Abstract

Since the so-called ‘migration crisis’ in 2015/16, EU governments’ efforts to launch online campaigns to inform potential migrants about the risks of irregularity have increased. These migration management tools often apply dissuasive messages, declaring to support migrants to make informed decisions. This article investigates such campaigns through the lens of government communication, a so far under-explored issue in migration studies. Applying qualitative content analysis to two European campaigns, this research finds that the campaigns reiterate immigration policies and portray ambiguity. They therefore raise critical questions regarding the principles of neutrality and reliability in democratic government communication.

Introduction

Attempts to control migration before people’s arrival have been longstanding features of migration management (Pijnenburg et al., Citation2018). Recognizing the vital role of online and social media for people before and during their journey, especially on irregular routes (e.g., Borkert et al., Citation2018), online campaigns that inform (potential) migrants about the risks of irregularity and ‘myths’ about destination countries have become common practices to dissuade irregular migration (Carling & Hernández-Carretero, Citation2011; Nieuwenhuys & Pécoud, Citation2007; Pécoud, Citation2010). For example, since 2017, Germany’s Federal Foreign Office has been running a website and several social media accounts for its campaign ‘Rumours about Germany’ (RAG). Since 2016, the Italian Interior Ministry is funding a campaign implemented by the International Organization for Migration (IOM), again with website and social media presence, entitled ‘Aware Migrants’ (AW).

Such information campaigns for (potential) migrants have received criticism. Their actual impact and effectiveness to reduce irregular migration remain unclear (see Tjaden et al., Citation2018). In some cases, campaigns downplay existing rights to asylum and the provided information align more with restrictive policy interests of destination regions (e.g., Musarò, Citation2019; Nieuwenhuys & Pécoud, Citation2007; Oeppen, Citation2016). These findings provide evidence for a gap between the communicated content (dissuasion, deterrence, deflection) and the explicitly stated goals of such information campaigns (information, awareness-raising).

This criticism is particularly relevant for campaignsFootnote1 that involve (EU) governmental actors since public communication by democratic, ‘good’ governments should be neutral, informative, autonomous of party politics, and not be instrumentalized for political manipulation (Busch-Janser & Köhler, Citation2007; Gebauer, Citation1998). Beyond this purely normative perspective, certain ethical standards are necessary in democratic government communication to promote public engagement and political accountability by informing, explaining, and justifying political decisions (Warren, Citation2014). These “civic purposes” of government communication (Sanders, Citation2019, p. 116), e.g., in public information campaigns therefore require our attention.

Yet, migration research that focuses distinctly on (European) campaigns for potential migrants from a perspective of government communication is so far under-developed. Extant research finds that campaign messages indeed raise questions about principles of ethical public communication in relation to ambiguous migration policy discourses, (e.g., Bishop, Citation2020; Brekke & Thorbjørnsrud, Citation2020; Oeppen, Citation2016), blurring the lines between humanitarianism and securitization (see Chouliaraki & Georgiou, Citation2017). To critically examine this ambiguity in such European governmental campaigns, the article adopts a focus on government communication and asks: How do the RAG and AW campaigns present information for migrants and which types of communicative strategies emerge?

This focus is important because Europe’s so called ‘migration crisis’ in 2015/16 has further increased governments’ willingness to invest in professionalized strategic online communication to implement such campaigns and to address potential migrants directly. Zooming in on the RAG and AW cases as prominent governmental information campaigns, this article employs qualitative content analysis on campaign messages in relation to government communication. With communicative strategies this article refers to the specific themes in campaign messages and their strategic application for the purpose of preventing irregular migration.

The analysis finds that both campaigns amplify the dangers of irregular migration and implicitly shift responsibility to migrants themselves, despite governments’ role in defining irregularity. Instead of informing migrants, these campaigns reiterate European immigration policy discourses and, to an extent, reflect the German and Italian governments’ experiences during the ‘migration crisis’ 2015/16 respectively. The findings also speak to the current research in migration studies that emphasizes an increasing trend toward securitization in international migration governance that is expressed as humanitarianism.

Literature and theory

Information campaigns for migrants are not generally ill-advised. There is considerable evidence suggesting the mushrooming of disinformation among migrants (Carlson et al., Citation2018; Crawley & Hagen-Zanker, Citation2019). Such wrong information is life-threatening.

Yet, one needs to consider whether campaigns with the involvement of governmental actors, via online media, and with the sole purpose to ‘inform’ migrants can provide support for migrants before their arrival in the EU all together. On the one hand, this would require that governments provide trustworthy and reliable information to potential migrants and that migrants are unaware of such risks.Footnote2 So far, however, a common critique of information campaigns is their general effectiveness to reach migrants via online media and convey enough trust to convince people not to choose irregular pathways. On the other hand, the current focus on securitization and externalization in European migration policy approaches raises doubts over the implicit interests in campaigns where EU governments are involved, especially when these campaigns target people before their arrival. The critical issue is then whether governments do what they claim to do: to work in the interest of migrants by informing them about irregular migration or to prevent irregular migration in general. Unpacking this issue, in the following I will first elaborate on the democratic function of government communication in general. I will then discuss the respective literature on current migration management in relation to externalization and dissuasion.

The principles of government communication

In general, trust, transparency, openness or neutrality and the absence of party-political interests have become normative standards to guide democratic governments’ communication with their citizens (Sanders, Citation2019). Public information campaigns are hereby considered policy tools to guide the public which, however, also raise issues in relation to manipulation and accountability (Weiss & Tschirhart, Citation1994). Citizens, in return, can hold governments politically accountable if governments violate these standards (Busch-Janser & Köhler, Citation2007; Gebauer, Citation1998).

The increasing mediatization of politics has forced governments to adapt to online and social media, reallocating resources to professionalize their strategic communication (Sanders et al., Citation2011). Online communication has hereby promised potential for democratic governments to disseminate information, to engage with citizens (Dahlgren, Citation2013) and, generally, to communicate for the purposes of the common good and public well-being (Sanders, Citation2019). With such changing communication patterns and trends, demands on democratic governance to use online and social media ethically and democratically have increased (see DePaula et al., Citation2018).

