Abstract

In this paper, we argue in favor of expanding the reflexive turn in Migration Studies, which has neglected migratory phenomena in the Global South, to political migration research on Latin America. The existing literature has pointed to exceptional generosity in the region’s immigration legislation, especially regarding refugee protection, migrant regularization, and naturalization. In parallel, policy implementation gaps and restrictive shifts persist in these areas. Departing from our research on these issues over the past 15 years, we critically discuss implementation, research gaps, and data accessibility in the abovementioned areas. Focusing on Venezuelan displacement, we further point out critical questions for future research from a reflexive perspective.

Introduction

Migration Studies have gained increasing academic and socio-political importance and recognition in the past decades. In this context, scholars began to pay attention to how knowledge on migration is produced, circulated and utilized by researchers, (non)-governmental and international actors, and the media (Amelina, Citation2021). The reflexive turn in Migration Studies looks to address the risk of reproducing hegemonic structures and problem definitions to develop alternatives in theory, empirical research and science-society dialogues, including the development of alternative conceptual vocabularies (see Imiscoe, Citation2022).

In other words, the reflexive turn in Migration Studies asks which migration-related categories, narratives and data are produced and used by actors, including academics and international organizations, why, and to which effect. This includes asking why migration is often presented in politics, the public, or media as a direct threat to sovereignty, national interests, or security and how scholarship can resist contributing to these dynamics. Reflexivity also entails questioning whether migrants and refugees are à priori and per se distinct from other people or whether we should study migration-related phenomena from broader theoretical perspectives (see Imiscoe, Citation2022), such as inequality, discrimination, or legal precarity.

This reflexive turn has been rooted in work on ethnic groupism and solidarity by Brubaker (2002); methodological nationalism by Wimmer and Glick Schiller (Citation2002); the naturalization of borders, of structure over agency, and of sedentarism over mobility (Hess, 2012; Papadopoulos and Tsianos, Citation2013); the artificial separation between forced refugees and other displaced migrants (Koch 2013); the construction of migration “crises” (Menjívar et al., Citation2018); the securitization of migration (Bourbeau, Citation2013); as well as critiques of the dominant androcentric bias that largely ignores the complexity of migrant’s experiences along various ‘axes of inequality’ such as gender, class, and ethnicity/race (Anthias, Citation2013), among others.

To adopt a reflexive lens on migration policies, scholars must consider relevant institutional definitions of key categories and the discursive knowledge they carry and “how specific configurations of discursive knowledge become inscribed in the organizational and institutional routines of migration and integration policies” (Amelina, Citation2021, p. 2), and importantly, investigate the effects of knowledge production on policy. Dahinden et al. (Citation2021) further argue that institutionally or publicly naturalized categories are often contested, negotiated, and navigated in multiple ways by migrants and refugees themselves. Giving a voice to such contestations by ‘research subjects’ can help overcome issues of legitimacy, representation, and power relations in scientific knowledge production.

It is somewhat curious that the reflexive turn in Migration Studies mirrors the South-North bias in the literature in that such studies have focused on critical epistemological approaches to migration phenomena in the Global North. To help mend this gap, this paper explores reflexive approaches to studying migration in Latin America, particularly in refugee protection, regularization, and naturalization. In this context, the region is of specific interest, as it has, by and large, resisted restrictive global trends in both public discourses and migration governance over the past two decades with contrasting and exceptional policy liberalization (Acosta Citation2018; Cantor et al., Citation2015).

The philosophical and legal paradigm shift in Latin American migration governance was based on the principle of migrants’ human rights (Acosta & Freier, Citation2015; Hammoud-Gallego & Freier, Citation2022; Melde & Freier, Citation2022). Liberalization included the adoption of expanded refugee definitions—and complementary protection, such as for those affected by climate crises - in domestic legislation (Freier & Gauci, Citation2020); the non-criminalization of irregular migrants and a consequent emphasis on regularization; the recognition of migration as a fundamental right, and thus the right of dual citizenship and, theoretically, granting migrants and refugees the same right as nationals (Acosta, Citation2018); and the incorporation of nondiscrimination and special protection clauses in both immigration and refugee laws (Freier et al., Citation2022). In practical terms, the displacement of six million Venezuelan citizens in the region (R4V, Citation2022) put these progressive laws to the test. Although policy reactions fell short of adequately implementing progressive legal provisions and oscillated between protection and exclusion (Acosta et al., Citation2019; Freier & Doña-Reveco, Citation2022; Gandini et al., Citation2020; Jubilut et al., Citation2021), they were innovative and generous in international comparison.

From a reflexive perspective, the region thus offers unique opportunities to study, on the one hand, when, why and how migration in politics is understood as an opportunity and how it can be analyzed in such favorable terms without reproducing narratives of domestic crisis and national security threats. At the same time, the region presents ample opportunity to understand better the turning points, or critical junctures, when such positive narratives flip, and migration becomes securitized and depicted as a threat and a national crisis.

Furthermore, restrictive policies and implementation gaps, both in the context of the Venezuelan and Central American displacement, and transmigration from Africa and Asia (Acosta & Freier, Citation2015; Finn & Umpierrez de Reguero, Citation2020; Sánchez Nájera and Freier, 2021) allow us to gain a better understanding of the (limited) effect of more positive public narratives on actual policy implementation, as well as the differentiation of such policy implementation between ethnically, culturally and socio-economically diverse groups of migrants. In Mexico, specifically, various administrations developed political narratives that focused on the protection of migrants and their human rights, but policy implementation has concentrated on containment in line with US interests (Calderón Chelius, Citation2021; Calva Sánchez & Torre Cantalapiedra, Citation2020; Sánchez Nájera, Citation2020). These implementation gaps thus invite us to develop intersectional approaches to studying migration governance in the region, adopting broader critical socio-political lenses, such as inequality, (institutional) racism and aporophobia. This is particularly salient in the ongoing COVID pandemic and its economic effects, which influence migration governance (Jubilut et al., Citation2021; Acosta & Brumat, Citation2020).

A reflexive approach necessarily implies an intersectional approach. For example, the intersectionality of identifying as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer or intersex (LGBTQI+) and working-class intensified the vulnerability to violence and discrimination of displaced Venezuelan women in Colombia, Ecuador and Peru during the pandemic, which was also shaped by their condition as (irregular) migrants, their age and race (Freier et al., Citation2022). Indeed, Latin America is a region especially worth analyzing to understand the intersection between gender, race relations and immigration policies, as gender, racial and ethnic discrimination continue to be polarizing socio-political issues (Wilson, Citation2014; Wade, Citation1997).

