-coverage-refugee-migrant-crisis-eu-content-analysis-fiveeuropean.html

- Binotto, M., Bruno, M., Lai, V. (Eds.) (2016). Tracciare confini. L’immigrazione nei media italiani. Franco Angeli.

- Blinder, S., & Allen, W. L. (2016). Constructing immigrants: Portrayals of migrant groups in British national newspapers, 2010–2012. International Migration Review, 50(1), 3–40. https://doi.org/10.1111/imre.12206

- Boltanski, L. (1993). La souffrance à distance. Editions Métailié.

- Boomgaarden, H. G., & Vliegenthart, R. (2009). How news content influences anti-immigration attitudes: Germany, 1993–2005. European Journal of Political Research, 48(4), 516–542. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6765.2009.01831.x

- Bos, L., Lecheler, S., Mewafi, M., & Vliegenthart, R. (2016). It’s the frame that matters: Immigrant integration and media framing effects in the Netherlands. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 55, 97–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2016.10.002

- Bourbeau, P. (2011). The securitization of migration: A study of movement and order. Taylor & Francis.

- Buonfino, A. (2004). Between unity and plurality: The politicization and securitization of the discourse of immigration in Europe. New Political Science, 26(1), 23–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/0739314042000185111

- Cantat, C. (2015). Narratives and counter-narratives of Europe. Constructing and contesting Europeanity. Cahiers Mémoire et Politique, 3, 5–30. https://doi.org/10.25518/2295-0311.138

- Caravita, S., & Valente, A. (2013). Educational approach to environmental complexity in life sciences school manuals: an analysis across Countries. In M. Khine (Ed.), Critical analysis of science textbooks (pp. 173–198). Springer.

- Caviedes, A. (2015). An emerging ‘European’ news portrayal of immigration? Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 41(6), 897–917. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2014.1002199

- Caviedes, A. (2018). European press portrayals of migration: national or partisan constructs? Politics, Groups, and Identities, 6(4), 802–813. https://doi.org/10.1080/21565503.2018.1523058

- Chouliaraki, L. (2012). Between pity and irony – paradigms of refugee representation in humanitarian discourse. In K. Moore, B. Gross, & T. Threadgold (Eds.), Migrations and the media (pp.13–31). Peter Lang.

- Coleman, R. (2010). Framing the pictures in our heads: Exploring the framing and agenda-setting effects of visual images. In D’Angelo, P., Kuypers, J. A. (Eds.), Doing news framing analysis (pp. 249–278). Routledge.

- Colombo, M. (2018). The representation of the “European refugee crisis” in Italy: Domopolitics, securitization, and humanitarian communication in political and media discourses. Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies, 16(1-2), 161–178. https://doi.org/10.1080/15562948.2017.1317896

- D’Angelo, P., & Kuypers, J. A. (2010). Doing news framing analysis. Routledge.

- Davidov, E., Seddig, D., Gorodzeisky, A., Raijman, R., Schmidt, P., & Semyonov, M. (2020). Direct and indirect predictors of opposition to immigration in Europe: individual values, cultural values, and symbolic threat. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 46(3), 553–573.

- De Swert, K., & De Smedt, J. (2014). Hosting Europe, covering Europe? Domestication in the EU-coverage on Belgian television news (2003–2012). In A. Stepinska (Ed.), Media and communication in Europa (pp. 33–44). Logos Verlag.

- Downing, J. (2019). French muslims in perspective: Nationalism, post-colonialism and marginalisation under the republic. Springer.

- Eberl, J.-M., Meltzer, C. E., Heidenreich, T., Herrero, B., Theorin, N., Lind, F., Berganza, R., Boomgaarden, H. G., Schemer, C., & Strömbäck, J. (2018). The European media discourse on immigration and its effects: a literature review. Annals of the International Communication Association, 42(3), 207–223. https://doi.org/10.1080/23808985.2018.1497452

- Entman, R. M. (1993). Framing: Toward clarification of a fractured paradigm. Journal of Communication, 43(4), 51–58. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.1993.tb01304.x

- Esses, V. M., Medianu, S., & Lawson, A. S. (2013). Uncertainty, threat, and the role of the media in promoting the dehumanization of immigrants and refugees. Journal of Social Issues, 69(3), 518–536. https://doi.org/10.1111/josi.12027

- European Commission, Directorate General Home Affairs, Directorate General Communication. (2011). Qualitative eurobarometer - Migrant integration.