However, observers remain critical of the impact of internet-enabled government communication for democratic purposes: Research suggest that democratic government actors themselves do not always comply with their own guidelines of ‘good communication’. Instead of dialogue and collaboration with the public, the interaction features on online and social media “can foster ersatz participation” (Zavattaro & Sementelli, Citation2014, p. 262), which merely gives citizens the impression that they are interacting with the government. In this sense, online communication between governments and their audiences looks more like one-to-many communication (Mergel & Greeves, Citation2013), in which governments disseminate information that are in their own interest or, at least, not considered in relation to what is relevant for their citizenry. DePaula et al. (Citation2018, p. 99) argue that a “great portion of government’s use of social media is for symbolic and presentational purposes”. Research shows that (local) governments communicate online for marketing and self-promotion (Bellström et al., Citation2016), similar to the political communication of political parties during election campaigns. The latter form risks to be manipulative if political actors favor political interests over values such as transparency and reliability (Bennett & Manheim, Citation2010, p. 282).

As the existing literature shows, communication principles for democratic governments are not always achievable. This creates challenges for political accountability in the domestic sphere. This problem is amplified when looking at governmental campaigns that address migrants, circumventing the domestic public. Governmental information campaigns for (potential) migrants before their arrival are even more difficult to hold accountable or challenge: Migrants do not hold the same rights toward governments as respective citizens do, and also cannot hold governments accountable through democratic-representative channels, especially not before their arrival.

Inspired by this normative baseline, this research responds to the necessity to critically scrutinize the declared humanitarian aims of these campaigns to inform migrants about the risks of irregular pathways (to inform, empower, support migrants) within the context of current approaches to managing (irregular) migration.

Externalization of migration management: governing migrants through communication?

The control of migration ‘upstream’, i.e., before arrival, “has been a red thread in many policy proposals and implemented measures” (Pijnenburg et al., Citation2018, p. 365). In reaction to the ‘migration crisis’ in 2015/16, many EU governments have unilaterally tightened their migration management to curb (irregular) migration. Externalization of migration control and deportation agreements, such as the EU-Turkey deal, emphasize European moves to further strengthen and police Schengen borders (Mouzourakis, Citation2018). Although the number of asylum applications in Europe have decreased since then, such measures have pressured more people to migrate on unstable boats or rely on ‘smugglers’ to move outside the legally recognized entry points (FitzGerald, Citation2020).

The externalization of migration governance points to a new “deterrence paradigm” in migration management (Gammeltoft-Hansen & Tan, Citation2017; Hathaway & Gammeltoft-Hansen, Citation2014). Dissuasion, deterrence, or deflection are well-known strategies of migration management to control and selectively limit people’s access, for example, by imposing tight regulations to curb immigration of low-skilled migrants and by securitizing migration through a focus on crime and public security measures, thus defining ‘undesired categories’ for irregular migrants (Frelick et al., Citation2016; Horsti, Citation2012; Löfflmann & Vaughan-Williams, Citation2018).

The ‘migration crisis’ in 2015/16 has emphasized the Janus-faced character of European migration management: On the one hand, governments aim to respond to demands to live up to their international responsibilities to protect lives and to show solidarity (Cinalli et al., Citation2021). At the same time, governmental actors further securitize and criminalize migration, and so strengthen the relationship between humanitarianism and security (Perkowski & Squire, Citation2019). According to Vaughan-Williams (Citation2015, p. 3) there is therefore an “inherent ambiguity within EU border security and migration management policies and practices that (re)produces the ‘irregular’ migrant as potentially both a life to be protected and a security threat to protect against”.

Considering the current migration management approach of externalization and securitization, the declared aim of governmental information campaigns to inform migrants and support them in their choices regarding (irregular) pathways needs to be considered with caution. Research shows that communication with migrants in transit or stuck in borderzones follows an “ambivalent moral order that reshapes both Europe’s humanitarian ethics and its politics of security” (see Chouliaraki & Georgiou, Citation2017, p. 160).

Some consider the campaigns as an instrument in governmental actors’ toolbox for externalizing migration (FitzGerald, Citation2020; Van Dessel, Citation2021), blurring humanitarian and securitization discourses. The campaign focus on risks is dissuasive (Carling & Hernández-Carretero, Citation2011; Nieuwenhuys & Pécoud, Citation2007) and undermines the role of rights (Bishop, Citation2020). The intentions of governmental actors in information campaigns are therefore difficult to disentangle: Existing research suggests that campaign messages are implicitly dissuasive, ethically questionable, yet allow governments to appear in a favorable light (e.g., Brekke & Thorbjørnsrud, Citation2020; Oeppen, Citation2016). Furthermore, messages are often based on “strategic omissions” and “strategic ignorance” regarding migrants’ rights and needs (Bishop, Citation2020, p. 1105). At the same time, unauthorized migration is generalized and linked to human trafficking and other forms of organized crime (Nieuwenhuys & Pécoud, Citation2007).

Governmental information campaigns then highlight a mismatch between the explicitly stated campaign aim to inform on the basis of humanitarian purposes to prevent migrants from potentially dangerous situations, and the implicit intention to dissuade the immigration of ‘undesired’ people visible from the actual campaign content. To better understand these more implicit messages of such campaigns, this article empirically investigates campaign messages, arguing that ambiguity between securitization and humanitarianism pose a challenge to the ethical standards of democratic government communication.

Methodology

Background and cases

Empirically, this research focuses on to prominent, highly professional information campaigns in Europe, ‘Rumours about Germany’ (RAG) and ‘Aware Migrants’ (AW). RAG is an information campaign authored and implemented by the German Federal Foreign Office, the foreign ministry of the German government. RAG has been online since 2017. On its website, RAG announces: “The goal of the website is not to deter, but to inform.”Footnote3 The RAG campaign illustrates an explicit form of government communication beyond the domestic sphere, embedded within a branch of the foreign ministry that is concerned with strategic communication abroad.