To show the importance of adopting more reflexive approaches to studying Latin American migration governance—as well as the practical significance of the region for advancing reflexivity in Migration Studies—in this paper, we first identify implementation gaps in three main migration policy areas: refugee protection, migrant regularization, and naturalization. Second, we ask what kind of data is available and should be made available to deepen our understanding of these implementation gaps. Third, we suggest how to adopt a more reflexive stance in studying these issues, with a particular focus on Venezuelan forced displacement. Relatedly, we delineate topics that merit further scholarly inquiry. Refugee protection, regularization, and naturalization represent three crucial elements in the governance of human mobility, in general, and in Latin America in particular, given the region’s expanded scope of refugee protection, the principle of non-criminalization of irregular migrants, and the concept of a universal right to migrate discussed above.

Toward reflexivity in Latin American migration policy studies

Latin American migration governance literature has advanced substantially in the past decade. However, certain shortcomings remain. The literature initially focused on descriptive, normative analyses of migration and refugee laws and social norms and neglected policy implementation (Fernández Rodríguez et al., Citation2020). Despite a few earlier exceptions (Acosta & Freier, Citation2015; Domenech, Citation2013), a more explicit focus on implementation gaps and the framing of displacement as “crises” only emerged in the context of Venezuelan displacement. Reflexive studies in the region are largely lacking, except for studies on increasing socio-political criminalization of Venezuelan migration and related media narratives, which arguably take an implicitly reflexive stance (see Bahar et al., Citation2020; Finn & Umpierrez de Reguero, Citation2020; Santi, Citation2020; Santi Pereyra, Citation2018; Stang, Citation2016; Pineda & Ávila, Citation2019).

Adopting such reflexive approaches to studying Latin American migration governance is essential in three key areas. First, the UNHCR considers Latin American countries to be at the forefront of international refugee protection (Freier, Citation2015; Freier & Gauci, Citation2020). Except for Cuba, all Latin American countries have ratified the 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees and its 1967 Protocol. Furthermore, fifteen1 countries in the region have included the Cartagena refugee definition, which extends the scope of protection to incorporate those fleeing because their lives, safety or freedom have been threatened by generalized violence, foreign aggression, internal conflicts, massive violation of human rights, or other circumstances that have seriously disturbed public order.2 Initially a non-legally binding document, the Declaration also gained traction with its incorporation into the jurisprudence of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights (IACtHR).3 Developing a reflexive approach to studying refugee protection in the region is crucial to understand better the relevance and shortcomings of the region’s expanded scope of protection and the socioeconomic rights extended to asylum seekers and refugees in the context of the region’s ideational focus on migrants’ rights.

Second, advancing a reflexive understanding of regularization processes in the region is particularly important against the background of the principle of non-criminalization of irregular migrants. Regularization offers the person concerned the possibility to obtain a residence permit and, thus, access to a more significant number of rights since many entitlements are only available to those regularly residing in a country. Moreover, undocumented migrants may, with limited exceptions, be expelled simply because of the irregularity of their stay. Furthermore, in the case of Latin America, in practice, refugee protection and regularization are intrinsically related. This is illustrated by the legal responses to the arrival of Venezuelan nationals. Rather than offering them refugee status under the Cartagena Declaration, most countries have opted for regularization processes through which de jure refugees have been provided temporary residence permits rather than asylum. A reflexive approach invites us to engage with these categorizations critically, asking how they emerged and why, and to what effect.

Lastly, developing a reflexive approach to studying naturalization allows us to engage seriously with the recognition of the universal right to migrate, which should facilitate the acquisition of (dual) citizenship. Naturalization represents the last legal step in any migration journey. It dissolves the difference between migrants and refugees as foreigners and nationals of a country, precluding any de jure legal discrimination. However, there are significant exceptions in all Latin American legal systems since all include distinctions in treatment between so called naturals—those who became nationals at birth—and naturalizados—those who went through a naturalization process to obtain nationality. The latter are generally discriminated against when exercising certain political rights or access to public sector jobs, often in the legislature, executive, and judiciary (Acosta Citation2018).

Refugee protection

As pointed out above, in Latin America, those who flee their country and fall under the definition of refugee enshrined in the Geneva Convention of 1951, or the expanded definition under the Cartagena Declaration of 1984, are considered refugees. In practice, however, except for Ecuador (Meili, Citation2018; UNHCR, Citation2020), no Latin American country had received significant numbers of asylum seekers until the onset of the Venezuelan displacement in 2015. Indeed, legislative refugee reforms occurred in the absence of mass displacement, at a time when migration and especially refugee protection were non-salient political issues. In the context of leftist ideological convergence of governments in the region and their increased political and economic integration, they adopted similar standards of refugee protection for largely symbolic reasons to highlight their ideological commitment to human rights more broadly (Hammoud-Gallego and Freier, Citation2022).

In the context of the Venezuelan displacement crisis, various governments in the region have called Venezuela an ‘illegitimate and dictatorial regime’ where ‘human rights are systematically violated’4, theoretically obliging them to protect Venezuelans as refugees according to their refugee laws. Venezuelan displacement indeed meets three of the criteria established in the Cartagena Declaration, namely, generalized violence, massive violation of human rights and other circumstances seriously disturbing public order (Freier et al., Citation2022), which has led the UNHCR to declare repeatedly that most Venezuelans should be granted refugee status (UNHCR, 2018, Citation2019). Although fifteen countries in Latin America adopted the Cartagena definition into their domestic laws and leading bureaucrats in the region’s refugee agencies recognize the applicability of the Cartagena refugee definition, only Brazil and Mexico have applied this definition to a significant number of Venezuelan citizens (Freier et al., Citation2022).5 Instead, most host countries developed ad hoc policy responses that have been highly dependent on the number of Venezuelan immigrants and refugees present (Acosta et al., Citation2019), often offering them short-term permits, such as the Special Permanence Permit (PEP) in Colombia and the Temporary Permanence Permit (PTP) in Peru. After increasing numbers and rising xenophobia, the region’s initial generosity shifted toward restrictive policy reactions and de facto border closures toward Venezuelans (Freier & Doña-Reveco, Citation2022). One noteworthy exception is the Colombian Temporary Protection Status (TPS). The TPS offers Venezuelan citizens regular status and documentation for ten years, the opportunity to integrate into the formal job market, and full access to public services. It is a laudable pragmatic policy approach that has dramatically improved the lives of Venezuelans residing in Colombia; yet it undermines Colombia’s national and Latin America’s regional refugee protection regime (Freier & Gomez García, Citation2022; Selee & Bolter, Citation2021).