- European Commission, Directorate-General for Migration and Home Affairs, Directorate-General for Communication. (2018). Special Eurobarometer 469. Integration of Immigrants in the European Union. European Union, 2018. https://doi.org/10.2837/918822

- Foucault, M. (1977). The archeology of knowledge. Tavistock.

- Friese, H. (2018). Framing Mobility. Refugees and the social imagination. In D. Bachmann-Medick, & J. Kugele (Eds.), Migration. Changing concepts, critical approaches. (pp. 45–62). De Gruyter.

- Fryberg, S. A., Stephens, N. M., Covarrubias, R., Markus, H. R., Carter, E. D., Laiduc, G. A., & Salido, A. J. (2012). How the media frames the immigration debate: The critical role of location and politics. Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy, 12(1), 96–112. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1530-2415.2011.01259.x

- Gabrielatos, C., & Baker, P. (2008). Fleeing, sneaking, flooding: A corpus analysis of discursive constructions of refugees and asylum seekers in the UK press, 1996-2005. Journal of English Linguistics, 36(1), 5–38. https://doi.org/10.1177/0075424207311247

- Geißler, R. (2000). Bessere Pra¨sentation durch bessere Repra¨sentation. In Migranten und Medien, (pp. 129–146). Wiesbaden: VS Verlag fu¨ r Sozialwissenschaften.

- Geise, S., & Baden, C. (2015). Putting the image back into the frame: Modeling the linkage between visual communication and frameprocessing theory. Communication Theory, 25(1), 46–69. https://doi.org/10.1111/comt.12048

- Gemi, E., Ulasiuk, I., & Triandafyllidou, A. (2013). Migrants and media newsmaking practices. Journalism Practice, 7(3), 266–281. https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2012.740248

- Gleissner, M., & de Vreese, C. H. (2005). News about the EU constitution: Journalistic challenges and media portrayal of the European Union constitution. Journalism, 6(2), 221–242. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884905051010

- Goodman, S., Sirriyeh, A., & McMahon, S. (2017). The evolving (re)categorisations of refugees throughout the “refugee/migrant crisis. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 27(2), 105–114. https://doi.org/10.1002/casp.2302

- Goodwin, M. J., & Heath, O. (2016). The 2016 referendum, Brexit and the left behind: An aggregate‐level analysis of the result. The Political Quarterly, 87(3), 323–332. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-923X.12285

- Grabe, M. E., & Bucy, E. P. (2009). Image bite politics: News and the visual framing of elections. Oxford University Press.

- Greussing, E., & Boomgaarden, H. G. (2017). Shifting the refugee narrative? An automated frame analysis of Europe’s 2015 refugee crisis. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 43(11), 1749–1774. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2017.1282813

- Halliday, M. A. K. (1978). Language as a social semiotic system. Arnold.

- Helbling, M. (2014). Framing immigration in Western Europe. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 40(1), 21–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2013.830888

- Heller, C. (2014). Perception management: Deterring potential migrants through information campaigns. Global Media and Communication, 10(3), 303–318. https://doi.org/10.1177/1742766514552355

- Holmes, S. M., & Castaneda, H. (2016). Representing the ‘European refugee crisis’ in Germany and beyond: Deservingness and difference, life and death. American Ethnologist, 43(1), 12–24. https://doi.org/10.1111/amet.12259

- Horsti, K. (2008). Hope and despair: Representation of Europe and Africa in news coverage of migration crisis. Communication Studies, 3, 125–156.