AW is an information campaign authored and implemented by the IOM Italy branch, “technically and creatively supported” by a communication agency and financed by the Italian Ministry of Interior since its launch in 2016Footnote4, with subsequent support from other European governments, also Germany (IOM Italy, n.d.). The AW campaign declares that its aim is to raise awareness about irregular migration, but also on giving a voice to returned migrants (IOM Italy, n.d.). A share of the posts of the AW campaign contain mainly videos by people who share their horrific migration ‘stories’, representing people without “political agency” (Georgiou, Citation2018, p. 52). The AW campaign was selected because of its visibility and the heavy involvement of government actors, especially Italy. Due to this involvement, the campaign also can be considered as a form of governmental communication, although its implementation is conducted by the IOM as intergovernmental organization.

To analyze the campaign messages and implicit intentions, understanding their political context is important. Governmental campaigns tend to be reactions to increased immigration rates from people with a yet to be determined legal status. For example, information campaigns have already surfaced in Europe during the 1990s, in response to immigration from central and eastern Europe (Nieuwenhuys & Pécoud, Citation2007). The since 2011 steady increase of newcomers in Europe has sparked new initiatives: Between 2015-2019 a bit over 100 campaigns, in which governments are involved, have been launched, with estimated costs around 23 M Euros (European Commission, Citation2018; National Contact Point in the European Migration Network, Citation2019). Due to the high numbers of people arriving in Italy via the Mediterranean Sea between 2014-2016, “images of desperate people clinging precariously to boats became the defining image” for migration during the crisis (Dennison & Geddes, Citation2022, p. 449). Some argue that the EU, by then, had effectively lost control over its outer-EU border since many people entered without a valid visa or being registered in the first country they arrive, as stated by the Dublin regulation (Pries, Citation2020). This regulation implicitly declares countries with outer-EU borders as ‘first arrival countries’, responsible for the organization of asylum-seeking processes and accommodation. The suspension of the Dublin regulation by German Chancellor Angela Merkel in August 2015, i.e., the decision to not close German borders and register people in Germany instead of their ‘first arrival countries’ is now considered as one of the major ‘pull factors’ for (irregular) immigration by some policymakers (Hadj Abdou, Citation2020).

Against this background, both campaigns are appropriate for a case study design, which allows “to aim at an understanding of a complex unit”, instead of producing generally representative results (della Porta, Citation2008, p. 198). Despite their differences in terms of organizational implementation (via an intergovernmental organization of by a ministry itself), their communication forms are similar and embedded within national and European immigration politics.

Both campaigns use main websites which consist of a mix of updating articles and posts directly as well as of links and references to external sources and actors. The website content is further disseminated on different social media platforms. This suggests the centrality of the websites as information platforms. The analysis will therefore focus on these two main websites only. Both RAG and AW are provided in various languages, thus accessible for migrants with different backgrounds. The analysis focused on the English version, given that the content is mostly identical. The analyzed content is publicly available.

Sample and methods

To systematically access the website content, the data collection has been conducted using R (R Core Team, Citation2020), specifically the R package rvest (Wickham, Citation2019). In this way, the entire content of the websites, including posted articles and external links, was collected up until the start of this analysis in April 2020. For the qualitative analysis of campaign messages in the posts the entire sample was screened to check for duplicates, dead links, to assess the types of articles, and so, to set up a subsample focused on written material.Footnote5 In this way, the number of posts was reduced to a manageable size manual in-depth analysis. provides an overview of the sample size.

Table 1. Full Sample.

To analyze how governmental actors communicate information to migrants, the analysis first focused on the external sources, that is, on the kinds of sources that are involved in informing migrants. Analyzing which external sources the campaigns refer to, helped to interpret and to understand which information the authors of the campaigns prioritize and consider relevant for migrants. For the identification of these sources, linksFootnote6 to external sources across all content sites have been explored by employing inductive coding. Inductive coding is helpful as it represents an analysis method in itself (Miles & Hubermann, Citation1994, p. 56). Through heuristic coding of the links (see Saldaña, Citation2021), it was possible to construct categories of external sources to which the campaigns referred to (e.g., websites of other ministries, private business, news media). MAXQDA, a widely adopted software for qualitative analysis, was used for this coding process.

For the analysis of the posts an interpretative approach was chosen. Interpretative qualitative analysis enables to gain in-depth insights into latent meanings and messages, themes, and patterns that quantitative approaches struggle with (Schofield, Citation1993). Interpretivist approaches have been criticized for overemphasizing discourse as symbolic constructions and so for reducing social reality (Iosifides, Citation2018). To balance this criticism, the analysis used word frequencies of the sub-samples as an access point. This overview of the frequency was provided with the help of R’s quanteda package (Benoit et al., Citation2018), for the ‘cleaning’ of the text (tokenization, removal of stopwords, punctuation and symbols, word stemming, transformation to lower case). This first step allowed to systematize the more in-depth, interpretative work (see Jacobs, Citation2018), keeping in mind the differences and similarities of the campaign contents. Via this overview, the main differences and similarities of the campaigns could be described and provided guidance for the manual analysis which concerned close reading and manual coding, using again MAXQDA to identify the emerging themes of both campaigns and to systematize the analysis (see Saldaña, Citation2021). Since the aim of this article is to analyze how the actors behind the campaigns strategically present information for (potential) migrants before their arrival, the main questions for the analysis were: What main themes does each campaign emphasize? How are these main themes applied? For example, for the theme ‘return’, do the campaigns focus on voluntary or forced returns, and in which ways is the theme ‘return’ evoked to inform about risks and dissuade about irregular migration? In other words, the in-depth analysis described and interpreted the campaign messages without taking the themes that emerged for granted, but by interpreting them as strategically used concepts in their overall context.