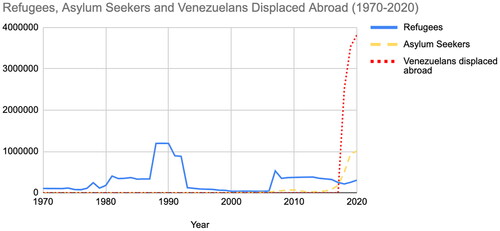

In categorical terms, this dilemma is reflected in the UNHCR’s creation of the new category “Venezuelans displaced abroad”, which was first introduced in its 2019 Global Trends Report (Freier, Citation2022). Acknowledging the large percentage of Venezuelans who stay in their host countries but remain outside of the asylum system, the UNHCR sees “Venezuelans displaced abroad” as entitled to international protection under the criteria contained in the Cartagena Declaration. However, they are not officially counted as asylum seekers, refugees or “others of concern to the UNHCR”, the traditional UNHCR labels (ibid.).

In the case of refugee protection, data is more easily accessible than in the areas of migrant regularization and naturalization, given that international organizations and platforms, UNHCR and the Regional Interagency Coordination Platform for Refugees and Migrants from Venezuela (R4V) compile data on asylum applications and application outcomes, although with some delay and discrepancies in comparison to data provided by national refugee agencies. In June 2021, there were over 750,000 pending asylum claims by Venezuelans in the region (compared to 14,000 in Spain and 230,000 in the US), and only 85,000 recognized refugees (compared to 84,000 in Spain and 18,000 in the US) (R4V, Citation2022). not only exemplifies the significance of Venezuelan displacement from a historical perspective but the scale of the category “Venezuelans displaced abroad”, e.g. Venezuelans that have not applied for asylum vis-à-vis asylum seekers and refugees.

Figure 1. Refugees, asylum seekers and “Venezuelans displaced abroad” in Latin America (1970–2020).

Source: UNHCR data, author elaboration, see Freier (Citation2022.)

From a reflexive perspective, it is vital to question the categories used by international organizations and, specifically, the creation of the new category “Venezuelans displaced abroad” by UNHCR and its impact on political narratives, policy options and implementation. Exploratory research based on interviews with NGO, IO and state representatives in Peru suggests that the term creates confusion and that labeling Venezuelans as refugees would have put more pressure on both receiving states and the international community to offer Venezuelans sustainable protection and integration (Freier, Citation2022).

The complexities of Venezuelan categorization processes are connected to the ever-present debate over the separation of migrants and refugees. Should the category migrant include all forms of mobility, or should it exclude those forced to move? This question is crucial, as the use of categories (e.g. migrants, refugees or “Venezuelans displaced abroad”) in academic and policy circles profoundly shapes understandings of human mobility, and informs the development and implementation of policies, as well as the rights and protections granted, which impact individuals’ livelihoods and wellbeing across the migratory process. Western host countries tend to conceptualize migrants and refugees as distinct categories, often portraying migrants negatively and prioritizing the protection of refugees (Zetter, Citation2007; Mourad & Norman, Citation2020). In Latin America, however, the line between the two categories is more blurred in practice due to limited state capacity and political calculations, and refugee status does not always imply greater protection (Freier & Doña-Reveco, Citation2022).

While the significant increase in asylum applications can help explain the collapse of some of the region’s refugee systems, there are other reasons for the lack of recognition of Venezuelans as refugees, which is highly relevant from a reflexive perspective: the apparent lack of self-identification as such. Only a relatively small number of Venezuelans have filed asylum applications in the region. In the context of the lack of their categorization as refugees, this may result from an information gap, meaning Venezuelans may not know that the Cartagena refugee definition applies to them.6 However, it may also be due to how displaced Venezuelans interpret their social position and its meaning. Identifying as ‘vulnerable’ refugees in societies where many Venezuelans feel ‘superior’ vis-à-vis their host societies in socioeconomic and racial terms might lead to a perceived status loss which they seek to avoid (Freier & Bird, Citation2021).

More research on Latin American refugee protection is thus needed regarding at least two aspects. First, the motivations and criteria that led some countries to offer refugee protection under Cartagena to certain applicants, and not others (Acosta & Sartoretto, Citation2020; Ochoa, Citation2020; Sánchez Nájera & Freier, Citation2022), ideally taking an intra-regional, comparative perspective. While recent research has provided comparisons between Latin America and, for example, the EU (Freier & Gauci, Citation2020; Hammoud-Gallego, Citation2022) and highlighted the progressiveness of refugee legislation in the region, there is not yet enough systematic analysis of the implementation of the Cartagena Declaration refugee definition across the region. At the same time, we need to continue to deepen our understanding of how political actors understand and reproduce categories of migrants, refugees, and “Venezuelans displaced abroad” in national and local policy processes, in how far international narratives and concepts shape these understandings, and how they influence or determine policy choices (see Freier, Citation2022). Given that increasing numbers of African and Asian migrants and refugees are arriving in the region (Yates, Citation2019), such studies must take intersectional critical approaches, considering (institutional) racism and aporophobia.

Second, we need to better understand the self-identification process as migrants or refugees and in how far such self-identification influences the ability to access the rights to which refugees are entitled on paper. For example, Freier and Bird’s (Citation2021) findings imply that displaced Venezuelans have nuanced perceptions of their migratory condition. Although almost all Venezuelans surveyed self-identified as migrants and saw their migration as necessary for survival, less than half identified their migration as forced. While a reflexive approach to these findings necessarily needs to consider power relations between the interviewers and the interviewees that might influence responses on self-identification, they suggest that the classification of human mobility into neat categories is problematic. Treating the categories of voluntary migrants and forced refugees as separate and unrelated may even be exacerbating the lack of recognition and of protection that displaced Venezuelans are receiving. Including the voices of Venezuelans regarding their self-identification can contribute to broader debates on migrant categorizations, remedying the related lack of legitimacy and migrant representation.

Migrant regularization

The topic of irregular migration represents a central concern in Latin America. On the one hand side, there is an ongoing preoccupation with the rights of Latin Americans who find themselves in an undocumented situation in the EU or the US (Góngora-Mera et al., Citation2014). On the other hand, and indeed relatedly, the principle of non-criminalization of irregular migration has gained strength across the region, especially in the last 15 years. First spelt out in the 2006 South American Conference on Migration (SACM) meeting,7 the principle gained traction in 2008, which coincided with the adoption of the EUs Returns Directive (Acosta, Citation2009). Ahead of the Global Forum on Migration and Development, that same year, the Ministers of Interior of the MERCOSUR and Associate States, emphatically rejected the criminalization of irregular migration and called on receiving countries to implement regularization policies.8

The regional exhortation to the Global North to regularize Latin American nationals and the centrality of the non-criminalization principle continued to be pushed in different policy fora in the following years.9 The principle of non-criminalization was a central element in migration law reforms across the region,10 with Ecuador going as far as declaring, in Article 40 of its 2008 Constitution, that “no human being shall be identified or considered as illegal because of his/her migratory status.” If we assume that policy responses to irregular migration should be based on its non-criminalization, from a normative perspective, regularization must play a central role in policy formulation. Indeed, Latin American countries, particularly South America, have reached a consensus that regularization is the proper response to undocumented immigration.11