- Horsti, K. (2016). Visibility without voice: Media witnessing irregular migrants in BBC online news journalism. African Journalism Studies, 37(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/23743670.2015.1084585

- Ibrahim, M. (2005). The securitization of migration: A racial discourse. International Migration, 43(5), 163–187. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2435.2005.00345.x

- Jaworsky, B. N. (2020). The politics of selectivity: Online newspaper coverage of refugees entering Canada and the United States. Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies, 18(4), 467–480. https://doi.org/10.1080/15562948.2019.1702750

- Johnson, H. L. (2011). Click to Donate: visual images, constructing victims and imagining the female refugee. Third World Quarterly, 32(6), 1015–1037. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2011.586235

- Jones, R. H. (2012). Multimodal discourse analysis. In C. A. Chapelle (ed.), The encyclopedia of applied linguistics. Blackwell Publishing.

- Joris, W., d’Haenens, L., Van Gorp, B., & Mertens, S. (2018). The refugee crisis in Europe: A frame analysis of European newspapers. In S. F. Krishna-Hensel (Ed.), Migrants, refugees, and the media: The new reality of open societies. Routledge.

- KhosraviNik, M. (2010). The representation of refugees, asylum seekers and immigrants in British newspapers: A critical discourse analysis. Journal of Language and Politics, 9(1), 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1075/jlp.9.1.01kho

- KhosraviNik, M., Krzyżanowski, M., & Wodak, R. (2012). Dynamics of representation in discourse: Immigrants in the British press. In M. Messer, R. Schroeder, & R. Wodak (Eds.), Migrations: Interdisciplinary perspectives (pp. 283–295). Springer.

- King, R., & Wood, N. (2001). Media and migration: constructions of mobility and difference. Routledge.

- Kress, G., & Van Leeuwen, T. (1996). Reading images: The grammar of visual design. Routledge.

- Kress, G., & Van Leeuwen, T. (2001). Multimodal discourse: The modes and media of contemporary communication. Arnold.

- Lawlor, A. (2015). Local and national accounts of immigration framing in a cross-national perspective. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 41(6), 918–941. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2014.1001625

- Lecheler, S., Matthes, J., & Boomgaarden, H. (2019). Setting the agenda for research on media and migration: State-of-the-art and directions for future research. Mass Communication and Society, 22(6), 691–707. https://doi.org/10.1080/15205436.2019.1688059

- Ledin, P., & Machin, D. (2020). Introduction to multimodal analysis. Bloomsbury Publishing.

- LeVine, P., & Scollon, R. (2004). Discourse and technology: Multimodal discourse analysis. Georgetown University Press.

- Lippi, K., McKay, F. H., & McKenzie, H. J. (2020). Representations of refugees and asylum seekers during the 2013 federal election. Journalism, 21(11), 1611–1619. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884917734079

- Lueck, K., Due, C., & Augoustinos, M. (2015). Neoliberalism and nationalism: Representations of asylum seekers in the Australian mainstream news media. Discourse & Society, 26(5), 608–629. https://doi.org/10.1177/0957926515581159

- Lynn, N., & Lea, S. (2003). A phantom menace and the new apartheid: The social construction of asylum-seekers in the United Kingdom. Discourse & Society, 14(4), 425–452. https://doi.org/10.1177/0957926503014004002

- Machin, D., & Mayr, A. (2012). How to do critical discourse analysis: A multimodal introduction. Sage.

- Maier, S. R., Slovic, P., & Mayorga, M. (2017). Reader reaction to news of mass suffering: Assessing the influence of story form and emotional response. Journalism, 18(8), 1011–1029. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884916663597

- Malkki, L. H. (1996). Speechless emissaries: Refugees, humanitarianism, and dehistoricization. Cultural Anthropology, 11(3), 377–404. https://doi.org/10.1525/can.1996.11.3.02a00050

- Mancini, P., Mazzoni, M., Barbieri, G., Damiani, M., & Gerli, M. (2021). What shapes the coverage of immigration. Journalism, 22(4), 845. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884919852183

- Mazzara, F. (2015). Spaces of visibility for the migrants of Lampedusa: The counter narrative of the aesthetic discourse. Italian Studies, 70(4), 449–464. https://doi.org/10.1080/00751634.2015.1120944

- Merolla, J., Ramakrishnan, S. K., & Haynes, C. (2013). Illegal," "undocumented," or "unauthorized": Equivalency frames, issue frames, and public opinion on immigration. Perspectives on Politics, 11(3), 789–807. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592713002077

- Mitić, A. (2018). The strategic framing of the 2015 migrant crisis in Serbia. In S. F. Krishna-Hensel (Ed.), Migrants, refugees, and the media (pp. 121–150). Routledge.