Analysis

Overall, the analysis finds that the campaigns both amplify the main challenges for people on their way to Germany and Italy during the ‘migration crisis’ in 2015/16 in their information provision to dissuade irregular migration. This amplification is evident, first, in the external sources the campaigns refer to; second, in the overall themes that emerge with RAG focusing on conditionality for access and return and AW highlighting the crossing of the Mediterranean; and third, in the ways in which they apply these themes. For example, entrance requirements are presented as almost impossible to match and irregular migration ending in death and abuse. While these situations speak to the actual social reality of many people trying to reach the EU with Italy and Germany in mind, the campaigns present this social reality as an unavoidable ‘fact’, which turns responsibility on migrants themselves and stylizes EU governments as mere ‘humanitarian’ observers, neglecting their own role in shaping these realities through their policies. These findings then also raise questions over the declared aims of the campaigns to empower migrants and support their decision making.

Sources

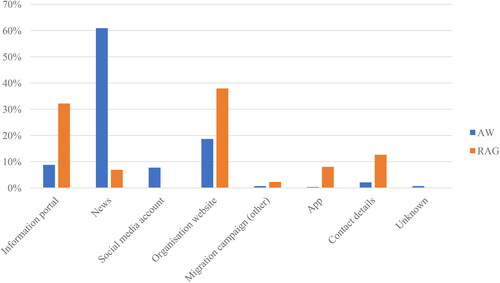

To discern the external sources to which the campaigns refer to on their main websites, the links on the campaign websites connecting to other content beyond the campaigns have been categorized into different types of providing information (). The analysis distinguishes here between links to information portals, to news articles, to social media accounts, to general websites of different organizations, other migration campaigns, apps, and links to emails of specific organizations. The different types provide a first look at how information from external sources is provided.

Information portals describe websites that provide official information in an accessible way, launched often by different ministries and government agenciesFootnote7 for users to navigate different visa options, find helpline contacts or general rules; for example, the ‘VisaNavigator’ of the Germany Foreign Ministry, the portal ‘Returning from Germany’ for people interested in support for voluntary return, or in the case of AW, similar information platforms from other European ministries for immigration, such as Belgium or France. The category ‘organization websites’ describes websites of any kind of organization and is the most general category. We find here, for example, links to the main page of the Finish Immigration Service on the AW campaign.

The RAG campaign refers to organizational homepages and info portals most frequently, but it also refers to migration-specific apps, especially the IOM App ‘MigApp’ and provides contact details. In contrast, the AW campaign refers most frequently to news sources. 60,9% of their external sources link to news articles related to migration issues, followed by general websites (18,7%). The external sources are moreover geographically clustered: the RAG campaign links to mostly domestic external sources, while the AW campaign shares more links from various European organizations.

shows the main categories of actors. The biggest share (more than half: 60,1%) of external sources in the AW campaign is composed of links to media outlets, followed by state institutions (15%). For example, a special section called ‘Regular Channels’ where regular pathways to France, Finland, the Netherlands, Sweden, Belgium, Norway and Italy are presented with links to the respective immigration services websites.Footnote8 This category of actors is followed by links to inter- and supranational institutions (10,1%).

Table 2. Categories of Campaign-External Sources/Actors.

The RAG campaign strongly relies on sources with state involvement: Different ministries from European governments, institutions like the Goethe Institute or the German Society for International Collaboration (GIZ) constitute 60,9% of the external sources, followed by inter- and supranational organizations (29,9%), specifically the IOM and the UN, and media outlets (8%). The other considerable part of organizations linked on RAG are www.deutschland.de, the German government’s foreign public relations website and German ministries, mostly the Foreign Federal Office, as well as other government platforms and agencies (e.g., www.returningfromgermany.de) which promote German business or provide information about ‘opportunities’ to return or start up a business in migrants’ home countries.

These findings suggest that information is presented with an eye on the different migration pathways the Germany and the Mediterranean region, especially Italy. The RAG campaign provides information for migrants who wish to reach Germany as a destination country (see Triandafyllidou & Gropas, Citation2014), focusing on return programs and entry requirements. The Mediterranean region is considered as an arrival region (see Triandafyllidou & Gropas, Citation2014), from which migrants continue their journey to their desired destinations and the AW campaign, led by IOM Italy, provides information in the form of news (), which, as we will see, focus on the dangers of the journey.

The different types of actors to which the campaigns refer to further suggest that information is presented in accordance with the different regions or countries the campaigns represent: The reliance of the RAG campaign on institutions, especially the state, suggests a focus on rules and procedures of migration, which is relevant for a destination country. The AW campaign, instead, indicates a focus on news events. Media coverage, especially in Europe, about what has become popularized as ‘refugee crisis’ in 2015/16 has focused on migration management mainly and contributed to perceptions of crisis and dangers and people’s horrific experiences, often stereotyping migrants as a homogenous group instead of individuals with their own personal stories, circumstances and agency (Brändle et al., Citation2019; Triandafyllidou, Citation2018).

To understand the prominence of news as information sources in the AW campaign but not the RAG campaign, the analysis takes a closer look at the media sources that have used on the campaign websites. They can be divided into three subcategories: International broadcasters and/or state-owned media outlets, private-owned media, and Public Service Broadcaster. The RAG campaign hardly refers to media outlets (8,0%), while the AW campaign links to news articles, mostly from privately-owned media outlets (39,5%), such as the UKs The Independent, or La Repubblica (Italian), but also from news outlets based in or with branches in Senegal, Nigeria or Mali, for example (e.g., Le Quotidien from Senegal, the Nigerian Sun News, Maliweb from Mali) (see ).

Given the in 2017 launched project ‘Engaging West African Communities’ within the AW campaign, this regional focus of news sources is rather unsurprising. A closer look at the respective news articles, however, suggests that they are usually focused on attempted rescue missions in the Mediterranean SeaFootnote9, on death toll on various migrant routesFootnote10, or sexual abuse of women and girls by human traffickersFootnote11. We also find links to economic success stories of people who returned to their home countries or economic possibilities in West African countriesFootnote12.