At the legal level, this policy principle has been pursued in three different ways. First, implementing the 2002 MERCOSUR Residence Agreement in nine countries has established a permanent procedure for the nationals of the countries involved –all except Guyana, Suriname, and Venezuela– to obtain a two-year temporary residence permit, and thus to regularize if being undocumented. Second, 13 countries in Latin America have established permanent regularization mechanisms in their laws (Acosta & Harris, Citation2022). Argentina was the first country in the region to develop such a mechanism in 2004, serving as a model for others. Once the irregular situation of an individual is identified, the Argentine National Migration Directorate is obliged to request them to regularize within thirty and sixty days. During that period, migrants may invoke one of the categories leading to a residence permit under Article 23 of the law; for example, having a binding job offer. Third, regularization programs have become a standard policy tool (Acosta Citation2018; Bauer, Citation2021). Whilst regularization mechanisms are enshrined in the law and thus theoretically available to all those who fulfill certain conditions at any point, regularization programs refer to specific procedures running for a limited period, often adopted by executive decrees. Latin American countries have adopted more than 90 such programs since 2000 (Acosta & Harris, Citation2022), some of which have had broad reach, while others were limited to particular nationalities or groups of individuals.

These regularization programs have not been the subject of empirical, comparative, or critical studies, regarding their implementation and consequences. These lacunae in the literature are particularly problematic given the magnitude of the Venezuelan exodus. As of November 2022, of the 7.1 million displaced Venezuelans in the world and 6 million in the region, only 2.4 million Venezuelans had residence permits, including 970.000 asylum seekers and 199.000 refugees (R4V, Citation2022). Citing some national examples, out of the 1.75 million Venezuelans living in Colombia by June 2020, only 44 per cent had a residence permit (Presidencia de Colombia, Citation2020, p.13). In the case of the Dominican Republic, out of the estimated 114 thousand residing in the country by August 2020, only 7,946 had a residence permit (UNHCR, 2021).12 As mentioned above, Colombia implemented the TPS for migrants, granting Venezuelans a ten-year temporary residence permit.13 In turn, the Dominican Republic started a regularization procedure in 2021 for those who entered between January 2014 and March 2020.14 Such regularization efforts contrast with the trend of growing irregularity due to increasing restrictions in many other countries, including the stark increase of irregular flows through the deadly Darien gap (UNHCR, Citation2022).15

Overall, we know very little about the number of individuals who obtain a residence permit through regularization mechanisms or about rejection rates and their determinants. Consequently, the fact that migration is not criminalized does not mean that migrants can claim access to a residence in an efficient manner (Rathod, Citation2018). In countries like Ecuador, the constitutional enunciation that no human being can be considered illegal has not led to higher residence permit rates (Álvarez Velasco, Citation2020; Freier et al., Citation2019). Similar outcomes have been observed in countries like Chile (Dufraix Tapia et al., Citation2020). Moreover, as shown in the Mexican case (Basok & Rojas Wiesner, Citation2018), the status obtained through regularization procedures can be precarious, and the transition toward regular residence reversible.

The misalignment between legislation and policy implementation points to at least three research areas. First, there is the need to compile disaggregated data on the implementation of each regularization program and mechanism, including the numbers, nationalities, and socioeconomic characteristics of those who obtain residence or are rejected. The region has increased the number of extraordinary regularization programs during the last decade, particularly in the last five years coinciding with the arrival of an important number of Venezuelans (Acosta & Harris, Citation2022). Whereas statistical information has been collected for some of the most recent extraordinary regularizations, the same is not true for previous programs (Alfonso Citation2013). As in refugee protection, taking a reflexive turn to the study of migrant regularization would also mean adopting broader socio-political lenses, such as institutional racism and aporophobia, to understand the mechanisms behind acceptance and rejection patterns. Collecting better data further aligns with objective 1 of the Global Compact on Migration which most countries in the region have endorsed.

Second, scholars should pursue a comparative analysis of the legal and other (e.g. financial) barriers that make some of these regularization mechanisms inaccessible for many migrants. For example, in Argentina, those who enter the country irregularly cannot avail themselves of the permanent mechanism to obtain a residence permit due to such clandestine entry (Acosta & Freier, Citation2015). Indeed, the introduction of visa requirements for Venezuelans in various countries, namely, Chile, the Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, Panama, and Peru, and in early 2022 Mexico, has aggravated the magnitude of irregularity in the region. In this context, the link between visas and irregularity merits further attention. While some authors have started to analyze how restrictive visa policies can be barely counteracted by extraordinary regularization processes, particularly in countries like Chile (Finn & Umpierrez de Reguero, Citation2020), Ecuador (Ramírez, Citation2020), or Peru (Freier & Luzes, Citation2021), there is more research needed on how irregularity is reproduced through visa regimes (see Domenech & Dias, Citation2020).

Third, we must deepen our understanding of how political actors understand and reproduce categories of regular and irregular migrants. Here, scholars should inquire in how far they relate the ideal of nondiscrimination of irregular migrants with the need for regularization, and how international norms shape understandings of migrant irregularity and deservingness (Chauvin and Garcés-Mascareñas, Citation2014).

Naturalization

Unconditional ius soli has historically been the predominant form of gaining nationality at birth in Latin America, with only two exceptions. In Colombia, its 1886 Constitution ended the absolute ius soli tradition, making the country an anomaly in the region. More recently, in 2013, the Dominican Republic’s Constitutional Tribunal adopted a ruling that retroactively deprived thousands of Dominican birthright citizens with Haitian ancestry of their nationality. The illegality of this measure, from an international and rule of law perspective, and the consequences of this process, have been well plotted in recent literature (Hayes de Kalaf, Citation2021; Sagás Citation2017). Lastly, Chile has debated the nationality of those born in the country whose parents were ‘in transit’ (transeúnte). The Supreme Court has confirmed that parents residing in the country without a regular permit could not be considered ‘in transit’, thus their offspring were entitled to Chilean nationality (Dirección de Estudios de la Corte Suprema, Citation2019, 133-144).

Most nationality laws throughout Latin America can be characterized as moderately open to naturalization in a comparative perspective. Residence periods for those willing to obtain nationality are relatively short, with only two or three years required in many countries, including Argentina, Bolivia, Ecuador, Paraguay, and Peru. In turn, renunciation requirements of previous citizenship are rare and are only included in the migration legislation of a few countries, like Costa Rica, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, and Nicaragua. Finally, most states –with some exceptions, including Paraguay– accept dual nationality, which is part of a broader trend that has expanded since the 1980s, mainly thanks to the advocacy of the Latin American diaspora, mainly those residing in the US (Escobar, Citation2007; Harpaz & Mateos, Citation2019; Mateos, Citation2019).