- O’Malley, E., Brandenburg, H., Flynn, R., McMenamin, I., & Rafter, K. (2012). Explaining media framing of election coverage: Bringing in the political context. Working Paper. available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2189468.

- Parker, O. F. (2015). The African-American entrepreneur–crime drop relationship growing African-American business ownership and declining youth violence. Urban Affairs Review, 51(6), 751–780. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078087415571755

- Philo, G., Briant, E., & Donald, P. (2013). Bad news for refugees. Pluto Press.

- Powell, T. E., Boomgaarden, H. G., De Swert, K., & de Vreese, C. H. (2015). A clearer picture: The contribution of visuals and text to framing effects. Journal of communication, 65(6), 997–1017.

- Quinsaat, S. (2014). Competing news frames and hegemonic discourses in the construction of contemporary immigration and immigrants in the United States. Mass Communication and Society, 17(4), 573–596. https://doi.org/10.1080/15205436.2013.816742

- Rajaram, P. K. (2002). Humanitarianism and representations of the refugee. Journal of Refugee Studies, 15(3), 247–264. https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/15.3.247

- Rodrigues, U. M., Niemann, M., & Paradies, Y. (2021). Representation of news related to culturally diverse population in Australian media. Journalism, 22(9), 2313–2319. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884919852884

- Royce, T. D., & Bowcher, W. L. (2007). New directions in the analysis of multimodal discourse. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Schemer, C. (2012). The influence of news media on stereotypic attitudes toward immigrants in a political campaign. Journal of Communication, 62(5), 739–757. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2012.01672.x

- Scheufele, D. A., & Tewksbury, D. (2007). Framing, agenda setting, and priming: The evolution of three media effects models. Journal of Communication, 57(1), 9–20. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0021-9916.2007.00326.x

- Silveira, C. (2016). The representation of (illegal) migrants in the British News. Networking Knowledge, 9(4), 1–16.

- Triandafyllidou, A. (2018). A “refugee crisis” unfolding:“Real” events and their interpretation in media and political debates. Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies, 16(1-2), 198–216. https://doi.org/10.1080/15562948.2017.1309089

- Tudisca, V., Pelliccia, A., & Valente, A. (2019). Imago migrantis. Migranti alle porte dell’Europa nell’era dei media (pp. 1–244). CNR-IRPPS e-Publishing.

- Valente, A., Castellani, T., Vitali, G., & Caravita, S. (2016). Le migrant dans les manuels italiens d’histoire et de géographie: l’impact des images, le rôle des styles, l’ambiguïté des valeurs. In Denimal, D. Amandine, B. Maurer, & M. Verdelhan-Bourgade (Eds.), Migrants et migrations dans les manuels scolaires en méditerranée. Editions L’Harmattan.

- Van Gorp, B. (2005). Where is the frame? Victims and intruders in the Belgian press coverage of the asylum issue. European Journal of Communication, 20(4), 484–507. https://doi.org/10.1177/0267323105058253

- van Klingeren, M., Boomgaarden, H. G., Vliegenthart, R., & de Vreese, C. H. (2015). Real world is not enough: The media as an additional source of negative attitudes toward immigration, comparing Denmark and the Netherlands. European Sociological Review, 31(3), 268–283. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcu089

- Vezovnik, A. (2017). Securitizing Migration in Slovenia: A discourse analysis of the Slovenian refugee situation. Journal of Immigrant and Refugee Studies, 16(1-2), 1–18.

- Vreese, C. H. (2005). News Framing: Theory and Typology. Information Design Journal, 13(1), 51–62. https://doi.org/10.1075/idjdd.13.1.06vre

- Wodak, R., & KhosraviNik, M. (2013). Right-wing populism in Europe: Politics and discourse. B. Mral (Eds.). Bloomsbury Academic.

- Zaller, J. (2003). A new standard of news quality: burglar alarms for the monitorial citizen. Political Communication, 20(2), 109–130. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584600390211136