It is further noteworthy to highlight international broadcasters as sources in both campaigns. International broadcasting is in most cases considered high-quality journalism, yet “its inclusion of international broadcasting into public diplomacy is evident and natural,” which is especially the case “for bigger European countries with languages which serve as languages of wider communication” (Ociepka, Citation2014, p. 88). The investigation finds here that both campaigns draw from the same outlet, InfoMigrants. Despite the RAG campaign hardly referring to news, if it does, it links to a news website called InfoMigrants (6.9%). The AW campaign, though providing a more diverse pool of news sources, also refers frequently to the InfoMigrants website: almost half of the 16.8% of international or state broadcasters is composed of links to this page (see ). On their website InfoMigrants (France Médias Monde et al., Citationn.d.) describe themselves as a “news and information site for migrants to counter misinformation at every point of their journey”Footnote13 and as a

collaboration led by three major European media sources: France Médias Monde […], the German public broadcaster Deutsche Welle, and the Italian press agency ANSA. InfoMigrants is co-financed by the European Union.

Except for ANSA, the other two collaborators of (France Médias Monde and Deutsche Welle) are international broadcasters of European governments, though independent. InfoMigrants therefore also follows the common assumption that migrants are unaware of the risks of irregular migration or uninformed.

Together, the selected news articles, especially in the AW campaign, create a narrative of risk and death, thus mainly reiterating European policy discourses about irregular migration. The various sources the campaigns refer to suggest that information provision is based on relevance for the specific region or country from which the campaigns originate, instead of on relevant sources for migrants themselves. This suggests a strong tendency to promote a ‘bubble’ of governmental information and state-produced migration journalism as well as news about the tragedy of migration toward Schengen countries in European mass media coverage. In this way, the campaigns adopt a humanitarian image, using media outlets as “moral gate keepers” (Wemyss et al., Citation2018, p. 152)

Campaign content

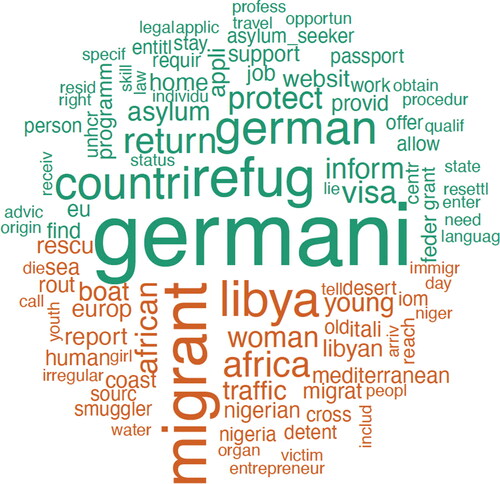

In the next step, the analysis focused on the description and interpretations of the themes that emerge in the campaign posts. provides a comparative overview of the most frequent words used in the posts. Based on these word frequencies, a broad overview can be gained over the different focal points of the two campaigns, indicating dominant themes.

Figure 2. Word cloud comparison of 50 most frequent words (excluding stopwords and stemmed) in the RAG (upper half) and AW (lower half) campaign.

RAG informs frequently about access regulations, entry requirements and return programs, including the refugee status and asylum seeking, thus representing Germany as a destination country with restrictive immigration policies (e.g., ‘germani’, ‘refuge’, ‘return’, ‘asylum’, ‘protect’, ‘visa’). The most frequent words thus indicate a focus on legal procedures and access and return conditions for newcomers in Germany. The focus of the AW campaign is more oriented toward transit and origin countries and focuses on the dangers of the journey (e.g., ‘libya’, ‘african’, ‘woman’, ‘traffic’). This is also supported in the frequent use of the term ‘migrant’ (in comparison to RAG), which signals less focus on legal status but possibly on the act of moving. In this sense, the AW campaign highlights the dangers of migration, especially over the Mediterranean (‘boat’).

In this sense, this overview suggests that both campaigns represent messages that address specific migration patterns in relation to what both countries emphasize when it comes to irregular reception patterns, visible especially during the ‘migration crisis’ in 2015/16: Italy’s experience as a first arrival country for migrants crossing the Mediterranean and Germany’s experience as destination country in hope for a better future with strict conditions for asylum.

To understand both campaigns’ strategies for information provision, the question is then how the campaigns strategically applied these themes to dissuade or prevent irregular migration. The RAG campaign provides information especially about return programs and the general prospects of asylum procedures in relation to employment. It also emphasizes the restrictions for asylum seekers on the German labor market and highlights visa regulations. For example, RAG specifically refers to the German government’s different Assisted Voluntary Return and Reintegration Programs through which the German government supports migrants to return to their countries of origin or other countries, with the IOM as organizing institution of the departure.

Furthermore, the RAG campaign here focuses on the destination, i.e., Germany as an ‘immigration country’ for high-skilled migrants, and the strict requirements to obtain a visa or refugee status there as well as the problems of the German labor market for the low skilled. Issues such as protection, rights, provision of necessary goods, as well as entrance requirements are formulated conditionally, for example: “Even if granted protection, and thus the right to stay, many face difficulties finding work in Germany”Footnote14; or “If you come to Germany and are not entitled to protection and thus, the right to stay, you are required to leave the country immediately”Footnote15; or

There are four forms of protection that grant people a right to stay in Germany. Many migrants who have entered Germany irregularly in search for irregularly in search for work and a better life are surprised to learn that none of these forms of protection apply to them.Footnote16

The AW campaign focuses more strongly on migration routes and the journey, addressing mostly potential irregular migrants from West African countries with low chances of being officially recognized as refugees, people’s horrific experiences, and also focuses on the perspective of migrant women. The AW campaign highlights African origin countries and focuses on the dangers of the journey. Information about people arriving by boat, human trafficking as well as failed rescue missions highlight the risks about migration, while legal procedures, such as information about application forms are missing, e.g., “In the Sicilian port of Pozzallo, a secluded space attracts attention. A cemetery of boats where dozens of boats seized by the authorities are stacked. These broken hulls are those of the dinghy boats used by desperate migrants to come to Europe”Footnote17. Furthermore, the AW campaign provides personal accounts of survivors and people who have economically contributed to African countries with startups or social initiatives, e.g., “I am a good example of one such African scientist who was empowered by the opportunities I have been given”Footnote18; or “Three smugglers carried me to the boat, and I felt my bones moving out of place”Footnote19.