The historical origins of a theoretically easy procedure to obtain nationality can be traced back to the years following independence, when waiting periods before naturalization were considerably shortened to attract settlers (Gleizer, Citation2017; Moya, Citation1998; Sacchetta Ramos Mendes Citation2010). There has been a strong path dependence on this issue, and present nationality laws are still influenced by these historical choices (Acosta, Citation2018). Despite what can be considered conditions that are easy to fulfill on paper, the number of naturalizations –in countries where data is available– is extremely low. For example, in Uruguay, only 3,770 obtained legal citizenship between 2006 and 2018. In Chile, the number totaled 7,800 between 2006 and 2014. Data for Peru shows 13,254 naturalizations for the period 2001-2017. Numbers are not higher in Colombia or Paraguay, with less than 220 between 2010 and 2011 in the former and 777 for the period 1996-2013 in the latter. In Argentina, which has the most significant number of non-nationals in the region, with 2.2 million, an average of 5,000 persons were naturalized per year between 2015 and 2018, amounting to a naturalization rate of only 0.2% (Acosta, Citation2021).

Despite the importance of access to citizenship for social inclusion and security of residence, naturalization has been barely analyzed in the literature (Blanchette, Citation2015; Courtis & Penchaszadeh, Citation2015). More research is needed in at least three aspects. First, scholars should collect data on the number of naturalization applications and rejections. Most countries in Latin America do not publish official statistics on newly naturalized citizens (Acosta, Citation2021). As in refugee protection and regularization, such data should be disaggregated and analyzed by gender and nationality of origin.

Second, scholars should take ethnographic approaches to studying the policy application process in practice. Such research could unveil how political actors understand naturalization and naturalized citizens, and what kind of discretion is exercised by the various actors involved, including the executive, ministries of foreign affairs, civil registries, or police forces. The bureaucratic procedure should be followed and analyzed from application to decision, including possible difficulties in compiling documents and certificates. Again, such studies should include intersectional approaches and consider the ideological and cognitive determinants of categorization that influence the decision-making process.

Third, all countries in the region treat naturalized citizens as second-class when exercising political rights or accessing specific jobs or positions, mainly in the judiciary, executive or legislative (Acosta, Citation2018). From a reflexive perspective, scholars should explore whether non-nationals know about these limitations and whether they represent a deterrent to applying for naturalization. Similarly, their understanding of regional free movement agreements, or the need to renounce citizenship in some countries, such as Mexico, should also be analyzed empirically, thus giving a voice and the chance to share their experiences and perceptions to migrants themselves.

Concluding remarks

In this article, we have argued for the need to expand the geographic scope of the reflexive turn in migration research to Latin America, particularly by focusing on categories, concepts and (lack of) data that both shape –and are shaped by– representations of spatially mobile people and related practices of migration governance in the areas of refugee protection, migrant regularization, and naturalization. Broader efforts on data collection on residencies and migrant regularization have been underway regarding legal instruments, for example, the recently launched databases “APLA” (Hammoud-Gallego, Citation2022) and “Migration Policy Regimes in Latin America and the Caribbean”.16

Focusing on implementation gaps in these areas allows us to better understand the effects of positive, human rights-based migration narratives on migration-related policies and, thus, on the lived experiences of migrants and refugees. Implementation gaps also invite us to develop intersectional approaches to studying regional migration governance, adopting broader critical socio-political lenses.

To achieve this goal, academia and international organizations should collect relevant governmental and original data, critically reviewing the categories applied, e.g. questioning how race and ethnicity, gender diversity and migration or refugee status are and have been measured and to what effect. Information on asylum seekers and refugee statuses is more accessible than in the areas of naturalization and regularization, which might be due to efforts by international organizations such as the UNHCR to collect such data.Footnote17 In all this, it will also be crucial to give more voice to local researchers, political actors, migrants, and refugees. This can be achieved by going beyond traditional interviews to include unstructured biographical and life story interviews, where the respondent can actively direct the research inquiry and collaborate in knowledge production by introducing aspects not initially foreseen by the researcher (Fedyuk & Zentai, Citation2018).

Notes

1 These countries are: Argentina, Belize, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua, Paraguay, Peru, and Uruguay. In Costa Rica, the laws do not include the Cartagena definition, but the Constitutional Court has incorporated it through its jurisprudence. The following link provides a table of reference for the region’s relevant laws: https://www.refworld.org.es/cgi-bin/texis/vtx/rwmain/opendocpdf.pdf?reldoc=y&docid=5a01fc3a4

2 Cartagena Declaration on Refugees, adopted by the Colloquium on the International Protection of Refugees in Central America, Mexico, and Panama, held at Cartagena, Colombia, 19-22 November 1984. In 1984, and in view of the large number of Central Americans escaping El Salvador, Guatemala, and Nicaragua due to civil wars and human rights violations, Latin American countries recognized that both the Convention and its Protocol were insufficient to respond to displacement scenarios, leading regional governments to draft the Cartagena Declaration on Refugees that same year (Arboleda, Citation1991).

3 Inter-American Court of Human Rights, Rights and Guarantees of Children in the Context of Migration and/or in Need of International Protection. Advisory Opinion OC-21/14 of August 19, 2014. Series A No. 21, paragraph 79. The Institution of Asylum and Its Recognition as a Human Right in the Inter-American System of Protection (Interpretation and Scope of Articles 5, 22(7) and 22(8) in relation to Article 1(1) of the American Convention on Human Rights), Advisory Opinion OC-25/18, Inter-American Court of Human Rights (30 May 2018) para 123.

4 Declaration, Lima Group, 23 September 2019. Signed, among others, by Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Guatemala, Honduras, Panama, Paraguay, and Peru.

5 Other countries, such as Bolivia, Paraguay and Peru have also granted refugee status under Cartagena to a limited number of Venezuelan nationals. CONARE BOLIVIA (2020): Comunicado de la CONARE, La Paz (11 de febrero). Disponible en: http://www.cancilleria.gob.bo /webmre/noticia/3813; INFOBAE (2019): “Paraguay otorgó el estatus de refugiado a 720 venezolanos” (29/12/2019). Disponible en: https://www.infobae.com/am erica/venezuela/2019/12/29/para guay-otorgo-el-estatus-derefugiado-a-720- venezolanos/.

6 We can see this in Freier and Bird’s (Citation2021) findings after surveying a sample of 808 Venezuelan nationals at the Ecuador-Peru border, asking them about their self-identification as migrants or refugees. Initially, 62 percent self-identified as migrants, and 38 percent as refugees. When the self-identified migrants were subsequently asked if they considered their migration as either voluntary or forced, 59 percent considered it voluntary, while 41 percent said forced. Yet, when self-identified migrants were next asked if they considered their migration as one of “survival,” 93 percent gave an affirmative response. Finally, after reading the Cartagena Declaration to the self-identified migrants, 34 percent changed their self-identification to refugees, resulting in 59 percent of the overall sample self-identifying as refugees when adding the original self-identified refugees from the opening question. These results indicate that the lack of information about refugee definition in the Cartagena Declaration may partly explain why few respondents initially identified as refugees.

7 South American Conference on Migration (SACM), Asunción Declaration, 5 May 2006.

8 XXIII Southern Common Market (MERCOSUR) and Associate States meeting of Ministers of the Interior, Regional Position ahead of the Global Forum on Migration and Development (XXV Specialized Migration Forum) (MERCOSUR/ RMI/ DI Nº 01/ 08) Buenos Aires, 10 June 2008.

9 IX SACM, 2009, Quito 21-22 September; X SAMC, 2010, Cochabamba 25-26; XI SACM, 2011, Brasilia 19-21. 4th meeting of the Andean Community’s Migration Forum, Bogotá Declaration, 10 May 2013.

10 Ecuador, Art. 2, 2017 Organic Law on Human Mobility; Peru, Arts VII and XII, Preliminary Title, Legislative Decree 1,350/ 2017; Brazil, Art. 3, Law 13.445/2017; Chile, Art. 9, Ley 21.325, Ley de Migración y Extranjería, 20 April 2021.

11 The Community of Latin American and Caribbean States, Special Declaration: On Migration and Development, the Dominican Republic, 2017.

13 Colombia, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Decree 216, 1 March 2021.

14 Resolución que normaliza dentro de la categoría de no residente la situación migratoria irregular de los nacionales venezolanos en territorio dominicano, 19 enero 2021.

15 In the first seven months of 2022, more than 71,000 people crossed the Darien irregularly, representing an increase of more than 58% compared to the same period in 2021. In 2021 Venezuelan migrants represented less than 3% of the total number of people crossing the Darien, today they represent 63% of the total (UNHCR, Citation2022).

17 Both R4V and UNHCR compile data on asylum applications and application outcomes, although with some delay and discrepancies in comparison to data provided by national refugee agencies.

References

- Acosta, D. (2009). Latin American reactions to the adoption of the returns directive. (Liberty and security in Europe (p. 8). Center for European Policy Studies. https://www.ceps.eu/ceps-publications/latin-american-reactions-adoption-returns-directive/

- Acosta, D. (2018). The National versus the foreigner in South America: 200 years of migration and citizenship law. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijrl/eez035

- Acosta, D. (2021). Unblocking access to citizenship in South America: policy-makers, courts and other actors. In Bronwen Manby & Rainer Bauböck (Eds.), Unblocking access to citizenship in the global South: should the process be decentralized?, EUI RSC, 2021/07, Global Governance Programme-431, GLOBALCIT, European University Institute, (pp. 6–9).

- Acosta, D., & Brumat, L. (2020). Political and legal responses to human mobility in South America in the context of the covid-19 crisis. More fuel for the fire? Frontiers in Human Dynamics, 2. https://doi.org/10.3389/fhumd.2020.592196

- Acosta, D., & Freier, L. F. (2015). Turning the immigration policy paradox upside down? Populist liberalism and discursive gaps in South America. International Migration Review, 49(3), 659–696. https://doi.org/10.1111/imre.12146

- Acosta, D., & Harris, J. (2022). Migration policy regimes in Latin America and the Caribbean. Immigration, regional free movement, refuge, and nationality. Interamerican Development Bank.

- Acosta, D., & Sartoretto, L. (2020). ¿Migrantes o refugiados? La Declaración de Cartagena y los venezolanos en Brasil. Fundación Carolina, 9, 17.

- Acosta, D., Blouin, C., & Freier, L. F. (2019). La emigración venezolana: Respuestas latinoamericanas. (Documento de Trabajo No. 3; p. 30). Fundación Carolina. http://webcarol.local/la-emigracion-venezolana-respuestas-latinoamericanas/

- Alfonso, A. (2013). La experiencia de los países Suramericanos en materia de regularización migratoria. IOM Migration Information Center. https://repository.iom.int/handle/20.500.11788/1405

- Álvarez Velasco, S. (2020). Ilegalizados en Ecuador, el país de la “ciudadanía universal. Sociologias, 22(55), 138–170. https://doi.org/10.1590/15174522-101815

- Amelina, A. (2021). After the reflexive turn in Migration Studies: Towards the doing migration approach. Population, Space and Place, 27(1), e2368. https://doi.org/10.1002/psp.2368

- Anthias, F. (2013). Intersectional what? Social divisions, intersectionality and levels of analysis. Ethnicities, 13(1), 3–19. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468796812463547

- Arboleda, E. (1991). Refugee definition in Africa and Latin America: The lessons of pragmatism. International Journal of Refugee Law, 3(2), 185–207. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijrl/3.2.185

- Bahar, D., Dooley, M., & Selee, A. (2020). Venezuelan migration, crime, and misperceptions: A review of data from Colombia. Migration Policy Institute. https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/migration-crime-latam-eng-final.pdf

- Basok, T., & Rojas Wiesner, M. L. (2018). Precarious legality: Regularizing Central American migrants in Mexico. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 41(7), 1274–1293. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2017.1291983

- Bauer, K. (2021). Extending and restricting the right to regularisation: Lessons from South America. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 47(19), 4497–4514. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2019.1682978

- Blanchette, T. G. (2015). Almost a Brazilian” gringos, immigration, and irregularity in Brazil. In D. Acosta & A. Wiesbrock (Eds.), Global migration: Old assumptions, new dynamics (pp. 167–194). Praeger.

- Bourbeau, P. (2013). Securitization of migration. A study of movement and order. Routledge.

- Calderón Chelius, L. (2021). Claves para entender la política migratoria mexicana en tiempos de López Obrador. Cadernos de Campo: Revista de Ciências Sociais, 30(30), 99–122. https://doi.org/10.47284/2359-2419.2021.30.99122

- Calva Sánchez, L. E., & Torre Cantalapiedra, E. (2020). Cambios y continuidades en la política migratoria durante el primer año del gobierno de López Obrador. Norteamérica, 15(2), 157–181. https://doi.org/10.22201/cisan.24487228e.2020.2.415

- Cantor, D. J., Freier, L. F., & Gauci, J.-P. (Eds.). (2015). A liberal tide? Immigration and asylum law and policy in Latin America. Institute of Latin American Studies, School of Advanced Study, University of London. https://sas-space.sas.ac.uk/6149/1/01.%20ALT_title%20page%20and%20contents.pdf

- Chauvin, S., &Garcés-Mascareñas, B. (2014). Becoming Less Illegal: Deservingness Frames and Undocumented Migrant Incorporation. Sociology Compass, 8(4), 422–432. https://doi.org/10.1111/soc4.12145

- Courtis, C., & Penchaszadeh, A. P. (2015). El (im)posible ciudadano extranjero. Ciudadanía y nacionalidad en Argentina. Revista SAAP, 9(2), 375–394.