Finally, the analysis also finds that both campaigns treat the issue of migrants’ rights on the margins or conditionally. illustrates that the topic of rights is not featured dominantly: The way in which the RAG campaign articles refer to rights is usually conditional; in the sense, that they inform who has the right to stay in Germany and what happens when this right is not granted. For example, one entire post is dedicated to the right to family reunification and its restrictions.Footnote20 This campaign message is consequently to dissuade people from moving to Germany in the hope of family reunification because of strict requirements. In the AW campaign, the right to apply for asylum is hardly mentioned. Instead, focus is put on human rights violations by traffickers or in reference to UN agencies, emphasizing aspects of criminalization and abuse:

In the center of Al Furahji Sebaa, in Tripoli, where some 330 people are imprisoned, including 56 minors, the migrants sometimes receive no food. According to Giulia Tranchina, a human rights lawyer who contacted several Eritreans in the center, the detainees remained one week without food.Footnote21

This overall tendency potentially contributes to the victimization of people who migrate on irregular pathways, instead of empowering them with relevant information about their rights (see Georgiou, Citation2018). This finding is also in line with other studies on campaign content (e.g., Bishop, Citation2020) and on deterrence strategies (Hathaway & Gammeltoft-Hansen, Citation2014).

We can consequently speak of a conditional, dissuasive take on providing information about migrants’ rights. This type of information poses a challenge to people’s already few opportunities to hold governments accountable for what they tell them. In particular, the latter aspect is problematic since the definition of ‘irregularity’ is based on pathways, not on the person as such (see Frelick et al. (Citation2016) for more information on the rights of ‘irregular’ migrants). These aspects, however, do not become particularly visible in the campaigns and especially the AW campaign, targeting readers from western African countries, omits the aspect of rights in its communication with potential migrants from the region. The campaigns reiterate their own European approaches to migration management by marginalizing the dimension of rights, such as the right to apply for asylum and other social rights and human rights protection, in their information provision.

Discussion: Ambiguity in government communication

The campaign content and reliance on specific sources suggests that government communication with migrants via information campaigns can be considered as reiteration of European immigration policies. They further can be considered as reactions to both countries’ migration reception patterns during the “migration crisis” as elaborated earlier. They consequently reflect the interests of a destination country (here Germany) as well as transit and origin countries (here Italy) regarding irregular migration (see Triandafyllidou & Gropas, Citation2014).

The analysis of campaign messages illustrates the ambiguity between humanitarian and securitization intentions that is prevalent in European migration management (see Chouliaraki & Georgiou, Citation2017), indicating that this ambiguity might be strategically applied through communicative means: Governments – intentionally or not – present themselves as humanitarian-minded bystanders in the face of risk of death on dangerous migration routes. Furthermore, the campaign messages focus on deportation, death/abuse, and crime, thus representing irregularity through a lens of security.

At the same time, they promote an image of migration that can be contained through migrants’ self-responsibility who need information instead of institutional responsibility. On the one hand, according to the authors of/institutions behind the campaigns, the goal is to ‘inform’ potential migrants, thus, to empower them by providing them with relevant information that concern the risks and myths of migration to Europe. On the other hand, these campaigns are authored by parts of the very institutions which decide about who is to be considered ‘desired’ – and will be granted access – and who is not. Through this ambiguity, campaign messages tend to shift responsibility of migration management to potential migrants, who are expected to assess and categorize themselves according to the governmental definition of irregularity and deal with the potential consequences. In this sense, information campaigns for potential migrants carry some of the same risks as campaigns that governments direct at the domestic population. For example, a focus on self-responsibility has also been criticized in government-run campaigns in the domestic sphere regarding awareness about smoking and obesity (see Weiss & Tschirhart, Citation1994).

Nevertheless, information campaigns for potential migrants differ from other government-run campaigns because they target people in immediate, often life-threatening situations in which they urgently require unambiguous information. The mismatch between explicit campaign aims to inform for humanitarian purposes and the implicit reiteration of European immigration restrictions to dissuade potential migrants from specific regions uncovers crucial normative problems regarding the standards of appropriate government communication, especially if one considers its implications on accountability of governments and their communication. The biggest normative question is whether governments are supposed to neatly blend into the diverse pool of migration management actors, as they currently do. The accountability of actors and organizations of migration management is considered problematic and democratic governments have a specific normative function, i.e., that they communicate, inform, and justify their decisions to increase democratic accountability.

Conclusion

To sum, the analysis strongly points to a gap between the publicly declared aim to inform understood in terms of democratic governmental information provision and actual content communicated to migrants: Both campaigns rely heavily on specialized sources to inform migrants and independent news sources are sometimes lacking. Furthermore, in both campaigns the issue of rights is neglected or undermined by information about regular migration channels that are only open to people who fit the desired legal category of high-skilled migrants or people who fall within the category of refugees. In this sense, such campaigns merge into the already existing blend of messages which migrants must navigate and decide whether or not to rely on, for example, from friends and family, NGOs and migration advocacy groups, or other non-state actors. Furthermore, even though some campaigns can be considered “indirect deterrence measures”, they are within the scope of the law (Gammeltoft-Hansen & Tan, Citation2017, p. 38).

The ambiguity that emanates from the campaign messages and that is reflected in European immigration politics seems to justify a certain skepsis: After all, it is no secret that EU governments and the EU have built a restrictive immigration regime beyond the Schengen area. One might therefore wonder whether such campaigns could ever be considered ethically appropriate, even if they contained sufficient and relevant information about access, rights, and support systems alongside realistic warnings about restrictions and dangers. In other words, while information campaigns cannot be understood as communication with malign intentions to simply ‘keep undesired people’ away, their preventive character challenges ethical standards of government communication.

More research is needed that considers governmental actors’ communication with (potential) migrants to understand the implications of online and social media on ethical principles of communication. Research that produces generalizable results with more cases beyond interpretative approaches is needed to carve out the ambiguities in European migration management discourses.