- Dahinden, J., Fischer, C., & Menet, J. (2021). Knowledge production, reflexivity, and the use of categories in Migration Studies: tackling challenges in the field. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 44(4), 535–554. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2020.1752926

- Dirección de Estudios de la Corte Suprema. (2019). Revista Colecciones Jurídicas: “Migrantes (p. 221). Dirección de Estudios de la Corte Suprema. http://decs.pjud.cl/migrantes-nueva-publicacion-sobre-colecciones-juridicas-de-la-corte-suprema/

- Domenech, E. (2013). “Las migraciones son como el agua”: Hacia la instauración de políticas de “control con rostro humano”: La gobernabilidad migratoria en la Argentina. Polis (Santiago), 12(35), 119–142. https://doi.org/10.4067/S0718-65682013000200006

- Domenech, E., & Dias, G. (2020). Regimes de fronteira e “ilegalidade” migrante na América Latina e Caribe. Sociologias, 22(55), 40–73. https://doi.org/10.1590/15174522-108928

- Dufraix Tapia, R., Ramos Rodríguez, R. R., & Quinteros Rojas, D. Q. (2020). “Ordenar la casa”: Securitización y producción de irregularidad en el norte de Chile. Sociologias, 22(55), 172–196. https://doi.org/10.1590/15174522-105689

- Escobar, C. (2007). Extraterritorial political rights and dual citizenship in Latin America. Latin American Research Review, 42(3), 43–75. https://doi.org/10.1353/lar.2007.0046

- Fedyuk, O., & Zentai, V. (2018). The interview in migration studies: A step towards a dialogue and knowledge co-production? In R. Zapata-Barrero & E. Yalaz (Eds.), Qualitative research in European migration studies (pp. 171–188). Springer.

- Fernández Rodríguez, N., Freier, L. F., & Hammoud-Gallego, O. (2020). Importancia y limitaciones de las normas jurídicas para el estudio de la política migratoria en América Latina. In L. Gandini, (Ed.), Perspectivas jurídicas de las migraciones internacionales: abordajes teóricos y metodológicos contemporáneos, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, (85–120).

- Finn, V., & Umpierrez de Reguero, S. (2020). Inclusive language for exclusive policies: Restrictive migration governance in Chile, 2018. Latin American Policy, 11(1), 42–61. https://doi.org/10.1111/lamp.12176

- Freier, L. F.,Correa, A., &Arón, V. (2019). El sufrimiento del migrante: La migración cubana en el sueño ecuatoriano de la libre movilidad. Apuntes, 46(84), 93–123.

- Freier, L. F. (2015). A liberal paradigm shift?: A critical appraisal of recent trends in Latin American asylum legislation. In J. P. Gauci, M. Giuffré, & L. Tsourdi (Eds.), Exploring the boundaries of refugee law: Current protection challenges (pp. 118–145). Brill Publishers.

- Freier, L. F. (2022). The power of categorization: Reflections on the category ‘Venezuelans displaced abroad. Conference Proceedings: MMN Conference: “Measuring Migration: How? When? Why?”. Nuffield College, University of Oxford, 9-10 June 2022.

- Freier, L. F., & Bird, M. (2021). To be or not to be a refugee: Self-identification and socioeconomic integration of ‘survival migrants’ in the global South. CCIS Working Paper.

- Freier, L. F., & Doña-Reveco, C. (2022). Latin American political and policy responses to Venezuelan displacement: Introduction to the special issue. International Migration, 60(1), 9–17. https://doi.org/10.1111/imig.12957

- Freier, L. F., & Gauci, J.-P. (2020). Refugee rights across regions: A comparative overview of legislative good practices in Latin America and the EU. Refugee Survey Quarterly, 39(3), 321–362. https://doi.org/10.1093/rsq/hdaa011

- Freier, L. F., & Gomez García, L. S. (2022). Temporary protection for forced migrants: A commentary on the Colombian temporary protection status (TPS). International Migration, 60(5), 271–275. https://doi.org/10.1111/imig.13056

- Freier, L. F., & Luzes, M. (2021). How humanitarian are humanitarian visas? An analysis of theory and practice in South America. In L. Jubilut, G. Mezzanotti, & M. Vera Espinoza (Eds.), Latin America and refugee protection: Regimes, logics and challenges. Berghahn.

- Freier, L. F., Aron Said, V., & Quesada, D. (2022). Attaining legal equality and protecting vulnerable groups: Non-discrimination and special protection clauses in Latin American immigration and refugee legislation. International Journal of Discrimination and the Law, 22(3), 281–304. https://doi.org/10.1177/13582291221115538

- Freier, L. F., Berganza, I., & Blouin, C. (2022). The Cartagena refugee definition and Venezuelan displacement in Latin America. International Migration, Special Issue, 60(1), 18–36. https://doi.org/10.1111/imig.12791

- Freier, L. F., Castro, M., & Kvietok, A. (2022). The impacts of COVID-19 on migration and migrants from a gender perspective. IOM. https://publications.iom.int/books/impacts-covid-19-migration-and-migrants-gender-perspective

- Gandini, L., Prieto Rosa, V., & Lozano-Ascencio, F. (2020). Nuevas Movilidades en América Latina: La Migración Venezolana en Contextos de Crisis y las Respuestas en la Región. Cuadernos Geográficos, 59(3), 103–121. https://doi.org/10.30827/cuadgeo.v59i3.9294

- Gleizer, D. (2017). Nacionalidad, naturalización y extranjería en el Constituyente de 1917. Cuestiones Constitucionales Revista Mexicana de Derecho Constitucional, 1(38), 259–278. https://doi.org/10.22201/iij.24484881e.2018.38.11883

- Góngora-Mera, M. E., Herrera, G., & Müller, C. (2014). The frontiers of universal citizenship: Transnational social spaces and the legal status of migrants in Ecuador. (No. 71; Working Paper, p. 53). desiguALdades.net International Research Network on Interdependent Inequalities in Latin America. http://www.desigualdades.net/Working_Papers/Search-Working-Papers/working-paper-71-_the-frontiers-of-universal-citizenship_/index.html

- Hammoud-Gallego, O. (2022). A liberal region in a world of closed borders? The liberalization of asylum policies in Latin America, 1990–2020. International Migration Review, 56(1), 63–96. https://doi.org/10.1177/01979183211026202

- Hammoud-Gallego, O., & Freier, L. F. (2022). Symbolic refugee protection: Explaining Latin America’s liberal refugee laws. American Political Science Review, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1017/S000305542200082X