More generally, this article raises questions about communication by different executive organs and institutional actors beyond the domestic sphere. Regarding migration governmental actors’ messages compete with the initiatives of migration advocacy groups and other NGOs ‘on the ground’. The article therefore advocates for a stronger scholarly engagement with government communication that targets migrants. After all, for humanitarian intentions to become credible and be informative for migrants, ambiguity needs to be eliminated and an actual change of policies about irregularity considered.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Olga Eisele, Charlotte Galpin, Hans-Jörg Trenz, Hajo Boomgaarden as well as the two anonymous reviewers for their helpful feedback.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 For legibility the terms ‘governmental information campaigns’/governmental campaigns’ are used to describe campaigns in which governmental actors are openly involved and which address migrants before their arrival. The focus in this paper does not include campaigns by NGOs, campaigns directed at domestic audiences in receiving countries, and initiatives in countries of origin. For a systematic literature review on different forms see Pagogna & Sakdapolrak (Citation2021).

2 The underlying assumptions of such objectives, such as that migrants are unaware of the risks of irregular migration pathways or that they easily believe rumours by traffickers are considered to be controversial, notwithstanding. For a discussion see, for example, Alpes and Sørensen (Citation2015).

5 Posts consisting only of video material were excluded from the analysis.

6 Cross-links within the website were excluded from the analysis.

7 Sometimes supported by communication consulting agencies

References

- Alpes, M. J., & Sørensen, N. N. (2015). Migration risk campaigns are based on wrong assumptions.

- Bellström, P., Magnusson, M., Pettersson, J. S., & Thorén, C. (2016). Facebook usage in a local government: A content analysis of page owner posts. Transforming Government: People, Process and Policy, 10(4), 548–567. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/TG-12-2015-0061

- Bennett, W. L., & Manheim, J. B. (2010). The big spin: Strategic communication and the transformation of pluralist democracy. In Mediated politics (pp. 279–298). Cambridge University Press.

- Benoit, K., Watanabe, K., Wang, H., Nulty, P., Obeng, A., Müller, S., & Matsuo, A. (2018). quanteda: An R package for the quantitative analysis of textual data. Journal of Open Source Software, 3(30), 774. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.21105/joss.00774

- Bishop, S. C. (2020). An international analysis of governmental media campaigns to Deter asylum seekers. In International journal of communication (Vol. 14). http://ijoc.org.

- Borkert, M., Fisher, K. E., & Yafi, E. (2018). The best, the worst, and the hardest to find: how people, mobiles, and social media connect migrants in(to) Europe. Social Media + Society, 4(1), 1–11.

- Brändle, V. K., Eisele, O., & Trenz, H.-J. (2019). Contesting European solidarity during the “refugee crisis.” Mass Communication and Society, 22(6), 708–732. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15205436.2019.1674877

- Brekke, J. P., & Thorbjørnsrud, K. (2020). Communicating borders-governments deterring asylum seekers through social media campaigns. Migration Studies, 8(1), 43–65.

- Busch-Janser, S., & Köhler, M. M. (2007). Staatliche Öffentlichkeitsarbeit — eine Gratwanderung. In Handbuch Regierungs-PR.

- Carling, J., & Hernández-Carretero, M. (2011). Protecting Europe and protecting migrants? The British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 13(1), 42–58. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-856X.2010.00438.x

- Carlson, M., Jakli, L., & Linos, K. (2018). Refugees Misdirected: How Information, Misinformation, and Rumors Shape Refugees’ Access to Fundamental Rights. Virginia Journal of International Law, 57(3), 539–574.

- Chouliaraki, L., & Georgiou, M. (2017). Hospitability: The communicative architecture of humanitarian securitization at Europe’s borders. Journal of Communication, 67(2), 159–180. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/jcom.12291

- Cinalli, M., Trenz, H.-J., Brändle, V. K., Eisele, O., & Lahusen, C. (2021). Solidarity in the media and public contention over refugees in Europe. Routledge.

- Crawley, H., & Hagen-Zanker, J. (2019). Deciding where to go: Policies, people and perceptions shaping destination preferences. International Migration, 57(1), 20–35.

- Dahlgren, P. (2013). The political web: media, participation and alternative democracy. Palgrave Macmillan.

- della Porta, D. (2008). Comparative analysis: Case-oriented versus variable oriented research. In D. della Porta & M. Keating (Eds.), Approaches and methodologies in the social sciences (pp. 198–222). Cambridge University Press.

- Dennison, J., & Geddes, A. (2012). The centre no longer holds: the Lega, Matteo Salvini and the remaking of Italian immigration politics. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 48(2), 441–460.

- DePaula, N., Dincelli, E., & Harrison, T. M. (2018). Toward a typology of government social media communication. Government Information Quarterly, 35(1), 98–108. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2017.10.003

- European Commission. (2018). Managing migration in all its aspects: Progress under the European Agenda on migration. In COM(2018), 798 final.

- FitzGerald, D. S. (2020). Remote control of migration. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 46(1), 4–22. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2020.1680115

- France Médias Monde, Deutsche Welle, & ANSA. (n.d.). InfoMigrants. France Médias Monde. Retrieved December 3, 2020, from https://www.infomigrants.net/en/

- Frelick, B., Kysel, I., & Podkul, J. (2016). The impact of externalization of migration controls on the rights of asylum seekers and other migrants. Journal on Migration and Human Security, 4(4), 190–220. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/233150241600400402

- Gammeltoft-Hansen, T., & Tan, N. F. (2017). The end of the deterrence paradigm? Future directions for global refugee policy executive summary. Journal on Migration and Human Security, 5(1), 28–56. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/233150241700500103

- Gebauer, K.-E. (1998). Regierungskommunikation. In O. Jarren, U. Sarcinelli, & U. Saxer (Eds.), Politische Kommunikation in der demokratischen Gesellschaft (pp. 464–472). VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

- Georgiou, M. (2018). Does the subaltern speak? Migrant voices in digital Europe. Popular Communication, 16(1), 45–57. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15405702.2017.1412440

- Hadj Abdou, L. (2020). Push or pull’? Framing immigration in times of crisis in the European Union and the United States. Journal of European Integration, 42(5), 643–658. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2020.1792468

- Hathaway, J. C., & Gammeltoft-Hansen, T. ( (2014). ). Non-refoulement in a world of cooperative deterrence (No. 14–016; Law and Economics Research Paper Series).