- Harpaz, Y., & Mateos, P. (2019). Strategic citizenship: Negotiating membership in the age of dual nationality. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 45(6), 843–857. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2018.1440482

- Hayes de Kalaf, E. (2021). Legal identity, race and belonging in the Dominican Republic. From citizen to foreigner. Anthem Press. https://anthempress.com/business-management-and-law/legal-identity-race-and-belonging-in-the-dominican-republic-pdf

- IMISCOE. (2022). Reflexivities in migration studies: Key questions. IMISCOE. Retrieved January 12, 2022, from https://www.imiscoe.org/research/standing-committees/927-reflexive-migration-studies

- Jubilut, L. L., Vera Espinoza, M., & Mezzanotti, G. (Eds.). (2021). Latin America and refugee protection: Regimes, logics, and challenges, Berghahn. https://www.berghahnbooks.com/title/JubilutLatin

- Mateos, P. (2019). The mestizo nation unbound: Dual citizenship of Euro-Mexicans and U.S.-Mexicans. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 45(6), 917–938. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2018.1440487

- Meili, S. (2018). The constitutional right to asylum: The wave of the future in international refugee law? Fordham International Law Journal, 41(2), 383.

- Melde, S., & Freier, L. F. (2022). When the stars aligned: Ideational strategic alliances, human rights, and the passing of the Argentine 2004 Migration Law. Third World Quarterly, 43(7), 1531–1550. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2022.2081145

- Menjívar, C., Ruiz, M., & Ness, I. (2018). Migration crises: Definitions, critiques, and global contexts. In The Oxford handbook of migration crisis, Oxford University Press.

- Mourad, L., & Norman, K. P. (2020). Transforming refugees into migrants: institutional change and the politics of international protection. European Journal of International Relations, 26(3), 687–713. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354066119883688

- Moya, J. C. (1998). Cousins and strangers: Spanish immigrants in Buenos Aires, 1850-1930. University of California Press.

- Ochoa, J. (2020). South America’s response to the Venezuelan Exodus: A spirit of regional cooperation? International Journal of Refugee Law, 32(3), 472–497. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijrl/eeaa033

- Papadopoulos, D., & Tsianos, V. S. (2013). After citizenship: autonomy of migration, organisational ontology and mobile commons. Citizenship Studies, 17(2), 178–196. https://doi.org/10.1080/13621025.2013.780736

- Pineda, E., & Ávila, K. (2019). Aproximaciones a la migración colombo-venezolana: Desigualdad, Prejuicio y Vulnerabilidad. Clivatge, 7(7), 46–97. https://doi.org/10.1344/CLIVATGE2019.7.3

- Presidencia de Colombia. (2020). Acoger, Integrar y Crecer. Las políticas de Colombia frente a la migración proveniente de Venezuela. Organización Internacional para las Migraciones (OIM-Misión Colombia). http://repositoryoim.org/handle/20.500.11788/2315

- R4V. (2022). Inter-agency coordination platform for refugees and migrants of Venezuela. https://www.r4v.info/en

- Ramírez, J. (2020). From South American citizenship to humanitarianism: The turn in Ecuadorian immigration policy and diplomacy. Estudios Fronterizos, 21(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.21670/ref.2019061[Mismatch

- Rathod, J. (2018). Criminalization and the politics of migration in Brazil. Ohio State Journal of Criminal Law, 16(1), 147–180. https://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/facsch_lawrev/1069

- Sacchetta Ramos Mendes, J. (2010). Laços de Sangue: Privilégios e Intolerância à Imigração Portuguesa no Brasil (1822-1945) (Vol. 4). Fronteira do Caos Editores. https://www.edusp.com.br/livros/lacos-de-sangue/

- Sagás, E. (2017). Report on citizenship law: Dominican Republic. (Country Reports, p. 22). Global Citizenship Observatory (GLOBALCIT).

- Sánchez Nájera, F. (2020). Legislación y política migratoria Mexicana. In N. Caicedo Camacho (Ed.), Políticas y Reformas Migratorias en América Latina. Un Estudio Comparado. Universidad del Pacífico.

- Sánchez Nájera, F., & Freier, L. F. (2022). The Cartagena refugee definition and nationality-based discrimination in Mexican refugee status determination. International Migration, Special Issue, 60(1), 37–56. https://doi.org/10.1111/imig.12910

- Santi Pereyra, S. E. (2018). Biometría y vigilancia social en Sudamérica: Argentina como laboratorio regional de control migratorio. Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Políticas y Sociales, 63(232), 247–268. https://doi.org/10.22201/fcpys.2448492xe.2018.232.56580

- Santi, S. (2020). La nueva política migratoria de Paraguay: Derechos humanos y seguridad como pilares para el tratamiento político de la inmigración. Estudios de Derecho, 77(169), 213–242. https://doi.org/10.17533/udea.esde.v77n169a09

- Selee, A., & Bolter, J. (2022). Colombia’s open-door policy: An innovative approach to displacement? International Migration, Special Issue, 60(1), 113–131. https://doi.org/10.1111/imig.12839

- Stang, M. F. (2016). De la Doctrina de la Seguridad Nacional a la gobernabilidad migratoria: La idea de seguridad en la normativa migratoria chilena, 1975–2014. Polis (Santiago), 15(44), 83–107. https://doi.org/10.4067/S0718-65682016000200005

- UNHCR. (2019). Guidance note on international protection considerations for Venezuelans—Update I (p. 3). UNHCR. https://www.refworld.org/docid/5cd1950f4.html

- UNHCR. (2020). Global trends. Forced displacement in 2019 (p. 84). UNHCR. https://www.unhcr.org/statistics/unhcrstats/5ee200e37/unhcr-global-trends-2019.html

- UNHCR. (2022). Aumenta el número de personas de Venezuela que cruzan el Tapón del Darién. https://www.acnur.org/noticias/press/2022/3/62339ec54/aumenta-el-numero-de-personas-de-venezuela-que-cruzan-el-tapon-del-darien.html#_ga=2.200078446.1134847859.1661532571-108596929.1660681394

- Wade, P. (1997). Race and ethnicity in Latin America. Pluto Press.

- Wilson, T. D. (2014). Violence against women in Latin America. Latin American Perspectives, 41(1), 3–18. https://doi.org/10.1177/0094582X13492143

- Wimmer, A., &Glick Schiller, N. (2002). Methodological nationalism and beyond: nation-state building, migration and the social sciences. Global Networks, 2(4), 301–334. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0374.00043

- Yates, C. (2019). As more migrants from Africa and Asia arrive in Latin America, governments seek orderly and controlled pathways. Migration Policy Institute. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/extracontinental-migrants-latin-america

- Zetter, R. (2007). More labels, fewer refugees: Remaking the refugee label in an era of globalization. Journal of Refugee Studies, 20(2), 172–192. https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/fem011