- Horsti, K. (2012). Humanitarian discourse legitimating migration control: FRONTEX public communication. In Migrations: Interdisciplinary perspectives (pp. 297–308). Springer.

- IOM Italy (n.d). Aware migrants. Organizzazione Internazionale per Le Migrazioni. Retrieved December 3, 2020, from https://italy.iom.int/en/aware-migrants

- Iosifides, T. (2018). Epistemological issues in qualitative migration research: Self-reflexivity, objectivity and subjectivity. In R. Zapata-Barrero & E. Yalaz (Eds.), Qualitative research in european migration studies (pp. 93–109). Springer.

- Jacobs, D. (2018). Categorising what we study and what we analyse, and the exercise of interpretation. In R. Zapata-Barrero & E. Yalaz (Eds.), Qualitative research in european migration studies (pp. 133–149). Springer.

- Löfflmann, G., & Vaughan-Williams, N. (2018). Vernacular imaginaries of European border security among citizens: From walls to information management. European Journal of International Security, 3(03), 382–400. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/eis.2018.7

- Mergel, I., & Greeves, B. (2013). Social media in the public sector field guide: Designing and implementing strategies and policies. Wiley.

- Miles, M. B., & Hubermann, A. M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis (2nd ed.). Sage.

- Mouzourakis, M. (2018). Access to protection in Europe Borders and entry into the territory.

- Musarò, P. (2019). Aware migrants: The role of information campaigns in the management of migration. European Journal of Communication, 34(6), 629–640. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0267323119886164

- National Contact Point in the European Migration Network. (2019). Migration and communication: information and awareness campaigns in countries of origin and transit [Paper presentation]. Austrian National EMN Conference 2019 – Briefing Paper.

- Nieuwenhuys, C., & Pécoud, A. (2007). Human trafficking, information campaigns, and strategies of migration control. American Behavioral Scientist, 50(12), 1674–1695. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764207302474

- Ociepka, B. (2014). International broadcasting: A tool of European public diplomacy?. In A. Stepinska (Ed.), Media and communication in Europe (pp. 77–89). Logos.

- Oeppen, C. (2016). Leaving Afghanistan! are you sure?” European efforts to deter potential migrants through information campaigns. Human Geography, 9(2), 57–68. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/194277861600900206

- Pagogna, R., & Sakdapolrak, P. (2021). Disciplining migration aspirations through migration‐information campaigns: A systematic review of the literature. Geography Compass, 15(7), 1–12. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/gec3.12585

- Pécoud, A. (2010). Informing migrants to manage migration? An analysis of IOM’s information campaigns. In M. Geiger & A. Pécoud (Eds.), The politics of international migration management (pp. 184–201). Palgrave Macmilan.

- Perkowski, N., & Squire, V. (2019). The anti-policy of European anti-smuggling as a site of contestation in the Mediterranean migration ‘crisis. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 45(12), 2167–2184. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2018.1468315

- Pijnenburg, A., Gammeltoft-Hansen, T., & Rijken, C. (2018). Controlling migration through international cooperation. European Journal of Migration and Law, 20(4), 365–371. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1163/15718166-12340034

- Pries, L. (2020). We will manage it” – Did chancellor Merkel’s dictum increase or even cause the refugee movement in 2015? International Migration, 58(5), 18–28. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/imig.12684

- R Core Team (2020). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. In R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing.

- Saldaña, J. (2021). The coding manual for qualitative researchers (4th ed.). Sage.

- Sanders, K. (2019). Political public relations; concepts, principles, and applications. In Political public relations: Concepts, principles, and applications (2nd ed.).

- Sanders, K., Crespo, M. J. C., & Holtz-Bacha, C. (2011). Communicating governments: A three-country comparison of how governments communicate with citizens. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 16(4), 523–547. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161211418225

- Schofield, J. W. (1993). Increasing the generalizabiltiy of qualitative research. In M. Hammersley (Ed.), Social research: Philosophy, politics and practice (pp. 200–225). Sage.

- Tjaden, J., Morgenstern, S., & Laczko, F. (2018). Central Mediterranean route thematic report series evaluating the impact of information campaigns in the field of migration: A systematic review of the evidence, and practical guidance.

- Triandafyllidou, A. (2018). A “refugee crisis” unfolding: “Real” events and their interpretation in media and political debates. Journal of Immigrant and Refugee Studies, 16, 1–2.

- Triandafyllidou, A., & Gropas, R. (2014). European immigration: A sourcebook. In European immigration: A sourcebook.

- Van Dessel, J. (2021). Externalization through ‘awareness-raising. Territory, Politics, Governance, 0(0), 1–21. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/21622671.2021.1974535

- Vaughan-Williams, N. (2015). Europe’s border crisis. Oxford University Press.

- Warren, M. E. (2014). Accountability and Democracy. In M. E. Bovens, R. E. Goodin, & T. Schillemans (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of public accountability (pp. 39–54). Oxford University Press.

- Weiss, J. A., & Tschirhart, M. (1994). Public information campaigns as policy instruments. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 13(1), 82–119. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/3325092

- Wemyss, G., Yuval-Davis, N., & Cassidy, K. (2018). Beauty and the beast’: Everyday bordering and ‘sham marriage’ discourse. Political Geography, 66, 151–160. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2017.05.008

- Wickham, H. (2019). rvest: Easily harvest (scrape) web pages. In R package version 0.3.5. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=rvest

- Zavattaro, S. M., & Sementelli, A. J. (2014). A critical examination of social media adoption in government: Introducing omnipresence. Government Information Quarterly, 31(2), 257–264. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2013.10.007